LSER Models for Solubility Determination: A Comprehensive Guide for Pharmaceutical Scientists

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of Linear Solvation Energy Relationship (LSER) models for determining solubility parameters, a critical task for researchers and drug development professionals.

LSER Models for Solubility Determination: A Comprehensive Guide for Pharmaceutical Scientists

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of Linear Solvation Energy Relationship (LSER) models for determining solubility parameters, a critical task for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational theory behind LSERs, including their molecular descriptors and thermodynamic basis. The content details practical methodologies for model application in pharmaceutical contexts, such as predicting drug solubility with macrocyclic hosts and excipient compatibility. It addresses common challenges and optimization strategies, including the integration of computational tools like COSMO-RS and data-driven machine learning. Finally, the article offers validation frameworks and comparative analyses with traditional approaches like Hansen Solubility Parameters, empowering scientists to reliably apply LSERs in drug formulation and material science.

Understanding LSER Fundamentals: From Solubility Parameters to Molecular Descriptors

The accurate prediction of solubility behavior is a cornerstone of research and development in fields ranging from polymer science to pharmaceutical development. The journey from the Hildebrand Solubility Parameter to the Hansen Solubility Parameters (HSP) represents a critical evolution in the application of Linear Solvation Energy Relationship (LSER) principles for quantifying molecular interactions. This progression from a one-dimensional to a three-dimensional model has transformed solubility from a qualitative concept of "like dissolves like" into a quantitative, predictive framework that accounts for the multiple facets of molecular cohesion. Within LSER research, solubility parameters serve as practical thermodynamic tools that bridge molecular structure with macroscopic solution behavior, enabling researchers to make informed predictions about phase equilibria, polymer dissolution, and formulation stability without exhaustive experimental trial and error.

Historical Development and Theoretical Foundations

The Hildebrand Solubility Parameter

In 1936, Joel H. Hildebrand introduced a groundbreaking concept for predicting the solubility of non-electrolytes, including polymer materials [1] [2]. He defined the solubility parameter (δ) as the square root of the cohesive energy density (CED), which represents the energy required to remove a molecule from its neighbors per unit volume.

The parameter is mathematically defined as:

δ = (ΔE_m / V_m)^(1/2) = ((ΔH_m - RT) / (M / ρ))^(1/2)

where ΔEm is the molar energy of vaporization, Vm is the molar volume, ΔH_m is the molar enthalpy of vaporization, R is the gas constant, T is the absolute temperature, M is the molar mass, and ρ is the density [1].

This one-dimensional parameter was revolutionary for its time, providing the first quantitative basis for the "like dissolves like" principle. It found particular utility for non-polar and slightly polar systems without hydrogen bonding [1]. The limitations of the Hildebrand parameter became apparent when applied to polar molecules and hydrogen-bonding systems, where it often failed to accurately predict solubility behavior [3] [4].

Table 1: Hildebrand Solubility Parameters (δ) of Selected Materials

| Substance | δ (cal¹⸍² cm⁻³⸍²) | δ (MPa¹⸍²) |

|---|---|---|

| n-Pentane | 7.0 | 14.4 |

| n-Hexane | 7.24 | 14.9 |

| Diethyl Ether | 7.62 | 15.4 |

| Acetone | 9.77 | 19.9 |

| Ethanol | 12.92 | 26.5 |

| Polyethylene | 7.9 | - |

| Polystyrene | 9.13 | - |

| Nylon 6,6 | 13.7 | 28 |

Hansen Solubility Parameters

Recognizing the limitations of the single-parameter approach, Charles M. Hansen introduced a three-dimensional solubility parameter system in his 1967 PhD thesis [5] [4]. Hansen proposed that the total cohesive energy density arises from three distinct intermolecular forces, leading to the now-familiar tripartite parameter system:

δ_t² = δ_d² + δ_p² + δ_h²

The three parameters are:

- δ_d (Dispersion parameter): Quantifies London dispersion forces arising from transient electron cloud fluctuations [5]

- δ_p (Polar parameter): Represents permanent dipole-dipole interactions (Keesom forces) [5]

- δ_h (Hydrogen bonding parameter): Captures hydrogen bond donor/acceptor capabilities [5]

This refinement allowed for a more nuanced application of LSER principles by separately accounting for different interaction mechanisms that contribute to overall solubility behavior.

The Hildebrand to Hansen Transition: A Conceptual Diagram

Quantitative Framework of Hansen Solubility Parameters

The Hansen Distance and Relative Energy Difference

The core predictive power of HSP lies in the concept of the Hansen distance (Rₐ), which quantifies the similarity between two materials in the three-dimensional Hansen space [5] [6]. The distance is calculated as:

Rₐ² = 4(δ_d2 - δ_d1)² + (δ_p2 - δ_p1)² + (δ_h2 - δ_h1)²

The factor of 4 applied to the dispersion term difference is an empirical correction that Hansen found necessary to balance the relative contributions of the different forces, reflecting that dispersion energy contributions are approximately twice as significant as polar or hydrogen bonding contributions in determining solubility [5].

The Relative Energy Difference (RED) provides a normalized measure of solubility potential:

RED = Rₐ / R₀

Where R₀ is the interaction radius of the solute material, determined experimentally [6]. The interpretation is straightforward:

- RED < 1.0: Solvent likely dissolves solute (good solvent)

- RED ≈ 1.0: Borderline solubility/swelling may occur

- RED > 1.0: Solvent unlikely to dissolve solute (poor solvent) [6]

Table 2: Hansen Solubility Parameters (in MPa¹⸍²) of Common Substances

| Substance | δ_d | δ_p | δ_h | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water | 15.5 | 16.0 | 42.3 | Reference polar solvent |

| Ethanol | 15.8 | 8.8 | 19.4 | Pharmaceutical formulations |

| Acetone | 15.5 | 10.4 | 7.0 | Common laboratory solvent |

| Diethyl Ether | 14.5 | 2.9 | 4.6 | Low polarity applications |

| Polystyrene | 18.6 | 6.0 | 4.5 | Polymer processing reference |

| PMMA | 17.7 | 9.1 | 7.1 | Biomedical applications |

| Nafion Backbone | 16.4 | 10.5 | 8.9 | Fuel cell research [6] |

| Nafion Side Chain | 15.2 | 11.7 | 15.9 | Fuel cell research [6] |

| Cellulose | 17.8 | 11.4 | 15.3 | Biomass processing [7] |

Comparative Performance: Hildebrand vs. Hansen

The superiority of the Hansen system is demonstrated by its ability to explain phenomena that confound the Hildebrand approach. A striking example involves epoxy dissolution [3]:

- n-Butanol and Nitroethane both have identical Hildebrand parameters (23 MPa¹⸍²) and neither dissolves a typical epoxy resin

- A 50:50 mixture of these "non-solvents" effectively dissolves the epoxy

- Hansen analysis reveals that while individually both solvents have high Rₐ values (>8), their mixture has a significantly lower Rₐ (3.9), falling within the solubility sphere of the epoxy

This phenomenon, where two non-solvents combine to form a good solvent, has been demonstrated for more than 60 solvent pairs across 22 different polymers [3].

Experimental Protocols for HSP Determination

Protocol: Determining HSP of an Unknown Polymer

Principle: The HSP values of an unknown polymer are determined by testing its solubility or swelling in a range of solvents with known HSP values, then defining a "solubility sphere" in Hansen space that contains the good solvents and excludes the poor solvents [5] [6].

Materials and Reagents:

- Polymer sample (purified, powdered when possible)

- 20-50 solvents spanning the Hansen space (see Table 3)

- Test tubes with airtight seals

- Analytical balance (±0.1 mg)

- Temperature-controlled incubation system

- Centrifuge (optional)

Table 3: Essential Solvents for HSP Determination

| Solvent | δ_d | δ_p | δ_h | Role in HSP Determination |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n-Hexane | 14.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | Defines dispersion axis extreme |

| Diethyl Ether | 14.5 | 2.9 | 4.6 | Low polarity reference |

| Chloroform | 17.8 | 3.1 | 5.7 | Moderate dispersion |

| Acetone | 15.5 | 10.4 | 7.0 | Defines polar region |

| Ethanol | 15.8 | 8.8 | 19.4 | Hydrogen-bonding reference |

| Methanol | 15.1 | 12.3 | 22.3 | Strong hydrogen-bonding |

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide | 18.4 | 16.4 | 10.2 | High polarity solvent |

| Water | 15.5 | 16.0 | 42.3 | Defines hydrogen-bonding extreme |

| Ethyl Acetate | 15.8 | 5.3 | 7.2 | Balanced properties |

| N-Methyl-2-pyrrolidone | 18.0 | 12.3 | 7.2 | Strong polymer solvent |

Procedure:

- Prepare 20-50 solutions of the polymer in selected solvents at a standard concentration (typically 1-5 mg/mL)

- Agitate mixtures continuously for 24 hours at constant temperature (typically 25°C)

- Centrifuge if necessary to separate undissolved material

- Assess solubility using:

- Visual inspection (transparency, cloudiness)

- Gravimetric analysis of dissolved fraction

- Light scattering for quantitative turbidity measurement

- Viscosity measurement for polymer solutions

- Classify solvents as "good" (complete dissolution), "partial" (swelling or partial dissolution), or "poor" (no interaction)

- Input results into HSP calculation software (e.g., HSPiP) or use graphical methods to determine the sphere center coordinates (δd, δp, δ_h) and radius (R₀) that best separate good from poor solvents

Validation: Test the predicted HSP values with additional solvents not included in the initial test set. The sphere should correctly predict solubility behavior with >90% accuracy for well-behaved systems.

Protocol: Calculating HSP for Mixed Solvent Systems

Principle: The HSP of a solvent mixture can be approximated by the volume-weighted average of the component parameters [7]:

δ_mix = φ₁δ₁ + φ₂δ₂ + ... + φ_nδ_n

Where φᵢ is the volume fraction of component i.

Procedure:

- Determine the HSP values of individual solvent components from reference tables

- Calculate the volume fractions of each component in the mixture

- Compute weighted averages for each parameter:

δ_d(mix) = φ₁δ_d₁ + φ₂δ_d₂ + ... + φ_nδ_dnδ_p(mix) = φ₁δ_p₁ + φ₂δ_p₂ + ... + φ_nδ_pnδ_h(mix) = φ₁δ_h₁ + φ₂δ_h₂ + ... + φ_nδ_hn

- Use the calculated mixed HSP to determine Rₐ and RED values for target solutes

Application Example: This method enables rational design of solvent blends with desired environmental, health, and safety profiles while maintaining dissolution efficacy [5].

Research Toolkit for Solubility Parameter Studies

Essential Research Reagents and Instruments

Table 4: Research Toolkit for Solubility Parameter Determination

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| HSPiP Software | Calculates HSP from experimental data; predicts solubility | Industry standard with extensive solvent database [8] |

| Inverse Gas Chromatography (IGC) | Determines HSP of solids by measuring retention times of probe molecules | Provides high-accuracy data for polymers [6] |

| Group Contribution Methods | Estimates HSP from molecular structure | Useful preliminary screening without experiments [6] |

| Solvent Library | 20-50 solvents spanning Hansen space | Must include representatives from all HSP regions [5] |

| Automated Dispensing System | Precise solvent handling for high-throughput screening | Reduces experimental error in mixture preparation |

| Turbidimetry System | Quantitative solubility assessment | Objective measurement of dissolution endpoints |

| Swelling Measurement Apparatus | Quantifies polymer swelling in marginal solvents | Important for cross-linked polymers |

Applications in Pharmaceutical and Materials Research

Case Study: Predicting Polymer-Solvent Interactions

The application of HSP extends across multiple disciplines, with particularly significant impact in pharmaceutical development and advanced materials. A representative case involves the optimization of fuel cell catalyst inks containing Nafion ionomer [6]. Researchers calculated dual HSP values for Nafion, recognizing its amphiphilic structure with hydrophobic backbone (δd=16.4, δp=10.5, δh=8.9) and hydrophilic side chains (δd=15.2, δp=11.7, δh=15.9). This detailed understanding enabled rational solvent selection to optimize ionomer dispersion state, which directly impacts catalyst layer structure and fuel cell performance.

Case Study: Natural Product Extraction Optimization

In natural product extraction, HSP has revolutionized solvent selection for compounds like cellulose [7]. Researchers determined that effective cellulose solvents must match its HSP profile (δd=17.8, δp=11.4, δ_h=15.3), leading to the identification of novel solvent systems including ionic liquids and deep eutectic solvents (DES). This approach has significantly reduced the traditional trial-and-error in identifying efficient, environmentally benign cellulose solvents for biomass processing.

Experimental Workflow for HSP Applications

The historical evolution from Hildebrand to Hansen Solubility Parameters represents a paradigm shift in how researchers approach solubility challenges. While Hildebrand's pioneering work established the fundamental connection between cohesive energy and solubility, Hansen's three-dimensional framework provided the necessary sophistication to address real-world systems with diverse molecular interactions. In the context of LSER model development, HSP serves as a practical implementation that successfully correlates molecular structure with macroscopic solution behavior. For today's drug development professionals and materials researchers, HSP provides a powerful predictive toolbox that reduces reliance on empirical approaches and enables rational design of formulations, extractions, and processing conditions across the chemical sciences.

Core Principles of Linear Solvation Energy Relationships (LSER)

Linear Solvation Energy Relationships (LSER) represent a powerful quantitative approach for predicting and interpreting the partitioning behavior of solutes in different chemical environments. Originally developed by Abraham, the LSER model provides a mechanistic framework for understanding how molecular interactions influence solvation properties across various phases [9] [10]. This methodology has found extensive applications in environmental chemistry, pharmaceutical sciences, and chemical engineering, particularly for predicting solubility, partition coefficients, and retention in chromatographic systems [11] [10].

The core LSER model expresses a free energy-related property as a linear combination of solute descriptors that encode specific molecular interaction capabilities. For solubility parameter determination research, LSERs offer a systematic approach to deconvoluting the relative contributions of different intermolecular forces that collectively define solubility behavior [9]. This molecular-level understanding enables researchers to make predictive assessments of solute behavior without extensive experimental measurements, streamlining the drug development process.

The LSER Equation and Molecular Descriptors

Fundamental LSER Equations

The Abraham LSER model employs two primary equations for different phase transfer processes. For solute transfer between two condensed phases, the model utilizes:

log(P) = cp + epE + spS + apA + bpB + vpVx [9]

Where P represents the partition coefficient between two condensed phases (e.g., water-to-organic solvent or alkane-to-polar organic solvent). For gas-to-solvent partitioning, the equation becomes:

log(KS) = ck + ekE + skS + akA + bkB + lkL [9]

Here, KS is the gas-to-organic solvent partition coefficient. In both equations, the capital letters (E, S, A, B, V, L) represent solute-specific molecular descriptors, while the lowercase coefficients (e, s, a, b, v, l) are system-specific parameters determined by regression analysis of experimental data [9] [10].

Solute Molecular Descriptors

Table 1: LSER Solute Molecular Descriptors and Their Chemical Significance

| Descriptor | Chemical Interpretation | Molecular Property Represented |

|---|---|---|

| Vx | McGowan's characteristic volume | Molecular size/cavity formation energy |

| L | Gas-hexadecane partition coefficient at 298 K | Overall dispersion interactions |

| E | Excess molar refraction | Polarizability from π- and n-electrons |

| S | Dipolarity/polarizability | Dipole-dipole and dipole-induced dipole interactions |

| A | Hydrogen bond acidity | Solute's hydrogen bond donating ability |

| B | Hydrogen bond basicity | Solute's hydrogen bond accepting ability |

These solute descriptors are considered intrinsic molecular properties that remain constant across different systems [9] [10]. The E descriptor encodes information about a solute's polarizability, particularly from π- and n-electrons, while the S descriptor represents the solute's ability to engage in dipole-type interactions [10]. The hydrogen bonding descriptors A and B quantify the solute's hydrogen bond donating and accepting capacities, respectively [9]. The Vx and L descriptors both relate to molecular size but capture different aspects of dispersion interactions and cavity formation energy [9].

System Coefficients and Their Interpretation

Table 2: LSER System Coefficients and Their Physicochemical Meaning

| Coefficient | Complementary Property | Chemical Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| v | Solvent cohesion | Endoergic cavity formation energy in solvent |

| l | Solvent dispersion | Solvent's capacity for dispersion interactions |

| e | Solvent polarizability | Solvent's ability to interact with solute π/n-electrons |

| s | Solvent dipolarity | Solvent's dipole-dipole interaction capability |

| a | Solvent basicity | Solvent's hydrogen bond accepting ability |

| b | Solvent acidity | Solvent's hydrogen bond donating ability |

The system coefficients (lowercase letters) are determined through multiple linear regression analysis of experimental data for a variety of solutes with known descriptors [9] [10]. These coefficients represent the complementary effect of the solvent phase on solute-solvent interactions and contain specific chemical information about the solvent system [9]. The a and b coefficients are particularly important for understanding hydrogen-bonding interactions in solubility parameter determination, as they reflect the solvent's hydrogen bond accepting and donating capacities, respectively [9].

Experimental Protocols for LSER Applications

Protocol 1: Determining Solute Descriptors

Principle: This protocol outlines the experimental and computational methods for determining the six Abraham solute descriptors (E, S, A, B, V, L) for new chemical compounds.

Materials and Reagents:

- High-purity solvents (n-hexane, n-hexadecane, water, octanol)

- Gas chromatograph with flame ionization detector

- HPLC system with appropriate columns

- Partition coefficient measurement apparatus

- Computational chemistry software (for preliminary estimates)

Procedure:

- Determine McGowan's Characteristic Volume (Vx): Calculate using molecular structure and atomic contributions according to the method described by McGowan.

Measure Gas-Hexadecane Partition Coefficient (L):

- Determine the gas-to-n-hexadecane partition coefficient at 298 K using inverse gas chromatography [9].

- Use n-hexadecane as the stationary phase and measure retention times for the solute.

- Calculate L from the retention data using standard thermodynamic relationships.

Determine Excess Molar Refraction (E):

- Measure the solute's refractive index at 293 K using a refractometer.

- Calculate E using the established relationship between refractive index and electron polarizability [10].

Measure Hydrogen Bond Acidity and Basicity (A and B):

Determine Dipolarity/Polarizability (S):

- Calculate S from the determined L, E, A, B, and V values and measured partition coefficients using the LSER equation.

- Alternatively, use computational approaches to estimate S based on molecular structure.

Validate Descriptors:

- Confirm the determined descriptors by predicting partition coefficients in additional solvent systems not used in the determination.

- Compare predicted versus experimental values to ensure consistency.

Troubleshooting Tips:

- If inconsistent results are obtained, verify the purity of all solvents and compounds.

- Ensure all measurements are conducted at constant temperature (298 K).

- For compounds with limited solubility, consider using more sensitive analytical techniques.

Protocol 2: Applying LSER for Solubility Prediction

Principle: This protocol describes how to use established LSER equations and parameters to predict solute partitioning and solubility in pharmaceutical development contexts.

Materials and Reagents:

- Database of solute descriptors (e.g., Abraham LSER database)

- System coefficients for target solvents/phases

- Computational resources for calculations

- Validation standards with known partition behavior

Procedure:

- Define the System:

- Identify the specific phase transfer or partition process of interest (e.g., water-to-membrane, blood-to-tissue).

- Select the appropriate LSER equation based on the system [9].

Compile Solute Descriptors:

- Obtain the six Abraham descriptors (E, S, A, B, V, L) for the target solute from experimental measurements or reliable databases.

- For new compounds, use group contribution methods to estimate descriptors [11].

Identify System Coefficients:

- Obtain the system-specific coefficients (e, s, a, b, v, l) for the target solvent system from literature or previous determinations.

- Ensure the coefficients were determined using the same LSER form and descriptor scales.

Calculate the Free Energy-Related Property:

- Substitute the solute descriptors and system coefficients into the appropriate LSER equation.

- Calculate the predicted partition coefficient or related property.

Convert to Solubility Parameters (if needed):

- Use the relationship between partition coefficients and activity coefficients.

- Calculate the activity coefficient at infinite dilution from the partition coefficient.

- Relate to solubility parameters using established thermodynamic relationships.

Validate the Prediction:

- Compare predictions with experimental data for similar compounds.

- Assess the chemical reasonableness of the prediction based on molecular structure.

Troubleshooting Tips:

- If predictions seem inaccurate, verify the applicability domain of the system coefficients.

- Check for potential specific interactions not adequately captured by the LSER model.

- Consider using multiple LSER equations for the same prediction to assess consistency.

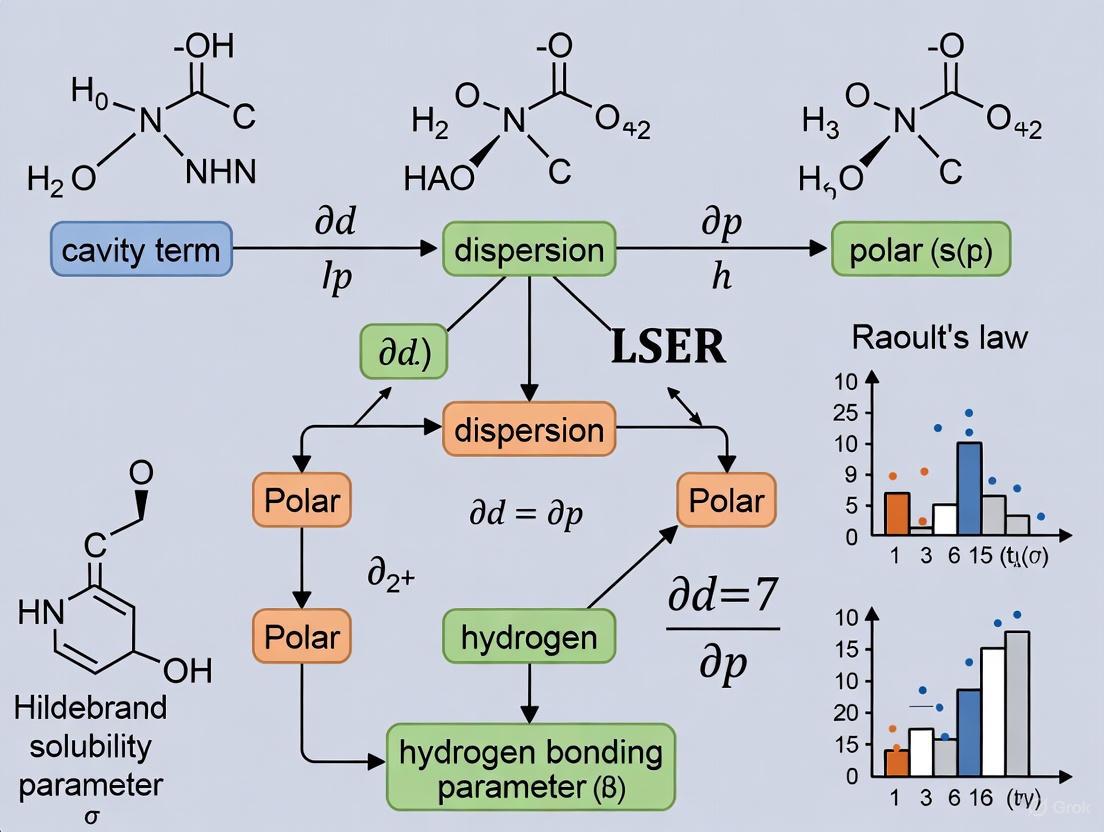

LSER Workflow and Relationship Mapping

LSER Application Workflow for Solubility Determination

Molecular Interactions in LSER Framework

Molecular Interactions Captured by LSER Model

Research Reagent Solutions for LSER Studies

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for LSER Experimental Determination

| Reagent/Material | Function in LSER Studies | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| n-Hexadecane | Reference solvent for determining L descriptor | Gas-liquid partition measurements |

| Water (HPLC Grade) | Reference polar solvent for partition studies | Determination of A and B descriptors |

| 1-Octanol | Model biological membrane solvent | Pharmaceutical partitioning studies |

| Inert Gas Chromatography Phases | Stationary phases for inverse GC | Measurement of gas-liquid partitions |

| Reference Compounds | Calibration standards with known descriptors | Method validation and standardization |

| Filter Papers/Substrates | Support media for liquid samples | Sample presentation for analysis |

Advanced Applications in Drug Development

The LSER approach provides exceptional utility in pharmaceutical research by enabling quantitative prediction of solute distribution across biological barriers. For drug development professionals, LSER models can predict blood-brain barrier penetration, gastrointestinal absorption, and skin permeability based on molecular descriptors [9]. The model's ability to deconvolute the specific interactions governing solute partitioning allows medicinal chemists to rationally modify molecular structures to optimize distribution properties.

Recent advances have integrated LSER with equation-of-state thermodynamics through Partial Solvation Parameters (PSP), enhancing the extraction of thermodynamic information from LSER databases [9]. This integration allows researchers to estimate free energy changes upon hydrogen bond formation (ΔGhb), as well as corresponding enthalpy (ΔHhb) and entropy (ΔShb) contributions, providing deeper insight into the molecular interactions governing solubility behavior [9].

For solubility parameter determination research, LSER offers a pathway to quantify the relative contributions of different solubility parameter components (dispersion, polar, hydrogen bonding) from experimental partition data. This molecular-level understanding of interaction strengths facilitates more accurate predictions of solubility in complex pharmaceutical systems and supports the rational design of drug molecules with optimized solubility profiles.

Decoding the Six Key LSER Molecular Descriptors (Vx, E, S, A, B, L)

The Linear Solvation Energy Relationship (LSER) model, also known as the Abraham model, is a cornerstone predictive tool in environmental chemistry, pharmaceutical sciences, and chemical engineering for estimating solute partitioning and solubility parameters [9] [12]. This model's power lies in its ability to correlate a solute's free-energy-related properties with six fundamental molecular descriptors, providing a quantitative framework for understanding intermolecular interactions [9]. Within broader research on solubility parameter determination, LSER serves as a critical bridge between molecular structure and macroscopic thermodynamic behavior, enabling researchers to predict environmental fate, bioavailability, and physicochemical properties without extensive laboratory experimentation [13] [12]. The model operates through two primary linear equations that quantify solute transfer between phases, with the general form for transfer between condensed phases expressed as log(P) = cp + epE + spS + apA + bpB + vpVx, and for gas-to-solvent partitioning as log(KS) = ck + ekE + skS + akA + bkB + lkL [9].

The Six Key Molecular Descriptors

The LSER model characterizes solutes using six descriptors, each capturing a distinct aspect of molecular interaction potential. The following table summarizes these core descriptors and their physicochemical significance.

Table 1: The Six Key LSER Molecular Descriptors and Their Interpretations

| Descriptor | Full Name | Molecular Property Represented | Interaction Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vx | McGowan's Characteristic Volume | Molecular size and volume [12] | Dispersion (van der Waals) interactions [9] |

| E | Excess Molar Refraction | Polarizability from π- and n-electrons [13] [12] | Dispersion interactions [9] |

| S | Dipolarity/Polarizability | Overall polarity and ability to stabilize a charge [12] | Dipole-dipole and dipole-induced dipole interactions [9] |

| A | Solute H-Bond Acidity | Ability to donate a hydrogen bond [12] | Specific hydrogen-bonding (acid-base) interactions [9] |

| B | Solute H-Bond Basicity | Ability to accept a hydrogen bond [12] | Specific hydrogen-bonding (acid-base) interactions [9] |

| L | Logarithm of Hexadecane-Air Partition Coefficient | General dispersion and polar interactions [13] | Various intermolecular interactions [9] |

Detailed Descriptor Analysis

Vx (McGowan's Characteristic Volume): This descriptor quantifies the molecular volume and is directly related to the energy cost of forming a cavity in the solvent to accommodate the solute. Larger Vx values typically lead to greater partitioning into organic phases due to enhanced dispersion interactions [12].

E (Excess Molar Refraction): E reflects the solute's polarizability, particularly from π-electrons and non-bonding orbitals. It is derived from refractive index data and indicates a molecule's ability to participate in non-specific polarization interactions. Aromatic compounds and molecules with conjugated systems typically exhibit higher E values [13] [12].

S (Dipolarity/Polarizability): This descriptor represents the solute's ability to engage in dipole-dipole and dipole-induced dipole interactions. It encompasses both the permanent dipole moment and the molecular polarizability, playing a crucial role in partitioning into polar solvents [12].

A and B (Hydrogen-Bonding Parameters): These complementary descriptors quantify the solute's hydrogen-bonding capacity. A (H-Bond Acidity) measures the solute's ability to donate a proton (hydrogen bond donor strength), while B (H-Bond Basicity) measures its ability to accept a proton (hydrogen bond acceptor strength). These are among the most important descriptors for predicting solubility in aqueous and hydrogen-bonding environments [12].

L (Logarithm of Hexadecane-Air Partition Coefficient): Originally determined experimentally using n-hexadecane as a reference solvent, this descriptor encapsulates the solute's general affinity for condensed phases versus the gas phase. It reflects the overall combination of dispersion and polar interactions [13].

Experimental Protocols for Descriptor Determination

Traditional Experimental Determination

The following workflow outlines the multi-step process for empirically determining LSER molecular descriptors through laboratory measurements.

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for determining LSER descriptors.

Protocol 1: Experimental Determination of LSER Descriptors

Principle: Each descriptor is determined by measuring partition coefficients in multiple well-characterized solvent systems with known LSER coefficients, then solving the resulting system of equations [9].

Materials:

- Analytical balance (±0.0001 g precision)

- HPLC system with UV/RI detectors

- Gas chromatograph with FID detector

- Thermostated water baths (±0.1°C)

- n-Hexadecane, n-octanol, and other reference solvents of HPLC grade

- Hermetically sealed vials for partitioning experiments

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Partition Coefficient Measurement:

- Prepare solute solutions at multiple concentrations in relevant phases (e.g., water, n-octanol, n-hexadecane, air).

- For liquid-liquid partitioning, equilibrate solute between n-octanol and water phases for 24 hours with constant shaking at 25°C.

- Separate phases by centrifugation at 3000 rpm for 15 minutes.

- Quantify solute concentration in each phase using HPLC or GC analysis.

- Calculate partition coefficient as P = Corganic/Cwater.

Data Collection Across Systems:

- Measure partition coefficients for at least 6-10 different solvent systems with known LSER coefficients [9].

- Include systems sensitive to different interaction types (e.g., hydrogen bonding, dispersion).

Multilinear Regression Analysis:

- Apply the general LSER equation: log(P) = c + eE + sS + aA + bB + vV_x

- Use matrix algebra to solve for the six unknown descriptors (E, S, A, B, V, L).

- Verify solution stability through statistical measures (e.g., correlation coefficients, residual analysis).

Validation:

- Test derived descriptor set by predicting partition coefficients in additional solvent systems not used in the regression.

- Compare predicted versus experimental values to assess descriptor accuracy.

In Silico Determination Protocol

Protocol 2: Computational Determination of LSER Descriptors

Principle: Molecular descriptors are calculated using quantum chemical methods and Quantitative Structure-Property Relationship (QSPR) models, eliminating the need for extensive laboratory measurements [13].

Materials:

- Quantum chemical software (e.g., Gaussian, ORCA, or other DFT packages)

- Computer with sufficient computational resources (multi-core processor, 16+ GB RAM)

- Molecular modeling and visualization software

- LSER database for QSPR model development [12]

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Molecular Geometry Optimization:

- Build initial molecular structure using chemical drawing software or coordinate generation.

- Perform geometry optimization using Density Functional Theory (DFT) with appropriate basis sets (e.g., B3LYP/6-311G).

- Verify optimization convergence and confirm structure corresponds to energy minimum through frequency calculation.

Electronic Property Calculation:

- Compute molecular electrostatic potential surfaces and electron density distributions.

- Calculate molecular volume using COSMO-RS or similar continuum solvation models [12].

- Derive polarizability parameters from frequency calculations.

Descriptor Calculation:

- Calculate excess molar refraction (E) from computed polarizabilities [13].

- Determine McGowan's characteristic volume (V_x) from the optimized molecular structure [12].

- Compute hexadecane/air partition coefficient (L) using DFT-calculated properties [13].

- Predict dipolarity/polarizability (S), solute H-bond acidity (A), and basicity (B) parameters using validated QSPR models developed with theoretical molecular descriptors [13].

Validation of Computational Approach:

- Compare computationally derived descriptors with available experimental values for reference compounds.

- Assess predictive capability by constructing new LSER models for physicochemical properties and comparing performance with conventional LSER models [13].

Application in Solubility Parameter Determination

The relationship between LSER descriptors and solubility parameters provides powerful insights for pharmaceutical and environmental applications. The following diagram illustrates how molecular descriptors inform Hansen solubility parameters.

Figure 2: From LSER descriptors to solubility parameters and applications.

Protocol 3: Estimating Solubility Parameters from LSER Descriptors

Principle: LSER descriptors can be correlated with Hansen solubility parameters (δd, δp, δh) through mathematical relationships derived from solvation thermodynamics [9].

Materials:

- Set of LSER descriptors for target compound (experimentally or computationally derived)

- Mathematical software (Python, R, or MATLAB)

- Reference database of solubility parameters for validation

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Establish Descriptor-Solubility Parameter Correlations:

- Collect LSER descriptors and experimental solubility parameters for reference compounds.

- Develop correlation equations using multilinear regression:

- δd = f(V_x, E, L)

- δp = f(S)

- δh = f(A, B)

Calculate Partial Solvation Parameters (PSP):

Convert PSP to Solubility Parameters:

- Transform PSP values to Hansen solubility parameters using established conversion factors.

- Validate calculated solubility parameters against experimental data when available.

Application to Solvent Selection:

- Use calculated solubility parameters to predict compatibility with potential solvents.

- Apply Hansen solubility sphere concept to identify optimal solvent systems for extraction, crystallization, or formulation.

Advanced Computational Integration

Recent advances have enabled more sophisticated integration of LSER with computational thermodynamics:

Quantum Chemical LSER (QC-LSER):

- New molecular descriptors derived from molecular surface charge distributions obtained from COSMO-type quantum chemical calculations [12].

- Thermodynamically consistent reformulation of LSER models allowing more accurate prediction of hydrogen-bonding free energies, enthalpies, and entropies [12].

- Ability to account for conformational changes during solvation through detailed quantum mechanical calculations [12].

Equation-of-State Integration:

- LSER descriptors inform equation-of-state models like SAFT and NRHB through Partial Solvation Parameters [9].

- Enables prediction of activity coefficients at infinite dilution (γ∞) through the relationship: ΔG12/RT = ln(φ10P10Vm2γ∞1/2/RT) [12].

- Enables extension of LSER predictions to varied temperature and pressure conditions beyond standard states [9].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Resources for LSER Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function in LSER Research |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Solvents | n-Hexadecane, n-Octanol, Water, Diethyl Ether, Chloroform, Ethyl Acetate | Provide standardized systems for experimental determination of partition coefficients and descriptor validation [9]. |

| Analytical Instruments | HPLC-UV, GC-FID, Headspace Samplers, Spectrophotometers | Precisely quantify solute concentrations in multiphase systems for partition coefficient measurement. |

| Computational Software | Gaussian, ORCA, COSMO-RS, OpenQSAR | Perform quantum chemical calculations, derive molecular descriptors, and build predictive models [12]. |

| LSER Databases | Abraham LSER Database, UFZ-LSER Database | Provide curated experimental descriptor values for model development and validation [12]. |

| QSPR Tools | DRAGON, PaDEL-Descriptor, RDKit | Calculate molecular descriptors for in silico LSER parameter estimation [13]. |

The Thermodynamic Basis of LSER Linearity and Solute-Solvent Interactions

The Linear Solvation Energy Relationship (LSER) model, particularly in the form of the Abraham solvation parameter model, stands as one of the most successful predictive tools for understanding a broad variety of chemical, biomedical, and environmental processes [9]. The model is celebrated for its ability to correlate and predict free-energy-related properties of solutes based on a set of molecular descriptors. Its robustness stems from a sound thermodynamic basis and the wise selection of molecular descriptors that comprehensively characterize each solute molecule [14]. The wealth of thermodynamic information contained within the freely accessible LSER database is of immense value for applications ranging from solvent screening in pharmaceutical development to predicting environmental fate of chemicals [9].

The core of the LSER model lies in its linear free energy relationships (LFER), which quantify the transfer of a solute between two phases. The remarkable feature of these relationships is their observed linearity, even for strong, specific interactions like hydrogen bonding. This application note delves into the thermodynamic basis of this linearity, provides protocols for its practical application, and illustrates how it can be integrated with modern computational and experimental approaches for solubility parameter determination within a research thesis framework [9] [14].

Theoretical Foundation: Thermodynamic Basis of LSER Linearity

The LSER Equations and Molecular Descriptors

The LSER model utilizes two primary equations to quantify solute transfer. The first describes partitioning between two condensed phases [9] [14]: log (P) = cp + epE + spS + apA + bpB + vpVx [9]

The second equation describes gas-to-condensed phase partitioning [9] [14]: log (KS) = ck + ekE + skS + akA + bkB + lkL [9]

In these equations, the upper-case letters represent solute-specific molecular descriptors, while the lower-case letters are the complementary system- or solvent-specific coefficients obtained through multilinear regression of experimental data [9] [14].

Table 1: LSER Solute Molecular Descriptors and Their Physico-Chemical Interpretation

| Descriptor | Symbol | Physico-Chemical Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| McGowan's Characteristic Volume | Vx | Related to the size of the solute molecule and the energy required to form a cavity in the solvent [14]. |

| Gas-Hexadecane Partition Coefficient | L | Describes the solute's ability to participate in dispersive van der Waals interactions [9] [14]. |

| Excess Molar Refraction | E | Measures the solute's polarizability due to π- and n-electrons [10]. |

| Dipolarity/Polarizability | S | Reflects the solute's ability to engage in dipole-dipole and dipole-induced dipole interactions [10]. |

| Hydrogen Bond Acidity | A | Quantifies the solute's ability to donate a hydrogen bond [10] [14]. |

| Hydrogen Bond Basicity | B | Quantifies the solute's ability to accept a hydrogen bond [10] [14]. |

Provenance of Linearity in LSER Models

The linearity observed in LSER equations, even for specific interactions like hydrogen bonding, has a firm grounding in solution thermodynamics. The process of solvation or partitioning can be conceptually broken down into two primary steps [10]:

- An endoergic process involving cavity formation within the solvent and solvent reorganization.

- An exoergic process driven by attractive solute-solvent interactions.

The LSER model successfully parameterizes the Gibbs free energy change of this overall process. The product terms in the LSER equations (e.g., aA, bB) represent the contributions of specific intermolecular interactions to the total free energy. The linearity holds because, for a given phase transfer process and within a congeneric set of solutes, the free energy contribution from each type of interaction is approximately additive [9].

Research combining equation-of-state solvation thermodynamics with the statistical thermodynamics of hydrogen bonding has verified the thermodynamic basis of LFER linearity. It has been shown that the model effectively captures the balance between the different interaction energies and entropic contributions, justifying the simple linear form of the relationships [9]. The coefficients (e.g., a and b) are system descriptors that reflect the solvent's complementary ability to participate in that specific interaction (e.g., basicity and acidity, respectively) [9] [14].

Experimental Protocols for LSER and Solubility Determination

Protocol 1: Determining Solute LSER Molecular Descriptors

Principle: This protocol outlines the standard procedure for obtaining the six Abraham LSER descriptors (E, S, A, B, V, L) for a new solute molecule. These descriptors are foundational for any subsequent LSER analysis.

Materials:

- Solute of interest (high purity)

- Solvents: n-Hexadecane, water, and other well-characterized solvents from the LSER database

- Gas Chromatograph (GC) equipped with a flame ionization detector (FID)

- High-Performance Liquid Chromatograph (HPLC) system with a UV/Vis detector

- Partitioning vessels (e.g., shake-flasks)

- Constant-temperature incubator shaker

- Analytical balance

Procedure:

- McGowan Volume (Vx): Calculate Vx using a group contribution method based on the molecular structure of the solute. This is a computational determination and does not require experimentation [14].

- Excess Molar Refraction (E): Determine the solute's refractive index experimentally and calculate E using the Lorentz-Lorenz equation. This value is indicative of the solute's polarizability [10].

- Gas-Hexadecane Partition Coefficient (L): a. Using gas chromatography, measure the retention time of the solute on a non-polar column (e.g., polydimethylsiloxane) with n-hexadecane as the stationary phase. b. Relate the retention time to the partition coefficient L at 298 K using known standards [9] [14].

- Hydrogen Bond Acidity (A) and Basicity (B): a. Measure the solute's partition coefficient in several well-characterized solvent/water or solvent/gas systems (e.g., octanol-water, ether-water) using the shake-flask method. b. In a sealed vessel, dissolve a known amount of solute in a mixture of two immiscible solvents (e.g., water and octanol). c. Agree vigorously in a constant-temperature incubator shaker (e.g., 25°C) for 24-48 hours to reach equilibrium. d. Allow phases to separate, then sample each phase and quantify the solute concentration using HPLC-UV/Vis. e. The partition coefficient is the ratio of concentrations in the two phases.

- Dipolarity/Polarizability (S): This descriptor is typically determined indirectly by multilinear regression analysis of the partition coefficient data obtained in step 4, along with the other known descriptors (E, Vx, A, B, L).

Data Analysis: The final set of descriptors is obtained by fitting a large set of experimentally determined partition coefficients (log P) across multiple solvent systems to the LSER equation. The values are refined iteratively until a consistent set of six descriptors is obtained that best predicts all the experimental data. These descriptors can then be added to the LSER database for future use [9] [10].

Protocol 2: Measuring Solubility for Hansen Parameter Determination

Principle: The static gravimetric (shake-flask) method is a reliable technique for determining equilibrium solubility, which is crucial for calibrating and validating solubility parameters, such as Hansen Solubility Parameters (HSP) [15] [16].

Materials:

- Solute of interest (e.g., a drug molecule like Naproxen or 17-α hydroxyprogesterone)

- Pure solvents and solvent mixtures of varying polarity and hydrogen-bonding capability (e.g., methanol, ethanol, acetone, ethyl acetate, water, DMF)

- Jacketed vessels connected to a thermostatted water bath

- Laboratory incubator-shaker

- Centrifuge

- UV/Vis Spectrophotometer or HPLC for concentration analysis

- Analytical balance (precision ± 0.1 mg)

- Micropipettes

Procedure:

- Preparation: Pre-saturate all solvents by adding a small excess of solute and agitating for several hours prior to the main experiment.

- Equilibration: a. Weigh an excess amount of solute into a series of jacketed vessels. b. Add a known mass of pre-saturated solvent to each vessel. c. Seal the vessels and maintain them at a constant temperature (e.g., 298.15 K) using a circulating water bath. d. Agitate the suspensions continuously using a magnetic stirrer or place them in an incubator-shaker for a sufficient period (typically 24-72 hours) to ensure solid-liquid equilibrium is reached.

- Sampling: a. After equilibration, stop agitation and allow the undissolved solute to settle. b. To prevent precipitation, maintain the sampling temperature. Withdraw an aliquot of the saturated supernatant. For suspensions that are slow to settle, use a pre-warmed centrifuge to separate the solid. c. Carefully filter the supernatant if necessary using a pre-warmed syringe filter.

- Analysis: a. Dilute the saturated solution as needed with a suitable solvent (e.g., 50% ethanol for UV analysis). b. Quantify the solute concentration using a pre-calibrated method: * UV/Vis Spectrophotometry: Measure absorbance at the solute's λmax and compare to a calibration curve [15] [16]. * HPLC: Use for higher specificity, especially in complex solvent mixtures [16].

- Repeat: Repeat the procedure at different temperatures to study the temperature dependence of solubility.

Data Analysis: The molar solubility is calculated from the concentration, molar mass, and density of the solution. The experimental solubility data in multiple solvents can be used to determine the Hansen Solubility Parameters (δD, δP, δH) of the solute by finding the center of the "solubility sphere" in three-dimensional parameter space [17] [18].

Data Presentation and Modeling

Quantitative Data from LSER and Solubility Studies

Table 2: Experimentally Determined Solubility (x₁) of 17-α Hydroxyprogesterone in Selected Pure Solvents at 298.15 K [15]

| Solvent | HSP δD (MPa¹/²) | HSP δP (MPa¹/²) | HSP δH (MPa¹/²) | Solubility x₁ (10³ mol·mol⁻¹) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methanol | 15.3 [18] | 12.4 [18] | 22.5 [18] | 1.210 |

| Ethanol | 16.1 [18] | 5.8 [18] | 15.9 [18] | 1.788 |

| Acetone | 15.7 [18] | 10.5 [18] | 7.0 [18] | Data not available in source |

| Ethyl Acetate | 16.1 [18] | 5.8 [18] | 5.2 [18] | Data not available in source |

| Tetrahydrofuran | 16.9 [18] | 5.8 [18] | 8.1 [18] | Data not available in source |

| N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF) | 18.6 [18] | 16.5 [18] | 10.3 [18] | 0.06548 (at 323.15 K) |

Table 3: Representative LSER System Coefficients (lf) for Gas-to-Solvent Partitioning (log Ks) [9] [14]

| System Coefficient | Chemical Interpretation | Example Value for a Polar Solvent |

|---|---|---|

| l | Resilience of the solvent to separate molecules and create a cavity for the solute. | Positive value |

| e | Solvent's ability to engage in polarization interactions with the solute. | Positive value |

| s | Solvent's complementary dipolarity/polarizability. | Positive value |

| a | Solvent's hydrogen-bond basicity (complementary to solute acidity A). | Positive value |

| b | Solvent's hydrogen-bond acidity (complementary to solute basicity B). | Positive value |

Thermodynamic Modeling of Solubility Data

Experimental solubility data can be correlated and interpreted using various thermodynamic models. The modified Apelblat model is widely used for its accuracy in describing the temperature dependence of solubility [15]: ln x = A + B/T + C ln T Where x is the mole fraction solubility, T is the absolute temperature, and A, B, C are empirical parameters.

Furthermore, the van't Hoff analysis allows for the calculation of thermodynamic dissolution parameters [15] [16]: ln x = - (ΔsolH° / R)(1/T) + (ΔsolS° / R) Where ΔsolH° is the standard dissolution enthalpy, ΔsolS° is the standard dissolution entropy, and R is the gas constant. A positive ΔsolH° indicates an endothermic dissolution process, which is common for many organic solutes in organic solvents [15].

Visualization of Concepts and Workflows

Diagram 1: Integrated research workflow for combining LSER and solubility parameter studies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for LSER and Solubility Studies

| Item / Solution | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| n-Hexadecane | Standard solvent for determining the gas-liquid partition coefficient (L) descriptor [9] [14]. |

| 1-Octanol / Water System | Benchmark biphasic system for measuring partition coefficients (log P) used to refine A, B, and S descriptors [10]. |

| Solvent Library | A diverse set of solvents covering a wide range of polarity, polarizability, and hydrogen-bonding characteristics (e.g., alkanes, ethers, ketones, alcohols, DMSO) for comprehensive solubility profiling and LSER coefficient determination [9] [15]. |

| Abraham LSER Database | A freely accessible, comprehensive database containing pre-determined LSER molecular descriptors for thousands of solutes and system coefficients for numerous solvents/phases. It is the primary resource for initial predictions and comparisons [9] [14]. |

| COSMO-RS / COSMOtherm | A quantum mechanics-based a priori predictive method for solvation thermodynamics. Used to predict solvation properties and can be interconnected with LSER to provide insights and estimates, especially for new molecules [9] [14]. |

| Machine Learning Libraries (e.g., for CatBoost, ANN) | Advanced data-driven frameworks used to develop predictive models for properties like solubility parameters, capturing complex, non-linear relationships from large datasets [19]. |

Linking LSER Descriptors to Partial Solvation Parameters (PSP)

Within the broader context of developing robust Linear Solvation Energy Relationship (LSER) models for solubility parameter determination, the Partial Solvation Parameter (PSP) approach emerges as a powerful, thermodynamically grounded framework. It effectively interconnects diverse Quantitative Structure-Property Relationship (QSPR)-type databases and molecular descriptors, facilitating a unified approach to predicting solvation phenomena [9] [20]. While traditional models like the Hansen Solubility Parameter (HSP) and Abraham's LSER have been widely used in pharmaceutics and material science, the PSP approach offers a distinct advantage by providing a coherent thermodynamic model for both bulk phases and interfaces, allowing for the direct calculation of free energy changes upon molecular interactions [21] [20]. This application note details the formalisms, protocols, and practical applications for linking established LSER molecular descriptors to the PSP framework, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a method to leverage existing LSER data for advanced thermodynamic modeling.

Theoretical Foundation and Definitions

The PSP framework deconstructs a molecule's solvation behavior into four complementary parameters, each mapping to specific intermolecular interactions quantified by LSER descriptors [20]. The core definitions establishing the one-to-one correspondence between LSER descriptors and PSPs are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Fundamental Relationships between LSER Descriptors and Partial Solvation Parameters

| Partial Solvation Parameter (PSP) | LSER Descriptor Mapping | Physical Interaction Represented |

|---|---|---|

| Dispersion PSP (σd) | σd = 100 * (3.1 * Vx + E) / Vm [20] |

Hydrophobicity, cavity effects, and dispersion/weak non-polar interactions. Maps McGowan volume (Vx) and excess refractivity (E). |

| Polarity PSP (σp) | σp = 100 * S / Vm [20] |

Dipolar interactions (Debye and Keesom types). Maps the dipolarity/polarizability descriptor (S). |

| Acidity PSP (σGa) | σGa = 100 * A / Vm [20] |

Hydrogen-bond donating (acidic) character. A Gibbs free-energy descriptor. Maps the hydrogen bond acidity descriptor (A). |

| Basicity PSP (σGb) | σGb = 100 * B / Vm [20] |

Hydrogen-bond accepting (basic) character. A Gibbs free-energy descriptor. Maps the hydrogen bond basicity descriptor (B). |

A key thermodynamic advantage of the PSP framework is its ability to directly calculate the Gibbs free energy change (G_HB) upon the formation of a hydrogen bond (or Lewis acid-base interaction) using the acidity and basicity PSPs [20]:

-G_HB = 2 * Vm * σGa * σGb = 20000 * A * B (at 298 K) [20].

This free energy change can be further decomposed into enthalpy (E_HB) and entropy (S_HB) contributions using the derived working equations [20]:

E_HB = -30,450 * A * B

S_HB = -35.1 * A * B

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for extracting thermodynamic information from LSER descriptors via the PSP framework.

Experimental and Computational Protocols

Protocol 1: Determination of LSER Descriptors for PSP Calculation

For compounds where LSER descriptors are not available in databases, they can be determined experimentally via chromatographic methods.

- Objective: To experimentally determine the solute-specific LSER descriptors (A, B, S) required for PSP calculation.

- Materials and Reagents:

- Analytical HPLC System: Configured with multiple detection modes (e.g., DAD, RID).

- Stationary Phases: A system of eight reversed-phase, normal-phase, and hydrophilic interaction (HILIC) HPLC columns to probe diverse interactions [22].

- Mobile Phases: Solvents of varying polarity and hydrogen-bonding character (e.g., water, acetonitrile, methanol, alkanes).

- Test Solutes: The compounds of interest (e.g., pharmaceuticals, pesticides).

- Reference Compounds: A set of standards with known LSER descriptors for column calibration.

- Procedure:

- Column Calibration: Separately inject a set of reference compounds with known LSER descriptors onto each of the eight HPLC columns. For each reference compound, measure the retention factor (log k).

- Multiple Linear Regression: For each column, perform a multiple linear regression to establish a system-specific equation:

log k = c + eE + sS + aA + bB + vVx[22]. This determines the system constants (e, s, a, b, v) for that column. - Analyze Target Solutes: Inject the target solutes onto each calibrated HPLC column and record their retention factors.

- Descriptor Determination: Using the measured retention factors (log k) across the multiple chromatographic systems and the known system constants, perform a multi-variable regression analysis to solve for the solute's descriptors (E, S, A, B, Vx). The McGowan volume (Vx) can often be calculated from molecular structure prior to this step [20].

- Notes: This protocol is particularly suited for complex, multifunctional compounds like pharmaceuticals and pesticides, which often have A, S, and B values at the upper end of the known numerical range [22].

Protocol 2: Computational Calculation of PSPs from LSER Descriptors

Once the LSER descriptors are known, either from databases or experimental determination, the PSPs can be calculated directly.

- Objective: To calculate the full set of Partial Solvation Parameters from a compound's known LSER descriptors and molar volume.

- Prerequisites:

- LSER Descriptors: A, B, S, E, Vx for the target compound.

- Molar Volume (Vm): The molar volume of the compound at the temperature of interest.

- Computational Procedure:

- Calculate Dispersion PSP (σd): Apply the formula

σd = 100 * (3.1 * Vx + E) / Vm[20]. - Calculate Polarity PSP (σp): Apply the formula

σp = 100 * S / Vm[20]. - Calculate Acidity PSP (σGa): Apply the formula

σGa = 100 * A / Vm[20]. - Calculate Basicity PSP (σGb): Apply the formula

σGb = 100 * B / Vm[20].

- Calculate Dispersion PSP (σd): Apply the formula

- Data Analysis:

- The calculated PSPs can be used to estimate the cohesive energy density (ced) contribution from hydrogen bonding:

ced_HB = - (r1 * ν11 * E_HB) / Vm, wherer1is the number of molecular segments, andν11is the number of hydrogen bonds per mole [20]. - The total solubility parameter can be approximated from the PSPs, acknowledging that

ced_total ≈ σd² + σp² + σGa² + σGb²[21].

- The calculated PSPs can be used to estimate the cohesive energy density (ced) contribution from hydrogen bonding:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for LSER-PSP Studies

| Item | Function / Application | Relevant Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-Chemistry HPLC Column Set | Set of 8 reversed-phase, normal-phase, and HILIC columns for comprehensive profiling of solute interactions with different stationary phases. | Protocol 1 [22] |

| Reference Compound Library | A curated set of chemical standards with pre-established, reliable LSER descriptors. Used to calibrate chromatographic systems. | Protocol 1 [22] |

| Inverse Gas Chromatography (IGC) | An alternative technique to determine PSPs/LSER descriptors of solid materials (e.g., APIs, polymers) by using probe gases. | Cited in [20] |

| COSMO-RS Software & Database | Quantum chemistry-based thermodynamic model and database (e.g., COSMObase) used for in-silico estimation of PSPs and σ-profiles. | Cited in [21] [20] |

| Abraham LSER Database | A freely accessible database containing a large inventory of experimentally derived LSER descriptors for numerous compounds. | Cited in [9] [20] |

Data Presentation and Application in Pharmaceuticals

The utility of the LSER-PSP linkage is demonstrated by its application in predicting critical properties. The following table showcases calculated hydrogen-bond thermodynamics for hypothetical molecular pairs, derived directly from their A and B descriptors [20].

Table 3: Calculated Hydrogen-Bond Thermodynamics from LSER Descriptors (at 298 K)

| Acid-Base Pair Interaction | A (Acid) * B (Base) | G_HB (J/mol) | E_HB (J/mol) | S_HB (J/(mol·K)) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weak Interaction | 0.1 | -2,000 | -3,045 | -3.51 |

| Moderate Interaction | 0.3 | -6,000 | -9,135 | -10.53 |

| Strong Interaction | 0.6 | -12,000 | -18,270 | -21.06 |

This framework has been successfully applied to predict activity coefficients at infinite dilution, octanol/water partition coefficients, and the miscibility of pharmaceuticals in various solvents [21] [20]. For instance, in drug development, PSPs calculated via this method have proven helpful in predicting drug solubility in various solvents and in calculating the different contributions to surface energy, which is critical for formulation design [20]. The ability to convert PSPs back to classical solubility parameters or LSER values creates a unified, versatile tool for pharmaceutical scientists [20].

Concluding Remarks

The formalized linkage between LSER descriptors and Partial Solvation parameters provides a robust, thermodynamically sound pathway for enriching solubility prediction models. By bridging the gap between a widely used empirical database (LSER) and an equation-of-state-based framework (PSP), researchers can extract profound thermodynamic insights—such as the free energy, enthalpy, and entropy of hydrogen bonding—from readily available molecular descriptors. This integration enhances the predictive power for complex phenomena like solute partitioning and miscibility, offering a more nuanced and effective tool for applications ranging from solvent selection in drug formulation to the design of novel polymeric materials.

Implementing LSER Models: From Theory to Pharmaceutical Practice

Linear Solvation Energy Relationships (LSER) represent a pivotal quantitative approach for predicting solvation-related properties, crucially applied within pharmaceutical research to address the pervasive challenge of poor drug solubility. The LSER model quantitatively correlates the free-energy-related properties of a solute to a set of molecular descriptors that encode specific intermolecular interaction capabilities [9]. For researchers and drug development professionals, a robust LSER model provides an indispensable tool for solvent screening, crystallization process optimization, and guiding drug dosage form design, thereby directly enhancing drug production efficiency and clinical applicability [23]. This protocol details a comprehensive, step-by-step methodology for constructing, validating, and applying a thermodynamically grounded LSER model, with a particular emphasis on solubility parameter determination for active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs).

Theoretical Framework of LSER

The foundational principle of LSER is that a free-energy-related property (log P) of a solute can be expressed as a linear combination of its molecular descriptors and the complementary system coefficients [9]. The two primary equations used for solute transfer between phases are:

For partitioning between two condensed phases (e.g., water-to-organic solvent): log (P) = cₚ + eₚE + sₚS + aₚA + bₚB + vₚVₓ [9]

For gas-to-organic solvent partitioning: log (Kₛ) = cₖ + eₖE + sₖS + aₖA + bₖB + lₖL [9]

Table: LSER Solute Molecular Descriptors

| Descriptor | Symbol | Physical Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| McGowan's Characteristic Volume | Vₓ | Represents the size of the solute molecule and encodes dispersion interactions [9]. |

| Gas-Liquid Partition Coefficient | L | The logarithm of the gas-hexadecane partition coefficient, describing solute partitioning into a van der Waals solvent [9]. |

| Excess Molar Refraction | E | Measures the solute's ability to interact via polarizability, often related to π- or n-electrons [9]. |

| Dipolarity/Polarizability | S | Characterizes the solute's ability to engage in dipole-dipole and dipole-induced dipole interactions [9]. |

| Hydrogen Bond Acidity | A | Quantifies the solute's ability to donate a hydrogen bond [9]. |

| Hydrogen Bond Basicity | B | Quantifies the solute's ability to accept a hydrogen bond [9]. |

The lower-case coefficients (e.g., eₚ, sₚ, aₚ, bₚ, vₚ) in these equations are the system-specific constants, or LSER coefficients. They are considered solvent descriptors that embody the complementary effect of the solvent (or phase) on the solute-solvent interactions. These coefficients are typically determined via multiple linear regression against a dataset of experimental values for a wide range of solutes with known descriptors [9].

Experimental Determination of Solubility Data

The accuracy of any LSER model is contingent on the quality of the experimental solubility data used for its calibration. This section outlines a standardized protocol for obtaining reliable solubility measurements.

Materials and Equipment

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Equipment

| Item Name | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Analytical Balance | Precisely weighing the drug (API) and solvents. |

| Thermostatic Shaker Bath | Maintaining a constant temperature during the equilibration process. |

| HPLC System with Detector | Quantifying the concentration of the drug in the saturated solution (e.g., carprofen) [23]. |

| UV-Vis Spectrophotometer | An alternative method for concentration determination of drugs with suitable chromophores [24]. |

| Membrane Filters (e.g., 0.45 μm) | Removing undissolved solid particles from the saturated solution prior to analysis. |

| Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC) | Determining key thermal properties of the pure API, such as melting temperature (Tm) and enthalpy of fusion (ΔfusH) [23]. |

| X-ray Powder Diffractometer (PXRD) | Verifying the solid-state form (polymorph) of the API before and after solubility experiments to ensure no crystal transformation occurred during dissolution [23]. |

Solubility Measurement Protocol: The Static Method

The following is a detailed protocol for measuring saturation solubility, adapted from the methodology successfully applied to carprofen [23].

- Preparation of Saturated Solutions: An excess amount of the solid drug (API) is added to a known volume of a pure or mixed solvent in a sealed vessel.

- Equilibration: The suspensions are placed in a thermostatic shaker bath. Equilibrium is achieved by agitating the suspensions at a constant temperature (e.g., between 288.15 K and 328.15 K) for a sufficient duration, typically at least 24 hours, to ensure that the solid phase is in equilibrium with the solution [23] [24].

- Sampling: After equilibration, the agitation is stopped to allow the undissolved solids to settle.

- Filtration and Dilution: An aliquot of the saturated supernatant is carefully withdrawn and filtered through a membrane filter to remove any fine particulate matter. The filtrate may be diluted with an appropriate solvent if necessary, to fall within the quantitative range of the analytical method.

- Concentration Analysis: The concentration of the drug in the filtered (and potentially diluted) solution is determined using a pre-calibrated analytical method, such as High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) or UV-Vis spectrophotometry [23] [24].

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for static solubility measurement.

Solid-State Characterization

To ensure the integrity of the solubility data, it is critical to verify that the solid phase of the API remains unchanged throughout the dissolution process.

- Pre-Experiment: Characterize the starting API material using PXRD and DSC.

- Post-Experiment: Recover the undissolved solid from the equilibrium slurry and subject it to PXRD analysis. Compare the diffraction patterns before and after the experiment. The absence of new peaks confirms no crystal transformation, solvate formation, or degradation occurred, thereby validating the solubility measurement [23].

Computational Implementation and Model Fitting

Assembling the Data Matrix

Construct a data matrix where each row represents a single solute-solvent system (or a single experimental condition) and each column represents a variable. The core data required includes:

- Dependent Variable (Y): The experimentally determined property (e.g., log S, log P).

- Independent Variables (X): The six solute-specific molecular descriptors (Vₓ, L, E, S, A, B) for each solute in the dataset.

Regression Analysis and Model Validation

The core computational workflow for building and validating the LSER model is as follows:

Diagram 2: Computational workflow for LSER model building and validation.

- Data Splitting: Divide the full dataset into a training set (e.g., 70-80%) for model calibration and a test set (e.g., 20-30%) for independent validation.

- Multiple Linear Regression (MLR): Use the training set to perform MLR, solving for the LSER coefficients (system constants) that minimize the difference between the experimental and predicted log P or log S values.

- Model Validation: Use the derived model to predict the properties of the solutes in the test set. Compare these predictions to the experimental values.

- Statistical Analysis: Evaluate the model's performance using statistical metrics [23]:

- R² (Coefficient of Determination): Measures the proportion of variance in the dependent variable that is predictable from the independent variables. An R² > 0.9 typically indicates a strong model.

- Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD): Quantifies the average magnitude of the prediction errors.

- Absolute Relative Deviation (ARD): Provides a relative measure of the error for individual data points.

Extraction of Thermodynamic Information

A significant advantage of the LSER framework is its foundation in free energy, which allows for the extraction of profound thermodynamic insights into the dissolution process. The relationship between the Gibbs free energy of solvation and the LSER model is direct: log Kₛ ∝ -ΔGsol/RT. By analyzing the relative magnitudes of the LSER coefficients and their corresponding terms (e.g., aₚA vs bₚB), one can deconvolute the contributions of different interaction types (e.g., hydrogen bonding acidity/basicity vs. dispersion) to the overall solvation free energy [9].

Furthermore, by measuring solubility at multiple temperatures and applying van't Hoff analysis or correlating the data with models like the Apelblat equation, it is possible to extract apparent standard thermodynamic functions of dissolution [23]:

- Enthalpy (ΔH⁰sol): Indicates whether the dissolution process is endothermic (ΔH⁰sol > 0) or exothermic (ΔH⁰sol < 0).

- Entropy (ΔS⁰sol): Reflects changes in molecular order.

- Gibbs Free Energy (ΔG⁰sol): Determines the overall spontaneity of the process.

The relative contribution of enthalpy (ξH) and entropy (ξS) to the Gibbs free energy can be calculated. For many APIs like carprofen, the dissolution process is endothermic and entropy-driven, meaning the entropy term (TΔS⁰sol) is the dominant contributor to a negative ΔG⁰sol at higher temperatures [23].

Application in Solubility Parameter Determination

The LSER model provides a powerful pathway for determining and interpreting the solubility parameters of APIs. The LSER solvent coefficients (eₚ, sₚ, aₚ, bₚ, vₚ) offer a quantitative profile of the solvent's interaction capabilities. A solvent that is optimal for dissolving a specific API will have a coefficient profile that closely matches the descriptor profile of the API. For instance, a high hydrogen bond basicity descriptor (B) in an API necessitates a solvent with a large hydrogen bond acidity coefficient (aₚ) for strong complementary interaction [23] [9].

This LSER analysis can be integrated with traditional solubility parameter theories, such as Hansen Solubility Parameters (HSPs). The LSER descriptors provide a more granular, chemically intuitive breakdown of the intermolecular forces that constitute the total solubility parameter. The S descriptor relates to the polar component (δP), while the A and B descriptors inform the hydrogen bonding component (δH). The Vₓ and L descriptors are linked to the dispersion component (δD). Therefore, a robust LSER model does not just predict solubility; it explains it in terms of fundamental, quantitative molecular interactions, providing a solid basis for rational solvent selection in pharmaceutical process development [23].

The development of new chemical entities (NCEs) in the pharmaceutical industry faces a significant challenge: approximately 90% of these compounds exhibit poor water solubility, which severely limits their bioavailability and therapeutic potential [24]. Among innovative strategies to overcome this hurdle, supramolecular chemistry offers cucurbit[7]uril (CB[7]) as a powerful macrocyclic host capable of forming stable inclusion complexes with hydrophobic drugs [25]. This case study explores the application of Linear Solvation Energy Relationships (LSER) modeling to predict the solubilizing effect of CB[7] on poorly soluble Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs), providing researchers with a computational framework to prioritize experimental work.

CB[7] represents an exceptional molecular container with distinctive advantages over traditional excipients like cyclodextrins. Its structure features a hydrophobic cavity and polar carbonyl portals, enabling exceptionally high binding affinities (up to 10¹⁵ M⁻¹ in water) with various drug molecules [24]. Unlike cyclodextrins, CB[7] demonstrates remarkable stability across wide pH ranges, including strong acidic and weak alkaline conditions [24]. With moderate aqueous solubility (20-30 mM) and established biocompatibility profiles showing negligible systemic toxicity in vitro and in vivo, CB[7] presents an attractive platform for pharmaceutical formulation [25] [24].

The LSER model transforms the traditionally empirical process of excipient selection into a rational, prediction-driven approach. By quantifying molecular interactions between drugs, CB[7], and the aqueous environment, researchers can efficiently identify optimal candidate compounds for experimental validation, significantly accelerating pre-formulation stages.

Theoretical Background and LSER Model Development

LSER Fundamentals for Solubility Prediction

Linear Solvation Energy Relationships represent a well-established theoretical framework that correlates molecular descriptors with physicochemical properties. In pharmaceutical contexts, LSER models describe how structural features influence solubility, permeability, and other critical parameters. The general LSER equation for solubility takes the form:

log S = c + vD + eE + iL

where S represents solubility, D corresponds to molecular dimension descriptors, E encapsulates molecular interaction parameters, L reflects macroscopic properties, and c is a constant [24].

When adapted for predicting CB[7]-mediated solubility enhancement, the standard LSER model requires extension to account for the ternary complex system involving the drug, CB[7], and aqueous environment. The modified multi-parameter model incorporates specific descriptors capturing host-guest interactions and complex properties [26] [24].

Key Molecular Descriptors in CB[7]-Drug Solubilization

Research has identified five critical parameters governing drug solubilization by CB[7]:

- Surface area of inclusion complexes (A₃): Reflects the molecular footprint of the drug-CB[7] complex, influencing solvation energy [24]

- LUMO energy of inclusion complexes (E₃LUMO): Indicates the electron-accepting potential of the complex [24]

- Polarity index of inclusion complexes (I₃): Measures overall polarity changes upon complexation [24]

- Electronegativity of drugs (χ₁): Affects charge transfer interactions with CB[7] portals [24]

- Oil-water partition coefficient of drugs (log P₁w): Represents inherent drug hydrophobicity [24]

These parameters can be computationally derived using Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations, providing a quantitative basis for solubility predictions without extensive experimental screening [26].

Computational Protocol: LSER Model Implementation

Density Functional Theory Calculations

Objective: To compute molecular descriptors for drugs and their CB[7] inclusion complexes.

Procedure:

- Molecular Optimization: Perform geometry optimization for each drug molecule and proposed CB[7]-drug complex using DFT methods (B3LYP/6-31G* level)

- Electronic Property Calculation: Calculate frontier molecular orbitals (HOMO/LUMO) to derive electronegativity values

- Surface Analysis: Determine solvent-accessible surface area for optimized complex structures

- Polarity Assessment: Compute dipole moments and polarizability tensors

- Partition Coefficient Estimation: Calculate theoretical log P values using fragmentation methods

Software Tools: Gaussian 16, ORCA, or similar computational chemistry packages

LSER Model Application Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the integrated computational and experimental workflow for predicting and validating CB[7]-mediated solubility enhancement:

Experimental Validation Protocol

Phase Solubility Studies

Objective: To experimentally determine solubility enhancement of drugs by CB[7] and validate computational predictions.

Materials:

- CB[7] stock solution (0-30 mM in purified water)

- Drug compounds (high purity, characterized by HPLC)

- Aqueous buffer (appropriate for drug stability)