Strategic Green Analytical Method Development: Integrating GAC, WAC, and Modern Metrics for Sustainable Pharmaceutical Analysis

This article provides a comprehensive roadmap for researchers and drug development professionals to implement green analytical chemistry (GAC) principles in pharmaceutical analysis.

Strategic Green Analytical Method Development: Integrating GAC, WAC, and Modern Metrics for Sustainable Pharmaceutical Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive roadmap for researchers and drug development professionals to implement green analytical chemistry (GAC) principles in pharmaceutical analysis. It explores the foundational shift from traditional methods to sustainable practices, detailing the application of green solvents, miniaturized techniques, and eco-friendly sample preparation. The content covers systematic optimization using Analytical Quality by Design (AQbD) and Design of Experiments (DoE), and introduces the White Analytical Chemistry (WAC) framework for balancing ecological, analytical, and practical requirements. A thorough review of modern greenness assessment tools (AGREE, GAPI, AMGS) guides the validation and comparative selection of methods, empowering scientists to develop robust, compliant, and environmentally responsible analytical procedures.

The Principles and Evolution of Green Analytical Chemistry: From GAC to White Analytical Chemistry

Core Principles of Green Analytical Chemistry

Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) is a transformative approach that integrates sustainability principles into analytical practices, aiming to minimize the environmental impact of chemical analysis while maintaining high analytical standards [1]. Its foundation is built upon a framework of principles designed to guide the development of safer, more efficient, and environmentally benign methodologies.

The 12 principles of GAC provide a comprehensive roadmap for implementing greener practices in analytical procedures [2]. These principles cover various aspects, including the minimization of reagent and energy consumption, the reduction of waste generation, the promotion of operator safety, and the development of direct analytical techniques that eliminate the need for extensive sample preparation [3] [2]. A key objective is to shift away from the traditional "take-make-dispose" linear model towards a more circular and sustainable framework for analytical chemistry [4].

Table 1: The 12 Principles of Green Analytical Chemistry and Their Implications

| Principle | Core Concept | Practical Application in Analytical Chemistry |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Direct Analysis | Eliminate sample preparation steps | Use of in-situ measurements, direct probe techniques, and portable instruments [5]. |

| 2. Energy Reduction | Minimize energy consumption | Use of room-temperature procedures, automated shutdown, and energy-efficient instruments [5] [1]. |

| 3. Green Reagents | Use safe, renewable reagents | Replacement of toxic solvents with bio-based alternatives, ionic liquids, or deep eutectic solvents [5] [1]. |

| 4. Waste Minimization | Prevent waste generation | Integration of microextraction techniques and miniaturized analytical systems [6] [5]. |

| 5. Miniaturization | Down-scale methods | Use of microfluidic devices, lab-on-a-chip technology, and microextraction by packed sorbent (MEPS) [5]. |

| 6. Automation | Streamline processes | Implementation of automated sample preparation and analysis to enhance throughput and safety [4]. |

| 7. Derivatization Avoidance | Eliminate unnecessary steps | Development of direct detection methods (e.g., mass spectrometry) that do not require chemical derivatization [1]. |

| 8. Multi-analyte Assays | Maximize sample information | Design of methods that simultaneously determine multiple analytes to reduce number of overall analyses [2]. |

| 9. Energy-Efficient Detection | Choose low-power instruments | Preference for sensors and detectors with lower power requirements [1]. |

| 10. Natural Reagents | Source from renewables | Use of reagents derived from biological sources to replace synthetic, hazardous chemicals [3]. |

| 11. Waste Management | Recycle and treat waste | Implementation of solvent recycling systems and proper treatment of analytical waste [5]. |

| 12. Operator Safety | Prioritize risk reduction | Design of methods that minimize exposure to hazardous chemicals through containment and automation [4] [3]. |

The SIGNIFICANCE Mnemonic in Practice

To aid in the memorization and application of its core tenets, Green Analytical Chemistry employs the mnemonic device SIGNIFICANCE [3] [2]. Mnemonic devices are memory aids that form associations between simple phrases or concepts and more complex information, significantly enhancing recall [6] [7]. The SIGNIFICANCE mnemonic encapsulates essential green analytical practices, with each letter representing a key action.

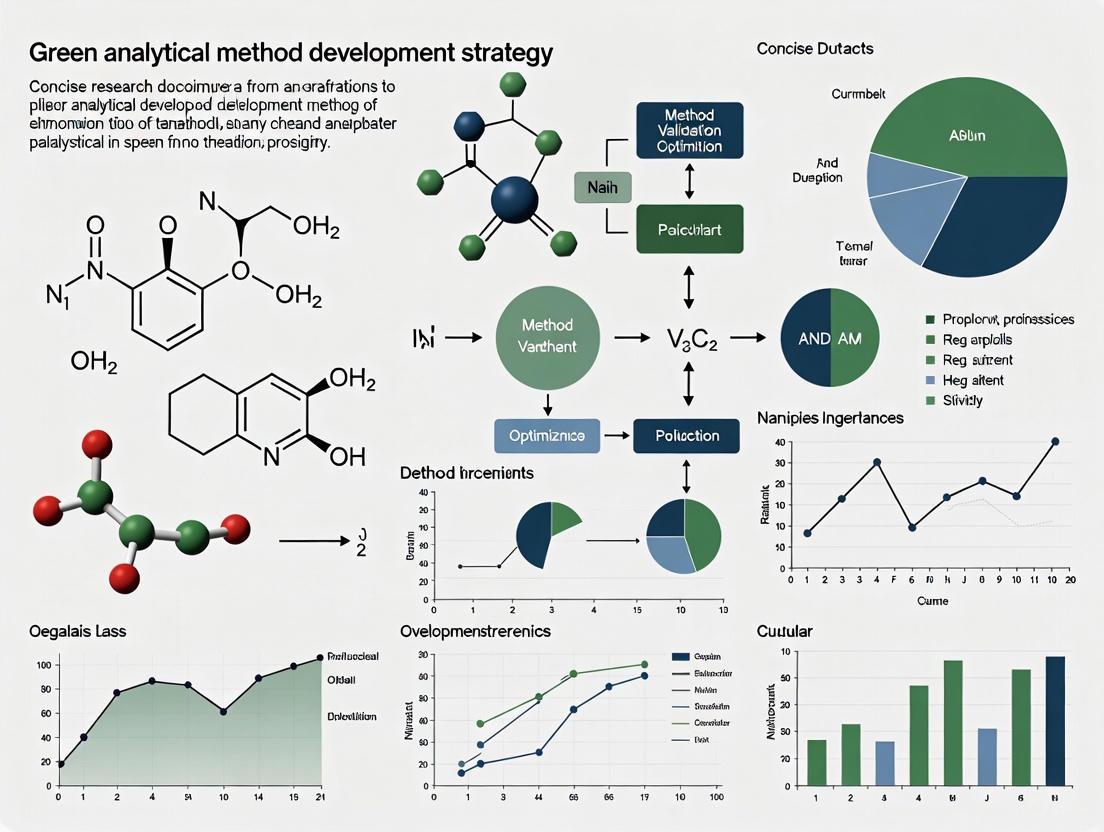

Green Analytical Method Development Strategy

Developing a green analytical method requires a strategic shift from conventional approaches, focusing on systematic assessment and the integration of sustainable technologies from the initial design phase. This strategy aligns with the broader thesis that green method development is not merely an add-on but a fundamental redesign of analytical processes.

Greenness Assessment Tools and Metrics

A critical step in green method development is the quantitative evaluation of a method's environmental impact using validated assessment tools. Multiple metrics have been developed, each with specific criteria and scoring systems, to provide a transparent and comparable measure of greenness [8] [2].

Table 2: Key Greenness Assessment Metrics for Analytical Methods

| Metric Name | Type of Output | Scoring Range / Criteria | Key Assessed Parameters | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEMI (National Environmental Methods Index) [2] | Pictogram (4 quadrants) | Pass/Fail (Green/White) | PBT chemicals, hazardous waste, corrosivity, waste amount ≤50g | Quick, preliminary screening |

| Analytic Eco-Scale [2] | Numerical Score | Ideal analysis = 100 points; >75 = acceptable greenness; <50 = inadequate greenness | Reagent toxicity, amount, energy consumption, waste | Penalty-based detailed assessment |

| GAPI (Green Analytical Procedure Index) [2] | Pictogram (5 pentagrams) | Qualitative (Green/Yellow/Red) | Sample collection, preservation, preparation, instrumentation, and final disposal | Holistic, lifecycle-oriented evaluation |

| AGREE (Analytical GREEnness) [2] | Numerical Score & Circular Pictogram | 0-1 (Higher score = greener) | All 12 GAC principles, with weighting possible | Comprehensive, user-friendly software-based tool |

| AGREEprep [4] [2] | Numerical Score & Pictogram | 0-1 (Higher score = greener) | Specific to sample preparation steps | Focused evaluation of sample prep greenness |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

The following protocols exemplify the practical application of GAC principles and the SIGNIFICANCE mnemonic in developing sustainable methodologies for pharmaceutical analysis.

Protocol 1: Green Solvent-Based Extraction for Herbal Drug Analysis

Application Note: This protocol describes a miniaturized, efficient extraction method for active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) from a powdered herbal matrix, replacing traditional Soxhlet extraction to significantly reduce solvent consumption, energy use, and waste generation [5] [1].

Principle: The method utilizes vortex-assisted extraction with a natural deep eutectic solvent (NADES), aligning with the GAC principles of using safe, natural reagents (S, C) and miniaturization to generate minimal waste (G) [3] [5].

I. Materials and Reagents

- Herbal Powder Sample: (e.g., 50 mg)

- NADES Solvent: Choline Chloride:Glycerol (1:2 molar ratio), prepared as per literature.

- Diluent: Ethanol-Water (1:1 v/v), HPLC grade.

- Centrifuge Tubes: 2 mL, safe-lock.

- Vortex Mixer

- Centrifuge

- Ultrasonic Bath

- Syringe Filters: Nylon, 0.22 µm.

- HPLC-VWD/DAD System

II. Procedure

- Weighing: Precisely weigh 50.0 mg of homogenized herbal powder into a 2 mL centrifuge tube.

- Extraction: Add 1.0 mL of the prepared NADES solvent to the tube.

- Vortexing: Securely cap the tube and vortex vigorously for 3 minutes at maximum speed.

- Sonication: Place the tube in an ultrasonic bath and sonicate for 10 minutes at 35°C.

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge the mixture at 12,000 rpm for 5 minutes to separate the supernatant from the solid residue.

- Dilution: Transfer 100 µL of the clear supernatant to a 1 mL volumetric flask and dilute to volume with Ethanol-Water diluent.

- Filtration: Pass the diluted extract through a 0.22 µm syringe filter into an HPLC vial.

- Analysis: Inject 10 µL into the HPLC system for analysis using a validated gradient method.

III. Greenness Assessment

- AGREE Score: Estimated >0.75 due to use of green solvent, miniaturized scale, and low energy consumption.

- Analytic Eco-Scale: Estimated >80 (Excellent greenness).

Protocol 2: Automated On-Line Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) Coupled with HPLC-UV for Trace Drug Analysis in Water

Application Note: This protocol integrates sample clean-up and concentration directly with chromatographic analysis, eliminating manual SPE steps, reducing solvent use, and enhancing throughput and reproducibility for monitoring pharmaceuticals in water [5].

Principle: This method embodies the principles of automation (A) and process integration (I), which reduces manual handling, improves safety, and minimizes overall resource consumption [4] [3].

I. Materials and Reagents

- Water Samples: Environmental or wastewater, 10 mL.

- Mobile Phase A: 0.1% Formic acid in water.

- Mobile Phase B: 0.1% Formic acid in acetonitrile.

- Loading Pump Solvent: HPLC-grade water.

- On-Line SPE Cartridge: C18, 2.0 mm x 10 mm, 5 µm.

- Analytical Column: C18, 4.6 mm x 100 mm, 3.5 µm.

- HPLC System: Equipped with a switching valve, dual pumps, and a UV detector.

II. Procedure

- Sample Loading: Using the loading pump, draw 5.0 mL of the filtered water sample and load it onto the conditioned on-line SPE cartridge at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. Divert the effluent to waste.

- Cartridge Washing: Wash the SPE cartridge with 1.0 mL of Loading Pump Solvent (2% Mobile Phase B) to remove weakly retained matrix interferences.

- Analytical Elution & Transfer: Activate the switching valve to place the SPE cartridge in-line with the analytical column and the gradient elution pump.

- Back-Flush Elution: Initiate the analytical gradient. Back-flush the analytes from the SPE cartridge onto the head of the analytical column using the initial gradient conditions (e.g., 5% B to 30% B in 0.5 min).

- Chromatographic Separation: Continue the analytical gradient to separate the analytes on the analytical column (e.g., 30% B to 95% B over 10 minutes).

- Detection: Detect the eluted analytes using the UV detector set at the appropriate wavelength.

- Re-equilibration: Re-equilibrate both the SPE cartridge and the analytical column to initial conditions for the next run.

III. Greenness Assessment

- NEMI Pictogram: Likely 3/4 green quadrants (fails on "hazardous waste" if acetonitrile is used).

- GAPI: Would show significant green/yellow coloring, with improvements over off-line SPE in sample preparation and waste sectors.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Green Analytical Chemistry

| Item / Technology | Function in GAC | Green Advantage |

|---|---|---|

| Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents (NADES) [5] | Extraction and reaction media | Biodegradable, low toxicity, prepared from renewable sources (e.g., choline chloride, sugars, organic acids). |

| Ionic Liquids (ILs) [1] | Non-volatile solvents for extraction and chromatography | Negligible vapor pressure, high thermal stability, tunable properties, can replace volatile organic solvents. |

| Solid-Phase Microextraction (SPME) Fibers [5] [1] | Solventless sample preparation and concentration | Eliminates need for large solvent volumes, integrates sampling, extraction, and concentration. |

| Stir Bar Sorptive Extraction (SBSE) [5] | Enrichment of analytes from liquid samples | High preconcentration capacity, solventless, reusable, compatible with thermal desorption. |

| Supercritical Fluid Chromatography (SFC) System [1] | Chromatographic separation | Uses supercritical CO₂ (non-toxic) as the primary mobile phase, drastically reducing organic solvent consumption. |

| Microextraction by Packed Sorbent (MEPS) [5] | Miniaturized solid-phase extraction | Dramatically reduces solvent and sample volumes (handles µL volumes), can be automated in a syringe. |

| Quick, Easy, Cheap, Effective, Rugged, and Safe (QuEChERS) Kits [5] | Sample preparation for complex matrices | Streamlined, low-solvent workflow for multi-analyte determination in food and environmental samples. |

The strategic integration of Green Analytical Chemistry principles, effectively guided by the SIGNIFICANCE mnemonic, provides a robust framework for developing analytical methods that align with global sustainability goals. The transition from a linear "take-make-dispose" model to a circular analytical chemistry framework is crucial for reducing the environmental footprint of pharmaceutical and chemical analysis [4]. This involves a conscious effort to select safer solvents, minimize waste, automate processes, and rigorously evaluate the greenness of methodologies using standardized metrics. As the field evolves, the adoption of these practices will be paramount for researchers and drug development professionals committed to fostering innovation while ensuring ecological stewardship and operational safety.

Analytical chemistry is fundamental to advancements in pharmaceutical development, environmental monitoring, and food safety. However, traditional analytical methods often rely on environmentally damaging practices, creating a paradox where the field responsible for monitoring environmental health contributes significantly to its degradation [9]. The conventional "take-make-dispose" model in analytical chemistry generates substantial solvent waste, consumes excessive energy, and utilizes hazardous reagents, creating an urgent need for sustainable methodologies [4].

The scale of this problem becomes particularly evident when examining pharmaceutical manufacturing. A case study on rosuvastatin calcium revealed that approximately 18,000 liters of mobile phase are consumed and disposed of annually for the chromatographic analysis of this single active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) across global production [10]. This example underscores the pervasive environmental burden of analytical methods when scaled across industries, highlighting the critical importance of addressing solvent waste, energy consumption, and overall environmental impact through green analytical chemistry principles.

Quantitative Assessment of Traditional Method Limitations

Solvent Consumption and Waste Generation

Traditional analytical methods, particularly in chromatography, are characterized by substantial solvent consumption throughout their lifecycle. The environmental impact extends beyond disposal to include energy-intensive production and purification processes.

Table 1: Environmental Impact of Solvent Use in Traditional Analytical Methods

| Aspect | Traditional Approach | Environmental Concern |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Solvents | Acetonitrile, Methanol [11] | Toxicity, resource-intensive production [12] [11] |

| Consumption Scale | ~18,000 L mobile phase/year for a single API [10] | High waste generation, depletion of resources |

| Waste Management | Incineration, landfill [11] | Air pollution, greenhouse gas emissions, soil/water contamination |

| Lifecycle Impact | Energy-intensive production and disposal [12] [10] | High cumulative carbon footprint |

The cumulative effect of solvent waste is magnified by the vast number of analytical tests performed daily across pharmaceutical quality control, research institutions, and environmental monitoring laboratories globally.

Energy Inefficiency in Analytical Instrumentation

Energy-intensive equipment constitutes another significant environmental limitation of traditional analytical methods. Instruments such as chromatographic systems with ovens, detectors, and pumps often operate for extended periods, contributing substantially to laboratory energy consumption [11].

Table 2: Energy Consumption in Traditional Analytical Practices

| Component | Traditional Practice | Environmental Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Chromatography Systems | Extended run times, high flow rates [11] | High kWh per sample, increased carbon footprint |

| Sample Preparation | Soxhlet extraction, prolonged heating [4] | High energy demand per sample |

| Idle Operation | Instruments left running continuously [11] | Unnecessary energy waste during standby periods |

| Temperature Control | Poorly insulated ovens/chambers [11] | Excessive heat loss requiring compensatory energy |

The environmental impact of this energy consumption varies significantly based on local energy grids but contributes directly to carbon emissions and resource depletion, highlighting the need for more energy-efficient instrumentation and practices.

Greenness Assessment Tools for Method Evaluation

The development of standardized metrics has been crucial in quantifying the environmental impact of analytical methods, enabling objective comparisons and guiding sustainability improvements. Multiple assessment tools have emerged, each with distinct strengths and applications.

Table 3: Comparison of Greenness Assessment Tools for Analytical Methods

| Assessment Tool | Type of Output | Scope | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEMI [13] | Pictogram (binary) | General analytical | Simple, user-friendly | Lacks granularity, limited workflow assessment |

| Analytical Eco-Scale [13] [10] | Numerical score (0-100) | General analytical | Semi-quantitative, enables direct comparison | Relies on expert judgment, no visual component |

| GAPI [13] [10] | Color-coded pictogram | Comprehensive workflow | Visual, detailed process breakdown | No overall score, some subjectivity in coloring |

| AGREE [13] [10] | Pictogram + numerical score (0-1) | General analytical | Comprehensive, aligns with 12 GAC principles | Subjective weighting, limited pre-analytical coverage |

| AMGS [10] | Numerical score | Chromatography | Specific to LC, includes instrument energy | Limited to chromatographic methods |

| AGREEprep [13] | Pictogram + numerical score (0-1) | Sample preparation | Focuses on often-overlooked sample preparation | Must be used with other tools for full method assessment |

| AGSA [13] | Star diagram + score | Comprehensive workflow | Intuitive visualization, integrated scoring | Relatively new tool with evolving implementation |

| CaFRI [13] | Numerical score | Climate impact | Focuses on carbon footprint estimation | Narrow focus on climate impacts only |

The progression from basic binary assessments to multidimensional quantitative tools reflects the analytical chemistry community's growing commitment to comprehensive environmental responsibility. The AGREEprep tool, specifically designed for sample preparation, addresses a critical gap as this stage often involves substantial solvent use, energy consumption, and hazardous reagents [13]. For holistic method evaluation, the trend is toward using complementary metrics that provide different perspectives on environmental impact rather than relying on a single tool.

Experimental Protocols for Green Method Assessment and Implementation

Protocol: Comprehensive Greenness Assessment Using Multiple Metrics

This protocol provides a standardized approach for evaluating the environmental performance of analytical methods using complementary assessment tools.

Materials and Software Requirements:

- Method details (sample preparation, reagents, instrumentation, waste data)

- AGREE online calculator or software [10]

- AGREEprep assessment tool [13]

- GAPI or MoGAPI scoring sheet [13]

- GreenSOL web application (for solvent evaluation) [12]

Procedure:

- Compile Method Inventory: Document all method parameters including sample size, collection method, preservation requirements, transportation, storage conditions, and all equipment requirements.

- Quantify Inputs and Outputs: Measure exact volumes of all solvents and reagents consumed per sample, including mobile phases, extraction solvents, derivatization agents, and cleaning solutions. Record energy consumption (kWh) of all instruments used throughout the method.

- Characterize Waste Streams: Identify and quantify all waste generated including organic solvents, aqueous waste, solid waste, and consumables. Note any recycling or treatment procedures.

- Evaluate Solvent Greenness: Utilize the GreenSOL web application to assess the environmental profile of each solvent across its lifecycle from production to waste treatment [12].

- Apply AGREE Assessment: Input method parameters into the AGREE calculator, assigning appropriate weights to each of the 12 principles based on method priorities. Generate the pictogram and numerical score for overall greenness evaluation [10].

- Conduct AGREEprep Evaluation: For sample preparation steps, use AGREEprep to specifically assess this high-impact stage, noting areas for improvement in solvent selection, energy use, and waste generation [13].

- Perform Complementary Assessments: Apply additional relevant metrics such as CaFRI for carbon footprint estimation or AGSA for star-based visualization to gain different perspectives on environmental impact [13].

- Interpret Consolidated Results: Compare scores across tools to identify consistent environmental weaknesses and prioritize improvement opportunities. Establish baseline metrics for future optimization.

Protocol: Solvent Waste Reduction in Liquid Chromatography

This protocol provides specific methodologies for reducing solvent consumption in chromatographic analyses, one of the most significant sources of waste in analytical laboratories.

Materials:

- UHPLC system capable of withstanding high pressures

- Columns with smaller particle sizes (sub-2μm)

- Alternative green solvents (ethanol, supercritical CO₂)

- Solvent recycling system

- Method translation software

Procedure:

- Method Transfer from HPLC to UHPLC:

- Select appropriate UHPLC column with chemistry similar to original method (e.g., C18, phenyl)

- Adjust method parameters: reduce column dimensions to 50-100mm length, 2.1mm diameter

- Optimize flow rate: typically 0.2-0.6 mL/min instead of 1.0-2.0 mL/min in conventional HPLC

- Shorten run time proportionally while maintaining resolution

- Perform system suitability testing to ensure performance equivalence

Green Solvent Substitution:

- Evaluate methanol as alternative to acetonitrile where possible

- Assess ethanol-based mobile phases for normal-phase separations

- For appropriate applications, implement supercritical fluid chromatography (SFC) using CO₂ as primary mobile phase [11]

- Use GreenSOL tool to compare environmental profiles of solvent options [12]

Solvent Recycling Implementation:

- Install closed-loop recycling system for mobile phase preparation

- Segregate waste streams by solvent type to facilitate recycling

- Implement distillation equipment for on-site solvent purification

- Establish quality control procedures to ensure recycled solvent purity

Method Validation:

- Verify accuracy, precision, specificity, and robustness of modified methods

- Document comparative validation data between traditional and green methods

- Calculate solvent savings and waste reduction metrics

Protocol: Energy Optimization in Analytical Workflows

This protocol addresses the significant energy consumption associated with analytical instrumentation and laboratory operations.

Materials:

- Energy monitoring equipment

- Automated sample preparation systems

- Modern chromatography systems with energy-saving features

- Method development software

Procedure:

- Equipment Energy Assessment:

- Install energy monitors on analytical instruments to establish baseline consumption

- Identify high-consumption equipment (GC-MS, LC-MS, ICP systems)

- Document instrument usage patterns and idle time energy draw

Chromatography System Optimization:

- Enable energy-saving modes during idle periods

- Implement lower column temperatures where separation efficiency permits

- Reduce detector energy consumption (e.g., lower nebulizer gas flow in LC-MS)

- Consolidate analyses to maximize instrument utilization

Sample Preparation Efficiency:

- Implement automated parallel processing systems to increase throughput [4]

- Replace Soxhlet extraction with ultrasound-assisted or microwave-assisted extraction

- Utilize vortex mixing for enhanced mass transfer instead of energy-intensive heating [4]

- Integrate multiple preparation steps into single workflows to reduce overall processing

Workflow Re-engineering:

- Develop staggered injection sequences to minimize instrument idle time

- Implement predictive analytics to optimize run schedules

- Establish shutdown procedures for extended non-use periods

- Create equipment sharing programs to maximize utilization across teams

Monitoring and Continuous Improvement:

- Track energy consumption per sample over time

- Set reduction targets and implement regular review cycles

- Include energy efficiency criteria in new instrument procurement decisions

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Materials for Green Analytical Chemistry

| Item | Function | Green Alternative | Environmental Benefit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) [14] | Extraction of metals, bioactive compounds | Customizable mixtures of HBA/HBD | Biodegradable, low toxicity, renewable sourcing |

| Supercritical CO₂ [11] | Chromatographic mobile phase | Replacement for organic solvents | Non-toxic, non-flammable, easily removed |

| Ethanol [11] | Solvent for extraction, chromatography | Replacement for acetonitrile/methanol | Lower toxicity, bio-based production |

| Water-based Reactions [14] | Reaction medium for synthesis | Replacement for organic solvents | Non-toxic, non-flammable, inexpensive |

| Niobium-based Catalysts [15] | Biomass conversion catalysis | Replacement for rare metal catalysts | Abundant, water-tolerant, efficient |

| Biodegradable Membranes [16] | Sample preparation, microextraction | Replacement for plastic/polymer | Reduced plastic waste, compostable |

| Biogenic Metal Nanoparticles [16] | Sensors for environmental pollutants | Green synthesis from plant extracts | Avoids harsh chemical reductants |

| NADES [16] | Dispersive liquid-liquid microextraction | Alternative to conventional organic solvents | Biodegradable, low toxicity, tunable properties |

Integrated Workflow for Green Method Development

The transition to sustainable analytical practices requires a systematic approach that integrates green principles at each stage of method development and implementation. The following workflow provides a logical pathway for achieving this integration.

Diagram 1: Green Method Development Workflow. This systematic approach integrates sustainability considerations at each stage of analytical method development and implementation.

The implementation of green analytical chemistry requires moving beyond incremental improvements to embrace disruptive innovations that prioritize both ecological responsibility and analytical performance. As noted by Psillakis, achieving strong sustainability in analytical chemistry would require "a fundamental shift away from current unsustainable practices toward disruptive innovations that prioritize nature conservation" [4]. This transition demands coordination across all stakeholders—manufacturers, researchers, routine laboratories, and policymakers—to break down traditional silos and build collaborative bridges toward a waste-free and resource-efficient analytical sector [4].

White Analytical Chemistry (WAC) represents a significant evolution in sustainable analytical science, emerging as a holistic paradigm that transcends the primarily eco-centric focus of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC). Founded in 2021, WAC provides a comprehensive framework for evaluating analytical methods by balancing three critical dimensions: analytical performance (Red), environmental impact (Green), and practical & economic considerations (Blue) [17] [18]. This integrated approach addresses a fundamental limitation of conventional green chemistry principles, which often prioritized environmental considerations without systematically accounting for methodological practicality and analytical efficacy [19].

The conceptual foundation of WAC employs the RGB color model as an analogy, where the balanced integration of all three primary aspects—Red, Green, and Blue—produces "white" light, symbolizing an ideal analytical method [18]. In this model, the "whiteness" of a method reflects the coherence and synergy between its analytical, ecological, and practical attributes [18]. This framework strives for a sustainable compromise that avoids unconditional increases in greenness at the expense of functionality, thereby aligning more closely with the comprehensive goals of sustainable development [18].

Theoretical Framework: The RGB Model

The Three Dimensions of WAC

The RGB model establishes three independent axes for evaluating analytical methods, providing a more balanced assessment compared to single-dimensional greenness metrics [17] [18].

Red Component - Analytical Performance: This dimension encompasses traditional parameters that define method quality and reliability, including sensitivity, selectivity, accuracy, precision, linearity, robustness, and trueness [17] [19]. The red component ensures that environmental sustainability does not compromise the fundamental analytical requirements necessary for generating valid scientific data.

Green Component - Environmental Impact: Derived from Green Analytical Chemistry principles, this dimension addresses the environmental footprint of analytical processes [18]. It evaluates factors including waste generation and prevention, energy consumption and efficiency, toxicity of reagents and solvents, operator safety, and the use of renewable resources [17] [5].

Blue Component - Practical & Economic Factors: This dimension assesses the practical implementation aspects of analytical methods, focusing on their feasibility in routine laboratory settings [17]. Key considerations include cost-effectiveness, analysis time, simplicity of operation, equipment requirements, potential for automation, and user-friendliness [18] [19].

The RGB Workflow and Method Assessment

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and synergistic relationship between the three dimensions of WAC in developing and evaluating an analytical method.

Evolution from Green to White Analytical Chemistry

The progression from GAC to WAC represents a paradigm shift in how the analytical community conceptualizes sustainability. While GAC provided crucial initial guidance for reducing the environmental impact of analytical practices, its primary focus on ecological factors created an inherent limitation [18]. This often resulted in methodologies that were environmentally sound but impractical for routine implementation due to cost, complexity, or insufficient analytical performance [17].

WAC addresses this limitation by explicitly recognizing that true sustainability in analytical chemistry requires a balanced integration of all three dimensions [18]. A method that excels in greenness but fails to provide adequate sensitivity, or one that delivers exceptional performance at prohibitive cost or environmental impact, cannot be considered truly sustainable [19]. The whiteness metric thus serves as a more holistic indicator of a method's overall value and practicality in real-world applications [18].

Application Notes: Implementing WAC in Pharmaceutical Analysis

WAC-Driven Method Development in Pharmaceutical Impurity Profiling

The application of WAC principles is particularly transformative in pharmaceutical impurity profiling, where regulatory requirements demand high analytical performance while economic and environmental pressures necessitate sustainable practices [20].

Case Study: Green RP-HPLC Method for Antihypertensive Combinations A practical implementation of WAC involved the development of a reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) method for the simultaneous analysis of azilsartan, medoxomil, chlorthalidone, and cilnidipine in human plasma [19]. The development strategy employed an Analytical Quality by Design (AQbD) approach guided by WAC principles, systematically optimizing all three RGB dimensions [19].

- Red Dimension Optimization: The method was validated according to International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) guidelines, demonstrating excellent sensitivity, specificity, linearity, accuracy, and precision suitable for bioanalytical applications [19].

- Green Dimension Enhancement: The method incorporated eco-friendly solvents where feasible, minimized waste generation through optimized mobile phase composition, and reduced energy consumption by exploring shorter run times and alternative detection strategies [19].

- Blue Dimension Considerations: The AQbD approach ensured robust method performance across operable ranges, enhancing practical reliability while controlling costs through optimized reagent consumption and increased throughput [19].

The resulting method achieved an excellent white WAC score, successfully balancing the necessary analytical performance for regulatory submission with improved sustainability and practical efficiency [19].

Comparative Analysis of Green Analytical Techniques

The table below summarizes key green analytical techniques applicable to pharmaceutical impurity profiling, with their relative performance across the RGB dimensions.

Table 1: Green Analytical Techniques for Pharmaceutical Impurity Profiling

| Technique | Principle | Red (Analytical) Performance | Green (Environmental) Advantages | Blue (Practical) Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supercritical Fluid Chromatography (SFC) [20] | Uses supercritical CO₂ as mobile phase | High selectivity for chiral separations | Significantly reduces organic solvent consumption; uses non-toxic CO₂ | Higher initial instrument cost; requires specialized expertise |

| Capillary Electrophoresis (CE) [20] | Separation based on charge-to-size ratio | Excellent efficiency; suitable for ionic compounds | Minimal solvent consumption and waste generation | Can have lower sensitivity vs. HPLC; requires method optimization |

| Green Liquid Chromatography (GLC) [20] | HPLC with green solvents & columns | Comparable to conventional HPLC | Reduces hazardous solvent use (e.g., ethanol replaces acetonitrile) | Easy transition from existing methods; minimal retraining |

| UHPLC with Narrow-Bore Columns [20] | Enhanced efficiency with smaller particles | Improved resolution and sensitivity | Up to 90% reduction in mobile phase consumption [20] | Requires high-pressure capable systems; method transfer needed |

| Non-Destructive Spectroscopy (NIR, Raman) [20] | Direct chemical analysis without separation | Minimal sample preparation; rapid analysis | Solventless; minimal waste; low energy consumption | Requires chemometrics; model development needed |

WAC Assessment Tools and Metrics

The implementation of WAC requires practical tools for quantifying the "whiteness" of analytical methods. Several metrics have been developed to address this need, building upon established greenness assessment tools while incorporating analytical and practical dimensions.

Table 2: Metrics for Assessing White Analytical Chemistry

| Metric/Tool | Year | Assessment Dimensions | Key Features | Output Format |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Red Analytical Performance Index (RAPI) [17] | 2025 | Red (Primary) | Evaluates reproducibility, trueness, recovery, matrix effects, and other analytical parameters | Numerical score & pictogram |

| Blue Applicability Grade Index (BAGI) [17] | 2024 | Blue (Primary) | Assesses practical aspects: cost, time, simplicity, automation, number of analytes | Pictogram with blue shading |

| Analytical Green Star Area (AGSA) [17] | 2025 | Green (Primary) | Considers automation, miniaturization, sample preparation, operator safety | Star-area diagram |

| Modified GAPI (MoGAPI) [17] | 2024 | Green (Primary) | Extends GAPI to include storage, transport, number of samples/reagents, energy, total waste | Color-coded pictogram |

| White Assessment [18] | 2021 | Red, Green, Blue (Integrated) | RGB 12 algorithm balances all three dimensions for overall "whiteness" score | Combined whiteness metric |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: WAC-Guided Method Development and Validation for Pharmaceutical Compounds

This protocol provides a systematic approach for developing analytical methods guided by White Analytical Chemistry principles, applicable to drug substances and products.

I. Method Scouting and Initial Setup

Analytical Quality by Design (AQbD) Planning:

- Define the Analytical Target Profile (ATP) specifying required Red dimension criteria (e.g., sensitivity, precision, specificity) [19].

- Identify Critical Method Parameters (CMPs) and Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) using prior knowledge and risk assessment tools.

- Establish the Design Space through structured Design of Experiment (DoE) methodologies [19].

Green Solvent Screening:

- Evaluate alternatives to hazardous solvents (e.g., ethanol or methanol取代 acetonitrile, aqueous mobile phases) [20].

- Test solubility and stability of analytes in green solvent systems.

- Assess chromatographic performance (peak shape, resolution) with green mobile phases.

Instrumentation and Column Selection:

- Prefer UHPLC systems over conventional HPLC for higher efficiency and lower solvent consumption [20].

- Select narrow-bore columns (e.g., ≤2.1 mm internal diameter) to reduce mobile phase consumption by up to 90% [20].

- Consider elevated temperature liquid chromatography to reduce mobile phase viscosity and enable faster separations [20].

II. Optimization and Greenness Assessment

Multivariate Optimization:

- Optimize separation parameters (gradient time, temperature, flow rate) using Response Surface Methodology (RSM).

- Balance analysis time (Blue dimension) against resolution (Red dimension).

Greenness Evaluation:

- Calculate the Analytical Method Greenness Score (AMGS) assessing solvent energy, safety/toxicity, and instrument energy consumption [10].

- Apply complementary metrics (AGREE, GAPI) for comprehensive environmental impact assessment [10].

- Identify areas for green improvement (solvent replacement, waste reduction, energy efficiency).

III. Validation and Whiteness Scoring

Method Validation:

- Perform validation per ICH guidelines Q2(R1) assessing specificity, accuracy, precision, linearity, range, detection and quantification limits (Red dimension) [20].

- Include robustness testing using DoE to establish method operable ranges.

Whiteness Assessment:

- Score the method using the RGB 12 algorithm [18] or applicable WAC metrics.

- Calculate individual scores for Red (analytical performance), Green (environmental impact), and Blue (practicality) dimensions.

- Determine the overall whiteness score reflecting method balance and sustainability.

Continuous Improvement:

- Monitor method performance during routine use.

- Identify opportunities for further green improvements (solvent recycling, waste management).

- Implement lifecycle management for ongoing sustainability enhancement.

Protocol 2: Green Sample Preparation Using Microextraction Techniques

This protocol outlines green sample preparation approaches that align with WAC principles, focusing on miniaturized systems that reduce solvent consumption while maintaining analytical performance.

I. Method Selection Based on Application Needs

Sample Type Assessment:

- For liquid samples: Consider fabric phase sorptive extraction (FPSE), capsule phase microextraction (CPME), or dispersive liquid-liquid microextraction (DLLME) [17].

- For solid samples: Evaluate ultrasound-assisted microextraction or quick, easy, cheap, effective, rugged, and safe (QuEChERS) approaches [5].

Sorbent/Solvent Selection:

II. Microextraction Procedure

Fabric Phase Sorptive Extraction (FPSE):

- Condition the FPSE media by immersing in appropriate solvent.

- Add sample to media and incubate with agitation for predetermined time.

- Elute analytes using minimal volume of green solvent (e.g., ethanol/water mixtures).

- Analyze eluent directly or after minimal processing.

Magnetic Solid-Phase Extraction (MSPE):

- Disperse magnetic sorbent (e.g., functionalized magnetic nanoparticles) in sample solution.

- Mix thoroughly to allow analyte adsorption onto sorbent surface.

- Separate sorbent using external magnet and decant solution.

- Wash sorbent if needed, then elute analytes with small solvent volume.

- Directly inject eluent for analysis.

III. Method Validation and Greenness Assessment

Performance Validation:

- Determine extraction efficiency, recovery, precision, and matrix effects.

- Validate against reference methods or standard addition approaches.

Greenness Evaluation:

- Apply greenness metrics (AGREEprep, Analytical Eco-Scale) specifically designed for sample preparation [10].

- Compare solvent consumption, waste generation, and energy use against conventional techniques (e.g., liquid-liquid extraction, solid-phase extraction).

- Document Green dimension improvements while ensuring Red dimension requirements are met.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The practical implementation of WAC requires specific materials and reagents that enable greener analytical practices without compromising performance. The following table details key solutions for developing white analytical methods.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for White Analytical Chemistry

| Reagent/Material | Function in WAC | Green & Practical Advantages | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) [5] [20] | Green extraction media; mobile phase additives | Biodegradable; low toxicity; renewable sources | Replace conventional organic solvents in sample preparation |

| Ethanol-Water Mobile Phases [20] | Chromatographic separation | Reduce reliance on toxic acetonitrile; cheaper; biodegradable | Effective for reversed-phase separations with method optimization |

| Magnetic Nanoparticles [17] | Sorbents for microextraction | Enable rapid separation; reusable; reduce solvent consumption | Functionalize surface for specific analyte retention |

| Narrow-Bore UHPLC Columns (e.g., ≤2.1 mm ID) [20] | High-efficiency separations | Reduce mobile phase consumption by up to 90% | Require compatible instrumentation; minimize extra-column volume |

| Ionic Liquids [20] | Stationary phases; extraction solvents; additives | Low volatility; tunable properties; reduce solvent consumption | Select based on hydrophobicity and solvation properties |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) [20] | Selective sorbents for sample preparation | High specificity; reusable; reduce sample processing | Custom synthesis needed for target analytes |

| Supercritical CO₂ [20] | Mobile phase for SFC | Non-toxic; recyclable; eliminates organic solvent waste | Requires specialized SFC instrumentation |

White Analytical Chemistry represents a paradigm shift in how the analytical community conceptualizes and evaluates methodological sustainability. By integrating the three fundamental dimensions of analytical performance (Red), environmental impact (Green), and practical considerations (Blue), WAC provides a more holistic framework for developing analytical methods that are not only scientifically valid but also environmentally responsible and practically feasible [17] [18].

The implementation of WAC principles, supported by the experimental protocols and assessment tools outlined in this article, enables researchers to make informed decisions that balance sometimes competing priorities [19]. As the field continues to evolve, the adoption of WAC is expected to drive innovation in green method development while ensuring that sustainable practices do not come at the expense of analytical quality or practical utility [17] [10]. This balanced approach ultimately supports the broader goals of sustainable development in pharmaceutical analysis and other chemical measurement sciences.

The strategic development of green analytical methods is no longer an optional pursuit but a critical component of modern pharmaceutical research and development. This transformation is driven by a powerful convergence of stringent global regulations, ambitious corporate sustainability targets, and the pioneering tools and frameworks advanced by the ACS Green Chemistry Institute (GCI) and its Pharmaceutical Roundtable (GCIPR). These forces collectively address the environmental impacts of analytical laboratories, which traditionally consume high volumes of toxic solvents and generate substantial waste [21].

This application note provides a detailed framework for integrating these drivers into practical analytical workflows. It introduces the White Analytical Chemistry (WAC) model as a holistic evolution from Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC), detailing standardized protocols for method evaluation, solvent substitution, and regulatory preparedness to guide researchers and drug development professionals in achieving superior sustainability without compromising analytical performance [21].

The Driving Forces in Detail

The Regulatory Push

The global regulatory landscape for corporate sustainability is rapidly evolving, moving beyond voluntary reporting to mandatory, detailed disclosures. These regulations create a direct operational imperative for adopting greener analytical methods.

Table 1: Key Upcoming Sustainability Regulations Impacting the Chemical and Pharmaceutical Sectors

| Regulation | Jurisdiction | Key Requirements | Key Timeline |

|---|---|---|---|

| Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) [22] | European Union | Comprehensive ESG disclosure based on double materiality. | Reporting on 2025 data for large companies begins January 2026. |

| Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) [22] | European Union | Financial adjustments on embedded carbon in imported goods. | Full implementation with financial obligations begins January 2026. |

| Climate Corporate Data Accountability Act (SB 253) [22] | California, USA | Mandatory disclosure of Scope 1, 2, and 3 greenhouse gas emissions. | Scope 1 & 2 reporting begins in 2026; Scope 3 in 2027. |

| EPA Methylene Chloride Rule [23] | United States | Restricts commercial and industrial use of methylene chloride. | Academic compliance effective July 2024; industrial/commercial by 2026. |

| Eco-design for Sustainable Products Regulation (ESPR) [22] | European Union | Introduces Digital Product Passports (DPP) for sustainability data. | Sector-specific DPP requirements phase in from 2027. |

These regulations underscore the need for robust, data-driven environmental accounting. For analytical chemists, this translates to a need for precise metrics on solvent consumption, energy use, and waste generation associated with every method [22].

Corporate Sustainability Goals

Corporate sustainability has transitioned from a peripheral concern to a core business strategy, driven by investor focus on ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) performance, customer demand for greener products, and the pursuit of operational efficiency [24]. Leading chemical and pharmaceutical companies are embedding sustainability into their innovation pipelines and supply chains, which includes greening laboratory practices. Industry professionals are now in roles dedicated to leading Scope 3 greenhouse gas inventorying, conducting Life Cycle Assessments (LCA), and integrating bio-circular raw materials into product lines [25]. This corporate-level commitment provides the top-down support and resources necessary for labs to invest in and transition to sustainable analytical methods.

The ACS Green Chemistry Institute as a Catalytic Force

The ACS Green Chemistry Institute (GCI), and particularly its Pharmaceutical Roundtable (GCIPR), serves as a critical nexus, bridging regulatory demands, corporate goals, and practical laboratory implementation. The GCIPR, a collaboration between the ACS GCI and the pharmaceutical industry, is strategically focused on developing "free, publicly accessible elite tools" to enable better chemical approaches [26]. Key tools that directly support green analytical method development include:

- The Analytical Method Greenness Score (AMGS) Calculator: A web-based, publicly available tool that benchmarks the greenness of chromatography methods by evaluating solvent use, energy consumption, and waste production [26]. The tool is being expanded in 2025 to include gas chromatography and is evolving towards an AI-informed interface [26].

- The Process Mass Intensity – Life Cycle Assessment (PMI-LCA) Tool: A high-level estimator that combines mass and environmental life cycle information for synthesis processes. The GCIPR is currently developing a database-enabled online version to enhance accessibility and standardize environmental impact assessments [26].

A New Framework: White Analytical Chemistry (WAC)

White Analytical Chemistry (WAC) is an emerging, holistic framework that strengthens traditional Green Analytical Chemistry by integrating environmental metrics with analytical performance and practical usability [21]. This model is visualized using the Red-Green-Blue (RGB) color model.

Diagram 1: The White Analytical Chemistry (WAC) RGB Model. This framework ensures methods are analytically sound (Red), environmentally sustainable (Green), and economically practical (Blue).

The WAC model provides a balanced scorecard, preventing the common pitfall of sacrificing accuracy for greenness or vice-versa. It enables a systematic evaluation of method "whiteness," guiding researchers toward truly optimal and sustainable analytical procedures [21].

Application Notes & Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Comprehensive Greenness Assessment of an HPLC Method Using the AMGS Calculator

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for evaluating the environmental impact of a standard HPLC method and identifying areas for improvement.

I. Pre-Assessment Data Collection

- Gather all method parameters: Mobile phase composition and volume, flow rate, column dimensions, run time, and sample preparation steps.

- Quantify the type and volume of all solvents and reagents used, including those for standard/stock solution preparation, sample dissolution, and system conditioning.

II. AMGS Calculator Input and Execution

- Access the free, web-based AMGS calculator (available through the ACS GCIPR tools page) [26].

- Select the chromatography technique (e.g., Liquid Chromatography).

- Input the collected method parameters into the respective fields in the tool.

- The calculator will generate a quantitative greenness score and a breakdown of contributing factors.

III. Data Interpretation and Improvement Strategy

- Analyze the score components to identify the largest contributors to environmental impact (e.g., high-volume solvent use, high-energy instrumentation).

- Develop an alternative method strategy targeting the key impact areas.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Greener HPLC Method Development

| Item / Reagent | Traditional Choice | Green Alternative | Function & Rationale for Substitution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Organic Solvent | Acetonitrile | Ethanol or Bio-derived Acetonitrile | Function: Mobile phase modifier. Rationale: Ethanol is less toxic and bio-renewable. Reduces environmental and safety hazards [21]. |

| Toxic Modifier | Methylene Chloride (DCM) | 2-Methyltetrahydrofuran (2-MeTHF) or Ethyl Acetate | Function: Strong elution solvent. Rationale: DCM is a suspected carcinogen facing regulatory restrictions (EPA). 2-MeTHF offers comparable elutropic strength from a renewable source [23]. |

| Sample Dissolution Solvent | High-purity Methanol | Aqueous buffers or less toxic solvents | Function: Dissolving analyte for injection. Rationale: Minimizing use of high-purity, hazardous solvents reduces toxicity and waste burden [26]. |

| Chromatography Column | 150-250 mm, 4.6 mm i.d., 5 µm | 50-100 mm, 2.1-3.0 mm i.d., sub-2 µm | Function: Separation. Rationale: Smaller columns and particle sizes reduce mobile phase consumption by up to 90% and shorten run times, saving solvent and energy [21]. |

Protocol 2: Implementing a Methylene Chloride Substitution Study in Analytical Laboratories

With the EPA's ruling on methylene chloride restricting its use, labs must proactively identify and validate alternatives [23].

I. Risk Assessment and Inventory

- Audit all analytical methods (HPLC, extraction, dissolution) and cleaning procedures for DCM usage.

- Prioritize methods for substitution based on DCM volume and frequency of use.

II. Identification and Evaluation of Substitutes

- Consult Resources: Utilize the "DCM Alternatives & Resources" provided by the ACS GCI [23].

- Select Candidates: Based on chemical properties (e.g., polarity, solubility), select candidate solvents like 2-MeTHF, Cyrene (dihydrolevoglucosenone), or ethyl acetate.

- Initial Scouting: Perform preliminary tests to assess the alternative solvent's ability to dissolve the analyte and achieve baseline separation. Use Analytical Quality by Design (AQbD) and Design of Experiment (DoE) principles to systematically evaluate critical method parameters (e.g., gradient profile, temperature) [21].

III. Method Validation and Documentation

- Validate the final method using the alternative solvent against ICH Q2(R1) guidelines, ensuring accuracy, precision, specificity, and robustness.

- Calculate and compare the greenness score of the new method versus the old method using the AMGS calculator.

- Update all Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) and conduct training for relevant personnel.

Workflow for a WAC-Driven Analytical Method Transition

The following diagram outlines a logical workflow for transitioning from a conventional analytical method to an optimized, WAC-compliant one, integrating regulatory triggers, assessment tools, and the WAC framework.

Diagram 2: Workflow for a WAC-Driven Analytical Method Transition. This process ensures new methods meet regulatory, environmental, and performance criteria.

The strategic adoption of green analytical methods is imperative for the future of pharmaceutical research. The synergistic push from global regulations, corporate sustainability mandates, and the practical tools and frameworks provided by the ACS Green Chemistry Institute creates a clear and actionable path forward. By adopting the White Analytical Chemistry model and implementing the detailed protocols for method assessment and solvent substitution outlined in this document, researchers and drug development professionals can effectively future-proof their laboratories. This approach not only ensures compliance and reduces environmental impact but also drives innovation, enhances operational efficiency, and builds long-term value.

In the pharmaceutical industry and analytical chemistry, the environmental footprint of operations is increasingly scrutinized. While robust and precise, traditional analytical methodologies often rely on resource-intensive practices that pose significant environmental challenges [5]. Two key measurement tools, Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) and Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Inventories, are central to quantifying and managing this impact. Used in tandem, they provide a holistic understanding that guides sustainable analytical method development, enabling researchers and drug development professionals to balance analytical performance with ecological responsibility [27] [5].

Conceptual Framework: LCA vs. GHG Inventories

While both LCA and GHG inventories are essential for environmental baselining, they serve distinct purposes and offer different insights. Understanding their synergies is the first step in building a comprehensive sustainability strategy.

Table 1: Comparison of LCA and GHG Inventory Methods

| Feature | Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) | Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Inventory |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | Evaluate environmental impacts of a product or service throughout its life cycle [27] [28]. | Summate all GHG emissions from an organization across its value chain to support reporting and track progress against reduction targets [27]. |

| Scope of Impact | Multi-criteria, including GHG emissions, energy use, water consumption, air quality, and resource depletion [27] [28]. | Focused exclusively on greenhouse gas emissions, categorized into Scope 1, 2, and 3 [27]. |

| Typical Application | Product-level analysis, eco-design, Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs), identifying environmental hotspots in a product's life cycle [27] [29]. | Organization-level analysis, corporate sustainability reporting, setting science-based targets, and meeting regulatory disclosures like CSRD [27]. |

| Synergistic Value | Provides high-specificity data for Scope 3 categories of a GHG inventory, making it more actionable [27]. | Offers a macro-level view of organizational emissions, guiding strategic priorities which can be further investigated with LCA [27]. |

The Synergy Between LCA and GHG Inventories

The most significant synergy lies in using LCA to enhance the accuracy and actionability of corporate GHG inventories, particularly for Scope 3, Category 1 (Purchased Goods and Services). While GHG inventories often use spend-based data to estimate these emissions, replacing these averages with product-specific data from LCAs yields a more precise and actionable footprint [27]. For example, the LCA of a specific solvent used in analytical methods can provide exact emission data for that purchase, rather than relying on a generic industry average.

Quantifying Analytical Method Impact: The LCA Perspective

Adopting a life cycle mindset is crucial for understanding the cumulative environmental impact of analytical methods, which is often underestimated.

The Life Cycle of an Analytical Method

The following workflow diagrams the life cycle stages of an analytical method and the corresponding LCA phases used for its assessment.

Diagram 1: Analytical method life cycle and LCA phases.

Cumulative Impact: A Pharmaceutical Case Study

The perception that analytical methods have an insignificant environmental impact is misleading. A case study on the manufacturing of rosuvastatin calcium, a widely used generic drug, illustrates the substantial cumulative effect [10].

- The process involves approximately 25 liquid chromatography (LC) analyses per batch across 9 isolated intermediates.

- Each batch consumes an estimated 18 liters of mobile phase for chromatographic analysis.

- Scaling to an estimated 1,000 batches annually, this results in the consumption and disposal of approximately 18,000 liters of mobile phase for a single active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) [10].

This case underscores the urgent need for sustainable approaches to analytical method design.

Protocol for Green Analytical Method Development

This protocol provides a detailed methodology for developing and assessing the environmental footprint of analytical methods using green chemistry principles and LCA.

Experimental Workflow for Method Development and Assessment

The path to a greener analytical method involves strategic choices at each stage of development, followed by a standardized assessment of its environmental performance.

Diagram 2: Green method development and assessment workflow.

Step-by-Step Experimental Protocol

Phase 1: Goal and Scope Definition

- Define Functional Unit: Clearly define the analytical method's purpose (e.g., "the quantification of API X in a tablet with a precision of RSD < 2%").

- Set System Boundaries: Decide on a

cradle-to-gate(from raw material to analysis completion) orcradle-to-grave(including waste disposal) assessment [28] [29]. - Select Impact Categories: Choose relevant environmental impact categories beyond climate change, such as water consumption, resource depletion, and toxicity [28].

Phase 2: Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) - Data Collection

- Solvents and Reagents: Accurately record the type, quantity, and source of all solvents and reagents used in sample preparation and mobile phases. Prioritize primary data from suppliers [29].

- Energy Consumption: Measure or obtain data on the energy consumption (in kWh) of all instruments used (e.g., HPLC, GC, MS) over a standard method runtime. Note: Instrument energy is a key component of the AMGS metric [10].

- Waste Generation: Quantify all waste streams generated, including organic solvents, aqueous waste, and solid waste, and identify their disposal pathways [5].

Phase 3: Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA) - Data Translation

- Apply Characterization Factors: Use standardized databases and factors to translate inventory data into environmental impacts. For GHG emissions, use CO₂-equivalents [29].

- Calculate a Greenness Metric: Employ a dedicated metric to synthesize the LCI data into a single score. The Analytical Method Greenness Score (AMGS) is a comprehensive metric that evaluates solvent energy, solvent EHS (Environment, Health, Safety), and instrument energy consumption [10]. Alternative tools include AGREE, Analytical Eco-Scale, or GAPI [10].

Phase 4: Interpretation and Improvement

- Identify Hotspots: Analyze the results to pinpoint the life cycle stages or materials contributing most to the environmental impact.

- Iterate and Redesign: Use these insights to explore alternatives (e.g., greener solvents, shorter run times, column heating optimization) and recalculate the metric to guide decision-making [10].

Key Research Reagent Solutions for Green Chemistry

Table 2: Essential Materials for Sustainable Analytical Chemistry

| Material / Tool | Function in Green Analytical Chemistry | Example & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Green Solvents | Replace hazardous traditional solvents (e.g., acetonitrile, n-hexane) in extraction and chromatography [5]. | Switchable Solvents (SSs), Ionic Liquids (ILs), Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES), and Supercritical Fluids (e.g., CO₂ for SFE) offer reduced toxicity and volatility [5]. |

| Advanced Materials | Enhance extraction efficiency and selectivity, enabling miniaturization and reducing solvent demand [5]. | Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs), Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs), and Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) are used in sorptive extraction techniques like μ-dSPE and SPME [5]. |

| Miniaturized Systems | Dramatically reduce sample size and consumption of solvents and reagents [4] [5]. | Microextraction by Packed Sorbent (MEPS), Thin Film Microextraction (TFME), and lab-on-a-chip Microelectromechanical Systems (MEMS) [5]. |

| Greenness Assessment Tools | Provide a standardized, quantitative measure of an analytical method's environmental performance [10]. | Analytical Method Greenness Score (AMGS), AGREEprep, Analytical Eco-Scale. These tools help benchmark methods and guide sustainable development choices [4] [10]. |

Data Presentation and Analysis

Structuring quantitative data is essential for comparing methods and tracking improvements.

Greenness Metrics and LCA Impact Data

Table 3: Exemplary LCA and Greenness Data for HPLC Methods

| Method Parameter | Traditional HPLC | Optimized Green HPLC | Improvement Rationale & Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mobile Phase | Acetonitrile (100%) | Ethanol (80%) / Water (20%) | Switching to a less toxic, bio-derived solvent reduces EHS impact [5] [10]. |

| Flow Rate | 1.5 mL/min | 0.5 mL/min | Reducing flow rate directly cuts solvent consumption and waste generation by 66% per analysis [10]. |

| Column Temp. | 40°C | 50°C (with shorter column) | Increased temperature can improve efficiency, allowing for a shorter column and faster run times, saving energy and solvent [10]. |

| Run Time | 20 minutes | 8 minutes | A 60% reduction in run time proportionally reduces energy consumption and increases laboratory throughput [10]. |

| AMGS Score | 45 (Less Green) | 78 (More Green) | The AMGS tool quantitatively demonstrates the overall environmental improvement across multiple parameters [10]. |

| Carbon Footprint (per run) | 2.1 kg CO₂-eq | 0.8 kg CO₂-eq | LCA results show a ~62% reduction in GHG emissions, contributing to Scope 1 & 2 GHG inventory reduction [27]. |

Integrating Life Cycle Assessment and Greenhouse Gas Inventories provides a powerful, holistic framework for quantifying and mitigating the environmental impact of analytical methods. By adopting the standardized protocols and metrics outlined in this document—such as the Analytical Method Greenness Score (AMGS)—researchers and drug development professionals can make informed decisions that align analytical performance with the urgent need for environmental sustainability. This systematic approach is no longer a niche consideration but a fundamental component of modern, responsible scientific practice.

Implementing Green Strategies: Solvents, Sample Preparation, and Instrumentation for Pharmaceutical Analysis

The transition from traditional organic solvents to green alternatives represents a critical strategic pillar in modern analytical method development, particularly within the pharmaceutical industry. This shift is driven by an urgent need to align scientific practice with the principles of environmental sustainability, operational safety, and economic efficiency. Traditional solvent-intensive techniques contribute significantly to environmental degradation and occupational hazards due to their volatility, toxicity, and persistence [30] [31]. The analytical chemistry community is increasingly adopting frameworks like Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) and the emerging concept of White Analytical Chemistry (WAC), which balances environmental impact with analytical performance and practical utility [19].

The business case for this transition is strengthened by stringent global regulations restricting hazardous solvents and growing consumer demand for sustainable manufacturing practices. With the green solvents market projected to surpass $5.5 billion by 2035, expanding at a compound annual growth rate of 8.7%, these alternatives are transitioning from niche options to mainstream necessities [32]. This application note provides a structured framework for selecting and implementing green solvents, specifically ethanol, water, and bio-based alternatives, within analytical methods for drug development, complete with practical protocols and quantitative assessment tools.

Green Solvent Profiles: Properties, Advantages, and Applications

Comprehensive Characterization of Leading Green Solvents

Water As a universal solvent with high polarity, water offers unparalleled advantages in safety, cost, and availability. Its applicability is expanded through techniques such as subcritical water extraction, where temperature and pressure manipulation modulate polarity to extract a wider range of analytes. Modern approaches like aqueous biphasic systems significantly enhance its extraction capabilities for hydrophobic compounds, making it far more versatile than traditional applications suggest [30] [31].

Bio-based Ethanol Derived primarily from sugarcane or corn via fermentation, bio-based ethanol represents a renewable, biodegradable alternative to petroleum-derived alcohols. With low toxicity and favorable environmental credentials, it serves as an effective replacement for methanol or acetonitrile in chromatographic methods and for solvents like hexanes in extraction processes. Its well-established supply chain and moderate boiling point facilitate easy recycling and recovery [30] [33].

Ethyl Lactate This bio-based solvent, derived from lactic acid, boasts an excellent safety profile as it is biodegradable, non-carcinogenic, and non-ozone depleting. With high solvency power for resins, polymers, and oils, it demonstrates particular effectiveness in extraction processes where it can replace halogenated solvents. Its classification as Generally Recognized As Safe (GRAS) by the FDA makes it especially valuable for food and pharmaceutical applications [30] [31].

d-Limonene Sourced from citrus fruit peels, d-Limonene exemplifies circular economy principles in solvent selection. This renewable solvent effectively replaces petroleum-derived hydrocarbons like n-hexane in degreasing and cleaning applications. Although its distinctive odor requires consideration in ventilation design, its low toxicity and renewable origin make it a environmentally preferable option [33] [34].

2-Methyltetrahydrofuran (2-MeTHF) Derived from biomass like corn cobs or bagasse, 2-MeTHF offers a greener alternative to tetrahydrofuran (THF) with superior stability against peroxidation and lower miscibility with water that facilitates aqueous-organic separations. Its favorable environmental profile and improving commercial availability position it as a sustainable choice for various synthetic and extraction applications [34].

Quantitative Comparison: Green Solvents vs. Traditional Alternatives

Table 1: Property Comparison of Green and Traditional Solvents

| Solvent | Source | Boiling Point (°C) | Vapor Pressure | Log P | Greenness Score (CHEM21) | Common Traditional Replacements |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water | Inorganic | 100 | 23.8 mmHg at 25°C | -1.38 | Recommended | N/A (Benchmark) |

| Ethanol | Sugarcane/Corn | 78 | 59 mmHg at 25°C | -0.18 | Recommended | Methanol, Acetonitrile |

| Ethyl Lactate | Corn/Beets | 154 | 1.9 mmHg at 25°C | 0.72 | Recommended | DCM, Chloroform, DMF |

| d-Limonene | Citrus Peel | 176 | 1.5 mmHg at 25°C | 4.57 | Problematic* | n-Hexane, Toluene |

| 2-MeTHF | Corn Cobs/Bagasse | 80 | 144 mmHg at 25°C | 0.83 | Recommended | THF, Diethyl Ether |

| DCM | Petroleum | 39.6 | 440 mmHg at 25°C | 1.25 | Highly Hazardous | Benchmark for replacement |

| Acetonitrile | Petroleum | 81.6 | 97 mmHg at 25°C | -0.34 | Hazardous | Benchmark for replacement |

Note: d-Limonene's "Problematic" classification primarily relates to potential aquatic toxicity; it remains preferred over the "Hazardous" traditional solvents it replaces. Greenness scores based on CHEM21 Solvent Selection Guide [34].

Strategic Implementation Framework and Experimental Protocols

Systematic Solvent Selection Methodology

Implementing a systematic approach to green solvent selection ensures optimal outcomes that balance environmental benefits with analytical performance. The following workflow provides a structured decision-making process:

The initial assessment phase requires thorough understanding of analyte solubility, matrix composition, and methodological requirements. Consultation of updated miscibility data for green solvents is essential, as traditional tables often lack these newer alternatives [34]. The sustainability evaluation should incorporate multi-dimensional assessment tools like the Analytical Method Greenness Score (AMGS) or the CHEM21 guide, which evaluate safety, health, and environmental impacts [34] [10]. For a comprehensive sustainability perspective, the emerging White Analytical Chemistry (WAC) framework incorporates the RGB model (red for analytical performance, green for environmental impact, blue for economic practicality) to ensure balanced method development [19].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Green Switch for HPLC Mobile Phase

Objective: Replace acetonitrile or methanol with bio-ethanol in reverse-phase HPLC analysis while maintaining chromatographic performance.

Materials:

- HPLC system with UV/VIS or PDA detector

- C18 or similar reverse-phase column (e.g., 150 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm)

- Bio-ethanol (HPLC grade)

- Pharmaceutical active ingredient (e.g., paracetamol) and related impurities

- Traditional mobile phase: Acetonitrile/water vs. Green mobile phase: Ethanol/water

Procedure:

- Method Scouting: Prepare initial ethanol-water mixtures varying from 20:80 to 50:50 (v/v) to identify the optimal ratio that provides comparable retention factors to the traditional method.

- pH Optimization: Adjust pH using 0.1% phosphoric acid or ammonium acetate buffer (10-50 mM) as needed. Note that ethanol exhibits higher viscosity than acetonitrile, which may increase backpressure.

- System Compatibility: Ensure HPLC pump seals and tubing are compatible with ethanol. Modern systems typically tolerate up to 100% ethanol, but consult manufacturer specifications.

- Gradient Adjustment: When converting from acetonitrile to ethanol, adjust gradient programs to account for the different elution strength. As a starting point, increase ethanol concentration by approximately 10-15% relative to acetonitrile percentages.

- Performance Validation: Inject system suitability standards and calculate key parameters (resolution, tailing factor, plate count) to confirm performance equivalence. For the paracetamol method, target resolution >2.0 between critical pairs.

Assessment: Calculate the Analytical Method Greenness Score (AMGS) for both methods. The ethanol-based method typically demonstrates a 30-50% improvement in environmental impact scores while reducing solvent procurement costs by 20-40% compared to acetonitrile [10].

Protocol 2: NADES-Based Extraction of Natural Products

Objective: Develop a natural deep eutectic solvent (NADES) for the extraction of polar analytes from plant material, replacing conventional solvents like methanol or acetone.

Materials:

- Plant material (e.g., dried and powdered rosemary leaves)

- Choline chloride

- Glycerol (USP grade)

- Lactic acid (USP grade)

- Distilled water

- Ultrasonic bath or vortex mixer

Procedure:

- NADES Preparation: Combine choline chloride and glycerol in a 1:2 molar ratio in a sealed container. Heat at 60°C with continuous stirring (300-500 rpm) until a homogeneous, clear liquid forms (typically 30-60 minutes). Alternatively, combine choline chloride with lactic acid (1:3 molar ratio) for more polar applications.

- Extraction Process: Weigh 100 mg of dried plant material into a 15 mL centrifuge tube. Add 5 mL of the prepared NADES.

- Extraction Assistance: Employ one of the following assistance mechanisms:

- Vortex-Assisted Extraction: Vortex vigorously for 5 minutes at maximum speed.

- Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction: Sonicate for 10 minutes at 35°C.

- Heating-Assisted Extraction: Place in a heating block at 50°C for 20 minutes with occasional shaking.

- Separation: Centrifuge at 5000 rpm for 10 minutes to separate the extract from plant debris.

- Analysis: Dilute the supernatant with an equal volume of water or ethanol for HPLC analysis. For rosemary antioxidants, a C18 column with ethanol/water mobile phase is suitable.

Assessment: Compare extraction efficiency against conventional methanolic extraction using HPLC quantification of target compounds (e.g., rosmarinic acid, carnosic acid). NADES typically achieves equivalent or superior recovery of polar compounds while eliminating volatile organic compound emissions and reducing workplace exposure hazards [30].

Assessment Methodologies and Validation Framework

Quantitative Greenness Evaluation Tools

Implementing robust assessment methodologies is essential for validating the environmental benefits of green solvent adoption. The following tools provide standardized approaches:

Table 2: Greenness Assessment Tools for Analytical Methods

| Tool Name | Application Scope | Output Format | Key Metrics Assessed | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMGS (Analytical Method Greenness Score) | Chromatographic methods | Numerical score (0-10) | Solvent energy, EHS, instrument energy consumption | HPLC-specific, holistic life cycle view |

| AGREE (Analytical GREEnness) | General analytical methods | Circular pictogram with 0-1 score | 12 GAC principles including waste, toxicity, energy | Comprehensive, visual, easy interpretation |

| GAPI (Green Analytical Procedure Index) | Sample preparation & analysis | Multi-colored pentagram | 5 stages of analytical process from sampling to waste | Detailed step-by-step assessment |

| ComplexGAPI | Advanced method assessment | Extended GAPI diagram | Includes additional sustainability dimensions | Holistic WAC assessment framework |