Green Validation in Pharmaceutical Analysis: Strategies, Tools, and Implementation for Sustainable Labs

This article provides a comprehensive overview of greenness validation methods in pharmaceutical analysis, addressing the critical need for sustainable laboratory practices.

Green Validation in Pharmaceutical Analysis: Strategies, Tools, and Implementation for Sustainable Labs

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of greenness validation methods in pharmaceutical analysis, addressing the critical need for sustainable laboratory practices. It explores the foundational principles of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) and details advanced methodological applications, including green chromatographic and spectroscopic techniques. The content offers practical troubleshooting and optimization strategies to overcome common implementation barriers and systematically reviews established and emerging greenness assessment tools for comparative method validation. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this guide serves as a strategic resource for integrating robust, eco-friendly validation protocols that align with regulatory trends and corporate sustainability goals without compromising analytical performance.

The Principles and Imperative of Green Analytical Chemistry

Defining Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) and Its Twelve Core Principles

Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) is a transformative approach that integrates the principles of green chemistry into analytical methodologies, aiming to ensure they are safe, non-toxic, environmentally friendly, and efficient in their use of materials, energy, and waste generation [1] [2]. In the context of pharmaceutical analysis, this paradigm shift is crucial for developing methods that minimize environmental impact while maintaining high standards of accuracy, precision, and reliability required for drug development and validation [3].

The foundation of Green Analytical Chemistry lies in the 12 principles of green chemistry, which provide a comprehensive framework for designing and implementing environmentally benign analytical techniques [2]. GAC addresses the significant environmental concerns associated with traditional analytical methods, which often rely on toxic reagents and solvents, generate substantial hazardous waste, and consume vast amounts of energy [1] [4].

The transition to GAC is driven by multiple factors:

- Environmental Responsibility: Analytical chemists are increasingly recognizing the need to minimize the ecological footprint of their work through sustainable practices [1].

- Safety: Adopting green principles reduces exposure to hazardous chemicals, creating a safer working environment for researchers and laboratory personnel [1] [4].

- Economic Efficiency: Green methods often reduce costs by minimizing consumption of expensive reagents and solvents, lowering energy requirements, and reducing waste disposal expenses [1] [4].

- Regulatory Compliance: As environmental regulations become more stringent, knowledge of GAC ensures that pharmaceutical methods meet these evolving standards [1].

For pharmaceutical professionals, GAC offers a pathway to align drug development and quality control with broader sustainability goals without compromising analytical performance [3] [5].

The Twelve Core Principles of Green Analytical Chemistry

The 12 principles of Green Analytical Chemistry serve as a strategic framework for reimagining analytical methodologies to meet sustainability, safety, and environmental responsibility demands [2]. These principles adapt the original green chemistry principles specifically to analytical processes.

Principle-by-Principle Explanation

- Direct Analytical Techniques: Prioritize methods that avoid sample preparation and treatment, thereby preventing waste generation at the source [2].

- Minimal Sample Size: Design methods that require minimal sample sizes to reduce reagent consumption and waste production [2].

- In-situ Measurements: Where possible, perform measurements in situ to avoid sample transportation and preservation needs [2].

- Integration of Analytical Processes: Combine sampling, sample preparation, and analysis into a single, streamlined process to enhance efficiency and reduce resource use [2].

- Automation and Miniaturization: Implement automated and miniaturized methods to decrease sample and solvent consumption while improving safety [2].

- Derivatization Avoidance: Avoid derivatization steps that require additional reagents and generate extra waste unless absolutely necessary for the analysis [2].

- Energy Minimization: Reduce energy consumption by developing methods that operate under ambient temperature and pressure conditions whenever feasible [2].

- Green Solvents and Reagents: Preferentially use non-toxic, biodegradable, or recyclable solvents and reagents [2].

- Waste Prevention and Recycling: Prioritize waste prevention over treatment after generation, and implement recycling systems for solvents and reagents [2].

- Multi-analyte Determination: Favor methods that can determine multiple analytes simultaneously to maximize information obtained from each analytical procedure [2].

- Green Source of Energy: Utilize renewable energy sources to power analytical equipment when possible [2].

- Safe and Green Methods: Choose and develop methods that are inherently safe for analysts and the environment throughout their lifecycle [2].

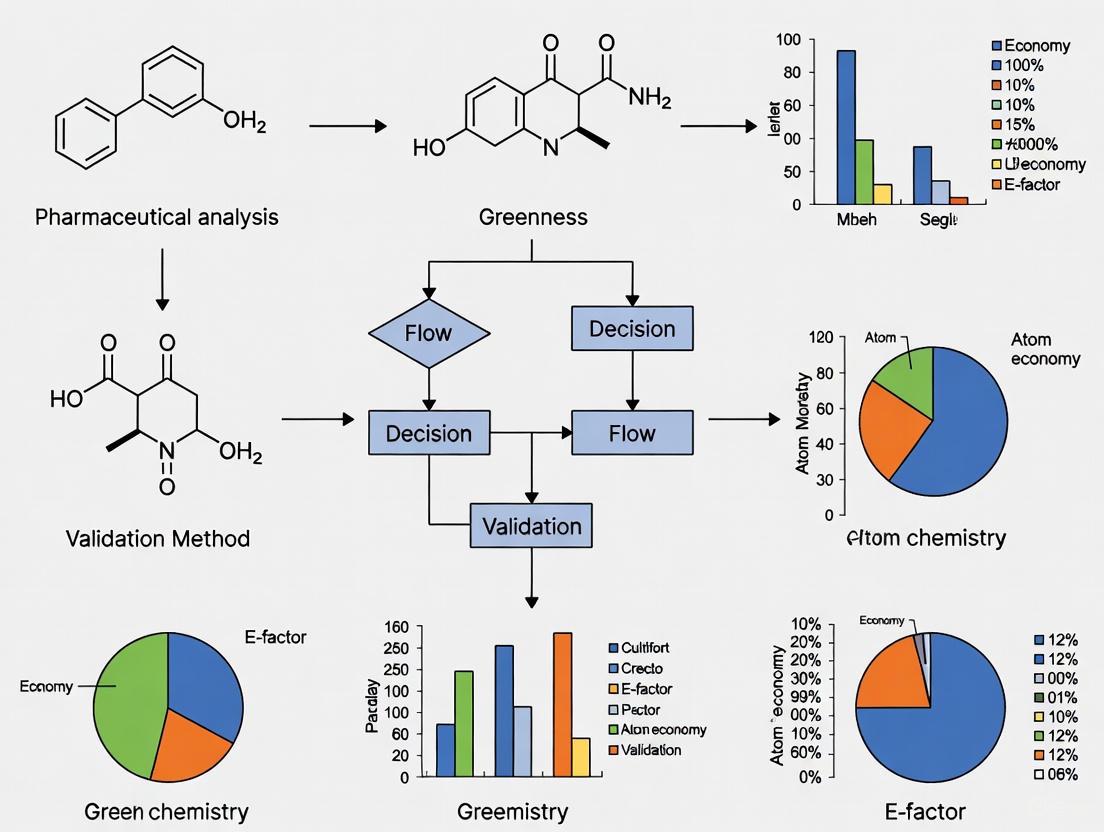

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships and workflow integration of these twelve core principles:

GAC Principles Workflow: This diagram illustrates the sequential application of the twelve core principles in designing sustainable analytical methods, culminating in environmentally responsible analysis.

Greenness Assessment Tools and Metrics

A critical component of implementing GAC is the ability to objectively evaluate and compare the environmental performance of analytical methods. Several assessment tools have been developed, each with unique approaches and scoring systems.

Comparison of Major Greenness Assessment Tools

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of Greenness Assessment Tools for Analytical Methods

| Tool Name | Assessment Approach | Scoring System | Key Parameters Measured | Pharmaceutical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEMI (National Environmental Methods Index) [5] | Qualitative, pictogram-based | Four-quadrant diagram (green/white) | PBT substances, hazardous chemicals, corrosivity (pH), waste generation (<50g) | Basic screening of method greenness |

| GAPI (Green Analytical Procedure Index) [1] | Semi-quantitative, multi-criteria | Color-coded pictogram (green-yellow-red) | Entire method lifecycle from sampling to waste management | Comprehensive evaluation of analytical procedures |

| AGREE (Analytical GREEnness) [1] [6] | Quantitative, software-based | 0-1 scale (1 = ideal) | All 12 GAC principles with weighted scores | Comparative greenness scoring with detailed output |

| Analytical Eco-Scale [5] | Semi-quantitative, penalty points | 100-point base (≥75 = excellent) | Reagent toxicity, energy consumption, waste amount | Practical assessment with clear thresholds |

| ChlorTox [5] | Toxicity-focused, comparative | Total ChlorTox score (lower = better) | Chemical hazard relative to chloroform, mass used | Toxicity risk assessment for method components |

Application of Assessment Tools in Pharmaceutical Analysis

In pharmaceutical analysis, these tools enable objective comparison between traditional and green methods. For example, a study evaluating HPLC methods for paclitaxel analysis used seven different assessment tools (NEMI, Complex NEMI, Analytical Eco-Scale, SPMS, ChlorTox, RGBfast, and BAGI) to identify the most sustainable approaches [5]. The findings revealed that methods with improved greenness profiles maintained analytical performance while reducing environmental impact.

Similarly, the greenness assessment of a newly developed RP-HPLC method for Flavokawain A quantification demonstrated its environmental sustainability with an AGREE metric score of 0.79, confirming its suitability for routine quality control in pharmaceutical formulations [6].

Green Analytical Techniques and Methodologies

Implementing GAC principles involves adopting specific techniques and methodologies that reduce environmental impact while maintaining analytical performance.

Key Green Analytical Techniques

- Miniaturization: Reducing the scale of analytical systems dramatically decreases solvent and sample consumption. Lab-on-a-chip technologies and microfluidic devices exemplify this approach [4].

- Alternative Solvent Systems: Replacing traditional hazardous solvents with safer alternatives like water, supercritical CO₂, ionic liquids, or bio-based solvents [2] [4].

- Solventless Extraction Techniques: Methods such as Solid-Phase Microextraction (SPME) eliminate or drastically reduce solvent use in sample preparation [2] [4].

- Energy-Efficient Processes: Utilizing microwave-assisted extraction, ultrasound-assisted extraction, and photo-induced processes to reduce energy consumption [2].

- On-site and Real-time Analysis: Portable instruments and sensors enable analysis at the sample source, reducing transportation needs and enabling immediate decision-making [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Green Pharmaceutical Analysis

| Reagent/Solution | Function in Analysis | Green Alternatives | Environmental & Safety Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Organic Solvents (acetonitrile, methanol) | Mobile phase in chromatography, extraction | Supercritical CO₂, water, ionic liquids, bio-based solvents | Reduced toxicity, biodegradability, lower VOC emissions |

| Derivatizing Agents | Analyte modification for detection | Direct analysis methods, alternative detection strategies | Eliminates hazardous waste, simplifies procedures |

| Hazardous Extraction Solvents (chloroform, hexane) | Sample preparation and extraction | Solid-phase microextraction, mechanical extraction | Minimal solvent use, improved analyst safety |

| Energy-Intensive Processes | Sample treatment and analysis | Microwave-assisted, ultrasound-assisted methods | Lower energy consumption, faster analysis times |

Experimental Protocols and Case Studies in Pharmaceutical Analysis

Case Study 1: Green RP-HPLC Method for Flavokawain A

Experimental Protocol:

- Chromatographic Conditions: Shim-pack GIST C18 column (150×4.6mm, 3μm) with methanol:water (85:15 v/v) mobile phase at 1.0 mL/min flow rate [6].

- Sample Preparation: Minimal preparation using green solvents [6].

- Detection: UV detection with elution at 4.8 minutes [6].

- Validation Parameters: Linearity (2-12μg/mL, R²=0.9999), LOD (0.281μg/mL), LOQ (0.853μg/mL), recovery (99.2-101.3%), precision (%RSD <2%) [6].

Greenness Assessment: The method achieved an AGREE metric score of 0.79, confirming its environmental sustainability while maintaining high accuracy and precision for pharmaceutical quality control [6].

Case Study 2: Green UHPLC-MS/MS for Trace Pharmaceutical Monitoring

Experimental Protocol:

- Analytical Technique: UHPLC-MS/MS with short analysis time (10 minutes) [7].

- Sample Preparation: Solid-phase extraction without evaporation step, significantly reducing solvent consumption and energy use [7].

- Analytes: Simultaneous determination of carbamazepine, caffeine, and ibuprofen in water [7].

- Validation: Specificity, linearity (correlation coefficients ≥0.999), precision (RSD <5.0%), accuracy (recovery 77-160%) following ICH Q2(R2) guidelines [7].

Greenness Assessment: This method exemplifies "green and blue analytical chemistry" by combining high sensitivity with minimal environmental impact through optimized sample preparation and rapid analysis [7].

Case Study 3: Greenness Assessment of HPLC Methods for Paclitaxel

Experimental Protocol:

- Evaluation Framework: Seven assessment tools (NEMI, Complex NEMI, Analytical Eco-Scale, SPMS, ChlorTox, RGBfast, and BAGI) applied to multiple HPLC methods [5].

- Key Findings: Methods 3 and 5 demonstrated superior greenness profiles, with method 3 achieving 72.5 BAGI and method 5 scoring 90 on the Analytical Eco-Scale [5].

- Sustainability Indicators: High scores correlated with minimal waste generation, reduced hazardous material usage, and improved operational efficiency [5].

Green Analytical Chemistry represents a fundamental shift in how pharmaceutical analysis is conceptualized, developed, and implemented. The twelve core principles of GAC provide a comprehensive framework for creating analytical methods that minimize environmental impact while maintaining the high standards of accuracy, precision, and reliability required in drug development and quality control.

The adoption of GAC in pharmaceutical analysis is no longer optional but essential for aligning with global sustainability initiatives, regulatory requirements, and ethical responsibilities. Through the implementation of greenness assessment tools, miniaturization strategies, alternative solvents, and energy-efficient technologies, pharmaceutical scientists can significantly reduce the environmental footprint of analytical methods without compromising performance.

As the field continues to evolve, emerging technologies like artificial intelligence, advanced automation, and novel green materials will further enhance the capabilities of Green Analytical Chemistry, driving innovation in sustainable pharmaceutical analysis [2].

The adoption of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) principles in the pharmaceutical industry is being increasingly influenced and supported by modern regulatory guidelines. The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH), through its recently revised guidelines Q2(R2) and Q14, has established a science- and risk-based framework that provides the flexibility needed to develop and validate environmentally sustainable analytical methods [8]. Concurrently, the FDA's adoption of these guidelines and its ongoing consolidation of stability testing requirements in the draft Q1 guidance create a regulatory environment where green method integration is not only possible but encouraged [9] [10]. This guide examines how these regulatory drivers are facilitating a shift toward sustainable practices while maintaining the rigorous data quality standards required for pharmaceutical analysis.

Understanding the Regulatory Framework

The regulatory landscape for pharmaceutical analysis is undergoing a significant transformation, moving from prescriptive requirements to a more flexible, science-based approach. This evolution directly facilitates the adoption of green analytical methods by focusing on method performance rather than specific procedural steps.

ICH Guidelines: The Foundation of Modern Analytical Validation

ICH Q2(R2) - Validation of Analytical Procedures: This revised guideline provides the global standard for demonstrating that analytical procedures are suitable for their intended use [8]. The updated version expands its scope to include modern technologies and emphasizes a science- and risk-based approach to validation, which allows for the justification of green method modifications through proper validation data [8].

ICH Q14 - Analytical Procedure Development: This complementary guideline introduces a systematic framework for analytical procedure development and establishes the concept of the Analytical Target Profile (ATP) [8]. The ATP prospectively defines the required quality criteria for a method, enabling scientists to develop greener methods that meet performance requirements without being constrained by traditional approaches [8].

FDA's Role in Implementing ICH Guidelines

The FDA, as a key member of ICH, adopts and implements these harmonized guidelines [8]. For pharmaceutical companies, this means that complying with ICH standards directly satisfies FDA requirements for regulatory submissions such as New Drug Applications (NDAs) and Abbreviated New Drug Applications (ANDAs) [8]. The FDA's recent draft guidance on "Q1 Stability Testing of Drug Substances and Drug Products" further demonstrates the agency's commitment to harmonization and modernization of analytical requirements [9] [10].

Comparative Analysis: Traditional vs. Green Methods Under Current Guidelines

The following comparison examines how green analytical methods perform relative to traditional approaches within the framework of modern regulatory guidelines.

Performance Comparison of Analytical Methods

Table 1: Comparative analysis of traditional versus green analytical methods across key parameters

| Parameter | Traditional HPLC Method | Green RP-HPLC Method (Flavokawain A) | Green UHPLC-MS/MS Method (Pharmaceuticals in Water) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organic Solvent Consumption | High (often >50 mL/sample) | Reduced (methanol:water 85:15 v/v) [6] | Optimized to eliminate evaporation step [7] |

| Analysis Time | Longer run times (20-30 min) | Fast (4.8 min retention time) [6] | Rapid (10 min total analysis time) [7] |

| Waste Generation | Significant (>50 g/sample) | Minimal [6] | Substantially reduced [7] |

| Sensitivity | Variable | LOD: 0.281 μg/mL, LOQ: 0.853 μg/mL [6] | Exceptional (LOD: 100-300 ng/L) [7] |

| Accuracy | Standard | 99.2-101.3% recovery [6] | 77-160% recovery (complex matrix) [7] |

| Precision | Standard | %RSD <2% [6] | RSD <5.0% [7] |

| Linearity | Acceptable | R²=0.9999 (2-12 μg/mL) [6] | R² ≥0.999 [7] |

| Greenness Score | Not assessed | AGREE score: 0.79 [6] | Incorporates "blue" analytical attributes [7] |

Regulatory Flexibility and Green Method Implementation

The transition from a prescriptive "check-the-box" approach to a science-based lifecycle model under ICH Q2(R2) and Q14 represents a significant regulatory driver for green method adoption [8]. This shift enables:

Alternative Approaches: Scientists can justify environmentally friendly modifications through proper validation data, as emphasized in the FDA's draft Q1 guidance which provides "alternative, scientifically justified approaches" [9].

Lifecycle Management: The updated guidelines recognize method validation as a continuous process rather than a one-time event, allowing for post-approval improvements to enhance sustainability [8].

Control Strategy Flexibility: The enhanced approach in Q14 permits more flexible post-approval changes when supported by risk assessment and understanding of the method [8].

Greenness Assessment Methodologies for Regulatory Compliance

Multiple standardized tools have emerged to quantitatively evaluate the environmental impact of analytical methods, providing objective data for regulatory justification.

Comprehensive Greenness Assessment Tools

Table 2: Standardized tools for assessing the environmental impact of analytical methods

| Assessment Tool | Key Evaluation Parameters | Scoring System | Regulatory Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| NEMI | PBT substances, hazardous chemicals, corrosivity, waste generation [5] | Quadrant pictogram (green/blank) | Preliminary screening for method classification |

| Analytical Eco-Scale | Reagent hazards, energy consumption, waste management [5] | 100-point base with penalty deductions (≥75=excellent) | Semi-quantitative comparison and optimization target |

| AGREE | Comprehensive GAC principles assessment [6] | 0-1 scale (closer to 1=greener) | Overall environmental impact score for regulatory documentation |

| ChlorTox | Chemical risk relative to chloroform [5] | Total ChlorTox score (lower=better) | Specific toxicological impact assessment |

| SPMS | Sample amount, extractant type/volume, procedure, energy/waste [5] | Weighted sustainability score | Sample preparation optimization focus |

Case Study: Greenness Assessment of Paclitaxel HPLC Methods

Recent research demonstrates the practical application of these assessment tools in pharmaceutical analysis. A comprehensive evaluation of nine different HPLC methods for paclitaxel quantification revealed significant sustainability variations [5]. Methods 3 and 5 emerged as the most sustainable, with Method 3 achieving a 72.5 BAGI score and Method 5 scoring 90 on the Analytical Eco-Scale, reflecting high eco-friendliness, minimal waste, and operational efficiency [5]. In contrast, Methods 6, 8, and 9 required optimization in hazardous material usage, energy consumption, and waste management [5]. This systematic assessment provides a framework for selecting methods that balance analytical performance with environmental considerations in regulatory submissions.

Experimental Protocols for Green Analytical Methods

Green RP-HPLC Method for Flavokawain A Analysis

Intended Use: Quantification of Flavokawain A in bulk drug and in-house tablet dosage forms for quality control [6].

Experimental Protocol:

- Chromatographic Conditions:

- Column: Shim-pack GIST C18 (150×4.6mm, 3μm)

- Mobile Phase: Methanol:water (85:15 v/v)

- Flow Rate: 1.0 mL/min

- Detection: UV-Vis at suitable wavelength

Sample Preparation:

- Bulk drug: Direct dissolution in mobile phase

- Tablets: Powder extraction and filtration

Validation Parameters (per ICH Q2(R2) [8]):

- Linearity: 2-12μg/mL (R²=0.9999)

- Accuracy: 99.2-101.3% recovery

- Precision: %RSD <2%

- LOD/LOQ: 0.281 and 0.853μg/mL respectively

- Specificity: No interference from excipients

Greenness Assessment:

- AGREE metric score: 0.79 [6]

- Solvent reduction: 85:15 methanol:water ratio

- Waste minimization: Direct mobile phase composition

Green UHPLC-MS/MS for Trace Pharmaceutical Monitoring

Intended Use: Simultaneous determination of carbamazepine, caffeine, and ibuprofen in water and wastewater [7].

Experimental Protocol:

- Chromatographic Conditions:

- Technique: UHPLC-MS/MS

- Analysis Time: 10 minutes

- Sample Preparation: Solid-phase extraction without evaporation step

Method Validation (per ICH Q2(R2) [7] [8]):

- Specificity: No matrix interference

- Linearity: Correlation coefficients ≥0.999

- Precision: RSD <5.0%

- Accuracy: Recovery rates 77-160% (complex matrix)

- LOD: 100-300 ng/L

- LOQ: 300-1000 ng/L

Green Innovations:

- Elimination of energy-intensive evaporation step [7]

- Reduced solvent consumption

- Minimal waste generation

- Short analysis time (10 minutes)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key reagents and materials for implementing green analytical methods

| Item | Function | Green Attributes |

|---|---|---|

| RP-HPLC Column (C18, 150×4.6mm, 3μm) | Chromatographic separation of analytes [6] | Enables fast analysis with reduced solvent consumption |

| Methanol-Water Mobile Phase | Solvent system for reverse-phase chromatography [6] | Reduced toxicity compared to acetonitrile-based systems |

| Solid-Phase Extraction Cartridges | Sample clean-up and concentration [7] | Eliminates need for large solvent volumes in liquid-liquid extraction |

| UHPLC-MS/MS System | High-sensitivity detection and quantification [7] | Reduced analysis time and solvent use compared to conventional HPLC |

| Greenness Assessment Software | Quantitative evaluation of method environmental impact [5] | Enables objective comparison and optimization for sustainability |

Implementation Workflow for Regulatory Compliance

The following diagram illustrates the integrated approach to developing and validating green analytical methods within the modern regulatory framework:

Green Method Implementation Workflow: This workflow integrates regulatory requirements with green chemistry principles throughout the analytical method lifecycle.

Future Directions and Strategic Recommendations

The regulatory landscape continues to evolve toward greater support for sustainable analytical practices. The FDA's draft Q1 guidance on stability testing, currently open for comments until August 25, 2025, represents further harmonization and may provide additional opportunities for green method implementation [10]. Pharmaceutical companies should consider these strategic actions:

Proactive Adoption: Implement the enhanced approach from ICH Q14 to build environmental considerations into method development from the outset [8].

Standardized Assessment: Incorporate quantitative greenness metrics (AGREE, Analytical Eco-Scale) into routine method validation protocols [6] [5].

Cross-Functional Training: Educate quality and regulatory affairs teams on the flexibility offered by modern guidelines to facilitate green method acceptance.

Continuous Monitoring: Track regulatory updates, particularly the finalization of the Q1 guidance, to identify emerging opportunities for sustainable analytical practices [9].

The convergence of regulatory modernization and environmental sustainability represents a pivotal opportunity for the pharmaceutical industry. By leveraging the flexibility in contemporary ICH and FDA guidelines, organizations can successfully implement green analytical methods that meet regulatory requirements while reducing environmental impact.

The Environmental and Economic Impact of Traditional Pharmaceutical Analysis

Within pharmaceutical research and development, analytical chemistry serves as the critical backbone for drug quality control, stability testing, and bioavailability studies. Traditional analytical methods, particularly those relying on high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), have long been the gold standard for their reliability and precision. However, these established techniques carry significant environmental and economic burdens that conflict with global sustainability initiatives. A comprehensive greenness assessment of 174 standard methods from CEN, ISO, and pharmacopoeias reveals alarming results: 67% of methods scored below 0.2 on the AGREEprep scale (where 1 represents ideal greenness), with methods for environmental analysis of organic compounds performing particularly poorly at 86% scoring below this threshold [11]. This article provides a systematic comparison between traditional and emerging green analytical methods, examining their environmental footprints, economic implications, and practical applications within modern pharmaceutical development.

Environmental Footprint: Quantifying the Impact

Carbon Emissions and Broader Environmental Consequences

The pharmaceutical sector's carbon footprint extends significantly beyond direct manufacturing to include analytical operations. From 1995 to 2019, the global pharmaceutical greenhouse gas footprint grew by 77%, primarily driven by rising pharmaceutical expenditure and stalled efficiency gains after 2008 [12]. High-income countries contributed 9-10 times higher pharmaceutical greenhouse gas footprints per capita compared to lower-middle-income countries during this period [12].

The environmental impact of analytical chemistry manifests across multiple dimensions:

- Solvent Consumption: Traditional HPLC methods typically consume hundreds of milliliters of organic solvents per day of operation, often employing acetonitrile and methanol which present toxicity concerns and substantial waste management challenges [13].

- Energy Intensity: Analytical instruments requiring continuous operation, temperature control, or high-pressure conditions contribute disproportionately to laboratory energy consumption [13].

- Waste Generation: Conventional methods frequently produce >10 mL of hazardous waste per sample without integrated treatment strategies, creating ongoing environmental liabilities [13].

Greenness Assessment Metrics for Analytical Methods

The scientific community has developed specialized metrics to evaluate the environmental performance of analytical methods, moving beyond simple efficiency measures to comprehensive sustainability assessments:

Table 1: Greenness Assessment Metrics for Analytical Methods

| Metric | Assessment Focus | Scoring System | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEMI [13] | Basic environmental criteria | Binary pictogram (pass/fail) | Simple, accessible | Lacks granularity, limited scope |

| Analytical Eco-Scale [13] | Penalty points for non-green attributes | Base score of 100 minus penalty points | Facilitates method comparison | Subjective penalty assignments |

| GAPI [13] | Entire analytical process | Five-level color-coded pictogram | Comprehensive visual assessment | No overall score, somewhat subjective |

| AGREE [13] | 12 principles of green analytical chemistry | 0-1 numerical score + circular pictogram | Comprehensive, user-friendly, facilitates comparison | Doesn't fully account for pre-analytical processes |

| AGREEprep [11] [13] | Sample preparation stage specifically | 0-1 numerical score | Focuses on often problematic sample preparation | Must be used with broader method evaluation tools |

| AGSA [13] | Multiple green criteria | 0-1 score + star-shaped diagram | Intuitive visualization, integrated scoring | Complex assessment process |

| CaFRI [13] | Carbon emissions | Emission reduction percentage | Aligns with climate-focused sustainability goals | Narrow focus on carbon footprint |

The following workflow illustrates how these metrics are typically applied in pharmaceutical analysis to evaluate method greenness:

Graph 1: Greenness assessment workflow for pharmaceutical analysis methods

Economic Implications: The Hidden Costs of Traditional Methods

Direct and Indirect Economic burdens

While traditional pharmaceutical analysis methods deliver essential analytical performance, their economic implications extend far beyond initial equipment investments:

- Solvent Consumption Costs: A conventional HPLC system operating with acetonitrile-based mobile phases can consume $5,000-15,000 annually in solvent purchases alone, with costs fluctuating based on petroleum prices and supply chain disruptions [13] [14].

- Waste Management Expenses: Hazardous solvent disposal incurs substantial costs, typically 3-5 times the original purchase price of the solvents, creating a compounding financial burden throughout method lifetimes [13].

- Energy Consumption: Traditional methods requiring lengthy analysis times, elevated temperatures, or high-pressure operation contribute significantly to laboratory energy budgets, with carbon footprint implications now increasingly regulated [13].

- Regulatory Compliance: As documented by [11], most official pharmacopoeial methods demonstrate poor greenness performance, creating regulatory inertia that impedes adoption of more sustainable and cost-effective alternatives.

Broader Industry Economic Context

The economic pressures facing pharmaceutical companies extend beyond analytical operations. The industry faces a significant "patent cliff" with over $300 billion in sales at risk through 2030 due to expiring patents on high-revenue products [15]. Simultaneously, 68% of life sciences executives anticipate revenue increases in 2025 while facing pricing pressures and the need for digital transformation [15]. These competing priorities create a complex economic landscape where efficiency gains from green analytical methods can provide meaningful competitive advantages.

Green Analytical Methodologies: Sustainable Alternatives

Principles of Green Analytical Chemistry

Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) has emerged as a specialized discipline focused on minimizing the environmental footprint of analytical methods while maintaining rigorous performance standards [13]. The field operates according to 12 principles that guide method development toward sustainability, with core objectives including:

- Miniaturization and solvent reduction

- Substitution of hazardous chemicals with safer alternatives

- Integration of analytical processes to reduce resource consumption

- Designing methods for waste minimization and operator safety

Case Study: Green HPLC Method for Sacubitril/Valsartan Analysis

A recently published green HPLC-fluorescence method for simultaneous analysis of sacubitril and valsartan demonstrates the practical application of these principles [14]. The method achieves comparable analytical performance to conventional approaches while significantly improving environmental and economic metrics:

Table 2: Method Comparison - Traditional vs. Green HPLC for Sacubitril/Valsartan

| Parameter | Traditional HPLC-UV Method [14] | Green HPLC-Fluorescence Method [14] |

|---|---|---|

| Mobile Phase | Acetonitrile/water or methanol/water mixtures | 30 mM phosphate (pH 2.5) and ethanol (40:60 v/v) |

| Solvent Consumption per Run | Typically 2-5 mL | ~1 mL |

| Column Type | Specialized columns (monolithic, cyano) | Conventional C18 column |

| Detection | UV detection | Fluorescence detection with programmed wavelengths |

| Linearity Range (Sacubitril) | Not specified | 0.035-2.205 µg/mL |

| Linearity Range (Valsartan) | Not specified | 0.035-4.430 µg/mL |

| Greenness Scores | Not assessed | Evaluated with multiple metrics: AGREE, complex GAPI, AGSA, CaFRI |

| Primary Environmental Advantage | - | Ethanol replaces more hazardous acetonitrile |

| Economic Advantage | - | Lower solvent costs, conventional column |

Case Study: Green RP-HPLC for Flavokawain A

Further demonstrating the feasibility of green analytical transitions, researchers developed and validated an eco-friendly reverse-phase HPLC method for quantification of Flavokawain A in bulk and tablet dosage forms [6]. The method employs methanol:water (85:15 v/v) mobile phase and achieved an Analytical Greenness (AGREE) metric score of 0.79, significantly higher than conventional approaches [6]. The methodology demonstrates excellent linearity (R²=0.9999) over 2-12μg/mL range with recovery values of 99.2-101.3%, proving that green methods can maintain rigorous performance standards while reducing environmental impact [6].

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Green Pharmaceutical Analysis

Detailed Protocol: Green HPLC for Sacubitril/Valsartan

Instrumentation and Conditions [14]:

- HPLC System: Agilent 1200 series with isocratic pump and fluorescence detector

- Column: Conventional C18 column (150 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 μm)

- Mobile Phase: 30 mM phosphate buffer (pH 2.5):ethanol (40:60 v/v)

- Flow Rate: 1.0 mL/min

- Temperature: Ambient

- Injection Volume: 20 μL

- Detection: Programmable fluorescence detection with wavelength changes during run

- Run Time: <6 minutes

Sample Preparation [14]:

- Pharmaceutical Formulation: Tablets powdered and extracted with ethanol

- Plasma Samples: Protein precipitation with methanol followed by centrifugation

- Internal Standard: Ibuprofen used for quantification normalization

Validation Parameters [14]:

- Linearity: 0.035-2.205 μg/mL for sacubitril, 0.035-4.430 μg/mL for valsartan

- Precision: %RSD <2%

- Accuracy: Recovery 99.2-101.3%

- Specificity: No interference from excipients or plasma components

Detailed Protocol: Green RP-HPLC for Flavokawain A

Chromatographic Conditions [6]:

- Column: Shim-pack GIST C18 (150×4.6mm, 3μm)

- Mobile Phase: Methanol:water (85:15 v/v)

- Flow Rate: 1.0 mL/min

- Detection: Not specified (conventional UV/Vis likely)

- Elution Time: 4.8 minutes

- Linearity Range: 2-12 μg/mL (R²=0.9999)

Greenness Assessment [6]:

- AGREE Score: 0.79

- Additional Validation: LOD 0.281 μg/mL, LOQ 0.853 μg/mL

- Application: Successfully applied to bulk drug and tablet formulations

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Transitioning to green analytical methods requires careful selection of reagents and materials that maintain analytical performance while reducing environmental impact:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Green Pharmaceutical Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Traditional Application | Green Alternative | Function | Environmental Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mobile Phase Solvents | Acetonitrile, Tetrahydrofuran | Ethanol, Methanol [14], Bio-based solvents | Solubilize analytes, create separation matrix | Reduced toxicity, better biodegradability, renewable sourcing |

| Buffers | Phosphate buffers with acetonitrile | Ethanol-buffer mixtures [14] | Adjust pH, control ionization | Reduced organic solvent percentage, less hazardous waste |

| Extraction Solvents | Chlorinated solvents, hexane | Ethanol, supercritical CO₂, water [13] | Extract analytes from complex matrices | Lower toxicity, reduced VOC emissions, improved operator safety |

| Columns | Specialized columns requiring specific mobile phases | Conventional C18 columns with green mobile phases [14] | Analytical separation | Broener solvent compatibility, longer lifetime with green solvents |

| Derivatization Agents | Hazardous labeling reagents | Avoidance through alternative detection [13] | Enhance detection sensitivity | Reduced reagent toxicity, simplified waste stream |

| Sample Preparation Materials | Disposable plasticware, cartridges | Miniaturized systems, reusable components [13] | Sample clean-up and concentration | Reduced plastic waste, lower resource consumption |

The comprehensive comparison between traditional and green pharmaceutical analysis methods reveals a clear trajectory for the field. Traditional approaches, while familiar and robust, carry substantial environmental and economic burdens that are increasingly untenable amid climate concerns and cost pressures. The documented 77% growth in pharmaceutical greenhouse gas emissions from 1995-2019 underscores the urgent need for reform [12]. Green analytical methods, as demonstrated by the sacubitril/valsartan and Flavokawain A case studies, provide viable pathways to maintain analytical excellence while significantly reducing environmental impacts. The transition to greener methodologies represents not merely an ecological imperative but a strategic economic opportunity, potentially yielding 11% value relative to revenue through AI-enhanced efficiencies and reduced resource consumption [15]. As the industry faces a transformative era defined by digital advancement, regulatory evolution, and sustainability mandates, the adoption of green analytical chemistry principles will be essential for creating a resilient, economically viable, and environmentally responsible pharmaceutical ecosystem.

The control of impurities in pharmaceutical products is a critical pillar of drug safety and quality, governed by a well-defined regulatory landscape primarily shaped by the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) Q3A-Q3D guidelines. These frameworks provide detailed classifications and control strategies for organic (Q3A(R2)/Q3B(R2)), elemental (Q3D), and residual solvent (Q3C(R8)) impurities, ensuring patient safety worldwide. In parallel, the field of analytical chemistry is undergoing a significant transformation driven by the principles of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC), which aims to minimize the environmental impact of analytical methods by reducing hazardous chemical use, energy consumption, and waste generation [16] [7].

This paradigm shift creates a compelling intersection where regulatory rigor meets environmental responsibility. Traditional methods for impurity analysis, while compliant, often utilize substantial volumes of organic solvents and generate considerable waste. The contemporary challenge lies in developing analytical procedures that satisfy stringent ICH/USP validation requirements while aligning with GAC principles. This guide systematically compares impurity classification frameworks and their integration with green assessment tools, providing researchers with methodologies to advance sustainable pharmaceutical analysis without compromising data quality or regulatory compliance.

Regulatory Frameworks for Impurity Classification

The classification of impurities dictates their required control strategies, acceptance criteria, and analytical reporting. The following table summarizes the core regulatory frameworks.

Table 1: Comparison of Key ICH Impurity Classification Guidelines

| Guideline | Impurity Type | Scope & Classification | Key Control Strategies | Key Analytical Techniques |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICH Q3A(R2) | Organic Impurities (Drug Substance) | - Identified: Known and unidentified impurities.- Qualified: Levels justified by safety data. | - Establish reporting, identification, and qualification thresholds based on maximum daily dose.- Generate impurity reference standards. | - HPLC/UHPLC with UV, PDA, MS detection.- GC, CE. |

| ICH Q3B(R2) | Organic Impurities (Drug Product) | - Degradation products from drug substance or product excipients.- Classification similar to Q3A. | - Thresholds based on maximum daily dose.- Forced degradation studies to predict stability.- Specification setting for significant degradation products. | - HPLC/UHPLC with UV, PDA, MS detection.- Stability-indicating methods. |

| ICH Q3C(R8) | Residual Solvents | - Class 1: Solvents to be avoided (known human carcinogens, strong environmental hazards).- Class 2: Solvents to be limited (nongenotoxic animal carcinogens, other irreversible toxicities).- Class 3: Solvents with low toxic potential. | - Set limits based on Permitted Daily Exposure (PDE) for Class 1 & 2.- Prefer use of Class 3 solvents.- Options: Supplier control, testing on final product. | - Gas Chromatography (GC) with FID, ECD, or MS detection.- Headspace sampling is common. |

| ICH Q3D (R2) | Elemental Impurities | - Class 1: Human toxicants with low PDE (As, Cd, Hg, Pb).- Class 2: Route-dependent toxicants (2A: high probability of occurrence, e.g., Co, Ni; 2B: lower probability).- Class 3: Low toxicity by oral route but require consideration for other routes. | - Risk-assessment based on scientific rationale.- Sources: Catalysts, raw materials, manufacturing equipment.- Options: Component control, testing on final product. | - Inductively Coupled Plasma-Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS).- Inductively Coupled Plasma-Optical Emission Spectroscopy (ICP-OES). |

The pharmacopeial harmonization of these guidelines is a critical ongoing process. The United States Pharmacopeia (USP) general chapter <233> "Elemental Impurities—Procedures" has been updated to align with the ICH Q3D principles, with the latest version becoming official on May 1, 2026 [17]. This chapter details validated procedures (e.g., ICP-MS, ICP-OES) and permits the use of any alternative method that meets its stringent validation criteria, which now explicitly include a risk-assessment process aligned with ICH Q3D [17] [18]. This evolution underscores a regulatory preference for a science-based, risk-managed approach to impurity control.

Greenness Assessment of Analytical Methods

Selecting an analytical technique is no longer based solely on performance parameters like detection limit or accuracy. A holistic approach now balances analytical performance, environmental impact, and economic cost [16]. Several tools have been developed to quantify the greenness of analytical procedures.

Table 2: Key Tools for Assessing the Greenness of Analytical Methods

| Assessment Tool | Type | Key Assessment Criteria | Scoring & Output | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analytical Eco-Scale | Semi-quantitative | Penalty points for hazardous reagents, energy consumption, waste generation. | - Ideal score = 100.- ≥75: Excellent greenness.- 50-74: Acceptable greenness. | Quick, practical profiling of a single method's environmental footprint [5]. |

| AGREE (Analytical Greenness) | Quantitative | Evaluates all 12 GAC principles via a unified algorithm. | Score 0-1 (closer to 1 is greener); pictogram with 12 segments. | Comprehensive, principle-based comparison of multiple methods [6] [16]. |

| NEMI (National Environmental Methods Index) | Qualitative | Four criteria: PBT, hazardous, corrosive (pH<2 or >12), waste >50g. | Pictogram with four quadrants; green = pass. | Simple, initial screening of method greenness [5]. |

| GAPI (Green Analytical Procedure Index) | Qualitative | Comprehensive, covers entire method lifecycle from sampling to waste disposal. | A pictogram with 15 fields in three colors (green, yellow, red). | In-depth assessment of the entire analytical process [3]. |

| ChlorTox | Quantitative | Chemical risk assessment by comparing substance hazard to a chloroform reference. | Total ChlorTox score; lower is better. | Evaluating and minimizing chemical toxicity risks in procedures [5]. |

These tools empower scientists to make informed decisions. For instance, a method for Flavokawain A using RP-HPLC with a methanol:water mobile phase was confirmed as environmentally sustainable with an AGREE score of 0.79 [6]. Similarly, a capillary zone electrophoresis (CZE) method for antibiotics was validated and its greenness confirmed using both the Analytical Eco-Scale and AGREE metrics [16].

Green Analytical Protocols for Impurity Assessment

This section provides detailed experimental protocols for impurity analysis, designed to meet both regulatory and greenness criteria.

Green RP-HPLC for Organic Impurity Profiling

This protocol is adapted from a validated method for Flavokawain A, demonstrating how traditional HPLC can be greened [6].

- Objective: To develop a simple, sensitive, and eco-friendly RP-HPLC method for the quantification of an active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) and its related organic impurities in bulk and tablet dosage forms.

- Experimental Workflow:

- Instrumentation: RP-HPLC system with PDA or UV-Vis detector.

- Chromatographic Conditions:

- Column: Shim-pack GIST C18 (150 × 4.6 mm, 3 µm) or equivalent.

- Mobile Phase: Methanol:Water (85:15, v/v). Note: Methanol is preferred over acetonitrile from a greenness perspective where separation efficiency allows.

- Flow Rate: 1.0 mL/min.

- Detection Wavelength: As per the analyte's UV spectrum.

- Injection Volume: 10-20 µL.

- Temperature: Ambient.

- Sample Preparation:

- Bulk Drug: Dissolve in the mobile phase to a concentration within the linear range (e.g., 2-12 µg/mL).

- Tablets: Weigh and powder tablets. Dissolve an equivalent amount of API in the mobile phase, sonicate, and filter.

- Validation Protocol (per ICH Q2(R1)): The method should be validated for:

- Linearity & Range: Prepare at least 5 concentrations in the working range. Demonstrate R² > 0.999 [6].

- Accuracy: Perform recovery studies at 3 levels (80%, 100%, 120%). Recovery should be 98-102% with %RSD < 2.0 [6].

- Precision: Assess repeatability (intra-day) and intermediate precision (inter-day, different analyst). %RSD for peak areas should be < 2.0%.

- Specificity: Demonstrate resolution from known impurities and degradation products formed under stress conditions (acid, base, oxidation, thermal, photolytic).

- Greenness Profile: This method scores highly due to its simple, aqueous-rich mobile phase, avoidance of toxic additives, and low waste generation per run.

Green Capillary Zone Electrophoresis (CZE) for Simultaneous Analysis

CZE is a powerful, inherently greener alternative to HPLC, as demonstrated for antibiotic analysis [16].

- Objective: To concurrently measure two APIs in a binary mixture or combined dosage form using an electro-driven separation method.

- Experimental Workflow:

- Instrumentation: Capillary Electrophoresis system with Diode Array Detector (DAD).

- Electrophoretic Conditions:

- Capillary: Uncoated fused silica, 50-60 cm total length, 50 µm internal diameter.

- Background Electrolyte (BGE): 100 mM Borate buffer, pH 10.2.

- Voltage: 30 kV.

- Injection: Hydrodynamic, 15-50 mbar for 15-60 seconds.

- Detection: DAD, wavelengths optimized for each analyte.

- Sample Preparation: Dissolve samples in water or a water-miscible solvent (e.g., methanol). Dilute to the working concentration range (e.g., 5-50 µg/mL) and filter.

- Validation Protocol (per ICH Q2(R2)): Validate for linearity, accuracy, precision, specificity, and robustness. The method showed correlation coefficients > 0.9999 and %RSD for precision below 1.86% [16].

- Greenness Profile: CZE is exceptionally green due to minute consumption of chemicals (nanoliters of buffer per run), primarily aqueous-based buffers, and minimal generation of hazardous organic waste [16].

Analysis of Elemental Impurities per ICH Q3D and USP <233>

The control strategy for elemental impurities relies heavily on modern spectroscopic techniques.

- Objective: To quantify elemental impurities (e.g., Cd, Pb, As, Hg, Co, Ni) in a drug product per ICH Q3D and USP <233>.

- Experimental Workflow:

- Instrumentation: Inductively Coupled Plasma-Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS).

- Analytical Procedure (per USP <233>):

- Sample Preparation: Accurately weigh the drug product. Perform direct digestion with concentrated nitric acid using a microwave digester, or use a closed-vessel digestion system. Cool, dilute to volume with high-purity water, and analyze alongside blanks and standards [17].

- Calibration: Use a series of multi-element standard solutions prepared in the same acid matrix as the samples.

- Validation: The procedure must meet the validation criteria for specificity, accuracy, precision, and limit of quantitation as outlined in USP <233> [17].

- Greenness Considerations: While ICP-MS itself is energy-intensive, its extreme sensitivity and multi-element capability in a single run make it highly efficient. Sample preparation can be greened by minimizing acid use and employing microwave digestion, which reduces reagent consumption and energy use compared to open-vessel hot-plate digestion.

The logical relationship and workflow for selecting and validating a green analytical method for impurity analysis is summarized in the following diagram:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table lists key reagents and materials used in the featured green analytical methods, with an emphasis on their function and green characteristics.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Green Impurity Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function in Analysis | Green Considerations & Alternatives |

|---|---|---|

| Methanol | Mobile phase component in HPLC. | Prefer over acetonitrile where possible; less toxic and more biodegradable. Still requires careful waste management [6]. |

| Water (HPLC Grade) | Primary solvent in mobile phases and samples. | The greenest solvent. Using higher proportions in mobile phases (e.g., 15% in [1]) improves greenness. |

| Borate Buffer | Background Electrolyte (BGE) in Capillary Electrophoresis. | Aqueous-based, resulting in minimal consumption and waste compared to organic HPLC mobile phases [16]. |

| Fused Silica Capillary | Separation channel in Capillary Electrophoresis. | Enables high-efficiency separations with only nanoliters of reagents, drastically reducing chemical use [16]. |

| Nitric Acid (High Purity) | Digesting agent for elemental impurity sample prep. | Highly corrosive and hazardous. Greenness is improved by using closed-vessel microwave digestion to minimize volume and vapor exposure. |

| Multi-element Standard Solutions | Calibration for ICP-MS/ICP-OES. | Allows for simultaneous quantification of multiple elements, reducing the number of required analytical runs and overall resource consumption. |

| Potassium Bromide (KBr) | Matrix for Diffuse Reflectance IR (DRIFTS) methods. | Used in solvent-free sample preparation for solid analysis, eliminating organic solvent waste [3]. |

The journey toward sustainable pharmaceutical development necessitates the integration of regulatory compliance with ecological responsibility. The ICH Q3A-Q3D and USP frameworks provide the non-negotiable foundation for ensuring drug safety through rigorous impurity control. By leveraging modern, greener analytical techniques like green RP-HPLC and capillary electrophoresis, and by systematically evaluating methods with tools like AGREE and the Analytical Eco-Scale, scientists can effectively reduce the environmental footprint of quality control laboratories. The future of pharmaceutical analysis lies in the continued harmonization of these two objectives—developing methods that are not only precise, accurate, and validated but also safe, sustainable, and economically viable, thereby fulfilling the industry's dual mandate of protecting patient health and planetary well-being.

The pharmaceutical industry is undergoing a paradigm shift, facing increasing pressure to adopt sustainable practices that minimize environmental impact while maintaining high analytical standards. Conventional analytical methods, particularly high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), are cornerstone techniques in pharmaceutical analysis but traditionally rely on large volumes of hazardous organic solvents, posing significant environmental and health risks [19]. The most consumed organic solvents in reversed-phase liquid chromatography, methanol and acetonitrile, are both hazardous and toxic, contributing to a substantial environmental footprint through waste generation [19]. This article examines core strategies—solvent reduction, waste minimization, and energy efficiency—that are transforming pharmaceutical analysis, providing a comparative assessment of established and emerging approaches to guide researchers and drug development professionals in implementing greener laboratory practices.

Solvent Reduction and Replacement Strategies

Green Solvent Alternatives

A fundamental strategy for greening pharmaceutical analysis involves replacing conventional solvents with safer, more sustainable alternatives. Green solvents are characterized by their low toxicity, biodegradability, and minimal environmental impact [20]. The table below compares the properties and applications of prominent green solvents with traditional options.

Table 1: Comparison of Conventional and Green Solvent Alternatives in Pharmaceutical Analysis

| Solvent | Category | Key Properties | Pharmaceutical Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetonitrile | Conventional | High elution strength, low UV cutoff | Primary organic modifier in RPLC | Toxic, hazardous, high environmental impact [19] |

| Methanol | Conventional | High elution strength | Primary organic modifier in RPLC | Toxic, hazardous [19] |

| Ethanol | Bio-based | Renewable, low toxicity, biodegradable | RPLC mobile phase modifier | Higher UV cutoff (~210 nm), higher viscosity [19] |

| Dimethyl Carbonate | Bio-based | Biodegradable, low toxicity | RPLC mobile phase | Limited elution strength [19] [20] |

| Ethyl Lactate | Bio-based | Renewable, biodegradable | Extraction processes, chromatography | Limited application data in pharmaceutical LC [19] |

| Supercritical CO₂ | Supercritical fluid | Non-toxic, non-flammable, tunable solubility | Supercritical Fluid Chromatography (SFC) | Requires specialized equipment [20] |

| Glycerol | Bio-based | Non-toxic, biodegradable | Aqueous mobile phase modifier | High viscosity leading to elevated backpressure [19] |

Ethanol stands out as a particularly promising alternative, being readily available, often cost-effective, and chromatographically competent for many applications where its higher UV cutoff (~210 nm) is acceptable [19]. Bio-based solvents like dimethyl carbonate and ethyl lactate offer advantages of biodegradability with low volatile organic compound (VOC) emissions [20]. Supercritical fluids, particularly supercritical CO₂, enable selective extraction of bioactive compounds with minimal environmental harm [20]. Despite these advances, limitations remain, including challenges with method development, separation efficiency, and detection compatibility, highlighting that solvent replacement requires careful consideration of analytical requirements [19].

Methodological and Technological Advances

Beyond direct solvent substitution, significant progress has been made in developing methodologies and technologies that inherently reduce solvent consumption.

Table 2: Methodological Approaches for Solvent Reduction

| Approach | Mechanism | Solvent Reduction Potential | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Miniaturization | Reduced column dimensions and particle sizes | Up to 90% compared to conventional HPLC | UHPLC, microfluidic chip columns [21] |

| Automated High-Throughput Screening | Parallel processing of multiple samples | Significant reduction in solvent per sample | Automated sample preparation systems [22] |

| Late-Stage Functionalization | Fewer synthetic steps in drug development | Reduces overall solvent use in discovery | Single-step modification of drug candidates [23] |

| Advanced Flow Management | Improved fluid handling efficiency | 40-70% reduction in LC systems | Efficient fluid handling in high-throughput LC [21] |

The transition to ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC) and microfluidic chip-based columns represents a particularly impactful advancement. These systems utilize reduced column dimensions and smaller particle sizes, enabling labs to process thousands of samples with high precision while consuming significantly less solvent [21]. One study demonstrated that downsizing from a conventional 4.6 mm ID column to a 2.1 mm ID column reduced solvent consumption by approximately 80% while maintaining analytical performance [19]. Instrument vendors are increasingly focusing on developing systems with reduced mobile phase usage as a key sustainability feature [21].

Waste Minimization Approaches

Pharmaceutical Waste Management and Circular Economy

Waste minimization in pharmaceutical analysis extends beyond the laboratory to encompass the entire drug lifecycle. Medication waste has considerable economic and environmental consequences, with studies indicating supplies and tablets constitute the highest wastage class of pharmaceuticals, with expiry being the major reason for wastage (92.05%) [24]. The overall pharmaceutical wastage rate in some healthcare systems has been reported at 3.68%, primarily due to expiry [24].

A circular economy approach presents a framework for addressing this challenge through waste-minimizing measures across the pharmaceutical supply chain:

- Manufacturers can contribute by extending medications' shelf-life, choosing sustainable storage conditions, and adjusting package sizes [25].

- Distributors play a role through stock management optimization and loosening shelf-life policies [25].

- Prescribers can commit to rational prescribing practices, including consideration of prescription quantities and shorter durations [25].

- Pharmacists contribute via appropriate stock management, enhancing medication preparation processes, and redispensing unused medication [25].

These strategies emphasize that preventing leftover medication through the entire pharmaceutical chain is essential for achieving sustainable supply and use of medication [25].

Laboratory Waste Reduction Protocols

Within analytical laboratories, waste reduction requires systematic approaches to chemical management and process optimization. The following experimental protocol outlines a comprehensive strategy for waste minimization in chromatographic methods:

- Waste Segregation: Implement strict segregation of hazardous and non-hazardous waste streams to minimize the volume requiring specialized treatment [26].

- Solvent Recycling: Establish procedures for distillation and reuse of organic solvents where analytical requirements permit.

- Method Optimization: Employ Quality by Design (QbD) principles and Design of Experiments (DoE) to develop methods with minimal waste generation [27].

- Inventory Management: Maintain just-in-time chemical inventory to reduce disposal of expired reagents [25].

- Waste Tracking: Implement detailed documentation of waste generation, treatment, and disposal to identify improvement opportunities [26].

Regulatory guidelines are increasingly emphasizing proper waste management, with 2025 regulations expected to enforce stricter requirements for hazardous pharmaceutical waste, including specialized disposal methods to prevent environmental contamination [26].

Figure 1: Laboratory Waste Management Hierarchy. This workflow outlines a systematic approach to waste handling prioritizing segregation, recycling, and proper treatment.

Energy Efficiency in Analytical Processes

Energy-Conscious Method Development

Energy efficiency represents the third pillar of sustainable pharmaceutical analysis, with significant opportunities for optimization in analytical processes. The primary strategies for reducing energy consumption include:

- Method Acceleration: Applying assisted fields such as ultrasound and microwaves to enhance extraction efficiency and speed up mass transfer while consuming significantly less energy compared to traditional heating methods like Soxhlet extraction [22].

- Parallel Processing: Handling multiple samples simultaneously increases overall throughput and reduces energy consumed per sample [22].

- Process Automation: Automated systems save time, lower consumption of reagents and solvents, and reduce waste generation while minimizing human intervention [22].

- Process Integration: Streamlining multi-step preparation procedures into single, continuous workflows simplifies operations while cutting down on resource use and energy consumption [22].

- Temperature Optimization: Running chromatographic separations at ambient temperature rather than with heated columns where analytically feasible.

Instrument manufacturers are increasingly prioritizing reduced power consumption as a key product development criterion, responding to laboratory demands for lower operational costs and improved sustainability profiles [21].

Green Sample Preparation Framework

The Green Sample Preparation (GSP) framework provides a systematic approach for reducing energy consumption in analytical workflows:

Figure 2: Green Sample Preparation Framework. This illustrates the transition from traditional methods to energy-efficient approaches through four primary strategies.

The miniaturization of chemical reactions represents a particularly innovative approach to energy reduction. In collaboration with Stockholm University, AstraZeneca has developed methods using as little as 1mg of starting material to perform thousands of reactions, allowing several thousand times more reactions compared to standard techniques with the same amount of material [23]. This approach dramatically reduces energy requirements per data point while enabling exploration of a much larger range of drug-like molecules.

Greenness Assessment and Validation

Greenness Assessment Tools

The movement toward sustainable analytical practices has necessitated the development of standardized metrics to evaluate and validate the environmental friendliness of analytical methods. Multiple assessment tools have been established, each with distinct evaluation criteria:

Table 3: Comparison of Greenness Assessment Methods for Pharmaceutical Analysis

| Assessment Tool | Type | Key Evaluation Parameters | Scoring System | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEMI | Qualitative | PBT substances, hazardous chemicals, corrosivity, waste generation | 4-quadrant pictogram (green/blank) | Preliminary screening of methods [5] |

| Analytical Eco-Scale | Semi-quantitative | Reagent hazards, energy consumption, waste | 100-point scale (≥75 = excellent) | Method 5 for paclitaxel scored 90 [5] |

| AGREE | Quantitative | Comprehensive 12 GAC principles | 0-1 scale (closer to 1 = greener) | HPLC method for antihypertensives [27] |

| White Analytical Chemistry (WAC) | Comprehensive | Analytical, ecological, and practical efficiency | RGB model (whiteness index) | Balanced sustainability assessment [5] |

| ChlorTox | Toxicity-focused | Chemical risk relative to chloroform | Numerical score (lower = better) | Toxicity comparison of methods [5] |

These tools enable objective comparison of method greenness and identify opportunities for improvement. For example, in a study evaluating HPLC methods for paclitaxel quantification, methods 3 and 5 demonstrated superior greenness profiles, with method 5 achieving a score of 90 on the Analytical Eco-Scale, reflecting high eco-friendliness, minimal waste, and operational efficiency [5]. In contrast, methods 6, 8, and 9 required optimization in hazardous material usage, energy consumption, and waste management [5].

Implementation Framework for Sustainable Practices

Successfully implementing green analytical chemistry principles requires a structured framework encompassing methodology, technology, and operational practices:

- Methodology Optimization: Replace hazardous solvents with green alternatives like ethanol or dimethyl carbonate; apply QbD and DoE for method optimization; minimize sample preparation steps [27].

- Technology Adoption: Transition to UHPLC and microfluidic systems; implement automation for precision and waste reduction; utilize software tools for solvent selection [21] [27].

- Operational Practices: Establish chemical management systems; implement waste segregation and recycling protocols; train personnel on green chemistry principles [26] [25].

A critical consideration in implementation is the "rebound effect," where efficiency gains lead to increased consumption, potentially offsetting environmental benefits [22]. For example, a novel, low-cost microextraction method might lead laboratories to perform significantly more extractions, increasing total chemical use and waste generation [22]. Mitigation strategies include optimizing testing protocols, using predictive analytics, and fostering a mindful laboratory culture.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Green Pharmaceutical Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Green Attributes | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethanol | Mobile phase modifier | Renewable, low toxicity, biodegradable | UV cutoff ~210 nm; higher viscosity than ACN/MeOH [19] |

| Dimethyl Carbonate | Mobile phase component | Biodegradable, low toxicity | Limited elution strength; useful for certain separations [19] [20] |

| Ethyl Lactate | Extraction solvent | Renewable, biodegradable | Particularly useful in natural product extraction [20] |

| Supercritical CO₂ | Extraction & chromatography medium | Non-toxic, non-flammable, recyclable | Requires specialized equipment; excellent for non-polar compounds [20] |

| Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) | Extraction & synthesis media | Tunable properties, often bio-based | Emerging technology with promising applications [20] |

| Water | Mobile phase component | Non-toxic, non-flammable | Ideal green solvent but limited by chromatographic principles [19] |

| Formic Acid (dilute) | Mobile phase pH modifier | Lower toxicity than alternatives | Used in minimal concentrations (e.g., 0.1%) [27] |

The transition to sustainable pharmaceutical analysis represents both an environmental imperative and an opportunity for enhanced operational efficiency. Core strategies of solvent reduction, waste minimization, and energy efficiency, when implemented through the frameworks and methodologies outlined in this article, offer a pathway to significantly reduce the environmental footprint of pharmaceutical analysis while maintaining rigorous analytical standards. The availability of comprehensive greenness assessment tools enables objective evaluation of progress and identification of improvement areas. As regulatory focus on environmental impact intensifies and technological innovations continue to emerge, the adoption of these core strategies will increasingly define best practices in pharmaceutical analysis, balancing analytical excellence with environmental responsibility.

Implementing Green Analytical Techniques in Pharmaceutical Workflows

The field of pharmaceutical analysis is undergoing a significant transformation driven by global sustainability initiatives and the growing need to reduce the environmental footprint of laboratory operations. Conventional chromatographic techniques, while delivering high analytical performance, often rely heavily on hazardous organic solvents, generate substantial waste, and consume considerable energy [28]. Green chromatography has emerged as a strategic response to these challenges, seeking to align analytical methodologies with the principles of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) without compromising the accuracy, precision, and reliability required for pharmaceutical quality control and research [29] [28]. This guide provides a comprehensive objective comparison of two pivotal green chromatographic techniques—Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (UHPLC) and Supercritical Fluid Chromatography (SFC)—and details the experimental strategies for replacing traditional solvents with greener alternatives, all framed within the context of modern greenness validation methods.

Technical Comparison of UHPLC and SFC

Core Principles and Operational Mechanisms

Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (UHPLC) represents an evolution of traditional HPLC, achieving superior performance through the use of stationary phases with very small particle sizes (often sub-2 µm) and instrumentation capable of operating at significantly higher pressures (exceeding 15,000 psi). The fundamental advancement is explained by the van Deemter equation, which describes the relationship between linear velocity and plate height. UHPLC, particularly when using superficially porous particles (SPPs), minimizes the eddy diffusion (A-term) and mass transfer (C-term) contributions, resulting in a flatter curve [30]. This allows for high-efficiency separations using shorter columns and higher flow rates without a substantial loss in resolution, directly translating to faster run times and reduced solvent consumption [30].

Supercritical Fluid Chromatography (SFC) primarily utilizes supercritical carbon dioxide (scCO₂) as the main component of the mobile phase. Supercritical fluids exhibit properties intermediate between gases and liquids, such as low viscosity and high diffusivity, which facilitate rapid mass transfer and highly efficient separations [29]. The technique is particularly well-suited for chiral separations and the analysis of non-polar to moderately polar compounds. The environmental benefit is profound, as scCO₂ is non-toxic, non-flammable, and largely replaces hazardous organic solvents. Modifiers like methanol or ethanol are often added in small quantities to enhance the elution strength for more polar analytes [29] [31].

Comparative Performance and Environmental Metrics

The following table summarizes a direct, data-driven comparison between UHPLC and SFC based on key performance and greenness parameters.

Table 1: Technical and Environmental Comparison of UHPLC and SFC

| Parameter | UHPLC | SFC |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Mobile Phase | Water/Organic solvent mixtures (e.g., Acetonitrile, Methanol) [31] | Primarily supercritical CO₂ with organic modifiers (e.g., 5-40% Methanol) [29] [31] |

| Primary Green Advantage | Reduces solvent consumption by 50-90% via shorter columns, smaller diameters, and faster runs [30] [31] | Replaces 50-90% of organic solvents with non-toxic, recyclable CO₂ [29] |

| Analysis Speed | Very high; run times can be 3-5 times faster than HPLC [30] | High; faster than HPLC due to low viscosity and high diffusivity of scCO₂ [29] |

| Sample Throughput | High, enabled by fast gradients and rapid re-equilibration [7] | High, particularly for chiral separations and natural products [29] |

| Operational Pressure | Very high (≥ 1000 bar) [30] | Moderate (typically 150-300 bar) [29] |

| Optimal Application Scope | Broad, including polar pharmaceuticals, biomarkers, trace contaminants in water [7] | Non-polar to moderately polar compounds, chiral molecules, natural products [29] [31] |

| Inherent Waste Generation | Low (reduced solvent volume) but requires management of organic waste [28] | Very low; primary waste is modifier and collected CO₂, which can be vented or recycled [29] |

| Limitations | Higher cost and maintenance; potential for column clogging; higher backpressure with viscous solvents [30] | Less ideal for highly polar compounds; requires specialized equipment; modifier disposal needed [29] [31] |

Greenness Assessment and Validation Frameworks

Evaluating the environmental profile of an analytical method is crucial for justifying its classification as "green." Several standardized metrics have been developed to provide quantitative and qualitative assessments.

Table 2: Greenness Assessment Tools for Chromatographic Methods

| Assessment Tool | Type of Output | Key Evaluation Criteria | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| AGREE (Analytical GREEnness) | A unified score (0-1) and a radial pictogram [28] [13] | All 12 principles of GAC, including energy consumption, waste, and toxicity [28]. | A validated UHPLC-MS/MS method for trace pharmaceuticals achieved a high score, underscoring its sustainability [7]. |

| GAPI (Green Analytical Procedure Index) | A color-coded pictogram for the entire workflow [28] [13] | Sample collection, preparation, transportation, and final analysis [5]. | Used to distinguish between high- and low-impact HPLC methods for paclitaxel analysis [28] [5]. |

| Analytical Eco-Scale | A numerical score (100 = ideal) [5] | Penalty points for hazardous chemicals, energy use, and waste [5]. | A green RP-HPLC method for Flavokawain A was validated and scored, with ≥75 considered excellent [6]. |

| NEMI (National Environmental Methods Index) | A simple pictogram with four quadrants [13] [5] | PBT chemicals, hazardous waste, corrosivity, and waste amount [5]. | Applied in a case study to rank the greenness of various HPLC methods for paclitaxel [5]. |

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision-making process for selecting and validating a green chromatographic method, incorporating the principles of White Analytical Chemistry (WAC) which balances environmental sustainability (Green) with analytical performance (Red) and practical applicability (Blue) [5].

Diagram 1: Green Method Selection & Validation Workflow

Experimental Protocols for Solvent Replacement

Strategy 1: Replacement with Carbonate Esters

A joint study from the University of Lyon and the University of Texas at Arlington provides a robust protocol for replacing acetonitrile with carbonate esters like dimethyl carbonate (DMC), diethyl carbonate (DEC), and propylene carbonate (PC) in RPLC, HILIC, and NPLC modes [30].

Detailed Methodology:

- Ternary Phase Diagram Mapping: Before method development, construct ternary phase diagrams for the carbonate ester/water/co-solvent system. The co-solvent (e.g., methanol, ethanol, or acetonitrile) is essential to maintain a single-phase mobile phase throughout the analysis, as carbonate esters are only partially miscible with water [30].

- Mobile Phase Preparation: Select a composition from the single-phase region of the ternary diagram. For example, a typical RPLC mobile phase might consist of a carbonate ester, water, and a small percentage of methanol to ensure miscibility [30].

- Chromatographic Evaluation: Assess the new mobile phase for retention factors, selectivity, and efficiency. Note that carbonate esters like PC have a higher UV cut-off, which may necessitate using a higher detection wavelength or alternative detection strategies to maintain sensitivity [30].

- Viscosity and Pressure Monitoring: Monitor backpressure closely, as solvents like PC have higher viscosity (~2.5 cP) compared to acetonitrile (~0.37 cP), which can lead to increased system pressure [30].

Strategy 2: Employing Green Solvent Mixtures

For UHPLC, a common and effective strategy involves using ethanol-water or methanol-water mixtures as direct replacements for acetonitrile-water mobile phases [31]. Ethanol, in particular, is a favored green solvent due to its low toxicity and renewable origin.

Detailed Methodology:

- System Re-equilibration: Allow for a longer system re-equilibration time when switching to ethanol-based mobile phases due to their higher viscosity and potential for different wetting properties on the stationary phase.

- Gradient Adjustment: Re-optimize gradient elution programs, as the elution strength of ethanol differs from acetonitrile. Isocratic scouting runs can help determine the correct gradient profile.

- Pressure Management: Be aware of the increased backpressure resulting from higher viscosity solvents. This can be partially mitigated by using UHPLC systems designed for high-pressure operation and by elevating the column temperature to reduce mobile phase viscosity [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Green Chromatography

| Item | Function/Description | Green Attribute |

|---|---|---|

| Supercritical CO₂ | Primary mobile phase for SFC; provides the foundation for rapid, high-efficiency separations. | Non-toxic, non-flammable, recyclable, and sourced from existing industrial processes [29]. |

| Carbonate Esters (DMC, DEC, PC) | Direct replacements for acetonitrile in reversed-phase and other LC modes. | Lower toxicity and better biodegradability profile compared to traditional solvents like acetonitrile [30]. |