VTNA Spreadsheet Tools for Reaction Kinetics: A Practical Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Variable Time Normalization Analysis (VTNA) spreadsheet tools for determining reaction kinetics, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

VTNA Spreadsheet Tools for Reaction Kinetics: A Practical Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Variable Time Normalization Analysis (VTNA) spreadsheet tools for determining reaction kinetics, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles of global rate laws and visual kinetic analysis, then details practical methodologies for implementing VTNA using accessible spreadsheet software. The content addresses common troubleshooting scenarios and optimization techniques for handling sparse or noisy experimental data. Finally, it validates the approach through comparative analysis with automated platforms like Auto-VTNA and explores future applications in pharmaceutical development and clinical research, offering a complete resource for integrating robust kinetic analysis into the reaction optimization workflow.

Understanding VTNA: From Global Rate Laws to Accessible Kinetic Analysis

The Critical Role of Chemical Kinetics in Reaction Understanding and Optimization

The study of chemical kinetics is fundamental to the mechanistic understanding of chemical reactions and is crucial for developing safe, efficient, and scalable synthetic procedures, particularly in pharmaceutical development and complex catalytic reactions [1]. The global rate law provides a mathematical expression that correlates the reaction rate with the concentrations of all reacting species, taking the general form: Rate = kobs[A]m[B]n[C]p, where [A], [B], and [C] represent molar concentrations of reactants, catalysts, or products; kobs is the observed rate constant; and m, n, p are the reaction orders with respect to each component [1]. Establishing this rate law empirically from experimental data, without prerequisite mechanistic assumptions, provides invaluable insights into reaction behavior under synthetically relevant conditions.

Traditional kinetic approaches like the initial rates method and flooding techniques have significant limitations despite their analytical simplicity [1]. These methods often operate under non-synthetically relevant conditions or fail to detect changes in reaction orders associated with complex mechanisms such as catalyst deactivation and product inhibition [1]. The pharmaceutical industry's need for efficient reaction optimization and greener chemistry principles has accelerated the development of data-rich kinetic analysis tools that provide more comprehensive mechanistic understanding [2].

Variable Time Normalization Analysis (VTNA): Principles and Evolution

Theoretical Foundation of VTNA

Variable Time Normalization Analysis (VTNA) represents a significant advancement in visual kinetic analysis tools that has gained prominence over the past decades. This methodology was pioneered to streamline the determination of rate laws from series of "same excess" and "different excess" experiments [1]. The fundamental principle of VTNA involves normalizing the time axis of concentration-time data with respect to a particular reaction species whose initial concentration varies across different experiments [1]. When the time axis is normalized with respect to every reaction component raised to its correct order, the concentration profiles linearize, allowing for direct determination of reaction orders [1].

The mathematical transformation in VTNA applies an adjusted time scale according to the expression: tnormalized = t × [A]0m × [B]0n × [Cat.]0p, where t is real time, [A]0, [B]0, and [Cat.]0 are initial concentrations, and m, n, p are the reaction orders being tested [1]. The optimal order values are identified when this normalization produces the best overlay of concentration profiles from different experiments, indicating that the time scaling correctly accounts for the concentration dependencies in the rate law.

Comparative Analysis of Kinetic Methods

Table 1: Comparison of Kinetic Analysis Methods

| Method | Key Principle | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Rates | Measures rate at t→0 for varying initial concentrations | Simple analysis, linearizable data | Non-synthetically relevant conditions; misses complex kinetics |

| Flooding | Pseudo-first-order conditions with one component in large excess | Simplifies complex rate laws | Masks true concentration dependencies; non-representative conditions |

| Traditional VTNA | Time normalization with visual overlay of profiles | Synthetically relevant conditions; detects complex kinetics | Manual trial-and-error approach; subjective visual assessment |

| Auto-VTNA | Computational optimization of profile overlay | Automated, quantitative, handles multiple species concurrently | Requires concentration-time data from multiple experiments |

Auto-VTNA: An Automated Platform for Kinetic Analysis

Development and Capabilities

Auto-VTNA represents a next-generation, automated platform for performing VTNA that addresses several limitations of previous methods [3] [1]. Developed as a Python package with a free graphical user interface (GUI), Auto-VTNA requires no coding expertise or sophisticated kinetic modeling knowledge from users, significantly enhancing accessibility for synthetic chemists [1]. This open-access tool enables researchers to determine all reaction orders concurrently rather than sequentially, dramatically expediting the kinetic analysis workflow while providing robust quantitative error analysis and visualization capabilities [3] [1].

The platform employs sophisticated algorithms to automate the overlay assessment that was traditionally performed manually through visual inspection. It utilizes a 5th degree monotonic polynomial fitting procedure to quantify the degree of overlay between normalized concentration profiles, with the root mean square error (RMSE) between fitted curves serving as an objective "overlay score" to identify optimal reaction orders [1]. This computational approach eliminates human bias while maintaining the ability to handle noisy or sparse experimental datasets and complex reactions involving multiple reaction orders [1].

Key Innovations and Workflow

Auto-VTNA introduces several groundbreaking features that distinguish it from earlier tools like Kinalite [1]. Unlike previous methods that could only analyze two experiments simultaneously for a single reaction component, Auto-VTNA can process an unlimited number of experiments and determine orders for multiple species concurrently [1]. This capability enables more efficient "different excess" experiments where initial concentrations of several species are varied simultaneously, potentially reducing the total number of experiments required for complete kinetic characterization [1].

The automated workflow implements an iterative optimization algorithm that: (1) defines a mesh of possible order values within a specified range; (2) creates all possible combinations of order values for each normalized species; (3) calculates the transformed time axis for each combination; (4) computes overlay scores through curve fitting; and (5) refines the order value precision through successive iterations [1]. This process generates comprehensive visualizations showing how overlay scores vary with different order values, enabling quantitative justification of optimal orders that was previously impossible with manual VTNA [1].

Diagram 1: Auto-VTNA Workflow for Kinetic Analysis. This flowchart illustrates the automated process for determining global rate laws using Auto-VTNA, highlighting the iterative optimization of reaction orders based on concentration profile overlay scores.

Experimental Protocols for VTNA

Comprehensive VTNA Procedure Using Auto-VTNA

Objective: Determine the global rate law for a catalytic reaction A + B → P using Auto-VTNA.

Materials and Equipment:

- Reaction components (substrates, catalyst, solvent)

- Analytical instrumentation (in situ FTIR, NMR, or HPLC for concentration monitoring)

- Auto-VTNA platform (accessible via GitHub repository)

- Standard laboratory glassware and temperature control equipment

Experimental Design:

- Design a series of "different excess" experiments where initial concentrations of A, B, and catalyst are systematically varied. Modern approaches may alter multiple concentrations simultaneously to maximize information density [1].

- Conduct reactions under isothermal conditions with continuous or frequent sampling for concentration analysis.

- Record concentration-time profiles for all relevant species across all experiments.

Data Analysis Protocol:

- Import concentration-time data into Auto-VTNA GUI in CSV format.

- Specify the reaction components to be included in the normalization (reactants, catalysts, products).

- Set appropriate search ranges for order values (typically -1.5 to 2.5) based on chemical intuition.

- Run the automated analysis to determine optimal order values that minimize the overlay score.

- Interpret results using the provided visualization tools and quantitative metrics.

Validation and Interpretation:

- Classify overlay quality based on RMSE values: excellent (<0.03), good (0.03-0.08), reasonable (0.08-0.15), or poor (>0.15) [1].

- Verify that the determined orders are chemically plausible.

- Utilize the global rate law for mechanistic hypothesis generation and reaction optimization.

Integrated Green Chemistry Protocol

Objective: Combine VTNA with solvent greenness assessment for sustainable reaction optimization [2].

Procedure:

- Perform initial VTNA to establish baseline kinetics.

- Apply linear solvation energy relationships (LSER) to understand solvent effects.

- Calculate green chemistry metrics for different solvent systems.

- Predict reaction performance in alternative, greener solvents.

- Validate predictions experimentally through additional VTNA.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Kinetic Studies

| Reagent/Category | Function in Kinetic Analysis | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Process Analytics (in situ FTIR, NMR) | Real-time concentration monitoring | Enables data-rich experiments under synthetically relevant conditions [1] |

| Automated Reactor Systems | Precise control and reproducibility | Facilitates high-throughput kinetic data collection [4] |

| Python Programming Environment | Custom analysis and automation | Enables implementation of Auto-VTNA and related tools [1] |

| Reference Compounds | Analytical calibration | Essential for quantitative concentration determinations |

| Isotopically Labeled Analogs | Mechanistic probing | Helps track specific atom pathways in complex reactions |

Applications and Case Studies

Pharmaceutical Reaction Optimization

The application of Auto-VTNA to pharmaceutical-relevant reactions demonstrates its significant practical utility. In aza-Michael and amidation reactions, researchers have successfully combined VTNA with solvent greenness assessment to predict new reaction conditions in silico before experimental validation [2]. This integrated approach allows for simultaneous optimization of both reaction efficiency and environmental impact, aligning with green chemistry principles that emphasize safer chemicals, waste reduction, and improved efficiency [2].

The platform's ability to handle complex reaction schemes has proven particularly valuable in drug development, where reactions often involve sophisticated catalysts and multiple potential pathways. By providing a global view of concentration dependencies, VTNA helps identify inhibition effects, catalyst degradation pathways, and non-intuitive concentration effects that might be missed by traditional initial rate studies [1]. This comprehensive understanding enables more robust process design and scale-up from laboratory to production scale.

Automated Kinetic Platforms

Recent advances have integrated VTNA into fully automated chemical platforms, such as the "Chemputer" system with online analytics (UV/Vis, NMR) [4]. These systems automate the entire kinetic measurement workflow, addressing the repetitive and time-consuming nature of kinetic studies that often leads to their omission in routine reaction investigation [4]. In one demonstration, over 60 individual experiments were conducted with minimal intervention, highlighting the significant time savings achievable through automation [4].

Such automated platforms utilize chemical programming languages like XDL to store experimental procedures and results in precise, computer-readable formats [4]. This standardization facilitates the creation of comprehensive kinetic databases that can benefit machine learning approaches in reaction prediction and optimization. The integration of VTNA into these systems represents a convergence of experimental chemistry, data science, and automation that is transforming reaction analysis in pharmaceutical and industrial settings.

Implementation Guidelines and Best Practices

Data Quality Considerations

Successful application of VTNA requires careful attention to data quality and experimental design. Key considerations include:

- Ensure sufficient data density in concentration-time profiles, especially during the initial reaction phase where rates change most rapidly.

- Incorporate appropriate experimental replicates to assess data reproducibility and error ranges.

- Validate analytical methods for concentration determination to minimize systematic errors.

- For automated platforms, establish calibration curves and detector linearity ranges before extensive data collection.

Interpretation Framework

Auto-VTNA provides quantitative metrics to guide interpretation of kinetic results:

- Use the overlay score (RMSE) to assess the quality of the determined orders, with lower values indicating better agreement.

- Examine the sensitivity of overlay scores to order variations to understand confidence in determined values.

- Consider chemical plausibility when interpreting fractional or negative orders, which may indicate complex mechanisms.

- Employ the visualization tools to identify potential issues with the kinetic model, such as systematic deviations in the overlay.

The continued development and adoption of tools like Auto-VTNA represents a significant advancement in making sophisticated kinetic analysis accessible to a broader range of chemists, potentially transforming how reaction optimization is approached in pharmaceutical and industrial chemistry settings [1]. As these methods become more integrated with automated platforms and green chemistry principles, they offer the promise of more efficient, sustainable, and rationally designed chemical processes.

In the study of chemical kinetics, the rate law is an empirical mathematical expression that describes the relationship between the rate of a chemical reaction and the concentration of its reactants [5] [6]. These rate laws take the general form of rate = k[A]^m[B]^n, where k is the rate constant, [A] and [B] represent molar concentrations of reactants, and m and n are the orders of reaction with respect to each reactant [5]. The sum of these exponents (m + n) gives the overall reaction order [6]. Global rate laws refer to empirical equations that describe the kinetic behavior of complex reactions without requiring a detailed understanding of the underlying elementary steps, making them particularly valuable for optimizing synthetic pathways in pharmaceutical and industrial chemistry.

The determination of reaction orders is fundamental to understanding kinetic behavior. A reaction is classified as first-order with respect to a reactant if doubling its concentration doubles the reaction rate, second-order if doubling the concentration quadruples the rate, and zero-order if changing the concentration has no effect on the rate [7]. For complex reactions with multiple reactants, the overall kinetic behavior is described by global rate laws that encompass the net effect of all reaction steps.

Theoretical Foundation of Variable Time Normalization Analysis (VTNA)

Variable Time Normalization Analysis (VTNA) has emerged as a powerful methodology for determining reaction orders without requiring extensive mathematical derivations of complex rate laws [8]. This approach is particularly valuable for analyzing complex reactions where traditional methods struggle. VTNA operates on the principle that data from reactions with different initial reactant concentrations will overlap when the correct reaction order is applied to the time axis [8].

The mathematical foundation of VTNA relies on transforming the time coordinate based on tested reaction orders. For a reaction with rate law = k[A]^m[B]^n, the integrated form requires normalization of time according to the hypothesized orders. The key innovation of VTNA is that it allows researchers to systematically test different potential reaction orders and observe which values cause the concentration-time profiles from different initial conditions to superimpose onto a single curve [8].

This methodology represents a significant advancement over classical initial rates and integral methods, which often suffer from limitations including measurement inaccuracies for initial rates and the complexity of integrated equations for multi-parameter systems [6]. VTNA provides a more robust framework for determining kinetic parameters in complex reaction systems relevant to pharmaceutical development and green chemistry applications.

Experimental Protocols for Kinetic Analysis

General Workflow for Kinetic Data Collection

The following protocol outlines the standard procedure for collecting kinetic data suitable for VTNA:

Reaction Setup: Prepare separate reaction vessels with the same concentration of reactants except for one target reactant, which should vary across a series of concentrations (typically 3-5 different concentrations).

Reaction Monitoring: Employ appropriate analytical techniques (NMR, UV-Vis, FTIR, GC, HPLC) to monitor concentration changes of reactants and/or products over time. Ensure the time interval between measurements is appropriate for the reaction rate [7] [9].

Data Collection: Record concentrations of relevant species at consistent time intervals until the reaction reaches completion or a steady state. For the aza-Michael addition between dimethyl itaconate and piperidine, this typically involves using ¹H NMR spectroscopy to track reactant and product concentrations at timed intervals [8].

Data Replication: Perform each concentration series in triplicate to ensure statistical reliability, as demonstrated in kinetic studies of atmospheric reactions [9].

Environmental Control: Maintain constant temperature throughout the experiment using a temperature-controlled bath or block, as temperature fluctuations can significantly impact reaction rates.

VTNA Implementation Protocol

Once concentration-time data has been collected, implement VTNA using the following methodology:

Data Input: Enter concentration-time data into a spreadsheet tool organized by initial reactant concentrations.

Order Hypothesis: Formulate initial hypotheses for reaction orders based on reaction stoichiometry and mechanism.

Time Transformation: Apply time normalization using the formula: normalized time = t × [B]₀^n for a reaction rate dependent on [B], where n is the hypothesized order.

Data Visualization: Plot concentration against normalized time for all initial concentrations.

Optimization Iteration: Systematically adjust the reaction order values until the curves for all initial concentrations overlap onto a single profile.

Validation: Verify the optimized orders by ensuring the data collapse maintains consistency across the entire reaction progress.

For the analysis of aza-Michael additions, this approach has revealed that the order with respect to amine varies with solvent polarity, being trimolecular (second order in amine) in aprotic solvents but bimolecular in protic solvents [8].

VTNA Spreadsheet Implementation for Reaction Optimization

The VTNA spreadsheet serves as a comprehensive tool for kinetic analysis and reaction optimization, integrating multiple analytical functions into a unified framework. The spreadsheet is structured to process kinetic data through a logical workflow:

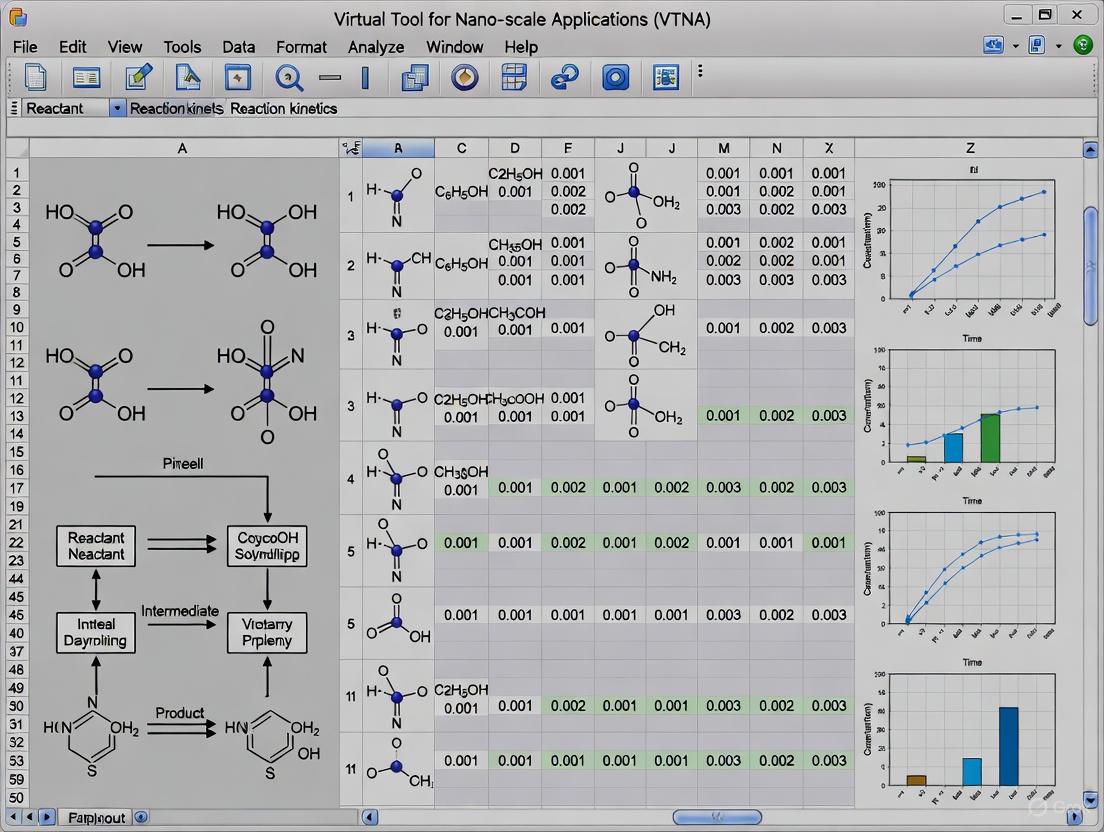

Figure 1: VTNA Spreadsheet Workflow for Kinetic Analysis

The spreadsheet consists of interconnected worksheets with specialized functions [8]:

Data Input Worksheet: Contains fields for recording concentration-time data from multiple experimental runs with varying initial concentrations.

VTNA Processing Worksheet: Automates time normalization calculations and generates overlay plots for visual assessment of reaction order accuracy.

Kinetic Parameter Calculator: Determines rate constants once appropriate reaction orders have been established.

Solvent Effect Analyzer: Constructs Linear Solvation Energy Relationships (LSER) using Kamlet-Abboud-Taft solvatochromic parameters (α, β, π*) to correlate rate constants with solvent properties [8].

Green Metrics Evaluator: Computes green chemistry parameters including reaction mass efficiency (RME), atom economy, and optimum efficiency based on predicted conversions.

For the aza-Michael addition between dimethyl itaconate and piperidine, the spreadsheet successfully identified that the reaction follows first order in dimethyl itaconate but varies between second order and pseudo-second order in amine depending on solvent polarity [8].

Data Presentation and Analysis

Rate Laws for Different Reaction Orders

Table 1: Characteristic Parameters for Different Reaction Order Rate Laws

| Reaction Order | Rate Law | Integrated Rate Law | Half-Life | Linear Plot | Rate Constant Units |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zero-Order | -d[A]/dt = k | [A] = [A]₀ - kt | t₁/₂ = [A]₀/2k | [A] vs t | mol·L⁻¹·s⁻¹ |

| First-Order | -d[A]/dt = k[A] | ln[A] = ln[A]₀ - kt | t₁/₂ = ln2/k | ln[A] vs t | s⁻¹ |

| Second-Order | -d[A]/dt = k[A]² | 1/[A] = 1/[A]₀ + kt | t₁/₂ = 1/(k[A]₀) | 1/[A] vs t | L·mol⁻¹·s⁻¹ |

Solvent Effects on Aza-Michael Addition Kinetics

Table 2: Kinetic Parameters for Aza-Michael Addition in Different Solvents [8]

| Solvent | Reaction Order in Piperidine | Rate Constant (k) | CHEM21 Green Score | Mechanism Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMSO | 2 | 0.025 M⁻²min⁻¹ | 8 | Trimolecular |

| DMF | 2 | 0.030 M⁻²min⁻¹ | 10 | Trimolecular |

| Isopropanol | 1.6 | 0.018 M⁻¹.⁶min⁻¹ | 4 | Mixed |

| Acetonitrile | 2 | 0.022 M⁻²min⁻¹ | 4 | Trimolecular |

| Tetrahydrofuran | 2 | 0.015 M⁻²min⁻¹ | 6 | Trimolecular |

The data reveals how solvent properties influence both reaction mechanism and kinetics. Polar aprotic solvents like DMSO and DMF promote the trimolecular mechanism (second order in amine), while protic solvents like isopropanol enable solvent-assisted proton transfer, leading to non-integer orders [8]. The LSER analysis for the trimolecular reaction yields the correlation: ln(k) = -12.1 + 3.1β + 4.2π, indicating the reaction is accelerated by hydrogen bond accepting (β) and polar/polarizable (π) solvents [8].

Advanced Kinetic Analysis Techniques

Linear Solvation Energy Relationships (LSER)

The VTNA spreadsheet incorporates LSER analysis to quantify solvent effects on reaction rates. The implementation protocol includes:

Data Compilation: Collect rate constants for the reaction in multiple solvents (minimum 8-10 recommended).

Parameter Input: Enter Kamlet-Abboud-Taft parameters (α, β, π*) and molar volume (Vₘ) for each solvent.

Regression Analysis: Perform multiple linear regression to determine coefficients in the equation: ln(k) = C + aα + bβ + pπ* + vVₘ

Model Validation: Evaluate statistical parameters (R², p-values) to identify significant solvent properties.

Prediction: Use the derived relationship to predict rate constants in untested solvents.

For the trimolecular aza-Michael addition, LSER analysis revealed that reaction rates increase with solvent hydrogen bond acceptance (β) and polarity/polarizability (π*), providing mechanistic insights into transition state stabilization [8].

Tikhonov Regularization for Rate Extraction

For complex reactions where direct measurement of rates is challenging, Tikhonov regularization provides a robust mathematical framework to extract reaction rates from concentration-time data without assuming a specific kinetic model [10]. This method converts time-concentration data into concentration-reaction rate profiles by solving the integral equation:

c(t) = ∫₀ᵗ r(t') dt' + c₀

using regularization techniques to control noise amplification [10]. This approach has been successfully applied to diverse reaction systems including thermal decomposition and hydrogenation reactions.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Kinetic Studies

| Reagent/Category | Function in Kinetic Analysis | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Dimethyl Itaconate | Model Michael acceptor for kinetic studies | Aza-Michael addition studies [8] |

| Piperidine/Dibutylamine | Model nucleophiles for order determination | Amine order assessment in nucleophilic additions [8] |

| Deuterated Solvents | NMR-based reaction monitoring | Kinetic profiling by ¹H NMR spectroscopy [8] |

| Kamlet-Abboud-Taft Solvatochromic Dyes | Solvent parameter determination | LSER development for solvent effects [8] |

| Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy | Real-time concentration monitoring | Atmospheric reaction kinetics [9] |

| Stopped-Flow Instrumentation | Rapid kinetics measurement | Fast reactions (millisecond timescale) [7] |

Application to Green Chemistry and Pharmaceutical Development

The integration of VTNA with green chemistry principles enables rational solvent selection based on both kinetic performance and environmental, health, and safety (EHS) considerations [8]. The spreadsheet tool facilitates this by:

Kinetic-Sustainability Correlation: Plotting ln(k) against CHEM21 solvent greenness scores to identify optimal solvents that balance reaction rate with sustainability [8].

Metrics Integration: Calculating green metrics including atom economy, reaction mass efficiency (RME), and optimum efficiency alongside kinetic parameters.

In Silico Optimization: Predicting conversions and green metrics for new reaction conditions prior to experimental verification.

For the model aza-Michael addition, this approach identified that while DMSO provides excellent kinetic performance, alternative solvents with superior EHS profiles may offer better overall sustainability [8].

Computational Tools and Automation

Recent advances in kinetic analysis include the development of automated tools such as Auto-VTNA, a coding-free platform for robust quantitative analysis of kinetic data [3]. This tool automates the VTNA workflow, making sophisticated kinetic analysis accessible to non-specialists. Additionally, data-driven recursive kinetic models are emerging that establish relationships between concentrations at different times rather than relying on traditional concentration-time equations [11].

These computational approaches are complemented by comprehensive kinetics databases like ReSpecTh, which provides validated experimental kinetic data in machine-searchable formats [12]. Such resources enable more efficient mechanism validation and kinetic parameter estimation.

The integration of VTNA methodology with spreadsheet tools provides researchers with a powerful framework for determining global rate laws, optimizing reaction conditions, and implementing greener chemical processes. This approach bridges fundamental kinetic principles with practical applications in pharmaceutical development and sustainable chemistry.

The determination of reaction orders and rate constants is fundamental to understanding chemical mechanisms, optimizing synthetic procedures, and developing safe scale-up processes in pharmaceutical and fine chemical industries [13] [1]. For decades, the method of initial rates and flooding experiments have served as the cornerstone techniques for kinetic analysis in both academic and industrial settings. These classical approaches provide a mathematically straightforward path to determining rate laws by analyzing reaction behavior under carefully controlled conditions [13] [14].

The method of initial rates involves measuring the rate of a reaction at its beginning, typically at very short times when reactant concentrations have not deviated significantly from their initial values [13]. This method relies on the rate law expression, rate = k[A]^m[B]^n, where k is the rate constant, [A] and [B] are reactant concentrations, and m and n are the reaction orders [13]. By performing a series of experiments with different initial concentrations and measuring the initial rate for each, researchers can determine the reaction orders and rate constant [13].

Similarly, the flooding method (also known as the pseudo-first-order method) involves making the concentration of one reactant much greater than others so that its concentration remains essentially constant during the reaction, simplifying the kinetic analysis [1]. While these methods have contributed significantly to our understanding of reaction kinetics, they possess inherent limitations that restrict their effectiveness for complex chemical systems, particularly in pharmaceutical development where reactions often involve sophisticated catalytic cycles and multiple intermediates [1] [15].

Fundamental Limitations of Traditional Approaches

Non-Synthetically Relevant Conditions

The most significant limitation of both initial rates and flooding methods is that they typically require non-synthetically relevant conditions to simplify mathematical analysis [1]. Flooding experiments create artificial environments where one reactant is in large excess, conditions that rarely reflect actual synthetic practice, especially in pharmaceutical synthesis where starting materials may be expensive or scarce [1]. This limitation raises serious questions about whether kinetic parameters determined under these artificial conditions accurately represent reaction behavior under practical synthetic scenarios.

The method of initial rates faces a different but equally problematic constraint: it requires measurement during the very early stages of reaction progress where the percentage of substrate conversion is minimal [15]. Textbook recommendations vary considerably regarding what constitutes an acceptable conversion range, with suggestions ranging from as little as 1-2% to at most 10-20% substrate transformation [15]. These restrictive conditions present substantial practical difficulties for reactions where measurements are painstaking or when substrate concentrations approach detection limits [15].

Inability to Detect Complex Kinetic Phenomena

Traditional kinetic methods are particularly limited in their capacity to detect changes in reaction mechanism during the reaction progress. The initial rates method utilizes only the very beginning of the reaction profile, effectively ignoring the wealth of kinetic information contained in the full reaction trajectory [1]. This approach cannot detect critical kinetic phenomena such as:

- Catalyst deactivation over time

- Product inhibition effects

- Changes in rate-determining steps

- Formation of inhibitory intermediates

- Autocatalytic behavior

These limitations are particularly problematic in pharmaceutical development where complex catalytic reactions are commonplace, and failure to identify such phenomena can lead to flawed scale-up predictions and process optimization [1]. As noted in recent literature, "the results must be treated with caution, as they are either performed under non-synthetically relevant conditions, or cannot detect changes in reaction orders associated with more complex mechanisms" [1].

Table 1: Comparative Limitations of Traditional Kinetic Methods

| Limitation Aspect | Method of Initial Rates | Flooding Method |

|---|---|---|

| Reaction Conditions | Limited to early reaction phase (typically <10% conversion) | Requires large excess of one reactant |

| Mechanistic Complexity | Cannot detect catalyst deactivation or product inhibition | Obscures true concentration dependencies |

| Practical Utility | Difficult with discontinuous analytical methods | Wasteful of expensive reagents |

| Data Quality | Relies on limited data points from reaction start | Masks subtle kinetic phenomena |

Variable Time Normalization Analysis (VTNA) as a Solution

Theoretical Foundation of VTNA

Variable Time Normalization Analysis (VTNA) represents a paradigm shift in kinetic analysis methodology, overcoming the fundamental limitations of traditional approaches [1]. Developed as part of the broader Reaction Progress Kinetic Analysis (RPKA) framework pioneered by Blackmond, VTNA streamlines the determination of rate laws from a series of "same excess" and "different excess" experiments [1]. The methodology allows researchers to derive reaction orders without bespoke software or complex mathematical calculations, making sophisticated kinetic analysis accessible to synthetic chemists [1].

The core principle of VTNA involves time normalization of concentration-time data with respect to a particular reaction species whose initial concentration varies across different experiments [1]. The transformed time axis is calculated for different postulated reaction orders until the optimal value is identified through data overlay. When the correct reaction orders are applied, concentration profiles from different experiments collapse onto a single curve, confirming the validity of the kinetic model [1]. This approach utilizes the entire reaction progress curve rather than just the initial portion, capturing kinetic information throughout the reaction lifespan.

Practical Implementation and Advantages

VTNA offers several significant advantages over traditional kinetic methods. First, it enables kinetic analysis under synthetically relevant conditions with comparable concentrations of all reactants, providing kinetic parameters that accurately reflect actual synthetic practice [1]. Second, it can detect changes in reaction orders that indicate complex mechanistic behavior such as catalyst deactivation or product inhibition [1]. Third, it makes more efficient use of experimental data by analyzing complete reaction progress curves rather than just initial segments.

The implementation of VTNA has been greatly facilitated by the development of computational tools. Traditional VTNA involved manual manipulation of kinetic data in spreadsheets, with researchers testing different reaction orders through trial-and-error until the best visual overlay of concentration profiles was achieved [1] [16]. Recent advances have automated this process through platforms like Auto-VTNA, a Python-based package that computationally determines the optimal reaction orders by quantifying the degree of concentration profile overlay [1]. This automation removes human bias from the analysis process and enables simultaneous determination of multiple reaction species orders [1].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Traditional Initial Rates Method for Enzyme Kinetics

Principle: Measure reaction velocity at the very beginning of the reaction where substrate concentration has not decreased significantly [15].

Reaction Setup:

- Prepare a series of substrate solutions with concentrations typically ranging from 0.25×Km to 4×Km

- Maintain enzyme concentration constant and significantly lower than substrate concentrations

- Control temperature precisely using a thermostated reaction vessel

Initial Rate Measurement:

- Initiate reaction by enzyme addition

- Monitor product formation or substrate disappearance continuously using spectrophotometry, HPLC, or other appropriate analytical methods

- Record data points at frequent intervals during the initial phase (typically first 5-10% of substrate conversion)

Data Analysis:

- Determine initial velocity (v) from the slope of the linear portion of the progress curve

- Plot v versus substrate concentration [S]

- Fit data to the Michaelis-Menten equation: v = (Vmax × [S]) / (Km + [S])

- Extract kinetic parameters Vmax and Km through nonlinear regression

Limitations: This method requires continuous monitoring techniques and becomes extremely time-consuming with discontinuous analytical methods like HPLC [15]. Accuracy depends on maintaining true initial rate conditions, which is challenging when [S]₀ ≈ Km [15].

Protocol 2: VTNA for Complex Catalytic Reactions

Principle: Analyze complete time-course data from multiple experiments with varying initial concentrations to determine reaction orders [1].

Experimental Design:

- Plan a set of "different excess" experiments where initial concentrations of reactants are systematically varied

- Include at least 3-5 different concentration conditions for each reactant of interest

- Ensure sufficient data density by collecting 10-20 time points per experiment

Data Collection:

- Conduct reactions under isothermal conditions

- Withdraw aliquots at predetermined time intervals

- Analyze composition using appropriate analytical methods (HPLC, GC, NMR, etc.)

- Compile concentration-time data for all reacting species

VTNA Analysis:

- Input concentration-time data into VTNA spreadsheet or computational tool

- Normalize time axis according to: t_norm = t × [A]₀^m × [B]₀^n × [C]₀^p

- Systematically vary reaction orders (m, n, p) to achieve optimal overlay of progress curves

- Identify optimal orders that produce best collapse of data onto a single curve

Validation:

- Verify that normalized data from all experiments overlays satisfactorily

- Calculate global rate law: Rate = k_obs[A]^m[B]^n[C]^p

- Determine rate constant k_obs from normalized data

VTNA Methodology Workflow

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Kinetic Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Auto-VTNA Python Package [1] | Automated determination of reaction orders from kinetic data | Analysis of complex catalytic reactions with multiple species |

| VTNA Spreadsheets [16] | Manual implementation of VTNA methodology | Educational purposes and basic kinetic profiling |

| Process Analytical Technology (PAT) | Continuous monitoring of reaction progress | Data-rich kinetic experiments under synthetically relevant conditions |

| Kinalite API [1] | Python-based kinetic analysis for individual species | Sequential determination of reaction orders |

| Monotonic Polynomial Fitting [1] | Mathematical processing of non-linear kinetic data | Handling reaction profiles with limited data points |

Comparative Analysis and Technical Validation

Quantitative Assessment of Method Performance

Recent studies have provided quantitative validation of VTNA's advantages over traditional methods. Automated VTNA platforms can now concurrently determine multiple reaction orders, significantly reducing researcher analysis time while improving accuracy [1]. The "overlay score" in Auto-VTNA provides a quantitative measure of fit quality, with RMSE values classified as excellent (<0.03), good (0.03-0.08), reasonable (0.08-0.15), or poor (>0.15) [1].

For the initial rates method, systematic errors become substantial when substrate conversion exceeds certain thresholds. Research demonstrates that using the integrated form of the Michaelis-Menten equation directly yields excellent estimates of kinetic parameters even with up to 70% substrate conversion, bypassing the need for strict initial rate measurements [15]. When using the traditional method at 50% substrate transformation, the apparent Km value ((Km)app) can be overestimated by more than 50%, while Vapp remains relatively accurate [15].

Visualization of Methodological Relationships

Kinetic Method Evolution and Relationships

The limitations of traditional flooding and initial rates methods have become increasingly apparent as chemical synthesis, particularly in pharmaceutical development, grows more complex. These classical approaches, while mathematically straightforward, impose significant constraints through their requirement for non-synthetically relevant conditions and their inability to detect crucial kinetic phenomena that emerge over the full reaction trajectory [1] [15].

Variable Time Normalization Analysis represents a sophisticated alternative that addresses these fundamental limitations. By utilizing complete reaction progress curves and employing computational tools for data analysis, VTNA enables accurate kinetic profiling under synthetically relevant conditions [1]. The development of automated platforms like Auto-VTNA has further enhanced the accessibility and robustness of this methodology, allowing researchers to efficiently determine comprehensive rate laws even for complex catalytic systems [1].

For researchers engaged in drug development and process chemistry, embracing these advanced kinetic analysis techniques provides more reliable parameters for reaction optimization and scale-up, ultimately contributing to more efficient and sustainable pharmaceutical manufacturing. The integration of VTNA methodologies and spreadsheet tools into routine kinetic practice represents a significant step forward in reaction understanding and optimization.

Variable Time Normalization Analysis (VTNA) is a powerful kinetic methodology that enables researchers to extract meaningful mechanistic information from entire reaction progress profiles through visual comparison. This method transforms concentration-versus-time data by normalizing the time axis, allowing for the straightforward identification of reaction orders and the detection of complex kinetic phenomena such as catalyst activation and deactivation [17]. Unlike traditional initial rate measurements, which are blind to effects occurring after the reaction's initial stages, VTNA utilizes the full reaction profile, providing a more comprehensive and accurate kinetic picture under synthetically relevant conditions [17]. Its simplicity and minimal mathematical requirements have made VTNA an invaluable tool for chemists working in process chemistry, synthesis, and catalysis who require practical mechanistic insights without complex computations [18].

VTNA belongs to a family of visual kinetic analyses developed over the past fifteen years, alongside Reaction Progress Kinetic Analysis (RPKA). While RPKA uses rate-against-concentration profiles, VTNA operates on the more directly accessible concentration-against-time profiles obtained from common monitoring techniques like NMR, FTIR, UV, GC, and HPLC [17]. This accessibility, combined with the ability to handle reactions with variable catalyst concentrations, makes VTNA particularly suited for complex catalytic systems prevalent in pharmaceutical development and fine chemicals synthesis, where catalyst stability and reaction robustness are critical concerns [19].

Theoretical Foundation of VTNA

Fundamental Principles

The core principle of VTNA involves mathematically modifying the time axis of reaction progress profiles to account for the changing concentrations of reaction components throughout the transformation. The fundamental equation for time normalization in VTNA is:

[ \text{Normalized Time} = \Sigma [\text{Component}]^{\beta} \Delta t ]

Where [Component] represents the concentration of a specific reaction component (reactant, catalyst, or product), β is the order of reaction with respect to that component, and Δt is the time increment [17]. When the time axis is normalized by all kinetically relevant components raised to their correct orders, the transformed progress profiles overlay perfectly, forming a single master curve that represents the intrinsic kinetic behavior stripped of concentration-dependent effects [19].

This approach is particularly powerful for reactions suffering from catalyst activation or deactivation, where the concentration of active catalyst varies throughout the reaction, complicating traditional kinetic analysis [19]. VTNA addresses this challenge through two complementary treatments:

- Catalyst Concentration Known: When the concentration of active catalyst can be measured simultaneously with reaction progress (e.g., via in situ spectroscopy), its instantaneous concentration can be used to normalize the time axis, effectively removing induction periods or deactivation effects and revealing the intrinsic reaction profile [19].

- Catalyst Concentration Unknown: When the active catalyst concentration cannot be measured directly, VTNA can deconvolute its effect on the reaction profile by treating the catalyst as a variable component in the normalization process, allowing estimation of the activation or deactivation profile [19].

The Selwyn Test and Its Relationship to VTNA

The Selwyn test, developed in 1965, represents an important historical precursor to modern VTNA. This method plots product concentration against t[enzyme]₀ for reactions run with different enzyme concentrations but identical other components. If all data points fall on a single curve, it indicates no enzyme denaturation during the reaction [17]. This approach is actually a specific case of VTNA where the catalyst order is assumed to be first order (γ = 1) and the catalyst concentration is constant. VTNA extends this concept to handle variable catalyst concentrations and determine catalyst orders other than one [17].

VTNA transforms experimental data through time normalization, with the optimization process iteratively adjusting reaction orders until concentration profiles overlay perfectly, enabling determination of the global rate law.

Practical Implementation of VTNA

Manual VTNA Protocol

The traditional manual implementation of VTNA follows a systematic protocol that can be executed using spreadsheet software like Microsoft Excel. The workflow consists of three main types of analyses designed to identify different kinetic parameters:

- Detection of Catalyst Deactivation or Product Inhibition: Compare profiles of reactions started at different initial concentrations ("same excess" experiments). Shift the profile of the reaction started at lower concentration to the right on the time axis until its first point overlays with the second reaction profile. Overlay indicates absence of catalyst deactivation and product inhibition, while lack of overlay suggests one of these complications [17].

- Determination of Catalyst Order (γ): For reactions run with different catalyst loadings, substitute the time scale with

Σ[cat]^γ Δt. When catalyst concentration is constant, this simplifies tot[cat]₀^γ. The value of γ that produces overlay of the curves is the order in catalyst [17]. - Determination of Reactant Order (β): To find the order in a specific reactant B whose concentration changes during the reaction, substitute the time scale with

Σ[B]^β Δt. The value of β that produces overlay of reaction profiles is the order in component B [17].

A detailed step-by-step protocol for manual VTNA implementation:

- Data Collection: Monitor reaction progress using appropriate analytical techniques (NMR, FTIR, UV, etc.) to obtain concentration-time data for all relevant species.

- Data Formatting: Organize data in a spreadsheet with columns for time, reactant concentrations, product concentrations, and catalyst concentration (if measurable).

- Initial Visualization: Plot concentration against time for all experiments to identify general trends, induction periods, or deviations from expected profiles.

- Time Transformation: Create additional columns calculating

[component]^β Δtfor hypothesized orders, then compute cumulative normalized time. - Visual Comparison: Plot concentration against normalized time for different order values and visually assess the quality of overlay.

- Order Optimization: Systematically adjust order values until optimal overlay is achieved across all experiments.

- Validation: Confirm results with additional experiments if necessary, particularly for complex systems with multiple interdependent orders.

Automated VTNA Tools

Recent advances have produced automated VTNA platforms that streamline the analysis process and reduce human bias. Two prominent tools are now available:

- Kinalite: A user-friendly online tool that automates VTNA by requiring kinetic data from each experiment as individual CSV files. Users select a reaction species and two relevant experimental datasets to determine reaction order automatically. The package presents results as a plot of errors associated with different order values, identifying the best order value [20] [1].

- Auto-VTNA: A more robust Python package that can elucidate reaction orders of several species simultaneously. It employs a mesh search algorithm to evaluate overlay quality across a range of order value combinations and uses a fifth-degree monotonic polynomial fitting to quantify overlay quality. Auto-VTNA can process experiments where multiple initial concentrations are altered simultaneously, potentially reducing the number of experiments required [1].

Table 1: Comparison of VTNA Implementation Methods

| Method | Required Expertise | Analysis Time | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manual VTNA (Spreadsheet) | Basic spreadsheet skills | Hours to days | No specialized software needed; Intuitive visual feedback | Subjective assessment; Time-consuming optimization |

| Kinalite | Basic data formatting | Minutes | Simple web interface; Removes visual bias | Sequential species analysis; Limited to two datasets at once |

| Auto-VTNA | Basic Python knowledge | Minutes | Concurrent multi-species analysis; Quantitative error assessment; Handles sparse/noisy data | Requires data preprocessing; More complex setup |

Essential Research Reagents and Tools for VTNA

Successful implementation of VTNA requires appropriate experimental setup and monitoring capabilities. The table below details key reagents, tools, and their functions in VTNA experiments:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for VTNA Implementation

| Category | Item/Technique | Function in VTNA | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reaction Monitoring | In situ NMR spectroscopy | Provides simultaneous quantification of multiple species concentration in real time | Enables direct measurement of active catalyst concentration [19] |

| In situ FTIR/UV-Vis spectroscopy | Monitors concentration changes of specific functional groups | Higher time resolution than NMR; Requires calibration curves | |

| Online GC/HPLC | Automated sampling and analysis at discrete time points | Broader analyte range; Discontinuous data collection | |

| Specialized Equipment | Bruker InsightMR flow tube | Enables NMR monitoring under challenging reaction conditions (high pressure, temperature) | Used in hydroformylation example [19] |

| Automated reactor systems | Precisely controls reaction conditions and enables reproducible experimentation | Critical for "same excess" and "different excess" experiments | |

| Data Analysis Tools | Microsoft Excel with Solver add-in | Manual VTNA implementation and order optimization | Accessible platform; Solver automates order optimization [19] |

| Kinalite web interface | Automated VTNA for single species analysis | User-friendly; No coding required [20] | |

| Auto-VTNA Python package | Automated VTNA for multiple simultaneous species | Most powerful option; Enables concurrent order determination [1] |

Application Case Studies

Case Study 1: Hydroformylation with Catalyst Activation

The hydroformylation reaction catalyzed by a supramolecular rhodium complex demonstrates VTNA's ability to handle catalyst activation processes. This system requires three components to assemble the active catalyst: rhodium as the active center, an enantiopure bisphosphite ligand, and a rubidium salt to regulate geometry. The assembly process is not immediate, resulting in a clear induction period in the product formation profile [19].

Using a Bruker InsightMR flow tube to enable online NMR monitoring under pressurized syngas conditions, researchers simultaneously tracked both product concentration and the amount of rhodium hydride (the catalyst resting state). The measured catalyst profile was then used to normalize the time scale of the original reaction progress profile using VTNA. The resulting transformed profile showed no induction period and revealed the true first-order nature of the intrinsic reaction, indicating that olefin-hydride insertion is the rate-determining step [19].

When the active catalyst concentration profile was estimated using VTNA (rather than measured), the method successfully reconstructed the activation profile by imposing the constraint that catalyst concentration could not decrease with time. The solution produced a nearly perfect straight line (R² = 0.99995) when time was normalized against both starting material and variable active catalyst concentrations [19].

Case Study 2: Aminocatalytic Michael Addition with Catalyst Deactivation

The enantioselective aminocatalytic Michael addition of aldehyde to trans-β-nitrostyrene exemplifies VTNA's application to catalyst deactivation systems. When run at low catalyst loading (0.5 mol%), most catalyst deactivated before reaction completion, resulting in a curved reaction profile with an apparent overall order close to one [19].

Despite the inability to quantify active catalyst during the final reaction stages due to overlapping NMR signals, the measured active catalyst data was used to normalize the time scale. The transformed kinetic profile became an almost perfect straight line, indicating overall zero-order reaction in agreement with mechanistic studies at higher catalyst loadings. The slope provided the intrinsic turnover frequency (TOF = 1.86 min⁻¹) [19].

Applying the second VTNA treatment to estimate the deactivation profile (with the constraint that catalyst concentration could not increase), the method converted the curved reaction profile into a straight line (R² = 0.999995) and reconstructed the deactivation profile that aligned well with experimentally measured values where available, while also providing information for reaction stages where direct measurement was impossible [19].

VTNA addresses catalyst deactivation through two approaches: either using measured active catalyst concentrations or estimating the deactivation profile, ultimately transforming curved profiles to reveal intrinsic kinetics and enable mechanistic understanding.

Advanced Applications and Methodological Considerations

Experimental Design for VTNA

Proper experimental design is crucial for successful VTNA implementation. The methodology relies on "same excess" and "different excess" experiments to disentangle competing kinetic effects:

- Same Excess Experiments: Designed to detect catalyst deactivation or product inhibition by comparing reactions with different initial concentrations but identical concentration differences between reactants. For a reaction A + B → P, prepare experiments where [A]₀ - [B]₀ is constant but absolute concentrations differ [17].

- Different Excess Experiments: Designed to determine orders in specific components by systematically varying initial concentrations of one component while keeping others constant. Modern automated VTNA tools like Auto-VTNA enable more efficient designs where multiple components can be varied simultaneously [1].

For multi-reactant systems, the general principle is to design experiments that isolate the kinetic effect of individual components while maintaining synthetically relevant conditions. This often requires careful consideration of stoichiometry and concentration ranges that reflect actual synthetic practice rather than artificially flooded conditions used in traditional kinetic analysis.

Limitations and Validation

While VTNA offers significant advantages, users should be aware of its limitations:

- Precision vs. Accuracy: VTNA provides accurate but not highly precise order values. The subjective nature of visual overlay assessment means slightly different solutions may appear reasonable, particularly with noisy data [17].

- Relative Catalyst Profiles: When estimating catalyst activation/deactivation profiles, the values are relative rather than absolute. The solution represents the profile shape but requires at least one known concentration point to establish magnitude [19].

- Order Interdependence: Inaccurate orders for known components will affect the estimated orders for other components. It is essential to determine orders of kinetically relevant reactants as accurately as possible before applying the method to catalyst profiles [19].

- Complex Mechanisms: VTNA works best for reactions following a consistent rate law throughout the transformation. Systems with changing rate-determining steps or multiple parallel pathways may present challenges.

Validation through complementary techniques is recommended, particularly for complex systems. This may include traditional initial rate measurements, kinetic modeling, or spectroscopic characterization of intermediates. The recent development of quantitative overlay scores in automated VTNA tools helps address some precision limitations by providing objective metrics for optimization [1].

Variable Time Normalization Analysis represents a significant advancement in kinetic methodology that bridges the gap between traditional initial rate analysis and complex computational modeling. Its ability to extract meaningful mechanistic information from entire reaction profiles under synthetically relevant conditions makes it particularly valuable for pharmaceutical development and process chemistry, where understanding catalyst behavior and reaction robustness is crucial.

The ongoing development of automated VTNA platforms like Kinalite and Auto-VTNA is making this powerful methodology more accessible and objective, reducing barriers to implementation for synthetic chemists. As kinetic analysis continues to evolve alongside advances in reaction monitoring technology, VTNA stands as an essential tool in the modern mechanistic chemists toolkit, enabling deeper understanding and optimization of chemical transformations across diverse applications.

Why Spreadsheets? Accessibility and Power for Research Scientists

In the data-intensive field of chemical kinetics, the pursuit of mechanistic understanding drives the development of increasingly sophisticated analytical tools. Yet, amidst this innovation, the spreadsheet remains a cornerstone of the research scientist's toolkit. Its enduring value lies in a powerful combination: accessibility for researchers at all levels of computational expertise and the raw power to handle complex data analysis tasks, such as Variable Time Normalization Analysis (VTNA), for determining global rate laws. This article details the application of spreadsheet tools within a kinetic research workflow, providing structured protocols, key reagent solutions, and clear visualizations to guide scientists in drug development and beyond.

Variable Time Normalization Analysis (VTNA) is a visual kinetic analysis tool that simplifies the determination of reaction orders in a global rate law without requiring expert kinetic models or complex software [1]. The method involves normalizing the time axis of concentration data with respect to the initial concentration of a reaction species, raised to a trial order value. When the correct order value is used, the concentration profiles from experiments with different initial concentrations overlay onto a single curve [1]. Traditionally, this "trial-and-error" process is performed manually within spreadsheets, making the technique accessible to synthetic chemists [8].

Despite the recent development of automated programs like Auto-VTNA—a Python package that can determine all reaction orders concurrently—spreadsheets retain a vital role [3] [1]. They serve as a familiar platform for data management, initial manipulation, and a gateway to understanding the core principles of kinetic analysis before potentially transitioning to more automated, yet complex, software environments [21].

The Accessible Workflow: VTNA in a Spreadsheet

The following protocol and visualization outline the standard workflow for performing a manual VTNA in a spreadsheet, a method foundational to reaction optimization for greener chemistry [8].

Experimental Protocol: Data Collection for VTNA

1. Objective: To obtain concentration-time data for a reaction under synthetically relevant conditions to determine the global rate law using VTNA.

2. Materials: Refer to the "Research Reagent Solutions" table in Section 4.0.

3. Procedure:

- Step 1 - Experimental Design: Design a series of experiments where the initial concentration of one reactant (e.g., Reactant A) is varied while keeping the initial concentrations of all other components in large excess. For catalyst order determination, vary the catalyst loading.

- Step 2 - Reaction Monitoring: Use a process analytical tool (e.g., in situ NMR, IR, or HPLC) to monitor the concentration of a reactant or product over time for each experiment. Ensure data is collected until the reaction is at least 50% complete.

- Step 3 - Data Curation: Organize the collected data in a spreadsheet with separate columns for time and the corresponding concentration for each experiment. Ensure data is saved in a format suitable for transfer to advanced analysis tools (e.g., .csv).

4. Analysis (Manual Spreadsheet VTNA):

- Step 4 - Time Transformation: For a selected reaction species (e.g., catalyst, [Cat]), create a new column for each experiment. Normalize the time axis using the formula: Normalized Time = t * [Cat]_0^n, where n is a trial reaction order.

- Step 5 - Visual Overlay: Plot the concentration (e.g., [Reactant]) against the Normalized Time for all experiments on the same graph.

- Step 6 - Iterate: Manually adjust the trial order n until the best visual overlay of the concentration profiles is achieved. The n value that produces the best overlay is the reaction order with respect to that species.

- Step 7 - Repeat: Repeat Steps 4-6 for each reaction species to build the complete global rate law [1] [8].

Workflow Visualization: From Experiment to Rate Law

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow, highlighting the synergistic role of spreadsheets and specialized software like Auto-VTNA.

Power Through Automation: Bridging to Advanced Tools

While manual spreadsheet analysis is accessible, it has limitations, including being time-consuming and potentially introducing user bias when judging data overlays [1]. Automated tools like Auto-VTNA overcome these limitations while leveraging the spreadsheet's role as a data hub.

Key Advantages of Auto-VTNA:

- Concurrent Analysis: Determines reaction orders for multiple species simultaneously, drastically reducing analysis time [1].

- Quantitative Objectivity: Uses a quantitative "overlay score" (e.g., RMSE from a fitting function) to identify optimal orders, removing human bias from visual inspection [1].

- Robustness: Performs well on noisy or sparse experimental data sets [21].

- Accessibility: Offers a free graphical user interface (GUI) that requires no coding knowledge, accepting common data formats that can be prepared in a spreadsheet [1] [21].

The quantitative analysis in Auto-VTNA generates clear visual outputs, such as a plot of the overlay score against different order values, allowing researchers to justify their findings robustly, moving beyond simple "good" vs. "bad" overlay comparisons [1].

Quantitative Outputs: From Data to Decisions

The table below summarizes the typical quantitative output from an automated VTNA analysis, which provides a numerical basis for concluding the correct reaction orders.

Table: Interpreting Auto-VTNA Overlay Scores (RMSE-based)

| Overlay Score (RMSE) | Qualitative Rating | Implication for Order Confidence |

|---|---|---|

| < 0.03 | Excellent | High confidence in the determined reaction order. |

| 0.03 - 0.08 | Good | Good confidence; orders are likely correct. |

| 0.08 - 0.15 | Reasonable | Moderate confidence; consider further verification. |

| > 0.15 | Poor | Low confidence; data may be unsuitable or model incorrect. |

Source: Adapted from Auto-VTNA development paper [1].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful kinetic analysis requires careful experimental execution. The following table details key reagents and materials commonly employed in VTNA studies, such as the aza-Michael addition model reaction [8].

Table: Key Research Reagents for VTNA Kinetic Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Reaction | Considerations for VTNA |

|---|---|---|

| Dimethyl Itaconate | Model reactant (Michael acceptor) | Purity is critical; concentration must be accurately known. |

| Piperidine / Amines | Model reactant (nucleophile) | Varying initial concentration is key to determining order. |

| Palladium Catalysts | Homogeneous catalyst (e.g., for carbonylation) | Catalyst loading is varied to determine catalyst order. |

| Deuterated Solvents (CDCl₃, DMSO-d₆) | Reaction medium for in-situ NMR monitoring | Must be anhydrous and free of impurities to avoid side reactions. |

| Linear Solvation Energy Relationship (LSER) Solvent Set | To study solvent effects on kinetics [8]. | A set of solvents with characterized polarity parameters (α, β, π*). |

| Internal Standard (e.g., TMS) | For quantitative NMR concentration calculations. | Must be inert and not overlap with reaction signals. |

Creating Accessible Spreadsheets for Research

To fully leverage the power of spreadsheets, scientists must ensure their files are accessible and well-structured. This is crucial for collaboration, reproducibility, and data sharing with advanced analytical tools.

Best Practices for Accessible Research Spreadsheets:

- Use a Simple Table Structure: Employ a single header row, avoid merged or split cells, and do not include completely blank rows or columns. This ensures screen readers and analysis software can navigate the data correctly [22].

- Provide Text in Cell A1: Screen readers start reading a worksheet from cell A1. This cell should contain a descriptive title or overview of the data table [22].

- Use Descriptive Names: Give worksheets unique names (e.g., "KineticRun1Data") and name important cell ranges to aid navigation [22].

- Ensure Sufficient Color Contrast: If using color to convey information (e.g., highlighting), ensure there is a strong contrast between text and background colors. Use patterns or labels as a secondary indicator [22] [23].

- Prefer Reflowable Layouts: When sharing formula sheets or protocols, using a reflowable format (like a Word document) instead of a fixed-layout PDF allows users to adjust font sizes and spacing more easily, enhancing accessibility for low-vision researchers [23].

Spreadsheets continue to be an indispensable tool in the research scientist's arsenal. Their accessibility provides a low-barrier entry point for performing sophisticated kinetic analyses like VTNA, fostering a fundamental understanding of reaction mechanics. Furthermore, their power is not diminished by the advent of automation but is instead amplified by it. The spreadsheet serves as the foundational data layer—the organized, accessible source from which automated tools like Auto-VTNA can draw to perform complex, concurrent analyses with quantitative rigor. By mastering both the traditional spreadsheet environment and modern tools that build upon it, research scientists can streamline the path from kinetic data to mechanistic insight, accelerating the development of safer and more efficient chemical processes.

Implementing VTNA: A Step-by-Step Spreadsheet Protocol for Kinetic Analysis

Variable Time Normalization Analysis (VTNA) is a powerful methodology for determining reaction orders without requiring complex mathematical derivations of potentially complex rate laws [8]. This technique is particularly valuable for optimizing chemical reactions within green chemistry principles, as understanding kinetics allows for reduced energy use and improved efficiency [8]. When embedded within a comprehensive spreadsheet tool, VTNA enables researchers to thoroughly examine chemical reactions, understand the variables controlling reaction chemistry, and optimize processes for pharmaceutical research and development.

Data Requirements and Formatting Specifications

Core Data Components

For effective VTNA implementation, researchers must collect precise experimental data capturing the time-dependent concentration changes of reaction components. The table below outlines the essential data requirements:

Table 1: Essential Data Components for VTNA

| Data Component | Specification | Format | Critical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reaction Time Points | Exponential, sparse intervals preferred (e.g., 1, 2, 4, 8,... min) [24] | Numeric (minutes or seconds) | Frequent early sampling captures rapid changes; longer intervals acceptable later |

| Component Concentrations | Measured at each time point for all key species | Numeric (Molarity or relative values) | Consistent units throughout dataset |

| Initial Concentrations | Precisely known for all reactants | Numeric | Essential for estimating concentrations from conversion data |

| Reaction Conversion | Product formation or reactant consumption | Percentage or fractional | Can be used to estimate concentrations if direct measurements unavailable |

| Temperature Data | Actual internal reaction temperature monitored [24] | Numeric (°C or K) | Critical as rate constants are temperature-dependent |

Data Quality Considerations

The accuracy of VTNA depends heavily on data quality. Experimental errors can arise from multiple sources including stoichiometry inconsistencies, temperature fluctuations, mixing variations, sampling timing inaccuracies, and analytical instrument limitations [24]. Unlike traditional statistical approaches that assume normally distributed errors, kinetic modeling must account for both experimental error and model uncertainty. Early-stage reaction data are particularly sensitive to sampling timing as reaction rates are fastest, while late-stage data are affected less due to slower concentration changes [24].

Experimental Protocol for VTNA Implementation

Reaction Monitoring and Data Collection

Setup and Calibration: Establish the reaction system with precise control of temperature, mixing, and environmental conditions. Calibrate all monitoring equipment (e.g., NMR, HPLC, UV-Vis) according to manufacturer specifications [8].

Initial Sampling: Begin reaction and collect the first sample at the earliest technically feasible time point (typically 1 minute or less for fast reactions). Accurate early time points are crucial for defining the reaction curve shape [24].

Exponential Interval Sampling: Continue sampling using exponentially increasing intervals (e.g., 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32 minutes) to capture both rapid initial changes and slower late-stage kinetics [24].

Reaction Quenching: Employ consistent quenching methods that immediately stop the reaction at each sampling point. Maintain consistent quenching temperature and methodology throughout [24].

Analysis and Data Recording: Analyze each sample using appropriate analytical techniques (e.g., ¹H NMR spectroscopy as used in aza-Michael addition studies [8]) and record precise concentration data for all relevant reaction components.

Temperature Monitoring: Continuously monitor and record the actual internal reaction temperature throughout the experiment, not just the set point of the heating system [24].

Data Validation: Perform technical replicates to assess experimental variability and identify potential systematic errors in sampling or analysis.

VTNA Data Analysis Workflow

Spreadsheet Implementation Protocol

Data Input Structure: Organize raw data with time points in the first column and corresponding concentrations or conversions for each reaction component in adjacent columns.

Order Testing Algorithm: Implement systematic testing of different potential reaction orders for each reactant. The spreadsheet should guide users to test different orders and automatically calculate resultant rate constants [8].

Overlap Assessment: Program calculations to normalize time based on tested orders. Data from reactions with different initial reactant concentrations should overlap when the correct reaction order is inputted [8].

Rate Constant Calculation: Once optimal orders are identified, calculate precise rate constants for each experimental condition.

Linear Solvation Energy Relationship (LSER) Analysis: For reactions studied in multiple solvents, correlate rate constants with solvent polarity parameters (Kamlet-Abboud-Taft solvatochromic parameters: α, β, π*) to understand solvent effects [8].

Green Metrics Calculation: Compute green chemistry metrics including atom economy, reaction mass efficiency (RME), and optimum efficiency to evaluate environmental performance [8].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for VTNA Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in VTNA | Application Example | Critical Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dimethyl Itaconate | Model substrate for kinetic studies | Aza-Michael addition reactions [8] | High purity (>98%), stored under inert atmosphere |

| Piperidine/Dibutylamine | Amine reactants for nucleophilic addition | Second reactant in aza-Michael kinetics [8] | Freshly distilled, moisture-free |

| Solvent Library | Medium for studying solvent effects | LSER analysis [8] | Anhydrous grades, include varied polarity (DMSO, alcohols, etc.) |

| Deuterated Solvents | NMR analysis for concentration monitoring | Real-time reaction monitoring via ¹H NMR [8] | ≥99.8 atom % D, stored with molecular sieves |

| Temperature Standard | Calibration of reaction temperature | Accurate kinetic parameter determination [24] | Certified reference materials (e.g., melting point standards) |

| Internal Standards | Quantitative analytical reference | HPLC or GC quantification when NMR unavailable | Chemically inert in reaction system, distinct spectroscopic signature |

Advanced Kinetic Modeling Considerations

For complex reactions consisting of multiple elementary steps, VTNA serves as a foundation for more comprehensive kinetic models. The extrapolability of kinetic models—their capability to predict reactions under conditions outside the input data range—is the most valuable feature for pharmaceutical process development [24]. When building such models, researchers must balance avoiding over-approximation (including too few steps) against preventing excessive computational resource usage and overfitting (including too many steps) [24]. The experimental data collected through VTNA protocols enables discrimination between competing reaction mechanisms, such as the distinction between bimolecular and trimolecular pathways in aza-Michael additions dependent on solvent properties [8].

Variable Time Normalization Analysis (VTNA) represents a transformative methodology in chemical kinetics, enabling researchers to extract meaningful mechanistic information from entire reaction profiles through visual comparison. This technique moves beyond traditional initial-rate measurements by utilizing the complete dataset obtained from reaction monitoring, providing a more comprehensive view of reaction behavior, including catalyst deactivation, product inhibition, and changing reaction orders. The core principle of VTNA involves mathematically transforming the time axis of concentration-time profiles to achieve overlay between experiments conducted under different conditions. The specific transformation required to achieve this overlay directly reveals the reaction order with respect to the transformed component [17] [25]. Within the broader context of developing a VTNA spreadsheet tool for reaction kinetics research, understanding this core workflow is fundamental for automating the determination of global rate laws, thereby accelerating reaction optimization and mechanism elucidation in pharmaceutical development and chemical synthesis.

Theoretical Foundation of Time Axis Transformation

The mathematical foundation of VTNA rests on the relationship between the rate law and the concentration-time data. For a reaction component B, the rate law can be expressed as rate = d[P]/dt = k [B]^β, where β is the order with respect to B. VTNA cleverly manipulates the integrated form of this rate law. The key innovation is the substitution of the physical time axis (t) with a normalized time function [17].

The fundamental transformation for a component B is given by: