Origins and Impact of the 12 Principles of Green Chemistry in Pharmaceutical Research

This article explores the historical foundations, practical applications, and critical evolution of the 12 Principles of Green Chemistry, established by Paul Anastas and John Warner in 1998.

Origins and Impact of the 12 Principles of Green Chemistry in Pharmaceutical Research

Abstract

This article explores the historical foundations, practical applications, and critical evolution of the 12 Principles of Green Chemistry, established by Paul Anastas and John Warner in 1998. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it examines the principles' origins in response to the Pollution Prevention Act of 1990 and their role in shifting industrial chemistry from pollution cleanup to prevention. The content covers the integration of these principles into modern pharmaceutical synthesis, including metrics like Atom Economy and Process Mass Intensity, addresses implementation challenges and critiques, and validates their effectiveness through award-winning case studies and their alignment with broader sustainability goals, providing a comprehensive resource for advancing sustainable practices in biomedical research.

The Genesis of Green Chemistry: From Regulatory Response to a Philosophical Shift

The Pollution Prevention Act (PPA) of 1990 represents a foundational shift in United States environmental policy, establishing a national preference for preventing pollution at its source rather than managing it after creation [1] [2]. This legislative landmark emerged from congressional recognition that the United States "annually produces millions of tons of pollution and spends tens of billions of dollars per year controlling this pollution" despite "significant opportunities for industry to reduce or prevent pollution at the source through cost-effective changes in production, operation, and raw materials use" [3]. The Act's philosophical and practical framework directly catalyzed the conceptualization and development of the Twelve Principles of Green Chemistry, providing the regulatory and policy context that shaped a new approach to chemical design and industrial processes [4].

This whitepaper examines the PPA's foundational elements, its operational mechanisms, and its direct role as a catalyst in the emergence of green chemistry as a defined discipline. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding this regulatory heritage provides crucial context for modern sustainable science practices and their implementation in pharmaceutical development.

Core Provisions of the Pollution Prevention Act of 1990

Legislative Intent and Policy Hierarchy

The PPA established a clear national environmental management hierarchy that prioritizes source reduction above all other waste management strategies [3] [5]. Congress explicitly declared it national policy that:

- Pollution should be prevented or reduced at the source whenever feasible [3] [6]

- Pollution that cannot be prevented should be recycled in an environmentally safe manner whenever feasible [5]

- Pollution that cannot be prevented or recycled should be treated in an environmentally safe manner whenever feasible [5]

- Disposal or other release into the environment should be employed only as a last resort and should be conducted in an environmentally safe manner [3] [6]

This marked a fundamental departure from previous "end-of-pipe" regulatory approaches that focused on managing pollution after it had been created [2].

Key Definitions: Source Reduction and Pollution Prevention

The PPA established precise statutory definitions that created a new vocabulary for environmental protection:

Source Reduction: Defined as "any practice which reduces the amount of any hazardous substance, pollutant, or contaminant entering any waste stream or otherwise released into the environment prior to recycling, treatment, or disposal" [3]. The term specifically includes equipment or technology modifications, process or procedure modifications, reformulation or redesign of products, substitution of raw materials, and improvements in housekeeping, maintenance, training, or inventory control [3] [6].

Pollution Prevention: The EPA defines pollution prevention exclusively as source reduction, explicitly excluding recycling, energy recovery, treatment, and disposal from this definition [5] [6].

Table 1: Pollution Prevention Act Core Definitions and Scope

| Term | Statutory Definition | Included Practices | Excluded Practices |

|---|---|---|---|

| Source Reduction | Any practice that reduces amount of hazardous substances entering waste streams prior to recycling, treatment, or disposal [3] | Equipment/technology modifications; Process/procedure modifications; Product reformulation/redesign; Raw material substitution; Improved housekeeping, maintenance, training, inventory control [3] [6] | Practices that alter characteristics of hazardous substances through processes not integral to production [3] |

| Multimedia | Water, air, and land considered collectively as interconnected environmental media [3] | N/A | Single-medium approaches that shift pollution between different environmental compartments |

Implementation Framework and Mechanisms

EPA Mandates and Administrative Structure

The PPA charged the Environmental Protection Agency with specific implementation responsibilities:

- Establish an independent office within EPA to carry out PPA functions, independent of single-medium program offices but with authority to review and advise on multimedia approaches to source reduction [3]

- Develop and implement a strategy to promote source reduction, including establishing standard measurement methods, coordinating activities across agency offices, and facilitating business adoption of techniques [3]

- Create a Source Reduction Clearinghouse to compile information including a computer database containing information on management, technical, and operational approaches to source reduction [3]

Reporting Requirements: TRI and Source Reduction Reporting

A critical implementation mechanism was the toxic chemical source reduction and recycling reporting requirement mandating that each owner or operator of a facility required to file an annual Toxic Chemical Release Form (Form R) include a detailed toxic chemical source reduction and recycling report covering:

- The quantity of each chemical entering any waste stream prior to recycling, treatment, or disposal

- The amount of each chemical recycled and the recycling process used

- Specific source reduction practices employed, categorized by type

- The amount expected to be reported for the two subsequent calendar years [3]

Table 2: PPA Implementation Mechanisms and Requirements

| Implementation Mechanism | Statutory Authority | Key Requirements | Impact on Regulated Community |

|---|---|---|---|

| Toxic Chemical Source Reduction & Recycling Reporting | §13106 [3] | Annual reporting of source reduction activities; Quantification of chemicals entering waste streams; Description of recycling processes; Projection of future chemical releases [3] [5] | Mandatory for facilities meeting EPCRA §313 thresholds; Creates public record of pollution prevention performance |

| State Matching Grants | §13104 [3] | 50% federal match for state technical assistance programs; Must make specific technical assistance available; Target assistance to businesses where information is an impediment [3] | Creates state-level infrastructure for pollution prevention assistance; Promotes business compliance through education rather than enforcement |

| Source Reduction Clearinghouse | §13105 [3] | Compiles information including computer database; Serves as center for source reduction technology transfer; Mounts active outreach and education programs [3] | Provides centralized access to pollution prevention techniques and technologies; Facilitates knowledge transfer across industries |

The PPA as the Foundation for Green Chemistry Principles

Direct Historical Lineage

The historical record demonstrates that green chemistry emerged specifically in response to the PPA's mandates and policy framework. As documented by the Yale University Center for Green Chemistry and Engineering, "The idea of green chemistry was initially developed as a response to the Pollution Prevention Act of 1990, which declared that U.S. national policy should eliminate pollution by improved design instead of treatment and disposal" [4]. This direct causal relationship is further evidenced by the timeline of key developments:

- 1990: Pollution Prevention Act establishes source reduction as national policy

- 1991: EPA Office of Pollution Prevention and Toxics launches research grant program encouraging redesign of chemical products and processes

- Early 1990s: EPA partners with NSF to fund basic research in green chemistry

- 1998: Paul Anastas and John Warner formally publish the Twelve Principles of Green Chemistry [4]

The PPA's fundamental recognition that "source reduction is fundamentally different and more desirable than waste management and pollution control" provided the philosophical underpinning for the green chemistry principle that it is better to prevent waste than to treat or clean up waste after it is formed [3] [4].

From Regulatory Framework to Scientific Principles

The PPA's conceptual framework directly informed the development of systematic guidelines for chemists. The Act's emphasis on cost-effective changes in production, operation, and raw materials use translated into green chemistry principles addressing atom economy, less hazardous chemical syntheses, and safer solvents and auxiliaries [3] [4].

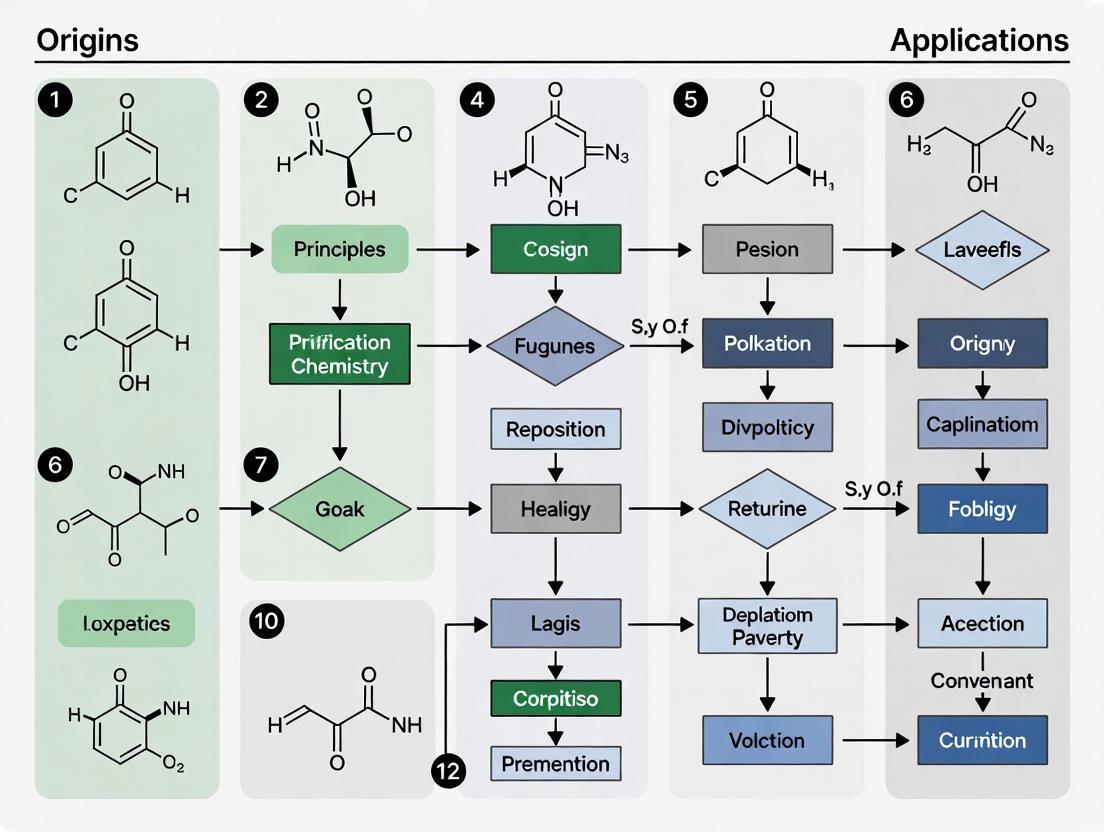

The diagram below illustrates the conceptual transition from the PPA's regulatory framework to the formalized principles of green chemistry:

Research Implementation: Methodologies and Applications

Experimental Framework for Source Reduction Assessment

For drug development professionals implementing PPA-inspired green chemistry approaches, the following methodological framework provides a structured approach to pollution prevention assessment:

Source Reduction Opportunity Identification Protocol

- Material Balance Audit

- Quantify mass inputs and outputs for target synthetic pathways

- Calculate process mass intensity (PMI) using established metrics: PMI = Total mass in process/Mass of product

- Identify major waste streams and their composition

Hazard Assessment

- Characterize toxicity, persistence, and bioaccumulation potential of all reagents

- Apply Green Chemistry Institute's CHEMIST (Chemical Hazard Evaluation for Management and Investment Strategies) criteria

- Prioritize high-concern substances for replacement

Technical Alternatives Analysis

- Evaluate potential feedstock substitutions using Safer Choice criteria [2]

- Assess alternative synthetic pathways using DOZN 2.0 quantitative green chemistry calculator

- Apply Process Mass Intensity (PMI) and E-factor calculations to compare alternatives

Research Reagent Solutions for Green Chemistry Implementation

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies for Pollution Prevention

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Pollution Prevention | Application in Pharmaceutical R&D |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alternative Solvents | Water, Supercritical CO₂, Ionic liquids, 2-Methyltetrahydrofuran (2-MeTHF), Cyrene (dihydrolevoglucosenone) [7] | Replace volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and hazardous air pollutants (HAPs); Reduce fugitive emissions and workplace exposures [4] | Extraction processes; Reaction media; Chromatography mobile phases; Cleaning protocols |

| Catalytic Systems | Heterogeneous catalysts; Biocatalysts (enzymes); Phase-transfer catalysts; Photocatalysts | Enable alternative synthetic pathways with higher atom economy; Reduce stoichiometric reagent requirements; Lower energy consumption [4] [7] | Asymmetric synthesis; Selective functionalization; Tandem reaction sequences; Metabolic pathway engineering |

| Renewable Feedstocks | Carbohydrates, Lignin derivatives, Plant oils, Amino acids, Chitosan | Reduce dependence on petrochemical resources; Utilize biodegradable substrate materials; Implement circular economy principles [7] | Excipient development; Polymer-based drug delivery systems; Starting materials for semisynthetic APIs |

Impact Assessment and Future Directions

Quantitative Impact of PPA Implementation

The PPA's implementation has yielded measurable environmental and economic benefits through its influence on green chemistry adoption:

Table 4: Documented Impacts of PPA and Resulting Green Chemistry Innovations

| Impact Category | Pre-PPA Baseline | Current Performance | Exemplar Technologies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solvent Waste Reduction | Traditional syntheses: PMI >100 [7] | Green syntheses: PMI <10 for pharmaceuticals [7] | Pfizer's sertraline process redesign (reduced from 6 to 3 steps) [4] |

| Energy Efficiency | High-temperature/pressure processes common | Room-temperature biocatalysis; Microwave-assisted reactions; Photochemical synthesis [7] | Merck's sitagliptin biocatalytic route (19% productivity increase) [4] |

| Hazard Reduction | Use of phosgene, cyanides, heavy metals common | Safer alternative reagents; In situ generation of hazardous intermediates; Continuous processing [4] [7] | CO₂-based blowing agents replacing ozone-depleting substances [4] |

Contemporary Challenges and Research Frontiers

Despite significant progress, the PPA framework faces ongoing implementation challenges that guide current research directions:

- Limited Enforcement Mechanisms: The PPA's primarily voluntary approach lacks strong regulatory mandates, depending on economic incentives and corporate responsibility [2]

- Measurement Complexities: Quantifying "avoided pollution" remains methodologically challenging compared to measuring end-of-pipe emissions [2]

- Technology Transfer Barriers: Small and medium-sized enterprises face disproportionate challenges in accessing and implementing advanced pollution prevention technologies [2]

- Emerging Contaminants: The original PPA framework did not anticipate challenges posed by microplastics, pharmaceutical residues, and electronic waste streams [2]

Future research directions focus on predictive toxicology, materials reengineering, and circular economy integration to address these challenges while advancing the PPA's foundational goal of preventing pollution at the molecular level [4] [7].

The Pollution Prevention Act of 1990 served as the crucial regulatory catalyst that transformed environmental management from pollution control to pollution prevention, directly creating the policy environment necessary for the development of the Twelve Principles of Green Chemistry. By establishing source reduction as national policy and creating implementation mechanisms through reporting requirements, technical assistance, and research funding, the PPA provided both the philosophical foundation and practical infrastructure for green chemistry to emerge as a distinct scientific discipline.

For contemporary researchers and drug development professionals, understanding this regulatory heritage provides essential context for the implementation of green chemistry principles in pharmaceutical development. The PPA's enduring legacy is its success in reframing environmental protection as an integral component of chemical design rather than an externality to be managed after the fact—a conceptual shift that continues to drive innovation in sustainable molecular design.

Green chemistry emerged in the 1990s as a transformative, proactive approach to chemical design that reduces or eliminates the use and generation of hazardous substances [4]. This scientific field originated not merely as a technical discipline but as a philosophical framework in direct response to growing environmental concerns and regulatory shifts, notably the U.S. Pollution Prevention Act of 1990 which advocated for pollution prevention at the design stage rather than end-of-pipe cleanup [4] [8]. The movement gained formal structure and a global identity through the pioneering work of Paul Anastas and John C. Warner, who codified the field's core tenets in their seminal 1998 work, Green Chemistry: Theory and Practice [7] [9]. This text provided the first comprehensive treatment of green chemistry's design, development, and evaluation processes, establishing the Twelve Principles of Green Chemistry that have since become the cornerstone of the field [9]. For researchers and drug development professionals, these principles offer a systematic, molecular-level framework for addressing interconnected sustainability challenges in chemical synthesis and product design, emphasizing intrinsic hazard reduction as a fundamental property to be engineered alongside performance characteristics [4].

Historical Context and Key Developments

The development of green chemistry was shaped by evolving environmental policies and a growing recognition of the limitations of conventional pollution control strategies. The following timeline and subsequent analysis capture the pivotal moments that defined the field's early evolution.

Table 1: Key Historical Milestones in the Establishment of Green Chemistry

| Year | Event | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| 1990 | U.S. Pollution Prevention Act | Established national policy favoring pollution prevention over end-of-pipe treatment [4]. |

| 1991 | EPA's "Alternative Synthetic Routes" program | Launched research grants for redesigning chemical processes to reduce environmental impact [4] [7]. |

| 1995 | Presidential Green Chemistry Challenge (PGCC) | Announced program to recognize and promote innovative, industrially applicable green technologies [7]. |

| 1996 | First Presidential Green Chemistry Challenge Awards | Drew significant academic and industrial attention to green chemistry successes [4] [8]. |

| 1997 | Founding of the Green Chemistry Institute (GCI) | Created a non-profit organization dedicated to promoting and advancing the field [7] [8]. |

| 1998 | Publication of Green Chemistry: Theory and Practice | Anastas and Warner formally published the Twelve Principles of Green Chemistry [7] [9]. |

| 1999 | Royal Society of Chemistry launches Green Chemistry journal | Provided a dedicated, high-profile platform for disseminating green chemistry research [4]. |

| 2001 | GCI joins the American Chemical Society (ACS) | Signaled the mainstream acceptance of green chemistry within the central professional society [8]. |

| 2005 | Nobel Prize in Chemistry awarded for Metathesis | Recognized work hailed as "a great step forward for green chemistry," validating the field's importance [4] [8]. |

The historical underpinnings of green chemistry trace back to mid-20th century environmental awareness. Key influences included Rachel Carson's 1962 book Silent Spring, which raised public consciousness about the ecological impacts of pesticides [7] [10], and the 1972 Stockholm Conference, which marked one of the first major international gatherings focused on global environmental issues [7]. The concept of sustainable development, formally defined in the 1987 Brundtland Report, further set the stage by framing environmental protection as compatible with economic and social development [7].

The regulatory and institutional landscape in the United States was particularly instrumental. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) moved away from a "command and control" approach, instead establishing its Green Chemistry Program in the early 1990s [4] [8]. This program, initially named "Alternative Synthetic Routes for Pollution Prevention," was officially renamed "green chemistry" in 1992, formally cementing the term [7]. The founding of the Green Chemistry Institute (GCI) in 1997 as a non-profit, and its subsequent incorporation into the American Chemical Society in 2001, provided critical infrastructure for global collaboration, education, and the integration of green chemistry into industrial practice [7] [8].

The Pioneers: Paul Anastas and John Warner

Paul Anastas

Often referred to as the "Father of Green Chemistry," Paul Anastas was a key architect in establishing the field's conceptual and institutional foundations. While working at the EPA's Office of Pollution Prevention and Toxics, he led the development of the agency's green chemistry program and research grants [4] [8]. His most profound contribution was the articulation and systematization of the field's core ideas into a coherent framework. Anastas also played a pivotal role in mobilizing policymakers and creating recognition mechanisms, most notably chairing the committee that led to the first Presidential Green Chemistry Challenge Awards in 1996 [8]. His work emphasized that green chemistry is not a separate branch of chemistry but a design philosophy that should be integrated across all chemical disciplines, with a focus on reducing intrinsic hazard as a fundamental molecular property [4].

John Warner

John Warner brought complementary expertise in industrial and practical chemistry, helping to bridge the gap between theoretical principles and real-world application. His background contributed to ensuring that the twelve principles were not merely theoretical ideals but actionable guidelines for practicing chemists. Warner's commitment to education was instrumental in embedding green chemistry into the scientific curriculum. He led the creation of the world's first Ph.D. program in Green Chemistry at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, ensuring the training of a new generation of chemists fluent in these principles [8]. Together, Anastas and Warner formed a powerful partnership, with Anastas providing much of the theoretical and policy framework and Warner strengthening the practical, industrial, and educational applications.

Foundational Text:Green Chemistry: Theory and Practice

Published in 1998 by Oxford University Press, Green Chemistry: Theory and Practice by Paul Anastas and John Warner is the seminal text that formally defined the field [9]. The book serves as the first introductory treatment of the "design, development, and evaluation processes central to Green Chemistry," taking a broad, integrative view of the subject [9].

Table 2: Chapter Outline and Core Concepts of "Green Chemistry: Theory and Practice"

| Chapter | Title | Key Focus Areas |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Introduction | Context and necessity for green chemistry. |

| 2 | What is Green Chemistry? | Defining the philosophy and its scope. |

| 3 | Tools of Green Chemistry | Practical methodologies for implementation. |

| 4 | Principles of Green Chemistry | Detailed exposition of the Twelve Principles. |

| 5 | Evaluating the Impacts of Chemistry | Frameworks for holistic impact assessment. |

| 6 | Evaluating Feedstocks and Starting Materials | Analysis of raw material selection and renewable feedstocks. |

| 7 | Evaluating Reaction Types | Efficiency and hazard reduction in reaction design. |

| 8 | Evaluation of Methods to Design Safer Chemicals | Strategies for molecular design to minimize toxicity. |

| 9 | Illustrative Examples | Case studies demonstrating successful application. |

| 10 | Future Trends in Green Chemistry | Forward-looking research directions and opportunities. |

The book's structure moves logically from philosophical foundations to practical tools and evaluative frameworks, culminating in real-world examples and future prospects. Its comprehensive nature integrates diverse topics including alternative feedstocks, environmentally benign syntheses, the design of safer chemical products, new reaction conditions, alternative solvents, catalyst development, and the use of biosynthesis and biomimetic principles [9]. A central thesis is the introduction of new evaluation processes that encompass the complete health and environmental impact of a synthesis, from the choice of starting materials to the final product's end-of-life [9]. By providing specific examples that contrast new methods with classical ones, the text offers researchers and drug development professionals a practical guide for re-imagining chemical processes and products through a green chemistry lens.

The Twelve Principles of Green Chemistry form a cohesive design framework for reducing the environmental and health impacts of chemical processes and products. For researchers in drug development, these principles provide a checklist for optimizing syntheses toward greater efficiency and safety.

Table 3: The Twelve Principles of Green Chemistry: Definitions and Research Applications

| Principle | Core Concept | Implementation in Pharmaceutical R&D |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Prevention | Prevent waste rather than treat or clean up [10] [11]. | Design syntheses to minimize by-products, reducing waste disposal burden. |

| 2. Atom Economy | Maximize incorporation of all starting materials into the final product [10]. | Choose synthetic pathways where most reactant atoms are incorporated into the drug molecule. |

| 3. Less Hazardous Synthesis | Use and generate substances with little or no toxicity [10] [11]. | Select reagents and intermediates with improved safety profiles (e.g., less flammable, corrosive). |

| 4. Designing Safer Chemicals | Design products for efficacy while minimizing toxicity [10] [11]. | Apply molecular modeling to optimize therapeutic activity while reducing off-target biological effects. |

| 5. Safer Solvents & Auxiliaries | Minimize use of auxiliary substances (e.g., solvents) [10]. | Switch to greener solvents (e.g., water, ethanol) instead of chlorinated or toxic solvents. |

| 6. Energy Efficiency | Reduce energy requirements by optimizing reaction conditions [10]. | Conduct reactions at ambient temperature and pressure where possible. |

| 7. Renewable Feedstocks | Use raw materials from renewable sources [10]. | Derive chiral intermediates from biomass (e.g., sugars, amino acids) instead of petrochemicals. |

| 8. Reduce Derivatives | Minimize unnecessary derivatization (e.g., protecting groups) [10]. | Develop selective catalysts or enzymatic methods to avoid blocking group chemistry. |

| 9. Catalysis | Prefer catalytic over stoichiometric reagents [10]. | Use enantioselective catalysts to synthesize single-isomer active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs). |

| 10. Design for Degradation | Design products to break down into innocuous substances after use [10]. | Avoid persistent, bioaccumulative molecules; design easily metabolized APIs. |

| 11. Real-Time Analysis | Develop in-process monitoring to control hazardous substances [10]. | Implement Process Analytical Technology (PAT) to detect and control genotoxic impurities. |

| 12. Safer Accident Prevention | Choose substances and forms to minimize accident potential [10]. | Use less volatile, reactive, or explosive chemicals to prevent fires, explosions, and spills. |

The principles are interdependent and function as a unified system [4]. For example, employing catalysis (Principle 9) often improves atom economy (Principle 2) and reduces energy requirements (Principle 6), while also minimizing waste (Principle 1) [10]. The foundational logic of the principles rests on the concept of prevention over remediation, asserting that it is inherently more effective and economically sound to avoid creating hazards than to manage them after the fact [4]. For the pharmaceutical industry, this approach reduces not only environmental footprint but also costs associated with waste handling, exposure controls, and regulatory compliance, thereby freeing resources for innovation [4].

Visualizing the Hazard-Risk Relationship in Green Chemistry

The following diagram illustrates the core strategic shift advocated by Anastas and Warner: targeting the hazard itself at the molecular design stage to eliminate risk at its source.

Diagram 1: Green Chemistry's Prevention Paradigm. This diagram contrasts the traditional reliance on engineering controls to manage risk from hazardous substances with the Green Chemistry approach of designing inherently safer molecules to eliminate the hazard at its source.

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies in Green Chemistry

The implementation of green chemistry principles requires specific methodological shifts in research and development. Below are detailed protocols for key techniques that embody the Anastas-Warner framework.

Protocol 1: Atom Economy Calculation and Reaction Evaluation

Principle Addressed: Principle 2 (Atom Economy) [10].

Objective: To quantitatively evaluate and compare the efficiency of different synthetic routes to a target molecule, prioritizing those that incorporate a higher percentage of starting material atoms into the final product.

Procedure:

- Define Balanced Equation: Write the balanced chemical equation for the proposed synthetic reaction.

- Identify Molecular Weights: Determine the molecular weights (g/mol) of all reactants and the desired product.

- Calculate Total Mass of Reactants: Sum the molecular weights of all reactants.

- Calculate Mass of Desired Product: Note the molecular weight of the desired product.

- Apply Atom Economy Formula: Atom Economy (%) = (Molecular Weight of Desired Product / Sum of Molecular Weights of All Reactants) × 100%

Application in Pharmaceutical Chemistry: This calculation is crucial for route scouting in Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) development. For instance, a rearrangement reaction like the Claisen rearrangement typically has a high atom economy (approaching 100%), as all atoms are conserved. In contrast, a substitution reaction using stoichiometric reagents will have a lower atom economy due to the generation of by-products. This metric, used alongside traditional yield, provides a more complete picture of synthetic efficiency and environmental impact [10].

Protocol 2: Solvent Replacement Guide for Safer Synthesis

Principle Addressed: Principle 5 (Safer Solvents and Auxiliaries) [10].

Objective: To systematically identify and substitute hazardous solvents with safer, more environmentally benign alternatives without compromising reaction efficiency.

Procedure:

- Inventory Current Solvents: List all solvents used in a process (for reaction, separation, and purification).

- Hazard Assessment: Consult solvent selection guides (e.g., ACS GCI Pharmaceutical Roundtable Solvent Selection Guide) to classify solvents based on:

- Health, safety, and environmental criteria.

- Lifecycle impact (manufacturing, disposal).

- Identify Alternatives: For any solvent classified as "hazardous" or "unsuitable," identify potential substitutes from the "preferred" or "usable" categories. Common substitutions include:

- Replacing dichloromethane with ethyl acetate or 2-methyltetrahydrofuran for extraction.

- Replacing hexanes with heptane or cyclopentyl methyl ether.

- Replacing dimethylformamide (DMF) with acetonitrile or N-butylpyrrolidinone.

- Experimental Validation:

- Perform the reaction with the alternative solvent on a small scale.

- Monitor reaction progress (e.g., TLC, HPLC) to ensure comparable or improved conversion and selectivity.

- Optimize reaction parameters (temperature, concentration) as needed for the new solvent system.

- Solvent Recovery Plan: Design a process for solvent recovery and recycling within the workflow to further reduce waste and environmental impact.

Application in Pharmaceutical Chemistry: This protocol directly reduces workplace hazards, waste management costs, and the environmental footprint of pharmaceutical manufacturing processes. It encourages the use of solvents that are less toxic, less persistent, and from renewable sources where possible [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Implementing green chemistry in research and drug development relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials designed to enhance efficiency and reduce hazard.

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Materials for Green Chemistry Research

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Role in Advancing Green Principles |

|---|---|---|

| Solid-Supported Reagents | Reagents immobilized on an insoluble polymer matrix. | Facilitate purification by filtration, reduce exposure to hazardous reagents, and can often be recycled (Principles 1, 3, 5) [10]. |

| Metathesis Catalysts (e.g., Grubbs Catalyst) | Complexes of ruthenium, molybdenum, or tungsten that catalyze olefin metathesis. | Enable direct, atom-economical construction of complex carbon-carbon double bonds, crucial for pharmaceutical and natural product synthesis (Principles 2, 9) [4] [8]. |

| Biocatalysts (Enzymes) | Proteins that act as highly selective biological catalysts. | Perform specific transformations (e.g., kinetic resolutions, chiral synthesis) under mild conditions, often avoiding protecting groups and hazardous reagents (Principles 3, 6, 8) [10]. |

| Alternative Solvents (e.g., 2-MeTHF, Cyrene) | Safer, often bio-derived solvents. | Replace hazardous conventional solvents (e.g., THF, DMF, chlorinated solvents) with alternatives that have better environmental, health, and safety profiles (Principles 3, 5, 7) [10]. |

| Flow Reactors | Continuous flow microreactor systems. | Improve heat and mass transfer, enhance safety with hazardous intermediates, reduce solvent volume, and enable precise reaction control (Principles 1, 6, 11, 12) [10]. |

| Process Analytical Technology (PAT) | In-line or on-line analytical probes (e.g., IR, Raman). | Enable real-time monitoring of reactions to optimize yields, control impurities, and prevent the formation of hazardous substances (Principle 11) [10]. |

The work of Paul Anastas and John Warner, crystallized in Green Chemistry: Theory and Practice, provided a revolutionary framework that redefined the chemist's role in environmental stewardship. By shifting the focus from pollution cleanup to pollution prevention at the molecular level, they established a proactive, design-based philosophy that is both scientifically robust and ethically imperative [4] [9]. The Twelve Principles offer a comprehensive, systematic toolkit for researchers and drug development professionals to innovate safer, more efficient chemical processes and products.

The future of green chemistry lies in treating these principles not as isolated parameters but as a cohesive, mutually reinforcing system [4]. The field is increasingly intersecting with engineering, physics, and biology, while advancements in predictive toxicology and molecular design are making it possible to treat hazard as a malleable molecular property [4]. For the pharmaceutical industry and the broader chemical enterprise, the continued adoption of this framework is essential for addressing interconnected global sustainability challenges—energy, water, climate, and health—at their common root: the molecular level [4]. The legacy of Anastas and Warner is a sustainable chemical industry where economic, social, and environmental performance are harmonized through intelligent design.

The genesis of green chemistry in the early 1990s marked a fundamental transformation in the relationship between chemical science and environmental protection, shifting the paradigm from reactive control to proactive prevention. This philosophical and technical revolution emerged as a direct response to the limitations of traditional "end-of-pipe" or "command and control" environmental strategies, which focused on treating waste and managing pollutants after they were generated [4]. The Pollution Prevention Act of 1990 in the United States formally established this new thinking as national policy, declaring that pollution "should be prevented or reduced at the source whenever feasible" [12]. This legislative foundation catalyzed the scientific community to redefine pollution not as an inevitable byproduct to be managed, but as a design flaw to be eliminated through innovation [7].

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), traditionally a regulatory body, became an unexpected pioneer in this movement by launching research initiatives that prioritized redesign over regulation [4]. By 1991, the EPA's Office of Pollution Prevention and Toxics had initiated a grant program encouraging the redesign of chemical products and processes to reduce their environmental and health impacts [4]. This institutional support provided the crucial impetus for what would crystallize into the formal field of green chemistry—a discipline that designs chemical products and processes to reduce or eliminate the use and generation of hazardous substances across their entire life cycle [12]. The core tenet of prevention represents not merely a technical adjustment but a fundamental reimagining of chemical synthesis and design, positioning molecular innovation as the most effective form of environmental protection.

Historical Foundations: From Reaction to Prevention

The intellectual architecture of pollution prevention as a chemical discipline emerged from a growing recognition that traditional environmental management approaches were inherently limited. End-of-pipe remediation strategies, while sometimes effective for containing existing pollution, represented an economically and environmentally costly approach that failed to address the root causes of waste generation [4] [7]. As one analysis noted, "the cost of handling, treating, and disposing hazardous chemicals is so high that it necessarily stifles innovation: funds must be diverted from research and development (scientific solutions) to hazard management (regulatory and political solutions, often)" [4]. This economic reality, coupled with increasing regulatory pressure and public concern over chemical accidents and pollution, created the necessary conditions for a paradigm shift.

The Pollution Prevention Act of 1990 provided the critical policy framework that codified this shift, establishing a hierarchy that favored source reduction over recycling, treatment, and disposal [12]. The Act defined source reduction as "any practice which reduces the amount of any hazardous substance, pollutant, or contaminant entering any waste stream or otherwise released into the environment prior to recycling, treatment, or disposal" [12]. This legislative foundation prompted the EPA to launch the "Alternative Synthetic Pathways for Pollution Prevention" research program in 1991, which later expanded and was formally renamed "green chemistry" in 1996 [13]. The program represented a radical departure by emphasizing the reduction or elimination of hazardous substance production rather than managing these chemicals after their manufacture and release [13].

The following timeline illustrates key historical milestones in the transition from end-of-pipe solutions to pollution prevention in chemistry:

Figure 1. Historical transition from environmental awareness to the establishment of green chemistry and its prevention paradigm. The green nodes highlight key milestones that established pollution prevention as a core tenet in chemical practice.

The conceptual breakthrough came with the recognition that prevention is fundamentally more efficient than remediation both economically and environmentally [4]. While remediation activities involve separating hazardous chemicals from other materials and treating them for safe disposal, green chemistry prevents the hazardous materials from being generated initially [12]. This prevention-based approach found its comprehensive expression in 1998 when Paul Anastas and John Warner published their groundbreaking work Green Chemistry: Theory and Practice, which systematically outlined the 12 Principles of Green Chemistry [4] [7]. These principles provided the field with a clear set of design guidelines that encompassed not only environmental considerations but also economic and social dimensions, establishing a "triple bottom line" for sustainable chemical practice [4].

The 12 Principles: A Framework for Prevention

The 12 Principles of Green Chemistry, formally introduced by Paul Anastas and John Warner in 1998, represent the operational framework through which pollution prevention is implemented in chemical research, development, and manufacturing [14] [7]. These principles provide a systematic design strategy that embeds environmental considerations at the molecular level, transforming hazard reduction from an external constraint into an intrinsic design objective. The first and arguably most foundational principle—"It is better to prevent waste than to treat or clean up waste after it has been created"—serves as the conceptual anchor for the entire framework, establishing prevention as the paramount priority [14].

The principles are not isolated guidelines but function as an integrated system with mutually reinforcing components that collectively advance the prevention agenda [4]. For example, the principle of atom economy (Principle 2), developed by Barry Trost, challenges chemists to maximize the incorporation of all starting materials into the final product, thereby minimizing waste generation at the molecular level [14] [13]. This represents a significant evolution from traditional yield-based efficiency measurements, which often overlooked the substantial waste generated from by-products and auxiliary materials [14]. Similarly, the emphasis on catalysis (Principle 9) over stoichiometric reagents and the design of safer chemicals (Principles 3, 4) reinforce the prevention paradigm by addressing the root causes of pollution and hazard in chemical processes [12] [14].

Quantitative Metrics for Pollution Prevention

The implementation of these principles requires robust metrics to evaluate and compare the environmental performance of chemical processes. The following table summarizes key green chemistry metrics that enable researchers to quantify waste prevention and process efficiency:

Table 1: Key Quantitative Metrics for Evaluating Green Chemistry Processes

| Metric | Calculation | Application | Ideal Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| E-Factor [15] | Total waste (kg) / Product (kg) | Measures environmental impact via waste generation | Lower is better (0 = no waste) |

| Atom Economy [14] | (MW of desired product / Σ MW of all reactants) × 100 | Theoretical efficiency of incorporating atoms into product | Higher is better (100% = all atoms utilized) |

| Process Mass Intensity (PMI) [14] | Total mass in process (kg) / Mass of product (kg) | Comprehensive measure of all materials used, including solvents, water | Lower is better (1 = perfect efficiency) |

These metrics have revealed striking inefficiencies in traditional chemical manufacturing, particularly in the pharmaceutical industry where E-factors historically exceeded 100 kg waste per kg product in many cases [14]. Through the application of green chemistry principles, dramatic reductions in waste generation have been achieved, sometimes by as much as ten-fold, demonstrating the powerful practical implications of the prevention framework [14].

Methodological Implementation: From Theory to Practice

Experimental Design for Waste Prevention

Translating the theoretical framework of green chemistry into practical laboratory and industrial applications requires methodical approaches that prioritize source reduction. The following experimental protocol outlines a systematic methodology for incorporating pollution prevention into chemical research and development:

Atom Economy Analysis: Before beginning synthetic design, calculate the theoretical atom economy for proposed routes using: % Atom Economy = (FW of atoms utilized/FW of all reactants) × 100 [14]. Select pathways that maximize incorporation of starting materials into the final product.

Hazard Assessment of Reagents: Evaluate all proposed reagents, solvents, and potential by-products for human health and environmental toxicity. Prioritize substances with known low toxicity profiles and replace hazardous materials with safer alternatives [12] [14].

Catalyst Selection and Optimization: Identify catalytic alternatives to stoichiometric reagents. Develop reaction conditions that use catalysts in small quantities that can carry out multiple reaction cycles, minimizing waste generation [12] [14].

Solvent System Evaluation: Assess solvent requirements and implement solvent reduction or elimination strategies. Where solvents are necessary, prioritize water-based systems or greener alternatives that reduce environmental impact [12] [14].

Energy Efficiency Optimization: Design reactions to proceed at ambient temperature and pressure whenever possible. Minimize energy-intensive purification steps through improved selectivity [12].

Real-Time Analysis Implementation: Incorporate in-process monitoring and control to minimize by-product formation and enable immediate correction of suboptimal reaction conditions [12].

End-of-Life Considerations: Design target molecules to degrade into innocuous substances after use, preventing environmental persistence [12].

Research Reagent Solutions for Green Chemistry

The practical implementation of green chemistry principles relies on specialized reagents and materials that minimize environmental impact while maintaining functionality. The following table outlines key research reagent solutions that support pollution prevention in chemical synthesis:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Green Chemistry Applications

| Reagent Type | Specific Examples | Function in Green Chemistry | Traditional Hazard Replacement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Catalysts [16] | Lipases, Proteases, Esterases, Oxidoreductases | Biocatalysis with high selectivity under mild conditions | Replace heavy metal catalysts and toxic reagents |

| Green Solvents [12] [14] | Water, Supercritical CO₂, Ionic Liquids, Bio-based Solvents | Reduce volatility, toxicity, and environmental persistence | Replace chlorinated solvents and VOCs |

| Renewable Feedstocks [12] [14] | Plant Oils, Carbohydrates, Lignocellulosic Biomass | Utilize sustainable carbon sources instead of depleting resources | Replace petroleum-derived starting materials |

| Heterogeneous Catalysts [14] | Zeolites, Supported Metal Catalysts, Functionalized Silicas | Reusable, separable catalysts with minimal metal leaching | Replace homogeneous catalysts that generate metal waste |

These reagent solutions enable the practical application of green chemistry principles by providing safer, more efficient alternatives to traditional chemical materials. For example, enzymes as biological catalysts have evolved over millions of years to facilitate chemical reactions with extraordinary precision and efficiency under mild conditions, dramatically reducing energy requirements compared to traditional chemical methods [16].

Case Study: Green Chemistry in Antiparasitic Drug Development

The application of green chemistry principles in pharmaceutical development provides compelling evidence of their effectiveness in achieving meaningful pollution prevention while maintaining therapeutic efficacy. A notable case study involves the development of tafenoquine succinate, recently approved as the first new single-dose treatment for Plasmodium vivax malaria in decades [15]. Traditional synthetic routes for tafenoquine production involved multiple steps with toxic reagents and significant waste generation, representing typical inefficiencies in pharmaceutical manufacturing.

The green chemistry approach developed by Lipshutz's team implemented several key prevention principles through a redesigned synthetic route [15]. The new process featured a two-step one-pot synthesis that dramatically reduced solvent use and eliminated toxic reagents while maintaining high yield and purity [15]. This methodology directly addressed multiple green chemistry principles simultaneously: waste prevention (Principle 1), atom economy (Principle 2), safer solvents (Principle 5), and energy efficiency (Principle 6). The resulting process demonstrated that environmental and economic benefits can be achieved concurrently through thoughtful molecular design.

Another exemplary application comes from the development of an enzymatic synthesis route for Edoxaban, a critical oral anticoagulant [16]. The implementation of enzyme-based green chemistry principles yielded dramatic improvements in process sustainability:

- Organic solvent usage reduced by 90% through water-based enzymatic processes

- Raw material costs decreased by 50% through improved atom economy

- Process complexity significantly reduced with filtration steps cut from 7 to 3

- Environmental impact minimized through reduced hazardous waste generation [16]

These case studies illustrate how the systematic application of green chemistry principles moves beyond incremental improvements to achieve transformative pollution prevention. The following diagram visualizes the strategic approach to implementing green chemistry in pharmaceutical development:

Figure 2. Strategic implementation of green chemistry principles in pharmaceutical development leading to measurable pollution prevention outcomes. The application of specific principles addresses traditional process inefficiencies, resulting in significant environmental and economic benefits.

The success of these applications demonstrates that green chemistry principles provide a verifiable methodology for designing chemical processes that are inherently less polluting and more sustainable. By addressing environmental concerns at the molecular design stage, these approaches achieve pollution prevention that is fundamentally more effective than any end-of-pipe solution could provide.

Future Directions: Expanding the Prevention Paradigm

The future evolution of green chemistry points toward increasingly sophisticated approaches to pollution prevention that integrate emerging scientific capabilities with broader sustainability frameworks. Current research focuses on developing a comprehensive set of design principles that establish hazard reduction as a molecular property as malleable to chemists as traditional characteristics like solubility or melting point [4]. This represents the ultimate expression of the prevention paradigm—designing potential hazards out of chemical products and processes at the most fundamental level.

Innovative approaches are emerging at the intersection of green chemistry and other disciplines. Green Toxicology represents one such frontier, seeking to establish design rules that enable chemists to make informed choices about molecular structures to minimize toxicity while maintaining function [14]. Advances in predictive toxicology and toxicogenomics are making it increasingly possible to understand and avoid structural features associated with hazardous biological interactions, bringing Principle 4 ("Design Safer Chemicals") to its full potential [4] [14]. Similarly, the integration of enzyme catalysis continues to expand, with engineered biocatalysts offering unprecedented selectivity and efficiency under mild, environmentally benign conditions [16].

The framework of Responsible Research and Innovation (RRI) is also being explored as a complement to the 12 principles, addressing socio-ethical, economic, and political dimensions that extend beyond the technical scope of traditional green chemistry [17]. This integration acknowledges that the transition to sustainable chemical practice requires not only scientific innovation but also social engagement, policy support, and economic restructuring. The concept of "One Health"—an integrated approach that recognizes the interconnected health of humans, animals, and ecosystems—is similarly being incorporated into green chemistry, particularly in pharmaceutical development for vector-borne diseases [15]. This holistic perspective reinforces the fundamental premise that pollution prevention at the molecular level creates benefits that extend throughout interconnected biological systems.

As these developments illustrate, the future of green chemistry lies in understanding the 12 principles not as isolated parameters to be optimized separately, but as "a cohesive system with mutually reinforcing components" [4]. This systems approach will be particularly critical for addressing interconnected sustainability challenges related to energy, water, and food, all of which intersect at the molecular level [4]. While significant progress has been made since the field's formal establishment in the 1990s, the full potential of pollution prevention as a core chemical tenet remains to be realized, offering a compelling research agenda for current and future generations of chemists committed to sustainability.

The establishment of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Green Chemistry Program represented a fundamental paradigm shift in environmental protection strategy, moving from pollution control and cleanup to proactive pollution prevention. This transition was formally catalyzed by the Pollution Prevention Act of 1990, which declared that U.S. national policy should eliminate pollution by improved design, including cost-effective changes in products, processes, and use of raw materials, rather than relying solely on treatment and disposal [4] [8]. In this policy landscape, the EPA, traditionally a regulatory agency, began championing a "benign by design" approach, creating the foundational philosophy that would later be codified in the Twelve Principles of Green Chemistry [18] [7].

The program emerged as a direct response to the limitations of earlier environmental strategies. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, the focus was predominantly on "end-of-pipe" pollution control and the remediation of environmental disasters like Love Canal [18]. By the late 1980s, a new consensus began forming among scientists, industry leaders, and international bodies like the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) that preventative solutions were more effective and economically viable than cleanup [18]. The EPA's Green Chemistry Program was thus institutionalized to embed this preventative thinking into the very fabric of chemical research and design.

The Launch of the EPA Green Chemistry Program and Early Research Grants

Institutional Framework and Key Figures

The organizational home for green chemistry within the EPA was the Office of Pollution Prevention and Toxics (OPPT), established in 1988 [18]. It was staff within this office who first coined the term "Green Chemistry" to describe this new, preventative approach [18]. A pivotal figure in the program's early development was Dr. Paul Anastas, who would later co-author the twelve principles and lead the EPA Green Chemistry Program [8]. Another key individual was Dr. Joe Breen, a 20-year staff member at the EPA who, after retiring, co-founded the independent Green Chemistry Institute (GCI) in 1997 [18].

Foundational Research Funding Initiatives

A cornerstone of the program's strategy was to stimulate scientific innovation through targeted research funding. Key early grant programs included:

- The EPA Research Grant Program (1991): Shortly after the passage of the Pollution Prevention Act, the EPA OPPT launched a research grant program in 1991 encouraging the redesign of existing chemical products and processes to reduce their impacts on human health and the environment [4]. This program provided critical early funding for academic and industrial researchers to explore alternative synthetic pathways.

- The "Alternative Synthetic Routes for Pollution Prevention" Program: This specific program, also launched in 1991, reported a new philosophy emphasizing that the correct approach was the "non-production" of hazardous substances in the first instance [7].

- Partnership with the National Science Foundation (NSF): The EPA partnered with the NSF to fund basic research in green chemistry in the early 1990s, lending scientific credibility to the field and engaging the academic research community [4]. Kenneth G. Hancock, the Chemistry Director at the NSF at the time, was a vocal public advocate for this approach as an economically viable strategy [18].

Table 1: Key Early Research Grant Programs in Green Chemistry

| Year | Grant Program / Initiative | Administering Agency | Primary Focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1991 | Research Grant Program for Redesign | EPA Office of Pollution Prevention and Toxics | Redesign of existing chemical products and processes to reduce environmental and health impacts [4]. |

| 1991 | Alternative Synthetic Routes for Pollution Prevention | EPA | Development of new synthetic methods to prevent the generation of pollution [7]. |

| Early 1990s | Basic Research Grants | EPA in partnership with the National Science Foundation (NSF) | Funding fundamental academic research aligned with green chemistry ideals [4]. |

These grant programs were instrumental in building a community of practice and generating the initial scientific evidence that green chemistry was both feasible and beneficial.

Quantitative Analysis of Early Research and Development

An analysis of U.S. patent data from 1983 to 2001 provides a quantitative measure of the early innovative activity in green chemistry. This period encompasses the formative years of the EPA program and allows for an assessment of its impact on research and development.

The data reveals that a total of 3,235 green chemistry patents were granted in the United States between 1983 and 2001 [19]. The trend in patenting activity was not static. After a period of relative stability from 1983 to 1988, the number of granted green chemistry patents began to rise significantly. The most rapid growth coincided with the late 1980s and early 1990s, a period that included the passage of the Pollution Prevention Act of 1990 and the launch of the EPA's key research programs [19].

Sectoral analysis of the patent assignments shows that while the majority of patents were assigned to the chemical sector, the university and government sectors placed a greater relative emphasis on green chemistry R&D compared to most industrial sectors [19]. This suggests that early adoption and innovation were strongly driven by public research institutions, likely fueled by the grant programs from the EPA and NSF.

Table 2: Green Chemistry Patent Analysis (1983-2001)

| Metric | Findings | Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Total Green Chemistry Patents | 3,235 US patents granted [19] | Indicator of substantial and measurable innovative output in the field. |

| Trend | Significant growth began in the late 1980s/early 1990s [19] | Coincides with key US environmental law revisions and the launch of the EPA Green Chemistry Program. |

| Sectoral Emphasis | University and government sectors had a higher relative emphasis than most industrial sectors [19] | Early drivers were often public institutions, supported by federal research funding. |

| International Context | The United States appeared to have a competitive advantage in green chemistry technology [19] | Early US policy and institutional adoption fostered innovation. |

Experimental and Methodological Approaches in Early Research

The early research funded by and associated with the EPA Green Chemistry Program was characterized by several key methodological focuses. The following workflow diagram illustrates the conceptual and experimental progression from a traditional chemical process to a redesigned, greener alternative, reflecting the core strategies promoted by early research grants.

Core Methodological Strategies

The experimental protocols that emerged from this period focused on a few core areas, which later became formalized in the twelve principles:

- Alternative Synthetic Routes: A primary goal was to develop streamlined synthetic pathways. A landmark example is Pfizer's redesign of the Sertraline (active ingredient in Zoloft) synthesis. The original three-step process was streamlined into a single step, reducing starting material use by 20-60% and eliminating the need for several toxic solvents, which cut acidic, caustic, and solid waste by hundreds of metric tons annually [19]. This exemplifies principles of Atom Economy and Safer Solvents.

- Solvent Replacement and Elimination: A major research thrust was finding substitutes for toxic and hazardous solvents. A seminal achievement was the 1996 Greener Reaction Conditions Award to Dow Chemical for developing a 100% supercritical carbon dioxide blowing agent for polystyrene foam production, replacing ozone-depleting CFCs and other hazardous hydrocarbons [20]. This work directly informed the principle of Safer Solvents and Auxiliaries.

- Catalysis: The development and use of catalytic reagents to replace stoichiometric reagents was a key research area. The 2005 Nobel Prize in Chemistry awarded for olefin metathesis was explicitly recognized as a contribution to green chemistry, as these catalytic reactions are highly atom-economical and efficient [18] [20]. This aligns with the principle of Catalysis.

- Use of Renewable Feedstocks: Research into replacing petroleum-derived feedstocks with biomass-based alternatives was another priority. The development of NatureWorks polylactide (PLA) polymers by Cargill Dow, derived entirely from annually renewable resources, demonstrated the technical and commercial viability of this approach [19]. This work is a direct application of the principle of Use of Renewable Feedstocks.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Early green chemistry research relied on a new palette of reagents and materials that enabled safer and more sustainable processes.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions in Early Green Chemistry

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Green Chemistry Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Supercritical CO₂ | Solvent and blowing agent [20] | Non-toxic, non-flammable, renewable, and replaces halogenated and volatile organic solvents. |

| Aqueous Hydrogen Peroxide | Clean oxidizing agent [20] | Decomposes to water and oxygen, avoiding metal-heavy oxidants and toxic byproducts. |

| Enzymes (e.g., Novozymes' BioPreparation) | Biocatalysts for industrial processes [19] | Highly selective, work under mild conditions, biodegradable, and reduce energy and water use. |

| Renewable Feedstocks (e.g., corn sugar) | Raw material for polymer synthesis [19] | Reduces dependence on non-renewable petroleum, often with a lower carbon footprint. |

| Water | Solvent for certain reactions [20] | Inherently non-toxic, non-flammable, and cheap. Ideal for consumer product formulations. |

The Pathway to the 12 Principles

The research initiatives, technological innovations, and methodological developments fostered by the EPA Green Chemistry Program and its partners provided the essential practical and intellectual foundation for the codification of the Twelve Principles of Green Chemistry. The principles, first published in 1998 by Paul Anastas and John C. Warner in their seminal book Green Chemistry: Theory and Practice, were not created in a vacuum [18] [7] [20]. They were a distillation of the lessons learned from the previous decade of research funded by the EPA and other agencies. The principles provided a systematic framework that organized the disparate strands of pollution prevention research—from solvent replacement and catalysis to energy efficiency and renewable feedstocks—into a coherent and actionable design philosophy [18]. The diagram below illustrates how the core concepts, validated by early research, were synthesized into the formal principles.

The principles gave the emerging field a common language and a clear, principled identity, which accelerated its adoption in academia and industry. The launch of the Presidential Green Chemistry Challenge Awards in 1995, championed by the EPA and supported by the Clinton administration, further cemented this connection by publicly highlighting technologies that embodied these principles [18]. This created a virtuous cycle: the principles guided research, and the resulting award-winning technologies validated the principles.

The early institutional adoption of green chemistry by the EPA, manifested through its research grants and the Green Chemistry Program, was a decisive factor in the development of the field. By providing critical funding, a conceptual framework, and institutional legitimacy, the EPA catalyzed a shift from pollution control to pollution prevention. The quantitative output in patents and the qualitative success of early technologies demonstrated the viability of this approach. This body of practical work and the philosophical shift it represented provided the essential real-world validation and intellectual groundwork for Paul Anastas and John Warner to synthesize the Twelve Principles of Green Chemistry. These principles, in turn, have become the enduring blueprint for designing chemical products and processes that reduce or eliminate hazards and waste, fundamentally shaping modern sustainable chemistry research and development.

The Twelve Principles of Green Chemistry represent a foundational framework for designing chemical products and processes that reduce or eliminate the use and generation of hazardous substances [7]. While formally articulated by Paul Anastas and John Warner in 1998 [4] [7], the intellectual and social origins of these principles trace back to earlier environmental movements. Rachel Carson's Silent Spring, published in 1962, served as a critical catalyst that fundamentally shifted scientific and public perception about the impact of human activity on the environment [21] [22]. This whitepaper examines the historical lineage between Carson's seminal work and the modern principles of green chemistry, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive understanding of this foundational context.

Carson's book documented the environmental harm caused by the indiscriminate use of pesticides, particularly DDT, and accused the chemical industry of spreading disinformation while challenging public officials to scrutinize industry claims more rigorously [21]. The paradigm shift initiated by Silent Spring seeded core concepts that would later be formalized into green chemistry principles, including waste prevention, inherent hazard reduction, and a recognition of the interconnectedness of chemical processes with natural systems [22].

Historical Context and the Emergence of Environmental Consciousness

Pre-Silent SpringIndustrial Landscape

The period following World War II witnessed rapid industrialization and technological optimism, characterized by the widespread application of synthetic chemicals with minimal regulatory oversight [22]. DDT (dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane), a potent insecticide developed for military use, became emblematic of this era, with U.S. production skyrocketing from 4,366 tons in 1944 to a peak of 81,154 tons in 1963 [22]. These chemicals were promoted by government agencies and corporations to increase domestic productivity and combat various ills, with little investigation of their effects on soil, water, wildlife, or humans [22].

Table 1: Historical Timeline of Key Events Leading to Green Chemistry

| Year | Event | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| 1944-1963 | Surge in DDT production in the U.S. [22] | Demonstrated scale of synthetic pesticide adoption without environmental impact assessment |

| 1962 | Publication of Silent Spring [21] | Alerted public to pesticide dangers; challenged chemical industry practices |

| 1970 | Establishment of U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) [22] [23] | Created federal agency dedicated to environmental protection |

| 1972 | Nationwide ban on DDT for agricultural uses in the U.S. [22] [23] | Demonstrated regulatory response to environmental research |

| 1990 | Pollution Prevention Act [4] | Shifted U.S. policy toward pollution prevention rather than end-of-pipe treatment |

| 1991 | EPA launched green chemistry research grants [4] | Initiated formal research funding for environmentally benign chemistry |

| 1998 | Publication of the 12 Principles of Green Chemistry [4] [7] | Provided systematic framework for designing safer chemicals and processes |

Rachel Carson's Scientific Foundation and Systemic Approach

Rachel Carson brought unique qualifications to the environmental debate, possessing both a master's degree in zoology from Johns Hopkins University and extensive experience as a writer and scientist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service [22]. This combination of scientific rigor and communicative excellence enabled her to produce work of substantial depth and credibility [22]. Her research methodology involved exhaustive examination of scientific literature, interviews with leading experts, and review of interdisciplinary materials [22].

Carson introduced several revolutionary concepts that challenged contemporary scientific orthodoxy, including that spraying chemicals to control insect populations could also kill birds that feed on dead or dying insects; that chemicals travel through environment and food chains; that chemicals accumulating in fat tissues could cause medical problems later; and that chemicals could be transferred generationally from mothers to their young [22]. These ideas revealed an understanding of systems thinking and interconnectedness that would become central to green chemistry.

Methodological Framework: From Environmental Advocacy to Chemical Principles

Analytical Approach inSilent Spring

Carson's investigative methodology established a prototype for subsequent environmental and green chemistry research. Her systematic approach can be conceptualized as an integrated workflow that connects chemical use to broad environmental and health impacts.

Diagram 1: Carson's Research Workflow

Carson did not merely document the negative effects of pesticides but advanced a systematic research framework that connected discrete chemical applications to broader ecological and human health consequences. This methodology established a precedent for the life-cycle thinking that would become integral to green chemistry principles [21] [22].

Core Conceptual Transitions fromSilent Springto Green Chemistry

The intellectual lineage between Silent Spring and the 12 Principles of Green Chemistry reveals how Carson's work initiated fundamental shifts in chemical philosophy. These transitions moved chemical practice from a singular focus on efficacy toward a more holistic consideration of environmental and health impacts.

Table 2: Conceptual Evolution from Silent Spring to Green Chemistry

| Domain | Pre-Silent Spring Paradigm | Contribution of Silent Spring | Green Chemistry Principle |

|---|---|---|---|

| Waste Management | Pollution as acceptable byproduct | Demonstrated ecological costs of persistent wastes | Prevention rather than cleanup [4] |

| Hazard Assessment | Efficacy primary concern | Revealed unintended consequences on non-target organisms | Design of safer chemicals with minimal toxicity [7] |

| Energy Considerations | Energy-intensive processes without systemic accounting | Highlighted energy flows in ecosystems | Design for energy efficiency [4] |

| Feedstock Selection | Conventional sources without environmental assessment | Questioned synthetic chemical origins | Use of renewable feedstocks [4] |

Experimental and Research Implications

Research Reagent Solutions: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives

The legacy of Silent Spring has influenced the development of research reagents and methodologies that align with green chemistry principles. The following table details both historically significant materials and contemporary alternatives relevant to researchers and drug development professionals.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials in Environmental Chemistry

| Reagent/Material | Historical/Contemporary Significance | Function/Application | Green Chemistry Alternative |

|---|---|---|---|

| DDT (Dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane) | Case study in Silent Spring; organochlorine insecticide with environmental persistence [21] | Broad-spectrum insecticide; research model for bioaccumulation studies | Biopesticides; selective insect growth regulators [22] |

| Heptachlor & Dieldrin | Investigated by Carson in USDA fire ant programs; chlorinated cyclodiene insecticides [21] | Insecticide applications; research on environmental fate | Integrated Pest Management (IPM); biological controls [21] |

| Aminotriazole | Herbicide implicated in 1959 cranberry contamination incident [21] | Non-selective herbicide; plant growth regulator | Green synthetic pathways; reduced hazard herbicides [7] |

| Alternative Solvents | Traditional solvents often volatile, flammable, toxic | Extraction, reaction media, separation | Supercritical CO₂, water, ionic liquids [4] [7] |

| Catalysts | Traditional stoichiometric reagents generate waste | Increase reaction efficiency, selectivity | Biocatalysts, heterogeneous catalysts, photocatalysts [7] |

Methodological Evolution in Environmental Impact Assessment

Carson's research pioneered methods for assessing the environmental impact of chemicals that have evolved into standardized protocols today. The following diagram illustrates the progression from her initial approach to contemporary green chemistry methodologies.

Diagram 2: Evolution of Environmental Assessment Methods

Quantitative Impact Analysis

The publication of Silent Spring and subsequent environmental regulations had measurable effects on pesticide use and policy development. The data demonstrate the tangible outcomes of the environmental consciousness that Carson helped catalyze.

Table 4: Quantitative Impacts of the Post-Silent Spring Era

| Parameter | Pre-Silent Spring Context | Post-Silent Spring Impact | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| DDT Production | 81,154 tons at peak U.S. production in 1963 [22] | Nationwide ban for agricultural uses 1972 [22] | Demonstrated regulatory response to environmental evidence |

| Policy Development | Minimal environmental regulation | Creation of EPA (1970) & passing of numerous environmental laws [22] | Institutionalized environmental protection |

| Scientific Paradigm | Chemistry focused on efficacy | Emergence of green chemistry as discipline (1990s) [4] | Fundamental shift in chemical practice |

| Public Engagement | Limited environmental awareness | Widespread debate & environmental movement growth [22] | Created constituency for environmental health |

The historical lineage between Silent Spring and the 12 Principles of Green Chemistry reveals a profound evolution in scientific thinking. Rachel Carson's work introduced core concepts that would later be formalized into green chemistry principles, including waste prevention, inherent hazard reduction, and systems thinking [22] [7]. For contemporary researchers and drug development professionals, understanding this historical context provides critical insight into the foundational values underpinning green chemistry.

The paradigm shift initiated by Carson continues to influence chemical research and development, particularly through the increased focus on green chemistry practices and sustainability [22]. The principles articulated by Anastas and Warner in 1998 provided a systematic framework for practicing chemistry aligned with Carson's vision of human activity in harmony with natural systems [4] [7]. This historical perspective demonstrates that green chemistry represents not merely a technical adjustment but a fundamental rethinking of chemical practice with roots in environmental movements that predate the formal establishment of the field.

Implementing the Framework: Core Principles and Metrics for Pharmaceutical Development

The twelve principles of green chemistry were formally introduced in 1998 by Paul Anastas and John C. Warner, providing a cohesive framework for designing chemical products and processes that reduce or eliminate the use and generation of hazardous substances [4] [7]. This foundational work, Green Chemistry: Theory and Practice, emerged from a broader environmental movement and specific policy directives. The origins of green chemistry are deeply rooted in the U.S. Pollution Prevention Act of 1990, which established a national policy favoring pollution prevention through improved design over end-of-pipe treatment and disposal [4] [12]. By 1991, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) had launched a research grant program encouraging the redesign of chemical products and processes, formally initiating what would become the green chemistry program [4]. The principles of Prevention, Atom Economy, and Less Hazardous Chemical Syntheses represent a paradigm shift from waste management to waste avoidance, fundamentally changing how chemists approach molecular design.

This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of these three core principles, framing them within their historical context and detailing their critical application in modern chemical research, with a special focus on the pharmaceutical industry. The principles are not isolated concepts but form a synergistic system where Prevention establishes the ultimate goal, Atom Economy provides a quantitative metric for synthetic efficiency, and Safer Syntheses offers the practical pathway to achieve both [4].

The First Principle: Prevention

Conceptual Framework and Historical Significance