Integrating Analytical Quality by Design (AQbD) with Green Chemistry Principles: A Framework for Sustainable and Robust Method Development

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the synergistic integration of Analytical Quality by Design (AQbD) and Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) principles.

Integrating Analytical Quality by Design (AQbD) with Green Chemistry Principles: A Framework for Sustainable and Robust Method Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the synergistic integration of Analytical Quality by Design (AQbD) and Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) principles. It explores the foundational concepts of both frameworks, demonstrating how their merger leads to the development of robust, reproducible, and environmentally sustainable analytical methods. The content covers practical methodological applications using Design of Experiments (DoE), tackles common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and details the validation process with modern greenness assessment tools. Supported by recent case studies from pharmaceutical analysis, this resource offers a strategic pathway to achieving regulatory compliance while aligning with global sustainability goals in biomedical research.

The Confluence of AQbD and Green Chemistry: Building a Foundation for Sustainable Analytical Methods

Analytical Quality by Design (AQbD) represents a systematic, risk-based approach to analytical method development that emphasizes profound scientific understanding and proactive quality control, moving beyond traditional empirical methods. Originating from Quality by Design (QbD) principles introduced by J.M. Juran in the 1970s and adopted by the pharmaceutical industry following USFDA initiatives in 2004, AQbD has revolutionized how analytical procedures are developed, validated, and managed throughout their lifecycle [1]. This paradigm shift addresses critical limitations of conventional one-factor-at-a-time (OFAT) approaches, which often prove time-consuming, resource-intensive, and susceptible to variability and method failure during transfer or routine use [2]. The fundamental philosophy of AQbD is the establishment of a method operable design region (MODR) where method parameters can be adjusted while consistently producing results that meet predefined quality criteria, thereby offering regulatory flexibility and reducing out-of-trend (OOT) and out-of-specification (OOS) results [1] [2].

The integration of AQbD with green analytical chemistry (GAC) principles represents the evolution of sustainable pharmaceutical analysis, aligning with United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, particularly SDG 12: "Responsible Consumption and Production" [3]. This combination ensures that analytical methods are not only robust and reliable but also environmentally sustainable, minimizing hazardous solvent use, energy consumption, and waste generation while maintaining analytical performance [4]. This article comprehensively examines the AQbD framework from Analytical Target Profile (ATP) to MODR, providing experimental protocols, comparative performance data, and visualization of the signaling pathways and workflows that define this transformative approach.

The AQbD Framework: Core Components and Workflow

Systematic Workflow from Concept to Control

The AQbD methodology follows a structured pathway that transforms analytical development from a discrete activity to an integrated lifecycle management approach. This systematic workflow ensures method robustness, reliability, and regulatory compliance while accommodating continuous improvement.

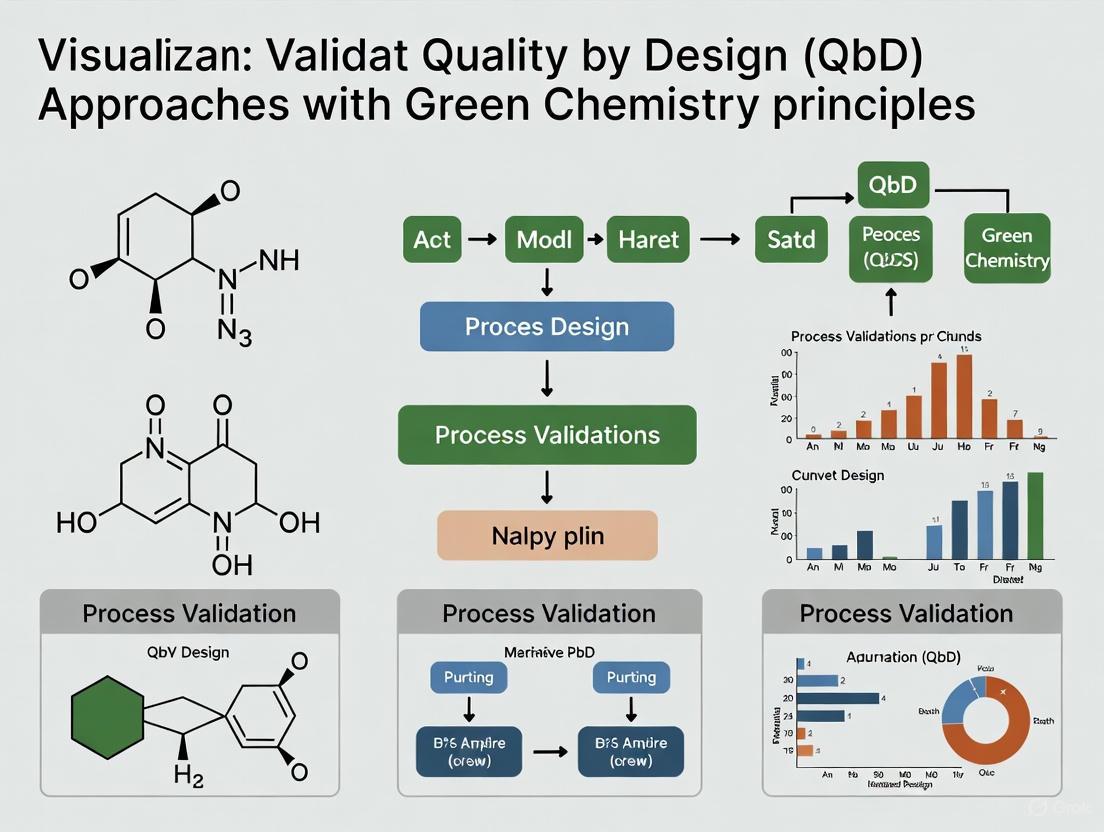

Figure 1: AQbD Workflow from ATP to Lifecycle Management

Core Components of the AQbD Framework

Analytical Target Profile (ATP)

The Analytical Target Profile (ATP) serves as the foundation of the AQbD approach, providing a prospective description of the analytical procedure's required performance characteristics [5] [6]. The ATP defines what the method intends to measure, the required quality of reportable values, and links analytical outcomes to product quality attributes. For a chromatographic method, the ATP typically specifies performance requirements for accuracy, precision, specificity, range, and detection limits, aligning with the decision rule and associated risk of incorrect decisions based on the data [6]. According to recent implementations, the ATP establishes the foundation for the entire method lifecycle, from development through continuous monitoring [5].

Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) and Risk Assessment

Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) represent method parameters and attributes that must be controlled within appropriate limits to ensure desired analytical quality [1]. These typically include physical, chemical, and biological properties critical to method performance. The relationship between potential method parameters and CQAs is systematically evaluated through risk assessment tools, which facilitate identification and ranking of parameters that could impact method performance [1] [5]. Commonly employed risk assessment tools include:

- Ishikawa (fishbone) diagrams for categorizing risk factors into high-risk, noise, and experimental categories [1]

- Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA) using scoring on a scale of 1-10 for risk ranking based on severity, occurrence, and detectability [1]

- Risk Estimation Matrix (REM) employing different risk levels (low, medium, high) based on severity and occurrence [1]

This risk-based approach enables scientists to focus development efforts on parameters with the greatest potential impact on method performance, ensuring efficient resource utilization.

Design of Experiments (DoE) and Method Operable Design Region (MODR)

Design of Experiments (DoE) represents the centerpiece of AQbD implementation, enabling efficient, statistically sound optimization of multiple parameters simultaneously [1] [7]. Through carefully constructed experimental designs, DoE elucidates the relationship between Critical Method Parameters (CMPs) and Critical Method Attributes (CMAs), capturing interaction effects that OFAT approaches inevitably miss [1]. The output of DoE studies is the Method Operable Design Region (MODR), defined as the multidimensional combination and interaction of input variables and process parameters that have been demonstrated to provide assurance of quality [1] [8]. The MODR establishes the boundaries within which method parameters can be adjusted without requiring revalidation, providing significant regulatory flexibility and operational convenience [2] [6].

Comparative Analysis: AQbD vs. Traditional Approach

Fundamental Methodology Differences

The transition from traditional analytical method development to AQbD represents a fundamental shift in philosophy, execution, and regulatory alignment. The comparative analysis below delineates the critical distinctions between these approaches.

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison Between Traditional and AQbD Approaches

| Parameter | Traditional Approach (OFAT) | AQbD Approach | Impact and Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Development Philosophy | Empirical, trial-and-error based [1] | Systematic, proactive, and risk-based [1] | AQbD builds scientific understanding; traditional fixes on first working conditions |

| Parameter Optimization | One-Factor-at-a-Time (OFAT) [2] | Multivariate via Design of Experiments (DoE) [1] | DoE captures interaction effects; OFAT misses critical parameter interactions |

| Robustness | Narrow operating ranges [2] | Broad Method Operable Design Region (MODR) [1] | AQbD methods tolerate normal operational variability; traditional methods prone to failure |

| Regulatory Flexibility | Fixed method parameters [2] | Flexible within MODR [2] [6] | AQbD allows changes without revalidation; traditional requires submission for minor changes |

| Lifecycle Management | Limited continuous improvement [2] | Systematic lifecycle management [6] | AQbD supports continuous verification and improvement; traditional static after validation |

| Quality Assurance | Quality by testing (QbT) [8] | Quality by design [1] | AQbD builds quality in; traditional tests quality in |

| Failure Rates | Higher OOS/OOT results [2] | Reduced OOS/OOT results [1] [2] | AQbD significantly reduces costly investigations and batch failures |

| Resource Investment | Lower initial, higher long-term [2] | Higher initial, lower long-term [6] | AQbD front-loads resources but reduces lifecycle costs through robust performance |

Performance Metrics and Outcomes

Experimental data from multiple studies demonstrate the superior performance of AQbD-developed methods across various analytical applications:

Table 2: Experimental Performance Comparison of AQbD vs. Traditional Methods

| Application Domain | Method Type | Traditional Method Performance | AQbD Method Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meropenem Trihydrate Analysis | HPLC-UV | Poor sensitivity, excessive solvent use, long run times (reported methods) [3] | 99% recovery, 88.7% encapsulation efficiency, reduced environmental impact [3] | Ashwini et al., 2025 [3] |

| Casirivimab and Imdevimab Analysis | UPLC | Not reported | R² > 0.999 linearity, RSD < 2%, validated stability-indicating method [9] | ScienceDirect, 2025 [9] |

| Ensifentrine Analysis | RP-UPLC | No previous methods available | r² = 0.9997 linearity (3.75-22.5 μg/mL), robust under stress conditions [4] | PMC, 2025 [4] |

| Medicinal Plant Analysis | Multi-component assays | Limited robustness for complex matrices | Enhanced robustness for complex chemical profiles, reduced variability [8] | PMC, 2022 [8] |

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Detailed AQbD Implementation Methodology

Defining the Analytical Target Profile (ATP)

The initial step in AQbD implementation requires establishing a comprehensive ATP. The protocol involves:

Define Measurand and Quality Requirements: Clearly identify the analyte(s) and required quality of reportable values, linking to product CQAs [6]. For meropenem trihydrate analysis, the ATP specified accurate quantification in both traditional powders and novel nanosponge formulations [3].

Establish Performance Criteria: Define specific targets for accuracy, precision, specificity, range, and detection limits based on the decision risk and patient impact [6]. For ensifentrine analysis, the ATP required linearity from 3.75-22.5 μg/mL with precise and accurate quantification at the 15 μg/mL target concentration [4].

Consider Business Drivers: Include practical aspects such as analysis time, cost, environmental impact, and transferability [6]. The meropenem method incorporated green chemistry principles as a key ATP requirement [3].

Risk Assessment and Critical Parameter Identification

A systematic risk assessment protocol follows ATP definition:

Method Deconstruction: Break down the analytical method into Analytical Unit Operations with associated inputs and analytical actions [5].

Risk Identification: Employ Ishikawa diagrams to categorize potential risk factors into instrument, method, material, environmental, and analyst-related categories [1].

Risk Analysis and Prioritization: Use FMEA or Risk Estimation Matrix to rank parameters based on severity, occurrence, and detectability [1]. In the ensifentrine UPLC method, initial risk assessment identified column flow rate, temperature, and buffer pH as high-risk factors [4].

DoE Optimization and MODR Establishment

The experimental core of AQbD employs statistical optimization:

Screening Designs: Utilize fractional factorial or Plackett-Burman designs to identify truly critical parameters from the potentially critical ones identified during risk assessment [1] [4].

Response Surface Methodology: Apply Central Composite Design or Box-Behnken designs to model the relationship between CMPs and CMAs [4]. The ensifentrine method employed a central composite design to optimize the three high-risk factors [4].

MODR Establishment: Define the multidimensional region where CMAs meet ATP requirements using contour plots and overlay techniques [1] [8]. The MODR must be verified through experimental confirmation at edge points [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful AQbD implementation requires specific materials and tools designed to facilitate systematic development and optimization.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for AQbD Implementation

| Tool/Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in AQbD | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| DoE Software Platforms | Design-Expert, JMP, MODDE | Statistical experimental design, modeling, and optimization | Enables efficient screening and optimization studies; critical for MODR establishment [4] |

| Risk Assessment Tools | FMEA worksheets, Risk Estimation Matrices | Systematic risk identification and prioritization | Facilitates focus on critical parameters; documented risk assessment supports regulatory submissions [1] [5] |

| Chromatography Columns | HSS C18 SB, Kinetex C18, Chromasol C18 | Stationary phase selection for method development | Different column chemistries evaluated during screening; column temperature often identified as CMP [3] [4] |

| Mobile Phase Components | Ammonium acetate/formate buffers, phosphate buffers, acetonitrile, ethanol, methanol | Creation of optimized elution conditions | Buffer pH and organic modifier concentration frequently identified as CMPs; ethanol increasingly used for green chemistry [3] [9] |

| Green Chemistry Assessment Tools | AGREE, ComplexMoGAPI, Analytical Eco-Scale | Quantitative evaluation of method environmental impact | Supports sustainable method development; aligns with UN SDGs [3] [4] |

Integration with Green Analytical Chemistry Principles

Harmonizing Quality and Sustainability

The integration of AQbD with Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) principles represents the cutting edge of modern analytical science, addressing both methodological robustness and environmental responsibility. This synergy creates a framework where method quality and sustainability are mutually reinforcing rather than competing priorities [3]. Experimental data demonstrates that AQbD-optimized methods frequently exhibit superior environmental profiles compared to conventionally developed methods, achieving reduced solvent consumption, shorter analysis times, and minimized waste generation while maintaining or enhancing analytical performance [3] [9] [4].

The meropenem trihydrate case study exemplifies this integration, where the QbD-driven HPLC method demonstrated impeccable precision and accuracy while simultaneously reducing environmental impact across seven different green analytical chemistry assessment tools [3]. Similarly, the development of a UPLC method for casirivimab and imdevimab employed ethanol as a greener alternative to traditional acetonitrile, with comprehensive greenness assessment confirming reduced environmental impact [9]. These implementations demonstrate that systematic optimization through AQbD naturally aligns with solvent reduction, energy efficiency, and waste minimization - core tenets of GAC.

Greenness Assessment Tools and Metrics

The evaluation of method environmental impact employs multiple assessment tools that provide complementary perspectives on greenness:

- Analytical Eco-Scale: Provides a semi-quantitative assessment based penalty points; excellent methods score above 75 [3]

- AGREE Calculator: Comprehensive assessment using 12 principles of GAC with graphical output [4]

- ComplexMoGAPI: Handles complex methodologies and provides detailed impact analysis [4]

- ChlorTox Scale: Evaluates chlorine content and toxicity of method components [4]

The ensifentrine method development employed these tools comprehensively, demonstrating the method's environmental sustainability while maintaining rigorous performance standards [4]. This multi-metric approach provides a holistic assessment of method greenness, supporting the pharmaceutical industry's transition toward more sustainable practices.

The structured journey from Analytical Target Profile to Method Operable Design Region represents a fundamental transformation in analytical science, replacing empirical approaches with systematic, risk-based methodology. The compelling experimental evidence across diverse applications - from small molecules like meropenem trihydrate to complex biologics like monoclonal antibodies - demonstrates that AQbD delivers superior robustness, reduced failure rates, and enhanced regulatory flexibility compared to traditional approaches [3] [9] [4].

The integration of AQbD with green chemistry principles further positions this approach as essential for contemporary pharmaceutical analysis, addressing both methodological excellence and environmental responsibility [3]. As regulatory guidelines evolve through ICH Q14 and USP 〈1220〉, the AQbD framework provides a scientifically sound foundation for analytical procedures throughout their lifecycle [5] [6]. For researchers and drug development professionals, adopting AQbD principles represents not merely a regulatory expectation but a strategic opportunity to enhance method reliability, reduce investigation costs, and contribute to more sustainable pharmaceutical manufacturing. The experimental protocols and comparative data presented herein provide a roadmap for successful implementation, demonstrating that quality truly can be designed into analytical methods rather than merely tested at the endpoint.

Core Principles of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) for Sustainable Labs

Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) represents a fundamental transformation in analytical science, aligning laboratory practices with the urgent need for environmental stewardship. This discipline integrates sustainability principles directly into analytical methodologies, seeking to minimize the environmental impact of chemical analysis while maintaining high standards of accuracy and precision [10]. The traditional laboratory is a significant resource consumer, often characterized by excessive energy consumption, hazardous waste generation, and reliance on toxic solvents [11]. In fact, research laboratories consume five to ten times more energy than office buildings of equivalent size, and their operations contribute substantially to institutional carbon footprints [11]. GAC addresses these challenges through a systematic reimagining of analytical workflows, offering a framework that balances analytical performance with ecological responsibility. This paradigm shift is particularly relevant for pharmaceutical researchers and drug development professionals who must reconcile rigorous quality control requirements with growing regulatory and societal pressures for sustainable practices. The integration of GAC with Quality by Design (QbD) approaches represents a particularly promising pathway for developing robust, efficient, and environmentally responsible analytical methods that meet the stringent demands of modern pharmaceutical analysis [3] [9].

The 12 Principles of Green Analytical Chemistry

The foundational framework for GAC is built upon 12 principles that provide comprehensive guidelines for designing environmentally benign analytical methods. These principles adapt the broader concepts of green chemistry to the specific context and challenges of analytical chemistry [12] [10]. The principles emphasize waste prevention as the primary goal, rather than waste management after its generation. They advocate for minimal sample size and number of samples, promoting efficiency in experimental design. The principles encourage in situ measurements to avoid sample transport and complex preparation, and highlight the value of integrating analytical processes to save energy and reagents [12].

Further principles champion the selection of automated and miniaturized methods to reduce resource consumption, and recommend avoiding derivatization to streamline analytical procedures. A crucial principle focuses on avoiding large volumes of analytical waste and implementing proper waste management strategies. The framework also promotes multi-analyte determinations to maximize information from single analyses, and prioritizes the use of natural reagents over synthetic alternatives where possible [12]. The final principles address operator safety through enhanced miniaturization and automation, and recommend selecting direct analytical techniques to minimize sample treatment requirements [12]. Together, these principles form a robust foundation for evaluating and improving the environmental profile of analytical methods across diverse applications, including pharmaceutical quality control and drug development.

GAC Implementation Strategies: Methodologies and Tools

Core Green Methodologies

Implementing GAC principles involves adopting specific methodologies and technologies that reduce environmental impact while maintaining analytical performance.

Table 1: Core Green Analytical Chemistry Methodologies

| Methodology | Traditional Approach | Green Alternative | Key Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Size | Milliliters or grams | Microliters or milligrams [13] | Reduces reagent consumption and waste generation |

| Solvent Choice | Hazardous solvents (e.g., chloroform, benzene) | Safer alternatives (e.g., water, ethanol, ionic liquids) [13] [10] | Decreases toxicity, improves operator safety |

| Extraction Techniques | Liquid-liquid extraction with large solvent volumes | Solid-phase microextraction (SPME), supercritical fluid extraction (SFE) [13] [10] | Minimizes or eliminates solvent use |

| Instrumentation | Full-scale benchtop instruments | Miniaturized, portable, or on-site devices [13] | Reduces energy consumption; enables field analysis |

| Energy Consumption | High-energy processes | Room-temperature methods, alternative energy (microwave, ultrasound) [10] | Lowers carbon footprint and operational costs |

Greenness Assessment Tools

Quantitatively evaluating the environmental impact of analytical methods requires specialized assessment tools. These tools provide standardized metrics for comparing method greenness and identifying areas for improvement.

Table 2: Greenness Assessment Tools for Analytical Methods

| Assessment Tool | Methodology | Output | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| AGREE (Analytical GREEnness) | Evaluates 12 criteria based on GAC principles [14] | Score from 0 to 1 (1 = ideal greenness) [14] | Used to assess HPLC methods for pharmaceuticals [15] |

| GAPI (Green Analytical Procedure Index) | Assesses entire method life cycle [14] | Color-coded pictogram with multiple segments | Evaluating sample collection, preparation, and detection [14] |

| NEMI (National Environmental Methods Index) | Categorizes methods based on four criteria [14] | Simple pictogram (green or blank circles) | Preliminary greenness screening [14] |

| Analytical Eco-Scale | Penalty points assigned for hazardous practices [12] | Numerical score (higher = more green) | Comparing overall environmental performance [12] |

QbD-Driven Method Development with GAC Principles

The integration of Quality by Design (QbD) approaches with GAC principles creates a powerful framework for developing analytical methods that are both scientifically robust and environmentally sustainable. QbD emphasizes systematic development, risk assessment, and design space establishment to ensure method quality and reliability [3] [9]. When combined with GAC, this approach inherently builds sustainability into method attributes from the earliest development stages.

A representative example of this integration is demonstrated in the development of an HPLC method for simultaneous determination of five calcium channel blockers [15]. The QbD approach involved identifying Critical Method Parameters (CMPs) and their effects on Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs), then optimizing these parameters to achieve robust performance while minimizing environmental impact. The resulting method used an isocratic mobile phase of acetonitrile-methanol-0.7% triethylamine and achieved separation of all five compounds in just 7.75 minutes, significantly reducing solvent consumption and waste generation compared to traditional methods [15]. The greenness of this QbD-optimized method was comprehensively assessed using multiple tools including AGREE, MoGAPI, and AGSA, confirming its environmental superiority [15].

Similar QbD-GAC integration was successfully applied in developing a UPLC method for simultaneous estimation of casirivimab and imdevimab [9]. The systematic optimization process focused on identifying critical method parameters and their effects on analytical attributes, while consciously selecting ethanol as a greener organic solvent due to its cost-effectiveness and reduced environmental impact [9]. The resulting method demonstrated that environmental considerations could be effectively incorporated without compromising analytical performance, achieving excellent linearity (R² > 0.999) and good reproducibility while minimizing ecological impact [9].

Experimental Protocols and Research Reagent Solutions

Representative Experimental Protocol: QbD-based HPLC Method for Dihydropyridines

Objective: Simultaneous determination of five calcium channel blockers (amlodipine, nifedipine, lercanidipine, nimodipine, nitrendipine) using QbD principles with green chemistry considerations [15].

Materials and Equipment:

- HPLC system with DAD detector

- Luna C8 column (150 × 4.6 mm, 3 μm)

- Methanol, acetonitrile (HPLC grade)

- Triethylamine, phosphoric acid (for pH adjustment)

- Reference standards of all five APIs

Methodology:

- Experimental Design: Taguchi orthogonal array design applied to screen effect of flow rate, column temperature, and organic phase percentage on critical analytical attributes [15].

- Mobile Phase Preparation: Acetonitrile-methanol-0.7% triethylamine (30:35:35% v/v), pH adjusted to 3.06 with ortho-phosphoric acid [15].

- Chromatographic Conditions: Flow rate: 1.0 mL/min; column temperature: 30°C; detection: 237 nm; injection volume: 3 μL; run time: 7.60 minutes [15].

- Sample Preparation: Stock solutions (1000 μg/mL) prepared in methanol, working solutions prepared by appropriate dilution with water to final concentrations of 10-50 μg/mL [15].

- Validation: Linearity, precision, accuracy, and robustness evaluated per ICH guidelines [15].

Results: The method successfully separated all five compounds with retention times of 2.93, 3.98, 4.98, 6.32, and 7.75 minutes respectively. Validation demonstrated linearity (r² ≥ 0.9989), high trueness (99.11-100.09%), and precision (RSD < 1.1%). Greenness assessment using AGREE, MoGAPI, and other tools confirmed superior environmental profile compared to conventional methods [15].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Green Analytical Chemistry

| Reagent/Material | Function | Green Alternative | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethanol | Organic solvent in mobile phase | Renewable, biodegradable solvent [9] | UPLC analysis of monoclonal antibodies [9] |

| Water | Solvent for extraction or mobile phase | Ultimate green solvent [13] [10] | Replacement for organic solvents in chromatography |

| Supercritical CO₂ | Extraction solvent | Non-toxic, recyclable alternative to organic solvents [10] | Supercritical fluid extraction and chromatography |

| Ionic Liquids | Solvents for extraction | Non-volatile, reusable solvents [10] | Sample preparation and separation processes |

| Triethylamine | Silanol suppressor in HPLC mobile phase | Reduces peak tailing for basic compounds [15] | HPLC of dihydropyridines to improve peak shape [15] |

Comparative Analysis: Traditional vs. GAC Methods

Quantitative comparison of analytical methods reveals the significant advantages of GAC-oriented approaches. The environmental and operational benefits extend beyond simple waste reduction to encompass improved efficiency, enhanced safety, and potential cost savings.

Table 4: Quantitative Comparison of Traditional vs. Green Analytical Methods

| Parameter | Traditional HPLC Method | QbD-Optimized Green Method | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Analysis Time | 15-30 minutes typical [3] | 7.6 minutes for 5 analytes [15] | ~50-75% reduction |

| Solvent Consumption | High (multiple mL/min flow rates) | Reduced flow rates (e.g., 0.2 mL/min [9]) | ~60-80% reduction |

| Solvent Toxicity | Often acetonitrile or methanol | Ethanol or water-based [9] | Significant toxicity reduction |

| Waste Generation | 50-500 mL per run [3] | Minimal through miniaturization | ~70-90% reduction |

| Energy Consumption | Standard instrument requirements | Reduced through shorter runs, room temperature operation | ~30-50% reduction |

The method developed for meropenem trihydrate quantification exemplifies these benefits, demonstrating impeccable precision and accuracy with a recovery rate of 99% for marketed products, while simultaneous green assessment using seven different GAC tools indicated significant reduction in environmental impact compared to pre-existing methodologies [3]. Similarly, the development of a green UPLC method for casirivimab and imdevimab analysis achieved dramatically reduced flow rates (0.2 mL/min) while maintaining excellent analytical performance (R² > 0.999, RSD < 2%), demonstrating that environmental and performance objectives can be successfully aligned through systematic method development [9].

The integration of Green Analytical Chemistry principles with Quality by Design approaches represents a paradigm shift in pharmaceutical analysis and drug development. The systematic framework presented demonstrates that environmental sustainability and analytical excellence are not competing priorities but complementary objectives that can be simultaneously achieved through thoughtful method design and optimization. The experimental evidence from multiple case studies confirms that QbD-driven method development naturally accommodates green chemistry principles, resulting in analytical methods with reduced environmental footprint, enhanced safety profiles, and maintained—or even improved—analytical performance. As regulatory expectations evolve and the scientific community embraces its environmental responsibilities, the adoption of GAC principles will increasingly become standard practice in sustainable laboratory operations. For researchers and drug development professionals, this integration offers a pathway to align scientific innovation with ecological stewardship, creating a new generation of analytical methods that serve both scientific rigor and planetary health.

In the modern pharmaceutical laboratory, the pursuit of analytical quality is no longer separate from the responsibility for environmental stewardship. Analytical Quality by Design (AQbD) has emerged as a powerful framework that systematically integrates Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) principles into method development, creating a synergistic relationship that enhances both data quality and environmental performance. This integrated approach represents a significant evolution from traditional univariate method development, which often overlooked environmental impacts in favor of performance metrics alone [16].

AQbD provides a structured, systematic approach to analytical method development that begins with predefined objectives and emphasizes thorough understanding and control of the method throughout its lifecycle. When implemented with sustainability as a core consideration, this framework naturally minimizes environmental impacts by reducing solvent consumption, energy usage, and hazardous waste generation [17]. The resulting methods are not only robust, reliable, and reproducible but also align with the growing regulatory and industry emphasis on sustainable practices [9]. This guide explores the mechanisms through which AQbD systematically achieves green goals, providing comparative data and methodological details to demonstrate this powerful synergy.

Theoretical Framework: The AQbD-GAC Synergy

Core Principles Integration

The synergy between AQbD and GAC stems from their shared emphasis on proactive, systematic approaches rather than reactive corrections. AQbD's foundational elements directly enable the implementation of GAC principles through several key mechanisms:

Systematic Solvent Reduction: By employing Design of Experiments (DoE) and multivariate analysis, AQbD identifies optimal chromatographic conditions that minimize organic solvent consumption without compromising separation efficiency [18] [15]. This directly supports GAC principles advocating for waste reduction and safer solvents.

Holistic Method Assessment: The AQbD framework naturally incorporates the White Analytical Chemistry (WAC) concept, which evaluates methods based on the RGB model: Red (analytical performance), Green (environmental impact), and Blue (practical/economic factors) [19]. This balanced assessment prevents the suboptimization of any single dimension.

Lifecycle Perspective: Both AQbD and GAC emphasize forward-looking approaches. AQbD's focus on method robustness over the entire lifecycle reduces the need for revalidation and repeated experiments, thereby minimizing cumulative resource consumption and waste generation [17].

Visualization: AQbD-GAC Synergy Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the systematic workflow through which AQbD implementation achieves green chemistry goals, integrating analytical quality and sustainability at each phase:

Comparative Experimental Evidence: AQbD-Driven Green Methods

Quantitative Green Metrics Comparison

Multiple pharmaceutical analysis case studies demonstrate how AQbD-optimized methods achieve superior environmental performance compared to traditional approaches while maintaining or enhancing analytical quality.

Table 1: Comparative Green Performance of AQbD-Optimized Methods

| Analytical Method | Drug Compounds | Traditional Solvent Consumption | AQbD-Optimized Solvent Consumption | Green Metric Score | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RP-HPLC | Metronidazole & Nicotinamide | ~5 mL/run (conventional HPLC) | 1.5 mL ethanol/run | AGREE: 0.75 (High) | [18] |

| UPLC | Casirivimab & Imdevimab | High acetonitrile consumption | Ethanol-based, reduced volume | NEMI: 3 green sections | [9] |

| RP-HPLC | Five Dihydropyridines | ~3-5 mL/min (typical methods) | ACN-MeOH-TEA optimized mix | AGREE/ComplexGAPI: High scores | [15] |

| HPLC | Bupropion & Dextromethorphan | Multiple trial runs (>50mL waste) | Minimized experiments via DoE | Not specified | [20] |

The RGB Model: Balanced Method Assessment

The WAC RGB model provides a quantitative framework for evaluating the balanced performance of AQbD-optimized methods, assessing three equally important dimensions:

Table 2: White Analytical Chemistry (WAC) RGB Assessment Model

| Dimension | Assessment Criteria | AQbD Contribution | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Red (Analytical Performance) | Accuracy, precision, sensitivity, selectivity | DoE-optimized parameters ensure reliability | High-quality data with reduced reanalysis needs |

| Green (Environmental Impact) | Solvent toxicity, waste generation, energy consumption | Systematic reduction of hazardous solvents | Lower ecological footprint, safer workplace |

| Blue (Practical & Economic) | Cost, time, simplicity, regulatory compliance | Robust methods reduce lifecycle costs | Faster analysis, reduced operational expenses |

Studies applying this model to AQbD-developed methods, such as stability-indicating HPTLC for thiocolchicoside and aceclofenac, demonstrate achieving an excellent white WAC score, balancing all three dimensions effectively [19].

Experimental Protocols: Implementing AQbD for Green Outcomes

Systematic Method Development Workflow

The following detailed protocol outlines the key stages for developing analytical methods using AQbD principles with integrated green chemistry objectives:

Stage 1: Analytical Target Profile (ATP) Definition with Green Criteria

- Define Method Purpose: Specify the analytical method's scope, target analytes, and required performance characteristics [21].

- Incorporate Green Objectives: Explicitly include sustainability metrics in the ATP, such as maximizing safety, minimizing waste, and reducing energy consumption [16].

- Identify Critical Method Attributes (CMAs): Define both quality attributes (resolution, sensitivity, precision) and environmental attributes (solvent volume, toxicity, waste) as CMAs [20].

Stage 2: Risk Assessment and Critical Parameter Identification

- Employ Risk Assessment Tools: Use Ishikawa (fishbone) diagrams and Failure Mode Effects Analysis (FMEA) to identify factors affecting both analytical and environmental CMAs [17].

- Identify Critical Method Parameters (CMPs): Determine which factors (column temperature, mobile phase composition, flow rate, pH) significantly impact CMAs [20] [15].

- Prioritize Green Parameters: Flag parameters with significant environmental impact (organic solvent percentage, solvent type, analysis time) for special attention during optimization.

Stage 3: Design of Experiments (DoE) and Optimization

- Select Appropriate DoE: For initial screening, employ fractional factorial or Plackett-Burman designs to efficiently identify significant factors with minimal experimental runs [18] [20].

- Response Surface Methodology: Use Central Composite Design or Box-Behnken designs to model the relationship between CMPs and CMAs, enabling identification of optimal conditions [15].

- Multi-criteria Decision Analysis: Apply desirability functions to simultaneously optimize both analytical performance and green metrics, identifying the Method Operable Design Region (MODR) where all criteria are satisfied [18].

Stage 4: Greenness and Whiteness Assessment

- Apply Multiple Metrics: Evaluate the optimized method using comprehensive green assessment tools (AGREE, GAPI, NEMI, Analytical Eco-Scale) [19] [18].

- White Analytical Chemistry Assessment: Apply the RGB model to ensure balanced performance across analytical, environmental, and practical dimensions [19].

- Comparative Analysis: Benchmark against existing methods to quantify environmental improvements, including calculated reductions in carbon footprint, waste generation, and operator hazard [18].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of AQbD for green outcomes requires specific reagents, materials, and tools selected for both analytical performance and environmental attributes.

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for AQbD-Green Method Development

| Category | Specific Materials | Function in AQbD-Green Implementation | Environmental Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Green Solvents | Ethanol, water, methanol, acetone | Mobile phase components optimized via DoE | Lower toxicity, biodegradability, reduced hazardous waste |

| Chromatographic Columns | C8, C18, phenyl-modified silica columns (e.g., Luna, Zorbax) | Stationary phases selected for compatibility with green mobile phases | Enables use of aqueous/ethanol mobile phases instead of acetonitrile |

| DoE Software | Minitab, Design-Expert, statistical packages | Enables efficient experimental design and multi-response optimization | Reduces experimental runs by up to 70%, significantly cutting solvent waste |

| Green Assessment Tools | AGREE, GAPI, NEMI, ComplexGAPI calculators | Quantifies environmental performance of developed methods | Provides objective metrics for sustainability claims and comparisons |

| Buffer Components | Phosphate buffers, triethylamine, ammonium acetate | Modifiers for enhancing separation with green solvents | Replaces more toxic alternatives like ion-pairing reagents |

The RGB Model: Visualizing Balanced Method Performance

The WAC RGB model provides a comprehensive framework for evaluating analytical methods across three equally important dimensions. The following diagram illustrates how AQbD systematically balances these dimensions to achieve methods that excel in analytical performance, environmental sustainability, and practical utility:

The relationship between AQbD and green chemistry is fundamentally synergistic, not merely complementary. The systematic, proactive framework of AQbD provides the necessary structure to methodically incorporate and optimize environmental metrics alongside traditional analytical performance criteria. As demonstrated by multiple pharmaceutical case studies, this integrated approach consistently yields methods that consume fewer resources, generate less waste, and reduce operator hazards while maintaining or enhancing analytical performance [18] [15].

The implementation of AQbD with intentional green objectives represents a paradigm shift in analytical method development, moving beyond retrospective greenness evaluation to proactive environmental design. As regulatory expectations evolve and sustainability becomes increasingly important across the pharmaceutical industry, this AQbD-GAC synergy offers a proven framework for developing methods that excel across all dimensions of the White Analytical Chemistry model - delivering uncompromised analytical quality with significantly reduced environmental impact [19].

The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) guidelines Q8, Q9, Q10, and Q14 provide a comprehensive framework for pharmaceutical development and quality management. Together, they establish a systematic, science-based, and risk-managed approach to drug development and manufacturing, collectively known as Pharmaceutical Quality by Design (QbD) [22]. This framework aligns powerfully with the principles of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC), creating a synergistic relationship that advances both product quality and environmental sustainability in pharmaceutical research and development [16].

The integration of these guidelines enables a paradigm shift from traditional, empirical methods toward more efficient, robust, and environmentally responsible practices. This article examines how these regulatory drivers foster sustainable development through detailed case studies and experimental data, providing drug development professionals with validated approaches for implementing QbD principles with green chemistry.

Core Regulatory Guidelines and Their Sustainable Alignment

ICH Q8 (Pharmaceutical Development) and Sustainability

ICH Q8(R2) focuses on Pharmaceutical Development using a Quality by Design (QbD) approach [23]. It emphasizes building quality into pharmaceutical products through scientific understanding and proactive design rather than relying solely on end-product testing [24]. The guideline introduces key concepts including:

- Quality Target Product Profile (QTPP): "A prospective summary of the quality characteristics of a drug product that ideally will be achieved to ensure the desired quality, taking into account safety and efficacy" [23] [24]. The QTPP forms the foundation for development, outlining target attributes.

- Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs): "A physical, chemical, biological, or microbiological property or characteristic that should be within an appropriate limit, range, or distribution to ensure the desired product quality" [23] [24].

- Critical Process Parameters (CPPs): Process variables that directly impact CQAs and must be controlled to ensure consistent quality [24].

- Design Space: "The multidimensional combination and interaction of input variables and process parameters that have been demonstrated to provide assurance of quality" [24]. Operating within the design space is not considered a regulatory change, providing flexibility.

The QbD approach fundamentally aligns with sustainability by minimizing experimental waste, reducing failed batches, and optimizing resource utilization. Evidence indicates QbD can achieve ~40% fewer failed batches and significant reductions in material waste [24].

ICH Q9 (Quality Risk Management) and ICH Q10 (Pharmaceutical Quality System)

ICH Q9 establishes Quality Risk Management (QRM) principles, providing a framework for proactive risk assessment throughout the product lifecycle [22]. It emphasizes that "the level of effort, documentation, and formality of any process should be proportionate to the level of risk" [22]. ICH Q10 describes a Pharmaceutical Quality System (PQS) that integrates quality planning, monitoring, and continuous improvement [22]. Key components include:

- Process performance and product quality monitoring

- Corrective and preventive action (CAPA) systems

- Change management

- Management review [22]

These guidelines support sustainability by enabling efficient resource allocation toward critical factors, reducing unnecessary controls and testing, and fostering continuous improvement that identifies opportunities for waste reduction and process optimization.

ICH Q14 (Analytical Procedure Development)

ICH Q14 extends QbD principles to analytical method development, providing guidance for robust, reproducible analytical procedures [3]. It encourages a systematic approach to understanding method parameters and their impact on performance, facilitating more reliable methods with reduced failure rates and reagent waste.

Synergistic Framework for Sustainability

The interconnected nature of these guidelines creates a powerful framework for sustainable pharmaceutical development:

Experimental Case Studies: Validating QbD-GAC Integration

Case Study 1: QbD-Driven Green HPLC Method for Meropenem Trihydrate

A recent study developed a QbD-driven HPLC method for quantifying meropenem trihydrate (MPN) in nanosponges and marketed formulations, incorporating comprehensive green analytical chemistry assessment [3].

Experimental Protocol and Methodology

Materials and Instrumentation: MPN standard (≥98% purity), ammonium acetate, acetic acid, acetonitrile (HPLC-grade). HPLC system (Shimadzu LC-2010C HT) with UV detector, auto-sampler, and Kinetex C18 column (250 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 μm) [3].

QbD Implementation Approach:

- Define Analytical Target Profile (ATP): Accuracy, precision, specificity for MPN quantification

- Risk Assessment: Identification of Critical Method Parameters (CMPs) including mobile phase composition, pH, flow rate, column temperature

- Screening Studies: Plackett-Burman design to identify significant factors

- Optimization: Response Surface Methodology (RSM) to establish Method Operable Design Region (MODR)

- Control Strategy: Verification and ongoing monitoring [3]

Chromatographic Conditions:

- Mobile Phase: Ammonium acetate buffer (pH 4.0): acetonitrile (85:15 v/v)

- Flow Rate: 1.0 mL/min

- Detection: UV at 298 nm

- Column Temperature: 25°C

- Injection Volume: 20 μL [3]

Green Assessment Methodology

The method's environmental impact was evaluated using seven green analytical chemistry tools:

- Analytical Eco-Scale

- Analytical GREEnness (AGREE)

- Green Analytical Procedure Index (GAPI)

- National Environmental Methods Index (NEMI)

- Complementary green assessment metrics [3]

Table 1: Performance Data for QbD-based Meropenem HPLC Method

| Parameter | Result | Acceptance Criteria | Sustainability Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recovery (Marketed Product) | 99% | 98-102% | Reduced repeat testing |

| Encapsulation Efficiency (Nanosponges) | 88.7% | N/A | Improved formulation efficiency |

| Precision (%RSD) | <2% | ≤2% | Reduced method variability |

| Environmental Impact Score | Significant reduction vs. conventional methods | - | Lower ecological footprint |

| Solvent Consumption | Reduced vs. literature methods | - | Less hazardous waste |

The study demonstrated that the QbD approach achieved exceptional analytical performance while significantly reducing environmental impact compared to conventional methods. The method successfully applied to both traditional formulations and novel nanosponges, highlighting its robustness and adaptability [3].

Case Study 2: Green HPLC Method for Thalassemia Drugs Using AQbD

Another study implemented an Analytical Quality by Design (AQbD) approach with GAC principles to develop an HPLC method for simultaneous determination of deferasirox (DFX) and deferiprone (DFP) in biological fluids [25].

Experimental Protocol

QbD Implementation:

- Risk Assessment and Scouting Analysis: Preliminary evaluation of chromatographic parameters

- Screening Design: Plackett-Burman design for five chromatographic parameters

- Optimization: Custom experimental design (two levels-three factors) to achieve optimal resolution, peak symmetry, and short run time

- Desirability Function: Used to define optimal chromatographic conditions [25]

Final Chromatographic Conditions:

- Column: XBridge RP-C18 (4.6 × 250 mm, 5 μm)

- Mobile Phase: Ethanol: acidic water pH 3.0 (70:30 v/v)

- Flow Rate: 1 mL/min

- Detection: UV at 225 nm

- Temperature: 25°C [25]

Green Profile Assessment: The method's greenness was evaluated using eight assessment tools: NEMI, modified NEMI, Analytical Method Volume Intensity (AMVI), Analytical Eco-Scale, Analytical Method Greenness Score (AMGS), HPLC-EAT, GAPI, and AGREE [25].

Table 2: Green Assessment Results for Thalassemia Drug HPLC Method

| Assessment Tool | Score/Rating | Improvement vs. Conventional Methods |

|---|---|---|

| NEMI | 3/4 green fields | Significant improvement |

| Analytical Eco-Scale | Excellent rating | Improved environmental friendliness |

| AGREE | High score | Enhanced greenness profile |

| Solvent Toxicity | Reduced | Ethanol vs. acetonitrile |

| Waste Generation | Minimized | Optimized method conditions |

| Energy Consumption | Reduced | Shorter run times |

The method demonstrated linearity over 0.30–20.00 μg/mL for DFX and 0.20–20.00 μg/mL for DFP, with successful application to pharmacokinetic studies in rat plasma. The integration of AQbD and GAC principles resulted in a method that was robust, precise, accurate, and environmentally friendly [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for QbD-GAC Integrated Studies

| Reagent/Solution | Function in QbD-GAC Protocols | Sustainability Advantage |

|---|---|---|

| Ethanol | Green alternative to acetonitrile in mobile phases | Less toxic, biodegradable, renewable source [25] |

| Ammonium Acetate Buffer | Mobile phase modifier for pH control | Reduced environmental impact vs. phosphate buffers [3] |

| Acidic Water (pH adjusted) | Mobile phase component | Replaces organic solvents, reducing toxicity [25] |

| β-Cyclodextrin | Nanosponge formulation component | Enables novel drug delivery, improving therapeutic efficiency [3] |

| HPLC Columns (C18, 5μm) | Stationary phase for separation | Modern columns provide better efficiency, reducing run times and solvent use [3] [25] |

| Design of Experiments Software | Statistical optimization of method parameters | Reduces experimental waste, minimizes trial runs [3] [25] |

| Green Assessment Tools | Quantify method environmental impact | Enable objective comparison and improvement of green metrics [3] [25] |

Analytical Workflow: Integrating QbD and Green Chemistry Principles

The experimental protocols from the case studies demonstrate a systematic workflow for integrating QbD and sustainability principles:

Discussion and Future Perspectives

The case studies demonstrate that the integration of ICH Q8, Q9, Q10, and Q14 principles with green chemistry provides a robust framework for sustainable pharmaceutical development. The QbD approach systematically builds in quality while simultaneously reducing environmental impact through:

- Reduced Experimental Waste: Statistical DoE approaches minimize the number of experimental trials required for method development [3] [25].

- Optimized Resource Utilization: Identification of critical parameters enables right-sizing of controls and elimination of unnecessary testing [26].

- Improved Method Robustness: QbD-developed methods demonstrate greater resilience to variation, reducing failure rates and associated waste [3].

- Sustainable Solvent Selection: Systematic method development facilitates substitution of hazardous solvents with greener alternatives [25] [16].

Regulatory flexibility associated with well-understood design spaces creates opportunities for continuous environmental improvement without additional submissions [26] [24]. This aligns with the ICH Q10 emphasis on continual improvement, enabling ongoing optimization of sustainability metrics throughout the product lifecycle.

Future directions include broader adoption of analytical QbD under ICH Q14, increased implementation of green chemistry metrics in regulatory submissions, and development of standardized sustainability assessment frameworks for pharmaceutical processes. As the industry advances, the integration of these regulatory and sustainability principles will be essential for meeting both quality requirements and environmental goals.

The ICH guidelines Q8, Q9, Q10, and Q14 provide a complementary framework that naturally aligns with and advances sustainability objectives in pharmaceutical development. Through systematic implementation of QbD principles, risk management, quality systems, and analytical quality, pharmaceutical scientists can develop methods and processes that simultaneously achieve regulatory compliance, product quality, and environmental responsibility.

The experimental case studies presented demonstrate that this integration is not only theoretically sound but practically achievable, with documented improvements in both performance metrics and environmental impact. As the pharmaceutical industry continues to evolve, this synergistic approach represents the future of sustainable drug development—where quality and environmental stewardship are jointly optimized throughout the product lifecycle.

The integration of Green Chemistry principles into analytical practices has become imperative for reducing the environmental impact of pharmaceutical development and quality control. Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) aims to minimize the consumption of hazardous reagents and solvents, reduce energy requirements, and decrease waste generation throughout analytical procedures [27] [28]. Within the framework of Quality by Design (QbD), which emphasizes building quality into methods through systematic development rather than relying solely on final testing, the assessment of environmental sustainability has gained significant importance [29] [16]. The pharmaceutical industry faces increasing pressure to align with the United Nations' Sustainability Development Goals, particularly responsible consumption and production [3]. This review provides a comprehensive comparison of three pivotal green assessment tools—AGREE, GAPI, and Eco-Scale—that enable researchers to quantify, evaluate, and improve the environmental footprint of their analytical methods while maintaining rigorous quality standards.

Foundational Principles of Green Assessment Tools

The SIGNIFICANCE Mnemonic and Green Analytical Chemistry

Green Analytical Chemistry is guided by 12 fundamental principles that can be summarized using the SIGNIFICANCE mnemonic, covering aspects from direct analytical techniques and minimal sample size to operator safety and waste minimization [30] [28]. These principles provide a comprehensive framework for evaluating the environmental impact of analytical methods, extending beyond simple reagent toxicity to include energy consumption, sample throughput, and waste treatment [30]. Effective green metrics transform these qualitative principles into quantifiable assessment systems that enable objective comparison between different analytical approaches and identification of opportunities for improvement [30] [28].

Evolution of Green Metrics

The development of green assessment tools has progressed from simple binary evaluations to sophisticated multi-criteria systems. Early tools like the National Environmental Methods Index (NEMI) provided basic pictograms but offered limited granularity [31] [28]. Subsequent metrics introduced semi-quantitative approaches (Analytical Eco-Scale) and more detailed visual representations (GAPI) [31] [32] [28]. The most recent advancements, including AGREE and ComplexGAPI, offer comprehensive evaluations aligned with all 12 GAC principles and cover the entire analytical lifecycle [30] [33] [28]. This evolution reflects the growing recognition that effective green assessment requires balancing comprehensive coverage with practical usability.

Comprehensive Tool Analysis

AGREE (Analytical GREEnness Metric)

Fundamental Principles and Calculation Methodology

The AGREE metric represents a significant advancement in green assessment by comprehensively addressing all 12 principles of Green Analytical Chemistry [30]. This tool employs a clock-shaped pictogram with twelve segments, each corresponding to one GAC principle. The calculator transforms each principle into a score on a 0-1 scale, with the overall result being the product of these individual scores [30]. A key innovation of AGREE is its weighting flexibility, allowing users to assign different importance levels to each criterion based on their specific analytical context and priorities [30]. The output provides immediate visual interpretation through a color-coded diagram where dark green indicates superior greenness and red highlights environmental concerns [30].

Application Workflow

The AGREE assessment process follows a systematic approach: First, users gather data on all aspects of their analytical method, including sample preparation, reagent consumption, energy requirements, waste generation, and safety considerations [30]. Next, they input this information into the freely available AGREE software, adjusting weighting factors according to their specific priorities [30]. The tool then generates a comprehensive pictogram that visually represents the method's performance across all twelve GAC principles [30]. Finally, researchers interpret the results by identifying red or yellow segments that indicate areas for improvement and comparing overall scores between different methodological approaches [30].

GAPI (Green Analytical Procedure Index)

Fundamental Principles and Calculation Methodology

The Green Analytical Procedure Index (GAPI) offers a detailed visual assessment of the environmental impact across all stages of an analytical method [31]. This tool employs a five-pentagram symbol that evaluates the entire analytical procedure from sample collection through final determination [31]. Each pentagram section is color-coded using a traffic light system (green, yellow, red) to represent low, medium, or high environmental impact [31]. GAPI's particular strength lies in its ability to identify the "weakest points" in analytical procedures, providing clear direction for methodological improvements [31]. The recently introduced ComplexGAPI expands this evaluation to include processes preceding the analytical procedure itself, such as the synthesis of materials or reagents used in the analysis [33].

Application Workflow

Implementing GAPI requires a systematic evaluation of each step in the analytical process. The assessment begins with sample collection and preservation, evaluating the environmental impact of these initial stages [31]. The tool then progresses through sample preparation and transportation, examining solvent use, energy consumption, and potential hazards [31]. The core analytical technique itself is assessed for reagent consumption, energy requirements, and miniaturization potential [31]. Additional evaluation covers quantification aspects and final waste treatment considerations [31]. For each category, the appropriate color is assigned based on specific criteria, building the complete five-pentagram pictogram that provides an at-a-glance comparison of different methods [31].

Analytical Eco-Scale

Fundamental Principles and Calculation Methodology

The Analytical Eco-Scale provides a semi-quantitative approach to greenness assessment based on assigning penalty points to various aspects that decrease environmental friendliness [32] [28]. This tool begins with a base score of 100 points representing an "ideal green analysis" and subtracts penalties for hazardous reagents, energy consumption, waste generation, and other negative factors [32] [28]. The final score provides a straightforward numerical evaluation where higher scores indicate greener methods: >75 represents excellent greenness, 75-50 indicates acceptable greenness, and <50 signifies insufficient greenness [32]. This approach is particularly valuable for its simplicity and clear identification of the primary contributors to environmental impact [32] [28].

Application Workflow

The Eco-Scale assessment follows a structured penalty system across several categories. First, evaluators assess reagent penalties, assigning points based on reagent quantity and hazard profile, with more hazardous substances receiving higher penalties [32]. Next, they calculate energy consumption penalties, with points assigned according to the energy requirements of the analytical instrumentation [32]. The evaluation then addresses occupational hazards and waste generation, with penalties proportional to the amount of waste produced [32]. Finally, all penalty points are summed and subtracted from 100 to generate the final Eco-Scale score, which can be directly compared against established greenness thresholds [32].

Comparative Analysis of Assessment Tools

Technical Specifications and Methodological Approaches

Table 1: Technical Specifications of Green Assessment Tools

| Feature | AGREE | GAPI | Analytical Eco-Scale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment Basis | 12 GAC principles (SIGNIFICANCE) | 5-stage analytical procedure | Penalty points from ideal green analysis |

| Output Format | Clock-shaped diagram (0-1 score) | Five pentagrams with color coding | Numerical score (0-100) |

| Scoring System | Continuous (0-1) | Three-color category system | Semi-quantitative (penalty points) |

| Weighting Flexibility | Yes, user-defined weights | Fixed criteria weights | Fixed penalty values |

| Coverage Scope | Comprehensive GAC principles | Entire analytical procedure | Reagents, energy, waste, hazards |

| Software Availability | Freely available calculator | Manual assessment or specialized software | Manual calculation |

| Primary Strength | Comprehensive principle coverage | Detailed process stage evaluation | Simple numerical output |

Performance in Pharmaceutical Analysis Context

Table 2: Performance Characteristics for Pharmaceutical Applications

| Characteristic | AGREE | GAPI | Analytical Eco-Scale |

|---|---|---|---|

| HPLC Method Assessment | Excellent | Very Good | Good |

| Sample Preparation Evaluation | Comprehensive | Detailed | Basic |

| Operator Safety Consideration | Included | Included | Included |

| Waste Treatment Assessment | Included | Included | Included |

| Method Comparison Capability | Excellent | Very Good | Good |

| Ease of Implementation | Moderate | Moderate | Easy |

| Regulatory Alignment | Emerging | Established | Established |

Each tool offers distinct advantages depending on the specific application requirements. AGREE provides the most comprehensive evaluation against all 12 GAC principles, making it ideal for thorough environmental impact assessments and methodological optimization [30] [28]. GAPI excels in visualizing the distribution of environmental impact across different stages of an analytical procedure, particularly valuable for identifying specific areas for improvement [31] [28]. The Analytical Eco-Scale offers straightforward implementation and clear numerical scoring, well-suited for rapid assessments and comparative screenings [32] [28].

Complementary Tool Applications in QbD Framework

Within Quality by Design frameworks, these assessment tools serve complementary roles during different stages of method development. During initial method scouting, the Analytical Eco-Scale provides rapid feedback on the relative greenness of different analytical approaches [32] [3]. As methods progress to optimization phases, GAPI helps identify which specific steps contribute most significantly to environmental impact, directing refinement efforts [31] [3]. For final method validation and control strategy implementation, AGREE offers comprehensive documentation of alignment with green chemistry principles, supporting regulatory submissions and sustainability reporting [30] [3].

Practical Implementation in Pharmaceutical Analysis

Case Study: HPLC Method for Meropenem Trihydrate

A recent implementation of green assessment tools demonstrated their practical value in developing an HPLC method for meropenem trihydrate quantification in pharmaceutical formulations [3]. Researchers applied a QbD approach to method development while systematically evaluating greenness using multiple metrics [3]. The study employed seven different green assessment tools, including AGREE, GAPI, and Analytical Eco-Scale, to comprehensively document the environmental advantages of the newly developed method compared to existing approaches [3]. This multi-tool assessment provided robust evidence of reduced environmental impact through decreased solvent consumption and waste generation while maintaining analytical performance [3].

Industry Application at AstraZeneca

The pharmaceutical industry has begun systematically implementing green metrics to drive sustainability improvements. AstraZeneca has incorporated the Analytical Method Greenness Score (AMGS), a specialized metric for chromatographic methods, to evaluate and improve the environmental profile of their analytical procedures [27]. This implementation has identified significant opportunities for reducing the environmental impact of chromatographic methods across their portfolio, particularly through solvent selection and energy consumption optimization [27]. When scaled across global manufacturing networks, these improvements substantially reduce the environmental footprint of pharmaceutical quality control operations [27].

Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Green Analytical Chemistry

| Reagent/Material | Function in Analytical Chemistry | Green Alternatives |

|---|---|---|

| Acetonitrile | Common HPLC mobile phase solvent | Methanol, ethanol, or water-based mobile phases |

| n-Hexane | Extraction solvent for non-polar compounds | Cyclopentyl methyl ether, ethyl acetate |

| Chloroform | Extraction and dissolution | Dichloromethane (less toxic), or terpenes |

| Phosphate Buffers | Mobile phase modifiers | Ammonium acetate or ammonium formate |

| Derivatization Reagents | Analyte modification for detection | Miniaturization to reduce quantities |

| Traditional C18 Columns | Chromatographic separation | Fused-core or monolithic columns for reduced solvent consumption |

Implementation Guidelines and Best Practices

Strategic Tool Selection

Choosing the appropriate green assessment tool depends on several factors, including the specific analytical technique, development stage, and intended application. For comprehensive environmental profiling, particularly during method development or optimization, AGREE provides the most thorough evaluation against established GAC principles [30] [28]. When identifying specific improvement opportunities within existing methods, GAPI's staged assessment effectively pinpoints areas of highest environmental impact [31] [28]. For rapid screening and comparative analysis of multiple methods, the Analytical Eco-Scale offers straightforward implementation and clear numerical scoring [32] [28]. In many cases, a sequential approach utilizing multiple tools provides the most complete understanding of a method's environmental profile.

Integration with Quality by Design

The effective integration of green assessment tools with QbD principles requires strategic planning throughout the method lifecycle. During initial Analytical Target Profile (ATP) definition, environmental considerations should be explicitly included alongside performance requirements [29] [16]. Risk assessment phases should incorporate green metrics to identify parameters with significant environmental impact [29] [3]. Design of Experiments (DoE) for method optimization should include greenness scores as response variables to balance analytical performance with environmental sustainability [29] [3]. Finally, control strategy implementation should monitor key greenness parameters to ensure maintained environmental performance throughout the method lifecycle [29] [16].

Regulatory and Compliance Considerations

The regulatory landscape for green chemistry in pharmaceutical analysis continues to evolve. While current guidelines primarily focus on analytical performance, regulatory agencies increasingly recognize the importance of environmental sustainability [27] [3]. Documenting greenness assessments using established tools like AGREE, GAPI, and Analytical Eco-Scale can support regulatory submissions by demonstrating commitment to sustainable practices [30] [3]. As the field advances, the incorporation of green assessment data may become expected or required for method validation packages, particularly when multiple equivalent analytical approaches exist [27] [3].

The systematic assessment of greenness using tools like AGREE, GAPI, and Analytical Eco-Scale has become an essential component of modern analytical chemistry, particularly within Quality by Design frameworks. Each tool offers distinct advantages: AGREE provides comprehensive evaluation against all 12 GAC principles, GAPI enables detailed assessment across analytical procedure stages, and Analytical Eco-Scale offers straightforward semi-quantitative scoring. The pharmaceutical industry's increasing adoption of these metrics, as demonstrated by implementations at organizations like AstraZeneca and in meropenem trihydrate method development, highlights their practical value in reducing environmental impact while maintaining analytical performance. As regulatory expectations evolve and sustainability requirements intensify, the strategic application of these assessment tools will become increasingly critical for developing analytical methods that balance performance, quality, and environmental responsibility.

From Theory to Practice: A Step-by-Step Guide to AQbD-GAC Method Development

Defining the Analytical Target Profile (ATP) with Green Objectives

In the modern pharmaceutical landscape, the development of analytical methods is undergoing a significant paradigm shift. The traditional approach, which focused primarily on technical performance, is now strategically integrating environmental sustainability through the incorporation of green chemistry principles directly into the Analytical Target Profile (ATP). The ATP, a foundational element of the Analytical Quality by Design (AQbD) framework, serves as a formal document that outlines the intended purpose of an analytical method and its required performance characteristics [34]. By embedding green objectives into the ATP, scientists predefine sustainability goals alongside accuracy, precision, and robustness, ensuring that the resulting methods are not only fit-for-purpose but also environmentally responsible [16] [35].

This integration represents a powerful synergy. AQbD provides a systematic, science-based approach for developing well-understood, robust, and reliable analytical methods [36] [37]. It begins with predefined objectives—the ATP—and employs risk assessment and structured experimentation to build quality into the method from the outset. Meanwhile, Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) aims to make analytical procedures more ecologically friendly by reducing the use of hazardous reagents, minimizing energy consumption, and cutting down waste generation [16] [3]. Framing analytical procedures within this integrated context supports the United Nations' Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production) and SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being) [3]. This article provides a comparative guide on how to define an ATP with green objectives, supported by experimental data and practical protocols from contemporary research.

The AQbD Framework and the Central Role of the Green ATP

The Systematic AQbD Workflow

The AQbD methodology is a structured process that ensures a method consistently meets its intended performance requirements throughout its lifecycle. The workflow, depicted below, begins with defining the ATP and progresses through risk assessment, optimization, and establishment of a control strategy [34].

Defining the ATP with Green Objectives

The ATP is the critical first step in AQbD. A well-constructed ATP for a chromatographic method, for example, might state: "The procedure must be able to accurately and precisely quantify the drug substance in film-coated tablets over the range of 70%-130% of the nominal concentration with accuracy and precision such that reported measurements fall within ± 3% of the true value with at least 95% probability" [34].

When enhanced with green objectives, the ATP expands to include explicit environmental targets. These can be qualitative or quantitative and may encompass:

- Solvent and Reagent Selection: Mandating the use of safer, bio-based, or less hazardous solvents (e.g., ethanol, acetone) over traditional toxic options (e.g., acetonitrile, methanol) [35] [18] [38].

- Waste Minimization: Setting targets for reduced waste generation, for instance, by using miniaturized systems or micro-extraction techniques [16].

- Energy Efficiency: Specifying the development of methods that operate at ambient temperature or with shorter run times to lower energy consumption [35].

- Sample Preparation: Prioritizing direct analysis or methods that minimize or eliminate derivatization, which requires additional reagents and generates waste [35].

Comparative Analysis: Conventional vs. Green-Objective-Driven ATPs

The integration of green objectives into the ATP directly influences the choices made during method development and optimization. The table below contrasts the outcomes of conventional and green-enhanced ATP approaches, based on recent case studies.

Table 1: Comparison of Method Outcomes from Conventional and Green-Enhanced ATP Approaches

| Aspect | Conventional ATP Approach | Green-Objective-Driven ATP Approach | Comparative Experimental Data from Case Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solvent Usage | Often uses larger volumes of acetonitrile or methanol. | Targets reduced volume and replacement with greener solvents like ethanol. | Meropenem HPLC: Used a QbD-driven method that reduced solvent consumption compared to prior methods [3].Metronidazole/Nicotinamide HPLC: Used only 1.5 mL of ethanol per run, the lowest volume among 21 compared methods [18]. |

| Analytical Performance | Performance is the sole focus; greenness is an afterthought. | Performance and greenness are balanced and achieved simultaneously. | Ensifentrine UPLC: Achieved ICH-compliant linearity (r²=0.9997) and precision while using an eco-friendly optimized mobile phase [4].Tafamidis HPLC: Demonstrated excellent linearity (R²=0.9998) and high sensitivity (LOQ of 0.0717 µg/mL) with a simple, buffer-free solvent system [38]. |

| Waste Generation | High waste generation due to larger column dimensions, higher flow rates, and longer run times. | Actively minimized through method optimization and miniaturization. | Treprostinil HPLC: An AQbD approach led to a short 6.0 min run time, reducing overall solvent waste [39]. |

| Greenness Score | Not typically assessed or reported. | Quantified using multiple metrics as a key method attribute. | Tafamidis HPLC: Achieved an AGREE score of 0.83, indicating excellent environmental compatibility [38].Metronidazole/Nicotinamide HPLC: Scored 0.75 on the AGREE tool, the highest among compared methods [18]. |

| Method Optimization | One-Variable-at-a-Time (OVAT), which is less efficient and may miss interactions. | Design of Experiments (DoE) for efficient understanding of factor interactions and robust design space. | Ensifentrine UPLC: Used a Central Composite Design to optimize column temperature, flow rate, and buffer pH [4].Tafamidis HPLC: A Box-Behnken Design optimized mobile phase composition, column temperature, and flow rate [38]. |

Experimental Protocols for Implementing a Green-Objective ATP

A Reusable Workflow for Green AQbD Method Development

The following workflow synthesizes protocols from multiple case studies for developing a stability-indicating HPLC method under a green ATP [3] [4] [39].

Define the Green ATP: Articulate the method's purpose (e.g., "quantify drug X in tablets and nanosponges"), performance criteria (linearity, accuracy, precision), and green objectives (e.g., "use ethanol-based mobile phase," "total run time <10 min," "waste <10 mL per analysis").

Technique Selection & Initial Scouting: Select a technique (e.g., RP-HPLC) that can meet the ATP. Perform initial scouting with different columns, organic modifiers (ethanol, acetone), and buffer pH to identify a starting point.