Renewable Feedstocks in Chemical Manufacturing: A Strategic Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the transition to renewable feedstocks in chemical manufacturing, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Renewable Feedstocks in Chemical Manufacturing: A Strategic Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the transition to renewable feedstocks in chemical manufacturing, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational drivers—from economic and policy pressures to the demand for sustainable therapeutics. The content details cutting-edge methodologies like catalytic deoxygenation and the use of bio-derived polymers for biomedical applications such as implantable devices and biosensors. It also addresses critical challenges in feedstock processing and purity, alongside a comparative evaluation of the performance and economic viability of green chemicals. Finally, the article validates this shift through market data and emerging investment trends, outlining a clear path forward for integrating sustainable chemistry into biomedical innovation.

The Paradigm Shift: Why Renewable Feedstocks Are Reshaping Chemical Manufacturing

The chemical industry is undergoing a transformative shift toward sustainable and circular production models, driven by the urgent need to decarbonize industrial processes and reduce dependence on fossil resources. Renewable feedstocks—derived from biomass, waste streams, and captured carbon dioxide—represent a cornerstone of this transition, offering a path to significantly reduce the carbon footprint of manufactured goods [1] [2]. Unlike first-generation bio-based feedstocks that often compete with food supply chains, next-generation alternatives utilize non-food resources, thereby supporting a circular bioeconomy that transforms waste into valuable chemical intermediates, polymers, and specialty products [2].

This article provides a structured overview of three principal categories of renewable feedstocks: lignocellulosic biomass, carbon dioxide, and municipal waste. For each, we detail the sourcing, quantitative potential, current conversion technologies, and specific experimental protocols for their valorization. The global market for sustainable chemical feedstocks is projected to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 16% from 2025 to 2035, reflecting strong regulatory and commercial momentum [1] [2]. By integrating technical data, applied methodologies, and strategic context, this application note serves as a practical resource for researchers and engineers pioneering sustainable manufacturing routes.

Lignocellulosic Biomass

Lignocellulosic biomass (LCB), the most abundant renewable polymer on Earth, is derived from plant cell walls and is primarily composed of cellulose (35-52%), hemicellulose (20-35%), and lignin (10-25%) [3] [4]. Its sources are predominantly agricultural residues (e.g., straw, stover), forestry residues, and dedicated energy crops. The annual global generation of key agricultural residues exceeds 998 million tons, representing a substantial, underutilized resource for biorefining [4].

Table 1: Global Annual Availability and Composition of Major Agricultural Residues

| Biomass Type | Global Annual Availability (Million Tons) | Cellulose Content (%) | Hemicellulose Content (%) | Lignin Content (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wheat Straw | ~350 | 35-45 | 25-35 | 15-20 |

| Sugarcane Bagasse | 279-300 | 40-45 | 30-35 | 20-25 |

| Rice Husk | ~101.8 | 30-35 | 25-30 | 15-20 |

| Corn Stover | ~170 | 35-45 | 20-30 | 15-20 |

The valorization of LCB focuses on fractionating and converting these three main polymers into value-added products. Cellulose and hemicellulose can be hydrolyzed into fermentable sugars (C5 and C6 sugars) for biological or catalytic upgrading to platform chemicals and biofuels, while lignin is a promising aromatic polymer for chemical production [3] [5]. The following workflow outlines the core conversion pathway.

Key Experimental Protocol: Alkaline Pretreatment and Enzymatic Saccharification

This protocol describes a standard method for deconstructing lignocellulosic biomass to liberate fermentable sugars, a critical first step in many biorefinery processes [3] [4].

Objective: To effectively break down the recalcitrant structure of lignocellulosic biomass (e.g., wheat straw) to recover a high yield of fermentable sugars from cellulose and hemicellulose.

Materials and Reagents:

- Lignocellulosic Biomass: Wheat straw, milled to 1-2 mm particle size.

- Chemical Reagents: Sodium hydroxide (NaOH) pellets, sulfuric acid (H₂SO₄), deionized water.

- Enzyme Cocktail: Commercial cellulase blend (e.g., CTec2, Novozymes) and xylanase.

- Buffers: Sodium citrate buffer (50 mM, pH 4.8).

- Equipment: Autoclave, heated water bath with shaking, benchtop centrifuge, pH meter, fiber filtration setup, HPLC system for sugar analysis.

Procedure:

- Feedstock Preparation:

- Dry the milled wheat straw at 60°C for 24 hours to achieve constant weight.

- Determine the initial compositional analysis (cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin) using standard NREL laboratory analytical procedures (LAPs).

Alkaline Pretreatment:

- Prepare a 2% (w/v) NaOH solution.

- Load biomass at a 10% (w/v) solid loading in the NaOH solution in a pressure-tolerant vessel.

- Incubate at 121°C for 60 minutes in an autoclave.

- After cooling, separate the solid fraction from the black liquor (containing dissolved lignin) by vacuum filtration.

- Wash the solid residue with deionized water until the pH is neutral.

- Recover and dry the pretreated solid for downstream hydrolysis.

Enzymatic Hydrolysis:

- Prepare a reaction mixture in sodium citrate buffer (50 mM, pH 4.8) containing the pretreated biomass at a 5% (w/v) solid loading.

- Add cellulase enzymes at a loading of 20 filter paper units (FPU) per gram of dry substrate. Supplement with xylanase if targeting hemicellulose-derived sugars.

- Incubate the mixture in a shaking water bath at 50°C and 150 rpm for 72 hours.

- Terminate the reaction by heating to 90°C for 10 minutes or by rapid cooling on ice.

Analysis:

- Centrifuge the hydrolysate to separate the solid residue (primarily lignin).

- Analyze the supernatant for glucose, xylose, and inhibitor (e.g., furfural, hydroxymethylfurfural) concentrations using HPLC.

- Calculate the sugar yield and conversion efficiency relative to the theoretical maximum based on initial composition.

Troubleshooting Notes:

- Low Sugar Yields: Optimize pretreatment severity (time, temperature, alkali concentration) or increase enzyme loading.

- Inhibitor Formation: Consider a detoxification step (e.g., overliming, activated charcoal treatment) post-pretreatment if inhibitors are hindering subsequent fermentation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Lignocellulosic Bioprocessing

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Lignocellulosic Biomass Conversion

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Cellulase Enzyme Cocktail | Hydrolyzes cellulose polymers into glucose monomers. | CTec2 / HTec2 (Novozymes) [3] |

| Ionic Liquids | Green solvent for efficient biomass dissolution and pretreatment. | 1-Ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate ([C₂C₁Im][OAc]) |

| CRISPR-based Microbial Strains | Genetically engineered biocatalysts for consolidated bioprocessing (CBP). | Engineed S. cerevisiae or E. coli for co-fermentation of C5 and C6 sugars [3] [5] |

| Solid Acid Catalyst | Catalyzes the dehydration of sugars to platform chemicals like furfural. | Sulfonated carbon catalysts |

Carbon Dioxide (CO₂) Utilization

Carbon dioxide utilization technologies represent a paradigm shift, treating CO₂ not as a waste product but as a C1 building block for chemical synthesis. These processes contribute to closing the carbon cycle and can potentially achieve negative emissions when coupled with carbon capture from point sources or direct air capture (DAC) [1] [2]. The primary pathways for CO₂ conversion can be categorized as thermocatalytic, electrochemical, and biological.

The market for CO₂-derived chemicals is nascent but expanding, with several pioneering technologies reaching commercial scale. For instance, LanzaTech employs biological fermentation to convert industrial off-gases into ethanol [6]. The projected investment required for a full-scale transition to sustainable feedstocks is estimated at US$440 billion to US$1 trillion through 2040, underscoring the significant capital and innovation driving this field [1].

Table 3: Promising Pathways for CO₂ Valorization to Chemicals

| Conversion Pathway | Key Intermediate | Potential Products | Technology Readiness Level (TRL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermocatalytic Hydrogenation | Syngas (CO + H₂) | Methanol, hydrocarbons, synthetic fuels | Pilot to Commercial (TRL 6-9) |

| Electrochemical Reduction | Formic Acid, CO | Formate, ethylene, ethanol | Lab to Pilot (TRL 4-6) |

| Biological Fermentation | Acetate | Ethanol, isopropanol, bioplastics | Commercial (TRL 9) [6] |

| Photocatalytic Reduction | Methane, CO | Solar fuels, chemicals | Basic Research (TRL 2-4) |

Key Experimental Protocol: Electrochemical Reduction of CO₂ to Formate

This protocol outlines a laboratory-scale setup for the electrocatalytic conversion of CO₂ to formate, a valuable chemical feedstock and hydrogen carrier.

Objective: To demonstrate the electrochemical reduction of CO₂ to formate using a metal-based catalyst in an H-cell configuration.

Materials and Reagents:

- Electrolyte: 0.1 M Potassium bicarbonate (KHCO₃) solution.

- Catalyst Electrode: SnO₂ or Pb-coated gas diffusion electrode (GDE).

- Counter Electrode: Platinum wire or foil.

- Reference Electrode: Ag/AgCl (saturated KCl).

- CO₂ Gas: High-purity (99.99%) and associated gas regulation system.

- Equipment: Air-tight H-cell reactor, potentiostat/galvanostat, magnetic stirrer, gas chromatograph (GC) with TCD/FID, ion chromatography (IC) system.

Procedure:

- Cell Assembly:

- Fill the cathodic chamber of the H-cell with 30 mL of 0.1 M KHCO₃ electrolyte. Saturate it with CO₂ by purging for at least 30 minutes prior to the experiment.

- Assemble the cell with the catalyst-coated GDE as the working electrode, separating the anodic and cathodic chambers with an ion-exchange membrane (e.g., Nafion).

- Place the reference electrode close to the working electrode surface in the cathode compartment.

- Ensure the anode chamber is filled with a compatible anolyte.

Electrocatalysis:

- Maintain a constant CO₂ purge in the headspace of the cathode chamber throughout the experiment.

- Apply a constant potential (e.g., -1.6 V to -2.0 V vs. Ag/AgCl) using the potentiostat and record the current.

- Conduct the experiment for a defined duration (e.g., 2 hours) under continuous stirring.

Product Analysis:

- After the experiment, collect a sample of the liquid catholyte.

- Analyze the liquid product for formate concentration using ion chromatography.

- Analyze the gas phase (headspace) for gaseous products (e.g., H₂, CO) using gas chromatography.

- Calculate the Faradaic Efficiency (FE) for formate: FE(%) = (z * F * C * V) / (Q) * 100%, where z is the number of electrons transferred (2 for formate), F is Faraday's constant, C is the formate concentration, V is the electrolyte volume, and Q is the total charge passed.

Troubleshooting Notes:

- Low Faradaic Efficiency: This could indicate catalyst poisoning or competitive hydrogen evolution. Optimize catalyst design/loading and electrolyte pH.

- Poor Catalyst Stability: Check for catalyst leaching or degradation; consider using more robust catalyst supports or different catalyst materials.

Municipal Waste

Municipal solid waste (MSW) represents a pervasive and challenging feedstock, with cities globally generating over 2.4 billion tonnes annually [6]. Modern waste-to-chemicals strategies aim to move beyond simple incineration to advanced conversion technologies that extract higher value, transforming waste into chemical building blocks. This aligns with circular economy principles by addressing waste disposal issues while creating new resources.

Key technological pathways include gasification to syngas, pyrolysis to bio-oil, chemical recycling of plastics, and anaerobic digestion to biogas. Companies like Enerkem and Brightmark are commercializing gasification and advanced pyrolysis processes to convert non-recyclable MSW into methanol, ethanol, and fuels [6]. The economic viability of these processes is continuously improving through technological innovations that enhance yield and selectivity.

Key Experimental Protocol: Catalytic Pyrolysis of Mixed Plastic Waste

This protocol provides a methodology for converting mixed plastic waste into a pyrolysis oil that can be upgraded into valuable chemicals like benzene, toluene, and xylene (BTX).

Objective: To thermally degrade mixed plastic waste in an inert atmosphere in the presence of a catalyst to produce a hydrocarbon-rich pyrolysis oil.

Materials and Reagents:

- Feedstock: Mixed plastic waste (e.g., polyethylene, polypropylene), shredded to < 5 mm.

- Catalyst: Zeolite catalyst (e.g., HZSM-5).

- Equipment: Tubular quartz reactor, fixed-bed furnace, temperature controller, gas supply (N₂ or Ar), condenser system for liquid collection, gas bags for non-condensable gas collection.

Procedure:

- Reactor Setup:

- Load a fixed bed of zeolite catalyst (e.g., 1-2 g) in the middle of the tubular reactor.

- Place the shredded plastic waste (e.g., 5 g) upstream of the catalyst bed in the reactor.

- Assemble the system, ensuring a condenser trap is attached at the reactor outlet and cooled with an ice-water mixture. Connect a gas bag to the condenser outlet.

Pyrolysis Reaction:

- Purge the reactor with an inert gas (N₂) at a flow rate of 50 mL/min for 15 minutes to create an oxygen-free environment.

- Heat the reactor furnace to the target pyrolysis temperature (e.g., 500°C) at a ramp rate of 10°C/min.

- Maintain the final temperature for 60-120 minutes, allowing the plastic to volatilize and the vapors to pass over the catalyst bed.

- Collect the liquid product (pyrolysis oil) in the condenser trap and the non-condensable gases in the gas bag.

Product Analysis:

- Weigh the liquid and solid residue (char) to determine mass balance.

- Analyze the composition of the pyrolysis oil using Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) to quantify the yield of BTX and other hydrocarbons.

- Analyze the non-condensable gas using GC-TCD to determine its composition (e.g., methane, ethane, ethylene).

- Calculate the conversion and product selectivity.

Troubleshooting Notes:

- Coking/Deactivation: Catalyst coking is common. The catalyst can be regenerated by calcining in air at 550°C to burn off the coke.

- Wax Formation: Lowering the pyrolysis temperature or optimizing the catalyst-to-plastic ratio can minimize heavy wax formation.

The transition to renewable feedstocks is a complex but essential undertaking for the future of a sustainable chemical industry. As detailed in these application notes, lignocellulosic biomass, CO₂, and municipal waste each offer distinct advantages and challenges. Key to their commercial success will be the continued development of integrated biorefineries that efficiently fractionate and convert these heterogeneous materials into diverse product streams, maximizing economic and environmental benefits [5].

Future progress hinges on interdisciplinary innovation. Artificial intelligence and machine learning are poised to accelerate catalyst design and optimize process conditions [7] [5]. Similarly, synthetic biology enables the engineering of robust microbial chassis for the biological conversion of complex feedstocks [3] [5]. Furthermore, supportive policy frameworks, such as carbon pricing and extended producer responsibility, are critical to level the playing field with established fossil-based pathways [3]. By leveraging these tools and the foundational methodologies described herein, researchers and industry professionals can continue to advance the frontier of renewable feedstock utilization.

Application Notes

The global chemical industry is undergoing a strategic transformation, driven by the synergistic pressures of regulatory mandates, ambitious corporate sustainability goals, and the imperative for robust supply chain resilience. Renewable feedstocks—derived from biomass, waste streams, and captured carbon—are central to this transition, offering a pathway to decarbonize chemical production and establish a circular economy [8]. The market for next-generation sustainable chemicals is projected to grow from $532.8 million in 2025 to $2.13 billion by 2034, reflecting a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 16.7% [8]. This growth is fundamentally reshaping R&D priorities, requiring researchers to develop novel protocols for feedstock characterization, process integration, and supply chain optimization.

Quantitative Landscape of Key Drivers

The interplay of regulatory, corporate, and supply chain factors creates a complex R&D environment. The following tables summarize critical quantitative data and material solutions essential for experimental planning.

Table 1: Key Regulatory and Market Drivers Impacting R&D

| Driver Category | Specific Policy/Target | Key Quantitative Metric | Impact on Research Priorities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regulatory Pressure | EU ReFuelEU Aviation [9] | SAF blending mandate rising to 70% by 2050 [9] | Accelerates R&D in HEFA, Alcohol-to-Jet (AtJ) pathways [10] |

| EU Renewable Energy Directive (RED III) [9] | 42.5% renewable energy target by 2030 [9] | Focus on low-CI feedstocks (UCO, tallow, lignocellulosic) [9] | |

| U.S. Policy (e.g., Inflation Reduction Act) [10] | Section 45Z Clean Fuel Production Tax Credit [10] | Drives need for robust LCAs and CI verification protocols | |

| Corporate Sustainability | Carbon Neutrality Pledges (e.g., Dow, BASF) [11] [12] | Dow: 5 million metric ton CO₂ reduction by 2030; Carbon neutral by 2050 [11] | Increases demand for R&D in bio-based routes and circular solutions |

| Circular Economy Targets (e.g., Dow) [11] | 3 million metric tons of circular/ renewable solutions commercialized by 2030 [11] | Spurs research in chemical recycling and waste feedstock purification | |

| Supply Chain & Economics | Global Market Growth [8] | $2.13 Billion market for next-gen feedstocks by 2034 (CAGR: 16.7%) [8] | Validates investment in scalable feedstock preprocessing and logistics |

| Feedstock Supply Crunch [9] | Projected tightness for advanced feedstocks (UCO, tallow) by 2028-2030 [9] | Makes R&D into feedstock diversification and yield optimization critical |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Renewable Feedstock Characterization

| Research Reagent / Material | Function/Application | Experimental Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Lignocellulosic Biomass (e.g., wheat straw, corn stover) [13] | Second-generation feedstock for bioethanol and chemical building blocks via biochemical/thermochemical conversion. | Requires preprocessing (drying, chipping) to improve handling and energy density [14]. |

| Microalgae [13] | Third-generation feedstock for biofuels and chemicals; does not compete with food crops. | Cultivation requires careful control of nutrients, light, and CO₂; harvesting and lipid extraction are key cost factors. |

| Used Cooking Oil (UCO) [10] [9] | Waste-derived feedstock for HEFA-based renewable diesel and Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF). | High risk of fraud; requires stringent traceability and chemical analysis (e.g., FFA content) to ensure integrity [10]. |

| Non-Lignocellulosic Bio-based Feedstocks (e.g., corn, soy) [8] | First-generation feedstock for bio-based chemicals and polymers. | Faces sustainability concerns regarding land-use change; often certified under mass balance approaches [12]. |

| Synthetic Biology Tools (engineered microorganisms) [12] [8] | Enables fermentation of sugars into chemical building blocks (e.g., bio-ethylene, specialty chemicals). | Key for producing drop-in replacements; requires optimization for titer, rate, and yield (TRY) to be cost-competitive. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Designing a Resilient Multi-Feedstock Supply Chain Using Integrated Modeling

Purpose

To provide a methodology for the strategic design and planning of a resilient and sustainable bioethanol supply chain that integrates second (e.g., wheat straw, corn stover) and third-generation (e.g., microalgae) feedstocks. This protocol addresses epistemic uncertainties and disruption risks using a combination of Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) and mixed-integer linear programming (MILP) [13].

Materials and Software

- Data: Geospatial data on biomass availability, water resources, solar radiation, land use, and infrastructure.

- Software Tools: Mathematical modeling software (e.g., GAMS, AMPL), machine learning libraries (e.g., TensorFlow, PyTorch), and data envelopment analysis (DEA) tools.

- Computational Resources: High-performance computing (HPC) resources are recommended for large-scale optimization.

Methodology

Phase 1: Optimal Site Selection using DEA and ANN

- Data Collection: Compile a dataset of potential locations for microalgae cultivation facilities. Inputs should include resource availability (water, solar radiation), operational costs, and proximity to transportation networks. Outputs should measure efficiency, such as potential biomass yield per unit cost [13].

- Efficiency Ranking: Employ Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) to rank the potential locations based on their relative efficiency in converting inputs to outputs.

- Site Prediction: Train an Artificial Neural Network (ANN) model using the DEA results. The ANN will learn the complex, non-linear relationships between the location characteristics and their efficiency scores. This model can then predict the efficiency of new, unrated sites for establishing cultivation centers [13].

Phase 2: Multi-Objective Supply Chain Optimization

- Model Formulation: Develop a mixed-integer linear programming (MILP) model with the following objective functions:

- Minimize total supply chain cost (including cultivation, transportation, production, and storage).

- Minimize greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions across the entire chain.

- Maximize positive social impact (e.g., employment) [13].

- Decision Variables: The model should determine:

- Optimal number, location, and capacity of biorefineries.

- Optimal feedstock mix and sourcing plans.

- Production volumes and technology selection (biochemical/thermochemical).

- Distribution network and transportation modes [13].

- Constraint Integration: Incorporate constraints for biomass availability, production capacity, and meeting demand.

Phase 3: Incorporating Resilience to Uncertainty

- Parameter Uncertainty: Address uncertainties in costs, prices, and feedstock yields using a robust stochastic-possibilistic programming approach. This models random parameters with probability distributions and epistemic uncertainties (e.g., lack of data) with possibility distributions [13].

- Disruption Risk Modeling: Introduce random disruption scenarios (e.g., natural disasters, supplier failure) to the model. The robust optimization model will generate a supply chain design that can maintain operations under these disruptive events [13].

- Model Solving and Validation: Solve the robust optimization model and compare the results (cost, performance) against a deterministic model to quantify the value of resilience. Validate the model using real-world case study data [13].

Expected Outcome

A validated and optimized supply chain network design that is both cost-effective and resilient to uncertainties and disruptions. The computational study cited achieved over 11% cost savings compared to a deterministic model [13].

Protocol 2: Ensuring Feedstock Integrity and Traceability for Compliance

Purpose

To establish a chain-of-custody protocol for waste and residue feedstocks, such as Used Cooking Oil (UCO) and tallow, ensuring regulatory compliance (e.g., RED III, LCFS) and mitigating fraud risk, which is critical for securing fuel pathway approvals and tax credits [10].

Materials

- Feedstock samples (UCO, tallow).

- Laboratory equipment for chemical analysis (GC-MS, NIR, titration setup).

- Secure database or blockchain platform for data logging.

- Documentation (bills of lading, certificates of origin, supplier affidavits).

Methodology

Pre-Supplier Engagement and Vetting:

- Conduct on-site audits of feedstock collectors and processors.

- Verify their operational history, storage capabilities, and compliance with relevant standards (e.g., International Sustainability & Carbon Certification).

Chain-of-Custody Documentation:

- Origin Documentation: Obtain sworn affidavits from the point of origin (e.g., restaurant) detailing the oil's type and initial use.

- Transportation Logging: Mandate the use of bills of lading at every transfer point, digitally recorded in a traceability system.

- Mass Balance Tracking: Track the mass of feedstock from collection through conversion to final fuel, reconciling any losses.

Chemical Analysis and Fingerprinting:

- At Receipt: Upon delivery at the conversion facility, take a representative sample of the feedstock.

- Laboratory Testing: Analyze key chemical markers, such as:

- Free Fatty Acid (FFA) Content: High FFA may indicate excessive degradation or adulteration with virgin oils.

- Fatty Acid Profile: Use Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) to establish a unique "fingerprint" for the feedstock batch, which can be cross-referenced against known profiles for UCO, tallow, and virgin oils [10].

- Results Integration: Log all analytical results directly into the traceability platform, linking them to the specific batch.

Regulatory Alignment and Early Engagement:

- Engage with regulators (e.g., EPA for RINs, CARB for LCFS) early in the project development phase to understand pathway approval timing and data requirements.

- Use the compiled documentation and analytical data to support applications for tax credits (e.g., 45Z) and fuel pathway approvals [10].

Expected Outcome

A comprehensive, auditable dossier for each batch of feedstock, providing the integrity assurance needed for compliance with low-carbon fuel standards and de-risking investments in renewable fuel production.

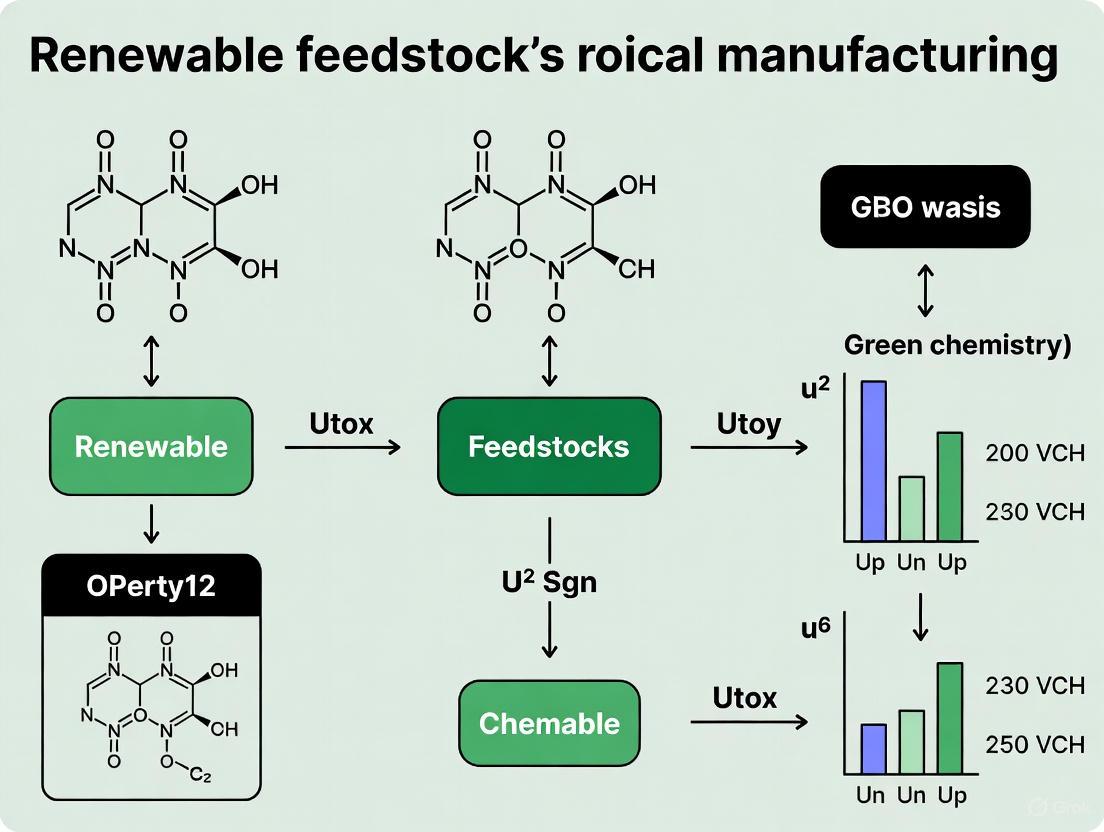

Visualizations

Diagram 1: Interplay of Core Driving Forces

Diagram 2: Multi-Feedstock Supply Chain Optimization Workflow

Application Note: Quantitative Market Landscape (2025-2035)

The chemical industry is undergoing a transformative shift towards sustainable feedstocks, driven by environmental imperatives, regulatory pressures, and corporate sustainability commitments [1]. This application note provides a consolidated quantitative overview of the projected market growth, investment requirements, and key segment analyses for renewable chemicals and feedstocks from 2025 to 2035. The data is critical for researchers and drug development professionals to contextualize their R&D investments and strategic planning within the broader bio-economy.

Consolidated Market Data

Table: Global Renewable Chemicals and Feedstocks Market Projections (2025-2035)

| Metric | Value / Projection | Source / Context |

|---|---|---|

| Market Size (2024) | USD 155.3 Billion [15] | Vantage Market Research |

| Market Size (2025) | USD 125.6 Billion [16] | Fact.MR |

| Projected Market Size (2035) | USD 344.7 Billion [16] to USD 525.8 Billion [15] [17] | Fact.MR / Vantage Market Research |

| CAGR (2025-2035) | 10.6% [16] to 11.75% [15] | Fact.MR / Vantage Market Research |

| Production Capacity CAGR | 16% [1] | For sustainable chemical feedstocks (ResearchAndMarkets.com) |

| Cumulative Investment Required (by 2040) | USD 440 Billion - USD 1 Trillion [1] | For sustainable feedstocks infrastructure |

| Investment Range (by 2050) | USD 1.5 Trillion - USD 3.3 Trillion [1] | High-end scenario for full industrial transformation |

Table: Growth Projections by Key Segment

| Segment | Projected CAGR (2025-2035) | Key Drivers |

|---|---|---|

| Biopolymers | 10.5% [16] | Demand in packaging, agriculture, and healthcare as an alternative to petroleum-based plastics [16]. |

| Algae-based Feedstocks | 9.4% [16] | High yield per acre, non-competition with food crops, and CO₂ sequestration capabilities [16]. |

| Textile Applications | 8.3% [16] | Consumer and regulatory demand for sustainable materials in the fashion industry [16]. |

| Green Chemistry in Pharma | 10% (2024-2033) [18] | Regulatory pressure and demand for safer, eco-friendly drug manufacturing processes [18]. |

Regional Analysis and Key Players

The Asia Pacific region dominated the market in 2024, accounting for over 50% of revenue, and is projected to be the fastest-growing market [15]. North America is also expected to see substantial expansion, driven by federal bioeconomy policies [15]. The competitive landscape includes over 1,000 key players, ranging from established chemical giants like BASF and Braskem to biotechnology innovators such as Ginkgo Bioworks and LanzaTech [1] [15].

Protocol: Experimental Evaluation of Bio-based Feedstocks for Pharmaceutical Applications

Scope

This protocol details a methodology for evaluating the suitability and performance of bio-based feedstocks, specifically bio-solvents and renewable platform chemicals, in pharmaceutical synthesis and bioprocessing workflows.

Principle

Bio-based feedstocks offer a sustainable alternative to fossil-derived chemicals but can exhibit variability in composition and performance. This protocol uses a comparative analysis to assess key parameters—including purity, reaction efficiency, and environmental impact—against traditional reagents, ensuring they meet the stringent requirements of pharmaceutical R&D.

Equipment and Software

- Analytical Balances

- High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) System with UV/VIS detector

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectrometer

- Rotary Evaporator

- Laboratory Reactors / Bioreactors (e.g., 1L benchtop systems)

- Software: Electronic Lab Notebook (ELN) for data management and collaboration [19]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents and Materials for Feedstock Evaluation

| Item | Function / Application | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Bio-based Solvents | Replacement for traditional, often toxic, organic solvents in synthesis and extraction [18]. | e.g., Bio-derived ethanol, 2-methyltetrahydrofuran (2-MeTHF). |

| Biocatalysts | Enzymes used to catalyze specific reactions with high selectivity, reducing waste and energy use [18]. | e.g., Immobilized lipases, Novozymes products [15] [18]. |

| Renewable Platform Chemicals | Building block chemicals derived from biomass for synthesizing complex molecules [1]. | e.g., Bio-succinic acid, furfural, bio-BTX (benzene, toluene, xylene) from waste [1]. |

| Certified Reference Standards | For quantifying purity and identifying impurities in bio-feedstocks via HPLC/GC analysis. | Critical for meeting regulatory requirements for pharmaceutical impurities [20]. |

| Deuterated Solvents | Used for NMR spectroscopy to determine molecular structure and confirm reaction outcomes. | - |

| Microbial Strains | Engineered organisms for fermentative production of target chemicals from renewable feedstocks [19]. | e.g., Engineered E. coli or S. cerevisiae from providers like Ginkgo Bioworks [1]. |

Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the sequential stages of the experimental evaluation protocol.

Procedure

Sourced Feedstock Characterization

- Purity and Composition Analysis: Dilute the bio-based feedstock to an appropriate concentration. Analyze using HPLC or GC-MS against a certified reference standard. Calculate the percentage purity and identify major impurities. For solid biomass feedstocks, perform proximate analysis (moisture, ash, volatile content).

- Structural Confirmation: Dissolve a sample of the feedstock in a suitable deuterated solvent (e.g., DMSO-d6, CDCl3) and acquire 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra. Confirm the molecular structure and identify any structural anomalies compared to its fossil-based equivalent.

- Documentation: Record all data, including chromatograms, spectra, and calculations, in the Electronic Lab Notebook (ELN) [19].

Model Reaction Synthesis

- Experimental Setup: Set up two parallel, small-scale (e.g., 100 mL) reactions to synthesize a relevant pharmaceutical intermediate or active ingredient.

- Test Reaction: Use the bio-based feedstock (e.g., bio-solvent, bio-succinic acid).

- Control Reaction: Use a fossil-derived equivalent of analytical grade.

- Process Monitoring: Maintain identical reaction conditions (temperature, pressure, catalyst loading, reaction time) for both setups. Monitor reaction progress by TLC or in-line analytics at regular intervals.

- Work-up and Isolation: Upon completion, work up both reactions identically (e.g., extraction, washing). Isolate the crude product using a rotary evaporator.

Product and By-product Analysis

- Yield Calculation: Precisely weigh the dried crude products from both the test and control reactions. Calculate and compare the percentage yield.

- Purity and Selectivity: Analyze the crude products using HPLC to determine the purity of the target compound and the profile of any by-products or impurities. Compare the selectivity of the reaction when using the bio-based versus the traditional feedstock.

- Identity Confirmation: Confirm the identity and purity of the isolated target product using NMR spectroscopy.

Sustainability Assessment

- Life Cycle Inventory (LCI): Gather data from the experimental procedures, including:

- Mass of all input materials (feedstocks, catalysts, solvents).

- Energy consumption (heating, stirring, purification).

- Mass and composition of all output streams (product, waste).

- Comparative Analysis: Perform a streamlined Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) comparing the test and control processes. Focus on key environmental impact categories such as carbon footprint and waste generation. This data supports corporate ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) reporting [15].

Data Analysis and Reporting

- Performance Metrics: Compare the reaction yield, purity, and selectivity between the bio-based and control experiments. A performance within 5-10% of the control is typically acceptable for further investigation.

- Sustainability Metrics: Calculate and report the reduction in carbon footprint and waste generation achieved by the bio-based feedstock.

- Go/No-Go Decision: Based on the combined technical performance and sustainability assessment, make a recommendation on whether the bio-based feedstock warrants further scale-up studies. All data, analysis, and the final decision must be comprehensively documented in the ELN system to ensure traceability and support regulatory compliance [19].

Application Notes: The Case for Sustainable Feedstocks in Pharmaceutical Development

The transition to sustainable, bio-based feedstocks represents a paradigm shift for the pharmaceutical industry, aligning the dual objectives of patient health and planetary wellness. This transition is driven by the recognition that a significant portion of a drug's environmental footprint is embedded at the earliest stages of its life cycle, from the sourcing of its raw materials [21]. Unlike first-generation biofuels that compete with food supplies, next-generation feedstocks leverage non-food renewable sources, supporting a circular bioeconomy that transforms waste into valuable chemical intermediates [2] [22].

Market Context and Driver

The chemical industry is at a turning point, with increasing regulatory pressure and corporate sustainability commitments accelerating the adoption of green alternatives. Production capacity for chemicals from next-generation feedstocks is forecast to grow at a robust 16% compound annual growth rate (CAGR) from 2025-2035, reaching over 11 million tonnes by 2035 [2]. The global renewable chemical manufacturing market, valued at USD 95.7 billion in 2023, is predicted to reach USD 196.5 billion by 2031, expanding at a CAGR of 9.5% [23]. This growth is particularly relevant to biomedical and pharmaceutical applications, which are key segments in this expanding market [23].

Table 1: Key Market Drivers for Sustainable Feedstocks in Pharma

| Driver Category | Specific Example | Impact on Drug Development |

|---|---|---|

| Regulatory Pressure | EU REACH, US TSCA [22] | Mandates risk assessments and promotes safer chemicals in a circular economy. |

| Corporate Sustainability | 66% of large European chemical end-users have 2030 GHG reduction targets [24] | Creates demand for low-carbon pharmaceutical ingredients from downstream customers. |

| Economic Investment | Cumulative investment of $440B-$1T required by 2040 [1] | Fuels innovation in bio-based synthesis routes for Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs). |

| Technology Advancement | Breakthroughs in lignin extraction and CO₂ conversion [2] | Enables new, sustainable pathways for chemical intermediates used in drug formulation. |

Strategic Advantages for Biomedical Applications

The integration of principles from green chemistry and energy materials science offers a promising path forward for medical technologies [25]. Utilizing bio-derived polymers, non-toxic solvents, and closed-loop recycling systems allows biomedical devices and pharmaceuticals to evolve in a way that supports both patient health and planetary health [25].

For the pharmaceutical industry, this translates into tangible benefits and successful case studies:

- Waste Reduction and Efficiency: AstraZeneca estimates that sustainable drug discovery using green chemistry will save approximately 500,000 kg of carbon dioxide annually compared to traditional processes [21].

- Process Optimization: BASF redesigned its ibuprofen production process to follow green chemistry principles, achieving a product carbon footprint 30% below the industry average [21].

- Solvent Substitution: Pfizer overhauled the production of pregabalin (Lyrica), replacing solvents with water. This decreased solvent use by over one million gallons annually and reduced process energy use by 83% [21].

Experimental Protocols: Sustainable Feedstock Sourcing and Conversion

This section provides detailed methodologies for implementing sustainable feedstock strategies in a biomedical research and development context.

Protocol 1: Valorization of Lignocellulosic Biomass for Pharmaceutical Intermediates

Objective: To extract and convert lignin and sugars from agricultural waste (e.g., wheat straw, corn stover) into valuable green chemical intermediates for drug synthesis [2] [22].

Materials:

- Feedstock: Dried and milled agricultural waste (e.g., wheat straw, <2 mm particle size).

- Reagents: Deep Eutectic Solvent (DES) (e.g., Choline Chloride-Lactic Acid), ionic liquids [2], cellulase enzyme cocktail, fermentation media (yeast extract, glucose, salts).

- Equipment: High-pressure reactor, ultrasonic processor, centrifuge, HPLC system, fermenter.

Procedure:

- Pre-treatment: Load 100g of dried biomass into a high-pressure reactor with 1L of DES. Heat to 120°C for 2 hours with continuous stirring [2].

- Separation: Quench the reaction mixture with 2L of deionized water. Separate the solid lignin-rich fraction from the sugar-rich hydrolysate via centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 20 minutes.

- Lignin Purification: Subject the solid fraction to ultrasonic cavitation in a water-ethanol solution (50:50 v/v) for 30 minutes to break down lignin into low-molecular-weight aromatics [2].

- Sugar Fermentation: Adjust the pH of the sugar-rich hydrolysate to 5.5. Inoculate with a metabolically engineered yeast strain (e.g., for lactic acid production) and ferment at 30°C for 72 hours under anaerobic conditions [24] [23].

- Analysis: Quantify platform chemicals (e.g., phenols from lignin, lactic acid from fermentation) using HPLC with UV/RI detection.

Protocol 2: CO₂-to-X Conversion for Pharmaceutical Solvents

Objective: To utilize captured CO₂ as a carbon feedstock for the electrochemical synthesis of green solvents (e.g., methanol, ethanol) for use in drug formulation [2] [24].

Materials:

- Feedstock: Captured and concentrated CO₂ stream.

- Reagents: Electrolyte (e.g., 0.5 M Potassium Bicarbonate), catalyst-coated gas diffusion electrode (e.g., Cu-ZnO/Al₂O₃).

- Equipment: H-type electrochemical cell, gas flow controllers, potentiostat, gas chromatograph (GC).

Procedure:

- Cell Assembly: Assemble a two-compartment electrochemical cell separated by a Nafion membrane. The cathode chamber should contain the catalyst-coated gas diffusion electrode.

- Electrolysis: Pressurize the cathode chamber with CO₂ at 3 bar. Circulate the electrolyte at a constant flow rate. Apply a controlled potential of -0.8 V vs. RHE.

- Product Monitoring: Sample the headspace of the cathode chamber every 30 minutes for 24 hours and analyze via GC with a FID/TCD detector to quantify gaseous and liquid products (e.g., methanol, ethanol).

- Solvent Purification: Distill the liquid products from the electrolyte solution at the end of the experiment.

- Quality Control: Test the purified solvent for residual metals and water content to ensure it meets pharmaceutical-grade standards for use in API synthesis.

Visualization of Sustainable Feedstock Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for converting next-generation feedstocks into materials for biomedical applications, highlighting the circular economy principles.

Biomedical Feedstock Value Chain

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Sustainable Pharmaceutical Research

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Sustainable Source & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Ionic Liquids & Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) | Solvent for lignocellulosic biomass pre-treatment; enables efficient separation of lignin, hemicellulose, and cellulose [2]. | Bio-derived or biodegradable variants; non-volatile, recyclable, and replace toxic organic solvents, reducing VOC emissions [2] [21]. |

| Engineed Enzyme Cocktails | Biocatalysts for hydrolyzing biomass into fermentable sugars (e.g., cellulases) or for synthesizing chiral pharmaceutical intermediates [22] [26]. | Produced via fermentation of sustainable feedstocks; offer high specificity and lower energy requirements compared to traditional chemical catalysts [22]. |

| Metabolically Engineered Microbial Strains | Cell factories for converting sugars (C5, C6) or syngas into target molecules like organic acids (lactic, succinic), biofuels, and complex therapeutics [24] [26]. | Engineered yeasts (e.g., S. cerevisiae) or bacteria (e.g., E. coli); utilize non-food biomass, reducing competition with food supply and enabling new synthesis routes [24]. |

| Non-Toxic Metal Catalysts (e.g., Cu-ZnO) | Heterogeneous catalyst for CO₂ hydrogenation to methanol or for reductive amination in API synthesis [24]. | Replaces rare or toxic heavy metal catalysts (e.g., Pd, Pt); enhances the safety profile of the final pharmaceutical product and reduces environmental impact of catalyst disposal [22]. |

| Bio-derived Polymers (e.g., PLA, PHA, Chitosan) | Function as biodegradable matrices for drug delivery systems, tissue engineering scaffolds, and medical device components [26]. | Sourced from corn sugar (PLA), microorganisms (PHA), or crustacean shells (Chitosan); are renewable and degrade into benign products, addressing end-of-life concerns for medical products [26]. |

From Biomass to Biomedicine: Innovative Processes and Applications

The transition from fossil-based to renewable biomass feedstocks represents a paradigm shift in chemical manufacturing, necessitating the development of specialized deoxygenation technologies. Unlike non-polar fossil resources processed in the gas phase at elevated temperatures, biomass-derived compounds are highly functionalized, polar, and often thermally unstable, requiring liquid-phase processing in polar solvents at moderate conditions [27]. The high oxygen content (often 35-45%) of biomass-derived platform molecules and bio-oils results in undesirable properties such as low thermal stability, high viscosity, corrosiveness, poor volatility, and low heating value, posing significant challenges for their direct application as fuels or chemicals [27] [28]. Catalytic deoxygenation and hydrodeoxygenation (HDO) have emerged as crucial catalytic pathways for removing oxygen from these compounds, thereby increasing their energy density, stability, and compatibility with existing fuel and chemical infrastructure [27] [28] [29].

This application note provides detailed methodologies and protocols for the core conversion technologies enabling the defossilisation of chemical manufacturing, with a specific focus on catalytic systems, reaction mechanisms, and separation strategies for biomass-derived feedstocks [30]. The content is structured to equip researchers and scientists with practical experimental frameworks for implementing these transformative technologies in both fundamental and applied research settings.

Catalytic Deoxygenation Fundamentals

Reaction Mechanisms and Pathways

Catalytic deoxygenation of biomass-derived oxygenates proceeds through several distinct mechanistic pathways, with the dominant route being highly dependent on catalyst composition, reaction conditions, and feedstock molecular structure. The table below summarizes the primary deoxygenation mechanisms and their characteristic features:

Table 1: Primary Catalytic Deoxygenation Mechanisms for Biomass-Derived Oxygenates

| Mechanism | Key Reaction | Oxygen Removal Form | Hydrogen Consumption | Preferred Catalysts |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrodeoxygenation (HDO) | R-OH + H₂ → R-H + H₂O | H₂O | High | Sulfided NiMo/CoMo, Pt, Pd, Ru, Ni, Co |

| Decarboxylation (DCO₂) | R-COOH → R-H + CO₂ | CO₂ | None | Pd, Pt, Ni |

| Decarbonylation (DCO) | R-CHO → R-H + CO | CO | Low | Fe, Ni, Pd, Pt |

| Deoxydehydration (DODH) | Vicinal diols → alkenes | H₂O | Moderate | ReOx, MoOx, VOx-based catalysts |

The HDO reaction mechanism for ketones, a common biomass intermediate, typically follows a three-step pathway on bifunctional catalysts: (1) metal-catalyzed hydrogenation of the ketone to an alcohol, (2) acid-catalyzed dehydration of the alcohol to an alkene, and (3) metal-catalyzed hydrogenation of the alkene to the corresponding alkane [29]. For example, the HDO of 6-undecanone (a model compound from ketonization of waste-derived volatile fatty acids) proceeds through these sequential steps to yield undecane, a straight-chain alkane suitable for sustainable aviation fuel applications [29].

Figure 1: HDO Reaction Mechanism for Ketones on Bifunctional Catalysts

Catalyst Systems and Design Principles

The design of effective deoxygenation catalysts requires careful consideration of multiple components, including the active metal phase, support material, and potential promoters. Bifunctional catalysts containing both metal sites (for hydrogenation/dehydrogenation) and acid sites (for dehydration, isomerization, and C-O bond cleavage) have demonstrated superior performance for HDO reactions [29].

Table 2: Catalyst Components and Their Functions in Deoxygenation Reactions

| Component | Function | Representative Materials | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Active Metal | H₂ activation, hydrogenation | Pt, Pd, Ru, Ni, Co, Sn | Ni, Co: cost-effective alternatives to PGMs [29] |

| Support | Provides acidity, dispersion | Zeolite Beta, Al₂O₃, TiO₂, SiO₂ | Zeolite Beta: tunable acidity, 3D micropores (6-7 Å) [29] |

| Promoter | Modifies electronic properties | ReOx, Sn, Nb, Fe, Cu | ReOx: enhances selectivity to desired diols [27] |

The balance between metal and acid sites is crucial for optimizing HDO efficiency. For instance, in the HDO of 6-undecanone, catalysts with insufficient acid sites exhibit limited dehydration capability, while those with excessive acidity may promote excessive isomerization or coking [29]. Zeolite beta supports, with their tunable SiO₂:Al₂O₃ ratios (25:1 to 300:1), enable precise control over acid site density and characteristics, allowing researchers to balance deoxygenation with alkane isomerization—a desirable trait for optimizing biofuel cold flow properties [29].

Hydrodeoxygenation (HDO) Experimental Protocols

Standard HDO Procedure for Ketone Model Compounds

This protocol describes the hydrodeoxygenation of 6-undecanone as a model reaction for producing linear alkanes suitable for sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) applications. The procedure can be adapted for other ketone substrates with appropriate modifications to reaction conditions [29].

Materials and Equipment

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for HDO Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Specification | Function | Handling Precautions |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6-undecanone | ≥97% purity | Model substrate | Store under inert atmosphere |

| Bifunctional catalyst | e.g., Ni/Zeolite Beta | HDO catalysis | Pre-reduce in H₂ flow at 400°C for 2 h |

| n-dodecane | ≥99% purity | Solvent | Standard laboratory handling |

| High-pressure H₂ | 99.999% purity | Hydrogen source | Use appropriate high-pressure equipment |

| Batch reactor | 100 mL, Hastelloy C276 | Reaction vessel | Pressure rating ≥100 bar |

| Gas chromatograph | FID detector, capillary column | Product analysis | Calibrate with authentic standards |

Experimental Procedure

Catalyst Pretreatment: Load approximately 100 mg of catalyst (e.g., 6% Ni/Zeolite Beta with SiO₂:Al₂O₃ ratio of 25:1) into the reactor. Purge the system with N₂ (50 mL/min) for 15 minutes, then switch to H₂ (50 mL/min) and heat to 400°C at 5°C/min. Maintain at 400°C for 2 hours for reduction, then cool to room temperature under H₂ flow [29].

Reaction Mixture Preparation: In an inert atmosphere glove box, prepare a solution of 1.0 mmol 6-undecanone in 20 mL n-dodecane. Transfer this solution to the reactor containing the pre-reduced catalyst.

Reactor Assembly and Pressurization: Assemble the reactor according to manufacturer specifications, ensuring all fittings are properly tightened. Purge the headspace three times with H₂ (10 bar) to remove residual N₂. Pressurize with H₂ to the desired reaction pressure (typically 20-50 bar) at room temperature.

Reaction Execution: Heat the reactor to the target temperature (typically 250-300°C) with continuous stirring (1000 rpm). Maintain reaction conditions for the prescribed duration (typically 2-6 hours). Monitor pressure throughout the reaction.

Reaction Quenching and Sampling: After the reaction time, cool the reactor rapidly to room temperature using an internal cooling coil or ice bath. Slowly vent the hydrogen pressure and carefully open the reactor. Separate the catalyst from the reaction mixture by centrifugation (10,000 rpm for 10 minutes).

Product Analysis:

- Dilute a 100 μL aliquot of the liquid product in 1 mL dichloromethane.

- Analyze by gas chromatography (GC-FID) using a non-polar capillary column (e.g., DB-1, 30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm) with the following temperature program: 40°C (hold 2 min), ramp to 300°C at 10°C/min, hold 5 min.

- Identify products by comparison with authentic standards and quantify using internal standard calibration (e.g., n-tetradecane as internal standard).

Data Analysis and Calculations

Calculate key performance metrics using the following equations:

- Conversion (%) = (moles of reactant initial - moles of reactant final) / (moles of reactant initial) × 100

- Selectivity to Product i (%) = (moles of product i formed) / (total moles of all products) × 100

- Yield of Product i (%) = (moles of product i formed) / (moles of reactant initial) × 100

Typical performance for optimized catalysts: >90% conversion of 6-undecanone with >80% selectivity to undecane using 6% Ni/Zeolite Beta (SiO₂:Al₂O₃ = 25:1) at 275°C and 30 bar H₂ for 4 hours [29].

Hydrogen-Free HDO Approaches

Conventional HDO processes require high-pressure hydrogen, presenting economic and safety challenges. The following protocol outlines alternative approaches that utilize in situ hydrogen generation, eliminating the need for external H₂ supply [31].

Catalytic Self-Transfer Hydrogenolysis Using Endogenous Hydrogen

This approach utilizes inherent hydrogen within biomass macromolecules (e.g., aliphatic hydroxyl and methoxy groups in lignin) as hydrogen donors for deoxygenation reactions [31].

Materials and Procedure:

- Catalyst Preparation: Synthesize Pd-Ni bimetallic nanoparticles supported on MIL-100(Fe) according to literature procedures [31].

- Reaction Setup: Charge 0.5 mmol lignin model compound (e.g., guaiacylglycerol-β-guaiacyl ether) and 50 mg catalyst to a round-bottom flask.

- Solvent Addition: Add 10 mL deionized water as reaction medium.

- Reaction Conditions: Heat to 200°C under N₂ atmosphere with stirring (500 rpm) for 6 hours.

- Product Workup: Cool, extract products with ethyl acetate (3 × 10 mL), dry over anhydrous Na₂SO₄, and analyze by GC-MS.

Key Insight: The CαH-OH groups in lignin derivatives serve as hydrogen sources for selective cleavage of β-O-4 linkages, with reported yields of 62-98% for model compounds [31].

In Situ HDO via Water Splitting with Zero-Valent Metals

This approach utilizes zero-valent metals (Zn, Al, Mg, Fe) to generate H₂ in situ through reaction with sub-critical water, simultaneously providing hydrogen for HDO and creating metallic oxides that may catalyze biomass depolymerization [31].

Materials and Procedure:

- Reactor Charging: Load 1.0 g biomass (e.g., pine wood sawdust) and 0.5 g zero-valent metal (e.g., Zn powder, 100 mesh) into a batch reactor.

- Water Addition: Add 20 mL deionized water.

- Reaction Conditions: Heat to 300°C for 2 hours with continuous stirring.

- Product Recovery: Cool reactor, collect aqueous and organic phases separately, extract with dichloromethane, and analyze bio-oil composition by GC-MS.

Performance Metrics: This approach can achieve bio-oil yields of 30-40 wt% with significantly reduced oxygen content (10-15%) compared to conventional liquefaction [31].

Separation Strategies for Biomass-Derived Platform Molecules

Efficient separation of target products from complex reaction mixtures remains a significant challenge in biomass valorization. The following section outlines key separation protocols for important biomass-derived platform molecules.

Separation of 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF)

HMF is a promising biomass-derived platform molecule with low oxygen content, but its separation from aqueous reaction media presents challenges [27]. The following protocol describes an efficient separation approach:

Materials:

- HMF reaction mixture (from acid-catalyzed dehydration of fructose)

- Ethyl acetate (≥99.5% purity)

- Sodium chloride (ACS reagent grade)

- Anhydrous sodium sulfate

Procedure:

- Liquid-Liquid Extraction:

- Adjust the pH of the HMF-containing reaction mixture to 7.0 using 1M NaOH solution.

- Transfer 100 mL of the neutralized mixture to a separatory funnel.

- Add 50 mL ethyl acetate and shake vigorously for 2 minutes.

- Allow phases to separate completely (10-15 minutes).

- Collect the organic (upper) phase.

- Repeat extraction twice with fresh ethyl acetate (2 × 50 mL).

Salting Out Enhancement:

- For improved extraction efficiency, add NaCl to the aqueous phase to 5% (w/v) before extraction.

- This salting out effect enhances HMF partitioning into the organic phase.

Drying and Concentration:

- Combine all ethyl acetate extracts and dry over anhydrous Na₂SO₄ (5 g per 100 mL extract) for 30 minutes with occasional stirring.

- Filter through Whatman No. 1 filter paper to remove desiccant.

- Concentrate under reduced pressure (100 mbar, 40°C) using a rotary evaporator.

- Recover HMF as a yellowish solid with typical purity >90% after single extraction.

Alternative Approach: For industrial-scale applications, consider continuous liquid-liquid extraction or membrane-based separation technologies [27].

Product Purification and Analysis Workflow

The following workflow diagram illustrates the integrated process from catalytic reaction to purified products, highlighting key separation and analysis steps:

Figure 2: Product Separation and Purification Workflow

Quantitative Performance Metrics and Catalyst Comparison

Catalyst Performance Benchmarking

Systematic evaluation of catalyst performance requires standardized metrics and testing protocols. The table below summarizes typical performance ranges for various catalyst types in HDO reactions:

Table 4: Comparative Performance of HDO Catalysts for Biomass-Derived Oxygenates

| Catalyst Type | Representative Formulation | Reaction Conditions | Conversion (%) | Selectivity to Target Product (%) | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sulfide Catalysts | NiMoS/γ-Al₂O₃ | 300°C, 50 bar H₂ | >95 | 70-85 [28] | High activity, established technology | S leaching, contamination |

| Noble Metal | Pt/Zeolite Beta | 250°C, 30 bar H₂ | >90 | 80-90 [29] | Excellent selectivity, no S requirement | High cost, scarcity |

| Non-precious Metal | 6% Ni/Zeolite Beta | 275°C, 30 bar H₂ | >90 | >80 [29] | Cost-effective, abundant | Moderate stability |

| Metal Phosphides | Ni₂P/SiO₂ | 300°C, 30 bar H₂ | >95 | 75-90 [28] | High HDO activity, S-free | Complex synthesis |

| Bimetallic Systems | Pd-Ni/MIL-100(Fe) | 200°C, water | 62-98 [31] | Varies by substrate | H₂-free operation, water medium | Limited substrate scope |

Green Chemistry Metrics for Process Evaluation

The implementation of green chemistry principles enables quantitative assessment of the sustainability improvements offered by catalytic deoxygenation technologies [32]. The following metrics should be calculated to evaluate process efficiency:

Table 5: Green Chemistry Metrics for Deoxygenation Process Evaluation

| Metric | Calculation Formula | Target Values | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| E-factor | Total waste mass (kg) / Product mass (kg) | <5 for specialties <20 for pharmaceuticals [32] | HDO process waste assessment |

| Atom Economy | (MW product / Σ MW reactants) × 100% | >70% considered good | Reaction pathway selection |

| Process Mass Intensity (PMI) | Total mass input (kg) / Product mass (kg) | <20 for pharmaceuticals | Overall process efficiency |

| Solvent Intensity | Solvent mass (kg) / Product mass (kg) | <10 target | Separation process optimization |

| Carbon Efficiency | (Carbon in product / Carbon in feedstock) × 100% | Maximize (>60%) | Biomass utilization efficiency |

For example, the transition from traditional stoichiometric reagents to catalytic HDO processes can reduce E-factors from >100 to 10-20 in pharmaceutical manufacturing, representing a 5-10 fold improvement in waste reduction [32].

Concluding Remarks and Future Directions

Catalytic deoxygenation and hydrodeoxygenation technologies represent cornerstone processes in the transition toward defossilized chemical manufacturing. The experimental protocols and application notes provided herein offer researchers practical frameworks for implementing these transformative technologies in both fundamental and applied research settings.

Future development in this field will likely focus on several key areas: (1) the design of increasingly selective and stable catalyst systems using earth-abundant elements, (2) the integration of HDO processes with upstream biomass fractionation and downstream separation operations, and (3) the development of hydrogen-free deoxygenation strategies that improve process economics and sustainability [31] [29]. The continued advancement of these core conversion technologies will be essential for establishing a circular carbon economy based on renewable biomass feedstocks.

Application Notes: Platform Molecules and Their Derivatives

The transition to a sustainable chemical industry relies on the development of biorefineries that convert lignocellulosic biomass into platform chemicals, reducing dependence on finite fossil fuel-based resources [33]. These platform chemicals serve as renewable building blocks for producing a spectrum of marketable products, including fuels, materials, and chemicals [34]. Among the most promising platforms are 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF), levulinic acid (LA), and sorbitol, each offering distinct transformation pathways and application opportunities.

Table 1: Key Platform Molecules from Biomass and Their Primary Derivatives

| Platform Molecule | Primary Feedstock | Key Derivatives | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) | Cellulose-derived monosaccharides (e.g., glucose, fructose) [35] | 2,5-Furandicarboxylic acid (FDCA), 2,5-Diformylfuran (DFF) [35] | Biopolymers, pharmaceuticals, functional materials [35] |

| Levulinic Acid (LA) | Lignocellulosic biomass via acid-catalyzed dehydration of cellulose/hemicellulose [36] [37] | γ-Valerolactone (GVL), Ethyl Levulinate, Methyltetrahydrofuran (MTHF) [36] [37] | Biofuels (gasoline/diesel additives), solvents, precursors for succinic acid [36] [37] |

| Sorbitol | Hydrogenation of glucose [34] | Isosorbide, glycols, hydrogen [34] [38] | Polymers, agrochemicals, food additives, hydrogen production via aqueous-phase reforming [34] [38] |

The valorization of these platform molecules is facilitated by advanced catalytic systems. Metal-based catalysts, including transition metals like nickel, cobalt, and noble metals like platinum and ruthenium, are pivotal in driving critical reactions such as hydrogenation, hydrodeoxygenation, and aqueous-phase reforming [39]. The choice between homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysts involves a trade-off; heterogeneous systems offer easy separation and reusability, while homogeneous catalysts can provide superior selectivity for complex transformations [39].

Experimental Protocols

Catalytic Transformation of Glucose to HMF and Derivatives

Principle: This protocol describes the acid-catalyzed dehydration of glucose to HMF, followed by its oxidative conversion to 2,5-diformylfuran (DFF) and subsequent reductive amination to bis(aminomethyl)furan (BAMF), a valuable diamine for polymer synthesis [35].

Materials:

- Feedstock: D-Glucose

- Catalysts:

- For dehydration: Solid acid catalyst (e.g., acidic zeolite) or Lewis acid catalyst.

- For oxidation: Metal oxide catalyst.

- For reductive amination: Co/ZrO₂ catalyst.

- Reagents: Solvent (e.g., Dimethyl sulfoxide, DMSO), primary amine (e.g., n-butylamine), ammonia (NH₃), hydrogen (H₂) gas, oxalic acid.

- Equipment: High-pressure batch reactor, microwave reactor (for alternative pathways), heating mantles, gas supply system, vacuum filtration setup.

Procedure:

- Glucose to HMF:

- Charge the reactor with D-glucose (1.0 g) and DMSO (20 mL).

- Add the solid acid catalyst (0.1 g).

- Purge the system with an inert gas (e.g., N₂) and seal.

- Heat the reactor to 150°C with continuous stirring for 2-4 hours.

- Cool the reactor to room temperature and separate the catalyst by filtration.

- Recover HMF from the solution via extraction or distillation.

HMF to DFF:

- Dissolve the obtained HMF in a suitable solvent.

- Add a metal oxide catalyst and conduct the oxidation under an oxygen atmosphere at elevated temperature (e.g., 120°C) for 4-6 hours.

- Filter to recover the catalyst and isolate DFF.

DFF to BAMF (Reductive Amination):

- Charge a high-pressure reactor with DFF, a solvent, and n-butylamine (to suppress DFF self-polymerization).

- Add the Co/ZrO₂ catalyst (50 mg per 1 mmol DFF).

- Pressurize the reactor with NH₃ (5 bar) and H₂ (20 bar).

- Heat to 120°C with stirring for 6-8 hours.

- After reaction completion, cool the reactor and carefully release the pressure.

- Separate the catalyst by centrifugation and purify BAMF via distillation or recrystallization. A yield of approximately 35% based on the initial glucose can be expected [35].

Alternative Pathway for N-containing Compounds: For the direct synthesis of N-substituted pyrrole-2-carbaldehydes from glucose, react D-glucose with primary amines in DMSO at 90°C in the presence of oxalic acid as a catalyst. This one-pot method avoids the isolation of HMF and provides the target heterocycles in 21-48% yield within a few hours [35].

Production and Valorization of Levulinic Acid (LA)

Principle: This protocol covers the acid-catalyzed hydrolysis of lignocellulosic biomass or monosaccharides to produce LA, and its subsequent hydrogenation to γ-valerolactone (GVL), a versatile green solvent and fuel additive [36] [37].

Materials:

- Feedstock: Lignocellulosic biomass (e.g., sugarcane bagasse, pre-treated) or monosaccharides (e.g., glucose).

- Catalysts: For hydrolysis: Mineral acid (e.g., H₂SO₄) or solid acid catalyst. For hydrogenation: Ruthenium (Ru) based catalyst [39].

- Reagents: Water, hydrogen (H₂) gas.

- Equipment: High-pressure Parr reactor, acid-resistant stirrer, pH meter, liquid-liquid extraction setup.

Procedure:

- LA Production via Hydrolysis:

- Load the reactor with pre-treated lignocellulosic biomass (5.0 g) and a dilute aqueous solution of H₂SO₄ (1-2% w/w, 100 mL).

- Seal the reactor and heat to 200-220°C under autogenous pressure for 20-30 minutes.

- Cool the mixture rapidly and neutralize the acid with a base (e.g., Ca(OH)₂).

- Filter the mixture to remove solid residues (e.g., humins) and purify LA from the aqueous solution via extraction or membrane separation.

- LA Hydrogenation to GVL:

- Dissolve the obtained LA (1.0 g) in water or an organic solvent in a high-pressure reactor.

- Add the Ru-based catalyst (0.05 g).

- Pressurize the reactor with H₂ gas (30-50 bar).

- Heat the reaction mixture to 150-200°C with stirring for 2-4 hours.

- After completion, cool the reactor, vent the hydrogen, and recover the catalyst by filtration.

- The GVL product can be purified by distillation under reduced pressure.

Catalytic Hydrogenation and Reductive Amination of Sugars

Principle: This protocol outlines the catalytic hydrogenation of glucose to sorbitol and the reductive amination of sugar-derived aldehydes and ketones to synthesize nitrogen-containing compounds, such as amino alcohols [35] [38].

Materials:

- Feedstock: D-Glucose or xylose.

- Catalysts: Ruthenium complexes with organophosphine ligands for reductive amination; Nickel or Ruthenium supported catalysts for hydrogenation [35] [39].

- Reagents: Hydrogen (H₂) gas, nitrogen source (e.g., ammonia, primary amines).

- Equipment: High-pressure autoclave, Schlenk line for air-sensitive catalysts, HPLC for yield analysis.

Procedure:

- Glucose to Sorbitol (Hydrogenation):

- Charge the reactor with an aqueous solution of glucose and a supported metal catalyst (e.g., Ru/C).

- Pressurize with H₂ (40-60 bar) and heat to 100-140°C for 2-6 hours.

- After reaction, filter the catalyst and concentrate the solution to obtain sorbitol.

- Synthesis of β-Amino Alcohols (Reductive Amination):

- Charge the reactor with a biomass-derived sugar (e.g., xylose), an amine, and the Ru-complex catalyst.

- Pressurize with H₂ (20-40 bar).

- Heat the mixture to 120-150°C for 5-10 hours under acidic conditions to facilitate selective C-C bond cleavage and C-N bond formation [35].

- Cool, depressurize, and isolate the β-amino alcohol products via chromatography or distillation.

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

Biomass Conversion to Platform Molecules

Levulinic Acid Derivative Pathways

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Catalysts for Biomass Conversion Research

| Reagent/Catalyst | Function | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Transition Metal Catalysts (Ni, Co) | Cost-effective hydrodeoxygenation and hydrogenation [39] | Bio-oil upgrading, syngas production via gasification [39] |

| Noble Metal Catalysts (Ru, Pt, Pd) | High-activity hydrogenation and aqueous-phase reforming [39] | LA to GVL conversion, hydrogen production from sorbitol [39] |

| Solid Acid Catalysts (Zeolites) | Hydrolysis and dehydration with easy separation [39] | Cellulose hydrolysis to glucose, glucose dehydration to HMF [36] |

| Co/ZrO₂ Catalyst | Reductive amination [35] | Conversion of DFF to BAMF (diamine monomer) [35] |

| Ru-Organophosphine Complex | Reductive amination with C-C cleavage [35] | Synthesis of β-amino alcohols from sugars [35] |

| Ionic Liquids | Solvent and catalyst for biomass fractionation [37] | Pretreatment of lignocellulose, conversion of sugars to levulinate esters [37] |

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | Polar aprotic solvent for dehydration reactions [35] | Solvent for glucose-to-HMF conversion and pyrrole synthesis [35] |

Sustainable Synthesis of Natural Products and Pharmaceutical Intermediates

The global chemical industry is undergoing a transformative shift toward sustainable feedstocks, driven by environmental imperatives and the urgent need to decarbonize industrial processes. This transition is particularly critical for the pharmaceutical sector, where synthetic processes have traditionally relied on fossil-based resources, generating substantial waste and carbon emissions [40]. The integration of green chemistry principles and renewable carbon sources represents a fundamental redesign of pharmaceutical manufacturing, moving toward a circular bioeconomy that turns waste into valuable chemical intermediates [41] [2].

The market for next-generation chemical feedstocks is projected to grow at a remarkable 16% compound annual growth rate (CAGR) from 2025 to 2035, signaling rapid industry adoption [40] [42]. This transition demands substantial investment, estimated between $440 billion and $1 trillion through 2040, potentially reaching $3.3 trillion by 2050 [40]. For pharmaceutical researchers and development professionals, this evolution presents both a challenge and unprecedented opportunity to redesign synthetic pathways for natural products and key intermediates using sustainable feedstocks including lignocellulosic biomass, municipal waste, captured carbon dioxide, and engineered biological systems [40] [43] [41].

Renewable Feedstock Platforms for Pharmaceutical Synthesis

Classification and Sourcing of Next-Generation Feedstocks

Sustainable feedstocks for pharmaceutical synthesis can be categorized by origin and processing requirements. Unlike first-generation bio-based chemicals that compete with food supplies, next-generation feedstocks leverage non-food renewable sources, supporting both sustainability and food security [2].

Table 1: Classification of Renewable Feedstocks for Pharmaceutical Applications

| Feedstock Category | Specific Sources | Key Advantages | Pharmaceutical Applications | Technology Readiness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lignocellulosic Biomass | Wood waste, agricultural residues (e.g., straw, bagasse) | Abundant, non-food competitive, carbon neutral | Lignin-derived phenolics, cellulosic sugars for fermentation | Commercial to pilot scale [40] [2] |

| Non-lignocellulosic Biomass | Algae, dedicated energy crops | High growth yield, minimal land use | Specialty lipids, carotenoids, antioxidants | Pilot to demonstration scale [40] |

| Municipal & Plastic Waste | Mixed MSW, end-of-life plastics | Waste valorization, circular economy | Aromatics (BTX) via chemical recycling [2] | Early commercial deployment [2] |

| Carbon Dioxide Utilization | Direct air capture, industrial emissions | Carbon negative potential, abundant | C1 chemicals (methanol, formic acid) [43] | Research to demonstration [43] |

| Waste Polymeric Materials | Mixed plastic waste, biotic polymers | Circular bioeconomy, waste mitigation | Chemical biomanufacturing via engineered microbes [41] | Laboratory to pilot scale [41] |

Economic Considerations and Market Readiness

The economic viability of sustainable feedstocks remains challenging, with production costs often exceeding conventional fossil-based alternatives. Current price premiums are significant: bio-naphtha trades at approximately $800-900/MT premium over fossil naphtha, while bio-ethylene can command 2-3 times the price of its fossil-based equivalent [44]. These cost differentials reflect both nascent production technologies and the externalized environmental costs of conventional feedstocks. However, advancements in processing technologies and potential carbon taxation mechanisms are progressively improving the economic competitiveness of sustainable alternatives [2] [44].

Application Notes: Sustainable Synthesis Protocols

Solar-Driven Production of Chemical Feedstocks (FlowPhotoChem Project)

The EU-funded FlowPhotoChem project demonstrates an integrated approach to producing chemical feedstocks using concentrated solar radiation, water, and carbon dioxide [43]. This innovative process significantly reduces reliance on fossil resources while utilizing greenhouse gases as raw materials.

Table 2: Experimental Protocol for Solar-Driven Ethylene Production

| Process Parameter | Specifications | Notes & Optimization Guidelines |

|---|---|---|

| Feedstock Preparation | CO₂ (captured from air or industrial emissions), deionized H₂O | CO₂ purity >95% recommended; water must be purified to avoid catalyst poisoning |

| Reactor System | Three interconnected modules: (1) Solar H₂O splitting, (2) Solar-driven CO₂ to CO, (3) Electrochemical CO to C₂H₄ | System assembled at DLR's High-Flux Solar Simulator; enables weather-independent operation |

| Solar Concentration | Several hundred times normal sunlight intensity | Achieved using high-flux solar simulator with xenon lamps; optimal for reactor efficiency |

| Process Conditions | Step 1: Photocatalytic H₂O splitting; Step 2: Solar-driven reverse water-gas shift; Step 3: Electrochemical coupling | Thermal integration between modules crucial for overall efficiency |

| Product Output | Ethylene (primary product), optional other target chemicals | Ethylene purity suitable for polymerization; system flexibility allows different chemical targets |

| Scalability Considerations | Best suited for regions in global 'sun belt' | Southern Europe, Australia, US, North Africa, and Middle East ideal [43] |

Experimental Workflow:

- System Assembly: Integrate three specialized reactor modules with comprehensive measurement and control technologies

- Radiation Alignment: Precisely fine-tune alignment and intensity of solar simulation to optimize reactor surface impact

- Process Initiation: Introduce CO₂ and H₂O feeds to first reactor module; maintain steady flow rates

- Intermediate Transfer: Transfer H₂ from first module to second for combination with CO₂

- Product Conversion: Direct CO output from second module to third for electrochemical conversion to ethylene

- Process Monitoring: Continuously monitor output composition, energy efficiency, and system stability

This protocol successfully demonstrates ethylene production, a key precursor for polyethylene and various pharmaceutical intermediates, with potential for significant reduction in carbon footprint compared to conventional steam cracking of naphtha [43].

Green Synthesis of 2-Amino-4H-chromene-3-carbonitrile Derivatives

Chromene derivatives represent an important class of heterocyclic compounds with diverse pharmacological activities, including anticancer, antioxidant, antibacterial, and anti-inflammatory properties [45]. This optimized green synthesis protocol demonstrates the application of sustainable chemistry principles to pharmaceutical intermediate synthesis.

Table 3: Experimental Protocol for Chromene Derivative Synthesis

| Process Parameter | Optimal Conditions | Alternative Conditions Tested |

|---|---|---|

| Catalyst | Pyridine-2-carboxylic acid (P2CA, 15 mol%) | Lower catalyst loading (10 mol%) resulted in incomplete reaction |

| Solvent System | Water:EtOH (1:1 ratio) | Neat ethanol (40 min reaction), water:EtOH (4:1) and (1:4) tested |

| Reaction Conditions | Reflux at 60°C for 10 minutes | Room temperature resulted in incomplete reaction even after 90 minutes |

| Starting Materials | Aldehydes (3 mmol), malononitrile (3 mmol), dimedone (3 mmol) | Various substituted aldehydes successfully tested for substrate scope |

| Workup Procedure | Product precipitates upon cooling; filtration and washing | Simple filtration eliminates need for column chromatography |