LSER Analysis for Green Solvent Selection: A Sustainable Framework for Biomedical Research

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive guide to applying Linear Solvation Energy Relationships (LSER) for sustainable solvent selection.

LSER Analysis for Green Solvent Selection: A Sustainable Framework for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive guide to applying Linear Solvation Energy Relationships (LSER) for sustainable solvent selection. It bridges the gap between theoretical LSER models and practical green chemistry principles, offering a foundational understanding, methodological application steps, troubleshooting for common optimization challenges, and validation against established green metrics like Process Mass Intensity (PMI) and Life Cycle Assessment (LCA). By integrating LSER with tools like the CHEM21 Selection Guide and the ACS GCI Solvent Selection Tool, this framework supports the pharmaceutical industry's transition towards circular economy principles, enabling the design of safer, more efficient, and environmentally benign chemical processes.

The Principles of Green Chemistry and LSER Fundamentals

Green chemistry is the design of chemical products and processes that reduce or eliminate the use or generation of hazardous substances, applying across the entire life cycle of a chemical product [1]. Its fifth principle specifically mandates the use of safer solvents and auxiliaries, emphasizing that auxiliary substances must be minimized and made innocuous when used [2]. This principle is particularly crucial as solvents often account for the majority of the mass and up to 75% of the cumulative life cycle environmental impact in standard batch chemical operations [2]. With approximately 30 million metric tons of solvents used globally each year across industrial, manufacturing, and consumer goods applications, transitioning to safer alternatives represents a critical challenge and opportunity for sustainable chemistry innovation [3].

The imperative for solvent substitution has gained urgency with recent regulatory actions. For instance, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency's ban on most uses of the carcinogenic solvent dichloromethane (DCM) has forced educational institutions and industries to seek alternatives [4]. DCM exemplifies the historical compromise in solvent selection—it effectively dissolves compounds, evaporates easily, doesn't catch fire, but poses significant carcinogenic risks [4]. This regulatory shift underscores a broader transition toward evaluating solvents not merely on immediate functionality but on their comprehensive environmental, health, and safety profiles throughout their life cycle.

Safer Solvent Substitution: Framework and Methodologies

Theoretical Framework for Solvent Evaluation

A holistic framework for solvent selection extends beyond single-parameter assessment to incorporate multiple dimensions of sustainability. The 12 Principles of Green Chemistry provide the foundational framework for this evaluation, emphasizing waste prevention, atom economy, less hazardous syntheses, and specifically, the use of safer solvents and auxiliaries [1] [5]. These principles collectively guide the development of methodologies that are both effective and environmentally benign.

Modern solvent assessment incorporates three key perspectives that align with the Principles of Green Chemistry:

- Hazard Reduction: Focuses on minimizing toxicity, carcinogenicity, and environmental persistence (Principles 3, 4, 5) [1]

- Resource Efficiency: Emphasizes atom economy, waste prevention, and renewable feedstocks (Principles 1, 2, 7) [6]

- Energy Efficiency: Prioritizes reduced energy consumption and ambient temperature operations (Principle 6) [6] [5]

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) provides a comprehensive methodology for evaluating the environmental footprint of solvents across all stages—from raw material extraction and manufacturing to use and disposal [5]. This systematic approach captures often-overlooked impacts, such as the energy demands of instrument manufacturing or the end-of-life treatment of lab equipment, enabling researchers to make informed decisions that genuinely reduce overall environmental impact rather than simply shifting burdens between different categories [5].

Quantitative Assessment Tools

Several standardized tools have emerged to enable quantitative comparison of solvent alternatives:

Table 1: Quantitative Tools for Green Solvent Assessment

| Assessment Tool | Developer | Key Metrics | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| DOZN 2.0 [6] | MilliporeSigma | Scores 0-100 across 12 principles grouped into hazard, resource use, and energy efficiency | Direct comparison of chemicals or synthesis routes; web-based, free access |

| ACS Solvent Selection Tool [7] | ACS GCI Pharmaceutical Roundtable | PCA of 70 physical properties; health, air, water impact categories; ICH classification | Pharmaceutical process development; 272 solvents in database |

| AGREE Tool [8] | Academic Research | 0-1 score based on 12 GAC principles with weighted penalty points | Comprehensive greenness evaluation of analytical methods |

| Green Analytical Procedure Index (GAPI) [8] | Academic Research | Color-coded pictogram evaluating entire method life cycle | Quick visual assessment of analytical method greenness |

These tools transform subjective evaluation into data-driven decision making. For example, DOZN 2.0 generates quantitative scores that allow direct comparison between alternative chemicals considered for the same application, as well as between alternative synthesis manufacturing processes for the same chemical product [6]. The tool utilizes readily available data, including manufacturing inputs and Globally Harmonized System (GHS) information, making it practical for industrial implementation while based on generally accepted industry practices [6].

Experimental Protocols: Safer Solvent Substitution in Practice

Protocol 1: Substitution of Dichloromethane in Educational Laboratories

Recent research demonstrates practical pathways for replacing hazardous solvents with safer alternatives. The following protocol outlines the substitution of dichloromethane (DCM) with ethyl acetate and MTBE for the isolation of active ingredients from pain relievers and synthesis of wintergreen oil, representing a case study with broader applicability to pharmaceutical and analytical contexts [4].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for DCM Substitution Protocol

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Safety & Environmental Profile |

|---|---|---|

| Ethyl Acetate | Primary extraction solvent replacement for DCM in pain reliever lab | Lower carcinogenicity vs. DCM; higher boiling point |

| MTBE (Methyl tert-butyl ether) | Extraction solvent for wintergreen oil synthesis | Effective for compound separation; higher boiling point |

| Baking Soda (Sodium Bicarbonate) | Weaker base substitute for lye (sodium hydroxide) | Slows unwanted side reactions; safer handling |

| Salicylic Acid | Starting material for wintergreen oil synthesis | Natural derivative; historically used for pain relief |

| Rotary Evaporator | Solvent evaporation equipment | Accommodates higher boiling points of alternative solvents |

Methodological Workflow

The experimental workflow for solvent substitution follows a systematic approach to ensure both effectiveness and safety:

Detailed Experimental Procedure

A. Isolation of Active Ingredients from Pain Relievers Using Ethyl Acetate

Preparation: Crush 500 mg of over-the-counter pain relief tablets containing aspirin and phenacetin using a mortar and pestle.

Extraction: Transfer the powder to a separation funnel with 10 mL of ethyl acetate. Add 5 mL of 5% sodium bicarbonate (baking soda) solution instead of traditional lye to minimize side reactions.

Separation: Gently shake the mixture and allow layers to separate. Drain the aqueous layer while retaining the organic (ethyl acetate) layer containing the dissolved active ingredients.

Evaporation: Transfer the ethyl acetate layer to a rotary evaporator. Note that evaporation requires more time than DCM due to ethyl acetate's higher boiling point (77°C vs. 40°C for DCM).

Analysis: Identify and quantify the isolated compounds using thin-layer chromatography or other appropriate analytical methods.

B. Synthesis of Wintergreen Oil Using MTBE

Reaction Setup: Combine 100 mg of salicylic acid with 2 mL of methanol and 0.1 mL of sulfuric acid as catalyst in a small round-bottom flask.

Esterification: Heat the mixture at 60°C for 30 minutes with occasional stirring to form methyl salicylate.

Extraction: Cool the reaction mixture and transfer to a separation funnel. Add 5 mL of MTBE and 3 mL of water. Shake gently and allow layers to separate.

Isolation: Collect the MTBE layer containing the synthesized wintergreen oil (methyl salicylate).

Characterization: Confirm successful synthesis by noting the characteristic wintergreen odor and through thin-layer chromatography analysis.

Key Adaptation Notes: The substitution process requires accommodating the higher boiling points of ethyl acetate (77°C) and MTBE (55°C) compared to DCM (40°C). This extends process time slightly but significantly improves safety profiles. Additionally, replacing strong bases like lye with milder alternatives such as baking soda reduces unwanted side reactions while maintaining effectiveness [4].

Protocol 2: Solvent Selection Using the ACS Solvent Tool

For researchers developing new methods, the ACS Solvent Selection Tool provides a systematic approach to identifying greener alternatives. This protocol outlines the procedure for using this tool in pharmaceutical process development.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for Computational Solvent Screening

| Resource | Function/Application | Access Method |

|---|---|---|

| ACS Solvent Selection Tool [7] | Interactive solvent selection based on PCA of physical properties | Web-based: https://acsgcipr.org/tools/solvent-tool/ |

| Database of 272 Solvents | Includes research, process and next-generation green solvents | Integrated within ACS Tool |

| Physical Properties Database | 70 physical properties (30 experimental, 40 calculated) | Part of tool functionality |

| Impact Category Metrics | Health, air, water impact assessments; LCA data | Included in solvent profiles |

Methodological Workflow

The computational screening process follows a structured pathway:

Detailed Experimental Procedure

Requirement Definition:

- Identify the critical solvent properties needed for your specific application (e.g., polarity, boiling point, hydrogen bonding capability, dielectric constant).

- Define any constraints regarding functional group compatibility, ICH classification requirements, or specific safety parameters.

Tool Navigation:

- Access the ACS Solvent Selection Tool through the provided URL.

- Familiarize yourself with the interface, including the principal component analysis (PCA) map display and filtering options.

Solvent Screening:

- Use the PCA map to identify solvents with similar physical and chemical properties to your target but with improved safety profiles.

- Apply filters based on functional group compatibility to exclude solvents that might react with your system components.

- Set thresholds for environmental impact categories, including health, air, and water impacts.

Comparative Analysis:

- Generate radar charts for the top 3-5 candidate solvents to visually compare their property profiles.

- Examine the ICH solvent classification and concentration limits for each candidate, prioritizing Class 3 (low hazard) over Class 1 (high hazard) solvents.

- Review additional plant accommodation data, including flash point, auto-ignition temperature, and VOC potential.

Validation Planning:

- Select 2-3 lead candidates for experimental validation.

- Export the solvent data for integration into Design of Experiment (DoE) protocols.

- Design a focused experimental plan to test the performance of candidate solvents in your specific application.

This methodology enhances the view toward a more holistic perspective and robust solvent screening process, potentially reducing the next steps in solvent evaluation and process development [9]. The tool's strength lies in its avoidance of oversimplified indexes or scores, instead providing multidimensional data that highlights where issues or benefits might arise with specific solvent choices [9].

Integration with LSER Analysis in Green Chemistry Research

The framework for safer solvent selection aligns directly with Linear Solvation Energy Relationship (LSER) analysis, which provides a quantitative basis for understanding molecular-level solvent-solute interactions. While traditional solvent selection often relied on empirical trial-and-error, LSER analysis offers a principled approach to predicting solvent performance based on well-characterized molecular descriptors.

In the context of green chemistry, LSER principles can be integrated with the tools and protocols described in this document to create a predictive framework for solvent substitution. The physical properties database underlying the ACS Solvent Selection Tool [7], which includes 70 experimental and calculated parameters, captures many of the same molecular interactions described in LSER models—particularly polarity, polarizability, and hydrogen-bonding capacity.

For researchers incorporating LSER analysis into solvent selection for green chemistry, the following integrated approach is recommended:

Characterize Solute Requirements: Use LSER parameters to define the specific solvation interactions required for your target compounds.

Screen for Green Alternatives: Apply the ACS Solvent Tool or similar databases to identify solvents with similar LSER characteristics to conventional solvents but improved environmental, health, and safety profiles.

Validate Experimentally: Implement the experimental substitution protocols outlined in Section 3.1 to confirm performance of candidate solvents in practical applications.

Quantify Green Metrics: Apply assessment tools like DOZN 2.0 [6] to quantitatively compare the green chemistry performance of alternative solvents.

This integrated approach enables researchers to move beyond simple replacement to optimized solvent system design, where both molecular-level interactions and broader environmental impacts are considered simultaneously. The case study of DCM replacement [4] demonstrates that successful substitution often requires not just switching solvents but optimizing the entire process—including adjustments to auxiliary reagents, reaction conditions, and equipment parameters.

As green chemistry continues to evolve, the integration of computational approaches like LSER analysis with practical assessment tools and experimental protocols will be essential for developing next-generation solvent systems that meet both performance and sustainability requirements across pharmaceutical, industrial, and analytical applications.

The Linear Solvation Energy Relationship (LSER), also known as the Abraham solvation parameter model, is a highly successful predictive tool in chemical, biomedical, and environmental research [10]. This model provides a robust framework for understanding and predicting solute transfer between phases—a process fundamental to numerous applications, from solvent selection in green chemistry to drug absorption in pharmaceutical development. The core principle of LSER is that free-energy-related properties of a solute can be correlated with molecular descriptors that quantitatively represent its ability to engage in different types of intermolecular interactions [10]. The remarkable feature of LSER is its linearity, which holds even for strong, specific interactions like hydrogen bonding, providing a powerful tool for researchers and scientists [10].

The Fundamental LSER Equations

The LSER model operationalizes through two primary equations that quantify solute transfer between different phases [10].

Key LSER Equations

| Equation Name | Mathematical Form | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Condensed Phase Partitioning | log (P) = cp + epE + spS + apA + bpB + vpVx [10] |

Predicts partition coefficients between two condensed phases (e.g., water-to-organic solvent) [10]. |

| Gas-to-Solvent Partitioning | log (KS) = ck + ekE + skS + akA + bkB + lkL [10] |

Predicts gas-to-organic solvent partition coefficients [10]. |

| Solvation Enthalpy | ΔHS = cH + eHE + sHS + aHA + bHB + lHL [10] |

Used to calculate enthalpies of solvation [10]. |

In these equations, the lower-case coefficients (c, e, s, a, b, v, l) are system-specific parameters that describe the solvent phase's properties. The uppercase letters are the solute's molecular descriptors [10].

Molecular Descriptors and System Coefficients

The following table details the six core molecular descriptors used in the LSER model to characterize a solute [10].

| Descriptor | Symbol | Physical Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| McGowan's Characteristic Volume | Vx |

Represents the solute's molecular volume, related to the energy cost of forming a cavity in the solvent [10]. |

| Gas-Hexadecane Partition Coefficient | L |

Describes the solute's ability to partition into a hexadecane reference phase at 298 K [10]. |

| Excess Molar Refraction | E |

Quantifies polarizability contributions from pi- and n-electrons [10]. |

| Dipolarity/Polarizability | S |

Measures the solute's ability to engage in dipole-dipole and dipole-induced dipole interactions [10]. |

| Hydrogen Bond Acidity | A |

Characterizes the solute's ability to donate a hydrogen bond [10]. |

| Hydrogen Bond Basicity | B |

Characterizes the solute's ability to accept a hydrogen bond [10]. |

The system coefficients (e.g., a, b, v in the equations) represent the complementary properties of the solvent phase. For instance, the a coefficient reflects the solvent's hydrogen bond basicity, while the b coefficient reflects its hydrogen bond acidity [10]. These are typically determined by fitting experimental data for a variety of solutes [10].

Experimental Protocol: Applying LSER for Solvent Selection

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for using the LSER model to predict partition coefficients (log P) for solvent selection in green chemistry applications, using the partitioning between Low-Density Polyethylene (LDPE) and water as a specific, validated example [11].

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item Name | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| LSER Solute Descriptors | Molecular parameters (E, S, A, B, Vx, L) for the compound of interest. These can be obtained from experimental data or predicted via QSPR tools if experimental values are unavailable [11]. |

| LSER System Parameters | Pre-determined coefficients for the specific solvent system of interest. For the LDPE/water system, the model is: log Ki,LDPE/W = -0.529 + 1.098E - 1.557S - 2.991A - 4.617B + 3.886Vx [11]. |

| Chemical Database | A curated database, such as the LSER database, to retrieve or verify solute descriptors and system parameters [10] [11]. |

| QSPR Prediction Tool | A software tool for predicting LSER solute descriptors based solely on the compound's chemical structure, used when experimental descriptors are not available [11]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Compound Identification: Clearly identify the neutral compound for which the partition coefficient needs to be predicted.

- Descriptor Sourcing: Obtain the six LSER molecular descriptors (E, S, A, B, Vx, L) for the compound.

- Model Selection: Identify the correct pre-established LSER equation for your solvent system. For this example, use the LDPE/water model:

log Ki,LDPE/W = -0.529 + 1.098E - 1.557S - 2.991A - 4.617B + 3.886Vx[11]. - Calculation: Substitute the solute descriptors into the selected LSER equation and compute the value of the partition coefficient,

log Ki,LDPE/W. - Validation (Recommended): For critical applications, benchmark the prediction against known experimental data if available. When using predicted descriptors, expect a slightly higher margin of error (e.g., RMSE ≈ 0.511 for the LDPE/water system) compared to using experimental descriptors (RMSE ≈ 0.352) [11].

- Interpretation: A higher positive

log Kvalue indicates a greater tendency for the solute to partition into the polymer (LDPE) phase over the water phase. This can guide decisions on solvent suitability for extraction, purification, or assessing material compatibility.

Advanced Applications and Thermodynamic Basis

Extraction of Thermodynamic Information

The LSER database is a rich source of thermodynamic information on intermolecular interactions. The products of solute descriptors and system coefficients (e.g., A1a2 and B1b2 in the partition equations) can be used to estimate the hydrogen bonding contribution to the free energy of solvation [10]. A key challenge and active area of research is the extraction of this information to estimate the free energy change (ΔGhb), enthalpy change (ΔHhb), and entropy change (ΔShb) upon the formation of individual hydrogen bonds [10]. The Partial Solvation Parameters (PSP) approach is one thermodynamic framework being developed to facilitate this extraction, with hydrogen-bonding PSPs (σa and σb) specifically designed to reflect a molecule's acidity and basicity characteristics [10].

Benchmarking and Comparison to Other Phases

LSER models allow for the direct comparison of sorption behavior across different materials. For instance, the LDPE/water LSER model can be compared to models for other polymers like polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), polyacrylate (PA), and polyoxymethylene (POM) [11]. Such analysis reveals that polymers with heteroatomic building blocks (e.g., POM and PA) exhibit stronger sorption for polar, non-hydrophobic solutes compared to LDPE. However, for highly hydrophobic solutes (log Ki,LDPE/W > 3-4), all four polymers show roughly similar sorption behavior [11]. Furthermore, by considering only the amorphous fraction of LDPE as the effective phase volume, the model constant shifts, making the resulting LSER equation more similar to that for a corresponding n-hexadecane/water system, thereby strengthening the connection between polymer partitioning and partitioning into liquid phases [11].

Why LSER? Aligning Molecular-Level Understanding with Green Chemistry Goals

In the pharmaceutical industry and broader chemical sector, solvents constitute over half of the input mass and associated waste in most manufacturing processes, creating significant environmental challenges [12]. The transition from traditional linear economic models to a circular economy framework—grounded in resource efficiency, waste minimization, and material regeneration—demands more sophisticated approaches to solvent selection [12]. While traditional solvent selection guides provide valuable environmental, health, and safety (EHS) rankings, they often lack the molecular-level insight needed to rationally design or select optimal solvents for specific applications. The Linear Solvation Energy Relationship (LSER) methodology addresses this critical gap by connecting fundamental molecular interactions with solvent performance, enabling researchers to make predictively green choices that align solvation requirements with sustainability goals. This application note details how LSER principles can be integrated into sustainable solvent selection workflows, particularly for pharmaceutical development professionals seeking to bridge molecular understanding with circular economy objectives.

LSER Fundamentals: Decoding Molecular Interactions

The LSER framework provides a quantitative model that correlates solvent effects on chemical processes, reactivity, and solubility with defined molecular-level interaction parameters. The general LSER equation is expressed as:

SP = c + eE + sS + aA + bB + vV

Where SP represents the solvent-dependent property being studied (e.g., solubility, reaction rate, chromatographic retention), and the capital letters represent the complementary properties of the solvent. The lower-case letters are coefficients determined by regression analysis that measure the relative susceptibility of the process to the different intermolecular interaction modes [13].

Molecular Interaction Parameters Explained

- Cavity Term (vV): Quantifies the energy required to separate solvent molecules to create a cavity for the solute; dominated by solvent cohesiveness often expressed through its Hildebrand solubility parameter [13]

- Dipole-Dipole/Polarizability Interactions (eE + sS): Measure the exothermic effects of solute-solvent dipole-dipole and dipole-induced dipole interactions

- Hydrogen Bonding (aA + bB): Accounts for the complementary hydrogen-bond donor (HBD) acidity and hydrogen-bond acceptor (HBA) basicity between solute and solvent

This five-parameter approach provides a comprehensive picture of intermolecular forces that goes far beyond the traditional "like dissolves like" heuristic [13]. For green chemistry applications, the power of LSER lies in its ability to predictively match solvents to specific molecular tasks while avoiding environmentally problematic options.

Experimental Protocols: Implementing LSER in Solvent Selection

Protocol 1: Determining Solvation Parameters for New Solvents

For solvents not yet characterized in LSER databases, particularly novel bio-based or "neoteric" solvents, this protocol establishes their solvation parameters experimentally.

Materials and Reagents

- Solvent of interest (high purity, ≥99%)

- Solvatochromic probe set: Reichardt's dye (Betaine 30), 4-nitroanisole, N,N-diethyl-4-nitroaniline, 4-nitrophenol, and toluene

- UV-vis spectrophotometer with temperature control

- 1-cm quartz cuvettes

- Analytical balance (precision ±0.0001 g)

- Temperature-controlled bath (±0.1°C)

Procedure

- Prepare solutions of each solvatochromic probe at concentrations yielding absorbances between 0.1-1.5 AU in the solvent of interest

- Measure UV-vis spectra of each solution in triplicate at 25.0°C ± 0.1°C

- Record maximum absorption wavelengths (λmax) for each probe with precision ±0.1 nm

- Calculate solvent parameters using established equations:

- π* (dipolarity/polarizability) from normalized N,N-diethyl-4-nitroaniline wavelength shift

- α (HBD acidity) from bathochromic shift of 4-nitrophenol versus reference solvent

- β (HBA basicity) from hypsochromic shift of 4-nitroanisole

- ET(30) and ETN from Reichardt's dye λmax

- Determine Vx (McGowan volume) using group contribution methods

Data Analysis Compute parameters through multiparameter linear regression against established solvent scales. Validate results by comparing measured values for known solvents (water, methanol, acetonitrile) with literature values (deviation should be <5%).

Protocol 2: LSER-Based Solvent Screening for API Crystallization

This protocol applies LSER principles to identify green solvent alternatives for active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) crystallization processes.

Materials and Reagents

- API (characterized crystalline form)

- Candidate solvent set representing diverse LSER parameter space

- CHEM21-rated solvents focusing on "recommended" and "problematic" categories [14]

- Robotic liquid handling system (optional)

- HPLC with photodiode array detector

- Analytical balance (precision ±0.0001 g)

- Thermal platform with agitation

Procedure

- Pre-select solvents spanning diverse LSER parameter space while prioritizing CHEM21 "recommended" solvents [14]

- Prepare saturated solutions of API in each solvent at 5°C and 50°C using shake-flask method

- Equilibrate for 24 hours with agitation, then filter (0.45 μm)

- Quantify solubility by HPLC with UV detection at λmax of API

- Characterize crystal form of residual solid by XRPD to confirm polymorphic stability

- Measure crystallization yield, purity, and crystal habit for promising solvents

Data Analysis

- Construct LSER model: logS = c + eE + sS + aA + bB + vV

- Identify dominant solubility mechanisms from coefficient magnitudes

- Rank solvents by combining solubility performance and green metrics

- Select lead candidates balancing high solubility, strong temperature coefficient, and green characteristics

Application to Green Chemistry: Integrating LSER with Sustainability Metrics

The true power of LSER emerges when molecular understanding is combined with comprehensive sustainability assessment. GreenSOL, the first comprehensive solvent selection guide specifically for analytical chemistry, employs a life cycle approach evaluating solvents across their production, laboratory use, and waste phases [15]. Each phase is evaluated against multiple impact categories, with solvents assigned individual impact category scores and a composite score on a scale of 1 (least favorable) to 10 (most recommended) [15].

Table 1: LSER Parameters and Green Metrics for Selected Solvents

| Solvent | π* | α | β | Vx | GreenSOL Score | CHEM21 Category | Circular Economy Potential |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water | 1.09 | 1.17 | 0.47 | 0.167 | 9 | Recommended | High (biodegradable) |

| Ethanol | 0.54 | 0.86 | 0.75 | 0.449 | 8 | Recommended | High (bio-based, biodegradable) |

| 2-MeTHF | 0.58 | 0.00 | 0.76 | 0.627 | 7 | Recommended | Medium (bio-based) |

| Cyclopentyl methyl ether | 0.40 | 0.00 | 0.58 | 0.771 | 7 | Recommended | Medium (low waste) |

| Acetonitrile | 0.75 | 0.19 | 0.40 | 0.404 | 5 | Problematic | Low (energy-intensive recycling) |

| N,N-Dimethylformamide | 0.88 | 0.00 | 0.69 | 0.550 | 3 | Hazardous | Low (reprotoxic, difficult waste treatment) |

| Dichloromethane | 0.82 | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.494 | 2 | Hazardous | Low (atmospheric emissions, ozone depletion) |

The integration of LSER parameters with green metrics enables rational substitution strategies. For example, if a process requires a solvent with high dipolarity (π* > 0.8) and HBA basicity (β > 0.6) but currently uses the hazardous solvent N,N-dimethylformamide, the LSER approach can identify 2-MeTHF (β = 0.76) or cyclopentyl methyl ether (β = 0.58) as potentially viable alternatives despite their lower π* values, particularly when used in binary mixtures [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for LSER and Green Solvent Applications

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Reichardt's Dye (Betaine 30) | Polarity probe for ET(30) determination | Light-sensitive; measure λmax in target solvents |

| 4-Nitroanisole | Hydrogen-bond acceptor basicity probe | Correlates with β parameter; stable crystalline solid |

| N,N-Diethyl-4-nitroaniline | Dipolarity/polarizability probe | Measures π* parameter; store in amber vials |

| 4-Nitrophenol | Hydrogen-bond donor acidity probe | Determines α parameter; handle in well-ventilated area |

| HPLC Reference Standards | Solubility determination | High-purity API characterization for solubility studies |

| CHEM21 Solvent Selection Guide | EHS assessment framework | Categorizes solvents as Recommended/Problematic/Hazardous [14] |

| GreenSOL Web Application | Lifecycle assessment tool | Interactive platform for solvent greenness evaluation [15] |

Workflow Integration: Implementing LSER in Pharmaceutical Development

The application of LSER methodology aligns with the circular economy framework now being adopted in pharmaceutical operations, which emphasizes resource efficiency, waste minimization, and material regeneration [12]. A systematic workflow ensures effective implementation:

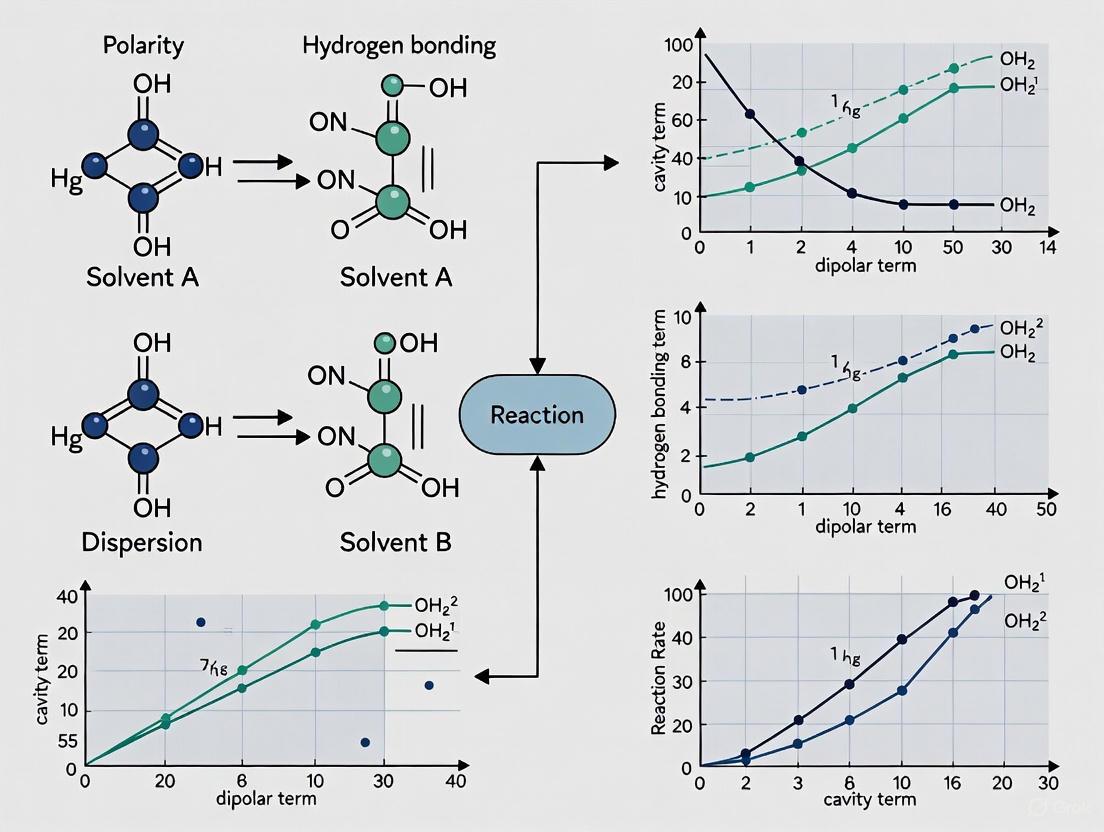

Figure 1: LSER-driven solvent selection workflow integrating molecular understanding with green chemistry principles.

This integrated approach enables pharmaceutical developers to transition from traditional solvents like dichloromethane (DCM) and N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) toward bio-based alternatives such as 2-methyltetrahydrofuran (2-MeTHF) and cyclopentyl methyl ether (CPME) with similar LSER profiles but superior environmental, health, and safety characteristics [16]. The workflow emphasizes the importance of considering the entire solvent lifecycle—from production through use to waste treatment—when making selection decisions [15].

The LSER methodology provides the theoretical foundation for rational solvent selection that aligns molecular-level understanding with green chemistry goals. By quantifying the specific intermolecular interactions governing solvation, researchers can move beyond trial-and-error approaches to make predictive, knowledge-driven decisions about solvent substitution and process optimization. When integrated with comprehensive sustainability assessment tools like the CHEM21 Guide and GreenSOL, LSER becomes a powerful instrument for advancing the circular economy in pharmaceutical development and chemical manufacturing. The protocols and workflows presented in this application note offer practical implementation strategies for researchers committed to reducing the environmental impact of solvent use while maintaining process efficiency and product quality.

The selection of appropriate solvents is a critical determinant of efficiency, safety, and environmental impact in chemical research and industrial processes. Within the context of green chemistry, this selection moves beyond mere solvation ability to encompass a holistic consideration of environmental, health, and safety (EHS) criteria alongside fundamental physicochemical properties [13]. The Linear Solvation Energy Relationship (LSER) framework provides a robust quantitative model for understanding how solvent properties—specifically polarity, hydrogen bonding, and polarizability—govern solute-solvent interactions and process outcomes. This Application Note delineates these key solvent properties and provides validated protocols for their application within green chemistry research, particularly for pharmaceutical and drug development professionals seeking to align their methodologies with sustainable principles.

Key Solvent Properties and Their Quantitative Descriptors

The following properties form the cornerstone of rational solvent selection within the LSER framework, allowing for the prediction of solvation behavior based on solvent descriptors.

Polarity and Dipolarity/Polarizability (π*)

Polarity is a composite term representing a solvent's overall ability to stabilize charges through nonspecific dielectric interactions. In LSER, this is often deconstructed into dipolarity (the ability to orient a permanent dipole) and polarizability (the ability to form an induced dipole) [17]. The Kamlet-Taft parameter ( \pi^* ) quantifies this combined dipolarity/polarizability effect on a dimensionless scale, typically ranging from 0.0 for non-polar solvents like cyclohexane to about 1.0 for highly dipolar solvents like dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) [17]. Ionic liquids, for instance, exhibit notably high ( \pi^* ) values, generally between 0.8 and 1.2 [17]. The polarity of a solvent directly influences reaction rates, as dramatically illustrated by the Menshutkin reaction, where activation barriers can vary by over 20 kcal/mol across different solvents [18].

Hydrogen Bonding (α and β)

Hydrogen bonding capacity is a specific and directional interaction that significantly impacts solubility and reactivity. It is characterized by two distinct Kamlet-Taft parameters:

- Hydrogen Bond Donor (HBD) acidity (α): This measures a solvent's ability to donate a proton in a hydrogen bond. Values range from 0.0 for non-donors to about 1.2 for strong donors like water [17].

- Hydrogen Bond Acceptor (HBA) basicity (β): This measures a solvent's ability to accept a proton in a hydrogen bond. Values range from 0.0 for non-acceptors to approximately 1.0 for strong acceptors like hexamethylphosphoramide (HMPA) [17].

Understanding the complementary HBD and HBA character of solvent mixtures allows for the fine-tuning of solvent environments, potentially enabling the replacement of hazardous dipolar aprotic solvents with safer HBD-HBA pairs [17].

Polarizability

Polarizability refers to the ease with which a solvent's electron cloud can be distorted, leading to the formation of a transient dipole. This property governs non-specific, dispersive interactions (van der Waals forces) [13]. While often incorporated into the ( \pi^* ) parameter, its individual role is crucial, especially in low-dielectric media. The importance of explicitly accounting for polarizability is highlighted by computational studies on the Menshutkin reaction, which show that non-polarizable force fields significantly overestimate activation barriers in non-polar solvents like cyclohexane and CCl₄ [18]. Incorporating a polarizable model was essential to accurately capture the stabilization of the highly dipolar transition state.

Table 1: Kamlet-Taft Solvatochromic Parameters for Common Solvents

| Solvent | π* (Dipolarity/Polarizability) | α (HBD Acidity) | β (HBA Basicity) | ε (Dielectric Constant) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water | ~1.09 | 1.17 | 0.47 | 80.1 |

| DMSO | ~1.00 | 0.00 | 0.76 | 46.7 |

| Acetonitrile | ~0.75 | 0.19 | 0.40 | 37.5 |

| Methanol | ~0.60 | 0.93 | 0.62 | 32.7 |

| THF | ~0.58 | 0.00 | 0.55 | 7.58 |

| Acetone | ~0.62 | 0.08 | 0.48 | 20.7 |

| CCl₄ | ~0.28 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 2.24 |

| Cyclohexane | ~0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.02 |

Note: Values are representative; actual measurements can vary between sources. Data synthesized from [18] [17].

Green Solvent Selection Frameworks and Tools

Integrating the physicochemical properties described above with environmental and safety considerations is the essence of modern green solvent selection.

The CHEM21 Selection Guide

The CHEM21 guide is a prominent tool that ranks solvents based on safety, health, and environmental impact into three categories: Recommended, Problematic, and Hazardous [14]. Its scoring is aligned with the Globally Harmonized System (GHS) and utilizes data from REACH dossiers.

- Safety Score: Derived from properties like flash point, boiling point, auto-ignition temperature, and peroxide-forming tendency [14].

- Health Score: Based on GHS classification and exposure limits, with adjustments for low-boiling solvents (<85°C) that pose higher inhalation risks [14].

- Environmental Score: Considers aquatic toxicity, biodegradability, and potential for bioaccumulation, often correlated with boiling point [14].

ACS GCI Solvent Selection Tool

The American Chemical Society Green Chemistry Institute's Pharmaceutical Roundtable provides an interactive Solvent Selection Tool based on Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of 70 physical properties for 272 solvents [7]. This tool visually maps solvents based on similarity of properties, allowing users to select or exclude solvents based on functional groups and review key data including ICH solvent classes, life-cycle assessment, and plant accommodation factors (e.g., flash point, VOC potential) [7].

Table 2: CHEM21 Environmental, Health, and Safety (EHS) Scoring Criteria

| Category | Assessment Criteria | Impact on Score |

|---|---|---|

| Safety | Flash Point | Lower flash point increases score (more hazardous) |

| Boiling Point | Very low or very high BP increases score | |

| Auto-ignition Temperature | <200°C adds points | |

| Peroxide Formation | Ability to form peroxides adds points | |

| Health | GHS Hazard Statements | Assigned score based on toxicity classifications |

| Boiling Point <85°C | Adds 1 point (increased volatility risk) | |

| Environment | Aquatic Toxicity (GHS) | H400, H410, H411 lead to a score of 7 |

| Boiling Point | <50°C or >200°C leads to a score of 7 |

Data derived from [14].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining Kamlet-Taft Parameters via Solvatochromic Probe Dyes

Principle: Kamlet-Taft parameters (π*, α, β) are experimentally determined by measuring the spectral shifts of various dye molecules dissolved in the solvent of interest. The energy of the absorption maximum correlates with the solvent's polarity and hydrogen-bonding capacity.

Materials:

- Reichardt's Dye (Betaine 30): For the ET(30) polarity scale, influenced by both polarity and HBD acidity.

- 4-Nitroanisole: Primary probe for π*.

- 4-Nitroaniline: Used in combination with 4-nitroanisole to calculate β.

- Diethyl-4-nitroaniline: Used to calculate π*.

Procedure:

- Prepare stock solutions of each probe dye in a range of 15-20 solvents of known Kamlet-Taft parameters for calibration.

- Prepare solutions of the probes in the test solvent at a concentration that yields absorbance values between 0.2 and 1.0 AU.

- Record UV-Vis absorption spectra for each solution in a 1 cm quartz cuvette.

- Determine the wavelength of maximum absorption (λ_max, in nm) for each probe in each solvent.

- Convert λmax to transition energy in kcal/mol: ( E = 28591 / \lambda{max} ).

- Calculation:

- ( \pi^* ) is calculated from the spectral shift of 4-nitroanisole or, more accurately, from the difference between the E values of 4-nitroanisole and diethyl-4-nitroaniline.

- ( \beta ) is calculated from the spectral shift of 4-nitroaniline relative to the shift of 4-nitroanisole, which corrects for dipolarity effects.

- ( \alpha ) is calculated from the spectral shift of Reichardt's dye, corrected for the solvent's π* and β contributions: ( \alpha = (E_T(30) - 14.6(\pi^* - 0.23) - 15.3) / 16.5 ).

Protocol 2: Computational Prediction of Solvent Effects on Reaction Kinetics

Principle: This protocol uses QM/MM (Quantum Mechanics/Molecular Mechanics) simulations to predict the effect of solvent on activation free energy (ΔG‡), using the Menshutkin reaction as a model.

Materials:

- Software: Gaussian 03 (or similar) for gas-phase QM calculations; BOSS or similar for QM/MM Monte Carlo simulations.

- Force Fields: OPLS (non-polarizable) or OPLS-AAP (polarizable) for common solvents.

- QM Method: PDDG/PM3 semiempirical method or B3LYP/MIDI! for higher accuracy.

Procedure:

- Gas-Phase Optimization: Optimize the geometry of the reactants and the transition state (TS) at the B3LYP/MIDI! theory level. Perform frequency calculations to confirm the TS (one imaginary frequency) and obtain gas-phase thermal corrections.

- System Setup: Create a periodic simulation box containing one molecule of the solute (e.g., triethylamine and ethyl iodide) and ~395 solvent molecules (or ~740 for water).

- QM/MM Simulation: Perform a two-dimensional free-energy perturbation (FEP) calculation using Monte Carlo (MC) sampling.

- Use the forming C-N bond distance (RCN) and the breaking C-I bond distance (RCI) as reaction coordinates.

- For each FEP window, run 5 million configurations for equilibration followed by 10 million configurations for averaging.

- The QM energy and atomic charges (e.g., CM3 charges) of the solute are recalculated for every attempted solute move.

- Data Analysis:

- Construct a 2D free-energy surface from the FEP data.

- Locate the transition state saddle point on this surface.

- The difference in free energy between the reactant state and the transition state gives the activation free energy, ΔG‡.

- Validation: Compare computed ΔG‡ values with experimental kinetic data across multiple solvents (e.g., cyclohexane, THF, DMSO, water) to validate the methodology. The use of a polarizable force field (OPLS-AAP) is critical for accurate results in low-dielectric media [18].

Protocol 3: Application of the ACS GCI Solvent Selection Tool for Green Solvent Replacement

Principle: This practical protocol uses the ACS GCI Solvent Selection Tool to identify greener alternatives to a given solvent based on property similarity and improved EHS profile.

Procedure:

- Access the Tool: Navigate to the ACS GCI PR Solvent Selection Tool online [7].

- Input Current Solvent: Use the search function to select the solvent you wish to replace.

- Define Constraints: Apply filters based on your process requirements:

- Functional Group Compatibility: Exclude solvents with functional groups that are incompatible with your chemistry.

- ICH Class: Prioritize Class 3 (low risk) over Class 2 or 1.

- Physical Properties: Set acceptable ranges for boiling point, flash point, and viscosity as needed for your process.

- Identify Alternatives: The tool's PCA map will display solvents with similar physicochemical properties. Visually identify candidate solvents that are "close" to your original solvent on the map but have a better EHS profile (as indicated by the color-coding for health, air, and water impact).

- Evaluate and Select: For the top candidates, review the detailed data sheets provided in the tool. Pay close attention to the environmental impact categories and life-cycle assessment data. Cross-reference with the CHEM21 guide to confirm their "Recommended" status [14].

- Experimental Validation: Test the performance of the top 2-3 candidate solvents in your specific reaction or process at a small scale to confirm suitability before full adoption.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Solvent Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Application in Protocols |

|---|---|---|

| Reichardt's Dye (Betaine 30) | Solvatochromic probe with intense polarity-dependent color change. | Protocol 1: Determination of ET(30) and Kamlet-Taft α parameter. |

| 4-Nitroanisole | Solvatochromic probe sensitive to dipolarity/polarizability. | Protocol 1: Used in conjunction with other probes to determine Kamlet-Taft π* and β parameters. |

| 4-Nitroaniline | Solvatochromic probe sensitive to hydrogen bond acceptor (HBA) basicity. | Protocol 1: Used to determine Kamlet-Taft β parameter. |

| OPLS/OPLS-AAP Force Field | A suite of molecular mechanics parameters for simulating organic liquids and biomolecules. OPLS-AAP includes explicit polarizability. | Protocol 2: Provides the MM component for QM/MM simulations, critical for accurate solvation free energies. |

| PDDG/PM3 Semiempirical Hamiltonian | A fast, parameterized quantum mechanical method optimized for accurate thermochemistry. | Protocol 2: Serves as the QM component in on-the-fly QM/MM calculations, enabling free-energy calculations for large systems. |

| ACS GCI Solvent Selection Tool | An interactive software tool for selecting solvents based on PCA of physical properties and EHS data. | Protocol 3: The primary platform for identifying greener solvent alternatives based on multi-criteria decision-making. |

Workflow and Decision Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for rational solvent selection, combining experimental and computational approaches within a green chemistry framework.

Solvent Selection Workflow Diagram. This chart outlines a systematic pathway for selecting optimal green solvents, integrating the LSER analysis, computational modeling, and experimental validation within a holistic EHS assessment framework.

Driven by environmental legislation and the principles of green chemistry, the adoption of sustainable solvents has become a critical focus in chemical research and industry, particularly in pharmaceuticals [16]. Solvent selection guides are tools designed to help chemists reduce the use of the most hazardous solvents by providing a clear, comparative assessment of Environmental, Health, and Safety (EHS) profiles [16]. These guides transform complex hazard data into accessible rankings, enabling researchers to make informed decisions that minimize process toxicity, waste, and energy demand. This document details the protocols for using two major guides—the CHEM21 Selection Guide and the ACS GCI Pharmaceutical Roundtable Solvent Selection Tool—framed within a research context utilizing Linear Solvation Energy Relationships (LSER) for deeper solvent property analysis. Their methodologies, from scoring hazards to interactive selection, provide a structured path for integrating green chemistry into laboratory practice.

The CHEM21 Solvent Selection Guide: Protocol and Application

The CHEM21 Selection Guide was developed by an academic-industry consortium to provide a standardized ranking for classical and bio-derived solvents [19] [20]. Its protocol is based on easily available physical properties and Globally Harmonized System (GHS) hazard statements, allowing for a preliminary greenness assessment even for solvents with incomplete data [19] [21].

Step-by-Step Experimental Protocol for CHEM21 Solvent Ranking

Principle: The methodology assigns separate scores for Safety (S), Health (H), and Environment (E), each on a scale of 1 (lowest hazard) to 10 (highest hazard). These scores are combined to yield an overall solvent ranking [19].

Procedure:

- Data Collection: Gather the following data from the solvent's Safety Data Sheet (SDS) or reliable databases:

- Flash Point (°C): For safety assessment.

- Boiling Point (°C): For health and environmental assessments.

- GHS Hazard Statements: All H3xx (health) and H4xx (environment) codes.

- Additional Properties: Auto-ignition temperature (AIT), resistivity, and the ability to form peroxides (EUH019).

Safety (S) Score Assignment (Refer to Table 1):

- Assign a base score from 1 to 7 based on the flash point.

- Add +1 point for each of the following:

- AIT < 200 °C

- Resistivity > 10^8 ohm.m

- Presence of the EUH019 statement (ability to form peroxides).

- Example: Diethyl ether (Flash Point = -45 °C, AIT = 160 °C, high resistivity, EUH019 present) has a base score of 7. With three +1 additions, its final Safety Score is 10 [19].

Health (H) Score Assignment (Refer to Table 1):

- Assign a score of 2, 4, 6, 7, or 9 based on the most stringent GHS H3xx statement, considering categories for CMR (Carcinogen, Mutagen, Reprotoxic), STOT (Specific Target Organ Toxicity), acute toxicity, and irritation.

- Add +1 point if the solvent's boiling point is < 85 °C (increased inhalation risk).

- For solvents with no H3xx statements after full REACH registration, the score is 1. For newer solvents with incomplete data, the default score is 5 (BP ≥ 85 °C) or 6 (BP < 85 °C) [19].

Environment (E) Score Assignment (Refer to Table 1):

- The score is determined by the most stringent factor among boiling point (volatility) and GHS H4xx statements (aquatic toxicity).

- A score of 10 is assigned for substances with an EUH420 statement (ozone layer hazard) [19].

Overall Ranking (Refer to Table 1):

- Combine the S, H, and E scores according to the rules in Table 1 to determine the final classification: Recommended, Problematic, or Hazardous.

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for determining a solvent's ranking using the CHEM21 protocol:

CHEM21 Quantitative Scoring Criteria and Solvent Examples

Table 1: CHEM21 Scoring Criteria and Combination Rules [19]

| Score | Safety (Flash Point) | Health (Worst H3xx) | Environment (BP & H4xx) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | > 60 °C | No H3xx (full REACH) | - |

| 2-4 | 23-60 °C | H315, H319, etc. | - |

| 5-7 | -1 to -20 °C | H318, H336, etc. | BP <50°C or >200°C; H412, H413 |

| 8-10 | < -20 °C | H340, H350, H360 (CMR Cat 1) | H400, H410, H411; EUH420 |

| Final Ranking Rules |

|---|

| Recommended: All other score combinations. |

| Problematic: One score = 7 OR two "yellow" scores (4-6). |

| Hazardous: One score ≥ 8 OR two "red" scores (7-10). |

Table 2: Example Solvent Rankings from the CHEM21 Guide [19]

| Family | Solvent | BP (°C) | FP (°C) | S Score | H Score | E Score | Ranking |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohols | Methanol | 65 | 11 | 4 | 7 | 5 | Recommended* |

| Alcohols | Ethanol | 78 | 13 | 4 | 3 | 3 | Recommended |

| Ketones | Acetone | 56 | -18 | 5 | 3 | 5 | Recommended |

| Esters | Ethyl Acetate | 77 | -4 | 5 | 3 | 3 | Recommended |

| Halogenated | Dichloromethane | 40 | - | 7 | 6 | 7 | Hazardous |

| *Methanol was elevated to "Recommended" after expert discussion [19]. |

The ACS GCI Solvent Selection Tool: Protocol and Application

The ACS GCI Pharmaceutical Roundtable Solvent Selection Tool is an interactive software that facilitates solvent selection based on a multivariate analysis of physical properties and impact categories [7]. It moves beyond a simple ranking to enable function-based substitution.

Step-by-Step Experimental Protocol for Using the ACS Tool

Principle: The tool uses Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of 70 physical properties to map solvents based on their polarity, polarizability, and hydrogen-bonding ability. Solvents close to each other on the PCA map have similar properties and are potential substitutes [7].

Procedure:

- Access the Tool: Navigate to the online ACS GCI Solvent Selection Tool [7].

- Define Search Criteria:

- By Physical Properties: Input desired ranges for properties like boiling point, dipole moment, and solubility parameters to find solvents that match process requirements (e.g., distillation temperature or solvation power).

- By Functional Groups: Use the functional group filter to include or exclude solvents containing specific moieties (e.g., exclude chlorinated compounds) for compatibility with the reaction chemistry.

- By ICH Classification: Filter solvents based on the ICH Q3C guideline, which sets permissible limits for residual solvents in pharmaceuticals (Class 1: Solvents to be avoided; Class 2: Solvents to be limited; Class 3: Solvents with low toxic potential) [7].

- Analyze Impact Categories: For the filtered solvents, review and compare integrated data on:

- Health, Impact in Air, Impact in Water

- Life-Cycle Assessment (LCA) considerations.

- Plant Accommodation factors (e.g., viscosity, enthalpy of vaporization).

- Compare and Select: The tool displays solvents on a PCA plot. Identify a cluster of solvents with similar properties to your target solvent. Evaluate the greenest options within that cluster by comparing their impact category scores.

- Export Data (Optional): Export the filtered solvent data for further analysis in other software packages or for Design of Experiment (DoE) studies [7].

The workflow for a typical solvent replacement study using the ACS Tool is outlined below:

Integration with LSER Analysis and Advanced Frameworks

For thesis research focused on LSER analysis, these solvent guides provide an ideal experimental bridge. The Abraham solvation parameters, central to LSERs, quantitatively describe a solvent's capacity for specific intermolecular interactions (e.g., dipolarity, hydrogen-bond acidity/basibility) [22]. This directly complements the multi-parameter approach of the ACS GCI Tool.

Protocol: Correlating Guide Rankings with LSER Solvation Properties

- Select a Solvent Series: Choose a homologous series or a cluster of solvents from the ACS tool's PCA map (e.g., alcohols, esters).

- Obtain LSER Parameters: Compile the Abraham parameters for each solvent in the series from established databases.

- Plot Parameters vs. Ranking: Create scatter plots to visualize the relationship between individual LSER parameters (e.g., hydrogen-bond acidity) and the SHE scores from the CHEM21 guide.

- Statistical Analysis: Perform multivariate regression to determine which combination of solvation parameters best predicts a solvent's overall greenness ranking. This can reveal, for instance, if a high hydrogen-bond basicity is correlated with improved environmental scores in certain applications.

- Validate with Advanced Frameworks: Cross-reference findings with other quantitative frameworks. For example, the Hansen Solubility Parameters (HSP) have been successfully used for solvent selection in polymer analysis for MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry [23] and in Liquid-Phase Exfoliation (LPE) for nanomaterial production, where exfoliation and binding energies can be correlated with solvent properties like dipole moment and polarity [22].

Table 3: Essential Resources for Green Solvent Selection Research

| Tool / Resource | Type | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| CHEM21 Guide Methodology [19] | Scoring Framework | Provides a transparent, property-based protocol for SHE hazard assessment and ranking. |

| ACS GCI Solvent Tool [7] | Interactive Database | Enables solvent substitution based on physicochemical similarity and multi-criteria impact assessment. |

| Hansen Solubility Parameters (HSP) [23] | Theoretical Model | Predicts polymer solubility and nanomaterial dispersion; useful for selecting solvents in materials science. |

| Abraham Solvation Parameters | Theoretical Model | The core variables for LSER analysis, quantifying specific solvent-solute interactions. |

| Globally Harmonized System (GHS) | Regulatory Framework | Source of standardized hazard statements (H-phrases) for health and environmental scoring. |

| ICH Q3C Guideline | Regulatory Framework | Defines permitted daily exposure limits for residual solvents in pharmaceutical products. |

| First-Principles Calculations (DFT) [22] | Computational Method | Quantifies solvent-nanomaterial interactions (e.g., exfoliation energy, binding energy) for rational solvent design. |

The CHEM21 and ACS GCI solvent selection guides are foundational tools for implementing green chemistry principles. The CHEM21 guide offers a straightforward, hazard-based ranking system, while the ACS GCI tool provides a powerful, property-driven platform for solvent substitution. The detailed protocols outlined herein allow researchers to apply these guides systematically in the laboratory. Furthermore, integrating these tools with quantitative LSER analysis and advanced computational methods, such as the calculation of exfoliation energies in solvent selection for LPE [22], provides a robust and insightful research pathway. This synergy between practical guides and fundamental solvation theory is key to advancing the development of sustainable chemical processes.

Implementing LSER Analysis in Your Solvent Selection Workflow

A Step-by-Step Guide to Building and Interpreting LSER Models

Linear Solvation Energy Relationships (LSERs) are a powerful quantitative tool used to understand and predict the solvation properties of molecules based on their fundamental intermolecular interaction capabilities. The technique was pioneered by Abraham and coworkers and has become a cornerstone in green chemistry research and pharmaceutical development for rational solvent selection [24] [25]. The fundamental Abraham LSER model describes solvation processes using a multiparameter linear equation that correlates a free-energy related property of a solute with its molecular descriptors [24] [26].

The most widely accepted symbolic representation of the LSER model is given by the equation:

SP = c + eE + sS + aA + bB + vV

In this equation, SP represents any free energy-related property. In chromatography, this is most often the log of the retention factor (log k'), while in solvent selection for green chemistry, it can represent reaction rate constants or partition coefficients [24] [25]. The lowercase coefficients (e, s, a, b, v) are system descriptors that characterize the solvent system or separation medium, while the uppercase variables (E, S, A, B, V) are solute descriptors that capture the molecule's ability to participate in different types of intermolecular interactions [24] [10].

Theoretical Foundation and Molecular Interactions

The LSER model successfully quantifies the balance between exoergic solute-solvent attractive forces and endoergic cavity formation and solvent reorganization processes that occur during solvation [24]. The gas-liquid partition process is modeled as the sum of these competing effects, while the partitioning of a solute between two solvents is thermodynamically equivalent to the difference in two gas/liquid solution processes [24].

The solute parameters represent the following molecular characteristics:

- E represents the solute's excess molar refractivity, which is related to its polarizability [24] [10].

- S represents the solute's dipolarity/polarizability [24] [10].

- A characterizes the solute's hydrogen bond donating ability (acidity) [24] [10].

- B characterizes the solute's hydrogen bond accepting ability (basicity) [24] [10].

- V represents the solute's molecular size, typically characterized by McGowan's characteristic volume [10].

The system coefficients (e, s, a, b, v) reflect the complementary effect of the solvent phase on solute-solvent interactions. A positive coefficient indicates that the corresponding interaction increases the retention/partitioning/solvation, while a negative coefficient indicates a decrease [10]. The remarkable linearity of LSER equations, even for strong specific hydrogen bonding interactions, has been verified through equation-of-state thermodynamics combined with the statistical thermodynamics of hydrogen bonding [10].

Experimental Protocol for LSER Model Development

Phase 1: Research Design and Data Collection

Step 1: Define Research Objective and System Property (SP)

- Clearly identify the solvation-related property to be modeled (e.g., partition coefficient, chromatographic retention, reaction rate constant).

- For solvent selection in green chemistry, the partition coefficient between water and an organic solvent or reaction rate constants are commonly used as SP [25] [11].

Step 2: Select a Diverse Set of Solute Probes

- Choose 30-40 compounds that span a wide range of interaction abilities [24].

- Ensure coverage of varied hydrogen bonding capabilities, polarizabilities, dipolarities, and molecular sizes.

- Prefer solutes with known Abraham parameters from established databases.

Step 3: Experimental Measurement of System Property

- For partition coefficients: Use shake-flask or HPLC methods with precise concentration measurements.

- For reaction kinetics: Monitor reaction progress via NMR, GC, or HPLC to determine rate constants [25].

- Maintain constant temperature (±0.1°C) throughout experiments.

- Perform replicates (n≥3) to ensure measurement precision.

Phase 2: Data Analysis and Model Building

Step 4: Data Compilation Compile experimental data and solute parameters into a structured table:

Table 1: Example Data Structure for LSER Modeling

| Solute | E | S | A | B | V | SP (experimental) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solute 1 | ||||||

| Solute 2 | ||||||

| ... |

Step 5: Multiple Linear Regression Analysis

- Use statistical software (R, Python, or specialized LSER tools) to perform multiple linear regression.

- Apply the equation: SP = c + eE + sS + aA + bB + vV

- Validate regression assumptions: linearity, normality of residuals, homoscedasticity.

Step 6: Model Validation

- Use leave-one-out cross-validation or an independent test set (recommended: 70:30 split) [11].

- Evaluate using R², adjusted R², root mean square error (RMSE), and prediction error.

- For reliable models, target R² > 0.9 and RMSE < 0.3 for log-based properties [11].

Phase 3: Model Interpretation and Application

Step 7: Chemical Interpretation of Coefficients

- Interpret the magnitude and sign of system coefficients to understand interaction patterns.

- Compare with known systems to identify similar interaction profiles.

Step 8: Application to Solvent Selection

- Use the established model to predict properties of new solutes.

- Apply for green solvent selection based on predicted performance and environmental metrics.

LSER Workflow Visualization

Molecular Interactions in LSER

Essential LSER Parameters and Solute Descriptors

Table 2: Abraham Solute Descriptors and Their Interpretation

| Descriptor | Molecular Property | Measurement Basis | Typical Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| E | Excess molar refractivity, polarizability | Measured from refractive index, related to π- and n-electron interactions | -0.4 to 3.5 |

| S | Dipolarity/polarizability | Solvatochromic comparison method using indicator dyes | 0 to 2.0 |

| A | Hydrogen bond acidity (donating ability) | Measured from partition coefficients or solubility data | 0 to 1.2 |

| B | Hydrogen bond basicity (accepting ability) | Measured from partition coefficients or solubility data | 0 to 1.4 |

| V | Molecular size | McGowan's characteristic volume in cm³/100 | 0.1 to 4.0 |

Table 3: System Coefficients and Their Chemical Meaning

| Coefficient | Chemical Interpretation | Positive Value Indicates | Negative Value Indicates |

|---|---|---|---|

| e | Ability to engage in polarizability interactions | Phase favors interaction with polarizable solutes | Phase disfavors interaction with polarizable solutes |

| s | Dipolarity/polarizability character | Phase favors interaction with polar solutes | Phase disfavors interaction with polar solutes |

| a | Hydrogen bond basicity (complement to solute acidity) | Phase is a good H-bond acceptor | Phase is a poor H-bond acceptor |

| b | Hydrogen bond acidity (complement to solute basicity) | Phase is a good H-bond donor | Phase is a poor H-bond donor |

| v | Cavity formation term related to cohesion | Larger solutes are favored (uncommon) | Larger solutes are disfavored (common) |

Table 4: Key Resources for LSER Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Solute Parameter Databases | Abraham Solute Parameter Database, UFZ-LSER Database | Provide established solute descriptors (E, S, A, B, V) for known compounds |

| QSPR Prediction Tools | ACD/Labs, DRAGON, Open-source QSPR tools | Predict Abraham parameters for novel compounds using structural features |

| Statistical Software | R with lm() function, Python with scikit-learn, MATLAB | Perform multiple linear regression analysis for LSER model development |

| Solvent Selection Guides | CHEM21 Solvent Selection Guide, ACS GCI Pharmaceutical Roundtable tool | Evaluate greenness of solvents based on safety, health, and environment (SHE) criteria [25] [27] |

| Specialized LSER Software | SUSSOL (Sustainable Solvents Software) | AI-powered tool for solvent selection and substitution using LSER principles [27] |

Case Study: LSER for Green Solvent Selection in Pharmaceutical Chemistry

A recent application demonstrates how LSER can guide greener solvent choices in pharmaceutical development [25]. Researchers studied the aza-Michael addition between dimethyl itaconate and piperidine, developing the following LSER model for the reaction rate constant in different solvents:

ln(k) = -12.1 + 3.1β + 4.2π*

This model revealed that the reaction was accelerated by polar, hydrogen bond accepting solvents (positive coefficients with both β and π* parameters) [25]. The positive correlation with β reflects stabilization of proton transfer, while polar or polarizable solvents stabilize charge delocalization in the activated complex.

Using this LSER model, researchers could:

- Predict performance of untested solvents

- Identify greener alternatives to problematic solvents like DMF

- Optimize reaction conditions based on understanding of molecular interactions

The model facilitated solvent selection considering both reaction efficiency and environmental impact, aligning with green chemistry principles [25].

Advanced Applications and Recent Developments

LSER methodology continues to evolve with several advanced applications:

Polymer-Water Partitioning: LSER models have been successfully developed for predicting partition coefficients between low-density polyethylene (LDPE) and water, with excellent predictive capability (R² = 0.991, RMSE = 0.264) [11]. The model: log K~i,LDPE/W~ = -0.529 + 1.098E - 1.557S - 2.991A - 4.617B + 3.886V

This application is particularly valuable for predicting the leaching of compounds from plastic packaging in pharmaceutical products [11].

AI-Enhanced Solvent Selection: Artificial Intelligence approaches are being integrated with LSER principles through tools like SUSSOL (Sustainable Solvents Selection and Substitution Software) [27]. These tools use neural networks to cluster solvents based on physical properties, enabling data-driven identification of greener alternatives while considering safety, health, and environmental criteria.

Partial Solvation Parameters (PSP): Recent work integrates LSER with equation-of-state thermodynamics through Partial Solvation Parameters, facilitating extraction of thermodynamic information from LSER databases for broader applications in molecular thermodynamics [10].

Troubleshooting and Quality Control

Common Issues and Solutions:

- Poor Model Statistics: Ensure solute set spans sufficient chemical space with varied interaction capabilities [24].

- Collinearity Between Descriptors: Check variance inflation factors (VIF); remove or combine descriptors if VIF > 5-10.

- Non-Linearity: Transform variables or consider additional interaction terms in the model.

- Insufficient Data: Include at least 5-6 solutes per descriptor in the model; recommended minimum of 30 solutes total.

Quality Control Metrics:

- R² > 0.9 for reliable models in homogenous datasets

- RMSE < 0.3 for log-based properties indicating good predictive ability

- Leave-one-out Q² > 0.7 indicating good model robustness

- External validation with independent test set (recommended 25-33% of data)

When properly constructed and validated, LSER models provide powerful tools for understanding solvation phenomena, predicting partition behavior, and guiding the selection of greener solvents in pharmaceutical development and other chemical industries.

The selection of extraction solvents is a critical determinant of efficiency, environmental impact, and regulatory compliance in pharmaceutical manufacturing. Conventional solvents like chloroform and benzene are volatile, toxic, and pose significant environmental and occupational hazards [28]. The industry is consequently undergoing a paradigm shift toward green chemistry principles, adopting sustainable solvents that minimize toxicity and ecological footprint without compromising analytical performance [29] [28]. This case study explores the replacement of problematic conventional solvents with Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents (NADES) for the extraction and analysis of metal ions from botanical samples. The methodology is framed within a broader research context employing Linear Solvation Energy Relationship (LSER) analysis for rational, predictive solvent selection, aligning with green chemistry objectives.

Theoretical Background and Solvent Selection Framework

Principles of Green Solvent Selection

Ideal green solvents are characterized by low toxicity, high biodegradability, minimal volatility, and sustainable production from renewable resources [28]. Their selection is guided by the 12 Principles of Green Chemistry, which advocate for waste reduction, energy efficiency, and the use of safer substances [28]. Frameworks like the GSK Sustainable Solvent Framework and lifecycle assessment (LCA) indicators (e.g., ReCiPe 2016) provide multidimensional metrics for comparing solvent sustainability, evaluating factors from carbon footprint to biodegradability [30].

The Role of LSER Analysis

Linear Solvation Energy Relationships (LSER) provide a quantitative computational model for understanding and predicting how a solvent's chemical properties will interact with specific solutes. In the context of green chemistry, LSER analysis moves solvent selection beyond empiricism towards a rational, predictive approach. By analyzing parameters such as polarity, hydrogen-bonding acidity/basicity, and polarizability, researchers can screen potential green solvents in silico to identify candidates with the optimal solvation environment for a target analyte, thereby reducing the need for extensive laboratory trial-and-error.

Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents (NADES)

NADES are a class of green solvents formed by mixing hydrogen bond donors (HBD) and hydrogen bond acceptors (HBA) from natural sources, such as organic acids, sugars, or amino acids [31] [29]. They are green solvents with several advantageous properties:

- Low toxicity and high biodegradability [31] [28].

- Low volatility and non-flammability, enhancing workplace safety [28].

- Tunable physicochemical properties by altering the HBD/HBA components and their ratios, making them highly adaptable for specific extraction needs [31] [29]. This tunability is a key focus for LSER modeling.

Table 1: Comparison of Conventional and Green Solvents

| Property | Conventional Solvents (e.g., Chloroform) | Green Solvents (e.g., NADES) |

|---|---|---|

| Toxicity | High | Low |

| Biodegradability | Low | High |

| Vapor Pressure | High | Negligible |

| Source | Petroleum-based | Renewable, bio-based |

| Tunability | Limited | High |

| Environmental Impact | Significant | Minimal |

Case Study: NADES for Metal Ion Extraction from Plant Materials

This case study details the use of a hydrophobic NADES composed of DL-menthol and palmitic acid for the extraction, preconcentration, and analysis of metal ions (e.g., Cu, Cd, Pb, Mg, Mn, Ca, Zn) from vegetable materials and water samples [31]. The method combines Dispersive Liquid-Liquid Microextraction (DLLME) with Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS) detection, showcasing a integrated green analytical approach.

Experimental Protocol

Protocol 1: Synthesis of Menthol-Palmitic Acid NADES

- Materials: DL-Menthol (HBA), Palmitic Acid (HBD).

- Procedure:

- Weigh menthol and palmitic acid in a predetermined molar ratio.

- Mix the components in a vial and heat at ~50°C under continuous stirring until a homogeneous, clear liquid is formed.

- Confirm the formation of the NADES by its liquid state at the reaction temperature and its solidification upon cooling to room temperature.

Protocol 2: NADES-Based DLLME and LIBS Analysis

- Sample Preparation:

- Digest the vegetable material (e.g., green coffee, soy flour) using a standard acid digestion procedure to obtain an aqueous sample digest.

- Complexation:

- To the aqueous sample, add a complexing agent, 1-(2-pyridylazo)-2-naphthol (PAN), to form hydrophobic metal-PAN complexes. The amount used is minimal (5.4 mg per determination) [31].

- Microextraction:

- Add 2 mL of the synthesized NADES to the sample.

- Agitate the mixture using a vortex at a temperature above the melting point of the NADES (e.g., ~40-50°C) to achieve a dispersed phase.

- Centrifuge the mixture to separate the phases.

- Cool the system to room temperature. The NADES solidifies, forming a stable, solid disc containing the preconcentrated metal complexes.

- Analysis:

- Place the solid NADES disc directly into the LIBS instrument.

- Use the following optimized LIBS parameters for analysis [31]:

- Laser Energy: 100 mJ

- Lens-to-Sample Distance: 18.5 cm

- Delay Time: 4.0 μs

- Integration Time: 13.0 μs

- Number of Pulses: 180

- Quantification:

- Use external calibration curves prepared from standard metal solutions processed through the same DLLME-LIBS method.

Performance Data

The methodology demonstrated high performance, confirming the viability of NADES as both an extractor and a solid support [31].

Table 2: Analytical Performance of NADES-DLLME-LIBS for Metal Ion Determination

| Metal Ion | Linear Range (mg L⁻¹) | Limit of Detection (LOD, mg L⁻¹) | Preconcentration Factor | Recovery in Water Samples (%) | Recovery in Plant Materials (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mg, Mn, Cd | 0.1 - 3.0 | 0.1 | 22 | 78 - 128 | 94 - 122 |

| Ca, Zn | 0.2 - 3.0 | 0.2 | 22 | 78 - 128 | 94 - 122 |

| Pb | 0.4 - 3.0 | 0.4 | 22 | 78 - 128 | 94 - 122 |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for NADES-Based Extraction

| Reagent/Material | Function/Explanation |

|---|---|

| DL-Menthol | Hydrogen bond acceptor (HBA) component for forming hydrophobic NADES. |

| Palmitic Acid | Hydrogen bond donor (HBD) component for forming hydrophobic NADES. |

| PAN (1-(2-pyridylazo)-2-naphthol) | Complexing agent that chelates with metal ions to form hydrophobic complexes for extraction. |

| Hydrophobic NADES | Serves as the green extraction solvent and solid support for LIBS, replacing volatile organic solvents. |

| LIBS Instrumentation | Enables direct, rapid elemental analysis of the solid NADES disc with minimal sample preparation. |

Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

NADES Extraction & Analysis Workflow

LSER-Guided Solvent Selection