Optimizing Solvent Selection for Lower PMI: A Strategic Guide for Sustainable Drug Development

This guide provides drug development researchers and scientists with a comprehensive framework for selecting solvents to minimize Process Mass Intensity (PMI), a key green chemistry metric.

Optimizing Solvent Selection for Lower PMI: A Strategic Guide for Sustainable Drug Development

Abstract

This guide provides drug development researchers and scientists with a comprehensive framework for selecting solvents to minimize Process Mass Intensity (PMI), a key green chemistry metric. It covers the foundational principles of green chemistry and PMI, explores practical methodologies and industry-standard tools for solvent evaluation, offers strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing processes, and outlines validation and comparative analysis techniques. By integrating these strategies, professionals can design more efficient, cost-effective, and environmentally sustainable pharmaceutical manufacturing processes.

Understanding PMI and the Principles of Green Solvent Selection

Process Mass Intensity (PMI) is a key green chemistry metric used to benchmark the efficiency and environmental performance of chemical processes, particularly in the pharmaceutical industry. It provides a comprehensive measure of the total mass of materials used to produce a unit mass of a final product. Unlike simple yield calculations, PMI accounts for all inputs, including solvents, reagents, catalysts, and process chemicals, offering a more holistic view of resource efficiency and environmental impact. The adoption of PMI has helped the pharmaceutical industry focus attention on the main drivers of process inefficiency, cost, and environment, safety, and health impact [1].

PMI represents a significant advancement over traditional efficiency metrics because it captures the full environmental footprint of a chemical process. The pharmaceutical sector has embraced PMI as a tool to drive more sustainable processes, with the first PMI benchmarking exercise conducted in 2008 and regularly continued since then [1]. This metric is especially valuable in active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) synthesis, where complex multi-step processes often generate substantial waste relative to the final product.

Calculation Methodology

Fundamental PMI Equation

The standard PMI calculation is defined as the total mass of all materials input into a process divided by the mass of the final product, typically expressed in kilograms of input per kilogram of product. The formula is:

PMI = Total Mass of Inputs (kg) / Mass of Product (kg)

This calculation encompasses all substances introduced during the synthesis, including reactants, solvents, catalysts, acids, bases, and work-up chemicals. Water may be included in the total mass, though accounting practices may vary between organizations. The resulting dimensionless number represents the efficiency of the process – a lower PMI indicates a more efficient and environmentally favorable process.

PMI Calculation in Practice

For a typical chemical reaction, the PMI calculation would account for:

- Mass of starting materials and reagents

- Mass of solvents (for reaction, extraction, and purification)

- Mass of catalysts and ligands

- Mass of acids, bases, and other additives

- Mass of work-up and purification materials

The following table illustrates a sample PMI calculation for a hypothetical API synthesis:

Table 1: Example PMI Calculation for a Representative API Synthesis Step

| Input Material | Quantity Used (kg) | Function in Process |

|---|---|---|

| Starting Material A | 1.5 | Reactant |

| Reagent B | 0.8 | Reagent |

| Solvent C | 12.0 | Reaction solvent |

| Catalyst D | 0.1 | Catalyst |

| Aqueous HCl | 5.0 | Acid work-up |

| Total Input Mass | 19.4 kg | |

| API Product Mass | 1.7 kg | |

| PMI | 11.4 |

Convergent Synthesis Calculations

For complex multi-step syntheses, especially convergent routes where multiple branches synthesize different fragments later combined into the final API, the original PMI calculator was enhanced to create the Convergent PMI Calculator [1]. This tool uses the same fundamental calculations but allows for multiple branches in single-step or convergent synthesis, providing accurate PMI values for complex synthetic routes that reflect modern pharmaceutical manufacturing.

The Role of PMI in Green Chemistry and Pharmaceutical Development

PMI as a Strategic Tool

PMI serves as a crucial strategic tool for process chemists and engineers in pharmaceutical companies who are tasked with identifying efficient routes and processes to new chemical entities [1]. The efficiency of any molecular synthesis combines both the synthetic strategy and process design optimization. PMI benchmarking has enabled significant advances in green chemistry and engineering by providing a standardized metric to compare processes and track improvements over time.

The continuing development of PMI tools represents a substantial contribution to green chemistry and engineering. The ability to benchmark and predict process mass intensity for complex organic molecules enables scientists and engineers in both academia and industry to develop better, more cost-effective, and more sustainable processes [1].

PMI in Solvent Selection and Optimization

Solvents typically constitute the largest portion of mass in pharmaceutical API synthesis, accounting for an average of 54% of chemicals and materials used in technological processes [2]. Consequently, solvent selection is paramount to PMI reduction efforts. The relationship between solvent choice and PMI is multifaceted:

Table 2: Solvent Impact on PMI and Environmental Performance

| Factor | Impact on PMI | Green Chemistry Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Solvent Mass | Direct contribution to total input mass | Reduction directly lowers PMI |

| Recyclability | Affects net material consumption | Closed-loop systems minimize waste |

| Green Solvent Alternatives | May enable mass reduction | Bio-based, water-based, supercritical fluids, and deep eutectic solvents offer environmentally friendly options [3] |

| Process Design | Influences overall material efficiency | Integration of reaction and separation steps |

The pharmaceutical sector is increasingly using green solvents as environmentally friendly substitutes for conventional solvents [3]. These include bio-based solvents (dimethyl carbonate, limonene, ethyl lactate), water-based solvents, supercritical fluids (like CO₂), and deep eutectic solvents (DES). These alternatives typically offer lower toxicity, biodegradable properties, and reduced release of volatile organic compounds, contributing to improved PMI profiles.

Advanced PMI Tools and Predictive Technologies

Computational PMI Prediction

Recent advances have integrated predictive analytics with historical data from large-scale syntheses to enable better decision-making during ideation and route design. The PMI prediction app developed by Bristol Myers Squibb in collaboration with academic partners utilizes predictive analytics and historical data to help scientists select the most efficient synthetic options prior to laboratory development [4]. This approach enables a quantitative method for predicting potential efficiencies centered around PMI of proposed synthetic routes before experimental evaluation.

When combined with machine learning Bayesian optimization (EDBO/EDBO+) to explore chemical space and identify more sustainable reaction conditions with fewer experiments, these tools significantly accelerate the advancement of "greener-by-design" outcomes [4]. For example, in one real clinical candidate example, a process that yielded 70% yield and 91% enantiomeric excess through traditional one-factor-at-a-time optimization requiring 500 experiments was surpassed by the EDBO+ platform, which achieved 80% yield and 91% enantiomeric excess in only 24 experiments [4].

Integration with Solvent Screening Protocols

Advanced solvent screening protocols complement PMI optimization by identifying environmentally friendly and cost-effective solvent options. These protocols often combine computational methods like COSMO-RS (Conductor-like Screening Model for Real Solvents) with machine learning to explore extended solvent spaces efficiently [5]. The integration of these approaches enables researchers to:

- Predict solubility in thousands of potential solvents computationally

- Identify green solvents with low environmental impact and affordability

- Verify predictions through limited, targeted experimentation

- Optimize processes with significantly reduced experimental effort

This methodology is particularly valuable given that extensive experimental screening, while most reliable, is limited by the time, effort, and costs required [5]. Machine learning approaches offer a viable alternative for exploring solvent space when supported by reliable predictive models.

Experimental Protocols for PMI Determination

Laboratory-Scale PMI Measurement Protocol

Objective: To determine the Process Mass Intensity for a chemical reaction at laboratory scale.

Materials and Equipment:

- Reaction flask with stirring capability

- Analytical balance (precision ±0.001 g)

- Heating/cooling equipment as required

- Isolation and purification equipment (filter, rotovap, etc.)

- Analytical instruments for product characterization (HPLC, NMR, etc.)

Procedure:

- Weigh all input materials including reactants, solvents, catalysts, and reagents before beginning the reaction. Record masses to the nearest 0.001 g.

- Charge materials to the reactor according to the synthetic procedure, noting any temperature control requirements.

- Monitor reaction progress using appropriate analytical techniques until completion.

- Isolate and purify the product using standard techniques (extraction, crystallization, distillation, chromatography).

- Dry the final product completely and weigh accurately.

- Calculate PMI using the formula: PMI = Total Mass of Inputs / Mass of Isolated Product.

- Document all process parameters including temperature, time, yields, and purification losses.

Notes:

- Conduct experiments in triplicate to ensure reproducibility

- Include all materials actually used in the process, including work-up and purification solvents

- Note any opportunities for solvent or reagent recovery and recycling

Protocol for PMI Optimization Through Solvent Selection

Objective: To identify solvent systems that minimize PMI while maintaining reaction performance.

Materials:

- Target substrate and reagents

- Candidate green solvents (bio-based, water-based, deep eutectic solvents, etc.)

- Traditional solvents for benchmarking

- Standard laboratory glassware and equipment

Procedure:

- Select candidate solvents based on computational screening, literature data, or green solvent selection guides.

- Set up parallel reactions using identical conditions except for the solvent system.

- Monitor reaction progress and determine reaction endpoints for each solvent system.

- Isolate products using standardized work-up procedures appropriate for each solvent.

- Determine yields, purity, and isolated masses for each condition.

- Calculate PMI values for each solvent system.

- Compare performance considering both PMI and reaction efficiency.

Analysis:

- Identify solvent systems that provide optimal balance of low PMI and high efficiency

- Consider environmental, health, and safety profiles of promising solvents

- Evaluate potential for solvent recovery and recycling

- Assess economic viability of identified systems

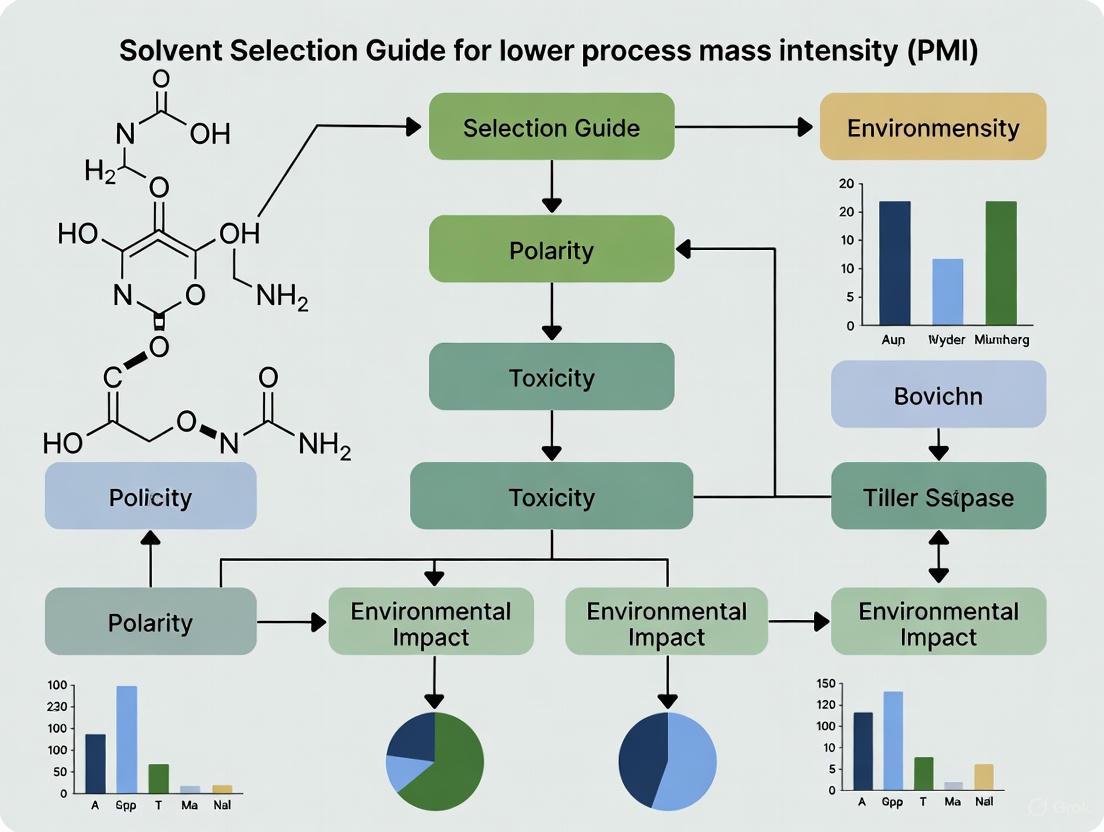

Workflow Diagrams

Diagram 1: PMI-Driven Process Development Workflow

Diagram 2: PMI Calculation Methodology

Research Reagent Solutions for PMI Optimization

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for PMI-Driven Process Development

| Tool/Reagent | Function in PMI Optimization | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| ACS GCI PMI Calculator | Standardized PMI calculation for linear and convergent syntheses | Web-based tool available through ACS Green Chemistry Institute Pharmaceutical Roundtable [1] |

| Convergent PMI Calculator | PMI calculation for complex multi-branch syntheses | Handles convergent routes common in API manufacturing [1] |

| Bio-based Solvents (e.g., ethyl lactate, limonene) | Lower environmental impact solvent options | Low toxicity, biodegradable properties, reduced VOC release [3] |

| Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) | Tunable, environmentally benign solvent systems | Created by combining hydrogen bond donors and acceptors; used in synthesis and extraction [3] |

| Supercritical Fluids (e.g., CO₂) | Alternative solvent for extraction and reactions | Selective and efficient bioactive compound extraction with minimal environmental damage [3] |

| COSMO-RS Computational Screening | Prediction of solubility and solvent performance | Enables rational solvent selection prior to experimental work [5] |

| Bayesian Optimization Platforms (e.g., EDBO/EDBO+) | Efficient experimental optimization with fewer experiments | Machine learning approach to identify optimal conditions rapidly [4] |

| Water-based Solvent Systems | Non-flammable, non-toxic alternatives | Aqueous solutions of acids, bases, or alcohols as reaction media [3] |

The 12 Principles of Green Chemistry as a Blueprint for Solvent Selection

Within pharmaceutical research and development, solvent use constitutes the largest mass input in synthetic processes, directly influencing process mass intensity (PMI) and environmental impact [6]. The 12 Principles of Green Chemistry provide a foundational framework for redesigning chemical processes to minimize their environmental footprint [7] [8]. This article delineates specific protocols and application notes for applying these principles systematically to solvent selection, supporting the broader objective of developing comprehensive solvent guides for lower PMI in active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) synthesis. By integrating quantitative green chemistry metrics with practical experimental methodologies, researchers can make informed decisions that significantly reduce waste, hazard, and resource consumption throughout the drug development lifecycle.

Principles to Practice: Analytical Framework

Quantitative Metrics for Solvent Assessment

Evaluating solvent greenness requires robust, quantitative metrics that enable objective comparison between alternatives. Key mass-based and environmental metrics provide critical data for informed decision-making.

Table 1: Core Green Chemistry Metrics for Solvent Evaluation

| Metric | Calculation | Interpretation | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Process Mass Intensity (PMI) | Total mass of inputs (kg) / Mass of product (kg) [6] | Lower values indicate higher efficiency; Ideal PMI = 1 | Primary metric for overall process efficiency; industry benchmarking |

| E-Factor | Total waste (kg) / Product (kg) [9] | Lower values preferable; Pharmaceutical industry often 25-100+ [9] | Waste production assessment; PMI = E-Factor + 1 [9] |

| Carbon Footprint | kg CO₂ produced per kg product [10] | Quantifies climate change impact | Lifecycle assessment from raw material to disposal [10] |

| Cumulative Energy Demand (CED) | Energy for production + Use - Recycling/Incineration credits [11] | Lower values preferable; Identifies optimal end-of-life strategy | Energy impact assessment; Informs recycling vs. incineration decisions [11] |

Solvent Selection Guides and Tools

Several structured approaches facilitate solvent evaluation and substitution based on environmental, health, and safety (EHS) profiles:

- ACS GCI Pharmaceutical Roundtable Solvent Selection Tool: This interactive tool enables solvent selection based on principal component analysis of 70 physical properties across 272 solvents, incorporating health, environmental impact, and lifecycle assessment data [12] [6].

- ETH Zurich EHS Assessment: A scoring system evaluating environmental, health, and safety criteria, where lower scores indicate greener solvents (e.g., alcohols and esters score better than hydrocarbons) [11].

- Rowan University Solvent Greenness Index: An alternative approach incorporating 12 environmental parameters with scores from 0 (most green) to 10 (least green), providing differentiation between structurally similar solvents [11].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Systematic Solvent Evaluation and Substitution

Purpose: To systematically identify and evaluate greener solvent alternatives for a specific chemical reaction or unit operation.

Materials:

- Test compounds (API intermediates)

- Candidate solvent panel (including conventional and potential alternatives)

- ACS GCI Solvent Selection Tool [12] or CHEM21 Selection Guide [6]

- Laboratory equipment for solubility and reaction testing

Methodology:

- Characterize Requirements: Define critical solvent properties for the application (e.g., solubility parameters, polarity, boiling point, water miscibility) [13].

- Screen Using Selection Guide: Input requirements into solvent selection tool to identify potential alternatives with improved EHS profiles [12] [11].

- Benchmark Against Incumbents: Compare candidate solvents against conventional options using PMI and E-Factor calculations [9] [6].

- Experimental Validation:

- Conduct small-scale (1-10 mL) solubility tests with target compounds

- Perform reaction kinetics studies comparing conversion rates and selectivity

- Assess separation and recovery feasibility through distillation or extraction studies

- Lifecycle Assessment: Calculate carbon footprint and cumulative energy demand for top candidates, considering production, recycling, and disposal pathways [10] [11].

Data Analysis: Compile results into a comparative assessment matrix scoring each solvent across technical performance, EHS criteria, and lifecycle impacts to identify the optimal balance of properties.

Protocol 2: PMI Optimization Through Solvent Reduction and Recycling

Purpose: To minimize PMI through solvent reduction strategies and recycling implementation.

Materials:

- Reaction system with known PMI baseline

- Equipment for solvent recovery (distillation, membrane separation, or extraction)

- Analytical instrumentation for solvent purity assessment (GC, HPLC)

Methodology:

- Baseline Establishment: Calculate current PMI using the formula: PMI = Total mass of inputs / Mass of product [6].

- Solvent Intensity Reduction:

- Optimize reaction concentration through controlled substrate addition

- Evaluate solvent-free conditions where applicable [13]

- Implement in-line concentration monitoring to minimize excess solvent use

- Recovery System Design:

- Establish distillation protocols for solvent purification and reuse

- Determine purity specifications for recycled solvent suitability

- Develop analytical methods to monitor solvent quality and potential contaminant buildup

- Lifecycle Optimization: Apply the waste minimization hierarchy: Avoid → Minimize → Recycle → Dispose [13].

Data Analysis: Track PMI improvement throughout optimization stages and calculate net environmental benefit using the ETH Zurich CED methodology to confirm the optimal end-of-life strategy [11].

Implementation Framework

Decision Pathway for Solvent Selection

The following diagram illustrates the systematic decision pathway for applying green chemistry principles to solvent selection:

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Green Solvent Implementation

| Category | Specific Examples | Function | Green Chemistry Principle Addressed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Green Solvent Candidates | 2-MeTHF, Cyrene, dimethyl isosorbide [11] | Bio-based solvent alternatives | Principle 5 (Safer Solvents), Principle 7 (Renewable Feedstocks) |

| Assessment Tools | ACS GCI Solvent Selection Tool, Rowan University Solvent Index [12] [11] | Quantitative solvent evaluation | Principle 2 (Atom Economy), Principle 12 (Accident Prevention) |

| Analytical Instrumentation | GC-MS, HPLC, in-line PAT tools [9] | Solvent purity analysis, reaction monitoring | Principle 11 (Real-Time Analysis) |

| Catalytic Systems | Immobilized enzymes, heterogeneous catalysts [10] [6] | Enable alternative solvent use, improve selectivity | Principle 9 (Catalysis) |

The 12 Principles of Green Chemistry provide a robust, actionable framework for transforming solvent selection practices in pharmaceutical research and development. By integrating quantitative metrics like PMI and E-Factor with systematic assessment protocols and advanced solvent selection tools, researchers can significantly reduce the environmental impact of synthetic processes while maintaining efficiency and efficacy. The experimental protocols and decision frameworks presented herein offer practical pathways for implementing these principles, supporting the broader objective of developing sustainable solvent selection guides for lower PMI in API synthesis. As green chemistry continues to evolve, the integration of innovative solvent systems, biocatalysis in non-conventional media [10], and predictive analytics for greener-by-design synthesis [4] will further advance the sustainability of pharmaceutical manufacturing.

In the pursuit of more sustainable pharmaceutical manufacturing, solvent use presents a critical challenge. Solvents typically constitute the largest mass input in synthetic processes, making them the primary contributor to process mass intensity (PMI) and a significant source of manufacturing waste [6]. The pharmaceutical industry is notably resource-intensive, accounting for approximately 5% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions annually, with Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) manufacturing alone responsible for about 25% of emissions from pharmaceutical companies [14]. This environmental burden is compounded by economic factors; the pharmaceutical solvent market is projected to reach $5.61 billion by 2032, escalating both production costs and waste disposal challenges [14]. Within this context, addressing solvent waste through recovery, recycling, and informed selection becomes not merely an operational consideration but a fundamental requirement for sustainable drug development.

Quantitative Impact: The Data Behind Solvent Waste

The Scale of Solvent Use and Waste

The following table summarizes key quantitative data highlighting the dominant role of solvents in pharmaceutical manufacturing waste:

Table 1: Environmental and Economic Impact of Pharmaceutical Solvents

| Metric | Impact Value | Context & Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Global Pharma GHG Emissions | 5% of total global emissions | Annual contribution [14] |

| API Manufacturing Share | 25% of pharma company emissions | From overall pharma carbon footprint [14] |

| Current Solvent Recycling Rate | ~35% | Majority of spent solvents still incinerated [14] |

| CO₂e from Solvent Incineration | 2-4 kg CO₂e/kg solvent | End-of-life emissions [14] |

| CO₂e from Solvent Recycling | 0.1-0.5 kg CO₂e/kg solvent | Through distillation; significantly lower than incineration [14] |

| Potential Cost Savings | Up to 90% | Reduction in new solvent purchase and disposal costs [14] |

Common Solvents in Pharmaceutical Manufacturing

Pharmaceutical processes utilize various solvents, many classified as hazardous waste under regulatory frameworks like the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA). The table below lists common solvents encountered in pharmaceutical manufacturing, particularly those listed as "F-listed" wastes from solvent procedures [14]:

Table 2: Common Solvents in Pharmaceutical Processes and Hazardous Waste Categories

| Solvent Name | Typical Applications | Hazardous Waste Category |

|---|---|---|

| Acetone | Extraction, cleaning | F-listed spent solvent [14] |

| Methanol | Synthesis, crystallization | F-listed spent solvent [14] |

| Ethyl Acetate | Extraction, chromatography | F-listed spent solvent [14] |

| Toluene | Reaction medium, azeotropic drying | F-listed spent solvent [14] |

| Xylene | Histology, synthesis | F-listed spent solvent [14] |

| n-Butyl Alcohol | Synthesis, extraction | F-listed spent solvent [14] |

| Cyclohexanone | Solvent for polymers, resins | F-listed spent solvent [14] |

Solvent Recovery and Recycling: Protocols and Applications

Protocol: Experimental Solvent Testing for Crystallization

Crystallization is a critical purification step in API manufacturing. Selecting an appropriate solvent is paramount for yield and purity. The following protocol provides a systematic method for testing single solvents for crystallization [15].

Application Note: This method is ideal for small-scale R&D during process development to identify viable crystallization solvents before scaling up.

Step 1: Initial Solubility Screening

- Place 100 mg of the target solid in a test tube.

- Add 3 mL of the candidate solvent (this aligns with the standard solubility guideline of ~3g/100mL) [15].

- Flick the test tube vigorously to mix at room temperature.

- Success Indicator: The solid should not dissolve completely at room temperature. If it dissolves, the solvent is unsuitable for crystallization as the compound must be insoluble when cold.

Step 2: Heating and Dissolution

- Immerse the test tube containing the solid-solvent mixture into a hot water bath or steam bath, bringing it to a boil.

- Success Indicator: The solid dissolves completely in the hot solvent. If it remains undissolved, the solvent will not work.

Step 3: Cooling and Crystallization

- Allow the solution to cool gradually to room temperature.

- Subsequently, submerge it in an ice bath for 10-20 minutes to induce crystallization.

- Success Indicator: Most of the solid recrystallizes. If few or no crystals form, try scratching the inner vessel surface with a glass stirring rod to initiate nucleation. Persistent failure to crystallize indicates solvent incompatibility.

Protocol: On-Site Solvent Recovery via Distillation

Distillation is the most common method for industrial-scale solvent recovery, enabling the reuse of spent solvents, which reduces PMI and waste disposal costs [16] [17].

Application Note: This protocol outlines the general stages for implementing an on-site distillation recovery system for single-solvent or multi-component solvent waste streams.

Step 1: Collection and Segregation

- Collect spent solvents from process equipment through draining or vacuum systems.

- Segregate solvent types where possible to simplify the recovery process. For mixed streams, advanced separation is required [16].

Step 2: Separation via Distillation

- Transfer the waste solvent to a distillation unit.

- Heat the mixture to evaporate the solvent. The vapors are then condensed and collected in a separate container [16].

- For multi-component mixtures, fractional distillation is employed. This involves a column that separates solvents based on their different boiling points, collecting different fractions at various stages [16] [17]. In complex pharmaceutical processes involving water and organics, a two-section column is often used: a stripping section to remove water and a rectification section to purify the solvent [17].

Step 3: Purification

- The recovered solvent may undergo further purification to remove trace contaminants using techniques like adsorption or filtration, ensuring it meets the purity requirements for reuse [16].

Step 4: Reuse/Recycling

- The purified solvent can be reintroduced into the production process or recycled for other applications, closing the manufacturing loop [16].

The following workflow diagram visualizes the decision path for solvent recovery and recycling:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key tools and resources essential for scientists aiming to optimize solvent use and reduce PMI.

Table 3: Essential Tools for Green Solvent Selection and Process Analysis

| Tool / Resource | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| ACS GCIPR Solvent Selection Guide | An interactive tool based on Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of 70+ physical properties of 272 solvents. It aids in selecting or replacing solvents based on polarity, H-bonding, EHS, and LCA profiles [6] [12]. |

| Process Mass Intensity (PMI) Calculator | A key green metric, PMI is calculated as the total mass of inputs (kg) per mass of product (kg). This calculator helps track and benchmark the resource efficiency of synthetic routes [6]. |

| PMI Prediction Tool | Predicts the mass efficiency of proposed synthetic routes using a dataset of nearly 2,000 reactions, allowing virtual screening of different routes for efficiency during R&D [6]. |

| On-Site Solvent Recycler (Distillation Unit) | A system designed to recover and purify spent solvents directly at the facility, drastically reducing new solvent purchases and hazardous waste generation [16] [14]. |

| Continuous Distillation Laboratory | Provides small-scale testing (e.g., using modular glass equipment) to de-risk and optimize solvent recovery processes before costly full-scale implementation [17]. |

The dominance of solvents in pharmaceutical manufacturing waste is an inescapable reality, but it also presents a significant opportunity. By understanding the quantitative impact detailed in these application notes, research scientists and drug development professionals can take decisive action. Integrating robust experimental protocols for solvent selection, implementing on-site recovery technologies like distillation, and leveraging modern tools for solvent substitution and PMI analysis form a comprehensive strategy. This multi-faceted approach directly addresses the core thesis that a strategic solvent selection guide is fundamental to lower PMI research, ultimately leading to more sustainable, cost-effective, and environmentally responsible pharmaceutical manufacturing.

Environmental, Health, and Safety (EHS) Criteria for Assessing Solvent Greenness

Within pharmaceutical development and broader chemical research, solvents often constitute the largest mass input in a synthetic process. Their selection is therefore critical for developing sustainable processes with lower Process Mass Intensity (PMI). A rigorous assessment based on Environmental, Health, and Safety (EHS) criteria provides a foundational strategy for reducing the environmental footprint of chemical manufacturing [18] [11]. This document outlines the core EHS principles, standardized assessment protocols, and available tools to guide researchers in selecting greener solvents, directly contributing to the goals of lower PMI research.

The push for greener solvents is further driven by evolving regulatory landscapes. For instance, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has implemented new rules restricting many uses of methylene chloride due to health risks such as neurotoxicity and cancer [19]. Similarly, the European REACH regulation places restrictions on solvents like toluene, chloroform, and DCM [11]. These regulatory actions underscore the necessity of proactively integrating EHS criteria into solvent selection to ensure both worker safety and long-term process viability.

Core EHS Principles and Criteria for Solvent Assessment

A comprehensive EHS assessment evaluates a solvent's impact across three interconnected domains. The guiding principle is that a truly green solvent must perform favorably in all three areas, not just one or two [11].

Environmental Criteria

This category assesses the solvent's impact on ecosystems and the environment throughout its life cycle.

- Biodegradability: The ease with which the solvent breaks down in the environment. Solvents that persist can accumulate and cause long-term ecological damage [18] [20].

- Aquatic Toxicity: The harmful effects of the solvent on aquatic life. This is often assessed through tests on fish, daphnia, and algae [18] [11].

- Ozone Depletion Potential (ODP): The potential for a solvent to contribute to the destruction of the stratospheric ozone layer. While many classic ozone-depleting solvents are now banned, this remains a key consideration [11].

- Global Warming Potential (GWP): The contribution of a solvent to climate change, often related to its volatility and atmospheric lifetime [11].

- Volatile Organic Compound (VOC) Status: VOCs contribute to ground-level smog formation and can have direct health impacts. Reducing VOC emissions is a key regulatory driver [20] [19].

Health Criteria

This category focuses on the direct effects of solvent exposure on human health.

- Acute Toxicity: Typically measured as the lethal dose (LD50) for 50% of a test population. Solvents with an LD50 greater than 2000 mg/kg are generally considered low toxicity [18].

- Carcinogenicity: The potential to cause cancer. Solvents like benzene are well-known carcinogens [11].

- Reproductive Toxicity (Reprotoxicity): The ability to impair sexual function and fertility or cause damage to the unborn child. Solvents such as N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF) and N-Methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP) are often classified as reprotoxic [11].

- Mutagenicity: The potential to cause permanent changes in genetic material.

- Organ Toxicity: The ability to cause damage to specific organs, such as the liver or nervous system, through prolonged or repeated exposure [19].

Safety Criteria

This category addresses the physical hazards associated with handling and storing the solvent.

- Flammability: Determined by properties like flash point. A lower flash point indicates higher flammability risk. For example, the CHEM21 guide assigns a higher hazard score for solvents with flash points below -20 °C [21].

- Explosive Potential: This includes the tendency to form peroxides upon exposure to air (e.g., as seen with diethyl ether) or having a high energy of decomposition [21].

- Volatility: High volatility, indicated by a low boiling point, increases inhalation exposure risks and the potential for atmospheric emissions [21] [11].

Table 1: Key EHS Criteria and Their Assessment Parameters

| EHS Domain | Criteria | Key Assessment Parameters / Standards |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental | Biodegradability | Inherent/readily biodegradable; OECD test guidelines |

| Aquatic Toxicity | LC50 (fish), EC50 (daphnia), GHS categories (H400, H410, H412) [21] | |

| Ozone Depletion | Ozone Depletion Potential (ODP); regulated under Montreal Protocol [11] | |

| Volatility | Boiling point, VOC status | |

| Health | Acute Toxicity | LD50 (oral, dermal), GHS classification [18] [21] |

| Carcinogenicity | IARC classification; GHS H350, H351 | |

| Reproductive Toxicity | GHS H360, H361 | |

| Organ Toxicity | Specific target organ toxicity (STOT) | |

| Safety | Flammability | Flash point, auto-ignition temperature; GHS flammability categories [21] |

| Reactivity/Stability | Peroxide formation, energy of decomposition |

Established Solvent Selection Guides and Tools

Several organizations have developed solvent selection guides that synthesize EHS data into user-friendly formats. These tools are invaluable for making rapid, informed comparisons.

The CHEM21 Selection Guide

The CHEM21 guide is a widely recognized tool developed by a European public-private partnership, including pharmaceutical companies and academic institutions. It scores solvents based on Safety, Health, and Environmental impacts, aligning with the Globally Harmonized System (GHS) of Classification and Labelling [21]. It categorizes solvents as "Recommended," "Problematic," or "Hazardous," providing a clear, actionable ranking for chemists.

- Safety Scoring: Based primarily on flash point and boiling point, with additional points for hazards like low auto-ignition temperature or peroxide formation [21].

- Health Scoring: Uses GHS hazard statements. A point is added if the solvent's boiling point is below 85°C, increasing exposure risk [21].

- Environmental Scoring: Based on a combination of boiling point and GHS environmental hazard statements (e.g., H400: very toxic to aquatic life) [21].

ACS GCI Pharmaceutical Roundtable Solvent Selection Tool

This interactive web-based tool allows for solvent selection based on a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of 70 physical properties. It includes 272 solvents and provides data on health impacts, air/water impacts, life-cycle assessment, and ICH solvent classes [12]. It helps identify solvents with similar properties but potentially greener EHS profiles.

GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) Solvent Sustainability Guide

The GSK guide uses a comprehensive numerical ranking system across multiple EHS and life-cycle categories. While highly detailed, its complexity can make it challenging to trace how individual data points contribute to the final score [18]. It has, however, served as a valuable dataset for training machine learning models to predict solvent greenness [22].

Table 2: Comparison of Major Solvent Selection Guides

| Guide / Tool | Primary Scoring/Categorization Method | Key Strengths | Context in Lower PMI Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| CHEM21 | Recommended, Problematic, Hazardous | Aligns with GHS; user-friendly, clear categories | Promotes inherently safer solvents, reducing waste from controls and incidents |

| ACS GCIPR Tool | PCA mapping of physical properties | Interactive; large database (272 solvents); links properties to EHS | Identifies drop-in replacements with lower EHS impact, minimizing re-optimization |

| GSK Solvent Guide | Comprehensive numerical ranking | Very detailed assessment; incorporates LCA | Holistic view of solvent impact from production to disposal, informing total PMI |

| GEARS Metric | Quantitative scoring (e.g., 0-3 pts per parameter) [18] | Includes 10 parameters (EHS, functional, economic); transparent | Directly links solvent properties to process efficiency and waste generation |

Experimental Protocol: EHS Assessment for Solvent Selection

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for evaluating and comparing solvents for a specific chemical process using established EHS criteria and selection guides.

Protocol: Comparative EHS Profiling of Candidate Solvents

1. Define Process Requirements

- Objective: Identify the key physical and chemical properties required for the specific chemical reaction or unit operation (e.g., extraction, chromatography).

- Procedure:

- Determine the necessary solvent properties such as polarity, boiling point for separation, hydrophilicity/lipophilicity (log P), and chemical compatibility with reactants and products.

- Use tools like the ACS GCIPR Solvent Selection Tool to map the property space and identify a longlist of candidate solvents that meet the functional requirements [12].

2. Compile EHS Data

- Objective: Gather comprehensive EHS data for each candidate solvent on the longlist.

- Procedure:

- For each solvent, consult Safety Data Sheets (SDS), focusing on Sections 2 (Hazards Identification), 9 (Physical and Chemical Properties), 11 (Toxicological Information), and 12 (Ecological Information).

- Extract key data points: GHS hazard statements (H-phrases), LD50, flash point, boiling point, and biodegradability information.

- Utilize public databases such as eChemPortal and REACH dossiers for additional validated data [18].

3. Apply Solvent Selection Guides

- Objective: Rank the candidate solvents based on standardized EHS assessments.

- Procedure:

- Consult the CHEM21 Selection Guide to classify each solvent as "Recommended," "Problematic," or "Hazardous" [21].

- Input the solvents into the ACS GCIPR Solvent Selection Tool to compare their positions on the PCA map and review their impact categories (Health, Air, Water, LCA) [12].

- For a more granular analysis, refer to the GSK Solvent Sustainability Guide or the newer GEARS metric, which provides a quantitative score across parameters like toxicity, flammability, and recyclability [18].

4. Perform a Comparative Analysis and Selection

- Objective: Synthesize the data to select the greenest solvent that meets the process requirements.

- Procedure:

- Create a comparison table summarizing the EHS scores and classifications from the various guides for all candidate solvents.

- Prioritize solvents categorized as "Recommended" by CHEM21 and located in the greener zones of the ACS GCIPR tool.

- If the top EHS candidates are functionally suitable, proceed with laboratory testing. If not, iterate by considering solvents with similar properties from the PCA map but with a greener EHS profile.

5. Life-Cycle and Waste Considerations

- Objective: Ensure the final selection supports a low PMI and overall process sustainability.

- Procedure:

- Factor in the solvent's recyclability and the energy required for its recovery (distillation vs. incineration). For example, recycling solvents like THF can significantly reduce the net cumulative energy demand [11].

- Calculate the Process Mass Intensity (PMI) for the proposed process, accounting for all solvent mass input relative to the product mass. The ACS GCIPR PMI calculator can be used for this purpose [6].

Diagram 1: EHS Solvent Selection Workflow. This diagram outlines the iterative process for selecting a green solvent based on EHS criteria and functional requirements.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for EHS-Driven Solvent Selection

| Tool / Resource Name | Function / Purpose | Relevance to EHS & Lower PMI |

|---|---|---|

| CHEM21 Selection Guide | Provides a quick, GHS-aligned classification of solvents as Recommended, Problematic, or Hazardous [21]. | Enables rapid identification of inherently safer solvents, reducing hazardous waste streams. |

| ACS GCIPR Solvent Tool | Interactive tool for mapping solvents by physical properties and viewing EHS impact categories [12]. | Identifies functionally similar, greener solvent alternatives to minimize re-optimization efforts and PMI. |

| GSK Solvent Sustainability Guide | A comprehensive numerical ranking system for solvent greenness [18] [6]. | Offers a detailed, holistic assessment of solvent sustainability, informing long-term process design. |

| REACH Dossiers / eChemPortal | Official databases for regulatory chemical data, including hazard and risk assessments [18]. | Provides authoritative, validated data for conducting rigorous EHS assessments. |

| PMI Calculator (ACS GCIPR) | Calculates the Process Mass Intensity of a synthetic route, accounting for all material inputs [6]. | Quantifies the mass efficiency of a process, directly measuring the success of green solvent selection in reducing waste. |

| GreenSolventDB | A large public database of green solvent metrics generated via machine learning predictions [22]. | Expands the universe of assessable solvents beyond traditional guides, enabling discovery of novel green options. |

Integrating a rigorous, multi-parameter EHS assessment into solvent selection is a non-negotiable practice for modern, sustainable drug development. By leveraging established frameworks like the CHEM21 guide, interactive tools from the ACS GCIPR, and emerging metrics like %Greenness [23], researchers can make informed decisions that significantly reduce Process Mass Intensity. This methodology aligns with regulatory trends, mitigates workplace hazards, and minimizes environmental impact, thereby advancing the core objectives of green chemistry and lower PMI research. The future of solvent selection will be further enhanced by data-driven approaches, including machine learning models that can predict the greenness of a vast array of solvents, accelerating the discovery and adoption of truly sustainable alternatives [22].

Cumulative Energy Demand (CED)

Cumulative Energy Demand represents the total amount of primary energy consumed throughout the complete lifecycle of a product, process, or service, accounting for all direct and indirect energy inputs from raw material extraction to end-of-life disposal [24]. In pharmaceutical research and development, CED provides a comprehensive metric to quantify the true energy burden of manufacturing processes, enabling scientists to identify hotspots for improvement in resource efficiency.

CED calculations are typically performed within the standardized framework of Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) and are expressed in megajoules (MJ) of primary energy, categorized by energy source types [25]. This methodology helps researchers move beyond simple operational energy efficiency to understand the complete energy footprint embedded in synthetic routes, which is particularly important when aiming to reduce Process Mass Intensity (PMI) in active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) manufacturing.

Solvent Footprint

The Solvent Footprint encompasses the aggregated environmental, health, and safety impacts of solvents throughout their life cycle, including raw material acquisition, manufacturing, use, recycling, and treatment [26]. solvents represent the largest mass input in most synthetic pharmaceutical processes, making their footprint a critical concern for sustainable process design. Key impact categories for solvent footprint assessment include global warming potential, photochemical ozone creation, human toxicity, aquatic ecotoxicity, and resource depletion [26] [12].

Integrating CED and solvent footprint analysis provides a holistic sustainability assessment framework for pharmaceutical development teams, enabling informed solvent selection decisions that align with green chemistry principles and corporate sustainability goals while maintaining process efficiency and product quality.

Quantitative Data and Impact Assessment

CED Categories and Characterization

Table 1: CED Impact Categories and Units [25]

| Category Name | Unit |

|---|---|

| Non-renewable, biomass | MJ |

| Non-renewable, fossil | MJ |

| Non-renewable, nuclear | MJ |

| Renewable, biomass | MJ |

| Renewable, water | MJ |

| Renewable, wind, solar, geothermal | MJ |

| Total | MJ |

| Total, non-renewable | MJ |

| Total, renewable | MJ |

Life Cycle Impact Assessment Methods for Solvent Evaluation

Table 2: LCIA Methods for Comprehensive Solvent Footprint Assessment [27]

| Method | Developer | Key Features | Applicable Impact Categories |

|---|---|---|---|

| IPCC | Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change | Global warming potential factors (GWP100, GWP20) | Carbon footprint, Climate change |

| ReCiPe | RIVM, Radboud University, Leiden University, Pré Consultants | Midpoint and endpoint assessment; multiple cultural perspectives | Human health, Ecosystem quality, Natural resources |

| EF v3.1 | European Commission | Standardized for Environmental Footprint studies | Multiple impact categories including toxicity, resource use |

| USEtox | UNEP/SETAC | Consensus model for toxicity assessment | Human toxicity, Freshwater ecotoxicity |

| Cumulative Energy Demand | ecoinvent | Primary energy demand assessment | Total energy resource consumption |

| Ecological Scarcity | Swiss Federal Office for the Environment | Distance-to-target method; eco-points (UBP) | Multiple aggregated impact categories |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for CED Calculation of Pharmaceutical Processes

Objective: To determine the cumulative energy demand of API synthesis routes to identify energy hotspots and guide PMI reduction strategies.

Materials and Equipment:

- Life Cycle Assessment software (e.g., openLCA, SimaPro, GaBi)

- Ecoinvent database or similar life cycle inventory data

- Process mass balance data for all synthetic steps

- Energy monitoring equipment for manufacturing processes

Procedure:

Goal and Scope Definition:

- Define system boundaries (cradle-to-gate recommended for API synthesis)

- Determine functional unit (e.g., per kg of final API)

- Identify data requirements and data quality objectives

Life Cycle Inventory Compilation:

- Collect primary data on energy consumption for each process step

- Gather secondary data for upstream materials from LCA databases

- Document transportation distances and modes for all material inputs

- Quantify solvent and reagent inputs and outputs using mass balances

CED Calculation:

- Apply CED characterization factors to all energy and material flows

- Sum energy inputs across all lifecycle stages within system boundaries

- Allocate energy burdens for multi-functional processes using mass or economic allocation

- Categorize results by energy source type (renewable vs. non-renewable)

Interpretation and Hotspot Analysis:

- Identify process steps contributing most significantly to total CED

- Compare CED across different synthetic routes for the same API

- Perform sensitivity analysis on key parameters and allocation methods

- Document limitations and data quality assessment

Data Analysis: Calculate PMI (Process Mass Intensity) using the formula:

Integrate CED and PMI results to identify both mass and energy efficiency improvement opportunities.

Protocol for Solvent Footprint Assessment

Objective: To evaluate and compare the environmental footprint of different solvent options for specific chemical transformations to guide sustainable solvent selection.

Materials and Equipment:

- ACS GCI Pharmaceutical Roundtable Solvent Selection Tool [12]

- Solvent life cycle inventory data

- Environmental, health, and safety (EHS) assessment criteria

- Chemical compatibility testing equipment

Procedure:

Solvent Function Requirement Analysis:

- Define chemical compatibility requirements for the reaction system

- Identify physical property constraints (boiling point, polarity, solubility parameters)

- Determine purification and recovery requirements

Life Cycle Impact Assessment:

- Select appropriate LCIA methods based on priority impact categories (Table 2)

- Calculate characterization factors for key environmental impacts

- Apply USEtox methodology for human and ecotoxicity impacts [27]

- Include direct emissions from solvent use and upstream production impacts

EHS Profiling:

Green Solvent Alternative Assessment:

- Screen bio-based solvents (ethyl lactate, dimethyl carbonate, limonene) [3]

- Evaluate water-based systems where applicable

- Consider supercritical fluids (CO₂) and deep eutectic solvents for specialized applications

- Assess technical performance through laboratory testing

Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis:

- Weight environmental, technical, economic, and regulatory factors

- Apply the ACS GCI Solvent Selection Tool for comparative assessment [12]

- Rank solvent alternatives using quantitative scoring methodology

Validation: Confirm laboratory performance of selected green solvents through reaction optimization and process efficiency measurements. Monitor PMI reduction and document sustainability improvements.

Visualization and Workflow Diagrams

CED Assessment Workflow

Integrated Solvent Selection Framework

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for CED and Solvent Footprint Assessment

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| ACS GCI Solvent Selection Tool [12] | Interactive solvent selection based on PCA of physical properties and environmental data | Replacement of hazardous solvents with greener alternatives |

| Ecoinvent Database [27] | Provides life cycle inventory data for energy and materials | CED calculation and environmental footprint assessment |

| ReCiPe 2016 LCIA Method [27] | Midpoint and endpoint impact assessment with multiple cultural perspectives | Comprehensive environmental impact evaluation |

| USEtox Model [27] | Characterization of human and ecotoxicity impacts | Toxicity footprint assessment for solvent selection |

| Process Mass Intensity Calculator [6] | Determination of PMI from raw material inputs | Resource efficiency benchmarking and monitoring |

| Green Solvent Guides [6] [3] | Reference for bio-based and less hazardous solvent options | Initial screening of potential green solvent alternatives |

Implementation Strategy for Pharmaceutical Development

Successful integration of CED and solvent footprint analysis into pharmaceutical development requires a systematic approach that aligns with existing workflow. Development teams should establish baseline CED and PMI metrics for current processes, then set reduction targets aligned with corporate sustainability goals. The ACS GCI Pharmaceutical Roundtable solvent selection guide provides a validated starting point for identifying preferred solvents and those to be avoided or replaced [6].

For synthetic route design, researchers should prioritize chemical transformations that minimize energy-intensive processes and enable the use of green solvents. Early-stage incorporation of life cycle thinking allows for significant reduction of environmental impacts before process lock-in occurs. Regular monitoring of PMI and CED metrics throughout development provides quantitative data to track improvement and demonstrate the business case for sustainable chemistry practices.

The transition to green solvents, including bio-based alternatives like ethyl lactate and dimethyl carbonate, deep eutectic solvents, and supercritical fluids, represents a significant opportunity for reducing both CED and solvent footprint in pharmaceutical manufacturing [3]. However, technical performance, scalability, and economic viability must be carefully evaluated alongside environmental benefits to ensure practical implementation.

Practical Tools and Modern Techniques for Greener Solvent Implementation

Leveraging the ACS GCI Pharmaceutical Roundtable's Solvent Selection Guide

The American Chemical Society Green Chemistry Institute’s Pharmaceutical Roundtable (ACS GCIPR) provides a comprehensive framework for solvent selection to advance sustainability in pharmaceutical research and development. Solvents constitute approximately 50% of the total mass of materials used to manufacture active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), making their judicious selection critical for reducing Process Mass Intensity (PMI) [28]. The ACS GCIPR specifically endorses the CHEM21 Solvent Selection Guide as a key resource, which classifies solvents based on safety, health, and environmental (SHE) criteria to help researchers identify problematic solvents and select preferable alternatives [29] [30] [28]. This guide is instrumental in systematically reducing the environmental footprint of chemical processes, directly contributing to lower PMI in pharmaceutical synthesis.

Key Tools and Guides

The CHEM21 Solvent Selection Guide

The CHEM21 guide employs a standardized methodology to evaluate and rank solvents, providing a clear, color-coded classification system [30]. It categorizes solvents as "recommended," "problematic," or "hazardous" based on combined safety, health, and environmental scores, enabling rapid assessment and substitution decisions [30].

Interactive Solvent Selection Tool

The ACS GCIPR Solvent Selection Tool is an interactive platform based on Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of 70 physical properties from 272 research, process, and next-generation green solvents [12]. This tool visualizes solvents in a property space where proximity indicates similarity, facilitating the identification of alternatives with comparable chemical functionality but improved SHE profiles [12] [6]. The tool incorporates additional data on functional groups, environmental impact categories, ICH solvent classes, and plant accommodation parameters, supporting holistic solvent choices [12].

Quantitative Solvent Assessment Criteria

Safety, Health, and Environmental Scoring

The CHEM21 guide employs a precise scoring system where SHE criteria are rated from 1-10, with higher scores indicating greater hazard [30]. The overall classification derives from the most stringent combination of these scores according to the following table:

Table 1: CHEM21 Solvent Ranking Criteria [30]

| Score Combination | Ranking by Default |

|---|---|

| One score ≥ 8 | Hazardous |

| Two "red" scores (7-10) | Hazardous |

| One score = 7 | Problematic |

| Two "yellow" scores (4-6) | Problematic |

| Other combinations | Recommended |

Safety scores primarily derive from flash point (FP), with contributions from auto-ignition temperature (AIT), resistivity, and peroxide formation potential [30]:

Table 2: Safety Scoring Criteria [30]

| Basic Safety Score | Flash Point (°C) | GHS Statements |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | > 60 | -- |

| 3 | 23 to 60 | H226 |

| 4 | 22 to 0 | -- |

| 5 | -1 to -20 | -- |

| 7 | < -20 | H225 or H224 |

Health scores incorporate the most stringent GHS H3xx statements with adjustments for boiling point, while environment scores consider both volatility (boiling point) and GHS H4xx statements [30].

Classified Solvent Examples

Table 3: CHEM21 Solvent Classifications and Properties (Selected Examples) [30]

| Family | Solvent | BP (°C) | FP (°C) | Safety Score | Health Score | Env. Score | Recommended |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohols | MeOH | 65 | 11 | 4 | 7 | 5 | Yes* |

| Alcohols | EtOH | 78 | 13 | 4 | 3 | 3 | Yes |

| Alcohols | n-BuOH | 118 | 29 | 3 | 4 | 3 | Yes |

| Ketones | Acetone | 56 | -18 | 5 | 3 | 5 | Yes* |

| Ketones | MEK | 80 | -6 | 5 | 3 | 3 | Yes |

| Esters | EtOAc | 77 | -4 | 5 | 3 | 3 | Yes |

| Esters | n-PrOAc | 102 | 14 | 4 | 2 | 3 | Yes |

| Water | Water | 100 | N/A | 1 | 1 | 1 | Yes |

*After discussion, despite "problematic" default ranking

Experimental Protocol: Systematic Solvent Evaluation and Substitution

Protocol 1: Solvent Selection for Reaction Optimization

Purpose: To systematically identify and evaluate solvents for a specific chemical reaction to maximize efficiency while minimizing environmental impact and PMI.

Materials and Equipment:

- ACS GCIPR Solvent Selection Tool (online platform) [12]

- CHEM21 Solvent Selection Guide (reference document) [30]

- Candidate solvents of appropriate purity grade

- Standard glassware and reaction apparatus

- Analytical equipment (HPLC, GC, NMR)

Procedure:

- Reaction Requirements Analysis: Define critical solvent properties required for the reaction, including polarity, boiling point range, hydrophilicity, and functional group compatibility [31].

Initial Solvent Identification: Using the ACS GCIPR Interactive Solvent Tool, identify a preliminary set of solvents with physical properties similar to traditional options but improved SHE profiles [12] [6].

Hazard Assessment: Screen identified solvents against the CHEM21 guide, prioritizing those classified as "recommended" [30]. Calculate SHE scores for any solvents not in the guide using the published methodology [30].

Experimental Validation:

- Prepare reaction mixtures in candidate solvents at laboratory scale (1-10 mmol scale)

- Monitor reaction progress and conversion using appropriate analytical methods

- Isolate and characterize products to determine yield and purity

- Assess solvent recovery potential through distillation or other separation techniques

PMI Calculation: For promising solvents, calculate Process Mass Intensity using the formula:

PMI = Total mass in process (kg) / Mass of product (kg) [6]

Include all solvent masses used in reaction, workup, and purification.

Final Selection: Choose the solvent that balances reaction performance with SHE considerations and lowest PMI.

Protocol 2: Solvent Swap Methodology

Purpose: To replace a hazardous or problematic solvent with a safer alternative between process steps while maintaining API stability and purity.

Materials and Equipment:

- Original process solvent (S1)

- Candidate swap solvents (S2)

- Batch distillation apparatus

- Solubility measurement equipment

- Analytical tracking methods (GC, HPLC)

Procedure:

- Swap Solvent Identification: Select candidate swap solvents using the CHEM21 guide and the following criteria [32]:

- Boiling point difference >20°C from original solvent

- No azeotrope formation with original solvent

- High average relative volatility

- Good API solubility (>10 mg/mL)

Phase Equilibrium Analysis: Confirm favorable vapor-liquid equilibrium (VLE) behavior between original and swap solvents [32].

Solubility Verification: Determine API solubility in pure swap solvent and mixtures with original solvent to prevent precipitation during exchange [32].

Swap Process Execution:

Option A: Put-Take Procedure:

- Reduce original solvent volume by 40-60% through distillation

- Add fresh swap solvent (20-30% of original volume)

- Repeat distillation and addition cycles until original solvent <5%

Option B: Constant Volume Procedure:

- Reduce original solvent to specific volume

- Continuously add swap solvent while maintaining constant volume through simultaneous distillation

- Continue until original solvent <5% [32]

Process Verification: Monitor original solvent concentration throughout process. Confirm API stability and final product quality meets specifications.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Key Resources for Solvent Selection and PMI Reduction

| Resource | Function | Application in PMI Reduction |

|---|---|---|

| ACS GCIPR Solvent Selection Tool | Interactive PCA-based solvent mapping | Identifies alternatives with similar properties but lower environmental impact [12] [6] |

| CHEM21 Selection Guide | Safety, Health, Environment solvent ranking | Systematically avoids hazardous solvents, reducing waste handling [30] [28] |

| PMI Prediction Calculator | Predicts mass efficiency of synthetic routes | Benchmarks and forecasts PMI during route scouting [6] [28] |

| Process Mass Intensity Calculator | Quantifies total mass input per product mass | Measures actual PMI for process optimization [28] |

| ICH Q3C Guidelines | Regulatory framework for residual solvents | Ensures compliance and patient safety [31] |

| Solvent Recovery Systems | Distillation and purification equipment | Enables solvent reuse, significantly reducing PMI [31] |

The ACS GCI Pharmaceutical Roundtable's solvent selection tools provide a science-based framework for making informed solvent choices that directly contribute to reduced Process Mass Intensity in pharmaceutical research and manufacturing. By systematically applying the CHEM21 Selection Guide and Interactive Solvent Tool, researchers can identify safer, more sustainable solvent alternatives while maintaining or improving reaction performance. The experimental protocols outlined enable practical implementation of these principles, supporting the pharmaceutical industry's transition toward greener manufacturing processes with lower environmental impact and improved sustainability metrics.

A Practical Guide to Bio-based and Green Solvent Alternatives (e.g., Ethyl Lactate, Dimethyl Carbonate)

The selection of solvents is a pivotal component in the design of sustainable chemical processes, directly influencing the Process Mass Intensity (PMI), a key metric endorsed by the ACS Green Chemistry Institute Pharmaceutical Roundtable (ACS GCI PR) for benchmarking process efficiency and environmental impact [33]. PMI, defined as the total mass of materials used in a process divided by the mass of the product, provides a comprehensive measure of resource efficiency, with lower values indicating greener processes [33]. Within the pharmaceutical industry, solvents can constitute up to 50% of the materials used in the manufacturing of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), making their rational selection a primary lever for improving sustainability [28].

This guide provides researchers and drug development professionals with practical application notes and protocols for integrating bio-based and green solvents, such as ethyl lactate and dimethyl carbonate, into their workflows. By transitioning from hazardous conventional solvents to safer, renewable alternatives, scientists can significantly reduce the environmental footprint of their syntheses and extractions while maintaining, and often enhancing, performance. The subsequent sections detail the properties of prominent green solvents, outline a practical framework for solvent selection, and provide experimentally validated protocols to facilitate immediate adoption.

Green Solvent Profiles and Properties

A new generation of solvents derived from renewable resources or possessing superior environmental, health, and safety (EHS) profiles is now available. The table below summarizes the key properties and applications of several well-established and emerging green solvents.

Table 1: Properties and Applications of Select Green Solvents

| Solvent Name | Source/Basis of 'Greenness' | Key Properties | Example Applications | PMI & Sustainability Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethyl Lactate [34] [35] | Bio-based, derived from lactic acid. | Biodegradable, low toxicity, high boiling point. | Reaction medium, extraction solvent for natural products. | Reduces waste (lower E-factor); renewable feedstock. |

| Dimethyl Carbonate (DMC) [36] [37] | Eco-friendly synthetic production. | Low toxicity, biodegradable, versatile reactivity (methylating agent). | Polycarbonate synthesis, battery electrolytes, solvent for pesticide residue analysis. | Non-halogenated, safer alternative to phosgene and methyl halides. |

| Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents (NaDES) [38] | Composed of natural primary metabolites (e.g., choline chloride, sugars). | Tunable properties, low volatility, high solubilizing power for a wide range of compounds. | Pharmaceutical synthesis, extraction, formulation, and as active ingredients (TheDES). | Biocompatible, can be prepared from abundant, renewable materials with low energy input. |

A Practical Framework for Green Solvent Selection

Integrating green solvents into research and development requires a systematic approach that balances sustainability with technical performance. The following workflow provides a step-by-step guide for this selection process, specifically aligned with the goal of reducing PMI.

Figure 1: A workflow for selecting green solvents to reduce Process Mass Intensity (PMI).

Consult Established Selection Guides: Begin with industry-standard tools like the ACS GCI Solvent Selection Tool and the CHEM21 Solvent Selection Guide [28]. These guides rate solvents based on comprehensive health, safety, and environmental (HSE) criteria, providing a validated starting point for identifying greener alternatives.

Assess EHS and PMI Impact: Evaluate the full lifecycle impact of candidate solvents. Use simple green metrics like Process Mass Intensity (PMI) to quantify material efficiency. The ACS GCI PR provides a PMI calculator to facilitate this evaluation [28] [33]. Lower PMI directly correlates with reduced waste and lower environmental impact.

Evaluate Technical Performance: Screen solvents for technical suitability. Use tools like the Hansen Solubility Parameters to predict solvation behavior [22]. For reaction media, confirm the solvent's inertness or desired reactivity (e.g., DMC as a methylating agent) [36].

Lab-Scale Experimental Screening: Conduct small-scale experiments to validate the performance of the top candidate solvents. Key performance indicators (KPIs) include reaction yield, product purity, extraction efficiency, and ease of product isolation.

Process Optimization: Once a promising solvent is identified, optimize the entire process (e.g., catalyst loading, temperature, work-up procedure) to minimize the total mass of all inputs, thereby achieving the lowest possible PMI [33].

Scale-Up Validation: Validate the optimized process at pilot or manufacturing scale, confirming that the environmental and economic benefits are realized at the operational level.

Detailed Application Notes and Protocols

Protocol 1: Supercritical Fluid Extraction using Dimethyl Carbonate as a Green Modifier

This protocol outlines a method for extracting pesticide residues from apple samples, using dimethyl carbonate (DMC) as a sustainable alternative to traditional solvents like acetonitrile [37].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for SFE with DMC

| Item | Function/Description | Green Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Dimethyl Carbonate (DMC) | Organic co-solvent to modify polarity of supercritical CO₂. | Low toxicity, biodegradable; replaces hazardous acetonitrile [37]. |

| Supercritical CO₂ | Primary extraction fluid. | Non-toxic, non-flammable, and readily recyclable. |

| Apple Sample | Matrix for pesticide residue analysis. | N/A |

Experimental Workflow:

Figure 2: Workflow for supercritical fluid extraction using DMC.

- Sample Preparation: Homogenize a representative apple sample.

- Equipment Setup: Load the homogenized sample into the supercritical fluid extraction vessel.

- Parameter Setting: Set the extraction parameters as follows:

- Co-solvent (DMC) proportion: 30%

- Pressure: 150 bar

- Temperature: 70 °C

- CO₂ flow rate: 1 mL/min

- Extraction: Perform the dynamic extraction for a total time of 21 minutes.

- Collection: Collect the resulting extract in a suitable vial.

- Analysis: Analyze the extract for pesticide residues using gas or liquid chromatography.

Key Findings: This method achieved an average extraction yield of 85% for a panel of 64 pesticides, demonstrating performance comparable to or better than acetonitrile. A significant additional benefit was the production of cleaner extracts, reducing co-extraction of matrix components and simplifying subsequent analysis [37].

Protocol 2: Employing Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents (NaDES) in Pharmaceutical Applications

NaDES, composed of natural compounds like choline chloride and sugars, are versatile solvents for synthesis, extraction, and formulation [38].

Experimental Workflow for a General NaDES-Mediated Synthesis:

Figure 3: General workflow for running a chemical reaction in a NaDES.

- NaDES Preparation: Combine the hydrogen bond donor (e.g., urea) and hydrogen bond acceptor (e.g., choline chloride) at the desired molar ratio (e.g., 1:2) in a round-bottom flask. Heat the mixture at approximately 80 °C with stirring until a clear, homogeneous liquid forms [38].

- Reaction Execution: Add the substrates and any catalysts directly to the prepared NaDES. Stir the reaction mixture at the target temperature for the required time.

- Work-up and Isolation: Upon reaction completion, add water to the mixture to partition the product. Extract the product with a benign organic solvent (e.g., ethyl acetate). The NaDES, being water-soluble, will remain in the aqueous phase.

- Solvent Recycling: The aqueous NaDES solution can often be recycled by removing the water under reduced pressure and reusing the reconstituted NaDES for subsequent reactions [38].

- Green Metrics Calculation: Calculate the Process Mass Intensity (PMI), Atom Economy (AE), and Reaction Mass Efficiency (RME) to quantitatively compare the sustainability of the NaDES-based process against conventional methods [38].

Table 3: Key Research Tools for Green Solvent Implementation

| Tool Name | Developer | Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solvent Selection Guide [28] | ACS GCI Pharmaceutical Roundtable (CHEM21) | Rates solvents based on health, safety, and environmental (HSE) criteria. | Publicly available online. |

| PMI Calculator [28] | ACS GCI Pharmaceutical Roundtable | Calculates Process Mass Intensity to benchmark and quantify process efficiency. | Publicly available online. |

| Machine Learning for Green Solvents [22] | Academic Research | Predicts solvent "greenness" and identifies substitutes from a large database (>10,000 solvents). | Emerging technology; some databases like GreenSolventDB are becoming public. |

| GreenSolventDB [22] | Academic Research (via ML) | Large database of green solvent metrics, aiding in the discovery of novel alternatives. | Publicly available database. |

The strategic adoption of bio-based and green solvents is a critical and achievable step toward more sustainable research and development in the chemical and pharmaceutical industries. By leveraging the practical frameworks, detailed protocols, and innovative tools outlined in this guide—from established solvents like ethyl lactate and dimethyl carbonate to emerging platforms like NaDES—scientists can make informed decisions that significantly reduce the Process Mass Intensity of their work. This transition not only aligns with the principles of green chemistry but also drives economic efficiency and fosters scientific innovation, ultimately contributing to a more sustainable future for chemical manufacturing.

Current environmental and health concerns are compelling a reassessment of the pharmaceutical industry, with the objective of minimising the environmental impact of drug production processes [38]. Identifying strategies that address multiple aspects of the production chain is therefore of significant interest. Within the context of developing a solvent selection guide for lower Process Mass Intensity (PMI), Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents (NaDES) present a promising solution. Composed of various biosourced metabolites, NaDES offer significant economic, health, and environmental benefits [39]. Their remarkable ability to interact with target compounds through non-covalent bonds enhances their versatility, allowing them to function as solvents, excipients, cofactors, catalysts, solubilisation promoters, stabilisers, and absorption agents [39] [38]. This application note explores the theory, preparation, and applications of NaDES, providing detailed protocols and data to facilitate their adoption in pharmaceutical research and development, ultimately contributing to more sustainable processes with reduced PMI.

Theoretical Foundation and Definition

What are NaDES?

In the context of phase behaviour, the term ‘eutectic’, derived from the Greek eutektos meaning ‘easy melting’, refers to a mixture with a melting point lower than that of any other composition of the same constituents [40] [38]. A Natural Deep Eutectic Solvent (NaDES) is a mixture of two or more natural, often biosourced, compounds (e.g., sugars, organic acids, amino acids, choline derivatives) that forms a eutectic liquid with a melting point significantly lower than that of an ideal liquid mixture [40] [41] [38]. The liquidus curve of a mixture can be derived using the Schröder–van Laar equation, and if the experimental eutectic point is at a lower temperature than the theoretical curve, the mixture is termed a Deep Eutectic Solvent (DES) [40] [38].

Key Definition: Martins et al. provide a rigorous description, defining a DES as “a mixture of two or more pure compounds where the eutectic point temperature is significantly lower than that of an ideal liquid mixture, exhibiting notable negative deviations from ideal (ΔT > 0)” [40] [38]. When a DES consists of natural compounds, it is termed a NaDES. A familiar example of a NaDES is honey, comprising glucose and fructose, which are individually solid at room temperature but form a viscous liquid when combined [40].

Molecular Interactions and Phase Behavior

The fundamental principle behind NaDES formation is the interaction through hydrogen bonding between a Hydrogen Bond Acceptor (HBA), such as choline chloride or betaine, and a Hydrogen Bond Donor (HBD), such as urea, glycerol, or organic acids [41] [42]. This interaction leads to charge delocalization between the HBA and HBD, which is responsible for the marked depression in the freezing point of the mixture, inhibiting crystallization and resulting in a stable liquid at room temperature [41]. The strength and number of these hydrogen bonds directly influence the solvent's properties, including its phase-transition temperature, stability, and solvating power [41].

The following phase diagram illustrates the typical behavior of a eutectic system, showing how the mixture's melting point drops to a minimum at the specific eutectic composition.

- Liquidus Line: The temperature above which the mixture is completely liquid.

- Solidus Line (Eutectic Invariant): The temperature below which the mixture is fully solid.

- Eutectic Point: The specific composition (ratio of A to B) with the lowest possible melting temperature, forming a homogeneous liquid [40] [38].

Preparation of NaDES: Detailed Experimental Protocols

NaDES can be prepared using several simple and green methods [41] [42]. The following protocols detail the most common and reliable techniques.

Heating and Stirring Method

This is the most frequently used and straightforward method for NaDES preparation [41].

- Procedure: