Scaling Green Chemistry in Pharma: Overcoming Industrial Hurdles for Sustainable Drug Manufacturing

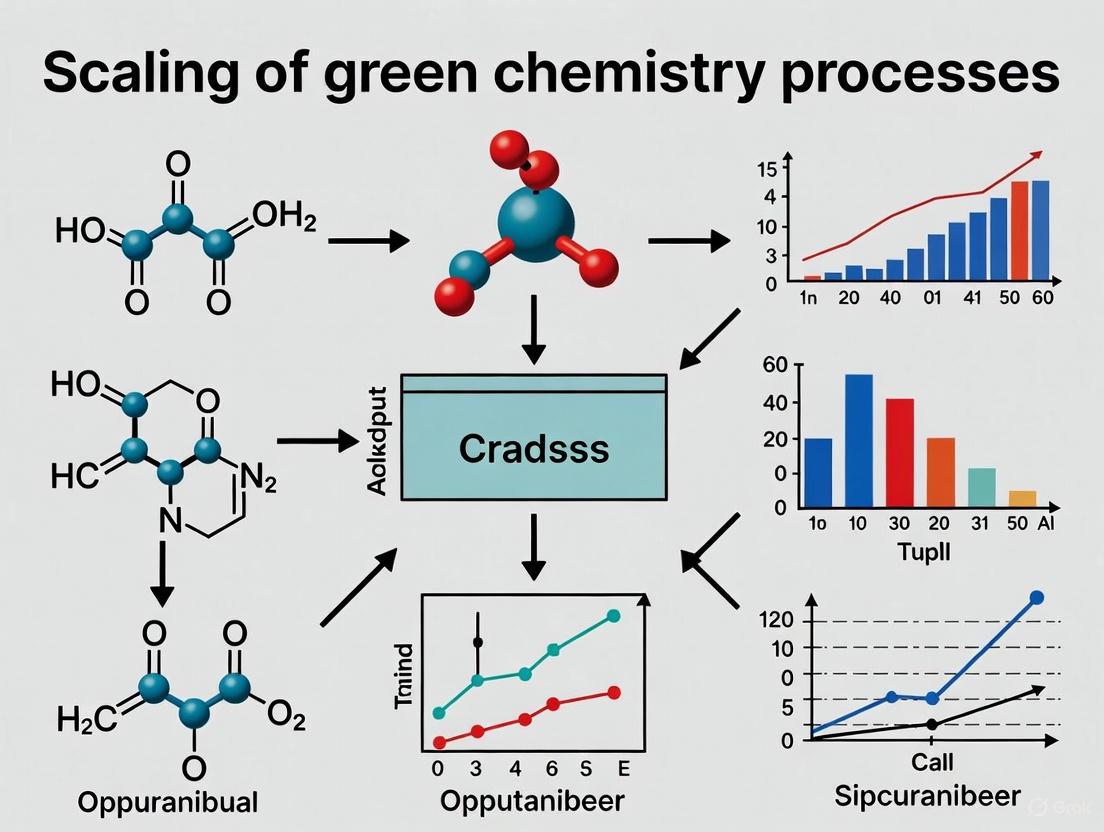

This article addresses the critical challenges and solutions in scaling green chemistry principles for industrial pharmaceutical manufacturing.

Scaling Green Chemistry in Pharma: Overcoming Industrial Hurdles for Sustainable Drug Manufacturing

Abstract

This article addresses the critical challenges and solutions in scaling green chemistry principles for industrial pharmaceutical manufacturing. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the regulatory and economic drivers, details emerging technologies like biocatalysis and continuous flow synthesis, provides strategies for troubleshooting common scale-up bottlenecks, and offers frameworks for validating the environmental and economic benefits of greener processes. The content synthesizes current trends to provide a practical roadmap for integrating sustainability into core pharmaceutical R&D and production.

The Urgent Drive for Green Pharma: Regulations, Economics, and Environmental Imperatives

Quantitative Analysis of Pharmaceutical Waste and Emissions

This section provides consolidated quantitative data on pharmaceutical waste and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, essential for establishing an environmental baseline in research and development.

Global Pharmaceutical Greenhouse Gas Emissions

Table 1: Global Pharmaceutical Greenhouse Gas Emissions (1995-2019)

| Metric | Findings | Data Source/Time Period |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Global Growth | Increase of 77% in GHG footprint | 1995 to 2019 [1] |

| Primary Driver | Rising pharmaceutical final expenditure, particularly in China; efficiency gains stalled post-2008 | 1995 to 2019 [1] |

| Per Capita Inequality | High-income countries' footprint was 9-10 times higher than lower-middle-income countries | 1995-2019 average [1] |

| Emission Intensity | 48.55 tonnes of CO2 equivalent per million dollars of revenue | 2015 Data [2] [3] |

| Comparative Intensity | 55% higher than the automotive industry (31.4 tonnes CO2e/$M) | 2015 Data [2] [3] |

Pharmaceutical Waste Composition and Quantification

Table 2: Pharmaceutical Waste Composition and Management Data

| Aspect | Findings | Location/Context |

|---|---|---|

| Total National Waste | Peak of 542 tonnes collected in 2019 | New Zealand [4] |

| Regional Concentration | 75.1% of national waste from the Auckland region | New Zealand (2016-2020) [4] |

| Waste Source Increase | Fourfold increase from community pharmacies (759 kg to 3290 kg) | Auckland (Sep 2016 vs Sep 2020) [4] |

| Common Drug Classes | Nervous system, cardiovascular system, alimentary tract & metabolism | Audit of 12 community pharmacy waste bins [4] |

| Product Diversity | 475 different pharmaceutical products identified | Audit of 12 community pharmacy waste bins [4] |

Experimental Protocols for Environmental Impact Assessment

Protocol 1: Non-Target Analysis of Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Emissions in Wastewater

This methodology uses high-resolution mass spectrometry to detect and attribute industrial pharmaceutical discharges in water bodies [5].

- Application: Detecting discharges from pharmaceutical production in municipal wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) effluents and estimating their contribution to total emissions.

- Sample Collection: Daily composite samples are collected over an extended period (e.g., 3 months) at the WWTP effluent.

- Instrumentation: Analysis using Liquid Chromatography-High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry (LC-HRMS).

- Data Processing & Analysis:

- Generate time series for all detected chemical features.

- Differentiate domestic inputs from industrial emissions based on intensity variation in the time series. A variation threshold of 10 can be used to correctly classify compounds.

- Quantify concentrations of identified pharmaceuticals. Peak concentrations >10 μg/L indicate industrial emission points.

- Trace signatures of industrial emissions even in diluted downstream river systems.

- Troubleshooting Tip: If background interference is too high, optimize the LC separation method or apply more stringent data filtration algorithms to isolate true fluctuating signals.

Protocol 2: Pharmaceutical Waste Audit and Composition Analysis

This protocol provides a standardized method for auditing the composition of solid pharmaceutical waste, crucial for understanding waste streams and evaluating disposal practices [4].

- Application: Quantifying and categorizing pharmaceutical waste from specific sources like community pharmacies or hospitals.

- Sample Collection: Obtain random bins (e.g., 120 L capacity) of pharmaceutical waste from contracted disposal services.

- Sorting and Identification:

- Manually sort the contents of the waste bin.

- Record the name, strength, formulation, and number of units for each medicine.

- For unidentifiable tablets/capsules, use photographic evidence and online data sheets for reverse identification.

- Data Categorization:

- Assign each drug a therapeutic group using the World Health Organisation Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification index.

- Flag hazardous drugs (e.g., cytotoxics) for separate tracking.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the frequency of appearance and total units for each pharmaceutical product to determine the most prevalent drugs in the waste stream.

- Troubleshooting Tip: When dealing with unlabeled or decomposed products, prioritize researcher safety by using appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) and document these items as "unidentifiable" to maintain data integrity.

Visualizing Analysis and Emission Workflows

Pharmaceutical Waste Audit Workflow

Pharmaceutical Carbon Emission Scopes

Research Reagent Solutions for Green Chemistry

Table 3: Key Reagents and Technologies for Sustainable Pharmaceutical Research

| Reagent/Technology | Function | Green Chemistry Principle |

|---|---|---|

| Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) [6] | Customizable, biodegradable solvents for extraction; replace volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and strong acids. | Safer Solvents & Auxiliaries, Waste Prevention |

| Biocatalysts (Enzymes) [2] [7] | Biological catalysts for synthesis (e.g., oligonucleotides); replace toxic metal-based catalysts, enable milder conditions. | Catalysis, Less Hazardous Chemical Syntheses |

| Mechanochemistry (Ball Milling) [6] | Uses mechanical energy (grinding) to drive reactions, eliminating the need for solvent use. | Safer Solvents, Design for Energy Efficiency |

| Water as a Reaction Medium [6] | Non-toxic, non-flammable solvent for "in-water" or "on-water" reactions, leveraging unique interfacial properties. | Safer Solvents, Accident Prevention |

| HFA-152a Propellant [7] | A low-global-warming-potential propellant for Metered-Dose Inhalers (MDIs), replacing high-GWP alternatives. | Designing Benign Chemicals |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) for Troubleshooting

Q1: Our analysis of wastewater for pharmaceutical residues shows high background interference. How can we improve the signal-to-noise ratio for detecting industrial discharges?

A1: High background is a common challenge. Optimize your LC separation method to achieve better chromatographic resolution. During data processing, apply a intensity variation threshold (e.g., a factor of 10) to filter out compounds with relatively constant domestic input signals, focusing on highly fluctuating features that are signatures of industrial emissions [5].

Q2: We are auditing pharmaceutical waste and finding many unidentifiable tablets without original packaging. What is the safest and most effective protocol for handling these?

A2: Researcher safety is paramount. Always use appropriate Personal Protective Equipment (PPE). For identification, take clear photographs of the unidentifiable items and perform a structured online reverse image search cross-referenced with pharmaceutical data sheets. Document any items that cannot be confidently identified as "unidentifiable" to maintain the accuracy of your dataset [4].

Q3: What are the most impactful areas to target when aiming to reduce the carbon footprint of a new drug's synthesis?

A3: Focus on the supply chain (Scope 3 emissions), which often constitutes over 90% of a product's total carbon footprint [7]. Prioritize green chemistry innovations such as solvent replacement (e.g., with water or DES), catalysis (especially biocatalysis), and transitioning from batch to continuous manufacturing processes, which typically have a smaller physical and energy footprint [2] [3] [6].

Q4: Our lab wants to replace traditional organic solvents with greener alternatives. What are some viable options for pharmaceutical synthesis?

A4: Excellent initiatives include:

- Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES): Biodegradable and often recyclable [6].

- Water: Can be used for many "in-water" and "on-water" reactions, leveraging its unique properties [6].

- Solvent-Free Synthesis (Mechanochemistry): Eliminates solvent use entirely by using mechanical energy to drive reactions [6]. The choice depends on your specific reaction chemistry, but these options cover a wide range of applications.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common REACH Compliance Challenges

This section addresses specific, high-frequency problems researchers encounter when aligning laboratory-scale green chemistry processes with EU regulatory requirements.

Problem 1: My substance is flagged as an SVHC. How can I proceed with my research and future product development?

- Issue: A substance you are using appears on the Candidate List of Substances of Very High Concern (SVHCs) [8] [9].

- Solution:

- Immediate Action: Check the ECHA website to confirm the substance's SVHC status and the associated Authorization List, which details if and when the SVHC requires authorisation for specific uses [10] [8].

- Substitution Planning: Begin searching for safer alternatives. ECHA's SCIP database and various green chemistry guides can help identify potential substitutes. The core principle of the Authorisation process is to ensure SVHCs are progressively replaced by suitable alternatives [10] [11].

- Understand Exemptions: For research and development, substances used in scientific research and development are exempt from authorisation under certain conditions. However, you must verify the specific scope and tonnage limits of this exemption for your work [8].

- Long-Term Strategy: If substitution is not immediately technically or economically feasible, you may need to apply for authorisation to continue the use. This requires demonstrating that the risks are adequately controlled or that the socio-economic benefits outweigh the risks [10].

Problem 2: I am developing a polymer. What are my obligations under the upcoming REACH revision?

- Issue: Uncertainty about regulatory requirements for polymers, which are currently exempt from registration [12].

- Solution:

- Stay Informed: The expected REACH revision in late 2025 includes a major change: the notification of polymers produced over 1 tonne per year and mandatory registration for polymers identified as ‘Polymers Requiring Registration’ (PRR) [12].

- Data Collection: Proactively start gathering data on the polymer's composition, including monomer identity, and physicochemical properties.

- Monitor Updates: Follow ECHA and European Commission announcements closely for the final legislative text and associated guidance documents to understand the full scope and deadlines.

Problem 3: How do I account for the "cocktail effect" of chemical mixtures in my risk assessment?

- Issue: Traditional risk assessment evaluates substances one-by-one, but real-life exposure involves mixtures, leading to potential "cocktail effects." [11]

- Solution:

- Anticipate Regulatory Change: The REACH revision is expected to introduce a Mixture Assessment Factor (MAF) for substances registered at over 1000 tonnes per year to account for combined exposure [12].

- Adopt Grouping Strategies: Even before it becomes mandatory, proactively assess and regulate entire groups of chemicals with similar structures or properties in your research. This approach is encouraged to prevent "regrettable substitution" and simplify assessments [11].

- Review Literature: Investigate existing scientific data on the mixture toxicity of the substances you are working with.

Problem 4: My Safety Data Sheet (SDS) is not being accepted by EU partners.

- Issue: Non-compliant or outdated SDS format and content.

- Solution:

- Ensure REACH Compliance: An SDS must be provided for all hazardous substances and mixtures, prepared in accordance with Annex II of REACH [8] [9].

- Prepare for Digital Transition: The EU is shifting towards fully digital labelling and digital Safety Data Sheets as part of the Digital Product Passport (DPP) initiative [12]. Invest in systems that can manage digital compliance data.

- Use Latest Templates: Ensure your SDS uses the most current format and includes all required sections, such as information on safe handling, emergency measures, and, if applicable, SVHCs present above 0.1% w/w [8].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is REACH and who does it apply to? A1: REACH (Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals) is the EU's main chemical regulation. It applies to all chemical substances manufactured, imported, or used within the European Union and EEA countries (Iceland, Liechtenstein, and Norway). It places the responsibility on industry to manage chemical risks [8] [9].

Q2: What is the "one substance, one registration" principle? A2: This REACH principle means that all manufacturers and importers of the same substance must submit their registration jointly through a Substance Information Exchange Forum (SIEF). This avoids duplicate testing and ensures data is shared [8].

Q3: What are Substances of Very High Concern (SVHCs) and where can I find them listed? A3: SVHCs are substances with serious health or environmental effects, such as carcinogens, mutagens, reproductive toxicants (CMRs), and persistent, bioaccumulative and toxic (PBT) substances. They are listed on the "Candidate List," which is updated every six months, most recently in June 2025 [8] [9].

Q4: Are there obligations for substances below the 1-tonne-per-year registration threshold? A4: Yes. While the registration obligation starts at 1 tonne per year, other REACH obligations like restrictions, authorisation, and communication in the supply chain (e.g., providing Safety Data Sheets for hazardous substances) apply irrespective of tonnage [8].

Q5: What is the difference between Authorisation and Restriction under REACH? A5:

- Authorisation: Focuses on SVHCs. It requires companies to seek permission for specific uses of these substances, with the goal of eventually replacing them with safer alternatives [10].

- Restriction: Can apply to any substance posing an unacceptable risk. It can limit or ban the manufacture, placing on the market, or use of a substance [10].

Q6: What are the consequences of non-compliance with REACH? A6: Non-compliance can lead to severe penalties, including products being blocked at EU borders, significant financial fines, and in severe cases, imprisonment [9]. Enforcement is strengthening, with a focus on SVHCs in products [12].

Key REACH Processes and Timelines

| Process | Trigger / Threshold | Key Objective | Authority |

|---|---|---|---|

| Registration [10] [8] | ≥ 1 tonne per year per company | Collect and assess data on substance properties and risks. | European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) & Registrants |

| Evaluation [10] | Dossier and substance evaluation | Check compliance and quality of registration dossiers; investigate substances of concern. | ECHA & Member States |

| Authorisation [10] | Substance on the Authorisation List (SVHC) | Phase out SVHCs by replacing them with safer alternatives. | European Commission |

| Restriction [10] | Unacceptable risk to health/environment | Limit or ban the manufacture, market placement, or use of certain substances. | European Commission |

Expected Key Changes in the REACH Revision (Expected 2025)

| Area of Change | Proposed Update |

|---|---|

| Registration Validity [12] | 10-year validity for chemical registrations; ECHA empowered to revoke registrations. |

| Polymers [12] | Notification for polymers (>1 t/y) and mandatory registration for certain polymers (PRR). |

| Mixture Assessment [12] | Introduction of a Mixture Assessment Factor (MAF) for substances >1000 t/y. |

| Digital Communication [12] | Shift to digital Safety Data Sheets and alignment with the Digital Product Passport (DPP). |

| Enforcement [12] | Strengthened market surveillance and customs controls. |

Experimental Protocols for Green Chemistry Scaling

This section provides methodologies inspired by award-winning green chemistry processes, demonstrating how to integrate sustainability and regulatory foresight into research and development.

Protocol 1: Developing a Multi-Enzyme Biocatalytic Cascade

Inspired by Merck's Green Chemistry Award-winning process for Islatravir [13].

1. Objective To design a single, aqueous enzymatic cascade process that converts a simple achiral starting material into a complex target molecule, eliminating the need for intermediate isolation, organic solvents, and reducing synthetic steps.

2. Principle Chemical cascade reactions execute multiple sequential transformations without isolating intermediates, enhancing efficiency and reducing waste. Advances in protein engineering enable the design of artificial biosynthetic pathways that achieve significant jumps in molecular complexity in one reaction vessel [13].

3. Materials and Methodology

- Enzyme Selection & Engineering: In collaboration with protein engineering specialists (e.g., Codexis), select and engineer nine enzymes to catalyze the specific sequential reactions. This includes engineering for high activity, specificity, and stability under shared reaction conditions.

- Reaction Setup:

- Reaction Vessel: Single, temperature-controlled bioreactor.

- Solvent: Pure aqueous buffer, pH optimized for the entire enzyme set.

- Feedstock: Simple achiral substrate (e.g., glycerol).

- Process: Add substrate and all nine enzymes to the single vessel. Monitor reaction progression analytically (e.g., HPLC, LC-MS). The process requires no workups or isolations until the final product is obtained.

- Scale-Up: Demonstrate the process on a 100 kg scale to prove commercial viability [13].

4. Key Regulatory & Sustainability Considerations

- Waste Reduction: The process replaces a traditional 16-step synthesis, drastically reducing waste and energy consumption [13].

- Solvent Use: Eliminates the use of organic solvents, aligning with green chemistry principles and reducing workplace exposure and environmental release.

Protocol 2: Implementing Air-Stable Nickel Catalysis

Inspired by the work of Prof. Keary M. Engle (Scripps Research) on Air-Stable Nickel(0) Catalysts [13].

1. Objective To utilize air-stable nickel precatalysts for cross-coupling reactions, enabling practical and scalable synthesis while reducing reliance on precious metals like palladium and avoiding energy-intensive inert-atmosphere storage.

2. Principle Nickel is a low-cost, abundant, and sustainable alternative to precious metals. Traditional nickel catalysts are air-sensitive, requiring complex handling. Novel ligand designs have created nickel complexes that are stable under ambient conditions but can be activated under standard reaction conditions to generate highly active Ni(0) species [13].

3. Materials and Methodology

- Catalyst System: Air-stable nickel precatalysts (e.g., Engle's catalysts).

- Reaction Setup:

- Handling: Weigh and handle catalysts on the benchtop without a glovebox.

- Activation: The stable precatalysts are activated in the reaction vessel to generate the active Ni(0) species, facilitating a broad array of carbon-carbon and carbon-heteroatom bond formations.

- Safety: An alternative electrochemical synthesis route for catalyst preparation is available, which avoids excess flammable reagents and offers a safer, more efficient pathway [13].

- Application: Applicable for synthesizing complex molecules for pharmaceuticals and advanced materials, often rivaling or outperforming palladium-based systems [13].

4. Key Regulatory & Sustainability Considerations

- Safer Processes: Reduces process safety risks associated with pyrophoric catalysts and inert atmosphere storage.

- Critical Raw Materials: Contributes to reducing dependence on critical and expensive precious metals, enhancing supply chain resilience.

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

REACH Substance Assessment Workflow

Green Chemistry R&D and Regulatory Integration

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Key materials and tools for developing compliant green chemistry processes.

| Item / Solution | Function in Research & Development | Relevance to Green Chemistry & Regulatory Compliance |

|---|---|---|

| Bio-Based Feedstocks (e.g., plant-derived sugars, algal oils) | Renewable starting material for synthesis, replacing fossil-based feedstocks [13] [14]. | Reduces carbon footprint and fossil dependency; aligns with EU Green Deal goals for a circular bio-economy. |

| Non-PFAS Surfactants (e.g., SoyFoam) | Fire suppression foam or surfactant for various formulations [13]. | Provides a safer alternative to PFAS, which are under severe restriction, eliminating environmental and health concerns [13] [12]. |

| Engineered Enzymes | Highly specific biocatalysts for synthesis, often used in cascades [13]. | Enable milder reaction conditions (aqueous, ambient T&P), reduce waste, and are biodegradable. Key for designing novel, sustainable pathways. |

| Earth-Abundant Metal Catalysts (e.g., Air-stable Ni complexes) | Catalyze key bond-forming reactions (e.g., cross-couplings) [13]. | Replaces expensive, scarce precious metals (e.g., Pd, Pt); air-stability enhances safety and practicality for industrial use. |

| Digital Chemistry & AI Platforms | Accelerate material discovery, reaction optimization, and predict properties [15]. | Cuts R&D cycles, helps identify safer chemicals by design, and aids in predicting regulatory triggers (e.g., toxicity). |

| Chemical Recycling Technologies | Converts plastic waste back into monomers for new polymers [15] [14]. | Creates circular feedstock, addresses plastic waste, and helps meet recycled content mandates under EU policies. |

The global green chemistry market, valued at USD 113.1 billion in 2024, is projected to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 10.9% to reach USD 292.3 billion by 2034 [16]. This growth is not merely an environmental trend but a fundamental business transformation. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, green chemistry has evolved from a theoretical ideal to a practical framework delivering measurable cost savings, enhanced investor appeal, and substantial brand value. This technical support center provides actionable guidance for overcoming the specific experimental and scaling challenges inherent in implementing green chemistry principles within industrial contexts, particularly for fine chemical and pharmaceutical production where traditional processes often generate 50-100 times more waste than product [17].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting Guides

Q1: How can we quantitatively demonstrate that a new green chemistry process is superior to our existing method?

When proposing a new green synthesis pathway, you must demonstrate its advantages through standardized metrics. The following quantitative metrics provide a comprehensive assessment framework [18].

- Troubleshooting Tip: If your Atom Economy is low, investigate if a key starting material is ending up in a byproduct. Consider strategic bond formation to incorporate more atoms into the final product.

- Troubleshooting Tip: A high E-factor often points to solvent-intensive steps. Focus on solvent recovery or replacement with greener alternatives to dramatically improve this metric.

Table 1: Key Green Chemistry Metrics for Process Evaluation

| Metric | Formula / Definition | Target Value | Common Pitfall & Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atom Economy (AE) | (MW of Desired Product / Σ MW of All Reactants) x 100 | >70% considered good [18] | Pitfall: Use of stoichiometric reagents. Solution: Shift to catalytic reactions [17]. |

| E-Factor | Total Mass of Waste (kg) / Mass of Product (kg) | <5 for specialties; <20 for pharmaceuticals [17] | Pitfall: High solvent usage. Solution: Implement solvent recovery or switch to aqueous systems [6]. |

| Process Mass Intensity (PMI) | Total Mass Input (kg) / Mass of Product (kg) | Aim for a 50% reduction from baseline | Pitfall: Hidden water/energy mass. Solution: Use PMI for a full resource accounting. |

| Reaction Mass Efficiency (RME) | (Mass of Product / Σ Mass of Reactants) x 100 | Higher is better; up to 100% ideal | Pitfall: Low yield or purity. Solution: Optimize catalysis and work-up procedures. |

Q2: Our biocatalysis experiment failed to achieve the expected yield. What are the common points of failure?

Biocatalysis, while powerful, can be sensitive. The workflow below outlines a standard experimental protocol and key troubleshooting points for using enzymes in synthesis [17].

Diagram: Biocatalysis Experimental Workflow and Troubleshooting

Experimental Protocol: Biocatalytic Synthesis of a Chiral Amine Intermediate [17]

- Reaction Setup: In a 50 mL round-bottom flask equipped with a magnetic stir bar, charge 20 mL of 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5).

- Substrate Addition: Add 1.0 mmol of your prochiral ketone substrate. (Note: If substrate solubility is low, consider minimal amounts of a co-solvent like 2-5% DMSO or tert-butanol).

- Enzyme & Cofactor Addition: Add 1.0 mmol of an amino donor (e.g., isopropylamine) and 20 mg of the transaminase enzyme (e.g., the engineered enzyme used in Sitagliptin synthesis). Add 0.1 mmol of Pyridoxal-5'-phosphate (PLP) as a cofactor.

- Reaction Execution: Stir the reaction mixture at 30°C and monitor by TLC or LC-MS until completion (typically 4-24 hours).

- Work-up: Once complete, extract the product with ethyl acetate (3 x 15 mL). Combine the organic layers, dry over anhydrous MgSO₄, filter, and concentrate under reduced pressure.

- Purification & Analysis: Purify the crude product by flash chromatography. Analyze the yield and enantiomeric excess (ee) by chiral HPLC or GC.

Q3: How can we effectively replace hazardous solvents in our reaction without compromising efficiency?

Replacing hazardous solvents is a core principle of green chemistry. The following table lists common problematic solvents and their greener alternatives, along with key considerations for researchers [6] [17].

Table 2: Solvent Replacement Guide for Safer Synthesis

| Hazardous Solvent | Green Alternative(s) | Key Experimental Considerations | Industrial Scaling Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dichloromethane (DMC) | 2-Methyltetrahydrofuran (2-MeTHF), Cyclopentyl methyl ether (CPME) | - 2-MeTHF is derived from renewable resources but has a higher boiling point. - Both form a separate aqueous phase for easy work-up. | Excellent for direct drop-in replacement in extraction processes. |

| N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF) | N-Butylpyrrolidinone (NBP), Polarclean, Water [6] | - NBP is less toxic but viscous; may require longer reaction times. - Water is ideal for "on-water" reactions where reactants are insoluble [6]. | Facilitates solvent recovery due to high boiling point; reduces VOC emissions. |

| Tetrahydrofuran (THF) | 2-MeTHF, Cymene, Diethyl carbonate | - 2-MeTHF provides better water separation. - Cymene is bio-based but highly flammable. | Check stability of Grignard and other organometallic reagents in new solvents. |

| Hexanes (n-Hexane) | Heptane, Toluene, Ethyl Acetate | - Heptane is less toxic but still flammable. - Ethyl Acetate offers higher polarity and biodegradability. | Heptane is often preferred in industry due to similar properties and safer toxicological profile. |

| Benzene | Toluene, Xylenes | - Toluene is the standard, less toxic replacement for aromaticity. | A classic example of safer chemical design, though still hazardous. |

Q4: Our management is concerned about the high upfront cost of transitioning to green processes. What is the financial argument?

The business case extends beyond compliance to tangible financial returns, as seen in the table below [19] [17].

Table 3: The Business Case: Cost Savings and Value Creation of Green Chemistry

| Cost Category | Traditional Chemistry | Green Chemistry Application | Financial Outcome & Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Waste Disposal | High (E-factor often >100 in pharma) | Waste prevention at source, lower E-factor. | Direct Savings: Merck's Sitagliptin process redesign reduced waste by 19% and eliminated a genotoxic waste stream [17]. |

| Raw Materials | Linear use of fossil-based feedstocks. | Use of catalytic vs. stoichiometric reagents; renewable feedstocks. | Efficiency: Catalysis uses sub-stoichiometric amounts, reducing reagent costs. Atom economy maximizes material use [18] [17]. |

| Energy Consumption | High-temperature/pressure reactions. | Reactions at ambient conditions (e.g., biocatalysis). | Reduced OPEX: Biocatalytic steps can reduce process energy consumption by 80-90% by operating at room temperature [17]. |

| Regulatory & Liability | High costs for handling and permitting hazardous materials. | Inherently safer processes and products. | Risk Mitigation: Avoiding toxic reagents like phosgene reduces potential liability, insurance costs, and future cleanup expenses [6] [17]. |

| Brand & Market Value | Increasingly scrutinized for environmental impact. | Market leadership in sustainability. | Premium Positioning: Companies like Unilever and P&G leverage bio-based formulations to enhance brand loyalty and access new markets [17]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

For researchers designing green chemistry experiments, especially in biomass valorization and catalysis, the following reagents and materials are critical [18] [6] [17].

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Green Chemistry

| Reagent / Material | Function in Green Chemistry | Example Application | Notes for Researchers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sn-based Zeolites (e.g., K–Sn–H–Y-30) | Lewis acid catalyst for selective epoxidation. | Epoxidation of limonene for biomass valorization [18]. | Highly selective, reducing byproduct formation. Can be reused and regenerated. |

| Transaminase Enzymes | Biocatalyst for chiral amine synthesis. | Production of chiral amine intermediates, as in Sitagliptin API [17]. | Requires PLP cofactor. Enzyme engineering often needed for optimal activity and stability. |

| Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) | Customizable, biodegradable solvents for extraction. | Extraction of metals from e-waste or polyphenols from biomass [6]. | Typically a mixture of a hydrogen bond acceptor (e.g., Choline Chloride) and donor (e.g., Urea). |

| Dendritic Zeolites (e.g., d-ZSM-5) | Catalyst with improved diffusion and reduced coking. | Synthesis of dihydrocarvone from limonene epoxide [18]. | Excellent for bulky molecules, offering high RME and atom economy. |

| Silver Nanoparticles (in Water) | Catalyst for reactions in aqueous medium. | Plasma-driven electrochemical synthesis in water [6]. | Enables "on-water" catalysis, eliminating need for organic solvents. |

| Iron Nitride (FeN) / Tetrataenite (FeNi) | Rare-earth-free permanent magnets. | Used in motors and generators for a sustainable supply chain [6]. | A green chemistry solution for the materials themselves, not just the process. |

Transitioning green chemistry principles from laboratory research to industrial-scale manufacturing presents unique challenges. This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals overcome common barriers in scaling sustainable chemical processes. The guidance is framed within the context of a broader thesis on industrial scaling challenges, focusing on practical implementation of the 12 principles established by Paul Anastas and John Warner [20] [17].

Foundational Principles and Industrial Metrics

The 12 Principles of Green Chemistry

The foundational principles of green chemistry provide a systematic framework for designing and evaluating chemical processes with reduced environmental impact. The table below outlines these principles and their industrial significance [20] [17].

Table 1: The 12 Principles of Green Chemistry and Their Industrial Application

| Principle Number | Principle Name | Core Concept | Industrial Impact & Scaling Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Prevention | Prevent waste rather than treat or clean up waste after it is formed. | Eliminates end-of-pipe waste management costs; requires process redesign. |

| 2 | Atom Economy | Maximize the incorporation of all starting materials into the final product. | Reduces raw material consumption and waste; high atom economy processes are often more cost-effective at scale. |

| 3 | Less Hazardous Chemical Syntheses | Wherever practicable, synthetic methods should be designed to use and generate substances that possess little or no toxicity to human health and the environment. | Protects worker safety, reduces regulatory burdens, and minimizes liability. |

| 4 | Designing Safer Chemicals | Chemical products should be designed to preserve efficacy of function while reducing toxicity. | Creates safer end-products but may require re-evaluation of product performance and market acceptance. |

| 5 | Safer Solvents and Auxiliaries | The use of auxiliary substances (e.g., solvents, separation agents) should be made unnecessary wherever possible and innocuous when used. | Reduces VOC emissions, solvent recovery costs, and fire hazards. A major focus area for scaling. |

| 6 | Design for Energy Efficiency | Energy requirements of chemical processes should be recognized for their environmental and economic impacts and should be minimized. | Reactions at ambient temperature and pressure significantly reduce operational costs at scale. |

| 7 | Use of Renewable Feedstocks | A raw material or feedstock should be renewable rather than depleting whenever technically and economically practicable. | Reduces dependence on fossil fuels; requires development of new, resilient supply chains. |

| 8 | Reduce Derivatives | Unnecessary derivatization (use of blocking groups, protection/deprotection, temporary modification of physical/chemical processes) should be minimized or avoided if possible. | Fewer synthesis steps reduce material, energy, and time inputs, simplifying scale-up. |

| 9 | Catalysis | Catalytic reagents (as selective as possible) are superior to stoichiometric reagents. | Catalysis reduces reagent quantities and waste; biocatalysts often operate under milder conditions. |

| 10 | Design for Degradation | Chemical products should be designed so that at the end of their function they break down into innocuous degradation products and do not persist in the environment. | Crucial for preventing long-term pollution (e.g., PFAS); may conflict with product durability requirements. |

| 11 | Real-time Analysis for Pollution Prevention | Analytical methodologies need to be further developed to allow for real-time, in-process monitoring and control prior to the formation of hazardous substances. | Requires capital investment in PAT (Process Analytical Technology) but enables superior process control. |

| 12 | Inherently Safer Chemistry for Accident Prevention | Substances and the form of a substance used in a chemical process should be chosen to minimize the potential for chemical accidents, including releases, explosions, and fires. | Inherent safety (vs. added-on controls) protects facilities and communities, a critical ethical and business consideration. |

Quantitative Metrics for Success

Measuring the environmental and economic benefits of green chemistry is essential for validating investments and guiding process optimization. The following table summarizes key performance indicators used in industry [17].

Table 2: Key Quantitative Metrics for Green Chemistry at Scale

| Metric | What It Measures | Calculation | Target Values for Industrial Processes |

|---|---|---|---|

| E-factor | Mass of waste generated per mass of product. | Total waste (kg) / Product (kg) | <5 for specialty chemicals, <20 for pharmaceuticals [17] |

| Atom Economy | Efficiency of incorporating starting atoms into the final product. | (MW of Product / Σ MW of Reactants) x 100% | >70% is considered good [20] [17] |

| Process Mass Intensity (PMI) | Total mass of materials used per mass of product. | Total mass input (kg) / Product (kg) | A lower PMI is better; <20 is a target for pharmaceuticals [17] |

| Solvent Intensity | Mass of solvent used per mass of product. | Total solvent mass (kg) / Product (kg) | <10 is a common industrial target [17] |

Troubleshooting Common Scaling Challenges

FAQ 1: How can we reduce or eliminate hazardous solvents in an industrial process, and what are the common pitfalls?

Challenge: Traditional organic solvents are often volatile, toxic, and account for a significant portion of the PMI and waste in chemical manufacturing [6] [17].

Solutions & Protocols:

- Evaluate Safer Alternative Solvents: Use solvent selection guides (e.g., like those pioneered by GSK) that rank solvents based on environmental, health, and safety criteria. Prefer water, bio-based solvents (e.g., limonene from citrus peel waste), or deep eutectic solvents (DES) [6] [17].

- Implement Solvent-Free Synthesis: Investigate mechanochemistry, which uses mechanical force (e.g., ball milling) to drive reactions without solvents. This technique is scalable for pharmaceuticals and advanced materials [6].

- Experimental Protocol for Mechanochemistry: Charge reactants and a catalytic amount of an inert grinding auxiliary (e.g., NaCl) into a high-energy ball mill. Seal the mill and operate at optimized frequency and time. After reaction, the product can often be isolated simply by washing away the auxiliary with water [6].

- Utilize Aqueous Systems: Develop "on-water" or "in-water" reactions where water's unique properties (hydrogen bonding, high surface tension) can accelerate reactions, even for water-insoluble reactants [6].

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Problem: Reaction yield drops significantly with a green solvent.

- Solution: Re-optimize reaction parameters (temperature, concentration, catalyst) specifically for the new solvent system; do not assume conditions from the old solvent will translate.

- Problem: Solvent-free method leads to poor heat transfer or agglomeration at scale.

- Solution: Use specialized industrial-scale mechanochemical reactors designed for continuous operation and efficient heat dissipation [6].

FAQ 2: Our process relies on rare earth elements or precious metal catalysts. How can we design a more sustainable and cost-effective catalytic system?

Challenge: The use of scarce, expensive, or geographically concentrated elements (e.g., palladium, rare earths) creates supply chain risks and environmental damage from mining [6] [13].

Solutions & Protocols:

- Replace with Earth-Abundant Alternatives: Develop catalysts based on nickel, iron, or copper. For example, air-stable nickel(0) catalysts have been developed for cross-coupling reactions, replacing more expensive palladium catalysts and eliminating the need for energy-intensive inert-atmosphere handling [13].

- Implement Biocatalysis: Use engineered enzymes as highly selective catalysts. They operate in water at ambient temperatures, exemplifying multiple green principles [13] [17].

- Experimental Protocol for Biocatalyst Screening: Identify the target transformation. Screen commercial enzyme libraries or engineer enzymes via directed evolution for the desired activity. Optimize reaction conditions (pH, temperature, co-solvent tolerance) in a high-throughput microplate format. Scale up the most promising biocatalyst in a bioreactor with controlled feeding and pH [13].

- Design for Catalyst Recovery and Reuse: Immobilize heterogeneous catalysts on solid supports to facilitate easy filtration and recycling, improving atom economy and reducing costs.

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Problem: Nickel catalyst shows lower activity than palladium.

- Problem: Enzyme deactivates under process conditions.

- Solution: Use protein engineering to improve enzyme stability or employ whole-cell biocatalysis where the cellular environment offers native protection [13].

FAQ 3: How can we improve atom economy and reduce derivatives in a multi-step pharmaceutical synthesis?

Challenge: Complex molecule synthesis often involves protecting groups and derivatization, leading to additional steps, reagents, and waste [13] [17].

Solutions & Protocols:

- Adopt Convergent Synthesis: Design synthetic routes that build complex molecules from smaller, advanced intermediates in parallel, rather than long linear sequences.

- Utilize Tandem/Cascade Reactions: Combine multiple bond-forming steps in a single reactor without isolating intermediates. This dramatically reduces PMI and processing time.

- Experimental Protocol for a Biocatalytic Cascade: The synthesis of Islatravir at Merck is a landmark example. A single reaction vessel containing nine engineered enzymes converts a simple achiral starting material directly into the complex antiviral drug in an aqueous stream, replacing a 16-step clinical route [13].

- Employ C-H Activation: Develop synthetic steps that functionalize C-H bonds directly, avoiding the need to install and then remove functional groups like halides or boronic esters (which are typical derivatives).

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Problem: Intermediate in a cascade reaction inhibits a subsequent enzyme.

- Solution: Engineer enzymes for higher tolerance or adjust the reaction conditions (e.g., flow chemistry) to spatially separate the steps while maintaining a continuous process [13].

- Problem: Convergent synthesis leads to a difficult final coupling step with low yield.

- Solution: Re-evaluate the disconnection strategy or develop a more robust catalytic system for the key coupling reaction.

Workflow Visualization for Process Optimization

The following diagram illustrates a systematic workflow for redesigning an industrial chemical process using green chemistry principles.

Diagram 1: Green Chemistry Process Optimization Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

This table details essential reagents and materials that enable the implementation of green chemistry at scale.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Green Chemistry

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Application | Key Green Chemistry Principle |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) | Customizable, biodegradable solvents for extraction and synthesis. | Extraction of metals from e-waste or bioactive compounds from biomass [6]. | Safer Solvents and Auxiliaries, Use of Renewable Feedstocks. |

| Engineered Enzymes (Biocatalysts) | Highly selective biological catalysts for specific bond-forming reactions. | Synthesis of chiral amines in pharmaceuticals (e.g., Sitagliptin) [17]. | Catalysis, Less Hazardous Synthesis, Energy Efficiency. |

| Air-Stable Nickel Complexes | Earth-abundant alternative to precious metal catalysts for coupling reactions. | Cross-coupling reactions to form C-C and C-heteroatom bonds [13]. | Catalysis, Reducing Derivatives, Design for Energy Efficiency. |

| Iron/Nickel Alloys (e.g., Tetrataenite) | Earth-abundant elements for high-performance permanent magnets. | Replacing rare-earth magnets in electric vehicle motors and wind turbines [6]. | Use of Renewable Feedstocks, Design for Degradation. |

| Bio-based Surfactants (e.g., Rhamnolipids) | Renewable, biodegradable surfactants and emulsifiers. | Replacing PFAS-based fume suppressants in metal plating or in personal care products [6] [21]. | Designing Safer Chemicals, Design for Degradation. |

| Choline Chloride | A common, non-toxic component (HBA) for formulating Deep Eutectic Solvents. | Mixed with hydrogen bond donors (e.g., urea, acids) to create low-melting-point solvents [6]. | Safer Solvents and Auxiliaries. |

Green Chemistry in Action: Scalable Technologies and Industrial Case Studies

The transition to safer, more sustainable solvents is a critical pillar of green chemistry, driven by significant environmental, health, and regulatory pressures. Traditional solvents such as per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), N-Methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP), and Dimethylformamide (DMF) are under increased scrutiny due to their persistence, toxicity, and associated health risks. This technical support center is designed to assist researchers and scientists in navigating the practical challenges of replacing these hazardous substances with safer alternatives, within the broader context of scaling green chemistry processes for industrial application. The movement is gaining substantial momentum; for instance, the Change Chemistry community is mobilizing to make 2025 the "Year of Safe and Sustainable Solvents," highlighting the critical need to transition away from petrochemically-derived solvents that pose risks of carcinogenicity, neurotoxicity, and reproductive toxicity [22].

FAQs: Common Questions on Solvent Substitution

Q1: Why is there such a strong push to replace PFAS, NMP, and DMF?

The push is due to a combination of their hazardous profiles and increasing global regulations. PFAS are known as "forever chemicals" because they do not easily degrade in the environment or the human body, and have been linked to hormonal disruption, immune system effects, and certain cancers [23]. NMP is highly toxic, with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) concluding it poses an unreasonable risk to human health [24]. The European Commission has also restricted its use [24]. Similarly, DMF is classified as a hazardous airborne pollutant and is toxic [25]. Regulatory actions from REACH in the EU and TSCA in the US are making the use of these substances increasingly difficult and costly.

Q2: What are the key principles for selecting a safer alternative solvent?

When selecting a safer solvent, consider the following principles, which align with the 12 Principles of Green Chemistry:

- Reduce Hazard: Choose solvents with lower toxicity, lower volatility, and higher flash points to improve worker safety and process safety [26].

- Minimize Environmental Impact: Prefer solvents that are readily biodegradable, not persistent, and have low bioaccumulation potential.

- Consider Life Cycle & Renewability: Opt for solvents derived from renewable, biobased feedstocks rather than finite petrochemicals where possible [25].

- Ensure Functionality: The alternative must still meet the technical performance requirements of the reaction or process, such as solubility, polarity, and boiling point.

Q3: I'm working with fluoropolymers. What are my options?

High-performance polymers like PEEK (polyether ether ketone) and PPS (polyphenylene sulfide) are leading PFAS-free alternatives. PEEK is renowned for its strength, chemical resistance, and thermal stability, making it suitable for medical implants and aerospace components [23]. PPS is also thermally stable with a melting point above 280°C and offers excellent mechanical strength, making it a viable option for automotive and electronics applications through techniques like 3D printing [23].

Q4: Are there any drop-in green alternatives for chromatography using dichloromethane (DCM)?

Yes, significant progress has been made. Research indicates that mixtures of ethyl acetate and heptane or ethyl acetate and alcohol (like ethanol) can achieve similar eluting strengths to DCM in chromatographic purification [25]. These mixtures are less toxic and hazardous, offering a greener profile without major compromises to the chromatography.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

Problem: Poor Solubility or Performance with New Binder-Solvent Systems

- Scenario: When replacing NMP/PVDF in lithium-ion battery cathode slurry, the new binder does not dissolve properly or the slurry has poor rheology.

- Solution: Systematically check solvent-binder compatibility using solubility parameters. Not all "green" dipolar aprotic solvents dissolve all binders effectively at room temperature [24]. For example, while NMP and DMF dissolve PVDF, other alternatives like Cyrene or GVL may not. Always consult solubility parameter data and perform small-scale compatibility tests before scaling up.

Problem: Slow Removal of High-Boiling Point Solvents

- Scenario: The replacement solvent (e.g., DMSO, DMF) has a high boiling point, leading to long, energy-intensive evaporation times and potential thermal decomposition of heat-sensitive products.

- Solution: Implement more efficient evaporation technologies. The Vacuum Vortex Concentration (VVC) method, used in tools like the Smart Evaporator, generates a spiral airflow that increases the liquid's surface area, enabling faster and gentler solvent removal. This method is particularly effective for removing DMSO and DMF during polymer synthesis and can prevent issues like solvent bumping [23].

Problem: Maintaining Nanoparticle Dispersion or Aerogel Porosity

- Scenario: Switching to an alternative solvent disrupts the delicate microstructure of nanocomposites or aerogels during drying.

- Solution: Employ gentle drying techniques under controlled low pressure and temperature. The VVC method is also a powerful complement to supercritical drying and solvent exchange processes, as it helps preserve fine microstructures by avoiding harsh drying conditions [23].

Research Reagent Solutions: A Toolkit for the Modern Lab

The table below summarizes key hazardous solvents and their promising alternatives to guide your experimental planning.

Table 1: Solvent Replacement Guide for Common Hazardous Chemicals

| Solvent | Common Uses | Key Issues | Safer Replacements |

|---|---|---|---|

| PFAS (e.g., PTFE, PFA) | Non-stick coatings, high-performance polymers | Persistent "forever chemicals", bioaccumulative, health risks | PEEK, PPS [23], SoyFoam (for firefighting) [13] |

| NMP | Cathode slurry in Li-ion batteries, solvent for resins | Reproductive toxicity, high boiling point, regulated under REACH & TSCA [24] | Cyrene, Dimethyl Isosorbide (DMI), γ-Valerolactone (GVL), aqueous binders [24] |

| DMF | Reaction solvent, polymer processing | Hazardous airborne pollutant, toxic, carcinogen [25] | Acetonitrile, Cyrene, GVL, Dimethyl Isosorbide (DMI) [25] |

| Dichloromethane (DCM) | Extraction, chromatography | Hazardous airborne pollutant, carcinogen [25] | Ethyl acetate/heptane mixtures, MTBE, Toluene, 2-MeTHF [25] |

| n-Hexane | Extraction | Reproductive toxicant, more toxic than alternatives [25] | Heptane [25] |

| Diethyl Ether | Solvent, reagent | Very low flash point, peroxide former [25] | tert-butyl methyl ether, 2-MeTHF [25] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Transitions

Protocol: Transitioning from NMP/PVDF to Aqueous Binder Systems for Li-Ion Battery Electrodes

Objective: To formulate a cathode slurry using an aqueous binder system instead of the traditional NMP/PVDF combination. Background: Replacing NMP/PVDF is critical for reducing toxicity and energy consumption in battery manufacturing [24]. Materials: Active cathode material (e.g., LiNiMnCoO₂), conductive carbon additive, aqueous binder (e.g., cellulose-based, styrene-butadiene rubber (SBR)), deionized water. Methodology:

- Binder Solution Preparation: Dissolve the selected aqueous binder in deionized water under moderate stirring to form a homogeneous solution. Note that the solution viscosity may differ significantly from PVDF in NMP.

- Slurry Formulation: Gradually add the conductive carbon additive to the binder solution under high-shear mixing to ensure complete dispersion and break up agglomerates.

- Addition of Active Material: Introduce the active cathode material to the mixture in stages. Continue high-shear mixing until a homogeneous slurry with the desired viscosity and solid content is achieved.

- Coating and Drying: Coat the slurry onto an aluminum current collector. Use an oven at a moderate temperature (e.g., 80-120°C) to dry the electrode. Note that water evaporation is more energy-efficient than NMP removal.

- Calendering: Calender the dried electrode to the desired porosity and density. Troubleshooting: If slurry viscosity is too high, adjust the water content or optimize the mixing sequence. If adhesion is poor, evaluate different binder types or consider cross-linking strategies [24].

Protocol: Evaluating Green Solvents for Polymer Synthesis and Processing

Objective: To assess the efficiency of green solvents like Cyrene or GVL in dissolving polymers and facilitating reactions compared to DMF. Background: Solvents like Cyrene (dihydrolevoglucosenone) are derived from biomass and offer a safer profile than traditional dipolar aprotic solvents [6]. Materials: Target polymer (e.g., PVDF, cellulose), candidate green solvents (Cyrene, GVL, DMI), traditional solvent (DMF for comparison), magnetic stirrer, heating mantle. Methodology:

- Qualitative Solubility Test: Place a small, measured mass of the polymer into separate vials containing each solvent.

- Dissolution Monitoring: Stir the mixtures at room temperature and record observations. If dissolution is incomplete, gradually increase the temperature in controlled steps (e.g., 40°C, 60°C), noting the temperature at which complete dissolution occurs.

- Solution Stability: Once dissolved, hold the solutions at room temperature for 24 hours to check for any polymer precipitation or gelation.

- Performance Benchmarking: Use the successful solvent-polymer systems in a model reaction or casting process and compare the yield, reaction rate, or final material properties against the benchmark system using DMF. Troubleshooting: If a green solvent does not dissolve the polymer, investigate co-solvent systems or other alternative solvents from Table 1. Always check the chemical stability of the green solvent under your reaction conditions, as some may be sensitive to strong acids, bases, or high temperatures.

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

Decision Pathway for Solvent Replacement

The following diagram outlines a logical, step-by-step workflow for selecting a safer alternative solvent.

Decision Pathway for Solvent Replacement

NMP/PVDF Replacement Workflow in Li-ion Batteries

This diagram details the specific technical workflow for replacing NMP and PVDF in lithium-ion battery cathode manufacturing, highlighting two parallel strategies.

NMP/PVDF Replacement Workflow in Li-ion Batteries

Technical Troubleshooting Guide

This section addresses common experimental challenges in biocatalysis for drug synthesis, providing evidence-based solutions to improve process robustness and reproducibility.

Q1: My immobilized enzyme shows a significant drop in activity after just a few reaction cycles. What could be causing this?

- Potential Cause #1: Uncontrolled enzyme orientation on the support material leading to multipoint covalent attachment in a suboptimal configuration that distorts the active site [27].

- Solution: Implement site-specific immobilization techniques using engineered tags (e.g., His-tag) or bio-orthogonal chemistry to ensure a uniform and favorable orientation [27].

- Potential Cause #2: Enzyme denaturation due to shear forces, gas bubbles, or harsh reaction conditions in the reactor [28].

- Solution: Optimize process parameters such as stirring rate and flow velocity. Consider using more robust enzymes obtained through directed evolution or engineering the microenvironment with hydrophilic polymers post-immobilization to enhance stability [29].

- Potential Cause #3: Poor mass transfer limitations, where substrates cannot efficiently reach the enzyme's active site within a densely packed support [27].

Q2: I am trying to reproduce a published biocatalytic reaction, but my yields are much lower. Where should I focus my troubleshooting?

- Potential Cause #1: Differences in enzyme formulation and preparation between your lab and the published method significantly impact activity [32].

- Solution: Scrutinize the enzyme preparation details. If using a commercially available enzyme, ensure it matches the supplier and purity. If producing it in-house, carefully control the expression host, promoter system, fermentation conditions, and downstream processing (e.g., lyophilized powder vs. cell paste) [32].

- Potential Cause #2: Inefficient cofactor recycling, which is critical for reactions using ketoreductases (KREDs) or other cofactor-dependent enzymes [33].

- Solution: Implement and optimize a cofactor recycling system. For example, use isopropanol as a sacrificial substrate for NAD(P)H regeneration. Ensure the system is efficient enough to avoid cofactor depletion being a bottleneck [33].

- Potential Cause #3: Substrate or product inhibition at concentrations higher than the enzyme's tolerance level [28].

Q3: The enzyme works well in aqueous buffer but fails when I introduce organic solvents to solubilize my substrates. How can I improve solvent tolerance?

- Potential Cause #1: The enzyme is denatured or inactivated by the organic solvent [34].

- Solution: (a) Screen for different water-miscible co-solvents (e.g., DMSO, methanol, DMF) or switch to a biphasic system using water-immiscible solvents. (b) Use enzyme engineering (directed evolution) to generate solvent-resistant variants [34]. (c) Immobilize the enzyme on a hydrophobic support, which can create a protective microenvironment and enhance stability in the presence of organic solvents [27] [29].

Q4: When I use a complex substrate mixture (e.g., a cell lysate), the enzyme's selectivity and efficiency change unpredictably. Why does this happen?

- Potential Cause: In a complex system with numerous competing substrates, classic Michaelis-Menten kinetics do not fully apply, which affects the observed reaction rates for individual components [35].

- Solution: Account for competitive binding in kinetic models. A simplified model states that the ratio of substrate depletion for two competing substrates, S1 and S2, is approximately equal to the ratio of their specificity constants

(k_cat/K_m)[35]. This understanding is crucial for predicting and interpreting enzyme behavior in complex matrices.

- Solution: Account for competitive binding in kinetic models. A simplified model states that the ratio of substrate depletion for two competing substrates, S1 and S2, is approximately equal to the ratio of their specificity constants

Table 1: Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) for Industrial Biocatalysis [33]

| Parameter | Desired Value (Industrial Target) | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Product Titer | >160 g/L | Indicates high volumetric productivity, reduces downstream processing costs. |

| Space-Time-Yield (STY) | >16 g/L/h | Measures reactor productivity; higher values mean smaller reactors. |

| Catalyst Loading | <1 g/L | Reflects catalytic efficiency; lower usage reduces enzyme cost contribution. |

| Turnover Number (TON) | As high as possible | Number of moles of product per mole of catalyst; indicates catalyst lifetime. |

| Enantiomeric Excess (%ee) | >99% | Critical for chiral drugs; ensures high stereoselectivity. |

Essential Experimental Protocols

Objective: To create a robust, recyclable biocatalyst by immobilizing a purified enzyme onto a pre-existing functionalized solid support.

Materials:

- Enzyme: Purified enzyme solution.

- Support: Porous solid support with reactive groups (e.g., epoxy-activated agarose, glyoxyl-agarose).

- Buffers: Coupling buffer (e.g., 100 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.0-8.5), washing buffer.

Method:

- Support Preparation: Hydrate the dry functionalized support in the chosen coupling buffer.

- Enzyme Binding: Incubate the enzyme solution with the prepared support under gentle agitation for 2-24 hours at a controlled temperature (e.g., 4-25°C).

- Blocking: After immobilization, remove the supernatant and incubate the support with a blocking agent (e.g., 1M ethanolamine, 1M glycine) to deactivate any remaining reactive groups.

- Washing: Wash the immobilized enzyme thoroughly with buffer and then with a buffer containing a high salt concentration (e.g., 1M NaCl) to remove any physic-adsorbed enzyme.

- Storage: The immobilized enzyme can be stored wet at 4°C or, for some preparations, lyophilized.

Troubleshooting:

- Low Activity Recovery: The enzyme may be immobilized in a conformation that blocks the active site. Try a different support with a different functional group or a spacer arm [27].

- Enzyme Leakage: Ensure thorough washing with high-salt buffer. If leakage persists, the immobilization method may not be stable, and a different strategy (e.g., cross-linking) should be considered [29].

Objective: To implement a continuous flow process using an immobilized enzyme for improved productivity and catalyst reusability.

Materials:

- Reactor: Empty column (e.g., glass or HPLC column).

- Pumps: Syringe pump or HPLC pump for precise fluid delivery.

- Immobilized Biocatalyst: The prepared immobilized enzyme from Protocol 2.1.

- Substrate Solution: Solution of substrate in a suitable buffer or buffer/solvent mixture.

Method:

- Packing the Reactor: Slurry the immobilized enzyme in a buffer and carefully pack it into the column to avoid air bubbles and ensure a uniform bed.

- System Setup: Connect the column to the pump and a back-pressure regulator (BPR). The BPR is essential to prevent outgassing and maintain consistent flow.

- Equilibration: Pass the reaction buffer through the column at the desired operational flow rate until the system is stabilized.

- Reaction: Switch the feed from buffer to the substrate solution. Collect the effluent from the outlet.

- Monitoring: Analyze the effluent for product formation and conversion over time to determine steady-state performance.

Troubleshooting:

- High Pressure Drop: The column may be clogged. Use supports with larger particle size or pre-filter the substrate solution. Ensure the immobilized enzyme particles are not too small [31].

- Decreasing Conversion Over Time: This indicates enzyme inactivation. The operational stability (half-life) of the biocatalyst under flow conditions must be determined. Process parameters like temperature and substrate concentration can be optimized to extend catalyst life [30] [31].

Diagram 1: Biocatalyst development workflow for industrial application.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: How do I decide between using a purified enzyme, an immobilized enzyme, or whole cells for my synthesis?

- A: The choice depends on the reaction and process needs [31]. Use purified enzymes for maximum specificity and to avoid side reactions, but be prepared for higher costs and potential instability. Choose immobilized enzymes when you need to recover and reuse the catalyst, especially in continuous flow processes, or when enhanced stability is required. Whole cells are advantageous when the enzyme is intracellular, unstable in isolation, or requires complex cofactor regeneration that the cell machinery provides. However, whole cells can present substrate/product diffusion barriers and cause side reactions from other enzymes in the cell [31].

Q: What are the biggest challenges in scaling up a biocatalytic reaction from the lab to production?

- A: The main challenges include [28] [33]:

- Achieving high substrate concentrations and space-time-yields to make the process economically viable.

- Ensuring long-term operational stability of the enzyme over many batches or continuous operation.

- Developing efficient downstream processing to isolate the product from the aqueous reaction mixture.

- The "concentration gap"—many academic reactions run at millimolar concentrations, while industrial processes require much higher concentrations, which can lead to issues with substrate solubility, inhibition, and enzyme stability.

Q: Is biocatalysis always a "green" alternative to traditional chemical synthesis?

- A: Biocatalysis has many attributes of green chemistry (mild conditions, water as a solvent, high selectivity), but its environmental impact must be quantified [28]. A full life-cycle assessment (LCA) is necessary to compare processes fairly. Factors like the energy and resources used to produce the enzyme, the waste generated in downstream processing, and the overall atom economy must be considered. While generally greener, "green claims" should be made cautiously and supported by data [28].

Q: How can I obtain a specific enzyme that is not available commercially?

- A: You have two primary pathways, often referred to as the "Buy or Build" models [32]:

- Buy Model: Procure the enzyme from a specialized biocatalysis supplier who may offer enzyme kits for screening or custom evolution services.

- Build Model: If you have in-house expertise, you can produce it recombinantly. This requires access to the gene sequence, molecular biology tools (PCR, cloning), and a suitable microbial host for expression. This model offers greater control and security of supply but requires significant investment [32].

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Biocatalytic Challenges

| Problem | Root Cause | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Low Enantioselectivity | Enzyme lacks specificity for target stereoisomer | Screen different enzyme homologs; use directed evolution to improve selectivity [33]. |

| Slow Reaction Rate | Sub-optimal reaction conditions (pH, T) or enzyme inhibition | Optimize buffer, temperature, use fed-batch addition; engineer enzyme to relieve inhibition [33]. |

| Enzyme Inactivation in Flow Reactor | Shear forces, gas bubbles, or clogging | Use robust immobilization; optimize flow parameters; include a debubbler; use larger support particles [31]. |

| Poor Solubility of Substrate | Hydrophobic API precursors in aqueous media | Introduce water-miscible cosolvents (e.g., DMSO); use a biphasic system; surfactant coating [34] [28]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for Biocatalysis Research

| Item | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Epoxy-Activated Agarose | A versatile support for irreversible covalent enzyme immobilization. | Forms very stable bonds; useful for enzyme stabilization via multipoint covalent attachment [29]. |

| Lyophilized Enzyme Powder | A stable, weighable enzyme formulation for storage and use as a reagent. | Preferred physical form for easy handling and long-term storage; activity can vary with formulation [32]. |

| Cofactor Recycling System (e.g., Isopropanol/ADH) | Regenerates expensive cofactors (NAD(P)H) in situ for oxidoreductases. | Crucial for making cofactor-dependent reactions economically feasible on a large scale [33]. |

| His-Tag & Metal Affinity Supports | Allows for site-specific, oriented immobilization and one-step purification. | Requires recombinant production of the enzyme with a polyhistidine tag; controls orientation on support [27]. |

| Packed-Bed Reactor (PBR) | A continuous flow reactor for use with immobilized enzymes. | Enhances productivity and enables easy catalyst reuse; minimizes mechanical shear on the enzyme [30] [31]. |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Continuous Flow Synthesis Troubleshooting

FAQ: How can I prevent clogging in my continuous flow reactor?

Clogging is a frequent challenge in continuous flow systems, particularly when handling suspensions or reactions involving solids formation. The table below summarizes common causes and solutions.

Table: Troubleshooting Clogging in Continuous Flow Reactors

| Cause of Clogging | Solution | Preventive Measure |

|---|---|---|

| Solid precipitation from solution | Increase solvent strength or temperature | Improve solute solubility through solvent screening |

| Particle aggregation in suspensions | Use a reactor with wider internal channels (>1 mm) | Incorporate in-line sonication or mixing elements |

| Heterogeneous catalyst packing | Repack column with smaller, more uniform particles | Use catalyst cartridges with appropriate frits |

Additional strategies include using tube-in-tube reactors for gaseous reagents, implementing periodic back-flushing routines, and employing in-line filters. For reactions known to form solids, consider switching to a continuous oscillating baffled reactor (COBR) design, which is less prone to fouling [36].

FAQ: My reaction yield in flow is lower than in batch. What should I check?

Discrepancies in yield between batch and flow setups often stem from imperfect translation of reaction conditions.

Table: Addressing Yield Reductions in Flow Chemistry

| Parameter | Investigation Method | Optimization Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Residence Time | Conduct residence time distribution (RTD) analysis | Systematically vary pump flow rates to find optimum |

| Mixing Efficiency | Use visualization or tracer studies | Use static mixers; increase flow rate for turbulence |

| Heat Transfer | Monitor temperature at various reactor points | Use a thermocouple; adjust jacket temperature |

| Mass Transfer | Determine mass transfer coefficients | Improve gas-liquid contactor design |

Ensuring adequate mixing is critical, especially in laminar flow regimes. Advanced strategies involve using computational fluid dynamics (CFD) for reactor design optimization, as noted in bioreactor scale-up studies [37]. Furthermore, verify that all materials of construction (e.g., Hastelloy, Teflon) are chemically compatible with your reaction mixture to avoid catalytic decomposition [36].

FAQ: How do I scale up a successful lab-scale flow reaction?

Scaling a flow process involves more than just increasing reactor volume. The preferred method is numbering-up (using multiple identical reactors in parallel) or scaling-out (increasing channel dimensions while maintaining key performance metrics).

Table: Scaling Up Continuous Flow Processes

| Scale-Up Approach | Principle | Advantage | Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|

| Numbering-Up | Parallel operation of identical microreactors | Preserves reaction performance & kinetics | Requires fluid distribution system |

| Scaling-Out | Increasing channel diameter/dimensions | Simpler manifold, fewer units | Potential for reduced heat/mass transfer |

Key enablers for successful scale-up include robust engineering design, interdisciplinary collaborations, and early engagement with business development experts to de-risk the process. A thorough Techno-Economic Analysis (TEA) and Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) at an early technology readiness level (TRL 3-4) are crucial for identifying potential economic and environmental bottlenecks [38].

Mechanochemistry Troubleshooting

FAQ: The reaction in my ball mill is inconsistent. How can I improve reproducibility?

Reproducibility in mechanochemical synthesis is highly dependent on tightly controlling several milling parameters.

Table: Ensuring Reproducibility in Mechanochemical Synthesis

| Variable | Impact on Reaction | Guideline for Control |

|---|---|---|

| Milling Speed | Influences energy input & reaction kinetics | Record and report in rpm or frequency (Hz) |

| Milling Time | Determines total energy dose | Optimize for complete conversion |

| Ball-to-Powder Mass Ratio | Affects impact frequency and energy | Typically between 10:1 and 50:1 |

| Number and Size of Balls | Alters energy distribution and shearing | Document the count, diameter, and material |

| Liquid or Additive Use | Can enable liquid-assisted grinding (LAG) | Precisely control stoichiometry and volume |

Using a commercial mill with programmable parameters is recommended over manually operated equipment. For critical reporting, the use of in-situ analytical techniques, such as Raman spectroscopy, can help monitor reaction progression in real-time [39].

FAQ: How do I handle temperature control during mechanochemical synthesis?

Temperature is a key but often overlooked parameter in mechanochemistry. Mechanical energy input is partially converted into heat, potentially leading to high temperatures.

- External Cooling: Always use a mill equipped with a robust cooling system, such as a built-in refrigeration unit or Peltier cooler, or circulate coolant through the milling jar walls.

- Process Control: Implement intermittent milling cycles (e.g., 5 minutes milling, 5 minutes rest) to allow heat dissipation.

- In-situ Monitoring: For advanced applications, use milling jars fitted with temperature sensors. Note that exothermic reactions can be more challenging to control in a ball mill than in a flow reactor [39].

FAQ: What is the best way to scale up a mechanochemical reaction from a small ball mill?

Scaling mechanochemistry from lab-scale (e.g., a few grams) to industrial production presents a significant challenge. Simply using a larger mill often leads to different energy profiles and inefficient heat removal.

- Horizontal Ball Mills and Twin-Screw Extrusion: These are promising technologies for larger-scale mechanochemical synthesis. The synthesis of paracetamol using bead milling technology demonstrates the potential for greener, scalable mechanochemical processes [39].

- Process Intensification Domains: Mechanochemistry aligns with the functional (synergy) and thermodynamic (energy) domains of intensification by combining operations and using alternative energy inputs [40].

- Key Consideration: Scalability should be a design criterion from the earliest stages of research. This involves interdisciplinary collaborations and partnerships focused on moving technology from the lab to the market [38].

Quantitative Data for Process Design

This section provides consolidated quantitative data to inform the design and scaling of intensified processes.

Table: Comparative Analysis of Process Intensification Technologies

| Technology | Reported Energy Saving | Scale-Up Reduction Factor | Key Limitation | Primary Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous Flow Reactors | Up to 80% [40] | Equipment size reduced up to 100x [40] | Clogging with solids | API synthesis [41] |

| Mechanochemistry | Significant reduction vs. thermal pathways [42] | N/A (Challenges in scaling) [39] | Heat and mass transfer at scale | Paracetamol synthesis [39] |

| Reactive Distillation | 20-80% [40] | N/A (Combined unit operations) | Limited to compatible T & P windows | Esterification, Biodiesel [40] |

| Microreactors | High efficiency from enhanced transfer | N/A (Primarily lab/pilot scale) | Susceptible to clogging | Fine chemicals, Pharmaceuticals [40] |

Table: Environmental Impact Metrics for Green Chemistry Principles

| Metric | Traditional Pharma Process | Intensified Green Process | Measurement Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Process Mass Intensity (PMI) | High (E-factor can be 25-100+ for API) [41] | Significantly Lower | kg of total input per kg of API [37] |

| Solvent Waste | 80-90% of total waste [39] | Minimized or eliminated (e.g., Mechanochemistry) [42] | % of total waste generated |

| Carbon Footprint | High (Chem industry is energy intensive) | Significant reduction (e.g., 5% of EU emissions from chem industry) [42] | Equivalent CO₂ (eCO₂) [37] |

Standard Operating Protocols (SOPs)

Detailed Protocol: Continuous Flow Synthesis of a Model API Intermediate

This protocol outlines the steps for setting up and operating a continuous flow system for chemical synthesis, emphasizing safety and process control.

Principle: To achieve a safe, efficient, and scalable synthesis by leveraging enhanced heat and mass transfer in a continuous flow regime [40].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials for Continuous Flow Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Continuous Flow Synthesis

| Item/Reagent | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|

| Hastelloy or SS Microreactor Chip | Core reaction vessel; resistant to corrosion and high pressure. |

| High-Precision HPLC or Syringe Pumps | Deliver reagents at a constant, precise flow rate. |

| Downstream Back-Pressure Regulator (BPR) | Maintains system pressure, prevents solvent degassing, and controls gas solubility. |

| In-line IR or UV Analyzer | Provides real-time reaction monitoring for process control. |

| Static Mixer Element | Ensures rapid and efficient mixing of reagent streams. |

| Temperature-Controlled Heater/Chiller | Maintains precise reactor temperature for consistent results. |

Procedure: