E-Factor Reduction Strategies: A Practical Guide to Waste Prevention in Pharmaceutical Development

This comprehensive review addresses the critical challenge of waste reduction in pharmaceutical development through E-factor optimization.

E-Factor Reduction Strategies: A Practical Guide to Waste Prevention in Pharmaceutical Development

Abstract

This comprehensive review addresses the critical challenge of waste reduction in pharmaceutical development through E-factor optimization. Targeting researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we explore foundational principles of green chemistry metrics, practical methodologies for waste minimization, troubleshooting common inefficiencies, and validation through case studies. The article demonstrates how strategic E-factor reduction not only addresses environmental concerns but also drives significant cost savings and process efficiency gains, positioning sustainable chemistry as a competitive advantage in drug development.

Understanding E-Factor: The Cornerstone of Green Chemistry Metrics in Pharma

Troubleshooting Guide: E-Factor Calculation and Reduction

Issue 1: Inconsistent E-Factor Values Across Batches

Problem: Calculating significantly different E-Factor values for the same process, making performance tracking unreliable.

- Solution: Standardize your waste accounting method. The E-Factor formula is

E-Factor = Total mass of waste / Total mass of product[1] [2]. Ensure all teams consistently include or exclude the same waste categories, particularly water and recyclable solvents [1]. Implement a standardized waste tracking protocol across all research activities.

Issue 2: High Solvent Waste in Discovery Chemistry

Problem: Discovery-phase research generates excessive solvent waste, dramatically increasing E-Factor.

- Solution: Adopt acoustic dispensing technology to reduce solvent volumes by miniaturezing reactions [3]. Implement solvent recovery systems and select solvents that are easily recyclable. One ICM pilot plant achieved a 53% E-Factor reduction (from 1.627 to 0.770) partly through improved solvent recovery yields from 95.8% to 98.3% [4].

Issue 3: Plastic Waste from Laboratory Consumables

Problem: Single-use plastics (pipette tips, assay plates) constitute major waste streams and cannot be recycled due to contamination [3].

- Solution: Transition to higher plate formats (384- or 1536-well) to reduce plastic consumption per data point [3]. Implement vendor take-back programs for consumables and prioritize suppliers offering recycling initiatives, such as those achieving "zero waste" certification for their manufacturing sites [5].

Issue 4: Process Optimization Ignoring Environmental Impact

Problem: Traditional process optimization focuses solely on yield, potentially creating high, unrecognized E-Factors.

- Solution: Integrate Design of Experiment (DoE) methodologies to optimize for sustainability endpoints alongside yield [3]. DoE allows researchers to reduce waste and eliminate harmful reagents from the initial assay design stage.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What constitutes "waste" in E-Factor calculations? A: E-Factor accounts for all non-product output, including byproducts, leftover reactants, solvent losses, and spent catalysts [1]. Water is typically excluded unless severely contaminated [1]. The definition should be consistently applied across all calculations for comparative purposes.

Q2: What are the benchmark E-Factor values for different industries? A: E-Factor varies significantly by industry sector, with higher value products typically having higher acceptable E-Factors [6] [1]:

Table: Industry E-Factor Benchmarks

| Industry Sector | Annual Production (tons) | Typical E-Factor Range |

|---|---|---|

| Oil Refining | 10⁶ – 10⁸ | < 0.1 |

| Bulk Chemicals | 10⁴ – 10⁶ | < 1 – 5 |

| Fine Chemicals | 10² – 10⁴ | 5 – 50 |

| Pharmaceutical Industry | 10 – 10³ | 25 – >100 |

Q3: How does E-Factor differ from Process Mass Intensity (PMI)? A: E-Factor and PMI are related but distinct metrics. PMI is the total mass used in a process per mass of product, while E-Factor is specifically waste per product mass. Mathematically: E-Factor = PMI - 1 [4]. For multi-step processes, E-Factors are additive across steps, while PMI is not [4].

Q4: What are the limitations of E-Factor as a standalone metric? A: E-Factor is mass-based and doesn't account for the environmental impact or toxicity of waste [1] [2]. A process with a low E-Factor generating highly toxic waste may be less desirable than one with a slightly higher E-Factor generating benign waste. For comprehensive assessment, E-Factor should be complemented with other metrics like Environmental Quotient (EQ) or life cycle assessment [1].

Experimental Protocols for E-Factor Reduction

Protocol 1: Integrated Continuous Manufacturing (ICM) Implementation

Objective: Reduce E-Factor through seamless continuous processing instead of batch operations.

- Methodology:

- Design an end-to-end integrated system with continuous flow reactors instead of batch reactors

- Implement Process Analytical Technologies (PAT) for real-time monitoring and control

- Establish automated solvent recovery units within the process flow

- Measure waste streams (including solvents, byproducts, and failed batches) separately and calculate E-Factor for comparison with batch processes

- Expected Outcome: The ICM pilot plant for pharmaceuticals achieved a 53% E-Factor reduction from 1.627 (batch) to 0.770 (ICM), and a further 30% reduction (to 0.210) with integrated solvent recovery [4].

Protocol 2: Design of Experiment (DoE) for Sustainable Process Optimization

Objective: Systematically reduce waste generation while maintaining or improving yield.

- Methodology:

- Identify key process variables (temperature, catalyst loading, stoichiometry, solvent volume)

- Design experimental matrix using statistical software

- Run experiments with E-Factor as a key response variable alongside yield and purity

- Develop predictive models to identify optimum conditions that minimize waste

- Validate models with confirmation experiments

- Application: DoE serves as "a way of thinking about running processes with a focus on sustainability as the endpoint" [3], enabling waste reduction at the design stage rather than post-optimization.

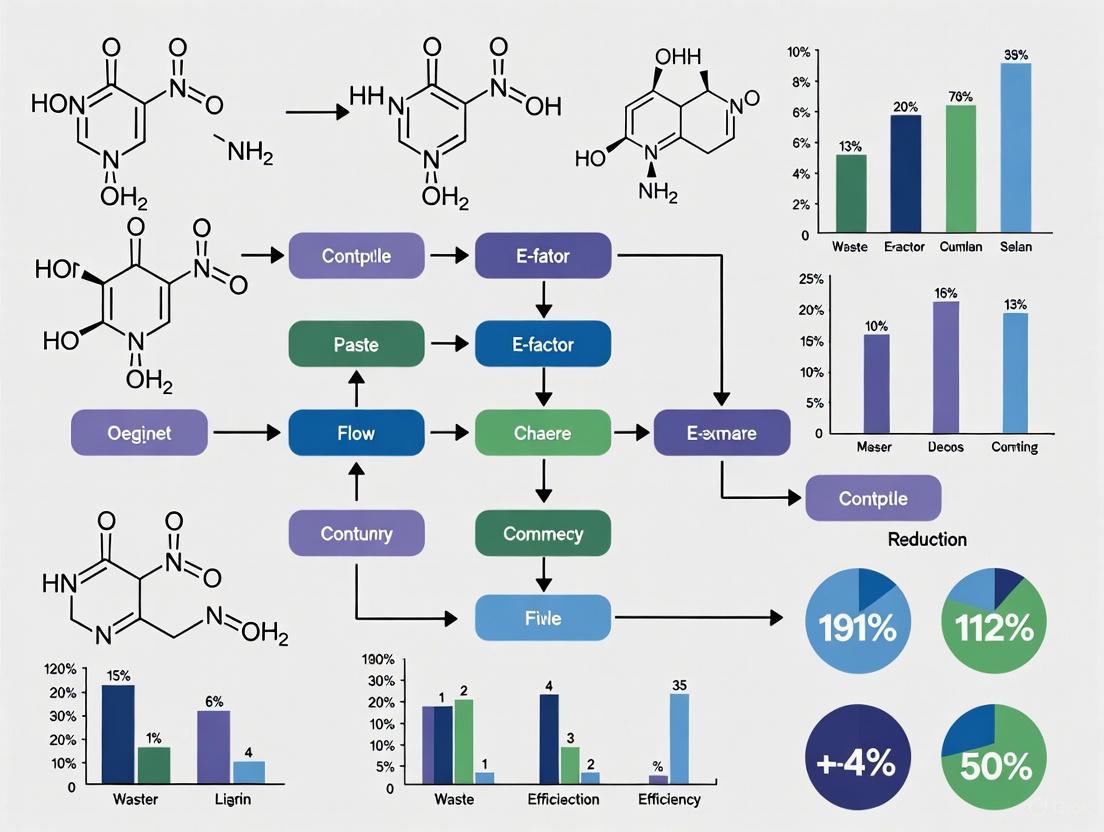

Workflow Visualization: E-Factor Reduction Pathways

E-Factor Reduction Pathway

Research Reagent Solutions for Waste Reduction

Table: Essential Tools for E-Factor Reduction

| Research Solution | Function in Waste Reduction | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Acoustic Dispensing | Miniaturizes reactions, reducing solvent volumes up to 90% [3] | Discovery chemistry, high-throughput screening |

| Design of Experiment (DoE) Software | Optimizes processes for sustainability endpoints [3] | Process development, assay design |

| Higher Density Plate Formats (384-/1536-well) | Reduces plastic consumption per data point [3] | Screening assays, diagnostic tests |

| Continuous Flow Reactors | Eliminates batch-to-batch variation and cleaning waste [4] | API synthesis, multi-step reactions |

| Process Analytical Technologies (PAT) | Enables real-time monitoring, reducing failed batches [4] | Manufacturing process control |

| Solvent Recovery Systems | Reclaims and recycles solvents, reducing fresh solvent use [4] | All solvent-intensive processes |

Definition and Core Concept

What is the E-Factor?

The E-Factor, or Environmental Factor, is a fundamental green chemistry metric used to quantify the waste efficiency of a chemical process. It is defined as the ratio of the total mass of waste produced to the mass of the desired product [1] [7] [2].

The formula for calculating the E-Factor is:

E-factor = Total mass of waste (kg) / Mass of product (kg)

The ideal E-Factor is 0, representing a process that generates no waste. A higher E-Factor indicates a larger waste footprint and a less environmentally friendly process [7]. It's important to note that water is generally excluded from the waste calculation to allow for more meaningful comparisons between processes, unless it is severely contaminated [1] [7].

What is Process Mass Intensity (PMI)?

Process Mass Intensity (PMI) is another key green metric closely related to the E-Factor. It is defined as the total mass of materials used in a process per mass of product [6]. The relationship between E-Factor and PMI is direct and can be expressed as [7] [6]:

PMI = E-Factor + 1

This means PMI accounts for everything that enters a process, including the desired product itself. The ideal PMI is 1 [7].

Industry E-Factor Benchmarks

The E-Factor varies significantly across different sectors of the chemical industry, largely dependent on production volume and process complexity. The table below summarizes typical E-Factors [7] [2] [6]:

| Industry Sector | Annual Production (Tonnes) | Typical E-Factor (kg waste/kg product) |

|---|---|---|

| Oil Refining | 106 – 108 | < 0.1 |

| Bulk Chemicals | 104 – 106 | < 1 - 5 |

| Fine Chemicals | 102 – 104 | 5 - 50 |

| Pharmaceuticals | 10 – 103 | 25 - > 100 |

Experimental Protocol: Calculating E-Factor and PMI

This protocol provides a standardized method for determining the E-Factor and PMI of a chemical process, enabling consistent tracking and comparison of material efficiency.

1. Objective To quantitatively assess the material efficiency and environmental impact of a chemical process by calculating its E-Factor and Process Mass Intensity (PMI).

2. Materials and Data Requirements

- Mass data for all input materials: reactants, solvents, reagents, catalysts, and process aids.

- Mass of the isolated, final desired product.

- Data collection should encompass the entire process, from initial reaction to final work-up and purification.

3. Step-by-Step Methodology

Step 1: Define Process Boundaries Clearly identify the start and end points of the process you are evaluating (e.g., from weighed reactants to isolated, dried product).

Step 2: Measure Total Input Mass (Σ Inputs) Accurately record the mass of every material introduced within the process boundaries. This includes all reactants, solvents, catalysts, acids, bases, and purification agents (e.g., filtration aids, chromatography materials).

Step 3: Measure Product Mass Weigh the final, purified product after it has been isolated and dried.

Step 4: Calculate Total Waste Mass The waste mass is not typically measured directly but is derived from the principle of mass conservation:

Total Waste Mass = Total Mass of Inputs - Mass of ProductStep 5: Calculate E-Factor and PMI

- E-Factor =

Total Waste Mass / Mass of Product - PMI =

Total Mass of Inputs / Mass of Product - Validate your result by checking that

PMI = E-Factor + 1.

- E-Factor =

4. Data Interpretation and Reporting Report both the E-Factor and PMI values. A lower value for both metrics indicates higher material efficiency and a lower environmental footprint in terms of waste generation. These values should be tracked over time to measure the effectiveness of process optimization efforts.

E-Factor and PMI Calculation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for calculating and interpreting these key metrics.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Implementing E-Factor reduction strategies often involves selecting the right tools and reagents. The following table details essential items for conducting material efficiency assessments and process optimization.

| Item / Solution | Function in Waste Reduction |

|---|---|

| Catalytic Reagents | Replaces stoichiometric reagents, thereby reducing byproduct formation and improving atom economy, a key driver for lowering E-Factor [7]. |

| Acoustic Dispensing | Enables precise, miniaturized handling of liquids and solvents, drastically reducing the volumes required for assays and screenings, which cuts solvent waste [3]. |

| Benign Alternative Solvents | Switching to safer, biodegradable, or recyclable solvents (e.g., water, ethanol) reduces the environmental impact and hazard quotient of waste streams. |

| Design of Experiment (DoE) | A statistical framework for optimizing processes with fewer experimental runs, leading to reduced consumption of reagents, solvents, and materials during R&D [3]. |

| Process Mass Intensity (PMI) Tracking | A software or spreadsheet-based system for logging all material inputs, which is the foundational data required for calculating E-Factor and identifying waste hotspots. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why is the E-Factor considered a more accurate measure of environmental impact than chemical yield alone? Chemical yield only measures the efficiency of converting reactants to the desired product. In contrast, the E-Factor provides a holistic view by accounting for all waste generated, including solvents, reagents, and process aids, which often constitute the majority of the waste mass in fine chemical and pharmaceutical synthesis [7] [6]. A high-yielding process can still have a disastrously high E-Factor if it uses large amounts of non-recyclable solvents or stoichiometric reagents.

2. What is the main limitation of the E-Factor, and how can it be addressed? The primary limitation of the E-Factor is that it is a mass-based metric and does not account for the toxicity, hazardousness, or environmental impact of the waste itself. One kilogram of sodium chloride is not equivalent to one kilogram of a heavy metal salt [7] [6]. This limitation can be addressed by using the Environmental Quotient (EQ), which is calculated by multiplying the E-Factor by an arbitrarily assigned "unfriendliness quotient" (Q) that reflects the hazardous nature of the waste [7].

3. How do E-Factor and Atom Economy complement each other? These are two distinct but complementary metrics. Atom Economy is a theoretical calculation based on the stoichiometry of a reaction; it predicts the inherent waste from a reaction pathway, helping chemists select greener routes during initial design [2]. The E-Factor is an empirical measurement of the actual waste produced in the lab or plant, taking into account yield, solvents, and all other process materials. A reaction with high atom economy can have a poor E-Factor if it requires excess reagents, large solvent volumes, or complex purifications [7].

4. Our pharmaceutical development process has an E-Factor of 50. Is this acceptable? While E-Factors in the pharmaceutical industry are notoriously high (often 25 to over 100) due to multi-step syntheses and stringent purity requirements, an E-Factor of 50 indicates significant room for improvement [7] [6]. You should benchmark this value against other processes within your organization and the industry. Implementing strategies like solvent recovery, switching to catalytic reactions, and optimizing work-up procedures can drive this number down, reducing both environmental impact and production costs.

5. What are the most effective initial strategies for reducing E-Factor in a research setting?

- Solvent Selection and Recovery: Focus on reducing and recycling solvents, as they often constitute the largest portion of waste mass [8].

- Catalysis: Replace stoichiometric reagents with catalytic alternatives to minimize byproduct formation [7].

- Process Integration: Design multi-step syntheses to avoid intermediate isolation and purification, which generate significant solvent and purification waste.

- Metrics-Guided Design: Use E-Factor and PMI calculations from the earliest stages of R&D to make informed decisions that prioritize waste minimization [3].

The Environmental Factor (E-factor) is a key metric in green chemistry, defined as the ratio of the total mass of waste produced to the mass of the desired product [1]. It provides a straightforward measure of the environmental efficiency of a chemical process, with a lower E-factor indicating a less wasteful process.

Industry benchmarks for E-factor vary dramatically between sectors, primarily due to differences in product complexity, purification requirements, and the number of synthetic steps [2]. The table below summarizes typical E-factors across different chemical industries.

Table 1: E-Factor Benchmarks Across Chemical Industries

| Industry Sector | Annual Production (Tonnes) | Typical E-Factor | Waste Produced (Tonnes) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bulk Chemicals | 10⁶ – 10⁸ | < 1 - 5 | 10⁵ – 10⁷ |

| Fine Chemicals | 10² – 10⁴ | 5 - 50 | Varies |

| Pharmaceuticals | 10¹ – 10³ | 25 -> 100 | Varies |

Why is the Pharmaceutical Industry's E-Factor So High?

Several factors contribute to the high E-factors in pharmaceutical manufacturing [2] [9]:

- Multi-step Synthesis: Complex Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) often require lengthy synthetic pathways, with waste accumulating at each step.

- Stoichiometric Reagents: An over-reliance on stoichiometric rather than catalytic reagents generates significant by-products.

- High Purity Standards: Extensive purification processes, such as chromatography, generate substantial waste streams.

- Solvent-Intensive Processes: Solvents can account for a large percentage of the total waste mass, often contributing to 80-90% of the total E-factor [10].

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental difference between E-Factor and Atom Economy?

Answer: While both are green chemistry metrics, they measure different things. Atom Economy is a theoretical calculation based on the molecular weights in a reaction's stoichiometric equation. It assesses the inherent efficiency of a reaction before it is run [2]. In contrast, the E-Factor is an experimental metric measured after a process is complete. It accounts for all real-world waste, including excess reagents, solvents, and materials from work-up and purification, providing a practical picture of environmental impact [1].

Troubleshooting Guide: If your process has a high Atom Economy but also a high E-Factor, your primary issue is likely not the core reaction but rather auxiliary materials. Focus on solvent recovery and recycling or optimizing purification methods.

FAQ 2: Our API synthesis has an E-Factor over 100. Where should we start to reduce it?

Answer: A high E-factor indicates significant waste generation. The first step is a mass balance analysis to identify the largest waste streams [10]. Typically, aqueous and solvent wastes are the biggest contributors.

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Analyze Waste Composition: Quantify the mass of all input materials (reactants, solvents, catalysts) and output waste streams for each synthesis step.

- Target Solvent Waste: Since solvents often constitute the majority of waste, prioritize their reduction. Investigate solvent substitution (replacing hazardous with benign) and implement closed-loop recycling systems for aqueous and organic streams [10] [9].

- Evaluate Reaction Medium: Challenge the necessity of organic solvents. Explore if water can serve as the reaction medium, or if you can run reactions neater (without solvent) [10].

- Optimize Catalysis: Replace stoichiometric reagents with catalytic systems to minimize by-product formation [9].

Table 2: Troubleshooting High E-Factor in Pharmaceutical Processes

| Problem Area | Root Cause | Potential Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High Solvent Waste | Single-use solvents; inefficient extraction. | Implement solvent recovery and recycling; switch to greener solvents [10]. |

| Low Yield / Selectivity | Unoptimized reaction conditions; side reactions. | Use continuous flow reactors for better control; optimize temperature/catalyst [9]. |

| Excess Reagents | Using more than stoichiometric amounts to drive reactions. | Employ catalysis; precisely control reagent addition with flow chemistry [9]. |

| Inefficient Purification | Reliance on resource-intensive methods like column chromatography. | Switch to crystallization or other lower-waste purification techniques. |

FAQ 3: How can flow chemistry help us reduce our process E-Factor?

Answer: Flow chemistry, or continuous processing, is a powerful tool for E-factor reduction. It enables process intensification, leading to higher efficiency and less waste [9].

Troubleshooting Guide for Implementing Flow Chemistry:

- Problem: Difficulty handling hazardous gases (e.g., H₂, CO) in batch, leading to complex and wasteful procedures.

- Solution: Use a flow reactor to safely handle gases. They can be precisely dosed and efficiently mixed, improving safety and atom economy while reducing waste [9]. Example: Eli Lilly developed a continuous high-pressure hydrogenation process for an API, rated as low-risk compared to the batch alternative [9].

- Problem: Low selectivity in a reaction step, generating unwanted by-products.

- Solution: Leverage the precise temperature and residence time control in flow reactors to enhance reaction selectivity and yield, thereby reducing the waste generated per unit of product [9].

- Problem: Multi-step synthesis requires intermediate isolation, generating significant solvent and solid waste.

- Solution: Develop a telescoped continuous process where reaction streams flow directly from one step to the next, minimizing intermediate work-up and purification [9].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Aqueous Stream Recycling for E-Factor Reduction

This protocol is based on a published case study where recycling aqueous streams reduced the overall E-factor of an anti-retroviral drug synthesis by 90% [10].

Objective

To selectively remove organic and inorganic impurities from aqueous effluent streams generated during API synthesis, enabling the recycling of water and dissolved reagents back into the process.

Principle

A proprietary catalytic formulation (e.g., RCat) is used to treat aqueous waste streams. This formulation selectively targets and breaks down or separates impurities, allowing the clean aqueous medium to be reused in the same chemical step [10].

Materials and Equipment (The Scientist's Toolkit)

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Waste Stream Recycling

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Proprietary Catalytic Formulation (e.g., RCat) | A customized catalytic mixture designed to selectively decompose or separate specific organic and inorganic impurities from aqueous effluent [10]. |

| pH Meter and Adjusters | To maintain the specific acidic, neutral, or alkaline conditions required for effective impurity removal [10]. |

| Liquid-Liquid Separator | For continuous separation of treated aqueous phase from insoluble impurities or spent catalyst. |

| Analytical HPLC/GC | To monitor the concentration of key impurities before and after treatment and confirm stream purity for recycle. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Characterization: Analyze the composition of the aqueous effluent stream (e.g., from a diazotization, hydrolysis, or nitration step) to identify and quantify organic impurities and inorganic salts [10].

- Formulation Selection: Choose or customize a catalytic formulation (

RCat) specific to the impurity profile of the stream. - Process Integration: Introduce the catalytic formulation into the aqueous waste stream.

- Condition Optimization: Adjust parameters such as temperature, pressure, and mixing intensity to maximize impurity removal efficiency.

- Separation: After treatment, separate the purified aqueous stream from the catalyst and any isolated impurities.

- Recycle: Direct the purified aqueous stream back to the beginning of the same process step to replace fresh water.

- Monitoring: Continuously monitor the quality of the recycled stream and the final product to ensure no negative impact on yield or purity.

Expected Outcome

Successful implementation can lead to a drastic reduction in fresh water consumption and a lower E-factor. In the cited case study, this approach, applied across multiple steps, improved the overall yield from 25% to 86% of theoretical yield and reduced total effluent from 9,600 TPA to 1,020 TPA [10].

Workflow Diagram for E-Factor Reduction

The following diagram illustrates a logical decision-making workflow for diagnosing and addressing high E-factor in a pharmaceutical process.

FAQs: Integrating Environmental Impact Assessment into Research

Q1: How can I quickly assess the environmental impact of my chemical process? The E Factor is a fundamental mass-based metric for initial assessment. It is calculated as the total mass of waste produced per unit mass of product. A higher E Factor indicates a less efficient, more wasteful process. This metric powerfully illustrates the significant waste reduction potential in fine chemical and pharmaceutical manufacturing compared to bulk chemicals, providing a clear starting point for optimization efforts [11].

Q2: What is the difference between the E Factor and the Environmental Impact Quotient (EIQ)? The E Factor is a simple metric that focuses exclusively on the mass of waste [11]. The Environmental Impact Quotient (EIQ), developed at Cornell University, is a more complex model that integrates multiple toxicity and environmental fate parameters to estimate a potential risk value for pesticides [12]. While the E Factor measures waste quantity, the EIQ attempts to estimate the potential environmental impact of a substance. Research indicates that for herbicides, the EIQ Field Use Rating can be heavily dominated by the application rate, and some of its risk factors lack quantitative data [13] [14].

Q3: How can I efficiently optimize a reaction to reduce its E Factor? Fractional Factorial Design (FFD) is a highly efficient statistical method for process optimization. When investigating multiple factors (e.g., temperature, catalyst concentration, solvent volume), a full factorial experiment becomes prohibitively large. FFD uses a carefully selected subset of experiments to identify the most influential factors and their optimal settings, dramatically saving time and resources while providing statistically significant insights for E Factor reduction [15].

Q4: What are the key regulatory considerations for managing hazardous pharmaceutical waste in a lab? In the United States, the EPA's Subpart P rule governs hazardous waste pharmaceuticals. Key requirements include [16]:

- Sewer Ban: A strict prohibition on disposing of hazardous waste pharmaceuticals down the drain.

- Container Management: Waste must be stored in closed, compatible, and properly labeled containers.

- Hazardous Waste Determination: You must evaluate all solid waste pharmaceuticals to determine if they are hazardous.

- Record Keeping: Maintain shipment records and manifests for three years.

- Note: State regulations may vary, and not all states have adopted Subpart P.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Addressing a High E Factor

A high E Factor indicates excessive waste generation in your process.

- Problem: Solvents account for over 80% of the process mass intensity.

- Solution:

- Evaluate Solvent Alternatives: Research and test greener solvent alternatives.

- Implement Solvent Recovery: Set up distillation or other recovery systems to purify and reuse solvents.

- Optimize Stoichiometry: Re-examine reactant ratios to minimize excess.

- Problem: Low yield or poor selectivity leading to by-product formation.

- Solution:

- Screen Catalysts: Use experimental design (e.g., FFD) to identify a more selective and active catalyst.

- Optimize Reaction Parameters: Systematically adjust temperature, pressure, and concentration to favor the desired product [15].

Guide 2: Navigating Hazardous Pharmaceutical Waste Disposal

Incorrect disposal can lead to regulatory non-compliance and environmental contamination.

- Problem: Uncertainty in classifying waste as "non-creditable" or "potentially creditable."

- Solution:

- Non-creditable: Wastes for disposal (e.g., expired, spilled, partially used). These must be sent to a permitted disposal facility using a hazardous waste manifest. Label the container "Hazardous Waste Pharmaceuticals." [16]

- Potentially creditable: Unused, unopened pharmaceuticals sent to a reverse distributor for manufacturer credit. These do not require a hazardous waste manifest but need detailed shipping records [16].

- Problem: A spill of a hazardous pharmaceutical occurs in the lab.

- Solution:

- Immediate Action: Contain and clean up the spill immediately using appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE).

- Waste Management: Collect the spill residue and contaminated cleanup materials as hazardous waste [16].

Quantitative Data and Metrics

Table 1: E Factor Benchmarks Across Chemical Industries

| Industry Segment | Typical E Factor (kg waste/kg product) |

|---|---|

| Bulk Chemicals | < 1 to 5 |

| Fine Chemicals | 5 to 50 |

| Pharmaceuticals | 25 to > 100 |

Data adapted from Sheldon (2017) [11].

Table 2: Example EIQ Field Use Rating (EIQ-FUR) Comparison for Fungicides

This table shows how the EIQ-FUR integrates the base EIQ value with the application formulation and rate.

| Material (Active Ingredient) | EIQ | % Active Ingredient | Rate (lb/acre) | EIQ Field Use Rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daconil Ultrex Turf Care (chlorothalonil) | 37.4 | 82.5 | 10.07 | 311 |

| Bayleton 50% WSP (triadimefon) | 27.0 | 50.0 | 2.72 | 36.7 |

| Banner Maxx (propiconazole) | 31.6 | 14.3 | 2.72 | 12.3 |

| Roots EcoGuard Biofungicide (Bacillus licheniformis) | 7.3 | 0.14 | 54.45 | 0.6 |

Data sourced from the Cornell Turfgrass Program [12].

Table 3: Researcher's Toolkit for Waste-Minimising Experiments

| Reagent / Solution | Function in Waste Reduction |

|---|---|

| Heterogeneous Catalysts | Enable easy recovery and reuse from reaction mixtures, minimizing metal waste and reducing E Factor [11]. |

| Biocatalysts (Enzymes) | Often provide high selectivity under mild, aqueous conditions, reducing energy waste and the need for protecting groups [11]. |

| Ionic Liquids / Deep Eutectic Solvents | Serve as alternative solvents with low vapor pressure, potentially reducing volatile organic compound (VOC) emissions and enabling easier recycling [11]. |

| Solid Supports | Used in solid-phase synthesis to simplify purification and minimize solvent waste for complex molecules like pharmaceuticals. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing a Fractional Factorial Design for Reaction Optimization

Objective: To identify key factors influencing reaction yield and E Factor using a reduced number of experiments.

Methodology:

- Define Objectives & Factors: Clearly state the goal (e.g., maximize yield). Select factors (e.g., Temperature, Catalyst Load, Solvent Volume, Stirring Rate) and their high/low levels [15].

- Choose Fraction: For

kfactors, a full factorial requires2^kruns. A half-fraction design2^(k-1)halves the experiments. Software (e.g., R, JMP, Minitab) is used to generate the design matrix [15]. - Develop Design Matrix: The matrix specifies the factor levels for each experimental run.

Example design matrix for a

2^(4-1)half-fraction experiment:Run Temp Catalyst Solvent Stir Rate 1 Low Low Low Low 2 Low Low High High 3 Low High Low High 4 Low High High Low 5 High Low Low High 6 High Low High Low 7 High High Low Low 8 High High High High - Execute & Analyze: Run experiments in randomized order. Measure responses (yield, E Factor). Use statistical analysis (e.g., regression, ANOVA) to identify significant main effects and interactions [15].

Protocol 2: Calculating E Factor and Process Mass Intensity (PMI)

Objective: To quantitatively evaluate the mass efficiency of a synthetic process.

Methodology:

- Document Input Masses: Accurately record the masses of all reactants, solvents, catalysts, and reagents used in the reaction and work-up/purification stages.

- Record Product Mass: Weigh the final, purified product.

- Calculate E Factor:

- Total Waste Mass = (Total mass of inputs) - (Mass of product)

- E Factor = (Total Waste Mass) / (Mass of product) [11]

- Calculate Process Mass Intensity (PMI): An alternative metric recommended by the ACS Green Chemistry Institute.

- PMI = (Total mass of inputs) / (Mass of product)

- Note: PMI = E Factor + 1

Experimental Workflows and Pathways

Waste Reduction Strategy Map

This diagram outlines a logical pathway for implementing waste reduction strategies in research, moving from assessment to advanced solutions.

Hazardous Pharmaceutical Waste Decision Workflow

This workflow provides a step-by-step guide for the proper classification and management of pharmaceutical waste in a laboratory setting, compliant with EPA Subpart P guidelines [16].

For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the pursuit of efficiency is not only a scientific challenge but also an economic and environmental imperative. The E-factor (Environmental Factor), defined as the total waste produced per kilogram of desired product, provides a key metric for assessing the sustainability of manufacturing processes, particularly in the pharmaceutical industry. A high E-factor signifies not only environmental burden but also substantial operational inefficiency and cost. This article frames waste reduction squarely within this research context, demonstrating how strategies that lower the E-factor directly translate into reduced manufacturing and disposal costs. By adopting the methodologies and troubleshooting guides outlined herein, research teams can make a compelling business case for sustainable science.

The Financial and Operational Imperative

Implementing a waste reduction program is a powerful strategy for improving the bottom line. The financial benefits are quantifiable and significant, directly impacting key operational metrics relevant to any research-driven manufacturing facility.

Table 1: Financial Benefits of Waste Reduction and Recycling Programs [17]

| Benefit Category | Mechanism | Typical Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Lower Waste Disposal Costs | Diverting waste from landfills reduces volume/weight-based disposal fees. | Waste-related costs can be reduced by 50% or more; fewer required waste hauler pickups. |

| Revenue Generation | Selling valuable by-products and scraps (e.g., metals, certain solvents, plastics). | Turns waste into a revenue stream; higher returns for pre-sorted materials. |

| Reduced Raw Material Costs | Reusing leftover materials or reprocessing off-spec intermediates in subsequent production runs. | Lowers the need for virgin raw materials, leading to substantial long-term savings. |

| Enhanced Operational Efficiency | Process optimization and waste stream analysis reveal inefficiencies and unnecessary waste. | Leads to more efficient material use, less waste generation, and smoother production. |

Beyond direct cost savings, a strong waste reduction program strengthens regulatory compliance, reducing the risk of fines, and enhances brand reputation with eco-conscious partners and clients [17]. For research institutions, this can translate into an advantage in securing grants and industry partnerships.

Troubleshooting Common Waste Reduction Challenges

Even well-designed experiments and processes can encounter obstacles in waste minimization. The following guide addresses specific, high-impact issues that researchers may face.

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for Waste Reduction Initiatives [18]

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions & Best Practices |

|---|---|---|

| High Contamination in Recyclable Streams | Lack of education on proper recycling practices; incorrect disposal of non-recyclables. | Implement clear, well-labeled recycling stations [17]. Conduct regular training and awareness campaigns to educate staff on what is and is not recyclable [18]. |

| Low Market Demand for Recycled Materials | Low oil prices making virgin plastics cheaper; perceived lower quality of recycled materials. | Explore internal reuse opportunities for materials. Partner with procurement to specify the use of recycled-content materials where viable [18]. |

| Inadequate Funding for Recycling Programs | Lack of visibility into the long-term financial benefits; viewed as a cost center, not a savings source. | Conduct a waste audit to build a data-driven business case. Highlight the ROI from reduced disposal fees and potential revenue [17] [18]. |

| Inefficient Processes Generating Excess Waste | Outdated or unoptimized experimental protocols and production techniques. | Conduct a process-level waste audit (see Protocol 1). Apply lean manufacturing principles to identify and eliminate non-value-add activities and "hidden" waste [19]. |

Experimental Protocol for Process Waste Auditing

A waste audit is the fundamental first step in any serious E-factor reduction strategy. This protocol provides a detailed methodology for quantifying and characterizing waste streams in a research or pilot-scale manufacturing environment.

Protocol 1: Detailed Waste Audit for Process Improvement

Objective: To identify the types, quantities, and sources of waste generated by a specific experimental process or manufacturing run, establishing a baseline E-factor and pinpointing opportunities for reduction.

Materials:

- Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): Gloves, lab coat, safety glasses.

- Sample Containers: Sealable, chemically compatible containers for waste sampling.

- Data Collection Sheets: Physical or digital sheets for recording observations.

- Weighing Scales: Calibrated scales appropriate for the expected waste volumes.

- Sorting Equipment: Trays, bins, and tools for safe manual sorting.

Methodology: [17]

Pre-Audit Planning:

- Define Scope: Select a specific process, experiment, or production campaign to audit.

- Assemble Team: Include members familiar with the process (scientists, technicians) and facilities/ waste management.

- Identify Generation Points: Map all points in the process where waste is generated, from raw material handling to final product purification and packaging.

Waste Collection and Sorting:

- Over a representative time period (e.g., multiple identical experimental runs), collect waste segregated by generation point.

- Weigh and Record: Weigh each segregated waste stream and record the data.

- Characterize Waste: For each stream, categorize the waste (e.g., hazardous solvent, plastic packaging, aqueous waste, failed product batches). Note opportunities for recycling, reuse, or recovery.

Data Analysis and Reporting:

- Calculate E-Factor: For the process, calculate the total mass of waste produced and divide by the mass of the desired product. Compare this to industry benchmarks or previous data.

- Identify High-Impact Streams: Pinpoint the waste streams that contribute the most to the total waste mass and disposal cost.

- Generate Report: Summarize findings, including quantitative data and recommendations for waste reduction, reuse, or recycling.

Visualizing the Waste Reduction Workflow

The following diagram, created using Graphviz, outlines the logical workflow for implementing and maintaining a waste reduction program within a research or development context. The colors used adhere to the specified palette and contrast rules.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions for Waste Minimization

Strategic selection and management of research reagents is critical for reducing the E-factor at the laboratory scale. The following table details key material solutions and their functions in waste prevention.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Waste Minimization

| Reagent / Material Solution | Primary Function | Role in Waste Reduction |

|---|---|---|

| Catalytic Reagents | Accelerates reactions without being consumed. | Replaces stoichiometric reagents, dramatically reducing the mass of waste generated per reaction. A cornerstone of green chemistry. |

| Recyclable Solvents & Reagents | Reaction medium or participant designed for recovery. | Allows for closed-loop systems within the lab or process, reducing the volume of hazardous waste and the cost of virgin materials. |

| Supported Reagents | Reagent immobilized on a solid support (e.g., polymer, silica). | Simplifies purification (e.g., via filtration), reducing the need for large volumes of extraction solvents and generating less complex aqueous waste. |

| Digital Analytical Standards | Virtual calibration for instruments. | Reduces or eliminates the chemical waste associated with the production, packaging, and disposal of traditional physical standard solutions. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How can we justify the upfront cost of new, waste-reducing equipment or reagents to our finance department? A: Build a business case focused on the total cost of ownership. Highlight not only the direct cost savings from reduced raw material consumption and lower waste disposal fees [17] but also the potential for increased throughput and reduced regulatory burden. Many companies see a return on investment within a year [19].

Q2: Our lab is small. Can these waste reduction strategies still be effective for us? A: Absolutely. The principles of lean manufacturing and waste reduction are scalable [19]. Start with a simple waste audit of your most common experiment. Small steps, like standardizing solvent choices for easier recycling or optimizing reaction scales to avoid overproduction, can yield significant cost and waste savings.

Q3: What is the most common mistake in setting up a lab recycling program? A: The most common issue is contamination due to a lack of clear education and proper infrastructure [18]. Placing a non-recyclable item or a dirty container into a recycling stream can render the entire batch unrecyclable. The solution is to provide well-labeled, specific bins and continuous team education [17].

Q4: How does a circular economy model apply to pharmaceutical research and development? A: In an R&D context, a circular economy focuses on creating closed-loop systems for materials. This can involve designing processes for atom economy, selecting reagents that can be easily recovered and reused, and implementing systems for recycling solvents and water within pilot plants. This model reduces dependency on virgin raw materials and minimizes waste [19].

In the pursuit of sustainable chemical manufacturing, waste prevention stands as the foundational principle of Green Chemistry [20]. The E-Factor, defined as the total mass of waste produced per unit mass of desired product, provides a simple yet powerful quantitative metric to drive this principle into practice [21] [6]. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering E-factor reduction is not merely an environmental consideration but a crucial strategy for improving process efficiency, reducing costs, and enhancing overall sustainability profiles [20] [6]. This technical support center articulates how deliberate application of the 12 Principles of Green Chemistry directly enables E-factor optimization, providing practical methodologies and troubleshooting guidance for implementation at the research and development stage.

Understanding E-Factor: Calculation and Industry Benchmarks

E-Factor Calculation Methodology

The E-Factor provides a straightforward calculation for assessing process efficiency:

[ \textrm{E-Factor} = \frac{\textrm{Total mass of waste from process (kg)}}{\textrm{Total mass of product (kg)}} ]

Calculation Notes:

- Waste Definition: Includes waste byproducts, leftover reactants, solvent losses, spent catalysts, and catalyst supports [21].

- Water Consideration: Water is typically excluded from the calculation unless it is severely contaminated and difficult to reclaim [21].

- Recycled Materials: Leftover reactants that can be easily reclaimed and recycled are not counted as waste [21].

Industry E-Factor Benchmarks

The acceptable E-Factor varies significantly across chemical industry sectors, reflecting differences in product value and process complexity [21] [6]:

Table: E-Factor Values Across Chemical Industry Sectors

| Industry Sector | Annual Production Volume | Typical E-Factor Range (kg waste/kg product) |

|---|---|---|

| Oil Refining | 10⁶–10⁸ tons | <0.1 |

| Bulk Chemicals | 10⁴–10⁶ tons | <1–5 |

| Fine Chemicals | 10²–10⁴ tons | 5–50 |

| Pharmaceuticals | 10–10³ tons | 25–>100 |

The pharmaceutical industry's characteristically higher E-Factors result from multi-step syntheses requiring high-purity intermediates and complex separation protocols [6]. However, this also presents significant opportunities for improvement through green chemistry implementation.

The Strategic Alignment: E-Factor Reduction Through the 12 Principles

The following diagram illustrates how multiple Green Chemistry principles strategically contribute to the overarching goal of E-Factor reduction:

Technical Guidance: Implementing Principles for E-Factor Reduction

Core Principles Directly Impacting E-Factor

Table: Primary E-Factor Reduction Principles and Implementation Strategies

| Principle | Mechanism for E-Factor Reduction | Experimental Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Prevention (Principle 1) | Directly minimizes waste generation at source rather than after creation [20]. | Design processes to maximize mass incorporation; employ process mass intensity (PMI) tracking [22]. |

| Atom Economy (Principle 2) | Maximizes incorporation of starting materials into final product [20]. | Select synthetic pathways with inherent high atom economy; use rearrangement reactions over stoichiometric oxidations/reductions [20]. |

| Catalysis (Principle 9) | Replaces stoichiometric reagents with catalytic systems that generate less waste [22]. | Implement enzymatic, heterogeneous, or organocatalytic cycles instead of stoichiometric reagents [20]. |

| Safer Solvents & Auxiliaries (Principle 5) | Reduces mass and hazard of solvent waste, which often constitutes bulk of process mass [20]. | Substitute hazardous solvents with safer alternatives; implement solvent recovery systems; explore solvent-free conditions [20]. |

Supporting Principles for Comprehensive E-Factor Management

Less Hazardous Chemical Syntheses (Principle 3) focuses on using and generating substances with minimal toxicity [20]. While this doesn't directly reduce waste mass, it significantly decreases the environmental impact of the waste measured by E-Factor, potentially reducing regulatory burden and disposal costs [20].

Designing for Energy Efficiency (Principle 6) contributes indirectly to E-Factor reduction by minimizing energy-intensive purification steps that often generate significant waste [22].

Frequently Asked Questions: E-Factor in Practice

Q1: How does E-Factor differ from atom economy as a green chemistry metric?

A1: While both measure process efficiency, they evaluate different aspects:

- Atom Economy is a theoretical calculation based solely on molecular weights of reactants versus products, predicting waste from the reaction equation itself [20] [22].

- E-Factor is an empirical measurement of actual waste generated during the entire process, including solvents, purification materials, and actual yields [21] [6].

A reaction can have high atom economy but still produce a high E-Factor if it requires large solvent volumes or extensive purification [21].

Q2: What is the relationship between E-Factor and Process Mass Intensity (PMI)?

A2: PMI and E-Factor are directly related through the formula: E-Factor = PMI - 1 [6]. PMI expresses the total mass of materials used per mass of product, providing a complementary metric favored by the ACS Green Chemistry Institute Pharmaceutical Roundtable for its straightforward calculation from known process inputs [20] [6].

Q3: Our pharmaceutical process has an E-Factor of 40. Is this acceptable, and how might we improve it?

A3: While E-Factors in pharmaceutical manufacturing typically range from 25 to >100 [6], there is always opportunity for improvement. Consider these strategies:

- Conduct a mass balance analysis to identify the largest waste streams (often solvents) [21]

- Implement catalyst recovery systems [20]

- Redesign purification protocols to reduce solvent volumes [22]

- Explore synthetic route alternatives with higher atom economy [20]

Successful case studies demonstrate dramatic improvements; for example, sertraline hydrochloride (Zoloft) manufacturing achieved an E-Factor of 8 through process redesign [6].

Q4: Does E-Factor account for the environmental impact of different waste types?

A4: No, this is a recognized limitation of the basic E-Factor metric [21] [6]. It measures waste quantity but not hazard. The Environmental Quotient (EQ) was proposed to address this by multiplying the E-Factor by an arbitrarily assigned unfriendliness quotient (Q) [21]. Additionally, metrics like EcoScale incorporate hazard considerations through penalty points assigned based on safety, toxicity, and environmental impact [22].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common E-Factor Reduction Challenges

Table: E-Factor Reduction Challenges and Solutions

| Challenge | Potential Root Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High solvent-related waste | Inefficient extraction/purification; No solvent recovery | Implement solvent recovery systems; Switch to solvent-free or concentrated conditions; Explore alternative solvent selection [20] |

| Low atom economy | Poor synthetic route selection; Overuse of protecting groups | Redesign synthetic pathway using rearrangement or addition reactions; Apply catalysis to avoid stoichiometric reagents [20] |

| High energy consumption contributing to waste | Energy-intensive reaction conditions (high T/P); Lengthy purification processes | Optimize reaction conditions for ambient temperature/pressure; Employ catalytic alternatives to reduce energy requirements [22] |

| Difficulty comparing greenness of alternative processes | E-Factor alone doesn't capture all environmental factors | Use complementary metrics: EcoScale for technical/hazard factors [22]; PMI for material efficiency [20] |

Research Reagent Solutions for E-Factor Optimization

Table: Essential Tools for E-Factor-Driven Research

| Reagent/Material | Function in E-Factor Reduction | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Heterogeneous Catalysts | Enable catalyst recovery and reuse, reducing metal waste | Particularly valuable for transition metal catalysts; allows filtration recovery instead of aqueous workup [20] |

| Biocatalysts (Enzymes) | Provide highly selective catalysis under mild conditions | Reduce byproducts, energy requirements, and purification waste; high selectivity improves atom economy [20] |

| Safer Solvent Alternatives | Reduce hazard and disposal burden of solvent waste | Consult ACS Green Chemistry Institute solvent selection guides; water and bio-based solvents often offer advantages [20] |

| Process Mass Intensity (PMI) Tracking Tools | Quantify material efficiency and identify improvement areas | Spreadsheet templates or process chemistry software; essential for benchmarking and continuous improvement [20] |

The E-Factor serves as a crucial bridge between the theoretical framework of the 12 Principles of Green Chemistry and practical, measurable outcomes in chemical research and development [20] [6]. By systematically addressing E-Factor reduction through targeted application of these principles—particularly prevention, atom economy, catalysis, and safer solvents—research teams can significantly advance waste prevention goals while developing more efficient and sustainable synthetic methodologies [20] [21] [22]. The troubleshooting guides and FAQs presented here provide immediate starting points for implementing these strategies in ongoing drug development and research programs.

Practical Strategies for E-Factor Reduction in API Synthesis and Manufacturing

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ: Fundamental Concepts

Q1: How does replacing stoichiometric reagents with catalysts directly contribute to E-factor reduction?

The replacement of stoichiometric reagents with catalytic alternatives is a core strategy for waste minimization because it fundamentally changes the reaction economics. Stoichiometric methods generate significant byproducts, as the reagent is consumed and becomes waste. In contrast, a catalyst is not consumed; it facilitates the reaction and can be reused for multiple turnover cycles, dramatically reducing the mass of waste generated per mass of product. This direct reduction in material consumption and waste output is a primary lever for improving the E-factor, which is a key metric for environmental impact in chemical processes [23].

Q2: What are the key differences in infrastructure between stoichiometric and catalytic processes that I should consider during scale-up?

Scaling a catalytic process requires careful attention to unique operational parameters not typically encountered in stoichiometric methods. The key differences are summarized in the table below:

Table: Key Considerations for Scaling Catalytic Processes

| Aspect | Stoichiometric Process | Catalytic Process |

|---|---|---|

| Reagent Consumption | High (consumed) | Low (not consumed, high turnover number) |

| Waste Generation | High, directly proportional to product mass | Low, primarily from catalyst lifecycle and separation |

| Process Monitoring | Focus on reaction completion | Focus on catalyst lifetime, stability, and deactivation |

| Critical Parameters | Purity, stoichiometry | Temperature control, pressure, mixing efficiency |

| Typical Equipment | Batch reactors | Often requires specialized reactors for optimal catalyst contact |

Industrial scale-up of catalytic processes is capital-intensive and requires multidisciplinary teams to address challenges such as the effects of operational variables (pressure, temperature, feed purity) on catalyst life and performance. Trace contaminants can build up and poison catalysts, necessitating robust purification steps and process control [23].

Q3: Which catalytic materials show the most promise for C-C bond formation and C-H activation in alkane upgrading?

Research indicates significant promise for "atomically-precise" supported catalysts. The activity and selectivity in reactions like catalytic olefins upgrading (dimerization, metathesis) and non-oxidative dehydrogenation of light alkanes are controlled by the electronic communication between the active site and the support or a promoter metal [24]. Furthermore, multimetallic sub-nanometer nanoparticles have shown attractive properties for thermal dehydrogenation due to their increased activity and selectivity, although their mechanistic underpinnings are still a primary focus of research [24].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues

Problem 1: Rapid Catalyst Deactivation

- Observation: High initial conversion that drops significantly over short time periods.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Poisoning: Trace contaminants (e.g., heavy metals, sulfur compounds) in the feed can deactivate the catalyst.

- Action: Implement more rigorous purification of feedstocks and solvents. Use analytical techniques to identify poisons.

- Sintering: Aggregation of active metal particles, often due to excessively high local temperatures.

- Action: Optimize temperature control and consider catalysts with stabilizers or supports designed to prevent particle migration.

- Coking/Fouling: Deposition of carbonaceous material blocking active sites.

- Action: Modify reaction conditions (e.g., introduce a co-feed, adjust H2 partial pressure) or implement periodic regeneration cycles.

- Poisoning: Trace contaminants (e.g., heavy metals, sulfur compounds) in the feed can deactivate the catalyst.

- Related Protocol: To test for thermal stability, run the catalyst at the target temperature without feed and then re-test activity.

Problem 2: Poor Selectivity to Desired Product

- Observation: The reaction proceeds, but yields a mixture of unwanted byproducts instead of the target molecule.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Incorrect Active Site Geometry: The catalyst may not be "tuning" the complex energy landscape correctly for the desired pathway [24].

- Action: Explore different catalyst supports or promoter metals to modify electronic properties. For example, PtZn alloy nanoclusters have shown high selectivity for n-butane dehydrogenation to 1,3-butadiene [24].

- Mass Transfer Limitations: Reactants cannot access the internal pores of a heterogeneous catalyst fast enough, leading to secondary reactions.

- Action: Use catalysts with smaller particle sizes or different pore structures. Increase agitation speed.

- Incorrect Active Site Geometry: The catalyst may not be "tuning" the complex energy landscape correctly for the desired pathway [24].

- Related Protocol: Perform a kinetic analysis at different stirring speeds to rule out external mass transfer limitations.

Problem 3: Low Catalyst Turnover Number (TON)

- Observation: The catalyst is active but requires a high loading to achieve useful conversion, undermining the economic and waste-reduction benefits.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Insufficient Active Sites: The synthesis may not be generating enough functionally active centers.

- Action: Refine catalyst preparation protocols, such as Atomic Layer Deposition (ALD), to ensure higher and more uniform dispersion of active sites [24].

- Non-Productive Side Reactions: The catalyst may be engaged in cycles that do not lead to the main product.

- Action: Use advanced characterization techniques (in situ spectroscopy) to study the reaction mechanism and identify deactivation pathways [24].

- Insufficient Active Sites: The synthesis may not be generating enough functionally active centers.

- Related Protocol: Use the high-performance computing capabilities to develop activity-descriptor relationships that can guide the rational design of more efficient catalysts [24].

Quantitative Data & Performance Metrics

Table: Comparative E-Factor Analysis: Stoichiometric vs. Catalytic Routes

This table provides estimated E-factors (kg waste / kg product) for common transformations, highlighting the waste reduction potential of catalysis.

| Transformation Type | Stoichiometric Method (Example) | Estimated E-Factor | Catalytic Alternative (Example) | Estimated E-Factor | Key Waste Avoided |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxidation | Chromium-based oxidants | 5 - 50+ | Catalytic O2 (e.g., Pd, Mn) | <1 - 5 | Cr salts, heavy metal waste |

| Hydrogenation | Stoichiometric metals (e.g., Zn, Fe) | 10 - 100+ | Heterogeneous H2 (e.g., Pt, Ni) | <1 - 10 | Metal oxides, salts |

| Cross-Coupling | Stochiometric organometallics | 25 - 100+ | Pd-catalyzed coupling | 5 - 25 | Metal halides, salts |

| Dehydrogenation | Stoichiometric oxidants | 10 - 50+ | Heterogeneous catalysis (e.g., PtZn) [24] | <1 - 10 | Reduced metal oxides |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Hydrogenolysis of Polyethylene for Upcycling

This protocol outlines the catalytic transformation of waste polyethylene into liquid hydrocarbons, a direct application of waste minimization [24].

- Objective: Catalytically depolymerize high molecular weight polyethylene into a narrow distribution of liquid hydrocarbons via selective C−C bond hydrogenolysis.

- Materials:

- Catalyst: Platinum nanoparticles supported on SrTiO3 perovskite nanocuboids, prepared by Atomic Layer Deposition (ALD) [24].

- Substrate: High-density polyethylene (HDPE).

- Reactor: High-pressure Parr reactor.

- Procedure:

- Load the reactor with polyethylene and the Pt/SrTiO3 catalyst.

- Purge the reactor with an inert gas (e.g., N2 or Ar) to remove air.

- Pressurize the reactor with H2 to the target pressure (typically 10-50 bar).

- Heat the reactor to the target temperature (e.g., 300°C) with constant stirring.

- Maintain reaction conditions for a set period (e.g., 2-24 hours).

- Cool the reactor to room temperature and carefully release the pressure.

- Separate the liquid and solid products. The liquid can be analyzed by Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) and Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) to determine the molecular weight distribution of the products.

- Troubleshooting: If conversion is low, confirm the catalyst's metal dispersion and ensure effective mixing to avoid mass transfer limitations.

Protocol 2: Evaluating Supported Organometallic Catalysts for Alkane Dehydrogenation

This protocol describes testing a catalyst for the non-oxidative dehydrogenation of light alkanes, a key reaction for shale gas valorization [24].

- Objective: Assess the activity and selectivity of a supported "atomically-precise" catalyst for the dehydrogenation of propane to propylene.

- Materials:

- Catalyst: Supported organovanadium(III) or organoiridium(III) pincer complexes on a selected support (e.g., silica, sulfated zirconia) [24].

- Feedstock: Propane gas stream.

- Apparatus: Fixed-bed flow reactor system equipped with online GC.

- Procedure:

- Pack the catalyst into the fixed-bed reactor tube.

- Activate the catalyst in situ under a specified gas flow (e.g., H2 or He) at elevated temperature.

- Set the reactor to the desired temperature and introduce the propane feed at a controlled flow rate using a mass flow controller.

- Allow the system to stabilize, then periodically sample the effluent stream using the online GC to analyze for propylene and byproducts.

- Calculate key performance metrics: Conversion (% propane converted), Selectivity (% converted propane that becomes propylene), and Turnover Frequency (moles of propylene formed per mole of active site per hour).

- Troubleshooting: A rapid decline in selectivity often indicates catalyst coking; a reduction in overall activity may suggest sintering or poisoning.

Process Visualization & Workflows

Diagram: Catalytic Process Development and Troubleshooting Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials for Catalytic Alkane Upgrading Research

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Key Characteristic / Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Supported Organovanadium(III) | Catalyst for hydrocarbon hydrogenation and dehydrogenation [24]. | High activity and selectivity; mechanistic insights available [24]. |

| Atomically-Dispersed Pt on Zn/SiO2 | Catalyst for chemo-selective hydrogenation of nitro compounds [24]. | Prevents over-reduction and provides high selectivity. |

| PtZn Alloy Nanoclusters | Catalyst for deep dehydrogenation of n-butane to 1,3-butadiene [24]. | Example of bimetallic catalyst with enhanced selectivity [24]. |

| Organoiridium(III) Pincer Complex on Sulfated ZrO2 | Catalyst for hydrocarbon activation and functionalization [24]. | Demonstrates the role of strong metal-support interactions. |

| Atomic Layer Deposition (ALD) System | Precision synthesis of supported nanoparticles [24]. | Enables creation of "atomically-precise" catalysts for structure-function studies [24]. |

| SrTiO3 Perovskite Nanocuboids | Catalyst support for plastic hydrogenolysis [24]. | Defined morphology and electronic properties aid in selective C−C bond scission [24]. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

This section addresses common challenges in solvent optimization for reducing the E-factor, a key metric for waste in chemical processes.

FAQ 1: What are the most effective first steps to reduce our process E-factor?

The most effective initial strategy is to focus on solvent selection and recycling. Solvents typically account for 80-90% of the total mass of non-aqueous material used in pharmaceutical manufacture and the majority of waste formed [25]. To take action:

- Use a Solvent Selection Guide: Replace hazardous or undesirable solvents (coded red) with preferred (green) alternatives, such as ethanol or 2-methyl-THF, based on in-house guides from major pharmaceutical companies [25].

- Implement Solvent Recycling: Set up a recycling protocol for mixed solvents. For example, a simple density-based method for ethyl acetate/hexane mixtures can reduce laboratory solvent waste by 20-40 liters per week [26].

FAQ 2: How can we quantitatively compare the environmental performance of different solvent options?

Use a combination of mass-based and impact-based metrics. The E-factor is a simple, mass-based metric calculating total waste per kg of product [25]. For a more comprehensive view, complement it with tools that assess the nature of the waste:

- Green Motion Penalty Point System: This system assesses seven fundamental concepts (e.g., raw materials, solvent selection, hazard and toxicity) and deducts penalty points from 100. A higher score indicates a more sustainable process with lower environmental impact [25].

- Environmental Assessment Tool for Organic Syntheses (EATOS): This software assigns penalty points to waste based on human and eco-toxicity, providing a potential environmental impact (PEI) score [25].

FAQ 3: Our reaction requires a specific solvent mixture for optimal yield. How can we make this sustainable?

Optimize the solvent system using computational tools and recover it for reuse.

- Computational Optimization: Use software like COSMO-RS/SOLVPRED to predict an optimal solvent mixture that maximizes solubility or extraction efficiency from a large set of possible solvents, minimizing the need for extensive trial-and-error experiments [27] [28].

- Density-Based Recovery and Reformulation: For common binary mixtures like ethyl acetate/hexane, you can use solution density as an accurate (±1%) assay method. After use, distill the mixture and use a pre-calculated reformulation chart to adjust its composition by adding pure solvents, returning it to the required ratio for subsequent runs [26].

FAQ 4: How do we balance solvent safety with green chemistry principles in the lab?

Safety and green chemistry are complementary. Adhere to these key guidelines [29]:

- Consult Safety Data Sheets (SDS) for specific solvent hazards.

- Handle solvents in fume hoods to maintain vapor concentrations below exposure limits.

- Use spill kits and clean spills immediately.

- Select appropriate gloves for the solvent, as chemical resistance varies greatly by glove material.

- Isolate ignition sources from solvent use areas.

- Never use solvents to wash skin.

Quantitative Data for Solvent Selection and Recycling

Table 1: E-factor Benchmarks Across Industry Sectors [25]

| Industry Sector | Typical E-factor Range (kg waste/kg product) |

|---|---|

| Oil Refining | <0.1 |

| Bulk Chemicals | <1-5 |

| Fine Chemicals | 5 - 50 |

| Pharmaceuticals | 25 - 100+ |

| Pharmaceuticals (API, cEF) | Average: 182 (Range: 35 - 503) |

Table 2: Performance Data for Solvent Recycling Protocols [26]

| Recycling Protocol | Key Performance Metric | Accuracy / Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Density-based quantification (EA/Hex) | Quantification of solvent mixture composition | ±1% accuracy |

| Standard recycling program implementation | Reduction in laboratory solvent waste volume | 20 - 40 liters reduced per week |

| General implementation in academic labs | Reduction in overall solvent consumption | Consumption reduced by approximately 50% |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Density-Based Quantification and Reformulation of Ethyl Acetate/Hexane Mixtures [26]

This protocol allows for the recovery and reuse of a common chromatography solvent mixture.

- Collection and Distillation: Collect all used ethyl acetate/hexane (EA/Hex) mixtures from reactions and work-ups in a dedicated, labeled container. Distill the mixed solvent to recover a relatively pure binary mixture.

- Density Measurement: Measure the density of the distilled solvent mixture at a constant temperature (e.g., 20°C).

- Composition Determination: Use a pre-established calibration curve (density vs. composition) to determine the exact volume-to-volume ratio of EA to Hex in the mixture.

- Reformulation: Consult a reformulation chart to determine the volumes of pure ethyl acetate or hexane required to adjust the recycled mixture to the desired working concentration (e.g., 1:4 EA/Hex for normal-phase chromatography).

- Quality Check: The recycled and reformulated solvent is now ready for reuse in non-critical applications. Test its performance against a fresh solvent mixture in a standard assay to ensure suitability.

Protocol 2: Recovery of Wash Acetone [26]

- Dedicated Collection: Collect acetone used for washing glassware or precipitating products in a separate container from other solvent wastes.

- Drying and Filtration: Add a suitable drying agent (e.g., molecular sieves) to remove water. Filter to remove any particulate matter or dissolved non-volatile impurities.

- Simple Distillation: Distill the dried acetone to recover a product of suitable purity for general laboratory cleaning and washing purposes.

Workflow Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools and Methods for Solvent Optimization

| Tool / Method | Primary Function | Key Context for Use |

|---|---|---|

| E-factor | Measures mass efficiency of a process (kg waste/kg product) [25]. | Baseline assessment and ongoing monitoring of waste reduction efforts. |

| Complete E-factor (cEF) | E-factor including solvents and water with no recycling [25]. | Provides a worst-case scenario assessment for solvent-heavy processes. |

| Solvent Selection Guides | Traffic-light system (Green/Amber/Red) to rank solvents by EHS criteria [25]. | Initial solvent choice for new processes and replacement of hazardous solvents. |

| COSMO-RS / SolvPred | Computational prediction of optimal solvent or solvent mixture [27] [28]. | Replacing trial-and-error for solubility or extraction problems. |

| Hansen Solubility Parameters (HSP) | Quantify the solubility behavior of materials based on polarity and bonding [28]. | Rational solvent selection for polymers and functional materials. |

| Density-Based Quantification | Accurately determines the composition of binary solvent mixtures [26]. | Enables precise reformulation of recycled solvent mixtures for reuse. |

| Green Motion System | Provides an overall sustainability score for a process across multiple metrics [25]. | Comparative route selection and final process evaluation. |

Continuous flow chemistry is a transformative approach to chemical synthesis, where reactants are continuously pumped through a reactor system, enabling precise control over reaction parameters. This methodology aligns directly with the core principles of green chemistry and is a powerful strategy for reducing the Environmental Factor (E-Factor)—the ratio of waste produced to desired product obtained. Unlike traditional batch processes, which often struggle with heat and mass transfer inefficiencies leading to byproducts and waste, flow chemistry offers a pathway to enhanced selectivity, higher yields, and significantly reduced solvent and reagent consumption [30] [31] [32].

The inherent advantages of flow systems—such as small reactor volumes, excellent thermal management, and the ability to safely employ hazardous reagents—contribute to a lower E-factor. Furthermore, the ease of integrating in-line purification and real-time analytics minimizes purification waste, solidifying its role in modern waste prevention strategies within research and industrial settings, particularly in pharmaceutical development [33] [31].

Troubleshooting Common Flow Chemistry Issues

This section addresses specific, frequently encountered challenges in continuous flow systems, providing targeted solutions to ensure robust and efficient operation.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. How can I prevent clogging in my flow reactor, especially when handling slurries or forming precipitates? Clogging is a common issue in microreactors. Effective strategies include:

- Applying Ultrasound: Placing the reactor tubing or components in an ultrasonic bath can disrupt particle aggregation and prevent blockages [33].

- Using Diluted Streams: Operating at lower concentrations can prevent precipitation at the point of mixing.

- Optimizing Reactor Design: Employing reactors with wider channel diameters or oscillatory flow patterns can handle slurries more effectively [31].

2. My flow reaction yield is inconsistent. What are the primary factors to check? Inconsistent yields often stem from poor control over fundamental reaction parameters. Systematically investigate:

- Residence Time: Verify that your flow rate is stable and calibrated. Fluctuations directly alter how long reactants are in the reaction zone [34].

- Mixing Efficiency: Ensure your T-mixers or other mixing units are appropriate for the flow rates and viscosities of your reagents. Inadequate mixing leads to concentration gradients and side reactions [35].

- Temperature Control: Confirm that the reactor temperature is uniform and stable throughout the experiment [32].

3. How can I accurately scale up a flow reaction from milligram to gram or kilogram scale? A key advantage of flow chemistry is its straightforward scalability. Instead of "scaling up" a single reactor, the process is typically scaled out by:

- Numbering-Up: Running multiple identical reactors in parallel. This preserves the reaction environment and performance achieved at the laboratory scale [33] [32].

- Increasing Channel Dimensions: For some systems, moving from micro to meso-scale reactors with larger internal diameters allows for higher throughput while maintaining good control.

4. What are the best practices for handling hazardous or unstable intermediates in flow? Flow chemistry is exceptionally well-suited for this purpose. The small inventory of reactive material at any given moment minimizes safety risks. Key practices include:

- In-line Generation and Immediate Consumption: Hazardous intermediates like azides or organometallics can be generated and consumed within a closed, contained system before they can accumulate [31].

- Precise Temperature Control: Exothermic reactions can be managed safely due to the high surface-area-to-volume ratio, enabling efficient heat exchange [32].

- Telescoping Reactions: Coupling multiple synthetic steps in a single flow stream avoids the need to isolate and handle dangerous intermediates [31].

Advanced Techniques for Process Intensification

Integrating Enabling Technologies for Synergistic Effects Combining flow chemistry with alternative energy sources can lead to dramatic process improvements [33].

- Ultrasound-Flow Hybrid Systems: As mentioned, ultrasound prevents clogging. It can also enhance mass transfer and reaction rates in biphasic mixtures through cavitation-induced turbulence [33].

- Photochemical Flow Reactors: Flow allows for uniform and efficient irradiation of the reaction stream, overcoming the penetration depth limitations of batch photochemistry.

- Electrochemical Flow Reactors: Flow electrochemistry offers superior control over electrode potential and current density. The close proximity of electrodes increases efficiency and often eliminates the need for a supporting electrolyte, reducing waste [36].

Diagram: Troubleshooting Logic Flow for Suboptimal Yield

Quantitative E-Factor Analysis: Batch vs. Flow

The following table summarizes documented cases where a switch from batch to continuous flow chemistry resulted in significant process intensification and waste reduction. The E-Factor is a key metric for assessing environmental impact in chemical processes.

Table: E-Factor Reduction through Continuous Flow Chemistry

| API/Target Molecule | Batch Process E-Factor | Continuous Flow E-Factor | Key Improvement Factors | Source/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aliskiren Hemifumarate | High (Process took 48 hours) | Significantly Lower | Reaction time reduced from 48h to 1h; solvent-free steps implemented [31]. | Novartis-MIT Center |

| Ibuprofen | Not Specified | Low (83% overall yield) | Total synthesis time of 3 minutes from simple building blocks, minimizing side reactions [31]. | Jamison & Coworkers |

| Rufinamide | Hazardous azide handling | Improved Safety Profile | In-line generation and immediate consumption of hazardous organic azides, reducing potential waste from decomposition [31]. | Jamison & Coworkers |

| Diphenhydramine HCl | Not Specified | Reduced | Flow process designed for high efficiency, reducing the number of purification steps and associated waste [31]. | Jamison & Coworkers |

| Olanzapine | Not Specified | Reduced | Use of inductive heating in flow dramatically reduced reaction times and increased process efficiency [31]. | Kirschning & Coworkers |

Experimental Protocols for E-Factor Reduction

These detailed methodologies showcase how flow chemistry can be applied to common synthetic challenges to minimize waste.

Protocol 1: Flow Electrochemistry for Oxidative Metabolite Synthesis