Ionic Liquids in Energy Storage: Advanced Applications in Electrodeposition and Next-Generation Batteries

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of ionic liquids (ILs) as key materials for advancing electrochemical technologies, focusing on their foundational properties, methodological applications in metal electrodeposition and battery electrolytes,...

Ionic Liquids in Energy Storage: Advanced Applications in Electrodeposition and Next-Generation Batteries

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of ionic liquids (ILs) as key materials for advancing electrochemical technologies, focusing on their foundational properties, methodological applications in metal electrodeposition and battery electrolytes, and strategies for optimizing their performance. It explores the unique physicochemical properties of ILs—including their wide electrochemical windows, high thermal stability, and non-flammability—that make them superior to conventional electrolytes. The content details specific applications in sustainable metal recovery and the development of safer lithium-ion, aluminum, and magnesium batteries, addressing current challenges like viscosity and cost. Through validation techniques such as machine learning for property prediction and comparative analyses with organic electrolytes, this review synthesizes cutting-edge research to guide scientists and engineers in harnessing ILs for more efficient, safe, and sustainable energy storage and conversion systems.

Understanding Ionic Liquids: Fundamental Properties and Electrochemical Advantages

Ionic liquids (ILs) are a class of chemical compounds defined as salts that exist in the liquid state at relatively low temperatures, typically below 100 °C [1] [2]. Often described as "liquid salts" or "designer solvents," their fundamental distinction from conventional salts like sodium chloride lies in their composition of bulky, asymmetrically shaped organic cations and organic or inorganic anions, which inhibits crystal lattice formation and results in low melting points [3] [4]. This molecular structure underpins their status as a versatile platform for tailor-made materials in electrochemistry and beyond.

The historical development of ionic liquids dates back to 1914 with Paul Walden's report on ethylammonium nitrate, which has a melting point of 12 °C [1] [2] [4]. However, significant interest emerged in the latter half of the 20th century, driven by research from the U.S. Air Force Academy seeking replacement electrolytes for thermal batteries [3] [4]. A pivotal advancement occurred in 1992 with the development of ionic liquids featuring 'neutral' and water-stable anions such as hexafluorophosphate (PF₆⁻) and tetrafluoroborate (BF₄⁻), which dramatically expanded their application potential [1].

Fundamental Characteristics and Properties

Ionic liquids possess a suite of extraordinary properties that make them particularly attractive for scientific and industrial applications. Their most prominent characteristics include low or negligible vapor pressure, high thermal stability, non-flammability, wide electrochemical windows, and good ionic conductivity [5] [6] [4]. A key advantage is their tunability; by selecting different cation-anion combinations, properties such as hydrophobicity, viscosity, density, and melting point can be precisely tailored for specific applications [5] [4]. This has earned them the "designer solvents" moniker.

Table 1: Key Properties of Ionic Liquids vs. Traditional Materials

| Property | Ionic Liquids | Conventional Solvents (e.g., Water, Acetonitrile) | Traditional Salts (e.g., NaCl) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vapor Pressure | Negligible [5] [6] | High, volatile | Very low (solid) |

| Thermal Stability | High (often >300°C) [2] [4] | Low (boils at 100°C) | Very high (melts at 801°C) [3] |

| Flammability | Generally non-flammable [5] | Often flammable | Non-flammable |

| Electrochemical Window | Wide (up to 6 V) [6] | Narrow (~1.23 V for water) | Not applicable (solid) |

| Designability | Highly tunable [4] | Fixed properties | Fixed properties |

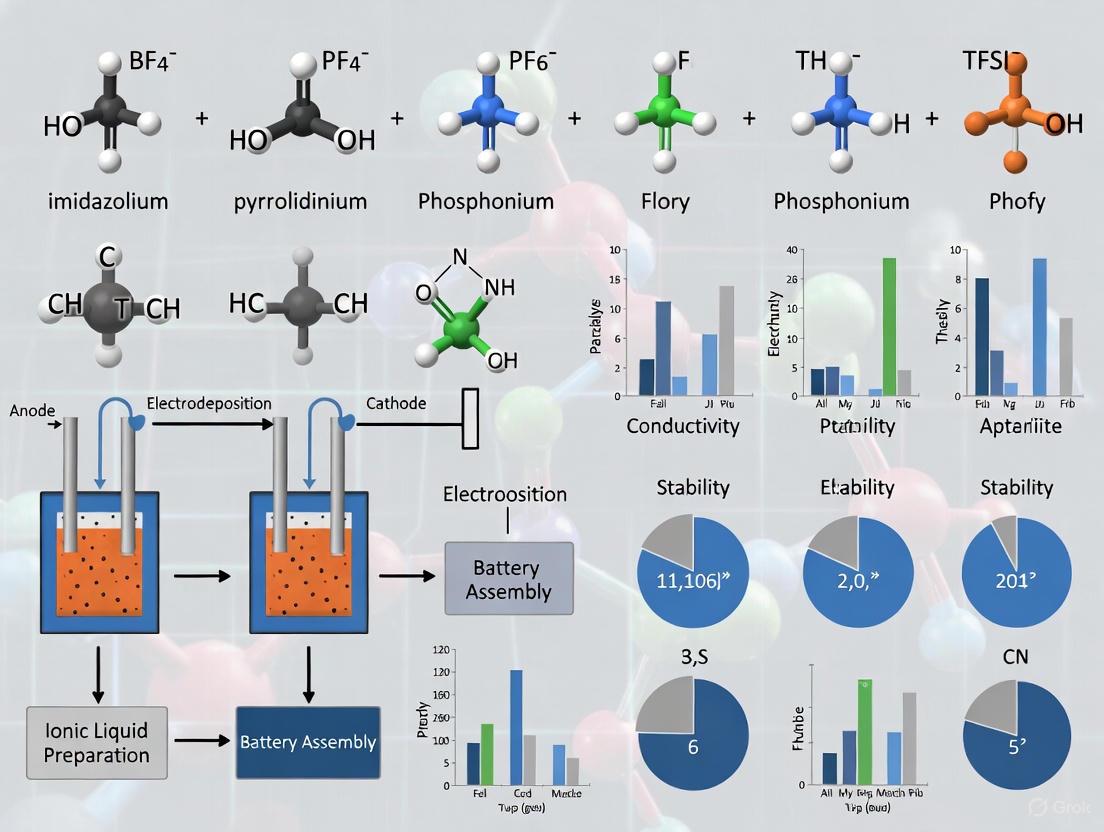

The Ionic Liquid Toolkit: Cations, Anions, and Their Combinations

The properties of an ionic liquid are dictated by the structures of its constituent cation and anion. The vast number of possible combinations creates an immense design space, estimated at over 10¹⁸ theoretically possible ionic liquids [2].

Common Cations and Anions

The most prevalent cations in room-temperature ionic liquids (RTILs) are nitrogen-containing heterocycles, such as imidazolium and pyridinium, along with quaternary ammonium and phosphonium ions [1] [6] [4]. Common anions range from simple halides to complex fluorinated or organic ions [1] [5].

Table 2: Common Ions in Ionic Liquid Synthesis and Their Characteristics

| Ion Type | Example Ions | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Cations | 1-Alkyl-3-methylimidazolium (e.g., [BMIM]⁺, [EMIM]⁺) [1] [6] | High electrochemical stability, good conductivity, widely studied |

| Pyrrolidinium (e.g., [C₄MPyrr]⁺) [6] [7] | Excellent ionic conductivity, good low-temperature performance | |

| Phosphonium (e.g., [P₆,₆,₆,₁₄]⁺) [1] [7] | High thermal stability (up to 150°C), excellent chemical stability | |

| Quaternary Ammonium (e.g., [N₁₁₁₄]⁺) [7] | Lower viscosity, cost-effective synthesis | |

| Anions | Bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide ([TFSI]⁻ or [NTf₂]⁻) [5] [6] | Hydrophobic, high electrochemical and thermal stability |

| Tetrafluoroborate ([BF₄]⁻) [1] [6] | Moderate hydrophilicity, good electrochemical stability | |

| Hexafluorophosphate ([PF₆]⁻) [1] [6] | Hydrophobic, widely used in electrochemistry | |

| Halides (e.g., Cl⁻, Br⁻) [1] [5] | Hydrophilic, often used as precursors |

Ion Combination Diagram

Research Reagent Solutions

The selection of ionic liquids for research is critical. The following table details key materials and their functions in electrochemical research.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Electrodeposition and Battery Applications

| Reagent / Material | Chemical Formula / Example | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Imidazolium-based IL | 1-Ethyl-3-methylimidazolium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide ([EMIM][TFSI]) [5] [6] | High-stability electrolyte for batteries and supercapacitors; solvent for electrodeposition. |

| Pyrrolidinium-based IL | N-Butyl-N-methylpyrrolidinium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide ([C₄MPyrr][TFSI]) [5] [7] | Electrolyte for high-voltage lithium-ion batteries; offers excellent low-temperature performance. |

| Magnesium Source | Magnesium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide (Mg(TFSI)₂) [8] | Provides Mg²⁺ ions for the electrodeposition of metallic magnesium or for magnesium battery electrolytes. |

| Lithium Salt | Lithium bis(trifluoromethane sulfonyl)imide (LiTFSI) [6] | The active charge carrier in lithium-ion battery electrolytes based on ionic liquids. |

| Co-solvent | Acetonitrile, Propylene Carbonate [8] [6] | Reduces viscosity of IL-based electrolytes, enhancing mass transport and ion mobility. |

Application Notes in Electrodeposition and Batteries

Electrodeposition of Reactive Metals

Ionic liquids have emerged as revolutionary electrolytes for the electrodeposition of reactive metals like magnesium, aluminum, and lithium, which is difficult or impossible in aqueous media due to water's narrow electrochemical window [8]. A systematic review highlights their role in enabling magnesium electrodeposition from sources like bischofite (MgCl₂·6H₂O), offering a more sustainable pathway compared to energy-intensive industrial methods [8]. The wide electrochemical stability window of ILs prevents water decomposition, allowing for the deposition of these metals. Key operational parameters for successful electrodeposition include temperature control (to manage viscosity), precursor purity, and cell design [8]. Strategies such as using elevated temperatures and co-solvents are effective in mitigating the high viscosity of some ILs, thereby improving ion transport and deposit quality [8].

Mg Electrodeposition Workflow

Battery Electrolytes and Supercapacitors

In energy storage, ionic liquids are primarily employed as advanced electrolytes in lithium-ion batteries, next-generation batteries (e.g., Mg, Na), and supercapacitors [6] [7]. Their non-flammability and negligible vapor pressure directly address critical safety concerns associated with conventional organic electrolytes, which are volatile and prone to causing thermal runaway [6]. Furthermore, their high thermal stability and wide electrochemical windows enable batteries to operate at higher voltages and across a broader temperature range [6] [7].

The global market for ionic liquids in battery applications, valued at USD 111 million in 2024 and projected to grow at a CAGR of 10.2%, reflects this strong technological promise [7]. Imidazolium-based ILs currently dominate the market share (45.2% in 2024), while pyrrolidinium-based ILs are notable for their high ionic conductivity and excellent low-temperature performance [7]. Major application segments include electric vehicle batteries (30.2% share), grid energy storage (26.1% share), and consumer electronics [7].

Table 4: Ionic Liquid Electrolytes in Energy Storage Devices

| Device Type | Role of Ionic Liquid | Key Benefits | Example ILs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lithium-Ion Battery | Solvent for Li salts, replacing volatile carbonates [6]. | Enhanced safety (non-flammable), higher temperature operation, wider voltage window. | [C₄MPyrr][TFSI] with LiTFSI [6] [7] |

| Magnesium Battery | Electrolyte medium for Mg²⁺ ion transport [8]. | Enables reversible Mg plating/stripping; potential use of hydrated salts. | Mg(TFSI)₂ in [EMIM][TFSI] [8] |

| Electrochemical Capacitor (Supercapacitor) | Pure electrolyte or ion source [6]. | High stability for long cycle life, wide operational temperature range. | [BMIM][BF₄], [EMIM][TFSI] [5] [6] |

| Solid-State Battery | Component in hybrid/composite solid electrolytes [7]. | Improves interfacial contact and ionic conductivity. | Various [TFSI]⁻-based ILs [7] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Electrodeposition of Magnesium from an Ionic Liquid Electrolyte

This protocol outlines the procedure for the electrodeposition of metallic magnesium, adapted from a recent systematic review [8].

5.1.1 Scope and Application This method describes the setup and execution of magnesium electrodeposition for research purposes, such as creating corrosion-resistant coatings or composite electrode materials. It is suitable for use with various imidazolium or pyrrolidinium-based ionic liquids.

5.1.2 Safety Considerations

- Perform all procedures in an inert atmosphere (e.g., Ar or N₂ glove box) due to the moisture sensitivity of many ionic liquids and magnesium salts.

- Wear appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE), including gloves and safety glasses.

5.1.3 Reagents and Materials

- Ionic Liquid: e.g., 1-Butyl-1-methylpyrrolidinium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide ([C₄MPyrr][TFSI]). Dry under vacuum at elevated temperature (e.g., 80-100 °C) for >24 hours before use [8].

- Magnesium Salt: e.g., Magnesium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide (Mg(TFSI)₂). Dry thoroughly.

- Co-solvent (Optional): Anhydrous acetonitrile or propylene carbonate, to reduce viscosity.

- Substrates/Electrodes: Working electrode (e.g., Pt, stainless steel, Cu foil); Counter electrode (e.g., Mg ribbon, Pt mesh); Reference electrode (e.g., Ag/Ag⁺).

- Electrochemical Cell: A standard three-electrode cell.

5.1.4 Procedure

- Electrolyte Preparation: Inside the glove box, dissolve the dried Mg(TFSI)₂ salt into the pure ionic liquid at a desired concentration (e.g., 0.1 - 0.5 M). If using a co-solvent, add it at this stage and mix thoroughly.

- Cell Assembly: Place the working, counter, and reference electrodes into the electrochemical cell. Introduce the prepared electrolyte into the cell.

- System Optimization (Key Step):

- Temperature Control: Place the cell in an oven or on a hotplate to maintain a constant elevated temperature (e.g., 50-80 °C). This is critical for lowering viscosity and improving Mg²⁺ ion mobility [8].

- Viscosity Management: Monitor solution viscosity. If too high, consider the addition of a co-solvent (5-20% v/v) [8].

- Electrodeposition:

- First, perform cyclic voltammetry (CV) to identify the reduction potential for Mg²⁺/Mg.

- Then, perform potentiostatic or galvanostatic electrodeposition at the determined conditions for a set duration.

- Post-Processing: After deposition, carefully remove the working electrode from the cell, rinse it with a dry solvent (e.g., anhydrous acetonitrile) to remove residual ionic liquid, and dry under vacuum.

- Analysis: Characterize the magnesium deposit using techniques such as scanning electron microscopy (SEM), energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS), or X-ray diffraction (XRD).

Protocol: Formulating a Safe Lithium-Ion Battery Electrolyte

This protocol provides a methodology for preparing a non-flammable electrolyte for lithium-ion batteries using an ionic liquid as the primary solvent.

5.2.1 Safety Considerations

- Conduct all procedures in an inert atmosphere glove box due to the moisture sensitivity of lithium salts and some ionic liquids.

- Standard battery assembly safety protocols must be followed.

5.2.2 Reagents and Materials

- Ionic Liquid: e.g., N-Butyl-N-methylpyrrolidinium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide ([C₄MPyrr][TFSI]). Dry thoroughly before use [6] [7].

- Lithium Salt: Lithium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide (LiTFSI).

- Equipment: Vials, magnetic stirrer, moisture-compatible pipettes.

5.2.3 Procedure

- Drying: Place the ionic liquid in a vial and dry under high vacuum at 80-100 °C for at least 24 hours to reduce water content to ppm levels [6].

- Salt Addition: Add the predetermined amount of dry LiTFSI salt to the vial containing the ionic liquid. A typical concentration range is 0.5 M to 1.0 M.

- Mixing: Cap the vial and stir the mixture on a magnetic stirrer with heating (e.g., 50-60 °C) until a clear, homogeneous solution is obtained. This may take several hours due to the high viscosity of the IL.

- Quality Control: The final electrolyte should be a clear, colorless to pale yellow liquid. Its performance should be validated by measuring ionic conductivity and electrochemical stability window before cell assembly.

- Cell Filling: This electrolyte can be used to fill laboratory-scale lithium-ion coin cells or pouch cells for performance and safety testing.

Ionic liquids have firmly established themselves as a cornerstone of modern materials science, evolving from scientific curiosities into indispensable "designer solvents" for electrochemistry. Their unique properties—including unparalleled tunability, intrinsic safety, and wide electrochemical windows—make them particularly transformative for the electrodeposition of reactive metals and the development of next-generation, safer energy storage devices. As fundamental research continues to unravel the intricacies of their behavior and as synthesis costs decrease, the integration of ionic liquids into commercial applications, especially in electric vehicle batteries and grid storage, is poised to accelerate. Their role in enabling sustainable and efficient electrochemical technologies underscores their enduring impact and vast future potential.

Ionic liquids (ILs), defined as salts with melting points below 100 °C, have emerged as a revolutionary class of materials for advanced electrochemical applications. Their unique ionic composition, consisting of organic cations and organic or inorganic anions, confers a suite of tunable physicochemical properties that make them superior to conventional aqueous and organic electrolytes. Within the context of electrodeposition and battery research, three properties are paramount: high ionic conductivity for efficient charge transport, exceptional thermal stability for operational safety at elevated temperatures, and inherent non-flammability to mitigate fire hazards. This application note details the quantitative data, experimental protocols, and practical reagent information essential for researchers leveraging ILs in these cutting-edge fields.

Quantitative Property Analysis of Ionic Liquids

The utility of ILs in electrodeposition and batteries is rooted in their measurable and tunable properties. The data below provides a benchmark for material selection.

Table 1: Key Physicochemical Properties of Common Ionic Liquids

| Ionic Liquid (Example) | Ionic Conductivity (mS/cm) | Electrochemical Window (V) | Thermal Decomposition Onset (°C) | Flammability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [Pyr14][NTf2] (1-Butyl-1-methylpyrrolidinium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide) | ~1.4 [9] | ~3.5 [9] | >400 [10] | Non-flammable [11] [12] |

| [bmim][NTf2] (1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide) | ~4.0 [9] | ~3.0 [9] | ~400 [10] [13] | Non-flammable [11] [12] |

| [bmim][BF4] (1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate) | ~3.5 [9] | Data not available | ~400 [10] | Non-flammable [11] [12] |

| Conventional Organic Electrolyte (e.g., 1 M LiPF6 in EC/DMC) | ~10 [10] | ≤3.5 [11] [12] | Flash point ~18-30 °C [10] | Flammable [10] [11] [12] |

The properties of ILs span a wide range, influenced by the cation-anion combination. Typically, ILs offer an exceptional balance, with ionic conductivities ranging from 0.1 to 20 mS cm-1 [11] [9] and electrochemical windows of 2 to 6 V [14] [11] [9], significantly wider than aqueous electrolytes (1.2 V). Their thermal decomposition onset temperatures (Tonset) are typically in the range of 200–500°C [10] [13], far exceeding the boiling or flash points of conventional organic electrolytes. A key safety advantage is their non-flammability, a direct result of their negligible vapor pressure [10] [11] [12].

Table 2: Impact of Anion on Thermal Stability of Imidazolium-Based ILs [13]

| Anion | Approximate Decomposition Temperature Tonset (°C) |

|---|---|

| Dicyanamide ([DCA]-) | ~200 |

| Tetrafluoroborate ([BF4]-) | ~350 |

| Hexafluorophosphate ([PF6]-) | ~450 |

| Bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide ([NTf2]-) | ~450 |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Electrodeposition of Reactive Metals from Ionic Liquids

The wide electrochemical window of ILs enables the electrodeposition of reactive metals like lithium, aluminum, and rare-earth elements, which is impossible in aqueous solutions due to hydrogen evolution [14].

Workflow: Electrodeposition of Reactive Metals

Detailed Procedure:

Electrolyte Preparation: Inside an argon-filled glovebox (H2O, O2 < 1 ppm), transfer the chosen ionic liquid (e.g., [C4mim]Cl for Al deposition) into a reaction vessel. Dry the IL under vigorous stirring at ~80-100°C under high vacuum for at least 24 hours. Gradually add the anhydrous metal salt (e.g., AlCl3 for aluminum deposition [14]) in a controlled molar ratio to form the final electroplating bath.

Cell Assembly: A standard three-electrode electrochemical cell is used.

- Working Electrode (WE): The substrate for deposition (e.g., copper or steel foil). Clean and polish the substrate before use.

- Counter Electrode (CE): A high-purity metal wire or rod (e.g., platinum or a strip of the metal to be deposited).

- Reference Electrode (RE): An Ag/AgCl or a quasi-reference electrode (e.g., a silver wire). Assemble the cell inside the glovebox to prevent contamination.

Voltammetric Analysis: Before deposition, perform Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) to determine the exact reduction potential of the target metal ion. Typical parameters: scan rate of 10-50 mV/s, potential range tailored to the IL's electrochemical window. The CV will show a clear cathodic peak corresponding to metal ion reduction.

Electrodeposition: Based on the CV results, perform constant potential (potentiostatic) or constant current (galvanostatic) electrodeposition. For a uniform coating, moderate current densities or potentials should be applied. The process can be monitored by tracking the charge passed.

Post-Processing and Characterization: After deposition, remove the working electrode, and rinse it thoroughly with a dry solvent (e.g., acetonitrile) to remove residual IL. Characterize the resulting metal coating using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) for morphology, Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDX) for composition, and X-ray Diffraction (XRD) for crystallinity.

Protocol 2: Evaluating Ionic Liquids in Lithium-Metal Battery Cells

ILs are promising electrolytes for safer lithium-metal batteries (LMBs) due to their ability to form stable solid-electrolyte interphases (SEIs) and suppress lithium dendrite growth [15] [10].

Workflow: Battery Cell Testing

Detailed Procedure:

Electrolyte Formulation: In an argon-filled glovebox, prepare the IL-based electrolyte. A common formulation is a 1:1.2:3 molar ratio of LiFSI:DME:TTE, known as a localized high-concentration electrolyte (LHCE) [15]. Pre-dry all components. The high concentration of LiFSI is crucial for forming a stable, anion-derived inorganic SEI.

Electrode and Cell Preparation:

- Cathode: Use a high-energy-density material like LiNi0.8Mn0.1Co0.1O2 (NMC811) coated on an aluminum foil. The typical active material loading should be ≥ 17.1 mg cm-2 for practical relevance [15].

- Anode: Use a thin lithium metal foil (e.g., 20 μm thickness).

- Cell Assembly: Assemble CR2032 coin cells or single-layer pouch cells inside the glovebox. Include a separator (e.g., glass fiber) saturated with the IL electrolyte.

Electrochemical Testing:

- Ionic Conductivity: Use Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) on a symmetric cell (e.g., stainless steel | electrolyte | stainless steel) over a frequency range (e.g., 1 MHz to 100 mHz) to measure bulk resistance and calculate conductivity.

- Cycling Performance: Cycle the cells between set voltage limits (e.g., 3.0 - 4.3 V for NMC811|Li cells) at various C-rates. Critical metrics to monitor are the Coulombic Efficiency (CE), which should be >99.5% for viable LMBs, and the capacity retention over hundreds of cycles [15].

Post-Mortem Analysis: After cycling, disassemble cells in the glovebox. Analyze the lithium metal anode and NMC cathode surfaces using techniques like SEM to observe dendrite formation or cathode cracking, and X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) to determine the chemical composition of the SEI and cathode-electrolyte interphase (CEI).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Ionic Liquids and Components for Electrodeposition and Battery Research

| Reagent/Solution | Function/Application | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Aprotic Ionic Liquids | Solvent-free electrolyte for electrodeposition and batteries. Wide electrochemical window and thermal stability. | [Pyr14][NTf2]: High anodic stability, good for high-voltage batteries [9]. [C4mim][BF4]: Common for general electrochemistry [9]. |

| Lithium Salts | Provides Li+ ions for conduction in lithium batteries. | LiFSI (Lithium bis(fluorosulfonyl)imide): Preferred for forming stable SEI; continuous decomposition can cause ion depletion [15]. LiTFSI: Also widely used, offers good stability [10]. |

| Aluminum Chloride (AlCl3) | Key component for creating chloroaluminate ILs used in aluminum electrodeposition. | Must be handled in strict anhydrous conditions. Mixed with [C4mim]Cl to form the active plating bath [14]. |

| Ether Solvents (as Diluents) | Co-solvents in LHCE formulations to reduce viscosity and improve kinetics. | DME (Dimethoxyethane): Used in LHCEs with LiFSI [15]. TTE (1,1,2,2-Tetrafluoroethyl-2,2,3,3-tetrafluoropropyl ether): Non-solvating diluent in LHCEs to maintain local high concentration [15]. |

| Metal Salts | Source of metal ions for electrodeposition. | Anhydrous NiCl2, CuCl2, LaCl3, UCl4: Must be of high purity and thoroughly dried [16] [14]. |

Ionic liquids provide an unparalleled combination of ionic conductivity, thermal resilience, and non-flammability, making them indispensable for advancing the safety and performance of electrodeposition processes and next-generation batteries. Their tunable nature allows for precise customization to meet specific application demands, from depositing high-purity reactive metals for nuclear medicine targets to enabling long-cycling lithium-metal batteries for electric vehicles. By adhering to the detailed protocols and utilizing the recommended reagents outlined in this document, researchers can effectively harness these properties to drive innovation in their electrochemical research and development.

The electrochemical stability window (ESW) is a fundamental parameter defining the voltage range within which an electrolyte remains stable without decomposing. For lithium-ion batteries and supercapacitors, a wide ESW is critical because it directly enables the use of high-voltage electrode materials, thereby significantly increasing the device's energy density, which scales with the square of the operating voltage [17]. Traditional organic liquid electrolytes, while having high ionic conductivity, possess limited ESWs and pose serious safety risks due to their flammability [11] [18].

Ionic liquids (ILs)—molten salts with melting points below 100°C—have emerged as a superior class of electrolytes for high-voltage applications. Their unique cation-anion combinations confer exceptional properties, including wide electrochemical windows (up to 5–6 V), non-flammability, low volatility, and excellent thermal stability [11] [17]. This application note details the role of ILs in extending the ESW and provides standardized protocols for its accurate measurement, framed within ongoing research aimed at developing safer, high-energy-density batteries.

Theoretical Background: The Electrochemical Stability Window

The practical ESW of an electrolyte is the voltage range between its reduction potential (at the anode) and its oxidation potential (at the cathode). Operating a battery beyond this window leads to electrolyte decomposition, causing gas generation, impedance growth, and rapid capacity fade [19].

For solid electrolytes, two distinct stability windows are recognized:

- The Decomposition Window: Determined by the thermodynamic formation energy of the most stable decomposition products. This often provides a conservative, narrow estimate of stability.

- The Intrinsic (Kinetic) Window: Dictated by the (de)lithiation potential of the solid electrolyte itself. This indirect decomposition pathway can have a significant kinetic barrier, resulting in a much wider practical stability window than predicted by thermodynamics alone [20].

Ionic liquids overcome the limitations of aqueous and organic electrolytes. Their wide ESW stems from the high electrochemical stability of their constituent ions, which can be further tuned by selecting specific cation-anion pairs. For instance, pyrrolidinium-based cations generally offer wider windows than imidazolium-based ones, while anions like TFSI− and FSI− are known for their robust stability [11] [17].

Quantitative Data: ESW of Electrolyte Systems

The following tables summarize the ESW for various electrolyte types and specific ionic liquid formulations, providing a comparative overview for researchers.

Table 1: Comparison of General Electrolyte Types for EES Devices

| Electrolyte Type | Typical ESW (V vs. Li+/Li) | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aqueous | ~1.2 | High ionic conductivity, low cost, safe | Very narrow ESW limits energy density [11] |

| Organic Liquid | Up to ~3.5 | High ionic conductivity, good electrode wetting | Flammable, toxic, limited ESW [11] [18] |

| Ionic Liquids (Aprotic) | 4.5 – 6.0 | Wide ESW, non-flammable, high thermal stability | High viscosity, higher cost, complex synthesis [11] [17] |

| Solid Polymer (e.g., PEO) | ~4.0 - 5.0 | Enhanced safety, flexibility, suppresses dendrites | Low ionic conductivity at room temperature [19] |

Table 2: Exemplary ESW Values for Solid and Composite Polymer Electrolytes

| Solid Electrolyte/Sample | Composition | Ionic Conductivity (S/cm) | ESW / Eox (V vs. Li+/Li) | Measurement Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEO-based SCE | PEO–LiPCSI | 7.33 × 10−5 @ 60°C | 5.53 | LSV, 0.2 mV/s, 60°C [19] |

| Polymer Ionic Liquid | PIL-SN-PCE | 6.54 × 10−4 @ RT | 5.4 | LSV, 1 mV/s [19] |

| Composite Electrolyte | DAVA + ETTMP 1300 / LiPF6 | 7.65 × 10−4 @ RT | 6.0 | LSV, 100 mV/s [19] |

| Block Copolymer | BCT / LiTFSI | 9.1 × 10−6 @ 30°C | 5.0 | CV, 1 mV/s, 60°C [19] |

Experimental Protocols for ESW Determination

Accurately determining the ESW is crucial, as improper methods can lead to significant overestimation. Traditional cyclic voltammetry (CV) or linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) on inert electrodes can be misleading due to limited electrode-electrolyte contact area and the short timescale of the experiment, which may not capture slow decomposition reactions [20] [19].

Protocol: Comprehensive ESW Evaluation via Coupled LSV and GCD

This protocol, adapted from recent critical reviews, provides a more reliable assessment of an electrolyte's practical stability window [19] [21].

1. Principle: The method correlates the onset of faradaic reactions in LSV with a descriptor for side reactions derived from galvanostatic charge/discharge (GCD), providing a more realistic ESW by mitigating subjective factors.

2. Materials and Equipment:

- Electrochemical Workstation: Capable of performing LSV, CV, and EIS.

- Test Cell: A symmetric cell (e.g., SS|Electrolyte|SS) or a three-electrode cell with a controlled atmosphere (e.g., Ar-filled glovebox).

- Working Electrode: Inert electrodes (e.g., stainless steel, platinum, or glassy carbon). The surface area and roughness must be documented.

- Counter Electrode: Lithium metal or a similar inert material.

- Reference Electrode: Li+/Li (essential for reporting potentials vs. Li+/Li).

- Ionic Liquid Electrolyte: Must be thoroughly purified and dried to remove water and impurities.

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Cell Assembly

- Assemble the test cell in an inert atmosphere glovebox (H₂O and O₂ < 1 ppm).

- Ensure good contact between the electrolyte and electrodes. For solid electrolytes, apply isostatic pressure and document it.

Step 2: Linear Sweep Voltammetry (LSV)

- Use a slow scan rate (e.g., 0.1 - 0.5 mV/s) to approach quasi-steady-state conditions and detect slow decomposition processes.

- Perform separate scans for the anodic limit (e.g., from OCP to 6.5 V) and the cathodic limit (e.g., from OCP to -0.5 V).

- Record the current response. The decomposition potential (Edecomp) is typically identified as the voltage at which the current density exceeds a pre-defined threshold (e.g., 0.1 mA/cm²).

Step 3: Galvanostatic Charge-Discharge (GCD)

- Construct a full cell (e.g., carbon-based EDLC) using the IL electrolyte.

- Cycle the cell at a constant current over a range of progressively increasing voltage windows.

- For each voltage window, record the charge and discharge curves.

Step 4: Data Analysis and ESW Determination

- Plot the coulombic efficiency (CE) of the GCD cycles against the maximum cell voltage.

- The voltage at which the CE begins to drop significantly indicates the onset of practical electrolyte decomposition.

- Correlate this voltage with the LSV results. The practical ESW is the range where both methods confirm stability.

Diagram: Experimental Workflow for ESW Determination. This protocol correlates LSV and GCD data for a more accurate and practical ESW value.

Critical Considerations for Accurate ESW Measurement

- Electrode Material: The choice of inert electrode is critical, as its surface chemistry can catalyze decomposition.

- Scan Rate: Slower scan rates are essential for meaningful data, as high rates can artificially widen the apparent ESW.

- Stability vs. Metastability: A wide ESW measured by LSV may indicate kinetic metastability. Long-term cycling tests within the proposed window are necessary to confirm operational stability [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for Ionic Liquid Electrolyte Research

| Research Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Characteristics & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Pyrrolidinium-based ILs (e.g., PYR14TFSI) | High-voltage electrolyte base | Wide ESW, good transport properties; a benchmark cation for battery ILs [11] [17]. |

| Imidazolium-based ILs (e.g., EMIM-TFSI) | Electrolyte for supercapacitors | High ionic conductivity; but may have a narrower ESW and lower cathodic stability [11] [17]. |

| Lithium Salts (LiTFSI, LiFSI) | Lithium ion source | High solubility in ILs, good dissociation; contributes to Li+ conduction [18]. |

| Polymer Hosts (PEO, PVDF-HFP) | Matrix for ion-gels/quasi-solid electrolytes | Provides mechanical integrity, reduces electrolyte fluidity, enhances safety [18]. |

| Inorganic Fillers (Li6.4La3Zr1.4Ta0.6O12 - LLZTO) | Filler in Solid Composite Electrolytes (SCEs) | Enhances ionic conductivity, mechanical strength, and interfacial stability [18] [19]. |

Ionic liquids, with their inherently wide electrochemical stability windows, are pivotal enablers for the next generation of high-voltage, high-energy-density batteries. Moving beyond traditional organic electrolytes to IL-based systems—including binary IL-Li salt mixtures, ionogels, and composite electrolytes—addresses the critical challenges of safety and performance. The accurate and reliable determination of the ESO through standardized, rigorous protocols is not merely an academic exercise but a fundamental prerequisite for the rational design and commercial realization of advanced electrochemical energy storage devices. Future research will continue to focus on tailoring IL chemistries to optimize ionic conductivity, reduce cost, and improve compatibility with both lithium metal anodes and high-voltage cathodes like NMC and NCA.

Ionic liquids (ILs) have emerged as a transformative class of electrolytes in electrochemical research, distinguished by their modular nature. This property allows researchers to strategically combine organic or inorganic cations with various anions to precisely tailor physicochemical properties for specific applications, from energy storage to metal electrodeposition. The evolution of ILs has progressed through generations, from initial use as green solvents to advanced applications in catalysis and electrochemical systems, with current research focusing on sustainable, task-specific functionalities [22]. This application note details how specific cation-anion combinations address fundamental challenges in electrodeposition and battery science, providing structured experimental data, validated protocols, and visual guides to empower research and development efforts.

Application Notes: Strategic Cation-Anion Synergy in Action

The intentional pairing of cations and anions in ionic liquids or electrolyte additives enables the targeted optimization of electrochemical interfaces and processes. The following case studies illustrate this principle with quantitative outcomes.

Case Study 1: Suppressing Shuttle Effects in Zn-Iodine Batteries

Background: Aqueous Zn-Iodine batteries offer high capacity but suffer from the polyiodide shuttle effect, where soluble iodine species (e.g., I₃⁻) migrate to the anode, causing capacity decay and low coulombic efficiency [23].

Cation-Anion Strategy: Using Tetramethylammonium Halides (TMAX, X = F, Cl, Br) creates a dual-function additive.

- Cation Role (TMA⁺): The tetramethylammonium cation captures soluble I₃⁻ on the positive electrode, forming a stable solid-phase interhalide complex (TMAI₂X), thereby suppressing the shuttle effect. Concurrently, TMA⁺ adsorbs onto the Zn anode, creating an electrostatic shielding layer that promotes oriented Zn (101) deposition and suppresses dendrite formation [23].

- Anion Role (X⁻): The halide anions (F⁻, Cl⁻, Br⁻) lower the Gibbs free energy differences (ΔG) of the intermediate reaction steps (I⁻ → I₂X⁻ and I₂X⁻ → TMAI₂X), thereby accelerating the conversion kinetics and improving voltage efficiency [23].

Quantitative Performance Data:

Table 1: Electrochemical Performance of ZICBs with TMAX-Modified Electrolytes

| Additive | Specific Current | Average Energy Efficiency | Cycle Life | Capacity Decay Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TMAF | 0.2 A g⁻¹ | 95.2% | 1000 cycles | 0.1% per cycle |

| TMAF | 1 A g⁻¹ | Not Specified | 10,000 cycles | 0.1‰ per cycle |

| TMACl | 0.2 A g⁻¹ | Lower than TMAF | 1000 cycles | Higher than TMAF |

| TMABr | 0.2 A g⁻¹ | Lower than TMAF | 1000 cycles | Higher than TMAF |

Source: [23]

Case Study 2: Regulating SEI Formation in Lithium Metal Batteries

Background: The unstable Solid Electrolyte Interphase (SEI) and lithium dendrite growth on lithium metal anodes lead to low Coulombic efficiency and safety risks [24].

Cation-Anion Strategy: Using Nitrate Salts (KNO₃, NaNO₃) as additives demonstrates a synergistic cation-anion interaction.

- Anion Role (NO₃⁻): The nitrate anion exhibits moderate adsorption energy, reacting with lithium to form an inorganic-rich, high-quality SEI film. This stable SEI prevents continuous electrolyte decomposition and promotes uniform lithium deposition [24].

- Cation Role (K⁺ vs. Na⁺): Research indicates that the cation significantly influences the additive's effectiveness. While KNO₃ and LiNO₃ show comparable and high performance in Li||S batteries, Na⁺ cations can participate in side reactions, forming compounds like Na₂S₂O₃ and NaN₃, which cause active material loss and capacity decay [24].

Key Finding: The compatibility between the additive's cation and the electrode materials is critical; an ill-suited cation can undermine the beneficial role of the anion [24].

Case Study 3: Enabling Metal Electrodeposition in Non-Aqueous Media

Background: Electrodeposition of reactive metals like magnesium is challenging in aqueous media due to hydrogen evolution and narrow electrochemical windows [8] [25].

Cation-Anion Strategy: The selection of Ionic Liquid Cations and Anions determines the feasibility and quality of deposition.

- Role of the Combination: The wide electrochemical window of ILs, a result of their unique cation-anion pairs, allows for the reduction of metals with very negative redox potentials without solvent decomposition. The ionic liquid's structure also affects transport properties (viscosity, conductivity) and interfacial behavior at the electrode [8] [25] [26].

- Operational Parameters: Key factors for successful deposition include temperature (to mitigate viscosity), precursor purity, and cell architecture. The use of elevated temperatures and co-solvents can further enhance ion mobility and deposition uniformity [8].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Evaluating TMAX Additives in Zn-Iodine Batteries

Objective: Assess the efficacy of tetramethylammonium halide (TMAX) additives in suppressing the polyiodide shuttle effect and improving zinc deposition.

Materials:

- Electrolyte: 2 M ZnSO₄ + 0.2 M KI (base electrolyte).

- Additives: Tetramethylammonium fluoride (TMAF), chloride (TMACl), or bromide (TMABr).

- Electrodes: Zinc foil (anode), Carbon felt (cathode).

- Equipment: UV-Vis spectrophotometer, Raman spectrometer, electrochemical workstation.

Procedure:

- Additive Screening:

- Prepare a 10 mM KI₃ solution in water.

- Add 0.1 M of TMAX (TMAF, TMACl, TMABr) to separate vials of the KI₃ solution.

- Observe the formation of a dark green solid precipitate, indicating complex formation [23].

- Centrifuge the mixtures and analyze the supernatants using UV-Vis (288 nm, 350 nm) and Raman spectroscopy (118 cm⁻¹, 136 cm⁻¹ for I₃⁻; 165 cm⁻¹ for I₅⁻) to confirm the reduction of soluble polyiodide signals [23].

- Cell Assembly and Testing:

- Prepare the working electrolyte by adding 0.1 M of the selected TMAX additive to the base electrolyte (2 M ZnSO₄ + 0.2 M KI).

- Assemble coin cells (CR2032) in an argon-filled glovebox using the modified electrolyte.

- Perform galvanostatic charge-discharge testing at specific currents of 0.2 A g⁻¹ and 1 A g⁻¹.

- Monitor cycle life, Coulombic Efficiency, and Energy Efficiency as per Table 1 [23].

- Zn Deposition Analysis:

- Conduct Zn||Zn symmetric cell cycling with the modified electrolyte.

- Analyze the cycled Zn electrodes using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) to observe deposition morphology and X-ray Diffraction (XRD) to confirm the preferred Zn (101) orientation [23].

Protocol: Testing Nitrate Additives in Lithium Metal Batteries

Objective: Systematically evaluate the performance of nitrate and nitrite additives in stabilizing the lithium metal anode.

Materials:

- Base Electrolyte (BE): 1 M LiTFSI in DOL/DME (1:1 v/v).

- Additives: KNO₂, KNO₃, NaNO₂, NaNO₃.

- Electrodes: Lithium metal chips, Copper foil.

- Equipment: Electrochemical workstation, glovebox.

Procedure:

- Electrolyte Preparation:

- Prepare electrolytes with gradient concentrations (0.01 M, 0.05 M, 0.1 M) of each additive in the base electrolyte [24].

- Coulombic Efficiency (CE) Test:

- Assemble Li||Cu half-cells in an argon-filled glovebox.

- Cycle the cells under a current density of 1 mA cm⁻² with a deposition capacity of 1 mAh cm⁻².

- Determine the optimal additive and its concentration based on the highest and most stable CE [24].

- Adsorption Energy Simulation:

- Use molecular simulation software (e.g., GROMACS) to model and compare the adsorption energies of NO₂⁻ and NO₃⁻ anions with Li⁺ ions and on the Li (110) crystal plane [24].

- SEI Characterization:

- After cycling, disassemble cells and harvest the lithium anodes.

- Analyze the SEI composition using X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) to confirm the formation of an inorganic-rich layer (e.g., Li₃N, LiNₓOᵧ) in the presence of NO₃⁻ [24].

Schematic Diagrams of Mechanisms and Workflows

Synergistic Mechanism of TMAX in Zn-Iodine Batteries

Diagram Title: TMAX Additive Synergistic Mechanism

Workflow for Evaluating Electrolyte Additives

Diagram Title: Additive Evaluation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Featured Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Example Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Tetramethylammonium Halides (TMAX) | Dual-function additive: cation suppresses shuttle effect and anode dendrites; anion enhances redox kinetics. | High-energy-efficiency Zn-Iodine batteries [23]. |

| Alkali Metal Nitrates (KNO₃, LiNO₃) | Additive for forming inorganic-rich, stable SEI on lithium metal anodes. Improves Coulombic Efficiency. | Lithium Metal and Li-S batteries [24]. |

| Ionic Liquids (e.g., Phosphonium-based) | Electrolyte solvent with wide electrochemical window for electrodeposition of reactive metals. | Low-temperature electrodeposition of Mg, Nd, and other metals [8] [26]. |

| Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) | Low-cost, tunable non-aqueous electrolyte for electrodeposition and energy storage. | Electrodeposition of Zn, Sn, Ag [25] [27]. |

| Lithium Bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide (LiTFSI) | Conductive salt with high stability, commonly used in organic and ionic liquid electrolytes. | Base electrolyte for Li metal battery testing [24]. |

The Role of Ionic Liquids in Sustainable and Decentralized Energy Solutions

Ionic liquids (ILs), a class of salts that are liquid at or near room temperature, have emerged as cornerstone materials in the development of sustainable and decentralized energy solutions. Their unique properties—including low vapor pressure, high thermal stability, tunable physicochemical characteristics, and wide electrochemical windows—make them exceptionally suitable for advanced electrochemical applications [25] [28]. This document details specific protocols and applications of ILs within two critical domains: the electrodeposition of strategic metal coatings and next-generation battery technologies, providing researchers with practical experimental frameworks to accelerate sustainable energy innovation.

Ionic Liquids in Advanced Electrodeposition

Electrodeposition using ILs enables the recovery and coating of metals that are challenging or impossible to process in aqueous electrolytes due to water sensitivity or narrow electrochemical windows [25].

The table below compares the four primary electrolyte systems used in metal electrodeposition, highlighting the niche advantages of ILs.

Table 1: Comparison of Electrodeposition Electrolyte Systems

| Electrolyte Type | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aqueous Solutions | Mild operating conditions, high solubility to metal salts, good mass transfer [25] | Narrow electrochemical window, hydrogen evolution side reactions [25] | Common metals (e.g., Zn, Cr, Ni) [25] |

| Ionic Liquids (ILs) | Wide electrochemical window, low volatility, high thermal stability, tunable properties [25] [8] | Higher viscosity, higher cost, complex synthesis [25] [7] | Reactive & refractory metals (e.g., Al, Mg, Ge) [25] [8] |

| Deep Eutectic Solvents (DESs) | Biodegradable, low-cost components, easy preparation [25] | Limited number of well-studied formulations, often high viscosity [25] | Zn, Sn, Ag coatings [25] |

| Molten Salts | High conductivity, very wide electrochemical window, no solvation complexity [25] | High operating temperatures, strong corrosivity, high energy consumption [25] | Rare/refractory metals (e.g., W, Mo, Ti) [25] |

Experimental Protocol: Electrodeposition of Metallic Magnesium from Ionic Liquids

Magnesium is a strategic light metal for weight-critical applications and as an anode material in batteries. Its electrodeposition from ILs offers a low-temperature, non-aqueous alternative to energy-intensive industrial processes [8].

2.2.1 Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Magnesium Electrodeposition

| Item | Specification / Function |

|---|---|

| Ionic Liquid | e.g., Imidazolium-based (e.g., [BMIM][TFSI]) or Pyrrolidinium-based (e.g., [C₃mpyr][TFSI]). Serves as the electrolyte solvent [8]. |

| Magnesium Source | Anhydrous MgCl₂ or organomagnesium complex (e.g., Mg(TFSI)₂). Provides Mg²⁺ ions for reduction. Purity >99.9% is critical [8]. |

| Co-solvent | Dry, aprotic solvent (e.g., THF, Diglyme). Used to lower overall electrolyte viscosity and improve ion transport [8]. |

| Substrate | Coin-shaped metal working electrode (e.g., Cu, Ni, or Pt) with a diameter of 1-2 cm. Requires meticulous polishing and cleaning [25]. |

| Counter Electrode | High-purity Mg ribbon or rod. Serves as a reversible Mg/Mg²⁺ source [8]. |

| Reference Electrode | Ag/Ag⁺ or Pt quasi-reference electrode. Provides a stable potential reference in non-aqueous media [8]. |

2.2.2 Step-by-Step Methodology

- Electrolyte Preparation: Inside an argon-filled glovebox (H₂O, O₂ < 1 ppm), dry the chosen IL under vacuum at 80-100°C for 24 hours. Add the magnesium precursor (e.g., 0.1-0.5 M Mg(TFSI)₂) to the dried IL. If needed, add a co-solvent (e.g., 20-40 vol%) to reduce viscosity. Stir the mixture at 60°C until a homogeneous, clear solution is obtained [8].

- Cell Assembly: Assemble a standard three-electrode electrochemical cell inside the glovebox. Insert the prepared working, counter, and reference electrodes into the electrolyte solution. Ensure the cell is hermetically sealed before removal for testing [8].

- Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) Screening: Perform CV at a scan rate of 10-50 mV/s between set potential limits (e.g., -1.0 V to -2.5 V vs. Ref.) to identify the Mg deposition and stripping potentials and assess the reaction's reversibility [8].

- Potentiostatic Deposition: Apply a constant potential, typically slightly more negative than the reduction peak identified by CV, for a duration of 15-60 minutes. The charge passed can be used to estimate the deposit mass [8].

- Post-Processing: After deposition, carefully remove the working electrode, rinse it with a dry solvent (e.g., THF) to remove residual electrolyte, and dry under a stream of inert gas [8].

- Characterization: Analyze the deposit using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) for morphology, X-ray Diffraction (XRD) for crystallinity and phase identification, and Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS) for elemental composition [25] [8].

2.2.3 Workflow Visualization

The following diagram outlines the key experimental and optimization workflow for the magnesium electrodeposition protocol.

Ionic Liquids in Next-Generation Batteries

ILs are pivotal in enhancing the safety and performance of batteries, addressing key challenges in electric vehicles and grid storage.

Market and Performance Data for ILs in Batteries

The global market for ILs in battery applications is growing rapidly, driven by their superior safety profile.

Table 3: Ionic Liquids for Battery Applications: Market and Performance Data

| Parameter / Segment | Details |

|---|---|

| Global Market Size (2024) | USD 111 Million [7] |

| Projected Market Size (2034) | USD 314.2 Million [7] |

| CAGR (2025-2034) | 10.2% [7] |

| Leading IL Type by Market Share (2024) | Imidazolium-based (45.2%), due to electrochemical stability and commercial availability [7] |

| Fastest Growing IL Type | Pyrrolidinium-based, prized for high ionic conductivity and low-temperature performance [7] |

| Largest Application Segment | Electric Vehicle Batteries (30.2% share), driven by demand for safety and high voltage [7] |

| Key Safety Advantage | Non-flammability and non-volatility, significantly reducing fire and explosion risks [7] |

Application Note: ILs in Aluminum-Ion Batteries

Aluminum-ion batteries (AIBs) represent a promising post-lithium technology due to aluminum's abundance, safety, and high theoretical capacity [29].

3.2.1 Research Reagent Solutions

- IL Electrolyte: A mixture of 1-Ethyl-3-methylimidazolium chloride ([EMIm]Cl) and anhydrous AlCl₃ is the standard electrolyte. The molar ratio determines the electrolyte's Lewis acidity and overall performance [29].

- Cathode Material: A graphitic foam or felt is commonly used, as it facilitates the intercalation of chloroaluminate anions (AlCl₄⁻) during charging [29].

- Anode: High-purity aluminum foil.

- Separator: Glass fiber filter, resistant to the corrosive IL electrolyte.

3.2.2 Step-by-Step Cell Assembly and Testing Protocol

- Electrolyte Synthesis: In a glovebox, slowly add anhydrous AlCl₃ to [EMIm]Cl in a molar ratio of 1.1:1 to 1.5:1 (AlCl₃:[EMIm]Cl) with constant stirring and cooling to control the exothermic reaction. The resulting liquid is the active chloroaluminate IL electrolyte [29].

- Electrode Preparation: Punch the aluminum foil and carbon felt into disks. Dry all components under vacuum at 120°C overnight to remove moisture.

- Cell Assembly: In a glovebox, assemble a coin cell or Swagelok-type cell in the sequence of aluminum anode, separator (soaked with electrolyte), and carbon felt cathode. Seal the cell hermetically [29].

- Electrochemical Testing: Perform galvanostatic charge-discharge (GCD) cycling at various current densities (e.g., 100-1000 mA/g) between a fixed voltage window (e.g., 1.0-2.5 V) to evaluate capacity, cycling stability, and rate capability [29].

Emerging Tools and Future Perspectives

AI-Driven Design of Ionic Liquids

The vast chemical space of ILs makes them ideal candidates for AI-accelerated design. A recent study demonstrated the use of a fine-tuned GPT-2 model to generate novel IL structures with optimized properties like high CO₂ solubility and low eco-toxicity [30]. An iterative fine-tuning process, where top-performing generated ILs are fed back into the training set, was shown to progressively improve the properties of the AI-designed molecules [30].

4.1.1 AI Design Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the iterative AI-driven workflow for designing novel ionic liquids.

Challenges and Outlook

Despite their promise, the high cost and complex synthesis of ILs remain barriers to large-scale commercialization [7] [31]. Future research must focus on developing cost-effective, biodegradable ILs and designing integrated processes, such as using ILs for both metal extraction from waste streams and subsequent electrodeposition [32]. Combining AI-driven discovery with robust experimental validation presents a powerful pathway to overcome these challenges and fully unlock the potential of ILs in building a sustainable energy future.

Practical Implementations: Electrodeposition and Battery Electrolyte Applications

Application Note 1: Magnesium Electrodeposition from Ionic Liquids

The recovery of strategic metals like magnesium through sustainable electrochemical routes represents a critical advancement in materials processing for energy and environmental applications. Magnesium's low density (-2.37 V vs. SHE), high volumetric capacity (3833 mAh cm−3), and biocompatibility make it valuable for mobility, energy, and medical applications [8]. Traditional industrial production via thermal reduction of dolomite or electrolysis of anhydrous MgCl2 faces environmental and operational challenges, including high temperatures, significant emissions, and difficulties in precursor dehydration [8]. Ionic liquids (ILs) have emerged as promising alternative electrolytes due to their low volatility, thermal stability, and wide electrochemical windows, enabling efficient electrodeposition in water-free media [8].

Quantitative Analysis of Operational Parameters

Table 1: Key operational parameters for magnesium electrodeposition from ionic liquids [8]

| Parameter | Optimal Range | Impact on Deposition Efficiency |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature | 80°C | Enhances ionic mobility and current density (>1 A dm−2) |

| Viscosity Control | Co-solvent addition | Mitigates transport limitations for uniform ion mobility |

| Precursor Purity | Anhydrous MgCl₂ | Prevents passivation and enables efficient stripping |

| Cell Architecture | Optimized electrode design | Improves interfacial behavior and deposit uniformity |

| Chloride Additives | Tetrabutylammonium chloride | Prevents passivation and enables efficient magnesium stripping |

Experimental Protocol: Magnesium Electrodeposition from Solvate Ionic Liquids

Principle: This protocol describes the reversible electrodeposition and stripping of magnesium from solvate ionic liquid–tetrabutylammonium chloride mixtures, achieving current densities exceeding 1 A dm−2 at 80°C [33].

Materials:

- Magnesium-containing solvate ionic liquids

- Tetra-n-butylammonium chloride (TBACl)

- Argon glovebox (<1 ppm O₂/H₂O)

- DC power source or potentiostat

- Raman spectrometer for structural analysis

- Working electrode: appropriate substrate (e.g., copper, platinum)

- Counter electrode: magnesium ribbon

- Reference electrode: Ag/Ag⁺

Procedure:

- Electrolyte Preparation:

- Prepare solvate ionic liquids under anhydrous conditions within an argon glovebox.

- Analyze solvation structures by Raman spectroscopy to confirm solvent-separated ion pair structure at room temperature.

- Add tetrabutylammonium chloride to the solvate ionic liquids to prevent passivation and enable efficient magnesium stripping [33].

Electrochemical Cell Assembly:

- Assemble a three-electrode electrochemical cell within the argon glovebox.

- Use magnesium ribbon as both counter and reference electrodes, or employ a separate reference electrode (Ag/Ag⁺).

- Ensure all components are thoroughly dried before introduction to the glovebox.

Electrodeposition:

- Maintain electrolyte temperature at 80°C to achieve optimal current densities.

- Apply constant current or potential for deposition, with current densities potentially exceeding 1 A dm−2.

- Monitor deposition efficiency through chronopotentiometry.

Stripping Analysis:

- Perform cyclic voltammetry to study magnesium stripping behavior.

- Analyze the influence of chloride concentration on stripping efficiency.

- Note that addition of TBACl is necessary to prevent passivation and enable efficient stripping [33].

Troubleshooting:

- If passivation occurs during stripping, increase chloride concentration.

- If deposition efficiency is low, optimize temperature and verify electrolyte composition.

- For non-uniform deposits, incorporate co-solvent strategies to mitigate viscosity-related transport limitations [8].

Application Note 2: Critical Metals Recovery from Spent Lithium-Ion Batteries

The recycling of critical elements from spent lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) represents a crucial technological challenge in sustainable resource management. Spent LIBs contain valuable metals, including cobalt (5-20%), nickel (5-10%), manganese (5%), and lithium (1.5-7%), with concentrations significantly higher than in raw ores [34]. Electrochemical recycling technologies offer enhanced selectivity, reduced energy consumption, and superior environmental benefits compared to conventional pyrometallurgical and hydrometallurgical methods [35]. By regulating parameters such as voltage, current, and electrolyte composition, electrochemical methods can selectively dissolve or deposit specific elements, effectively separating multiple metal elements from complex solutions [34].

Quantitative Analysis of Metal Recovery Efficiency

Table 2: Selective electrodeposition performance for cobalt and nickel recovery [36]

| Condition | Applied Potential (V vs Ag/AgCl) | Co/Ni Ratio in Deposit | Purity Achieved |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 M LiCl electrolyte | -0.75 V | 3.18 | Cobalt: 96.4 ± 3.1% |

| 10 M LiCl electrolyte | -0.60 to -0.55 V | Nickel-selective | Nickel: 94.1 ± 2.3% |

| 0.1 M LiCl electrolyte | -0.8 to -0.55 V | 1-2 | Low selectivity |

| PDADMA-modified electrode | Optimization dependent | Tunable selectivity | Polymer-loading dependent |

Experimental Protocol: Selective Cobalt and Nickel Electrodeposition Through Integrated Electrolyte and Interface Control

Principle: This protocol enables molecular selectivity for cobalt and nickel during potential-dependent electrodeposition through synergistic combination of concentrated chloride electrolytes and polyelectrolyte-modified electrodes [36].

Materials:

- 10 M LiCl solution (high purity)

- Poly(diallyldimethylammonium chloride) (PDADMA)

- Cobalt chloride (CoCl₂)

- Nickel chloride (NiCl₂)

- Electrochemical workstation with three-electrode configuration

- Working electrode (e.g., glassy carbon, copper)

- Counter electrode (platinum mesh)

- Reference electrode (Ag/AgCl)

- Lithium nickel manganese cobalt oxide (NMC) cathode material from spent LIBs

- Inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES) for analysis

Procedure:

- Electrolyte Engineering for Speciation Control:

- Prepare 10 M LiCl as background electrolyte to promote formation of distinct metal complexes.

- Confirm formation of anionic cobalt chloride complex (CoCl₄²⁻) while maintaining nickel in cationic form ([Ni(H₂O)₅Cl]⁺) using spectroscopic methods.

- Utilize concentrated chloride to create a separation window of approximately 90 mV between cobalt and nickel deposition potentials [36].

Interfacial Design with Polyelectrolyte Modification:

- Functionalize electrode surface with positively charged PDADMA polyelectrolyte.

- Optimize polyelectrolyte loading to tune cobalt selectivity through electrostatic stabilization of CoCl₄²⁻.

- Characterize modified electrodes using electrochemical impedance spectroscopy.

Sequential Electrodeposition:

- For nickel-selective deposition: Apply moderate potentials (-0.60 to -0.55 V vs Ag/AgCl).

- For cobalt-selective deposition: Apply more negative potentials (-0.65 to -0.80 V vs Ag/AgCl) to leverage anomalous deposition behavior.

- Avoid potentials below -0.80 V vs Ag/AgCl to prevent co-deposition with similar Co/Ni ratios.

Multicomponent Metal Recovery from NMC Cathodes:

- Leach NMC cathode materials from spent LIBs using appropriate hydrometallurgical pretreatment.

- Adjust chloride concentration in leachate to maintain speciation control.

- Perform sequential electrodeposition to recover first nickel then cobalt.

- Analyze deposit composition using ICP-OES and SEM.

Troubleshooting:

- If selectivity decreases, verify chloride concentration and electrode modification quality.

- If deposition efficiency declines, check for competing reactions and optimize applied potential window.

- For industrial application, address background electrolyte costs identified in technoeconomic analysis [36].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key reagents and materials for sustainable metal electrodeposition

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Solvate Ionic Liquids | Magnesium electrodeposition electrolyte | Low volatility, thermal stability, wide electrochemical window |

| Tetrabutylammonium Chloride (TBACl) | Additive for magnesium stripping | Prevents passivation, enables efficient magnesium stripping |

| Concentrated LiCl (10 M) | Electrolyte for Co/Ni selectivity | Enables speciation control: CoCl₄²⁻ vs [Ni(H₂O)₅Cl]⁺ |

| Poly(diallyldimethylammonium chloride) (PDADMA) | Electrode modifier for selectivity tuning | Positively charged polyelectrolyte for electrostatic stabilization |

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) with BMIMTFSI | Organic/IL electrolyte for lithium electrodeposition | Good LiNO₃ solubility, fine grain formation [37] |

| Lithium Nitrate (LiNO₃) | Lithium salt for electrodeposition | Additive that changes solvation structure, reduces dendrites [37] |

These application notes and protocols demonstrate that ionic liquid-based electrodeposition provides a sustainable pathway for recovering magnesium and critical metals from brines and spent batteries. The integration of innovative electrolyte engineering with interfacial design enables selective metal recovery with high efficiency and purity, contributing to circular economy objectives in materials science and energy storage. Future developments should focus on optimizing process parameters for scalability and reducing costs associated with specialized electrolytes to facilitate industrial implementation.

The global transition to renewable energy and decarbonized transportation has generated an extraordinary demand for efficient, safe, and cost-effective energy storage solutions. While lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) have dominated the market for decades, fundamental limitations including resource constraints, safety concerns from thermal runaway, and theoretical energy density ceilings are driving the search for alternatives [38] [39]. Multivalent metal-ion batteries, particularly those based on aluminum and magnesium, have emerged as promising successors due to their abundant raw materials, enhanced safety profiles, and superior theoretical capacities [38] [40].

Aluminum, the most abundant metal in the Earth's crust, offers a high theoretical volumetric capacity of 8046 mAh cm⁻³, approximately four times that of lithium [38]. Its trivalent redox chemistry enables the transfer of three electrons per atom, while its natural abundance translates to significantly lower raw material costs and established recycling infrastructure [40] [39]. Magnesium batteries also present compelling advantages, including a high volumetric capacity of 3833 mAh cm⁻³ and the absence of dendrite formation, which plagues lithium metal anodes [38] [8].

The integration of ionic liquids (ILs) as electrolytes represents a pivotal innovation in realizing the potential of these multivalent battery systems. These solvents, composed entirely of organic cations and various anions, offer negligible volatility, high thermal stability, and wide electrochemical windows, making them ideally suited for stabilizing reactive metal anodes and facilitating efficient ion transport [41] [42] [8]. This Application Note details the operational principles, material requirements, and experimental protocols for developing high-performance aluminum-ion and magnesium batteries using ionic liquid electrolytes, providing researchers with practical frameworks for advancing beyond lithium-based electrochemistry.

Quantitative Performance Comparison of Battery Technologies

The table below summarizes key performance metrics for lithium, aluminum-ion, and magnesium battery technologies, highlighting the comparative advantages and current limitations of each system.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Lithium, Aluminum-Ion, and Magnesium Batteries

| Parameter | Lithium-Ion (LIB) | Aluminum-Ion (AIB) | Magnesium-Ion (MIB) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Volumetric Capacity | ~2040 mAh cm⁻³ [38] | ~8046 mAh cm⁻³ [38] | ~3833 mAh cm⁻³ [8] |

| Abundance in Earth's Crust | ~0.002% [39] | ~8.3% [38] [39] | ~2.33% [8] |

| Raw Material Cost (Metal) | ~$35,000/ton [39] | ~$2,400/ton [39] | Information Missing |

| Typical Energy Density (Current) | 250-300 Wh/kg [39] | 40-70 Wh/kg [39] | Information Missing |

| Safety Profile | Moderate (Flammable electrolyte, thermal runaway risk) [38] | High (Non-flammable ionic liquid electrolytes, air-stable anode) [38] | High (No dendrite formation) [38] |

| Cycle Life (Current) | 500-1500 cycles [39] | >1000 cycles (Research: 88% capacity after 5000 cycles) [43] | Information Missing |

Ionic Liquid Electrolytes: Composition and Function

Ionic liquids are organic salts that are liquid below 100°C. Their unique properties—including high thermal stability, negligible vapor pressure, and wide electrochemical windows—make them superior electrolytes for managing the highly reactive chemistries of aluminum and magnesium anodes [42] [8]. Unlike conventional organic solvents, the ionic nature of ILs allows them to dissolve significant quantities of metal salts while resisting decomposition at high operating potentials.

In aluminum-ion batteries, the most common and effective electrolyte is a mixture of anhydrous aluminum chloride (AlCl₃) and a chloride-containing ionic liquid, such as 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium chloride ([BMIM]Cl) [44]. This combination creates a complex equilibrium where the active chloroaluminate species (e.g., AlCl₄⁻, Al₂Cl₇⁻) form, which are crucial for the reversible plating and stripping of aluminum and for intercalation into the cathode [40]. For magnesium batteries, ILs based on pyrrolidinium (e.g., N-propyl-N-methylpyrrolidinium bis(fluorosulfonyl)imide, [C₃mPyr⁺][FSI⁻]) or glyme-Mg salt mixtures have shown promise in enabling reversible magnesium electrodeposition by forming a stable solid-electrolyte interphase (SEI) that suppresses passivation [42] [8].

A critical challenge overcome by ILs is the formation of a passivating layer on the metal anode surface. In magnesium systems, a common blocking layer of MgO/Mg(OH)₂ prevents Mg²⁺ ion transport. Specific IL anions like [FSI]⁻ facilitate the creation of a Li⁺/Mg²⁺-permeable SEI rich in LiF and other inorganic salts, which allows for sustained ion transport and prevents electrolyte breakdown [42]. Similarly, for aluminum, the chloride-based IL environment naturally prevents the formation of a rigid oxide layer, allowing for highly reversible electrochemistry [40].

Application Note 1: The Aluminum-Ion Battery (AIB)

Working Principle and System Components

The rechargeable aluminum-ion battery typically consists of an aluminum metal anode, a graphitic or composite cathode, and an ionic liquid electrolyte containing chloroaluminate anions [40]. During discharge, aluminum is oxidized at the anode: Al → Al³⁺ + 3e⁻. The Al³⁺ ions then migrate through the electrolyte and intercalate into the cathode material. The corresponding cathodic reaction, for instance in a graphitic cathode, involves the intercalation of chloroaluminate anions (AlCl₄⁻) between the graphene layers [40]. This process is reversed during charging.

Key Materials and Optimization Strategies

- Anode: High-purity aluminum foil (≥99.99%) is typically used. Impurities can lead to unwanted side reactions and increased self-discharge [40]. Alloying aluminum with elements like magnesium (5-10 wt%) has been shown to enhance mechanical integrity through solid-solution strengthening, mitigating microstructural damage from volume changes during cycling and improving cycle life [45].

- Cathode: A major research focus is on developing cathodes with wide interlayer spacing to accommodate large chloroaluminate ions. Graphite, vanadium oxide, and MXene-based composites (e.g., Nb₂CTₓ-MoS₂) are prominent candidates [44] [39]. The composite cathode Nb₂CTₓ-MoS₂ exploits the high conductivity and wide interlayer space of MXene (Nb₂CTₓ) and the pseudo-capacitive buffering capability of MoS₂, which controls volume changes during ion intercalation [44].

- Electrolyte: The standard is a molar mixture of 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium chloride ([EMIM]Cl) and anhydrous AlCl₃. The ratio is critical; a molar ratio of AlCl₃:[EMIM]Cl greater than 1.0 creates a Lewis-acidic environment necessary for the formation of Al₂Cl₇⁻ species, which participate in the cathodic reactions [40].

Detailed Protocol: Fabrication of an AIB Pouch Cell

Objective: To assemble and test a rechargeable aluminum-ion battery pouch cell using a Nb₂CTₓ-MoS₂ composite cathode and an AlCl₃/[BMIM]Cl ionic liquid electrolyte.

Materials:

- Aluminum foil (0.01 mm thickness, 99.99% purity)

- Anhydrous Aluminum Chloride (AlCl₃) (99.99%)

- 1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium chloride ([BMIM]Cl) (≥98.0%)

- Carbon paper (as current collector for cathode)

- Celgard 2500 monolayer polypropylene separator

- Aluminum laminated film for pouch cell

- Nb₂CTₓ-MoS₂ composite powder (synthesized as below)

- Poly(vinylidene fluoride) (PVDF) binder

- N-Methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP) solvent

Synthesis of Nb₂CTₓ-MoS₂ Composite Cathode:

- Synthesize Nb₂CTₓ MXene using a green etching method [44]:

- In a Teflon bottle on an ice bath, prepare an etching solution of 0.1 M FeCl₃ and 1.2 M tartaric acid in deionized water as a complexing agent.

- Slowly add 2 g of Nb₂AlC MAX phase precursor to the solution with continuous stirring.

- Maintain the reaction at 35°C for 48 hours with stirring.

- Wash the resulting sediment repeatedly with deionized water and ethanol via centrifugation until the supernatant pH is ~6.

- Centrifuge at 3500 rpm for 30 minutes to sediment the multilayered Nb₂CTₓ. Decant the supernatant and collect the sediment.

- Add the sediment to a 20% solution of triethylamine (TEA) in water and stir for 6 hours. TEA acts as an intercalant to stabilize the interlayer spacing.

- Finally, wash with ethanol and dry under vacuum to obtain few-layered Nb₂CTₓ.

- Prepare Nb₂CTₓ-MoS₂ Composite via hydrothermal synthesis [44]:

- Dissolve 4.8 g of Na₂MoO₄·2H₂O and a stoichiometric amount of thiourea in 50 mL deionized water with continuous stirring.

- Add 76 mg of the as-prepared Nb₂CTₓ dispersed in 3 mL of poly(dimethyldiallylammonium chloride) (PDDMAC) (20%).

- Adjust the pH of the mixture to 6.5 using HCl.

- Transfer the mixture to a Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave and heat at 180°C for 24 hours.

- Collect the black precipitate, wash thoroughly with water and ethanol, and dry in a vacuum oven.

- Anneal the final product at 400°C under an argon flow.

Electrolyte Preparation (Inside an Ar-filled Glovebox, H₂O & O₂ < 1 ppm):

- Dry the [BMIM]Cl precursor under vacuum at 80°C for 24 hours before use.

- Slowly add anhydrous AlCl₃ powder to the [BMIM]Cl liquid in a glass vial with constant stirring, maintaining the vial in an ice bath to manage the exothermic reaction.

- Aim for a final AlCl₃:[BMIM]Cl molar ratio of 1.3:1 to ensure a Lewis-acidic electrolyte.

Electrode Slurry Preparation and Cell Assembly:

- Prepare the cathode slurry by mixing the active material (Nb₂CTₓ-MoS₂), conducting carbon (Super P), and PVDF binder in a mass ratio of 80:10:10 in NMP solvent. Mix thoroughly to form a homogeneous slurry.

- Coat the slurry onto carbon paper. Dry the coated electrode overnight in a vacuum oven at 80°C.

- Cut the aluminum foil to the desired size for the anode.

- Inside the argon glovebox, stack the electrodes and separator: Al anode | Celgard 2500 separator | Nb₂CTₓ-MoS₂ cathode.

- Place the stack into the aluminum laminated pouch, inject the prepared ionic liquid electrolyte, and seal the pouch using a vacuum sealer.

Electrochemical Testing:

- Perform cyclic voltammetry (CV) typically between 0.1 and 2.5 V at a scan rate of 0.1 mV/s to identify redox peaks.

- Conduct galvanostatic charge-discharge (GCD) cycling at various C-rates (e.g., 0.1C, 0.2C, 0.5C, 1C) within a suitable voltage window (e.g., 0.2-2.5 V) to evaluate capacity, cycle life, and rate capability.

- Perform electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) before and after cycling over a frequency range from 100 kHz to 10 mHz with a small amplitude perturbation to monitor changes in internal resistance.

Application Note 2: The Magnesium Battery

Working Principle and Challenges

Rechargeable magnesium batteries utilize a magnesium metal anode, a intercalation cathode (e.g., chevrel phase Mo₆S₈), and a magnesium-conducting electrolyte. The core reaction involves the reversible plating and stripping of magnesium: Mg ⇌ Mg²⁺ + 2e⁻ [8]. The primary challenge has been developing electrolytes that enable this reversibility without forming a passivating layer on the anode. Conventional electrolytes form a blocking layer of MgO/Mg(OH)₂, preventing Mg²⁺ transport. Ionic liquids, particularly with FSI⁻ anions, help form a conductive solid-electrolyte interphase (SEI) that allows Mg²⁺ transport [42] [8].

Key Materials and Ionic Liquid Electrolytes

- Anode: High-purity magnesium metal. The quality and surface preparation of the Mg foil are critical for consistent performance.

- Cathode: Materials like chevrel phase (Mo₆S₈), vanadium oxide (V₂O₅), and sulfur are being investigated. These materials require structures that allow for the facile diffusion of the Mg²⁺ ion, which has a high charge density and thus strong interaction with the host lattice.

- Electrolyte: ILs based on magnesium borohydride (Mg(BH₄)₂) in glymes or magnesium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide (Mg(TFSI)₂) in pyrrolidinium-based ILs (e.g., [C₃mPyr⁺][FSI⁻]) have shown success. The FSI⁻-based ILs are particularly noted for forming a stable, conductive SEI on the magnesium surface [42] [8].

Detailed Protocol: Magnesium Electrodeposition and SEI Stabilization

Objective: To achieve reversible magnesium plating/stripping and stabilize the Mg anode interface using a [C₃mPyr⁺][FSI⁻]-based ionic liquid electrolyte.

Materials:

- Magnesium foil (high purity)

- N-propyl-N-methylpyrrolidinium bis(fluorosulfonyl)imide ([C₃mPyr⁺][FSI⁻]) ionic liquid

- Magnesium salt (e.g., Mg(TFSI)₂ or Mg(FSI)₂)

- Coin cell or pouch cell hardware

- Glass fiber separator (e.g., Whatman)

Electrolyte Preparation and Anode Pretreatment (In Ar-filled Glovebox):

- Dry the [C₃mPyr⁺][FSI⁻] IL and magnesium salt under vacuum at 80°C for 24 hours.

- Dissolve the magnesium salt in the IL at a typical concentration of 0.3 to 0.5 M.

- Anode Pretreatment (SEI Formation) [42]:

- Immerse the polished magnesium foil in the prepared electrolyte.

- Allow it to react for a predetermined period (from 4 hours to 18 days) without applying an external potential. Studies indicate that a reaction time of ~12 days can lead to the formation of a smoother, more protective SEI layer.

- Remove the foil, gently purge with argon to remove residual electrolyte, and use it as the anode for cell assembly.

Cell Assembly and Testing:

- For symmetric cell tests (Mg | Electrolyte | Mg), assemble coin cells using two pieces of the pretreated Mg foil.

- Perform galvanostatic cycling at a specific current density (e.g., 0.1 to 0.5 mA/cm²). The voltage profile will show a stable overpotential for Mg dissolution (stripping) and deposition (plating) if the SEI is effective.

- For full cells, pair the pretreated Mg anode with a suitable cathode (e.g., Mo₆S₈) and cycle the cell.

- Use X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) and Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) on the cycled anodes to characterize the chemical composition of the SEI, confirming the presence of beneficial components like LiF, MgF₂, and breakdown products of the FSI⁻ anion [42].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for Multivalent Battery Research with Ionic Liquids

| Reagent / Material | Typical Function | Key Characteristics & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Anhydrous AlCl₃ [44] | Electrolyte component for AIBs; forms chloroaluminate anions (AlCl₄⁻, Al₂Cl₇⁻) for charge transport. | Highly moisture-sensitive. Requires handling in inert atmosphere. Lewis acidity dictates electrolyte behavior. |

| [BMIM]Cl / [EMIM]Cl [44] | Ionic liquid solvent/cation for AIB electrolytes. | Must be thoroughly dried before use. The cation influences viscosity, conductivity, and electrochemical stability. |