Green Chemistry: The Anastas-Warner Principles and Their Transformative Role in Sustainable Drug Development

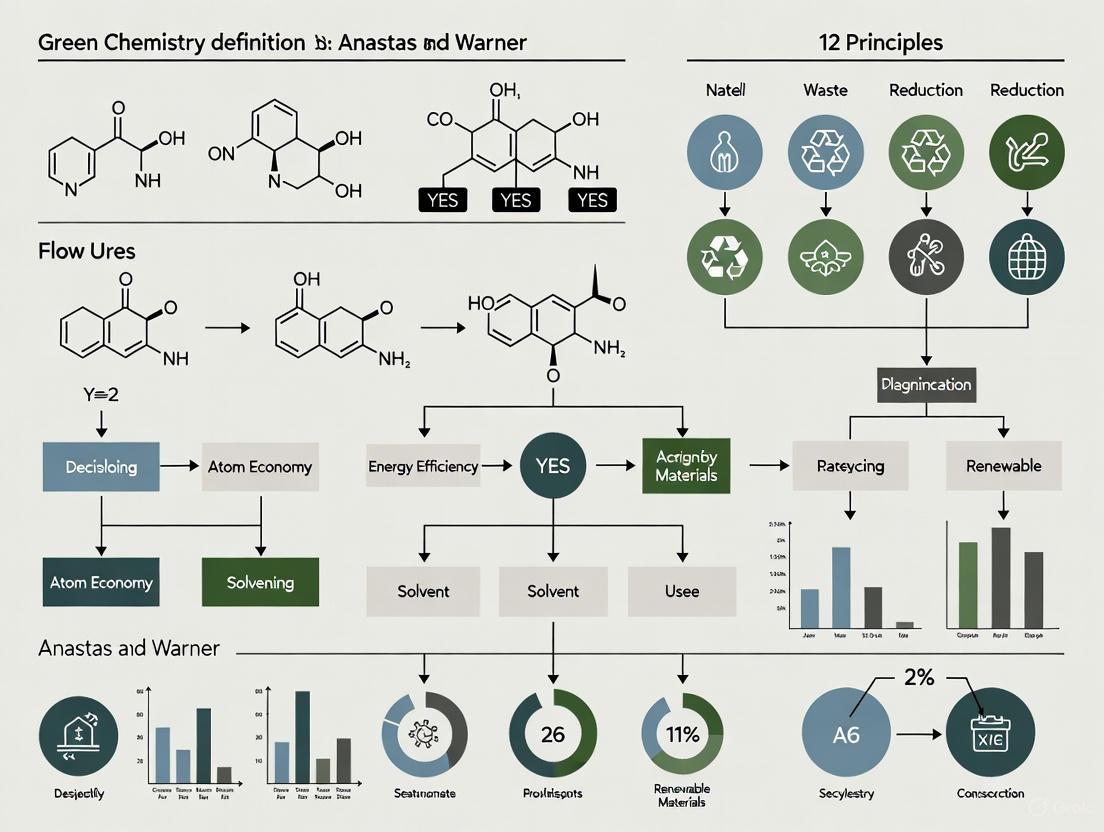

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of green chemistry, defined by Paul Anastas and John Warner as the design of chemical products and processes that reduce or eliminate hazardous substances.

Green Chemistry: The Anastas-Warner Principles and Their Transformative Role in Sustainable Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of green chemistry, defined by Paul Anastas and John Warner as the design of chemical products and processes that reduce or eliminate hazardous substances. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it delves into the foundational 12 principles, showcases their practical application in pharmaceutical synthesis through advanced methodologies like catalysis and AI, analyzes implementation challenges and optimization strategies, and validates the approach with industry case studies and quantitative metrics. The synthesis of these perspectives underscores green chemistry as a strategic imperative for developing effective medicines while minimizing environmental impact and advancing sustainability goals in biomedical research.

The Foundations of Green Chemistry: Understanding the Anastas-Warner Principles and Their Historical Context

Green chemistry represents a fundamental paradigm shift in the chemical sciences, moving from a traditional focus on chemical output to a proactive approach that designs environmental and safety considerations into the very fabric of chemical products and processes. Formally defined as "the design of chemical products and processes that reduce or eliminate the use or generation of hazardous substances" [1], this philosophy applies across the entire life cycle of a chemical product, including its design, manufacture, use, and ultimate disposal [2]. Unlike remediation or pollution cleanup efforts, which address contamination after it has occurred, green chemistry seeks to prevent pollution at the molecular level [2]. This preemptive approach stands in stark contrast to traditional environmental chemistry, which typically studies the effects and behaviors of pollutants already in the environment [3].

The field emerged from foundational work in the 1990s by Paul Anastas, often called the "father of green chemistry," who formally established the term and foundational principles while working at the United States Environmental Protection Agency [3]. Together with John C. Warner, Anastas developed the Twelve Principles of Green Chemistry that continue to serve as the definitive framework for the field [1] [3]. This molecular-level approach to sustainability has evolved from a theoretical concept to an essential driver of innovation across pharmaceuticals, materials science, and industrial manufacturing, creating technologies that are inherently safer and more efficient while maintaining economic viability [4].

Theoretical Foundations: The Twelve Principles

The Twelve Principles of Green Chemistry established by Anastas and Warner provide a comprehensive framework for designing safer chemical processes and products [1]. These principles emphasize proactive design rather than end-of-pipe solutions and have become the cornerstone of modern sustainable chemistry practices across academia and industry [5]. The principles guide researchers in minimizing the environmental footprint of chemical activities while maintaining efficiency and economic viability [2] [1].

Table 1: The Twelve Principles of Green Chemistry

| Principle Number | Principle Name | Core Concept |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Prevention | Preventing waste generation is superior to treating or cleaning up waste after it is formed [1]. |

| 2 | Atom Economy | Synthetic methods should maximize incorporation of all materials used into the final product [1]. |

| 3 | Less Hazardous Chemical Syntheses | Synthetic methods should use and generate substances with minimal toxicity to human health and the environment [1]. |

| 4 | Designing Safer Chemicals | Chemical products should be designed to preserve efficacy while reducing toxicity [1]. |

| 5 | Safer Solvents and Auxiliaries | The use of auxiliary substances should be unnecessary when possible and innocuous when used [1]. |

| 6 | Design for Energy Efficiency | Energy requirements should be minimized, with reactions conducted at ambient temperature and pressure when possible [1]. |

| 7 | Use of Renewable Feedstocks | Raw materials should be renewable rather than depleting whenever practicable [1]. |

| 8 | Reduce Derivatives | Unnecessary derivatization should be minimized because it requires additional reagents and can generate waste [1]. |

| 9 | Catalysis | Catalytic reagents are superior to stoichiometric reagents [1]. |

| 10 | Design for Degradation | Chemical products should be designed to break down into innocuous degradation products after use [1]. |

| 11 | Real-time Analysis for Pollution Prevention | Analytical methodologies need to be developed for real-time, in-process monitoring before hazardous substances form [1]. |

| 12 | Inherently Safer Chemistry for Accident Prevention | Substances should be chosen to minimize potential for chemical accidents, including releases, explosions, and fires [1]. |

These principles operate synergistically rather than in isolation, creating a holistic design framework that addresses multiple aspects of sustainability simultaneously. For example, the use of catalysis (Principle 9) frequently enables safer syntheses (Principle 3) with improved energy efficiency (Principle 6) [5]. The principles can be conceptually divided into several key focus areas, as visualized below.

This conceptual framework illustrates how the twelve principles collectively address four fundamental objectives: preventing waste before it's created, optimizing efficiency in chemical processes, reducing risks throughout the product lifecycle, and promoting sustainable resource use [2] [1] [5]. The principles provide a systematic approach to incorporating sustainability at the molecular design stage, fundamentally differentiating green chemistry from traditional pollution control strategies.

Current Research and Methodological Advances

The application of green chemistry principles has led to significant technological innovations across multiple domains. Current research focuses on developing alternative materials, improving synthetic efficiency, and replacing hazardous substances with safer alternatives, demonstrating the practical implementation of Anastas and Warner's foundational framework [6].

Advanced Materials Development

Earth-Abundant Permanent Magnets

Traditional permanent magnets used in consumer electronics, electric vehicle motors, and wind turbines rely heavily on rare earth elements, which are geographically concentrated (approximately 80% sourced from China), expensive, and environmentally damaging to extract [6]. Green chemistry approaches are developing high-performance alternatives using abundant elements like iron and nickel [6]. Notable breakthroughs include:

- Iron Nitride (FeN): Engineered compounds offering competitive magnetic properties without environmental and geopolitical costs [6].

- Tetrataenite (FeNi): A powerful magnet naturally found in meteorites that normally requires millions of years to form. Researchers have dramatically accelerated this process by adding phosphorus to an iron-nickel alloy, creating the material in seconds rather than geological timescales [6].

These alternatives provide viable pathways for more sustainable manufacturing across multiple industries, including transportation, renewable energy, and healthcare equipment [6].

PFAS-Free Alternatives

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are persistent, bioaccumulative chemicals facing increasing regulatory scrutiny due to environmental and health risks [6]. Green chemistry innovations are replacing PFAS in manufacturing processes through:

- Bio-based surfactants like rhamnolipids and sophorolipids [6]

- Fluorine-free coatings made from silicones, waxes, or nanocellulose [6]

- Alternative process treatments including plasma treatments and supercritical CO₂ cleaning [6]

These replacements reduce potential liability and cleanup costs while enabling safer, more compliant production of textiles, cosmetics, cookware, and food packaging [6].

Innovative Synthesis Techniques

Mechanochemistry

Mechanochemistry utilizes mechanical energy—typically through grinding or ball milling—to drive chemical reactions without solvents [6]. This approach offers significant sustainability advantages:

- Eliminates solvent waste, which often accounts for a substantial portion of environmental impacts in pharmaceutical and fine chemical production [6]

- Enables reactions with low-solubility reactants or compounds unstable in solution [6]

- Provides high yields with reduced energy consumption [6]

Research applications include synthesizing solvent-free imidazole-dicarboxylic acid salts for fuel cell electrolytes and developing pharmaceutical compounds through solvent-free pathways [6]. Industrial-scale mechanochemical reactors are anticipated for pharmaceutical and materials production in coming years [6].

Aqueous Reaction Systems

Traditional organic solvents contribute significantly to hazardous waste, air pollution, and safety risks in chemical manufacturing [6]. Green chemistry advances demonstrate that many reactions can be achieved in-water or on-water, leveraging water's unique properties (hydrogen bonding, polarity, surface tension) to facilitate chemical transformations [6]. Notable developments include:

- Silver nanoparticle synthesis in water using electron strike techniques [6]

- Accelerated Diels-Alder reactions in aqueous environments [6]

- New catalysts optimized specifically for aqueous environments [6]

These water-based systems reduce production costs, minimize toxic solvent use, and can expand access to chemical synthesis in low-resource settings and educational institutions [6].

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Green Synthesis Methods

| Synthesis Method | Key Advantages | Atom Economy | Energy Efficiency | Solvent Usage | Current TRL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanochemistry | Solvent-free, versatile for insoluble compounds | High | High | None | 4-6 (Lab to Pilot) |

| Aqueous Systems | Non-toxic, non-flammable, low-cost | Medium | Medium | Water only | 5-7 (Pilot to Production) |

| Deep Eutectic Solvents | Biodegradable, low-toxicity, customizable | High | Medium-High | Green solvents | 3-5 (Lab to Pilot) |

| Continuous Flow | Improved safety, better heat transfer | High | High | Reduced volume | 6-8 (Production Scale) |

Computational and Analytical Approaches

Artificial Intelligence in Reaction Optimization

Artificial intelligence is transforming green chemistry research by enabling predictive modeling of reaction outcomes, catalyst performance, and environmental impacts [6]. AI systems are being trained to evaluate reactions based on sustainability metrics like atom economy, energy efficiency, toxicity, and waste generation [6]. Specific applications include:

- Predicting catalyst behavior without physical testing, reducing waste and hazardous chemical use [6]

- Designing catalysts for greener ammonia production and fuel cell optimization [6]

- Creating autonomous optimization loops integrating high-throughput experimentation with machine learning [6]

- Developing AI-guided retrosynthesis tools that prioritize environmental impact alongside performance [6]

As regulatory and ESG pressures grow, these predictive models support sustainable product development across pharmaceuticals and materials science [6]. The maturation of these tools is expected to lead to standardized sustainability scoring systems for chemical reactions [6].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Mechanochemical Synthesis: Solvent-Free Imidazole-Dicarboxylic Acid Salts

This protocol describes the mechanochemical synthesis of anhydrous organic salts for potential applications as pure organic proton-conducting electrolytes in fuel cells, demonstrating Principles 1 (Prevention), 5 (Safer Solvents), and 6 (Energy Efficiency) [6].

Materials and Equipment:

- High-energy ball mill with grinding jars and balls

- Imidazole precursors (commercially available)

- Dicarboxylic acids (commercially available)

- Inert atmosphere glove box (for moisture-sensitive reactions)

- Analytical balance (±0.1 mg precision)

Experimental Procedure:

- Preparation: Weigh stoichiometric ratios of imidazole precursors and dicarboxylic acids using an analytical balance in an inert atmosphere if moisture-sensitive.

- Loading: Transfer the solid reactants into the grinding jar with grinding balls. The ball-to-powder mass ratio should be maintained between 10:1 and 20:1 for optimal energy transfer.

- Reaction Execution: Securely close the grinding jar and place it in the ball mill. Process the mixture at a frequency of 20-30 Hz for 30-90 minutes, depending on the specific reactants.

- Monitoring: Monitor reaction progress by periodically collecting small aliquots for FT-IR or XRD analysis to track the disappearance of reactant peaks and emergence of product signatures.

- Product Recovery: After completion, open the jar and collect the solid product. Minimal purification is typically required due to high conversion rates and absence of solvent.

Key Advantages:

- Eliminates solvent waste generation

- Achieves high yields (>85%) with minimal energy input

- Reduces reaction times compared to solution-based methods

- Requires no purification steps in many cases

Deep Eutectic Solvent-Mediated Metal Extraction

This methodology utilizes deep eutectic solvents (DES) for sustainable extraction of critical metals from electronic waste, aligning with Principles 7 (Renewable Feedstocks) and 10 (Design for Degradation) while supporting circular economy objectives [6].

DES Formulation Preparation:

- Component Selection:

- Hydrogen Bond Acceptor (HBA): Choline chloride

- Hydrogen Bond Donor (HBD): Renewable compounds like urea, glycols, carboxylic acids, or sugars

- Mixing: Combine HBA and HBD in typical molar ratios of 1:2 or 1:3 (HBA:HBD)

- Heating: Heat the mixture at 80-100°C with continuous stirring until a homogeneous, clear liquid forms

Metal Extraction Protocol:

- Feedstock Preparation: Communtize e-waste (e.g., printed circuit boards) to particle size of 100-500 μm to increase surface area.

- Extraction: Combine DES and e-waste feedstock in a 10:1 mass ratio in a reaction vessel. Heat to 120-150°C with agitation for 2-4 hours.

- Separation: Separate the metal-containing DES phase from the residual solids via filtration or centrifugation.

- Metal Recovery: Recover target metals (gold, lithium, rare earths) from the DES through electrodeposition, precipitation, or other standard methods.

- Solvent Reuse: Regenerate and reuse the DES for multiple extraction cycles.

Performance Metrics:

- Extraction efficiency: 85-95% for precious metals

- DES biodegradability: >70% within 28 days

- Solvent reuse potential: 5-8 cycles without significant efficiency loss

The experimental workflow below illustrates the comprehensive process for solvent-free synthesis and metal recovery using green chemistry principles.

The Research Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Implementation of green chemistry principles requires specialized reagents and materials that enable sustainable synthesis pathways. The following toolkit details essential solutions for conducting green chemistry research, particularly focusing on solvent alternatives, catalysts, and renewable feedstocks.

Table 3: Essential Green Chemistry Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Green Advantages | Example Uses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) | Customizable, biodegradable solvents for extraction | Low toxicity, biodegradable, often from renewable sources | Metal recovery from e-waste, biomass processing [6] |

| Water as Reaction Medium | Solvent for in-water and on-water reactions | Non-toxic, non-flammable, inexpensive, readily available | Nanoparticle synthesis, Diels-Alder reactions [6] |

| Heterogeneous Catalysts | Reusable catalytic systems | Recyclable, minimal metal leaching, high stability | Continuous flow systems, industrial-scale synthesis [5] |

| Bio-Based Surfactants | Replacement for PFAS-based surfactants | Renewable feedstocks, biodegradable, low toxicity | Textile processing, cosmetics, cleaning products [6] |

| Renewable Feedstocks | Plant-based raw materials | Carbon neutral, reduced fossil fuel dependence | Bio-plastics, polymer synthesis [5] [3] |

| Mechanochemical Reactors | Solvent-free reaction systems | Eliminate solvent waste, high energy efficiency | Pharmaceutical synthesis, materials production [6] |

Green chemistry represents a transformative approach to chemical design that aligns technological advancement with environmental sustainability. The field has evolved from a theoretical framework established by Anastas and Warner to a practical innovation driver across multiple industries [6] [4] [3]. The continuing adoption of green chemistry principles promises to reshape chemical manufacturing, product design, and waste management practices worldwide.

Future advancements will likely focus on several key areas: scaling laboratory innovations to industrial production, developing standardized sustainability metrics, integrating artificial intelligence for reaction optimization, and creating circular systems where waste streams become feedstocks for new processes [6] [5]. The ongoing integration of green chemistry into academic curricula and corporate research initiatives ensures that these sustainable design principles will continue to drive innovation while addressing pressing global environmental challenges [7] [4]. As regulatory pressures increase and consumer preferences shift toward sustainable products, green chemistry provides the fundamental scientific framework for developing next-generation materials and processes that protect human health and the environment without sacrificing economic viability or technological progress [6] [5].

The conceptual framework of green chemistry represents a fundamental paradigm shift in the chemical sciences, moving industrial and academic practice from a tradition of pollution control toward an inherent philosophy of pollution prevention [8]. This transformative approach did not emerge in a vacuum but was catalyzed by a series of historical developments that exposed the profound environmental and health consequences of conventional chemical processes. The formalization of this field in the 1990s through the work of Paul Anastas and John Warner provided a systematic foundation—the 12 Principles of Green Chemistry—that has since guided researchers, industries, and policymakers toward more sustainable chemical practices [1] [9]. This evolution from environmental consciousness to structured scientific principles represents a critical trajectory in modern chemistry, establishing a framework that aligns chemical innovation with ecological and human health considerations. The enduring relevance of this framework is particularly significant for drug development professionals and researchers who face increasing pressure to develop synthetic pathways that minimize environmental impact while maintaining efficacy and economic viability.

Historical Foundations: From Environmental Awareness to Chemical Philosophy

The Silent Spring Catalyst

The publication of Rachel Carson's Silent Spring in 1962 served as the seminal catalyst for the modern environmental movement and fundamentally altered public and scientific perception of chemical technologies. Carson, a marine biologist and science writer, meticulously documented the environmental harm caused by the indiscriminate use of synthetic pesticides, particularly DDT [10] [11]. Her work compellingly argued that these chemicals should more accurately be termed "biocides" due to their broad destructive capacity beyond target pests, affecting ecosystems, wildlife, and potentially human health [10]. Carson's critique extended beyond the chemicals themselves to challenge the societal acceptance of technological progress without adequate consideration of long-term consequences, questioning the prevailing paradigm of human dominion over nature [11].

The impact of Silent Spring was immediate and profound. While the chemical industry mounted significant opposition, Carson's evidence ultimately prompted a presidential investigation under John F. Kennedy that validated her concerns [11]. This led to substantive policy changes, including the banning of DDT for agricultural uses in the United States in 1972, and inspired the creation of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 1970 [12] [11]. The book's legacy established a crucial precedent: that scientific evidence, when effectively communicated to the public, could precipitate substantial regulatory and ideological shifts regarding humanity's relationship with the natural world.

The Regulatory and Conceptual Evolution

The decades following Silent Spring witnessed a gradual transition from reactive environmental regulation to proactive prevention strategies, setting the stage for green chemistry's formal emergence:

1970s: Regulatory Foundations - The establishment of the EPA marked the beginning of formalized environmental governance in the United States. Initial approaches focused primarily on pollution control through legislation such as the Safe Drinking Water Act (1974) and the management of toxic waste sites, exemplified by the Love Canal scandal [12].

1980s: Preventative Shifting - A significant paradigm shift began as scientists and regulators recognized the limitations of end-of-pipe solutions. International bodies like the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) initiated conversations about preventative strategies [12]. The establishment of the Office of Pollution Prevention and Toxics within the EPA in 1988 institutionalized this evolving perspective [12].

Early 1990s: Conceptual Crystallization - The Pollution Prevention Act of 1990 formally established prevention as the preferred national strategy for environmental protection [12]. During this period, staff at the EPA's Office of Pollution Prevention and Toxics coined the term "Green Chemistry," capturing an emerging philosophy that would soon be systematically defined [12] [9].

The diagram below visualizes this historical progression from raised awareness to the formal establishment of green chemistry as a scientific discipline:

Historical Evolution Toward Green Chemistry

The Anastas-Warner Framework: Formalizing Green Chemistry

The Twelve Principles of Green Chemistry

In 1998, Paul Anastas and John C. Warner published Green Chemistry: Theory and Practice, formally systematizing the philosophy of green chemistry into twelve foundational principles [1] [9]. These principles provide a comprehensive framework for designing chemical products and processes that minimize environmental impact and reduce potential hazards. The table below summarizes these principles and their core objectives:

Table 1: The Twelve Principles of Green Chemistry

| Principle Number | Principle Name | Core Objective | Key Application in Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Prevention | Prevent waste rather than treating or cleaning up after formation [1] | Design synthetic pathways that minimize by-products |

| 2 | Atom Economy | Maximize incorporation of all materials into final product [1] | Develop reactions with high atom efficiency (e.g., Diels-Alder) |

| 3 | Less Hazardous Synthesis | Design synthetic methods using/generating non-toxic substances [1] | Replace hazardous reagents with safer alternatives |

| 4 | Designing Safer Chemicals | Design products for efficacy while reducing toxicity [1] | Structure-activity relationship analysis for toxicity |

| 5 | Safer Solvents/Auxiliaries | Eliminate or use innocuous auxiliary substances [1] | Utilize water or ionic liquids instead of organic solvents |

| 6 | Energy Efficiency | Minimize energy requirements of processes [1] | Conduct reactions at ambient temperature/pressure |

| 7 | Renewable Feedstocks | Use renewable rather than depleting feedstocks [1] | Biomass-derived compounds instead of petrochemicals |

| 8 | Reduce Derivatives | Avoid unnecessary derivatization steps [1] | Minimize protecting groups in synthesis |

| 9 | Catalysis | Prefer catalytic over stoichiometric reagents [1] | Employ selective catalysts to enhance efficiency |

| 10 | Design for Degradation | Design products to break down into innocuous products [1] | Create biodegradable chemicals instead of persistent ones |

| 11 | Real-time Analysis | Develop methodologies for real-time pollution prevention [1] | Implement process analytical technology (PAT) |

| 12 | Inherently Safer Chemistry | Choose substances to minimize accident potential [1] | Select chemicals with higher safety margins |

Foundational Philosophy and Impact

The Anastas-Warner framework represents more than a checklist; it embodies a holistic approach to chemical design that considers the entire lifecycle of chemical products [13]. The principles advocate for an integrated strategy where multiple principles are applied in concert to achieve truly sustainable processes. This philosophical foundation shifted the chemical industry's focus from waste management to waste prevention, from hazard control to hazard reduction, and from environmental compliance to inherent sustainability [8] [14].

The formalization of these principles coincided with institutional developments that solidified green chemistry as a legitimate scientific discipline. The Green Chemistry Institute (GCI), founded in 1997 as a non-profit organization and later incorporated into the American Chemical Society (ACS) in 2001, provided an organizational structure for advancing these ideas through research, education, and collaboration [12]. The establishment of the Presidential Green Chemistry Challenge Awards in 1995 created a mechanism for recognizing and incentivizing innovation in the field [12].

Methodological Implementation: Green Chemistry in Practice

Analytical Methodologies and Green Metrics

The adoption of green chemistry principles necessitates robust methodological frameworks for assessment and implementation. Green Analytical Chemistry has emerged as a specialized subfield, adapting the core principles to analytical practices [8]. Key methodological advances include:

Solvent Replacement and Reduction: Implementing solvent-free methodologies or replacing hazardous organic solvents with aqueous systems, supercritical fluids (e.g., CO₂), or ionic liquids [14] [9]. For instance, the extraction of dyes from glow sticks using liquid CO₂ demonstrates a safer alternative to conventional organic solvents [13].

Waste Minimization Techniques: Developing miniaturized systems and on-line analysis approaches that significantly reduce reagent consumption and waste generation [8]. The application of real-time monitoring technologies allows for process control before hazardous substances form, aligning with Principle 11 [1] [13].

Green Metric Development: Establishing quantitative measures to evaluate environmental performance, including:

- E-Factor: Mass ratio of waste to desired product, highlighting processes with high waste generation [14]

- Atom Economy: Molecular-level calculation of efficiency by measuring incorporation of starting materials into products [14] [9]

- Process Mass Intensity: Comprehensive measure of total mass used in a process per mass of product [14]

Experimental Protocols in Green Synthesis

Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles (AgNPs)

Objective: To synthesize silver nanoparticles using plant extracts as reducing and stabilizing agents, replacing conventional chemical reductants [9].

Methodology:

- Extract Preparation: Prepare aqueous extract from plant biomass (e.g., Azadirachta indica leaves) through boiling and filtration

- Reaction Setup: Mix 1mM silver nitrate solution with plant extract in 9:1 ratio under continuous stirring

- Synthesis Conditions: Maintain reaction at 60°C for 2 hours with constant agitation

- Characterization: Monitor nanoparticle formation through UV-Vis spectroscopy (peak at ~420 nm) and characterize size distribution via dynamic light scattering

- Purification: Recover nanoparticles by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 20 minutes

Green Advantages: Eliminates toxic sodium borohydride or other chemical reducing agents; utilizes renewable plant materials; operates at moderate temperatures; produces biocompatible nanoparticles with enhanced antimicrobial properties [9].

Green Suzuki-Miyaura Cross-Coupling Reaction

Objective: To perform palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling with reduced environmental impact [13].

Methodology:

- Catalyst System: Employ heterogeneous palladium catalysts (e.g., Pd/C or Pd on supported nanoparticles) instead of homogeneous phosphine-based catalysts

- Solvent Selection: Use ethanol-water mixtures or PEG as reaction medium instead of traditional DMF or THF

- Reaction Conditions: Conduct coupling at 50-70°C with minimal equivalents of base (K₂CO₃)

- Processing: Implement catalyst recycling through filtration and reuse for multiple cycles

- Product Isolation: Utilize direct crystallization or membrane separation to avoid organic solvent extraction

Green Advantages: Reduces heavy metal waste through catalyst recycling; eliminates hazardous solvents; lowers energy requirements through moderate temperatures; achieves high atom economy characteristic of coupling reactions [13].

Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

The implementation of green chemistry principles requires specialized reagents and materials that align with sustainability goals. The following table details key solutions for green chemistry applications:

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Green Chemistry Applications

| Reagent/Material | Function | Green Alternative | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plant Extracts | Reducing/Stabilizing Agent | Replaces chemical reductants (e.g., NaBH₄) | Green synthesis of metal nanoparticles [9] |

| Supported Catalysts | Heterogeneous Catalysis | Replaces homogeneous catalysts | Pd/C for Suzuki coupling; clay/zeolite catalysts for nitration [13] [9] |

| Ionic Liquids | Green Solvents | Replace volatile organic compounds | Reaction media for various organic transformations [14] |

| Supercritical CO₂ | Extraction Solvent | Replaces halogenated solvents | Extraction of natural products, dyes [13] |

| Poly(methylhydro)siloxane | Reducing Agent | Safer alternative to metal hydrides | Reduction of citronellal to citronellol [13] |

| Renewable Substrates | Feedstock | Replaces petrochemical sources | Biomass-derived compounds for synthesis [1] [9] |

The historical trajectory from Silent Spring to the formal principles of green chemistry represents a fundamental restructuring of chemical philosophy and practice. What began as environmental critique evolved through regulatory development into a systematic framework that integrates sustainability into chemical research and development at the molecular level. The Anastas-Warner principles provide both a theoretical foundation and practical guidance for advancing chemical innovation while respecting ecological systems and human health.

For researchers and drug development professionals, these principles offer a strategic pathway to address growing demands for sustainable pharmaceutical production. The ongoing evolution of green chemistry—incorporating advances in green nanotechnology, biocatalysis, and artificial intelligence for materials design—continues to expand the tools available for sustainable chemical synthesis [9]. As global challenges surrounding resource depletion, environmental pollution, and climate change intensify, the principles established over this historical progression will undoubtedly play an increasingly critical role in guiding chemical innovation toward a more sustainable relationship between human industry and the planetary systems that support it.

Green chemistry is defined as the design of chemical products and processes that reduce or eliminate the use or generation of hazardous substances [2]. This transformative approach moves beyond pollution cleanup to prevent pollution at the molecular level, representing a fundamental shift in how chemists approach chemical design, manufacturing, and disposal [2]. The field emerged in the 1990s through the pioneering work of Paul Anastas and John Warner, who formalized the concept into a coherent framework with measurable principles [9] [15]. Their 1998 book, "Green Chemistry: Theory and Practice," established the foundational 12 principles that have since guided researchers, industries, and policymakers in developing safer, more sustainable chemical technologies [9] [1].

The historical context for green chemistry traces back to increasing environmental awareness throughout the late 20th century. The 1962 publication of Rachel Carson's "Silent Spring" highlighted the adverse effects of chemicals on the environment, helping spark the environmental movement [9]. In the subsequent decades, regulatory frameworks such as the U.S. Clean Air Act and Clean Water Act established governmental roles in environmental protection, setting the stage for more proactive approaches to chemical hazard management [15]. Green chemistry represents an evolutionary step beyond these command-and-control regulations by actively preventing pollution through innovative design of production technologies themselves, rather than focusing solely on end-of-pipe solutions [16].

The 12 Principles of Green Chemistry: A Technical Examination

The 12 principles of green chemistry provide a comprehensive framework for designing chemical products and processes that minimize environmental impact and health hazards. These principles address the entire life cycle of chemical products, from initial design to ultimate disposal [2]. The following technical examination details each principle with specific implementation considerations for researchers and drug development professionals.

Prevention

Preventing waste is better than treating or cleaning up waste after it has been created [2] [1]. This principle emphasizes source reduction as the most effective waste management strategy. In pharmaceutical development, this translates to designing synthetic routes that minimize by-product formation through careful reagent selection and reaction optimization. The principle advocates for a fundamental rethinking of process design where waste prevention becomes a primary objective rather than an afterthought [9].

Atom Economy

Synthetic methods should be designed to maximize the incorporation of all materials used in the process into the final product [2] [1]. Atom economy, also known as atom efficiency, quantifies how effectively starting materials are utilized in the final product [9]. The Diels-Alder reaction exemplifies this principle with theoretical 100% atom economy, as all atoms from starting materials are incorporated into the product [9]. For drug development professionals, calculating atom economy provides a crucial metric for comparing alternative synthetic routes beyond traditional yield measurements. This principle encourages molecular architects to design transformations where few or no atoms are wasted [9].

Less Hazardous Chemical Syntheses

Wherever practicable, synthetic methods should be designed to use and generate substances that possess little or no toxicity to human health and the environment [2] [1]. This principle directs chemists to select synthetic pathways that avoid hazardous intermediates and byproducts. Implementation requires thorough assessment of all substances involved in a process, not just the final product. For instance, Choudary et al. developed a more efficient and selective method for nitration of aromatic compounds using clay and zeolite catalysts instead of traditional acid mixtures, resulting in near-zero waste emissions and reduced toxicity [9].

Designing Safer Chemicals

Chemical products should be designed to effect their desired function while minimizing their toxicity [2] [1]. This principle requires deep understanding of structure-activity relationships to design effective yet minimally toxic compounds. Pharmaceutical researchers can apply this by modifying molecular structures to reduce toxicity while maintaining therapeutic efficacy. An exemplary application is the development of the herbicide Rinskor, which can be applied at significantly lower rates (5-50 g/hectare) than traditional herbicides, resulting in fewer pesticide residues in the environment and food chain [9].

Safer Solvents and Auxiliaries

The use of auxiliary substances (e.g., solvents, separation agents, etc.) should be made unnecessary wherever possible and innocuous when used [2] [1]. Solvents often constitute the majority of mass in pharmaceutical processes, making this principle particularly relevant. Researchers should prioritize water or other benign solvents and avoid chlorinated or volatile organic compounds whenever possible. The expanding field of green solvent research includes bio-based solvents, supercritical fluids, and solvent-free systems that reduce environmental impact while maintaining performance [16].

Design for Energy Efficiency

Energy requirements of chemical processes should be recognized for their environmental and economic impacts and should be minimized [2] [1]. This principle encourages conducting reactions at ambient temperature and pressure whenever possible [1]. Process intensification through continuous flow chemistry, microwave assistance, or other energy-efficient technologies can significantly reduce the carbon footprint of chemical manufacturing. Energy consumption should be a key parameter in process optimization alongside yield and purity, especially in industrial-scale pharmaceutical production [9].

Use of Renewable Feedstocks

A raw material or feedstock should be renewable rather than depleting whenever technically and economically practicable [2] [1]. This principle shifts the focus from petroleum-based starting materials to biomass, agricultural waste, and other renewable resources. For example, Future Origins developed a single-step, whole-cell fermentation process to produce C12/C14 fatty alcohols from renewable plant-derived sugars as an alternative to palm kernel oil, lowering global warming potential by an estimated 68% compared to conventional methods [17].

Reduce Derivatives

Unnecessary derivatization should be minimized or avoided if possible, because such steps require additional reagents and can generate waste [2] [1]. Protecting groups and other temporary modifications decrease synthetic efficiency and increase waste generation. Modern synthetic methodologies that enable selective transformations without protection steps align with this principle. For pharmaceutical manufacturers, reducing derivatives translates to shorter synthetic sequences with improved overall efficiency and reduced environmental impact [16].

Catalysis

Catalytic reagents (as selective as possible) are superior to stoichiometric reagents [2] [1]. Catalysts enable transformations with reduced energy requirements and higher selectivity while minimizing waste. The 2005 Nobel Prize in Chemistry awarded for olefin metathesis highlighted the importance of catalytic methods in green chemistry [16] [15]. Recent advances include Keary Engle's development of air-stable nickel catalysts that efficiently convert simple feedstocks into complex molecules without energy-intensive inert-atmosphere storage [17]. Biocatalysis represents another frontier, as demonstrated by Merck's biocatalytic process for preparing the investigational antiviral islatravir using nine enzymes in a single aqueous stream [17].

Design for Degradation

Chemical products should be designed so that at the end of their function they break down into innocuous degradation products and do not persist in the environment [2] [1]. This principle addresses concerns about chemical persistence and bioaccumulation. Pharmaceutical designers must balance stability requirements with environmental fate, considering metabolic pathways and environmental breakdown products. The development of biodegradable antifouling compounds like 4,5-dichloro-2-n-octyl-4-isothiazolin-3-one as safer alternatives to persistent organotin compounds demonstrates practical application of this principle [9].

Real-time Analysis for Pollution Prevention

Analytical methodologies need to be further developed to allow for real-time, in-process monitoring and control prior to the formation of hazardous substances [2] [1]. Process Analytical Technology (PAT) enables continuous monitoring and immediate correction of process parameters to prevent hazardous byproduct formation. Implementation includes in-line spectroscopy, automated sampling, and feedback control systems that maintain optimal reaction conditions while minimizing off-spec products and waste [16].

Inherently Safer Chemistry for Accident Prevention

Substances and the form of a substance used in a chemical process should be chosen to minimize the potential for chemical accidents, including releases, explosions, and fires [2] [1]. This principle focuses on minimizing hazards through chemical selection rather than relying solely on engineering controls. Strategies include using less volatile solvents, replacing explosive reagents with safer alternatives, and designing processes that operate under milder conditions. For pharmaceutical manufacturers, this approach reduces risks to employees, communities, and the environment while improving process reliability [9].

Table 1: The 12 Principles of Green Chemistry with Key Implementation Strategies

| Principle | Key Implementation Strategies | Pharmaceutical Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Prevention | Design low-waste syntheses; optimize reaction selectivity | Process intensification; continuous manufacturing |

| Atom Economy | Select reactions with high atom utilization; avoid protecting groups | Cycloadditions; rearrangement reactions; tandem processes |

| Less Hazardous Syntheses | Replace toxic reagents; minimize hazardous intermediates | Biocatalysis; photoredox catalysis; mechanochemistry |

| Designing Safer Chemicals | Structure-activity relationship analysis; bioisosterism | Prodrug design; metabolite-guided optimization |

| Safer Solvents & Auxiliaries | Use water or PEG; avoid chlorinated solvents | Aqueous reaction media; supercritical CO2 extraction |

| Energy Efficiency | Ambient temperature reactions; process intensification | Flow chemistry; microwave-assisted synthesis |

| Renewable Feedstocks | Biomass-derived starting materials; fermentation-based processes | Bio-based platform chemicals; biocatalytic synthesis |

| Reduce Derivatives | Protecting-group-free synthesis; convergent routes | Late-stage functionalization; one-pot multistep reactions |

| Catalysis | Enzymatic catalysis; heterogeneous catalysis; photocatalysis | Biocatalytic steps; transition metal-catalyzed couplings |

| Design for Degradation | Incorporate hydrolyzable linkages; consider environmental fate | Biodegradable excipients; metabolically labile pharmaceuticals |

| Real-time Analysis | Process Analytical Technology (PAT); in-line spectroscopy | Real-time reaction monitoring; automated feedback control |

| Accident Prevention | Substitute explosive reagents; use safer solvent mixtures | Hydrogenation in flow; continuous neutralization systems |

Quantitative Assessment Methodologies for Green Chemistry

Evaluating the "greenness" of chemical processes requires robust quantitative assessment methodologies. A comprehensive approach developed by researchers includes calculating a greenness value that incorporates environmental, safety, resource, and economic factors [18]. This systematic framework enables researchers to quantitatively compare processes and measure improvements.

The fundamental equation for greenness assessment integrates multiple dimensions:

Greenness = α · Σ environment + β · Σ safety + γ · Σ resource + δ · Σ economy [18]

Where α, β, γ, and δ are weighting factors derived from analytic hierarchy process (AHP) analysis, and the sigma terms represent quantitative measures in each category [18].

Environmental Impact Quantification

The environmental component (Σ environment) includes greenhouse gas emissions and hazardous substance impacts:

Σ Environment = αa · Σ GHGs + αb · Σ hazardous substances [18]

Greenhouse gases (GHGs) are calculated as tCO2 reduction compared to a baseline process [18]. Hazardous substances assessment incorporates both health hazard factors (HHF) and environmental hazard factors (EHF):

Σ Hazardous substances = αa1 · Σ HHF + αa2 · Σ EHF [18]

Health hazard factors are quantified using established metrics including carcinogenicity classifications (IRIS categories), permissible exposure limits (PEL), and risk phrases (R-Phrases) [18]. Environmental hazard factors incorporate acute toxicity measures (EC50) and environmental risk phrases [18].

Case Study: Waste Acid Reutilization Assessment

A quantitative assessment of waste acid reutilization from electronic parts pickling demonstrated a 42% enhancement in greenness level compared to the pre-improvement process [18]. By installing cooling equipment to address excessive use of nitrogen chemicals, the acid solution could be reused three times instead of being discarded after first use [18]. This improvement reduced both chemical consumption and waste treatment volume while maintaining process efficiency, demonstrating the economic and environmental benefits achievable through green chemistry implementation [18].

Table 2: Quantitative Greenness Assessment Metrics and Calculation Methods

| Assessment Category | Key Metrics | Calculation Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental Impact | Greenhouse gas emissions; Hazardous substance impacts | GHG: tCO2 reduction vs. baseline [18]; Hazardous substances: HHF + EHF based on IRIS, PEL, EC50, R-Phrases [18] |

| Safety | Accident potential; Chemical hazards | R-Phrase analysis for raw materials, products/by-products, and emissions [18] |

| Resource Consumption | Raw material efficiency; Waste generation | Resource = 1 - (usage after improvement)/(usage before improvement) [18] |

| Economic Feasibility | Production cost reduction; Market impact | (Production cost reduction)/(baseline expenditures) + (consumer price reduction)/(baseline retail price) [18] |

Experimental Protocols and Research Applications

Green Synthesis of Nanoparticles

The green synthesis of nanoparticles has emerged as a sustainable alternative to traditional methods that often rely on toxic reagents [9]. Plant-derived biomolecules serve as reducing and stabilizing agents in the synthesis of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) [9]. These eco-friendly approaches eliminate hazardous chemicals while yielding biocompatible nanoparticles with enhanced antimicrobial and catalytic properties [9].

Protocol: Plant-Mediated Silver Nanoparticle Synthesis

- Plant Extract Preparation: Fresh plant leaves (e.g., Azadirachta indica) are washed, dried, and finely ground. A 10% (w/v) aqueous extract is prepared by boiling 10g of leaves in 100mL deionized water for 10 minutes, followed by filtration.

- Reaction Setup: 1mM silver nitrate solution is prepared in deionized water. The plant extract is added to the silver nitrate solution in a 1:9 ratio (extract:AgNO3 solution) under continuous stirring.

- Synthesis Conditions: The reaction mixture is maintained at 60°C with constant stirring for 2-4 hours. Nanoparticle formation is indicated by color change from pale yellow to reddish-brown.

- Purification: Synthesized nanoparticles are centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 20 minutes, washed with deionized water, and redispersed for characterization.

- Characterization: UV-Vis spectroscopy (peak at ~420nm), TEM (size and morphology), XRD (crystallinity), and FTIR (capping agents) [9].

Biocatalytic Process for Pharmaceutical Manufacturing

Merck's biocatalytic process for preparing the nucleoside islatravir demonstrates principle #9 (catalysis) in pharmaceutical manufacturing [17]. The original 16-step clinical supply route was replaced with a single biocatalytic cascade involving nine enzymes that convert glycerol into islatravir in a single aqueous stream [17].

Protocol: Enzymatic Cascade for Nucleoside Synthesis

- Enzyme Selection: Identify and optimize nine enzymes for the cascade reaction: glycerol kinase, L-amino acid oxidase, catalase, and nucleoside salvage pathway enzymes.

- Reaction Setup: Prepare an aqueous reaction mixture containing glycerol, phosphate donors, and cofactors. Add the enzyme cocktail in optimized ratios.

- Process Conditions: Maintain reaction at 30°C, pH 7.0-7.5, with gentle agitation. Monitor reaction progress by HPLC.

- Process Intensification: Conduct the cascade in a single reactor without workups, isolations, or organic solvents [17].

- Product Recovery: Islatravir is recovered through direct crystallization from the reaction mixture, achieving high purity and yield while minimizing waste.

Advanced Research Applications and Industrial Implementation

Green Chemistry in Pharmaceutical Development

The pharmaceutical industry has embraced green chemistry principles to develop more sustainable manufacturing processes. Beyond the biocatalytic synthesis of islatravir [17], numerous pharmaceutical companies have implemented green chemistry approaches to reduce environmental impact while maintaining product quality and efficacy. The ACS Green Chemistry Challenge Awards have recognized multiple pharmaceutical innovations, including:

- Streamlined Synthetic Pathways: Reducing step count in API synthesis to minimize resource consumption and waste generation

- Continuous Flow Processing: Replacing batch processes with continuous manufacturing to improve energy efficiency and safety

- Green Solvent Substitution: Replacing hazardous solvents with safer alternatives in drug substance manufacturing

These applications demonstrate that green chemistry principles align with both environmental and business objectives through reduced costs, improved efficiency, and decreased regulatory burden [17].

Sustainable Materials and Circular Economy

Green chemistry principles are increasingly applied to develop sustainable materials and circular economy models. Pure Lithium Corporation's Brine to Battery method produces 99.9% pure battery-ready lithium-metal anodes in one step using electrodeposition technology from real-world brines [17]. This process reduces water and energy use while enabling co-location of feedstock, extraction, and manufacturing [17].

Cross Plains Solutions developed SoyFoam, a fire-suppression foam consisting of defatted soybean meal and biobased ingredients that extinguishes Class A and Class B fires without PFAS or related fluorine chemicals [17]. This innovation eliminates environmental and health concerns for firefighters, first responders, and local communities while maintaining performance requirements [17].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Green Chemistry Applications

| Reagent/Catalyst | Function | Green Chemistry Advantage | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Air-stable Nickel Catalysts | Transition metal catalysis for coupling reactions | Eliminates need for energy-intensive inert-atmosphere storage [17] | Streamlined access to functional compounds from medicines to advanced materials [17] |

| Enzyme Cocktails | Biocatalysis for complex syntheses | Enables aqueous-based reactions with high selectivity; reduces solvent waste [17] | Merck's biocatalytic process for islatravir preparation [17] |

| Plant-derived Biomolecules | Reducing and stabilizing agents for nanoparticle synthesis | Replaces toxic chemical reagents; utilizes renewable resources [9] | Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles with antimicrobial properties [9] |

| Supercritical CO2 | Alternative solvent for extraction and reactions | Non-toxic, non-flammable alternative to organic solvents; easily recycled [16] | Polystyrene foam production without ozone-depleting blowing agents [16] |

| Clay and Zeolite Catalysts | Solid acid catalysts for various transformations | Replaces corrosive liquid acids; enables easier separation and reuse [9] | Green nitration of aromatic compounds with near-zero waste [9] |

The 12 principles of green chemistry established by Anastas and Warner provide a comprehensive framework for sustainable chemical design that has transformed both academic research and industrial practice [2] [1]. By addressing environmental impacts at the molecular level and emphasizing pollution prevention rather than remediation, these principles enable chemists and drug development professionals to create innovative solutions that align economic, environmental, and social objectives [2].

The continued evolution of green chemistry, including quantitative assessment methodologies [18], novel synthetic techniques [17], and circular economy applications [17], demonstrates the framework's adaptability to emerging scientific and sustainability challenges. As global concerns about climate change, resource depletion, and chemical pollution intensify, the principles of green chemistry offer a proven pathway toward developing the sustainable technologies needed for a healthier planet [9]. For researchers and pharmaceutical professionals, integrating these principles into daily practice represents both an ethical imperative and strategic opportunity to advance both science and sustainability.

Green chemistry, defined as the design of chemical products and processes that reduce or eliminate the use or generation of hazardous substances, represents a fundamental shift in chemical research and engineering [2]. Coined in the 1990s by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), this approach advocates for a proactive methodology that prevents pollution at the molecular level, rather than managing it after it has been created [2] [19]. The foundational framework for this field was established by Paul Anastas and John Warner in their seminal work, Green Chemistry: Theory and Practice (1998), which introduced the 12 Principles of Green Chemistry [20]. These principles provide a systematic guide for designing safer, more efficient chemical syntheses and processes.

Within this framework, metrics are essential for quantifying the environmental and efficiency profiles of chemical processes. They provide tangible data to guide decision-making and track progress toward sustainability goals. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, three core metrics are particularly crucial: Atom Economy, E-Factor, and Process Mass Intensity (PMI). These tools allow for the critical assessment of synthetic routes and manufacturing processes, enabling the pharmaceutical industry and other chemical sectors to minimize waste, reduce environmental impact, and improve cost-effectiveness [20] [21] [22]. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of these three core metrics, detailing their calculation, application, and role in advancing the principles of green chemistry.

Foundational Principles and Definitions

The first principle of green chemistry, Prevention, asserts that it is better to prevent waste than to treat or clean up waste after it is formed [20]. This principle is the cornerstone upon which the metrics of Atom Economy, E-Factor, and PMI are built, as they all serve to quantify and drive waste reduction. The E-factor, developed by Roger Sheldon, specifically relates the weight of waste co-produced to the weight of the desired product, providing a direct measure of a process's environmental footprint [20] [23].

The second principle, Atom Economy, developed by Barry Trost, calls for synthetic methods to be designed to maximize the incorporation of all starting materials into the final product [20] [24]. It is a theoretical metric that highlights the inherent efficiency of a chemical reaction. Principle #5, Safer Solvents and Auxiliaries, advises against the use of auxiliary substances like solvents and separation agents, or to select safer ones when their use is unavoidable [20]. This principle is critically reflected in the E-Factor and PMI, which account for the total mass of all materials used, including solvents, thereby providing a more comprehensive picture of a process's efficiency and environmental impact than Atom Economy alone [20] [22].

Core Metric 1: Atom Economy

Concept and Calculation

Atom Economy is a fundamental metric that evaluates the efficiency of a chemical reaction on a molecular level. It answers a simple but profound question: "What atoms of the reactants are incorporated into the final desired product(s) and what atoms are wasted?" [20] Traditionally, chemists have relied on percent yield to measure reaction efficiency; however, percent yield only indicates what proportion of the theoretical maximum amount of product was successfully isolated. It does not account for atoms from starting materials that are discarded as byproducts [20] [25]. Atom economy shifts the focus to the intrinsic elegance of a synthesis, promoting routes where most reactant atoms become part of the desired product.

The calculation for percent atom economy is straightforward:

% Atom Economy = (Formula Weight of Desired Product / Total Formula Weight of All Reactants) × 100 [24] [25]

Experimental Protocol and Industry Application

To illustrate, consider the classic synthesis of ibuprofen. The original six-step Boots process, now superseded, had a lower overall atom economy. The final step of this older process can be used to demonstrate the calculation:

- Reaction: 1-Butanol reacts with Sodium Bromide and Sulfuric Acid to yield 1-Bromobutane.

- Text Version of Reaction:

H₃C-CH₂-CH₂-CH₂-OH + NaBr + H₂SO₄ → H₃C-CH₂-CH₂-CH₂-Br + NaHSO₄ + H₂O[20] [25] - Calculation:

- Formula weight of desired product (1-Bromobutane): 137 g/mol

- Sum of formula weights of all reactants: (74 + 103 + 98) g/mol = 275 g/mol

- % Atom Economy = (137 / 275) × 100 = 50% [20]

This result means that even with a 100% yield, half of the mass of the reactant atoms is wasted in unwanted byproducts (sodium bisulfate and water) [20]. In contrast, the modern, greener Boots-Hoechst synthesis of ibuprofen is designed to be significantly more atom-economical, with a key step achieving an atom economy of 77%, and further industrial integration can lead to an effective atom economy of nearly 100% by finding uses for by-products [24]. This application demonstrates how atom economy serves as a powerful guide for chemists in designing syntheses that are inherently more efficient and generate less waste, a critical concern in pharmaceutical manufacturing where materials are expensive and waste disposal costs are high [25].

Table 1: Key Metrics for Evaluating Chemical Reaction Efficiency

| Metric | Formula | What It Measures | Ideal Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atom Economy | (FW of Product / Σ FW of Reactants) × 100 [24] [25] | Intrinsic efficiency of a reaction pathway; the percentage of reactant atoms incorporated into the desired product. | 100% |

| E-Factor | Total Mass of Waste / Total Mass of Product [23] [26] | The total mass of waste produced per mass of product, measuring overall environmental impact. | 0 |

| Process Mass Intensity (PMI) | Total Mass of Materials Used / Total Mass of Product [21] [22] | The total mass of all materials (reactants, solvents, etc.) required to produce a unit mass of product. | 1 |

Core Metric 2: E-Factor (Environmental Factor)

Concept and Calculation

The E-Factor (Environmental Factor) provides a more comprehensive measure of a process's environmental acceptability by accounting for the total waste generated [23]. While atom economy is an excellent theoretical tool for comparing reactions, the E-factor captures the practical reality of a chemical process, including waste from solvents, separation agents, and leftover reagents [20]. The E-factor is defined as:

E-Factor = Total Mass of Waste from Process / Total Mass of Product [23] [26]

A lower E-factor is desirable, with zero being the ideal, indicating no waste. The "total mass of waste" is typically calculated as the total mass of materials entering the process minus the mass of the desired product [23]. It is important to note that what is defined as waste can vary. For example, water is often excluded from the calculation unless it is severely contaminated, and recyclable reagents may not be counted as waste if they are effectively recovered and reused [23].

Interpretation and Industrial Context

The acceptable E-factor varies significantly across the chemical industry, largely dependent on the value of the product and the scale of production.

Table 2: Typical E-Factor Values Across the Chemical Industry [23]

| Industry Sector | Scale of Production | Typical E-Factor Range |

|---|---|---|

| Petrochemicals & Bulk Chemicals | Hundreds of thousands to millions of tons/year | 1 to 5 |

| Fine Chemicals & Specialties | A few thousand tons/year | 5 to >50 |

| Pharmaceuticals | Tens to hundreds of tons/year | 25 to >100 |

As shown in Table 2, the pharmaceutical industry historically has very high E-factors, sometimes exceeding 100, meaning over 100 kg of waste can be generated for every 1 kg of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) produced [20] [23]. This is due to complex multi-step syntheses and the heavy use of solvents and purification agents. However, this realization has driven the pharmaceutical industry to become a leader in adopting green chemistry principles to dramatically reduce waste, with some companies achieving ten-fold reductions through process redesign [20]. The nature of the waste also matters; the environmental quotient (EQ) concept attempts to weight the E-factor by the perceived hazardousness of the waste, acknowledging that a kilogram of salt is not equivalent to a kilogram of heavy metal waste [23].

Core Metric 3: Process Mass Intensity (PMI)

Concept and Relation to Other Metrics

Process Mass Intensity has emerged as a key metric, particularly within the pharmaceutical industry, to drive more sustainable processes [20] [22]. While related to the E-factor, PMI offers a different perspective and is defined as:

PMI = Total Mass of Materials Used / Total Mass of Product [21] [22]

The "total mass of materials" includes everything used in the process: reactants, reagents, solvents (both reaction and purification), water, and process aids [20] [22]. The relationship between PMI and E-factor is simple:

PMI = E-Factor + 1 [22]

This equation highlights that PMI gives a direct measure of the total material footprint required to produce a unit of product. A PMI of 1 is ideal, indicating that 100% of the input mass is incorporated into the product. The ACS Green Chemistry Institute Pharmaceutical Roundtable has championed PMI as a comprehensive benchmark because it directly focuses attention on the main drivers of process inefficiency, cost, and environmental, safety, and health impact [21] [22].

Methodology and Calculator Tools

Calculating PMI involves a meticulous accounting of all mass inputs for a process. The ACS GCI Pharmaceutical Roundtable has developed a PMI Calculator to standardize this assessment [21]. The methodology involves:

- Defining Process Scope: Clearly defining the synthetic steps included in the calculation, from raw materials to the final isolated API.

- Summing Mass Inputs: Summing the masses of all input materials for the defined process. This includes:

- Accounting for Product Mass: Using the mass of the final, isolated product (e.g., the API).

- Calculation: The tool then computes the PMI by dividing the total input mass by the product mass.

For more complex, multi-branch syntheses, the Roundtable offers a Convergent PMI Calculator which uses the same fundamental calculation but allows for the integration of multiple synthesis branches [21]. More advanced tools, like the PMI Prediction Calculator, allow scientists to estimate the probable PMI of a proposed synthetic route prior to any laboratory work, enabling greener design choices at the earliest stages of research and development [22].

Diagram: Process Mass Intensity (PMI) Calculation Workflow

Comparative Analysis and Practical Toolkit

Synergies and Limitations in Practice

Atom Economy, E-Factor, and PMI are complementary metrics, each providing a different lens for evaluating a chemical process. Atom Economy is a superb tool for the initial design phase, guiding chemists toward inherently efficient bond-forming reactions. However, its key limitation is that it is a theoretical calculation that only considers reaction stoichiometry, ignoring solvents, energy, and actual yield [20]. A reaction can have 100% atom economy but still be highly wasteful if it requires large amounts of solvent for purification or has a very low yield.

The E-Factor and PMI address these limitations by measuring the actual mass of materials consumed and wasted in a real process. They provide a holistic view that is crucial for evaluating the overall environmental and economic impact, especially at an industrial scale. The main challenge with E-Factor and PMI is the need for precise mass-tracking of all materials, which can be complex in multi-step processes. Furthermore, while PMI gives a total mass figure, it does not, on its own, distinguish between a kilogram of water and a kilogram of a hazardous solvent, which is why the concept of a greenness score like iGAL, which can incorporate environmental and safety factors, is also used alongside PMI for a more nuanced assessment [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents and Materials

In the pursuit of optimizing these green metrics, chemists rely on a variety of reagents and materials. The following table details key solutions used in developing efficient, green processes.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Green Chemistry

| Reagent/Material | Function in Green Chemistry | Application Example & Metric Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Catalysts (e.g., Zeolites, Supported Metals) | Enable reactions with less energy and higher selectivity; used in small amounts and often recyclable. | Replaces stoichiometric reagents (e.g., in oxidation), dramatically improving Atom Economy and reducing E-Factor [27]. |

| Biocatalysts (Enzymes) | Highly selective and efficient catalysts that operate under mild, aqueous conditions. | Used in the synthesis of Simvastatin to reduce solvent use and waste, slashing PMI and E-Factor [20] [25]. |

| Safer Solvents (e.g., 2-MeTHF, Cyrene, Water) | Replace hazardous solvents (e.g., chlorinated, benzene) to reduce toxicity and process hazard. | Guides like the ACS GCI Solvent Selection Guide help choose solvents that improve safety and can lower PMI if less is used or recovery is easier [25]. |

| Renewable Feedstocks (e.g., Biomass, Plant Oils) | Starting materials derived from renewable resources, reducing reliance on petrochemicals. | Using limonene from citrus waste as a feedstock for fine chemicals, supporting principle #7 and impacting the lifecycle PMI [27]. |

Diagram: Relationship Between Green Chemistry Metrics

The adoption of green chemistry is not merely an ethical choice but a strategic imperative that aligns environmental responsibility with economic and operational excellence [19]. The metrics of Atom Economy, E-Factor, and Process Mass Intensity provide the critical, quantitative foundation necessary to drive this transformation. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, mastering these tools is essential for designing chemical processes that are inherently safer, more efficient, and less wasteful.

As the chemical industry continues to evolve, the integration of these metrics with emerging technologies—such as artificial intelligence for molecular design, biocatalysis, and electrosynthesis—will further empower scientists to meet the goals laid out by Anastas and Warner [19]. By rigorously applying Atom Economy, E-Factor, and PMI, the scientific community can continue to pave the way toward a more sustainable future, turning the foundational principles of green chemistry into measurable, real-world impact.

The Distinct Role of Green Chemistry in the Broader Sustainable Chemistry Landscape

Green chemistry is formally defined as the design of chemical products and processes that reduce or eliminate the use and generation of hazardous substances [1]. Established in the 1990s through the foundational work of Paul Anastas and John Warner, green chemistry provides a specific, molecular-level framework for sustainability within the chemical enterprise [8] [9]. The field emerged from growing environmental awareness catalyzed by events such as the 1962 publication of Rachel Carson's Silent Spring and the 1972 Stockholm Conference, which brought global attention to environmental degradation [8] [9]. The United States Environmental Protection Agency's launch of the "Alternative Synthetic Routes for Pollution Prevention" program in 1991 formally established the field, which was later codified with the 1998 publication of Green Chemistry: Theory and Practice by Anastas and Warner [8] [3].

It is crucial to distinguish green chemistry from the broader concept of sustainable chemistry. While sustainable chemistry encompasses the wider economic, social, and environmental dimensions of sustainability, green chemistry specifically focuses on molecular-level design principles that prevent pollution and reduce resource consumption at the source [3]. As articulated by leaders in the field, "Green chemistry is the design of chemical products and processes that reduce or eliminate the use and generation of hazardous substances" [1]. This distinction positions green chemistry as the fundamental scientific toolkit that enables chemists and engineers to contribute directly to sustainable development goals through molecular innovation.

The Foundational Framework: Anastas and Warner's 12 Principles

The 12 Principles of Green Chemistry established by Paul Anastas and John Warner provide a comprehensive framework for designing chemical products and processes that minimize environmental and health impacts [20] [1]. These principles have remained remarkably relevant since their introduction in 1998 and continue to guide research and development across academia and industry. The complete set of principles with their core objectives is presented in Table 1 below.

Table 1: The 12 Principles of Green Chemistry by Anastas and Warner

| Principle Number | Principle Name | Core Objective |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Prevention | Prevent waste rather than treating or cleaning it up after formation [20] [1]. |

| 2 | Atom Economy | Design synthetic methods to maximize incorporation of all materials into the final product [20] [1]. |

| 3 | Less Hazardous Chemical Syntheses | Design synthetic methods that use and generate substances with little or no toxicity [20] [1]. |

| 4 | Designing Safer Chemicals | Design chemical products to preserve efficacy while reducing toxicity [20] [1]. |

| 5 | Safer Solvents and Auxiliaries | Eliminate or use innocuous auxiliary substances [20] [1]. |

| 6 | Design for Energy Efficiency | Minimize energy requirements of chemical processes [20] [1]. |

| 7 | Use of Renewable Feedstocks | Use renewable rather than depleting raw materials [20] [1]. |

| 8 | Reduce Derivatives | Minimize unnecessary derivatization that requires additional reagents and generates waste [20] [1]. |

| 9 | Catalysis | Prefer catalytic reagents over stoichiometric reagents [20] [1]. |

| 10 | Design for Degradation | Design chemical products to break down into innocuous degradation products [20] [1]. |

| 11 | Real-time Analysis for Pollution Prevention | Develop analytical methodologies for real-time monitoring before hazardous substances form [20] [1]. |

| 12 | Inherently Safer Chemistry for Accident Prevention | Choose substances and their forms to minimize potential for chemical accidents [20] [1]. |

These principles operate as an interconnected system rather than isolated concepts. The first principle of waste prevention establishes the overarching goal, while subsequent principles provide specific implementation pathways. For example, atom economy (Principle 2) and catalysis (Principle 9) directly contribute to waste prevention by maximizing resource efficiency [20]. Similarly, Principles 3-6 and 12 focus on reducing hazard and risk throughout the chemical process, while Principles 7, 10, and 11 address the broader environmental context and lifecycle impacts [28] [1].

The diagram below illustrates the logical relationships between the 12 principles and how they collectively contribute to the overarching goals of green chemistry.

Quantitative Metrics in Green Chemistry Practice

The implementation of green chemistry principles requires robust metrics to quantify environmental improvements and guide decision-making. Several key metrics have been developed and adopted across pharmaceutical and fine chemical industries to measure the "greenness" of processes.

Table 2: Core Metrics for Assessing Green Chemistry Performance

| Metric | Calculation | Application | Ideal Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| E-factor | Total waste (kg) / Product (kg) [20] | Measures waste generation efficiency [20] | 0 |

| Process Mass Intensity (PMI) | Total mass in process (kg) / Mass of product (kg) [20] | Comprehensive resource efficiency assessment [20] | 1 |

| Atom Economy | (MW of desired product / Σ MW of reactants) × 100% [20] | Theoretical maximum incorporation of atoms into product [20] | 100% |

| Reaction Mass Efficiency | (Mass of product / Σ Mass of reactants) × 100% | Actual mass efficiency incorporating yield [20] | 100% |

The pharmaceutical industry, through organizations like the ACS Green Chemistry Institute Pharmaceutical Roundtable, has favored Process Mass Intensity (PMI) as a comprehensive metric because it accounts for all materials used in a process, including water, organic solvents, raw materials, reagents, and process aids [20]. This aligns with the preventive focus of Principle 1, as PMI captures the total resource consumption rather than just waste output. Significant progress has been made, with some pharmaceutical companies achieving up to ten-fold reductions in waste through application of green chemistry principles to API process design [20].

Experimental Methodologies and Protocols

Solvent-Free Synthesis via Mechanochemistry

Objective: To demonstrate Principle 5 (Safer Solvents) and Principle 6 (Energy Efficiency) through solvent-free synthesis using mechanical energy [6].

Background: Mechanochemistry utilizes mechanical force rather than solvents to drive chemical reactions, addressing the significant environmental impact of solvents which often account for the majority of waste in pharmaceutical production [6].

Protocol:

- Reaction Setup: Place reactants in a high-energy ball mill vessel with grinding media (e.g., stainless steel or zirconia balls).

- Milling Parameters: Optimize milling frequency (typically 15-30 Hz) and time (10-60 minutes) based on reaction monitoring.

- Stoichiometry: Use stoichiometric ratios of reactants without solvent dilution.

- Temperature Control: Reactions typically proceed at ambient temperature without external heating.

- Product Isolation: Extract product directly from milling vessel with minimal solvent (typically 2-5 mL per gram of product) for purification.

- Analysis: Characterize yield and purity using standard analytical methods (NMR, HPLC, MS).

Application Example: Synthesis of solvent-free imidazole-dicarboxylic acid salts for proton-conducting electrolytes in fuel cells. This mechanochemical approach provided high yields, reduced solvent usage, and lower energy consumption compared to solution-based synthesis [6].

Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles in Aqueous Media

Objective: To demonstrate Principle 5 (Safer Solvents) through the synthesis of silver nanoparticles using water as a benign solvent instead of toxic organic solvents [6].

Background: Traditional nanoparticle synthesis often employs hazardous organic solvents. Recent breakthroughs show that water can effectively function as a solvent for catalysis, representing a paradigm shift in sustainable chemistry [6].

Protocol:

- Solution Preparation: Dissolve silver nitrate (precursor) in deionized water to create a 1-10 mM solution.

- Reduction Method: Introduce reducing electrons directly into the aqueous silver nitrate solution to drive nanoparticle formation.

- Reaction Monitoring: Use UV-Vis spectroscopy to track surface plasmon resonance changes indicating nanoparticle growth (peak ~400 nm).

- Size Control: Manipulate reaction time and electron flux to control nanoparticle size distribution.

- Stabilization: Employ natural stabilizers (e.g., plant biomolecules) to prevent aggregation without toxic capping agents.

- Characterization: Analyze size, morphology, and composition using TEM, DLS, and XRD.