Green Chemistry Core Competencies: A Sustainable Curriculum for Modern Drug Development

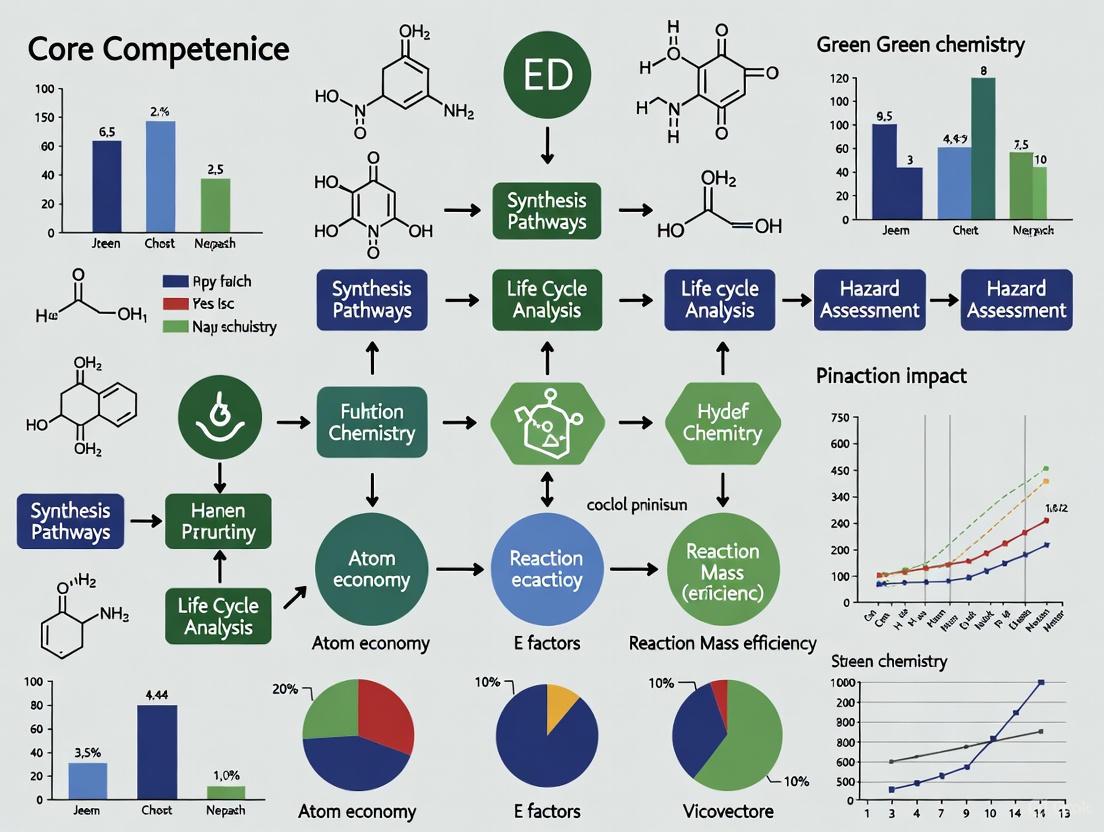

This curriculum provides a comprehensive framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to master the core competencies of Green Chemistry.

Green Chemistry Core Competencies: A Sustainable Curriculum for Modern Drug Development

Abstract

This curriculum provides a comprehensive framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to master the core competencies of Green Chemistry. It bridges foundational theory with practical application, covering the 12 Principles of Green Chemistry, advanced methodologies like catalysis and AI, strategies for optimizing complex syntheses, and metrics for validating environmental and economic benefits. Designed to align with global sustainability goals and industry demands, this guide empowers professionals to design safer, more efficient, and environmentally responsible pharmaceutical processes.

The Foundations of Green Chemistry: Principles, Drivers, and Business Alignment

Understanding the 12 Principles of Green Chemistry and Their Framework

Green Chemistry is defined as the design of chemical products and processes that reduce or eliminate the use and generation of hazardous substances [1]. This proactive, preventive approach represents a fundamental shift from traditional pollution cleanup strategies to innovative design that makes pollution unnecessary [2]. First formulated by Paul Anastas and John Warner in their 1998 book Green Chemistry: Theory and Practice, the 12 Principles of Green Chemistry provide a comprehensive framework for achieving these goals through focused attention on efficiency, hazard reduction, and renewable resource utilization [3] [4] [5]. For researchers and drug development professionals, these principles offer a systematic methodology for addressing environmental, economic, and regulatory challenges simultaneously while advancing core competencies in sustainable science.

The historical context of green chemistry emerged from prominent environmental crises in the 1960s that revealed the limitations of the "dilution as the solution to pollution" paradigm [2]. By the 1990s, it became increasingly clear that preventing waste at the source was significantly more effective and economical than treating pollution after its generation [2]. This recognition, coupled with growing regulatory pressures and waste disposal costs, created an imperative for the chemical industry to develop cleaner technologies and safer products [1] [4]. The pharmaceutical industry, in particular, faced mounting challenges as synthetic routes for active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) often produced substantial waste—sometimes exceeding 100 kilos per kilo of final product [3].

The 12 Principles of Green Chemistry: A Detailed Analysis

The 12 principles serve as complementary guidelines that address all phases of chemical product and process development, from initial molecular design to end-of-life considerations [2] [6]. They can be conceptually grouped into three overarching categories: resource efficiency, hazard reduction, and energy efficiency [7] [6]. The following sections provide a technical examination of each principle with particular emphasis on applications in pharmaceutical research and development.

Principle 1: Prevention

It is better to prevent waste than to treat or clean up waste after it has been created [3] [2].

This foundational principle emphasizes waste prevention rather than remediation. For drug development professionals, this means designing synthetic routes that minimize byproduct formation from the outset. The principle highlights that waste generation represents inefficiency and economic loss, with environmental consequences [3]. As noted by Berkeley W. Cue, Jr., this first principle is paramount, with the other principles serving as the "how to's" to achieve prevention [3].

Principle 2: Atom Economy

Synthetic methods should be designed to maximize incorporation of all materials used in the process into the final product [3] [2].

Atom economy, developed by Barry Trost, evaluates the efficiency of a synthesis by calculating what percentage of reactant atoms are incorporated into the final desired product [3]. This principle challenges researchers to look beyond traditional yield metrics and consider the fate of all atoms involved in a reaction.

Atom Economy Calculation: [ \text{Atom Economy (\%)} = \frac{\text{Molecular Weight of Desired Product}}{\text{Sum of Molecular Weights of All Reactants}} \times 100 ]

For example, even with a 100% yield, a reaction with 50% atom economy wastes half of the reactant mass as byproducts [3]. Maximizing atom economy is particularly crucial in pharmaceutical manufacturing, where complex syntheses often involve multiple steps with accumulating inefficiencies.

Principle 3: Less Hazardous Chemical Syntheses

Wherever practicable, synthetic methods should be designed to use and generate substances that possess little or no toxicity to human health and the environment [3].

This principle encourages the substitution of hazardous reagents with safer alternatives and the development of synthetic pathways that avoid toxic intermediates. The qualification "wherever practicable" acknowledges that completely non-toxic syntheses may not always be immediately achievable, but challenges researchers to continuously seek improvements [3]. As David J. C. Constable notes, chemists have traditionally focused on reaction success rather than the toxicity profile of all substances in the reaction flask, a mindset that requires transformation [3].

Principle 4: Designing Safer Chemicals

Chemical products should be designed to preserve efficacy of function while reducing toxicity [3].

This principle applies particularly to products like pharmaceuticals and agrochemicals that are designed to have biological activity. It requires understanding structure-activity relationships (SAR) and structure-toxicity relationships to maximize therapeutic effects while minimizing adverse impacts [3]. This approach represents a fundamental shift from risk management to hazard reduction at the design phase.

Principle 5: Safer Solvents and Auxiliaries

The use of auxiliary substances (e.g., solvents, separation agents) should be made unnecessary wherever possible and innocuous when used [3] [4].

Solvents often constitute the largest mass contribution in pharmaceutical syntheses and create significant waste streams [3]. This principle promotes solvent substitution (e.g., water or bio-based solvents for volatile organic compounds), solvent recovery systems, and solvent-free reactions where feasible.

Principle 6: Design for Energy Efficiency

Energy requirements of chemical processes should be recognized for their environmental and economic impacts and should be minimized [4] [5].

This principle encourages reactions at ambient temperature and pressure, improved heat transfer systems, and integration of energy-efficient technologies like microwave irradiation or ultrasound [2]. Energy consumption contributes significantly to the environmental footprint of chemical manufacturing, particularly in separation processes like distillation.

Principle 7: Use of Renewable Feedstocks

A raw material or feedstock should be renewable rather than depleting whenever technically and economically practicable [4] [5].

Renewable feedstocks include biomass, agricultural waste, carbon dioxide, and other biological materials that can be replenished, contrasting with finite petroleum resources [4]. The principle emphasizes using waste streams as feedstocks where possible, supporting circular economy models in chemical production.

Principle 8: Reduce Derivatives

Unnecessary derivatization (use of blocking groups, protection/deprotection, temporary modification of physical/chemical processes) should be minimized or avoided if possible [4] [5].

Derivatization requires additional reagents, generates waste, and increases process complexity. This principle promotes selective reactions, catalytic systems, and synthetic strategies that avoid protection/deprotection sequences common in complex molecule synthesis, such as for pharmaceuticals.

Principle 9: Catalysis

Catalytic reagents (as selective as possible) are superior to stoichiometric reagents [4] [5].

Catalysts increase efficiency, reduce energy requirements, and can enable alternative synthetic pathways with improved atom economy. This principle favors enzymatic, homogeneous, and heterogeneous catalysts over stoichiometric reagents, which generate more waste [7]. Catalytic processes are particularly valuable in pharmaceutical manufacturing where they can provide enhanced stereoselectivity and milder reaction conditions.

Principle 10: Design for Degradation

Chemical products should be designed so that at the end of their function they break down into innocuous degradation products and do not persist in the environment [4] [5].

This principle addresses concerns about bioaccumulation and persistence of chemicals in the environment. It requires consideration of a product's entire life cycle, including its disposal phase [4]. For pharmaceuticals, this must be balanced with stability requirements for efficacy.

Principle 11: Real-time Analysis for Pollution Prevention

Analytical methodologies need to be further developed to allow for real-time, in-process monitoring and control prior to the formation of hazardous substances [4] [5].

This principle emphasizes process analytical technology (PAT) to enable continuous monitoring and immediate correction of process deviations, preventing hazardous substance formation and improving quality control [5]. Advanced analytical techniques allow for more precise reaction control and early detection of byproduct formation.

Principle 12: Inherently Safer Chemistry for Accident Prevention

Substances and the form of a substance used in a chemical process should be chosen to minimize the potential for chemical accidents, including releases, explosions, and fires [4] [5].

This final principle focuses on physical hazards and process safety, encouraging the selection of less hazardous materials and operating conditions to minimize risk [5]. It represents the culmination of the other principles by creating inherently safer systems rather than relying on add-on safety features.

Quantitative Frameworks for Assessing Green Chemistry

While the 12 principles provide qualitative guidance, quantitative metrics are essential for objective assessment, comparison, and continuous improvement of chemical processes [7] [2]. Several established metrics and emerging comprehensive systems enable researchers to measure and optimize the greenness of their syntheses.

Fundamental Green Chemistry Metrics

Table 1: Core Quantitative Metrics for Green Chemistry Assessment

| Metric | Calculation | Ideal Value | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| E-Factor [2] | (\displaystyle \text{E-Factor} = \frac{\text{Mass of Waste (kg)}}{\text{Mass of Product (kg)}}) | 0 (lower is better) | Overall process environmental impact; Pharmaceutical industry range: 25-100 [3] |

| Process Mass Intensity (PMI) [3] [2] | (\displaystyle \text{PMI} = \frac{\text{Total Mass in Process (kg)}}{\text{Mass of Product (kg)}}) | 1 (lower is better) | Includes all materials: reactants, solvents, process aids; Preferred by ACS GCIPR [3] |

| Atom Economy [3] [2] | (\displaystyle \text{Atom Economy} = \frac{\text{MW of Desired Product}}{\text{Sum of MW of All Reactants}} \times 100\%) | 100% (higher is better) | Theoretical maximum efficiency of a reaction; Does not account for yield or solvents [3] |

| EcoScale [2] | 100 - penalty points (yield, cost, safety, setup, temperature/time, workup) | 100 (higher is better) | Holistic assessment incorporating practical and safety considerations [2] |

DOZN 2.0: A Comprehensive Quantitative Evaluation System

DOZN 2.0 is a web-based quantitative green chemistry evaluator that systematically assesses compliance with all 12 principles [7] [6]. Developed by MilliporeSigma, this tool groups the principles into three overarching categories and calculates scores from 0-100 (with 0 being most desirable) based on readily available data including manufacturing inputs, GHS classifications, and Safety Data Sheet information [7].

The system enables direct comparison between alternative chemicals or synthetic routes for the same application, providing researchers with a transparent framework for decision-making [7] [6]. As demonstrated in the evaluation of 1-Aminobenzotriazole processes, DOZN can quantify improvements from process re-engineering, with the aggregate score decreasing from 93 (original process) to 46 (re-engineered process) [7].

Table 2: DOZN 2.0 Category Grouping and Scoring Example for 1-Aminobenzotriazole

| Category | Related Principles | Original Process Score | Re-engineered Process Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Improved Resource Use | Prevention, Atom Economy, Renewable Feedstocks, Reduce Derivatives, Catalysis, Real-time Analysis | 2214 (Principle 1) 752 (Principle 2) 752 (Principle 7) 0.0 (Principle 8) 0.5 (Principle 9) 1.0 (Principle 11) | 717 (Principle 1) 251 (Principle 2) 251 (Principle 7) 0.0 (Principle 8) 1.0 (Principle 9) 1.0 (Principle 11) |

| Increased Energy Efficiency | Design for Energy Efficiency | 2953 | 1688 |

| Reduced Human and Environmental Hazards | Less Hazardous Chemical Synthesis, Designing Safer Chemicals, Safer Solvents, Design for Degradation, Inherently Safer Chemistry | 1590 (Principle 3) 7.1 (Principle 4) 2622 (Principle 5) 2.3 (Principle 10) 1138 (Principle 12) | 1025 (Principle 3) 9.1 (Principle 4) 783 (Principle 5) 2.8 (Principle 10) 322 (Principle 12) |

| Aggregate Score | Average of all categories | 93 | 46 |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Implementing green chemistry principles requires both strategic design and practical experimental techniques. This section outlines methodologies for applying green chemistry in pharmaceutical research and development.

Green Chemistry Experimental Workflow

Protocol: Atom Economy Calculation and Analysis

Purpose: To evaluate the inherent efficiency of a synthetic reaction and identify opportunities for improvement.

Materials:

- Molecular structures and weights of all reactants and desired product

- Reaction equation balanced for stoichiometry

Procedure:

- Write the balanced chemical equation for the reaction.

- Calculate the molecular weight of the desired product.

- Calculate the sum of molecular weights for all reactants based on stoichiometric ratios.

- Apply the atom economy formula: [ \text{Atom Economy} = \frac{\text{Molecular Weight of Desired Product}}{\text{Sum of Molecular Weights of All Reactants}} \times 100\% ]

- Interpret results:

- >90%: Excellent atom economy

- 70-90%: Good atom economy

- <50%: Poor atom economy; consider alternative routes

- Identify atoms not incorporated into the final product and assess their environmental impact.

Example Calculation: For the reaction ( \text{CH}4 + \text{Cl}2 \rightarrow \text{CH}_3\text{Cl} + \text{HCl} ):

- Molecular weight of desired product (CH₃Cl): 50.49 g/mol

- Sum of molecular weights of reactants (CH₄ + Cl₂): 16.04 g/mol + 70.90 g/mol = 86.94 g/mol

- Atom Economy = (50.49 / 86.94) × 100% = 58.1% [4]

Protocol: Process Mass Intensity (PMI) Determination

Purpose: To quantify the total mass of materials required to produce a unit mass of product, enabling comparison of process efficiency.

Materials:

- Mass data for all input materials (reactants, solvents, catalysts, processing aids)

- Mass of isolated product

Procedure:

- Conduct the synthetic process and record the mass of all materials used.

- Isolate and dry the final product, recording its mass.

- Calculate PMI using the formula: [ \text{PMI} = \frac{\text{Total Mass of All Input Materials (kg)}}{\text{Mass of Product (kg)}} ]

- For multi-step syntheses, calculate PMI for each step and the overall process.

- Compare with industry benchmarks:

- Pharmaceutical industry: 25-100+ (traditional processes)

- Improved pharmaceutical processes: <25

- Bulk chemicals: <5

- Identify major contributors to mass intensity and target for optimization.

Case Study: Sertraline Process Redesign

Pfizer's redesign of the sertraline manufacturing process demonstrates multiple green chemistry principles in practice [3]. The original process used large quantities of organic solvents, generated significant waste, and required multiple isolation steps. The redesigned process:

- Applied Principle 1 (Prevention): Reduced waste by 76% through solvent optimization and recycling

- Applied Principle 5 (Safer Solvents): Replaced tetrahydrofuran, a hazardous solvent, with ethanol

- Applied Principle 9 (Catalysis): Improved catalyst efficiency and recovery

- Applied Principle 2 (Atom Economy): Increased overall material utilization

This redesign resulted in approximately 330 tons of waste reduction annually while maintaining product quality, demonstrating the economic and environmental benefits of systematic green chemistry application [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Implementing green chemistry principles requires both strategic approaches and specific technical solutions. The following table outlines key technologies and methodologies that support green chemistry in pharmaceutical research and development.

Table 3: Green Chemistry Research Reagent Solutions and Technologies

| Technology/Solution | Function | Green Chemistry Principles Addressed |

|---|---|---|

| Biocatalysts & Enzymes [3] | Highly selective catalytic proteins for specific transformations | Principle 3 (Less Hazardous Synthesis), Principle 6 (Energy Efficiency), Principle 9 (Catalysis) |

| Supercritical CO₂ Extraction [5] | Uses supercritical CO₂ as non-toxic replacement for organic solvents | Principle 5 (Safer Solvents), Principle 12 (Accident Prevention) |

| Microwave-Assisted Synthesis [2] | Accelerates reactions through efficient energy transfer | Principle 6 (Design for Energy Efficiency), Principle 3 (Less Hazardous Synthesis) |

| Flow Chemistry Systems | Enables continuous processing with improved heat transfer and safety | Principle 12 (Inherently Safer Chemistry), Principle 11 (Real-time Analysis) |

| Bio-based Solvents [5] | Renewable solvents from biomass (e.g., 2-methyltetrahydrofuran) | Principle 7 (Use of Renewable Feedstocks), Principle 5 (Safer Solvents) |

| Process Analytical Technology (PAT) [5] | Real-time monitoring of reactions to prevent byproduct formation | Principle 11 (Real-time Analysis for Pollution Prevention) |

| Heterogeneous Catalysts [7] | Recoverable catalysts that minimize metal contamination | Principle 9 (Catalysis), Principle 3 (Less Hazardous Synthesis) |

Implementation in Pharmaceutical Research and Development

The pharmaceutical industry faces particular challenges in implementing green chemistry due to complex molecular structures, rigorous regulatory requirements, and the need for high purity [3]. However, significant progress has been made through systematic application of the principles.

The ACS Green Chemistry Institute Pharmaceutical Roundtable has championed green chemistry in the industry, focusing on metrics like process mass intensity to drive continuous improvement [3]. Notable successes include:

- Codexis, Inc. and Professor Yi Tang's Biocatalytic Process for Simvastatin: Developed an efficient enzymatic process that replaced hazardous reagents and reduced waste [3].

- Pfizer's Sertraline Redesign: Achieved substantial waste reduction through solvent optimization and improved catalysis [3].

- Biocatalytic Processes: Increasing use of engineered enzymes for asymmetric syntheses that provide high selectivity under mild conditions [3].

For drug development professionals, integrating green chemistry considerations early in process development is crucial. This includes:

- Evaluating multiple synthetic routes using green metrics during route selection

- Considering life cycle impacts of starting materials and reagents

- Designing purification methods that minimize solvent use and enable recycling

- Incorporating degradation studies into API characterization

The DOZN system provides a valuable framework for comparing alternative syntheses and demonstrating green chemistry improvements to regulatory agencies and stakeholders [7] [6].

The 12 Principles of Green Chemistry provide a comprehensive, systematic framework for designing chemical products and processes that minimize environmental impact while maintaining economic viability [3] [4] [5]. For researchers and drug development professionals, these principles offer a strategic approach to addressing the complex challenges of sustainable pharmaceutical development.

Quantitative assessment tools like atom economy, PMI, E-factor, and comprehensive systems like DOZN enable objective evaluation and continuous improvement of chemical processes [3] [7] [2]. The integration of these metrics into research and development workflows provides a pathway for implementing green chemistry principles in practical laboratory and manufacturing settings.

As the chemical industry evolves toward greater sustainability, the 12 principles continue to guide innovation in synthetic methodologies, solvent systems, energy efficiency, and product design [5]. For curriculum development, these principles represent essential core competencies that prepare the next generation of chemists and researchers to meet the challenges of sustainable drug development and manufacturing.

Green chemistry, defined as the design of chemical products and processes that reduce or eliminate the use and generation of hazardous substances, has evolved from a pollution prevention philosophy into a comprehensive framework for achieving global sustainability targets [8]. The field emerged in the 1990s through the work of Paul Anastas and John Warner, who formulated the 12 Principles of Green Chemistry, providing a systematic approach to designing safer, more efficient chemical processes [9]. This technical guide examines how these principles align with and actively advance the objectives of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the European Green Deal, creating a powerful synergy between molecular design and global policy frameworks.

The urgency of this integration is underscored by projections that global chemical production will double by 2030, creating unprecedented challenges for environmental protection and resource management [10]. Within this context, green chemistry provides the methodological foundation and practical tools for transforming chemical innovation into a driving force for sustainability rather than a source of pollution. This whitepaper explores the technical frameworks, experimental methodologies, and policy interfaces that connect green chemistry principles to these overarching global agendas, with particular focus on their application in pharmaceutical development and industrial chemistry.

Policy Frameworks: The EU Green Deal and UN SDGs

The European Green Deal and Chemicals Strategy for Sustainability

The European Green Deal (EGD), launched in 2019, represents the EU's comprehensive strategy to transform into a modern, resource-efficient, and competitive economy with no net emissions of greenhouse gases by 2050 [11]. As part of this framework, the Chemicals Strategy for Sustainability (CSS) aims to create a "toxic-free environment" by encouraging innovation in the chemical sector and addressing the complete lifecycle of chemicals [12]. The CSS adopts essential green chemistry concepts, particularly the "Safe and Sustainable by Design" (SSbD) framework, which aligns with the prevention-based philosophy of green chemistry [10].

The EGD employs a systemic approach to chemical management, seeking to simplify and strengthen the EU's regulatory framework through initiatives such as "one substance - one assessment" to streamline chemical reviews [13]. This strategy explicitly addresses the interface between chemicals, products, and waste legislation, recognizing that holistic management requires integrated policy approaches. The EU project "IRISS" (The international ecosystem for accelerating the transition to Safe-and-Sustainable-by-design materials, products and processes) exemplifies this approach, establishing Europe-wide networks across the textile and plastics industries to promote SSbD methodologies [10].

Alignment with UN Sustainable Development Goals

Machine learning analysis of EGD policy documents has quantified strong alignment between the European Green Deal and specific UN SDGs, particularly SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), SDG 13 (Climate Action), and SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy) [11]. This alignment demonstrates how regional chemical policy initiatives can directly contribute to global sustainability frameworks. The analysis reveals that EGD policies show particularly strong correlation with SDG 12, reflecting the Circular Economy Action Plan's emphasis on sustainable resource management and waste reduction [11].

Table 1: Primary SDG Alignment with Green Chemistry Applications

| Sustainable Development Goal | Relevance to Green Chemistry | Exemplary Applications |

|---|---|---|

| SDG 12: Responsible Consumption & Production | Atom economy, waste prevention, renewable feedstocks | Biorenewable chemistries, catalytic processes, circular material flows |

| SDG 13: Climate Action | Energy efficiency, CO₂ utilization, alternative syntheses | Supercritical CO₂ processes, microwave-assisted synthesis, carbon capture |

| SDG 9: Industry, Innovation & Infrastructure | Sustainable chemical technologies, green engineering | Continuous flow chemistry, process intensification, green nano-technology |

| SDG 6: Clean Water & Sanitation | Pollution prevention, benign degradation | Green analytical methods, biodegradable chemical design, water treatment |

| SDG 3: Good Health & Well-being | Safer chemicals, reduced toxicity | Pharmaceutical green chemistry, benign solvent substitution, toxicology |

The interconnection between these frameworks demonstrates how green chemistry serves as an implementation bridge between high-level policy goals and practical chemical innovation. The following diagram illustrates the conceptual relationship between these frameworks and green chemistry principles:

Technical Implementation: Green Chemistry Principles and Methodologies

The 12 Principles of Green Chemistry as a Design Framework

The 12 Principles of Green Chemistry provide a comprehensive framework for aligning chemical research and development with sustainability goals [9]. These principles emphasize waste prevention, atom economy, reduced hazard, safer chemicals and products, benign solvents, energy efficiency, renewable feedstocks, reduced derivatives, catalysis, degradation, real-time analysis, and accident prevention [8]. When systematically applied, these principles create a multiplicative effect for advancing SDG targets, particularly those related to responsible consumption and production (SDG 12), climate action (SDG 13), and life below water (SDG 14).

The principle of atom economy (Principle 2) demonstrates this alignment particularly well. Atom economy measures the incorporation of starting materials into the final product, with ideal reactions achieving 100% incorporation. The Diels-Alder reaction, for example, represents a theoretically perfect atom-economic transformation where all atoms from the reactants are incorporated into the final product [9]. This principle directly supports SDG 12 by minimizing waste generation and optimizing resource efficiency throughout the chemical lifecycle.

Experimental Protocols in Green Chemistry

Green Synthesis of 2-Aminobenzoxazoles Under Metal-Free Conditions

Objective: To demonstrate a sustainable alternative to transition metal-catalyzed C–H amination reactions, eliminating toxic metal catalysts while maintaining high efficiency [14].

Methodology:

- Reaction Setup: In a round-bottom flask equipped with a magnetic stir bar, combine benzoxazole (1.0 mmol) and amine component (1.2 mmol) in a green solvent system.

- Catalyst System: Add tetrabutylammonium iodide (TBAI, 10 mol%) as the metal-free catalyst.

- Oxidation: Introduce aqueous tert-butyl hydroperoxide (TBHP, 2.0 mmol) as the oxidant.

- Reaction Conditions: Stir the reaction mixture at 80°C for 4-8 hours under air atmosphere.

- Monitoring: Track reaction progress by TLC or GC-MS until complete consumption of starting material.

- Work-up: Dilute the reaction mixture with ethyl acetate (10 mL) and wash with water (3 × 5 mL).

- Purification: Purify the crude product by flash chromatography using silica gel with hexane/ethyl acetate as eluent.

Green Chemistry Advantages:

- Eliminates copper, silver, manganese, iron, or cobalt catalysts traditionally required for C–H amination

- Utilizes benign oxidation conditions with high atom economy

- Achieves yields of 82-97%, comparable to traditional methods

- Reduces heavy metal contamination in products and waste streams

Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Plant Extracts

Objective: To develop an environmentally benign synthesis of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) using plant-derived biomolecules as reducing and stabilizing agents, replacing toxic chemical reagents [9].

Methodology:

- Plant Extract Preparation: Macerate 10 g of fresh plant material (e.g., leaf, root, or fruit peel) in 100 mL deionized water. Heat at 60°C for 30 minutes, then filter through Whatman No. 1 filter paper.

- Reaction Setup: Add 1 mL of plant extract to 9 mL of aqueous silver nitrate solution (1 mM) in a sterile vial.

- Synthesis Conditions: Incubate the mixture at room temperature with continuous shaking (120 rpm) for 24 hours in the dark.

- Monitoring: Observe color change from pale yellow to reddish-brown, indicating nanoparticle formation. Confirm synthesis by UV-Vis spectroscopy with scanning between 300-600 nm.

- Characterization: Analyze nanoparticle size and distribution using dynamic light scattering (DLS) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM).

- Purification: Centrifuge the nanoparticle suspension at 15,000 rpm for 30 minutes, then redisperse the pellet in deionized water.

Green Chemistry Advantages:

- Replaces toxic reducing agents (e.g., sodium borohydride) with natural plant metabolites

- Eliminates synthetic capping agents through natural biomolecule stabilization

- Utilizes aqueous conditions at ambient temperature, reducing energy requirements

- Produces biocompatible nanoparticles with enhanced antimicrobial properties

Table 2: Green Chemistry Metrics for Sustainable Nanomaterial Synthesis

| Metric | Traditional Synthesis | Green Synthesis | SDG Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy Consumption | High-temperature processes (>100°C) | Room temperature or mild heating | SDG 7: Affordable & Clean Energy |

| Reagent Hazard | Toxic reducing agents (NaBH₄, N₂H₄) | Plant extracts, biodegradable agents | SDG 12: Responsible Consumption |

| Solvent System | Organic solvents (toluene, THF) | Aqueous solutions | SDG 6: Clean Water & Sanitation |

| By-product Toxicity | Hazardous chemical waste | Biodegradable compounds | SDG 14: Life Below Water |

| Process Safety | Explosion, fire hazards | Benign, aqueous conditions | SDG 8: Decent Work & Economic Growth |

Green Chemistry in Pharmaceutical Development and Industrial Applications

Integration with Quality by Design (QbD) in Pharmaceutical Chemistry

The pharmaceutical industry has pioneered the integration of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) with Quality by Design (QbD) methodologies to develop robust, environmentally sustainable analytical methods [15]. This integration applies green chemistry principles to analytical techniques, particularly chromatography, by focusing on solvent reduction, method miniaturization, and waste minimization. The Analytical Quality by Design (AQbD) framework systematically incorporates environmental sustainability as a key method attribute, aligning with the preventive philosophy of green chemistry [15].

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) method development exemplifies this integration, where QbD principles identify critical method parameters (e.g., mobile phase composition, column temperature, flow rate) while GAC principles guide the selection of greener alternatives to traditional acetonitrile-based mobile phases [15]. Methodologies include:

- Solvent substitution replacing acetonitrile with ethanol or methanol in reversed-phase HPLC

- Method miniaturization using UHPLC and capillary columns to reduce solvent consumption by 80-90%

- Greenness assessment tools including HPLC-EAT, GAPI, and Analytical Eco-Scale to quantify environmental impact

Industrial Case Studies and Sustainable Technology

PFAS Substitution in Metal Plating Industry

A comprehensive case study from the New York State Pollution Prevention Institute demonstrates the application of green chemistry principles to eliminate per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) from metal plating operations [16]. The project identified a PFAS-based fume suppressant as a source of persistent environmental contaminants and systematically evaluated alternatives based on:

- Chemical Hazard Assessment using the ChemFORWARD platform to identify safer alternatives

- Performance Validation through industrial-scale testing of alternative chemistries

- Lifecycle Considerations including degradation products and end-of-life management

- Economic Analysis evaluating cost implications of chemical substitution

The successful implementation of a safer alternative demonstrates the practical application of green chemistry principles in an industrial context, directly contributing to SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure) and SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production) [16].

Bio-based Solvents and Renewable Feedstocks

The transition from petroleum-derived solvents to bio-based alternatives represents a significant advancement in industrial green chemistry. Examples include:

- Ethyl lactate derived from corn fermentation as a replacement for halogenated solvents

- Eucalyptol from renewable plant sources as a sustainable solvent for organic synthesis

- Dimethyl carbonate (DMC) as a green methylating agent replacing toxic methyl halides and dimethyl sulfate [14]

- Polyethylene glycol (PEG) as a recyclable reaction medium for heterocyclic compound synthesis

The following workflow illustrates the integration of green chemistry principles throughout research and development processes:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents and Methodologies

Table 3: Essential Green Chemistry Reagents and Their Applications

| Reagent/Methodology | Function | Traditional Alternative | Green Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dimethyl Carbonate (DMC) | Green methylating agent | Dimethyl sulfate, methyl halides | Biodegradable, non-toxic, renewable production |

| Ionic Liquids (e.g., [BPy]I) | Reaction medium & catalyst | Volatile organic solvents | Negligible vapor pressure, recyclable, tunable properties |

| Plant Extracts (e.g., pineapple juice, onion peel) | Biocatalysts & reducing agents | Synthetic catalysts, toxic reducing agents | Renewable, biodegradable, non-hazardous |

| Water & Supercritical CO₂ | Green solvents | Organic solvents (hexane, toluene) | Non-toxic, non-flammable, naturally abundant |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Polymer-supported solvent | Volatile organic compounds | Recyclable, non-volatile, biocompatible |

| TBHP/H₂O₂ | Green oxidants | Heavy metal oxidants | Water as byproduct, reduced toxicity |

| TBAI | Metal-free catalyst | Transition metal catalysts | Avoids heavy metal contamination, lower cost |

Assessment and Metrics: Evaluating Green Chemistry Performance

The implementation of green chemistry principles requires robust metrics to evaluate environmental and sustainability performance. Multiple assessment tools have been developed to quantify the "greenness" of chemical processes and align them with SDG targets:

Process Mass Intensity (PMI) measures the total mass of materials used to produce a unit mass of product, directly supporting SDG 12 targets for sustainable consumption [9]. Pharmaceutical industry data demonstrates that green chemistry innovations can reduce PMI by 50-80% compared to traditional processes.

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) methodologies evaluate the environmental impact of chemicals and processes across their entire lifecycle, from raw material extraction to end-of-life disposal. This comprehensive approach aligns with the EU Chemicals Strategy's emphasis on lifecycle thinking and supports multiple SDGs through systematic impact evaluation [12].

Greenness Assessment Tools for Analytical Methods including the Analytical Eco-Scale and AGREE metrics provide quantitative scoring for the environmental performance of analytical methods, encouraging the adoption of greener alternatives in quality control and research laboratories [15].

Green chemistry provides the fundamental scientific and technical foundation for achieving the ambitious sustainability targets outlined in the UN SDGs and EU Green Deal. The principles of green chemistry align systematically with global policy frameworks, creating a synergistic relationship between molecular design and sustainability objectives. The experimental methodologies and assessment tools discussed in this whitepaper demonstrate the practical implementation of this alignment across pharmaceutical development, industrial chemistry, and materials science.

Future advancements will require strengthened collaboration between chemists, toxicologists, policymakers, and industry stakeholders to develop the robust scientific foundation needed to support these ambitious sustainability goals. As chemical production continues to grow globally, the integration of green chemistry principles into research, education, and industrial practice becomes increasingly essential for achieving a sustainable, non-toxic environment and circular economy. The technical protocols and methodologies outlined in this document provide a roadmap for researchers and drug development professionals to contribute meaningfully to these global sustainability initiatives through the practical application of green chemistry principles.

The pharmaceutical industry, responsible for approximately 5% of global greenhouse gas emissions, is facing a strategic imperative to integrate sustainability into its core operations [17] [18] [19]. This whitepaper delineates the compelling business case for adopting green chemistry and sustainable practices, demonstrating that environmental responsibility is not merely a regulatory burden but a powerful driver of economic viability, innovation, and competitive advantage. Framed within the context of developing green chemistry core competencies, this document provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a technical roadmap for implementing sustainable methodologies that reduce resource consumption, minimize waste, and ultimately contribute to a healthier planet without compromising product quality or efficacy.

The Multifaceted Drivers for Sustainability

The push for sustainability in the pharmaceutical sector is fueled by a convergence of regulatory, economic, environmental, and social factors. Understanding these drivers is essential for building a robust business case.

Regulatory and Stakeholder Pressure

Globally, regulatory bodies are escalating their demands for environmental accountability. The World Health Organization (WHO) has issued a call for action, urging the transformation of regulatory practices to reduce the environmental footprint of medical products [18]. This aligns with the EU Chemicals Strategy and the Zero Pollution Action Plan, which set stringent requirements for the entire lifecycle of pharmaceuticals [20]. Simultaneously, investors are increasingly applying Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) criteria, and consumers are showing a preference for ethically produced medicines, making transparency and sustainability critical for maintaining brand value and investor appeal [21] [22] [19].

Economic Imperatives and the "Triple Bottom Line"

The integration of sustainability is a strategic lever for achieving the "triple bottom line" of environmental health, social well-being, and economic prosperity [22]. The pharmaceutical industry's traditional linear production model is notoriously inefficient, with an E-factor (ratio of waste to product) ranging from 25 to over 100, meaning up to 100 kg of waste is generated for every 1 kg of active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) produced [20]. Solvents alone can constitute 80-90% of the total mass used in API manufacturing [20]. Adopting green chemistry principles directly addresses this by:

- Reducing costs associated with raw materials, hazardous waste disposal, and energy consumption [22].

- Driving innovation and creating a competitive edge by developing more efficient, synthetically elegant processes [22] [19].

- Mitigating risk by proactively adapting to evolving environmental regulations, thus avoiding potential fines and legal challenges [22].

Table 1: The Triple Bottom Line of Sustainable Pharma

| Dimension | Key Aspect | Business Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental Sustainability | Reduced pollution & waste, lower resource consumption, climate change mitigation | Lower disposal costs, reduced resource volatility, compliance with regulations [22] |

| Social Sustainability | Increased worker safety, improved public health & perception, ethical sourcing | Enhanced employer brand, stronger community relations, reduced liability [22] |

| Economic Sustainability | Long-term cost reduction, innovation & competitive advantage, reduced regulatory burden | Improved profitability, market differentiation, resilient operations [22] |

Environmental Urgency and Corporate Responsibility

The sector's significant environmental footprint—contributing to climate change, water scarcity, and biodiversity loss—has precipitated an environmental reckoning [17]. A roadmap from the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD) identifies five key priority actions for the industry, which have been adapted below [17]:

Table 2: Key Environmental Priorities for the Pharmaceutical Sector

| Priority Action | Description | Example Company Initiatives |

|---|---|---|

| Minimizing Water Usage | Adopting water conservation strategies and advanced treatment protocols. | Sanofi reduced global water withdrawals by 18% via recycling systems [19]. |

| Addressing API Pollution | Mitigating risks from Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients in ecosystems. | Implementing improved disposal methods and cleaner production tech [17]. |

| Reducing GHG Emissions | Setting ambitious targets for Scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions. | Pfizer aims for net zero by 2040; Novo Nordisk for zero environmental impact by 2045 [21] [23]. |

| Improving Supply Chain Transparency | Ensuring traceability and responsible sourcing of raw materials. | Astellas Pharma's SOAR model enhances supply chain governance and visibility [24]. |

| Cutting Solid Waste | Investing in circular economy initiatives for packaging and production. | Novo Nordisk's "Circular for Zero" aims to eliminate waste across product lifecycles [21]. |

Green Chemistry as a Foundational Competency

Green chemistry, defined as "the design of chemical products and processes that reduce or eliminate the use or generation of hazardous substances," provides the foundational framework for achieving these sustainability goals [23] [22]. Its twelve principles serve as a strategic roadmap for innovation in pharmaceutical R&D and manufacturing [25] [23] [22].

Technical Implementation: Core Strategies and Methodologies

The practical application of green chemistry principles is revolutionizing pharmaceutical synthesis and analysis. Below are detailed methodologies being adopted by industry leaders.

Sustainable Synthesis Pathways

- Advanced Catalysis: Employing catalytic reagents that are superior to stoichiometric reagents is a cornerstone of green chemistry [25]. This includes:

- Biocatalysis: Using enzymes as nature's optimal catalysts. Boehringer Ingelheim has established a dedicated biocatalysis hub, following a workflow of enzyme screening, engineering, and reaction optimization to develop greener processes [26]. For instance, thiamine-dependent enzymes have been repurposed using photo/electrochemical regulation to enable asymmetric radical reactions, achieving yields of 59% to 92% with high enantioselectivity [26].

- Photoredox Catalysis: Prof. Corey Stephenson's team (UBC) has established photoredox catalysis as a universal method for organic radical generation. To overcome scale-up challenges where light penetration is insufficient, they adopted small-bore continuous flow reactors, enabling kilogram-scale radical trifluoromethylation with isolated yields of 60–65% [26].

- Continuous Flow Manufacturing: Transitioning from traditional batch processes to continuous flow is a form of process intensification that offers significant green advantages, including improved safety, higher efficiency, and reduced waste [22] [26]. PharmaBlock, a CDMO, has won awards for innovations like continuous flow processes, which allow for safer and more environmentally friendly scalable production [26].

- Microwave-Assisted Synthesis: This technique uses microwave irradiation to dramatically accelerate organic reactions, completing them in minutes rather than hours or days [20]. It offers benefits such as rapid volumetric heating, high product yield, and easy purification. For example, synthesizing heterocyclic compounds like oxadiazole derivatives via microwave irradiation provides remarkably short reaction times and high yields compared to conventional methods [20]. The methodology requires the use of polar, high-boiling point solvents (e.g., DMF, ethanol) that effectively absorb microwave energy [20].

Green Analytical Chemistry

In pharmaceutical analysis, the sample preparation step is often the most polluting. Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) principles are applied to minimize this impact [25].

- Direct Chromatography: Avoiding sample pre-treatment altogether for clean matrices, thereby eliminating consumption of organic solvents and sorbents [25].

- Miniaturization and Solvent Reduction: In Liquid Chromatography (LC), reducing the internal diameter of the column allows for a lower mobile phase flow rate, which minimizes solvent consumption and waste output while improving analytical sensitivity [25]. Temperature optimization can also be leveraged to affect selectivity and efficiency, reducing the need for solvent changes [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and technologies enabling the implementation of green chemistry in pharmaceutical research and development.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Green Chemistry

| Reagent/Technology | Function in Sustainable Pharma | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Enzymes (Biocatalysts) | Highly selective, biodegradable catalysts that operate under mild conditions. | Boehringer Ingelheim uses engineered enzymes for asymmetric synthesis, reducing synthetic steps [26]. |

| Visible-Light Photocatalysts | Catalyze reactions using visible light, a renewable energy source, often enabling novel radical pathways. | Used in kilogram-scale trifluoromethylation reactions in continuous flow reactors [26]. |

| Nickel Catalysts | Abundant, cheaper, and less toxic alternative to precious metals like palladium and platinum. | Pfizer has adopted nickel to aid in chemical bond formation, reducing waste and cost [23]. |

| Next-Generation Green Solvents | Safer alternatives to traditional hazardous solvents; include ionic liquids, supercritical fluids, and superheated water. | Replacing toxic solvents in sample preparation and synthesis to minimize environmental and health impacts [25] [22]. |

| Continuous Flow Reactors | Miniaturized reactors that enhance heat/mass transfer, improve safety, and reduce solvent and energy use. | PharmaBlock employs continuous flow for safer, lower-carbon scalable API production [26]. |

Quantitative Impact and Future Outlook

Measuring Success and Performance Metrics

The adoption of green chemistry and sustainable practices yields measurable benefits. For instance, one implementation at Pfizer was linked to a 19% reduction in waste and a 56% improvement in productivity compared to previous production standards [23] [19]. Furthermore, investments in facility sustainability can have a rapid payback; one pharmaceutical facility used a $10 million capital investment to cut Scope 1 emissions by 67% within a year, saving over $1 million annually in operating expenses [24].

Leading companies are already demonstrating strong performance on sustainability metrics:

- Novo Nordisk reported a carbon productivity of $1,035,533, the highest among its peers, indicating high economic output relative to carbon emissions [21].

- Eisai Co. and Sanofi have also reported strong carbon productivity of $159,088 and $154,001, respectively [21].

Emerging Trends and the Role of Digitalization

The future of sustainable pharma will be shaped by several key trends and technologies:

- Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning (AI/ML): AI is poised to play a pivotal role in predictive toxicology, automated reaction optimization, and sustainable supply chain management [22] [19]. For example, PharmaBlock is leveraging AI to directly identify candidate molecules from protein targets, shortening discovery cycles [26]. However, the environmental footprint of AI itself, due to high electricity and water consumption, must be carefully considered [19].

- Circular Economy Principles: Companies are increasingly harnessing biobased feedstocks and exploring waste valorization to create closed-loop systems, moving beyond traditional linear "take-make-dispose" models [22] [19].

- Collaborative Frameworks: Success depends on cross-sector collaboration. Initiatives like the joint action by AstraZeneca, GSK, Merck KGaA, Novo Nordisk, Roche, Samsung Biologics, and Sanofi to decarbonize clinical trials exemplify the industry-wide effort required [19].

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between the primary business drivers, the core green chemistry strategies, and the resulting strategic outcomes for a pharmaceutical company.

Business Drivers and Strategic Outcomes in Sustainable Pharma

The business case for sustainability in the pharmaceutical industry is unequivocal. It is a multifaceted strategy that addresses critical regulatory, economic, and environmental challenges while simultaneously driving innovation and securing long-term profitability. By embedding the twelve principles of green chemistry into the core competencies of drug discovery, development, and manufacturing, companies can significantly reduce their environmental footprint, minimize waste and costs, and enhance their societal license to operate. The journey toward a sustainable pharmaceutical sector is complex and requires concerted effort across academia, industry, and regulatory bodies, but it is an essential and strategic imperative for shaping a healthier future for both people and the planet.

In the pursuit of sustainable chemical practices, green chemistry metrics provide indispensable tools for quantifying the efficiency and environmental performance of chemical processes [27]. These metrics serve as critical indicators for researchers and industrial chemists, enabling objective comparison between alternative synthetic pathways and providing a measurable framework for the principles of green chemistry [27] [28]. For the pharmaceutical industry and drug development professionals, the adoption of these metrics is particularly crucial. It facilitates the design of manufacturing processes that minimize waste, reduce energy consumption, and diminish environmental impact, thereby aligning scientific innovation with ecological and economic sustainability [27] [28]. This guide details three core competencies—Atom Economy, E-Factor, and Life Cycle Thinking—providing a technical foundation for their calculation, application, and integration into a comprehensive green chemistry curriculum.

Atom Economy

Theoretical Foundation and Calculation

Atom economy is a foundational metric in green chemistry, conceived by Barry M. Trost in 1991 [29] [27]. It measures the efficiency of a reaction by calculating what proportion of the mass of the reactants ends up in the final desired product [30]. A reaction with a high atom economy maximizes the incorporation of starting materials into the product, thereby minimizing waste generation at the molecular level [27].

The standard formula for calculating atom economy is:

Atom economy = (Molecular weight of desired product / Sum of molecular weights of all reactants) × 100% [29] [27] [31]

For multi-step syntheses, the calculation must include all reactants from every step leading to the final product [27]. It is vital to use a fully balanced chemical equation and to multiply the molecular weight of each substance by its respective stoichiometric coefficient [29].

Table 1: Example Atom Economy Calculations

| Reaction Example | Balanced Equation | Mr of Reactants | Mr of Desired Product | Atom Economy | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethanol Production (Addition) | C₂H₄ + H₂O → C₂H₅OH | (28.05 + 18.02) = 46.07 g/mol | 46.07 g/mol | 100% [29] | Ideal; all atoms in reactants are incorporated into the desired product. |

| Ethanol Production (Fermentation) | C₆H₁₂O₆ → 2C₂H₅OH + 2CO₂ | 180.16 g/mol | 2 × 46.07 = 92.14 g/mol | 51.14% [29] [30] | Moderate; nearly half the mass of reactants is wasted in a by-product. |

| Haber Process | N₂ + 3H₂ → 2NH₃ | 28 + (3×2) = 34 g/mol | 2 × 17 = 34 g/mol | 100% [30] | Ideal atom economy, though reaction kinetics and equilibrium pose practical challenges [30]. |

| Hydrogen Production | CH₄ + H₂O → CO + 3H₂ | (16.04 + 18.02) = 34.06 g/mol | 3 × (2×1) = 6 g/mol | 17.6% [29] [31] | Low; most of the reactant mass ends up in the CO by-product. |

Experimental Protocol and Methodology

Objective: To determine the atom economy of a chosen synthetic reaction. Principle: Atom economy is a theoretical metric calculated from the balanced chemical equation, independent of laboratory results. It provides an upper limit for the efficiency of a reaction under ideal conditions [27].

Procedure:

- Reaction Selection: Identify the balanced chemical equation for the synthesis, including all reactants and products.

- Data Collection: Obtain the molecular weights (molar masses) of all reactants and the desired product.

- Calculation:

- Sum the molecular weights of all reactants, remembering to multiply each by its stoichiometric coefficient.

- Calculate the total molecular weight of the desired product, accounting for its stoichiometric coefficient.

- Apply the atom economy formula.

- Analysis: Classify the reaction based on the result. A higher percentage indicates a greener reaction from a raw material utilization perspective [30].

E-Factor

Theoretical Foundation and Calculation

The Environmental Factor (E-Factor), developed by Roger Sheldon, quantifies the actual waste generated per mass of product in a process [27] [28]. While atom economy is a predictive, theoretical tool, E-Factor measures the real-world waste output, accounting for reaction yield, solvent use, energy consumption, and all other process inputs [28].

The formula for E-Factor is:

E-Factor = Total mass of waste (kg) / Mass of product (kg) [27] [28]

A lower E-Factor is desirable, with an ideal value of zero, representing a waste-free process. The "total mass of waste" includes all non-product outputs, such as by-products, unreacted reagents, and solvents [28]. Some calculations exclude water from the waste total, so it is important to specify which approach is used [28].

Table 2: E-Factor Values Across Industry Sectors [28]

| Industry Sector | Annual Production (Tonnes) | Typical E-Factor (kg waste/kg product) |

|---|---|---|

| Oil Refining | 10⁶ – 10⁸ | < 0.1 |

| Bulk Chemicals | 10⁴ – 10⁶ | < 1.0 – 5.0 |

| Fine Chemicals | 10² – 10⁴ | 5.0 – > 50 |

| Pharmaceuticals | 10 – 10³ | 25 – > 100 |

The high E-Factors in the pharmaceutical industry are attributed to multi-step syntheses, the use of stoichiometric reagents rather than catalysts, and the extensive use of solvents for purification [28].

Experimental Protocol and Methodology

Objective: To experimentally determine the E-Factor for a laboratory-scale chemical synthesis. Principle: The E-Factor provides a practical measure of the environmental impact of a specific experimental procedure by quantifying all waste streams [28].

Procedure:

- Mass Recording: Precisely weigh all input materials, including reactants, solvents, catalysts, and any other reagents used in the reaction and work-up.

- Synthesis and Isolation: Perform the synthesis according to the established protocol. Isolate and thoroughly dry the final product.

- Product Mass: Accurately weigh the mass of the pure, dry product obtained.

- Waste Calculation:

- Total mass of inputs = Sum of masses of all materials used.

- Total mass of waste = Total mass of inputs - Mass of product.

- E-Factor Calculation: Apply the E-Factor formula.

Case Study - Sertraline Synthesis: Pfizer redesigned the synthesis of its antidepressant sertraline (Zoloft) by implementing a green chemistry approach. This involved switching to a safer solvent (ethanol vs. CH₂Cl₂/THF) and a more selective catalyst. These changes dramatically reduced solvent usage and improved efficiency, lowering the E-Factor to 8 for the commercial manufacturing process [28].

Life Cycle Thinking

Theoretical Foundation

Life Cycle Thinking (LCT) is a holistic approach that expands the assessment of a chemical process beyond the reaction flask to consider its broader environmental, economic, and social impacts at every stage—from raw material extraction to final disposal [32]. Also referred to as Systems Thinking in green chemistry, it challenges chemists to see the "big picture" and avoid problem-shifting, where solving one environmental issue inadvertently creates another [32].

LCT is intimately connected to Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), which is the comprehensive quantitative methodology used to evaluate the environmental impacts associated with all stages of a product's life. While simple metrics like atom economy and E-Factor are crucial for evaluating reaction efficiency, they are mass-based and do not differentiate between benign and hazardous waste [27] [32]. LCT provides the framework to incorporate these critical distinctions and other factors like energy consumption and resource depletion into the overall sustainability evaluation [32].

Application Framework

Implementing LCT in research and development involves a shift in perspective and practice:

- Holistic Process Design: Chemists are encouraged to design processes that consider the entire lifecycle of a chemical. This includes designing chemicals that break down into non-toxic substances after use and manufacturing plans that reduce solvent and wastewater volumes [32].

- Informed Material Selection: LCT guides the selection of raw materials, favoring renewable feedstocks over depleting ones, and assessing the environmental costs of their extraction and transportation [32].

- Professional Development: Training scientists in LCT develops crucial skills, including anticipating outcomes, assessing trade-offs, and drawing conclusions from complex, imperfect data. This prepares them to identify research opportunities that effect powerful, positive change [32].

Comparative Analysis and Integrated Application

The Interrelationship of Core Metrics

Atom economy, E-Factor, and Life Cycle Thinking are not mutually exclusive but are complementary tools that provide different layers of insight. Atom economy offers a rapid, theoretical screen for synthetic routes at the design stage. E-Factor provides a practical, experimental measure of waste production for a specific implemented process. Life Cycle Thinking is the overarching philosophy that ensures all environmental trade-offs, from resource extraction to end-of-life, are considered.

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for applying these core concepts to assess and improve a chemical process:

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The transition to greener methodologies often relies on specific tools and reagents. The following table details key solutions for implementing the principles discussed in this guide.

Table 3: Key Reagents and Tools for Green Chemistry Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Green Chemistry | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Catalysts (e.g., solid acid/base, enantioselective) | Increase reaction efficiency and selectivity, reduce stoichiometric reagent waste, enable milder reaction conditions. | Replacing stoichiometric reagents in oxidation or reduction steps to lower E-Factor [28]. |

| Benign Solvents (e.g., Ethanol, Water, 2-MeTHF) | Replace hazardous solvents (e.g., Dichloromethane, Chloroform) to improve safety and reduce toxic waste. | Solvent replacement in university laboratory curricula to minimize student exposure and hazardous waste streams [33]. |

| Microwave Reactors | Provide rapid, energy-efficient heating, often accelerating reactions and improving yields. | Performing Diels-Alder and Fischer Esterification reactions with reduced energy consumption and time [33]. |

| Renewable Feedstocks | Serve as raw materials derived from biomass, reducing reliance on finite fossil fuels. | Using glucose or other sugars as a starting material for chemical synthesis [30]. |

The integration of atom economy, E-Factor, and Life Cycle Thinking provides a robust, multi-faceted framework for advancing green chemistry. Atom economy serves as a fundamental design criterion, E-Factor as a practical metric for process optimization, and Life Cycle Thinking as the essential, holistic context for true sustainability. For researchers and professionals in drug development, mastering these core competencies is no longer optional but a critical requirement for designing efficient, economical, and environmentally responsible chemical processes. The ongoing challenge for the scientific community is to continue developing and applying these metrics, fostering a culture of systems thinking that will drive innovation toward a more sustainable future.

The field of chemical design is undergoing a fundamental transformation, moving from a paradigm of evaluating hazard after a molecule is synthesized to one of integrating toxicological principles directly into the molecular design process. This approach, central to a modern green chemistry curriculum, empowers chemists to design inherently safer and more sustainable chemicals and materials. Known as Green Toxicology, this strategy amplifies the core principles of Green Chemistry by incorporating health-related considerations for the benefit of both consumers and the environment, while also proving economically advantageous for manufacturers [34]. The costly development of new materials makes it impractical to ignore the safety and environmental status of new products until the final stages of development. Instead, toxicologists and chemists must collaborate early in the development process to utilize safe design strategies and innovative in vitro and in silico tools [34]. This guide provides a comprehensive technical framework for integrating hazard assessment into molecular design, equipping chemists with the theories and tools needed to meet this imperative.

Foundational Concepts in Toxicological Hazard Assessment

To effectively integrate hazard assessment into design, chemists must first grasp several key toxicological concepts that form the basis for evaluating chemical safety.

- Chemical Hazard vs. Risk: A critical distinction must be made between a chemical's inherent hazard (its potential to cause harm) and the risk (the probability that harm will occur under specific conditions of exposure). Green toxicology focuses first on minimizing intrinsic hazard, thereby reducing or eliminating the need for exposure controls downstream [35] [36].

- Toxicokinetics and Mode of Action (MOA): Understanding a chemical's Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion (ADME) is crucial for predicting its biological activity. Furthermore, elucidating its Molecular Initiating Event (MIE) and subsequent Mode of Action (MOA) provides a mechanistic basis for understanding how a chemical structure leads to an adverse outcome [35] [36].

- The Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) Framework: The AOP is a structured concept that links a molecular-level initiating event (e.g., a chemical binding to a receptor) through a series of key events to an adverse outcome at the organism or population level [36]. This framework is exceptionally valuable for using early, mechanistic data (often from in vitro or in silico methods) to predict the potential for adverse effects without resorting to extensive animal testing.

- Threshold of Toxicological Concern (TTC): The TTC is a risk assessment approach that establishes a human exposure threshold below which there is no significant risk, even in the absence of chemical-specific toxicity data. It is a powerful tool for waiving unnecessary testing when exposures are anticipated to be very low and can be integrated into decision trees and software for early-stage chemical assessment [36].

In Silico Predictive Tools for Safer Chemical Design

Computational toxicology provides powerful, high-throughput methods for predicting potential hazards directly from chemical structure, making it ideally suited for the early design phase.

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) Modeling

QSAR models use mathematical relationships between a chemical's molecular descriptors and its biological activity to predict toxicity. A prime example is the prediction of ionic liquid toxicity to aquatic organisms.

Table 1: Molecular Descriptors and Their Impact on Ionic Liquid Toxicity [37]

| Molecular Descriptor | Impact on Aquatic Toxicity (to V. fischeri and D. magna) |

|---|---|

| Alkyl Chain Length | Toxicity increases with increasing chain length on cations (e.g., imidazolium, pyridinium). |

| Number of Nitrogen Atoms in Aromatic Cation | Toxicity increases with more nitrogen atoms (Trend: ammonium < pyridinium < imidazolium < triazolium). |

| Cation Ring Methylation | Toxicity decreases with increased methylation of the cation ring. |

| Number of Negatively Charged Atoms on Cation | Toxicity decreases with an increase in negatively charged atoms. |

| Anion Role | Plays a secondary role; anions with positively charged atoms may slightly increase toxicity. |

Read-Across and Chemical Categorization

Read-across is a technique used to fill data gaps for a "target" chemical by using experimental data from similar "source" chemicals [36]. By grouping chemicals based on shared structural features, functional groups, or physicochemical properties, the known toxicological properties of well-characterized compounds can be used to predict the properties of new, analogous structures in the design portfolio.

Experimental and In Vitro Methodologies

While in silico tools are excellent for initial screening, experimental data are often required for greater confidence. Green Toxicology promotes the use of innovative in vitro methods that reduce animal testing, use smaller amounts of test material, and provide faster, human-relevant mechanistic insights.

Tiered Testing and Integrated Workflows

A strategic, step-wise approach to testing is recommended to efficiently utilize resources.

Diagram: Workflow for Tiered Hazard Assessment

One proposed workflow involves using in vitro assays to rank chemicals based on their relative selectivity for biological targets associated with known toxicity [36]. The concentrations at which these effects occur are then converted into an external human dose using reverse toxicokinetic modeling and in vitro-to-in vivo extrapolation (IVIVE). This predicted dose can be compared to anticipated human exposure to calculate a Margin of Exposure (MoE), providing a quantitative basis for early decision-making [36].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Assays

Table 2: Essential Research Tools for Green Toxicology [36] [34] [38]

| Tool / Reagent | Function in Hazard Assessment |

|---|---|

| Luminescent Bacteria (Vibrio fischeri) | Rapid screening of microbial toxicity (e.g., Microtox assay); measures decrease in luminescence as an indicator of respiratory inhibition. |

| Freshwater Crustaceans (Daphnia magna) | Model organism for standard acute toxicity bioassays in freshwater ecosystems; a key link in the aquatic food web. |

| High-Throughput in Vitro Assays | Automated cell-based assays to probe specific mechanisms of toxicity (e.g., receptor binding, cytotoxicity) using very small compound quantities (<500 mg/assay). |

| Toxicogenomic Tools (Transcriptomics, Proteomics) | "Omics" technologies to measure global gene or protein expression changes, revealing mechanistic pathways and potential biomarkers of toxicity. |

| Physiologically Based Toxicokinetic (PBTK) Models | Computational models that simulate the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion of chemicals in the body to relate external dose to internal target organ concentration. |

Applying Green Toxicology in Product Development Lifecycle

Integrating these tools requires a conscious strategy throughout the product development lifecycle. The core principles of Green Toxicology can be summarized as follows [34]:

- Benign-by-Design: Proactively design molecules to be non-toxic, for example, by incorporating metabolically labile groups, reducing its potential for bioaccumulation, or avoiding structural alerts associated with specific hazards.

- Test Early, Produce Safe: "Front-load" toxicity assessments using predictive tools during the discovery and development phases, not just for regulatory compliance. This allows for "failing early and failing cheaply," saving significant resources [34].

- Avoid Exposure and thus Testing Needs: Where possible, design processes and products that minimize human and environmental exposure. If there is no exposure, the hazard becomes irrelevant and testing needs are reduced.

- Make Testing Sustainable: Reduce the use of animals in testing by adopting the 3Rs (Replacement, Reduction, Refinement). Furthermore, minimize the volumes of chemicals and solvents used in testing protocols to reduce waste [34].

The integration of toxicological hazard assessment into molecular design is no longer an optional specialty but a core competency for the modern chemist. By mastering and applying the principles of Green Toxicology—leveraging in silico predictions, employing tiered in vitro testing strategies, and embracing a mindset of safety-by-design—chemists can lead the creation of a new generation of functional, innovative, and inherently safer chemicals and materials. This integration is the cornerstone of a truly sustainable chemical industry and a critical component of any advanced green chemistry curriculum.

Practical Application: Green Chemistry Techniques in Drug Discovery and Development

Catalysis, defined as the increase in the rate of a chemical reaction by adding a substance (the catalyst) not itself consumed, represents a cornerstone of green chemistry by minimizing energy consumption and waste generation [39]. The strategic application of catalytic processes enables more sustainable chemical transformations, reduces reliance on finite resources, and decreases environmental pollution. Within this framework, photocatalysis, electrocatalysis, and biocatalysis have emerged as three particularly promising technological pathways for advancing green chemistry objectives. These catalytic approaches utilize different primary energy inputs—light, electricity, and enzymatic action, respectively—to drive chemical reactions with enhanced efficiency and selectivity while minimizing undesirable by-products.

The integration of these catalytic methodologies into educational curricula for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals is essential for developing core competencies in sustainable chemical synthesis. This technical guide provides a comprehensive overview of the fundamental principles, current advancements, and practical applications of these catalytic technologies, with particular emphasis on their role in addressing global energy and environmental challenges. By fostering a deeper understanding of catalyst design, reaction mechanisms, and performance optimization, this review aims to equip professionals with the knowledge necessary to implement these sustainable technologies in both research and industrial settings.

Photocatalysis: Harnessing Light Energy

Fundamental Principles and Mechanisms

Photocatalysis utilizes semiconductor materials to convert light energy into chemical potential capable of driving chemical reactions. The process initiates when a photocatalyst absorbs photons with energy equal to or greater than its bandgap energy, promoting electrons (e⁻) from the valence band (VB) to the conduction band (CB) while generating positive holes (h⁺) in the valence band [40]. These photogenerated charge carriers then migrate to the catalyst surface where they participate in redox reactions with adsorbed species. The overall process can be summarized in three primary steps: (1) photon absorption and electron-hole pair generation, (2) charge carrier separation and migration, and (3) surface redox reactions [40].

Titanium dioxide (TiO₂) remains one of the most extensively researched photocatalysts due to its chemical stability, non-toxicity, and favorable band positions. However, its wide bandgap (3.0-3.2 eV) restricts light absorption primarily to the ultraviolet region, which constitutes only about 6% of the solar spectrum [40]. This limitation has motivated research into various modification strategies, including doping with metal (e.g., iron, silver) or non-metal (e.g., nitrogen, sulfur, carbon) elements, coupling with other semiconductors to form heterojunctions, and surface modification with sensitizers [40].

Figure 1: Fundamental mechanism of semiconductor photocatalysis showing light absorption, charge separation, and surface redox reactions.

Advanced Materials and Performance Optimization

Recent research has expanded beyond traditional TiO₂ to develop novel photocatalytic materials with enhanced visible-light responsiveness. Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) have shown exceptional promise due to their tunable porous structures and catalytic properties, though their structural evolution under operational conditions must be carefully considered [39]. Covalent organic frameworks (COFs), particularly cyano-based COFs modified with noble metal sites (Pt, Pd, Au, Ag), have demonstrated remarkable performance for photocatalytic hydrogen peroxide production, with rates exceeding 850 μmol·g⁻¹·h⁻¹ under visible irradiation [41]. These materials establish efficient electron transfer pathways that facilitate charge separation and optimize reaction pathways.

Heterojunction engineering represents another powerful strategy for enhancing photocatalytic efficiency. The construction of interfaces between different semiconductors, such as the CdS-BaZrO₃ heterojunction, facilitates spatial separation of photogenerated charges, suppressing recombination and maintaining high redox ability [41]. Such heterostructures have achieved hydrogen production rates of 44.77 μmol/h, representing a 4.4-fold enhancement compared to the pristine components [41]. Similarly, emerging moiré superlattice structures, a distinct class of 2D material configurations, have demonstrated exceptional performance in photocatalytic methane reforming, enabling efficient conversion with remarkable selectivity up to 96% at significantly reduced energy consumption [42].

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Selected Photocatalytic Systems for Energy Production

| Photocatalyst | Reaction | Performance | Conditions | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CdS-BaZrO₃ heterojunction | Water splitting for H₂ production | 44.77 μmol/h | Without co-catalyst | [41] |

| Noble metal/cyano-COF (Pd) | O₂ reduction to H₂O₂ | 1073 ± 35 μmol·g⁻¹·h⁻¹ | Visible light irradiation | [41] |

| N-TiO₂ | Formic acid degradation | Quantum efficiency: 3.5 | UVA light | [41] |

| Moiré superlattice catalyst | Methane reforming | 96% selectivity | Reduced energy consumption | [42] |

| P25 TiO₂ | Formic acid degradation | Quantum efficiency: 6.2 | UVA light | [41] |

Experimental Protocol: Photocatalytic Hydrogen Production Using Heterojunction Catalysts

Objective: To evaluate the photocatalytic hydrogen production performance of a CdS-BaZrO₃ heterojunction catalyst under visible light irradiation.

Materials:

- CdS-BaZrO₃ heterojunction photocatalyst (prepared via chemical-bath deposition method)