Validating Educational Outcomes in Green Chemistry: Metrics, Methods, and Impact for Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive framework for validating educational outcomes in green chemistry, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Validating Educational Outcomes in Green Chemistry: Metrics, Methods, and Impact for Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for validating educational outcomes in green chemistry, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational need for integrating green chemistry into scientific education and training. The piece details practical methodological tools and application-focused case studies from industry and academia. It addresses common challenges in implementation and offers optimization strategies, culminating in a review of established validation techniques and comparative analysis of successful programs. The goal is to equip professionals with the knowledge to effectively implement and measure green chemistry training, fostering sustainable innovation in biomedical research and clinical development.

The Imperative for Green Chemistry Education in Drug Development

Linking Green Chemistry Principles to Sustainable Drug Development Goals

The integration of Green Chemistry principles into drug development represents a transformative shift in how the pharmaceutical industry addresses its environmental footprint while maintaining scientific innovation and product quality. This alignment is not merely a technical challenge but an educational imperative, as the successful implementation of sustainable practices depends on effectively training researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. The 12 Principles of Green Chemistry, established by Anastas and Warner, provide a systematic framework for designing chemical products and processes that reduce or eliminate the use and generation of hazardous substances [1] [2]. Within the context of sustainable drug development, these principles guide the industry toward achieving broader Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly those related to climate action, responsible consumption and production, and good health and well-being [2].

The connection between green chemistry education and sustainable drug development outcomes is increasingly critical. As noted in research on sustainability education, "Green chemistry practices are possibly more incremental than transformative if the XII Principles are not considered to be a uniform system establishing the 'hows' and 'whys' of these practices" [3]. This highlights the need for robust educational frameworks that equip scientists with both the theoretical knowledge and practical skills to implement green chemistry principles effectively. The transition toward sustainable pharmaceuticals requires a fundamental rethinking of traditional approaches, moving from waste treatment and remediation to pollution prevention at source [2]. This paradigm shift begins in educational settings, where future scientists learn to design processes that minimize environmental impact while maintaining efficiency and efficacy.

Comparative Analysis: Traditional vs. Green Chemistry Approaches in Drug Development

Quantitative Metrics for Comparison

The pharmaceutical industry has traditionally been associated with high environmental impacts, particularly in terms of waste generation and resource consumption. Roger Sheldon's E-factor (Environmental Factor) metric quantifies this impact by measuring the ratio of waste to product, with pharmaceutical production typically generating 25-100 kg of waste per kg of active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) [1]. Another key metric, Process Mass Intensity (PMI), represents the total mass of materials required to produce a unit mass of API, providing a comprehensive view of resource efficiency [4].

Table 1: Environmental Impact Metrics Comparison Between Traditional and Green Chemistry Approaches

| Metric | Traditional Chemistry | Green Chemistry Approach | Improvement Potential |

|---|---|---|---|

| E-Factor (kg waste/kg API) | 25-100+ [1] | Significantly lower through waste prevention | Up to 90% reduction possible [4] |

| Process Mass Intensity | High (complex multi-step synthesis) | Reduced through catalyst innovation & route design | Novel prediction methods enable optimization [4] |

| Solvent Usage | 80-90% of total mass in API production [1] | Replacement with greener alternatives (e.g., water, ethanol) | Up to 95% reduction in hazardous solvent use [5] [6] |

| Energy Consumption | High (energy-intensive processes) | Microwave-assisted, photocatalysis, electrocatalysis | Dramatic reduction through alternative energy inputs [1] [4] |

| Carbon Footprint | High (fossil-based resources) | Biocatalysis, renewable feedstocks | >75% reduction in CO₂ emissions demonstrated [4] |

Experimental Evidence and Case Studies

Recent case studies demonstrate the tangible benefits of implementing green chemistry principles in pharmaceutical development. A notable example comes from AstraZeneca, where replacing palladium with nickel-based catalysts in borylation reactions led to reductions of more than 75% in CO₂ emissions, freshwater use, and waste generation [4]. Similarly, Pfizer has reported that green chemistry implementations resulted in a 19% reduction in waste and 56% improvement in productivity compared with previous drug production standards [7].

In antiparasitic drug development, the application of green chemistry principles to the synthesis of tafenoquine (a treatment for Plasmodium vivax malaria) resulted in a more efficient and environmentally friendly process. The new synthesis route developed by Lipshutz's team employed a two-step one-pot synthesis that eliminated multiple steps and toxic reagents present in previous approaches [2]. This case exemplifies the principle of waste prevention, one of the foundational concepts of green chemistry that emphasizes preventing waste rather than treating or cleaning it up after creation [2].

The transition to water as a solvent represents another significant advancement, with research demonstrating that water can effectively replace volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in various reactions, including Diels-Alder cycloadditions, Suzuki Coupling, and Sonogashira Coupling [6]. These water-based reactions not only reduce toxicity but can also exhibit enhanced reaction rates and selectivity compared to organic solvents, particularly in "on-water" reactions where processes occur at the interface of water and organic substances [6].

Methodological Framework: Integrating Green Chemistry into Drug Development and Education

Experimental Protocols for Green Chemistry Implementation

Analytical Quality by Design (AQbD) with Green Analytical Chemistry

The integration of Analytical Quality by Design (AQbD) with Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) principles represents a systematic methodology for developing environmentally sustainable analytical methods, particularly in High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) applications [5]. The AQbD framework employs a structured approach:

- Define the Analytical Target Profile (ATP): Establish predefined objectives for the method, including accuracy, precision, linearity, and environmental sustainability metrics [5].

- Identify Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) and Critical Method Parameters (CMPs): Determine key method characteristics (e.g., resolution, retention time) and associated parameters (e.g., mobile phase composition, temperature) that influence both performance and greenness [5].

- Conduct Risk Assessment: Utilize tools such as Ishikawa diagrams and Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA) to prioritize variables affecting method quality and environmental impact [5].

- Implement Design of Experiments (DoE): Systematically evaluate multiple factors and their interactions using factorial design, Box-Behnken, or central composite design to optimize both analytical performance and sustainability [5].

- Establish Method Operable Design Region (MODR): Define the multidimensional parameter space where the method delivers acceptable performance, allowing flexibility without revalidation [5].

This approach has been successfully applied in developing RP-HPLC methods for pharmaceutical compounds like irbesartan and metronidazole/nicotinamide combinations, where ethanol-water mobile phases replaced traditional acetonitrile or methanol, resulting in significantly improved environmental profiles while maintaining analytical performance [5].

Alternative Energy Inputs and Reaction Media

Microwave-assisted synthesis provides a green alternative to conventional heating methods, offering dramatic reductions in reaction times (from hours to minutes), improved yields, and reduced energy consumption [1]. The methodology involves:

- Selecting appropriate reaction media based on dielectric properties, with polar solvents like ethanol and water being preferred due to efficient microwave energy absorption.

- Optimizing reaction parameters including power, temperature, and time through systematic evaluation.

- Implementing sealed-vessel systems for reactions requiring elevated temperatures.

Experimental results demonstrate that microwave-assisted synthesis of nitrogen heterocycles (pyrroles, pyrrolidines, indoles) produces cleaner results with shorter reaction times, higher purity, and improved yields compared to conventional methods [1].

Photocatalysis and electrocatalysis represent additional green approaches that utilize light and electricity, respectively, to drive chemical reactions under milder conditions with reduced waste generation [4]. AstraZeneca has implemented photocatalyzed reactions that removed several stages from the manufacturing process for a late-stage cancer medicine, leading to more efficient manufacture with less waste [4].

Educational Outcomes and Assessment Framework

The successful implementation of green chemistry in drug development depends on effective educational strategies that foster both theoretical understanding and practical skills. Research indicates that collaborative and interdisciplinary learning and problem-based learning are the most frequently used and effective teaching methods for green chemistry education [3]. These approaches promote the development of critical skills including environmental awareness, problem-centered learning, systems thinking, and collaborative interdisciplinary work [3].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Green Chemistry in Drug Development

| Reagent/Catalyst | Function in Green Chemistry | Environmental Advantage | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nickel Catalysts | Replacement for precious metals in coupling reactions | More abundant, cheaper, reduced mining impact | Borylation, Suzuki reactions; >75% lower environmental impact [4] |

| Biocatalysts | Enzyme-mediated synthesis | Biodegradable, high specificity, reduced steps | Single-step synthesis of complex drug molecules [4] |

| Ethanol-Water Mobile Phases | Replacement for acetonitrile in HPLC | Less toxic, biodegradable, renewable | AQbD-driven HPLC methods; high green metric scores [5] |

| Water as Solvent | Reaction medium for organic transformations | Non-toxic, non-flammable, abundant | Diels-Alder, Suzuki coupling; enhanced reaction rates [6] |

| Microwave Reactors | Alternative energy input | Reduced reaction times, lower energy consumption | Synthesis of heterocyclic compounds; minutes vs. hours [1] |

Educational interventions should integrate green chemistry at multiple levels, from K-12 through higher education and professional development. As noted by Michelle Ernst Modera of Beyond Benign, "K-12 education is where the spark happens. If we want to build a strong pipeline of scientists, engineers, and citizens who understand sustainability at its core, we have to begin in those early classrooms" [8]. This foundational approach creates a pipeline of professionals equipped to implement sustainable practices throughout their careers.

Assessment of educational outcomes should measure not only knowledge acquisition but also behavioral changes and implementation capabilities. Effective metrics include:

- Systems thinking skills: Ability to understand interconnectedness of chemical processes with environmental systems.

- Problem-centered learning skills: Capacity to apply green chemistry principles to real-world challenges.

- Environmental awareness: Development of consciousness about the environmental impact of chemical processes.

- Collaborative interdisciplinary work: Ability to work across disciplines to develop sustainable solutions [3].

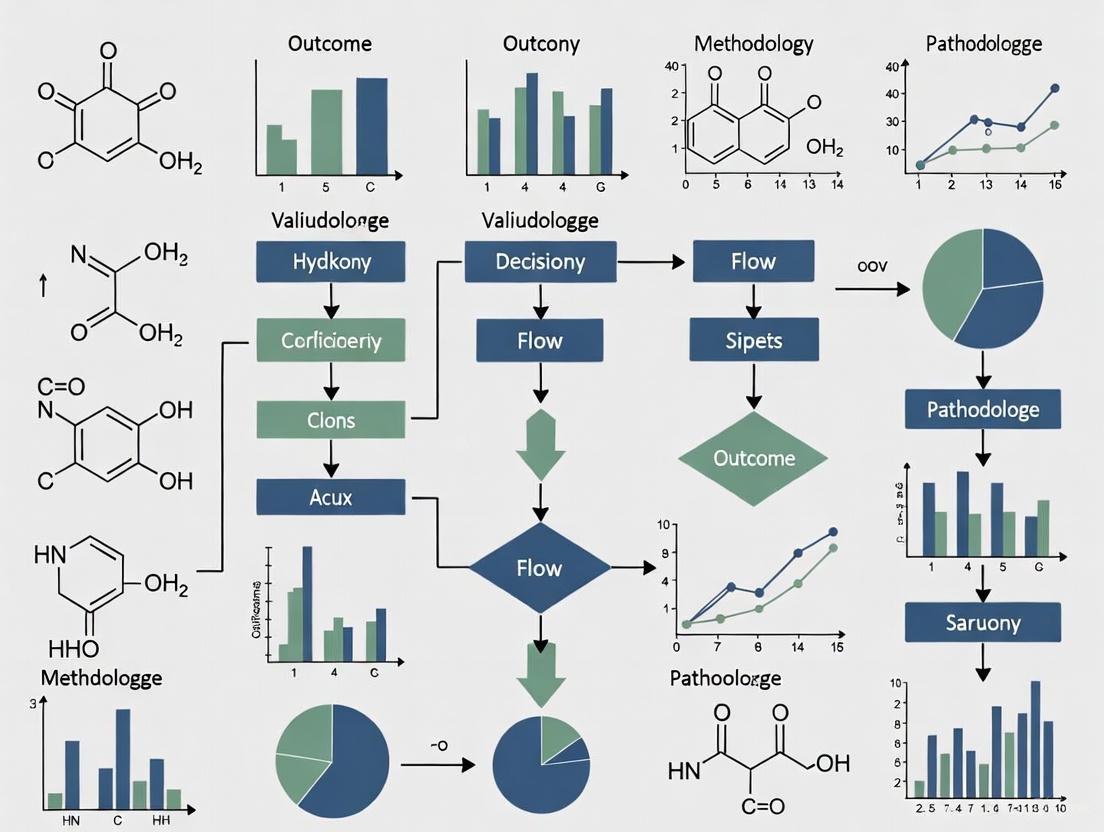

Visualization: Integrating Green Chemistry Principles into Drug Development

The following diagram illustrates the interconnected relationship between green chemistry education, principle implementation, and sustainable outcomes in pharmaceutical development:

The integration of green chemistry principles into drug development represents both an ethical imperative and a strategic advantage for the pharmaceutical industry. The evidence demonstrates that approaches grounded in green chemistry principles—including waste prevention, safer solvent selection, energy-efficient processes, and catalytic reactions—can significantly reduce environmental impacts while maintaining or even improving economic efficiency and product quality. The successful implementation of these approaches depends on robust educational frameworks that equip current and future scientists with the knowledge, skills, and mindset needed to prioritize sustainability throughout the drug development lifecycle.

As the industry moves forward, the convergence of green chemistry with emerging technologies like artificial intelligence, machine learning, and advanced process analytical technologies will further enhance sustainability outcomes. The continued development and standardization of green metrics, coupled with cross-sector collaboration and commitment to education, will accelerate progress toward a more sustainable pharmaceutical industry that aligns with global sustainable development goals. Through the systematic application of green chemistry principles and the ongoing evaluation of educational outcomes, the drug development community can achieve the dual objectives of delivering innovative therapies while protecting environmental and human health for current and future generations.

Current Educational Gaps and Industry Demand for Skilled Professionals

The global economy faces a significant challenge in aligning educational outcomes with rapidly evolving industry needs. This disconnect, termed the "skills gap," represents a mismatch between the competencies employers require and the skills the workforce possesses [9]. In the specialized field of green chemistry, this gap is particularly critical, as it impacts the pace of innovation and the ability to meet global sustainability goals [3]. The validation of educational outcomes in green chemistry is therefore not merely an academic exercise but a crucial process for ensuring that the next generation of scientists, researchers, and drug development professionals is equipped to tackle complex socio-scientific challenges. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the current landscape, supported by quantitative data and experimental methodologies, to frame the ongoing discourse on validating green chemistry education.

Quantitative Analysis of the Skills Gap

The skills gap is a widespread phenomenon with measurable economic consequences. The following tables summarize key statistics and in-demand skills across industries, providing a quantitative backdrop for understanding the broader context in which green chemistry education operates.

Table 1: Global Skills Gap Statistics and Economic Impact

| Metric | Statistic | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Companies Reporting Skills Gaps | 87% of companies | [10] |

| Global Economic Impact | $8.5 trillion annually in lost productivity and opportunities | [10] |

| Reskilling Need | 50% of all employees will need reskilling by 2025 | [10] |

| IT Skills Gap | 1.4 million unfilled tech jobs projected by 2025 | [10] |

| Soft Skills Shortage | 65% of employers report a shortage of soft skills | [10] |

Table 2: Top Skills in Demand for 2025

| Skill Category | Specific Skill | Demand / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Cognitive Skills | Analytical Thinking | Ranked as the #1 most sought-after skill by 69% of companies [11] |

| Creative Thinking | Essential for adapting to complex workplace challenges [10] | |

| Critical Thinking | Top soft skill for problem-solving [10] | |

| Interpersonal Skills | Communication | Listed as critical by 98% of employers [12] |

| Collaboration & Teamwork | Required by 92% of employers [12] | |

| Curiosity & Lifelong Learning | Sought after by 93% of employers [12] | |

| Technical Skills | AI & Machine Learning | Demand increased by 71% [10] |

| Data Analytics | Ranked as the #1 in-demand technical skill [10] | |

| Cybersecurity | Expertise demand grows by 31% [10] | |

| Sustainability Skills | Environmental & Ethical Awareness | Emerging focus area for roles aligned with ESG goals [11] |

The Green Chemistry Education Gap: A Focal Point

Within the broader skills gap, the field of green chemistry presents a unique case study. The American Chemical Society (ACS) now requires undergraduate chemistry programs to provide a "working knowledge" of green chemistry principles (GCPs), signaling a formal recognition of its importance [13]. However, significant gaps remain between educational provision and industry needs.

A primary challenge is the lack of robust, validated assessment tools. While over 500 articles address green and sustainable chemistry education, many reported teaching activities are "occasional, targeted curriculum insertions" with "poorly evaluated curricular outcomes" [13]. This scarcity of readily available assessments capable of eliciting valid and reliable data weakens the overall understanding of the effectiveness of green chemistry curricula [13].

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Green Chemistry Knowledge

To validate educational outcomes, researchers employ specific assessment methodologies. The following are key experimental protocols cited in recent literature:

Protocol 1: The Open-Ended Green Chemistry Generic Comparison (GC)² Prompt

- Methodology: This qualitative instrument presents students with a scenario where two reactions produce the same desired product. Students are asked to list and describe the factors they would consider to decide which reaction is "greener," using complete sentences to explain their reasoning [13].

- Implementation: Responses are collected from students in relevant courses (e.g., organic chemistry, general chemistry). The open-ended format is designed to assess higher-order cognitive skills and elicit student conceptions, including both correct and incorrect understandings of the 12 GCPs [13].

- Analysis: Student responses are analyzed for mentions of specific GCPs. The prompt has been validated for its sensitivity in detecting learning gains in pre- and post-test conditions and for providing reliable psychometric data on which principles students find more or less accessible [13].

Protocol 2: The Assessment of Student Knowledge of the Green Chemistry Principles (ASK-GCP)

- Methodology: This is a 24-item true-false assessment specifically designed to measure undergraduate students' knowledge of the 12 GCPs [13].

- Implementation: The instrument is administered to student cohorts, typically in a pre-test/post-test model to measure learning gains from specific educational interventions.

- Analysis: The closed-ended format allows for quick implementation and evaluation, generating quantitative data on student understanding. Its utility has been demonstrated in detecting learning gains from multiple interventions, though it is less effective at uncovering student reasoning than open-ended prompts [13].

Protocol 3: Case Comparison Exercises with Specific Reactions

- Methodology: This approach uses detailed case studies comparing two specific chemical processes, such as the preparation of cinnamaldehyde from fossil fuel-derived benzaldehyde versus steam-distillation of cinnamon tree bark [13].

- Implementation: Students are required to analyze the given processes and apply GCPs to evaluate their relative "greenness."

- Analysis: This method is effective for measuring deeper learning gains but requires that students possess specific content knowledge about the reactions, which can limit its utility as a pre-test [13].

Research Reagent Solutions for Educational Validation

The following table details key "reagents" or essential tools used in the experimental assessment of green chemistry educational outcomes.

Table 3: Key Reagents for Validating Green Chemistry Education

| Research Reagent | Function in Educational Assessment |

|---|---|

| Open-Ended (GC)² Prompt | Elicits student conceptions and reasoning; assesses higher-order cognitive skills by asking students to generically compare reaction greenness [13]. |

| ASK-GCP Instrument | Provides a rapid, quantifiable measure of student knowledge of the 12 Green Chemistry Principles via a true-false format [13]. |

| Specific Case Comparison Prompt | Measures student ability to apply green chemistry principles to real-world or defined chemical processes, fostering deeper analytical skills [13]. |

| Interdisciplinary Curriculum Modules | Integrates knowledge from biology, engineering, ethics, and business to replicate real-world problem-solving environments [3]. |

| Problem-Based Learning (PBL) Scenarios | Presents students with complex, real-world problems to develop collaborative, critical thinking, and practical solution skills [3]. |

Visualizing the Validation Framework

The process of addressing educational gaps and validating outcomes can be conceptualized as an integrated system. The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and feedback loops connecting industry needs, educational practices, and outcome assessment.

Diagram Title: Framework for Validating Educational Outcomes Against Industry Demand

Comparative Analysis of Bridging Strategies

A multi-faceted approach is required to close the skills gap in green chemistry and related technical fields. The strategies below are derived from industry and academic best practices and serve as a comparative guide for institutional action.

Table 4: Strategies for Bridging the Skills Gap in Education and Industry

| Strategy | Description | Application in Green Chemistry Education |

|---|---|---|

| Foster Interdisciplinary Learning | Integrating information from various disciplines to create new solutions and approaches to problems [3]. | Develop curricula that connect green chemistry with biology, engineering, ethics, business, and social sciences to reflect the holistic nature of sustainability [3]. |

| Implement Active & Problem-Based Learning (PBL) | Using student-centered pedagogy where learning occurs through interaction with real-world problems and stakeholders [3]. | Employ case studies, laboratory work, and civic projects that require students to assess processes and design greener alternatives, building problem-solving and teamwork skills [3] [14]. |

| Invest in Upskilling & Reskilling | Providing continuous, targeted training for existing employees or students to learn new skills [15] [16]. | Create professional development workshops, micro-credentials, and certification programs for working chemists on the latest green chemistry principles and metrics [16]. |

| Utilize Technology-Enabled Learning | Leveraging eLearning platforms, AI-driven assessments, and simulations to personalize and accelerate skill development [15] [16]. | Use digital tools for real-time skills tracking and virtual labs that offer engaging, low-risk environments for students to experiment with and assess chemical processes [16]. |

| Strengthen Industry-Academia Partnerships | Collaboration between educational institutions and businesses to tailor curricula to market demands [10] [17]. | Involve industry professionals in curriculum design, provide internships focused on sustainable practices, and use real industrial problems as case studies in the classroom [17]. |

The current disconnect between educational outputs and industry demands, particularly in forward-looking fields like green chemistry, is a significant barrier to progress and sustainability. Successfully bridging this gap requires a systematic commitment to validating educational outcomes through rigorous assessment protocols, such as the (GC)² prompt and the ASK-GCP instrument. The evidence indicates that a strategic shift towards interdisciplinary, problem-based, and industry-aligned education is imperative. By continuously measuring learning outcomes and adapting curricula accordingly, educators, researchers, and drug development professionals can ensure that the workforce of tomorrow is equipped with the cognitive, technical, and sustainable mindset needed to solve the complex challenges of the future.

Within the global scientific community, regulatory and policy frameworks are increasingly instrumental in steering research, industrial practices, and educational curricula toward sustainability. The European Green Deal (EGD) and the American Chemical Society (ACS) Sustainability Guidelines represent two powerful, yet distinct, drivers from opposite sides of the Atlantic. The EGD is a comprehensive and legally binding regulatory strategy initiated by the European Commission, aiming to make Europe the first climate-neutral continent by 2050 [18] [19]. In parallel, the ACS, a leading professional organization, has established sustainability policy positions and educational guidelines to integrate green chemistry principles into the core of the chemical enterprise and academic training [20] [13]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the interplay between these frameworks is crucial, not only for compliance but also for validating the effectiveness of green chemistry education in preparing scientists to address complex sustainability challenges. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these drivers and outlines experimental protocols for assessing their impact on educational outcomes.

Comparative Analysis of Regulatory Drivers

The following table summarizes the core attributes, objectives, and mechanisms of the EU Green Deal and the ACS Sustainability Guidelines, highlighting their distinct natures and overlapping goals.

Table 1: Comparison of the EU Green Deal and ACS Sustainability Guidelines

| Feature | EU Green Deal | ACS Sustainability Guidelines |

|---|---|---|

| Nature & Origin | Regulatory and policy framework from the European Commission [18] [19] | Professional guidelines and policy positions from a scientific society [20] |

| Primary Scope | Economy-wide transformation (energy, industry, transport, agriculture) [18] [19] | Focus on the chemical enterprise and chemistry education [20] [13] |

| Key Targets | Legally binding climate neutrality by 2050; reduce GHG emissions by at least 55% by 2030 [18] [19] | Encourage sustainable resource usage, waste prevention, and foster green products/processes [20] |

| Governance & Enforcement | EU-wide regulations (e.g., CSRD, ESPR) with mandatory reporting and financial penalties [21] [22] | Integration into ACS-certified undergraduate program requirements; professional endorsement [13] |

| Relevance to Industry | Direct and compulsory for companies operating in the EU market (e.g., via Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism) [18] [19] | Voluntary adoption encouraged as best practice for economically viable and environmentally sound operations [20] |

| Approach to Education | Implied through need for new skills; part of broader societal transition [23] | Explicit requirement for ACS-approved programs to provide a "working knowledge" of green chemistry principles [13] |

Experimental Protocols for Validating Educational Outcomes

Validating the effectiveness of educational interventions within these frameworks requires robust, measurable outcomes. Below are detailed methodologies for key experiments assessing green chemistry knowledge and its application.

Protocol 1: The Green Chemistry Generic Comparison (GC)² Prompt

This open-ended assessment probes higher-order cognitive skills by asking students to articulate the factors they would consider when comparing the "greenness" of two generic chemical reactions [13].

- Objective: To elicit student conceptions of green chemistry principles and measure the ability to apply them in a comparative, decision-making context.

- Methodology:

- Administration: The prompt is administered to students pre- and post-intervention (e.g., a green chemistry course or module). The prompt is: "Suppose there are two reactions that each produce a particular product you desire and that you must choose which reaction is the 'greener' reaction. What factors might you take into consideration about each reaction to make this selection? Please list as many as you can" [13].

- Data Collection: Collect written responses from participants (e.g., undergraduate students in organic chemistry).

- Analysis: Code responses based on the 12 Principles of Green Chemistry. A scoring rubric is used to quantify the number of correct principles identified and the depth of explanation. Psychometric analysis can determine the prompt's sensitivity in detecting learning gains [13].

- Significance: This method moves beyond factual recall, assessing a student's capacity for systems thinking and evaluating processes against multiple, competing green criteria.

Protocol 2: The Assessment of Student Knowledge of Green Chemistry Principles (ASK-GCP)

This is a standardized, true-false instrument designed for efficient measurement of core knowledge.

- Objective: To reliably measure undergraduate students' foundational knowledge of the 12 Green Chemistry Principles.

- Methodology:

- Instrument: A 24-item true-false assessment where each of the 12 principles is evaluated by two statements [13].

- Administration: Administered as a pre-test and post-test to measure learning gains. It can be used across different course levels (general chemistry, organic chemistry).

- Scoring & Validation: Each correct answer scores a point. The instrument's reliability and validity have been analyzed to ensure it produces consistent and meaningful data regarding student knowledge [13].

- Significance: Provides a quick, quantifiable metric for comparing educational outcomes across different institutions or curricular interventions, aligning with the ACS's requirement for a "working knowledge" of the principles [13].

Protocol 3: Case Comparison with Lifecycle Assessment (LCA)

This protocol combines conceptual learning with technical, data-driven analysis, reflecting the demands of regulations like the Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation (ESPR).

- Objective: To evaluate a student's ability to compare specific chemical synthesis pathways using green chemistry principles and quantitative metrics.

- Methodology:

- Case Selection: Provide students with two different synthetic routes to the same active pharmaceutical ingredient (API)—e.g., a traditional route and a greener alternative employing biocatalysis [3].

- Experimental Workflow: Students gather data on both routes, focusing on metrics such as:

- Atom Economy: The efficiency of incorporating starting materials into the final product.

- Process Mass Intensity (PMI): Total mass of materials used per mass of product.

- Energy Consumption: Modeling or measuring the energy required for synthesis and purification.

- Waste Generation: Characterizing and quantifying all waste streams, including solvent use [3].

- Analysis & Reporting: Students perform a comparative LCA, synthesize their findings in a report, and justify their choice of the greener synthesis. This mirrors the data requirements for a Digital Product Passport (DPP) under the EU's ESPR [21] [22].

- Significance: This integrated approach develops technical skills directly applicable to industrial drug development, where regulatory and sustainability reporting is becoming paramount.

The logical relationship between the regulatory drivers, the educational interventions they inspire, and the protocols to validate them can be visualized as a continuous cycle.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Green Chemistry Education Research

The following table details key materials and tools used in the featured experimental protocols for studying green chemistry educational outcomes.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Educational Validation

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|

| Green Chemistry Generic Comparison (GC)² Prompt | Open-ended assessment tool to elicit student conceptions and measure higher-order cognitive skills in comparing chemical processes [13]. |

| ASK-GCP Instrument | Standardized true-false assessment to efficiently measure foundational knowledge of the 12 Green Chemistry Principles and quantify learning gains [13]. |

| Case Comparison Modules | Real-world scenarios (e.g., different API syntheses) that provide the context for students to apply green chemistry principles and quantitative metrics [3]. |

| Lifecycle Assessment (LCA) Software | Digital tool for quantifying the environmental impacts of a product or process throughout its lifecycle, aligning with EU ESPR requirements [21] [22]. |

| Coding Rubric for Principles | Structured scoring guide to systematically analyze and quantify student responses based on the 12 Principles of Green Chemistry [13]. |

The EU Green Deal and ACS Sustainability Guidelines function as complementary forces propelling green chemistry education forward. The EGD creates an external, regulatory imperative, shaping the industrial landscape and creating demand for professionals skilled in lifecycle thinking and compliance. The ACS guidelines provide the internal, pedagogical framework for equipping those professionals, ensuring that the principles of green chemistry are embedded in the core of chemical education. For researchers in drug development and beyond, validating educational outcomes through the described protocols is no longer an academic exercise. It is a critical step in demonstrating that the next generation of scientists possesses the validated knowledge and skills to innovate within a regulatory environment that increasingly demands sustainability, safety, and circularity.

Defining the core competencies in green chemistry is critical for validating educational outcomes and preparing scientists to address global sustainability challenges. The essential knowledge for chemists and drug development professionals has evolved beyond theoretical principles to encompass a robust toolkit of quantitative assessment methods and practical metrics that enable the objective evaluation of chemical processes and products. Frameworks established by leading organizations, such as the American Chemical Society Green Chemistry Institute (ACS GCI), emphasize a systems-level mindset and the application of green chemistry principles to real-world industrial and research scenarios [24]. This competency-based approach ensures that educational programs equip scientists with the skills necessary to design safer chemicals, reduce environmental impacts, and advance sustainable drug development.

The validation of these educational outcomes is demonstrated through the scientist's ability to apply standardized metrics—such as E-factor, atom economy, and life cycle assessment—to quantify improvements in process sustainability. The growing emphasis on these competencies is reflected in major international conferences and grant programs, which highlight the need for interdisciplinary collaboration and the translation of green chemistry theory into practical, impactful applications [25] [26]. This article provides a comparative guide to the essential tools and methodologies that constitute the core of green chemistry knowledge, supported by experimental data and structured to help researchers and professionals objectively assess and validate the sustainability of their work.

Quantitative Metrics for Evaluating Chemical Processes

A core competency in green chemistry is the ability to evaluate and compare the environmental performance of chemical processes using standardized quantitative metrics. These metrics provide a foundation for making informed decisions in research and development, particularly in the pharmaceutical industry where process efficiency and waste reduction are critical. The following section compares key metrics and presents experimental data illustrating their application.

Comparative Analysis of Core Green Chemistry Metrics

Table 1: Key Metrics for Evaluating Chemical Process Greenness

| Metric Name | Definition | Industry Application | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E-Factor [27] | Total weight of waste per kg of product | Pharmaceutical industry: E-Factors range from 25 to >100 [27] | Simple, quick calculation; Highlights waste generation | Does not consider hazard or risk of waste |

| Atom Economy [27] | Molecular weight of desired product vs. total molecular weight of reactants | Ideal for evaluating synthetic route efficiency during discovery | Intrinsic measure of resource efficiency; Easy to calculate at reaction design stage | Does not account for yield, solvents, or energy |

| Process Mass Intensity (PMI) [27] | Total mass of materials used per kg of product | Closely related to E-Factor (PMI = E-Factor + 1); Widely used in pharmaceuticals [27] | Comprehensive; accounts for all input materials | Requires detailed knowledge of all process inputs |

| Eco-Scale [27] | Semi-quantitative tool penalizing hazards for reagents, solvents, and energy | Analytical and organic synthesis method assessment [27] | Holistic; incorporates yield, cost, safety, and energy use | More complex; involves subjective penalty assignments |

| Ecological Footprint (EF) [27] | Land area required to support a process/consumption (global hectares/unit) | Broad environmental impact assessment (e.g., CO2, water, land use) [27] | Comprehensive; includes multiple environmental pressures | Complex calculation; requires extensive data |

Experimental Protocol for Metric Calculation and Application

Protocol: Calculating E-Factor and Process Mass Intensity (PMI) for a Pharmaceutical Intermediate

This protocol outlines the steps for quantifying the waste efficiency of a chemical synthesis, using a hypothetical API intermediate as an example.

- Define System Boundaries: Clearly delineate the reaction steps included in the assessment (e.g., from starting material A to purified intermediate C).

- Record Input Masses: Accurately weigh and record the masses of all input materials, including:

- All reagents and catalysts

- All solvents (including those for reaction, work-up, and purification)

- Water used in the process

- Record Output Mass: Precisely weigh the final, dried product.

- Calculate Total Waste Mass:

- Option A (Input-Output): Total Waste (kg) = Total Mass of Inputs (kg) - Mass of Product (kg)

- Option B (Summation): Total Waste (kg) = Sum of masses of all non-product outputs (requires tracking all outputs)

- Compute Metrics:

- E-Factor = Total Waste (kg) / Mass of Product (kg)

- Process Mass Intensity (PMI) = Total Mass of Inputs (kg) / Mass of Product (kg)

- Note: PMI = E-Factor + 1

- Case Study Data: Application of this protocol to the synthesis of Sildenafil Citrate (Viagra) showed a reduction in E-Factor from 105 (discovery phase) to 7 (production phase) through solvent recovery and elimination of volatile solvents [27]. A future target of an E-Factor of 4 was set by eliminating specific reagents like titanium chloride [27].

Table 2: Experimental E-Factor Data Across Industry Sectors [27]

| Industry Sector | Typical Production Scale (tonnes) | E-Factor Range (kg waste/kg product) |

|---|---|---|

| Oil Refining | 10⁶ – 10⁸ | < 0.1 |

| Bulk Chemicals | 10⁴ – 10⁶ | < 1.0 – 5.0 |

| Fine Chemicals | 10² – 10⁴ | 5.0 – > 50 |

| Pharmaceuticals | 10 – 10³ | 25 – > 100 |

Advanced Tools for Solvent Selection and Assessment

Solvent selection is a critical competency in green chemistry, particularly in the pharmaceutical industry where solvents often constitute the largest mass fraction of a synthesis. The development of comprehensive, multi-criteria assessment tools represents an advanced skill set for scientists aiming to minimize environmental and health impacts.

The GEARS Metric: A Comprehensive Solvent Assessment Protocol

The Green Environmental Assessment and Rating for Solvents (GEARS) is a novel metric that integrates Environmental Health and Safety (EHS) criteria with Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) to provide a holistic solvent evaluation [28]. The methodology involves:

- Parameter Identification: Ten critical parameters were selected: toxicity, biodegradability, renewability, volatility, thermal stability, flammability, environmental impact, efficiency, recyclability, and cost [28].

- Quantitative Scoring: A defined scoring protocol (e.g., 0-3 points) based on specific thresholds for each parameter allows for objective solvent comparison [28].

- Software Implementation: The metric is integrated into a user-friendly software tool to provide transparent, data-driven solvent assessments [28].

Table 3: GEARS Assessment of Common Solvents [28]

| Solvent | Toxicity (LD50) | Biodegrad-ability | Renew-ability | Flamm-ability | Overall GEARS Score (/30) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benzene | Low (LD50 ~1 g/kg) [28] | Low | No (Fossil-based) | High | Very Low |

| Methanol | Moderate | High | No (Fossil-based) | High | Moderate |

| Acetonitrile | Low | Low | No (Fossil-based) | Moderate | Low |

| Ethanol | High (LD50 >2000 mg/kg) [28] | High | Yes (Bio-based) | High | High |

| Glycerol | High | High | Yes (Bio-based) | Low (Non-flammable) | High |

Experimental Protocol for Comparative Solvent Evaluation

Protocol: Applying the GEARS Framework to Solvent Selection for a Reaction

This protocol guides the use of a multi-parameter tool to select the greenest solvent for a specific chemical process.

- Define Process Requirements: Identify the key functional properties required for the reaction (e.g., polarity, boiling point, water miscibility).

- Generate Solvent Candidates: List all solvents that meet the basic process requirements.

- Gather Data for Each Parameter: For each candidate solvent, collect data for all GEARS (or similar guide) parameters from reliable sources (e.g., safety data sheets, scientific literature, LCA databases).

- Score Each Solvent: Apply the defined scoring thresholds to each parameter for every solvent.

- Calculate Total Score: Sum the scores across all parameters to generate a total greenness score.

- Compare and Select: Rank the solvents based on their total score. The solvent with the highest score that also meets all critical process requirements is the greenest choice.

- Case Study Outcome: Application of GEARS demonstrated that bio-based solvents like glycerol and ethanol achieve high overall scores due to their renewable feedstocks, low toxicity, and high biodegradability, making them superior sustainable alternatives to conventional fossil-based solvents like benzene and acetonitrile [28].

Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Green Chemistry

The practical implementation of green chemistry relies on a toolkit of specialized reagents, catalysts, and materials designed to reduce hazard and waste. The following table details key solutions essential for modern sustainable research and development.

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Green Chemistry

| Reagent/Material | Function in Green Chemistry | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Bio-based Solvents (e.g., Ethanol, Glycerol) [28] | Replace hazardous, fossil-based solvents; Derived from renewable feedstocks. | Extraction medium; Reaction solvent in synthesis. |

| Solid Acid Catalysts (e.g., Zeolites) | Replace liquid mineral acids; Enable easier separation, recycling, and less corrosive processes. | Friedel-Crafts acylation; Esterification reactions. |

| Metal Catalysts (e.g., Pd, Fe) | Enable catalytic (vs. stoichiometric) pathways, reducing reagent consumption and waste. | Cross-coupling reactions (Pd); Reduction reactions (Fe). |

| Ionic Liquids | Act as non-volatile, recyclable solvents and catalysts for specialized applications. | Cellulose dissolution; Electrolytes in batteries. |

| Enzymes (Biocatalysts) | Provide highly selective, efficient catalysis under mild, aqueous conditions. | Kinetic resolution of enantiomers; Biodegradable polymer synthesis. |

| CO₂-derived Polymers | Utilize waste CO₂ as a carbon feedstock, supporting a circular carbon economy. | Production of polycarbonates and polyurethanes. |

Integrated Workflow for Green Chemistry Assessment

A core competency for scientists is the integration of various metrics and tools into a coherent assessment strategy. The following diagram maps the logical workflow for evaluating and selecting a green chemical process, from initial design to comprehensive evaluation.

Diagram 1: Green Chemistry Process Assessment Workflow. This workflow outlines the key stages and decision points for holistically evaluating the sustainability of a chemical process, integrating simple and advanced metrics.

Implementing Effective Green Chemistry Curricula and Tools

The validation of green chemistry educational outcomes requires robust, industry-tested assessment frameworks that can quantitatively measure sustainability principles in practice. Among these frameworks, The Estée Lauder Companies (ELC) Green Score represents a significant advancement in translating green chemistry theory into actionable, quantifiable metrics for product formulation and development. This framework provides a standardized methodology for assessing the environmental and human health profiles of ingredients and formulations across extensive product portfolios. Unlike traditional assessment methods that often rely on qualitative evaluations, the Green Score employs a data-driven, hazard-based approach that enables formulators to make informed decisions about ingredient selection while maintaining performance standards [29] [30].

The development of the Green Score methodology addresses a critical gap in green chemistry education and practice: the need for clear, standardized guidance on how to select greener ingredients among expanding options of natural and synthetic alternatives. By publishing their methodology in a peer-reviewed journal, ELC has provided the scientific community with a transparent framework that balances inherent chemical hazards with supply chain considerations, creating a model that can be adopted, built upon, and scaled throughout the consumer products industry [29] [31]. This framework is particularly valuable for educational outcomes research because it demonstrates how theoretical green chemistry principles can be operationalized in practical decision-making contexts, bridging the gap between academic concepts and industrial application.

Estée Lauder's Green Score Framework: Methodology and Components

Core Architecture and Scoring Metrics

The ELC Green Score framework is built upon a foundation of eight individual metrics distributed across three critical sustainability domains: human health (HH), ecosystem health (ECO), and environmental endpoints (ENV). This comprehensive structure enables a multidimensional assessment of ingredient and formulation sustainability through a quantitative scoring system that distills complex chemical data into an accessible, actionable metric [29]. The framework's architecture is specifically designed to integrate green chemistry principles throughout the product development process, providing formulators with real-time sustainability assessments of their formulations [31].

The scoring methodology employs a hazard-based approach that examines ingredient and chemical component data obtained from manufacturers, open-source databases, and computer model estimates. These data are analyzed across the eight metrics, then averaged by category and further averaged to generate an overall Green Score. A distinctive feature of this framework is its incorporation of a certainty score that provides insight into the confidence level for each ingredient's Green Score, addressing the common challenge of data variability and uncertainty in sustainability assessments [30]. The system also intentionally disincentivizes the use of raw materials with low scores or insufficient data by weighting their impact to further reduce the overall score, thus encouraging transparency and continuous improvement in ingredient selection [30].

Table 1: Green Score Assessment Metrics and Domains

| Assessment Domain | Specific Metrics | Data Sources | Scoring Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human Health (HH) | Acute toxicity, Ocular toxicity, Dermal toxicity | Manufacturer data, Open-source databases, Computer models | Hazard-based evaluation averaged across three toxicity endpoints |

| Ecosystem Health (ECO) | Bioaccumulation, Persistence, Aquatic toxicity | Manufacturer data, Open-source databases, Computer models | Hazard-based evaluation averaged across three environmental fate endpoints |

| Environmental Endpoints (ENV) | Feedstock sourcing, Greenhouse gas emissions | Supplier data, Life cycle assessment, Standardized reporting | Evaluation of renewable sourcing and climate impact throughout supply chain |

Experimental Protocol and Implementation Workflow

The experimental protocol for applying the Green Score framework follows a systematic workflow that begins with data collection and culminates in formulation optimization. In the initial phase, comprehensive data on each ingredient is gathered from multiple sources, including safety data sheets, life cycle assessment databases, supplier sustainability reports, and computational modeling outputs. This multi-source approach ensures a robust dataset for evaluation while acknowledging the practical limitations of data availability across complex supply chains [30]. The data collection phase specifically prioritizes information relevant to the eight core metrics, with particular attention to verifiable and transparent data sources.

Once compiled, the data undergoes a normalization and weighting process that translates diverse measurements into a consistent scoring scale. The human health metrics (acute, ocular, and dermal toxicity) are averaged to generate a HH subscore, while the ecosystem health metrics (bioaccumulation, persistence, and aquatic toxicity) are averaged for an ECO subscore. The environmental metrics (feedstock sourcing and greenhouse gas emissions) are similarly processed to create an ENV subscore. These three subscores are then further averaged to produce the overall Green Score, providing a comprehensive sustainability profile while maintaining the visibility of performance across specific domains [29] [30]. The final implementation phase involves integrating these scores into formulation software, enabling R&D teams to run comparative analyses and identify opportunities for sustainability improvement while maintaining product performance and stability.

Comparative Analysis with Educational Assessment Frameworks

Green Chemistry Generic Comparison (GC)² Prompt

In educational settings, the Green Chemistry Generic Comparison (GC)² prompt serves as an open-ended assessment tool that asks students to identify factors they would consider when determining which of two reactions is greener [13]. This assessment approach was specifically developed to address the need for readily available instruments capable of eliciting valid and reliable data about green chemistry knowledge. Unlike the highly structured ELC Green Score, the (GC)² prompt employs a case comparison methodology that requires students to apply higher-order cognitive skills when evaluating chemical processes without the need for specific chemistry content knowledge [13].

The (GC)² prompt has demonstrated sensitivity for detecting gains in green chemistry knowledge in pre- and post-test conditions across general chemistry and organic chemistry courses. Psychometric analysis of student responses has revealed that while addressing certain green chemistry principles falls within typical student ability ranges, other principles exceed that range, providing valuable insights for curriculum development [13]. This assessment approach aligns with the American Chemical Society's 2023 guidelines for undergraduate chemistry programs, which now require that ACS-certified university curricula provide students with a "working knowledge" of green chemistry principles, including opportunities to assess chemical products and processes and design greener alternatives when appropriate [13].

Assessment of Student Knowledge of Green Chemistry Principles (ASK-GCP)

Another significant educational assessment framework is the Assessment of Student Knowledge of Green Chemistry Principles (ASK-GCP), a 24-item true-false instrument designed to measure undergraduate students' knowledge of the 12 green chemistry principles [13]. This assessment tool was developed to provide a standardized method for evaluating green chemistry learning outcomes across different educational interventions. The ASK-GCP instrument has demonstrated utility as a pre- and post-test, with evidence of reliability and validity when used with undergraduate organic chemistry students [13].

While the ASK-GCP offers practical advantages for rapid implementation and evaluation, its closed-ended format limits its ability to uncover student conceptions beyond the scope of its specific statements. Additionally, due to the nature of its statements, the instrument primarily assesses lower-order cognitive skills, in contrast to the higher-order thinking required by open-ended prompts like the (GC)² [13]. A shortened adapted form of the ASK-GCP instrument has been successfully employed to measure learning gains among Brazilian high school students, demonstrating its flexibility across different educational levels and contexts [13].

Table 2: Comparison of Green Chemistry Assessment Frameworks

| Framework Attribute | ELC Green Score | (GC)² Prompt | ASK-GCP Instrument |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Context | Industrial product development | Higher education | Higher education |

| Assessment Approach | Quantitative scoring of eight metrics | Open-ended case comparison | True-false knowledge assessment |

| Cognitive Level | Applied decision-making | Higher-order thinking skills | Lower-order thinking skills |

| Data Output | Numerical score (0-100 scale) | Qualitative conceptions | Quantitative knowledge score |

| Validation Method | Peer-reviewed publication & industry application | Psychometric analysis | Reliability and validity studies |

| Green Principles Covered | 8 specific endpoints across 3 domains | All 12 principles (student-dependent) | All 12 principles |

| Implementation Scale | Global corporate portfolio | Course-level assessment | Course-level assessment |

Validation Pathways and Experimental Data

Industrial Validation and Scientific Peer Review

The ELC Green Score framework has undergone rigorous validation through multiple pathways, beginning with evaluation by ELC's Green Chemistry Scientific Advisory Board, comprised of academic experts in green chemistry from key global regions including China, Europe, North America, and Latin America [31]. This external validation ensured the scientific robustness of the methodology while incorporating diverse perspectives from the international scientific community. The framework subsequently underwent the traditional peer-review process through publication in the Royal Society of Chemistry's Green Chemistry journal, where it was warmly received by reviewers and editorial board members [29] [31].

The practical validation of the Green Score framework comes from its extensive application across ELC's entire product portfolio. Green Scores have been calculated for all individual materials and formulations across ELC's in-house skincare, hair care, and makeup portfolios, demonstrating the framework's scalability and adaptability to diverse product categories [29] [31]. Additionally, all formulators throughout the organization have been trained to use the quantitative tool to assess the sustainability of their formulations in real time, creating a robust dataset of practical implementation experiences that further validates the framework's utility in industrial decision-making contexts. Dr. Paul Anastas, Professor in the Practice of Chemistry for the Environment at Yale University and co-author of the manuscript, emphasized that the tool "has taken a concept that is quite complex and distilled it into a useful metric that not only assesses products that already exist but also informs how new, higher-performing products can be designed in the future" [31].

Educational Validation Studies

In educational contexts, the (GC)² prompt has been validated through comprehensive psychometric analysis of responses collected from students enrolled in organic chemistry I and II lecture and laboratory courses (N = 642) and from students enrolled in general chemistry II lecture courses (N = 272) [13]. This large-scale validation study demonstrated the prompt's sensitivity for detecting gains in green chemistry knowledge and its ability to elicit student conceptions of green chemistry principles. The research found that while addressing certain green chemistry principles was within students' ability range, other principles exceeded that range, providing valuable insights for curriculum development and targeted instructional interventions.

The validation of educational assessment frameworks has revealed significant challenges in green chemistry education, including the identification that most reported teaching experiences describe only occasional, targeted curriculum insertions with poorly evaluated curricular outcomes [13]. This assessment gap has been partially attributed to the limited availability of readily available assessments capable of eliciting valid and reliable data about green chemistry knowledge, highlighting the critical importance of developing robust, validated frameworks like the (GC)² prompt and ASK-GCP instrument for advancing green chemistry education research [13].

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

The implementation of green chemistry assessment frameworks requires specific research reagents and methodological tools to ensure consistent, reproducible results. For the ELC Green Score framework, the essential components include both data sources and analytical approaches that collectively enable comprehensive sustainability assessment across the eight core metrics. These research reagents serve as fundamental tools for both industrial and educational implementation of green chemistry assessment protocols.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Green Chemistry Assessment

| Research Reagent | Function in Assessment | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Manufacturer Safety Data | Provides toxicity and hazard information | Human health metric calculation |

| Open-Source Chemical Databases | Supplies data on persistence, bioaccumulation | Ecosystem health metric calculation |

| Computer Modeling Software | Estimates environmental fate and toxicity | Filling data gaps for novel compounds |

| Life Cycle Assessment Tools | Calculates greenhouse gas emissions | Environmental endpoint evaluation |

| Supply Chain Reporting Frameworks | Tracks feedstock sourcing and renewability | Environmental metric assessment |

| Certainty Scoring Algorithm | Quantifies confidence in assessment results | Quality assurance of Green Score |

The research reagents identified in Table 3 represent the essential tools required for implementing robust green chemistry assessment frameworks. Manufacturer safety data provides critical information on acute, ocular, and dermal toxicity needed for the human health metrics, while open-source chemical databases supply information on environmental fate parameters including persistence, bioaccumulation potential, and aquatic toxicity [30]. Computer modeling software plays an increasingly important role in filling data gaps for novel compounds or when experimental data is limited, using quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models to estimate environmental fate and toxicity parameters based on chemical structure [30].

For the environmental endpoints, life cycle assessment tools enable the calculation of greenhouse gas emissions throughout a product's life cycle, while standardized supply chain reporting frameworks track feedstock sourcing and renewability information [30]. Finally, the certainty scoring algorithm represents a methodological innovation that quantifies confidence in assessment results based on data quality and completeness, providing essential context for interpreting Green Scores and identifying priority areas for data improvement [30]. Together, these research reagents form a comprehensive toolkit for implementing the Green Score framework and similar assessment approaches in both industrial and educational settings.

The comparative analysis of industry-tested and educational assessment frameworks reveals both convergence and specialization in approaches to validating green chemistry outcomes. The ELC Green Score framework demonstrates how complex sustainability considerations can be distilled into actionable metrics for industrial decision-making, while educational assessment tools like the (GC)² prompt and ASK-GCP instrument provide validated methods for measuring learning outcomes and conceptual understanding. Each framework offers distinct advantages for specific contexts, with the industrial-focused Green Score providing quantitative scoring for comparative analysis and the educational assessments offering insights into student thinking and conceptual development.

Future development of green chemistry assessment frameworks will likely focus on expanding endpoint coverage to include additional human health and ecosystem concerns such as endocrine disruption, which is not currently included in the Green Score due to limited data availability [30]. Additionally, standardization of supply chain reporting and frameworks may enable inclusion of additional environmental endpoint data, such as manufacturing waste generation and use of hazardous process chemicals [30]. In educational contexts, there is a growing need to develop assessments that measure higher-order cognitive skills and systems thinking abilities essential for addressing complex sustainability challenges [13] [3]. As green chemistry continues to evolve, assessment frameworks must similarly advance to provide comprehensive, validated approaches for measuring progress toward sustainability goals across industrial, educational, and research contexts.

The integration of Green Chemistry principles into scientific education and practice is essential for advancing sustainable drug development. This guide examines two critical educational modules—toxicology for chemists and safer solvent selection—within the broader context of validating green chemistry educational outcomes. As research demonstrates, effective educational approaches like Problem-Based Learning (PBL) significantly enhance understanding of Green Chemistry principles among students, enabling them to better recognize and apply these concepts in real-world contexts such as pharmaceutical manufacturing [32]. This validation of educational outcomes ensures that researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals are equipped with the practical knowledge needed to design safer molecules and implement sustainable chemical processes.

Toxicology for Chemists: Curriculum Modules and Implementation

Core Toxicology Concepts for Molecular Design

The Toxicology for Chemists curriculum, developed by Beyond Benign, addresses a critical gap in conventional chemistry education by providing chemists with knowledge of how chemical structures and properties impact toxicity and environmental effects [33]. This understanding enables molecular designers to prevent hazards at the earliest stages of chemical product development rather than managing risks after products have been created. The curriculum represents a strategic response to the finding that traditional chemistry education often lacks foundational training in how to identify and address hazards when designing molecules [34].

The complete curriculum comprises 11 comprehensive modules that can be integrated into existing chemistry courses or delivered as stand-alone units. Each module contains approximately three hours of content with supporting materials including lecture slides, lesson plans, homework assignments, and supplementary readings [33]. This flexible structure allows educators to incorporate toxicology concepts progressively throughout chemistry programs rather than treating toxicology as a separate discipline.

Implementation Models for Toxicology Education

Four primary implementation models have emerged in higher education settings, particularly among institutions participating in the Green Chemistry Commitment program [33]:

- Student-Led Courses: Faculty and students learn toxicology together through special topics courses or student-research courses, with students researching topics and generating reports.

- Stand-Alone Courses: Dedicated toxicology courses, often co-taught across departments (e.g., chemistry faculty partnering with biochemistry or toxicology faculty).

- Seminar Series: Incorporating toxicology topics into existing seminar programs by inviting outside experts from industry or academia.

- Integration into Chemistry Courses: Embedding toxicology concepts within existing chemistry courses to reinforce core chemical principles.

Table: Toxicology for Chemists Curriculum Modules

| Module Number | Module Title | Key Content Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Module 1 | The History and Principles of Toxicology | Foundational concepts and historical context |

| Module 2 | Understanding Hazard and Risk | Distinction between hazard and risk assessment |

| Module 3 | Toxicokinetics and Toxicodynamics | Chemical movement and effects in biological systems |

| Module 4 | Reaction Mechanisms in Toxicology | Molecular mechanisms of chemical toxicity |

| Module 6 | Toxicity of Metals | Specialized focus on metal toxicity |

| Module 7 | Environmental Fate, Persistence, and Biodegradation | Chemical behavior in environments |

| Module 8 | Environmental Toxicology | Ecosystem impacts of chemicals |

| Module 9 | Ecotoxicology | Effects on ecological systems and organisms |

| Module 10 | Predictive Toxicology | Modeling and predicting toxicological endpoints |

| Module 11 | Structure-Activity Relationships | Linking chemical structure to biological activity |

Safer Solvent Guides: Experimental Validation in Pharmaceutical Applications

Dichloromethane Replacement Initiative

A comprehensive three-year research initiative demonstrated the viability of replacing dichloromethane (DCM) with safer alternatives in pharmaceutical manufacturing [35]. DCM has been associated with serious health concerns including cancer and central nervous system damage, and it persists in aquatic environments with a half-life exceeding 18 months [35]. The purification of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) often requires column chromatography, a process that traditionally uses DCM, thereby exposing workers to health risks and generating chlorinated solvent waste.

The research collaboration between TURI, UMass Lowell, and Johnson Matthey (now Veranova) employed multiple assessment frameworks to evaluate potential alternatives [35]:

- GreenScreen for Safer Chemicals: A comparative chemical hazard assessment method.

- Pollution Prevention Options Analysis System (P2OASYS): A toxic use reduction evaluation tool.

- GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) Solvent Selection Guide: A pharmaceutical industry standard for solvent evaluation.

All evaluated safer alternatives demonstrated superior ratings across these assessment frameworks compared to DCM while maintaining comparable or better performance in pharmaceutical purification processes.

Experimental Protocols for Solvent Evaluation

Thin-Layer Chromatography (TLC) Screening Protocol

- Objective: Identify alternative solvents or solvent blends with separation performance comparable to DCM.

- Methodology: TLC was employed as an initial screening technique using silica gel plates. Researchers applied samples of target compounds to plates and developed them in various solvent systems.

- Analysis: Retention factor (Rf) values and separation resolution were calculated and compared against DCM benchmarks.

- Outcome: Several safer solvent blends, particularly mixtures of methyl acetate and ethyl acetate, demonstrated adequate TLC performance comparable to DCM, guiding selection for further column chromatography testing [35].

Column Chromatography Evaluation Protocol

- Objective: Quantify separation performance and efficiency of safer solvents in purifying active pharmaceutical ingredients.

- API Models: Ibuprofen, aspirin, and acetaminophen were selected as model compounds with caffeine as a model impurity.

- Chromatography Setup: Lab-scale columns packed with silica gel stationary phase.

- Mobile Phases: Tested solvents included methyl acetate, ethyl acetate, acetone, and 1,3-dioxolane alongside DCM control.

- Performance Metrics: API recovery percentage, purity levels, E-factor values (environmental factor measuring waste per product unit), and operational flexibility [35].

Comparative Performance Data for Safer Solvents

Table: Experimental Results for Safer Solvent Alternatives to Dichloromethane

| Solvent | Health & Safety Profile | Environmental Impact | Economic Cost vs. DCM | API Recovery | E-Factor | Operational Flexibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dichloromethane (DCM) | High hazard (cancer, neurotoxicity) | High persistence (half-life >18 months) | Reference | Baseline | Baseline | Baseline |

| Methyl Acetate | Safer (better GreenScreen, P2OASys, GSK ratings) | Lower environmental impact | Lower cost | Higher | Lower | Comparable |

| Ethyl Acetate | Safer (better GreenScreen, P2OASys, GSK ratings) | Lower environmental impact | Slightly higher | Higher | Lower | Larger operation window |

| Acetone | Safer (better GreenScreen, P2OASys, GSK ratings) | Lower environmental impact | Lower cost | Comparable | Lower | Comparable |

| 1,3-Dioxolane | Safer (better GreenScreen, P2OASys, GSK ratings) | Lower environmental impact | Slightly higher | Comparable | Lower | Comparable |

Educational Framework and Learning Validation

Problem-Based Learning Methodology

Research conducted through a dedicated Green Chemistry course implemented PBL to evaluate its effect on students' understanding of Green Chemistry principles [32]. The instructional approach included:

- Case Study Analysis: Students examined real-world industrial redesign processes, including bio-based butylene glycol production and enzymatic treatment of paper, to identify applied Green Chemistry principles.

- Methodology Comparison: Students evaluated four different synthesis methods for acetanilide to determine the "greenest" approach considering multiple sustainability dimensions.

- Assessment Tools: The ASK-GCP (Assessment of Student Knowledge of Green Chemistry Principles) instrument was administered before and after the course to measure learning gains [32].

Validated Learning Outcomes

The PBL approach demonstrated significant educational benefits while revealing specific challenges:

- Enhanced Principle Recognition: Students showed improved ability to identify and justify the relevance of Green Chemistry principles in industrial contexts, particularly in bio-based material production and enzymatic processes [32].

- Conceptual Challenges: Certain principles, including atom economy and catalysis, presented learning difficulties, indicating the need for targeted instructional support in these areas.

- Practical Application Skills: Students developed competence in analyzing benefits and drawbacks of different methodologies for producing the same substance, directly translating to pharmaceutical development scenarios [32].

PBL Educational Framework: This diagram illustrates the Problem-Based Learning methodology used to validate Green Chemistry educational outcomes, connecting instructional elements to measured competencies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Essential Materials for Toxicology and Solvent Research

Table: Key Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Educational Context |

|---|---|---|

| Silica Gel Stationary Phase | Chromatographic separation of compounds | Demonstrates principles of green analytical chemistry |

| Methyl Acetate | Safer alternative solvent for chromatography | Illustrates solvent substitution principles |

| Ethyl Acetate | Bio-based safer solvent option | Shows renewable feedstock application |

| GreenScreen Assessment Tool | Chemical hazard evaluation framework | Teaches systematic hazard assessment methods |

| P2OASYS | Pollution prevention evaluation system | Demonstrates quantitative environmental impact assessment |

| TLC Plates | Rapid solvent screening methodology | Teaches preliminary evaluation techniques |

| Model APIs (Ibuprofen, Aspirin) | Standardized test compounds for method validation | Provides pharmaceutically relevant case studies |

The validated educational frameworks for toxicology and solvent selection provide drug development professionals with critical tools for implementing Green Chemistry principles in research and manufacturing settings. The Problem-Based Learning approach has demonstrated effectiveness in helping students understand complex concepts like atom economy and catalysis while developing practical skills in evaluating process "greenness" [32]. The experimental data on safer solvent alternatives offers scientifically rigorous replacement strategies for hazardous chemicals like dichloromethane, with methyl acetate and ethyl acetate showing particularly favorable performance and safety profiles [35]. As green chemistry education continues to evolve, these integrated teaching modules provide essential training for creating more sustainable pharmaceutical manufacturing processes that align with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals [34].

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) represent a class of nearly 5,000 synthetic chemical compounds characterized by multiple fluorine atoms attached to an alkyl chain, conferring exceptional durability, thermal stability, and oil- and water-repellent properties [36]. These "forever chemicals" pose significant environmental and health challenges due to their extreme persistence in the environment and biological systems, with studies indicating potential associations with increased cholesterol, reduced vaccine effectiveness in children, and increased cancer risk [37] [36]. Regulatory pressure on PFAS has intensified globally, with the European Union and United States implementing stringent restrictions, including the US Environmental Protection Agency's establishment of remarkably low acceptable concentration levels (as low as 4 parts per trillion for specific PFAS) in drinking water [36]. This evolving regulatory landscape, combined with growing scientific understanding of PFAS risks, has accelerated the search for safer alternatives across industrial sectors and stimulated innovation in remediation technologies for contaminated sites [38] [39].

The transition away from PFAS aligns with the principles of green chemistry, which emphasize designing chemical products and processes that reduce or eliminate hazardous substance use and generation. This case-based analysis examines current PFAS alternatives and treatment technologies within the context of green chemistry education, providing a framework for evaluating sustainable material selection and environmental remediation strategies. By examining the technical performance, commercial availability, and implementation challenges of PFAS substitutes and treatments, this analysis aims to support educational outcomes focused on sustainable chemical design and implementation.

PFAS Alternatives: Comparative Analysis and Performance Evaluation

Industry-Specific PFAS Applications and Alternative Materials