Sustainability by Design in Drug Development: Strategies for Integrating Eco-Innovation into Pharmaceutical R&D

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to integrate Sustainability by Design (SbD) principles into pharmaceutical development.

Sustainability by Design in Drug Development: Strategies for Integrating Eco-Innovation into Pharmaceutical R&D

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to integrate Sustainability by Design (SbD) principles into pharmaceutical development. It explores the foundational rationale for SbD, detailing how up to 80% of a drug's environmental impact is locked in during early R&D. The content covers practical methodological approaches, including Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) and green chemistry, and addresses common implementation challenges and optimization strategies. Furthermore, it examines validation frameworks, emerging metrics, and comparative analyses of sustainable innovations, offering a actionable guide for embedding environmental stewardship into the core of drug development from discovery to commercialization.

Why Sustainability by Design is the Future of Pharmaceutical R&D

In the competitive and critically important field of drug development, Sustainability by Design represents a fundamental shift from treating sustainability as a secondary concern to integrating it as a core principle from the very outset of the research and development process. It is a proactive methodology that embeds environmental, economic, and social considerations into the earliest stages of process design, rather than attempting to mitigate negative impacts after the fact. Within the context of bioprocess development, this means designing manufacturing processes that are not only efficient and cost-effective but also minimize environmental footprint and resource consumption [1]. The imperative for this approach is clear: evidence suggests that up to 80% of a drug's final environmental impact is locked in during the early stages of process design [1]. Furthermore, with a significant portion of a pharmaceutical company's emissions—from 42% to 47%—coming from purchased goods and services, focusing on sustainable inputs and processes offers a substantial lever for change [1]. For researchers and scientists, this transforms sustainability from a buzzword into a tangible and critical dimension of experimental and process design, alongside traditional metrics of yield, purity, and efficacy.

Core Principles and Experimental Frameworks

Operationalizing Sustainability by Design requires structured frameworks and assessment methodologies. While specific protocols for direct laboratory experimentation are still emerging, current research leverages comprehensive surveys and qualitative analyses to identify priorities and trade-offs.

A Multi-Pillar Assessment Framework

A pivotal study deployed an online survey to 447 international multistakeholders (from industry, academia, healthcare, and patient groups) to capture perceptions on integrating the three pillars of sustainability—environmental, economic, and social—into clinical trial design decisions [2]. The methodology was designed to quantify priorities and evaluate the perceived sustainability of traditional centralized clinical trials (CTs) versus decentralized clinical trials (DCTs).

Experimental Protocol Overview [2]:

- Objective: To identify multistakeholder opinions on sustainability priorities and trade-offs when deciding between a traditional CT and a DCT.

- Survey Deployment: Deployed via ETH Zurich's SurveySelect software in December 2022, closing on January 31, 2023.

- Participant Cohort: 447 participants from diverse geographies (Americas, Europe, Asia, Oceania) and stakeholder groups (53.2% from industry, including pharmaceuticals, biotech, and devices).

- Data Analysis: Combined qualitative and quantitative analysis. Quantitative data were summarized using frequency and percentages, and qualitative data were processed using content analysis methodology to identify core patterns.

The study identified clear priorities within each sustainability pillar, as summarized below for the overall cohort [2].

Table 1: Key Sustainability Priorities in Clinical Trial Design

| Sustainability Pillar | Top Priority | Percentage Ranking it as Top Priority |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental | Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Emissions | 22.4% |

| Economic | Trial Probability of Success | 15.0% |

| Social | Patient Convenience | 23.3% |

The Safe and Sustainable by Design (SSbD) Framework

Another critical framework is the Safe and Sustainable by Design (SSbD), which combines considerations of human safety, environmental safety, and sustainability throughout the innovation process [3]. In the context of drug development, this involves a tiered assessment of chemicals, materials, and processes. The European Commission's Joint Research Centre (JRC) and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) have proposed leading SSbD implementation frameworks, though they differ in critical aspects such as their reliance on hazard-based versus risk-based assessments [3]. The core challenge is integrating these principles into a coherent, iterative workflow for researchers.

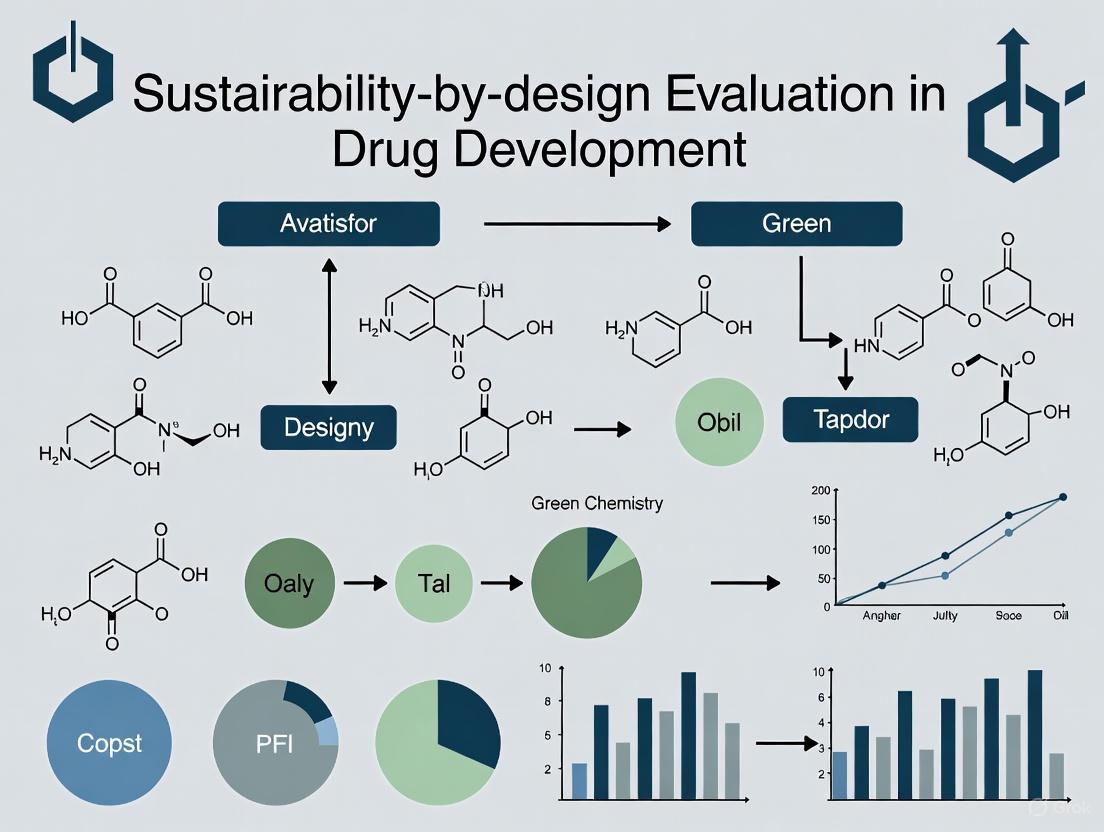

The following diagram visualizes a synthesized SSbD workflow for drug development, integrating concepts from these prominent frameworks:

Quantitative Data: Comparing Traditional and Decentralized Clinical Trials

The survey research provides quantitative data comparing the perceived sustainability of traditional and decentralized clinical trials across the three pillars. Furthermore, it offers a glimpse into the empirical carbon footprint data available in literature, though direct comparisons are complicated by variations in trial size, duration, and type [2].

Table 2: Perceived Sustainability and Carbon Footprint of Trial Designs

| Trial Design | Perceived as More Sustainable (Overall Cohort) | Reported Carbon Footprint (CO2e) from Literature | Trial Context (Source) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Centralized CT | Minority of respondents | 1,637 CO2e | Phase 3, Oncology (n=688) [2] |

| 1,437 CO2e | Phase 3, Respiratory (n=2000) [2] | ||

| Decentralized CT (DCT) | Majority of respondents | 2,498 CO2e | Phase 3, Cardiovascular (Hybrid, n=4744) [2] |

| 17.65 CO2e | Phase 1 (Hybrid, n=28) [2] |

The data indicates a strong stakeholder perception that DCTs are more sustainable across all pillars [2]. However, the available carbon footprint data reveals significant variability and highlights the critical need for more standardized measurement and reporting to enable valid comparisons. The high emissions from a large cardiovascular hybrid trial underscore that decentralization alone is not a silver bullet; overall trial design and scale remain dominant factors.

The Scientist's Toolkit for Sustainable Bioprocess Development

For the drug development scientist, implementing Sustainability by Design requires focusing on specific unit operations and process inputs. The following table details key levers and considerations for designing more sustainable bioprocesses.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions and Process Levers for Sustainable Bioprocess

| Tool / Process Lever | Function / Description | Sustainability Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| High-Titer Cell Lines | Cell lines engineered for high productivity. | Drives higher throughput in a smaller footprint, reducing resource use per unit of output [1]. |

| Chemically Defined Media | Media formulated with known components, without animal-derived ingredients. | Allows for sourcing from sustainability-minded suppliers; reduces contamination risk and batch variability [1]. |

| Process Intensification | Strategies like continuous processing or high-density cell banking. | Reduces manufacturing footprint, resource consumption, and waste generation [1]. |

| Water Grade Selection | Using an appropriate grade of purified water (e.g., Reverse Osmosis vs. WFI). | Highly purified water is resource-laden; selecting a lower grade for non-critical steps drastically reduces carbon footprint [1]. |

| Circular Waste Streams | Partnering with recyclers to handle single-use bioprocess containers. | Diverts plastic waste from landfills or incineration, closing the material loop [1]. |

The implementation of these tools can be conceptualized as an integrated workflow from cell line development to waste management, with sustainability checkpoints at each stage.

The evidence demonstrates that Sustainability by Design is an empirically-grounded paradigm, not an abstract ideal. For drug development professionals, it provides a structured approach to navigating critical trade-offs between environmental impact, economic viability, and social value. The data reveals a clear stakeholder preference for the sustainability potential of decentralized trials, while also highlighting the need for more robust and standardized lifecycle assessment data across all trial types [2]. In bioprocessing, the integration of sustainable practices—from cell line selection to waste management—offers tangible benefits in reducing carbon emissions, resource use, and cost [1]. The ultimate success of this approach hinges on its adoption not as a standalone program, but as an integral component of the scientific decision-making process, empowering every scientist and engineer to assess the sustainability implications of their work alongside technical and cost considerations [1].

In the competitive and highly regulated landscape of drug development, the concept of sustainability-by-design represents a paradigm shift toward integrating environmental considerations into the earliest stages of bioprocess development. This approach is not merely about incremental improvements but is founded on a critical, data-driven premise: approximately 80% of a drug's final environmental impact is locked in during the early stages of process design [4]. Once a process and its inputs are defined in a regulatory dossier, making changes becomes significantly more challenging and costly. This early phase, therefore, constitutes a "critical window of influence," presenting a narrow but powerful opportunity to embed sustainability into the core of biopharmaceutical manufacturing.

This guide objectively compares key bioprocess technologies and strategies available to scientists and engineers, providing the experimental data and methodologies needed to make informed, sustainability-focused decisions during research and development (R&D) and chemistry, manufacturing, and controls (CMC) phases.

Quantitative Comparison of Sustainable Bioprocess Technologies

The following tables summarize experimental data and sustainability metrics for key process technologies and materials, providing a direct comparison for decision-making.

Table 1: Comparison of Upstream Processing Technologies

| Technology | Key Performance/Sustainability Metric | Experimental Outcome | Impact on Environmental Footprint |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Titer Cell Lines [4] | Volumetric Productivity | Higher throughput of product in a smaller footprint | Lower Cost of Goods (COGs) and simultaneous reduction of emissions |

| Chemically Defined Media [4] | Contamination Risk & Sourcing | Reduced contamination risks and sourcing from sustainability-minded suppliers | Lower waste generation and more controlled, consistent sourcing |

| Single-Use Bioreactors (High Turndown Ratio) [4] | Seed Train Efficiency | Skipping 6-8 days of standard GMP expansion; seeding at low volumes and expanding in the same unit operation | Saves time, money, and resources (plastic, water, media) |

| Centrifugation vs. Depth Filtration [4] | Process Waste & Yield | Reduced waste and processing times while improving yields | Lower solid waste generation and reduced processing energy |

Table 2: Comparison of Downstream & Support Technologies

| Technology | Key Performance/Sustainability Metric | Experimental Outcome | Impact on Environmental Footprint |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Capacity Chromatography Resins [4] | Buffer Consumption | Reduced buffer volumes per unit of product purified | Lower water consumption and reduced waste buffer disposal |

| Membrane Separations [4] | Process Time & Buffer Volume | Replaces larger chromatography columns that use large buffer volumes and long run times | Significant reduction in water and chemical use; smaller facility footprint |

| Water Purity Selection [4] | Carbon Footprint per Liter | Using lower quality purified water for media makeup and buffer creation vs. Water for Injection (WFI) | Large impactful improvements by avoiding carbon-intensive WFI generation steps |

| Single-Use Bioprocess Container (BPC) Recycling [4] | Waste Diversion | A specific program diverted ~400,000 lbs of plastic from landfills/incineration | Converts waste into high-quality plastic lumber, enabling a circular economy |

Experimental Protocols for Sustainability Assessment

To generate the comparative data required for evidence-based decision-making, standardized experimental protocols are essential. The following methodologies provide a framework for assessing the sustainability of process options.

Protocol for Lifecycle Assessment (LCA) in Early Process Development

Purpose: To quantify and compare the environmental impacts (e.g., carbon footprint, water consumption, waste generation) of different process designs or unit operations during the development phase.

Methodology:

- Goal and Scope Definition: Define the functional unit (e.g., "per gram of monoclonal antibody") and system boundaries (e.g., from cell culture initiation to purified drug substance).

- Inventory Analysis (LCI): For each unit operation within the scope, collect data on all relevant inputs and outputs.

- Inputs: Quantify energy (kWh), water (L), raw materials (g), and single-use components (count).

- Outputs: Measure product mass (g) and waste streams, including solid waste (kg) and liquid effluents (L).

- Impact Assessment (LCIA): Use LCA software (e.g., OpenLCA, SimaPro) to translate inventory data into environmental impact categories, such as Global Warming Potential (kg CO₂-equivalent) and Water Scarcity Potential.

- Interpretation: Compare the LCA results of different process intensification strategies (e.g., perfusion vs. fed-batch) or technology choices (e.g., chromatography resins) to identify the option with the lowest environmental impact.

Protocol for Evaluating Resource Efficiency in Intensified Processes

Purpose: To empirically measure the resource consumption and waste generation of a proposed intensified bioprocess against a standard baseline process.

Methodology:

- Baseline Establishment: Run a control process (e.g., standard fed-batch, traditional chromatography) and record key metrics: process duration, product titer/yield, water consumption, buffer/media volume, and kWh consumed.

- Test Process Evaluation: Execute the intensified process (e.g., high-seed N-1 perfusion, connected or continuous downstream processing) under comparable scale and conditions.

- Data Normalization and Comparison: Normalize all resource and output data to the functional unit (e.g., per gram of product). Compare the test and baseline processes.

- Statistical Analysis: Perform statistical analysis (e.g., t-test) on triplicate runs to determine if improvements in resource efficiency (e.g., 40% reduction in water use) are significant.

Visualization of Sustainability-by-Design Workflows

Integrating sustainability assessment into the bioprocess development workflow requires a clear, logical pathway. The following diagram maps this critical decision-making process.

Diagram 1: Sustainability Integration in Process Development

This workflow illustrates the critical path for embedding sustainability into bioprocess development, highlighting the early phase where 80% of the environmental impact is determined.

The choice of cell line is one of the most upstream and influential decisions. The diagram below outlines the experimental workflow for selecting and optimizing a cell line for both productivity and sustainability.

Diagram 2: Cell Line Development for Sustainability

This workflow shows the key experimental stages for selecting a cell line based on criteria that reduce environmental impact, such as high productivity and compatibility with defined media.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Success in sustainable bioprocess development relies on specific tools and materials. The following table details key research reagent solutions and their functions.

Table 3: Essential Materials for Sustainable Bioprocess Development

| Research Reagent/Material | Function in Sustainable Bioprocessing |

|---|---|

| Chemically Defined Media [4] | Eliminates animal-derived components, reduces batch variability, and lowers contamination risk, leading to more consistent processes and less waste. |

| High-Capacity Chromatography Resins [4] | Increases product binding capacity, significantly reducing the volume of buffers and resins needed per batch, thereby saving water and chemicals. |

| Single-Use Bioreactors (SUBs) [4] | Avoids the massive water and energy demands of cleaning-in-place (CIP) and steam-in-place (SIP) systems associated with stainless-steel equipment. |

| Recyclable Single-Use Bioprocess Containers (BPCs) [4] | Provides the operational benefits of single-use systems while enabling a circular waste stream, diverting plastic from landfills. |

| Alternative Water Types (e.g., RO Water) [4] | Using appropriate water purity (e.g., Reverse Osmosis) for non-critical applications avoids the high carbon footprint of producing Water for Injection (WFI). |

For drug development professionals, the evidence is clear: the most significant gains in environmental sustainability are achievable only by focusing on the critical window of influence in early process design. The comparative data, experimental protocols, and workflows presented here provide a foundational toolkit for making informed decisions that align with the principles of sustainability-by-design. By prioritizing high-titer processes, resource-efficient technologies, and circular economy principles from the outset, the biopharmaceutical industry can simultaneously advance its economic goals and environmental responsibilities, turning sustainability from a compliance challenge into a competitive advantage [4].

The global pharmaceutical industry faces a pivotal moment, compelled to integrate sustainability into its core business strategies by a powerful convergence of ethical responsibility and financial imperative. The industry accounts for approximately 4.4% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions [5], with a carbon footprint forecasted to triple by 2050 if left unchecked [6]. This environmental impact translates into tangible business risks and opportunities. Investors are increasingly allocating capital to companies with robust environmental, social, and governance (ESG) credentials, while regulators worldwide are implementing stricter environmental mandates. Furthermore, a compelling economic case is emerging: sustainable practices in drug development and manufacturing are proving to be drivers of cost efficiency, risk mitigation, and competitive advantage. This article examines the business and ethical case for "sustainability-by-design," a paradigm that integrates environmental, economic, and social considerations into every stage of the drug development lifecycle, from initial compound design to clinical trials and commercial manufacturing.

The Quantitative Landscape: Environmental Impact and Business Metrics

To objectively assess the industry's position and progress, it is essential to examine key quantitative metrics. The data reveal both the scale of the challenge and the tangible benefits of intervention.

Table 1: Pharmaceutical Industry Environmental Impact and Performance Metrics

| Metric Category | Specific Metric | Value or Finding | Source/Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Impact | Contribution to Global GHG Emissions | 4.4% | [5] |

| Emission Intensity (vs. Automotive Industry) | 55% higher | 48.55 tCO2e / million USD (2015) [6] | |

| Emission Distribution | Scope 3 Share of Total Pharma GHG Emissions | Up to 75% - 90% | [5] [6] |

| Upstream Share of Scope 3 Emissions | ~60% (approx. three-fifths) | Production/transport of purchased goods [6] | |

| Corporate Commitments | Top 100 Pharma Companies Committed to Net-Zero by 2050 | 46% (by revenue) | [6] |

| Companies on track for Scope 1/2 Reductions | 11-15 out of top 100 | As of a 2023 study [6] |

Table 2: Business and Economic Drivers for Sustainable Practices

| Business Driver | Sustainable Strategy | Business Outcome | Source/Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operational Efficiency | Process Intensification (e.g., higher titer processes) | Lowers Cost of Goods (COGs) and reduces emissions | [5] |

| Recycling Solvents & Catalysts in API Manufacturing | Measurable resource and carbon footprint reduction | [5] | |

| Regulatory & Market Access | Adherence to EU Packaging & Packaging Waste Regulation | Future-proofs market access; avoids penalties | Mandates recyclability by 2035 [7] |

| Meeting Payer Expectations | Growing inclusion of sustainability criteria in tenders | [7] | |

| Investor Appeal | Strong ESG Performance | Attracts investment; enhances company reputation | [6] |

| Risk Mitigation | Addressing Scope 3 Emissions | Manages a significant regulatory and reputational risk | Accounts for the vast majority of emissions [5] [6] |

Experimental and Analytical Protocols for Sustainability Assessment

Evaluating sustainability requires robust, data-driven methodologies. The following protocols are emerging as standards for quantifying environmental impact and informing decision-making.

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) for Drug Products

A Life Cycle Assessment is a comprehensive methodology for evaluating the environmental impacts associated with all stages of a product's life, from raw material extraction ("cradle") to end-of-life disposal ("grave").

Detailed Protocol:

- Goal and Scope Definition: Define the purpose of the LCA and the system boundaries (e.g., "cradle-to-gate" for API manufacturing or "cradle-to-grave" for a finished drug product including patient use and disposal). The functional unit (e.g., per kilogram of API or per single dose administered) must be clearly specified.

- Life Cycle Inventory (LCI): Compile a quantitative inventory of all energy and material inputs (e.g., raw materials, solvents, electricity, water) and environmental outputs (e.g., air emissions, water emissions, solid waste) within the defined system boundaries. This often involves primary data from manufacturing processes and secondary data from LCA databases.

- Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA): Translate the LCI data into potential environmental impact categories. Key categories for pharmaceuticals include Global Warming Potential (kg CO2 equivalent), Water Use, Resource Depletion, and Ecotoxicity.

- Interpretation: Analyze the results to identify environmental "hotspots," assess uncertainties, and provide conclusions and recommendations for reducing impact. This data can guide process optimization, material selection, and supply chain engagement [5] [7].

Comparative Analysis of Clinical Trial Designs

A growing body of research uses quantitative and qualitative surveys to compare the sustainability of traditional centralized clinical trials (CTs) with decentralized clinical trials (DCTs).

Detailed Protocol from Recent Research:

- Objective: To capture multi-stakeholder perceptions of priorities and trade-offs across environmental, economic, and social sustainability pillars when deciding between a traditional CT and a DCT [2].

- Methodology: An online survey was deployed to 447 international participants from industry, academia, healthcare, and patient groups.

- Data Collection: Participants were asked to rank decision-making criteria for each pillar:

- Environmental: Greenhouse gas emissions, drug treatment disposal, device recycling.

- Economic: R&D costs, time to market, trial probability of success.

- Social: Inclusion of minority groups, patient convenience, access for those living far from sites.

- Analysis: Quantitative data were summarized using frequency and percentages. Qualitative data on trade-offs were processed using content analysis methodology to identify core patterns [2].

- Key Finding: The overall cohort prioritized GHG emissions (22.4%) for environmental impact, trial probability of success (15%) for economic considerations, and patient convenience (23.3%) for social criteria. Overall, the DCT setting was perceived as more sustainable across all pillars [2].

Visualization of Strategic Frameworks and Workflows

The Three Pillars of Sustainable Clinical Trial Design

The following diagram illustrates the core priorities and trade-offs stakeholders consider when evaluating the sustainability of clinical trial designs, as identified in recent research [2].

Sustainability-by-Design in Drug Development

The "sustainability-by-design" approach requires integrating environmental considerations from the earliest stages of development, as a product's fundamental characteristics lock in most of its lifetime environmental impact [5] [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Solutions for Sustainable Research

Implementing sustainability-by-design requires practical tools and methodologies. The following table details key reagents and solutions that support greener drug development.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Sustainable Drug Development

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Application | Sustainability Benefit | Example / Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| "Chemistry in Water" Platform | A synthetic platform that uses water as the primary solvent in chemical reactions. | Reduces or eliminates the consumption of volatile organic solvents, minimizing waste and hazardous material use [5]. | Used in API manufacturing to improve the environmental profile of synthesis steps [5]. |

| Enzymatic Biosolutions | Biological catalysts (enzymes) used in manufacturing processes, such as biodiesel production or API synthesis. | Enable more efficient processing of waste-based feedstocks, reducing energy consumption and operating costs [9]. | Novonesis's Eversa Advance reduces pre-treatment operating costs by up to 45% [9]. |

| High-Density Cell Banking | A bioprocess development tool using highly concentrated cell banks for inoculation. | Allows skipping lengthy seed expansion steps, saving time, resources, and energy in biomanufacturing [5]. | A key element of process intensification in biologics production [5]. |

| In-silico Modeling & AI Platforms | Computational tools for virtual screening, predictive toxicology, and trial simulation. | Reduces the need for physical testing (e.g., compound synthesis, animal models), saving materials and energy and accelerating timelines [10]. | AI can boost hit enrichment rates by >50-fold; in-silico modeling limits physical testing waste [7] [10]. |

| CETSA (Cellular Thermal Shift Assay) | A target engagement validation method used in intact cells and tissues. | Provides mechanistically relevant data early in discovery, helping to de-risk pipelines and reduce late-stage attrition, a major source of R&D waste [10]. | Confirms dose-dependent target engagement in biologically relevant systems, supporting better go/no-go decisions [10]. |

The evidence is clear: the business and ethical cases for sustainability in drug development are not just aligned—they are inseparable. The transition from a "nice-to-have" to a strategic imperative is well underway, driven by investor pressure, regulatory foresight, and the compelling economics of efficiency [5]. Companies that proactively embrace sustainability-by-design are not only mitigating regulatory and reputational risks but are also positioning themselves to achieve lower costs, faster development times, and greater appeal to investors and patients. The frameworks, data, and tools outlined provide a roadmap for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to lead this transformation. By embedding sustainability into the core of R&D, the pharmaceutical industry can fulfill its fiduciary duties to shareholders and its ethical duty to society, ensuring the delivery of high-quality, accessible medicines in a socially and environmentally responsible manner [5].

The pharmaceutical industry faces increasing pressure to balance innovation with environmental responsibility. The traditional linear model of "take-make-waste" poses significant socio-environmental challenges, highlighting an urgent need for sustainable transitions [11]. While individual frameworks such as green chemistry, circular economy, and safe and sustainable-by-design (SSbD) have emerged as valuable approaches, their effectiveness remains suboptimal when implemented in isolation [11]. This guide examines the core principles of each framework and demonstrates how their synergistic integration from the earliest stages of drug development can lead to more sustainable outcomes without compromising product quality or efficacy. For researchers and drug development professionals, this integrated approach represents a fundamental shift toward designing products and processes that are intrinsically safer, more resource-efficient, and environmentally compatible throughout their entire life cycle.

Core Principles and Individual Strengths

Each sustainability framework brings a unique perspective and set of tools to address environmental challenges. Understanding their individual strengths is essential for effective integration.

Green Chemistry: Pollution Prevention at the Molecular Level

Green chemistry focuses on designing chemical products and processes to reduce or eliminate the use and generation of hazardous substances [11]. Its core contribution lies in pollution prevention at the molecular level through its 12 principles, which include waste minimization, atom economy, and designing for degradation [12] [13]. In pharmaceutical contexts, this translates to synthetic route selection that minimizes solvent use, employs renewable feedstocks, and reduces derivatives [12]. The power of green chemistry lies in decisions made at the research bench, where molecular-level choices profoundly impact ultimate sustainability [13].

Circular Economy: Closing Resource Loops

Circular economy principles emphasize designing out waste and maintaining materials in productive use through cycles of reuse, refurbishment, and recycling [14]. This represents a shift from a linear "make-take-waste" model to a closed-loop, regenerative system [11] [14]. For drug development, this means considering how packaging can be redesigned for recyclability, how manufacturing waste can be recirculated, and how single-use components can be reduced or recovered [12] [4]. However, circular systems require careful chemical selection, as hazardous chemicals in products can lead to "circular pollution" where toxins continuously circulate through the system [14].

Safe and Sustainable-by-Design (SSbD): A Holistic Framework

Safe and Sustainable-by-Design (SSbD) is a voluntary, comprehensive framework that prioritizes safety and sustainability throughout a product's entire life cycle [11] [15] [16]. It integrates considerations of human health, environmental impact, and circular functionality from the earliest innovation stages [15]. SSbD provides a structured approach for assessing and selecting chemicals and materials based on multiple criteria including human and environmental hazards, resource efficiency, and end-of-life management [16]. The European Commission promotes SSbD to guide the chemical industry's transition toward climate neutrality and chemical safety in line with the EU Green Deal [15].

Table 1: Core Principles and Focus Areas of Each Framework

| Framework | Primary Focus | Key Principles | Typical Application in Pharma |

|---|---|---|---|

| Green Chemistry | Molecular-level design | Waste prevention, safer chemicals, atom economy, accident prevention [12] [13] | Synthetic route selection, solvent choice, reaction design [12] |

| Circular Economy | Resource flows & systems | Design out waste, maintain material value, regenerate natural systems [14] | Packaging design, waste valorization, single-use reduction [12] [4] |

| Safe & Sustainable-by-Design (SSbD) | Holistic life cycle assessment | Multi-criteria assessment, risk minimization, functionality throughout life cycle [15] [16] | Chemical selection, process design, supplier evaluation [12] [15] |

Comparative Analysis: Quantitative Metrics and Performance

Evaluating the performance of sustainable approaches requires specific metrics that can quantify environmental benefits and facilitate objective comparison.

Key Performance Indicators Across Drug Development Stages

Sustainable design decisions impact various stages of pharmaceutical development and manufacturing. The table below summarizes key metrics and their applications across the drug development life cycle.

Table 2: Sustainability Metrics and Applications in Drug Development

| Metric | Definition | Application Stage | Typical Impact/Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Process Mass Intensity (PMI) [12] [8] | Total mass of materials used per mass of final product | API synthesis, dosage form production | Higher yield and reduced material consumption improve PMI [8] |

| Atom Economy [12] | Molecular weight of product divided by molecular weights of reactants | Route scouting, chemical synthesis | Minimizes waste at molecular level; core green chemistry principle [12] |

| Carbon Footprint [12] | Total GHG emissions across product life cycle | Manufacturing, distribution, supply chain | Includes Scope 3 (indirect) emissions from purchased goods [12] [4] |

| Resource Efficiency [4] | Optimization of raw materials, energy, and water | Bioprocess development, manufacturing | Reduced consumption benefits both environment and cost [4] |

Experimental Data and Comparative Studies

Empirical evidence demonstrates the tangible benefits of implementing sustainable design principles:

- Bioprocess Intensification: Implementing upstream intensification through high-density cell banking and single-use bioreactors with high turndown ratios can reduce standard GMP expansion time by 6-8 days, simultaneously saving time, money, and resources (plastic, water, media) [4].

- Recombinant Protein Production: Increasing expression yield directly improves Process Mass Intensity (PMI), a key sustainability metric. Selecting appropriate expression systems balances yield, resource efficiency, and required product quality [8].

- Solvent Reduction: Acoustic dispensing technology has demonstrated significant reductions in hazardous solvent volumes during screening and development stages, contributing to industry-wide emission reductions [17].

- Plastic Waste Recycling: A specialized program for recycling single-use bioprocess containers has diverted approximately 400,000 pounds of plastic waste from landfills or incineration, converting it into high-quality plastic lumber [4].

Integrated Methodologies: Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Successful integration of sustainability frameworks requires systematic methodologies and collaborative approaches throughout the development process.

Protocol for Early-Stage Sustainability Assessment

Implementing sustainability considerations during early development phases is crucial, as approximately 80% of a drug's final environmental impact is determined at the process design stage [12] [4]. The following protocol ensures built-in sustainability:

- Define Sustainability Design Space: During early development (preclinical to Phase 2), identify product or process parameters that drive environmental impacts, similar to Quality by Design (QbD) approaches [12].

- Apply Streamlined Life Cycle Assessment (LCA): Use qualitative measures and LCAs to compare processes and materials, identifying targeted GHG reduction opportunities such as preferred solvents and toxic substance evaluation [12].

- Conduct Hazard Screening: Employ in silico tools and bioanalytical methods to predict human and ecosystem effects, assessing reagents, reactants, intermediates, and products [15].

- Establish Sustainability Metrics: Incorporate sustainability attributes and metrics into stage-gating processes to ensure improvements are maintained throughout development [12].

- Engage Supply Chain Early: Evaluate supplier sustainability practices, as 42-47% of pharmaceutical emissions come from purchased goods and services [4].

Cross-Functional Collaboration Workflow

Implementing integrated sustainability requires breaking down traditional organizational silos. The following workflow visualizes the essential collaboration points between different expert domains throughout the development process.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Implementing integrated sustainability requires specific tools and approaches. The table below details key resources for researchers pursuing sustainable drug development.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Sustainable Drug Development

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Role in Sustainable Development | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| In Silico Hazard Screening Tools [15] | Computational prediction of human and environmental hazards using QSAR and machine learning | Early-stage compound selection and design |

| Bio-based/Renewable Feedstocks [12] | Replace fossil-based raw materials; enhance biodegradability | Chemical synthesis of APIs and intermediates |

| Verified Safer Chemicals [14] | Pre-assessed chemicals with reduced hazard profiles | Solvent selection, excipient choice, material sourcing |

| High-Yield Expression Systems [8] | Improve Process Mass Intensity (PMI) for biotherapeutics | Recombinant protein production |

| Chemical Hazard Assessment Frameworks [14] | Systematic characterization of chemical hazards | Material selection for devices and packaging |

| Digital Product Passports [18] | Provide transparency on material composition and sustainability | Supply chain engagement and end-of-life management |

Implementation Roadmap and Future Outlook

Adopting an integrated sustainability approach requires strategic planning and organizational commitment. Implementation should begin in early R&D and CMC phases before regulatory constraints limit flexibility [12] [4]. Companies should prioritize cross-organizational adaptation of digital tools and databases, capability upgrades in drug development functions, and sustainability acumen across the entire organization [12].

The future of sustainable drug development will be shaped by several key trends:

- Regulatory Drivers: The EU's Chemicals Strategy for Sustainability and emerging regulations will increasingly influence material selection and process design [12] [15].

- Economic Incentives: Hospital procurement systems are incorporating sustainability performance into decision criteria, creating market advantages for sustainable products [4].

- Collaborative Innovation: Industry-academia partnerships, such as the Mistra SafeChem programme, are developing novel synthesis routes and assessment methods [15].

- Circular Integration: Closing material loops through recycling collaborations will become standard practice, as demonstrated by programs that convert single-use bioprocess containers into new valuable materials [4].

The most successful organizations will be those that treat sustainability not as a compliance requirement but as an integral component of innovation and quality, embedding it into every stage of drug development from discovery through commercialization.

Implementing SbD: Practical Frameworks and Tools for Drug Developers

In the pharmaceutical industry, sustainability-by-design is an emerging paradigm that integrates environmental considerations from the very beginning of the bioprocess development cycle. Given that up to 80% of a drug’s final environmental impact is determined during the early stages of process design, Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) provides an indispensable framework for quantifying this impact and identifying strategic improvement opportunities [4]. An LCA is a systematic analysis of the environmental impact of a product caused or necessitated by its existence over its entire life cycle [19]. For drug development professionals, this means evaluating from the extraction of raw materials ("cradle") to the disposal of the product after use ("grave") [20].

This cradle-to-grave approach is particularly crucial for bioprocess development, where decisions made in R&D and chemistry, manufacturing, and controls (CMC) phases have long-lasting environmental and economic repercussions. A holistic LCA enables researchers and scientists to move beyond simple carbon accounting to a multi-criteria assessment that includes water consumption, resource depletion, and ecotoxicity, thereby supporting a comprehensive hotspot analysis that is foundational to sustainability-by-design [20].

The LCA Framework: ISO Standards and Methodologies

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) provides standardized methodologies for LCA in ISO 14040 and 14044, ensuring reliability and transparency [21]. These standards describe LCA as an iterative process consisting of four distinct but interdependent phases, creating a robust framework for objective environmental assessment [19] [21].

The Four Phases of an LCA

The following workflow illustrates the interconnected, iterative process of conducting a Life Cycle Assessment as defined by ISO standards:

Goal and Scope Definition: This foundational phase outlines the LCA's purpose, the product system to be studied, and its boundaries. It defines the functional unit that quantifies the performance of the product system, ensuring comparisons are made on a common basis. For drug development, this might involve setting the system boundaries to a cradle-to-gate approach (from raw material to factory gate) for internal decision-making, or a full cradle-to-grave analysis for comprehensive environmental reporting [19] [21].

Life Cycle Inventory (LCI): In this data-collection phase, all material and energy inputs (e.g., raw materials, energy, water) and environmental outputs (e.g., emissions to air, water, and soil) associated with the product system are quantified. Creating a complete inventory requires detailed data on bioprocess inputs, including cell culture media, chemicals, water, energy consumption, and waste generation [21].

Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA): The inventory data is then translated into potential environmental impacts. This phase classifies emissions and resource uses into designated impact categories and models their potential contributions to environmental problems such as global warming potential, water consumption, or freshwater ecotoxicity [21] [20].

Interpretation: This final phase involves reviewing the results from the LCI and LCIA to draw conclusions, explain limitations, and provide recommendations. It is a critical checkpoint to ensure that the conclusions are well-substantiated and directly address the goal and scope defined at the outset [21].

LCA Approaches: From Cradle-to-Grave to Cradle-to-Cradle

Depending on the defined goal and scope, different life cycle models can be applied. The most relevant approaches for pharmaceutical development are compared in the table below.

Table 1: Comparison of Life Cycle Assessment Models

| Model | Scope | Application in Drug Development |

|---|---|---|

| Cradle-to-Grave [19] | Includes all stages from raw material extraction ("cradle") to disposal ("grave"). | Comprehensive environmental footprinting for regulatory submissions or Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs). |

| Cradle-to-Gate [19] [21] | Assesses a product from resource extraction to the factory gate, excluding use and disposal. | Most common scope for internal decision-making and supplier evaluations, as it focuses on processes under direct manufacturer control. |

| Cradle-to-Cradle [19] [21] | A closed-loop model where materials are fully reusable in the next product life cycle. | Inspirational for designing processes that minimize waste; aligns with circular economy principles but challenging to implement fully in GMP environments. |

| Gate-to-Gate [19] [21] | Focuses on a single value-added process within the larger life cycle. | Useful for hotspot analysis of specific unit operations (e.g., a fermentation process or a purification step) to target improvement efforts. |

For a comprehensive hotspot analysis aligned with sustainability-by-design, the cradle-to-grave approach is the most holistic, as it captures impacts across the entire value chain. However, cradle-to-gate assessments are frequently used in business-to-business communication and for Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs), which are standardized certifications of a life cycle assessment [19].

Essential LCA Tools and Software for Researchers

Specialized LCA software is critical for managing the complexity of data collection, modeling, and impact assessment. These tools provide integrated databases and standardized impact assessment methods, enabling consistent and scientifically robust evaluations [22]. The landscape of available software is diverse, catering to different levels of expertise and specific industry needs.

Table 2: Comparison of Leading LCA Software Tools

| Software Tool | Key Features | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|

| SimaPro [21] [22] | One of the leading expert LCA software solutions; allows deep customization of models and parameters. | LCA experts, sustainability consultants, and advanced researchers in large institutions. |

| Sphera (GaBi) [22] | Combines LCA modeling with reliable, consistent environmental data and sector-specific databases. | Enterprises and industries requiring robust, sector-specific data for high-stakes decision-making. |

| openLCA [22] | The only free, open-source LCA software that can be used for professional assessments. | Academic researchers, students, and organizations with limited budgets seeking maximum flexibility. |

| Ecochain Mobius [22] | Offers user-friendly interfaces that enable users without an LCA background to start environmental assessments. | Cross-functional teams, SMEs, and companies beginning their sustainability journey. |

| One Click LCA [22] | Automated LCA & EPD software tailored for the construction industry. | Specialized applications in building and infrastructure design. |

The choice of software often depends on the organization's expertise, budget, and specific application needs. For drug development, tools that can model complex chemical and biological processes and integrate with existing process engineering software are particularly valuable.

Conducting a scientifically rigorous LCA requires both conceptual tools and specific, high-quality data. The following table details essential components for building a reliable life cycle inventory in biopharmaceutical research.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for LCA in Bioprocess Development

| Tool / Solution | Function in LCA | Application Example in Bioprocess |

|---|---|---|

| High-Titer Cell Lines [4] | Increases volumetric productivity, reducing the resource footprint per unit of product. | Using engineered cell lines to achieve higher product yields in bioreactors, thereby lowering material and energy use per gram of monoclonal antibody. |

| Chemically Defined Media [4] | Reduces batch variability and contamination risks; enables sourcing from sustainability-minded suppliers. | Replacing serum-containing media with defined formulations to improve process control and allow for environmental preference in supplier selection. |

| Process Mass Intensity (PMI) Data [4] | Serves as a key inventory metric, quantifying the total mass of inputs per unit mass of product. | Calculating the PMI for a specific drug substance to identify high-mass, high-impact inputs for targeted reduction efforts. |

| Single-Use Bioreactors (SUBs) [4] | Can reduce energy and water consumption by eliminating cleaning and sterilization needs; requires end-of-life management. | Implementing SUBs in clinical manufacturing to reduce water-for-injection consumption and clean-steam generation. |

| High-Capacity Chromatography Resins [4] | Improves purification efficiency, reducing buffer consumption and process time. | Utilizing modern affinity resins to decrease buffer volume requirements in downstream purification, directly reducing water use and waste generation. |

| Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) Databases [22] | Provide secondary data for common materials, energy, and processes when primary data is unavailable. | Using database values for the environmental impact of common chemicals (e.g., sodium hydroxide, acids) or energy grids to fill data gaps in the inventory. |

Experimental Protocols for LCA in Bioprocess Development

Protocol for Unit Operation Hotspot Analysis

This protocol outlines a standardized methodology for assessing the environmental impact of individual unit operations, a fundamental exercise in sustainability-by-design.

Goal and Scope Definition:

- Objective: To identify and quantify the environmental hotspots within a specific bioprocess unit operation (e.g., fermentation, centrifugation, chromatography).

- Functional Unit: Define a relevant unit, such as "per kg of drug substance produced" or "per batch of process volume treated."

- System Boundary: Set to a gate-to-gate scope, focusing solely on the inputs and outputs of the target unit operation.

Data Collection (LCI):

- Primary Data: Collect measured data for all material inputs (e.g., mass of media, chemicals, resins), energy inputs (e.g., kWh for agitation, cooling, pumping), and water consumption directly from the process.

- Outputs: Quantify product yield, waste streams (e.g., spent media, used chromatography resins), and air emissions.

- Data Quality: Document sources, age, and representativeness of all data points. Preference should be given to primary, plant-specific data.

Impact Assessment (LCIA):

- Method Selection: Choose a relevant LCIA method (e.g., EF Method 2.0, CML-IA) [20].

- Impact Categories: Select categories pertinent to the process, such as Global Warming Potential (kg CO₂ eq.), Fossil Fuel Use (MJ deprived), and Water Consumption (m³ world-eq.) [20].

- Calculation: Use LCA software to translate the inventory data into impact category results.

Interpretation and Hotspot Identification:

- Contribution Analysis: Analyze the results to determine which inputs (e.g., a specific chemical, energy for cooling) contribute most significantly to each impact category.

- Sensitivity Analysis: Test how changes in key parameters (e.g., a 10% reduction in buffer usage) affect the overall results to identify leverage points for improvement.

Protocol for Comparative Assessment of Process Alternatives

This protocol provides a framework for using LCA to compare two or more process alternatives, such as single-use versus stainless-steel equipment, or traditional versus intensified processing.

Goal and Scope Definition:

- Objective: To determine the environmentally preferable option among defined process alternatives.

- Functional Unit: Must be identical and comparable for all alternatives (e.g., "1 liter of harvested cell culture fluid").

- System Boundary: Must be equivalent for all alternatives; a cradle-to-gate scope is typically used.

Inventory Modeling:

- Model Each Alternative: Create a separate life cycle model for each process alternative, using the same LCA software and background database.

- Allocation: If the process produces multiple products, apply consistent allocation rules (e.g., mass, economic) across all models.

Impact Assessment and Comparison:

- Consistent LCIA: Apply the exact same impact assessment method and categories to all models.

- Normalization: Consider normalizing the results to a common reference to better understand the relative magnitude of differences.

Interpretation:

- Discernibility Analysis: Use statistical or other methods to determine if the observed differences between alternatives are significant.

- Conclusion: State the preferred alternative based on the LCA results, clearly outlining the trade-offs across different impact categories.

LCA Impact Categories and Data Presentation

A robust LCA for drug development must look beyond carbon emissions to a multi-criteria perspective. The following table summarizes key environmental indicators and typical data outputs that researchers can use to benchmark their processes.

Table 4: Key Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA) Categories and Indicators [20]

| Impact Category | Indicator Unit | What It Measures | Relevance to Bioprocess Development |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Warming Potential | kg CO₂ equivalent | Total greenhouse gases emitted, contributing to climate change. | Directly linked to energy source and consumption; a primary metric for corporate sustainability goals. |

| Fossil Fuel Use | MJ deprived | Consumption of non-renewable fossil fuels. | Highlights dependency on finite resources; can be reduced via renewable energy and process efficiency. |

| Water Consumption | m³ world equivalent | Water use, weighted by local water scarcity. | Critical for water-intensive bioprocesses; assesses operational risks in water-stressed regions. |

| Mineral Resource Use | kg deprived | Depletion of mineral resources. | Relevant for sourcing of metals and rare earth elements used in equipment and catalysts. |

| Freshwater Eutrophication | kg PO₄ equivalent | Emissions causing excessive algal growth in freshwater. | Important for assessing the impact of nutrient-rich waste streams from fermentation. |

| Freshwater Ecotoxicity | CTUe (Comparative Toxic Unit) | The ecotoxicity impact of chemical releases. | Evaluates potential harm from the release of process chemicals and solvents into aquatic systems. |

Integrating a cradle-to-grave Life Cycle Assessment into drug development is no longer an optional exercise but a core component of strategic sustainability-by-design. By providing a rigorous, data-driven methodology for hotspot identification, LCA empowers researchers, scientists, and process engineers to make informed decisions that significantly reduce environmental impacts at the stages where they are most effectively influenced. As regulatory pressures mount and investor and customer expectations evolve, the ability to demonstrate validated, improved environmental performance through tools like LCA will become a key differentiator in the competitive biopharmaceutical landscape.

The synthesis of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) represents a significant environmental footprint within the pharmaceutical industry, driving an urgent need for more sustainable manufacturing practices. The concept of sustainability-by-design advocates for integrating environmental considerations from the earliest stages of drug development, rather than as an afterthought. This approach is embodied in the 12 Principles of Green Chemistry, a framework established to revolutionize traditional chemical processes by reducing or eliminating the use and generation of hazardous substances [23] [24]. For researchers and scientists in drug development, applying these principles—particularly in solvent selection, atom economy, and waste prevention—is crucial for minimizing ecological impact while maintaining the high efficacy and quality standards demanded by modern medicine. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these core strategies, supported by experimental data and protocols, to equip professionals with practical tools for implementing green chemistry in API development.

Solvent Selection: A Comparative Guide to Safer Alternatives

Solvents are one of the largest contributors to waste in pharmaceutical synthesis, often constituting up to 80% of the total mass intensity in an API process [25]. Traditional solvents like dichloromethane, toluene, and N,N-dimethylformamide pose significant environmental, health, and safety concerns due to their toxicity, volatility, and difficult disposal. The green chemistry principle of Safer Solvents and Auxiliaries emphasizes the substitution of these hazardous solvents with environmentally preferable alternatives [23] [26].

The following table compares the environmental and technical performance of conventional solvents against emerging green alternatives.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Conventional vs. Green Solvents in API Synthesis

| Solvent Category | Example Solvents | Environmental & Health Impact | Technical Performance | Scalability & Cost Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional (Petrochemical-based) | Dichloromethane, Toluene, Tetrahydrofuran | High volatility, toxicity, carcinogenicity, significant waste disposal challenges [26] | Excellent solvation power for a wide range of organic compounds | Well-established supply chains, but rising disposal and regulatory costs |

| Bio-based Solvents | Ethyl Lactate, Limonene, Glycerol | Low toxicity, biodegradable, derived from renewable feedstocks [27] | Good solvation for polar and non-polar compounds; properties can be tuned | Growing availability, cost-competitive with some conventional solvents |

| Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) | Choline Chloride/Urea mixtures | Very low volatility, low toxicity, biodegradable [27] | Highly tunable solubility for specific applications, high viscosity can be a challenge | Emerging technology, scalability for large-scale manufacturing under development |

| Water | N/A | Non-toxic, non-flammable, safe [26] | Poor solubility for many organic compounds; requires design of water-compatible reactions | Highly scalable and cost-effective when applicable |

| Supercritical Fluids | CO₂ (scCO₂) | Non-toxic, non-flammable, easily removed post-reaction [27] | Excellent diffusivity and tunable density/solvation; requires high-pressure equipment | High capital cost for pressure vessels, operational cost for compression |

Experimental Protocol: Solvent Greenness Assessment

Aim: To evaluate and rank the greenness of different solvents for a specific API reaction step.

Methodology:

- Identify Candidates: Compile a list of solvent candidates capable of dissolving the reactants and products of the target reaction.

- Consult Selection Guides: Refer to established Solvent Selection Guides from companies like Pfizer, GSK, and Sanofi, which rank solvents based on multiple health, safety, and environmental criteria [28].

- Measure Key Metrics: For the chosen reaction, run small-scale parallel experiments with different solvents and measure:

- Reaction Yield: Isolate and weigh the product to calculate percentage yield.

- Purity: Analyze product purity via HPLC or GC-MS.

- Solvent Recovery Efficiency: Distill and recover the solvent post-reaction; calculate the percentage that can be reused.

- Calculate Process Mass Intensity (PMI): For each solvent, determine the PMI, which is the total mass of input materials (including solvent, water, reagents) per mass of API produced. Lower PMI indicates a more efficient and less wasteful process [28].

Supporting Data: A study on the synthesis of Tafenoquine succinate demonstrated that careful solvent selection and the development of a two-step one-pot synthesis significantly reduced waste compared to previous routes [24].

Atom Economy: Maximizing Resource Efficiency

Atom economy, the second principle of green chemistry, is a measure of synthesis efficiency. It evaluates what proportion of the mass of all reactants ends up in the final desired product, thereby minimizing by-product formation at the molecular level [23]. Traditionally, chemists focused on percent yield, but a high yield can still involve significant waste if heavy, unused by-products are generated.

The formula for calculating atom economy is: % Atom Economy = (Molecular Weight of Desired Product / Sum of Molecular Weights of All Reactants) x 100 [23]

The following table compares common reaction types based on their inherent atom economy.

Table 2: Atom Economy Comparison of Common Reaction Types in API Synthesis

| Reaction Type | General Equation | Inherent Atom Economy | Green Chemistry Alternative | Alternative's Atom Economy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Substitution | A-B + C-D → A-C + B-D | Moderate to Low (generates a stoichiometric by-product, B-D) | Rearrangement | High (100%, all atoms from reactant are in the product) |

| Addition | A-B + C=C → A-C-C-B | High (100%, all atoms are incorporated into the product) | N/A (Already optimal) | High |

| Elimination | A-C-C-B → C=C + A-B | Low (generates a stoichiometric by-product, A-B) | Addition | High |

| Wittig Reaction | RRC=O + Ph3P=CR2 → RRC=CR2 + Ph3P=O | Low (generates triphenylphosphine oxide waste) | Catalytic Olefination | High (uses a catalytic cycle, minimal by-products) |

Experimental Protocol: Atom Economy Calculation and Optimization

Aim: To calculate the atom economy of a proposed synthetic route and identify opportunities for improvement.

Methodology:

- Define the Stoichiometric Equation: Write the balanced equation for the reaction, including all reactants and stoichiometric by-products.

- Calculate Molecular Weights: Determine the molecular weights of the desired product and all reactants.

- Apply the Formula: Use the atom economy formula to calculate the percentage.

- Retrosynthetic Analysis: Use databases, such as the one created by a consortium of major pharma companies containing nearly 2000 scaled-up reactions, to identify alternative disconnections with higher inherent atom economy [28].

- Employ Efficient Strategies: Implement the following high-atom-economy strategies:

- Multicomponent Reactions (MCRs): Combine three or more reactants in a single step to build complex molecules, minimizing intermediate purification and maximizing atom utilization [26].

- Catalysis: Use catalytic cycles (e.g., with nickel or enzymes) instead of stoichiometric reagents to drive reactions, substantially reducing waste [28] [26].

Supporting Data: The atom economy of a classic substitution reaction converting butanol to bromobutane using NaBr and H2SO4 is only 50%, meaning half the mass of the reactants is wasted as sodium hydrogen sulfate and water, even with a 100% yield [23].

Waste Prevention: Metrics and Process Intensification

The foundational principle of green chemistry is Prevention: "It is better to prevent waste than to treat or clean up waste after it has been created" [23]. In API manufacturing, this extends beyond atom economy to encompass all materials used, including solvents, water, and process aids. The key metric for benchmarking waste generation is the Process Mass Intensity (PMI).

PMI = Total Mass of Materials Used in the Process (kg) / Mass of Final API (kg) [23]

A lower PMI signifies a more efficient and less wasteful process. Historically, PMI for APIs could exceed 100 kg/kg, but applications of green chemistry have achieved dramatic reductions, sometimes as much as ten-fold [23].

Table 3: Waste Prevention Strategies and Their Impact on Process Mass Intensity (PMI)

| Strategy | Technology/Method | Mechanism of Waste Reduction | Reported PMI Reduction / Outcome | Implementation Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Process Intensification | Continuous Manufacturing & Flow Chemistry | Higher surface-to-volume ratio improves heat/mass transfer, enables safer use of harsh conditions, reduces equipment size [28] [26] | Significant reduction in solvent use and energy consumption vs. batch [28] | Requires re-design of reactor systems and process control strategies |

| Solvent Recovery | Distillation, Membrane Separation | Recycles and reuses solvents within the process, reducing fresh solvent input and waste output | Can recover >90% of solvent for reuse, directly lowering PMI [29] | Requires energy and additional unit operations |

| Catalysis | Biocatalysis (Enzymes) | Enzymes operate under mild conditions with high selectivity, avoiding protective groups and purification waste [28] [26] | High selectivity reduces by-products; e.g., in Artemisinin synthesis [26] | Enzyme production cost and stability under process conditions |

| Alternative Energy Inputs | Photochemistry, Mechanochemistry | Photochemistry uses light to drive reactions; mechanochemistry avoids solvents entirely by using mechanical force [28] [26] | Mechanochemistry can achieve PMI close to 1 for some reactions by eliminating solvent | Scaling from lab to production can be non-trivial |

Experimental Protocol: PMI Calculation and Waste Audit

Aim: To quantify the waste output of an API synthesis step by calculating its Process Mass Intensity.

Methodology:

- Material Inventory: For a single batch or a continuous process run, record the mass of every material input: starting materials, reagents, solvents, and water.

- Product Output: Accurately weigh the mass of the final, purified API produced.

- Calculate PMI: Divide the total input mass by the output mass.

- Breakdown Contribution: Analyze the data to determine which inputs (e.g., specific solvents) are the largest contributors to the PMI. This identifies key areas for improvement.

- Explore Intensification: Model or test the impact of switching from batch to continuous processing, which often leads to smaller reactor volumes, higher selectivity, and reduced solvent use, thereby lowering PMI [28].

Supporting Data: Pfizer's application of green chemistry principles in redesigning the Sertraline process resulted in a 19% reduction in waste and a 56% improvement in productivity compared to past production standards [30].

Integrated Workflow and Research Toolkit

Implementing green chemistry requires a systematic approach that integrates the principles of solvent selection, atom economy, and waste prevention from the earliest stages of route scouting. The following diagram visualizes this interconnected, sustainability-by-design workflow for API process development.

Diagram 1: Sustainability-by-Design Workflow for API Development. This workflow illustrates the iterative process of designing a sustainable API synthesis, emphasizing the early integration of atom economy, guided solvent selection, and process intensification to minimize environmental impact.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

This table details key reagents and technologies that form the core toolbox for developing greener API syntheses.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Green API Synthesis

| Tool/Reagent | Function in Green Synthesis | Example & Green Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Biocatalysts (Enzymes) | Highly selective catalysts for specific transformations (e.g., ketone reduction, chiral amine synthesis). | Immobilized Lipases; Benefit: Operate under mild conditions (aqueous, ambient T&P), high selectivity avoids protecting groups, biodegradable [28] [26]. |

| Non-Precious Metal Catalysts | Catalyze key bond-forming reactions (e.g., cross-coupling) as alternatives to expensive, scarce precious metals. | Nickel Catalysts; Benefit: More abundant and cheaper than palladium/platinum, reduces resource depletion and cost [30]. |

| Green Solvent Kits | A curated set of alternative solvents for screening and optimization. | Bio-based Solvents (Ethyl Lactate, Cyrene), Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES); Benefit: Lower toxicity, biodegradability, and derived from renewable resources [27] [26]. |

| Flow Reactor Systems | Enables continuous processing for improved safety, mixing, heat transfer, and reaction control. | Microreactors; Benefit: Significantly reduces solvent use and PMI, enables safer handling of exothermic reactions and hazardous intermediates [28] [26]. |

| PMI Prediction Calculator | Software tools that predict Process Mass Intensity early in route design. | Historical Data-Based Calculators; Benefit: Allows virtual screening of synthetic routes for environmental efficiency before any lab work, guiding chemists toward greener choices [28]. |

The transition to sustainable API manufacturing is both an environmental imperative and an opportunity for scientific innovation. By systematically applying the principles of green chemistry—through the informed selection of safer solvents, the strategic design of syntheses with high atom economy, and the relentless prevention of waste via process intensification—drug development professionals can dramatically reduce the ecological footprint of their processes. As demonstrated by industry case studies and emerging research, this "sustainability-by-design" approach is not merely a compliance exercise but a pathway to more efficient, economical, and responsible pharmaceutical production. The tools, metrics, and comparative data provided in this guide offer a foundation for researchers to embed these principles into their daily R&D efforts, paving the way for a greener future in medicine.

Process Intensification (PI) represents a fundamental paradigm shift in bioprocessing and pharmaceutical manufacturing, focusing on radically improving process efficiency, sustainability, and safety through innovative design and technologies [31]. In the context of biopharmaceuticals, PI encompasses strategies to significantly increase output relative to cell concentration, time, reactor volume, or cost, resulting in substantial improvements in productivity, environmental, and economic metrics [32]. This approach stands in contrast to traditional batch processing, which has dominated pharmaceutical manufacturing due to its flexibility and historical precedence [33].

Continuous Manufacturing, a key manifestation of process intensification, involves non-stop production where raw materials are continuously fed into the system and finished products emerge steadily at the output [33]. This method minimizes downtime, maximizes product output, and provides consistent product quality through stable, steady-state operations [33] [34]. The biopharmaceutical industry has increasingly adopted continuous processing approaches, particularly for labile products prone to degradation during extended processing, though implementation varies significantly across different production scales and product types [34].

The drive toward process intensification and continuous manufacturing aligns with broader sustainability initiatives within the pharmaceutical sector. By positioning manufacturing processes within the context of the United Nations' 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, companies can simultaneously address economic, environmental, and social dimensions of pharmaceutical production [35]. This integrated approach demonstrates how technical innovations in bioprocessing contribute directly to global sustainability goals, including responsible consumption and production, climate action, and affordable clean energy [35].

Comparative Analysis: Batch vs. Continuous Manufacturing

Performance Metrics and Economic Considerations

Table 1: Economic and Operational Comparison Between Batch and Continuous Manufacturing

| Performance Metric | Batch Manufacturing | Continuous Manufacturing | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Volumetric Productivity | 0.1–0.7 g/L-day (mAb) | >8 g/L-day (intensified processes) | [34] [36] |

| Production Duration | 7–14 days (typical fed-batch) | 25+ days (demonstrated for rAAV) | [34] [36] |

| Facility Footprint | Larger equipment requirements | Miniaturized plant size | [32] |

| Capital Investment (CAPEX) | Lower initial investment | Significant upfront investment | [33] [32] |

| Operational Costs (OPEX) | Higher per unit costs | Reduced operating expenses | [32] |

| Implementation in Pharmaceuticals | ~99% of approved drugs | ~0.03% of approved drugs (13 drugs as of 2022) | [33] |

The comparative analysis between batch and continuous manufacturing reveals a complex landscape where each approach offers distinct advantages depending on production requirements. Batch processing dominates pharmaceutical manufacturing, accounting for approximately 99% of approved drugs, while continuous methods represent only about 0.03% of the market [33]. This distribution reflects both historical precedent and practical considerations regarding production scale and flexibility.

Batch manufacturing provides significant advantages in flexibility, allowing manufacturers to respond dynamically to market fluctuations and produce diverse products without extensive reconfiguration [33]. This approach particularly benefits specialty chemicals and pharmaceuticals where production volumes are relatively low (often less than 1,000-10,000 metric tons annually) and requirements for customization are high [33]. The lower initial capital investment for batch systems also makes them economically viable for smaller production runs and diverse product portfolios.

Continuous manufacturing excels in high-volume production scenarios where steady-state operations can be maintained for extended periods [33]. The economic viability of continuous processes depends heavily on achieving high capacity utilization, with suitable investment returns typically requiring operation at 80% of capacity or higher [33]. This approach demonstrates particular strength in volumetric productivity, with intensified continuous processes achieving more than 10-fold productivity gains compared to traditional fed-batch systems [36] [34].

Environmental and Sustainability Metrics

Table 2: Environmental Impact Comparison Between Manufacturing Approaches

| Environmental Metric | Batch Manufacturing | Continuous Manufacturing | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy Consumption | Higher due to repeated start-up/shutdown | Reduced through steady-state operations | Significant reduction [33] [32] |

| Process Mass Intensity (PMI) | Higher material usage per product unit | Reduced material requirements | ~75% reduction demonstrated [37] |

| Reagent Consumption | Higher volumes typically required | Reduced usage through intensification | Notable decrease [32] |

| Waste Generation | Typically higher | Minimized through efficient processing | Substantial reduction [32] |

| Carbon Footprint | Larger footprint | Reduced emissions | Improved sustainability [32] |

The environmental advantages of process intensification and continuous manufacturing extend across multiple dimensions, contributing significantly to sustainability goals in pharmaceutical production. Continuous processes demonstrate superior energy efficiency compared to batch systems, primarily due to consistent operating conditions that eliminate repeated heating and cooling cycles [33]. This energy optimization directly supports United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy) by reducing overall energy demand and promoting more efficient resource utilization [35].

Process Mass Intensity (PMI) improvements represent another significant environmental benefit, with innovative approaches achieving reductions of approximately 75% in some pharmaceutical applications [37]. These efficiency gains stem from streamlined synthesis pathways, reduced chromatography requirements, and optimized material utilization. For instance, green chemistry innovations have demonstrated the transformation of complex 20-step syntheses into streamlined processes with only three handling steps, dramatically reducing resource consumption while maintaining product quality [37].

The waste minimization potential of continuous processes further enhances their environmental profile, addressing targets outlined in UN Sustainable Development Goal 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production) [35]. Through improved process control, reduced reagent requirements, and more efficient conversion pathways, intensified systems generate less waste per unit of product while maintaining high quality standards. These environmental benefits position process intensification as a cornerstone strategy for achieving sustainability targets in pharmaceutical manufacturing.

Experimental Protocols and Implementation Strategies

Upstream Process Intensification Methodologies

High-Density Perfusion Cell Culture Protocol:

- System Setup: Implement perfusion technology using alternating tangential flow (ATF) or tangential flow filtration (TFF) systems. The XCell ATF system has demonstrated successful scale-up from 1 L to 5000 L production scales [32].

- Cell Culture Parameters: Maintain high cell densities (typically 2-5 times higher than fed-batch) through continuous media exchange. Optimize perfusion rates based on nutrient consumption and metabolic waste accumulation.

- Process Analytical Technology (PAT) Integration: Incorporate online monitoring for critical process parameters including pH, dissolved oxygen, and metabolite concentrations. Implement glucose and lactate analyzers for real-time nutrient control [36] [34].

- Duration and Productivity: Operate cultures for extended durations (weeks to months) with volumetric productivity targets exceeding 1 g/L-day for monoclonal antibodies, compared to 0.1-0.7 g/L-day in traditional fed-batch processes [34].

N-1 Seed Train Intensification Protocol: