From Principles to Practice: Key Milestones in Green Chemistry Reshaping Drug Development

This article traces the pivotal milestones in the development of green chemistry, from its foundational principles established in the 1990s to the cutting-edge methodologies and metrics driving sustainable innovation in...

From Principles to Practice: Key Milestones in Green Chemistry Reshaping Drug Development

Abstract

This article traces the pivotal milestones in the development of green chemistry, from its foundational principles established in the 1990s to the cutting-edge methodologies and metrics driving sustainable innovation in pharmaceutical research and development today. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the origins of the field, examines modern applications like solvent-free synthesis and renewable feedstocks, details troubleshooting metrics for process optimization, and validates progress through comparative case studies from leading pharmaceutical companies. The synthesis of these elements provides a comprehensive framework for understanding how green chemistry principles are actively reducing environmental impact, improving efficiency, and creating a more sustainable future for biomedical science.

The Origins of Green Chemistry: From Pollution Prevention to a Molecular Framework for Sustainability

The Pollution Prevention Act (PPA) of 1990 marks a foundational milestone in the development of green chemistry research, establishing a decisive policy-driven shift from pollution control to pollution prevention. Prior to its enactment, United States environmental policy was largely characterized by a reactive, end-of-pipe approach focused on treating and managing pollution after it had been created [1] [2]. The PPA legislatively reoriented this strategy by declaring it the national policy of the United States that pollution should be prevented or reduced at the source whenever feasible [3]. This policy declaration provided the essential impetus for developing the principles and practices of green chemistry, creating a framework where preventing hazards at the molecular level became a national priority. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this act represents the critical juncture where policy began to explicitly favor innovative molecular design over waste management, fundamentally altering the context for chemical research and development.

The Legislative Foundation: Core Provisions of the PPA

The Pollution Prevention Act established a clear, hierarchical policy for environmental management, prioritizing source reduction as the most desirable approach, followed by recycling, treatment, and finally, disposal or release as a last resort [3] [4]. This hierarchy is central to understanding the Act's catalytic effect on green chemistry.

Key Definitions and National Policy

The Act provided crucial definitions that have since become cornerstones of sustainable chemistry practices:

- Source Reduction: The Act defines this as any practice that reduces the amount of any hazardous substance, pollutant, or contaminant entering any waste stream or released into the environment prior to recycling, treatment, or disposal. It explicitly includes equipment or technology modifications, process or procedure modifications, reformulation or redesign of products, substitution of raw materials, and improvements in housekeeping, maintenance, training, or inventory control [3] [5].

- Multimedia Approach: The Act recognized that pollutants move across environmental media (air, water, land), mandating a comprehensive approach rather than managing single media in isolation [3].

The congressional findings noted that source reduction opportunities were often not realized because existing regulations focused industrial resources on treatment and disposal, creating a significant barrier to innovation in prevention [3].

Mandated EPA Programs and Mechanisms

To implement the new national policy, the PPA mandated specific actions and programs within the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), creating the infrastructure to support the emerging field of green chemistry.

Table 1: Key Programs Mandated by the Pollution Prevention Act of 1990

| Program Element | Description | Significance for Green Chemistry Research |

|---|---|---|

| Office of Pollution Prevention | An independent office within EPA directed to develop and implement a strategy to promote source reduction [3] [2]. | Created an institutional home and champion for prevention-based approaches within the federal government. |

| Source Reduction Clearinghouse | A central repository to compile and disseminate information on management, technical, and operational approaches to source reduction [3]. | Facilitated technology transfer and provided researchers with access to data on successful prevention techniques. |

| State Matching Grants | Authorized grants to states to promote the use of source reduction techniques by businesses, fostering local technical assistance programs [3]. | Expanded the network of practitioners and support systems for implementing green chemistry innovations. |

| Toxic Chemical Reporting | Required facilities that report toxic chemical releases to also include a toxic chemical source reduction and recycling report [3]. | Generated valuable data on industrial practices, highlighting successful source reduction case studies for further research. |

The PPA as a Catalyst for Green Chemistry Research

The policy framework of the PPA directly spurred the development and codification of green chemistry as a scientific discipline. The Act’s emphasis on preventing pollution "at the source" through "cost-effective changes in production, operation, and raw materials use" provided a clear research mandate for chemists and engineers [3] [6].

From Policy to Principles: The Birth of a Scientific Discipline

The conceptual link between the PPA and green chemistry is direct and unambiguous. As noted by the Yale Center for Green Chemistry, "The idea of green chemistry was initially developed as a response to the Pollution Prevention Act of 1990" [6]. The Act's focus on improved design—including cost-effective changes in products, processes, and use of raw materials—provided the philosophical and policy foundation upon which the 12 Principles of Green Chemistry were later built [7] [6]. These principles, formalized in 1998 by Paul Anastas and John Warner, provide the experimental and design framework for practicing chemists to operationalize the PPA's mandate, translating a broad policy goal into actionable scientific protocols.

Key Federal Initiatives Spurred by the PPA

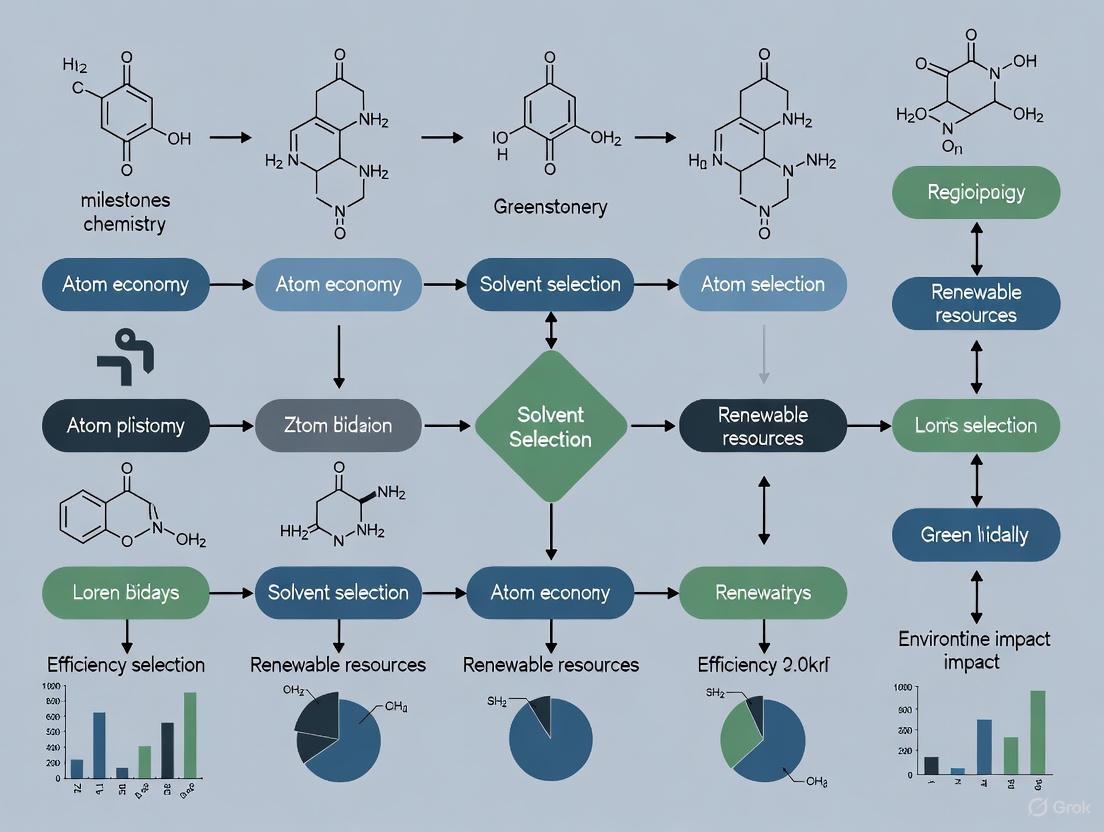

The following diagram illustrates the logical progression from the PPA's passage to key initiatives that advanced green chemistry research and implementation.

The EPA's implementation of the PPA led to several pivotal programs that directly supported green chemistry research and development:

- Presidential Green Chemistry Challenge Awards (1996): Established by the EPA as part of its PPA-mandated strategy, these awards have become a cornerstone of green chemistry, recognizing and disseminating success stories in both academic and industrial chemistry [6] [8].

- Design for the Environment (DfE) Program: Later evolving into the Safer Choice Label, this program was created to help manufacturers, including those in the pharmaceutical and consumer products sectors, identify safer chemical alternatives in their formulation processes [9].

- Green Chemistry Research Grants: In the early 1990s, the EPA's Office of Pollution Prevention and Toxics, in partnership with the National Science Foundation, launched a research grant program encouraging the redesign of existing chemical products and processes to reduce impacts on human health and the environment [6].

Quantitative Impact: Measuring the Success of a Policy Framework

The PPA's reporting requirements have generated decades of data, allowing researchers and policymakers to track trends in source reduction and its outcomes. The following table summarizes key quantitative outcomes associated with the implementation of the PPA and the green chemistry programs it inspired.

Table 2: Measurable Outcomes of PPA Implementation and Related Green Chemistry Programs

| Metric Area | Reported Outcome | Context & Timeline |

|---|---|---|

| Toxic Chemical Releases | 35% decline in total toxic chemicals released to the environment [2]. | Measured between 1988 and 1992, the early years of PPA implementation. |

| Federal Electronics Challenge | Saved over $230 million and reduced hazardous waste by over 9 million pounds [9]. | Documented savings over the lifetime of the program, which was rooted in PPA principles. |

| E3: Economy, Energy and Environment | Identified $42 million in energy cost savings and over $30 million in one-time cost savings for manufacturers [9]. | Federal technical assistance framework formed in 2009, demonstrating the economic benefits of P2. |

| State Grant Program | Awarded more than $30 million to over one hundred regional, state, and tribal organizations [2]. | Documented in the first four years of the PPA's state matching grant program. |

The Research and Developer's Toolkit: Operationalizing the PPA

For the scientific community, the PPA's legacy is a suite of methodologies, assessment tools, and reagent guides that translate policy into practical laboratory and process development.

Experimental and Assessment Protocols

The PPA framework has been operationalized through several key methodological approaches:

- Source Reduction Auditing: The PPA specifically mandated the EPA to "develop, test and disseminate model source reduction auditing procedures designed to highlight source reduction opportunities" [3]. These audits involve a systematic, multi-step review of chemical processes to identify reduction opportunities.

- Alternative Assessment (or Chemical Alternatives Assessment): A methodology rooted in the PPA's call for "substitution of raw materials" [3]. It provides a structured process for comparing alternatives to chemicals of concern based on their hazards, performance, and economic viability. This is a critical protocol for drug development professionals seeking to design out hazards at the R&D phase.

- Life Cycle Thinking (LCT): While not explicitly named in the PPA, the Act's multimedia approach naturally leads to life cycle considerations. LCT is an overarching protocol that evaluates the environmental impacts of a product or process from raw material extraction through manufacturing, use, and disposal.

Key Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

The following table details key tools and resources, born from the PPA's influence, that are essential for researchers working in green chemistry and sustainable drug development.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Green Chemistry & Drug Development

| Tool/Resource | Function in Green Chemistry Research | Policy Connection |

|---|---|---|

| Safer Chemical Ingredients List (SCIL) | A list of chemical ingredients evaluated and determined to meet the EPA Safer Choice Program's criteria for safer ingredients. Serves as a primary reference for chemists seeking safer starting materials [9]. | Directly resulted from the evolution of the DfE/Safer Choice program, which was established under the PPA's policy umbrella. |

| Safer Solvents and Auxiliaries | Solvents such as water, supercritical CO₂, and bio-based solvents (e.g., limonene, ethyl lactate) that replace hazardous VOCs and chlorinated solvents. Their selection is guided by Principle #5 of the 12 Principles [7]. | The PPA's definition of source reduction includes "equipment or technology modifications" and "substitution of raw materials," driving innovation in solvent technology [3]. |

| Catalysts (Heterogeneous, Biocatalysts) | Catalysts, especially recoverable heterogeneous catalysts and enzymatic biocatalysts, are used to minimize waste, reduce energy consumption, and increase selectivity, aligning with Principle #9 [7]. | The use of catalysts directly enables the PPA goal of reducing "the amount of any hazardous substance... released into the environment" by making syntheses more efficient [3]. |

| Renewable Feedstocks | Starting materials derived from biomass (e.g., sugars, plant oils, chitin) instead of depleting fossil fuels. Their use is a core aspect of Principle #7 [7]. | The PPA encourages "reformulation or redesign of products" and "substitution of raw materials," creating a policy driver for the development of bio-based feedstocks [3]. |

| The 12 Principles of Green Chemistry | A comprehensive design framework that functions as a decision-making tool for researchers at the molecular level, guiding the design of safer chemicals, syntheses, and products [7]. | The principles are the direct scientific response to the PPA's high-level policy goal of preventing pollution "at the source" [6]. |

The Pollution Prevention Act of 1990 stands as a testament to the power of policy to catalyze scientific innovation. By establishing source reduction as a national priority, it provided the essential foundation upon which the entire edifice of green chemistry has been built. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the PPA is not merely a historical footnote but the enabling legislation that frames their work in designing safer molecular structures and more sustainable processes. The Act's most significant achievement is the creation of a self-reinforcing cycle where policy mandates new scientific approaches, and scientific advances, in turn, inform and justify further policy development, as seen in the recent Sustainable Chemistry Research and Development Act of 2021 [8]. The PPA successfully ignited a transformation in chemical research, shifting the paradigm from managing hazard to designing it out of the molecular fabric of our economy.

The formal coining of the term "green chemistry" in the 1990s represents a pivotal milestone in the evolution of chemical research, marking a fundamental shift from pollution remediation to pollution prevention. This new philosophy emerged from a confluence of growing environmental awareness, regulatory changes, and scientific innovation that collectively addressed the unsustainable nature of traditional chemical processes [10]. The approach is distinct from environmental chemistry; rather than focusing on the environmental fate and remediation of pollutants, green chemistry seeks to design chemical products and processes that inherently minimize or eliminate the generation of hazardous substances [11] [7]. This paradigm was crystallized through the seminal work of Paul Anastas and John Warner, whose 12 principles provided a systematic framework for practicing chemistry in a more sustainable and environmentally responsible manner [12] [13].

The significance of this development extends across multiple dimensions of chemical research and industrial practice. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, green chemistry offers a proactive framework that aligns chemical innovation with environmental stewardship, creating opportunities for more efficient, economical, and safer chemical synthesis [10]. This article situates the formal birth of green chemistry within the broader context of sustainable development in the chemical sciences, tracing its historical origins, conceptual foundations, and practical implementation through specific case studies relevant to pharmaceutical and industrial applications.

Historical Context and Driving Forces

Precursors to a Formal Movement

The conceptual roots of green chemistry extend back to the environmental movement that gained momentum in the 1960s and 1970s. Key publications such as Rachel Carson's Silent Spring (1962) raised public awareness about the environmental consequences of chemical pesticides, while events like the 1972 Stockholm Conference established environmental protection as a global priority [10] [14]. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, legislation such as the Clean Air Act, Clean Water Act, and Toxic Substances Control Act in the United States created a regulatory framework for controlling pollution, though these primarily employed "command and control" and "end-of-pipe" approaches [15] [16].

During the 1980s, a significant policy shift toward pollution prevention began to take shape internationally. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) emphasized pollution prevention and control in its ministerial meetings, while the concept of "sustainable development" gained traction through the 1987 Brundtland Report [10] [15]. This evolving context set the stage for a more proactive approach to environmental management in the chemical industry, moving beyond remediation to prevention.

The Legislative Catalyst: Pollution Prevention Act of 1990

The Pollution Prevention Act of 1990, passed by the U.S. Congress, served as the critical legislative catalyst for the formal emergence of green chemistry [12] [7] [15]. This legislation established a national policy declaring that pollution "should be prevented or reduced at the source whenever feasible," a significant departure from previous end-of-pipe approaches [7]. The Act specifically endorsed source reduction as the preferred pollution prevention strategy, emphasizing changes to chemical product design and industrial processes rather than waste management after generation [7].

This legislative mandate prompted the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to develop new programs encouraging pollution prevention through chemical research and design. In 1991, the EPA's Office of Pollution Prevention and Toxics launched a research grant program focused on redesigning chemical products and processes, initially called "Alternative Synthetic Design for Pollution Prevention" [6] [15]. This program, developed in partnership with the National Science Foundation (NSF) and the Council for Chemical Research, provided the institutional foundation for what would soon be formally termed "green chemistry" [6] [15].

Table 1: Key Historical Milestones in the Development of Green Chemistry

| Year | Event | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| 1962 | Publication of Silent Spring | Raised public awareness of environmental damage from chemicals [14] |

| 1970 | Establishment of U.S. EPA | Created institutional framework for environmental protection [15] |

| 1985 | OECD Ministerial Meetings | Emphasized pollution prevention over end-of-pipe control [15] |

| 1990 | Pollution Prevention Act | Mandated pollution prevention as national U.S. policy [7] |

| 1991 | EPA's research grant program | First federal program funding pollution prevention chemistry [6] |

| 1996 | Presidential Green Chemistry Challenge Awards | Recognized and promoted innovative green technologies [10] |

| 1997 | Green Chemistry Institute (GCI) founded | Non-profit organization to promote green chemistry [10] |

| 1998 | Publication of Green Chemistry: Theory and Practice | Formally established the 12 principles of green chemistry [12] |

Conceptual Foundations: The 12 Principles of Green Chemistry

Systematic Framework Development

In 1998, Paul Anastas (then director of the Green Chemistry Program at the U.S. EPA) and John Warner (then of Polaroid Corporation) published Green Chemistry: Theory and Practice, which formally introduced the 12 principles of green chemistry [12] [13] [10]. These principles provided a comprehensive framework for designing chemical products and processes that reduce or eliminate the use and generation of hazardous substances, addressing environmental concerns across the entire chemical life cycle [11] [7].

The principles encompass a range of strategies from molecular design to process optimization, collectively providing guidance for implementing green chemistry across research and industrial settings. Rather than representing a distinct subdiscipline of chemistry, the principles apply across all chemical fields, offering a new philosophical approach to chemical design and synthesis [12] [7].

Table 2: The 12 Principles of Green Chemistry and Their Research Applications

| Principle | Core Concept | Research Applications |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Prevention | Prevent waste rather than treat or clean up | One-pot syntheses to eliminate purification steps [12] |

| 2. Atom Economy | Maximize incorporation of materials into final product | High-atom economy reactions (e.g., Diels-Alder) [13] |

| 3. Less Hazardous Syntheses | Use/generate non-toxic substances | Predictive toxicology tools (GenRA, ToxCast) [12] |

| 4. Designing Safer Chemicals | Preserve efficacy while reducing toxicity | Structure-activity relationship (SAR) analysis [13] |

| 5. Safer Solvents & Auxiliaries | Avoid auxiliary substances or use safe ones | Solvent-free mechanochemistry, water-based reactions [12] |

| 6. Design for Energy Efficiency | Minimize energy requirements | Room temperature/pressure reactions [11] |

| 7. Renewable Feedstocks | Use renewable raw materials | Biomass-derived chemicals [11] |

| 8. Reduce Derivatives | Avoid protecting groups | Click chemistry for selective reactions [12] |

| 9. Catalysis | Prefer catalytic over stoichiometric reagents | Metathesis catalysts, biocatalysts [12] |

| 10. Design for Degradation | Break down to innocuous products | Biodegradable polymers with enzyme additives [12] |

| 11. Real-time Analysis | Monitor processes to prevent hazards | In-process monitoring to control byproduct formation [11] |

| 12. Inherently Safer Chemistry | Minimize accident potential | Non-flammable, non-explosive materials [11] |

Foundational Philosophy and Implementation Strategy

The 12 principles collectively embody a preventative approach to environmental management in chemistry, with the first principle—"It is better to prevent waste than to treat or clean up waste after it has been created"—serving as the cornerstone upon which the others build [13]. This philosophy represents a fundamental reorientation of chemical practice, prioritizing prospective hazard prevention over retrospective pollution control [6].

For research scientists and drug development professionals, implementing these principles involves considering environmental and health impacts at the earliest stages of molecular design and process development. This approach often requires new metrics for evaluating chemical processes, such as atom economy (developed by Barry Trost in 1991) and E-factor (popularized by Roger Sheldon), which quantify the efficiency and waste generation of chemical reactions [13] [10]. These metrics provide tangible ways to apply the principles in both academic research and industrial settings, particularly in pharmaceutical development where complex syntheses often generate substantial waste.

Institutionalization and Research Applications

Key Institutional Drivers

The institutionalization of green chemistry throughout the 1990s played a crucial role in establishing it as a legitimate scientific field. Several key initiatives provided the infrastructure for research, education, and implementation:

- Presidential Green Chemistry Challenge Awards (1996): Established to recognize and promote innovative chemical technologies that prevent pollution, these awards highlighted both academic and industrial successes in green chemistry [6] [10].

- Green Chemistry Institute (1997): Founded as a non-profit organization to promote and advance green chemistry, the GCI joined the American Chemical Society in 2001, signaling broader acceptance within the chemical community [10] [16].

- Academic Journals and Conferences: The launch of the journal Green Chemistry by the Royal Society of Chemistry in 1999 and the establishment of dedicated conferences provided crucial venues for disseminating research [6] [15].

These institutional developments created a supportive ecosystem for green chemistry research, facilitating collaboration between academia, industry, and government agencies.

Representative Experimental Protocols and Case Studies

Pharmaceutical Case Study: One-Pot Synthesis

Background: Traditional multi-step pharmaceutical syntheses often involve extensive isolation and purification between steps, generating significant waste. The one-pot synthesis approach addresses this inefficiency by designing sequential reactions to occur in a single vessel without intermediate workup [12].

Protocol for One-Pot Synthesis:

- Reaction Design: Identify compatible reaction conditions (solvent, temperature, pH) for multiple sequential transformations. Computational modeling may be used to predict reaction pathways and byproducts.

- Reagent Selection: Choose catalysts and reagents that facilitate multiple steps without cross-interference. Catalysts with orthogonal reactivity are ideal.

- Process Optimization: Establish addition sequences and timing for reagents to maximize yield and minimize byproducts. Real-time analytical monitoring (e.g., in-situ IR spectroscopy) can track reaction progress.

- Workup and Purification: Develop efficient isolation methods that minimize solvent use and waste generation.

Application Example: Amgen's synthesis of the lung cancer drug Lumakras (sotorasib) employed a one-pot approach that converted a less potent drug form into the more potent version without multiple isolation steps. This method eliminated approximately 14.4 million kg of waste annually compared to the traditional synthesis [12].

Solvent-Free Mechanochemistry

Background: Solvents traditionally account for the majority of waste in pharmaceutical and fine chemical production. Mechanochemistry uses mechanical energy rather than solvents to drive chemical reactions, significantly reducing waste generation [12] [17].

Ball Milling Protocol:

- Apparatus Setup: Place solid reactants and grinding media (e.g., steel balls) in a milling vessel. Control atmosphere if necessary (e.g., inert gas for air-sensitive compounds).

- Mechanical Activation: Initiate milling with precise control of frequency, time, and energy input. Parameters vary based on reactant properties and desired reaction.

- Reaction Monitoring: Use techniques like X-ray diffraction or solid-state NMR to track reaction progress without disrupting the system.

- Product Isolation: Simply wash the product from the milling vessel, often with minimal solvent required.

Application Example: Haber-Bosch reactions performed in ball mills instead of traditional high-pressure industrial methods offer a pathway to ammonia production with significantly lower carbon dioxide emissions [12].

Aqueous-Phase Catalytic Reactions

Background: Replacing organic solvents with water represents another strategy for greener synthesis, though this often requires specialized approaches to facilitate reactions between organic compounds in an aqueous environment [12].

Protocol for Aqueous Suzuki-Miyaura Cross-Coupling:

- Catalyst System Preparation: Use water-soluble catalysts, such as palladium complexes with hydrophilic ligands.

- Surfactant Addition: Incorporate micelle-forming compounds like polyoxyethanyl α-tocopheryl sebacate to create microenvironments that solubilize organic reactants.

- Reaction Conditions: Conduct coupling at mild temperatures (e.g., 38°C compared to >70°C for traditional methods).

- Product Recovery: Separate products through precipitation, extraction, or filtration as appropriate.

This method eliminates harmful solvents while also reducing energy requirements compared to traditional Suzuki-Miyaura reactions [12].

The Research Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methodologies

The implementation of green chemistry principles requires specialized reagents, catalysts, and methodologies that enable more sustainable chemical synthesis. The following toolkit highlights key solutions for researchers in pharmaceuticals and chemical development.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Green Chemistry Applications

| Reagent/Category | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Grubbs Catalysts | Olefin metathesis catalysts | Ring-closing metathesis, cross metathesis in organic synthesis [12] |

| Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) | Biodegradable solvent systems | Extraction of metals from e-waste, biomass processing [17] |

| Polyoxyethanyl α-tocopheryl sebacate | Surfactant for aqueous reactions | Enables Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling in water [12] |

| Choline chloride-urea mixture | Deep eutectic solvent | Sustainable alternative to ionic liquids in various applications [17] |

| Enzyme-based catalysts | Biocatalysis | Selective transformations under mild conditions [12] |

| Click chemistry reagents | Highly selective coupling | Bioconjugation, polymer synthesis without protecting groups [12] |

| Silver nanoparticles | Catalytic and antimicrobial agent | Green synthesis using plant extracts as reducing agents [14] |

| Supercritical CO₂ | Alternative solvent | Extraction and reaction medium replacing VOCs [11] |

The formal establishment of green chemistry in the 1990s created a paradigm shift that continues to influence chemical research and development. By providing a systematic framework for designing safer, more efficient chemical processes, green chemistry has moved from a niche concept to an integral part of sustainable chemical practice. The field's ongoing evolution—encompassing advancements in green solvents, catalytic systems, and renewable feedstocks—builds upon the foundation established during this formative period.

For contemporary researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the principles of green chemistry offer both a philosophical compass and practical toolkit for addressing the dual challenges of chemical innovation and environmental sustainability. As Paul Anastas noted, the ultimate success of green chemistry will be marked when the term becomes redundant—when all chemistry is inherently green [12]. The formal birth of green chemistry in the 1990s represents a crucial milestone toward achieving this goal, establishing a legacy that continues to shape the future of chemical research and development.

The 1998 publication of "Green Chemistry: Theory and Practice" by Paul Anastas and John Warner represents a foundational milestone in the evolution of sustainable chemistry [10]. This seminal work introduced a systematic framework that fundamentally reoriented chemical research and development from pollution cleanup to pollution prevention [18]. Prior to its publication, environmental protection in the chemical industry primarily focused on waste treatment and remediation—the "end-of-pipe" approach that often proved costly and inefficient [19] [18]. Anastas and Warner's work provided both a philosophical and practical foundation for designing chemical products and processes that reduce or eliminate the use and generation of hazardous substances [18]. The timing of this publication was pivotal, arriving after decades of growing environmental awareness sparked by events such as the 1962 publication of Rachel Carson's "Silent Spring" and the 1972 Stockholm Conference, yet at a moment when the chemical industry needed practical, implementable solutions [10] [14]. By codifying the now-famous 12 Principles of Green Chemistry, the book provided researchers, industrial chemists, and educators with a tangible roadmap for integrating sustainability into the molecular basis of chemical design [13] [14].

Historical Context and Development

The development of green chemistry as a formal discipline emerged from a convergence of environmental regulation, scientific advancement, and growing public concern about industrial pollution [10] [18]. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency launched its Green Chemistry Program in 1991, initially titled "Alternative Synthetic Routes for Pollution Prevention" [10]. This program reflected a shifting policy focus toward preventing pollution at its source rather than managing it after creation [18]. The formal establishment of the Presidential Green Chemistry Challenge Awards in 1995 created both recognition and incentive for industrial innovation [10] [18]. Within this context, Anastas and Warner's 1998 book provided the critical theoretical framework that unified these emerging practices into a coherent discipline [10]. The subsequent founding of the Green Chemistry Institute in 1997 (which joined the American Chemical Society in 2001) further institutionalized these principles through research collaboration and education [10] [18]. This historical progression—from environmental concern to regulatory action to theoretical framework—established the foundation upon which modern green chemistry research is built [14].

The Twelve Principles of Green Chemistry: Detailed Analysis

Anastas and Warner's twelve principles represent a comprehensive framework for designing chemical products and processes that minimize environmental impact and health risks [13]. These principles span the entire lifecycle of chemical products, from initial design to final disposal [19].

Table 1: The Twelve Principles of Green Chemistry with Descriptions and Applications

| Principle | Core Concept | Research Applications |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Prevention | Prevent waste rather than treat or clean up waste after it is formed [13]. | Designing synthetic pathways that minimize byproduct formation [19]. |

| 2. Atom Economy | Maximize incorporation of all materials used in process into final product [13]. | Developing rearrangement and addition reactions over substitutions [20]. |

| 3. Less Hazardous Chemical Syntheses | Design synthetic methods that use and generate non-toxic substances [13]. | Replacing toxic reagents with biodegradable alternatives [13]. |

| 4. Designing Safer Chemicals | Design chemical products to preserve efficacy while reducing toxicity [13]. | Molecular design that minimizes bioavailability of toxicophores [13]. |

| 5. Safer Solvents and Auxiliaries | Minimize use of auxiliary substances where possible [13]. | Using water or supercritical CO₂ instead of organic solvents [19]. |

| 6. Design for Energy Efficiency | Recognize environmental and economic impacts of energy consumption [19]. | Performing reactions at ambient temperature and pressure [19]. |

| 7. Use Renewable Feedstocks | Use renewable rather than depleting feedstocks [19]. | Developing processes based on biomass instead of petroleum [14]. |

| 8. Reduce Derivatives | Avoid unnecessary derivatization that requires additional reagents [19]. | Developing protecting-group-free synthesis [19]. |

| 9. Catalysis | Prefer catalytic reagents over stoichiometric reagents [19]. | Using enantioselective catalysts for chiral synthesis [20]. |

| 10. Design for Degradation | Design chemical products to break down into innocuous degradation products [19]. | Developing biodegradable polymers and chemicals [14]. |

| 11. Real-time Analysis for Pollution Prevention | Develop analytical methodologies for real-time, in-process monitoring [19]. | Implementing process analytical technology (PAT) in manufacturing [19]. |

| 12. Inherently Safer Chemistry for Accident Prevention | Choose substances that minimize potential for chemical accidents [19]. | Replacing volatile solvents with ionic liquids or safer alternatives [19]. |

Foundational Principles: Prevention and Atom Economy

The first principle of Prevention establishes the fundamental tenet that it is economically and environmentally superior to prevent waste formation rather than manage it after creation [13]. This principle has driven the development of Process Mass Intensity (PMI) as a key metric in pharmaceutical chemistry, where dramatic reductions in waste—sometimes as much as ten-fold—have been achieved through conscious process redesign [13]. The second principle of Atom Economy, developed by Barry Trost, asks chemists to consider what atoms of the reactants are incorporated into the final desired product and what atoms are wasted [13] [20]. This principle challenges the traditional focus on percent yield alone by emphasizing the incorporation efficiency of starting materials [13]. For example, a reaction with 100% yield but only 50% atom economy means half the mass of reactant atoms is wasted in unwanted by-products [13]. These two principles work in tandem to address both the quantity and intrinsic efficiency of chemical processes.

Hazard Reduction Principles: Safer Chemicals and Solvents

Principles 3, 4, and 5 focus on reducing hazards throughout the chemical process [13]. The call for Less Hazardous Chemical Syntheses acknowledges that while reactive chemicals are often necessary for molecular transformations, chemists should broaden their definition of "good science" to include consideration of all substances in a reaction flask, not just the target transformation [13]. The principle of Designing Safer Chemicals requires an understanding of both chemistry and toxicology to create products that maintain efficacy while reducing toxicity [13]. This approach recognizes that hazard is a design flaw that must be addressed at the molecular design stage [13]. The principle of Safer Solvents and Auxiliaries addresses the reality that solvents and separation agents often constitute the bulk of material input in chemical processes and thus represent significant waste and exposure concerns [13] [19].

Quantitative Metrics for Green Chemistry Assessment

The implementation of green chemistry principles requires robust metrics to evaluate and compare chemical processes [19]. Several key metrics have been developed to quantify the environmental and efficiency profiles of chemical reactions and processes.

Table 2: Key Metrics for Evaluating Green Chemical Processes

| Metric | Calculation | Interpretation | Ideal Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atom Economy [19] | (FW of desired product / Σ FW of all reactants) × 100 | Percentage of reactant atoms incorporated into final product | 100% |

| E-Factor [19] | Total waste (kg) / Product (kg) | Mass of waste generated per mass of product | 0 |

| Process Mass Intensity (PMI) [19] | Total mass in process (kg) / Product mass (kg) | Total mass used per mass of product, includes solvents, reagents | 1 |

| EcoScale [19] | 100 - penalty points (yield, cost, safety, setup, T/t, workup) | Holistic score incorporating economic and safety factors | 100 |

These metrics enable researchers to move beyond qualitative assessments to data-driven evaluations of process efficiency and environmental impact [19]. The pharmaceutical industry has particularly embraced PMI as a comprehensive metric that accounts for all material inputs, including solvents, which typically constitute the largest mass component in drug manufacturing [13]. For context, pharmaceutical processes historically exhibited E-factors exceeding 100, meaning over 100 kilos of waste were produced per kilo of active pharmaceutical ingredient, though application of green chemistry principles has dramatically reduced these numbers [13].

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Atom Economy in Reaction Design

The implementation of atom economy requires careful consideration of reaction mechanisms and pathways [20]. Addition reactions, such as the Diels-Alder cycloaddition, represent ideal atom-economic transformations where all atoms from the starting materials are incorporated into the product without generating byproducts [14]. In contrast, substitution reactions typically generate stoichiometric byproducts, while elimination reactions produce even more waste [20]. The experimental protocol for maximizing atom economy involves:

- Reaction Type Selection: Prioritize rearrangement and addition reactions over substitutions or eliminations [20].

- Catalyst Design: Develop catalytic systems that enable direct transformations without requiring stoichiometric reagents [20].

- Route Scouting: Evaluate multiple synthetic pathways using atom economy calculations at the planning stage [19].

- Byproduct Minimization: Design reactions that generate only low-molecular-weight, innocuous byproducts such as water or nitrogen [20].

Professor Barry Trost's development of atom-economic catalytic reactions, for which he received the 1998 Presidential Green Chemistry Challenge Academic Award, demonstrated the practical application of this principle through novel transition metal-catalyzed processes that significantly reduced waste in complex molecule synthesis [20].

Green Synthesis of Nanoparticles

The green synthesis of nanoparticles exemplifies multiple principles working together [14]. Traditional nanoparticle synthesis often relies on toxic reducing agents and solvents, generating hazardous waste [14]. Green synthesis methodologies employ plant-derived biomolecules as both reducing and stabilizing agents [14]. A representative experimental protocol includes:

- Extract Preparation: Prepare aqueous extracts from plant materials (e.g., leaves, roots) using water as solvent [14].

- Metal Precursor Solution: Prepare an aqueous solution of metal ions (e.g., Ag⁺ for silver nanoparticles) [14].

- Reaction: Combine extract and metal solution under mild conditions (room temperature or slight heating) with stirring [14].

- Purification: Recover nanoparticles by centrifugation and wash with water [14].

- Characterization: Analyze size, shape, and stability using UV-Vis spectroscopy, TEM, and XRD [14].

This approach eliminates toxic reagents (Principle 3), uses water as a safe solvent (Principle 5), employs renewable feedstocks (Principle 7), and produces biodegradable nanoparticles (Principle 10) [14].

The Research Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Implementing green chemistry principles requires specific reagents, catalysts, and materials that enable sustainable chemical transformations. The following toolkit represents key solutions for green chemistry research, particularly in pharmaceutical development.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Green Chemistry

| Reagent/Material | Function | Green Advantage | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Renewable Feedstocks (e.g., biomass, CO₂) [14] | Starting materials for chemical synthesis | Redependence on petrochemicals, biodegradable | Bioplastics, bio-based pharmaceuticals [14] |

| Transition Metal Catalysts (e.g., Pd, Mn complexes) [21] | Enable catalytic cycles with high atom economy | Reduce stoichiometric waste, lower energy requirements | C-H activation, hydrogenation reactions [18] [21] |

| Safer Solvents (e.g., water, scCO₂, ionic liquids) [19] [14] | Reaction media with reduced hazard profile | Lower toxicity, reduced VOC emissions, recyclability | Nanoparticle synthesis, extraction processes [14] |

| Bio-Based Reducing Agents (e.g., plant extracts) [14] | Environmentally benign alternatives to toxic reductants | Biodegradable, non-toxic, from renewable sources | Green synthesis of metal nanoparticles [14] |

| Solid Supports & Heterogeneous Catalysts (e.g., zeolites, clays) [14] | Reusable catalytic materials | Recyclability, reduced waste, simplified separation | Friedel-Crafts alkylation, nitration reactions [14] |

The ACS GCI Pharmaceutical Roundtable has developed reagent guides that highlight preferred reagents for common transformations based on safety, efficiency, and environmental impact [18]. These guides help researchers select the greenest available options for reactions such as alcohol oxidations, amide reductions, and Suzuki couplings [18].

Impact on Pharmaceutical Research and Development

The pharmaceutical industry has emerged as a primary beneficiary and driver of green chemistry innovation, particularly due to the historically high waste generation in drug manufacturing [13] [10]. The implementation of green chemistry principles has transformed pharmaceutical development through:

Process Intensification: Dramatic reductions in Process Mass Intensity (PMI) through route redesign and waste minimization strategies [13]. Companies have achieved up to ten-fold reductions in waste per kilo of active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) through application of green chemistry principles [13].

Catalytic Methodologies: Development of atom-economic catalytic processes that replace stoichiometric reactions [20]. For example, transition metal-catalyzed C-H activation chemistry can significantly reduce synthetic steps, thereby reducing solvent, water, and energy use [18].

Solvent Selection Guides: Systematic replacement of hazardous solvents with safer alternatives based on comprehensive assessment of health, safety, and environmental criteria [18].

Continuous Flow Processing: Implementation of continuous manufacturing techniques that offer improved energy efficiency, reduced reactor volume, and enhanced safety compared to batch processes [18].

The pharmaceutical industry's embrace of green chemistry is exemplified by the ACS Green Chemistry Institute Pharmaceutical Roundtable, which brings together major drug manufacturers to collaboratively advance green chemistry practices [13] [18]. This partnership has yielded practical tools including reagent guides, solvent selection guides, and educational resources that drive continuous improvement across the sector [18].

Current Research Directions and Future Outlook

Twenty-five years after the publication of "Green Chemistry: Theory and Practice," the field continues to evolve with several emerging research frontiers [18] [21]. Current directions include:

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning: AI-driven approaches are being used to rapidly identify and design new sustainable catalysts and reaction pathways, minimizing waste and energy consumption [14]. The integration of AI in green chemistry represents the next frontier in process optimization and molecular design.

Advanced Materials for Sustainability: Development of biodegradable nanomaterials for biomedical applications, including silver nanoparticles with antimicrobial properties and zinc oxide platforms for eco-friendly photocatalysis [14].

Carbon Capture and Utilization: Transformation of CO₂ from waste gas to valuable chemical feedstocks, exemplified by recent advances in homogeneous catalytic systems for methanol production from carbon monoxide [21].

Mechanochemical Synthesis: Solvent-free reactions using mechanical energy, enabling functionalization of biopolymers like chitosan with higher efficiency than solution-based methods [21].

Multidimensional Metrics: Movement beyond single-metric assessments toward comprehensive sustainability evaluations that integrate green chemistry principles with life cycle assessment and environmental impact analysis [21].

The future of green chemistry will require overcoming scalability challenges in laboratory innovations and fostering interdisciplinary collaboration between chemists, toxicologists, engineers, and environmental scientists [18] [14]. As the field advances, the core principles established by Anastas and Warner continue to provide a robust framework for innovation that balances molecular design with environmental responsibility [13] [18].

Green chemistry represents a fundamental paradigm shift from conventional chemical practices, moving the focus from waste remediation and hazard control to the proactive design of products and processes that inherently minimize or eliminate the creation of hazardous substances [6] [7]. This transformative approach was formally established in 1998 when Paul Anastas and John Warner articulated the 12 Principles of Green Chemistry, providing a comprehensive framework for designing chemical syntheses that are environmentally benign, economically feasible, and socially responsible [6] [10] [14]. Unlike traditional pollution control strategies that employ "end-of-pipe" treatments, green chemistry advocates for pollution prevention at the molecular level through innovative scientific solutions [6] [7]. This philosophy has gained significant traction across global industries, particularly in pharmaceuticals, where it fosters the development of medicines while ensuring environmental responsibility throughout their lifecycle [22] [23].

The conceptual foundation of green chemistry was inspired by earlier environmental movements, most notably Rachel Carson's 1962 book Silent Spring, which highlighted the detrimental effects of chemicals on ecosystems [23] [10] [14]. The formal establishment of the field was catalyzed by the U.S. Pollution Prevention Act of 1990, which championed source reduction over waste management [6] [24] [7]. This legislative backdrop stimulated the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to launch research initiatives that would eventually coalesce into the formal discipline of green chemistry [6] [10]. The field has since evolved into a globally recognized framework, with the 12 principles serving as a universal guide for chemists seeking to align their work with sustainability goals [14].

Historical Milestones in Green Chemistry Development

The evolution of green chemistry from a conceptual framework to an established scientific discipline has been marked by several key milestones that reflect its growing global importance. The timeline below visualizes the pivotal events that have shaped the field from its inception to its current state as an interdisciplinary science driving sustainable innovation.

The institutionalization of green chemistry accelerated throughout the 1990s with the establishment of the Presidential Green Chemistry Challenge Awards in 1996, which recognized groundbreaking achievements in sustainable chemistry [6] [10]. The 1999 launch of the scientific journal Green Chemistry by the Royal Society of Chemistry provided a dedicated platform for disseminating research, while the 2005 Nobel Prize in Chemistry awarded to Chauvin, Grubbs, and Schrock explicitly recognized contributions that represented "a great step forward for green chemistry" [6]. In recent years, the field has increasingly integrated with advanced technologies, particularly artificial intelligence and machine learning, to optimize material synthesis and improve efficiency in chemical research and development [14].

The 12 Principles of Green Chemistry: A Detailed Framework

The 12 principles of green chemistry provide a systematic framework for designing chemical products and processes that reduce environmental and human health impacts. These principles have been widely adopted across academia and industry as guiding tenets for sustainable chemical design. The following table summarizes these core principles and their fundamental objectives.

Table 1: The 12 Principles of Green Chemistry and Their Applications

| Principle Number | Principle Name | Core Objective | Industrial Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Prevention | Prevent waste generation rather than treating or cleaning up after | Miniaturization of reactions using 1mg starting material [22] |

| 2 | Atom Economy | Maximize incorporation of starting materials into final product | Diels-Alder reactions with theoretical 100% atom economy [14] |

| 3 | Less Hazardous Synthesis | Design syntheses using/generating substances with minimal toxicity | Nickel catalysts replacing palladium in borylation [22] |

| 4 | Designing Safer Chemicals | Design effective products with minimal toxicity | Biodegradable antifouling compound replacement [14] |

| 5 | Safer Solvents & Auxiliaries | Reduce or eliminate auxiliary substances | Solvent-free methodologies in analytical chemistry [14] |

| 6 | Energy Efficiency | Run reactions at ambient temperature/pressure | Photocatalysis using visible light at low temperatures [22] |

| 7 | Renewable Feedstocks | Use raw materials from renewable sources | Bio-based feedstocks replacing fossil resources [6] [7] |

| 8 | Reduce Derivatives | Avoid temporary modifications requiring extra reagents | Late-stage functionalization avoiding protecting groups [22] |

| 9 | Catalysis | Prefer catalytic over stoichiometric reagents | Biocatalysts achieving in one step what takes many traditionally [22] |

| 10 | Design for Degradation | Design products to break down to innocuous substances | Chemicals designed to degrade after use [7] |

| 11 | Real-time Analysis | Monitor processes in real-time to prevent pollution | Process analytical technology (PAT) in manufacturing [7] |

| 12 | Inherently Safer Chemistry | Minimize potential for accidents including releases | Use of solids over gases or volatile liquids where possible [7] |

These principles function as an interconnected system rather than isolated guidelines, creating synergistic benefits when applied collectively [6] [14]. For instance, the use of catalysis (Principle 9) frequently enhances energy efficiency (Principle 6) and improves atom economy (Principle 2), while also reducing waste (Principle 1) [22]. This systems-thinking approach enables chemists to address multiple environmental objectives simultaneously while maintaining economic viability and product performance.

Quantitative Metrics for Evaluating Green Chemistry Performance

The implementation of green chemistry principles requires robust metrics to evaluate and compare the environmental performance of chemical processes. Several quantitative measures have been developed to provide objective assessment criteria for researchers and industrial practitioners.

Table 2: Key Quantitative Metrics for Green Chemistry Assessment

| Metric | Calculation Method | Application Context | Industry Benchmark |

|---|---|---|---|

| Process Mass Intensity (PMI) | Total mass of inputs (kg) / mass of product (kg) | Pharmaceutical API synthesis | Reduction from 86kg to 17kg waste per kg product in pregabalin synthesis [25] |

| Atom Economy | (Molecular weight of product / Molecular weight of reactants) × 100% | Reaction design evaluation | Diels-Alder reactions achieving 100% theoretical atom economy [14] |

| E-Factor | Total waste (kg) / product (kg) | Process environmental impact | Key metric for waste prevention in antiparasitic drug synthesis [24] |

| CO₂ Reduction | CO₂ emissions before vs. after process changes | Catalyst replacement evaluation | >75% reduction with nickel vs. palladium catalysts [22] |

| Energy Efficiency | Energy consumption per kg product | Manufacturing process assessment | 82% reduction in pregabalin synthesis through green chemistry [25] |

These metrics enable objective evaluation of green chemistry implementations and facilitate continuous improvement in environmental performance. The pharmaceutical industry has particularly embraced Process Mass Intensity (PMI) as a key indicator, as it accounts for all input materials including solvents, catalysts, and reagents that typically become waste rather than being incorporated into the final Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) [22]. Advances in predictive analytics now allow researchers to forecast the PMI of all possible synthetic routes without extensive experimentation, accelerating the identification of optimal green pathways during process development [22].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies in Green Chemistry

Green Synthesis of Tafenoquine Succinate

The application of green chemistry principles to the synthesis of tafenoquine succinate, an antiparasitic drug, demonstrates a comprehensive implementation of waste prevention strategies [24]. The protocol employs a two-step one-pot synthesis that significantly reduces solvent use and eliminates toxic reagents present in previous synthetic routes.

Key Experimental Protocol:

- Reaction Setup: Conduct N-(4-methoxyphenyl)-3-oxobutanamide formation in a one-pot system to minimize intermediate isolation and purification steps

- Solvent Selection: Utilize safer solvent alternatives with reduced environmental and health impacts

- Catalyst Optimization: Implement catalytic systems that operate at lower loadings and enable higher atom economy

- Process Intensification: Design sequential reactions without workup procedures between steps to minimize material losses

This methodology exemplifies Principle 1 (Prevention) by fundamentally redesigning the synthetic pathway to avoid waste generation at the source, rather than implementing end-of-pipe treatment approaches [24].

Late-Stage Functionalization for PROTAC Synthesis

Late-stage functionalization represents a transformative approach in pharmaceutical chemistry that enables direct modification of complex molecules, dramatically improving synthetic efficiency [22]. This technique allows medicinal chemists to generate molecular diversity more quickly and sustainably by reducing resource-intensive reaction steps.

Experimental Workflow:

- Substrate Preparation: Begin with advanced intermediate or drug-like molecule as starting material

- Functionalization Optimization: Screen reaction conditions using high-throughput experimentation with minimal material (as little as 1mg)

- Selectivity Control: Employ directing groups or catalyst systems to achieve site-selective modifications

- Product Diversification: Generate multiple analogs from a common precursor through selective addition of different functional groups

This approach has been successfully applied to create over 50 different drug-like molecules and enables the selective conversion of active pharmaceutical ingredients into PROteolysis TArgeting Chimeras (PROTACs) in a single step, dramatically improving synthetic efficiency for these complex therapeutic modalities [22].

Miniaturized High-Throughput Experimentation

Miniaturization of chemical reactions represents a powerful methodology for sustainable drug discovery, allowing researchers to explore novel chemistry with minimal material consumption [22].

Detailed Methodology:

- Reaction Scale: Utilize as little as 1mg of starting material per reaction vessel

- Experimental Design: Employ statistical design of experiments to maximize information gain from limited resources

- Automated Handling: Implement liquid handling robotics for precise manipulation of small volumes

- Parallel Processing: Conduct thousands of reactions simultaneously to rapidly explore chemical space

- Analytical Integration: Couple with high-throughput analytics for rapid reaction evaluation

This approach, developed in collaboration with Stockholm University, enables several thousand times more reactions to be performed compared to standard techniques with the same amount of material, representing a paradigm shift in how chemical optimization is conducted during drug discovery [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

The implementation of green chemistry principles requires specialized reagents and catalysts designed to minimize environmental impact while maintaining or enhancing reaction efficiency. The following table details key reagents that enable greener synthetic approaches in pharmaceutical research and development.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Green Chemistry Applications

| Reagent/Catalyst | Function | Green Chemistry Advantage | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nickel Catalysts | Catalyze cross-coupling reactions (e.g., borylation, Suzuki) | Replaces scarce palladium; >75% reduction in CO₂, freshwater use, and waste [22] | Borylation reactions in API synthesis [22] |

| Biocatalysts | Protein-based catalysts for specific transformations | Single-step processes replacing multi-step syntheses; biodegradable [22] | Streamlined routes to complex drug molecules [22] |

| Photocatalysts | Utilize light energy to drive chemical transformations | Enables milder reaction conditions; reduces energy requirements [22] | Visible-light-mediated synthesis of building blocks [22] |

| Electrocatalysts | Use electricity to drive selective transformations | Replaces chemical oxidants/reductants; unique reaction pathways [22] | Selective arene alkenylations without directing groups [22] |

| Clay/Zeolite Catalysts | Solid acid catalysts for various transformations | Replaces corrosive liquid acids; recyclable [14] | Nitration of aromatic compounds with near-zero waste [14] |

The strategic selection of catalysts represents one of the most powerful approaches for implementing green chemistry principles in pharmaceutical research. Biocatalysts stand apart from conventional catalysts by often achieving in a single synthetic step what traditionally requires multiple steps, while nickel-based catalysts offer significant environmental advantages over precious metal alternatives through their greater abundance and reduced toxicity [22]. Advances in computational enzyme design combined with machine learning are expanding the range of biocatalysts available for a wider spectrum of chemical reactions, transforming sustainable synthesis in drug discovery and beyond [22].

Green Chemistry in Pharmaceutical Applications: Case Studies

Pfizer's Pregabalin Synthesis

Pfizer developed an innovative green chemistry process for manufacturing pregabalin, the active ingredient in Lyrica, that demonstrates the significant environmental and economic benefits achievable through principle-driven design [25]. The traditional synthesis utilized organic solvents and generated substantial waste, with a process mass intensity of 86kg of waste per kg of API produced.

The green chemistry approach implemented the following key improvements:

- Solvent System Redesign: Replaced organic solvents with aqueous alternatives where possible

- Process Optimization: Reduced the number of synthetic steps and eliminated unnecessary derivatization

- Energy Integration: Implemented heat recovery and energy-efficient separation techniques

The results were transformative: waste generation dropped from 86kg to 17kg per kg of product, representing an 80% reduction in waste, while energy use decreased by 82% compared to the conventional process [25]. This case exemplifies the "triple bottom line" benefits of green chemistry, simultaneously improving environmental performance, economic efficiency, and process safety.

AstraZeneca's Catalyst Innovation

AstraZeneca has pioneered the development and implementation of sustainable catalysts across its research, development, and manufacturing operations [22]. The company's systematic approach to catalyst replacement demonstrates how Principle 9 (Catalysis) can be implemented at scale in pharmaceutical development.

Key achievements include:

- Palladium Replacement: Development of nickel-based catalysts for borylation and Suzuki reactions, reducing CO₂ emissions, freshwater use, and waste generation by more than 75%

- Photocatalysis Implementation: Creation of photocatalyzed reactions that removed several stages from the manufacturing process for a late-stage cancer medicine

- Electrocatalysis Development: Application of electrocatalysis to selectively attach carbon units, enabling sustainable diversification of drug-like compounds

These catalyst innovations enable access to unique reaction pathways under milder conditions while simultaneously replacing hazardous chemical reagents [22]. The implementation of visible-light-mediated catalysis has been particularly valuable, enabling the synthesis of crucial building blocks for drug design under low temperatures with safer reagents [22].

The future of green chemistry will be increasingly shaped by emerging technologies and integrative frameworks that accelerate the design of sustainable chemical products and processes. Artificial intelligence and machine learning are revolutionizing how chemists approach reaction optimization and molecular design, with algorithms that can predict reaction outcomes, identify patterns in large datasets, and suggest synthetic routes with improved environmental profiles [22] [14]. The integration of green chemistry with circular chemistry and safe and sustainable-by-design (SSbD) frameworks represents another important frontier, promoting a holistic approach that considers the entire lifecycle of chemical products [26].

The ongoing development of green chemistry educational curricula and the expansion of international networks will be crucial for disseminating best practices and fostering innovation [6] [10]. As the field continues to evolve, the 12 principles will remain a foundational framework guiding chemical design toward sustainability goals. Future research will likely focus on optimizing green synthetic techniques, addressing scalability challenges in industrial applications, and fostering interdisciplinary collaboration to accelerate the transition toward a more sustainable chemical industry [14]. Through continued innovation and principle-driven design, green chemistry will play an increasingly vital role in addressing global challenges such as climate change, resource depletion, and environmental pollution while continuing to deliver the chemical products essential to modern society.

The development of green chemistry as a recognized scientific field has been catalyzed by key institutional initiatives that provided structure, recognition, and collaborative frameworks for researchers. The Presidential Green Chemistry Challenge Awards and the establishment of global green chemistry networks represent two pivotal pillars in the formalization and advancement of the discipline. These institutions have systematically transformed green chemistry from a theoretical concept into a practical framework guiding industrial and academic research worldwide.

This institutional foundation emerged as a direct response to the limitations of end-of-pipe pollution control strategies and reflected a broader paradigm shift toward pollution prevention. The Pollution Prevention Act of 1990 marked a critical turning point in U.S. environmental policy, establishing a national mandate to eliminate pollution through improved design rather than through treatment and disposal [6]. This legislative foundation created the necessary conditions for the scientific community to develop and embrace green chemistry as a viable research pathway.

Historical Development and Institutionalization

The Formative Years: Establishing a New Framework

The institutionalization of green chemistry began in earnest during the early 1990s, building upon decades of growing environmental awareness. The 1962 publication of Rachel Carson's "Silent Spring" first mainstreamed concerns about chemical pollution, while the 1970 establishment of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) created a regulatory body devoted to environmental protection [27]. The 1984 Bhopal disaster further highlighted the devastating potential of chemical accidents, prompting stricter regulations and increased search for safer alternatives [28].

In 1991, the EPA's Office of Pollution Prevention and Toxics launched a research grant program specifically encouraging the redesign of chemical products and processes to reduce environmental and health impacts [6]. This program represented a significant departure from traditional command-and-control approaches, instead focusing on prevention through molecular design. The Twelve Principles of Green Chemistry, formalized by Paul Anastas and John Warner in 1998, provided the nascent field with a comprehensive set of design guidelines that would direct research for decades to follow [6] [10].

The Presidential Green Chemistry Challenge Awards

Established in 1996, the Presidential Green Chemistry Challenge Awards created a prestigious platform for recognizing and promoting innovations that incorporated green chemistry principles into commercial practice [29] [27]. Administered initially by the EPA and now by the American Chemical Society, these awards have become a cornerstone of green chemistry education and a powerful driver of innovation [6] [30].

The awards program was strategically designed to highlight technologies that demonstrated both environmental and economic benefits, showcasing how green chemistry could align business interests with environmental protection. By celebrating success stories across industrial and academic sectors, the awards program has effectively created a repository of proven case studies that continue to guide researchers and product developers [30].

Global Network Development

The mid-to-late 1990s witnessed the rapid expansion of institutional support for green chemistry through the establishment of dedicated organizations and networks. The Green Chemistry Institute (GCI), founded in 1997 as an independent nonprofit, became a pivotal organization for advancing green chemistry principles through knowledge sharing and collaboration [27]. The GCI's incorporation into the American Chemical Society in 2001 provided institutional stability and significantly expanded its reach and impact [27] [10].

International networks proliferated during this period, including the Mediterranean Countries Network on Green Chemistry (MEGREC), the Green and Sustainable Chemistry Network in Japan, and the Centre of Green Chemistry at Monash University in Australia [27]. These organizations facilitated cross-border collaboration and helped establish green chemistry as a global scientific movement. The launch of the Royal Society of Chemistry's journal Green Chemistry in 1999 provided an essential academic venue for disseminating research findings [6].

Quantitative Impact of the Awards Program

The Presidential Green Chemistry Challenge Awards have generated substantial environmental benefits through the technologies they have recognized. The cumulative impact of award-winning technologies demonstrates the significant potential of green chemistry to address resource conservation and pollution prevention at scale.

Table 1: Cumulative Environmental Benefits of Green Chemistry Challenge Award Winners (1996-2024)

| Environmental Metric | Cumulative Impact | Equivalent Measure |

|---|---|---|

| Hazardous chemicals eliminated | 830 million pounds | Equivalent to removing thousands of tanker trucks of hazardous materials from production and waste streams |

| Water saved | 21 billion gallons | Annual water use for approximately 200,000 households |

| Carbon dioxide equivalents prevented | 7.8 billion pounds | Annual emissions from approximately 750,000 passenger vehicles |

Source: [30]

The awards program has recognized innovations across multiple sectors, with particularly strong representation in pharmaceuticals, agriculture, and renewable chemicals. The distribution of awards by industry sector reflects both the environmental impact areas and the commercial applicability of green chemistry innovations.

Table 2: Green Chemistry Challenge Awards by Industry Sector (Select Recent Years)

| Industry Sector | Number of Awards (2020-2024) | Representative Technologies |

|---|---|---|

| Pharmaceuticals | 5 | Continuous manufacturing of biologics, improved drug synthesis, multifunctional catalysts |

| Agriculture & Agrochemicals | 5 | Biopesticides, seed treatments, enhanced fertilizers |

| Bulk & Specialty Chemicals | 5 | Bio-based chemicals, renewable lubricants, hydrogen technology |

| Plastics & Polymers | 2 | Biodegradable polymers, CO2-based thermoplastics |

| Energy Production & Storage | 2 | Flow batteries, renewable fuels |

| Other Sectors | 4 | Safer disinfectants, formaldehyde-free binders, metal recycling |

Source: [29]

Methodological Frameworks and Experimental Approaches

The Twelve Principles as a Design Framework

The Twelve Principles of Green Chemistry provide a comprehensive methodological framework for designing chemical products and processes that reduce or eliminate hazardous substances [6] [10]. These principles serve as experimental guidelines that researchers can systematically apply throughout the development process:

- Prevention: Preventing waste is more efficient than treating or cleaning up waste after it is formed

- Atom Economy: Synthetic methods should maximize incorporation of all materials used in the process into the final product

- Less Hazardous Chemical Syntheses: Wherever practicable, synthetic methodologies should use and generate substances with little or no toxicity

- Designing Safer Chemicals: Chemical products should be designed to achieve desired function while minimizing toxicity

- Safer Solvents and Auxiliaries: Auxiliary substances should be avoided where possible and be innocuous when used

- Design for Energy Efficiency: Energy requirements should be recognized for environmental and economic impacts and should be minimized

- Use of Renewable Feedstocks: Raw material feedstocks should be renewable rather than depleting

- Reduce Derivatives: Unnecessary derivatization should be minimized or avoided to reduce waste

- Catalysis: Catalytic reagents are superior to stoichiometric reagents

- Design for Degradation: Chemical products should be designed so they break down into innocuous degradation products

- Real-time Analysis for Pollution Prevention: Analytical methodologies need further development to allow for real-time, in-process monitoring and control

- Inherently Safer Chemistry for Accident Prevention: Substances used in a chemical process should be chosen to minimize potential for chemical accidents

Representative Experimental Protocols

Continuous Manufacturing of Biologics (2024 Award Winner)

The 2024 award-winning technology from Merck & Co. for continuous manufacturing of KEYTRUDA exemplifies the application of multiple green chemistry principles through its experimental approach [29].

Protocol Overview:

- System Configuration: Implement single-use bioreactor systems with integrated purification modules

- Process Intensification: Develop continuous chromatography with simulated moving bed technology

- Monitoring: Incorporate real-time analytics with multi-attribute monitoring (MAM) for quality control

- Integration: Connect upstream and downstream processing with minimal hold steps

Key Experimental Parameters:

- Residence time distribution optimized to 2-4 hours (vs. 2-3 weeks in batch)

- Product titer maintained at 3-5 g/L through controlled nutrient feeding

- Purification yield increased to >85% through continuous countercurrent chromatography

This methodology demonstrates Principle 6 (Energy Efficiency) through reduced facility footprint, Principle 3 (Less Hazardous Syntheses) by eliminating intermediate purification solvents, and Principle 11 (Real-time Analysis) through integrated process analytical technology.

Bio-based Ethyl Acetate Production (2024 Small Business Award)

Viridis Chemical Company's dehydrogenation of bio-ethanol to ethyl acetate represents a green synthetic pathway applying multiple principles [29].

Experimental Procedure:

- Feedstock Preparation: Utilize bio-ethanol from fermentation (96% purity, 4% water)

- Catalyst System: Employ copper-based heterogeneous catalyst with zinc oxide promoter

- Reactor Conditions: Operate at 225-250°C with pressure maintained at 10-15 bar

- Product Separation: Implement distillation with heat integration for energy recovery

Analytical Verification:

- GC-MS analysis confirming ethyl acetate purity >99.5%

- Life cycle assessment showing 60-70% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions vs. petroleum route

- Atom economy calculation demonstrating 85% efficiency vs. 65% for conventional synthesis

This protocol exemplifies Principle 7 (Renewable Feedstocks) through bio-ethanol utilization and Principle 9 (Catalysis) with the heterogeneous catalyst system.

Research Reagent Solutions for Green Chemistry

The implementation of green chemistry principles requires specific reagents and materials that enable safer, more efficient syntheses. The following table details essential research reagents commonly employed in green chemistry applications.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Green Chemistry Applications

| Reagent/Material | Function | Green Chemistry Principle Addressed |

|---|---|---|

| Immobilized Enzymes | Biocatalysts for selective transformations under mild conditions | Principle 3 (Less Hazardous Syntheses), Principle 9 (Catalysis) |

| Heterogeneous Catalysts | Solid-phase catalysts enabling easy separation and reuse | Principle 9 (Catalysis) |

| Supercritical CO₂ | Non-toxic alternative to organic solvents for extraction and reactions | Principle 5 (Safer Solvents) |

| Ionic Liquids | Tunable, non-volatile solvents for various applications | Principle 5 (Safer Solvents) |

| Bio-based Feedstocks | Renewable starting materials from biomass | Principle 7 (Renewable Feedstocks) |

| Water as Reaction Medium | Replacement for organic solvents in aqueous-compatible reactions | Principle 5 (Safer Solvents) |

| Polymer-supported Reagents | Facilitating reagent recovery and product purification | Principle 1 (Waste Prevention) |

Source: Based on technologies described in [29] [28] [10]

Institutional Networks and Collaborative Frameworks

The growth of green chemistry has been accelerated by dedicated institutional networks that facilitate knowledge transfer, collaboration, and education. These networks operate across academic, industrial, and governmental sectors to advance green chemistry adoption.

The ACS Green Chemistry Institute

The ACS GCI has established industry-specific Roundtables that serve as collaborative platforms for advancing green chemistry in various sectors. The Pharmaceutical Roundtable, established in 2005, was followed by additional roundtables for chemical manufacturers, formulators, and other specialized areas [27]. These roundtables develop common research agendas, share best practices, and create tools to facilitate green chemistry implementation.