Crystallization Optimization for Lower PMI: Strategies for Sustainable Pharmaceutical Manufacturing

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing crystallization processes to significantly lower Process Mass Intensity (PMI).

Crystallization Optimization for Lower PMI: Strategies for Sustainable Pharmaceutical Manufacturing

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing crystallization processes to significantly lower Process Mass Intensity (PMI). It explores the foundational role of crystallization in determining Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) purity, yield, and physicochemical properties, establishing the direct link to PMI. The content details advanced methodological approaches, including AI-driven optimization, continuous processing, and co-crystallization, that enhance efficiency and reduce waste. It further offers practical troubleshooting frameworks for common scale-up challenges and validates strategies through comparative analysis of traditional versus modern techniques. By synthesizing insights from foundational principles to cutting-edge applications, this resource aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to design more sustainable, cost-effective, and robust pharmaceutical manufacturing workflows.

Understanding the Link Between Crystallization and Process Mass Intensity (PMI)

Defining PMI and Its Critical Importance in Green Pharmaceutical Manufacturing

FAQs on PMI Fundamentals

What is Process Mass Intensity (PMI) and why is it important? Process Mass Intensity (PMI) is a key green chemistry metric used to benchmark the sustainability of a manufacturing process. It is defined as the total mass of materials used to produce a specified mass of product [1]. This includes all reactants, reagents, solvents (used in reaction and purification), and catalysts [1]. PMI is critically important because it helps drive industry focus toward the main areas of process inefficiency, cost, environmental impact, and health and safety, enabling the development of more sustainable and cost-effective pharmaceutical processes [1].

How is PMI calculated? PMI is calculated using the formula: PMI = Total Mass of Materials Used (kg) / Mass of Product (kg) [2]. The "total mass of materials" encompasses all raw materials, including water, solvents, reagents, and process chemicals used in the synthesis, purification, and isolation of the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) [3].

How does PMI differ from traditional yield metrics? Unlike traditional yield metrics which only measure the efficiency of converting reactants to product, PMI provides a more holistic assessment by accounting for ALL materials used in the process, including solvents and purification materials [4]. A reaction might have a high yield but still have a poor PMI if it uses large amounts of solvents or reagents that don't incorporate into the final product [2].

PMI Benchmarking Across Pharmaceutical Modalities

The table below shows how PMI values compare across different pharmaceutical production methods, highlighting the significant environmental footprint of certain manufacturing approaches [4]:

| Pharmaceutical Modality | Reported PMI Range (kg material/kg API) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Small Molecule APIs | Median: 168 - 308 | Considered the most efficient modality [4] |

| Biologics | Average: ~8,300 | Biotechnology-derived molecules [4] |

| Oligonucleotides | Average: 4,299 (Range: 3,035 - 7,023) | Traditional solid-phase processes [4] |

| Synthetic Peptides (SPPS) | Average: ~13,000 | Significantly higher environmental footprint [4] |

ACS GCI PMI Calculators

The ACS Green Chemistry Institute Pharmaceutical Roundtable has developed several tools to help scientists calculate and optimize PMI [5]:

| Tool Name | Purpose | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| PMI Calculator | Basic PMI calculation | Accounts for raw material inputs based on bulk API output [5] |

| Convergent PMI Calculator | Handles complex syntheses | Allows multiple branches for single-step or convergent synthesis [5] |

| PMI Prediction Calculator | Early-phase assessment | Predicts PMI ranges prior to laboratory evaluation of chemical routes [1] |

Crystallization Optimization for PMI Reduction

Why is crystallization optimization critical for reducing PMI? Crystallization is often a final purification step in API manufacturing, and its efficiency directly impacts overall process mass intensity. Optimizing crystallization conditions can significantly reduce solvent use, improve yields, and minimize the need for rework, all of which substantially lower PMI [6] [7].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Crystallization Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Potential Causes | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Low Product Purity | Impurities in feed stream, improper supersaturation, inadequate crystal morphology | Check feed composition and quality; optimize operating parameters; implement seeding strategies [7] |

| Poor Crystal Morphology | Incorrect cooling rate, unsuitable solvent system, insufficient agitation | Analyze crystal shape and structure using microscopy/XRD; optimize temperature and agitation parameters [6] [7] |

| Inconsistent Batch Performance | Fluctuations in operating conditions, nucleation variability, scaling issues | Improve process monitoring and control; maintain consistent seeding rate; perform design of experiments [7] |

Experimental Protocol: Systematic Crystallization Optimization

This methodology provides a structured approach to optimizing crystallization processes for reduced PMI, adapted from best practices in pharmaceutical process development [6].

Phase 1: Initial Condition Screening

- Objective: Identify promising initial crystallization conditions

- Procedure:

- Utilize matrix screening with commercial crystallization kits

- Set up trials with 24, 48, or 96 crystallization conditions

- Use equal aliquots of protein stock solution and crystallization solutions

- Document all results, even microcrystals or clusters

- Success Criteria: Identification of conditions yielding any crystalline material [6]

Phase 2: Parameter Identification and Prioritization

- Objective: Determine which parameters most significantly impact crystallization quality

- Key Parameters to Evaluate:

- Chemical Parameters: pH, ionic strength, precipitant concentration, additive effects

- Physical Parameters: Temperature, sample volume, methodology

- Biological Parameters: Ligands, detergents, other small molecules that may enhance nucleation [6]

- Procedure: Compare successful trials to identify common characteristics and patterns [6]

Phase 3: Systematic Optimization

- Objective: Incrementally improve upon initial conditions

- Procedure:

- Compose solutions that incrementally vary parameters about initial values

- For example, if initial hit was pH 7.0, test pH values from 6.0 to 8.0 in 0.2 unit increments

- Prioritize parameters based on Phase 2 findings

- Use sufficient sample volumes to enable growth of larger crystals [6]

Phase 4: Crystal Characterization and PMI Assessment

- Objective: Evaluate crystal quality and calculate process efficiency

- Characterization Methods:

- PMI Calculation: Determine mass intensity for the crystallization step specifically [4]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

| Category | Specific Examples | Function in Crystallization |

|---|---|---|

| Precipitants | Polyethylene glycol (PEG), Ammonium sulfate, Salts | Reduce solute solubility to induce supersaturation [6] |

| Solvents | Water, Buffers, Organic solvents (DMF, NMP - to be replaced) | Dissolve solute and create crystallization environment [4] |

| Additives | Ions (Mg²⁺, Ca²⁺), Ligands, Detergents, Small molecules | Modify crystal growth, enhance nucleation, improve morphology [6] |

| Seeding Materials | Microcrystals of target compound | Control nucleation and promote consistent crystal growth [7] |

Advanced PMI Reduction Strategies

Solvent Selection and Recovery

- Problem: Solvents typically constitute the largest mass contribution to PMI in pharmaceutical processes [4] [2].

- Solution: Implement solvent substitution and recovery systems:

Process Intensification Strategies

- Continuous Crystallization: Move from batch to continuous processes to reduce solvent use and improve yields [2]

- Process Analytical Technology (PAT): Implement real-time monitoring to maintain optimal crystallization conditions and prevent batch failures [2]

- Seeding Optimization: Develop standardized seeding protocols to ensure consistent nucleation and crystal size distribution [7]

Key Takeaways for Researchers

- PMI provides a comprehensive view of process efficiency beyond traditional yield metrics by accounting for all material inputs [1] [4]

- Crystallization optimization offers significant opportunities for PMI reduction through solvent reduction, yield improvement, and process consistency [6] [7]

- Systematic optimization approaches that incrementally refine parameters typically deliver more reliable results than one-factor-at-a-time experimentation [6]

- PMI benchmarking against industry standards helps identify priority areas for sustainability improvements [4]

For further PMI calculation tools and resources, researchers can access the ACS GCI Pharmaceutical Roundtable calculators and the ongoing development of more advanced PMI-LCA tools [1] [8] [5].

How Crystallization Efficiency Directly Impacts Waste Generation and PMI

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Poor Crystal Quality and High Process Mass Intensity

Problem: Crystals are forming as microcrystals, clusters, or with unfavorable morphologies, leading to inefficient separations, low yield, and high PMI.

Solution: Systematically optimize chemical and physical parameters to grow larger, single crystals, thereby reducing the need for repeated crystallizations and solvent-intensive purification.

- Confirm the Initial "Hit": Before optimization, verify that your initial crystallization condition shows genuine promise. Visually inspect crystals; prioritize those with three-dimensional polyhedral forms over fractal forms, fine needles, or thin plates, which are often disordered or twinned and difficult to improve [6].

- Vary Precipitant Concentration Methodically: Create a series of solutions that incrementally vary the precipitant concentration above and below the initial hit condition. For a polyethylene glycol (PEG) condition, adjust its concentration in steps of 2-5% (w/v) [6].

- Optimize pH Systematically: Prepare crystallization solutions at pH values incremented by 0.2-0.5 pH units around the initial hit. Note that pH and temperature can be interdependent; an change in one may affect the other [6].

- Control Nucleation by Temperature: Explore a range of temperatures (e.g., 4°C, 12°C, 18°C, and 23°C). Temperature can directly and predictably change a protein's solubility, helping to control the level of supersaturation and reduce excessive nucleation [9].

- Adjust Sample Concentration and Ratio: Vary the ratio of macromolecule to crystallization cocktail in the experiment drop. This changes the effective concentration of both components without the need for biochemical reformulation, which can be a source of waste and inconsistency [9].

Guide 2: Troubleshooting Irreproducibility and Inconsistent Results

Problem: Crystallization results cannot be reproduced between batches or when scaling up, leading to wasted materials and increased PMI from repeated experiments.

Solution: Implement strategies that enhance reproducibility and minimize batch-to-batch variability.

- Eliminate Reformulation Between Screening and Optimization: Use the exact same cocktail solutions for both screening and optimization experiments. This prevents batch differences caused by reformulation, a process that itself consumes materials and can introduce variability [9].

- Scale Up Thoughtfully: Promising results from nanolitre-volume trials often fail to yield larger crystals when scaled up. To grow crystals of sufficient size for analysis, plan to scale up to microlitre or millilitre volumes, understanding that conditions may need re-optimization [6].

- Employ Seeding Techniques: If crystals are too small or numerous, consider using microseeding to transfer a controlled number of nucleation sites into a new, pre-equilibrated drop. This can promote the growth of larger, single crystals from conditions that would otherwise produce showers of microcrystals [6].

- Document Solution History: Cocktails, especially those containing PEGs, can undergo chemical changes over time. Using the same batch of "aged" solutions for both screening and optimization can paradoxically improve reproducibility by ensuring chemical consistency [9].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is PMI and why is it a critical metric for crystallization processes?

Answer: Process Mass Intensity (PMI) is defined as the total mass of materials used (raw materials, reactants, and solvents) to produce a specified mass of product [10] [11]. It is a key green chemistry metric for assessing material efficiency and environmental impact. A lower PMI indicates a more efficient and less wasteful process. The ideal PMI is 1, meaning all input materials are incorporated into the final product [11]. In the context of crystallization, a highly optimized process that produces high-quality crystals on the first attempt dramatically reduces the consumption of solvents, precipitants, and the target molecule itself, thereby significantly lowering the overall PMI.

FAQ 2: How can a simple change in temperature reduce waste in crystallization?

Answer: Temperature is a powerful yet underutilized variable. It directly controls the supersaturation level of the macromolecule [9].

- Precise Control: Finding the optimum growth temperature can shift outcomes from precipitate or microcrystals to large, single crystals, eliminating the need for repeated trials.

- Sample Conservation: The Drop Volume Ratio/Temperature (DVR/T) method uses temperature variation alongside drop composition, allowing for efficient optimization without concentrating the protein sample or reformulating solutions, thus saving material [9].

FAQ 3: We have multiple initial "hits" from screening. Which one should we optimize to lower PMI?

Answer: Prioritize hits based on both chemical commonality and crystal morphology [6].

- Chemical Analysis: Compare all successful conditions and look for common precipitants (e.g., PEG vs. salts), specific ions, or pH ranges. Focusing on a common chemical theme can streamline optimization efforts.

- Morphology Inspection: Visually inspect the crystals. Prioritize conditions that produce single, three-dimensional polyhedral crystals over those yielding microcrystals, needles, or clusters. Good optical properties, like strong birefringence under polarized light, can also indicate a more ordered crystal [6].

FAQ 4: What are the most wasteful stages in a typical crystallization process, and how can we target them?

Answer: The primary sources of waste (high PMI) in crystallization are:

- Failed or Poor Trials: The need to set up hundreds or thousands of screening trials consumes vast amounts of solvents and precious macromolecule samples.

- Reformulation: Creating new batches of crystallization solutions for optimization is time-consuming and a source of material waste and irreproducibility [9].

- Inefficient Purification: Poor-quality crystals may require resource-intensive purification steps like repeated recrystallization or chromatography, which greatly increases solvent waste.

To target these, invest in thorough optimization of promising hits, use the same stock solutions for screening and optimization, and leverage techniques like seeding to improve crystal quality without resorting to entirely new chemical conditions [9] [6].

Quantitative Data on Process Efficiency

The following table summarizes key green chemistry metrics, highlighting the significant environmental footprint of peptide synthesis compared to small molecules and the importance of optimization in reducing PMI.

Table 1: Green Chemistry Metrics for Different Pharmaceutical Modalities

| Metric | Definition | Small Molecule Drugs | Peptide Drugs (SPPS) | Ideal Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Process Mass Intensity (PMI) | Total mass of materials used per mass of product (kg/kg) [11] | Median: 168 - 308 [4] | Average: ~13,000 [4] | 1 |

| E-Factor | Total mass of waste per mass of product (kg/kg) [10] | - | - | 0 |

| Atom Economy (AE) | (MW of desired product / Σ MW of reactants) x 100% [12] | - | - | 100% |

| Relationship | E-Factor = PMI - 1 [10] [11] | - | - | - |

Table 2: Impact of Crystallization Optimization on Key Parameters

| Parameter | Initial Hit (Screening) | After Optimization | Impact on PMI and Waste |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crystal Morphology | Microcrystals, clusters, needles [6] | Large, single crystals | Reduces need for re-crystallization, lowering solvent use. |

| Crystal Volume | Small, insufficient for diffraction | Larger volume, high quality | Improves data quality, eliminates repeated expression/purification. |

| Reproducibility | Low, batch-dependent | High | Eliminates wasted materials on failed reproduction attempts. |

| Required Sample Purity | Often high | Can sometimes be lowered | Reduces intensive purification steps (e.g., chromatography). |

Experimental Protocols for PMI Reduction

Protocol 1: High-Throughput Drop Volume Ratio and Temperature (DVR/T) Optimization

Objective: To rapidly optimize initial crystallization conditions by simultaneously varying the concentration of the macromolecule, precipitant, and growth temperature without reformulating biochemical solutions, thereby minimizing sample use and waste [9].

Materials:

- Purified macromolecule sample

- Cocktail solution from the initial screening "hit"

- Crystallization plate (e.g., 1536-well microassay plate)

- Robotic liquid handler (optional, for high-throughput)

- Incubators or temperature-controlled environments

Method:

- Prepare Protein and Cocktail Stocks: Use the exact same batches of macromolecule and cocktail solution that generated the initial hit.

- Design the Experiment Matrix: Create a two-dimensional matrix where one dimension varies the volume ratio of protein to cocktail, and the other is the incubation temperature.

- Volume Ratios: Set up a series of experiments where the total drop volume is constant, but the ratio of protein volume to cocktail volume varies (e.g., from 5:1 to 1:5). This systematically varies the effective concentration of both components in the drop [9].

- Temperatures: Incubate identical plates at multiple temperatures (e.g., 4°C, 12°C, 18°C, and 23°C) [9].

- Set Up Crystallization Trials: Dispense the appropriate volumes of protein and cocktail into the wells of the crystallization plate to create the experiment drops according to your matrix.

- Incubate and Monitor: Seal the plates and place them in the respective temperature-stable environments. Monitor the drops periodically for crystal formation and quality.

- Analyze Results: Simultaneously assess the outcomes across all volume ratios and temperatures. Identify conditions that produce the largest, most single crystals.

Protocol 2: Systematic Grid Screen Optimization

Objective: To refine the chemical conditions (precipitant concentration and pH) around an initial hit to produce crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction analysis [6].

Materials:

- Purified macromolecule sample

- Chemicals to reformulate the crystallization cocktail (e.g., precipitant, buffer salts)

- Crystallization plates (e.g., 24 or 96-well plates)

- Pipettes or liquid dispenser

Method:

- Identify Key Parameters: From the initial hit, note the precipitant type and concentration, buffer system, and pH.

- Prepare Stock Solutions: Create a concentrated stock solution of the precipitant and a buffer stock solution.

- Design the Grid: Create a 2D grid where one axis represents precipitant concentration and the other represents pH.

- Precipitant: Vary the concentration in 5-10 steps around the initial condition (e.g., if initial is 20% PEG 4000, test from 10% to 30%).

- pH: Vary the pH in 0.2-0.5 unit steps around the initial pH (e.g., from pH 6.0 to 8.0 if initial is 7.0) [6].

- Formulate Cocktails: Prepare a unique crystallization solution for each node on the grid by mixing the appropriate amounts of precipitant stock, buffer stock, and water.

- Set Up Crystallization Trials: Use a standard vapor diffusion method (e.g., sitting drop) by mixing equal volumes of protein solution and each unique cocktail solution.

- Incubate and Monitor: Seal the plates and incubate at a constant temperature. Monitor the drops for crystal growth over days to weeks.

- Identify Optimal Conditions: Compare crystal size and quality across the grid to pinpoint the optimal precipitant concentration and pH.

Visualizations

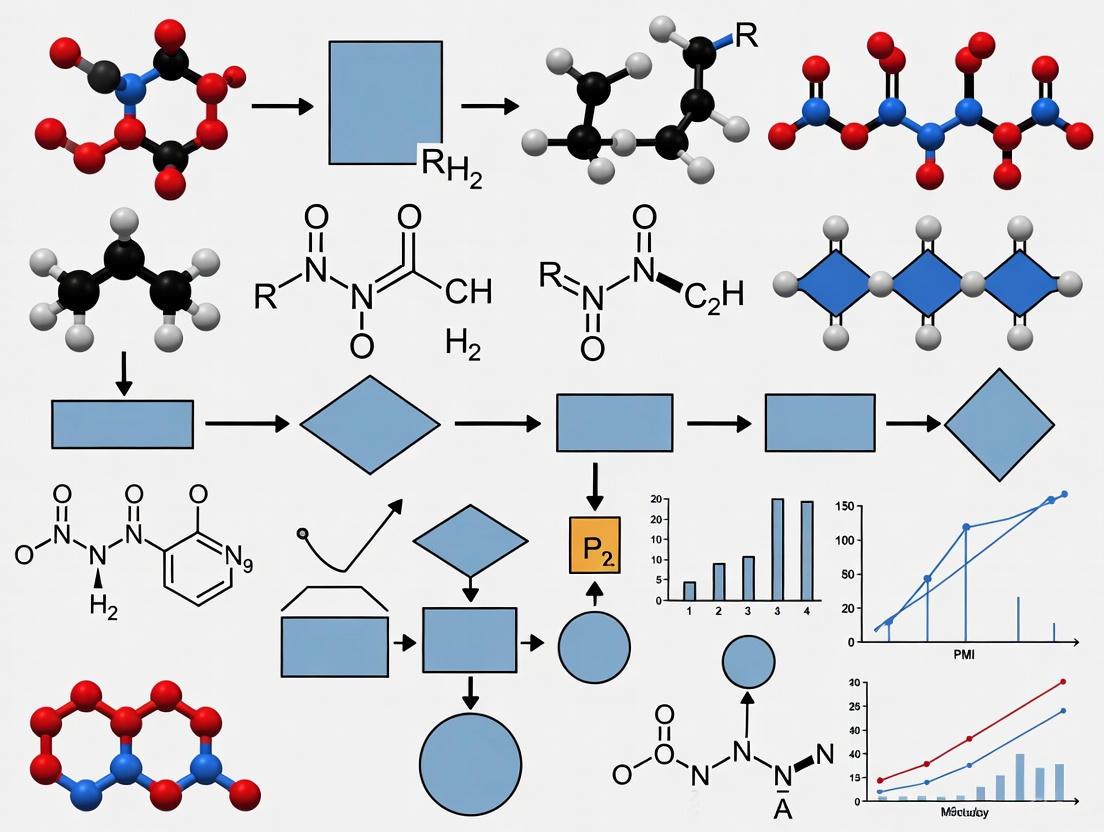

Diagram 1: Crystallization Optimization Workflow for PMI Reduction

Diagram Title: Crystallization Optimization Workflow

Diagram 2: Interrelationship of Crystallization Parameters and PMI

Diagram Title: Crystallization Parameters and PMI Relationship

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Crystallization Optimization

| Reagent / Material | Function in Crystallization | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | A common precipitant that excludes macromolecules from solution, driving them toward supersaturation and crystallization [9] [6]. | Available in a wide range of molecular weights. Aging of PEG solutions can affect reproducibility; using the same batch is critical [9]. |

| Buffer Salts | Maintains the pH of the crystallization solution, which critically affects macromolecule solubility and stability [6]. | Systematic variation of pH in small increments (e.g., 0.2-0.5 units) is a core optimization strategy [6]. |

| Ions & Additives | Ions (e.g., Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺) or small molecules can bind to the macromolecule and stabilize specific conformations, promoting crystal formation [6]. | Identification of useful additives often comes from initial screen hits. Can be included in optimization grid screens. |

| Crystallization Plates | Platform for setting up nanolitre- to microlitre-volume crystallization trials. | 1536-well plates enable high-throughput DVR/T optimization. Larger volumes may be needed for crystal retrieval [9]. |

| Liquid Handling Robotics | Automates the dispensing of precise, small-volume droplets for screening and optimization. | Enables high-throughput implementation of methods like DVR/T, improving reproducibility and saving researcher time [9]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Guide 1: Nucleation and Initial Crystal Formation

Problem 1: Excessive Fines and Poor Filtration

- Observed Issue: The resulting crystal slurry is difficult to filter, and the particle size distribution is too fine.

- Root Cause: This is frequently caused by rapid cooling or excessive supersaturation, which leads to uncontrolled primary nucleation and the generation of too many small crystals [13].

- Solutions:

- Implement controlled cooling strategies with slower, linear cooling rates to manage supersaturation [13].

- Utilize seeded crystallization. Introduce pre-formed crystals of the desired form to provide sites for crystal growth, thereby suppressing excessive primary nucleation [13] [14].

- Optimize the anti-solvent addition rate if using anti-solvent crystallization. A slower addition rate prevents localized high supersaturation [13].

Problem 2: Failure to Nucleate (Oiling Out)

- Observed Issue: The solution becomes supersaturated but does not form crystals, instead forming an amorphous oil or glass.

- Root Cause: The supersaturation level is too high, causing the molecules to precipitate too rapidly to form an ordered crystal lattice. This can also occur if the system is held for too long in a metastable zone without nucleation triggers [13] [15].

- Solutions:

Troubleshooting Guide 2: Polymorphism and Solid Form Control

Problem 1: Appearance of an Unwanted Polymorph

- Observed Issue: The crystalline product is a mixture of polymorphs or an unexpected, potentially less stable polymorph.

- Root Cause: The process conditions (temperature, solvent, supersaturation) favor the nucleation and growth of a metastable form. This is a common risk when operating in a metastable zone without controls [13] [16].

- Solutions:

- Seed with the desired polymorph. This is the most robust method to ensure the correct form appears and grows [13] [17].

- Control supersaturation carefully, as high supersaturation often favors metastable forms [13].

- Employ solvent engineering. The choice of solvent can stabilize the nucleation of one polymorph over another [13] [16].

Problem 2: Polymorphic Transformation During Processing or Storage

- Observed Issue: The API is isolated in the correct polymorphic form but transforms to a different, often more stable, form later.

- Root Cause: A solution-mediated or solid-state transformation can occur if the initial form is metastable and conditions (e.g., humidity, temperature) provide the activation energy for transition [16].

- Solutions:

- Select the most stable polymorph for development, if pharmaceutically acceptable, to prevent transformations [17].

- Control environmental factors like humidity and temperature during storage and handling [13].

- Monitor the process with in-situ analytical techniques (e.g., Raman spectroscopy) to detect early signs of transformation [17].

Troubleshooting Guide 3: Crystal Growth and Habit

Problem 1: Agglomeration and Poor Flow Properties

- Observed Issue: Crystals cluster together into large agglomerates, leading to poor powder flow and blending inconsistencies.

- Root Cause: This can be caused by high supersaturation during the growth phase, which promotes rapid, irregular growth and bridging between particles. It can also be due to insufficient agitation or incompatible solvent systems [13].

- Solutions:

- Optimize cooling and supersaturation profiles to favor controlled growth over rapid deposition [13].

- Increase agitation to improve mass and heat transfer and prevent crystals from settling and sticking [13].

- Consider terminal wet milling as a post-crystallization step to break up agglomerates and refine particle size [17].

Problem 2: Wide Particle Size Distribution (PSD)

- Observed Issue: The final product contains a mix of very large and very small crystals.

- Root Cause: This is typically a result of non-uniform mixing, temperature gradients in the crystallizer, or uncontrolled secondary nucleation during the growth phase [13].

- Solutions:

- Improve agitator design and mixing efficiency to ensure consistent conditions throughout the vessel [13].

- Use a seeded crystallization protocol with a narrow seed PSD to promote uniform growth on all crystals [13].

- For challenging systems, consider continuous crystallization, which can provide more consistent supersaturation control and narrower PSD [13] [18].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the single most important factor for achieving a reproducible polymorph? The most critical factor is often the use of seeding with the desired polymorph under carefully controlled supersaturation conditions [13] [17]. Seeding provides a template for the molecules to arrange in the target crystal structure, kinetically steering the process toward the desired form and ensuring batch-to-batch consistency.

FAQ 2: How can we quickly determine which polymorph is the most stable? Competitive slurry experiments are a standard laboratory technique for determining relative stability [17]. In this experiment, two polymorphic forms are suspended together in a solvent and slurried for a period. Over time, the system will tend toward the more stable form, which can then be identified using analytical techniques like X-ray diffraction (XRD) or Raman spectroscopy.

FAQ 3: Our process scales poorly from the lab to the plant. What scale-up factors most impact crystallization? The key scale-up challenges are related to mixing and heat transfer [13]. Larger vessels have different hydrodynamic profiles, which can lead to "dead zones" with poor mixing and uneven temperature distribution. This non-uniform environment causes local variations in supersaturation, leading to inconsistent nucleation, growth, and potentially unwanted polymorphs. Careful pilot studies and computational fluid dynamics (CFD) modeling can help mitigate these issues.

FAQ 4: What in-situ tools can we use to monitor a crystallization process in real-time? Several Process Analytical Technology (PAT) tools are available:

- In-situ Raman Spectroscopy: Excellent for identifying and monitoring polymorphic forms directly in the slurry [17].

- Attenuated Total Reflectance Fourier Transform Infrared (ATR-FTIR) Spectroscopy: Useful for measuring solution concentration and monitoring supersaturation [18].

- Focused Beam Reflectance Measurement (FBRM): Provides real-time data on particle count and chord length distribution, giving insight into nucleation, growth, and agglomeration events.

Quantitative Data in Crystallization

The following table summarizes key parameters and their quantitative impact on crystallization outcomes, crucial for process optimization and reducing Process Mass Intensity (PMI).

Table 1: Key Process Parameters and Their Impact on Crystallization Outcomes

| Process Parameter | Impact on Nucleation | Impact on Crystal Growth | Optimal Control Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cooling Rate | Rapid cooling induces excessive primary nucleation, creating fines [13]. | Slow growth can lead to inclusions; fast growth can cause agglomeration [13]. | Use controlled, linear cooling to stay within the metastable zone [13]. |

| Supersaturation Level | High supersaturation drives rapid primary and secondary nucleation [13]. | High supersaturation accelerates growth but can lead to irregular crystal habit and impurities [13]. | Maintain moderate supersaturation to favor controlled growth; use PAT for monitoring [13]. |

| Agitation Speed | High agitation can induce secondary nucleation by generating crystal collisions [13]. | Improves mass transfer for uniform growth; excessive speed can cause crystal breakage [13]. | Optimize for full suspension without excessive shear; scale-up considerations are critical [13]. |

| Seed Loading & Size | Seeding suppresses primary nucleation by providing surface for growth [14]. | Higher seed loading leads to more, smaller crystals; larger seeds can yield larger final crystals [13]. | Typically 0.5-5% of final batch mass; seed size and quality are critical for consistency [13]. |

Experimental Protocols for Crystallization Optimization

Protocol 1: Determining Metastable Zone Width (MSZW)

Objective: To identify the temperature or concentration difference between the solubility curve and the spontaneous nucleation point, which defines the operating window for a safe and controlled crystallization [17].

- Preparation: Prepare a saturated solution of the API in the chosen solvent system at a defined temperature.

- Cooling & Monitoring: While applying constant agitation, cool the solution at a fixed, slow rate.

- Detection: Use an in-situ probe (e.g., turbidity, FBRM, or ATR-FTIR) to detect the first moment of nucleation (a sudden increase in particle count or turbidity). Record this temperature.

- Calculation: The MSZW is the difference between the saturation temperature and the nucleation temperature. A wider MSZW allows for more operational flexibility, while a narrow MSZW requires precise control.

Protocol 2: Competitive Slurry Experiment for Polymorph Stability

Objective: To experimentally determine the thermodynamically most stable polymorphic form of an API at a given temperature and solvent condition [17].

- Sample Preparation: Obtain pure samples of two or more known polymorphs of the API (e.g., Form I and Form II).

- Slurry Creation: Combine equal masses of each polymorph in a vessel containing a solvent in which the API is slightly soluble. The solvent should not react with the API.

- Equilibration: Stir the slurry continuously at a constant temperature for a pre-determined period (e.g., 24-72 hours) to allow the system to reach solid-solid equilibrium.

- Analysis: After the equilibration period, filter the solid sample and analyze it immediately using a technique like Powder X-Ray Diffraction (PXRD) or Raman spectroscopy.

- Interpretation: The polymorphic form that is predominantly present in the solid phase after equilibration is the most stable form under those specific conditions.

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Polymorph Control Strategy

Nucleation and Growth Pathways

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Crystallization Development

| Item | Function in Crystallization |

|---|---|

| Anti-solvents | A solvent miscible with the primary solvent but with low API solubility; used to induce supersaturation and nucleation by reducing solubility [13] [14]. |

| Seeds (Pre-formed Crystals) | Small, pure crystals of the target polymorph used to control nucleation, ensure the correct form, and produce a uniform crystal size distribution [13] [17]. |

| Tailor-Made Additives/Co-formers | Molecules designed to interact with specific crystal faces or molecules to inhibit the growth of unwanted polymorphs or to facilitate co-crystal formation for improved properties [18] [16]. |

| Process Analytical Technology (PAT) | In-situ probes (e.g., Raman, FBRM, ATR-FTIR) for real-time monitoring of concentration, particle size, and polymorphic form, enabling precise control [18] [17]. |

| Polymeric Additives / Crystallization Aids | Used to modify crystal habit, control agglomeration, or stabilize metastable forms by interacting with crystal surfaces during growth [16]. |

The Role of Crystallization in Determining API Purity, Yield, and Downstream Processing

Troubleshooting Guides

This section addresses common crystallization challenges, their impact on API quality, and evidence-based solutions to help scientists develop robust and scalable processes.

Rapid Crystallization

Problem Statement: Crystals are forming too quickly, leading to inconsistent product quality and operational issues.

Root Causes:

- Excessively high supersaturation levels, often due to rapid cooling or anti-solvent addition.

- Insufficient or ineffective agitation, creating localized high-supersaturation zones.

- Absence of seeding to provide controlled nucleation sites.

Impact on API:

- Purity: Rapid formation can trap impurities within the crystal lattice or on crystal surfaces [19].

- Yield: Can lead to excessive nucleation, generating fine particles that are difficult to filter, leading to product loss [19].

- Downstream Processing: Agglomeration of fine crystals impairs powder flowability, causing issues in blending, tableting, and encapsulation [19]. Crystal fines can also clog filters during isolation [19].

Solutions:

- Control Supersaturation: Implement slower, controlled cooling rates or gradual anti-solvent addition to maintain moderate supersaturation [19].

- Utilize Seeding: Introduce pre-formed crystals of the desired polymorph to promote controlled growth and suppress excessive primary nucleation [20] [14].

- Optimize Agitation: Adjust agitation speed to ensure uniform mixing and temperature throughout the vessel, preventing localized rapid crystallization [19].

Polymorphic Transformation

Problem Statement: An undesired crystal form (polymorph) appears during scaling-up or storage, jeopardizing product stability and performance.

Root Causes:

- Incorrect solvent selection that stabilizes an unwanted polymorph.

- Inconsistent seeding, either using the wrong polymorph or an incorrect seeding protocol.

- Fluctuations in process parameters (e.g., temperature, cooling rate) outside the stable region of the desired polymorph.

Impact on API:

- Purity & Stability: Different polymorphs have different chemical and physical stability; an unstable form may degrade over time [20] [14].

- Downstream Processing: Polymorphs can have different solubility, melting points, and mechanical properties, directly affecting formulation processes like granulation and tableting, and potentially leading to bioavailability inconsistencies [20] [14].

Solutions:

- Robust Form Screening: Conduct comprehensive polymorph and salt screens early in development to identify the most stable and manufacturable form [21].

- Process Analytical Technology (PAT): Implement tools like in-situ microscopy or Raman spectroscopy to monitor the crystal form in real-time and detect polymorphic shifts early [22] [23].

- Design a Robust Operating Window: Use Quality by Design (QbD) principles to define a proven acceptable range (PAR) for critical process parameters (CPPs) like temperature and cooling rate that consistently produce the target polymorph [22] [24].

Agglomeration and Fines Formation

Problem Statement: Crystals clump together into large agglomerates or an excess of very small particles (fines) is produced.

Root Causes:

- High supersaturation promotes rapid primary nucleation, leading to fines.

- Excessive mechanical energy from high agitation speeds can cause secondary nucleation (fines) and fragment crystals, creating surfaces that easily agglomerate.

- Incompatible solvent systems or high impurity levels can promote bridging between particles.

Impact on API:

- Yield: Fines can be lost through filters or during isolation, reducing overall yield [19].

- Downstream Processing: Agglomerates cause poor flowability, leading to uneven die filling during tableting, content uniformity issues, and inconsistent bulk density. This results in variable dissolution rates and challenges in dosing accuracy [19].

Solutions:

- Optimize Supersaturation Profile: Carefully control the cooling and anti-solvent addition profile to manage nucleation and growth rates [19].

- Adjust Agitation: Find the optimal agitation rate that provides sufficient mixing without generating excessive shear that causes breakage and secondary nucleation [19].

- Implement Seeding: Seeding provides growth sites for solute molecules, reducing the driving force for spontaneous nucleation and agglomeration [21] [20].

Fouling and Scaling on Equipment

Problem Statement: Crystals adhere to the internal surfaces of reactors and piping.

Root Causes:

- Excessive wall temperature differences, creating high local supersaturation at the vessel surface.

- Inappropriate surface material of the reactor that promotes crystal adhesion.

- Uncontrolled nucleation generates a large number of fine crystals that deposit on surfaces.

Impact on API:

- Yield: Product adhesion to equipment directly reduces the isolated yield.

- Purity: Scale can detach during a batch, introducing foreign particles of inconsistent age and purity into the final product.

- Operational Efficiency: Fouling reduces heat transfer efficiency, increases downtime for cleaning, and raises operational costs [19].

Solutions:

- Control Wall Temperature: Use jacketed reactors with precise temperature control to minimize thermal gradients [19].

- Optimize Process Parameters: As with other issues, controlling supersaturation through seeding and controlled cooling is the primary method to prevent fouling [19].

- Equipment Design: Consider crystallizers designed to minimize dead zones and use surfaces that resist crystal adhesion [19].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is controlling the crystallization rate so critical for API purity? A: Rapid crystallization traps mother liquor containing impurities within the growing crystal lattice, a phenomenon known as inclusion. This results in a product with lower purity as these impurities are encapsulated and cannot be easily removed by washing. Controlled, slower crystallization allows for the rejection of impurities from the crystal surface, yielding a purer API [19].

Q2: How does the choice of solid form (polymorph) impact downstream processing and drug performance? A: The polymorphic form is a Critical Quality Attribute (CQA) because it directly influences:

- Solubility & Dissolution Rate: Affects the API's bioavailability [20] [14].

- Physical & Chemical Stability: Determines the shelf-life of the drug substance and product [20] [14].

- Mechanical Properties: Influences bulk density, flowability, and compactibility, which are crucial for manufacturing solid dosage forms like tablets [20].

Q3: What is the single most effective strategy to ensure reproducible crystallization at scale? A: While multiple factors are important, controlled seeding is widely regarded as one of the most powerful strategies. Seeding with the desired polymorph at the correct temperature and supersaturation provides defined nucleation sites, ensuring consistent crystal size distribution (CSD), the correct polymorphic form, and reproducible yield and purity from lab to plant scale [21] [20] [14].

Q4: Our API is an oil that resists crystallization. What options do we have? A: Salification or co-crystallization are standard industrial approaches.

- Salt Formation: Converting a free acid or base API into a salt (e.g., hydrochloride, sodium) often dramatically improves crystallinity, purity, and physical stability. This was demonstrated in a case study where a complex lipid intermediate was transformed from an oil (93% purity) to a stable, crystalline salt (96% purity) [21].

- Co-crystallization: Forming a crystalline structure with a pharmaceutically acceptable co-former can create a new solid with improved properties, such as enhanced solubility and stability, for non-ionizable compounds [14].

Q5: How can we apply Quality by Design (QbD) to crystallization process development? A: A QbD approach involves:

- Defining a Target Product Profile (e.g., crystal form, particle size, purity).

- Identifying Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) influenced by crystallization.

- Understanding the impact of Critical Process Parameters (CPPs) like cooling rate, seeding, and solvent composition on CQAs.

- Using mechanistic modeling and PAT tools to establish a design space of proven acceptable operating ranges that guarantee consistent quality [22] [24].

Quantitative Data on Crystallization Methods

The table below summarizes key quantitative and operational characteristics of common crystallization techniques used in API development.

Table 1: Comparison of Common API Crystallization Methods

| Method | Key Principle | Typical Yield Range | Impact on Particle Size Distribution (PSD) | Key Operational Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cooling Crystallization [20] [14] | Reduce temperature to decrease solubility & create supersaturation. | High (85-95%+) | Can produce a wide PSD if not controlled; controlled cooling with seeding yields a narrower distribution. | Managing metastable zone width; achieving uniform cooling in large vessels. |

| Anti-Solvent Crystallization [20] [14] | Add solvent (anti-solvent) to reduce API solubility. | Moderate to High | Often produces fine particles due to high localized supersaturation; requires controlled addition and mixing. | Avoiding oiling out; ensuring mixing is sufficient to prevent agglomeration. |

| Evaporative Crystallization [20] [14] | Remove solvent by evaporation to increase concentration. | High | Can lead to broad PSD and agglomeration if evaporation is too rapid. | Potential for fouling on heat transfer surfaces; controlling crust formation. |

| Reactive/Precipitation Crystallization | Create insoluble API via chemical reaction. | Variable | Typically generates very fine, often amorphous or poorly crystalline particles. | Extremely fast, difficult to control; reproducibility is a major challenge. |

| Melt Crystallization [20] | Cool molten API below its melting point to form crystals. | Very High | Produces dense crystals, often with a wide PSD. | Limited to thermally stable APIs; can have high energy demands. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Investigations

Protocol: Seeded Cooling Crystallization for Polymorph Control

Aim: To develop a robust cooling crystallization process that consistently produces the desired polymorphic form with high purity and defined particle size.

Background: Unseeded cooling crystallization often operates within the metastable zone, leading to unpredictable nucleation and potential formation of unstable polymorphs. Seeding provides controlled nucleation sites [21] [14].

Materials:

- API solution (saturated at elevated temperature)

- Pre-characterized seed crystals (desired polymorph, specific size fraction)

- Jacketed laboratory reactor with overhead stirring

- Temperature control unit

- PAT tool (e.g., in-situ particle analyzer or Raman spectrometer) [21]

Methodology:

- Solubility Determination: Characterize the API's solubility curve in the chosen solvent system.

- Metastable Zone Width (MSZW): Determine the MSZW by identifying the temperature at which nucleation occurs upon cooling a clear, unsaturated solution.

- Process Design: Design a cooling profile based on the solubility and MSZW data. The initial temperature should be high enough to dissolve all unseeded material but low enough to be within the metastable zone upon seeding.

- Seeding: Cool the solution to a predetermined temperature within the metastable zone. Add a well-dispersed suspension of seed crystals (typically 0.5-5.0% w/w). The seeding temperature is critical to prevent dissolution or secondary nucleation.

- Controlled Growth: After seeding, initiate a controlled cooling profile (e.g., linear or tailored) to maintain a gentle, constant supersaturation, allowing for controlled growth on the seeds.

- Isolation: Cool to the final temperature, hold for a period to allow for Ostwald ripening (which improves purity and size), then isolate the crystals by filtration [21].

Protocol: Salt Screen to Crystallize an Oily Intermediate

Aim: To discover a stable crystalline salt form of an oily intermediate to facilitate isolation, improve purity, and enable subsequent synthetic steps.

Background: Many free base or free acid intermediates are oils at room temperature, making them difficult to handle and purify. Salt formation with a suitable counterion is a proven method to induce crystallinity [21].

Materials:

- Oily intermediate (free base or acid)

- Library of pharmaceutically acceptable counterions (e.g., HCl, H2SO4, maleic acid for bases; Na, K, Ca salts for acids)

- Automated liquid handling system or parallel micro-reactors

- Solvents of varying polarity

- Analytical tools (HPLC, XRPD, DSC)

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Dispense the oily intermediate into multiple vials.

- Solvent/Counterion Screening: In each vial, combine the intermediate with a different counterion in a variety of solvents. Use both stoichiometric and non-stoichiometric ratios.

- Induction Techniques: Subject the vials to various crystallization induction techniques, including cooling, anti-solvent addition, and evaporation.

- Solid Characterization: Isolate any resulting solids and characterize them using XRPD to identify unique crystalline phases and DSC/TGA to assess thermal stability.

- Stability Assessment: Select the most promising salt forms for short-term stability testing under accelerated conditions (e.g., 40°C/75% RH).

- Scale-up: Scale up the synthesis and crystallization of the lead salt candidate for further process development [21].

Process Optimization Workflow

The following diagram illustrates a systematic, QbD-based workflow for developing and scaling a robust crystallization process.

Crystallization Process Development Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Equipment

Table 2: Key Materials and Equipment for Crystallization R&D

| Item Category | Specific Examples | Function & Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Solvent Systems | Alcohols (MeOH, EtOH, IPA), Acetone, Ethyl Acetate, Heptane, Toluene, Water. | The primary medium for crystallization; solvent choice is the most critical parameter as it dictates solubility, metastable zone width, and the resulting crystal form and habit [20]. |

| Counterions (for Salts) | Hydrochloric Acid, Sulfuric Acid, Sodium Hydroxide, Potassium Hydroxide, Maleic Acid, Fumaric Acid. | Used to convert ionic APIs into stable, crystalline salts from oily intermediates, improving filterability, purity, and stability [21]. |

| Co-formers (for Co-crystals) | Pharmaceutically acceptable carboxylic acids, amides, etc. (e.g., succinic acid, caffeine). | Molecules that co-crystallize with a neutral API to create a new solid form with enhanced properties like solubility and stability [14]. |

| Process Analytical Technology (PAT) | In-situ Particle Size Analyzers (e.g., PVM, FBRM), Raman Spectrometers. | Enables real-time monitoring of critical attributes like particle size and polymorphic form, moving from off-line testing to continuous quality assurance [22] [23]. |

| Automated Lab Reactors | Jacketed Crystallization Reactors with precise temperature and dosing control. | Provide a controlled environment for process development, allowing for precise parameter control and data collection for QbD and scale-up studies [21] [14]. |

Advanced Crystallization Techniques and Workflows for PMI Reduction

AI and Machine Learning for Predictive Solubility Modeling and Condition Optimization

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Q1: My ensemble model for solubility prediction has high training accuracy but poor performance on new experimental data. What could be wrong?

- A: This is a classic sign of overfitting. Our support data indicates this often stems from a small dataset or data leakage.

- Recommended Action: Implement the following steps:

- Apply Outlier Detection: Before training, use the leverage technique or Cook’s distance analysis to identify and remove statistical outliers from your dataset [25] [26].

- Use a Hold-Out Set: Ensure your data is split into distinct training, validation, and test sets (e.g., 70/15/15). The validation set is used for hyperparameter tuning, and the test set is used only once for a final, unbiased performance estimate [26].

- Optimize Hyperparameters: Use metaheuristic optimization algorithms like Ant Colony Optimization (ACO) or Cuckoo Optimization Algorithm (COA) to fine-tune your model's hyperparameters, which prevents the model from becoming too specialized to the training data [25] [26].

- Conduct Bootstrapping Analysis: Run your model multiple times (e.g., five times) on different random splits of the data. A high variance in performance indicates instability and overfitting. Hybrid models like LSTM-COA have been shown to be less susceptible to this issue [26].

- Recommended Action: Implement the following steps:

Q2: I am unsure which machine learning algorithm to choose for predicting drug solubility in supercritical CO₂.

- A: The optimal algorithm depends on your dataset size and non-linearity. Based on recent research, tree-based ensemble models are highly effective.

- Recommended Action: Start with the following models and compare their performance on your validation set:

- Gradient Boosting Decision Trees (GBDT): Often the top performer for complex, non-linear relationships. A recent study achieved an R² of 0.987 and a low RMSE for solubility modeling using GBDT optimized with ACO [25].

- Random Forest (RF): A robust model that reduces variance by averaging multiple decision trees. It is less prone to overfitting than a single tree [25].

- Extremely Randomized Trees (ET): Introduces more randomness than RF during the splitting process, which can further reduce variance and is effective with smaller datasets [25].

- Pro-tip: For sequential data or when capturing time-dependent effects is crucial, consider hybrid models like Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks optimized with metaheuristic algorithms [26].

- Recommended Action: Start with the following models and compare their performance on your validation set:

Q3: My predictive model's performance is unstable, with high variance in error metrics across different data splits.

- A: This points to high model variance and a potential lack of generalization.

- Recommended Action:

- Ensemble Methods: Switch to or continue using ensemble methods like RF, ET, or GBDT, which are explicitly designed to create a more stable and accurate model by combining multiple weaker models [25].

- Hybrid LSTM Models: For complex systems, consider hybrid models like LSTM-COA, which have demonstrated lower RMSE and higher stability in predictions compared to standalone models [26].

- Feature Importance Analysis: Use techniques like SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) to identify the most influential input variables (e.g., temperature and pressure). This helps you understand your model's drivers and can guide you to collect more relevant data [26].

- Recommended Action:

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What are the key input parameters I need to model drug solubility in supercritical CO₂?

- A: The most fundamental parameters are Temperature and Pressure, as they drastically affect the solvent's density and solvation power [25]. For solubility in brine systems, the concentration of various salts (e.g., NaCl, KCl, CaCl₂) also becomes critical [26].

Q: How can AI help reduce the number of physical experiments needed (Lowering PMI)?

- A: AI and Predictive Modeling are central to the green pharmaceutical manufacturing philosophy of lowering Process Mass Intensity (PMI).

- In-silico Screening: AI models can screen thousands of potential conditions (e.g., temperature, pressure, solvent composition) in silico, drastically narrowing down the experimental design space to only the most promising candidates [27] [25].

- Efficient Formulation Optimization: Predictive modeling allows researchers to optimize formulation parameters and excipient selection computationally, reducing the need for trial-and-error experiments that consume materials [27].

- Green Processing: Using AI to model and optimize processes like supercritical CO₂ processing, which avoids organic solvents, directly contributes to a lower PMI and a more sustainable manufacturing route [25].

Q: My protein crystallization experiments are failing to yield high-quality crystals. How can AI and new technologies help?

- A: This is a common challenge. Modern trends focus on high-throughput and intelligent screening.

- Adopt Microfluidic Platforms: These platforms miniaturize experiments, allowing you to screen thousands of crystallization conditions with an order of magnitude less sample volume, accelerating discovery and conserving valuable protein [28].

- Implement AI-Driven Screening: Use AI algorithms to analyze historical data and predict optimal crystallization conditions, moving away from random trial-and-error approaches [28] [29].

- Leverage Automated Robotic Systems: Enhanced robotic systems streamline and improve the reproducibility of the crystallization process [29].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Ensemble Models for Solubility Prediction

This table summarizes the quantitative performance of different AI models from a study predicting the solubility of Clobetasol Propionate in supercritical CO₂ [25].

| Model Name | R² Score | RMSE (Root Mean Square Error) | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gradient Boosting (GBDT) | 0.987 | 8.21 × 10⁻³ | Sequential building of trees to correct errors; high predictive accuracy [25]. |

| Random Forest (RF) | >0.9 | Not Specified | Uses bagging with bootstrap samples; robust against overfitting [25]. |

| Extremely Randomized Trees (ET) | >0.9 | Not Specified | Uses entire dataset; more random splits than RF; good for reducing variance [25]. |

Table 2: Market Trends & Technological Drivers in Protein Crystallography

This table outlines key technologies influencing the protein crystallization market, which can guide investment and adoption decisions [28] [29].

| Technology | Market Impact / CAGR | Key Function in Crystallization |

|---|---|---|

| X-ray Crystallography | Dominant (56.15% share in 2024) | The incumbent, gold-standard method for atomic-resolution structure determination [28]. |

| Software & Services | 12.19% (Projected CAGR) | Cloud-native suites for automated phasing, model validation, and AI-assisted refinement [28]. |

| Microfluidic Screening | 11.73% (Projected CAGR) | Dramatically reduces sample volume and screens thousands of conditions rapidly [28]. |

| AI-Driven Optimization | Key Trend | Uses algorithms to predict crystallization conditions and outcomes, reducing trial-and-error [28] [29]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Developing an AI Model for Drug Solubility in Supercritical CO₂

This protocol details the methodology for creating a robust predictive model, as described in recent scientific literature [25].

1. Data Pre-processing

- Data Collection: Compile a dataset of experimental solubility measurements (output, s) with corresponding temperature and pressure values (inputs). A typical dataset may contain ~45 observations [25].

- Outlier Detection: Perform an outlier analysis (e.g., using Cook's distance) on the dataset. Identify and remove any influential outliers (e.g., 2 out of 45 data points) to prevent them from skewing the model [25].

- Data Normalization: Normalize the input data (temperature and pressure) to a common scale (e.g., 0 to 1) to ensure stable and efficient model training [25].

- Data Splitting: Split the cleaned and normalized data into training, validation, and test sets. A common split is 70% for training, 15% for validation, and 15% for testing [26].

2. Model Selection & Hyperparameter Tuning

- Select Base Models: Choose ensemble tree-based models such as Gradient Boosting (GBDT), Random Forest (RF), and Extremely Randomized Trees (ET) [25].

- Hyperparameter Optimization: Employ a metaheuristic optimization algorithm like Ant Colony Optimization (ACO) to find the optimal hyperparameters for each model. This step is crucial for maximizing performance and preventing overfitting [25].

3. Model Training & Evaluation

- Training: Train each of the tuned models (GBDT, RF, ET) on the training set.

- Validation: Use the validation set to evaluate the models during the tuning phase and for early stopping to prevent overfitting.

- Performance Assessment: Evaluate the final models on the held-out test set. Use metrics such as R² (coefficient of determination) and RMSE (Root Mean Square Error) to compare performance. An R² > 0.9 and a minimized RMSE indicate a good model [25].

Mandatory Visualization

AI Solubility Modeling Workflow

Model Performance & Stability Check

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for AI-Driven Solubility & Crystallization Studies

| Item / Solution | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Supercritical CO₂ | Serves as a green solvent in pharmaceutical processing for drug nanoparticle production. It eliminates the need for organic solvents, aligning with lower PMI goals [25]. |

| Microfluidic Chips | Enable high-throughput screening of crystallization conditions. They reduce sample volume requirements by an order of magnitude and can generate results in minutes instead of days [28]. |

| Specialized Crystallization Reagents & Kits | Pre-formulated screens (e.g., from Hampton Research) provide a wide array of conditions (precipitants, buffers, salts) to efficiently identify initial crystal hits [29]. |

| Sodium-malonate Formulations | Act as dual-function reagents, serving as both a cryoprotectant and a precipitant. This illustrates innovative consumables that streamline workflows and improve success rates [28]. |

| AI/ML Software Suites | Cloud-native software (e.g., from Rigaku, Bruker) offers automated phasing, model validation, and AI-assisted refinement, which are critical for translating diffraction data into structural models [28]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Poor Convergence in Bayesian Optimization

Problem: The Bayesian Optimization (BO) algorithm is not converging to a satisfactory optimum, or the performance is inconsistent.

Possible Cause 1: Inadequate Initial Data

- Explanation: BO requires a small set of initial data to build its initial surrogate model. If these points are not representative of the experimental space, the algorithm may struggle to find good subsequent points [30].

- Solution: Instead of choosing initial points randomly, use a space-filling design like a Latin Hypercube Design (LHD) for the initial set of experiments. One study employed a 5-point LHD to investigate crystallization factors before starting the BO routine [31].

Possible Cause 2: Excessive Measurement Noise

- Explanation: High levels of noise in experimental measurements can obscure the underlying response surface, confusing the algorithm and leading to poor decisions about the next experiment [30].

- Solution: Implement replicate experiments at critical points to better estimate and account for noise. For crystallization processes, ensure consistent seed quality and use Process Analytical Technology (PAT) for precise, real-time measurements to reduce variability [31].

Possible Cause 3: Incorrect Hyperparameter Tuning

- Explanation: The performance of the Gaussian Process (GP) model in BO is sensitive to the choice of kernel hyperparameters (e.g., length scale) [32].

- Solution: Use platforms that automate hyperparameter tuning via marginal likelihood maximization. For advanced users, manually inspect the model's fit after each iteration and adjust priors if necessary [33].

Guide 2: High Material Usage in Process Development

Problem: The experimental campaign is consuming too much active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) or other valuable materials.

- Possible Cause: Inefficient Experimental Design

- Explanation: Traditional Design of Experiments (DoE), while systematic, may not be the most material-efficient approach, especially for processes with a large number of variables or when the goal is to find a single optimum [34].

- Solution: Switch to an Adaptive Bayesian Optimization strategy. A comparative study on batch cooling crystallization demonstrated that BO reduced material usage by up to 5-fold compared to a traditional statistical DoE approach [34]. BO's ability to intelligently select the most informative next experiment minimizes wasted resources.

Guide 3: Difficulty Modeling Complex Crystallization Processes

Problem: The process response (e.g., crystal size distribution, nucleation rate) is highly non-linear and difficult to model accurately with polynomial models from traditional DoE.

- Possible Cause: Limitations of Pre-Defined Model Forms

- Explanation: Traditional DoE requires a predetermined mathematical model (e.g., linear or quadratic). This creates a bias that may not accurately reflect the underlying, complex system dynamics of a crystallization process [32].

- Solution: Use BO with a Gaussian Process surrogate model. GPs are non-parametric and highly flexible, allowing them to capture complex, non-linear relationships without a pre-specified functional form [32]. This is particularly useful for modeling stochastic phenomena like nucleation.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: When should I choose Traditional DoE over Bayesian Optimization for my crystallization process?

| Scenario | Recommended Method | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Initial process scoping | Traditional DoE | DoE (e.g., Box-Behnken) is excellent for building a broad understanding of the design space, identifying major factor effects, and creating a robust initial process model [30] [35]. |

| Finding a global optimum with limited material | Bayesian Optimization | BO is a sequential model-based approach that is highly efficient at finding optimal conditions with fewer experiments, directly reducing material usage [34]. |

| Process characterization & validation | Traditional DoE | DoE is well-established and widely accepted for defining a process design space and providing the data required for regulatory filings within the Quality by Design (QbD) framework [36] [35]. |

| Optimizing a known process region | Bayesian Optimization | Once a viable region is identified, BO can refine the conditions with high accuracy in the vicinity of the optimum, as it provides a more detailed local model [30]. |

FAQ 2: Does Bayesian Optimization truly require fewer experiments than Traditional DoE?

The answer is context-dependent. In a direct comparison for alkaline wood delignification, BO did not enable a decrease in the total number of experiments to reach optimal conditions compared to a Box-Behnken DoE [30]. However, in other applications, such as pharmaceutical crystallization for compounds with slow and fast kinetics, BO reduced material usage up to 5-fold [34]. The efficiency gain appears most significant in processes where experiments are expensive, time-consuming, or material-intensive, and where the response surface is complex.

FAQ 3: What are the main computational challenges with Bayesian Optimization?

The two primary challenges are:

- Computational Expense: The computational cost of training the Gaussian Process model scales cubically (O(n³)) with the number of data points n, which can become prohibitive for very large datasets [32].

- Sensitivity to Model Choices: Performance can be sensitive to the choice of the surrogate model's kernel (covariance function) and the acquisition function [33] [32].

FAQ 4: How is "efficiency" quantitatively measured in these methodologies?

Efficiency can be measured by several Key Performance Indicators (KPIs), as shown in the table below.

| Efficiency Metric | Traditional DoE | Bayesian Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Experiments | Fixed from the start (e.g., 15 for a Box-Behnken with 3 factors) [30]. | Not necessarily lower, but more informative per experiment [30] [34]. |

| Material Usage | Can be higher due to fixed experimental plan. | Demonstrated ~5x reduction in crystallization case study [34]. |

| Objective Function Improvement | Model is built after all data is collected. | Achieved ~10% improvement in one crystallization case study within just 1 iteration [31]. |

| Model Accuracy | Good for global linear/quadratic trends. | Can provide more accurate models in the vicinity of the optimum [30]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Setting Up a Bayesian Optimization for a Cooling Crystallization

This protocol is adapted from a study optimizing the cooling crystallization of lamivudine [34] [31].

Objective: To determine the optimal conditions of cooling rate, seed mass, and seed point supersaturation to achieve target crystal nucleation and growth rates.

Key Research Reagent Solutions & Materials:

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) | The compound of interest to be crystallized (e.g., Lamivudine). |

| Solvent System | A suitable solvent for dissolution and crystallization (e.g., Ethanol). |

| Seed Crystals | High-quality crystals of the API used to control secondary nucleation and ensure consistent crystal form. |

| Multi-vessel Reactor System | An automated platform (e.g., Scale-Up Crystallisation DataFactory) with dosing capabilities for seed and anti-solvent addition [31]. |

| Process Analytical Technology (PAT) | Integrated tools like HPLC for concentration and imaging for particle size analysis to measure process outcomes in real-time [31]. |

Methodology:

- Define Objective Function: Formulate a mathematical function, g, that encapsulates all targets. For example:

- Maximize yield.

- Penalize deviations from target nucleation and growth rates [31].

- Initial Design: Perform a small set of initial experiments (e.g., 5 points) using a Latin Hypercube Design (LHD) to explore the factor space broadly and provide initial data for the BO model [31].

- Configure BO: Select a Gaussian Process model with a Matern kernel (a good default for physical processes) and an acquisition function like Expected Improvement (EI) or Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) [32] [37].

- Run Iterative Loop: a. Update Model: Fit the GP surrogate model to all collected data. b. Maximize AF: Identify the next best experimental conditions by maximizing the acquisition function. c. Execute Experiment: Run the crystallization experiment at the suggested conditions using the automated platform. d. Measure Responses: Use PAT tools to measure yield, crystal size distribution, etc.

- Terminate: Stop when the objective function converges, a performance target is met, or the experimental budget is exhausted.

Protocol 2: Executing a Traditional DoE for Process Characterization

Objective: To build a robust empirical model (Response Surface Methodology) for a crystallization process to understand factor interactions and define the operating design space.

Methodology:

- Select Factors and Ranges: Choose process parameters (e.g., temperature, cooling rate, agitation speed) and their minimum/maximum levels based on prior knowledge [30].

- Choose Experimental Design: Select a structured design like a Box-Behnken Design (BBD) or Central Composite Design (CCD). For example, a BBD with 3 factors requires 15 experiments [30].

- Execute Experiments: Run all experiments in the designed order, ideally randomizing to avoid systematic bias.

- Model Building and Analysis:

a. Fit a second-order polynomial model (e.g.,

y = β₀ + Σβᵢxᵢ + Σβᵢⱼxᵢxⱼ + Σβᵢᵢxᵢ²) to the data [30]. b. Use statistical tests (t-tests, p-values) to remove insignificant model terms. c. Validate the model using analysis of variance (ANOVA) and diagnostic plots. - Optimization: Use the validated model to locate a optimum operating region that meets all critical quality attributes (CQAs).

Workflow Visualization

Bayesian Optimization Workflow

Traditional DoE Workflow

Implementing Continuous Crystallization Systems for Enhanced Control and Sustainability

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary advantages of continuous crystallization over batch processes in pharmaceutical manufacturing? Continuous crystallization offers several key advantages, including more consistent crystal size distribution (CSD), reduced process mass intensity (PMI), and better tolerance to impurities. Studies on paracetamol manufacturing show that continuous systems can achieve a lower environmental impact as quantified by PMI, though batch may sometimes have a lower overall cost. Furthermore, continuous systems are better suited for expansion and can maintain production during supply chain disruptions by allowing for strategic overstocking [38].

Q2: How can I address clogging issues in my continuous crystallizer? Clogging is often caused by the buildup of solid deposits or impurities. To troubleshoot, implement a regular cleaning and maintenance schedule, which can involve flushing the equipment with a cleaning solution. Using filters or screens to trap solid particles before they enter the crystallizer can also prevent clogging and ensure uninterrupted operation. For tubular crystallizers, technologies like the Continuous Oscillatory Baffled Crystallizer (COBC) are designed to achieve a more uniform residence time distribution, which helps minimize blockages [39] [40].

Q3: My system is producing crystals with inconsistent sizes. What should I check? Crystal size variation is frequently due to fluctuations in temperature, supersaturation levels, or agitation. To promote uniform crystal growth, maintain stable operating conditions and ensure the solution is properly mixed. Adjusting parameters like the cooling rate, seeding process, or introducing nucleation agents can help achieve a more consistent CSD. Advanced strategies involve using kinetic modeling and steady-state optimization to control the critical operating conditions that influence crystal size [39] [40] [41].

Q4: What is fouling and how can it be mitigated? Fouling, or scaling, occurs when crystals stick to the surfaces of the crystallizer equipment, reducing heat transfer efficiency and hindering performance. Common causes include impurities in the feed stream, temperature variations, and the precipitation of inorganic salts. Solutions include pre-treating the feed to remove impurities, using anti-fouling agents, and employing advanced technologies like high-power ultrasound to prevent scale formation on crystallizer surfaces [42].

Q5: How can digital technologies and AI optimize a continuous crystallization process? Human-in-the-Loop (HITL) and active learning frameworks integrate human expertise with data-driven insights to rapidly optimize complex crystallization processes. For instance, Bayesian optimization algorithms can efficiently explore the experimental design space with fewer experiments, optimizing for yield or purity. This approach has been successfully used to develop processes tolerant to high levels of impurities (e.g., magnesium up to 6000 ppm in lithium carbonate crystallization) and to optimize multi-step telescoped processes, significantly reducing PMI values [43] [44].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Operational Issues

| Problem | Possible Causes | Troubleshooting Steps | Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low Crystallization Efficiency | Improper temperature control, impurities in feed solution, low supersaturation [39] [7]. | 1. Monitor and adjust temperature to recommended range.2. Analyze and pre-treat feed to remove impurities.3. Check and adjust supersaturation levels. | Implement regular feed quality control; install robust temperature control systems. |

| Equipment Clogging | Buildup of solid deposits or impurities, uncontrolled agglomeration [39] [42]. | 1. Inspect for signs of clogging.2. Flush system with cleaning solution.3. Check filters and screens. | Install pre-filters; establish regular cleaning schedule; optimize mixing to prevent stagnation. |

| Crystal Size Variation | Fluctuations in temperature or agitation, non-uniform supersaturation, incorrect seeding [39] [41]. | 1. Stabilize cooling/evaporation rates.2. Ensure proper mixing and circulation.3. Adjust seeding protocol or use nucleation agents. | Monitor Crystal Size Distribution (CSD) in real-time if possible; maintain stable operating conditions. |

| Fouling/Scaling | Impurities in feed, temperature differences causing hot/cold spots, precipitation of inorganic salts [42]. | 1. Clean fouled surfaces.2. Increase solution circulation rate.3. Use anti-fouling additives. | Use high-power ultrasound technology; pre-treat feed; manage temperature profile. |

| Poor Vacuum Levels | Vacuum pump leaks, damaged seals or gaskets, undersized pump [41]. | 1. Check vacuum pump for leaks/malfunctions.2. Inspect seals and lines for damage.3. Verify pump is correctly sized. | Schedule regular vacuum system maintenance; conduct routine integrity checks. |

Guide 2: Optimizing for Product Purity and PMI

| Problem | Possible Causes | Troubleshooting Steps | Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low Product Purity | Impurities incorporated into crystal lattice, inadequate washing, mother liquor inclusion [7]. | 1. Check and control feed composition (pH, concentration).2. Optimize operating conditions (cooling rate, agitation).3. Improve final washing and purification steps. | Implement in-line analytics to monitor purity; optimize crystallization kinetics to favor pure crystal growth. |

| High Process Mass Intensity (PMI) | Low yield, excessive solvent use, need for multiple purification steps, high energy consumption [38] [44]. | 1. Optimize process for higher yield (e.g., via AI).2. Telescope multiple steps without isolation.3. Select greener solvents (e.g., 2-MeTHF). | Design processes for mass efficiency; adopt continuous, telescoped flow synthesis; utilize self-optimizing systems. |

| Uncontrolled Nucleation | Excessively high supersaturation, mechanical shock, insufficient seeding [7] [40]. | 1. Control supersaturation profile.2. Implement controlled seeding.3. Minimize mechanical vibrations. | Use focused beam reflectance measurement (FBRM) to monitor nucleation; design precise supersaturation control loops. |

Key Experimental Data and Protocols

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Batch vs. Continuous Crystallization for an API (Paracetamol)

| Parameter | Batch Crystallizer | Continuous MSMPR Crystallizer | Source |

|---|---|---|---|