Ionic Liquids as Solvents: From Green Chemistry Foundations to Advanced Biomedical Applications

This article traces the transformative journey of ionic liquids (ILs) from their discovery as molten salts to their current status as versatile 'designer solvents.' Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug...

Ionic Liquids as Solvents: From Green Chemistry Foundations to Advanced Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article traces the transformative journey of ionic liquids (ILs) from their discovery as molten salts to their current status as versatile 'designer solvents.' Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of ILs, including their unique, tunable physicochemical properties. The scope extends to their methodological applications in diverse fields such as biomass processing, drug delivery, and CO2 capture, while also addressing critical challenges like toxicity, biocompatibility, and solvent recovery. Finally, the article provides a comparative analysis of different IL generations and their validation for sustainable and safe use in pharmaceutical and biomedical innovations, offering a comprehensive resource for leveraging ILs in advanced scientific applications.

From Molten Salts to Designer Solvents: The Evolutionary Journey of Ionic Liquids

The field of ionic liquids, now a major subject of study in modern chemistry, traces its origins to foundational work conducted over a century ago. While contemporary research produces thousands of papers annually, the initial discoveries that established this domain were isolated breakthroughs that went largely unnoticed for decades. This technical examination details the seminal contributions of Paul Walden and other early pioneers who first documented salts that remained liquid at low temperatures, establishing the fundamental principles that would later enable the diverse applications of ionic liquids in green chemistry, electrochemistry, and industrial processes. The historical development of these materials demonstrates how disparate research threads eventually converged to create a unified field characterized by intentional design of ionic systems with specific physicochemical properties [1] [2].

The Walden Breakthrough: Ethylammonium Nitrate

Experimental Context and Motivation

In 1914, Paul Walden documented the first ionic liquid, ethylammonium nitrate ([EtNH3][NO3]), while investigating the relationship between molecular size and conductivity in molten salts. His specific research aim was to identify molten salts that would remain liquid at equipment-compatible temperatures, thereby avoiding the specialized adaptations required for high-temperature experimentation. This practical consideration led him to explore organic ammonium salts with melting points below approximately 100°C, enabling conventional laboratory techniques rather than those needed for traditional inorganic molten salts studied at 300-600°C [1] [2].

Walden's key insight recognized that these low-melting-point salts provided experimental conditions approximating those of conventional aqueous and non-aqueous solvents while maintaining ionic characteristics similar to high-temperature molten salts. This allowed him to apply the established theoretical frameworks of van't Hoff's osmotic theory and Arrhenius's electrolytic dissociation theory to these novel systems, despite their complex association/dissociation behavior [2].

Synthesis Methodology and Characterization

The synthesis of ethylammonium nitrate followed a straightforward neutralization reaction:

Reagents:

- Ethylamine (C₂H₅NH₂)

- Concentrated nitric acid (HNO₃)

Experimental Protocol:

- Combine equimolar amounts of ethylamine and concentrated nitric acid under ambient conditions

- The neutralization reaction proceeds spontaneously: C₂H₅NH₂ + HNO₃ → [C₂H₅NH₃][NO₃]

- Purify the resulting salt to obtain pure ethylammonium nitrate

- Characterize the melting point using standard laboratory equipment

Key Physical Properties:

- Melting point: 12°C [1] [2] [3]

- Appearance: Colorless liquid at room temperature

- Conductivity: Exhibited significant ionic conductivity

Walden's measurements focused primarily on electric conductivity and molecular size (determined via capillarity constant). His analysis revealed that these organic salts at low temperatures exhibited behavior corresponding to experiences with inorganic molten salts at much higher temperatures, with association phenomena complicating the complete dissociation of simple ions [2].

Walden's Experimental Workflow

Post-Walden Developments: The Formative Decades

Following Walden's discovery, the potential of low-melting-point salts remained largely unexploited for nearly four decades, with only isolated developments appearing in the literature. The first significant industrial application emerged in a 1934 patent describing the use of "liquefied quaternary ammonium salts" such as 1-benzylpyridinium chloride and 1-ethylpyridinium chloride for dissolving cellulose at temperatures above 100°C. The resulting solutions enabled chemical modifications of cellulose to produce threads, films, and artificial masses—a herald of modern cellulose processing using ionic liquids [2].

The period immediately following World War II witnessed renewed interest in low-temperature molten salts, particularly for electrochemical applications. In 1948, researchers applied mixtures of aluminium(III) chloride and 1-ethylpyridinium bromide for the electrodeposition of aluminum. The phase diagram for this [C₂py]Br-AlCl₃ system revealed a narrow composition window (63-68 mole percent AlCl₃) where the mixture was liquid at or below room temperature. This system featured eutectics at 1:2 (45°C) and 2:1 (-40°C) molar ratios with a maximum at the 1:1 molar ratio (88°C), attributed to bromochloroaluminate species formation in the melt [1] [2].

Key Historical Developments (1914-1980s)

Table 1: Major Early Developments in Ionic Liquids Research

| Year | Researcher(s) | System/Discovery | Key Properties/Applications | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1914 | Paul Walden | Ethylammonium nitrate [EtNH₃][NO₃] | Mp: 12°C; Protic ionic liquid | First documented room-temperature ionic liquid [1] [2] |

| 1934 | - | Liquefied quaternary ammonium salts | Cellulose dissolution >100°C | First industrial patent applying ionic liquid principles [2] |

| 1948/1951 | Hurley & Weir | [C₂py]Br-AlCl₃ mixtures | Electroplating; Liquid at RT with eutectic at -40°C | Recognized benefits of low MP salts for electrodeposition [1] [2] |

| 1963 | John Yoke | Alkylammonium chlorocuprates | Room-temperature "oils" | Expanded range of accessible ionic liquid systems [1] |

| 1970s | Warren Ford | Tetraalkylammonium tetraalkylborides | Low viscosity; Effects on organic reaction rates | Studied toxicity and antimicrobial activity [1] |

| 1972 | George Parshall | [Et₄N][GeCl₃] and [Et₄N][SnCl₃] | Mp: 68°C and 78°C; Platinum-catalyzed hydrogenation | Early catalytic applications in ionic liquids [1] |

| 1975 | Osteryoung Group | [C₄py]Cl-AlCl₃ | Room-temperature liquid range: 60-67% AlCl₃ | Electrochemistry of organometallic complexes [1] [2] |

| 1982 | Wilkes et al. | 1-Alkyl-3-methylimidazolium chloroaluminates | Wide liquid composition range | Introduced imidazolium cations, now most popular for ILs [1] [2] |

Methodological Advances in Early Ionic Liquid Research

Electrochemical Applications: Chloroaluminate Systems

The replication and extension of early ionic liquid research requires specific methodologies, particularly for handling moisture-sensitive systems like chloroaluminates. The experimental protocol for aluminum electrodeposition developed by Hurley and Weir exemplifies the technical requirements:

Reagents and Equipment:

- 1-Ethylpyridinium bromide ([C₂py]Br)

- Anhydrous aluminum chloride (AlCl₃)

- Inert atmosphere glove box (essential for water-sensitive systems)

- Standard electrochemical cell components

Experimental Protocol:

- Prepare 1-ethylpyridinium bromide through quaternization of pyridine with bromoethane

- Dry all reagents and equipment thoroughly to exclude moisture

- In an inert atmosphere glove box, mix [C₂py]Br and AlCl₃ in a 2:1 molar ratio

- Heat gently (if necessary) to form a homogeneous liquid phase

- Characterize the phase behavior across different composition ratios

- Employ as an electrolyte for aluminum electrodeposition at room temperature

Critical Considerations:

- The [C₂py]Br-AlCl₃ system is only liquid at room temperature at specific compositions

- Water sensitivity necessitates strict exclusion of moisture to prevent decomposition

- Phase diagram analysis reveals optimal composition windows for practical applications [1] [2]

Structural Investigations: Debating Ionic Liquid Organization

Early research on imidazolium-based ionic liquids sparked significant controversy regarding their internal structure, with competing theories requiring specialized investigative approaches:

Conflicting Structural Models:

- Hydrogen-Bonded Network: Proposed interionic interactions primarily through hydrogen bonding [1]

- Stacked Structure: Suggested cations arranged with anions positioned above and below the imidazolium ring plane [1]

Experimental Resolution Methods:

- Raman Spectroscopy: Identify specific ion interactions and coordination environments [1]

- X-ray Crystallography: Determine solid-state structures where possible

- Physical Property Measurements: Correlate structural hypotheses with observed properties

This debate was ultimately resolved by recognizing that imidazolium ring protons can act as hydrogen bond donors only with sufficiently strong hydrogen bond acceptors, while stacked structures dominate with larger anions that are poor hydrogen bond acceptors [1].

The Research Toolkit: Essential Materials for Early Ionic Liquid Research

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Experimental Components in Early Ionic Liquid Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Role | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organic Cations | Ethylammonium, 1-Ethylpyridinium, 1-Butylpyridinium, 1-Ethyl-3-methylimidazolium | Positively-charged component | Bulky, asymmetric structure preventing efficient crystal packing |

| Anions | Nitrate, Halides (Cl⁻, Br⁻), Tetrahalogenoaluminates (AlCl₄⁻, Al₂Cl₇⁻) | Negatively-charged component | Ranging from simple inorganic to complex metal-containing species |

| Metal Salts | Aluminum chloride (AlCl₃), Copper(I) chloride (CuCl), Germanium chloride (GeCl₃) | Anion precursor, Lewis acid component | Forms complex anions; Adjusts Lewis acidity of final ionic liquid |

| Specialized Equipment | Inert atmosphere glove box, Sealed electrochemical cells, Moisture-free glassware | Handling and containment | Essential for moisture-sensitive compositions (e.g., chloroaluminates) |

| Characterization Tools | Conductivity apparatus, Melting point apparatus, Phase diagram analysis | Physical property determination | Key for establishing fundamental ionic liquid behavior |

Early Ionic Liquid Research Components

The pioneering work on ionic liquids from Walden's 1914 discovery through the subsequent decades established fundamental principles that continue to guide research today. Walden's recognition of the relationship between ion size, symmetry, and melting point created the conceptual foundation for the field, while later investigators expanded the chemical diversity and practical applications of these unique materials. The experimental challenges encountered by early researchers—particularly regarding moisture sensitivity and structural characterization—established methodological approaches that would enable the rapid expansion of ionic liquid science in later years. These initial forays into molten salts at ambient temperatures demonstrated the profound implications of intentionally designing ionic systems with specific physicochemical properties, paving the way for the extensive development and application of ionic liquids as designer solvents in modern chemical research and industrial processes.

Ionic liquids (ILs), a class of materials often defined as salts with melting points below 100 °C, have evolved from academic curiosities to cornerstone solvents in green chemistry and pharmaceutical research [4] [5] [6]. Their journey began in 1914 with Paul Walden's report on ethylammonium nitrate, but significant interest emerged with the discovery of air- and water-stable imidazolium-based ILs in 1992 [4] [6]. The defining feature of ILs is their inherent tunability; their physicochemical properties can be precisely tailored by selecting different cation-anion combinations, making them "designer solvents" for specific applications [4] [7] [8]. This guide details the key properties that define ILs as solvents, providing researchers with the foundational knowledge to select and utilize them effectively, particularly in drug development.

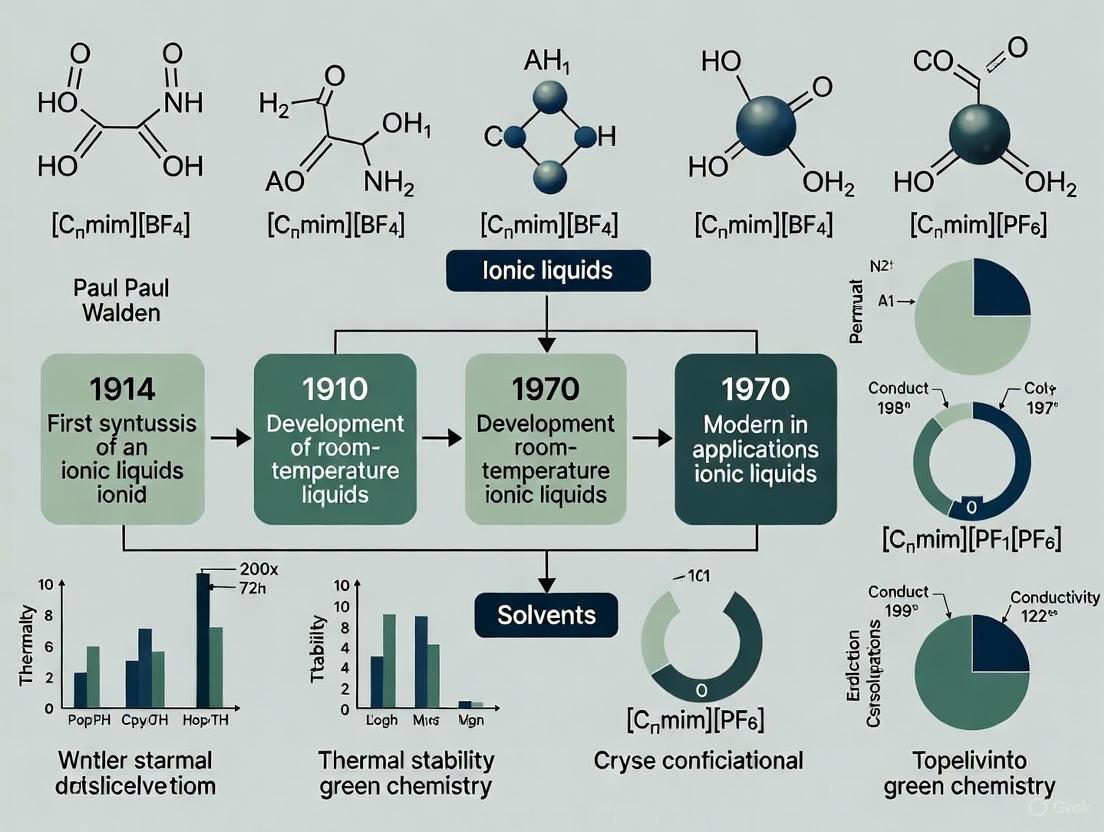

Historical Development and Generations of Ionic Liquids

The evolution of ionic liquids is categorized into distinct generations, each expanding their capabilities and aligning with advancing sustainability goals [7] [9].

Table 1: Generations of Ionic Liquids

| Generation | Key Characteristics | Typical Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| First Generation | Low melting point, high thermal stability; sensitive to water/air [8] [9]. | Electrochemistry, electroplating [8]. | Often toxic, poorly biodegradable [8] [9]. |

| Second Generation | Air- and water-stable; tunable physical/chemical properties [7] [8] [9]. | Catalysis, synthetic chemistry, electrochemical systems [7]. | High toxicity, poor biodegradability [9]. |

| Third Generation | Bio-derived ions (e.g., cholinium, amino acids); low toxicity, good biodegradability [7] [8] [9]. | Biopharmaceutical applications, drug delivery, green chemistry [7] [8]. | - |

| Fourth Generation | Focus on sustainability, biodegradability, and multifunctionality [7]. | Next-generation green technologies, precision medicine [7]. | - |

This evolution has enabled the development of specialized subclasses like Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient Ionic Liquids (API-ILs), where the IL itself is formed from a pharmacologically active ion, and Surface-Active ILs (SAILs), which exhibit amphiphilic properties and can self-assemble [4] [9].

Diagram 1: The evolution of ionic liquids from academic discovery to advanced commercial applications shows a clear trend towards sustainability and specialized functionality.

Core Physicochemical Properties

The utility of ILs as solvents stems from a unique combination of physicochemical properties, which are modular and can be optimized for specific applications.

Tunable Property Spectrum

Table 2: Key Physicochemical Properties of Ionic Liquids

| Property | Description & Impact | Influencing Factors | Typical Range/Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Melting Point | Defines the liquidus range; crucial for application temperature [4] [10]. | Ion size, symmetry, charge delocalization, intermolecular forces [10] [6]. | < 100 °C (definition); many are liquid at room temperature [4] [8]. |

| Viscosity | Affects mass transfer, reaction rates, and pumping efficiency; generally higher than molecular solvents [11] [10]. | Alkyl chain length, anion type, strength of Coulombic & hydrogen-bonding interactions [11] [9]. | 0.3 to over 189 Pa·s [11]. |

| Thermal Stability | Determines the upper temperature limit for applications [4] [10]. | Nature of cation-anion combination [4]. | Up to 672 K (~399 °C) for glycerol-derived ILs [11]. |

| Vapor Pressure | Negligible volatility reduces solvent loss, inhalation risk, and environmental emissions [4] [12] [10]. | Ionic nature and strong Coulombic forces [4]. | Extremely low / non-volatile [4] [12]. |

| Solvation Power | High capacity to dissolve diverse substances, from polar compounds to metals [4] [11]. | Selection of cation and anion [4]. | Tunable from highly polar to non-polar [9]. |

| Polarity | Governs miscibility and solvation behavior; can be finely adjusted [9]. | Choice of ions and alkyl substituents [9]. | Broadly tunable [9]. |

| Density | Important for product separation and flow dynamics [11]. | Molecular weight and packing of ions [11]. | 1.03 – 1.40 g/cm³ [11]. |

| Electrochemical Stability | Defines the voltage window for electrochemical applications [6]. | Redox stability of the constituent ions [6]. | Wide electrochemical window [6]. |

Structure-Property Relationships

The properties of an IL are dictated by the structures of its constituent ions. Cations are typically bulky and organic (e.g., imidazolium, pyridinium, ammonium, phosphonium), while anions can be inorganic or organic (e.g., chloride, [BF₄]⁻, [PF₆]⁻, [Tf₂N]⁻) [8] [10]. The large size and asymmetric nature of the ions prevent efficient crystal packing, leading to low melting points [6]. Properties can be fine-tuned by modifying ion structures; for example, increasing alkyl chain length on a cation can enhance lipophilicity and reduce viscosity to a point, but may also increase toxicity [9].

Experimental Protocols for Key Characterization

For researchers, accurately determining the properties of synthesized or commercial ILs is critical. Below are standard protocols for key measurements.

Melting Point and Thermal Stability

Objective: To determine the melting point (T_m) and thermal decomposition temperature (T_d) of an ionic liquid.

Principle: Melting point is the temperature at which a solid transitions to a liquid. Thermal decomposition temperature indicates the onset of thermal degradation.

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Ensure the IL is pure and thoroughly dried to remove water, which can significantly affect results [10].

- Melting Point (

T_m): Use a melting point apparatus or Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC). In DSC, seal a small sample (2-5 mg) in an aluminum pan and run a heating cycle (e.g., from -50°C to 100°C at 5°C/min underN_2flow). The onset of the endothermic peak corresponds toT_m[10]. - Thermal Decomposition (

T_d): Use Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA). Load 5-10 mg of sample into a platinum pan and heat (e.g., from 25°C to 600°C at 10°C/min underN_2).T_dis typically reported as the onset temperature of mass loss or the temperature at which a certain percentage (e.g., 5%) of mass is lost [11] [10].

Viscosity Measurement

Objective: To measure the dynamic viscosity of an ionic liquid as a function of temperature. Principle: Viscosity is the resistance of a fluid to flow. Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Dry the IL sample completely and store under an inert atmosphere. Viscosity is highly sensitive to water content and air bubbles.

- Instrumentation: Use a rotational rheometer with a cone-and-plate or concentric cylinder geometry. A capillary viscometer can also be used for simpler measurements.

- Measurement: Equilibrate the sample at a set temperature. Apply a controlled shear rate and measure the resulting shear stress. The viscosity is calculated from this ratio. Repeat measurements across a temperature range (e.g., 20°C to 80°C) to model the temperature dependence, which often follows an Arrhenius-like behavior [11] [10].

Solubility and Solvation Power

Objective: To assess the capacity of an ionic liquid to dissolve a target compound (e.g., a poorly soluble Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API)). Principle: The solubility of a solute in a solvent is determined by the balance of intermolecular forces. Methodology:

- Shake-Flask Method: Place an excess amount of the solid API into a vial containing the IL.

- Equilibration: Seal the vial and agitate it in a temperature-controlled shaker bath for a sufficient time (e.g., 24-48 hours) to reach equilibrium.

- Separation: Centrifuge the mixture to separate the undissolved solid from the saturated solution.

- Quantification: Dilute an aliquot of the supernatant with a suitable solvent (e.g., methanol) and analyze the concentration of the dissolved API using a calibrated analytical technique such as High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) or UV-Vis spectrophotometry [4] [11].

Diagram 2: A standard workflow for characterizing the key physicochemical properties of an ionic liquid, highlighting the critical steps from sample preparation to data integration.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Selecting the right ions is the first step in designing an IL for a specific application. The table below catalogs common ions and their functional roles in research.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions: Common Ionic Liquid Components

| Reagent (Ion) | Type | Key Function & Properties |

|---|---|---|

| 1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium ([C₄C₁im]⁺) | Cation | A versatile, widely studied cation; contributes to low melting points and good chemical stability [4] [10]. |

| Cholinium | Cation | A bio-derived, low-toxicity cation from the third generation of ILs; essential for biocompatible applications [8] [9]. |

| Bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide ([Tf₂N]⁻) | Anion | Hydrophobic anion that imparts high thermal and electrochemical stability, and low viscosity [13] [6]. |

| Hexafluorophosphate ([PF₆]⁻) | Anion | Imparts hydrophobicity and is commonly used in extractions and electrochemical applications [4] [10]. |

| Tetrafluoroborate ([BF₄]⁻) | Anion | Offers moderate hydrophilicity and is used in synthesis and catalysis [4] [10]. |

| Docusate | Anion | A pharmaceutically accepted anion used to form API-ILs, enhancing drug solubility and absorption [9]. |

| Amino Acid-based Anions | Anion | Bio-derived, chiral anions used to create low-toxicity, biodegradable ILs (Bio-ILs) [9]. |

| Glycidyl Ethers / Epichlorohydrin | Precursor | Renewable platform molecules for synthesizing tailored, bio-based IL families [11]. |

Ionic liquids represent a paradigm shift in solvent technology, moving from static, single-purpose solvents to dynamic, tunable media defined by their customizable physicochemical properties. Their journey from simple chloroaluminates to sophisticated, bio-inspired fourth-generation ILs underscores their growing alignment with the principles of green and sustainable chemistry. For researchers in drug development and beyond, mastering the relationship between an IL's ionic structure and its emergent properties—such as negligible volatility, thermal stability, and unparalleled solvation power—is the key to unlocking new possibilities in synthesis, analysis, and formulation. As this field progresses, the continued development of biodegradable, non-toxic, and highly functional ILs promises to further solidify their role as indispensable solvents for 21st-century scientific innovation.

Ionic liquids (ILs), organic salts with melting points below 100 °C, have undergone a remarkable evolution since their discovery. Their development is characterized by a distinct generational shift, moving from highly specialized, air-sensitive systems to modern, biocompatible materials designed for integration with biological systems. This journey reflects a broader paradigm in materials science, where the emphasis has moved from fundamental property exploration to targeted functional design, particularly for biomedical and pharmaceutical applications. The history of ILs began over a century ago with the synthesis of ethylammonium nitrate by Walden in 1914, but it was not until the 1980s and 1990s that significant interest grew, leading to the classification of ILs into four key generations [1] [7] [14].

The classification of ILs into generations provides a powerful framework for understanding their historical development and future trajectory. First-generation ILs, primarily explored as green solvents, were dominated by chloroaluminate systems and were often sensitive to air and water [1] [14]. Second-generation ILs introduced enhanced stability and tunable physicochemical properties, expanding their use into catalysis and electrochemistry [7] [14]. The pivotal turn toward biological applications came with the third-generation, which incorporated bio-derived ions to create biodegradable and biocompatible ILs [15] [7]. Today, fourth-generation ILs combine these attributes, focusing on multifunctionality, sustainability, and intelligent design for applications in precision medicine and green technology [7]. This review will trace this generational shift, highlighting the key properties, applications, and experimental methodologies that define each stage, with a particular focus on the breakthrough from air-sensitive salts to biocompatible pharmaceutical tools.

The Historical Pathway: Four Generations of Ionic Liquids

Table 1: Key Characteristics of the Four Generations of Ionic Liquids

| Generation | Time Period | Primary Focus | Example Cations | Example Anions | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | 1914 - ~1990 | Air/Moisture-sensitive solvents | Ethylammonium, Alkylpyridinium | [NO₃]⁻, Chloroaluminates | Electrochemistry, Green Solvents |

| Second | ~1992 - 2000s | Air/Water-stable & tunable properties | 1-Ethyl-3-methylimidazolium [EMIM]⁺ | [BF₄]⁻, [PF₆]⁻ | Catalysis, Lubricants, Electrochemical Systems |

| Third | ~2000 - Present | Biocompatibility & Biodegradability | Choline, Amino Acids | Amino Acids, Fatty Acids, Carboxylates | Drug Formulation, Biomedicine, Pharmaceuticals |

| Fourth | Emerging | Smart & Multifunctional Materials | Functionalized Bio-Ions | Functionalized Bio-Ions | Precision Medicine, Targeted Drug Delivery, Sustainable Tech |

The evolution of ionic liquids is a story of continuous refinement and purposeful design. The first-generation began with Paul Walden's 1914 report on ethylammonium nitrate, but these early melts were largely ignored for decades [1]. A significant rediscovery occurred in the 1950s with Hurley and Weir's work on room-temperature chloroaluminate melts for electroplating [1]. These systems, however, were notoriously difficult to handle, requiring inert-atmosphere glove boxes due to their extreme sensitivity to moisture [1]. This high barrier to entry limited their widespread adoption.

The development of the second-generation was catalyzed by the synthesis of air- and water-stable ILs based on the 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium cation with anions like tetrafluoroborate ([BF₄]⁻) and hexafluorophosphate ([PF₆]⁻) in 1992 [14]. This breakthrough unlocked the potential of ILs as truly tunable "designer solvents" [16]. Their remarkable stability and customizable properties (e.g., polarity, hydrophobicity, viscosity) spurred research across diverse fields, including organic synthesis, catalysis, and lubricants [7] [14]. Despite their versatility, concerns regarding toxicity and poor biodegradability persisted, limiting their use in biomedical fields [15].

The need for safer materials led to the third-generation of ILs. This generation prioritized biocompatibility and sustainability by utilizing ions derived from natural, renewable sources [15] [7]. Choline, an essential B-group vitamin, and amino acids became the cornerstone cations and anions for these bio-ILs (Bio-ILs) [15]. These components are generally recognized as safe (GRAS) by regulatory authorities like the FDA, making them ideal candidates for pharmaceutical applications [15]. The third-generation represents the critical shift from simply exploiting the physical properties of ILs to engineering their chemical structures for specific biological interactions and low environmental impact.

Currently, the emerging fourth-generation of ILs focuses on multifunctionality and smart materials [7]. These ILs are designed to be biodegradable, recyclable, and capable of performing multiple tasks, such as simultaneous drug delivery and biological sensing [7]. They are engineered with tailored functionalities for next-generation applications in precision medicine, advanced energy storage, and sustainable industrial processes, marking the frontier of IL research and development [7].

The Rise of Biocompatible ILs in Biomedicine and Drug Delivery

The advent of third-generation ILs has opened up transformative applications in biomedicine and pharmaceuticals. Their tunable nature allows them to address some of the most persistent challenges in drug development, particularly the poor solubility, low bioavailability, and instability of many therapeutic compounds [17]. By acting as solvents, stabilizers, and permeation enhancers, biocompatible ILs have revolutionized drug delivery strategies.

A primary application is in overcoming solubility barriers. A significant proportion of new drug candidates exhibit poor aqueous solubility, which limits their absorption and efficacy [17]. ILs can dramatically enhance the solubility of these hydrophobic drugs. Furthermore, a powerful strategy is the creation of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient-Ionic Liquids (API-ILs), where the drug molecule itself is incorporated as either the cation or anion of the IL [17]. This approach can convert a crystalline solid drug into a liquid salt, improving its bioavailability and enabling new delivery routes [17].

Another major application is in the stabilization of biopharmaceuticals. Therapeutic proteins, peptides, and nucleic acids are often fragile and prone to denaturation or aggregation. Choline-based ILs, such as choline dihydrogen phosphate ([Chol][DHP]), have demonstrated a remarkable ability to stabilize proteins, preventing unfolding and preserving biological activity [16]. For instance, studies have shown that certain choline ILs can increase the melting point of insulin and monoclonal antibodies, significantly delaying their aggregation [18]. This stabilizing effect is crucial for the long-term storage and transport of biologic drugs.

Transdermal drug delivery has particularly benefited from IL technology. Biocompatible ILs like choline and geranic acid (CAGE) have been developed as effective permeation enhancers [19] [18]. CAGE can fluidize the lipids in the skin's stratum corneum, the main barrier to drug absorption, facilitating the delivery of not only small molecules but also large biopharmaceuticals like insulin and nucleic acids (siRNA, mRNA) [18]. This enables non-invasive, needle-free administration of drugs that would otherwise require injection. The following workflow generalizes the process of developing and evaluating a biocompatible IL-based transdermal system, as exemplified by CAGE.

Finally, ILs have shown intrinsic biological activity. By carefully selecting cation-anion pairs, ILs can be designed to possess inherent antimicrobial or anticancer properties [14]. Their mechanism of action often involves disrupting pathogen cell membranes or interacting with intracellular organelles and biomolecules [14]. This dual functionality—serving as both a drug delivery vehicle and an active therapeutic agent—exemplifies the multifunctional potential of fourth-generation ILs.

Experimental Protocols: Working with Biocompatible ILs

Synthesis of a Choline-Based Bio-IL (e.g., Choline Geranate [CAGE])

The synthesis of biocompatible ILs is typically straightforward. The following protocol for preparing Choline Geranate (CAGE), a well-studied IL for transdermal delivery, is representative [19].

- Objective: To synthesize a biocompatible ionic liquid from choline and geranic acid.

- Principle: A neutralization reaction between a chonium base (choline hydroxide) and a stoichiometric amount of geranic acid.

- Materials:

- Choline hydroxide aqueous solution (e.g., 45% w/w in water)

- Geranic acid (>95% purity)

- Deionized water

- Magnetic stirrer and stir bar

- Round-bottom flask

- Rotary evaporator or vacuum oven

- Analytical balance

- NMR spectrometer for characterization

- Procedure:

- Stoichiometric Calculation: Calculate the required masses of choline hydroxide and geranic acid to achieve the desired molar ratio (a common effective ratio for CAGE is 1:2, choline to geranic acid).

- Mixing: In a round-bottom flask, add the calculated amount of choline hydroxide solution. Place the flask on a magnetic stirrer and begin stirring.

- Acid Addition: Slowly add the calculated mass of geranic acid to the stirring choline hydroxide solution.

- Reaction: Continue stirring the mixture for 12-24 hours at room temperature. The reaction is a simple acid-base neutralization and will proceed to completion.

- Water Removal: Remove the water from the resulting ionic liquid mixture using a rotary evaporator under reduced pressure. Alternatively, dry the sample in a vacuum oven at elevated temperature (e.g., 40-50°C) for several hours.

- Characterization: Confirm the structure and purity of the resulting IL using (^1)H NMR spectroscopy. Determine the water content via Karl-Fischer titration and analyze thermal properties using Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) [19].

Protocol for Evaluating Protein Stability in Aqueous IL Solutions

Assessing the stabilizing effect of ILs on proteins is crucial for their application in biopharmaceuticals [16].

- Objective: To determine the stabilizing effect of a choline-based IL on a model protein (e.g., lysozyme) against thermal aggregation.

- Principle: The stability of a protein in solution with and without IL additives is monitored under thermal stress by measuring turbidity (light scattering) as an indicator of aggregation.

- Materials:

- Model protein (e.g., Lysozyme)

- Biocompatible IL (e.g., Choline Dihydrogen Phosphate, [Ch][DHP])

- Buffer solution (e.g., Phosphate Buffered Saline, PBS, pH 7.4)

- UV-Vis Spectrophotometer with temperature-controlled cuvette holder

- Centrifuge and microcentrifuge tubes

- Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a series of protein solutions (e.g., 1 mg/mL lysozyme in PBS) containing varying concentrations of the IL (e.g., 0.1 M, 0.5 M, 1.0 M). Prepare a control sample with no IL.

- Thermal Stress: Incubate all samples at a denaturing temperature (e.g., 65°C) in a heating block.

- Turbidity Measurement: At regular time intervals (e.g., 0, 10, 20, 30, 60 minutes), remove aliquots from the heated samples. Centrifuge briefly to pellet any large aggregates.

- Absorbance Reading: Transfer the supernatant to a cuvette and measure the absorbance at 360 nm (or 600 nm) using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer. A increase in absorbance at this wavelength is indicative of light scattering from protein aggregates.

- Data Analysis: Plot absorbance versus time for each IL concentration. A lower rate of increase in turbidity in the IL-containing samples compared to the control indicates a stabilizing effect against thermal aggregation.

Table 2: The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for Biocompatible IL Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Example in Use |

|---|---|---|

| Choline Hydroxide / Chloride | Cation precursor for synthesis of biocompatible ILs. Considered non-toxic and "generally regarded as safe" (GRAS). | Base cation in choline-geranate (CAGE) for transdermal delivery [15] [19]. |

| Amino Acids (e.g., Glycine, Alanine) | Serve as either anions or cations for bio-ILs. Provide chiral centers, biodegradability, and low toxicity. | Choline-glycine IL for drug solubilization and antimicrobial activity [15]. |

| Fatty Acids / Carboxylic Acids (e.g., Geranic Acid) | Anion precursors that impart hydrophobicity and specific biological interactions (e.g., permeation enhancement). | Geranic acid in CAGE enhances skin penetration of biologics [19] [18]. |

| Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) | Eutectic mixtures of Lewis/Brønsted acids and bases, often with lower cost and simpler preparation than traditional ILs. | Choline Chloride-Urea DES for solvating poorly soluble drugs or as a reaction medium [15]. |

| Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC) | Instrument for characterizing thermal properties of ILs (melting point, glass transition) and protein stability (melting temperature). | Determining the melting point of a synthesized IL or the increased thermal stability of a protein in [Ch][DHP] [19] [16]. |

| Karl-Fischer Titrator | Essential instrument for accurately determining the water content in hygroscopic ILs, a critical quality attribute. | Measuring and controlling residual water in CAGE after synthesis [19]. |

The journey of ionic liquids from air-sensitive curiosities to sophisticated biocompatible materials underscores a profound shift in materials science. The generational classification provides a clear narrative of this evolution: from first-generation ILs focused on fundamental properties as solvents, to the stable and tunable second-generation, and finally to the transformative third- and fourth-generations designed for integration with biological systems. This progression has been driven by an increasing emphasis on sustainability, functionality, and human health.

The impact of biocompatible ILs in drug delivery and biomedicine is already significant, offering innovative solutions to longstanding challenges such as poor drug solubility, low bioavailability, and the instability of biopharmaceuticals [17]. However, the journey is not complete. Future research will focus on the clinical translation of IL-based formulations, with several choline-derived ILs already advancing into clinical trials [17]. Key challenges that remain include comprehensive long-term biosafety studies, scalable and cost-effective manufacturing processes, and regulatory harmonization for these novel chemical entities [17].

The convergence of IL technology with artificial intelligence, nanomedicine, and additive manufacturing (e.g., 3D-printed drug formulations) presents unprecedented opportunities [17] [7]. AI can accelerate the design of optimal cation-anion pairs for specific therapeutic tasks, while advanced fabrication techniques can enable the creation of personalized IL-based drug delivery systems. As these trends continue, ionic liquids are poised to move from being merely "green solvents" to becoming indispensable components of next-generation precision medicine, fully realizing the potential of the generational shift toward biocompatibility and intelligent design.

The field of ionic liquids (ILs) has undergone a remarkable evolution, transitioning from simple, curiosity-driven molten salts to sophisticated, task-specific materials engineered for advanced applications. This journey is categorized into four distinct generations that reflect the growing understanding of cation-anion diversity beyond traditional imidazolium-based structures [7]. First-generation ILs, primarily studied as novel green solvents, gave way to second-generation ILs designed with specific physicochemical properties for applications in catalysis and electrochemistry. The paradigm truly shifted with third-generation ILs, which incorporated bio-derived and task-specific functionalities for biomedical and environmental applications, culminating in the current fourth-generation ILs that emphasize sustainability, biodegradability, and multifunctionality [7]. This historical progression underscores a fundamental principle: the limitless tunability of IL properties through strategic selection and functionalization of cationic and anionic components. As research expands, moving beyond conventional imidazolium systems has unlocked unprecedented opportunities for designing ILs with precision-engineered functions for applications ranging from pharmaceutical sciences to energy storage and environmental remediation.

Fundamental Chemistry: Cation and Anion Structural Diversity

The physicochemical properties and application potential of ionic liquids are fundamentally governed by the structural diversity of their cationic and anionic components. Understanding this diversity is essential for the rational design of task-specific ILs.

Cationic Architectures Beyond Imidazolium

While imidazolium remains a prevalent cation core, numerous alternative structures offer distinct advantages for specific applications.

Pyrrolidinium and Piperidinium: These saturated, cyclic ammonium cations exhibit enhanced electrochemical stability and wider electrochemical windows, making them particularly valuable for energy storage applications such as lithium-ion and lithium-metal batteries [20]. Their structural rigidity contributes to higher thermal stability compared to their aromatic counterparts.

Phosphonium: Quaternary phosphonium cations demonstrate superior thermal stability (often exceeding 300°C) and chemical inertness toward reactive metals [20]. These properties have enabled their use in demanding applications including aerospace lubricants, hypergolic fuels, and high-temperature industrial processes. Phosphonium-based ILs have shown 30% longer maintenance intervals in industrial bearings within steel mills compared to conventional fluids [20].

Cholinium (Vitamin B4 Derivative): As a bio-derived cation, cholinium offers significantly reduced toxicity and enhanced biodegradability compared to conventional ILs [20]. This biosourced platform aligns with green chemistry principles and has found applications in pharmaceutical formulations and biomass processing.

Pyrrolinium: Recent research has demonstrated the utility of task-specific pyrrolinium cations in analytical chemistry. For instance, 1-(2-hydroxy-3-(isopropylamino)propyl)methylpyrrolinium chloride has been successfully employed for the selective microextraction of pharmaceutical compounds like sertraline from complex matrices including water and urine samples [21].

Ammonium: Including simple structures like ethylammonium nitrate (one of the earliest known ILs with a melting point of 12°C) [22], these cations continue to offer valuable platforms for fundamental studies and applications requiring minimal molecular complexity.

Anionic Diversity and Its Functional Implications

The selection of anions equally dictates IL properties, enabling fine-tuning for specialized applications.

Fluorinated Anions (BF₄⁻, PF₆⁻): These anions provide high conductivity and electrochemical stability, enabling operation at higher voltages (3-5V) in electrochemical devices [20]. However, concerns regarding HF release upon hydrolysis and potential toxicity have prompted research into fluorine-free alternatives.

Bulky, Charge-Diffuse Anions (TFSI, NTf₂⁻): Bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide and similar anions create ILs with low lattice energies, reduced melting points, and enhanced hydrophobicity. Their charge delocalization contributes to wider electrochemical windows and improved stability in demanding electrochemical environments [22].

Amino Acid-Based Anions: These bio-derived anions enhance biocompatibility and sustainability. Alanine-based anions, for example, have been investigated in modular IL libraries for biomedical applications, showing reduced cytotoxicity compared to traditional anions [23].

Solvate Ionic Liquids (SILs): An emerging subclass where cations are chelated by neutral ligands (typically oligoethers like triglyme or tetraglyme) paired with charge-diffuse anions [13]. SILs maintain characteristic IL properties while offering simplified synthesis and cost effectiveness, positioning them as promising candidates for next-generation energy storage applications.

Table 1: Cation and Anion Diversity in Ionic Liquids

| Component | Type/Example | Key Properties | Representative Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cations | Imidazolium (e.g., [CₙMIM]⁺) | Moderate stability, tunable polarity | General solvents, catalysis |

| Pyrrolidinium/Piperidinium | High electrochemical stability | Battery electrolytes, supercapacitors | |

| Phosphonium | Exceptional thermal stability (>300°C) | High-temperature lubricants, aerospace | |

| Cholinium | Low toxicity, biodegradable | Pharmaceutical formulations, green chemistry | |

| Pyrrolinium | Task-specific functionality | Analytical microextraction | |

| Anions | Fluorinated (BF₄⁻, PF₆⁻) | High conductivity, wide EWindow | Electrolytes for energy storage |

| TFSI/NTf₂⁻ | Low lattice energy, hydrophobic | Advanced electrochemical devices | |

| Amino Acid-based (e.g., Ala⁻) | Biocompatible, sustainable | Biomedical applications | |

| Chloride (Cl⁻) | Hydrogen bond accepting | Fundamental studies, synthesis |

Structural-Property Relationships and Toxicity Considerations

The relationship between IL structure and its biological effects represents a critical consideration for pharmaceutical and biomedical applications. Systematic studies using modular IL libraries have revealed that cytotoxicity is predominantly influenced by the cationic alkyl chain length rather than the specific cation head group or anion identity [23]. Research across multiple cell lines (bEnd.3, 4T1, HepG2), 3D cell spheroids, and patient-derived organoids consistently demonstrates that ILs with short cationic alkyl chains (scILs, C1-C4) exhibit minimal cytotoxicity, while those with long chains (lcILs, ≥C8) show dramatically increased toxicity [23].

The mechanism underlying this structure-toxicity relationship involves the formation of IL nanoaggregates in aqueous environments. Cryo-TEM and molecular dynamics simulations reveal that both scILs and lcILs form nanoaggregates (~5 nm for scILs vs. ~12.5 nm for lcILs), but their intracellular trafficking and biological fates differ significantly [23]. scILs are typically restricted to intracellular vesicles, whereas lcILs accumulate in mitochondria, inducing mitophagy and apoptosis. This understanding enables rational design of safer ILs for biomedical applications, with scILs demonstrating 30-80 times greater tolerance than lcILs in murine and canine models across various administration routes (oral, intramuscular, intravenous) [23].

Machine learning approaches are advancing toxicity prediction for ILs. Models using random forest (RF), multi-layer perceptron (MLP), and convolutional neural network (CNN) algorithms have been developed to predict toxicity toward biological systems including Vibrio fischeri, acetylcholinesterase (AChE), and leukemia rat cell lines (ICP-81) [24]. Interpretation tools like SHAP (Shapley Additive exPlanations) analysis quantify the contribution of molecular features to toxicity predictions, facilitating the design of greener ILs with reduced ecological impact.

Task-Specific Applications and Experimental Protocols

Pharmaceutical Analysis and Drug Delivery

Application: Determination of Sertraline in Real Water and Urine Samples

Task-specific pyrrolinium-based ILs enable highly efficient and environmentally friendly microextraction of pharmaceutical compounds [21]. The homogeneous in situ solvent formation microextraction (ISFME) protocol achieves exceptional sensitivity and selectivity through the designed interactions between the IL and target analyte.

Table 2: Research Reagent Toolkit for Pharmaceutical Microextraction

| Reagent/Material | Specification/Function |

|---|---|

| Task-Specific IL | 1-(2-hydroxy-3-(isopropylamino)propyl)methylpyrrolinium chloride; selective complexation with sertraline |

| Hydrophobizing Agent | Sodium hexafluorophosphate (NaPF₆); induces phase separation by increasing IL-analyte complex hydrophobicity |

| Sertraline Standard | Analytical standard for calibration and quantification |

| Real Water Samples | Environmental water matrices for method validation |

| Urine Samples | Biological matrices for clinical application |

| Centrifuge | Phase separation post-hydrophobization (5000 rpm, 5 min) |

| FTIR, NMR, MS | Characterization of synthesized IL and complex |

Experimental Protocol: TSIL-ISFME for Sertraline Determination

IL Synthesis and Characterization: Synthesize 1-(2-hydroxy-3-(isopropylamino)propyl)methylpyrrolinium chloride through nucleophilic substitution reaction. Characterize the structure using FTIR, NMR, and mass spectroscopy techniques to confirm successful synthesis [21].

Sample Preparation: Acidify water or urine samples to pH 3.0 using hydrochloric acid to ensure sertraline exists predominantly in its ionic form, enhancing interaction with the TSIL.

Homogeneous Extraction: Add the hydrophilic TSIL (500 μL) to the aqueous sample (10 mL) containing sertraline. The system remains homogeneous, eliminating phase boundaries and maximizing extraction efficiency. Stir vigorously for 3 minutes to facilitate complex formation between the IL and sertraline.

Phase Separation Induction: Introduce NaPF₆ (100 μL, 10% w/v) as a hydrophobizing agent. The PF₆⁻ counterion exchanges with Cl⁻, increasing the hydrophobicity of the IL-sertraline complex and inducing phase separation.

Collection and Analysis: Centrifuge at 5000 rpm for 5 minutes to complete phase separation. Collect the sedimented IL phase and analyze using HPLC-UV with external standard calibration at 275 nm.

Method Validation: Under optimal conditions, this method achieves a limit of detection (LOD) of 2.4 μg L⁻¹, limit of quantification (LOQ) of 8.0 μg L⁻¹, linear dynamic range of 5.0-200 μg L⁻¹, relative standard deviation of 2.6%, preconcentration factor of 192, and recovery rates of 99.0-103.4% in real samples [21].

Biomedical Applications and Drug Delivery Systems

Application: scIL Nanoaggregates as Insoluble Drug Carriers

The systematic understanding of IL nanoaggregate behavior has enabled their application as carriers for poorly soluble drugs. Short-chain ILs (scILs) with C1-C4 alkyl chains demonstrate excellent biocompatibility and ability to enhance drug bioavailability [23].

Experimental Protocol: Formulation and Evaluation of scIL-Drug Systems

IL Selection and Characterization: Select scILs based on cationic alkyl chain length (C3-C4 recommended for optimal balance of solubilization and biocompatibility). Characterize nanoaggregate formation using cryogenic transmission electron microscopy (Cryo-TEM) and dynamic light scattering (DLS) to confirm size distribution (~5 nm for C3MIMCl) [23].

Drug Loading: Incorporate insoluble drugs (e.g., megestrol acetate, a semi-synthetic progestin) into scIL nanoaggregates using solvent evaporation or direct dispersion methods. Maintain drug:IL ratio of 1:10 (w/w) for optimal loading and stability.

In Vitro Biocompatibility Assessment:

- Evaluate cytotoxicity across multiple cell lines (bEnd.3, 4T1, HepG2) using CCK-8 assay after 24h exposure.

- Validate in 3D models: Treat HepG2 cell spheroids and patient-derived liver cancer organoids with scIL formulations (400 μM) and assess viability using live/dead staining.

- Confirm minimal cytotoxicity for scILs compared to lcILs (C12MIMCl reduces viability to <5%) [23].

In Vivo Tolerance and Bioavailability:

- Administer scIL-drug formulations via oral, intramuscular, and intravenous routes in murine and canine models.

- Monitor tissue distribution and mitophagy/apoptotic markers to confirm superior safety profile of scILs (30-80 times greater tolerance than lcILs).

- Compare bioavailability against commercial formulations; scIL-megestrol acetate demonstrates enhanced bioavailability over commercial tablets in canine models [23].

Energy Storage and Electronics

Application: ILs as High-Voltage Electrolytes

The surging demand for advanced battery technologies, particularly from the electric vehicle sector, has driven the adoption of IL-based electrolytes. ILs offer wider electrochemical windows (3-5V), better thermal stability, and reduced flammability compared to traditional organic electrolytes [20].

Experimental Protocol: Formulating IL Electrolytes for Lithium-Ion Batteries

Component Selection: Prioritize pyrrolidinium cations (e.g., N-methyl-N-propylpyrrolidinium) paired with fluorinated anions (PF₆⁻) or TFSI for their electrochemical stability and conductivity. For solvate ionic liquids (SILs), combine glymes (G3/G4) with lithium salts (LiTFSI) [13].

Electrolyte Formulation: Prepare 1.0 M solutions of lithium salt in the selected IL. Dry under vacuum at 80°C for 24 hours to achieve water content <10 ppm, critical for battery performance and longevity.

Electrochemical Window Determination:

- Use linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) with a three-electrode cell (working: glassy carbon; reference: Ag/Ag⁺; counter: platinum).

- Scan from open circuit potential to ±5V at 1 mV/s.

- Confirm electrochemical window exceeds 4.5V for high-voltage cathode compatibility [20].

Cell Assembly and Testing:

- Fabricate coin cells (CR2032) with high-voltage cathodes (e.g., nickel-rich layered oxides LiNi₀.₈Mn₀.₁Co₀.₁O₂) and lithium metal anodes.

- Include polypropylene separators soaked with IL electrolyte.

- Perform galvanostatic cycling at C/10 rate between 2.5-4.5V for 100 cycles.

- Evaluate capacity retention (>80% after 100 cycles) and Coulombic efficiency (>99.5%) compared to conventional electrolytes.

Future Perspectives and Computational Design

The future of ionic liquid development lies in leveraging advanced computational methods to navigate their vast chemical space efficiently. With theoretical combinations numbering in the billions, only a minute fraction of potential IL structures have been synthesized and characterized [25]. Machine learning approaches are now enabling predictive design of novel ILs with tailored properties.

Conditional variational autoencoders (CVAEs) represent a promising generative approach for expanding IL chemical space. These models can propose novel cation and anion structures with a high likelihood of forming low-melting-point ILs (<373 K) [25]. When coupled with molecular dynamics simulations, this approach has validated that 13 out of 15 generated ILs possess desirable melting characteristics, demonstrating the power of computational prediction in accelerating IL discovery.

The integration of interpretable machine learning models with quantum chemical calculations further enhances our understanding of structure-property relationships. SHAP analysis quantifies the contribution of molecular features to toxicity predictions, while electrostatic potential calculations reveal the structure-activity relationships between IL components and biological effects like acetylcholinesterase inhibition [24]. This multidimensional computational approach provides a robust foundation for the rational design of next-generation ILs with optimized performance and minimal environmental impact.

As research progresses, the expansion beyond traditional imidazolium systems will continue to yield ILs with enhanced functionality, sustainability, and application specificity. The convergence of synthetic chemistry, computational design, and multidisciplinary application knowledge positions ionic liquids as key enablers of technological advancement across pharmaceuticals, energy storage, and environmental technologies.

Harnessing Tunable Properties: Cutting-Edge Applications in Science and Industry

The global shift toward a sustainable, bio-based economy necessitates the development of efficient processes for converting lignocellulosic biomass into valuable products. Among the most promising technological advances is the IonoSolv process, which utilizes protic ionic liquids (PILs) for selective biomass fractionation. The history of ionic liquids (ILs) dates back to 1914 when Paul Walden first reported the synthesis of ethylammonium nitrate [1], a low-melting-point salt that would later be recognized as the first protic ionic liquid. However, ILs remained a scientific curiosity for decades until their rediscovery in the late 20th century, when researchers began exploring their unique properties as green solvents for various applications [1] [26]. The term "ionic liquid" now encompasses a diverse class of salts with melting points below 100°C, characterized by negligible vapor pressure, high thermal stability, and tunable physicochemical properties based on cation-anion combinations [27] [26]. The evolution of IL applications has progressed from early electrochemical studies to their current role in biorefining, positioning the IonoSolv process as a transformative approach for lignocellulose deconstruction within the broader context of sustainable solvent development.

The IonoSolv Process: Fundamental Principles and Mechanisms

The IonoSolv process represents a significant advancement in ionic liquid-based biomass processing, specifically utilizing low-cost protic ionic liquids (PILs) derived from amines and inorganic acids [28] [27]. Unlike conventional pretreatment methods that primarily target cellulose digestibility, IonoSolv selectively dissolves lignin and hemicellulose fractions while leaving cellulose as an intact solid pulp [28]. This selective fractionation enables separate valorization pathways for each biomass component, moving beyond traditional biorefinery models that often treat lignin as a waste product.

The development of IonoSolv emerged from earlier discoveries with aprotic ionic liquids (AILs). In 2002, Swatloski et al. first demonstrated the remarkable ability of ILs to dissolve cellulose [29], opening new pathways for biomass processing. Subsequent research by Pu et al. revealed that certain ILs could also effectively dissolve lignin [29]. These foundational discoveries paved the way for the IonoSolv process, which leverages the unique properties of PILs—simple synthesis via acid-base neutralization, lower cost, and tolerance to moisture—making them particularly suitable for industrial-scale biomass processing [27].

Molecular Mechanisms of Biomass Fractionation

The effectiveness of IonoSolv pretreatment stems from the coordinated action of IL cations and anions in disrupting the complex lignocellulosic matrix:

Anion Functionality: Hydrogen sulfate ([HSO₄]⁻) anions in commonly used PILs like triethylammonium hydrogen sulfate ([TEA][HSO₄]) act as Brønsted acids, catalyzing the cleavage of ether bonds (particularly β-O-4 linkages) in lignin and hydrolyzing hemicellulose [28] [27]. This selective bond cleavage enables the dissolution of lignin and hemicellulose while preserving the cellulose structure.

Cation Interactions: The ammonium-based cations (e.g., [TEA]⁺ or [DMBA]⁺) facilitate penetration into the biomass structure through hydrophobic interactions with lignin aromatics, disrupting π-π stacking and lignin-carbohydrate complexes [29].

Synergistic Effects: The combination of cation and anion actions results in effective delignification and hemicellulose removal, significantly increasing cellulose accessibility for subsequent enzymatic hydrolysis [28] [27].

The following diagram illustrates the mechanism of IonoSolv fractionation and the resulting biomass components:

Diagram 1: IonoSolv Biomass Fractionation Mechanism

Experimental Implementation and Process Optimization

Standard IonoSolv Pretreatment Protocol

Based on established methodologies for processing grassy biomass like Miscanthus × giganteus [28] [30], the following protocol details a representative IonoSolv pretreatment:

Ionic Liquid Synthesis: N,N-dimethyl-N-butylammonium hydrogen sulfate ([DMBA][HSO₄]) is synthesized by dropwise addition of 5M H₂SO₄ (1 mol, 200 mL) to N,N-dimethyl-N-butylamine (1 mol, 101.19 g) in an ice bath with continuous stirring [30]. The reaction proceeds for 5 hours, after which excess water is removed by heating at 40°C under reduced pressure. The water content is adjusted to 20 wt% as measured by Karl Fisher titration [30].

Biomass Preparation: Feedstock is size-reduced using a hammer mill and sieved to a particle size of 1-3 mm to balance pretreatment effectiveness and grinding energy requirements [28].

Pretreatment Reaction: Biomass is mixed with IL at 10-50 wt% loading in a stirred reactor (scale: 10 mL to 1 L) and heated to 120-150°C for 45-90 minutes [28]. Efficient slurry mixing is critical for heat and mass transfer, especially at higher solid loadings.

Fraction Recovery: After pretreatment, the cellulose-rich pulp is separated by filtration and washed with water-acetone mixtures (1:1 v/v) to prevent lignin redeposition [28] [29]. Lignin is recovered from the filtrate by adding water, adjusting pH to 2-3 to protonate phenolic hydroxyl groups, and filtering the precipitate [29]. IL is recycled from the aqueous phase by evaporation or membrane processes [26].

Process Optimization Strategies

Recent research has identified key parameters for optimizing IonoSolv pretreatment:

Table 1: Key Optimization Parameters for IonoSolv Pretreatment

| Parameter | Optimal Range | Impact on Process Efficiency | Scale-up Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biomass Loading | 20-50 wt% | Higher loading (20 wt%) reduces lignin reprecipitation and improves glucose yields due to better heat/mass transfer with efficient mixing [28] | Loadings >20 wt% require powerful stirring systems; impacts reactor CAPEX [28] |

| Particle Size | 1-3 mm | Larger particles (1-3 mm) provide higher glucose yields than fine powders due to reduced surface area for lignin re-precipitation [28] | Reduces energy consumption for biomass grinding by up to 60% [28] |

| Temperature | 120-150°C | Higher temperatures improve delignification but may lead to cellulose degradation and IL decomposition [28] [27] | Requires balance between efficiency and solvent stability; affects energy input |

| IL Water Content | 15-20 wt% | Maintains pretreatment efficiency while reducing IL viscosity and corrosion potential [28] [30] | Enhances process safety and reduces equipment requirements |

Analytical Methods for Characterizing Output Streams

Comprehensive analysis of IonoSolv fractions ensures optimal process control and valorization potential:

Pulp Composition: Gravimetric determination of pulp yield followed by compositional analysis using NREL standard methods to quantify glucan, xylan, and lignin content [28].

Enzymatic Saccharification: Assessment of cellulose digestibility by incubating pulp with commercial cellulase cocktails (e.g., CTec2) in buffer (pH 4.8-5.0) at 50°C for 72 hours, followed by glucose quantification via HPLC [28].

Lignin Characterization: Structural analysis using HSQC NMR to identify interunit linkages (β-O-4, β-β, β-5) and gel permeation chromatography (GPC) for molecular weight distribution [28].

IL Purity and Recovery: Karl Fisher titration for water content, HPLC to monitor sugar and degradation product accumulation, and NMR to assess structural integrity after recycling [26].

Research Reagent Solutions for IonoSolv Processing

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for IonoSolv Experiments

| Reagent/Chemical | Function in Process | Technical Specifications | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Triethylammonium hydrogen sulfate ([TEA][HSO₄]) | Primary pretreatment solvent | Protic IL synthesized from triethylamine + H₂SO₄; cost ~$0.78/kg [28] [27] | Tolerant to biomass moisture; 99% recovery demonstrated [28] [27] |

| N,N-Dimethyl-N-butylammonium hydrogen sulfate ([DMBA][HSO₄]) | Alternative PIL for pretreatment | Protic IL with hydrogen sulfate anion; water content typically adjusted to 20 wt% [30] | Effective for nanocellulose production from pulps [30] |

| Acetone-Water Mixture (1:1 v/v) | Anti-solvent for cellulose precipitation and washing | HPLC grade solvents; mixture optimal for lignin solubility control [29] | Prevents lignin redeposition on pulp during washing; reduces saccharification inhibition [28] |

| Commercial Cellulase Cocktails (CTec2, etc.) | Enzymatic saccharification of cellulose-rich pulp | Standardized enzyme activity; dosage typically 15-20 mg protein/g glucan [28] | Susceptible to IL inhibition; thorough washing of pulp essential [28] [31] |

| Alkaline Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂/NaOH) | Oxidation system for nanocellulose production | 1-3% H₂O₂ with 0.1-0.5M NaOH; solid loading 1:10 g/g [30] | Converts IonoSolv pulps to carboxylated CNCs; 1h reaction sufficient [30] |

Output Valorization and Integrated Biorefinery Applications

Cellulose Valorization Pathways

The cellulose-rich pulp produced by IonoSolv pretreatment serves as a platform material for various value-added products:

Bioethanol Production: High-glucan pulp (≥85% cellulose) enables glucose yields up to 98% after enzymatic hydrolysis, providing optimal feedstock for fermentation [28]. Recent paradigm shifts have transformed lignin from an inhibitor to a potential enhancer in enzymatic hydrolysis systems through structural tailoring [31].

Nanocellulose Production: IonoSolv pulps can be converted to carboxylated cellulose nanocrystals (CNCs) via alkaline H₂O₂ oxidation (1h, 1:10 solid loading), producing electrostatically stable, needle-like CNCs with 58-63% crystallinity [30]. This route eliminates the need for toxic chemicals and complex purification steps associated with conventional CNC production.

Lignin Valorization Opportunities

IonoSolv lignin retains a relatively uncondensed structure with abundant β-O-4 linkages, making it suitable for various applications:

Polymer Precursors: Potential for epoxy resins, dispersants, and surfactants [29].

Carbon Materials: Production of carbon fibers, activated carbons, and composite materials [29] [27].

Aromatic Chemicals: Depolymerization to benzene, vanillin, guaiacol, and other platform chemicals [29].

The following workflow illustrates the integrated valorization pathways for IonoSolv fractions:

Diagram 2: IonoSolv Integrated Biorefinery Workflow

Scale-up Challenges and Sustainability Considerations

Technical Hurdles in Commercial Implementation

Despite promising laboratory results, scaling IonoSolv technology presents several challenges:

IL Recycling and Economics: Efficient IL recovery is critical for economic viability, with targets of ≥97% recovery for ILs costing $2.5/kg [26]. Current recovery methods include antisolvent precipitation, membrane separation, and distillation, each with specific energy and efficiency trade-offs [27] [26].

Materials Compatibility: The acidic nature of PILs like [TEA][HSO₄] necessitates corrosion-resistant reactors, increasing capital costs [27]. Limited data exists on long-term material compatibility at industrial scale.

Water Consumption: Pulp washing requires significant water volumes, creating energy-intensive wastewater treatment demands. Optimization of washing protocols can reduce water use by 30-50% while maintaining saccharification efficiency [28] [26].

Environmental Impact Assessment

The green credentials of IonoSolv processing require careful lifecycle assessment:

Toxicity Concerns: While initially hailed as green solvents, certain ILs have demonstrated environmental persistence and potential ecotoxicity [32]. Recent studies have detected IL residues in environmental matrices, highlighting the need for comprehensive risk assessment [32].

Energy Balance: The low vapor pressure of ILs reduces atmospheric emissions but shifts environmental impacts to energy-intensive recycling processes [26]. Integration with renewable energy sources improves overall sustainability.

Circular Economy Potential: IonoSolv technology aligns with circular economy principles by converting waste biomass into multiple value streams while minimizing waste generation [27] [30].

The IonoSolv process represents a significant maturation in the application of ionic liquids for biomass valorization, building upon a century of IL development since Walden's initial discovery. By enabling selective fractionation of lignocellulosic biomass into high-purity cellulose, lignin, and hemicellulose streams, IonoSolv technology addresses critical bottlenecks in biorefining efficiency and economics. Recent advances in process intensification—including higher biomass loadings, optimized particle sizes, and improved washing protocols—have enhanced the commercial viability of this approach.

Future development should focus on four key areas: (1) designing next-generation ILs with improved recyclability, reduced toxicity, and lower cost; (2) integrating advanced IL recovery technologies such as membrane separation and aqueous biphasic systems; (3) developing standardized analytical protocols for IL purity assessment after recycling; and (4) demonstrating pilot-scale operations to validate technoeconomic models. As research continues to transform lignin from a "barrier component" to a "functional carrier" [31], the IonoSolv process is poised to play a pivotal role in the transition toward circular, carbon-neutral biorefining systems that fully utilize the complex molecular architecture of lignocellulosic biomass.

The development of efficient and safe drug delivery systems represents a paramount objective in modern pharmaceutical research and therapeutic innovation. Conventional delivery platforms face persistent challenges that substantially limit their clinical utility, including poor aqueous solubility of many drug candidates, structural instability under physiological conditions, and nonspecific biodistribution that results in insufficient drug accumulation at target sites while inducing off-target toxicity [17]. These limitations have underscored the urgent need for advanced delivery technologies capable of overcoming multiple pharmacological barriers simultaneously.

The convergence of materials science and biomedical engineering has propelled ionic liquids (ILs) to the forefront of next-generation drug delivery solutions. As organic salts that remain liquid below 100°C, ILs exhibit unparalleled molecular design flexibility owing to their modular cation-anion combinations [17]. This structural tunability enables precise tuning of critical pharmaceutical parameters including solubility, stability, and biocompatibility. The term "designer solvents" aptly describes ILs because their physicochemical properties can be custom-designed through strategic selection of cation-anion pairs, allowing formulators to tailor polarity, hydrophobicity, hydrogen-bonding capacity, and thermal stability for specific pharmaceutical applications [18] [33] [9].

Historical Development and Classification

Evolution of Ionic Liquids

The historical development of ionic liquids spans more than a century, marked by key discoveries that have progressively expanded their pharmaceutical applicability:

- 1914: Paul Walden first reported the physical properties of ethyl ammonium nitrate ([EtNH3][NO3]) with a melting point of 13-14°C, pioneering the concept of ionic liquids [33] [9].

- 1950s: Discovery of halide salt ionic liquids based on mixtures of aluminum chloride and ethyl pyridinium bromide, primarily used for metal deposition and as Lewis acid catalysts [33].

- 1992: Wilkes and Zaworotko developed air- and water-stable imidazolium-based ILs with anions like [BF4] and [PF6], overcoming handling issues associated with earlier generations [33] [9].

- 2007: Introduction of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient-Ionic Liquids (API-ILs) with the synthesis of ranitidine docusate, representing a paradigm shift in pharmaceutical formulation [9].

- Present: Third-generation ILs featuring biologically active ions with low toxicity, reduced manufacturing costs, and good biodegradability suitable for biopharmaceutical applications [9].

Classification of Pharmaceutical ILs

The evolution of ionic liquids has led to the development of several specialized categories for pharmaceutical applications:

Table 1: Classification of Ionic Liquids for Pharmaceutical Applications

| IL Category | Composition Features | Key Characteristics | Pharmaceutical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| First-Generation | Chloroaluminate chemistry | Low melting point, high thermal stability, but sensitive to water and air | Limited due to instability and toxicity |

| Second-Generation | Imidazolium/pyridinium with [BF4], [PF6], [NTf2] | Air and water stable, adjustable properties, but high toxicity | Industrial applications with limited biological use |

| Third-Generation (Bio-ILs) | Cholinium, betainium, amino acid-derived ions | Low toxicity, good biodegradability, biocompatible | Topical, transdermal, and oral drug delivery |

| API-ILs | API as either cation or anion paired with counterion | Enhanced solubility, eliminates polymorphism, improved bioavailability | Direct formulation of active pharmaceuticals |

| SAILs | Long alkyl chains in cation/anion | Surface-active, self-assembling, micelle formation | Solubilization enhancement, nanocarrier systems |

The following diagram illustrates the historical evolution and classification of ionic liquids in pharmaceutical applications:

Mechanisms of Action: Enhancing Solubility and Permeability

Solubilization Enhancement Mechanisms

Ionic liquids employ multiple synergistic mechanisms to enhance the solubility of poorly water-soluble drugs, which represent approximately 80% of new drug candidates and 40% of marketed oral drugs [9]:

Ionic Interaction and Hydrogen Bonding: ILs can form multiple ionic bonds and hydrogen bonds with drug molecules, disrupting the crystal lattice energy and enhancing dissolution [17].

Hydrophobicity Tuning: By adjusting the alkyl chain length on cations or selecting appropriate anions, the hydrophobicity of ILs can be precisely tuned to match the physicochemical properties of specific drug molecules [17] [9].

Surface Activity: Surface Active Ionic Liquids (SAILs) incorporate long alkyl chains that enable self-assembly into micellar structures, providing a hydrophobic core for solubilizing non-polar compounds [9].

Polymorphism Prevention: API-ILs eliminate polymorphism issues associated with solid dosage forms by preventing nucleation and crystal growth through ionic interactions between drug and counterion [9].

Permeability Enhancement Strategies

Ionic liquids enhance drug permeability across biological barriers through several documented mechanisms:

Stratum Corneum Modification: For transdermal delivery, ILs transiently fluidize the lipid bilayers of the stratum corneum, creating temporary pathways for drug permeation without causing permanent damage [18] [34].

Tight Junction Modulation: Certain ILs can reversibly open tight junctions in epithelial barriers, enhancing paracellular transport of macromolecules [17].

Membrane Fluidity Enhancement: ILs interact with phospholipid bilayers to increase membrane fluidity, facilitating transcellular transport of encapsulated drugs [18].

Table 2: Quantitative Enhancement of Drug Properties Using Ionic Liquids

| Drug/Drug Category | IL Formulation | Solubility Enhancement | Permeability Increase | Bioavailability Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrophobic Small Molecules | Imidazolium-based ILs | 5-200 fold increase | 2-8 fold transdermal flux | 3-10 fold increase |

| Proteins/Peptides | Choline-geranic acid (CAGE) | Maintains native structure | 2-4 fold skin penetration | Enables transdermal delivery |

| Nucleic Acids | Lipid-derived ILs | Stable encapsulation >95% | Effective cellular uptake | Demonstrated gene silencing |

| Biologics | Bio-IL nanocarriers | Prevents aggregation >20°C melting point elevation | Crosses biological barriers | Enables oral delivery |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Formulation of IL-Based Transdermal Delivery Systems

This protocol details the preparation of ionic liquid-loaded ethosomes for enhanced transdermal delivery of biopharmaceuticals, based on recently published methodologies [18]:

Materials Required:

- Dimyristoyl-phosphatidylcholine (phospholipid component)

- Choline-based ionic liquid (e.g., choline geranate)

- Drug candidate (e.g., insulin, siRNA, small molecule)

- Ethanol (pharmaceutical grade)

- Phosphate buffer saline (PBS, pH 7.4)

- Rotary evaporator with vacuum source

- High-pressure homogenizer or probe sonicator

- Dynamic light scattering apparatus for size measurement

Procedure:

IL-Ethosome Preparation:

- Dissolve 2% w/v dimyristoyl-phosphatidylcholine in a 30:20:50 ratio of ethanol:ionic liquid:PB7.4

- Hydrate the lipid film with the ethanol-IL-PBS mixture at 35°C for 1 hour with gentle agitation

- Incorporate the drug candidate at this stage for active loading

- Subject the mixture to high-pressure homogenization at 15,000 psi for 3 cycles or probe sonication at 40% amplitude for 5 minutes (30-second pulses)

Characterization:

- Measure particle size and zeta potential using dynamic light scattering (target size: 100-200 nm; PDI <0.25)

- Determine encapsulation efficiency via ultracentrifugation at 100,000×g for 30 minutes and HPLC analysis of supernatant

- Assess in vitro drug release using Franz diffusion cells with regenerated cellulose membranes

Ex Vivo Permeation Studies:

- Use excised human or porcine skin mounted in Franz diffusion cells

- Apply 1 mL of IL-ethosome formulation to the donor compartment

- Maintain receptor phase at 37°C with continuous stirring

- Sample receptor fluid at predetermined intervals (0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 24 h) for drug quantification

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps in developing and evaluating IL-based transdermal drug delivery systems:

Protocol: Synthesis of API-Ionic Liquids

The synthesis of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient-Ionic Liquids represents a sophisticated approach to drug formulation where the active molecule itself becomes part of the ionic liquid structure [17] [9]:

Materials:

- Pharmaceutical compound with ionizable group (acidic or basic)

- Appropriate counterion (e.g., choline, docusate, amino acid derivatives)

- Solvents: methanol, ethanol, dichloromethane (anhydrous)

- Rotary evaporator

- Freeze dryer

- Analytical HPLC for purity assessment

Procedure for Anionic API-ILs:

Acid-Base Neutralization:

- Dissolve the acidic drug (1.0 equivalent) in minimal anhydrous ethanol