Integrating One Health and Green Chemistry: A Sustainable Framework for Pharmaceutical Assessment and Drug Development

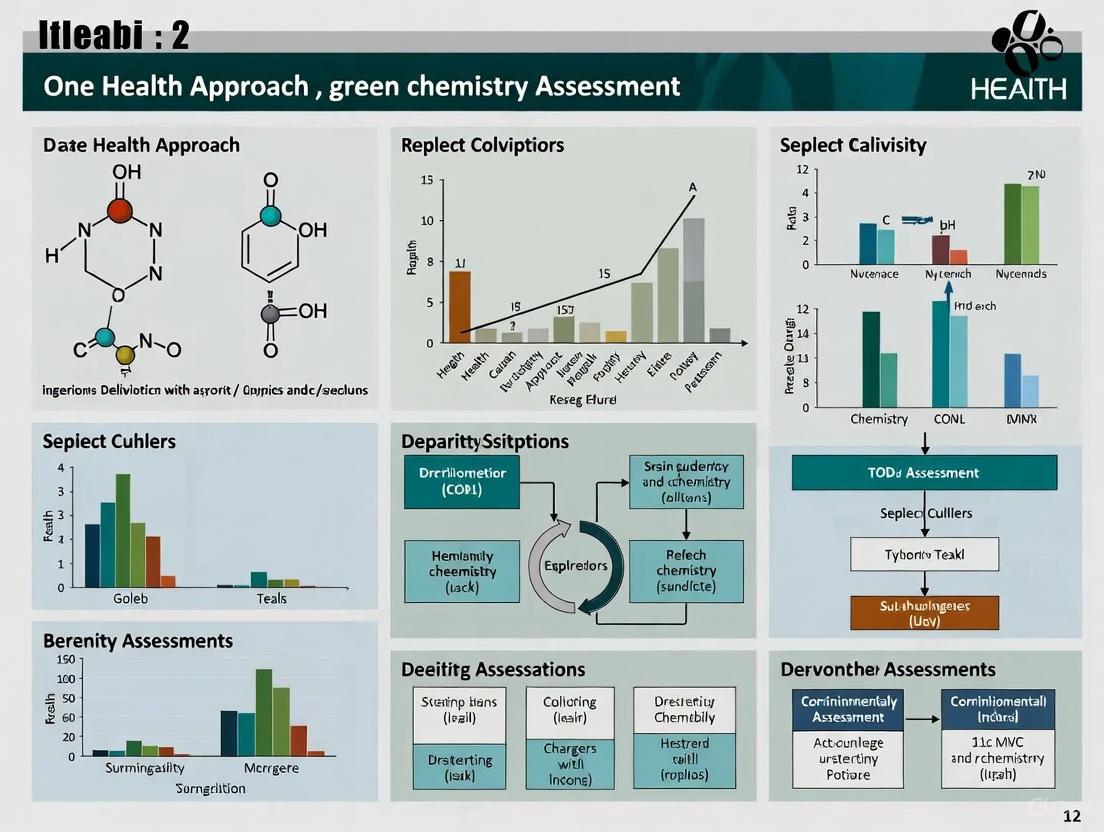

This article presents a comprehensive framework for integrating the One Health approach with green chemistry principles in pharmaceutical assessment and drug development.

Integrating One Health and Green Chemistry: A Sustainable Framework for Pharmaceutical Assessment and Drug Development

Abstract

This article presents a comprehensive framework for integrating the One Health approach with green chemistry principles in pharmaceutical assessment and drug development. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational connections between chemical design, environmental sustainability, and interconnected health outcomes across human, animal, and ecosystem domains. The content covers methodological applications for assessing pharmaceutical sustainability, troubleshooting implementation barriers, and validating approaches through case studies and comparative analysis. By synthesizing cutting-edge research and practical strategies, this resource provides a proactive pathway for reducing ecological footprints and optimizing health outcomes through transdisciplinary collaboration.

The Inextricable Link: How Green Chemistry and One Health Create Sustainable Pharma

The One Health approach and the Twelve Principles of Green Chemistry are two pivotal, synergistic frameworks that address complex global challenges at the intersection of human, animal, and environmental health. One Health is an integrated, unifying approach that aims to sustainably balance and optimize the health of people, domestic and wild animals, plants, and the wider environment, including ecosystems, by recognizing their close interdependencies [1]. Simultaneously, Green Chemistry provides a systematic framework for designing chemical products and processes that reduce or eliminate the use or generation of hazardous substances [2]. The convergence of these two fields represents a transformative paradigm for scientific research and development, particularly in sectors like pharmaceuticals, where it promotes the creation of effective therapeutics that are also environmentally benign and sustainably produced. This guide objectively compares these foundational frameworks, detailing their core principles, synergistic applications in drug development, and the experimental methodologies enabling their integration.

Core Principles: A Comparative Analysis

The following table provides a point-by-point comparison of the foundational principles of Green Chemistry and their specific alignments with the One Health framework.

Table 1: Core Principles of Green Chemistry and their One Health Convergences

| Green Chemistry Principle | Convergence with One Health | Application Example in Drug Development |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Waste Prevention [2] | Reduces environmental pollution, protecting ecosystem and public health [1]. | Use of Process Mass Intensity (PMI) to minimize waste in Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) synthesis [2]. |

| 2. Atom Economy [2] | Conserves natural resources and reduces the environmental burden of chemical processes [1]. | Designing syntheses to maximize incorporation of reactant atoms into the final drug product [2]. |

| 3. Less Hazardous Chemical Syntheses [2] | Directly protects worker safety (human health) and prevents environmental contamination [3]. | Using enzymes as catalysts to avoid toxic reagents, as in the synthesis of Pregabalin [3]. |

| 4. Designing Safer Chemicals [2] | Aims to create products that are effective yet have low toxicity for humans, animals, and the environment [1]. | Development of pharmaceuticals that target pathogens without harming hosts or ecosystems post-excretion. |

| 5. Safer Solvents and Auxiliaries [2] | Minimizes exposure risks for workers and reduces release of persistent environmental pollutants [3]. | Replacement of halogenated solvents with bio-based alternatives like Cyrene [1]. |

| 6. Design for Energy Efficiency | Lowers carbon footprint, mitigating climate change—a key driver of vector-borne disease spread [1]. | Performing reactions at ambient temperature and pressure. |

| 7. Use of Renewable Feedstocks [2] | Enhances sustainability and reduces reliance on finite fossil resources, supporting planetary health [4]. | Using plant-based biomass instead of petroleum to produce platform chemicals like lactic acid for PLA plastics [4]. |

| 8. Reduce Derivatives [2] | Avoids the generation of additional waste streams that could impact occupational and environmental health [1]. | Streamlined synthesis of Tafenoquine that avoids protecting groups [1]. |

| 9. Catalysis [2] | Reduces energy consumption and waste generation, aligning with broader sustainability goals [1]. | Use of enzymatic catalysis for stereoselective synthesis in API manufacturing [1]. |

| 10. Design for Degradation [2] | Prevents the accumulation of chemicals in the environment, protecting wildlife and water resources [5]. | Designing biodegradable chemicals to prevent persistence, as seen with PFAS [5]. |

| 11. Real-time Analysis for Pollution Prevention [2] | Enables immediate hazard detection, preventing exposure incidents and environmental releases [5]. | In-line monitoring to control the formation of hazardous substances during manufacturing. |

| 12. Inherently Safer Chemistry for Accident Prevention [2] | Directly minimizes the potential for industrial accidents, protecting workers, communities, and local ecosystems [3]. | Using less volatile and reactive substances to minimize explosion and release risks. |

Experimental Protocols for Integrated Research

Translating the convergent principles of Green Chemistry and One Health into actionable research requires robust experimental methodologies. The protocols below are designed to generate data that satisfies both environmental and health safety criteria.

Phased ESOH Assessment for New Chemicals

This protocol outlines a phased approach for collecting Environment, Safety, and Occupational Health (ESOH) data alongside the research and development of new chemical entities, aligning with Green Chemistry's preventive principle and One Health's holistic view [5].

Workflow Overview:

Procedure Details:

Technology Readiness Level (TRL) 1 - Conception:

- Objective: Early hazard screening using computational tools.

- Methodology: Employ quantum mechanical models to predict key properties: molecular mass, water solubility, octanol-water partition coefficient (Log Kow), and vapor pressure. Use quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models and read-across approaches to predict toxicity [5].

- Data Output: Estimated values for bioaccumulation potential, environmental fate, and toxicity.

TRL 2-3 - Synthesis:

- Objective: Experimental screening of toxicity with minimal material.

- Methodology: Synthesize gram quantities. Conduct limited in vitro tests using New Approach Methodologies (NAMs), such as high-throughput screening (HTS) for mutagenicity (Ames test) and hepatotoxicity (e.g., using HepG2 cells) [5].

- Data Output: Initial experimental toxicity data to validate in silico predictions.

TRL 4-6 - Testing and Demonstration:

- Objective: Assess hazards from potential human and environmental exposure during scale-up.

- Methodology: Scale up synthesis to kilogram scale. Conduct controlled laboratory animal studies (acute and repeated dose, e.g., 28-day) in rodents. Perform aquatic ecotoxicity tests (e.g., with Daphnia magna or algae) if environmental release is possible [5].

- Data Output: Data for GHS categorization and preliminary risk assessment.

TRL 7-9 - Implementation:

- Objective: Establish occupational exposure limits and complete the safety profile.

- Methodology: Perform subchronic (90-day) rodent studies. Develop and implement industrial hygiene monitoring protocols for manufacturing facilities [5].

- Data Output: Robust dataset for defining occupational exposure limits and completing regulatory requirements for new substances.

Green Chemistry Metrics in API Synthesis

This protocol provides a standard methodology for quantifying the environmental performance of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) synthesis routes, directly applying Green Chemistry principles to achieve One Health outcomes through waste reduction [1] [2].

Workflow Overview:

Procedure Details:

Material Tracking:

- Objective: Accurately record all mass inputs and outputs for a single API synthesis batch.

- Methodology: Precisely weigh and document all materials entering the process: starting materials, reagents, catalysts, and solvents. Weigh the final, isolated, and purified API product. Calculate the total waste generated as follows: Total Waste = (Total Mass Input) - (Mass of API) [1] [2].

Metric Calculation:

- Process Mass Intensity (PMI): Calculate the PMI using the formula: PMI = (Total Mass of Input Materials) / (Mass of API). The ACS Green Chemistry Institute Pharmaceutical Roundtable favors PMI as it provides a comprehensive view of all material inputs [2].

- E-Factor: Calculate the E-Factor using the formula: E-Factor = (Total Mass of Waste) / (Mass of API). A higher E-Factor indicates a greater negative environmental impact [1].

Data Interpretation:

- Objective: Compare the greenness of different synthetic routes.

- Methodology: Compare the calculated PMI and E-Factor values for alternative processes for the same API. A synthesis route with a lower PMI and E-Factor is considered greener, as it is more efficient and generates less waste, reducing its environmental burden [1] [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

This section details key reagents and technologies that facilitate the implementation of Green Chemistry principles within a One Health framework.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Green and Sustainable Chemistry

| Reagent/Material | Function | One Health & Green Chemistry Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Bio-based Solvents (e.g., Cyrene) | Replacement for dipolar aprotic solvents like DMF and NMP. | Safer profile with reduced toxicity and mutagenicity, protecting worker health and the environment [1]. |

| Immobilized Enzymes | Biocatalysts for stereoselective synthesis and hydrolysis. | Enable milder reaction conditions (energy efficiency) and reduce the need for toxic metal catalysts, minimizing waste [1] [3]. |

| Renewable Feedstocks (e.g., Plant-based Sugars) | Raw material for fermentative production of platform chemicals. | Reduce dependence on finite fossil resources, lower carbon footprint, and support a circular bioeconomy [4]. |

| New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) | In vitro and in silico tools for toxicology screening. | Reduce animal testing (ethical alignment), provide rapid, high-throughput hazard data for safer chemical design [5]. |

| Green Polymers (e.g., Polylactic Acid - PLA) | Biodegradable and bio-based material for packaging and medical devices. | Derived from renewable resources (e.g., corn), compostable, and chemically recyclable, reducing plastic pollution and its ecosystem impacts [4]. |

| Computational Toxicology Tools (e.g., EPA T.E.S.T.) | Software for predicting toxicity based on chemical structure. | Allows for early hazard assessment during molecular design, enabling the selection of safer alternatives before synthesis [3]. |

The convergence of Green Chemistry and One Health is not merely theoretical but an actionable and necessary path forward for chemical research and development. The comparative analysis and experimental protocols presented in this guide demonstrate a tangible framework for creating products and processes that are simultaneously efficacious, economically viable, and responsible stewards of human, animal, and environmental health. The ongoing growth of the green chemicals market, projected to reach USD 30.2 billion by 2035, underscores the industrial shift towards these integrated principles [6]. By adopting the comparative frameworks, validated metrics, and specialized reagents detailed herein, researchers and drug developers can systematically embed sustainability and holistic health into the very fabric of their scientific endeavors.

The conventional paradigm for assessing pharmaceuticals has historically been narrowly anthropocentric, focusing predominantly on human safety and efficacy. This perspective often overlooks the interconnected web of impacts that drug manufacturing and disposal have on animal welfare and ecosystem health. A shift towards a holistic view, aligned with the One Health approach, recognizes that the health of humans, domestic and wild animals, plants, and the wider environment are closely linked and interdependent [7]. This approach emphasizes the need for a collaborative, multisectoral, and transdisciplinary approach at local, regional, national, and global levels to achieve optimal health outcomes [7].

Integrating this perspective into pharmaceutical assessment means moving Beyond Anthropocentrism—a philosophical shift that challenges the view that only humans are directly morally relevant and instead emphasizes the intrinsic value of all living beings and ecosystems [8] [9]. In practical terms, this involves evolving from a simple bioequivalence model to a comprehensive lifecycle assessment of pharmaceutical products, considering environmental toxicity, sustainable sourcing, green manufacturing, and end-of-life disposal. This article will compare traditional and holistic assessment frameworks, provide experimental data supporting green chemistry innovations, and detail the methodologies and tools needed for researchers to implement this expanded view.

The Limitation of Traditional Pharmaceutical Assessment

The Anthropocentric Foundation of Current Standards

Traditional pharmaceutical assessment, particularly the framework of bioequivalence and bioavailability, is fundamentally designed to ensure that drug products, whether branded or generic, perform identically in humans. Regulatory definitions from the FDA and WHO focus exclusively on the "rate and extent to which the active ingredient becomes available at the site of drug action" in the human body [10] [11]. This ensures therapeutic equivalence and safety for human patients but implicitly prioritizes human use interests over all other considerations [9]. The ethical framework underlying such regulations can be characterized as anthropocentric, as it prioritizes human health and economic interests, often viewing animals and the environment as resources or testing substrates rather than entities with intrinsic value [12].

Key Concepts in Traditional Assessment

The language of traditional assessment reveals its human-centered focus. Key definitions include:

- Pharmaceutical Equivalents: Drug products that contain the same active ingredient(s), are of the same dosage form, route of administration, and are identical in strength or concentration [10] [13].

- Pharmaceutical Alternatives: Drug products that contain the same therapeutic moiety but are different salts, esters, or complexes, or are different dosage forms or strengths [10] [13].

- Bioequivalence: The absence of a significant difference in the rate and extent to which the active ingredient becomes available at the site of drug action when administered at the same molar dose under similar conditions [11].

These concepts form a closed system focused entirely on human pharmacological response, with no inherent mechanism for considering environmental footprint, ecotoxicity, or animal welfare beyond instrumental human concerns.

Documented Failures of the Narrow Model

The limitations of this narrow model are evident in documented bioequivalence problems with certain drug classes, including chiral drugs, poorly absorbed drugs, and drugs with complex delivery mechanisms [11]. Furthermore, this approach has facilitated regulatory frameworks that prioritize human benefit, such as the 3Rs framework (Replace, Reduce, Refine) in animal experimentation, which, while aiming to be humane, ultimately "safeguard animal welfare only as far as given human research objectives permit" [9]. This effectively subordinates animal interests to human research goals, demonstrating the anthropocentric prioritization embedded in current systems.

The One Health Framework: A Holistic Alternative

Principles of One Health

The One Health concept provides a robust alternative framework. It formally "recognises the complex connections between the health of people, animals, plants, and our shared environment" [7]. This is not merely an ecological concept but a comprehensive approach to governance and research that requires collaborative, multisectoral, and transdisciplinary work at all levels. It aims to "prevent, predict, and respond to health threats" holistically, understanding that our health is deeply intertwined with the health of the natural world and the animals we share it with [7].

Operationalizing One Health in the Pharmaceutical Sector

The European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) exemplifies how to operationalize One Health in a regulatory context. Its work spans multiple key areas crucial for a holistic pharmaceutical assessment [7]:

- REACH: Evaluating scientific information and identifying substances of very high concern.

- Biocidal Products: Ensuring safe use and efficacy of disinfectants and preservatives.

- Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs): Managing chemicals that pose significant health risks and persist in the environment.

- Microplastics Restriction: Addressing how microplastics contaminate water and affect ecosystems, wildlife, and human health.

A powerful example of this approach in action is the joint azole fungicides investigation, a collaboration between ECHA, the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), the European Environment Agency (EEA), the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), and the European Medicines Agency (EMA). This initiative investigates the impact of azole fungicides on the development of azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus, a concern for both agriculture and human health, demonstrating the interconnectedness of environmental and medical concerns [7].

Philosophical Underpinnings: Moving Beyond Anthropocentrism

The philosophical movement to Beyond Anthropocentrism provides the ethical foundation for integrating One Health into pharmaceutical assessment. This perspective challenges the "belief that human beings are the most important and central beings in the world" [12]. Alternatives to anthropocentrism include:

- Ecocentrism: Emphasizes the interconnectedness and interdependence of all living beings and ecosystems [12].

- Biocentric Ethics: Argues that all living beings have inherent value and moral rights [12].

- Posthumanism: Challenges the idea that human beings are the central beings in the world [12].

This philosophical shift is not merely theoretical but has practical implications for how we design, assess, and regulate pharmaceuticals, moving from a human-centered risk-benefit analysis to a comprehensive evaluation that considers all stakeholders in the global ecosystem.

Comparative Analysis: Traditional vs. Holistic Assessment

The following table contrasts the core dimensions of traditional pharmaceutical assessment against a holistic, One Health-aligned model.

| Assessment Dimension | Traditional (Anthropocentric) Model | Holistic (One Health) Model |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Human safety and efficacy only [11] | Interconnected health of humans, animals, ecosystems [7] |

| Ethical Foundation | Anthropocentrism: Only humans have direct moral standing [9] | Non-anthropocentrism: Animals, ecosystems have intrinsic value [8] [12] |

| Regulatory Scope | Bioequivalence, pharmaceutical equivalence/alternatives [10] [11] | Full lifecycle assessment: sourcing, production, use, disposal [7] [14] |

| Environmental Consideration | Limited or absent | Central concern; includes ecotoxicity, persistence, carbon footprint [7] [14] |

| Animal Testing Ethics | 3Rs within human research constraints (instrumental value) [9] | Acknowledges animal welfare as intrinsic value; pushes for alternatives [9] |

| Representative Initiative | FDA Bioequivalence Standards [11] | EU Cross-Agency Task Force on One Health [7] |

This comparison reveals that the holistic model does not simply add environmental concerns to the existing framework but fundamentally reconceives the boundaries and priorities of pharmaceutical assessment.

Green Chemistry Innovations: Quantitative Evidence for a Holistic Approach

The adoption of green chemistry principles provides compelling, data-driven evidence for the viability and benefits of a holistic approach. The following table summarizes quantitative environmental benefits achieved by winners of the 2025 Green Chemistry Challenge Awards, illustrating the tangible advantages of sustainable design.

| Innovation Category | Company/Institution | Key Innovation | Quantitative Environmental Benefit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Greener Synthetic Pathways | Merck & Co. [14] | Biocatalytic process for Islatravir (HIV-1 antiviral) | Replaced a 16-step clinical supply route with a single biocatalytic cascade, eliminating organic solvents [14] |

| Academic Innovation | Scripps Research Institute [14] | Air-stable nickel catalysts replacing palladium | Eliminates energy-intensive processes needed to keep traditional catalysts stable [14] |

| Chemical & Process Design for Circularity | Pure Lithium Corporation [14] | Brine to Battery lithium metal production | Reduces energy and water use versus existing lithium metal production [14] |

| Design of Safer Chemicals | Cross Plains Solutions [14] | SoyFoam (PFAS-free firefighting foam) | 70% biobased, certified readily biodegradable, free of PFAS [14] |

| Climate Change | Future Origins [14] | Fermentation process for fatty alcohols (palm oil alternative) | Lowers global warming potential by ~68% compared to conventional methods [14] |

| Cumulative Impact (All 2025 Winners) | ACS Green Chemistry Institute [14] | Multiple technologies | Eliminated 830 million lb of hazardous chemicals, saved 21 billion gal of water, prevented 7.8 billion lb of CO₂ release [14] |

These innovations demonstrate that moving beyond anthropocentrism in pharmaceutical and chemical development is not only ethically desirable but also technologically feasible and economically beneficial. The significant reductions in hazardous waste, water use, and carbon emissions contribute directly to the health of ecosystems and non-human organisms, aligning assessment outcomes with One Health principles.

Experimental Protocols for Holistic Assessment

Protocol 1: Assessing Environmental Fate and Ecotoxicity

Objective: To evaluate the adverse effects of an Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) on aquatic ecosystems and its potential for bioaccumulation. Methodology:

- Acute Aquatic Toxicity Testing:

- Test Organisms: Use at least three species representing different trophic levels: a freshwater alga (Pseudokirchneriella subcapitata), a freshwater crustacean (Daphnia magna), and a fish (Danio rerio).

- Procedure: Expose organisms to a range of API concentrations in controlled aquatic mesocosms. The exposure period is 48 hours for Daphnia and 96 hours for fish.

- Endpoint: Determine the lethal concentration for 50% of the population (LC50) or the effect concentration for 50% of the population (EC50).

- Biodegradation Study:

- Procedure: Inoculate a solution of the API in a mineral medium with activated sewage sludge. Incubate in the dark at 20°C while stirring.

- Analysis: Monitor the removal of dissolved organic carbon over 28 days via high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC).

- Endpoint: Calculate the percentage of biodegradation; >70% is considered readily biodegradable.

- Bioaccumulation Potential:

- Procedure: Expose fish to a sublethal concentration of the API for 28 days, followed by a depuration period in clean water.

- Analysis: Measure API concentration in fish tissue at regular intervals using mass spectrometry.

- Endpoint: Calculate the Bioconcentration Factor (BCF). A BCF >2000 indicates high bioaccumulation potential.

Protocol 2: Comparative Life Cycle Assessment (LCA)

Objective: To quantify and compare the cumulative environmental impacts of a traditional pharmaceutical process versus a green chemistry alternative across its entire life cycle. Methodology:

- Goal and Scope Definition: Define the functional unit (e.g., "production of 1 kg of high-purity API"). Set system boundaries from raw material extraction (cradle) to API factory gate.

- Life Cycle Inventory (LCI): Collect data on all relevant energy and material inputs (e.g., solvents, reagents, water, electricity) and environmental releases (e.g., GHG emissions, hazardous waste, wastewater) for both processes.

- Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA): Use established models (e.g., TRACI, ReCiPe) to translate inventory data into potential environmental impacts. Core impact categories must include:

- Global Warming Potential (kg CO₂ equivalent)

- Water Scarcity (m³ water equivalent)

- Ecotoxicity (kg 2,4-D equivalent)

- Human Toxicity (kg 1,4-DB equivalent)

- Fossil Resource Scarcity (kg oil equivalent)

- Interpretation: Analyze results to identify environmental hotspots and validate the superiority of the green alternative. The LCA must comply with ISO 14040/14044 standards.

Visualizing the Holistic Assessment Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the integrated, multi-disciplinary workflow required for a holistic pharmaceutical assessment, contrasting it with the traditional linear path.

Holistic vs Traditional Drug Assessment

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methods

Implementing a holistic assessment requires specific reagents and methodologies. The following table details key solutions for evaluating environmental and ethical impacts.

| Research Reagent/Method | Primary Function in Holistic Assessment |

|---|---|

| Activated Sewage Sludge | Inoculum for ready biodegradability testing (OECD 301); assesses the breakdown of APIs in wastewater treatment plants and natural environments [7]. |

| Daphnia magna (Crustacean) | Model organism for assessing acute aquatic toxicity (EPA Test 850.1010); represents secondary consumers in freshwater ecosystems [7]. |

| In Vitro 3D Human Tissue Models | Non-animal method (NAMs) for assessing dermal corrosion/irritation; aligns with the "Replace" principle of the 3Rs, reducing animal use [9]. |

| High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry (HRMS) | Detects and quantifies trace levels of APIs and their metabolites in complex environmental samples (water, soil, biota) for exposure and fate studies. |

| Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) Software | Models the cumulative environmental impacts (e.g., carbon footprint, water use) of a drug product from raw material extraction to disposal [14]. |

The evidence presented underscores an unavoidable conclusion: the traditional anthropocentric model of pharmaceutical assessment is no longer sufficient. A holistic framework, grounded in the One Health approach and the ethical perspective of Beyond Anthropocentrism, is scientifically feasible, ethically necessary, and environmentally imperative. The quantitative successes of green chemistry innovations prove that designing for broader ecological well-being does not hinder progress but rather enhances sustainability and resilience. For researchers and drug development professionals, adopting this expanded view requires new tools and collaborations, but the outcome is a pharmaceutical enterprise that truly promotes the health of the entire planet—human, animal, and environmental alike.

The concept of "chemical footprints" represents the measurable presence and impact of synthetic chemicals in biological systems and the environment, providing critical evidence of exposure and potential health risks across species and ecosystems. Within the framework of One Health—an integrated, unifying approach that seeks to sustainably balance and optimize the health of people, animals, plants, and their shared environment—understanding these footprints becomes paramount [7]. The One Health perspective recognizes that the health of humans, domestic and wild animals, plants, and the wider environment are closely linked and interdependent [1]. This approach encourages collaboration among diverse disciplines, providing more sustainable knowledge and better constituency in health policy [1].

Chemical footprints manifest through biomarkers—objective, measurable indicators of biological processes, exposure events, or susceptibility to chemical agents [15] [16]. These biomarkers serve as early warning systems, detecting chemical exposures and their biological effects before overt damage occurs. The systematic study of biomarkers has experienced significant growth over the past 30 years, enabling researchers to better understand the impact of various environmental pollutants on living organisms and ecosystems [16]. By examining chemical footprints through advanced biomonitoring techniques, scientists can assess the nature and extent of exposure, identify alterations occurring within an organism, and evaluate underlying susceptibility [16].

Biomarkers as Chemical Footprint Evidence: Categories and Significance

Classification of Biomarkers in Toxicological Assessment

Biomarkers serve as essential tools in monitoring toxicology and risk assessment of environmental pollutants by providing early and specific endpoints [16]. In toxicology, biomarkers are compartmentalized into three distinct categories delineated as markers of exposure, effect, and susceptibility [16]. Each category captures different points along the continuum from external exposure to pathological outcome, offering unique insights into the complex interplay between chemicals and biological systems.

An exposure biomarker signals prior interaction with a chemical; this interaction could involve an external substance, a resultant product from the interplay between a xenobiotic molecule and endogenous constituents, or a modification that alters the state of the target molecule [16]. These biomarkers are typically quantified in bodily fluids or tissues and provide concrete evidence of a chemical footprint within a biological system. Examples include metabolites of environmental toxicants, protein adducts, and DNA lesions [15].

An effect biomarker denotes the presence (and degree) of a biological response following exposure to a chemical [16]. This response could manifest as an endogenous constituent, a gauge of the system's functional capacity, or a modified state recognized as impairment or disease. These biomarkers connect chemical exposure to early biological changes, often before clinical symptoms emerge.

A susceptibility biomarker indicates an increased sensitivity to a chemical's effects, which could emerge as either the presence or absence of an endogenous element or an aberrant functional response to an administered challenge [16]. These biomarkers help explain individual variations in response to similar chemical exposures.

Table 1: Categories of Biomarkers in Chemical Footprint Research

| Category | Definition | Examples | Analytical Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure Biomarkers | Indicate interaction with environmental chemicals | Metabolites (e.g., SPMA for benzene [15]); Protein/DNA adducts [15]; Heavy metals in hair [15] | LC-MS/MS [15]; Accelerator Mass Spectrometry [15]; 32P-postlabeling [15] |

| Effect Biomarkers | Measure biological response to chemical exposure | Oxidative stress markers (MDA [17]); DNA damage (Comet assay [17]); Enzyme activities (SOD, CAT [17]) | Spectrophotometry; Electrophoretic methods; Enzyme activity assays |

| Susceptibility Biomarkers | Identify increased sensitivity to chemical effects | Genetic polymorphisms; miRNA profiles [16]; tRNA modifications [15] | Genotyping; Microarray analysis; Sequencing technologies |

The Biomarker Continuum: From Exposure to Disease

The biological events following chemical exposure represent a continuum from initial external exposure to subsequent physiological reactions [16]. This cascade begins when exposure to environmental chemicals found in food, drinking water, and air instigates a series of biological events within the body [16]. These reactions may signal the presence of the chemical, adverse health outcomes, or increased toxicity influenced by individual characteristics. The biological processes set in motion by chemical exposure have the potential to incite cellular, molecular, organ, or systemic responses, alongside a range of biochemical, physiological, and morphological changes [16].

The following diagram illustrates this continuum from exposure to clinical disease, highlighting key points where different biomarker types provide evidence of chemical footprints:

Evidence of Chemical Footprints: Key Studies and Findings

Documented Human Exposure to Widespread Chemicals

Numerous studies have provided concrete evidence of chemical footprints in human populations, demonstrating the pervasive nature of synthetic chemical exposure. A landmark investigation by Greenpeace Netherlands conducted in 2004 analyzed blood samples from 91 participants for six groups of hazardous chemicals: phthalates, brominated flame retardants, organotins, artificial musks, alkylphenols, and bisphenol-A [18]. The study concluded that hazardous chemicals were present in the blood of all participants, providing unambiguous evidence that chemicals contained in normal consumer products can and do enter the human body [18].

Further evidence comes from biomonitoring studies of specific chemical classes:

Phthalates: These plasticizers and additives found in many consumer products demonstrate widespread human exposure. Biomonitoring studies have detected phthalate metabolites in urine, serum, amniotic fluid, breast milk, semen, and saliva [15]. Epidemiological studies have linked high exposure to phthalates with various health effects including sex anomalies, endometriosis, altered reproductive development, early puberty and fertility issues, breast and skin cancer, allergy and asthma, overweight and obesity, insulin resistance, and type II diabetes [15].

Heavy Metals: Research on children in the Mid-Ohio Valley measured hair concentrations of manganese, lead, cadmium, and arsenic, finding detectable levels of all metals studied [15]. The study found that hair Mn and Pb levels were comparable and approximately 10-fold higher than hair Cd and As levels, with differences observed between male and female subjects and along hair segments [15].

Benzene: Monitoring of benzene exposure through the biomarker S-phenyl-mercapturic acid (SPMA) in urine has demonstrated that active smoking represents a major exposure source, though nonsmokers are also exposed to airborne concentrations of this carcinogen [15].

Table 2: Evidence of Chemical Footprints in Human Populations

| Chemical Class | Biomarkers Measured | Study Population | Key Findings | Health Implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consumer Product Chemicals [18] | Phthalates, BFRs, organotins, artificial musks, alkylphenols, BPA in blood | 91 volunteers (Greenpeace, 2004) | Chemicals detected in all participants | Evidence of body burden from consumer products |

| Phthalates [15] | Metabolites in urine, serum, breast milk, other biospecimens | Populations across the globe | Prevalent human exposure through dietary sources, dermal absorption, inhalation | Endocrine disruption, reproductive effects, cancer, metabolic diseases |

| Heavy Metals [15] | Mn, Pb, Cd, As in hair | 222 children aged 6-12 years | All metals detected; differences by gender and hair segment | Neurodevelopmental risks, various toxicities |

| Benzene [15] | S-phenyl-mercapturic acid (SPMA) in urine | Cohort in central Italy | Active smoking major source; nonsmokers also exposed | Hematotoxicity, carcinogenesis |

Molecular Evidence of Chemical-Biological Interactions

At the molecular level, chemical footprints manifest as specific modifications to biological molecules, providing mechanistic evidence of chemical-biological interactions:

Protein Adducts: Hemoglobin and albumin—the most abundant proteins in blood—form covalent adducts with toxicants and endogenous electrophiles [15]. For instance, the N-terminal valine residues of the α-chain of Hb and the cysteine residue (Cys-β93) of the β-chain of Hb react with many electrophiles, including carcinogenic aromatic amines [15]. The highly nucleophilic Cys-34 residue of albumin reacts with epoxides of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, while lysine residues form adducts with aflatoxin B1 dialdehyde [15]. These adducts serve as long-term records of exposure to reactive chemicals.

DNA Adducts: Exposure to environmental chemicals often leads to diverse DNA damage, with the formation of DNA adducts representing one of the key events in chemical-induced carcinogenesis [15]. DNA adducts of different classes of tobacco carcinogens have been identified in human biospecimens, with mass spectrometry methods emerging as the preferred analytical technique due to high selectivity and sensitivity [15].

Gut Microbiome Toxicity: Environmentally induced perturbation in the gut microbiome is strongly associated with human disease risk [15]. Functional gut microbiome alterations that may adversely influence human health represent an increasingly appreciated mechanism by which environmental chemicals exert their toxic effects [15]. The establishment of gut microbiome toxicity links the toxic effects of various environmental agents and microbiota-associated diseases [15].

Green Chemistry and One Health: An Integrated Framework

Green Chemistry Principles as a Preventive Strategy

Green chemistry represents a strategic approach to preventing chemical footprints at their source through the design of chemical products and processes that reduce or eliminate the use and generation of hazardous substances [19]. The Twelve Principles of Green Chemistry, established by Paul Anastas and John C. Warner in 1998, provide a systematic framework for designing safer chemicals and manufacturing processes [1] [19]. These principles include waste prevention, atom economy, less hazardous chemical syntheses, designing safer chemicals, safer solvents and auxiliaries, design for energy efficiency, use of renewable feedstocks, reduce derivatives, catalysis, design for degradation, real-time analysis for pollution prevention, and inherently safer chemistry for accident prevention [19].

The application of green chemistry principles within a One Health framework offers a comprehensive strategy for protecting human, animal, and environmental health from hazardous chemical exposures. This approach is particularly relevant in pharmaceutical development, where the integration of One Health concepts and green chemistry principles into the R&D pipeline can lead to more environmentally friendly antiparasitic drugs for both human and animal health [1]. The concept of sustainability-by-design is becoming a key approach toward a more sustainable and responsible methodology throughout the entire R&D pharmaceutical pipeline, including drug discovery, delivery, manufacturing, packaging, advertising, and marketing [1].

Convergence of Green Chemistry and Occupational Safety

A natural convergence exists between green chemistry/sustainability and occupational safety and health efforts [20] [3]. Addressing both together can have a synergistic effect, while failure to promote this convergence could lead to increasing worker hazards and lack of support for sustainability efforts [20]. The hierarchy of controls—elimination, substitution, engineering controls, administrative controls, and personal protective equipment—aligns closely with green chemistry principles, with both emphasizing prevention and upstream solutions [20].

The pharmaceutical industry provides illustrative examples of this convergence. The synthesis of Pregabalin, a pharmaceutical treatment for nervous disorders, was improved through the identification of new enzymes that eliminated several chemical conversion steps, increased production speed, and reduced waste [20] [3]. These improvements based on green chemistry principles had the added benefit of removing various solvents during the synthesis process, thereby reducing worker exposures [20] [3].

The following diagram illustrates the interconnections between Green Chemistry, Occupational Safety and Health, and the broader One Health approach:

Methodologies for Assessing Chemical Footprints

Advanced Analytical Techniques in Biomarker Research

The detection and quantification of chemical footprints rely on sophisticated analytical methodologies that can identify and measure trace levels of chemicals and their biological interactions:

Mass Spectrometry-Based Technologies: Advanced mass spectrometry techniques represent the cornerstone of modern biomarker research [15]. These technologies enable monitoring of exposures through both targeted and non-targeted methods, allowing for comprehensive assessment of the exposome—the totality of environmental exposures [15]. Mass spectrometry methods have largely supplanted immunochemical and postlabeling techniques for DNA adduct analysis due to superior selectivity and sensitivity [15].

Accelerator Mass Spectrometry (AMS): This exquisitely sensitive technique measures long-lived radionuclides and can be applied to trace biological interactions with chemicals at extremely low concentrations [15]. AMS is particularly valuable for studying the fate and distribution of chemicals in biological systems.

Omics Technologies: Advances in metabolomics, proteomics, and toxicogenomics allow for comprehensive assessment of biological responses to chemical exposures [16]. These approaches facilitate the identification of previously imperceptible biomarkers that can predict how tissues respond to toxic substances [16]. The emergence of cutting-edge technologies, such as microRNAs (miRNAs), holds great promise as reliable and robust biomarkers for early detection of various conditions, including diseases, birth defects, pathological changes, cancer, and toxicity [16].

Experimental Approaches and Research Protocols

Rigorous experimental protocols are essential for generating reliable evidence of chemical footprints:

Adductomics: This approach involves comprehensive screening for covalent adducts formed between environmental chemicals and biological macromolecules [15]. Protein adductomics techniques can screen for harmful exposures to causative agents of chronic disease and identify individuals at risk [15]. For example, the N-(2,3-dihydroxypropyl)valine hemoglobin adduct formed with glycidol has been used to assess internal doses of this genotoxicant in children [15].

Site-Specific Mutagenesis: Chemical incorporation of modifications at specific sites within vectors has been a useful tool to deconvolute what types of damage quantified in biologically relevant systems may lead to toxicity and/or mutagenicity [15]. This approach allows researchers to focus on the most relevant biomarkers that may impact human health [15].

Multiple Biomarker Approach: Systematic use of multiple biomarkers has been found to be most useful in the assessment of pollutants' effects [17]. Employing a multi-biomarker approach provides a wealth of information and enhances accuracy compared to relying solely on a single biomarker [16]. For example, in assessing coral health, several biomarker enzymes involved in melanin synthesis pathway and free radical scavenging enzymes were determined to evaluate stress induced by coral pathogens [17].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies for Chemical Footprint Analysis

| Research Tool Category | Specific Examples | Application in Chemical Footprint Research | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Analytical Instruments | LC-MS/MS [15]; Accelerator Mass Spectrometry [15]; High-Throughput Screening systems [20] | Quantification of biomarkers; Detection of DNA/protein adducts; Rapid toxicity screening | High sensitivity and specificity; Ability to detect trace levels |

| Bioinformatic Tools | Computational toxicology software (e.g., EPA's T.E.S.T. [20]); Chemometric models [16] | Predicting toxicity of materials; Analyzing complex biomarker data | Enables prediction without full animal testing; Identifies patterns in complex data |

| Specialized Assays | Comet assay [17]; Micronucleus test [17]; Telomerase repeat amplification protocol [17]; Metabolomic profiling | Assessing DNA damage; Chromosomal abnormalities; Telomerase activity; Metabolic changes | Detect various types of genetic damage; Comprehensive metabolic assessment |

| Biological Models | In vitro cell cultures; Animal models (e.g., rats, mice [17]); Environmental sentinels (e.g., mussels [17], earthworms [17]) | Mechanistic studies; Toxicity testing; Environmental monitoring | Controlled experimental conditions; Ecological relevance |

The evidence base for chemical footprints reveals an inescapable reality: synthetic chemicals from consumer products, industrial processes, and environmental contamination leave detectable traces in biological systems, with potential implications for health across species. The One Health perspective provides an essential framework for understanding and addressing these interconnected challenges, recognizing that the health of humans, animals, and ecosystems is inextricably linked [1] [7].

Biomarkers of exposure, effect, and susceptibility offer powerful tools for documenting chemical footprints and understanding their health implications [15] [16]. These biomarkers provide objective evidence of chemical-biological interactions at molecular, cellular, and physiological levels, serving as early warning systems for potential health risks [16] [17]. The continuing advancement of analytical technologies, particularly in mass spectrometry and omics approaches, is enhancing our ability to detect these footprints with increasing sensitivity and specificity [15] [16].

Green chemistry principles represent a proactive strategy for preventing chemical footprints at their source, offering a pathway toward chemical products and processes that minimize or eliminate hazards [1] [20] [19]. When integrated with occupational safety and health considerations, green chemistry practices can create synergistic benefits for workers, consumers, and ecosystems [20] [3]. The convergence of these fields within a One Health framework provides a comprehensive approach for addressing the complex challenges posed by chemical footprints in the modern world [1] [7].

As research in this field advances, the development and validation of novel biomarkers will continue to enhance our understanding of chemical footprints and their health implications. The application of this knowledge through green chemistry innovations, informed by a One Health perspective, offers promise for reducing chemical hazards and protecting the health of people, animals, and the ecosystems we share.

The conceptual journey from "One Medicine" to integrated Planetary Health represents a paradigmatic shift in understanding the interconnectedness of human, animal, and environmental health. This evolution mirrors the scientific community's growing recognition that health challenges cannot be confined to disciplinary silos but must be addressed through unifying approaches that acknowledge the complex interactions between species and ecosystems. The historical development of these concepts reflects an expanding scope of concern—from a primary focus on zoonotic diseases to a comprehensive understanding that the health of human civilization is inextricably linked to the stability of Earth's natural systems [21] [22]. This progression has profound implications for research methodologies, particularly in fields like green chemistry assessment, where understanding these interconnections is pivotal for developing sustainable solutions to global health challenges.

The "One Medicine" concept, tracing back to 19th-century physicians like Rudolf Virchow, established the foundational understanding that human and animal medicine should not operate in isolation [22]. Virchow's work on Trichinella spiralis in pork led to significant public health measures and his proclamation that "between animal and human medicine there are no dividing lines—nor should there be." This concept was further advanced by Canadian physician Sir William Osler in the 1870s, who taught both medical students at McGill College and veterinary students at the Montreal Veterinary College, publishing on the relationship between animals and humans while promoting comparative pathology [22]. The formalization of this approach continued through 20th-century figures like James Steele, who founded the Veterinary Public Health division at the CDC in 1947, and Calvin Schwabe, who coined the term "One Medicine" and advocated vigorously for collaboration between human and veterinary public health professionals to address zoonotic diseases [23] [22].

Historical Development and Conceptual Evolution

Key Milestones from One Medicine to Planetary Health

The transition from "One Medicine" to "One Health" and ultimately to "Planetary Health" represents a significant expansion in conceptual scope, reflected in key historical milestones. The following timeline illustrates the pivotal moments in this evolutionary pathway:

The conceptual evolution began with the One Medicine approach, which primarily focused on the connections between human and animal health, especially regarding zoonotic diseases. This perspective was championed by veterinarians in public health roles who recognized the value of collaborative approaches to disease control [22]. The Manhattan Principles established in 2004 marked a crucial expansion, outlining twelve priorities for combating health threats at the interface between humans, domestic animals, and wildlife, and calling for an international, interdisciplinary approach that ultimately formed the basis of the "One Health, One World" concept [23].

The period between 2008 and 2010 witnessed the institutional adoption of One Health approaches by major international organizations. The 2008 International Ministerial Conference on Avian and Pandemic Influenza in Egypt saw the release of "Contributing to One World, One Health - A Strategic Framework for Reducing Risks of Infectious Diseases," which participants endorsed as a new strategy for fighting infectious diseases [23]. This was followed by the 2010 Stone Mountain Meeting, which defined specific actions to advance the One Health agenda, and the Hanoi Declaration, which recommended broad implementation of One Health and was unanimously adopted by 71 countries [23].

A pivotal transformation occurred in 2015 with the Rockefeller Foundation-Lancet Commission's seminal report, which launched Planetary Health as a distinct field focused on "the health of human civilization and the state of the natural systems on which it depends" [24] [25] [26]. This represented a significant expansion beyond the disease-centered approach of One Medicine and the multispecies focus of One Health to encompass the entire Earth system. More recent developments include the 2021 São Paulo Declaration on Planetary Health, a multi-stakeholder call to action, and the 2024 Global Planetary Health Roadmap, which provides a strategic framework to nurture this growing movement [24].

Defining the Conceptual Frameworks

The transition from One Medicine to Planetary Health represents not merely a chronological evolution but a fundamental expansion in conceptual scope, philosophical foundations, and operational focus. The table below compares these integrated approaches to health:

| Aspect | One Medicine | One Health | Planetary Health |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Definition | Unified approach against zoonoses using human and veterinary medicine [22] | Integrated approach aiming to balance and optimize health of people, animals, and ecosystems [27] | Solutions-oriented field addressing impacts of human disruptions to Earth's systems on human health and all life [24] [26] |

| Primary Focus | Zoonotic disease prevention and control through collaboration between human and veterinary medicine [23] [22] | Health at human-animal-ecosystem interfaces; emerging infectious diseases; food safety and security [23] [27] | Health of human civilization and natural systems; anthropogenic environmental changes; equity and social justice [24] [25] |

| Historical Context | 19th century origins (Virchow); term coined by Schwabe in 1960s-1980s [22] | Evolved from One Medicine; formalized through Manhattan Principles (2004) and international adoption (2008-2010) [23] | Concept launched in 2015; builds on environmental movements of 1970s-80s and precursor concepts [24] |

| Key Actors | Physicians, veterinarians, public health professionals [22] | Multisectoral collaboration including human health, animal health, environmental sectors [23] [27] | Transdisciplinary approach including earth scientists, economists, policymakers, communities [24] [26] |

| Operational Level | Professional collaboration between medical disciplines [22] | National and international government agencies; regional organizations [21] | Academic networks; non-governmental organizations; social movements [21] [24] |

| Philosophical Foundation | Comparative medicine; shared disease mechanisms between species [22] | Interdependence of human, animal, and ecosystem health; systems thinking [21] [27] | Anthropocene awareness; interconnection with nature; equity and social justice; systems change [24] |

Methodological Approaches and Experimental Protocols

Research Methodologies Across Integrated Health Approaches

The methodological evolution from One Medicine to Planetary Health reflects the expanding scope of these frameworks, incorporating increasingly sophisticated and transdisciplinary approaches to understanding health in interconnected systems. The following diagram illustrates the progressive integration of methodological approaches across these evolving paradigms:

One Medicine methodologies primarily centered on comparative pathology and epidemiological tracking of diseases across species. This approach relied heavily on laboratory analysis of shared pathogens and surveillance systems that monitored disease incidence in human and animal populations [22]. The primary methodological innovation was the systematic collaboration between human and veterinary laboratories, enabling more effective tracking of zoonotic diseases like bovine tuberculosis, brucellosis, and rabies [23].

One Health methodologies expanded this approach to include environmental monitoring and cross-sectoral collaboration. The Stone Mountain Meeting in 2010 established key methodological priorities, including developing One Health trainings and curricula, establishing global networks, conducting country-level needs assessments, building capacity at the country level, and gathering evidence for proof of concept through literature reviews and prospective studies [23]. Methodologically, One Health emphasizes operationalizing collaboration through joint risk assessments, integrated surveillance systems, and coordinated outbreak response between human health, animal health, and environmental sectors [23] [27].

Planetary Health methodologies incorporate systems thinking and transdisciplinary research approaches that acknowledge the complex interdependencies between human and natural systems. The field employs the framework of planetary boundaries—a set of nine biophysical parameters within which humanity can continue to develop and thrive [24]. As of 2024, six of these boundaries (climate change, biosphere integrity, biogeochemical flows, land-system change, freshwater use, and novel entities) had already been exceeded, highlighting the urgency of Planetary Health approaches [24]. Methodologically, this involves tracking indicators of Earth system stability and human wellbeing, modeling complex cascading impacts, and developing solutions that simultaneously address environmental sustainability and health equity [24] [25].

Experimental Protocols for Green Chemistry Assessment in Planetary Health

Within green chemistry assessment research, experimental protocols have evolved to incorporate the expanding scope of integrated health approaches. The following research framework illustrates the application of these concepts in assessing sustainable chemistry innovations:

The experimental workflow for green chemistry assessment within a Planetary Health framework typically involves four key phases:

Problem Identification and Scoping: This initial phase involves systematic screening of chemical processes and products for their potential impacts on human and ecosystem health. Protocols include environmental impact screening, health hazard assessment of chemical entities, and identification of exposure pathways across species and ecosystems [28] [25].

Green Chemistry Solution Design: Following problem identification, researchers develop alternative chemical processes aligned with green chemistry principles. Key methodological components include sustainable feedstock selection, design of benign synthesis pathways to reduce or eliminate hazardous substances, and application of renewable energy inputs in chemical production [28].

Multi-Scale Assessment: This phase employs integrated assessment protocols to evaluate the broader implications of chemical innovations. Standard methodologies include Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) to quantify environmental impacts across the entire product lifecycle, Planetary Boundaries Evaluation to situate chemical processes within Earth system limits, and cross-species toxicological screening to identify potential impacts on non-human organisms and ecosystem functions [24] [25].

Implementation and Policy Translation: The final phase focuses on translating research findings into practical applications and policy recommendations. This involves stakeholder engagement across multiple sectors, development of evidence-based policy recommendations, and creation of monitoring frameworks to track implementation effectiveness and unintended consequences [28] [24].

Comparative Analysis and Research Data

Quantitative Comparison of Health Approaches

The evolution from One Medicine to Planetary Health represents not only a conceptual expansion but also measurable differences in scope, application, and impact. The table below summarizes key quantitative and qualitative differences between these approaches:

| Parameter | One Medicine | One Health | Planetary Health |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temporal Scope | 19th century to present | 2004 to present | 2015 to present |

| Number of Sectors Actively Engaged | 2 (human medicine, veterinary medicine) | 3+ (human health, animal health, environment, agriculture) | 10+ (all sectors affecting natural systems) [24] |

| Primary Scale of Intervention | Individual, herd, and community health | Population health, ecosystem interfaces | Earth system, global scale [24] |

| Key Performance Indicators | Zoonotic disease incidence; diagnostic accuracy across species | Emerging disease detection time; intersectoral collaboration metrics | Planetary boundaries metrics; health equity indices; ecosystem integrity [24] |

| Implementation Level | Professional practice; laboratory collaboration | International organizations; national governments; regional bodies [21] | Academic networks; NGOs; social movements [21] |

| Typical Funding Sources | Biomedical research grants; public health funding | Multisectoral health budgets; international development funds | Environmental and sustainability funding; philanthropic organizations [24] |

| Governance Structure | Professional associations; public health agencies | Tripartite (FAO, WHO, WOAH) plus UNEP; national One Health committees | Multilateral environmental agreements; transnational networks [24] |

Evidence Base and Validation Studies

The effectiveness of integrated health approaches is supported by a growing body of empirical evidence and case studies demonstrating their value in addressing complex health challenges:

One Medicine Success Cases: Historical applications of One Medicine principles have demonstrated significant public health benefits. Examples include the control of bovine tuberculosis through coordinated human and animal health surveillance, the near-eradication of rabies in many regions through integrated vaccination programs in wildlife and domestic animals, and the management of brucellosis through collaborative monitoring and control efforts between agricultural and public health sectors [23] [22]. These successes established the foundational evidence for the economic and public health benefits of cross-species approaches to disease control.

One Health Validation Studies: The One Health approach has proven particularly valuable in addressing emerging infectious diseases and antimicrobial resistance. The 2012 One Health Summit in Davos, Switzerland, resulted in the "Davos One Health Action Plan," which pinpointed ways to improve public health through multi-sectoral and multi-stakeholder cooperation, with a focus on food safety and security [23]. The effectiveness of this approach was demonstrated during the H1N1 influenza pandemic, where coordinated surveillance in human, swine, and avian populations enabled more effective tracking and response to the emerging threat [23]. The Stone Mountain Meeting in 2010 further contributed to building the evidence base through prospective studies designed to demonstrate proof of concept for the One Health approach [23].

Planetary Health Impact Evidence: Research in Planetary Health has quantified the extensive connections between environmental change and health outcomes. The World Health Organization estimates that 23% of global deaths are linked to environmental factors [25]. The Planetary Health approach has documented how climate change, biodiversity loss, and pollution collectively impact health through multiple pathways, including increased infectious disease transmission, reduced food and water security, rising non-communicable diseases, and mental health impacts [24] [25]. The healthcare sector itself contributes approximately 4.4% of global net emissions—if it were a country, it would be the fifth-largest emitter in the world—highlighting the importance of integrating Planetary Health principles into healthcare delivery and research [25].

Research Tools and Methodological Framework

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Methods and Reagents

Implementing integrated health approaches in green chemistry assessment requires specialized methodological tools and assessment frameworks. The table below details key reagents, models, and methodologies essential for research in this field:

| Tool Category | Specific Tools/Methods | Application in Integrated Health Research | Protocol Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment Frameworks | Planetary Boundaries Framework [24] | Evaluating chemical processes against Earth system limits | Quantitative assessment of 9 key Earth system processes; reference to pre-industrial baselines |

| Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) [25] | Comprehensive environmental impact assessment across product lifecycle | Cradle-to-grave analysis; multiple impact categories (carbon, water, ecotoxicity) | |

| One Health Index (OHI) [27] | Measuring integration and outcomes across human, animal, environmental health | Multidimensional metrics; sectoral balance assessment; implementation effectiveness | |

| Analytical Methods | Green Chemistry Principles [28] | Designing chemical processes with reduced environmental and health impacts | 12 principles of green chemistry; waste prevention; renewable feedstocks; degradation design |

| Cross-Species Toxicological Screening | Identifying differential impacts across biological organisms | In vitro and in vivo models; ecological receptor testing; endocrine disruption assays | |

| Systems Modeling and Network Analysis | Understanding complex interactions and cascading effects in health systems | Computational modeling; network mapping; scenario development; tipping point analysis | |

| Collaborative Mechanisms | Transdisciplinary Research Platforms [24] | Integrating knowledge across scientific disciplines and societal sectors | Co-design processes; stakeholder engagement frameworks; knowledge integration methods |

| Integrated Surveillance Systems [23] | Simultaneous monitoring of health indicators in human, animal, environmental compartments | Data standardization; shared reporting platforms; synchronized sampling protocols | |

| Community-Based Participatory Research [27] | Engaging local and indigenous knowledge in health assessment | Ethical collaboration frameworks; knowledge co-production; equitable partnership models |

Standardized Protocols for Integrated Assessment

Research in integrated health approaches requires standardized protocols to ensure consistency and comparability across studies:

Planetary Health Assessment Protocol: This comprehensive protocol involves quantifying impacts of chemical processes or healthcare practices within the planetary boundaries framework. The methodology includes: (1) Baseline assessment of the nine planetary boundaries (climate change, biosphere integrity, biogeochemical flows, etc.); (2) Impact pathway mapping to trace connections between chemical exposures and health outcomes across species and systems; (3) Equity assessment to evaluate differential impacts across populations and species; and (4) Solution co-design with stakeholders to develop contextually appropriate interventions [24] [25]. Standardized metrics include carbon footprint, water footprint, land system change, and novel entity introduction rates.

One Health Operationalization Protocol: The CDC-led Stone Mountain Meeting established a standardized protocol for implementing One Health approaches, including: (1) Joint risk assessment using integrated teams from human, animal, and environmental health sectors; (2) Coordinated surveillance with standardized data collection and shared reporting platforms; (3) Outbreak investigation with cross-sectoral response teams; and (4) Control measure implementation with synchronized interventions across sectors [23]. Key to this protocol is the development of shared terminology, interoperable data systems, and joint training programs to build capacity for collaboration.

Green Chemistry Transition Protocol: For applying integrated health approaches in chemical assessment and development, a standardized protocol includes: (1) Hazard assessment using green chemistry principles to evaluate feedstocks, reagents, and products; (2) Exposure mapping across human, animal, and environmental compartments; (3) Alternative assessment to identify safer chemical and process options; and (4) Sustainable implementation considering scalability, circular economy principles, and just transition frameworks [28]. This protocol emphasizes pollution prevention at the design stage rather than end-of-pipe control, aligning with the preventive orientation of Planetary Health.

The historical evolution from "One Medicine" to integrated "Planetary Health" represents a fundamental expansion in how the scientific community conceptualizes and addresses health challenges. This trajectory has moved from a focus on shared disease mechanisms between humans and animals to a comprehensive recognition that human health ultimately depends on the stability and resilience of Earth's natural systems [21] [24] [26]. For researchers in green chemistry and drug development, this evolutionary pathway offers both a compelling conceptual framework and practical methodologies for assessing and improving the sustainability of chemical innovations.

The integrated approaches of One Health and Planetary Health are particularly relevant for addressing complex global challenges such as pandemic prevention, climate change impacts, biodiversity loss, and antimicrobial resistance [21] [25]. These approaches provide conceptual frameworks and methodological tools for understanding the interconnections between chemical design, environmental impacts, and health outcomes across species and systems. As the Planetary Health Alliance emphasizes, this field is "solutions-oriented," focusing not only on analyzing human disruptions to Earth's natural systems but also on developing and implementing strategies to address these challenges [26].

For the field of green chemistry assessment, this evolutionary perspective underscores the importance of expanding evaluation frameworks beyond traditional metrics of efficiency and toxicity to include broader impacts on ecosystem integrity, biodiversity, and Earth system processes. The planetary boundaries framework offers particularly valuable guidance for situating chemical innovations within Earth's carrying capacity [24]. Similarly, the emphasis on equity and social justice in Planetary Health aligns with growing recognition that sustainable solutions must address disproportionate environmental exposures and health impacts on vulnerable populations [24] [27].

As research continues to demonstrate the extensive interconnections between environmental change and health outcomes, the integration of these perspectives into chemical design and assessment becomes increasingly essential. The historical context from One Medicine to Planetary Health provides both a compelling narrative of conceptual evolution and a practical toolkit for creating sustainable healthcare solutions that protect both human health and the natural systems on which it depends.

The concept of One Health—which recognizes the inextricable linkages between the health of humans, animals, and ecosystems—is fundamentally reshaping drug development paradigms [1]. In parallel, the pharmaceutical industry faces increasing pressure to reduce its substantial environmental footprint, creating a powerful sustainability imperative that drives innovation [29]. This convergence has accelerated the adoption of green chemistry principles throughout the research and development pipeline, transforming how scientists design, synthesize, and produce therapeutic compounds [1].

Where traditional drug development often prioritized efficacy and speed above environmental concerns, contemporary approaches recognize that environmental responsibility and scientific innovation must advance together [29]. This shift is particularly crucial for addressing vector-borne parasitic diseases, which disproportionately affect vulnerable populations and are intensifying due to climate change, thus exemplifying the interconnected nature of planetary and human health [1]. The industry's response to these challenges is yielding novel methodologies that reduce waste, conserve resources, and create more sustainable workflows from discovery to manufacturing.

Quantitative Assessment of Green Chemistry Principles in Antiparasitic Drug Development

Green Chemistry Principles and Implementation Metrics

The 12 Principles of Green Chemistry provide a systematic framework for evaluating and improving the sustainability of drug development processes [1]. The table below summarizes quantitative metrics and implementation examples for key principles, with particular focus on antiparasitic drug development:

Table 1: Green Chemistry Principles and Implementation in Drug Development

| Principle | Key Metric | Traditional Approach | Sustainable Alternative | Exemplar Compound |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Waste Prevention | E-Factor (kg waste/kg product) [1] | Multi-step synthesis with toxic reagents | One-pot synthesis & catalyst optimization [1] | Tafenoquine [1] |

| Safer Solvents/ Auxiliaries | Solvent Guide Score [1] | Halogenated solvents (DCM, DMF) | Bio-based solvents, water, solvent-less [1] | Various VBPD candidates [1] |

| Energy Efficiency | Process Mass Intensity (PMI) | High-temperature reactions | Microwave synthesis, flow chemistry [1] | Artemisinin derivatives [1] |

| Renewable Feedstocks | % Biobased Carbon Content | Petroleum-derived starting materials | Plant-based intermediates, fermentation [1] | Semi-synthetic artemisinins [1] |

Experimental Protocols for Green Chemistry Assessment

E-Factor Determination Protocol

Purpose: To quantify process waste generation for comparative sustainability assessment [1].

Methodology:

- Document total mass of all materials (reactants, solvents, catalysts) used in synthesis

- Isolate and weigh final product (Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient - API)

- Calculate E-Factor using formula: E-Factor = Total mass of waste / Mass of product

- Classify according to pharmaceutical industry bands: API synthesis (25-100), fine chemicals (5-50), commodity chemicals (<5) [1]

Key Instruments: Analytical balance (±0.0001 g), Life Cycle Inventory databases, Process mass tracking software

Solvent Greenness Assessment Protocol

Purpose: To evaluate and compare environmental, safety, and health impacts of reaction solvents.

Methodology:

- Apply CHEM21 Solvent Selection Guide scoring system (Recommended > Problematic > Hazardous)

- Evaluate multiple parameters: waste, environmental impact, health, safety

- Calculate composite score and rank alternatives

- Prioritize Class 3 (low concern) and bio-based solvents over Class 1 (to be substituted)

Application: Directly informed the replacement of dichloromethane (DCM) with cyclopentyl methyl ether (CPME) in antimalarial lead optimization [1].

Sustainable Workflow Integration in Early Discovery

Green Chemistry Principles in Medicinal Chemistry

The implementation of green chemistry begins in early discovery, where strategic choices have cascading environmental impacts throughout development. The following workflow illustrates how sustainability principles are integrated into modern antiparasitic drug discovery:

Research Reagent Solutions for Sustainable Laboratories

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Sustainable Alternatives

| Reagent Category | Traditional Materials | Sustainable Alternatives | Function | Environmental Impact Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solvent Systems | Acetonitrile, DMF, DCM | Bio-based solvents, water, solvent-less reactions [1] | Compound dissolution & purification | Reduced toxicity, biodegradability |

| Catalysts | Heavy metal catalysts | Biocatalysts, organocatalysts [1] | Reaction acceleration | Renewable, biodegradable, less toxic |

| Assay Materials | Virgin plastic consumables [29] | Recycled plastics, higher plate formats [29] | High-throughput screening | Plastic waste reduction |

| Dispensing Tech | Manual pipetting | Acoustic dispensing [29] | Reagent transfer | 90% solvent volume reduction |

Environmental Impact Analysis: Traditional vs. Sustainable Approaches

Carbon Footprint and Resource Utilization

Drug development activities contribute significantly to carbon emissions through energy-intensive processes and resource consumption [29]. The following comparative analysis quantifies these environmental impacts:

Table 3: Environmental Impact Comparison: Traditional vs. Sustainable Approaches

| Development Phase | Primary Environmental Impact | Traditional Practice | Sustainable Innovation | Quantified Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discovery Chemistry | Solvent waste, energy use [1] | Linear synthesis, toxic solvents | One-pot reactions, green solvents [1] | E-Factor reduction up to 65% [1] |

| Assay Development | Plastic waste [29] | 96-well plates, single-use plastics | 384/1536-well plates, reusables [29] | Plastic waste reduction up to 70% [29] |

| Process Chemistry | Resource intensity [1] | Low atom economy processes | Catalytic methods, renewable feedstocks [1] | PMI improvement 30-50% [1] |

| Travel/Commuting | Carbon emissions [29] | Daily commutes, global conferences | Virtual collaboration, remote work [29] | Emissions reduction potential >50% [29] |

Waste Stream Analysis and Reduction Strategies

Pharmaceutical development generates complex waste streams, with plastic contamination and hazardous solvent disposal presenting particular challenges [29]. Most laboratory plastic waste is contaminated and must be incinerated rather than recycled, creating persistent environmental burdens [29]. The industry is addressing this through:

- Source reduction: Implementing higher density plate formats (384-well, 1536-well) to minimize plastic consumption [29]

- Process redesign: Applying Design of Experiments (DoE) methodologies to optimize assays and eliminate unnecessary steps [29]

- Technology adoption: Utilizing acoustic dispensing technology to dramatically reduce solvent volumes in compound transfer operations [29]

Visualization of Sustainable Drug Development Framework

The complete integration of sustainability principles throughout the drug development lifecycle requires systematic implementation across all stages, as illustrated below:

The pharmaceutical industry's sustainability transformation is accelerating, driven by the integration of One Health principles and green chemistry methodologies [1]. This shift represents more than environmental compliance—it constitutes a fundamental reimagining of drug development that aligns therapeutic innovation with planetary health. The quantitative metrics and experimental protocols presented in this guide provide researchers with practical tools to implement these approaches in their daily work.