SIGNIFICANCE Mnemonic: A Practical Guide to the 12 Principles of Green Analytical Chemistry for Pharmaceutical Professionals

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the SIGNIFICANCE mnemonic and its corresponding 12 principles of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC), tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

SIGNIFICANCE Mnemonic: A Practical Guide to the 12 Principles of Green Analytical Chemistry for Pharmaceutical Professionals

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the SIGNIFICANCE mnemonic and its corresponding 12 principles of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC), tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It establishes the foundational framework of GAC, moving into methodological applications for greening sample preparation and analysis. The guide addresses common troubleshooting challenges and introduces optimization strategies for balancing sustainability with analytical performance. Finally, it details the validation of green methods using modern metrics like AGREE, GAPI, and NEMI, and positions GAC within the broader context of White Analytical Chemistry and global sustainability goals, offering a complete roadmap for implementing sustainable practices in pharmaceutical analysis.

Foundations of Green Analytical Chemistry: Understanding the SIGNIFICANCE Mnemonic and Core Principles

Analytical chemistry plays a crucial role in determining the composition and quantity of matter, yet its traditional practices raise significant environmental concerns due to reliance on energy-intensive processes, non-renewable resources, and substantial waste generation [1]. The pharmaceutical industry exemplifies this challenge, with carbon emissions estimated to be up to 55% higher than the automotive sector and E-Factor values (ratio of waste to product) ranging from 25 to over 100 [2]. This translates to over 100 kilograms of waste generated for every kilogram of active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) produced. Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) has emerged as a transformative discipline that addresses these issues by integrating the principles of green chemistry into analytical methodologies [3]. GAC represents a fundamental shift from managing pollution after its creation to preventing it at the molecular level, optimizing analytical processes to ensure they are safe, nontoxic, environmentally friendly, and efficient in their use of materials, energy, and waste generation [4]. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical guide to GAC principles, metrics, and methodologies, framing them within the SIGNIFICANCE mnemonic and exploring their critical role in advancing sustainable science, particularly for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

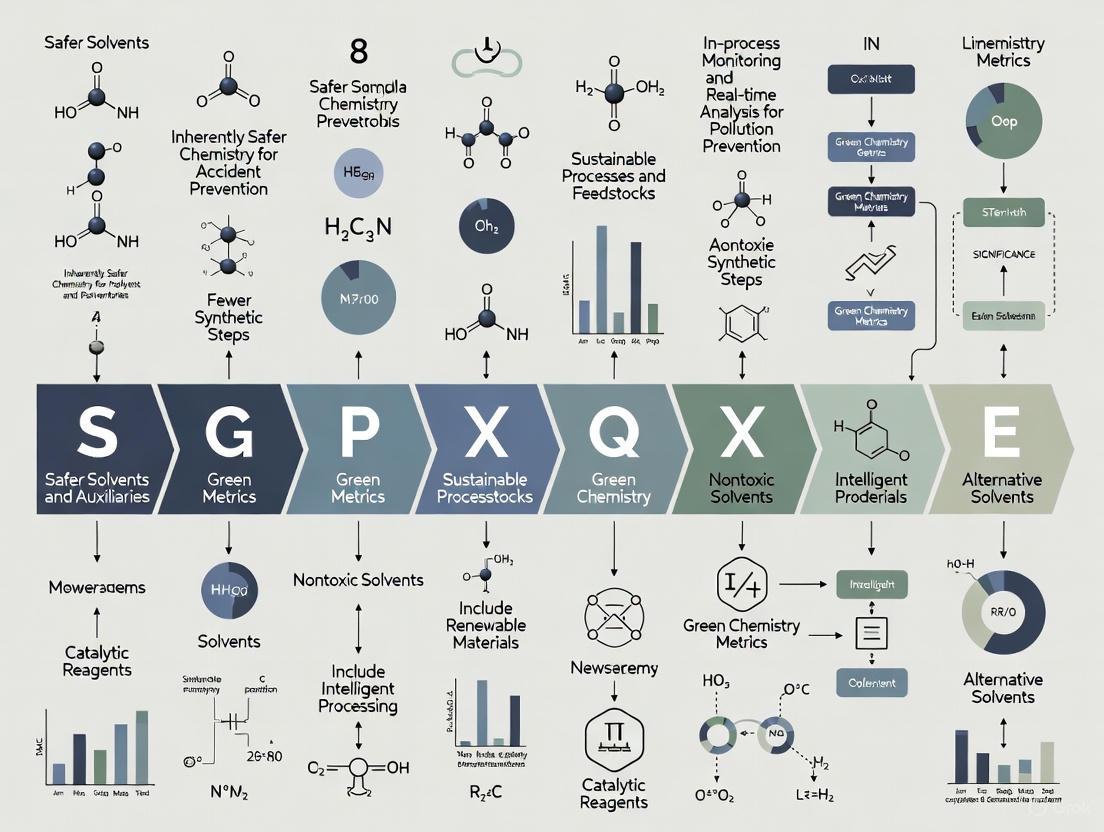

Foundational Principles: The SIGNIFICANCE Mnemonic of GAC

The 12 principles of Green Analytical Chemistry provide a comprehensive framework for designing and implementing environmentally benign analytical techniques [5] [3]. These principles can be remembered through the mnemonic SIGNIFICANCE, which serves as an essential guide for laboratories aiming to implement sustainable practices [5] [6]:

- Select direct analytical techniques that avoid sample preparation

- Integrate analytical processes and operations for streamlined workflows

- Generate as little waste as possible and properly manage any produced

- No derivatization; avoid chemical reactions for analysis when possible

- Incorporate automation and miniaturization to enhance efficiency

- Fast responses through method optimization for reduced analysis time

- Increase safety for the operator through reduced toxicity

- Choose multi-analyte methods to maximize information per analysis

- Avoid excessive energy consumption through energy-efficient equipment

- No additional sample processing; implement direct measurements

- Consume minimal sample volumes through miniaturized approaches

- Eliminate toxic reagents or replace them with safer alternatives

These principles emphasize waste prevention, atom economy, less hazardous chemical syntheses, and designing safer chemicals while prioritizing energy efficiency and real-time analysis for pollution prevention [3] [2]. The foundational philosophy is proactive prevention rather than retrospective treatment of waste and hazards [2].

Quantitative Assessment: GAC Metrics and Evaluation Tools

Proper GAC tools are essential for objectively assessing the greenness of analytical methods, with multiple metrics developed to quantify environmental performance [7].

Table 1: Key Metrics for Assessing Greenness in Analytical Chemistry

| Metric Name | Evaluation Approach | Key Parameters Assessed | Output Format |

|---|---|---|---|

| NEMI (National Environmental Methods Index) | Pictogram with four quadrants | PBT chemicals, hazardous waste, corrosivity, waste amount | Simple pass/fail pictogram |

| Analytical Eco-Scale | Penalty point system | Reagent toxicity, waste, energy consumption | Numerical score (100 = ideal) |

| GAPI (Green Analytical Procedure Index) | Color-coded pictogram | Entire method lifecycle from reagent to waste | Multi-colored pictogram |

| AGREE (Analytical GREEnness) | Software-based calculation | All 12 GAC principles simultaneously | Circular pictogram with score |

| ComplexGAPI | Advanced GAPI extension | Holistic assessment of complex procedures | Detailed multi-stage pictogram |

The Analytical Eco-Scale assigns a total score of 100 points for an ideal green analysis, with penalty points subtracted based on amounts of solvents/reagents, energy consumption, hazards, and waste produced [7]. To be considered an "ideal green analysis," a method must use solvents/reagents with no health, environmental, or physical hazards; consume less than 0.1 kWh per sample; and produce no waste [7]. The AGREE metric provides a comprehensive evaluation using all 12 GAC principles, generating a score from 0-1 where 1 represents perfect greenness [4]. Good Evaluation Practice (GEP) recommends using quantitative indicators based on empirical data alongside assessment models to ensure comprehensive and reliable evaluations [8]. Key empirical indicators include the amount of electricity required for specific analysis counts (measured with a wattmeter), carbon footprint calculations, total mass/volume of waste generated, and mass of hazardous reagents used [8].

Advanced Framework: White Analytical Chemistry (WAC)

White Analytical Chemistry (WAC) represents the next evolution of sustainable analytical chemistry, strengthening traditional GAC by adding criteria for assessing analytical performance and practical usability [5]. WAC follows a holistic framework that integrates all three critical aspects of analytical methods using a color-coded model inspired by the Red-Green-Blue (RGB) color system [5]:

- Red Component: Represents analytical performance, focusing on attributes such as accuracy, precision, sensitivity, selectivity, and linearity

- Green Component: Incorporates traditional GAC metrics addressing environmental impact, safety, and waste generation

- Blue Component: Considers practical and economic aspects including method cost, time of analysis, availability of equipment, and ease of use

Under the WAC framework, the ideal "white" method achieves the optimal balance among all three components, ensuring environmental sustainability without compromising analytical quality or practical applicability [5]. This balanced position makes WAC particularly valuable for pharmaceutical quality control settings, where it enables informed decision-making when evaluating analytical method development or modification [5]. For example, replacing an existing HPLC method consuming high volumes of acetonitrile with a greener alternative would be evaluated not just for solvent reduction (green), but also for maintained analytical performance (red) and cost-effectiveness/throughput (blue) [5].

Diagram 1: WAC Framework Balancing Three Critical Components

Green Methodologies: Practical Applications and Protocols

Green Sample Preparation Techniques

Sample preparation is often the most polluting stage in analytical methods, making it a primary target for green improvements [6]. Key green sample preparation approaches include:

Solid Phase Microextraction (SPME): A solvent-free technique that combines extraction and enrichment using a silica fiber coated with an appropriate adsorbent phase [6]. The method involves exposing the fiber to the sample matrix (either through direct immersion or headspace), allowing analytes to partition into the coating, then thermally desorbing or eluting them into analytical instruments [6].

QuEChERS (Quick, Easy, Cheap, Effective, Rugged, and Safe): A two-stage method featuring solvent extraction with acetonitrile followed by dispersive solid-phase extraction for cleanup [6]. The protocol involves vigorously shaking the sample with buffer salts and magnesium sulfate, then using primary secondary amine (PSA) sorbent to remove matrix interferences, significantly reducing solvent consumption compared to traditional extraction methods [6].

Direct Chromatographic Methods: Eliminating sample preparation entirely through direct injection approaches [6]. Modern cross-linked stationary phases with improved resistance to water enable direct injection of aqueous samples, though pre-columns may be necessary to protect analytical columns from non-volatile residues [6].

Green Analytical Techniques and Instrumentation

Several analytical techniques have been developed or modified to align with GAC principles:

Miniaturized and Portable Devices: Reduced scale instrumentation that decreases solvent consumption, waste generation, and energy requirements while maintaining analytical performance [3]. Examples include miniature mass spectrometers for rapid on-site analysis of environmental samples and pharmaceutical compounds [9].

High-Performance Thin-Layer Chromatography (HPTLC): A favorable green alternative to HPLC with significantly lower solvent consumption and faster analysis times [5] [6]. In a case study comparing methods for thiocolchicoside and aceclofenac, HPTLC was preferred over HPLC due to its lower environmental impact despite HPLC's superior sensitivity and selectivity [5].

Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (UHPLC): Provides improved efficiency over conventional HPLC with smaller particle size columns, enabling faster separations, reduced mobile phase consumption, and decreased waste generation [6].

Table 2: Comparison of Traditional vs. Green Analytical Techniques

| Analytical Aspect | Traditional Approach | Green Alternative | Environmental Benefit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Preparation | Liquid-liquid extraction with large solvent volumes | Solid Phase Microextraction (SPME) | Eliminates solvent use entirely |

| Chromatography | Conventional HPLC with 4.6mm ID columns | UHPLC with 2.1mm ID columns | Redizes solvent consumption by ~80% |

| Solvent Selection | Acetonitrile, methanol, halogenated solvents | Ethanol, ethyl acetate, water | Lower toxicity and better biodegradability |

| Method Duration | 30-60 minute runs | 5-10 minute fast chromatography | Reduced energy consumption per sample |

| Sample Throughput | Sequential processing | Parallel sample treatment | Lower energy consumption per sample |

Experimental Protocol: Green RP-HPLC Method for Pharmaceutical Analysis

A validated green RP-HPLC method for the analysis of Olmesartan medoxomil demonstrates practical application of GAC principles [10]:

Materials and Equipment:

- HPLC system with UV detection

- Lichrosphere 250 × 4.0 mm RP C8 column (5μm packing)

- Ethyl acetate and ethanol (HPLC grade)

- Ultrasonic bath for mobile phase degassing

Mobile Phase Preparation:

- Prepare mixture of ethyl acetate:ethanol (50:50% v/v)

- Filter through 0.45μm membrane filter

- Degas using ultrasonic bath for 10 minutes

Chromatographic Conditions:

- Flow rate: 1.0 mL/min

- Detection wavelength: 250 nm

- Injection volume: 20 μL

- Temperature: Ambient (25°C)

Sample Preparation:

- For bulk drug: Dissolve in mobile phase to obtain 1 mg/mL solution

- For formulations: Extract powdered tablets in mobile phase with sonication

- Filter through 0.45μm syringe filter before injection

Method Validation:

- Linearity: 5-50 μg/mL (r² > 0.999)

- Precision: %RSD < 2% for repeatability and intermediate precision

- Accuracy: 98-102% recovery across concentration range

- Specificity: No interference from excipients or degradation products

This method successfully replaces traditional toxic solvents like acetonitrile and methanol with a greener combination of ethyl acetate and ethanol while maintaining analytical performance [10]. The method was applied to the analysis of olmesartan medoxomil in bulk drugs, self-microemulsifying drug delivery systems (SMEDDS), and commercial tablets with excellent results [10].

Implementation Strategies: GAC in Research and Industry

Green Solvents and Reagents

The transition to greener solvents represents one of the most significant opportunities for improving analytical sustainability. Water, supercritical carbon dioxide, ionic liquids, and bio-based solvents serve as alternatives to volatile organic compounds (VOCs), reducing toxicity and environmental impact [3]. Ethanol and ethyl acetate, as used in the olmesartan medoxomil method, exemplify this approach by providing effective chromatographic performance with improved safety profiles [10].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Green Analytical Chemistry

| Reagent Category | Traditional Materials | Green Alternatives | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extraction Solvents | Dichloromethane, chloroform, hexane | Ethyl acetate, ethanol, water | Sample preparation and compound extraction |

| Chromatographic Mobile Phases | Acetonitrile, methanol with buffers | Ethanol-water, supercritical CO₂ | Compound separation in chromatography |

| Sorbents | Synthetic polymers, silica gel | Biochar, primary secondary amine (PSA) | Selective adsorption in sample cleanup |

| Derivatization Agents | Toxic fluorophores, hazardous catalysts | Natural deep eutectic solvents (NADES) | Enhancing detection of target compounds |

| Calibration Standards | Pure analytical standards in toxic solvents | In-situ generated standards | Instrument calibration and quantification |

Energy-Efficient Techniques

Energy consumption represents another critical focus area for GAC implementation. Microwave-assisted and ultrasound-assisted methods enhance extraction efficiency and speed up mass transfer while consuming significantly less energy compared to traditional heating methods like Soxhlet extraction [1]. These approaches can be applied to miniaturized sample preparation systems that additionally minimize sample size, solvent, and reagent consumption [1].

Automation and Integration

Automated systems align perfectly with GAC principles by saving time, lowering consumption of reagents and solvents, reducing waste generation, and minimizing human intervention [1]. Integration of multiple preparation steps into a single, continuous workflow simplifies operations while cutting down on resource use and waste production [1]. For instance, multidimensional gas chromatography using nitrogen and hydrogen as carrier gases instead of helium demonstrates how method integration with greener materials enhances sustainability [9].

Future Perspectives: Challenges and Opportunities

Despite significant advances, GAC implementation faces several challenges. Analytical chemistry largely operates under a weak sustainability model, assuming that natural resources can be consumed and waste generated as long as technological progress and economic growth compensate for the environmental damage [1]. Transitioning to strong sustainability would require acknowledging ecological limits and prioritizing practices that restore natural capital [1]. The rebound effect presents another challenge, where efficiency gains lead to increased consumption – for example, a novel low-cost microextraction method might prompt laboratories to perform significantly more extractions, offsetting environmental benefits [1].

Coordination failure within the field also hinders progress, as circular analytical chemistry relies on collaboration among manufacturers, researchers, companies, routine labs, and policymakers [1]. Limited cooperation between industry and academia makes transitioning to circular processes challenging [1]. Additionally, regulatory agencies face the difficult task of phasing out outdated methods in favor of greener alternatives, with one study revealing that 67% of standard methods scored below 0.2 on the AGREEprep scale (where 1 represents maximum greenness) [1].

Future innovations will likely focus on emerging technologies like artificial intelligence and digital tools to optimize workflows, minimize waste, and streamline analytical processes [3]. The proposed Green Financing for Analytical Chemistry (GFAC) model aims to bridge implementation gaps by creating dedicated funds to finance innovation in sustainable analytical chemistry [5]. As environmental regulations tighten and industries shift toward greener practices, GAC principles will become increasingly essential for developing methods that are not only efficient but also environmentally responsible [4].

Diagram 2: GAC Method Development Workflow

Green Analytical Chemistry represents a fundamental shift in how chemical analysis is conducted, emphasizing environmental stewardship, sustainability, and efficiency alongside analytical performance. The SIGNIFICANCE mnemonic provides a practical framework for implementing GAC principles, while evolving metrics and assessment tools enable quantitative evaluation of methodological greenness. The emerging White Analytical Chemistry framework further strengthens this approach by balancing environmental sustainability with analytical performance and practical feasibility. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, adopting GAC principles offers a pathway to reduce environmental impact while maintaining analytical quality and often improving economic efficiency. As the field continues to evolve, GAC will play an increasingly vital role in aligning analytical chemistry with global sustainability goals and addressing the complex environmental challenges of the 21st century.

The Evolution from Green Chemistry to the 12 Principles of GAC

The emergence of green chemistry in the 1990s represented a transformative shift in chemical philosophy, moving from pollution remediation to pollution prevention. This fundamental reorientation was formally codified in 1998 when Paul Anastas and John Warner introduced the 12 Principles of Green Chemistry in their seminal work Green Chemistry: Theory and Practice [11] [12]. These principles established a comprehensive framework for designing chemical products and processes that reduce or eliminate the use and generation of hazardous substances [13]. The historical context for this development traces back to growing environmental concerns highlighted by Rachel Carson's Silent Spring in 1962 and the establishment of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 1970 [12]. The Pollution Prevention Act of 1990 further cemented the philosophical foundation by establishing a national policy that pollution should be prevented or reduced at source whenever feasible [13].

The evolution from these foundational principles to quantitative assessment tools represents the next critical phase in sustainable chemistry. The development of the DOZN 3.0 quantitative green chemistry evaluator exemplifies this progression, providing researchers with a systematic methodology for comparing the relative greenness of chemicals, synthetic routes, and processes [14] [15]. This tool distills the 12 principles into three actionable categories: improving resource use, enabling more efficient energy use, and minimizing human and environmental hazards [15]. For drug development professionals and researchers, this evolution from conceptual frameworks to measurable metrics marks a significant advancement in implementing and validating sustainable chemistry practices within complex research and development pipelines.

The Foundation: Understanding the 12 Principles of Green Chemistry

The 12 Principles of Green Chemistry provide a systematic framework for designing chemical syntheses that are efficient, safe, and environmentally compatible. These principles serve as the foundational bedrock upon which modern green analytical chemistry (GAC) has been built, offering strategic guidance for researchers and industrial chemists alike. The principles encompass all stages of chemical design, manufacture, use, and disposal, applying across the entire life cycle of chemical products [13].

Table 1: The 12 Principles of Green Chemistry and Their Research Significance

| Principle Number | Principle Name | Core Concept | Significance for Researchers |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Prevention | Preventing waste generation is superior to treating or cleaning up waste after it is formed [13] [11]. | Reduces environmental impact and disposal costs; measured via E-factor and Process Mass Intensity (PMI) [16]. |

| 2 | Atom Economy | Synthetic methods should maximize incorporation of all starting materials into the final product [13] [11]. | Promotes synthetic efficiency; calculated as (FW of desired product / Σ FW of all reactants) × 100 [16]. |

| 3 | Less Hazardous Chemical Syntheses | Synthetic methods should use/generate substances with minimal toxicity to humans and the environment [13] [11]. | Enhances laboratory safety and reduces environmental footprint; encourages solvent/substitution guides [17]. |

| 4 | Designing Safer Chemicals | Chemical products should be designed to achieve desired function while minimizing toxicity [13] [11]. | Balances molecular efficacy with reduced biological and environmental hazards [17]. |

| 5 | Safer Solvents and Auxiliaries | Minimize use of auxiliary substances; use safer alternatives when required [13] [11]. | Reduces exposure to hazardous solvents; guides selection of greener alternatives like ethyl acetate or 2-MeTHF [17]. |

| 6 | Design for Energy Efficiency | Recognize and minimize energy requirements of chemical processes [13] [11]. | Lowers operational costs and environmental impact; favors ambient temperature and pressure [16]. |

| 7 | Use of Renewable Feedstocks | Use renewable raw materials rather than depletable feedstocks [13] [11]. | Enhances sustainability; utilizes biomass instead of fossil fuels [13]. |

| 8 | Reduce Derivatives | Avoid unnecessary derivatization (blocking groups, protection/deprotection) [13] [11]. | Simplifies synthesis, reduces steps, reagents, and waste; enzymatic methods can help [18]. |

| 9 | Catalysis | Catalytic reagents (selective as possible) are superior to stoichiometric reagents [13] [11]. | Increases efficiency; catalysts are effective in small amounts and carry out multiple reaction cycles [13]. |

| 10 | Design for Degradation | Design chemical products to break down into innocuous substances after use [13] [11]. | Prevents environmental persistence and bioaccumulation of chemicals [18]. |

| 11 | Real-time Analysis for Pollution Prevention | Develop analytical methodologies for real-time, in-process monitoring [13] [11]. | Allows for immediate process control to prevent hazardous substance formation [11]. |

| 12 | Inherently Safer Chemistry for Accident Prevention | Choose substances and their physical forms to minimize accident potential [13] [11]. | Mitigates risks of explosions, fires, and environmental releases through fundamental design [11]. |

The principles are deeply interconnected, creating a synergistic system for sustainable chemical design. For instance, atom economy (Principle 2) directly supports waste prevention (Principle 1), as reactions that incorporate more starting atoms into the final product inherently generate less waste [16] [17]. Similarly, the use of catalysis (Principle 9) frequently enables reduced derivatives (Principle 8) and enhances energy efficiency (Principle 6) by allowing reactions to proceed under milder conditions [18]. For pharmaceutical researchers, these principles provide a proactive framework for designing synthetic routes that are not only environmentally responsible but also more cost-effective and efficient, ultimately supporting the development of safer therapeutics with reduced environmental impact throughout their lifecycle.

Quantitative Evolution: From Principles to Practical Metrics

The transition from qualitative principles to quantitative assessment frameworks marks a critical evolution in green chemistry, enabling researchers to make objective comparisons and measure improvements. Several key metrics have been developed to translate the 12 principles into actionable data, providing the scientific community with standardized tools for evaluation.

Table 2: Core Quantitative Metrics for Green Chemistry Assessment

| Metric Name | Calculation Formula | Application | Ideal Value | Industry Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E-Factor [16] | e-factor = mass of waste (kg) / mass of product (kg) |

Measures waste generation efficiency of a process. | Lower is better; Oil refining: <0.1 [16] | Pharmaceutical API processes historically had E-factors of 25-100+ [16] |

| Process Mass Intensity (PMI) [16] | PMI = total process mass (kg) / mass of product (kg) |

Broader assessment of all materials used, including solvents, water. | Lower is better; Minimum = 1 [16] | Adopted by ACS Green Chemistry Institute Pharmaceutical Roundtable for API processes [17] |

| Atom Economy [16] | Atom Economy (%) = (FW of desired product / Σ FW of reactants) × 100 |

Theoretical efficiency of a reaction in incorporating starting atoms into the product. | Higher is better; Maximum = 100% [16] | Diels-Alder cycloaddition: ~100% atom economy [12] |

| EcoScale [16] | Score based on penalty points for yield, cost, safety, technical setup, temperature/time, workup. | Comprehensive metric that includes practical, safety, and economic factors. | Higher is better; Maximum = 100 [16] | Used for comparing synthetic route optimization in research [16] |

The DOZN 3.0 tool, developed by Merck, represents a significant advancement in quantitative green chemistry evaluation [14]. This web-based tool utilizes the 12 principles as a foundation but organizes them into three overarching categories: improving resource use, energy efficiency, and reducing human and environmental hazards [15]. DOZN generates a comparative score that enables researchers and drug development professionals to objectively evaluate the relative greenness of alternative synthetic routes or similar chemicals. A compelling case study demonstrated the power of this quantitative assessment: the re-engineering of a β-Amylase manufacturing process resulted in the DOZN score being lowered from 57 to 1, indicating a dramatic improvement in greenness while simultaneously enhancing yield and efficiency [15].

Beyond these established metrics, research continues to develop more comprehensive assessment techniques. One study proposed a quantitative "greenness" evaluation incorporating environmental, safety, resource, and economic indices [19]. This approach calculates a composite greenness score using the formula: Greenness = α·Σenvironment + β·Σsafety + γ·Σresource (+ δ·Σeconomy) where α, β, γ, and δ are weights derived from expert analysis [19]. Such methodologies enable a more nuanced evaluation of green chemistry technologies, considering factors like greenhouse gas emissions, hazardous substance impacts, and industrial accident potential alongside traditional efficiency metrics.

Advanced Quantitative Assessment Framework

For research scientists requiring rigorous assessment protocols, the comprehensive greenness evaluation methodology provides a detailed framework for quantifying improvements in chemical processes. This methodology employs specific experimental protocols and calculations across four key indices: environment, safety, resource, and economy [19].

Environmental Impact Assessment Protocol

The environmental impact assessment quantifies two primary factors: greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and hazardous substance impacts. The experimental protocol requires researchers to:

- Catalog all materials: Identify all raw materials, products, by-products, and emissions from the chemical process [19].

- Quantify GHG emissions: Calculate CO₂ equivalent emissions for all process steps using Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) methodologies, including energy consumption converted to tCO₂ [19].

- Evaluate hazardous substances: Calculate Health Hazard Factors (HHF) and Environmental Hazard Factors (EHF) for all process components using established reference scales:

- Composite Environmental Score: Calculate ΣEnvironment = αₐ·ΣGHGs + αբ·ΣHazardous substances, where weights are derived from Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) analysis [19].

Safety, Resource, and Economic Assessment

The safety assessment protocol involves quantifying the inherent hazards of all chemical substances involved in the production process (raw materials, products/by-products, and emissions) by evaluating their R-Phrases against a standardized reference scale [19]. The resulting safety factor is calculated as: ΣSafety = x₂·Σraw materials + y₂·Σproducts/by-products + z₂·Σemissions [19].

Resource assessment focuses on efficacious production by minimizing depleting resources. The protocol evaluates resource consumption improvement rates, with specific calculations for different material types:

- Organic compounds: Assessed via carbon efficiency

- Precious/rare metals: Evaluated based on content efficiency The resource improvement is calculated as: Resource = 1 - (consumption after improvement / consumption before improvement) [19].

Economic assessment, while not part of the original 12 principles, is recognized as essential for industry adoption. The protocol evaluates:

- Production cost reduction relative to baseline expenditures

- Consumer price reduction relative to baseline retail price The composite economic feasibility is calculated as a weighted average of these factors [19].

Case Study: Waste Acid Reutilization Assessment

A documented application of this comprehensive assessment examined the reutilization of waste acid from electronic parts pickling [19]. By installing cooling equipment to address excessive use of nitrogen chemicals, the process achieved a 42% enhancement in greenness compared to pre-improvement levels [19]. This case study demonstrates the practical utility of quantitative assessment in validating green chemistry technologies and guiding process optimization decisions.

Diagram 1: Evolution of Green Chemistry Assessment showing the progression from historical context through principles to quantitative tools.

Implementation in Pharmaceutical Research and Development

The pharmaceutical industry has emerged as a pioneering sector in implementing green chemistry principles, driven by both environmental responsibilities and compelling economic factors. The development of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) traditionally involved complex multi-step syntheses with high E-factors, often exceeding 100 kg of waste per kg of final product [16] [17]. The adoption of green chemistry metrics and principles has enabled significant advancements in sustainable drug development.

Experimental Protocol: Green Chemistry Assessment for API Synthesis

For drug development professionals implementing green chemistry evaluation, the following experimental protocol provides a systematic methodology:

Baseline Establishment:

Route Optimization:

- Apply Principle 2 (Atom Economy): Evaluate alternative synthetic pathways with higher inherent atom economy [17].

- Apply Principle 5 (Safer Solvents): Substitute hazardous solvents (e.g., dichloromethane, benzene) with safer alternatives (e.g., ethyl acetate, 2-methyltetrahydrofuran) using established solvent selection guides [17].

- Apply Principle 9 (Catalysis): Implement catalytic reactions to replace stoichiometric reagents, reduce steps, and improve selectivity [18].

Process Intensification:

- Apply Principle 8 (Reduce Derivatives): Minimize or eliminate protecting groups through strategic bond formation or enzymatic methods [18].

- Apply Principle 6 (Energy Efficiency): Optimize reaction conditions to operate at ambient temperature and pressure where feasible [16].

- Implement Principle 11 (Real-time Analysis): Incorporate process analytical technology (PAT) for in-line monitoring and control [11].

Comparative Assessment:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Green Chemistry in Pharmaceutical Development

| Reagent Category | Traditional Reagents | Green Alternatives | Function | Principle Addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solvents | Dichloromethane, Benzene, DMF | Ethyl acetate, 2-MeTHF, Cyrene, water [17] | Reaction medium, extraction | Principle 5: Safer Solvents |

| Catalysts | Stoichiometric reagents (AlCl₃, MnO₂) | Biocatalysts, heterogeneous catalysts, organocatalysts [18] | Accelerate reactions without being consumed | Principle 9: Catalysis |

| Oxidizing Agents | Chromium(VI) compounds, MnO₂ | Hydrogen peroxide, O₂ (molecular oxygen), biocatalytic oxidation [17] | Selective oxidation | Principle 3: Less Hazardous Synthesis |

| Reducing Agents | LiAlH₄, NaBH₄ with additives | Catalytic hydrogenation, biomimetic reductants [17] | Selective reduction | Principle 3: Less Hazardous Synthesis |

| Activating Agents | SOCl₂, COCl₂ (phosgene) | Solid acid catalysts, TCICA, polymer-supported reagents [17] | Functional group activation | Principle 4: Designing Safer Chemicals |

Case Studies: Pharmaceutical Green Chemistry Applications

Several landmark applications demonstrate the successful implementation of green chemistry principles in pharmaceutical development:

Simvastatin Synthesis (Codexis & UCLA): Developed a biocatalytic manufacturing process for simvastatin using an engineered acyltransferase, eliminating hazardous reagents and reducing solvent waste [17]. This approach addressed Principle 9 (Catalysis) and Principle 3 (Less Hazardous Chemical Syntheses).

Sertraline Manufacturing (Pfizer): Redesigned the synthesis of the active ingredient in Zoloft, optimizing the synthetic route to reduce from three separate manufacturing facilities to one, dramatically improving atom economy and eliminating hazardous reagents [17]. This achievement exemplified Principle 2 (Atom Economy) and Principle 1 (Waste Prevention).

β-Amylase Process Re-engineering: Utilizing the DOZN evaluator, researchers transformed the manufacturing process for this enzyme into an energy-efficient, non-hazardous operation with significantly greater efficiency and yield, achieving a dramatic reduction in DOZN score from 57 to 1 [15].

Diagram 2: GAC Principles Assessment Framework showing how principles translate to measurable metrics for research applications.

Future Directions and Integration with Broader Frameworks

The evolution of green chemistry continues to advance beyond the foundational 12 principles, integrating with broader sustainability frameworks and emerging technologies. A significant development is the growing connection between green chemistry and Responsible Research and Innovation (RRI), which addresses socio-ethical, economic, and political dimensions that were not explicitly covered in the original principles [20]. Recent studies have proposed integrated methodologies such as "responsible roadmapping" to help researchers develop interdisciplinary agendas that address both technical and socio-ethical considerations in chemical research and development [20].

The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning represents another frontier in green chemistry evolution. By the 2020s, AI-driven approaches began enabling researchers to rapidly identify and design new sustainable catalysts and reaction pathways, minimizing waste and energy consumption [12]. These computational tools can predict reaction outcomes, optimize process conditions, and even design biodegradable molecular structures, accelerating the implementation of green chemistry principles across research and development pipelines.

The principles of green chemistry are increasingly recognized as essential contributors to achieving Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and supporting the transition to a circular economy [20]. Green chemistry principles directly support several SDGs, including responsible consumption and production (SDG 12), climate action (SDG 13), and life below water (SDG 14) through the design of biodegradable chemicals and pollution prevention [12] [20]. As regulatory frameworks like the European Green Deal advance ambitions for climate neutrality by 2050, the principles of green chemistry provide fundamental guidance for transforming chemical production and consumption systems [12].

For drug development professionals and researchers, these evolving frameworks offer increasingly sophisticated tools for designing sustainable chemistry solutions. The ongoing integration of green chemistry with complementary approaches like RRI ensures that future innovations will address not only technical efficiency but also social responsibility and ethical implications, creating a more comprehensive foundation for sustainable scientific progress.

Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) has emerged as a transformative approach to mitigate the adverse environmental impacts of analytical activities while maintaining high-quality analytical results [5]. Evolving from the foundational Twelve Principles of Green Chemistry established by Anastas and Warner, GAC focuses on integrating sustainability directly into analytical research laboratories [5] [7]. The primary challenge of GAC lies in balancing the reduction of environmental impacts with the maintenance or improvement of analytical quality [7]. To effectively implement GAC principles in practice, the SIGNIFICANCE mnemonic was developed as a comprehensive framework for implementing sustainable and eco-friendly analytical practices [5]. This mnemonic serves as a practical roadmap for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to align their analytical methodologies with sustainability goals without compromising analytical performance.

The evolution of GAC has led to the development of more holistic frameworks, including White Analytical Chemistry (WAC), which expands GAC principles by incorporating analytical performance (red criteria) and practical/economic aspects (blue criteria) alongside environmental sustainability (green criteria) [5]. This RGB model represents the next iteration of sustainable analytical practices, ensuring methods are not only environmentally sound but also analytically robust and economically viable [5]. Within this context, understanding the SIGNIFICANCE mnemonic remains fundamental to implementing core GAC principles in pharmaceutical research and analytical method development.

Letter-by-Letter Deconstruction of the SIGNIFICANCE Mnemonic

The SIGNIFICANCE mnemonic provides a systematic approach to implementing Green Analytical Chemistry principles. Each letter represents a key consideration for developing environmentally sustainable analytical methods while maintaining scientific rigor. The following table presents a comprehensive deconstruction of this mnemonic:

Table 1: Comprehensive Deconstruction of the SIGNIFICANCE Mnemonic in Green Analytical Chemistry

| Letter | Principle | Technical Interpretation | Key Applications in Drug Development |

|---|---|---|---|

| S | Select direct analytical methods | Avoid sample treatment; use instrumental direct analysis [5] | Near-infrared spectroscopy for raw material identification; Raman spectroscopy for API quantification |

| I | Integrate analytical processes & operations | Combine sampling, preparation, and analysis into automated systems [5] | Online SPE-LC-MS systems for bioanalysis; automated dissolution testing with in-line analysis |

| G | Generate as little waste as possible & recycle | Minimize solvent consumption; implement solvent recycling programs [5] | Micro-extraction techniques for bioanalytical samples; closed-loop solvent recycling in HPLC preparative purification |

| N | Never use hazardous chemicals or large amounts | Substitute hazardous solvents with safer alternatives [5] | Replacement of acetonitrile with ethanol or methanol in HPLC; ionic liquids as green extraction solvents |

| I | Implement automation and miniaturization | Develop automated methods; reduce scale of operations [5] | 384-well plate formats for high-throughput screening; microfluidic devices for ADME screening |

| F | Favor reagents from renewable sources | Choose biobased solvents over petroleum-derived [5] | Use of ethanol from biomass rather than synthetic sources; plant-derived surfactants for extraction |

| I | Increase safety for operator | Reduce exposure to hazardous materials; implement engineering controls [5] | Closed-system sampling for potent compound analysis; automated solid dispensing for cytotoxic compounds |

| C | Carry out in-situ measurements | Perform analysis at point of need rather than transferring samples [5] | Process Analytical Technology (PAT) for real-time monitoring of manufacturing processes; portable GC-MS for facility monitoring |

| A | Avoid derivatives & chemical treatments | Eliminate unnecessary derivatization steps [5] | Direct analysis of carbohydrates without derivatization using HILIC-MS; underivatized amino acid analysis with LC-MS/MS |

| N | Note sample preparation key for greenness | Optimize extraction techniques for minimal environmental impact [5] | Selective pressurized liquid extraction for natural products; QuEChERS sample preparation for pesticide residues |

| C | Choose multi-analyte or multiplexed methods | Analyze multiple components simultaneously rather than sequentially [5] | UHPLC-MS/MS multiplexed assays for drug metabolites; multi-element ICP-MS for elemental impurities |

| E | Enable energy savings by all means | Reduce energy consumption of analytical instrumentation [5] | Low-temperature GC separations; reduced flow rate LC-MS systems; instrument power management protocols |

Strategic Implementation in Pharmaceutical Analysis

The sequential application of the SIGNIFICANCE mnemonic enables systematic greening of analytical methods throughout the drug development pipeline. Beginning with Sample Selection (S), researchers should evaluate whether direct analysis techniques can provide the necessary information without extensive sample preparation. For Integrated Processes (I), modern analytical platforms now offer completely integrated systems that combine sample preparation, separation, and detection in automated workflows, significantly reducing solvent consumption and waste generation while improving reproducibility [5].

The principles of Waste Generation (G) and Hazardous Chemical Avoidance (N) work synergistically in pharmaceutical analysis. Microscale techniques and solvent substitution strategies have demonstrated significant reductions in environmental impact while maintaining analytical performance. For instance, replacing traditional acetonitrile with ethanol or methanol in reversed-phase HPLC methods represents a practical application of these principles that aligns with both green chemistry and industrial practicality [5].

Quantitative Greenness Assessment Metrics for GAC

While the SIGNIFICANCE mnemonic provides qualitative guidance, several quantitative metrics have been developed to objectively evaluate the greenness of analytical methods. These tools enable researchers to numerically assess and compare the environmental performance of different analytical approaches.

Table 2: Green Analytical Chemistry Assessment Metrics and Their Applications

| Assessment Tool | Type | Key Parameters Measured | Scoring System | Pharmaceutical Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEMI (National Environmental Methods Index) | Pictogram [7] | PBT chemicals, hazardous waste, corrosivity, waste amount [7] | Binary (green/white) quadrant pictogram [7] | HPLC method validation for drug impurity testing |

| Analytical Eco-Scale | Point-based [7] | Reagent toxicity, energy consumption, waste production [7] | 100-point ideal; >75 excellent greenness [7] | Comparison of sample preparation techniques for bioanalysis |

| GAPI (Green Analytical Procedure Index) | Pictogram [5] [7] | Multiple stages from sampling to waste treatment [7] | 5 pentagrams color-coded for environmental impact [7] | Lifecycle assessment of API stability-indicating methods |

| AGREE (Analytical Greenness Calculator) | Software-based [7] | 12 GAC principles comprehensively assessed [7] | 0-1 scale with color-coded circular pictogram [7] | Pre-development assessment of candidate analytical methods |

| ComplexGAPI | Advanced pictogram [5] | Holistic assessment including energy and purification [5] | Multi-section colored diagram with weighted areas [5] | Comparative evaluation of HPLC vs. UHPLC methods for formulation analysis |

Advanced Assessment: White Analytical Chemistry (WAC) Scoring

The emergence of White Analytical Chemistry (WAC) has introduced a more balanced evaluation framework that incorporates the traditional greenness assessment with analytical and practical metrics. The WAC approach employs an RGB color model where the Green component assesses environmental impact, the Red component evaluates analytical performance (accuracy, precision, sensitivity), and the Blue component addresses practical/economic aspects (cost, time, operational simplicity) [5].

This tripartite assessment ensures that methods are not only environmentally friendly but also analytically sound and practically feasible for implementation in regulated pharmaceutical environments. WAC scoring has been successfully applied to stability-indicating High-Performance Thin-Layer Chromatography (HPTLC) methods for thiocolchicoside and aceclofenac, demonstrating how environmental considerations can be balanced with analytical requirements in pharmaceutical analysis [5].

Experimental Protocols for GAC Implementation

Protocol 1: Greenness Assessment Using Analytical Eco-Scale

Principle: The Analytical Eco-Scale assigns penalty points to parameters that deviate from ideal green analysis, with higher scores indicating greener methods [7].

Procedure:

- Begin with a perfect score of 100 points

- Subtract penalty points for reagents: (1) amount >0.1 mL (or mg) but <1 mL, subtract 1 point; (2) amount >1 mL (or mg) but <10 mL, subtract 2 points; amount >10 mL (or mg), subtract 3 points

- Subtract penalty points based on reagent hazard: highly hazardous (e.g., strong acids/bases, heavy metals) subtract 6 points; hazardous (e.g., chlorinated solvents) subtract 3 points; less hazardous (e.g., ethanol, water) subtract 1 point

- Subtract points for energy consumption: >1.5 kWh per sample subtract 2 points; >0.1 kWh but <1.5 kWh subtract 1 point; <0.1 kWh subtract 0 points

- Subtract points for waste: subtract 1 point per waste gram generated

- Interpret results: score >75 represents excellent green method; score >50 represents acceptable green method; score <50 represents insufficient green method [7]

Protocol 2: AGREEprep Assessment for Sample Preparation

Principle: AGREEprep is a dedicated software-based tool for evaluating the greenness of sample preparation procedures based on the 10 principles of Green Sample Preparation (GSP) [7].

Procedure:

- Input all sample preparation parameters including sample amount, solvent type and volume, energy consumption, equipment used, and waste generated

- The software calculates scores for each of the 10 GSP principles:

- Principle 1: Minimize or eliminate sample preparation

- Principle 2: Use minimal sample size

- Principle 3: Perform sample preparation in-situ

- Principle 4: Integrate steps of the analytical process

- Principle 5: Use safer alternatives to hazardous reagents

- Principle 6: Minimize waste generation

- Principle 7: Maximize operator safety

- Principle 8: Minimize energy consumption

- Principle 9: Prefer reusable materials

- Principle 10: Automate for efficiency

- The tool generates a circular pictogram with 10 segments, each color-coded from red (poor) to green (excellent)

- An overall score between 0-1 is provided, with higher scores indicating greener sample preparation methods [7]

Diagram: GAC Method Development Workflow

Diagram 1: GAC Method Development Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Green Alternative Reagents for Pharmaceutical Analysis

| Reagent Category | Traditional Reagents | Green Alternatives | Function in Analysis | Key Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extraction Solvents | Chloroform, dichloromethane, hexane [7] | Ethyl acetate, cyclopentyl methyl ether, 2-methyltetrahydrofuran [5] | Sample preparation, compound isolation | Reduced toxicity, improved biodegradability, safer waste profiles |

| Chromatographic Mobile Phases | Acetonitrile, methanol with modifiers [5] | Ethanol, water with temperature control, supercritical CO₂ [5] | Liquid chromatography separation | Lower environmental impact, reduced hazardous waste, renewable sources |

| Derivatization Agents | HFBA, BSTFA, DNPH | No-derivatization approaches, microwave-assisted synthesis [5] | Analyte functionalization for detection | Elimination of hazardous reagent use, simplified workflows |

| Calibration Standards | Organic solvent-based stock solutions | Aqueous-based standards, stable isotope-labeled internal standards [5] | Quantitative analysis reference | Reduced organic solvent consumption, improved accuracy |

| Sample Preservation Agents | Sodium azide, thymol | Ascorbic acid, low-temperature storage [5] | Biological sample stabilization | Reduced toxicity, compatibility with analytical systems |

The SIGNIFICANCE mnemonic provides a comprehensive, actionable framework for implementing Green Analytical Chemistry principles in pharmaceutical research and drug development. Through systematic application of each principle and rigorous assessment using established greenness metrics, researchers can significantly reduce the environmental impact of analytical methods while maintaining the high-quality data required for regulatory submissions and product quality assurance. The evolution toward White Analytical Chemistry represents a more holistic approach that balances environmental sustainability with analytical performance and practical feasibility, ensuring that green methods are not only theoretically sound but also practically implementable in real-world pharmaceutical settings. As green financing models like GFAC (Green Financing for Analytical Chemistry) emerge to support sustainable method development, the integration of these principles throughout the drug development lifecycle will become increasingly essential for environmentally responsible pharmaceutical innovation [5].

Waste Minimization, Safety, and Energy Efficiency

Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) has emerged from the broader framework of green chemistry, establishing itself as a critical discipline for making laboratory practices more environmentally friendly and sustainable [21]. The core objective of GAC is to reach a compromise between the increasing quality of analytical results and improving the environmental friendliness of the methods [21]. This guide details the key concepts of waste minimization, safety, and energy efficiency, which form the backbone of the 12 principles of GAC and are encapsulated in the SIGNIFICANCE mnemonic, providing a structured framework for researchers and drug development professionals to implement these practices effectively [21].

The following diagram illustrates the core decision-making workflow in Green Analytical Chemistry, focusing on the three pillars of waste minimization, safety, and energy efficiency.

The SIGNIFICANCE Mnemonic and GAC Principles

The 12 principles of Green Analytical Chemistry provide a comprehensive guideline for greening laboratory practices [21]. These principles have been condensed into the SIGNIFICANCE mnemonic to aid in their recall and application [21]. The three focal points of this guide—waste minimization, safety, and energy efficiency—are deeply embedded within these principles.

Table 1: The 12 Principles of Green Analytical Chemistry

| Principle Number | Principle Description | Core Concept |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Select direct analytical techniques to avoid sample treatment. | Waste Minimization |

| 2 | Employ minimal sample size and number of samples. | Waste Minimization |

| 3 | Perform in-situ measurements. | Energy Efficiency |

| 4 | Integrate analytical processes and operations. | Energy Efficiency |

| 5 | Choose automated and miniaturized methods. | Waste Minimization, Energy Efficiency |

| 6 | Avoid derivatization. | Safety, Waste Minimization |

| 7 | Avoid large volume of waste; manage properly. | Waste Minimization, Safety |

| 8 | Use multi-analyte or multi-parameter methods. | Waste Minimization, Energy Efficiency |

| 9 | Choose natural, renewable, or less harmful reagents. | Safety |

| 10 | Use reagents from renewable sources. | Safety |

| 11 | Eliminate or replace hazardous reagents. | Safety |

| 12 | Ensure operator's safety. | Safety |

The SIGNIFICANCE Mnemonic

The SIGNIFICANCE mnemonic is a practical tool that encapsulates the core tenets of GAC [21]:

- S - Sample directness and minimal number

- I - In-situ measurements

- G - Green solvents and reagents

- N - No waste generation

- I - Integration of processes

- F - Fast analysis

- I - Automation and miniaturization

- C - Clean and safe procedures

- A - Avoidance of derivatization

- N - Energy efficiency

- C - Cost-effectiveness

- E - Operator safety

Quantitative Data on Waste and Energy Impacts

Effective implementation of GAC principles leads to tangible environmental benefits. A 2025 study by the European Commission's Joint Research Centre provides a quantitative assessment of the impacts of waste management, highlighting the significant potential for improvement [22].

Table 2: Environmental and Economic Impact of EU Waste Management (2025 Data)

| Metric | Value | Context and Comparison |

|---|---|---|

| Annual GHG Emissions Saved | 34 million t CO₂-eq. | Saved by current EU waste management practices [22] |

| GHG Saved per Tonne of Waste | 17 kg CO₂-eq. | Net saving; global waste management is a net emitter (≈250 kg CO₂-eq./tonne) [22] |

| Key Contributor to Savings | Metal waste management | Drives 83% of the EU's emissions savings from waste management [22] |

| Societal Cost of Management | €136 billion annually | Equates to €68 per tonne of waste managed, or €304 per citizen [22] |

| Plastic Packaging Recycling | 41% | Percentage currently separately collected and sent for recycling in the EU [22] |

| Textile Waste Recycling | 22% | Percentage of post-consumer textile waste separately collected and recycled [22] |

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols for GAC Implementation

Workflow for Sample Preparation and Analysis

Adhering to GAC principles requires re-evaluating every step of the analytical process. The following workflow provides a visual guide for designing a green sample preparation and analysis protocol.

Detailed Methodological Approaches

- Direct Analytical Techniques (Principle 1): Implement direct analysis methods like near-infrared (NIR) spectroscopy or X-ray fluorescence (XRF) to eliminate extensive sample preparation, thereby reducing solvent use and waste generation [21].

- Automated and Miniaturized Methods (Principle 5): Employ flow injection analysis (FIA), lab-on-a-chip (LOC) technologies, or automated solid-phase extraction (SPE) systems. These systems reduce reagent consumption from milliliters to microliters and enhance analytical throughput while lowering energy requirements [21].

- Waste Management and Treatment (Principle 7): For unavoidable waste, establish procedures for on-site neutralization, recycling, or concentration. The US EPA's Waste Reduction Model (WARM) provides a high-level tool for comparing the greenhouse gas emissions impacts of different waste management practices, including recycling and combustion [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The choice of reagents and materials is fundamental to the safety and greenness of an analytical method.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Green Analytical Chemistry

| Item / Category | Function & Application | Green Rationale & Alternative |

|---|---|---|

| Water & Ethanol | Primary green solvents for extraction and chromatography. | Replace hazardous solvents like chlorinated methanes or benzene. They are renewable, less toxic, and biodegradable [21]. |

| Ionic Liquids | Salts in liquid state used as solvents or electrolytes. | Low volatility reduces inhalation hazards and atmospheric pollution compared to traditional volatile organic compounds (VOCs) [21]. |

| Natural Reagents | Biosourced compounds (e.g., cyclodextrins) for complexation. | Derived from renewable sources, generally less toxic, and reduce dependency on petrochemical-based reagents [21]. |

| Solid-Phase Microextraction (SPME) Fibers | Solvent-free extraction and pre-concentration of analytes. | Eliminates the need for large volumes of organic solvents used in traditional liquid-liquid extraction [21]. |

| Micro-Scale Labware | Miniaturized reactors, columns, and chips for analysis. | Dramatically reduces consumption of samples, reagents, and solvents, directly minimizing waste generation [21]. |

The integration of waste minimization, safety, and energy efficiency through the framework of the 12 GAC principles and the SIGNIFICANCE mnemonic provides a robust pathway for modern analytical laboratories to advance their sustainability [21]. As evidenced by recent quantitative studies, the proper management of analytical waste and a conscious effort to reduce energy consumption and hazardous materials have a direct and significant impact on reducing greenhouse gas emissions and societal costs [22]. For researchers and drug development professionals, adopting these principles is no longer optional but a critical component of responsible and forward-thinking scientific practice.

The Ethical and Economic Imperative for GAC in Pharmaceutical Development

Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) represents a transformative approach to drug analysis that seeks to eliminate or reduce the use of hazardous substances while making analytical processes more efficient and environmentally benign. First articulated by Paul Anastas, GAC has evolved from a theoretical concept to an essential framework for sustainable pharmaceutical development [24]. The conventional analytical methods used in pharmaceuticals, such as high-pressure liquid chromatography and gas chromatography, traditionally consume significant energy and produce substantial chemical debris that threatens natural ecosystems [24]. The implementation of GAC principles addresses these environmental challenges while simultaneously creating economic value and ethical advantages throughout the drug development pipeline.

The SIGNIFICANCE mnemonic framework organizes the core principles of GAC into a actionable strategy for implementation. This comprehensive approach aligns with growing regulatory pressures and stakeholder expectations for environmentally conscious manufacturing practices. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, mastering GAC is no longer optional but imperative for developing sustainable, cost-effective, and ethically defensible pharmaceutical products.

The SIGNIFICANCE of GAC: A Mnemonic Framework for Implementation

Core Principles Breakdown

The SIGNIFICANCE mnemonic encapsulates the essential principles of Green Analytical Chemistry, providing a structured framework for implementation in pharmaceutical development:

- S - Sample Management: Focus on reducing sample sizes and implementing direct analysis techniques to minimize reagent consumption and waste generation [24].

- I - Instrumental Analysis: Prioritize automated and miniaturized systems that enhance energy efficiency while maintaining analytical precision.

- G - Green Solvents: Substitute hazardous organic solvents with safer, biodegradable alternatives wherever technically feasible.

- N - Non-Destructive Methods: Develop and implement analytical procedures that preserve sample integrity for potential reuse or further testing.

- I - In-Process Monitoring: Integrate real-time analysis within manufacturing to reduce quality control cycles and resource consumption.

- F - Fuel Efficiency: Optimize instrument energy consumption through method optimization and equipment modernization.

- I - Integration of Techniques: Combine multiple analytical procedures to streamline workflows and reduce overall resource requirements.

- C - Chemical Waste Management: Implement systematic approaches to reduce, reuse, and recycle chemical byproducts from analytical processes.

- A - Automation: Employ robotic systems and automated platforms to enhance precision while reducing solvent and energy usage.

- N - New Technologies: Continuously evaluate and adopt emerging green technologies that offer environmental and economic advantages.

- C - Carbon Footprint Reduction: Monitor and minimize greenhouse gas emissions throughout analytical operations.

- E - Energy Consumption: Systematically track and optimize energy usage across all analytical instrumentation and processes [24].

Quantitative Impact Assessment

Table 1: Economic and Environmental Impact of GAC Implementation in Pharmaceutical Analysis

| Parameter | Traditional Methods | GAC-Implemented Methods | Percentage Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solvent Consumption | 500-1000 mL per analysis | 50-100 mL per analysis | 80-90% reduction |

| Energy Usage | 3-5 kWh per sample run | 1-2 kWh per sample run | 60-70% reduction |

| Analysis Time | 4-8 hours typical | 1-3 hours typical | 50-75% reduction |

| Waste Generation | 400-900 mL organic waste | 40-90 mL treated waste | 85-90% reduction |

| Operational Cost | $150-300 per analysis | $50-120 per analysis | 60-70% savings |

Experimental Protocols for GAC Implementation

Method Transformation Protocol: HPLC to UPLC

Objective: Transform conventional High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) methods to Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography (UPLC) platforms to reduce solvent consumption and analysis time while maintaining analytical quality.

Materials and Reagents:

- UPLC System: Equipped with HSS T3 column (1.8 μm, 2.1 × 100 mm)

- Mobile Phase: Acetonitrile/water mixture versus methanol/water alternatives

- Reference Standards: Pharmaceutical compound of interest

- Sample Preparation: Required solvents for extraction

Procedure:

- Method Scouting: Evaluate the original HPLC method parameters including column type, mobile phase composition, gradient program, flow rate, and detection wavelength.

- Column Selection: Transition to smaller particle size columns (1.7-1.8 μm) to maintain resolution at higher flow rates.

- Mobile Phase Optimization: Reduce organic modifier concentration by 15-30% while maintaining separation efficiency.

- Flow Rate Adjustment: Increase flow rates proportionally to column dimension changes while monitoring backpressure limits.

- Gradient Compression: Shorten gradient times by 50-70% while preserving critical peak separations.

- Temperature Optimization: Evaluate column temperatures between 35-45°C to improve efficiency without compromising stability.

- Validation: Conduct full method validation per ICH guidelines including specificity, linearity, accuracy, precision, and robustness.

Green Metrics Assessment:

- Calculate solvent reduction volume per analysis

- Quantify energy savings from reduced run times

- Document waste minimization through smaller waste streams

Direct Analysis Protocol for Tablets

Objective: Implement direct solid analysis techniques to eliminate extensive sample preparation and solvent consumption in quality control testing of solid dosage forms.

Materials and Reagents:

- Handheld NIR/Raman Spectrometer: With appropriate spectral range and resolution

- Reference Standard: Pharmaceutical active ingredient

- Excipient Blends: Matching formulation composition

- Calibration Set: Tablets with varying API concentrations (70-130% of label claim)

Procedure:

- Instrument Calibration: Establish multivariate calibration models using reference analytical methods (e.g., HPLC) for correlation.

- Spectral Collection: Acquire spectra from multiple positions on each tablet surface to account for homogeneity variations.

- Model Development: Utilize chemometric software to develop partial least squares (PLS) regression models correlating spectral data to reference values.

- Model Validation: Test prediction accuracy against independent validation sets not used in model development.

- Routine Analysis: Implement for incoming raw material identification, blend uniformity assessment, and finished product testing.

Environmental Impact Assessment:

- Elimination of solvent consumption for sample preparation

- Reduction in energy consumption from eliminated extraction steps

- Minimization of hazardous waste generation

Research Reagent Solutions for GAC Implementation

Table 2: Essential Green Analytical Chemistry Reagents and Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function in GAC | Traditional Hazardous Alternative |

|---|---|---|

| Water-Ethanol Mixtures | Green mobile phase for chromatography | Acetonitrile or methanol mixtures |

| Hydrophilic Interaction Liquid Chromatography (HILIC) Columns | Enable high efficiency separations with aqueous mobile phases | Reverse-phase C18 columns requiring organic modifiers |

| Supercritical CO₂ | Extraction and chromatography solvent | Hexane, dichloromethane, or other halogenated solvents |

| Ionic Liquids | Green solvents for extraction and analysis | Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) |

| Biosynthesized Nanoparticles | Catalysts for green synthesis and detection | Heavy metal catalysts |

| Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) | Biodegradable solvents for extraction | Petroleum-derived solvents |

| Solid-Phase Microextraction (SPME) Fibers | Solvent-free sample preparation | Liquid-liquid extraction |

| Chemometric Software Packages | Enable method optimization and reduce experimental runs | Trial-and-error method development |

GAC Integration in Drug Development Stages

The Stage-Gate process for drug development provides a structured framework for implementing GAC principles throughout the product lifecycle [25]. The following visualization illustrates how GAC principles integrate into each stage of pharmaceutical development:

Stage-Specific GAC Implementation

Stage 1: Scoping and Feasibility - During initial drug product definition, GAC principles focus on assessing green solvent alternatives and selecting energy-efficient instrumentation platforms [25]. Teams evaluate manufacturing feasibility with specific attention to CMC (Chemistry, Manufacturing, and Controls) risks related to environmental impact and sustainable sourcing of raw materials.

Stage 2: Preclinical Development - Analytical method development incorporates green solvent alternatives and miniaturized techniques [24]. Teams implement microsampling approaches to reduce animal usage and analytical waste while supporting toxicity studies with environmentally conscious CMC data practices.

Stage 3: Clinical Development - Scaling up manufacturing processes integrates green chemistry principles and energy-efficient technologies [25]. GAC approaches ensure clinical trial materials are produced with minimal environmental footprint while maintaining GMP compliance and product quality.

Stage 4: Regulatory Approval - The CMC regulatory package demonstrates implementation of green principles throughout development [25]. Companies highlight environmentally conscious manufacturing processes, waste reduction strategies, and sustainable analytical methods while meeting all quality assurance requirements.

Stage 5: Launch and Post-Marketing Surveillance - Continuous improvement of manufacturing processes incorporates advancing GAC technologies [25]. Environmental monitoring throughout the product lifecycle ensures ongoing compliance with evolving sustainability standards while maintaining product quality and safety.

Economic Advantages of GAC Implementation

The economic imperative for GAC adoption extends beyond regulatory compliance to substantial financial benefits throughout the drug development pipeline. Generic and biosimilar medicines, which increasingly employ GAC principles in their development, saved the U.S. healthcare system $408 billion in 2022 alone [26]. Over the past decade, these savings have exceeded $2.9 trillion, demonstrating the significant economic impact of efficient, cost-effective pharmaceutical development [26].

Cost-Benefit Analysis of GAC Implementation

Table 3: Comprehensive Economic Analysis of GAC Implementation

| Cost Category | Traditional Approach | GAC-Implemented Approach | Economic Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solvent Procurement | $50,000-100,000 annually | $10,000-20,000 annually | 75-80% reduction |

| Waste Disposal | $15,000-30,000 annually | $3,000-6,000 annually | 75-80% reduction |

| Energy Consumption | $25,000-50,000 annually | $10,000-20,000 annually | 55-65% reduction |

| Analytical Throughput | 8-12 samples per day | 20-30 samples per day | 120-150% improvement |

| Regulatory Compliance | High risk of environmental citations | Minimal compliance issues | Risk mitigation |

| Capital Investment | Standard equipment | Potential premium for green tech | 10-20% higher initial cost |

The brand versus generic drug study further demonstrates the economic implications of efficient drug development approaches. Interestingly, research has shown that patients using brand-name medications demonstrated higher adherence and persistence rates for certain drug classes, though generic drugs create substantial system-wide savings [27]. This paradox highlights the need for balanced approaches that consider both economic and patient-centric outcomes.

Regulatory Landscape and Quality Considerations

The regulatory environment for pharmaceutical development continues to evolve with increasing emphasis on environmental sustainability. The Orphan Drug Act in the USA and subsequent Regulation No 141/2000 in the EU created frameworks that have increased approvals of drugs for rare diseases by 3-11 fold in the decade 2013-2023 compared to 1990-2000 [28]. These regulatory frameworks increasingly incorporate environmental considerations into the approval process.

Good Distribution Practices (GDP) compliance standards now frequently include environmental components, with companies implementing "optimum healthcare logistics efficiency with agile, flexible supply chain while ensuring complete product integrity and compliance from end-to-end" [29]. The pharmaceutical industry faces increasing pressure to demonstrate environmental responsibility throughout the product lifecycle, from raw material sourcing to end-of-life disposal.

Quality control in GAC-implemented processes must maintain the same rigorous standards as traditional methods. "Quality control and process measurements from start to finish deliver a fully auditable supply chain process essential for the business," ensuring that environmental improvements do not compromise product quality or patient safety [29].

Green Analytical Chemistry represents both an ethical obligation and economic opportunity for the pharmaceutical industry. The SIGNIFICANCE framework provides a structured approach for implementation across all stages of drug development, from initial scoping through post-marketing surveillance. The environmental benefits of reduced solvent consumption, minimized waste generation, and lower energy usage simultaneously create substantial economic advantages through reduced operational costs and enhanced efficiency.

For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, embracing GAC principles is no longer optional but essential for sustainable success in an increasingly environmentally conscious regulatory and market landscape. The integration of GAC methodologies represents the future of responsible pharmaceutical innovation that balances patient needs, economic realities, and planetary health.

Implementing GAC: Practical Strategies and Green Methodologies for the Lab

The adoption of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) principles represents a paradigm shift in analytical science, focusing on the development of methodologies that minimize environmental impact while maintaining high analytical standards [4] [3]. Sample preparation, often the most resource-intensive step in analytical procedures, has become a primary target for greening efforts. Traditional sample preparation methods frequently involve large volumes of hazardous organic solvents, significant energy consumption, and generation of substantial waste [30] [31]. In response to these environmental concerns, the field has witnessed substantial innovation centered on microextraction techniques and solvent-free approaches that align with the principles of green chemistry.

The concept of "green sample preparation" is not a separate subdiscipline but rather a guiding principle that promotes sustainable development through the adoption of environmentally benign procedures [32]. This transition is driven by both regulatory pressures and a growing recognition of environmental responsibility within the scientific community. The movement toward greener methodologies has been accelerated by the development of comprehensive assessment tools that allow researchers to evaluate and compare the environmental footprint of their analytical methods systematically [33] [34]. These developments have established a clear pathway for transforming traditional sample preparation into a more sustainable practice.

Principles and Framework of Green Sample Preparation

The SIGNIFICANCE Mnemonic in GAC

The SIGNIFICANCE mnemonic provides a practical framework for implementing Green Analytical Chemistry principles, with direct applications to sample preparation. This framework emphasizes Safety, Inexpensiveness, and Minimal environmental impact as core objectives. Within this structure, microextraction and solvent-free techniques directly address these goals by reducing or eliminating hazardous solvents, decreasing waste generation, and improving operator safety [35] [32].

The principles of green sample preparation specifically advocate for the use of safe solvents/reagents and renewable materials, minimizing waste generation and energy demand, and enabling high sample throughput through miniaturization and automation [32]. These principles align with the broader SIGNIFICANCE framework by promoting methods that are not only environmentally responsible but also economically viable and practically efficient. The integration of these concepts provides a comprehensive approach for developing analytical methods that meet modern sustainability requirements without compromising analytical performance.

Green Metrics and Assessment Tools

The evolution of greenness assessment tools has been crucial for objectively evaluating and comparing the environmental impact of analytical methods. Early tools like the National Environmental Methods Index (NEMI) employed a simple pictogram system but lacked granularity for distinguishing between degrees of greenness [34]. The field has since progressed to more sophisticated metrics that provide comprehensive evaluations of analytical workflows.

Table 1: Greenness Assessment Tools for Analytical Methods

| Assessment Tool | Type of Output | Key Features | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| NEMI [34] | Binary pictogram | Simple, user-friendly; assesses toxicity, waste, corrosiveness | Lacks granularity; doesn't cover full analytical workflow |

| Analytical Eco-Scale [34] | Numerical score (0-100) | Applies penalty points to non-green attributes; allows method comparison | Relies on expert judgment; lacks visual component |

| GAPI [34] | Color-coded pictogram | Covers entire analytical process; visual identification of high-impact stages | No overall score; somewhat subjective color assignments |

| AGREE [34] | Numerical score (0-1) + pictogram | Based on 12 GAC principles; comprehensive coverage; user-friendly interface | Doesn't fully account for pre-analytical processes |

| AGREEprep [34] | Numerical score + pictogram | First tool dedicated to sample preparation; visual and quantitative outputs | Must be used with broader tools for full method evaluation |

| AGSA [34] | Star-shaped diagram + score | Intuitive visualization; integrates multiple green criteria | Newer tool with less established track record |