Life Cycle Assessment for Chemical Processes: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) specifically tailored for researchers, scientists, and professionals in chemical and pharmaceutical development.

Life Cycle Assessment for Chemical Processes: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) specifically tailored for researchers, scientists, and professionals in chemical and pharmaceutical development. It covers the foundational principles of LCA as standardized by ISO 14040 and 14044, explores advanced methodological approaches like prospective and dynamic LCA, and addresses key challenges in data quality and system boundaries. The content details practical applications in green chemistry and process optimization, illustrates validation through comparative case studies, and discusses the integration of emerging technologies such as AI and blockchain to enhance assessment accuracy and transparency. Aimed at supporting sustainable product design and regulatory compliance, this guide synthesizes current trends and future directions to empower innovation in biomedical and clinical research.

LCA Foundations: Principles and Relevance for the Chemical Industry

Defining Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) and Its Scientific Framework

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is a systematic, science-based methodology for evaluating the environmental impacts associated with a product, process, or service across its entire life cycle [1]. This comprehensive approach considers all stages from raw material extraction ("cradle") to manufacturing, distribution, use, and final disposal ("grave") [2] [3]. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) provides the defining standards for LCA in ISO 14040 and 14044, ensuring consistent, credible, and comparable assessments worldwide [4] [5].

In the context of chemical processes research, LCA has evolved from a simple environmental accounting tool to an essential framework for guiding sustainable innovation [6]. It enables researchers and drug development professionals to quantify environmental trade-offs, identify improvement opportunities, and make scientifically-grounded decisions that align with the principles of green chemistry [6]. By adopting LCA early in the research and development phase, scientists can design chemical processes and pharmaceuticals that are "benign by design," effectively reducing environmental impacts before they become embedded in final products [6] [7].

The Scientific Framework of LCA

The LCA framework is structured into four interdependent phases that ensure methodological rigor and comprehensive assessment. The dynamic relationship between these phases allows for iterative refinement as new data becomes available or system boundaries are adjusted [2].

Phase 1: Goal and Scope Definition

The initial phase establishes the study's purpose, boundaries, and depth of analysis. For chemical processes research, this requires precise definition of the system boundaries (e.g., cradle-to-gate for intermediate chemicals or cradle-to-grave for final pharmaceutical products) and the functional unit that quantifies the performance characteristic being studied [2] [8] [3]. This phase determines which processes and impact categories will be included, ensuring the assessment addresses the specific decisions it intends to inform [8].

Table: Key Elements in Goal and Scope Definition for Chemical LCAs

| Element | Description | Chemical Research Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Functional Unit | Quantified description of the system's function | e.g., "1 kg of active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) at 99.9% purity" |

| System Boundaries | Processes included in the assessment | Often "cradle-to-gate" for intermediate chemicals; "cradle-to-grave" for consumer products |

| Impact Categories | Environmental issues evaluated | Global warming, resource depletion, human toxicity, ecotoxicity |

| Data Quality Requirements | Specifications for temporal, geographical, and technological representativeness | Primary data for foreground processes; secondary data for background processes |

Phase 2: Life Cycle Inventory (LCI)

The Life Cycle Inventory phase involves detailed compilation and quantification of all relevant inputs and outputs associated with the product system [1] [8]. For chemical processes, this includes:

- Resource consumption: Raw materials, energy, water, and ancillary materials

- Emissions to air, water, and soil: Greenhouse gases, volatile organic compounds, heavy metals, and other pollutants

- Products and co-products: Main products, intermediate products, and waste streams [8]

Data collection should prioritize primary data from laboratory or pilot-scale processes, supplemented by secondary data from commercial LCI databases when necessary [8] [3]. In chemical research, particular attention must be paid to stoichiometry, reaction yields, catalyst usage and recovery, solvent selection, and energy intensity of separation processes [6].

Phase 3: Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA)

Life Cycle Impact Assessment translates inventory data into potential environmental impacts using standardized characterization methods [1] [8]. This phase typically involves:

- Classification: Assigning LCI results to relevant impact categories

- Characterization: Modeling LCI results within category indicator results [8]

For chemical processes, critical impact categories include global warming potential (GWP), human toxicity, ecotoxicity, resource depletion, and water use [5]. The LCIA phase applies characterization factors to convert emissions into common equivalents (e.g., kg CO₂-eq for GWP) [8].

Table: Core Impact Categories for Chemical Process LCA

| Impact Category | Indicator | Common Units | Chemical Sector Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Warming Potential | Climate change | kg CO₂-equivalent | High - Energy-intensive processes |

| Acidification Potential | Terrestrial/marine acidification | kg SO₂-equivalent | Medium - Combustion emissions |

| Eutrophication Potential | Nutrient over-enrichment | kg PO₄³⁻-equivalent | Medium - Wastewater discharges |

| Human Toxicity Potential | carcinogenic/non-carcinogenic effects | kg 1,4-DCB-equivalent | High - Chemical exposure risks |

| Ecotoxicity Potential | Freshwater/marine/terrestrial toxicity | kg 1,4-DCB-equivalent | High - Chemical emissions |

| Resource Depletion | Abiotic resource depletion | kg Sb-equivalent | High - Catalyst and material use |

Phase 4: Interpretation

The interpretation phase involves evaluating the results from both the LCI and LCIA phases to formulate conclusions, explain limitations, and provide recommendations [2] [3]. For chemical researchers, this includes:

- Hotspot identification: Determining which processes or substances contribute most significantly to environmental impacts

- Sensitivity analysis: Testing how results change with variations in key parameters

- Uncertainty analysis: Quantifying confidence in the final results [6]

- Improvement assessment: Identifying opportunities to reduce environmental impacts

This phase should deliver actionable insights that inform research direction, process optimization, and material selection decisions [3].

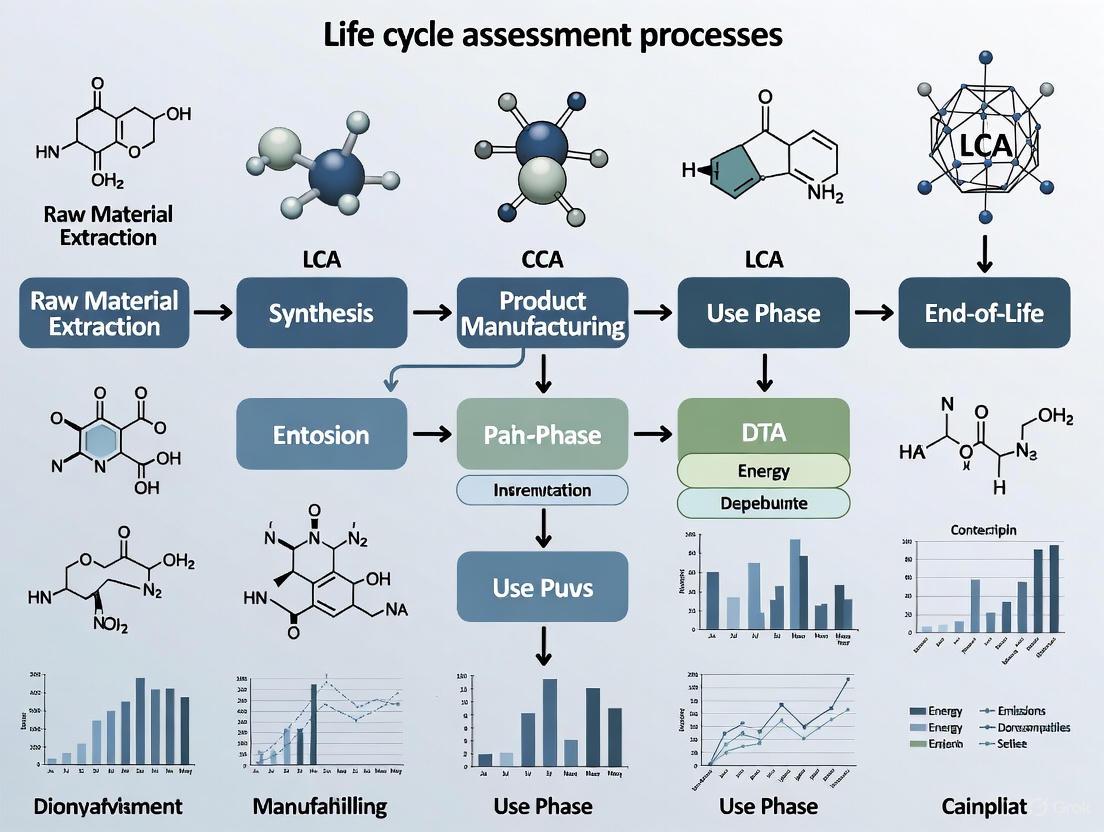

LCA Workflow for Chemical Processes

The following diagram illustrates the standardized LCA workflow adapted for chemical processes research, incorporating critical decision points specific to the chemical sector:

Application Notes for Chemical Research

Protocol 1: streamlined LCA for early-stage chemical process development

Purpose: To conduct a rapid environmental assessment of novel chemical synthesis routes during early research phases when complete data may be limited.

Methodology:

- Goal and Scope: Define functional unit as mass of primary product (e.g., 1 kg API). Use cradle-to-gate system boundaries excluding use and disposal phases. Include raw material production, energy use, and direct process emissions [6].

- Inventory Analysis:

- Collect experimental data on reaction stoichiometry, yields, and identified inputs/outputs

- Use laboratory measurements for energy consumption in key process steps

- Apply chemical engineering principles to estimate data gaps (e.g., solvent recovery rates)

- Document all assumptions and estimation methods transparently [6] [7]

- Impact Assessment: Focus on 3-5 critical impact categories: Global Warming Potential, Resource Depletion, Human Toxicity, and Ecotoxicity. Use simplified characterization methods appropriate for screening assessments.

- Interpretation: Identify environmental hotspots (e.g., energy-intensive separation steps, hazardous solvents) to guide research toward more sustainable alternatives.

Data Quality Requirements: Primary data for foreground processes; industry-average data for common chemicals and energy; documented assumptions for estimated parameters.

Protocol 2: comparative LCA of chemical synthesis routes

Purpose: To evaluate the environmental trade-offs between different synthetic pathways for the same target molecule.

Methodology:

- Goal and Scope: Define consistent functional unit and system boundaries across all alternatives. Include all major process steps from raw material extraction to purified product.

- Inventory Analysis:

- Develop detailed mass and energy balances for each route

- Account for catalyst lifetimes and recycling rates

- Include solvent production and recovery/reclamation processes

- Consider byproduct formation and treatment requirements [6]

- Impact Assessment: Apply full LCIA covering all relevant impact categories. Use consistent impact assessment method (e.g., ReCiPe or EF 3.0).

- Interpretation: Conduct contribution analysis to identify drivers of environmental impacts. Perform sensitivity analysis on key parameters (e.g., energy source, solvent recovery efficiency).

Special Considerations: Ensure compared routes produce chemically and functionally equivalent products. Address allocation methods for multi-output processes.

Essential Research Reagents and Materials for LCA Implementation

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Chemical Process LCA

| Reagent/Material | Function in LCA Protocol | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| LCA Software (e.g., Umberto) | Modeling and calculation of life cycle impacts | Enables complex system modeling; includes database integration; essential for comprehensive assessments [5] |

| Life Cycle Inventory Databases | Provision of secondary data for background processes | Sources: ecoinvent, GaBi, US LCI; provide data on chemicals, energy, materials; critical for cradle-to-gate assessments [5] |

| Chemical Process Simulation Tools | Generation of energy and mass balance data | Tools: Aspen Plus, ChemCAD; provide inventory data for chemical processes; especially valuable for scale-up assessments |

| Impact Assessment Methods | Translation of inventory data into environmental impacts | Methods: ReCiPe, CML, TRACI; contain characterization factors for impact categories; selection depends on geographic context [3] |

| Laboratory Analytical Equipment | Quantification of emissions and resource consumption | GC-MS, ICP-MS for chemical emissions; energy meters for process electricity; provides primary data for inventory |

Advanced Methodological Considerations

Dynamic LCA for Chemical Processes

Traditional "static" LCA assessments provide a snapshot of environmental impacts under specific conditions. Dynamic LCA incorporates temporal variations in factors such as energy grid composition, technological learning, and time-dependent characterization factors, particularly relevant for chemicals with long-term degradation profiles or persistent environmental impacts [9]. In chemical research, this approach is valuable for assessing processes where:

- Energy sources are expected to decarbonize over the technology lifetime

- Chemical degradation occurs over extended timeframes

- Feedstock sources may shift (e.g., bio-based vs petroleum-based) [9]

LCSA: Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment

Going beyond environmental impacts, Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment (LCSA) integrates three pillars of sustainability:

- Environmental LCA (as described in this document)

- Life Cycle Costing (LCC) for economic assessment

- Social LCA (S-LCA) for social impacts [10]

For chemical processes, this comprehensive approach enables researchers to evaluate trade-offs between environmental benefits, economic viability, and social implications such as labor conditions in the supply chain or community health impacts [10].

Life Cycle Assessment provides an essential scientific framework for evaluating and improving the environmental performance of chemical processes and pharmaceutical development. By systematically applying LCA methodologies throughout research and development, scientists can identify environmental hotspots, guide innovation toward more sustainable pathways, and make quantitatively-supported decisions that align with green chemistry principles. The standardized four-phase framework—Goal and Scope Definition, Inventory Analysis, Impact Assessment, and Interpretation—ensures rigorous, comprehensive, and comparable assessments that effectively support the transition toward more sustainable chemical industry practices.

The ISO 14040 and 14044 standards, established by the International Organization for Standardization, provide the internationally recognized framework and requirements for conducting Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) studies [11]. These standards offer a systematic approach to evaluating the environmental aspects and potential impacts associated with a product, process, or service throughout its entire life cycle – from raw material extraction (cradle) to final disposal (grave) [12] [2].

For researchers in chemical processes and drug development, these standards provide the scientific rigor and methodological consistency necessary for credible environmental impact assessment. The framework enables comparative assertions between chemical synthesis pathways and facilitates identification of environmental "hotspots" within complex manufacturing processes [12]. The standards were significantly updated in 2006, consolidating previous separate documents (ISO 14041, 14042, and 14043) into the two current standards [13]. Since then, they have undergone minor amendments, with the latest published in 2020 [14] [15].

Table: Core ISO LCA Standards and Their Roles in Chemical Process Research

| Standard | Focus | Relevance to Chemical Research |

|---|---|---|

| ISO 14040:2006 | Principles and framework for LCA | Provides overarching structure for LCA studies without specifying detailed methodologies [15] |

| ISO 14044:2006 | Requirements and guidelines for LCA | Specifies detailed requirements for each LCA phase and critical review process [14] |

| ISO 14067 | Carbon footprint of products | Guides quantification of climate change impacts specifically, relevant for chemical carbon accounting [16] |

| ISO/TS 14072 | Organizational LCA | Provides requirements for applying LCA at organizational level, including chemical manufacturing facilities [17] |

The Four-Phase LCA Methodology

The ISO 14040/14044 framework structures LCA into four interdependent phases that ensure scientific robustness and comprehensive assessment [11] [18]. The relationship between these phases is iterative, with interpretation occurring throughout the process to refine the assessment [2].

LCA Framework with Iterative Interpretation Phase

Phase 1: Goal and Scope Definition

The goal and scope definition establishes the foundation of the LCA study by clearly articulating its purpose, intended application, and audience [18]. For chemical process research, this phase requires precise definition of:

Functional Unit: A quantitatively defined performance metric that serves as a reference for all input and output calculations (e.g., "per kilogram of active pharmaceutical ingredient" or "per molar equivalent of reaction product") [12]. This enables valid comparisons between alternative chemical synthesis pathways.

System Boundaries: Determination of which unit processes and life cycle stages to include in the assessment [2]. For chemical processes, this typically includes raw material acquisition, catalyst synthesis, reaction processes, purification steps, energy generation, transportation, and waste treatment operations.

Impact Categories: Selection of environmental impact categories relevant to the specific chemical system being studied, such as global warming potential, eutrophication, acidification, and human toxicity [18].

Table: Chemical Process LCA System Boundary Considerations

| Boundary Element | Inclusion Rationale | Data Collection Challenges |

|---|---|---|

| Raw material extraction | Determines resource depletion impacts | Upstream supplier data often proprietary |

| Catalyst synthesis | Significant for precious metal catalysts | Complex synthesis pathways with multiple steps |

| Solvent production and recovery | Major contributor to overall footprint | Recovery rates vary with process efficiency |

| Energy generation | Directly impacts GHG emissions | Grid composition varies geographically |

| Transportation | Contributes to particulate matter formation | Distance and mode significantly vary impacts |

| Waste treatment | Determines end-of-life impacts | Fate of chemicals in treatment uncertain |

Phase 2: Life Cycle Inventory (LCI)

The Life Cycle Inventory phase involves the compilation and quantification of inputs (energy, materials, water) and outputs (emissions, waste) for each process within the defined system boundaries [18] [12]. For chemical researchers, this represents the most data-intensive phase of the LCA.

Experimental Protocol: Primary Data Collection for Chemical Inventory

- Material Inputs Tracking: Document all raw materials, catalysts, solvents, and reagents used in synthetic pathways with precise mass balances

- Energy Consumption Monitoring: Direct measurement of electricity, steam, and heating/cooling requirements for each unit operation

- Air Emissions Quantification: Use appropriate analytical methods (GC-MS, FTIR) to characterize volatile organic compounds, greenhouse gases, and acid gases

- Water Effluent Analysis: Characterize aqueous waste streams for organic content (COD, BOD), heavy metals, and specific chemical residues

- Solid Waste Characterization: Quantify and classify all solid residues, spent catalysts, and filtration media

When primary data is unavailable, researchers may supplement with secondary sources such as:

- Commercial LCA databases (Ecoinvent, GaBi)

- Peer-reviewed literature on similar chemical processes

- Engineering estimates based on stoichiometry and reaction kinetics

Phase 3: Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA)

The Life Cycle Impact Assessment phase translates inventory data into potential environmental impacts using scientifically established characterization factors [18] [12]. This phase provides the critical link between inventory data and their potential contributions to specific environmental problems.

Experimental Protocol: Impact Assessment for Chemical Processes

- Classification: Assign inventory flows to impact categories (e.g., CO₂ to climate change, NOₓ to acidification)

- Characterization: Calculate category indicator results using characterization factors (e.g., converting various greenhouse gases to CO₂ equivalents using IPCC factors)

- Normalization (optional): Express results relative to a reference system (e.g., regional or global total emissions)

- Weighting (optional): Assign relative importance to different impact categories based on value choices

Table: Key Impact Categories for Chemical Process Assessment

| Impact Category | Indicator | Relevance to Chemical Processes | Common Characterization Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Warming | kg CO₂-equivalent | Energy-intensive reactions, GHG emissions | IPCC factors |

| Acidification | kg SO₂-equivalent | Acid gas emissions (SOₓ, NOₓ) | Accumulated Exceedance |

| Eutrophication | kg PO₄³⁻-equivalent | Nutrient releases in wastewater | EUTREND model |

| Human Toxicity | kg 1,4-DCB-equivalent | Hazardous chemical exposure | USEtox model |

| Ecotoxicity | kg 1,4-DCB-equivalent | Aquatic and terrestrial contamination | USEtox model |

| Resource Depletion | kg Sb-equivalent | Catalyst metals, rare earth elements | CML method |

Phase 4: Interpretation

The interpretation phase evaluates the results of the inventory and impact assessment in relation to the study's goal and scope [11] [18]. For chemical researchers, this phase identifies significant issues, conducts sensitivity and uncertainty analyses, and draws conclusions supported by the evidence.

Experimental Protocol: Uncertainty and Sensitivity Analysis

- Data Quality Assessment: Evaluate precision, completeness, and representativeness of key data inputs using pedigree matrix approaches

- Monte Carlo Simulation: Perform statistical uncertainty analysis to determine confidence intervals around impact results

- Sensitivity Analysis: Systematically vary key parameters (e.g., reaction yield, solvent recovery rate) to identify most influential factors

- Hotspot Identification: Pinpoint processes contributing most significantly to overall environmental impacts

LCA Standards Hierarchy and Chemical Industry Applications

The ISO 14040/14044 standards form the foundation of a hierarchical structure of LCA standards, with more specific standards building upon these general frameworks [11]. For chemical researchers, understanding this hierarchy is essential for selecting appropriate methodologies.

Hierarchy of LCA Standards with Increasing Specificity

Chemical Industry-Specific Applications

The Together for Sustainability (TfS) initiative has developed specific guidance for applying LCA to chemical processes, building upon the ISO 14040/14044 foundation [16]. These guidelines provide:

- Allocation Methods: Specific procedures for allocating environmental impacts between co-products in complex chemical synthesis pathways, including mass, energy, and economic allocation approaches

- Calculation Requirements: Standardized approaches for calculating carbon footprints of chemical products, particularly important for pharmaceutical intermediates

- Verification Protocols: Third-party verification requirements ensuring credibility of environmental claims for chemical products

- Reporting Frameworks: Mandatory reporting elements for chemical industry LCA studies, with specific implementation timelines

Implementation of ISO 14040/14044-compliant LCA in chemical research requires specific tools and resources to ensure methodological rigor and efficiency.

Table: Essential LCA Research Tools for Chemical Applications

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Application in Chemical LCA |

|---|---|---|

| LCA Software | SimaPro, OpenLCA, GaBi | Modeling complex chemical systems and supply chains |

| Chemical Databases | Ecoinvent, USDA LCA Commons | Background data on chemical precursors and energy systems |

| Impact Assessment Methods | ReCiPe, TRACI, CML | Characterizing chemical-specific impact pathways |

| Uncertainty Analysis Tools | Monte Carlo simulation, @RISK | Quantifying reliability of LCA results for chemical processes |

| Data Quality Assessment | Pedigree matrix, Data Quality Indicators | Evaluating reliability of chemical process data |

Experimental Protocol: Third-Party Critical Review

For LCA studies intended to support comparative assertions disclosed to the public, ISO 14044 requires a critical review by independent external experts [14]. The protocol includes:

- Review Panel Formation: Selection of at least three independent LCA practitioners with relevant chemical industry expertise

- Methodology Assessment: Evaluation of goal and scope definition, data quality, methodology choices, and interpretation approaches

- Compliance Verification: Confirmation that the study meets all ISO 14044 requirements for chemical process LCA

- Report Preparation: Documentation of review process, findings, and conclusions regarding study validity

ISO 14040 and 14044 provide the essential framework for conducting scientifically robust and internationally recognized life cycle assessments of chemical processes and pharmaceutical development. The standardized four-phase methodology enables consistent evaluation and comparison of environmental impacts across different synthesis pathways and manufacturing technologies. For researchers, adherence to these standards ensures that environmental assessments meet the highest standards of scientific rigor while providing actionable insights for sustainable chemical design. The iterative nature of the framework allows for continuous refinement as new data and methodologies emerge, maintaining its relevance as the gold standard for environmental impact assessment in chemical research.

Why LCA is Critical for Chemical Processes and Pharmaceutical Development

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) has emerged as an indispensable methodology for quantifying and mitigating environmental impacts in pharmaceutical development and chemical processes. Unlike traditional green metrics that focus narrowly on mass efficiency, LCA provides a comprehensive, data-driven framework for evaluating cumulative environmental effects across all stages of a product's life cycle. This application note details standardized LCA protocols, experimental workflows, and critical reagent solutions to enable researchers and drug development professionals to implement robust sustainability assessments, identify environmental hotspots in synthesis routes, and advance greener pharmaceutical manufacturing.

The pharmaceutical industry faces unique sustainability challenges due to complex multi-step syntheses of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) that typically involve resource-intensive processes and substantial chemical usage [19]. Traditional green chemistry metrics—such as Process Mass Intensity (PMI), E-factor, and atom economy—provide valuable but limited insights, focusing primarily on mass efficiency without accounting for broader environmental consequences [20].

LCA addresses these limitations through its holistic cradle-to-gate framework that evaluates impacts from raw material extraction through API manufacturing [2]. Recent studies of pharmaceutical processes identify energy consumption (particularly electricity use) and chemical application as the two most significant contributors to environmental impacts, underscoring the critical need for systematic assessment methods [19]. The implementation of LCA enables researchers to make informed decisions that balance synthetic efficiency with environmental responsibility, ultimately supporting the industry's transition toward sustainable manufacturing paradigms.

LCA Versus Traditional Metrics: A Quantitative Comparison

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Sustainability Assessment Methods

| Assessment Method | Scope of Evaluation | Key Metrics | Pharmaceutical Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) | Cradle-to-gate: raw material extraction, manufacturing, transportation, use, disposal [2] | Global Warming Potential (GWP), Ecosystem Quality (EQ), Human Health (HH), Natural Resources (NR) [20] | API synthesis route comparison, environmental hotspot identification, supply chain optimization [19] [20] | Data-intensive, requires specialized expertise, time-consuming [21] [22] |

| Process Mass Intensity (PMI) | Mass efficiency of synthetic route only [20] | Total mass in per mass API out [20] | Rapid benchmarking of synthetic efficiency during route scouting | Excludes environmental impact of materials, energy use [20] |

| E-Factor | Waste production within manufacturing process [20] | Mass waste per mass product [20] | Process optimization to minimize waste generation | Does not differentiate between benign and hazardous waste [20] |

| Atom Economy | Theoretical efficiency of molecular incorporation [20] | Molecular weight of product vs. reactants [20] | Reaction design and selection | Theoretical calculation ignoring reagents, solvents, reaction yield [20] |

LCA's distinctive value emerges from its ability to convert inventory data into multiple environmental impact categories, providing a multidimensional perspective that reveals trade-offs and synergies between different sustainability objectives [20]. For example, a synthesis route with favorable PMI might utilize reagents with energy-intensive production pathways, resulting in higher overall global warming potential—a critical insight only detectable through comprehensive LCA methodology.

Standardized LCA Framework and Environmental Impact Categories

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) provides standardized frameworks for LCA through ISO 14040 and 14044, which define four iterative phases [4] [2] [22]:

- Goal and Scope Definition: Establishing the study's purpose, system boundaries, and functional unit

- Life Cycle Inventory Analysis: Compiling quantitative input/output data

- Impact Assessment: Evaluating potential environmental consequences

- Interpretation: Analyzing results and drawing conclusions

Table 2: Key Environmental Impact Categories in Pharmaceutical LCA

| Impact Category | Representation | Significance in Pharmaceutical Context | Primary Contributors in API Synthesis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Warming Potential (GWP) | kg CO₂-equivalent [20] | Climate change impact from greenhouse gases | Energy consumption, solvent production, fossil-based feedstocks [19] |

| Human Health (HH) | Comparative risk units [20] | Toxicological effects on human populations | API intermediates, hazardous reagents, solvent emissions [19] |

| Ecosystem Quality (EQ) | Species loss per area [20] | Ecological damage and biodiversity loss | Effluents, resource extraction, land use [20] |

| Natural Resources (NR) | MJ surplus energy [20] | Depletion of non-renewable resources | Solvent consumption, metal catalysts, fossil energy [19] [20] |

Experimental Protocol: LCA-Guided Synthesis Route Assessment

Workflow for Comparative Analysis of API Synthesis Routes

Step-by-Step Procedure

Phase 1: Goal and Scope Definition

- Functional Unit Establishment: Define the study's reference unit, typically 1 kg of final API [20]

- System Boundaries: Specify cradle-to-gate boundaries encompassing raw material acquisition through API synthesis, excluding use phase and disposal [2]

- Impact Categories Selection: Identify relevant environmental impact categories based on study goals (Table 2)

Phase 2: Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) Compilation

- Data Collection Protocol: For each synthesis step, document exact masses of all inputs (reactants, catalysts, solvents, energy) and outputs (product, waste) [20]

- Data Sources Priority:

- Primary experimental data from laboratory or pilot-scale synthesis

- Process mass balances from development reports

- Supplier-specific environmental data

- Database proxies (ecommerce) for missing inventory items [20]

- Data Quality Assessment: Evaluate uncertainty, completeness, and temporal/geographical representativeness

Phase 3: Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA)

- Calculation Method: Utilize standardized impact assessment methods (ReCiPe 2016) to convert LCI data into environmental impact scores [20]

- Normalization and Weighting: Optionally normalize results to reference values for contextual interpretation

Phase 4: Interpretation and Decision-Support

- Hotspot Identification: Rank process steps and materials contributing most significantly to environmental impacts

- Scenario Analysis: Compare alternative synthesis routes, reagents, or energy sources

- Sensitivity Analysis: Test influence of uncertain parameters on overall conclusions

Case Study: LCA Application in Letermovir Synthesis

A recent comparative LCA study of the antiviral drug Letermovir demonstrates LCA's critical role in pharmaceutical process optimization [20]. The analysis revealed significant environmental hotspots in both established and novel synthesis routes:

Table 3: Environmental Hotspot Analysis in Letermovir Synthesis

| Synthesis Route | Identified Environmental Hotspot | LCA-Revealed Impact | Sustainable Alternative |

|---|---|---|---|

| Published Merck Route | Pd-catalyzed Heck cross-coupling [20] | High energy consumption and resource depletion | Not specified in study |

| De Novo Synthesis Route | Enantioselective Mukaiyama-Mannich addition using chiral Brønsted-acid catalysis [20] | Significant global warming potential and ecosystem quality impacts | Pummerer rearrangement for aldehyde oxidation [20] |

| Early Exploratory Route | LiAlH₄ reduction in initial step [20] | Substantial human health and resource depletion impacts | Boron-based reduction of anthranilic acid [20] |

The LCA provided critical insights that extended beyond traditional green metrics, demonstrating that solvent volumes for purification represented a significant environmental burden in both routes—a finding that might be overlooked in conventional PMI-focused assessments [20]. This case study exemplifies how LCA enables researchers to make environmentally-informed decisions during synthetic route selection and optimization.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Critical LCA Research Reagents and Resources

| Tool/Resource | Function/Application | Implementation Context |

|---|---|---|

| ecoinvent Database | Primary source for life cycle inventory data [20] | Background data for common chemicals, energy sources, and materials |

| Brightway2 LCA Software | Python-based framework for LCA calculations [20] | Customizable impact assessments and scenario modeling |

| Retrosynthetic LCI Protocol | Bridging data gaps for novel chemicals [20] | Building life cycle inventory for intermediates absent from databases |

| ACS GCI Pharmaceutical Roundtable Tools | Sector-specific impact assessment methods [20] | Pharmaceutical-specific LCA applications and benchmarking |

| Web-Based Contrast Checkers | Digital accessibility compliance verification [23] [24] | Ensuring visualizations meet WCAG guidelines for color contrast |

LCA Implementation Challenges and Solutions

Despite its demonstrated value, LCA implementation in pharmaceutical research faces several practical challenges:

- Data Availability Gap: Limited LCI data for novel or complex chemical intermediates [20]

- Methodological Complexity: Requirement for specialized expertise in LCA methodology [21]

- Resource Intensity: Significant time and computational requirements for comprehensive assessments [22]

The iterative retrosynthetic approach demonstrated in the Letermovir case study provides a robust solution to data limitations, systematically building life cycle inventories for undocumented chemicals through published synthetic pathways [20]. This methodology enabled the researchers to increase database coverage from approximately 20% to comprehensive inclusion of all synthesis components, establishing a replicable framework for LCA applications in complex molecule synthesis.

Life Cycle Assessment represents a paradigm shift in sustainable pharmaceutical development, moving beyond traditional mass-based metrics to provide multidimensional environmental insights across the complete chemical process landscape. The standardized protocols, experimental workflows, and analytical frameworks presented in this application note equip researchers with practical methodologies to integrate LCA into pharmaceutical development pipelines. As the industry faces increasing pressure to minimize its environmental footprint, LCA emerges as a critical tool for identifying improvement opportunities, guiding sustainable decision-making, and advancing the development of greener pharmaceutical manufacturing processes.

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is a systematic, scientific methodology used to evaluate the environmental impacts associated with all stages of a product's life cycle, from raw material extraction to disposal, use, or recycling [4]. Governed by internationally recognized ISO 14040 and 14044 standards, LCA provides data-driven insights that enable researchers and industry professionals to make informed sustainability decisions [4] [25]. In the context of chemical processes and drug development, LCA has evolved from a mere environmental assessment tool to a strategic framework that drives innovation, cost reduction, and regulatory compliance.

For researchers in chemical and pharmaceutical sciences, LCA offers a powerful tool to quantify the environmental footprint of processes and products, supporting the principles of green chemistry and benign-by-design approaches [6]. The methodology is particularly valuable for identifying hidden inefficiencies in complex supply chains, optimizing resource-intensive manufacturing processes, and meeting stringent regulatory requirements for sustainable product development [4] [25].

LCA Application Framework in Chemical and Pharmaceutical Research

Foundational LCA Principles for Chemical Processes

The application of LCA to chemical processes requires adherence to specialized principles that address the unique characteristics of chemical synthesis and pharmaceutical development. Cespi (2025) proposes twelve fundamental principles for LCA of chemicals that provide a procedural framework for researchers [6]:

- Cradle to Gate: System boundaries should encompass at minimum from raw material extraction to production finish

- Consequential if Under Control: Employ consequential LCA when assessing system changes

- Avoid to Neglect: Prevent overlooking environmentally relevant processes

- Data Collection from the Beginning: Implement comprehensive data gathering from research initiation

- Different Scales: Account for variations in process scales

- Data Quality Analysis: Ensure rigorous assessment of data reliability

- Multi-impact: Evaluate multiple environmental impact categories

- Hotspot: Identify critical points for environmental improvement

- Sensitivity: Conduct sensitivity analyses to test result robustness

- Results Transparency, Reproducibility and Benchmarking: Maintain open, reproducible methods with comparative standards

- Combination with Other Tools: Integrate LCA with complementary methodologies

- Beyond Environment: Extend analysis to social and economic dimensions

These principles provide chemical researchers with a structured approach to incorporating life cycle thinking throughout the research and development process, enabling early identification of environmental hotspots and opportunities for sustainable innovation [6].

LCA Methodological Workflow

The standardized LCA methodology comprises four distinct phases that create a systematic framework for environmental assessment. The process begins with goal and scope definition, followed by inventory analysis, impact assessment, and finally interpretation, with iterative refinement possible between stages [4].

Figure 1: LCA Methodological Framework according to ISO 14040/14044 Standards

Quantitative Benefits of LCA Implementation

Supply Chain Optimization Benefits

The integration of LCA with Supply Chain Optimization (SCO) creates a powerful approach for developing supply chains that are both economically efficient and environmentally sustainable [26]. Traditional approaches treat LCA and SCO as separate, sequential steps, leading to inconsistencies in scope and challenges in data transfer. The novel Supply Chain Life Cycle Optimization (SCLCO) model addresses these limitations through a unified framework that simultaneously considers environmental, economic, and social pillars of sustainability [26].

Table 1: LCA-Driven Supply Chain Optimization Benefits

| Benefit Category | Research Application | Quantitative Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Resource Efficiency | Identification of resource-intensive processes in API synthesis | Reduction in raw material consumption through alternative pathways |

| Logistics Optimization | Environmental assessment of transportation modes for chemical distribution | Lower carbon emissions through route and mode optimization |

| Supplier Selection | Comparative LCA of raw material sources | Identification of suppliers with lowest environmental footprint |

| Waste Reduction | Process mass intensity calculations for chemical reactions | Minimization of solvent use and hazardous waste generation |

LCA enables pharmaceutical companies to uncover hidden inefficiencies in their supply chains, from raw material sourcing to transportation emissions [4]. For instance, a comparative analysis of suppliers might reveal that a particular reagent's synthesis pathway is more carbon-intensive than alternatives, enabling researchers to select more sustainable sources without compromising quality [4] [25].

Regulatory Compliance and Risk Mitigation

The regulatory landscape for chemical and pharmaceutical products is increasingly incorporating sustainability requirements. LCA provides the methodological foundation for compliance with emerging regulations and standards [4] [25].

Table 2: LCA Applications in Regulatory Compliance

| Regulatory Area | LCA Application | Research Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Chemicals of Concern (CoCs) | Assessment of PFAS, benzene, nitrosamines in pharmaceuticals | Analytical quantification coupled with impact assessment [27] |

| Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) | End-of-life impact evaluation for drug delivery devices | Disposal scenario analysis including incineration, recycling [28] |

| EU Green Deal & ESPR | Product Environmental Footprint (PEF) calculations | Standardized LCA following PEFCR guidelines [29] |

| FDA Sustainability Guidelines | Environmental risk assessment for new drug applications | Cradle-to-gate LCA with focus on manufacturing impacts [25] |

The integration of LCA in regulatory compliance is particularly crucial for pharmaceutical companies operating in global markets, where requirements may differ significantly by region [27]. For example, the European Union's Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation (ESPR) requires detailed environmental product information, which LCA can comprehensively provide [29].

Experimental Protocols for LCA in Chemical Research

Protocol 1: Cradle-to-Gate LCA for Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs)

Objective: To conduct a comprehensive cradle-to-gate LCA of an active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) for identifying environmental hotspots and improvement opportunities.

Materials and Reagents:

- Primary production data for API synthesis

- Ecoinvent or similar LCA database for background processes

- LCA software (OpenLCA, SimaPro, or GaBi)

- Chemical inventory data (solvents, catalysts, reagents)

Methodology:

- Goal and Scope Definition

- Define functional unit (e.g., 1 kg of purified API)

- Establish system boundaries from raw material extraction to purified API

- Determine cut-off criteria and allocation methods

Life Cycle Inventory (LCI)

- Collect primary data on material/energy inputs for each synthesis step

- Obtain upstream data for chemicals from LCA databases

- Quantify emissions and waste streams for each process step

- Document data sources and quality indicators

Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA)

- Select impact categories relevant to pharmaceuticals (global warming, human toxicity, ecotoxicity, water use)

- Calculate category indicator results using LCIA methods (ReCiPe, EF)

- Conduct contribution analysis to identify environmental hotspots

Interpretation

- Evaluate significant issues based on LCI and LCIA results

- Conduct sensitivity analysis of critical parameters

- Develop conclusions and recommendations for process optimization

Validation: Compare results with similar API LCAs from literature; perform peer review following ISO 14044 requirements.

Protocol 2: Comparative LCA of Drug Delivery Devices

Objective: To evaluate the environmental impacts of alternative drug delivery device designs and identify opportunities for sustainable design improvements.

Materials and Reagents:

- Design specifications for drug delivery devices

- Material composition data (plastics, metals, electronics)

- Manufacturing process energy data

- Transportation and end-of-life scenario data

Methodology:

- Goal and Scope Definition

- Define functional unit (e.g., delivery of 1,000 doses)

- Establish cradle-to-grave system boundaries

- Identify comparison scenarios (e.g., single-use vs. reusable devices)

Life Cycle Inventory

- Quantify materials for device components

- Calculate manufacturing energy consumption

- Model distribution logistics and transportation

- Define use phase assumptions (sterilization, storage)

- Specify end-of-life pathways (recycling, incineration, landfill)

Impact Assessment

- Apply impact assessment method (ILCD, CML, or ReCiPe)

- Focus on climate change, resource depletion, and human toxicity

- Conduct hotspot analysis to identify major contributors

Interpretation

- Compare results across device designs

- Perform sensitivity analysis on critical parameters (reuse cycles, recycling rates)

- Formulate design recommendations for environmental improvement

Case Study Application: Owen Mumford's eco-design tool for medical devices exemplifies this approach, enabling assessment of how material choice, component weights, manufacturing location, and end-of-life scenarios affect environmental performance [28].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for LCA Studies

| Tool Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| LCA Software | OpenLCA, SimaPro, GaBi | Modeling life cycle inventory and impact assessment |

| LCA Databases | Ecoinvent, GLAD, USLCI | Background data for chemicals, energy, materials |

| Impact Assessment Methods | ReCiPe, EF, TRACI | Calculating environmental impact indicators |

| Chemical Assessment | GREENSCOPE, CHEMSHARE | Evaluating chemical process sustainability |

| Pharmaceutical LCA Data | API LCA datasets, Pharma-LCA | Industry-specific background data |

The Global LCA Data Access (GLAD) network is particularly valuable for researchers, providing an open scientific data node that hosts LCA datasets from multiple academic sources [30]. For pharmaceutical applications, the Ecoinvent database contains specialized datasets for chemical synthesis processes that can be adapted to model API production.

Integrated LCA Workflow for Chemical Process Design

The integration of LCA into chemical process design requires a systematic approach that connects laboratory research with sustainability assessment. The following workflow illustrates how LCA can be embedded throughout the research and development process for chemical processes and pharmaceuticals.

Figure 2: Integrated LCA Workflow for Chemical Process Design and Optimization

This integrated approach enables researchers to identify environmental hotspots early in the development process, when changes are most cost-effective to implement. For pharmaceutical applications, this means optimizing synthesis routes, selecting greener solvents, and designing more efficient processes before scale-up, resulting in both environmental and economic benefits [25] [31].

LCA provides researchers in chemical processes and drug development with a powerful, scientifically rigorous framework for quantifying and improving environmental performance. The methodology delivers significant benefits across multiple dimensions, from supply chain optimization and cost reduction to regulatory compliance and market differentiation. By adopting the standardized protocols and tools outlined in this document, researchers can systematically integrate sustainability considerations throughout the product development lifecycle, supporting the transition toward greener chemistry and more sustainable pharmaceutical production.

The future of LCA in chemical research lies in deeper integration with process design tools, expanded databases for specialized chemicals and pharmaceuticals, and increased harmonization with regulatory requirements. As global sustainability pressures intensify, LCA will become an increasingly essential tool for researchers seeking to balance scientific innovation with environmental responsibility.

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) provides a systematic, quantitative methodology for evaluating the environmental impacts of products, processes, and services [32]. For researchers in chemical and pharmaceutical development, LCA offers a crucial decision-support tool for measuring environmental footprint, identifying improvement opportunities, and advancing sustainable manufacturing practices [33]. The framework is standardized internationally through ISO 14040 and 14044, ensuring consistency and credibility across studies [8] [34]. This application note details the experimental protocols for implementing the four LCA stages within chemical process research, providing scientists with structured methodologies for comprehensive environmental impact evaluation.

The Four Stages of Life Cycle Assessment

The LCA methodology comprises four interdependent stages that function as an iterative cycle rather than a linear sequence. The following workflow illustrates the relationships between these stages and their key components:

Stage 1: Goal and Scope Definition

The goal and scope definition establishes the foundation for the entire LCA by defining its purpose, boundaries, and intended application [8] [34].

Experimental Protocol: Goal Definition

- Define Intended Application: Precisely state the LCA's purpose, such as comparing synthetic routes, identifying environmental hotspots in a process, or supporting environmental product declarations (EPDs) [2].

- Identify Target Audience: Determine whether results are for internal R&D decisions, regulatory compliance, or external stakeholder communication [34].

- Specify Decision Context: Clarify whether the study assesses a standalone process or supports comparative assertions intended for public disclosure [32].

Experimental Protocol: Scope Definition

- Define Functional Unit: Establish a quantified measure of the system's performance that serves as the reference basis for all calculations [8]. For chemical processes, this typically relates to a mass unit of product (e.g., per kg of active pharmaceutical ingredient) or a performance-based unit [33].

- Set System Boundaries: Determine which processes are included. For chemical process LCAs, "cradle-to-gate" (raw material to factory gate) is common, though "cradle-to-grave" may be used for consumer products [2] [32].

- Document Critical Assumptions: Explicitly state all assumptions regarding cut-off rules, allocation procedures for multi-output processes, and any excluded life cycle stages [34].

Table 1: System Boundary Considerations for Chemical Process LCA

| Boundary Type | Included Stages | Typical Application in Chemical Research |

|---|---|---|

| Cradle-to-Gate | Raw material extraction, Material processing, Transportation, Manufacturing | Internal process design, Supplier selection, Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs) [2] [1] |

| Gate-to-Gate | Manufacturing processes only | Focused analysis of internal production efficiency, pilot plant evaluation [32] |

| Cradle-to-Grave | All stages including product use and end-of-life disposal | Consumer products, pharmaceuticals with specific use/disposal phases [2] |

| Cradle-to-Cradle | All stages with recycling/repurposing of materials | Circular economy assessments, green chemistry applications [2] |

Stage 2: Life Cycle Inventory (LCI)

The Life Cycle Inventory phase involves the meticulous collection and calculation of all input and output data for the system being studied [8]. This is often the most time- and resource-intensive stage of an LCA [35].

Experimental Protocol: Data Collection Planning

- Create Process Flow Diagram: Develop a detailed diagram identifying all unit processes within the defined system boundaries [35].

- Identify Data Requirements: For each unit process, list all material inputs, energy inputs, products, co-products, and emissions to air, water, and soil [34].

- Develop Data Collection Plan: Assign data quality requirements and specify sources (primary or secondary) for each data point [35].

Experimental Protocol: Data Gathering and Validation

- Collect Primary Data: Where possible, obtain direct measurements from pilot plants, laboratory experiments, or industrial partners. Key data includes material balances, solvent use, energy consumption, catalyst loads, and direct emissions [34] [36].

- Supplement with Secondary Data: For upstream processes (e.g., raw material extraction, energy production) use reputable LCI databases (e.g., Ecoinvent, GaBi) or peer-reviewed literature [34].

- Apply Data Quality Indicators: Assess data for completeness, temporal, geographical, and technological representativeness [34].

- Conduct Mass and Energy Balances: Validate data by ensuring mass and energy balances are consistent across the entire system [34].

Table 2: LCI Data Requirements for Chemical Process Assessment

| Data Category | Specific Inputs/Outputs | Data Sources & Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Material Inputs | Raw materials, catalysts, solvents, reagents | Laboratory batch records, pilot plant data, supplier information [35] |

| Energy Inputs | Electricity, steam, heating, cooling | Process energy monitoring, utility bills, engineering calculations [33] |

| Emissions to Air | CO₂, NOₓ, SOₓ, VOCs, process-specific emissions | Emission monitoring, stoichiometric calculations, emission factors [36] |

| Emissions to Water | Heavy metals, organic compounds, COD, BOD | Wastewater analysis, literature values for similar processes [33] |

| Waste & Co-products | Solid waste, hazardous waste, recyclable materials | Waste inventories, production records, allocation may be required [33] |

Stage 3: Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA)

The Life Cycle Impact Assessment translates inventory data into potential environmental impacts using scientifically established models [8] [32]. This phase provides the quantitative basis for understanding the significance of a process's environmental footprint.

Experimental Protocol: Impact Assessment Execution

- Selection: Choose appropriate impact categories and an LCIA methodology (e.g., ReCiPe, IMPACT 2002+) aligned with the goal and scope [34] [36].

- Classification: Assign each LCI flow (e.g., CO₂, SO₂, water use) to its relevant impact categories [8].

- Characterization: Calculate the contribution of each LCI flow to its assigned impact categories using characterization factors (e.g., CO₂-equivalents for global warming) [8] [34].

Advanced LCIA Steps (Optional)

- Normalization: Express impact category results relative to a reference value (e.g., per capita emissions) to understand their relative magnitude [8].

- Weighting: Assign relative weights to different impact categories based on their perceived importance. This step is value-layered and not always recommended for comparative studies [32].

Table 3: Core Impact Categories for Chemical Process LCIA

| Impact Category | Characterization Model | Unit | Relevance to Chemical Processes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Warming Potential (GWP) | Radiative forcing model | kg CO₂-equivalent | Energy-intensive processes, fossil-based feedstocks [8] [1] |

| Acidification Potential | Fate and exposure model | kg SO₂-equivalent | Emissions of SOₓ, NOₓ from energy generation [34] |

| Eutrophication Potential | Nutrient enrichment model | kg PO₄-equivalent | Nitrogen/phosphorus releases in wastewater [8] [1] |

| Human Toxicity | Risk-based model | kg 1,4-DCB-equivalent | Emissions of carcinogenic/non-carcinogenic substances [34] |

| Resource Depletion | Abundance-based model | kg Sb-equivalent | Use of scarce elements (e.g., catalysts, metals) [8] |

| Water Scarcity | Water scarcity index | m³ water equivalent | Solvent use, cooling water requirements [21] |

Stage 4: Interpretation

The interpretation stage involves evaluating the results from both the LCI and LCIA phases to form evidence-based conclusions and recommendations [8] [34]. This phase ensures that the study meets its original goal and provides actionable insights.

Experimental Protocol: Result Analysis and Validation

- Identify Significant Issues: Pinpoint life cycle stages, processes, or substances that contribute most substantially to the overall environmental impacts (hotspot analysis) [34].

- Conduct Sensitivity Analysis: Test how results change with variations in key parameters (e.g., different allocation methods, energy mixes, or data sources) to assess robustness [34] [36].

- Perform Consistency and Completeness Checks: Verify that the study adheres to the defined goal and scope and that all relevant data and processes have been included [32] [34].

- Draw Conclusions: Formulate conclusions that directly address the goal of the study, clearly stating limitations and uncertainties [32].

- Provide Recommendations: Suggest specific opportunities for improving the environmental performance of the chemical process, such as solvent substitution, energy efficiency measures, or catalyst recovery [1].

- Prepare Transparent Report: Document the entire LCA process, including all data, assumptions, and methodological choices, to ensure transparency and reproducibility [35].

Implementing a robust LCA for chemical processes requires both methodological rigor and specialized tools. The following table details key resources that constitute the researcher's toolkit.

Table 4: Essential Resources for Conducting Chemical Process LCA

| Tool/Resource | Function/Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| LCA Software (e.g., SimaPro, GaBi, OpenLCA) | Models complex life cycles, manages inventory data, performs impact calculations [32] | Core platform for building, calculating, and analyzing LCA models across all stages |

| LCI Databases (e.g., Ecoinvent, ELCD, US LCI) | Provides secondary data for background processes (e.g., electricity, chemicals, transport) [34] | Filling data gaps in supply chains; essential for cradle-to-gate assessments |

| Process Simulation Software (e.g., Aspen Plus, ChemCAD) | Generates mass and energy balance data from laboratory-scale information [36] | Scaling up laboratory data to industrial-scale inventory for the LCI phase |

| LCIA Methods (e.g., ReCiPe, IMPACT 2002+, EF method) | Provides the set of characterization factors to translate emissions into environmental impacts [36] | Standardized assessment of multiple environmental impacts in the LCIA phase |

| Allocation Procedures | Methodologies to partition environmental loads between multiple products in a system [33] | Solving multi-functionality problems in complex chemical production systems |

The rigorous application of the four LCA stages provides chemical and pharmaceutical researchers with a powerful, standardized framework for quantifying environmental impacts. From carefully defining the study's goal and scope to the critical interpretation of final results, each stage contributes essential components to a credible assessment. By adhering to these detailed protocols and utilizing the appropriate research toolkit, scientists can generate reliable data to guide the development of more sustainable chemical processes, reduce environmental footprints, and make informed decisions that align with global sustainability objectives.

Advanced LCA Methods and Green Chemistry Applications

Twelve Foundational Principles for Conducting LCA of Chemicals

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) has emerged as an indispensable methodology for evaluating the environmental impacts of chemical products and processes. Within the chemical industry, the application of LCA requires specialized approaches to address complex supply chains, multifunctional processes, and diverse environmental impact pathways. The twelve foundational principles for LCA of chemicals provide a structured framework to guide researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in conducting robust, comprehensive assessments that align with green chemistry objectives and support sustainable process design [37] [6].

These principles establish a procedural methodology that enables correct application of the life cycle perspective within green chemistry discipline, facilitating a 'benign by design' approach to chemical development [6]. For drug development professionals specifically, these principles offer critical guidance for assessing the environmental profile of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) and other chemical entities throughout their development lifecycle.

The Twelve Principles: Framework and Interpretation

The twelve principles are organized according to the logical sequence an LCA practitioner should follow, aligning with the established stages of LCA methodology while addressing chemical-specific considerations [6].

Principles 1-2: System Boundary Definition

Principle 1: Cradle to Gate - System boundaries must, at a minimum, encompass the cradle-to-gate perspective, from raw material extraction to production of the finished chemical. For intermediate chemicals with multiple downstream applications, this approach enables comprehensive analysis when primary differences reside in upstream stages. The cradle-to-synthesis approach may be appropriate for pharmaceuticals, including all steps until the purified API is obtained while excluding tableting and packaging. However, if chemicals differ in reference service life or disposal methods, the study must extend to cradle-to-grave boundaries. Gate-to-gate boundaries focusing only on Scope 1 flows should be discouraged as they fail to account for impacts from material extraction and final fate of molecules [6].

Principle 2: Consequential if Under Control - Practitioners should adopt a consequential LCA approach when possible, which aims to capture the effects of changes within the life cycle and extends analysis beyond plant facilities to include broader industrial ecosystems. This contrasts with attributional LCA, which quantifies environmental impacts of a system as it exists. The consequential approach is more action-oriented and valuable for decision-making, though more complex to implement in the chemical sector due to numerous variables affecting final results [6].

Principles 3-6: Life Cycle Inventory

Principle 3: Avoid to Neglect - Comprehensive inventories must capture all relevant inputs and outputs, avoiding systematic exclusion of any flow types. Current practices frequently overlook emissions (26%), waste, and wastewater (25%), while overemphasizing energy utilities (75%) and material inputs (70%) [31].

Principle 4: Data Collection from the Beginning - Data collection should be initiated at the earliest research stages to inform development and establish baselines. Early integration of LCA data supports R&D activities focused on optimizing chemical synthesis routes and process parameters [6].

Principle 5: Different Scales - Assessments must account for variations in process scale, from laboratory research to pilot plants and full industrial production. Scalability considerations significantly influence environmental impact projections and technology readiness evaluations.

Principle 6: Data Quality Analysis - Rigorous data quality assessment ensures reliability of inventory data through documentation of temporal, geographical, and technological representativeness. This is particularly crucial for chemical processes where catalyst systems, reagent purity, and reaction conditions substantially influence environmental footprints [6].

Principles 7-8: Life Cycle Impact Assessment

Principle 7: Multi-Impact - LCAs must evaluate multiple environmental impact categories beyond global warming potential, including acidification, eutrophication, ozone depletion, human toxicity, and ecotoxicity. Comprehensive multi-impact assessment prevents problem shifting between environmental compartments [6].

Principle 8: Hotspot - Analysis should identify environmental hotspots throughout the life cycle to prioritize intervention strategies. For chemical processes, hotspots often occur in feedstock production, energy-intensive separation operations, catalyst systems, or waste treatment stages [6].

Principles 9-10: Interpretation and Reporting

Principle 9: Sensitivity - Sensitivity analysis tests how results vary with changes in key parameters, data sources, or methodological choices. This is essential for evaluating robustness of conclusions, especially for emerging chemical technologies with uncertain process data.

Principle 10: Results Transparency, Reproducibility and Benchmarking - Complete transparency in methodology, data sources, and assumptions enables critical review and replication. Results should be benchmarked against conventional technologies or established baselines to contextualize environmental performance [6].

Principles 11-12: Methodological Integration

Principle 11: Combination with Other Tools - LCA should be integrated with complementary assessment tools including Social Life Cycle Assessment (S-LCA), life cycle costing, techno-economic analysis, and risk assessment to provide comprehensive sustainability evaluation [6] [38].

Principle 12: Beyond Environment - Assessment frameworks should expand beyond environmental dimensions to incorporate social and economic considerations, enabling full life cycle sustainability assessment. Preliminary social impact assessments can identify stakeholder preferences and social hotspots across the supply chain [6] [38].

LCA Workflow for Chemical Processes

The following workflow diagrams illustrate the procedural application of the twelve principles within chemical LCA studies, highlighting decision points and methodological considerations specific to chemical systems.

Procedural Workflow for Chemical LCA

System Boundary Selection Framework

Quantitative Data and Methodologies

LCA Modeling Approaches for Chemical Systems

Table 1: Comparison of LCA Modeling Approaches for Chemical Industry Applications

| Approach | Definition | Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Product-wise Optimization | Assesses system one alternative at a time with limited LCA model size [39] | Single chemical product evaluation; Limited alternative comparison | Limits model size; Simplified data requirements | Suboptimal technology decisions; Neglects supply chain connections; Multifunctionality challenges |

| Product Basket-wise Optimization | Simultaneously chooses supply chains for basket of products to minimize environmental burdens [39] | Industry-wide emission reduction; Petrochemical systems; Interlinked production networks | Captures supply chain connections; Avoids suboptimal decisions; Handles multifunctional processes | Requires complex model; Extensive data collection; Broader system boundaries |

| Attributional LCA | Quantifies potential environmental impacts of the system as it is [6] | Environmental footprint accounting; Static system description | Standardized methodology; Straightforward implementation | Limited decision-support capability; Doesn't capture market effects |

| Consequential LCA | Assesses potential environmental impacts resulting from changes within the system under study [6] | Policy decision support; Technology switching; Market expansion | Captures market-mediated effects; Action-oriented | Complex implementation; Multiple scenario variables |

Research demonstrates that product-wise optimization leads to 20-155% higher greenhouse gas emissions compared to product basket-wise optimization in petrochemical case studies due to (1) higher amount of by-products, (2) increased raw material need and processing, and (3) suboptimal technology decisions in the supply chain [39].

Key Environmental Impact Categories for Chemical LCA

Table 2: Essential Impact Categories for Comprehensive Chemical LCA

| Impact Category | Indicator | Chemical Sector Relevance | Common Data Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Climate Change | Global Warming Potential (GWP, kg CO₂ eq) | Energy-intensive processes; Feedstock production; Chemical reactions [38] | IPCC methodology; Industry-specific databases |

| Resource Depletion | Abiotic Depletion Potential (ADP, kg Sb eq) | Catalyst systems; Metal-based reagents; Mineral feedstocks [6] | Criticality assessments; Resource databases |

| Human Toxicity | Human Toxicity Potential (HTP, kg 1,4-DB eq) | API synthesis; Solvent use; Intermediate chemicals | USEtox model; Chemical-specific factors |

| Ecotoxicity | Freshwater/Marine/Terrestrial Ecotoxicity Potential | Pesticides; Surfactants; Industrial chemicals | USEtox model; Ecological risk assessments |

| Acidification | Acidification Potential (AP, kg SO₂ eq) | Sulfur-containing compounds; Combustion emissions | Regional impact models; Atmospheric chemistry |

Current analyses of chemical process design integration reveal significant methodological gaps: 74% of studies focus only on cradle-to-gate phases, 89% neglect use and end-of-life phases, and 92% do not define the function [31]. Environmental externalities are systematically excluded during model linkage, with most studies concentrating on energy utilities (75%) and material inputs (70%), while emissions (26%), waste, and wastewater (25%) are frequently overlooked [31].

Experimental Protocols and Application Notes

Protocol: Prospective LCA for Green Chemical Process Design

Purpose: To integrate LCA during research and development phases for emerging chemical technologies, enabling environmentally-informed process design decisions.

Materials and Equipment:

- Process simulation software (Aspen Plus, ChemCAD, or similar)

- LCA software (OpenLCA, SimaPro, GaBi, or similar)

- Life cycle inventory databases (ecoinvent, GREET, or sector-specific)

- Technical performance data (laboratory or pilot-scale)

Procedure:

- Define Goal and Scope: Establish functional unit reflecting primary function of chemical product. Apply Principle 1 to determine appropriate system boundaries (cradle-to-gate for intermediates with identical downstream processing).

Develop Inventory Model:

- Collect mass and energy balances from process simulations or experimental data

- Apply Principle 3 to ensure comprehensive inclusion of emissions, waste streams, and wastewater flows

- Document data quality indicators (Principle 6) including technological representativeness and precision

Construct Background System: Model upstream feedstock production and energy supply chains using consequential (Principle 2) or attributional approaches based on decision-context.

Calculate Impact Assessment: Apply multi-impact perspective (Principle 7) using impact assessment methods encompassing climate change, resource depletion, toxicity, and other relevant categories.

Interpret Results: Identify environmental hotspots (Principle 8) across life cycle stages. Conduct sensitivity analysis (Principle 9) on key parameters (yield, energy efficiency, catalyst lifetime).

Integrate with Complementary Assessments: Combine with techno-economic analysis and preliminary social assessment (Principles 11-12) to evaluate sustainability trade-offs.

Validation: Compare model projections with analogous commercial processes where available. Conduct peer review of methodology and assumptions to ensure transparency (Principle 10).

Protocol: Social-LCA for Chemical Production Systems

Purpose: To assess social impacts of chemical production pathways across supply chains, complementing environmental LCA with socio-economic indicators.

Materials:

- Social database (PSILCA, Soca, or similar)

- Stakeholder mapping tools

- Sector-specific social risk data

Procedure:

- Stakeholder Identification: Map affected stakeholders across chemical supply chain (workers, local communities, consumers, value chain actors).

Impact Category Selection: Define social indicators relevant to chemical sector (occupational health & safety, fair wages, community engagement, human rights).

Data Collection: Collect site-specific social performance data where available; use sector-average data for background systems.

Impact Assessment: Calculate social impact scores using characterized inventory data and social impact assessment methodology.

Interpretation: Identify social hotspots and improvement opportunities across supply chain.

Application Note: Preliminary social assessments can be conducted even with limited data to identify potential social risks and improvement opportunities, as demonstrated in methanol to propylene case studies [38].

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Chemical LCA Implementation

| Tool Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Application in Chemical LCA | Access Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| LCA Software | OpenLCA, SimaPro, GaBi | Modeling chemical production systems; Impact assessment calculation | Commercial and open-source options available |

| Process Modeling | Aspen Plus, ChemCAD, SuperPro Designer | Generating foreground inventory data from chemical process simulations | Academic licenses often available |

| Specialized Databases | ecoinvent, GREET, Sphera LCA databases | Providing background system data for chemical feedstocks and energy | Subscription-based; Some public datasets |

| Impact Assessment Methods | ReCiPe, EF Method, USEtox, ILCD | Calculating environmental impacts from chemical emissions and resource use | Integrated in LCA software |

| Chemical Sector Guidelines | Together for Sustainability (TfS) PCF guideline [40] | Standardized PCF calculations for chemical industry | Publicly available |

| Data Quality Tools | Pedigree matrix, Uncertainty calculator | Assessing reliability of chemical process inventory data | Integrated in some LCA software |

| Social-LCA Resources | PSILCA database, UNEP S-LCA guidelines | Assessing social impacts of chemical production systems | Subscription-based |

The twelve foundational principles for LCA of chemicals establish a comprehensive framework for evaluating environmental impacts of chemical products and processes. Implementation requires specialized approaches addressing multifunctionality, complex supply chains, and diverse impact pathways prevalent in chemical production systems. Integration of these principles during research and development phases enables green chemistry innovation aligned with life cycle sustainability objectives. Future methodological development should focus on improving circularity assessment, advancing prospective LCA for emerging technologies, and strengthening social sustainability integration.

{#introduction}

In Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) for chemical processes, defining system boundaries is a foundational step that determines the scope, accuracy, and applicability of the environmental impact analysis. The choice between "cradle-to-grave" and "cradle-to-gate" approaches dictates which stages of a product's life are included in the assessment, directly influencing the insights gained and the strategic decisions they inform. A cradle-to-grave analysis encompasses the complete life cycle of a product, from raw material extraction ("cradle") to its final disposal ("grave") [41] [42]. In contrast, a cradle-to-gate assessment covers a partial life cycle, from raw material extraction only until the product leaves the factory gate, typically before distribution to the customer [2] [42]. For researchers and scientists in chemical and pharmaceutical development, selecting the appropriate model is critical for complying with regulations, guiding sustainable process design, and generating reliable data for both internal use and communication across the value chain.

{#contrast}

Contrasting the Two Approaches

The table below provides a structured comparison of the cradle-to-gate and cradle-to-grave methodologies.

| Feature | Cradle-to-Gate LCA | Cradle-to-Grave LCA |

|---|---|---|

| Scope Definition | Assesses a product's life cycle from resource extraction (cradle) to the factory gate [42]. | Assesses a product's full life cycle from resource extraction (cradle) to disposal (grave) [41] [42]. |

| Life Cycle Stages Covered | Raw material extraction, manufacturing & processing [41] [2]. | Raw material extraction, manufacturing & processing, transportation, usage & retail, waste disposal [41] [2]. |

| Typical Applications | - Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs) [2].- Sharing environmental data with downstream customers (B2B) [42].- Internal assessment of production stages [42]. | - Comprehensive environmental footprinting [41].- Informing eco-design and product development [42].- Identifying burden-shifting between life cycle stages [41]. |