Linear Solvation Energy Relationships (LSER): A Comprehensive Guide to Predictive Solvent Selection in Research and Drug Development

This article provides a complete resource for researchers and drug development professionals on applying Linear Solvation Energy Relationships (LSER) for rational solvent selection.

Linear Solvation Energy Relationships (LSER): A Comprehensive Guide to Predictive Solvent Selection in Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a complete resource for researchers and drug development professionals on applying Linear Solvation Energy Relationships (LSER) for rational solvent selection. It covers the foundational principles of the Abraham solvation parameter model, detailing how solute descriptors (E, S, A, B, V) and system constants (e, s, a, b, v) quantitatively predict solvent effects. The content explores methodological applications in chromatography and pharmaceutical process development, offers troubleshooting for complex molecules and model limitations, and presents validation through thermodynamic interpretations and comparative analyses with other methods. By synthesizing theory and practice, this guide empowers scientists to leverage LSER for optimizing solvent use in chemical processes and pharmaceutical formulations.

Understanding LSER Fundamentals: The Abraham Model and Molecular Descriptors

Linear Solvation Energy Relationships (LSERs) are a powerful predictive tool in chemical, biomedical, and environmental research for understanding the intermolecular interactions that govern solute retention and partitioning in various processes [1] [2]. The most widely accepted model, known as the Abraham solvation parameter model, describes a solute's behavior in different phases or solvents using a multiparameter equation [1] [3]. This model is grounded in the cavity theory of solvation, which posits that solvation involves the creation of a cavity in the solvent, insertion of the solute, and subsequent solute-solvent interactions [3].

The core equation for describing solute transfer between two condensed phases (e.g., water and an organic solvent) is expressed as:

SP = c + eE + sS + aA + bB + vV

In this equation:

- SP is a solute property, which is a free-energy-related property. In chromatography, this is most often the logarithm of the retention factor, log k' [1]. For partitioning, it is commonly the logarithm of the water-to-organic solvent partition coefficient, log P [1] [3].

- The lowercase letters (e, s, a, b, v) are system coefficients (or solvent descriptors) that reflect the complementary properties of the solvent or phase system [1] [2] [3].

- The uppercase letters (E, S, A, B, V) are solute descriptors that capture the solute's ability to participate in various types of intermolecular interactions [1] [3].

- The constant c is a regression-derived constant for the system [3].

Table 1: Explanation of Terms in the Core LSER Equation

| Symbol | Type | Description | Physicochemical Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| SP | Solute Property | A free-energy-related property | Most often log k' (chromatography) or log P (partitioning) [1] |

| c | Constant | Regression-derived constant | System-specific intercept |

| e | Solvent Coefficient | Solvent's ability to interact with solute electron pairs | Measures interaction via pi- and non-bonding electrons [3] |

| E | Solute Descriptor | Solute's excess molar refraction | Related to the solute's polarizability [1] [3] |

| s | Solvent Coefficient | Solvent's dipolarity/polarizability | Measures interaction with dipolar solutes [1] |

| S | Solute Descriptor | Solute's dipolarity/polarizability | Measures the solute's ability to engage in dipole-dipole interactions [1] [3] |

| a | Solvent Coefficient | Solvent's hydrogen-bond basicity | Complementary to the solute's acidity [3] |

| A | Solute Descriptor | Solute's hydrogen-bond acidity | Measures the solute's ability to donate a hydrogen bond [1] [3] |

| b | Solvent Coefficient | Solvent's hydrogen-bond acidity | Complementary to the solute's basicity [3] |

| B | Solute Descriptor | Solute's hydrogen-bond basicity | Measures the solute's ability to accept a hydrogen bond [1] [3] |

| v | Solvent Coefficient | Solvent parameter related to cavity formation | Derived from regression, related to dispersion interactions [3] |

| V | Solute Descriptor | McGowan's characteristic volume (in cm³/100) | Represents the solute's molecular size, related to the endoergic cost of cavity formation [1] [2] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Determining Solute Descriptors from Experimental Data

This protocol outlines the method for determining the LSER descriptors (E, S, A, B, V) for a new solute, a prerequisite for applying the model predictively.

1. Principle Solute descriptors are determined by measuring the solute's behavior (e.g., partition coefficients, retention factors) in multiple, well-characterized solvent systems with known LSER coefficients (e, s, a, b, v). The descriptors are then solved via multiple linear regression [1].

2. Materials and Equipment

- Solute of interest (high purity)

- Reference solvents/systems with known LSER coefficients (e.g., n-hexadecane, water/octanol, chromatographic systems)

- Gas Chromatograph (GC) or High-Performance Liquid Chromatograph (HPLC)

- Partitioning experiment apparatus (e.g., shake-flask setup)

- UV-Vis Spectrophotometer or other analytical instrument for concentration determination

3. Step-by-Step Procedure Step 1: Select Reference Systems. Choose at least 5-6 different solvent systems (e.g., gas/solvent, water/solvent) for which the LSER coefficients (e, s, a, b, v, c) are reliably known from the literature [1]. Step 2: Measure Solute Property. For each reference system (i), experimentally determine the solute property (SP_i). For partitioning, this is log P; for chromatography, it is log k' [1]. Step 3: Regress Descriptors. Set up a system of equations using the core LSER model for each measurement: SP₁ = c₁ + e₁E + s₁S + a₁A + b₁B + v₁V SP₂ = c₂ + e₂E + s₂S + a₂A + b₂B + v₂V ... Step 4: Perform Regression. Use multiple linear regression analysis to solve for the five solute descriptors (E, S, A, B, V) that best fit the entire dataset of experimental SP values [1]. The statistical fit must be robust, and the descriptors should fall within reasonable chemical limits.

4. Data Analysis The resulting set of descriptors (E, S, A, B, V) for the solute can be stored in a database and used to predict the solute's behavior in any other system for which the LSER coefficients are known.

Protocol: Predicting Partition Coefficients (log P) for Solvent Screening

This protocol uses the Abraham model to predict the water-to-solvent partition coefficient (log P) for a solute, which is crucial for solvent screening in drug development, such as for liquid-liquid extractions.

1. Principle Once a solute's descriptors are known, its partition coefficient between water and any organic solvent can be predicted if the solvent's coefficients in the LSER equation for log P are known [3]. The model predicts the degree to which a solute will favor one phase over another.

2. Materials and Equipment

- UFZ-LSER database or other literature source for solute descriptors [4]

- Literature source for solvent coefficients (e, s, a, b, v, c) for the log P equation [3]

- Computational tool (spreadsheet software is sufficient)

3. Step-by-Step Procedure Step 1: Obtain Solute Descriptors. Retrieve the solute descriptors (E, S, A, B, V) for your compound of interest from a reliable database such as the UFZ-LSER database [4]. If unavailable, refer to Protocol 2.1. Step 2: Obtain Solvent Coefficients. Retrieve the solvent coefficients (c, e, s, a, b, v) for the log P equation for the solvents you wish to screen. These are typically found in peer-reviewed literature compilations [3]. Step 3: Apply the LSER Equation. For each solvent, calculate the predicted log P using the core equation: log P = c + eE + sS + aA + bB + vV Step 4: Compare Results. Rank the solvents based on the calculated log P value. A higher log P value indicates the solute has a greater affinity for that organic solvent over water [3].

4. Data Analysis The predicted log P values allow for the rational selection of solvents for extraction. For example, a higher log P for solvent A compared to solvent B suggests that solvent A will be more effective at extracting the solute from an aqueous phase [3].

Workflow Visualization

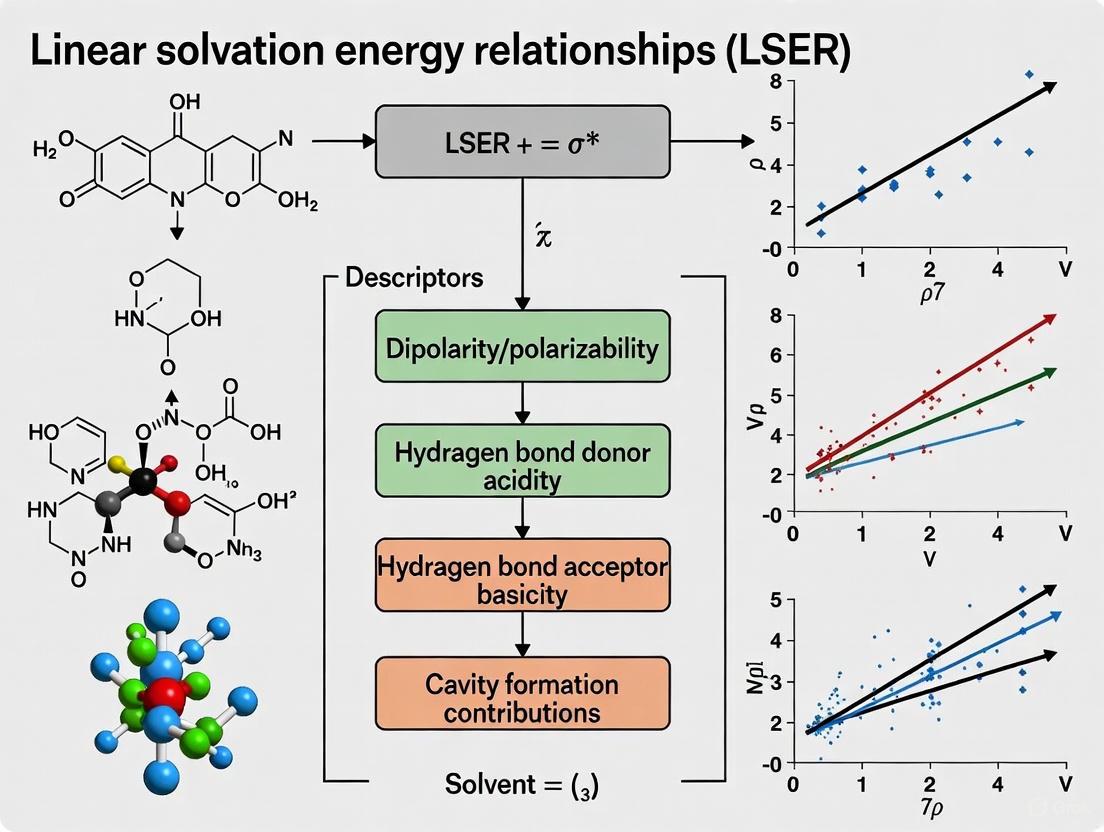

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for applying the LSER model to predict solute behavior, from descriptor determination to practical application.

Data Presentation

The predictive power of the LSER model is demonstrated by its ability to correlate and predict complex solvation properties. The following table provides a concrete example of how the model can be used to predict the extraction efficiency of caffeine from water into different organic solvents, a relevant process in pharmaceutical isolation [3].

Table 2: Example LSER Prediction for Caffeine Extraction from Water [3]

| Solvent | Predicted log P | Predicted Partition Coefficient (P) | Interpretation for Extraction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chloroform | 1.044 | 11.072 | Highest affinity for caffeine. Most efficient for extraction from water. |

| Ethanol | -0.005 | 0.989 | Nearly equal distribution between water and ethanol. Low extraction efficiency. |

| Cyclohexane | -1.808 | 0.016 | Very low affinity for caffeine. Caffeine will remain almost entirely in the water phase. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Successful application of the LSER model relies on specific tools and databases. This table lists essential resources for researchers.

Table 3: Essential Resources for LSER Research

| Resource | Type | Function in LSER Research |

|---|---|---|

| UFZ-LSER Database [4] | Database | A primary source for obtaining solute descriptors (E, S, A, B, V, L) for thousands of neutral compounds. |

| Reference Solvent Systems | Experimental | Systems like n-hexadecane/air, water/octanol, and specific GC/HPLC columns with known LSER coefficients, used to characterize new solutes (Protocol 2.1) [1]. |

| Chromatography System (GC/HPLC) | Equipment | Used to measure retention factors (log k') for solutes, which serve as the solute property (SP) for determining descriptors or validating predictions [1]. |

| Shake-Flask Apparatus | Equipment | Used for experimental determination of liquid-liquid partition coefficients (log P) for method validation [3]. |

| Abraham Solute Descriptors (E, S, A, B, V) | Data | The core set of parameters that characterize a solute's interaction potential. These are the key inputs for any predictive calculation [1] [3]. |

| LSER Solvent Coefficients (c, e, s, a, b, v) | Data | System-specific parameters that describe the solvent's or chromatographic system's interaction capabilities. Required to predict SP for a known solute [1] [2]. |

The Abraham solvation parameter model is a fundamental framework in physical chemistry that describes the transfer of solutes between phases using a set of system-independent descriptors. This model is grounded in Linear Solvation Energy Relationships (LSERs), which establish correlations between a solute's molecular properties and its behavior in various chemical and biological systems [5]. The general model is expressed through two primary equations for partition coefficients:

Log P = c + e·E + s·S + a·A + b·B + v·V [6] [5]

Log K = c + e·E + s·S + a·A + b·B + l·L [5]

where P represents water-solvent partition coefficients, K represents gas-solvent partition coefficients, and the lowercase letters (c, e, s, a, b, v, l) are system-specific coefficients that describe the solvent environment [5]. The uppercase letters (E, S, A, B, V, L) represent the solute descriptors that characterize key molecular properties of the compound undergoing transfer. These descriptors provide a quantitative basis for predicting a wide range of physicochemical properties including solubility, partition coefficients, skin permeability, toxicity parameters, and pharmacological activities [5] [7]. The model's strength lies in its system-independent descriptors - once characterized for a particular solute, these descriptors can be applied to predict its behavior across numerous environmental and biological systems.

The Solute Descriptors: Definition and Significance

E - Excess Molar Refractivity

The E descriptor represents the excess molar refractivity of a solute, expressed in units of (cm³ per mol)/10 [5]. This descriptor characterizes the solute's polarizability arising from π- and n-electrons. It encodes the dispersion interactions that occur when a solute induces a dipole in the solvent molecules. For compounds that are liquid at 20°C, the E descriptor can be determined experimentally from the characteristic volume and refractive index measurement [7]. For solid compounds, E can be predicted using computational methods including fragment-based approaches, molar refractivity predictions through tools like ChemSpider, or specialized software such as ACD/ADME Suite [5].

S - Dipolarity/Polarizability

The S descriptor represents the solute's dipolarity/polarizability, which quantifies the ability of a solute to engage in dipole-dipole and dipole-induced dipole interactions with the solvent environment [5]. This descriptor reflects how a solute's electron cloud can be distorted by solvent electric fields or how the solute itself can polarize solvent molecules. Unlike the E descriptor, S cannot be calculated directly from structure and must be determined experimentally through measurements such as liquid-liquid partition coefficients or chromatographic retention data [7]. The S parameter plays a crucial role in understanding how polar compounds distribute themselves between different media.

A and B - Hydrogen-Bond Acidity and Basicity

The A and B descriptors represent the solute's hydrogen-bond acidity and basicity, respectively [5]. These parameters quantify the solute's capacity to participate in hydrogen-bonding interactions:

- A descriptor: Measures the solute's ability to donate a hydrogen bond (hydrogen-bond acidity)

- B descriptor: Measures the solute's ability to accept a hydrogen bond (hydrogen-bond basicity)

These descriptors are particularly important for predicting the behavior of compounds containing functional groups such as hydroxyl, amine, carbonyl, and carboxyl groups. Like the S descriptor, A and B are predominantly determined through experimental measurements, though predictive computational methods exist [5] [7]. For compounds like carboxylic acids that can form dimers in non-polar solvents, separate A and B descriptors may be required for the monomeric and dimeric forms [5].

V - McGowan Characteristic Volume

The V descriptor represents the McGowan characteristic volume expressed in units of (cm³ per mol)/100 [5]. This parameter encodes size-related solvent-solute dispersion interactions, including a measure of the cavity term that represents the energy required to create a cavity in the solvent to accommodate the dissolved solute [5]. Unlike the other descriptors, V is the most straightforward to determine as it can be calculated directly from molecular structure using atomic contribution methods without requiring experimental measurements [5] [7]. The V descriptor effectively captures the size exclusion and steric effects that influence solute partitioning between different phases.

Table 1: Abraham Solute Descriptors: Definitions and Determination Methods

| Descriptor | Molecular Property | Units | Primary Determination Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| E | Excess molar refractivity | (cm³/mol)/10 | Refractive index (liquids) or prediction (solids) |

| S | Dipolarity/Polarizability | Dimensionless | Experimental measurement |

| A | Hydrogen-bond acidity | Dimensionless | Experimental measurement |

| B | Hydrogen-bond basicity | Dimensionless | Experimental measurement |

| V | McGowan characteristic volume | (cm³/mol)/100 | Calculation from molecular structure |

| L | Gas-hexadecane partition coefficient | Dimensionless | Experimental measurement |

Experimental Protocols for Descriptor Determination

Protocol 1: Determination of Solute Descriptors Using Liquid-Liquid Partition

Principle: This method determines solute descriptors by measuring partition coefficients in multiple totally organic and aqueous biphasic systems, then solving the system of equations to derive the descriptors [7].

Materials and Reagents:

- Totally organic biphasic systems: heptane-1,1,1-trifluoroethanol, isopentyl ether-propylene carbonate, isopentyl ether-ethanolamine, heptane-ethylene glycol, heptane-formamide, and 1,2-dichloroethane-ethylene glycol

- Aqueous biphasic systems: octanol-water, cyclohexane-water

- High-purity solutes for analysis

- Analytical instruments for concentration determination (GC, HPLC, or spectrophotometry)

Procedure:

- Prepare each biphasic system in separate containers and allow to equilibrate at constant temperature (typically 25°C)

- Introduce a known amount of solute to each system

- Agitate the systems thoroughly to establish partitioning equilibrium

- Allow phases to separate completely

- Determine solute concentration in both phases using appropriate analytical methods

- Calculate partition coefficients (P) as the ratio of concentrations between the two phases

- For each system, apply the Abraham model: log P = c + e·E + s·S + a·A + b·B + v·V

- Solve the system of equations across multiple biphasic systems to determine the solute descriptors

Performance Characteristics: When using six totally organic biphasic systems, the S, A, and B descriptors can be assigned with average absolute deviations (AAD) of approximately 0.04, 0.03, and 0.04, respectively, compared to the best estimate of true descriptor values [7]. The E descriptor for compounds solid at 20°C is estimated with higher AAD of approximately 0.11.

Protocol 2: Determination of Descriptors from Solubility Measurements

Principle: This approach determines solute descriptors using measured solubility data across multiple solvents, particularly useful for compounds with limited partition coefficient data [5].

Materials and Reagents:

- Series of organic solvents with known Abraham solvent parameters (polar and non-polar)

- Solute of interest

- Equipment for solubility measurement (shaking water baths, centrifugation, analytical instruments)

Procedure:

- Select a diverse set of solvents with known Abraham solvent parameters (c, e, s, a, b, v)

- Measure saturated solubility of the solute in each solvent at constant temperature

- Convert solubility values to molar concentrations

- For water-solvent systems, calculate partition coefficients using Ps = Cs/Cw, where Cs is solubility in organic solvent and Cw is aqueous solubility

- Apply the Abraham model: log Ps = c + e·E + s·S + a·A + b·B + v·V

- Use regression analysis with multiple solvent systems to solve for the solute descriptors

- For compounds that may dimerize (e.g., carboxylic acids), use separate regressions for polar solvents (monomer) and non-polar solvents (dimer)

Performance Characteristics: For trans-cinnamic acid, this approach allowed prediction of solubilities in both polar and non-polar solvents with an error of about 0.10 log units [5]. The method successfully generated separate descriptors for monomeric and dimeric forms of carboxylic acids.

Diagram 1: Experimental Workflow for Solute Descriptor Determination

Advanced Applications and Computational Approaches

Machine Learning for Descriptor Prediction

Recent advances have demonstrated the successful application of large language models (LLMs) for predicting Abraham solute descriptors directly from molecular structure. The AbraLlama-Solute model, based on the ChemLLaMA framework fine-tuned from LLaMA, predicts Abraham solute descriptors (E, S, A, B, V) with high accuracy using only SMILES strings as input [6]. This approach leverages transformer architectures initially pre-trained on extensive textual data, then fine-tuned on curated datasets of experimentally derived solute descriptors. The model was trained on 6,852 compounds with experimentally derived Abraham solute descriptors from the UFZ-LSER database and demonstrates accuracy comparable to existing methods [6]. This computational approach significantly accelerates descriptor determination, particularly for high-throughput applications in drug discovery and environmental chemistry.

Special Cases: Monomeric and Dimeric Forms

For compounds that can exist in different forms depending on solvent environment, such as carboxylic acids that form dimers in non-polar solvents, separate descriptor sets can be determined for each form [5]. The protocol involves:

- Using polar solvents where the solute exists predominantly in monomeric form to determine monomer descriptors

- Using non-polar solvents where dimerization occurs to determine dimer descriptors

- Applying the respective descriptor sets for predictions in different solvent environments

This approach was successfully demonstrated for trans-cinnamic acid, marking the first time descriptors for a carboxylic acid dimer were obtained [5]. The dimerization constant (Kdimer) varies significantly by solvent - for benzoic acid, Kdimer is 11,300 in cyclohexane, 5,010 in tetrachloromethane, and 590 in benzene [5].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Descriptor Determination

| Reagent/System | Type | Primary Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heptane-1,1,1-Trifluoroethanol | Totally organic biphasic | S, A, B descriptor assignment | High selectivity for hydrogen-bond interactions |

| Octanol-Water | Aqueous biphasic | B descriptor assignment | Standard system for lipophilicity measurement |

| Cyclohexane-Water | Aqueous biphasic | S, A descriptor assignment | Complementary selectivity to octanol-water |

| Isopentyl Ether-Propylene Carbonate | Totally organic biphasic | S, A, B descriptor assignment | Balanced selectivity for multiple interactions |

| UFZ-LSER Database | Computational resource | Experimental descriptor reference | Contains 6,852 compounds with experimental descriptors [6] |

| AbraLlama Models | Computational tool | Descriptor prediction from SMILES | Fine-tuned LLMs for solute and solvent parameters [6] |

Data Analysis and Validation

Statistical Validation of Descriptor Values

The accuracy of experimentally determined descriptors must be validated through statistical analysis of the regression results. Key validation parameters include:

- Average Absolute Deviation (AAD): For liquid-liquid partition methods, typical AAD values are 0.03-0.04 for S, A, and B descriptors when using six totally organic biphasic systems [7]

- Relative Average Absolute Deviation (RAAD): Expressed as percentage error, with values of approximately 9.7%, 3.1%, 4.0%, and 8.3% for E, S, A, and B descriptors, respectively, when using eight biphasic systems [7]

- Standard Deviation: For well-behaved systems, the Abraham model describes molar solubility with standard deviations of approximately 0.12-0.14 log units [5]

The quality of descriptor determination depends on selecting appropriate solvent systems that provide balanced coverage of different interaction types (dipolarity, hydrogen-bonding, dispersion). Systems with similar selectivity provide redundant information and should be avoided in favor of complementary systems.

Application in Solvent Selection and Prediction

The primary application of Abraham solute descriptors lies in predicting partition coefficients and solubilities for solvent selection in pharmaceutical and chemical processes. The general solvation model enables:

Solvent Comparison: Using modified Abraham solvent parameters (e₀, s₀, a₀, b₀, v₀) with zero intercept facilitates direct comparison of solvent properties [6]. Solvents with closely matching parameters exhibit similar solvation properties, enabling rational solvent substitution.

Solubility Prediction: For compounds with known descriptors, solubility in new solvents can be predicted using the Abraham model with the solvent parameters: log Ss = log Sw + c + e·E + s·S + a·A + b·B + v·V [6]

Process Optimization: In drug development, descriptors help optimize extraction, purification, and formulation processes by predicting compound behavior in complex multicomponent systems.

Diagram 2: Predictive Applications of Abraham Solute Descriptors

The Abraham solute descriptors E, S, A, B, and V provide a robust, system-independent framework for predicting solute behavior across diverse chemical and biological systems. Through established experimental protocols including liquid-liquid partition and solubility measurements, these descriptors can be determined with high accuracy and precision. Recent computational advances, particularly the application of fine-tuned large language models like AbraLlama, offer promising avenues for high-throughput descriptor prediction directly from molecular structure. When properly validated and applied, these descriptors serve as powerful tools for solvent selection, pharmaceutical development, and environmental risk assessment, forming a critical component of LSER-based research strategies. The continued refinement of determination methods and expansion of experimental databases will further enhance the utility and application scope of these fundamental molecular parameters in chemical research and development.

Linear Solvation Energy Relationships (LSERs) are a powerful quantitative tool used to correlate and predict how solvents influence a wide variety of chemical processes, from chemical reaction rates to solubility and chromatographic retention [8] [1]. The methodology was pioneered by Kamlet, Taft, and Abraham, who parameterized solvents based on their key interaction capabilities.

The most widely accepted model for this analysis is the Abraham LSER equation, which is expressed as:

SP = c + eE + sS + aA + bB + vV

In this equation, SP is a solute property of interest, most commonly the logarithm of a partition coefficient or a retention factor (e.g., log k') in chromatography [1]. The lowercase letters on the right side of the equation (e, s, a, b, v) are the system constants that reveal the complementary nature of the solvent system. The uppercase letters (E, S, A, B, V) are the solute descriptors that capture the intrinsic properties of the molecule being studied [1].

Table 1: Interpretation of the System Constants in the Abraham LSER Equation

| System Constant | Chemical Interaction it Represents | Opposing Solute Descriptor |

|---|---|---|

| e | The solvent's resistance to interact with solute π- or n-electrons (polarizability) | E - The solute's excess molar refractivity (polarizability) |

| s | The solvent's dipolarity/polarizability | S - The solute's dipolarity/polarizability |

| a | The solvent's hydrogen-bond basicity (HBA) | A - The solute's hydrogen-bond acidity (HBD) |

| b | The solvent's hydrogen-bond acidity (HBD) | B - The solute's hydrogen-bond basicity (HBA) |

| v | The solvent's resistance to cavity formation (endoergic process) | V - The solute's McGowan characteristic volume |

This application note provides a detailed guide for researchers and drug development professionals on how to interpret these system constants to gain deep insights into their solvent systems, thereby enabling more rational solvent selection in pharmaceutical research and development.

Chemical Interpretation of the System Constants

The system constants are determined through multiparameter linear regression analysis of a dataset comprising solutes with known descriptors [1]. Their signs and magnitudes provide a quantitative fingerprint of the solvent system's interaction properties.

The v Constant: Cavity Formation and Dispersion Interactions

The v constant is generally positive for processes involving transfer from a gas phase to a condensed phase (as in gas chromatography) because energy must be expended to separate solvent molecules and create a cavity for the solute [1]. A large, positive v value indicates that the solvent has high cohesion (e.g., water), making cavity formation difficult. Conversely, a negative v coefficient in a liquid-liquid partitioning system indicates that cavity formation is more favorable in that phase.

The a and b Constants: Hydrogen-Bonding Interactions

- The a Constant: A positive a value signifies that the solvent phase is hydrogen-bond basic (a good HBA) and favorably interacts with solutes that are hydrogen-bond acidic (good HBD). This would increase the retention of HBD solutes in chromatography or their solubility in that solvent [1].

- The b Constant: A positive b value signifies that the solvent phase is hydrogen-bond acidic (a good HBD) and favorably interacts with solutes that are hydrogen-bond basic (good HBA) [1].

The s and e Constants: Dipolarity and Polarizability Interactions

- The s Constant: A positive s value indicates that the solvent is dipolar/polarizable and stabilizes solutes that also possess significant dipolarity/polarizability (S) [8] [1].

- The e Constant: This constant represents the solvent's ability to engage in interactions involving solute π- or n-electrons. Interpretation is more complex and depends on the specific process being modeled [1].

Diagram 1: The relationship between solute descriptors, system constants, and the measured chemical property in an LSER model. The system constants represent the solvent's response to specific solute properties.

Case Study: Application in Solubility Prediction

LSER models are exceptionally valuable in pharmaceutical development for predicting the solubility of drug candidates, a critical factor in bioavailability. The following case study illustrates a typical protocol.

Case Study: Solubility of Buckminsterfullerene (C₆₀)

A study developed an LSER model to predict the solubility of the nanomaterial C₆₀ in various solvents [9]. The resulting model highlighted which solvent interactions most significantly influenced C₆₀ solubility. The analysis revealed that the hydrogen-bond donation ability (b coefficient), basicity scale (a coefficient), and dispersion interactions were the most effective parameters for correlating C₆₀ solubility [9]. This provides a clear guide for solvent selection when working with fullerenes.

Protocol: Determining System Constants for a Solubility Model

This protocol outlines the steps to develop a LSER model for solubility.

Step 1: Experimental Solubility Measurement

- Objective: Accurately determine the solubility (SP) of a diverse set of solute molecules in the solvent system of interest. SP is typically log(S), where S is the molar solubility.

- Method: Use a validated technique like the laser monitoring method [10] [11]. This involves tracking the change in laser beam intensity through a stirred solution as the temperature is controlled. The point at which the last crystal dissolves is detected by a sharp increase in light transmission, indicating saturation.

- Key Materials:

- Laser Monitoring System: A vessel with a thermostat, magnetic stirrer, laser source, and photodetector.

- Analytical Balance: For precise weighing of solutes and solvents.

Step 2: Compile Solute Descriptor Data

- Objective: Obtain the Abraham solute descriptors (E, S, A, B, V) for each compound in your training set.

- Method: Source data from published databases or the scientific literature [1]. Ensure the training set includes solutes with a wide range of descriptor values to avoid collinearity.

Step 3: Multivariate Linear Regression

- Objective: Calculate the system constants (e, s, a, b, v, c) for your solvent system.

- Method: Use statistical software (e.g., R, Python with scikit-learn) to perform a multiple linear regression with the experimental log(S) values as the dependent variable and the solute descriptors as the independent variables.

- Validation: Assess the model's quality using the coefficient of determination (R²), cross-validation, and analysis of residuals.

Table 2: Exemplar LSER System Constants for Different Process Types

| Process or System | v | s | a | b | Key Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gas → Water Partitioning | Large Positive | Variable | Positive | Positive | High cohesive energy (v) of water; strong HBA (a) and HBD (b) character. |

| Octanol/Water Partition (log P) | ~2.17 | -1.00 | -3.32 | -4.39 | The negative a, b, and s values indicate that water is a much stronger HBD, HBA, and dipolar solvent than wet octanol [1]. |

| C₆₀ Solubility in Organic Solvents | Significant | Less Significant | Significant (Positive) | Significant (Negative) | Solubility favored by solvent HBA basicity (a) and disfavored by solvent HBD acidity (b) [9]. |

Diagram 2: A workflow for developing an LSER model to predict solubility, from experimental design to practical application.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for LSER Studies

| Item Name | Function/Description | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Solvent Training Set | A collection of solvents with characterized π*, α, and β parameters [8]. | Used to establish a diverse dataset for initial model building and understanding solvent property space. |

| Solute Probe Training Set | A set of compounds with known Abraham descriptors (E, S, A, B, V) [1]. | Essential for performing the multivariate regression to determine the system constants of a new solvent or system. |

| Standard Reference Materials | Certified materials with known elemental composition (e.g., NIST SRM610) [12]. | Used for calibration and verification of analytical methods like LIBS or ICP-MS that may support LSER studies. |

| Laser Monitoring System | Apparatus with laser, thermostatted vessel, and detector to determine solubility endpoints [10] [11]. | Core equipment for accurately measuring solute solubility (SP) for LSER models focused on dissolution. |

The system constants e, s, a, b, and v of the Abraham LSER equation are more than just fitting parameters; they are a quantitative fingerprint that reveals the specific interaction capabilities of a solvent system. By interpreting these constants, researchers and drug development professionals can move beyond trial-and-error and make rational, knowledge-driven decisions about solvent selection. This methodology provides a deep chemical understanding of how a solvent will interact with different solute functionalities, ultimately enabling the optimization of processes critical to pharmaceuticals, such as solubility enhancement, purification via chromatography, and formulation stability.

Linear Solvation Energy Relationships (LSERs) represent a powerful quantitative approach for predicting the partitioning behavior of solutes in different chemical and biological systems. Originally developed by Abraham, these thermodynamic models express free energy-related properties as a linear combination of molecular descriptors that encode specific solute-solvent interaction capabilities [1] [13]. The fundamental LSER equation takes the form:

SP = c + eE + sS + aA + bB + vV

Where SP is any free energy-related solute property such as the logarithm of a partition coefficient (log K) or retention factor (log k') [1]. The uppercase letters (E, S, A, B, V) represent solute-specific molecular descriptors, while the lowercase coefficients (c, e, s, a, b, v) are system constants that characterize the complementary properties of the phases between which partitioning occurs [13]. This robust framework finds extensive applications across chemical engineering, environmental science, and pharmaceutical research, including predicting toxicity, soil-water absorption coefficients, and drug transport properties [13].

The thermodynamic foundation of LSER stems from the interpretation of partitioning processes as a combination of an endoergic cavity formation/solvent reorganization process and exoergic solute-solvent attractive interactions [1]. The partitioning of a solute between two condensed phases is thermodynamically equivalent to the difference between two gas/liquid solution processes, providing a coherent framework for understanding and predicting solute behavior across diverse systems [1].

Molecular Descriptors and Their Thermodynamic Significance

Solute Descriptor Definitions

The LSER model utilizes five fundamental solute descriptors that capture the principal modes of molecular interactions. Each descriptor quantifies a specific aspect of the solute's interaction potential, providing a comprehensive characterization of its behavior in solution phases [1].

Table 1: LSER Solute Descriptors and Their Molecular Interpretation

| Descriptor | Symbol | Molecular Interpretation | Interaction Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Excess molar refractivity | E | Polarizability of π and n electrons | Dispersion interactions |

| Dipolarity/ Polarizability | S | Dipolarity and polarizability | Dipole-dipole, dipole-induced dipole |

| Hydrogen-bond acidity | A | Hydrogen bond donating ability | Solute (donor) to solvent (acceptor) |

| Hydrogen-bond basicity | B | Hydrogen bond accepting ability | Solute (acceptor) to solvent (donor) |

| McGowan's characteristic volume | V | Molecular size | Endoergic cavity formation |

System Constants and Their Interpretation

The system constants in the LSER equation reflect the complementary properties of the specific phases between which partitioning occurs. These coefficients indicate the relative importance of each type of interaction in the system being studied [1] [13].

Table 2: LSER System Constants and Their Thermodynamic Meaning

| Coefficient | Symbol | Phase Property | Thermodynamic Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | c | System constant | Phase-specific constant |

| Polarizability interactions | e | Phase polarizability | Complimentary to E |

| Dipolarity interactions | s | Phase dipolarity/polarizability | Complimentary to S |

| Hydrogen-bond basicity | a | Phase hydrogen-bond accepting ability | Complimentary to A (solute acidity) |

| Hydrogen-bond acidity | b | Phase hydrogen-bond donating ability | Complimentary to B (solute basicity) |

| Cavity formation | v | Phase cohesion energy | Resistance to cavity formation |

Experimental Protocols for LSER Development

Protocol 1: Determination of Partition Coefficients for LSER Model Calibration

This protocol outlines the experimental procedure for determining solute partition coefficients between low-density polyethylene (LDPE) and water, as exemplified in recent LSER studies [14].

Materials and Equipment

- Test solutes: A chemically diverse set of compounds (e.g., 156 compounds for robust model)

- Polymeric phase: Low-density polyethylene (LDPE) film or particles

- Aqueous phase: Deionized water or buffer solution

- Containers: Glass vials with minimal headspace, Teflon-lined caps

- Analytical instrumentation: HPLC-UV, GC-MS, or LC-MS systems for quantification

- Temperature control: Water bath or incubator maintained at 25°C ± 0.5°C

- Separation equipment: Centrifuge capable of 3000-5000 × g

- Sample preparation: Vortex mixer, precision pipettes, analytical balance

Procedure

Preparation of solute solutions: Prepare stock solutions of each test solute in appropriate solvents at concentrations suitable for detection by analytical methods.

Equilibration setup: For each solute, add measured amounts of LDPE and aqueous phase to glass vials. The phase ratio should be optimized to ensure measurable solute concentrations in both phases after equilibration.

Solute addition and equilibration: Spike the systems with solute solutions, seal to prevent evaporation, and equilibrate in a temperature-controlled environment with continuous agitation for 24-72 hours (confirm equilibrium through time-course studies).

Phase separation: After equilibration, separate the phases carefully. For LDPE-water systems, remove the aqueous phase first, then rinse the polymer surface gently with water to remove adhering droplets.

Solute quantification:

- For aqueous phase: Analyze directly or after appropriate dilution using HPLC, GC, or other suitable analytical methods.

- For polymer phase: Extract solute from LDPE using appropriate solvent (e.g., hexane, acetonitrile) or measure directly if possible.

- Include calibration standards with known concentrations covering the expected range.

Calculation of partition coefficients: Calculate the partition coefficient for each solute using the formula: Ki,LDPE/W = Ci,LDPE / Ci,W where Ci,LDPE and Ci,W represent the equilibrium concentrations in LDPE and water phases, respectively. Use the logarithm of this value (log Ki,LDPE/W) for LSER analysis.

Quality control: Include replicate systems (minimum n=3) for quality assurance and determine standard deviations.

Protocol 2: LSER Model Calibration and Validation

This protocol describes the statistical procedures for developing and validating LSER models using experimental partition coefficient data [14] [13].

Materials and Software

- Experimental data: Experimentally determined partition coefficients (log K) for a diverse set of solutes

- Solute descriptors: Experimentally determined or predicted Abraham solute parameters (E, S, A, B, V) for all test compounds

- Statistical software: JMP, R, Python, or similar with multiple linear regression capabilities

- Computational resources: Standard computer with sufficient memory for data analysis

Procedure

Data compilation: Compile a dataset containing experimentally determined log K values and corresponding solute descriptors (E, S, A, B, V) for all compounds in the training set.

Dataset partitioning: Randomly divide the complete dataset into training (~67%) and validation (~33%) sets, ensuring both sets maintain chemical diversity [14].

Model calibration: Perform multiple linear regression analysis on the training set using the equation: logKi = c + eE + sS + aA + bB + vV where the system constants (c, e, s, a, b, v) are determined through the regression.

Model validation: Apply the calibrated model to the independent validation set. Calculate performance statistics including R² (coefficient of determination) and RMSE (root mean square error) to evaluate predictive accuracy [14].

Benchmarking with predicted descriptors: For applications where experimental solute descriptors are unavailable, evaluate model performance using predicted descriptors from Quantitative Structure-Property Relationship (QSPR) tools [14].

Chemical space evaluation: Assess the chemical diversity of the solute set using metrics such as Average Absolute Correlation (AAC) to identify potential multicollinearity issues [13].

Advanced Applications and Methodological Considerations

Solute Set Selection Strategies for Efficient LSER Development

Selecting an optimal solute set is crucial for developing robust LSER models while minimizing experimental effort. Two principal strategies have been identified for selecting minimal solute sets that provide maximum information content [13]:

Table 3: Comparison of Solute Set Selection Strategies for LSER Development

| Strategy | Objective | Method | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strategy 1: Minimize Descriptor Correlation | Reduce multicollinearity | Select compounds with minimal interdependence among descriptors (low AAC) | Improved statistical robustness; isolates individual descriptor contributions | May not span full chemical space; coefficient estimates may deviate from true values |

| Strategy 2: Maximize Descriptor Differences | Maximize chemical diversity | Select compounds with maximum differences between normalized descriptors | Better represents broader chemical space; coefficient estimates closer to true values | Higher descriptor correlation (multicollinearity); requires careful implementation |

Case Study: LSER for LDPE-Water Partitioning

A recent comprehensive study developed and validated an LSER model for partition coefficients between low-density polyethylene (LDPE) and water, resulting in the following equation [14]:

logKi,LDPE/W = -0.529 + 1.098E - 1.557S - 2.991A - 4.617B + 3.886V

This model demonstrated exceptional performance with R² = 0.991 and RMSE = 0.264 for the training set (n = 156). For the independent validation set (n = 52), the model maintained strong predictive power with R² = 0.985 and RMSE = 0.352 when using experimental solute descriptors [14]. When employing QSPR-predicted descriptors instead of experimental ones, the statistics (R² = 0.984, RMSE = 0.511) remained acceptable for applications where experimental descriptors are unavailable [14].

The study further converted partition coefficients to logKi,LDPEamorph/W by considering only the amorphous fraction of the polymer as the effective phase volume. This adjustment changed the constant in the equation from -0.529 to -0.079, rendering the model more similar to a corresponding LSER for n-hexadecane/water systems and providing fundamental insights into the thermodynamic driving forces [14].

Comparison of Polymer Sorption Behaviors

LSER system parameters enable direct comparison of sorption behavior across different polymeric materials. Studies comparing LDPE to polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), polyacrylate (PA), and polyoxymethylene (POM) reveal that polymers with heteroatomic building blocks (PA, POM) exhibit stronger sorption for polar, non-hydrophobic solutes due to their capabilities for polar interactions [14]. For logKi,LDPE/W values up to 3-4, these polar polymers show enhanced sorption, while above this range, all four polymers exhibit roughly similar sorption behavior dominated by hydrophobic interactions [14].

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for LSER Studies

| Category | Specific Items | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymer Phases | Low-density polyethylene (LDPE) | Model polymeric phase for partitioning studies | Film or particle form, characterized for amorphous content |

| Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) | Silicone-based polymer for comparative sorption studies | Cross-linked or non-cross-linked forms | |

| Polyacrylate (PA) | Polar polymer for studying specific interactions | Various compositions depending on application | |

| Reference Solutes | Chemically diverse compound sets | Model solutes for LSER calibration | 50-200 compounds spanning range of E, S, A, B, V values |

| Internal standards | Quantification and quality control | Stable isotopically labeled analogs or structurally similar compounds | |

| Analytical Instruments | HPLC-UV systems | Solute quantification in aqueous phases | Reverse-phase C18 columns, UV-Vis detection |

| GC-MS systems | Volatile solute analysis | Capillary columns, EI or CI ionization | |

| LC-MS systems | Non-volatile and polar solute analysis | ESI or APCI ionization sources | |

| Software and Databases | UFZ-LSER database | Source of solute descriptors | Version 3.2.1+ from Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research [15] |

| Statistical packages | Multiple linear regression analysis | JMP, R, Python with scikit-learn | |

| QSPR prediction tools | Solute descriptor prediction | Commercial or open-source quantum chemistry packages |

The thermodynamic foundation of Linear Solvation Energy Relationships provides a robust framework for predicting partition coefficients and understanding molecular interactions across diverse chemical and biological systems. Through careful experimental design, appropriate solute set selection, and rigorous statistical validation, researchers can develop accurate predictive models that span broad chemical spaces. The continued refinement of LSER methodologies, including the integration of predicted solute descriptors from quantum chemical calculations, promises to expand the applicability of these powerful models in pharmaceutical research, environmental science, and chemical engineering. As demonstrated in the case studies, LSERs represent not merely correlative tools but physically meaningful models grounded in the fundamental thermodynamics of solvation.

Linear Solvation Energy Relationships (LSERs) represent a cornerstone of physical organic chemistry, providing a quantitative framework for predicting how solvents influence chemical processes. The development of LSERs has been instrumental in advancing fields ranging from synthetic chemistry to pharmaceutical development. The journey from the Kamlet-Taft model to the modern Abraham model exemplifies the evolution of these relationships, each building upon the other to create more robust and comprehensive predictive tools. These models transform qualitative chemical intuition about solvent effects into quantitative, predictable parameters that can be applied across diverse scientific disciplines.

The fundamental principle underlying LSERs is that free-energy related properties of solutes, such as partition coefficients and reaction rates, can be correlated with descriptors encoding molecular interactions [2]. This review traces the historical development of these models, provides detailed protocols for their application, and illustrates their practical utility in modern scientific research, particularly in drug development.

Theoretical Evolution: From Kamlet-Taft to Abraham

The Kamlet-Taft Solvatochromic Comparison Method

The Kamlet-Taft model, introduced in the 1970s and 1980s, was a pioneering approach that parameterized solvent effects using three key parameters [16] [17]. This model utilized solvatochromism—the shift in absorption spectra of dyes in different solvents—to quantify solvent properties empirically.

The original Kamlet-Taft LSER takes the general form:

Where the solvent parameters are:

- π* (dipolarity/polarizability): Measures the solvent's ability to stabilize a charge or dipole through non-specific dielectric interaction.

- α (hydrogen bond donor acidity): Quantifies the solvent's ability to donate a hydrogen bond.

- β (hydrogen bond acceptor basicity): Quantifies the solvent's ability to accept a hydrogen bond.

This model successfully correlated thousands of solvent-dependent phenomena but was primarily limited to describing solvent properties rather than solute properties.

The Abraham Model: A Comprehensive Solute-Centric Approach

The Abraham model, developed subsequently, expanded the Kamlet-Taft approach by introducing a more comprehensive set of solute descriptors that could be used with complementary system coefficients [2] [18]. This model is characterized by two primary equations for different partitioning processes.

For partitioning between two condensed phases:

For gas-to-solvent partitioning:

Where the solute descriptors are:

- E = excess molar refractivity

- S = dipolarity/polarizability

- A = overall hydrogen bond acidity

- B = overall hydrogen bond basicity

- V = McGowan characteristic volume

- L = gas-hexadecane partition coefficient

The corresponding lower-case letters (e, s, a, b, v, l) are system-specific coefficients that describe the complementary properties of the phases between which partitioning occurs [2].

Theoretical Integration and Relationship Between Models

The Abraham model can be viewed as a direct descendant of the Kamlet-Taft approach, with several key theoretical advancements. While Kamlet-Taft parameters primarily describe solvents, Abraham parameters describe both solutes and solvents, creating a more versatile framework [2]. There are correlations between the two sets of parameters—Abraham's A and B descriptors correspond to Kamlet-Taft's α and β, respectively, though they are defined differently and obtained through different experimental methods.

The Abraham model also incorporates additional descriptors that capture molecular size (V) and dispersion interactions (L) more explicitly, providing a more complete description of intermolecular interactions [18]. The thermodynamic basis for the linearity of these relationships has been explored through combination with equation-of-state thermodynamics and the statistical thermodynamics of hydrogen bonding, verifying the fundamental validity of the LFER approach [2].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Kamlet-Taft and Abraham LSER Parameters

| Aspect | Kamlet-Taft Model | Abraham Model |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Solvent properties | Solute and system properties |

| Hydrogen Bond Acidity | α (solvent HBD ability) | A (solute HBA ability) |

| Hydrogen Bond Basicity | β (solvent HBA ability) | B (solute HBD ability) |

| Dipolarity/Polarizability | π* | S |

| Size/Dispersion Terms | Not explicitly included | V (McGowan volume) and L |

| Refractivity | Not explicitly included | E (excess molar refractivity) |

| Primary Application | Correlating solvent effects | Predicting partition coefficients and solubility |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Determining Kamlet-Taft Parameters via Solvatochromic Method

Principle: Kamlet-Taft parameters are determined using solvent-sensitive spectroscopic probes whose absorption maxima shift depending on solvent polarity and hydrogen-bonding characteristics [19].

Protocol:

- Solution Preparation: Prepare solutions of each solvatochromic dye (Table 2) at concentrations of approximately 10⁻⁵ M in the solvent of interest [19].

- Spectroscopic Measurement: Record UV-visible absorption spectra over the range of 300-800 nm using a double-beam spectrophotometer.

- Temperature Control: Maintain constant temperature (±0.1°C) using a circulating water bath, particularly when working near phase transition regions.

- Wavelength Measurement: Precisely determine the maximum absorption wavelength (λₘₐₓ) for each dye in the solvent.

- Parameter Calculation: Calculate parameters using established equations:

- π* is determined from the absorption maxima of nitroanisoles: π* = (νₘₐₓ - 34.12)/-2.432 where νₘₐₓ is in kK (cm⁻¹×10⁻³)

- β is determined from the bathochromic shift of 4-nitroaniline relative to N,N-diethyl-4-nitroaniline

- α is derived from the solvatochromic shift of Reichardt's dye after accounting for π* contributions

Key Considerations: Use spectroscopy-grade dyes without further purification. Ensure solutions are optically clear and free of particulate matter. For anisotropic systems (e.g., liquid crystals), control alignment and measure at multiple orientations [19].

Determining Abraham Solute Descriptors

Principle: Abraham solute descriptors are determined through a combination of experimental measurements and computational approaches [18].

Protocol for Experimental Determination:

- McGowan Characteristic Volume (V): Calculate from molecular structure using atomic volumes and number of bonds: V = (Σ atomic volumes - 6.56 × number of bonds)/100

- Excess Molar Refractivity (E): Determine from refractive index measurements: E = (n² - 1)/(n² + 2) × MW/density - V × 0.986

- Hydrogen Bond Acidity and Basicity (A and B): Determine from partition coefficient measurements between organic solvents and water

- Dipolarity/Polarizability (S): Derive from chromatographic retention data or computational methods

- Gas-Hexadecane Partition Coefficient (L): Measure via gas-liquid chromatography using hexadecane as the stationary phase

Computational Approaches: With the limited availability of experimental data, open random forest models using Chemical Development Kit (CDK) descriptors have been developed to predict Abraham coefficients with out-of-bag R² values ranging from 0.31 for e to 0.92 for a [18].

Application Protocol: Solvent Selection for MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry

Principle: Proper solvent selection is critical for matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometric (MALDI-TOF MS) analysis of synthetic polymers [20].

Protocol:

- Polymer Solubility Assessment: Determine polymer solubility in candidate solvents using Hansen solubility parameters as an initial guide.

- Matrix and Cationization Reagent Selection:

- For polystyrene: Use dithranol as matrix and silver trifluoroacetate as cationization reagent

- For poly(ethylene glycol): Use 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid as matrix and sodium trifluoroacetate as cationization reagent

- Sample Preparation: Prepare homogeneous solutions using solvents identified as good solvents for the polymer.

- MALDI-TOF MS Analysis: Apply standard MALDI-TOF MS procedures.

- Spectra Evaluation: Compare quality of mass spectra obtained with different solvents.

Key Finding: Reliable MALDI mass spectra are obtained only when employing solvents that dissolve the polymer, while samples in non-solvents fail to provide spectra. The solubility of the matrix and cationization reagent is less important than polymer solubility [20].

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for LSER Applications

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Reichardt's betaine dye | Primary probe for determining Kamlet-Taft π* and α parameters | Spectroscopy grade, λₘₐₓ shifts from ~450 nm (in dipolar solvents) to ~800 nm (in hydroxylic solvents) |

| N,N-Dimethyl-4-nitroaniline | Secondary probe for Kamlet-Taft π* parameter | λₘₐₓ ~410 nm in nonpolar solvents |

| 4-Nitroaniline | Probe for Kamlet-Taft β parameter | Used in combination with N,N-diethyl-4-nitroaniline |

| Coumarin 504 | Fluorescent probe for solvatochromic studies | Exhibits strong emission shifts with solvent polarity |

| Dithranol | Matrix for MALDI-TOF MS of synthetic polymers (e.g., polystyrene) | ≥99% purity for optimal results |

| 2,5-Dihydroxybenzoic acid | Matrix for MALDI-TOF MS of polymers (e.g., poly(ethylene glycol)) | ≥99% purity for optimal results |

| Silver trifluoroacetate | Cationization reagent for MALDI-TOF MS of polystyrene | ≥99.9% purity |

| Sodium trifluoroacetate | Cationization reagent for MALDI-TOF MS of poly(ethylene glycol)) | ≥99.9% purity |

Applications in Drug Development and Pharmaceutical Sciences

The transition from Kamlet-Taft to Abraham parameters has significantly enhanced predictive capabilities in pharmaceutical research. The Abraham model finds extensive application in predicting partition coefficients, solubility, and other pharmacokinetically relevant properties [18].

Predicting Solubility and Partition Coefficients

The Abraham model enables prediction of solvent/water partition coefficients using the equation:

Similarly, solubility in organic solvents can be predicted by:

where Sₛ is the molar concentration in the organic solvent and Sₚ is the molar concentration in water [18].

These predictions are crucial for pharmaceutical development, enabling rational selection of excipients, prediction of membrane permeability, and estimation of bioavailability. The model has been successfully applied to predict partitioning into biological membranes, blood-to-tissue distribution, and solute encapsulation in drug delivery systems.

Green Solvent Selection

The Abraham model facilitates the identification of sustainable solvent replacements in pharmaceutical manufacturing. For instance, models predict that propylene glycol may serve as a general sustainable solvent replacement for methanol in many applications [18]. This application is particularly valuable as the pharmaceutical industry seeks to reduce its environmental impact while maintaining process efficiency.

Absorption and Distribution Prediction

Abraham descriptors correlate with crucial ADME (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion) properties. The model has been used to predict drug partitioning between blood and specific organs, providing valuable insights during early drug development stages [18]. This application demonstrates how LSER approaches bridge fundamental solvation science with practical pharmaceutical applications.

Visualization of LSER Evolution and Applications

Diagram 1: Historical evolution from Kamlet-Taft to Abraham LSER models and their applications in drug development. The progression shows how fundamental observations led to increasingly sophisticated models with direct pharmaceutical applications.

Diagram 2: Generalized workflow for LSER application showing the progression from experimental data collection to practical application, highlighting the interconnected phases of the process.

The historical progression from the Kamlet-Taft model to the modern Abraham model represents significant theoretical and practical advancement in solvation science. While the Kamlet-Taft approach provided the crucial foundation for quantifying solvent effects through solvatochromic parameters, the Abraham model expanded this framework into a more comprehensive and versatile tool that describes both solute properties and system characteristics.

The continued development and application of these LSER approaches remain essential for pharmaceutical research, enabling more efficient drug development, greener solvent selection, and more accurate prediction of pharmacokinetic properties. As computational methods improve and more experimental data becomes available, these models will continue to evolve, further enhancing their predictive power and expanding their application domains.

The integration of LSER approaches with modern computational chemistry and machine learning represents the future of this field, promising even more accurate predictions of solvation-related properties across the chemical and biological sciences.

Implementing LSER in Practice: From Chromatography to Pharmaceutical Development

Step-by-Step Guide to Constructing an LSER Model for Solvent Selection

Linear Solvation Energy Relationships (LSERs) are powerful quantitative models used to predict and interpret the partitioning behavior of solutes in different chemical and biological phases. The foundational model, widely accepted and symbolized by Abraham, is expressed by the equation: SP = c + eE + sS + aA + bB + vV [1]. In this equation, SP represents a solvation property, most commonly the logarithm of a partition coefficient or retention factor (e.g., log K) [1]. The uppercase letters represent solute-dependent parameters: E represents the excess molar refractivity, S represents dipolarity/polarizability, A and B represent hydrogen-bond acidity and basicity, respectively, and V represents the McGowan characteristic molar volume [1]. The lowercase letters (e, s, a, b, v) are the system coefficients determined through regression analysis; they reflect the complementary properties of the solvent system and indicate how strongly the phase responds to each type of solute interaction [1]. The construction of a robust LSER model enables researchers in drug development to rationally select solvents for processes like extraction, purification, and formulation based on a deep understanding of the underlying molecular interactions.

Theoretical Foundation and Key Components

The LSER model quantitatively dissects the solvation process into its fundamental intermolecular interactions. The partitioning of a solute between two phases is thermodynamically equivalent to the difference in the solute's solution process into each phase individually [1]. The solute descriptors probe specific interaction capabilities: E and S account for polarizability and dipole-dipole interactions, A and B quantify hydrogen-bonding, and V primarily represents the endoergic cavity formation energy required to accommodate the solute within the solvent structure [1]. The system coefficients, once determined, provide a chemical fingerprint of the solvent system. A positive v-coefficient indicates that dissolution is favored for larger solutes in that phase, often a sign of cohesion and strong solvent-solvent interactions. A positive a or b coefficient signifies that the phase acts as a strong hydrogen-bond acceptor or donor, respectively [1]. This interpretative power is what makes LSERs invaluable beyond mere prediction, allowing scientists to understand the specific interactions governing solubility and partitioning in complex systems, including those relevant to pharmaceutical development.

Table 1: Interpretation of LSER Solute Descriptors

| Descriptor | Chemical Interpretation | Role in Solvation |

|---|---|---|

| E | Excess molar refractivity | Measures polarizability of π- and n-electrons |

| S | Dipolarity/Polarizability | Measures strength of dipole-dipole & induced dipole interactions |

| A | Hydrogen-Bond Acidity | Measures the solute's ability to donate a hydrogen bond |

| B | Hydrogen-Bond Basicity | Measures the solute's ability to accept a hydrogen bond |

| V | McGowan's Characteristic Volume | Relates to the endoergic energy required for cavity formation in the solvent |

Computational Workflow for LSER Model Development

The development of an LSER model follows a structured workflow from data collection to model deployment, ensuring its robustness and predictive power. The initial and most critical step is the acquisition of high-quality experimental data for the solvation property (SP) of interest for a training set of compounds. This is followed by the collection of solute descriptors (E, S, A, B, V) for each compound in the training set. These descriptors can be obtained experimentally or, for greater scope, predicted using Quantitative Structure-Property Relationship (QSPR) tools [14]. With the dataset prepared, multiple linear regression is performed to fit the Abraham equation and determine the system coefficients (e, s, a, b, v) and the constant (c). The model must then undergo rigorous validation using an independent set of compounds not included in the training set [14]. Finally, the validated model can be used to predict the solvation property for new compounds based solely on their chemical structure, enabling informed solvent selection.

Experimental Protocol for Data Generation

Determining Partition Coefficients (Log K)

A core application of LSERs is predicting partition coefficients, such as for Low-Density Polyethylene (LDPE) and water, which is critical for assessing the leaching of compounds from packaging materials into pharmaceutical solutions [14].

Materials:

- Purified water (e.g., Milli-Q grade)

- LDPE film (pre-cleaned with solvent and dried)

- Analytical standard of the solute(s) of interest

- HPLC vials with Teflon-lined caps

- Analytical instrument (e.g., HPLC-UV, GC-MS) for quantification

- Constant-temperature incubator or shaker

Methodology:

- Preparation: Cut the LDPE film into precise, weighed pieces. Prepare an aqueous solution of the solute at a known concentration.

- Equilibration: Add the LDPE film and the solute solution to the HPLC vials, ensuring no headspace. Seal the vials tightly.

- Incubation: Place the vials in a constant-temperature shaker. Agitate at a controlled speed and temperature (e.g., 25°C) for a predetermined time (e.g., 24-48 hours) to ensure equilibrium is reached.

- Quantification: After equilibration, carefully separate the polymer from the aqueous phase. Analyze the concentration of the solute in the aqueous phase (Cwater) using your analytical instrument. The concentration in the polymer phase (CLDPE) is calculated by mass balance from the initial concentration.

- Calculation: The partition coefficient is calculated as Log KLDPE/W = log (CLDPE / Cwater).

Key Considerations for Robust Experimentation

- Chemical Diversity of Training Set: The set of solutes used for model training must be chemically diverse, encompassing a wide range of E, S, A, B, and V values to ensure the model's applicability domain is broad and its predictability is reliable [14].

- Validation: Always validate the final model using an independent set of observations (~30% of total data) that were not used in the training process. This tests the model's predictive power for new compounds. Benchmark the model's performance (R², RMSE) against existing models [14].

- Domain of Applicability: LSER models are typically only valid for neutral chemicals. Caution must be exercised with ions or compounds that can ionize under the experimental conditions [4].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for LSER Modeling

| Resource Category | Specific Example(s) | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Solute Descriptor Database | UFZ-LSER Database [4] | Provides curated experimental solute descriptors (E, S, A, B, V) for a vast number of chemicals. |

| Computational Tool | QSPR Prediction Software [14] | Calculates/predicts solute descriptors for chemicals not listed in experimental databases. |

| Modeling Software | R, Python (with scikit-learn), MATLAB | Performs multiple linear regression analysis to derive system coefficients from experimental data. |

| Experimental Solutes | Chemically diverse set (e.g., aniline, benzene, butan-1-ol, octanol) [4] | Used to generate training and test data for the solvation property of interest. |

Data Analysis and Model Validation

Performing Regression and Interpreting Coefficients

With a dataset of log SP values and the corresponding solute descriptors for your training set, multiple linear regression is used to solve for the system coefficients in the Abraham equation. The quality of the fit is assessed using statistics such as the coefficient of determination (R²), which should ideally be >0.99 for well-behaved systems like polymer-water partitioning [14], and the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), which indicates the average prediction error of the model. The signs and magnitudes of the derived coefficients (e, s, a, b, v) are then interpreted chemically. For instance, a strongly negative a-coefficient in a log KLDPE/W model indicates that the LDPE phase is a very poor hydrogen-bond acceptor compared to water, and solutes with high hydrogen-bond acidity (A) will thus partition strongly into the water phase [14].

Benchmarking and Advanced Applications

After validation, the model should be benchmarked against existing LSER models for similar systems to contextualize its performance. Advanced applications involve comparing the system parameters of different phases. For example, the sorption behavior of LDPE can be compared to that of polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), polyacrylate (PA), and polyoxymethylene (POM) by analyzing their respective LSER coefficients, revealing which polymers are best for sorbing specific types of analytes [14]. Furthermore, to compare a solid polymer phase to a liquid phase like n-hexadecane, the partition coefficient can be converted to represent the amorphous fraction of the polymer as the effective phase volume, which often makes the resulting LSER model more similar to that of the liquid alkane [14].

The step-by-step methodology outlined in this application note provides a robust framework for constructing and validating LSER models for solvent selection. By leveraging curated databases for solute descriptors [4], following rigorous experimental protocols for data generation, and applying thorough statistical validation [14], researchers can develop highly accurate predictive models. The power of the LSER approach lies in its dual capability: it is both a predictive tool for log P and solubility, and an interpretive framework that reveals the specific hydrogen-bonding, polar, and dispersion interactions governing solute partitioning. This makes it an indispensable asset in the scientist's toolkit for rational solvent selection in drug development and related fields.

Linear Solvation Energy Relationships (LSER) represent a powerful quantitative approach for modeling and predicting retention in various chromatographic techniques. The fundamental LSER model, based on the solvation parameter model, describes chromatographic retention as a function of specific molecular interactions between analytes, stationary phase, and mobile phase. The widely adopted Abraham LSER model is expressed by the equation [21]:

[ \log SP = c + eE + sS + aA + bB + vV ]

where ( \log SP ) represents the logarithm of the retention factor (e.g., log k), and the capital letters represent solute-specific descriptors: ( E ) is the excess molar refraction, ( S ) the solute dipolarity/polarizability, ( A ) and ( B ) the overall hydrogen-bond acidity and basicity, and ( V ) the McGowan characteristic volume [21]. The lowercase letters in the equation are the system coefficients that reflect the complementary properties of the chromatographic system: ( e ) represents the ability of the stationary phase to interact with electron pairs, ( s ) its dipolarity/polarizability, ( a ) its hydrogen-bond basicity, ( b ) its hydrogen-bond acidity, and ( v ) its lipophilicity or ability to interact with a methylene group [21].

The strength of the LSER approach lies in its ability to separate and quantify the individual intermolecular interactions that collectively determine retention behavior. This provides a mechanistic understanding that goes beyond simple retention prediction, offering insights into the fundamental processes occurring during chromatographic separation. The model has proven applicable across multiple chromatographic modes including reversed-phase LC, gas chromatography, and normal-phase LC [22].

LSER Fundamentals and Theoretical Framework

Molecular Interactions in Chromatography

Chromatographic retention is governed by a balance of several intermolecular forces between analytes, stationary phase, and mobile phase. The LSER model systematically accounts for these interactions [22]:

Dispersive interactions (vV term): These London forces arise from temporary dipoles in molecules and are primarily responsible for hydrophobic retention in reversed-phase systems. The V descriptor represents the molar volume of the solute, while v indicates the tendency of the stationary phase to interact via dispersion forces.

Polarity/polarizability interactions (sS term): This term accounts for dipole-dipole and dipole-induced dipole interactions between the solute and stationary phase. The S descriptor quantifies the solute's dipolarity/polarizability, while s reflects the stationary phase's capacity for such interactions.

Hydrogen-bonding interactions (aA and bB terms): Hydrogen bonding represents one of the most specific interactions in chromatography. The A and B descriptors represent the solute's hydrogen-bond donating and accepting abilities, respectively, while a and b coefficients characterize the stationary phase's complementary hydrogen-bond accepting and donating properties.

Electron pair interactions (eE term): This term accounts for interactions involving π- and n-electron pairs of the solute. The E descriptor represents the solute's excess molar refraction, which correlates with its polarizability due to π- and n-electrons, while e characterizes the stationary phase's ability to participate in such interactions.

Advanced LSER Modeling Approaches

Beyond the basic local LSER model applied at fixed mobile phase conditions, several advanced modeling approaches have been developed:

Global LSER models simultaneously incorporate mobile phase composition as a variable, significantly reducing the number of coefficients needed to predict retention across different eluent conditions. For reversed-phase liquid chromatography, a global LSER derived from both the local LSER model and linear solvent strength theory requires only twelve coefficients to model retention across various mobile phase compositions, providing comparable accuracy to multiple local LSER models [23].

Extended LSER models incorporate additional molecular descriptors to address specific analytical challenges. For ionizable compounds, the inclusion of the degree of ionization parameter D significantly improves retention prediction. Recent research has further separated D into D⁺ and D⁻ components that separately account for the ionization of basic and acidic solutes, respectively, marking the first time these terms have been separated in LSER modeling [24].

Table 1: LSER Solute Descriptors and Their Chemical Significance

| Descriptor | Symbol | Molecular Property | Determination Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Excess molar refraction | E | Polarizability of π- and n-electrons | Gas-liquid chromatographic data [21] |

| Dipolarity/Polarizability | S | Dipole-dipole and dipole-induced dipole interactions | Water-solvent partition coefficients [21] |

| Hydrogen-bond acidity | A | Hydrogen-bond donating ability | Calculated from molecular structure [21] |

| Hydrogen-bond basicity | B | Hydrogen-bond accepting ability | Calculated from molecular structure [21] |

| McGowan characteristic volume | V | Molecular size | Gas-liquid chromatographic data [21] |

Applications in Separation Science

Method Development and Optimization