From Silent Spring to Sustainable Labs: The Historical Context and Modern Applications of Green Chemistry in Drug Development

This article traces the evolution of the sustainable chemistry movement from its foundational environmental protests to its current status as a driver of innovation in pharmaceutical research and development.

From Silent Spring to Sustainable Labs: The Historical Context and Modern Applications of Green Chemistry in Drug Development

Abstract

This article traces the evolution of the sustainable chemistry movement from its foundational environmental protests to its current status as a driver of innovation in pharmaceutical research and development. It explores the historical catalysts, from Rachel Carson's 'Silent Spring' to the formalization of the Twelve Principles, that shaped green chemistry. For researchers and drug development professionals, the content provides a methodological guide to applying sustainable practices, including solvent-free synthesis and AI-driven reaction optimization. It further addresses troubleshooting common implementation challenges and validates the approach through case studies of award-winning industrial applications and emerging trends poised to redefine sustainable biomedical research.

The Roots of a Revolution: Tracing the Environmental Catalysts that Forged Green Chemistry

The period preceding the 1990s established a foundational environmental paradigm characterized by a reactive approach to pollution. This framework, known as end-of-pipe treatment, focused on containing or treating waste streams after their generation, rather than preventing pollution at its source [1]. The model emerged alongside a growing public consciousness about environmental degradation, fueled by visible ecological crises and seminal scientific writings that collectively spurred legislative action and formed the early environmental movement [2]. This whitepaper examines the technological, regulatory, and social drivers of this paradigm, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a historical context for the subsequent shift towards sustainable chemistry and green manufacturing principles.

Historical Context: The Rise of Environmental Awareness

The end-of-pipe approach was not an isolated technological strategy but a response to a specific historical context marked by escalating pollution and growing public demand for action.

- Early Conservation (Late 19th - Early 20th Century): The initial movement focused on sustainable resource management and preserving wilderness areas. Key milestones included the establishment of the first national parks like Yellowstone (1872) and conservation groups like the Sierra Club (1892) [2]. This era was guided by a conservation ethic, exemplified by Theodore Roosevelt's expansion of national forests and parks [3].

- The Modern Environmental Movement (1960s-1970s): A pivotal shift occurred in the 1960s as concern broadened from conservation to pervasive air and water pollution [3]. Rachel Carson's Silent Spring (1962) warned of pesticide devastation, becoming a bestseller with immense global impact [2]. Highly visible environmental disasters cemented public consciousness:

- Legislative and Institutional Response: Public outcry translated into unprecedented policy action. The U.S. established the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 1970, and the first Earth Day drew 20 million participants [2]. Landmark legislation, including the Clean Air Act (1963, expanded 1970), the Clean Water Act (1972), and the Endangered Species Act (1973), created a new regulatory framework mandating pollution control [2]. These laws primarily set limits for pollutant concentrations in emissions and effluent, making end-of-pipe technologies the most direct compliance pathway [1].

Defining the End-of-Pipe Approach

End-of-pipe solutions represent a class of environmental management strategies focused on treating pollutants or waste streams after they have been generated by a process or activity, immediately before release into the environment [1]. The core principle is interception and remediation at the point of discharge. This fundamentally differs from preventative measures that aim to stop pollution at its source.

- Core Philosophy: The approach is inherently reactive. It manages the symptoms of pollution (the waste stream) rather than addressing the root cause within the industrial process itself [1].

- Objective: The primary goal is to reduce the pollutant load to levels deemed acceptable by regulatory standards before release occurs, thereby mitigating immediate environmental harm [1].

- Regulatory Driver: Widespread adoption was largely driven by early environmental regulations that set concentration limits for discharges. This framework offered industries a clear, measurable target: install treatment technology to clean the waste stream before release [1].

Key End-of-Pipe Technologies and Methodologies

The following table catalogs major end-of-pipe technologies, their mechanisms, and typical applications, providing a reference for the technical solutions of the era.

Table 1: Key End-of-Pipe Technologies and Their Applications

| Pollutant Type | Medium | Technology | Mechanism of Action | Typical Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Particulate Matter | Air | Electrostatic Precipitator (ESP) | Uses an electrostatic charge to attract and remove particles from a flowing gas [1]. | Power plants, heavy industries [1]. |

| SO₂ & Gaseous Pollutants | Air | Scrubbers (e.g., Flue-Gas Desulfurization) | Removes gaseous pollutants via contact with a liquid or dry sorbent, neutralizing acids [1]. | Smelters, chemical plants, power generation [1]. |

| Organic Waste (BOD/COD) | Water | Biological Treatment (e.g., Activated Sludge) | Uses microorganisms to biologically degrade organic pollutants in wastewater [1]. | Municipal and industrial wastewater treatment plants [1]. |

| Heavy Metals | Water | Chemical Precipitation | Adds chemicals to wastewater to convert dissolved metals into insoluble solid particles for removal [1]. | Electroplating, metal finishing, mining effluent [1]. |

| Automotive Emissions | Air | Catalytic Converter | Converts toxic combustion byproducts (CO, NOx, hydrocarbons) into less harmful substances via catalytic reaction [1]. | Automotive exhaust systems [1]. |

| Landfill Gas (Methane) | Waste | Landfill Gas Collection System | Captures methane and other gases produced by decomposing waste via wells and piping [1]. | Municipal solid waste landfills [1]. |

Experimental and Operational Protocols

Implementing these technologies required standardized methodologies to ensure compliance and operational efficacy. Key procedural steps included:

- Source Characterization: Initial waste stream analysis to determine pollutant concentration, flow rate, temperature, and chemical composition. This informed the selection and sizing of the treatment technology [1].

- Technology-Specific Workflows:

- For Scrubbers: The protocol involved the continuous injection of the exhaust stream into a reaction vessel, simultaneous introduction of sorbent slurry (e.g., limestone), and subsequent collection of reaction byproducts (e.g., gypsum sludge) for disposal [1].

- For Wastewater Treatment: A multi-stage process was employed: Primary (physical screening and sedimentation), Secondary (biological degradation in aeration basins), and Tertiary (chemical or filtration polishing to remove specific contaminants like phosphorus or metals) [1].

- Performance Monitoring: Continuous or periodic sampling and analysis of treated effluent or emissions to verify compliance with regulatory discharge permits. This often involved measuring pH, suspended solids, and specific chemical concentrations [1].

The "Scientist's Toolkit": Research and Reagent Solutions for Environmental Analysis

The development and monitoring of end-of-pipe technologies relied on a suite of analytical methods and reagents. This toolkit was essential for quantifying pollution and verifying treatment efficacy.

Table 2: Essential Analytical Reagents and Methods for Pollution Monitoring

| Reagent/Method | Primary Function | Application in End-of-Pipe Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Nessler's Reagent | Colorimetric detection of ammonia. | Measuring ammonia nitrogen levels in wastewater treatment effluent to assess biological process health [1]. |

| Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD) Test | Quantifies organic pollutants. | Evaluating the oxygen-demanding strength of industrial and municipal wastewaters pre- and post-treatment [1]. |

| Atomic Absorption (AA) Spectroscopy | Detection of metal elements. | Measuring concentrations of heavy metals (e.g., Pb, Cd, Hg) in wastewater and sludge to ensure regulatory compliance [1]. |

| High-Volume Air Sampler | Particulate matter collection. | Gravimetric analysis of total suspended particulates (TSP) and PM₁₀ in industrial air emissions [1]. |

| pH Indicators & Buffers | Measure and control acidity/alkalinity. | Critical for optimizing chemical precipitation processes and monitoring final effluent pH before discharge [1]. |

Critical Analysis: Limitations and the Path to a New Paradigm

While effective for compliance, the end-of-pipe paradigm contained critical flaws that ultimately spurred the development of more sustainable approaches.

Inherent Limitations:

- Resource Inefficiency: The approach does not fundamentally alter the processes that generate pollution, thereby perpetuating resource waste and inefficiency [1].

- Secondary Waste Streams: Treatment processes often create new waste challenges, such as scrubber sludge or spent solvents, which require their own disposal protocols and containment [1].

- High Operational Costs: These systems incur significant ongoing costs for energy, chemical sorbents, and maintenance, leading to a continuous financial drain [4].

- Strategic Position in the Pollution Hierarchy: The universally accepted pollution hierarchy ranks environmental strategies in order of desirability: Prevention is highest, followed by Minimization, Reuse/Recycling, Treatment, and finally Disposal. End-of-pipe solutions occupy the "Treatment" level, signifying they are a less desirable, reactive measure [1].

The Regulatory and Economic Shift: The Pollution Prevention Act of 1990 marked a formal U.S. policy shift, declaring that "pollution should be prevented or reduced at the source whenever feasible" [5]. This policy change began to alter the economic calculus, encouraging source reduction over waste treatment.

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual and operational differences between the end-of-pipe paradigm and the emerging pollution prevention framework that would gain prominence in the 1990s.

Diagram Title: Reactive vs. Proactive Environmental Management

The pre-1990s paradigm of end-of-pipe treatment was an essential, albeit transitional, phase in environmental protection. It successfully mitigated the most visible and acute forms of pollution through technological innovation driven by regulatory pressure and public advocacy [2] [1]. However, its reactive nature, operational costs, and creation of secondary wastes revealed its systemic limitations [4] [1]. This framework's position within the pollution hierarchy—below prevention and minimization—highlighted its role as a tactical, not strategic, solution. The experiences and shortcomings of this era were instrumental in paving the way for the principles of green chemistry and sustainable engineering, which seek to prevent waste at the molecular level and design inherently safer, more efficient processes [5]. For researchers today, understanding this evolution is critical for appreciating the foundational logic behind modern sustainable science.

The modern sustainable chemistry movement did not emerge in a vacuum; it was catalyzed by a series of pivotal environmental wake-up calls that exposed the profound consequences of chemical pollution on human health and ecological systems. Three landmark events—the 1962 publication of Rachel Carson's Silent Spring, the 1970s Love Canal toxic waste crisis, and the passage of the 1990 Pollution Prevention Act—collectively shifted scientific, regulatory, and public paradigms from pollution control to pollution prevention. This whitepaper examines these critical milestones within the broader historical context of sustainable chemistry research, tracing their role in transforming chemical design, manufacturing, and regulatory frameworks. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding this evolution is essential for advancing greener synthetic pathways, reducing hazardous waste generation, and embracing the principles of green chemistry that now underpin cutting-edge sustainable research.

Silent Spring: The Catalyst for Environmental Consciousness

Historical Context and Scientific Foundation

Published in 1962, Rachel Carson's Silent Spring represented a paradigm shift in scientific and public understanding of pollution's interconnected impacts. Carson, a marine biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service from 1936 to 1952, synthesized scientific evidence on the ecological harm caused by synthetic pesticides, particularly DDT (dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane) [6]. Her work emerged during a post-WWII era when science and industry were enthusiastically translating wartime technologies into commercial products, with U.S. production of DDT leaping from 4,366 tons in 1944 to a peak of 81,154 tons in 1963 [6]. Carson documented how pesticides not only targeted pests but also traveled through ecosystems, accumulated in food chains, harmed wildlife, and posed potential human health risks, including carcinogenesis [6] [7].

Carson's methodological approach was notable for its interdisciplinary rigor, citing dozens of scientific reports, conducting interviews with leading experts, and reviewing materials across disciplines [6]. She compiled evidence on chemical impacts across aerial sprayings, industrial settings, and food applications, characterizing these impacts in ecological terms rather than simply assessing chemical efficacy [6]. This systems-thinking approach revealed the interconnectedness of biological systems—a foundational concept for modern green chemistry.

Key Findings and Impact

Silent Spring introduced several revolutionary concepts to the public consciousness: that spraying chemicals to control insect populations could kill birds that feed on dead or dying insects; that chemicals travel through environments and food chains; that persistent chemicals could accumulate in fat tissues causing medical problems later; and that chemicals could be transferred generationally from mothers to their young [6]. Importantly, Carson did not advocate for an outright ban on pesticides but rather for caution, further study, and development of biological alternatives [6] [7].

The book sparked immediate controversy, drawing fierce opposition from chemical companies but ultimately resonating with political leaders and the public [6] [8]. The legacy of Silent Spring includes direct policy impacts such as the ban on domestic DDT use in 1972 due to its widespread overuse and harmful environmental impact, the establishment of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in 1970, and the passage of numerous environmental laws [6] [9]. The book also promoted a paradigm shift in how chemists practice their discipline, helping establish a new role for chemists in investigating the impact of human activity on the environment [6].

Table 1: Key Environmental Legislation Following Silent Spring

| Legislation | Year | Key Provisions | Impact on Chemical Industry |

|---|---|---|---|

| National Environmental Policy Act | 1969 | Established national environmental policy and created Council on Environmental Quality | Required environmental impact statements for major projects [9] |

| Clean Air Act | 1970 | Regulated air emissions from stationary and mobile sources | Set limits on hazardous air pollutants from chemical plants [10] |

| Clean Water Act | 1974 | Established wastewater standards for industry | Controlled chemical discharges into water systems [10] |

| Toxic Substances Control Act | 1976 | Gave EPA authority to require reporting and restrictions on chemical substances | Regulated new and existing chemicals in commerce [10] |

Love Canal: The Consequences of Improper Chemical Disposal

Background and Discovery

The Love Canal tragedy represents one of the most appalling environmental disasters in American history, directly demonstrating the human health consequences of improper chemical waste management [11]. From 1942 to 1952, Hooker Chemical Company dumped approximately 19,800 metric tonnes of chemical byproducts from manufacturing dyes, perfumes, and solvents for rubber and synthetic resins into the abandoned Love Canal in Niagara Falls, New York [12]. The canal was subsequently covered with clay and sold to the local school district for $1 in 1953, with a deed containing a liability limitation clause attempting to release Hooker from future legal obligations [12].

By the late 1970s, following record rainfall, the disaster emerged as corroding waste-disposal drums broke through the ground in residents' backyards, with chemical puddles forming in yards and basements, and noxious substances contaminating the air [11]. The New York State Health Department investigated disturbingly high rates of miscarriages and birth defects in the area, while residents showed high white-blood-cell counts, a possible precursor to leukemia [11]. One resident recounted two grandchildren with birth defects—one born deaf with a cleft palate and another with an eye defect—highlighting the human tragedy [11].

Methodological Approaches in Environmental Assessment

The investigation of Love Canal employed multiple scientific methodologies to document contamination and health impacts:

- Environmental Sampling: Testing of soil, groundwater, and air for chemical contaminants, identifying 82 different compounds, including 11 suspected carcinogens [11]

- Health Epidemiology Studies: Investigation of miscarriage rates, birth defects, and potential leukemia cases through community health assessment [11]

- Engineering Assessments: Evaluation of drum integrity, leaching mechanisms, and containment failure analysis [11]

These methodologies established critical cause-effect relationships between chemical exposure and human health impacts, providing a template for future hazardous waste site investigations.

Policy and Regulatory Outcomes

Love Canal had profound regulatory consequences, most notably prompting the passage of the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA) of 1980, commonly known as Superfund [12]. This law:

- Established a federal "Superfund" to clean up uncontrolled hazardous waste sites

- Created a system for determining responsible parties for contamination

- Enabled both short-term removals and long-term remedial actions

- Implemented a National Priorities List for prioritizing cleanup sites

The Love Canal site itself was proposed for the Superfund National Priorities List on December 30, 1983, formally listed on September 8, 1984, construction was completed on September 29, 1998, and it was officially deleted from the list on September 30, 2004, after 21 years of cleanup [12].

Table 2: Love Canal Timeline and Impacts

| Year | Event | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| 1942-1952 | Hooker Chemical uses Love Canal as dump site | 19,800 metric tonnes of chemical waste buried [12] |

| 1953 | Hooker sells property to school board for $1 | Deed includes liability limitation clause [12] |

| 1950s | Homes and school built on and near canal | Approximately 100 homes and school exposed [12] |

| 1977 | Contamination discovered | 82 compounds identified, 11 suspected carcinogens [11] |

| 1978 | Emergency declarations | First emergency funds for non-natural disaster [11] |

| 1980 | CERCLA (Superfund) passed | Direct response to Love Canal and similar sites [12] |

Pollution Prevention Act of 1990: Codifying the Paradigm Shift

Legislative Framework and Definitions

The Pollution Prevention Act (PPA) of 1990 marked a fundamental shift in U.S. environmental policy, establishing a national policy that pollution should be prevented or reduced at the source whenever feasible [13] [14]. The legislation declared a hierarchical approach to environmental management: first, prevent or reduce pollution at the source; second, recycle in an environmentally safe manner; third, treat pollution; and finally, dispose or release into the environment only as a last resort [13].

The PPA defined "source reduction" as any practice that reduces the amount of any hazardous substance, pollutant, or contaminant entering any waste stream or otherwise released into the environment prior to recycling, treatment, or disposal [13]. This specifically included:

- Equipment or technology modifications

- Process or procedure modifications

- Reformulation or redesign of products

- Substitution of raw materials

- Improvements in housekeeping, maintenance, training, or inventory control

Crucially, the Act explicitly excluded practices that alter the physical, chemical, or biological characteristics or volume of hazardous substances through processes not integral to production [13].

Implementation Mechanisms

The PPA established several key implementation mechanisms:

- EPA Office Establishment: Required the EPA Administrator to establish an independent office to carry out PPA functions and develop a strategy to promote source reduction [13]

- State Technical Assistance Grants: Created matching grant programs to states for promoting source reduction techniques by businesses [13]

- Source Reduction Clearinghouse: Established a clearinghouse to compile information including a computer database on management, technical, and operational approaches to source reduction [13]

- Toxic Chemical Reporting: Expanded the Toxics Release Inventory (TRI) to require facilities to report on source reduction and recycling activities [13] [14]

These mechanisms collectively shifted the regulatory focus from end-of-pipe treatment to preventative approaches, encouraging innovation in chemical processes and products.

Evolution of Green Chemistry Principles and Practices

Historical Development

The environmental awareness raised by Silent Spring and Love Canal, combined with the policy framework of the PPA, created fertile ground for the emergence of green chemistry as a distinct scientific field. In the 1990s, this evolution accelerated with several key developments:

- 1991: The term "Green Chemistry" was coined by staff of the EPA Office of Pollution Prevention and Toxins [9]

- 1994: The first symposium "Benign by Design: Alternative Synthetic Design for Pollution Prevention" was held in Chicago [9]

- 1995: Establishment of the annual Presidential Green Chemistry Challenge Awards [9]

- 1997: Creation of the Green Chemistry Institute (GCI) as an independent nonprofit [10]

- 1998: Paul Anastas and John C. Warner co-authored Green Chemistry: Theory and Practice, outlining the 12 Principles of Green Chemistry [9] [10]

The field gained scientific credibility through Nobel Prizes in 2001 (Knowles, Noyori, Sharpless for chiral catalysis) and 2005 (Chauvin, Grubbs, Schrock for metathesis reactions), both recognizing research areas aligned with green chemistry principles [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Green Chemistry Research Reagents

Table 3: Research Reagents and Alternatives in Green Chemistry

| Reagent/Category | Traditional Examples | Green Alternatives | Function & Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solvents | Halogenated (CH₂Cl₂, CHCl₃), BTEX solvents | Supercritical CO₂, water, ionic liquids, bio-based solvents | Reaction media with reduced toxicity and environmental impact [9] |

| Catalysts | Heavy metals (Pd, Pt) | Biocatalysts, organocatalysts, immobilized catalysts | Increase efficiency, reduce energy requirements, enable alternative pathways [10] |

| Oxidizing Agents | Chromium(VI) reagents, peracids | Hydrogen peroxide, oxygen (air), enzymatic oxidation | Safer stoichiometric oxidants with less hazardous byproducts [15] |

| Reducing Agents | Metal hydrides (LiAlH₄) | Catalytic hydrogenation, biomimetic reductants | Safer reduction processes with better atom economy [15] |

| Feedstocks | Petroleum-based | Biomass-derived, renewable feedstocks | Sustainable carbon sources with reduced lifecycle impacts [9] |

Analytical Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Environmental Monitoring Techniques

The wake-up calls of Silent Spring and Love Canal drove innovations in environmental monitoring methodologies that remain essential today:

- Chromatographic Methods: Advanced GC-MS and LC-MS protocols for detecting pesticide residues and chemical contaminants at parts-per-billion levels in environmental and biological samples

- Ecological Impact Assessment: Standardized protocols for measuring bioaccumulation factors (BAFs) and biomagnification in food webs

- Toxicological Screening: Cell-based assays and animal models for assessing chronic toxicity, endocrine disruption, and carcinogenicity of chemicals

- Environmental Fate Studies: Radiolabeled compound tracking to determine persistence, degradation pathways, and metabolite formation

Green Chemistry Metrics and Assessment

Green chemistry developed standardized metrics to evaluate the environmental performance of chemical processes:

- Atom Economy: Calculation of the proportion of reactant atoms incorporated into the final product

- Environmental Factor (E-Factor): Total waste produced per unit of product (kg waste/kg product)

- Process Mass Intensity (PMI): Total mass used in a process per unit of product (kg total materials/kg product)

- Life Cycle Assessment (LCA): Holistic evaluation of environmental impacts across a product's entire lifecycle

Conceptual Framework and Signaling Pathways

The evolution of sustainable chemistry represents a fundamental paradigm shift in how chemical processes are conceived, designed, and implemented. The diagram below illustrates this conceptual framework and the relationships between key historical events, regulatory responses, and scientific developments.

The trajectory from Silent Spring to Love Canal to the Pollution Prevention Act represents a critical evolution in environmental thought—from recognizing problems to mandating preventative solutions. For today's researchers and drug development professionals, this historical context provides both a moral imperative and practical framework for advancing sustainable chemistry. The current challenges of climate change, resource depletion, and continuing chemical pollution demand renewed commitment to green chemistry principles. Future directions include advancing biocatalysis, continuous flow chemistry, artificial intelligence-guided molecular design, and the transition from petroleum to renewable feedstocks. By building upon the legacy of these landmark wake-up calls, the scientific community can continue transforming chemical practice to harmonize human well-being with planetary health.

The formalization of green chemistry as a distinct scientific discipline originated within the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in the early 1990s. This transformative approach emerged as a strategic response to the Pollution Prevention Act of 1990, which marked a fundamental policy shift from pollution control to pollution prevention. The EPA's Office of Pollution Prevention and Toxics (OPPT) was instrumental in catalyzing this movement, seeding initial research grants and building a foundational framework that translated policy into a new chemical design paradigm. This whitepaper details the historical context, key actors, and foundational programs established by OPPT that propelled green chemistry from a conceptual idea into a global sustainability framework essential for modern researchers and drug development professionals.

The period preceding the 1990s was characterized by a "command and control" or "end-of-pipe" regulatory approach to environmental management, focusing on treating and disposing of hazardous waste after it was created [16]. This began to change with growing environmental consciousness throughout the 1960s and 1970s, catalyzed by events such as the Cuyahoga River fire and the publication of Rachel Carson's Silent Spring, which ultimately led to the establishment of the EPA in 1970 [17]. The critical turning point for green chemistry, however, was the Pollution Prevention Act of 1990, which established a new U.S. national policy: pollution should be prevented or reduced at the source whenever feasible [16]. This legislation championed cost-effective changes in products, processes, and the use of raw materials over recycling, treatment, and disposal [16].

It was within this policy context that the EPA's OPPT moved away from a purely regulatory role. The office began championing a proactive approach, seeking to redesign chemical products and processes before they posed a risk to human health or the environment [16]. This philosophical and strategic pivot laid the essential groundwork for the birth of green chemistry as a formal field of study and practice.

The OPPT's Foundational Role in Establishing Green Chemistry

Key Milestones and Actions

The Office of Pollution Prevention and Toxics acted as the central engine for initializing the green chemistry movement through two primary, interconnected mechanisms: research funding and programmatic development.

Research Grant Program (1991): In direct response to the Pollution Prevention Act, OPPT launched a seminal research grant program in 1991, then termed "Alternative Synthetic Routes for Pollution Prevention" [16] [18]. This program provided crucial early funding to redesign existing chemical products and processes to reduce their impacts, representing the first major governmental investment in the concepts that would become green chemistry.

Program Expansion and Renaming (1992): Within a year, the program's scope expanded to include other topics like environmentally friendly solvents and safer chemical compounds. It was at this point that the initiative officially adopted the name "green chemistry," solidifying a new identity for this emerging field [18].

Partnership with the National Science Foundation (NSF): The EPA, through OPPT, partnered with the NSF in the early 1990s to fund basic research in green chemistry, lending further scientific credibility and academic reach to the nascent field [16].

The following timeline visualizes the key initiatives led by the OPPT and their pivotal role in the early development of green chemistry.

From Concept to Formal Principles: The Presidential Green Chemistry Challenge

A cornerstone of OPPT's strategy to advance green chemistry was the creation of the Presidential Green Chemistry Challenge Awards in 1996 [16]. These awards were designed to recognize and promote real-world academic and industrial technologies that incorporated green chemistry, effectively creating a repository of success stories [16]. This program served a critical function in moving the field from theoretical discourse to demonstrated application, providing tangible case studies for educational and research purposes.

The intellectual framework of the field was codified in 1998 with the publication of the 12 Principles of Green Chemistry by Paul Anastas and John Warner [16] [18]. These principles provided a clear, comprehensive set of design guidelines, encompassing concepts such as waste prevention, atom economy, safer solvents and auxiliaries, and design for degradation [16]. This was a pivotal moment that gave the global research community a shared vocabulary and a systematic approach for designing safer chemical products and processes.

Quantitative Tracking and Industry Adoption

The EPA developed concrete mechanisms to track the adoption of green chemistry practices in industry, primarily through the Toxics Release Inventory (TRI) Program. The TRI tracks industrial implementation using specific source reduction codes, creating a valuable dataset for analyzing trends [19].

Table 1: TRI Green Chemistry and Engineering Tracking Codes

| Code | Practice | Primary Focus |

|---|---|---|

| S01 | Substituted a fuel | Material Substitution |

| S02 | Substituted an organic solvent | Material Substitution |

| S03 | Substituted raw materials, feedstock, or reactant chemical | Material Substitution |

| S04 | Substituted manufacturing aid, processing aid, or other ancillary chemical | Material Substitution |

| S05 | Modified content, grade, or purity of a chemical input | Material Substitution |

| S11 | Reformulated or developed new product line | Material Substitution |

| S21 | Optimized process conditions to increase efficiency | Process & Equipment Modification |

| S22 | Instituted recirculation within a process | Process & Equipment Modification |

| S23 | Implemented new technology, technique, or process | Process & Equipment Modification |

| S43 | Introduced in-line product quality monitoring or other process analysis system | Process & Equipment Modification |

Source: Adapted from EPA TRI Green Chemistry and Green Engineering Reporting [19]

These codes allow researchers and policymakers to quantitatively monitor the adoption of specific green chemistry strategies, such as solvent substitution (S02) or process optimization (S21), across industrial sectors [19]. The public accessibility of this data via the TRI Toxics Tracker tool makes it a powerful resource for benchmarking and research.

Core Principles and Methodologies for Researchers

The 12 Principles as a Design Framework

For research scientists and drug development professionals, the 12 Principles of Green Chemistry provide a proactive design framework. The central premise, embodied in Principle 1 (Prevention), is that it is inherently safer and more cost-effective to prevent waste than to treat or clean it up after it is formed [16]. This "ounce of prevention" reduces the need for hazard management and minimizes risks from potential accidents or exposures [16].

Key principles highly relevant to pharmaceutical R&D include:

- Principle 3: Less Hazardous Chemical Syntheses: Wherever practicable, synthetic methods should be designed to use and generate substances that possess little or no toxicity to human health and the environment.

- Principle 5: Safer Solvents and Auxiliaries: The use of auxiliary substances (e.g., solvents, separation agents) should be made unnecessary wherever possible and innocuous when used.

- Principle 9: Catalysis: Catalytic reagents (as selective as possible) are superior to stoichiometric reagents, minimizing energy use and waste by enabling more efficient reactions [19].

Experimental Protocol: A Green Chemistry Workflow for Method Development

Integrating green chemistry into research requires a systematic methodology. The following workflow provides a structured approach for developing chemical syntheses or analytical methods with reduced environmental and health impacts.

This iterative process emphasizes inherent rather than circumstantial safety, ensuring that risk is minimized at the molecular level through design, rather than through added controls or protective equipment [16].

The Research Reagent Toolkit: Essential Materials for Safer Synthesis

A practical application of green chemistry in the laboratory involves substituting hazardous reagents with safer alternatives. The following table details key reagent solutions that align with the principles of green chemistry.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Safer Chemical Synthesis

| Reagent Category | Function | Traditional Example | Greener Alternative | Principle Addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solvents | Substance dissolution, reaction medium | Halogenated (methylene chloride), Benzene | Water, Supercritical CO₂, Ethyl Lactate, Bio-based alcohols [18] | Safer Solvents & Auxiliaries |

| Catalysts | Increase reaction rate/selectivity, regenerated post-use | Stoichiometric reagents (e.g., AlCl₃) | Solid Acid Catalysts, Biocatalysts, Recyclable Metal Complexes [19] | Catalysis, Atom Economy |

| Feedstocks | Starting material for synthesis | Petrochemical derivatives | Biomass-derived sugars, Fatty acids, Agricultural waste streams [16] | Use of Renewable Feedstocks |

| Oxidizing Agents | Selective oxidation reactions | Heavy metal oxidants (CrO₃, KMnO₄) | Hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), Molecular Oxygen (O₂) [18] | Less Hazardous Synthesis, Design for Degradation |

Impact and Future Directions in Pharmaceutical and Chemical Research

The adoption of green chemistry has yielded multidimensional impacts, fundamentally shifting research and development in the pharmaceutical and specialty chemical industries. By designing for reduced hazard, companies have lowered the risks of occupational exposure and environmental contamination from accidents or improper disposal [16]. The systems-thinking approach of green chemistry also encourages lifecycle thinking, where the entire lifespan of a chemical product—from feedstock to end-of-life—is considered at the design stage to minimize waste and design for circularity or degradation [19].

Future research, as outlined in EPA's Chemical Safety for Sustainability Strategic Plan, focuses on developing predictive toxicology and advanced tools to make hazard a molecular property as malleable as melting point or color [16] [20]. The next frontier involves treating the 12 Principles not as isolated goals but as a cohesive, mutually reinforcing system to address interconnected sustainability challenges at the molecular level [16].

The genesis of green chemistry is a powerful example of how science policy can catalyze an entire scientific discipline. The EPA's Office of Pollution Prevention and Toxics provided the essential initial catalyst—through funding, program creation, and philosophical leadership—that transformed the mandate of the Pollution Prevention Act into the robust, principled field of green chemistry. For today's researchers and drug development professionals, the OPPT's foundational work provides a proven, effective framework for designing chemical products and processes that align economic viability with environmental responsibility and social good, turning molecular design into a primary strategy for achieving sustainability.

The development of the Twelve Principles of Green Chemistry in the 1990s represented a paradigm shift in how chemists approach the design of chemical products and processes. This formalization occurred against a backdrop of growing environmental awareness that began decades earlier. The 1962 publication of Rachel Carson's "Silent Spring" stimulated the contemporary environmental movement by highlighting the ecological damage caused by pesticides [18] [21]. This was followed by significant milestones including the 1972 Stockholm Conference, which alerted the world to environmental damage from ecosystem depletion, and the 1987 Brundtland Report, which first defined "sustainable development" as meeting present needs without compromising future generations [18].

The U.S. Pollution Prevention Act of 1990 marked a critical turning point by establishing that national policy should eliminate pollution through improved design rather than through treatment and disposal [16] [22]. In response to this legislation, Paul Anastas and John Warner formally articulated the Twelve Principles of Green Chemistry in their 1998 book Green Chemistry: Theory and Practice, providing a systematic framework for designing chemical products and processes that reduce or eliminate the use and generation of hazardous substances [18] [16]. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency launched its green chemistry program in 1991, and the field gained further recognition with the establishment of the annual Presidential Green Chemistry Challenge Awards in 1996 [16]. This historical trajectory reflects the chemical community's transition from pollution control to pollution prevention, embracing the core philosophy that it is better to prevent waste than to treat or clean it up after it is formed [18] [16].

The Twelve Principles: Framework and Interpretation

Paul Anastas and John Warner's Twelve Principles of Green Chemistry provide a comprehensive design framework for reducing the environmental impact of chemical processes and products across their entire life cycle [23]. These principles have guided academic and industrial innovations for more than two decades, encouraging chemists to pursue inherently safer and more efficient chemical synthesis [23] [16].

Table 1: The Twelve Principles of Green Chemistry with Key Focus Areas

| Principle | Core Concept | Key Focus Areas |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Prevention | Prevent waste rather than treat or clean up | Source reduction, process efficiency [23] |

| 2. Atom Economy | Maximize incorporation of materials into final product | Synthetic route design, molecular efficiency [23] |

| 3. Less Hazardous Chemical Syntheses | Design methods using/generating non-toxic substances | Alternative synthetic pathways, benign reagents [23] |

| 4. Designing Safer Chemicals | Preserve efficacy while reducing toxicity | Structure-activity relationships, toxicology [23] |

| 5. Safer Solvents and Auxiliaries | Minimize auxiliary substance use | Solvent selection, solvent-free reactions [23] |

| 6. Design for Energy Efficiency | Minimize energy requirements of processes | Ambient conditions, process intensification [24] |

| 7. Use Renewable Feedstocks | Utilize biomass rather than depleting resources | Biobased materials, agricultural wastes [24] |

| 8. Reduce Derivatives | Minimize unnecessary functionalization | Protecting group avoidance, direct synthesis [24] |

| 9. Catalysis | Prefer catalytic over stoichiometric reagents | Catalyst design, catalytic cycles [24] |

| 10. Design for Degradation | Design products to break down after use | Biodegradability, environmental persistence [24] |

| 11. Real-time Analysis | Monitor processes to prevent hazardous substance formation | Process analytical technology, in-line monitoring [24] |

| 12. Inherently Safer Chemistry | Choose substances to minimize accident potential | Chemical hazard assessment, process safety [24] |

The principles are interconnected, working together as a cohesive system with mutually reinforcing components rather than as isolated parameters to be optimized separately [16]. The first principle—prevention—is often regarded as the most fundamental, with the other principles representing the "how to" for its achievement [23]. As these principles have been implemented across the chemical enterprise, specific metrics have been developed to quantify their application and effectiveness.

Table 2: Key Green Chemistry Metrics for Process Evaluation

| Metric | Calculation | Interpretation | Ideal Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| E-Factor | Mass of waste ÷ Mass of product [24] | Lower values indicate less waste generation [24] | 0 |

| Atom Economy | (FW of atoms utilized ÷ FW of all reactants) × 100 [24] | Higher % indicates more efficient atom incorporation [23] | 100% |

| Process Mass Intensity (PMI) | Total mass in process ÷ Mass of product [24] | Lower values indicate better material efficiency [23] | 1 |

| EcoScale | 100 - penalty points across multiple categories [24] | Higher scores indicate greener processes [24] | 100 |

Figure 1: Interrelationships Among the Twelve Principles of Green Chemistry

Quantitative Assessment Frameworks in Green Chemistry

The implementation of green chemistry principles requires robust metrics to evaluate and compare the environmental performance of chemical processes. These quantitative tools enable researchers to make data-driven decisions when designing synthetic routes.

Atom Economy: A Fundamental Metric

Atom economy, developed by Barry Trost, evaluates the efficiency of a synthetic method by calculating what percentage of reactant atoms are incorporated into the final desired product versus being wasted as byproducts [23]. This differs from traditional yield calculations, which measure the efficiency of product formation without accounting for wasted starting materials.

For example, in the conversion of 1-butanol to 1-bromobutane:

Even with a 100% yield, the atom economy is only 50%, meaning half the mass of the reactant atoms is wasted in unwanted byproducts [23]. This metric encourages chemists to design syntheses that maximize the incorporation of starting materials into the final product.

Process Mass Intensity and E-Factor

While atom economy focuses on reactants, Process Mass Intensity (PMI) provides a more comprehensive assessment by including all materials used in a process—reactants, solvents, catalysts, and process aids—relative to the mass of product obtained [23] [24]. PMI has become favored in the pharmaceutical industry, where solvents often constitute the bulk of material input [23].

The E-factor, developed by Roger Sheldon, similarly measures environmental impact by calculating the ratio of waste to product mass [24] [22]. Different industry sectors typically operate within characteristic E-factor ranges:

- Oil refining: < 0.1

- Bulk chemicals: 1-5

- Fine chemicals: 5-50

- Pharmaceuticals: 25-100 [24]

These high E-factors in pharmaceutical manufacturing have driven substantial green chemistry innovation in that sector [23].

EcoScale: A Holistic Assessment Tool

The EcoScale provides a multi-criteria evaluation that incorporates yield, cost, safety, technical setup, temperature/time requirements, and workup/purification complexity [24]. It assigns penalty points across these categories, with higher final scores (closer to 100) indicating greener processes. This metric is particularly valuable because it integrates both quantitative and qualitative factors affecting process greenness.

Green Chemistry in Pharmaceutical Research and Development

The pharmaceutical industry has emerged as a significant adopter of green chemistry principles, driven by both environmental concerns and economic imperatives. The high E-factors traditionally associated with drug manufacturing—often exceeding 100 kg waste per kg of active pharmaceutical ingredient (API)—have motivated substantial process improvements [23] [25].

Case Study: Sustainable Drug Discovery at AstraZeneca

AstraZeneca has implemented multiple green chemistry strategies across its drug discovery and development pipeline. These include:

Late-stage functionalization: This technique modifies molecules late in their synthesis, creating "shortcuts" that reduce reaction times and resource-intensive steps. The company has used this approach to generate over 50 different drug-like molecules more sustainably [25]. One notable application enables selective addition of functional groups to drug compounds at precise molecular locations in a single step, dramatically improving synthetic efficiency [25].

Reaction miniaturization: In collaboration with Stockholm University, AstraZeneca has developed approaches using as little as 1mg of starting material to perform thousands of reactions. This high-throughput method allows exploration of a much larger range of drug-like molecules with the same amount of material [25].

Machine learning for reaction optimization: By analyzing large datasets of chemical reactions, machine learning algorithms help predict reaction outcomes and optimize conditions. AstraZeneca has developed models that outperform previous methods for predicting sites of borylation reactions, streamlining development while reducing waste [25].

Sustainable Catalysis in Pharmaceutical Manufacturing

Catalysis represents a cornerstone of green chemistry in pharmaceutical applications, with several innovative approaches being implemented:

Photocatalysis: Visible-light-mediated catalysis enables synthesis of crucial drug building blocks under mild conditions, employing safer reagents and opening new synthetic pathways. AstraZeneca has developed photocatalyzed reactions that remove several stages from cancer drug manufacturing, improving efficiency and reducing waste [25].

Electrocatalysis: This approach uses electricity to drive chemical reactions, offering sustainable routes to organic synthesis while replacing harmful chemical reagents. In one collaborative study, electrocatalysis was applied to selectively attach carbon units to create libraries of drug-like compounds [25].

Biocatalysis: Using enzymes to accelerate chemical reactions often achieves in single steps what requires multiple steps using traditional methods. Advances in computational enzyme design combined with machine learning are expanding the range of available biocatalysts [25].

Sustainable metal catalysis: Replacing precious metals like palladium with more abundant alternatives represents another green chemistry strategy. AstraZeneca has demonstrated that replacing palladium with nickel-based catalysts in borylation reactions reduces CO₂ emissions, freshwater use, and waste generation by more than 75% [25].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Green Chemistry Applications

| Reagent/Catalyst Type | Function | Green Chemistry Advantages |

|---|---|---|

| Nickel Catalysts | Cross-coupling reactions [25] | Replaces scarce palladium; >75% reduction in CO₂, water use, waste [25] |

| Biocatalysts (Enzymes) | Selective molecular transformations [25] | Single-step processes; renewable; biodegradable [25] |

| Photocatalysts | Light-mediated reactions [25] | Mild conditions; novel reactivities; reduced energy requirements [25] |

| Renewable Solvents | Reaction media [21] | Biobased origins; reduced toxicity; better biodegradability [21] |

| Supported Reagents | Facilitate reactions and separations [24] | Recyclable; reduce waste; improve efficiency [24] |

Figure 2: Green Chemistry Workflow in Pharmaceutical Development

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Late-Stage Functionalization Protocol

Late-stage functionalization represents a powerful green chemistry approach that modifies complex molecules at advanced synthetic stages, avoiding the need to reconstruct molecular scaffolds from simpler starting materials [25].

Experimental workflow:

- Substrate preparation: Dissolve the advanced intermediate (typically 0.1-0.5 mmol) in an appropriate green solvent (preferably ethanol, water, or 2-MeTHF).

- Catalyst system selection: Choose from:

- Photoredox catalysts (e.g., Ir(ppy)₃, Ru(bpy)₃²⁺) for radical-mediated functionalization

- Directed C-H activation catalysts (e.g., Pd-based with directing groups)

- Electrocatalytic setups with carbon-based electrodes

- Reaction execution: For photoredox reactions: irradiate with blue LEDs (typically 34W) while stirring at room temperature under nitrogen atmosphere for 2-24 hours.

- Reaction monitoring: Use TLC or UPLC-MS to track reaction progress.

- Product isolation: Employ direct crystallization or chromatography on sustainable supports (such as silica gel from rice husk ash).

- Analysis: Characterize products using NMR, HRMS, and determine purity by HPLC.

Key green chemistry benefits: This methodology typically reduces synthetic steps by 3-5 steps compared to traditional approaches, improving atom economy and reducing PMI by 30-60% [25].

Continuous Flow Photocatalysis Protocol

Continuous flow chemistry represents another green chemistry advancement, particularly when combined with photocatalysis for pharmaceutical applications [25].

Experimental setup:

- Reactor configuration: Use a commercially available or custom-built flow photoreactor with transparent fluoropolymer tubing (e.g., PFA, internal diameter 0.5-1.0 mm) wrapped around a light source.

- Solution preparation: Dissolve substrates (0.1-0.5 M) and photocatalyst (0.5-2 mol%) in degassed solvent mixture.

- Pumping system: Use syringe pumps or peristaltic pumps to maintain precise flow rates (typically 0.1-0.5 mL/min).

- Irradiation: Employ LED arrays at appropriate wavelength (commonly 450 nm for blue light-absorbing catalysts).

- Residence control: Adjust tube length and flow rate to achieve desired residence time (typically 5-30 minutes).

- Product collection: Collect outflow in a receiving flask, often with in-line quenching.

- Workup: Minimal processing required; often direct concentration or crystallization suffices.

Green chemistry advantages: This approach typically demonstrates 20-40% reduction in PMI, 50-80% reduction in reaction time, and improved safety profile compared to batch processes [25].

Current Challenges and Future Directions

Despite significant progress, green chemistry faces several challenges in broader implementation. In developing countries, sustainable chemistry remains a relatively new concept, with university curricula often lacking comprehensive coverage of green chemistry principles [26]. This educational gap creates a barrier to implementing these concepts in regions experiencing growing chemical production [26].

The field is also evolving beyond the original twelve principles to incorporate broader considerations. The emerging concept of "Responsible Research and Innovation" (RRI) seeks to integrate social, ethical, economic, and political dimensions with green chemistry's technical and environmental focus [27]. This approach recognizes that solving sustainability challenges requires interdisciplinary cooperation and systems thinking [28] [27].

Future directions in green chemistry include:

- Integration with One Health approach: This unified perspective recognizes the interconnectedness of human, animal, and environmental health, particularly in developing pharmaceuticals for vector-borne diseases [22].

- Advanced computational tools: Machine learning and artificial intelligence are increasingly being deployed to predict reaction outcomes, optimize conditions, and identify greener synthetic pathways [25] [28].

- Sustainable chemistry metrics harmonization: Efforts are underway to standardize and harmonize metrics across different sectors to facilitate decision-making throughout the value chain [28].

- Interdisciplinary collaboration: Addressing complex sustainability challenges requires collaboration between chemists, toxicologists, process engineers, and social scientists [28].

The 2021 Sustainable Chemistry Research and Development Act in the United States represents significant policy support for these initiatives, mandating the development of a comprehensive federal strategy for advancing sustainable chemistry [28]. As green chemistry continues to evolve, its principles provide a enduring framework for designing chemical products and processes that support both human well-being and environmental sustainability.

The institutionalization of green chemistry represents a pivotal shift in the chemical sciences, transitioning from a concept focused on pollution cleanup to a proactive framework for designing safer, more efficient chemical processes and products. This transformation was formally realized through the establishment of two key institutions: the Green Chemistry Institute (GCI) and the Presidential Green Chemistry Challenge Awards (GCCA). These institutions emerged in the 1990s as tangible manifestations of a growing consensus among chemists that environmental protection could be achieved most effectively through fundamental design rather than end-of-pipe remediation [29]. This institutional framework provided the infrastructure necessary to advance green chemistry from theoretical principles to practical applications across academic, industrial, and governmental sectors, creating a foundation for the ongoing evolution of sustainable chemistry practices worldwide [10].

Historical Context and Driving Forces

The development of green chemistry as a formal discipline occurred within a specific historical context marked by growing environmental awareness and regulatory evolution.

The Regulatory and Environmental Landscape

The 1960s through the 1980s witnessed a series of environmental milestones that set the stage for green chemistry's emergence:

- 1962: Rachel Carson's Silent Spring documented the detrimental effects of chemical pesticides, catalyzing public environmental consciousness [9] [29].

- 1970: The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was established, with its first major action being the ban of DDT and other chemical pesticides [29].

- 1980s: A paradigm shift occurred from pollution control to pollution prevention, with international bodies like the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) recommending cooperative changes to chemical processes [9] [29].

- 1988: The Office of Pollution Prevention and Toxics was established within the EPA, signaling an institutional commitment to preventative approaches [29].

This regulatory evolution created both the imperative and the infrastructure necessary for green chemistry's formalization.

Foundational Intellectual Framework

The intellectual foundation of green chemistry was codified in the 1990s through several key developments:

- 1991: The phrase "Green Chemistry" was officially coined by staff at the EPA Office of Pollution Prevention and Toxics [29].

- 1994: The first symposium, "Benign by Design: Alternative Synthetic Design for Pollution Prevention," was held in Chicago, sponsored by the ACS Division of Environmental Chemistry [29].

- 1998: Paul Anastas and John C. Warner co-authored Green Chemistry: Theory and Practice, outlining the 12 Principles of Green Chemistry that would become the field's philosophical guide [29].

These developments established the conceptual framework that would guide both the GCI and GCCA in their missions to advance sustainable chemistry.

Founding and Evolution of the Green Chemistry Institute (GCI)

Establishment as an Independent Nonprofit (1997)

The Green Chemistry Institute was founded in 1997 as an independent not-for-profit organization dedicated to promoting and advancing green chemistry [29]. The founding directors were:

- Dr. Joe Breen: A retired 20-year staff member of the EPA who became the Institute's first director [29].

- Dr. Dennis Hjeresen: A researcher at the Los Alamos National Laboratory who co-founded the institute [29].

The founding committee was chaired by Paul Anastas and included Joe Desimone (University of North Carolina), Bill Tumas (DuPont), and Sid Chao (Hughes Environmental) [29]. This diverse composition—spanning government, academia, and industry—reflected the institute's commitment to cross-sector collaboration from its inception.

Key Early Initiatives

In its initial years, the GCI launched several foundational programs:

- Green Chemistry & Engineering Conference (1997): Established to convene the growing green chemistry community and highlight GCCA winners [29]. The first conference attracted approximately 150 participants and was held at the National Academies headquarters in Washington, DC [29].

- First Education Summit (1999): Organized in collaboration with the University of Massachusetts, Boston, leading to a compendium of laboratory experiences illustrating green chemistry principles in undergraduate labs [29].

Integration into the American Chemical Society (2001)

Following Joseph Breen's passing in 2000, the EPA and ACS agreed to merge the GCI under the ACS umbrella [29]. In 2001, the GCI officially became part of the American Chemical Society, the world's largest professional scientific society [29]. This institutionalization within ACS signaled that green chemistry was gaining prominence as an essential part of chemistry's toolkit [29]. Nina McClelland, ACS Board Chair at the time, was instrumental in this arrangement, and Dennis Hjeresen was appointed Director of the ACS GCI [29].

Expansion and Sector-Specific Initiatives

Under ACS stewardship, the GCI expanded its influence through specialized industrial partnerships:

- 2005: The ACS GCI established its first Industrial Roundtable for the pharmaceutical industry to catalyze and enable green chemistry in chemical businesses [29].

- Subsequent roundtables were established for various sectors, including the Oilfield Chemistry Roundtable and Natural Polymers Consortium [29].

- These roundtables have awarded hundreds of thousands of dollars in green chemistry research grants and developed practical tools like the Reagent Guide to inform users about greener reagents for chemical transformations [30].

Table: Evolution of the Green Chemistry Institute

| Year | Milestone | Key Figures | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1997 | Founded as independent nonprofit | Joe Breen, Dennis Hjeresen, Paul Anastas | Established dedicated organization for green chemistry advancement |

| 1997 | Launched GC&E Conference | Paul Anastas, Joseph Breen | Created central gathering place for community knowledge-sharing |

| 1999 | First Education Summit | GCI & UMass Boston | Integrated green chemistry into academic curricula |

| 2001 | Merged with ACS | Nina McClelland, Dennis Hjeresen | Institutionalized within world's largest chemical society |

| 2005 | First Industrial Roundtable | ACS GCI | Established industry-academia collaboration model |

Creation and Impact of the Presidential Green Chemistry Challenge Awards

Establishment and Governance

The Presidential Green Chemistry Challenge Awards were established in 1995 when the EPA received support from President Bill Clinton to create an annual awards program highlighting scientific innovations in academia and industry that advanced Green Chemistry [29]. The program was designed to "recognize and promote innovative chemical technologies that prevent pollution and have broad applicability in the industry" [10].

Award Categories and Recognition Criteria

The GCCA recognizes innovations across multiple categories that demonstrate the application of green chemistry principles:

- Greener Synthetic Pathways

- Greener Reaction Conditions

- Design of Greener Chemicals

- Small Business

- Academic

- Specific Environmental Benefit: Climate Change (added in more recent years) [31]

Winning technologies must reduce or eliminate the use or generation of hazardous substances, demonstrate innovation, offer broad applicability, and provide economic benefits [32].

Evolution of Award-Winning Technologies

The GCCA has tracked the evolving focus of green chemistry applications over its history. Recent winners illustrate the field's expanding scope and sophistication:

Table: Representative Green Chemistry Challenge Award Winners (2020-2025)

| Year | Winner | Category | Innovation | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2025 | Keary M. Engle, Scripps Research | Academic | Air-stable nickel(0) catalysts | Replaces precious metals, eliminates need for energy-intensive inert-atmosphere storage [33] |

| 2025 | Merck & Co., Inc. | Greener Synthetic Pathways | Nine-enzyme biocatalytic cascade for islatravir | Replaced 16-step synthesis with single aqueous process [33] |

| 2025 | Future Origins | Specific Environmental Benefit: Climate Change | Non-palm C12/C14 fatty alcohols via fermentation | 68% lower global warming potential vs. palm kernel oil-derived equivalents [33] [32] |

| 2024 | Merck & Co., Inc. | Greener Synthetic Pathways | Continuous manufacturing process for KEYTRUDA | Improved efficiency in biologics manufacturing [31] |

| 2023 | Solugen | Greener Synthetic Pathways | Enzyme-based chemical production from renewable resources | Decarbonization of commodity chemicals [31] |

| 2022 | Cornell University (Song Lin) | Academic | Electrochemical synthesis of complex molecules | More efficient pharmaceutical intermediate production [31] |

| 2021 | Clemson University (Srikanth Pilla) | Academic | Nonisocyanate polyurethane (NIPU) foam | Eliminates hazardous isocyanates [31] |

| 2020 | Genomatica | Greener Synthetic Pathways | Biobased butylene glycol | Renewable replacement for petroleum-derived chemical [31] |

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols in Green Chemistry

Green chemistry methodologies have evolved significantly, with several approaches becoming particularly impactful. The following experimental protocols represent key methodologies that have received recognition through the GCCA program.

Enzyme Cascade Engineering for Pharmaceutical Synthesis

Representative Example: Merck's Nine-Enzyme Biocatalytic Cascade for Islatravir [33]

- Objective: Develop a streamlined, sustainable synthesis for the investigational antiviral islatravir

- Original Process: 16-step chemical synthesis requiring multiple isolations and organic solvents

- Green Chemistry Solution: Single biocatalytic cascade involving nine engineered enzymes

- Experimental Protocol:

- Enzyme Selection and Engineering: Identified and optimized enzymes through collaboration with Codexis using protein engineering techniques

- Reaction Optimization: Established optimal conditions for all nine enzymes to function sequentially in a single vessel

- Process Integration: Developed continuous processing without intermediate workups, isolations, or organic solvents

- Scale-up: Demonstrated process on 100 kg scale for commercial production

- Key Green Chemistry Principles: Waste prevention, safer solvents, design for energy efficiency, use of renewable feedstocks

Alternative Catalyst Development for Synthetic Chemistry

Representative Example: Air-Stable Nickel(0) Catalysts for Coupling Reactions [33]

- Objective: Develop practical, scalable nickel catalysts to replace precious metals

- Technical Challenge: Traditional nickel catalysts require energy-intensive inert-atmosphere handling

- Green Chemistry Solution: Novel nickel complexes combining high reactivity with air stability

- Experimental Protocol:

- Ligand Design: Synthesized specialized ligands that stabilize Ni(0) against oxidation while maintaining reactivity

- Electrochemical Synthesis: Developed alternative preparation method avoiding excess flammable reagents

- Activation Studies: Established conditions for generating catalytically active species under standard conditions

- Substrate Scope Evaluation: Tested performance across diverse carbon-carbon and carbon-heteroatom bond formations

- Key Green Chemistry Principles: Inherently safer chemistry, accident prevention, catalysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Key Reagent Solutions in Modern Green Chemistry

| Reagent/Technology | Function | Green Chemistry Advantage |

|---|---|---|

| Air-Stable Nickel Complexes [33] | Catalyze cross-coupling reactions | Replace precious metals (palladium); eliminate need for energy-intensive inert-atmosphere handling |

| Engineered Enzyme Systems [33] | Biocatalytic synthesis | Enable multistep transformations in single pot with high specificity; reduce solvent waste |

| Electrochemical Synthesis [33] | Reagent-free oxidation/reduction | Avoid stoichiometric oxidants/reductants; enable safer reaction conditions |

| Supercritical Water [31] | Reaction medium for biomass processing | Replace organic solvents; utilize renewable feedstocks |

| Non-Isocyanate Polyurethane Chemistry [31] | Polymer production | Eliminate use of highly toxic isocyanate starting materials |

| Bio-Based Feedstocks [31] | Renewable carbon sources | Reduce dependence on petroleum; utilize sustainable resources |

Institutional Impact and Current Landscape

Global Propagation and Recognition

The institutional foundation provided by the GCI and GCCA has facilitated global adoption of green chemistry principles:

- International Organizations: Green chemistry groups, journals, and conferences have launched worldwide, including:

- Academic Integration: Educational and research curricula became available at all levels, with the first Ph.D. program in green chemistry established at the University of Massachusetts Boston in 1997 [29].

- Scientific Recognition: Nobel Prizes in Chemistry in 2001 (asymmetric catalysis) and 2005 (metathesis) highlighted research areas aligned with green chemistry principles, further validating the field [29].

Current Challenges and Future Directions

Despite significant progress, challenges remain in the full adoption of green chemistry:

- Current Limitations: Nearly 90% of feedstocks used to make chemicals are still derived from fossil sources [29].

- Research Frontiers: Green chemists and engineers are increasingly focusing on:

- Circular Economy Models: Technologies like Pure Lithium Corporation's Brine to Battery method for closed-loop lithium-metal battery production [33]

- Carbon Utilization: Processes like Air Company's AIRMADE technology that converts CO₂ to sustainable aviation fuels [31]

- Toxics Reduction: Innovations like Cross Plains Solutions' SoyFoam that eliminates PFAS in firefighting foams [33]

- Measurement and Metrics: Continued development of standardized metrics to quantify the environmental and economic benefits of green chemistry innovations.

The GCI and GCCA continue to evolve to address these challenges, maintaining their role as central coordinating institutions for the global green chemistry community.

Institutionalization Timeline of Green Chemistry

Principles in Practice: Methodologies for Integrating Sustainable Chemistry into Pharmaceutical R&D

The evolution of the sustainable chemistry movement has fundamentally reshaped how chemists approach molecular synthesis. From the seminal publication of Rachel Carson's Silent Spring in 1962, which ignited public and scientific awareness of chemical pollution, to the U.S. Pollution Prevention Act of 1990, which established a national policy favoring pollution prevention over end-of-pipe treatment, the regulatory and philosophical landscape has progressively emphasized inherent hazard reduction [9] [18]. This trajectory culminated in the 1990s with the formalization of Green Chemistry as a distinct field. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency's (EPA) staff coined the term "Green Chemistry," and the field was codified with the 1998 publication of Green Chemistry: Theory and Practice by Paul Anastas and John C. Warner, which introduced the Twelve Principles of Green Chemistry [9] [16] [18]. These principles provide a framework for designing chemical products and processes that reduce or eliminate the use and generation of hazardous substances.

A cornerstone of this philosophy is the redesign of synthetic methodologies to avoid traditional environmental and health burdens, with solvent reduction being a critical target. Conventional solution-phase synthesis relies heavily on volatile organic solvents, which account for a significant portion of the waste and energy footprint in sectors such as pharmaceuticals [34]. In this context, mechanochemistry—which uses mechanical force to drive reactions in the solid state or with minimal liquid—has emerged as a powerful solvent-free alternative. It aligns directly with multiple Green Chemistry principles, including waste prevention, safer solvents, and energy efficiency [35] [18]. This whitepaper provides a technical guide for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to integrate mechanochemistry into core synthetic strategies, framed within the historical context of the sustainable chemistry movement.

Mechanochemistry: Core Principles and Green Chemistry Alignment

Mechanochemistry involves the use of mechanical energy to induce chemical transformations, bypassing the need for molecular solvents to dissolve reactants. This energy is typically delivered through grinding, milling, or extrusion, leading to intimate mixing and increased reactivity between solid reagents [35]. The primary equipment includes:

- Mixer Mills: Jars containing ball bearings are rapidly shaken back and forth, generating impact and frictional forces.

- Planetary Ball Mills: Jars are spun to generate centrifugal force, pressing balls against reactants for larger gram-scale reactions.

- Simpler Tools: For some applications, a mortar and pestle or twin-screw extruders can be effective [35].

This approach offers a paradigm shift from traditional solvothermal methods, often resulting in shorter reaction times, room-temperature operation, and unique product selectivity [35]. The following diagram illustrates the core conceptual workflow of a mechanochemical synthesis.

The green chemistry advantages of this solvent-free approach are quantitative and significant, as shown in the following comparison of key environmental metrics.

Table 1: Quantitative Green Chemistry Advantages of a Model Mechanochemical Synthesis [36]

| Green Chemistry Metric | Traditional Solution-Based Method | Mechanochemical Method | Improvement Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reaction Time | 0.5 - 4 hours | 10 minutes | ~3-24x faster |

| Temperature | Often requires heating | Room temperature | Energy saving |

| Solvent Volume | 1.5 mL per 0.5 mmol reactant | 0 mL (solvent-free) | 100% reduction |

| Catalyst/Additive | Often required (e.g., I₂, Cu, BiCl₃) | None (neat grinding) | 100% reduction |

| Isolated Yield | Up to 26% (in MeOH, no additive) | 92% | ~3.5x higher yield |

Detailed Experimental Protocols: A Case Study in Amination

Recent literature provides robust, optimized protocols for implementing mechanochemistry. The following section details a specific case study: the solvent-free, regioselective amination of 1,4-naphthoquinones to synthesize biologically relevant 2-amino-1,4-naphthoquinones [36]. This reaction showcases the efficiency and practicality of the method.

Reaction Scheme and Optimization

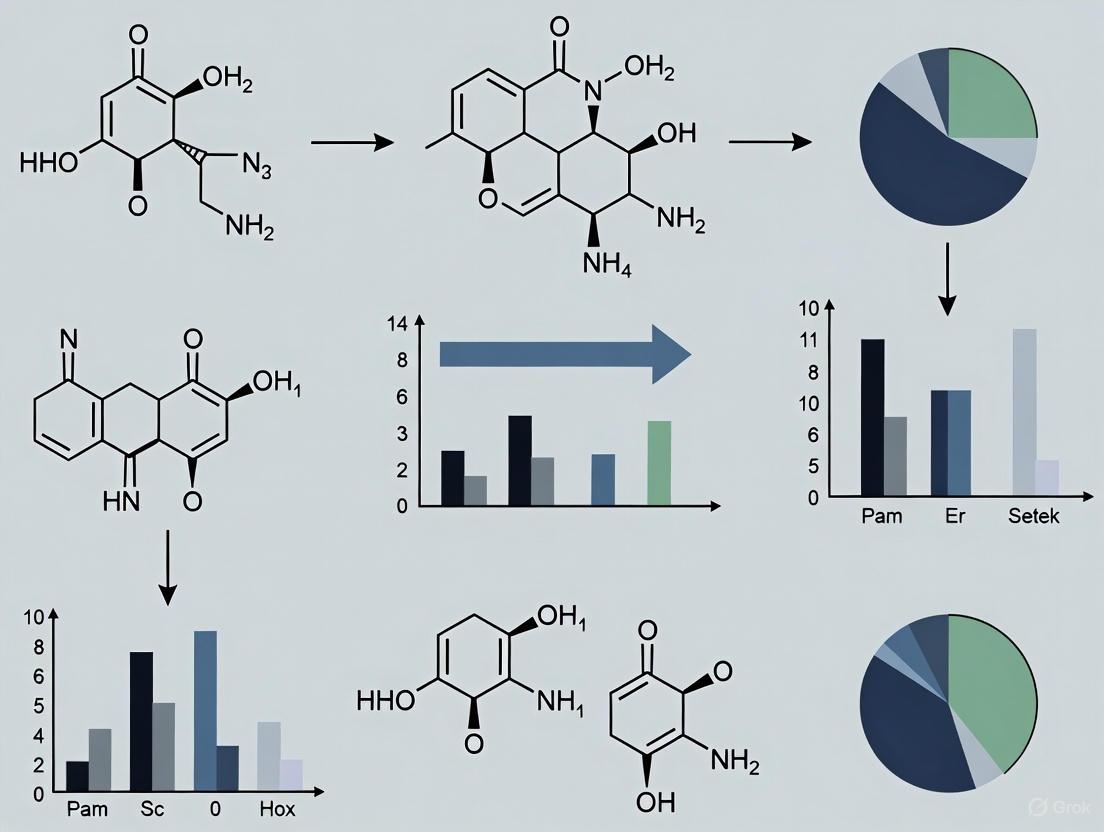

The general reaction involves the coupling of a 1,4-naphthoquinone with an amine to form a 2-amino-1,4-naphthoquinone derivative.

Synthetic Scheme: 1,4-Naphthoquinone (1) + Amine (2) → 2-Amino-1,4-naphthoquinone (3)

The optimization process for this mechanochemical reaction is summarized in the table below, which systematically evaluates different parameters to achieve maximum yield.

Table 2: Optimization Table for the Model Mechanochemical Amination [36]

| Entry | Solvent | Solid Surface | Conditions | Time (min) | Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | - | Neutral Alumina | Ball-milling (550 rpm) | 60 | - |

| 2 | - | Basic Alumina | Ball-milling (550 rpm) | 5 | 80 |

| 3 (Optimal) | - | Basic Alumina | Ball-milling (550 rpm) | 10 | 92 |

| 4 | - | Basic Alumina | Ball-milling (550 rpm) | 15 | 88 |

| 5 | - | Acidic Alumina | Ball-milling (550 rpm) | 10 | 28 |

| 6 | - | Silica / NaCl | Ball-milling (550 rpm) | 10 | Trace |

| 12-16 | Methanol / EtOH / etc. | - | Magnetic Stirring | 240 | 18-26 |

Step-by-Step Procedure

This protocol is adapted from the optimized conditions in [36].

- Loading Reactants: Place 1,4-naphthoquinone (1, 0.5 mmol) and the amine derivative (2, 0.5 mmol) into a 25 mL stainless-steel milling jar.

- Adding Grinding Media: Add basic alumina (1.5 g) as a solid surface to facilitate grinding and reaction. Introduce 7 stainless-steel balls (10 mm diameter) as the grinding media.

- Milling: Securely fasten the jar in a high-speed ball mill. Process the mixture at a frequency of 550 rpm for 10 minutes. The mill can be programmed to operate with a brief pause (e.g., 5 seconds) every 2.5 minutes to prevent overheating.

- Work-up & Isolation: After milling, open the jar. The product (3) is isolated from the basic alumina solid surface via column chromatography or trituration. A key advantage is the reusability of the basic alumina surface for subsequent reactions, enhancing the method's green credentials.

- Characterization: Characterize the final product using standard techniques, including ( ^1 \text{H} ) NMR, ( ^{13} \text{C} ) NMR, and HRMS, to confirm structure and purity [36].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Success in mechanochemical synthesis depends on the appropriate selection of equipment and materials. The following table details the key components of a mechanochemistry toolkit.

Table 3: Essential Materials and Equipment for Mechanochemical Research

| Item / Reagent | Function / Role in Synthesis | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Planetary Ball Mill | Applies mechanical energy via centrifugal force; ideal for gram-scale reactions and screening. | Allows control over rotational speed and time; jars available in various materials [35]. |

| Mixer Mill | Applies energy via high-frequency shaking; useful for smaller-scale, high-impact reactions. | Typically uses smaller jars and is efficient for rapid screening [35]. |

| Grinding Jars | Contain the reaction mixture. | Material choice (e.g., stainless steel, tungsten carbide, ceramic) depends on required chemical inertness and mechanical strength [36]. |

| Grinding Media (Balls) | Transmit mechanical energy to reactants through impact and friction. | Size, number, and material (e.g., steel, ceramic) are critical optimization parameters [36]. |

| Basic Alumina | Acts as a solid grinding auxiliary and heterogeneous base catalyst. | Promotes reactions in the absence of soluble catalysts; can be reused [36]. |

| Stainless-Sel Jars/Balls | Standard, robust equipment for most organic syntheses. | Provides high density for efficient energy transfer. pH of basic alumina suspension: ~8.01 [36]. |