Biocatalysis in Green Chemistry: AI-Driven Enzymes for Sustainable Pharmaceutical Processes

This article explores the transformative role of biocatalysis in advancing green chemistry within the pharmaceutical industry.

Biocatalysis in Green Chemistry: AI-Driven Enzymes for Sustainable Pharmaceutical Processes

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of biocatalysis in advancing green chemistry within the pharmaceutical industry. It examines the foundational principles that make enzymes powerful, sustainable tools for chemical synthesis and investigates cutting-edge methodologies, including machine learning and AI for enzyme discovery and engineering. The content addresses key challenges in scaling and optimization, providing troubleshooting insights for real-world application. Finally, it offers a comparative analysis of biocatalysis against traditional methods, validating its economic and environmental benefits. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes the latest trends from 2025 to outline a future where biocatalysis is central to efficient and eco-friendly drug manufacturing.

The Green Imperative: How Biocatalysis Principles Are Redefining Sustainable Pharma

Core Principles of Green Chemistry as a Roadmap for Biocatalysis

Biocatalysis, which utilizes enzymes or whole cells to catalyze chemical transformations, is widely regarded as a cornerstone of sustainable chemistry. Its alignment with the 12 Principles of Green Chemistry provides a robust framework for developing environmentally benign pharmaceutical manufacturing processes. Enzymes offer significant advantages including high selectivity (enantio-, regio-, and chemo-selectivity), operation under mild reaction conditions, and biodegradability [1] [2]. The pharmaceutical industry has increasingly adopted biocatalytic approaches for the synthesis of chiral active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), with approximately 57% of APIs being chiral molecules often marketed in homochiral form [2].

However, a critical assessment reveals that biocatalysis is not automatically "green" by default. Quantitative metrics demonstrate that many biocatalytic processes face challenges related to water consumption, wastewater production, and diluted aqueous solutions that can negatively impact their environmental footprint [1] [3]. This application note establishes a structured framework based on the Principles of Green Chemistry to guide researchers in designing biocatalytic processes that genuinely minimize environmental impact while maintaining economic viability, particularly for drug development applications.

Core Green Chemistry Principles Applied to Biocatalysis

Prevention of Waste and Atom Economy

The first principle of Green Chemistry emphasizes waste prevention rather than treatment or cleanup after it has been created [4]. In biocatalysis, this can be measured using the E-factor (kg waste per kg product) or Process Mass Intensity (total mass of materials used per mass of product) [1] [4]. The atom economy principle, developed by Barry Trost, focuses on maximizing the incorporation of all starting materials into the final product [4].

Biocatalytic reactions typically demonstrate superior atom economy compared to traditional chemical synthesis due to their high selectivity and minimal protection/deprotection steps. However, the assumption that aqueous biocatalysis automatically generates less waste requires careful examination. As shown in Table 1, dilute aqueous biocatalytic systems can produce substantial waste, primarily from water and buffers [1].

Table 1: Waste Analysis of a Generic Biocatalytic Reaction in Aqueous Media [1]

| Component | Typical Concentration [mol L⁻¹] | Mass Ratio (Auxiliary to Product) [kg kg⁻¹] |

|---|---|---|

| Water | 55 | 500 |

| Buffer (50 mM potassium phosphate) | 0.05 | 2 |

| Enzyme (40 kDa) | 1 × 10⁻⁶ | 0.04 |

| Product (MW 200 g mol⁻¹) | 0.010 | 1 |

Strategies to improve waste metrics in biocatalysis include:

- Implementing two-liquid phase systems (2LPS) to increase substrate loading and reduce aqueous waste [1]

- Recycling aqueous reaction mixtures, which can reduce E-factor by more than 10-fold [1]

- Developing immobilized enzyme systems for reuse across multiple batches [2]

- Applying membrane reactors to enable continuous operation and reduce solvent consumption [1]

Safer Solvents and Auxiliaries

The choice of reaction media significantly influences the sustainability profile of biocatalytic processes. While water is considered the paradigm of green solvents—being non-hazardous, non-flammable, and readily available—its practical application in biocatalysis faces challenges with hydrophobic substrates that require diluted conditions (typically 10-100 mM) [1] [3]. This limitation has driven the development of alternative solvent systems:

Table 2: Comparison of Biocatalytic Reaction Media and Their Environmental Impact

| Reaction Media | Advantages | Limitations | CO₂ Production (kg CO₂·kg product⁻¹)* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aqueous Systems | Non-hazardous, natural enzyme environment | Low substrate loading, high wastewater production | 15-25 (with solvent recycling) |

| Water-miscible Co-solvents (e.g., ethanol, tert-butanol) | Increased substrate loading, possible co-substrate function | Potential enzyme inhibition, biocompatibility issues | Highly dependent on recycling efficiency |

| Two-Liquid Phase Systems (e.g., butyl acetate, MTBE) | High substrate loading, product sink, simplified work-up | Phase transfer limitations, potential enzyme shear stress | 8 (compared to 520 in dilute systems) |

| Deep Eutectic Solvents | Biodegradable, renewable, tunable properties | Limited database on biocompatibility and toxicity | Emerging data, typically lower than fossil solvents |

| Biogenic Solvents (e.g., 2-MeTHF) | Renewable resources, reduced fossil dependence | May require specialized waste treatment | Lower than fossil-based solvents |

*For a generic industrial biotransformation at 100 g L⁻¹ loading [3]

Recent research has demonstrated the promise of deep eutectic solvents (DES) as sustainable media for biocatalysis. For instance, novel alcohol dehydrogenase activation by the choline component of deep eutectic solvents represents an emerging approach [5]. Similarly, biocatalytic synthesis of lipophilic (hydroxy)cinnamic esters in deep eutectic mixtures has shown promising results as a sustainable alternative to organic solvents [6].

Energy Efficiency and Designing Safer Chemicals

Biocatalytic processes typically operate at ambient temperature and pressure, significantly reducing energy demands compared to conventional chemical synthesis that often requires high temperatures and pressures [1] [2]. This inherent energy efficiency aligns with the Green Chemistry principle advocating for mild reaction conditions.

The principle of designing safer chemicals emphasizes that "chemical products should be designed to preserve efficacy of function while reducing toxicity" [4]. Biocatalysis contributes to this principle through several mechanisms:

- Enzymes enable precise stereoselective synthesis,

- Creating single enantiomers of pharmaceutical compounds

- Avoiding the production of racemic mixtures

- Minimizing potentially toxic stereoisomers

- Biocatalytic routes often avoid hazardous reagents and reactive intermediates

- Reducing risks throughout the synthetic pathway

An exemplary application is the biocatalytic synthesis of intermediates for drugs like Islatravir (HIV investigational drug) and Sitagliptin (antidiabetic medication), where engineered enzymes provide efficient, selective routes under mild conditions [2] [7].

Quantitative Environmental Metrics for Biocatalysis

E-Factor and Process Mass Intensity

The E-Factor, developed by Roger Sheldon, remains a fundamental metric for assessing process sustainability, calculated as kg waste per kg product [1] [4]. The related Process Mass Intensity (PMI) expresses the ratio of the total mass of all materials used to the mass of the active drug ingredient produced [4]. These metrics provide crucial quantitative assessments of biocatalytic processes, moving beyond qualitative "green" claims.

Research indicates that through process intensification, biocatalytic E-factors can be dramatically reduced. For example, the whole-cell production of (S)-4-chloro-3-hydroxybutanoate ethyl ester demonstrated an E-factor reduction from 520 (in dilute aqueous system) to 8 when using a two-liquid phase system with butyl acetate [1].

Total Carbon Dioxide Release (TCR)

The Total Carbon Dioxide Release (TCR) concept addresses the kilograms of CO₂ produced by a kilogram of product, providing a unified metric for environmental impact assessment [3]. This approach converts all waste streams into CO₂ equivalent production, acknowledging that wastes will ultimately be converted to CO₂ and released into the environment.

For generic industrial biotransformations at 100 g L⁻¹ loading, recent assessments indicate comparable CO₂ production (15-25 kg CO₂·kg product⁻¹) for both aqueous and non-conventional media, provided that extractive solvents are recycled at least 1-2 times [3]. The environmental impact heavily depends on wastewater treatment requirements, with conventional treatment producing approximately 0.073 kg CO₂·kg product⁻¹ compared to 0.63 kg CO₂·kg product⁻¹ for incineration of recalcitrant wastewater [3].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

General Workflow for Biocatalytic Process Development

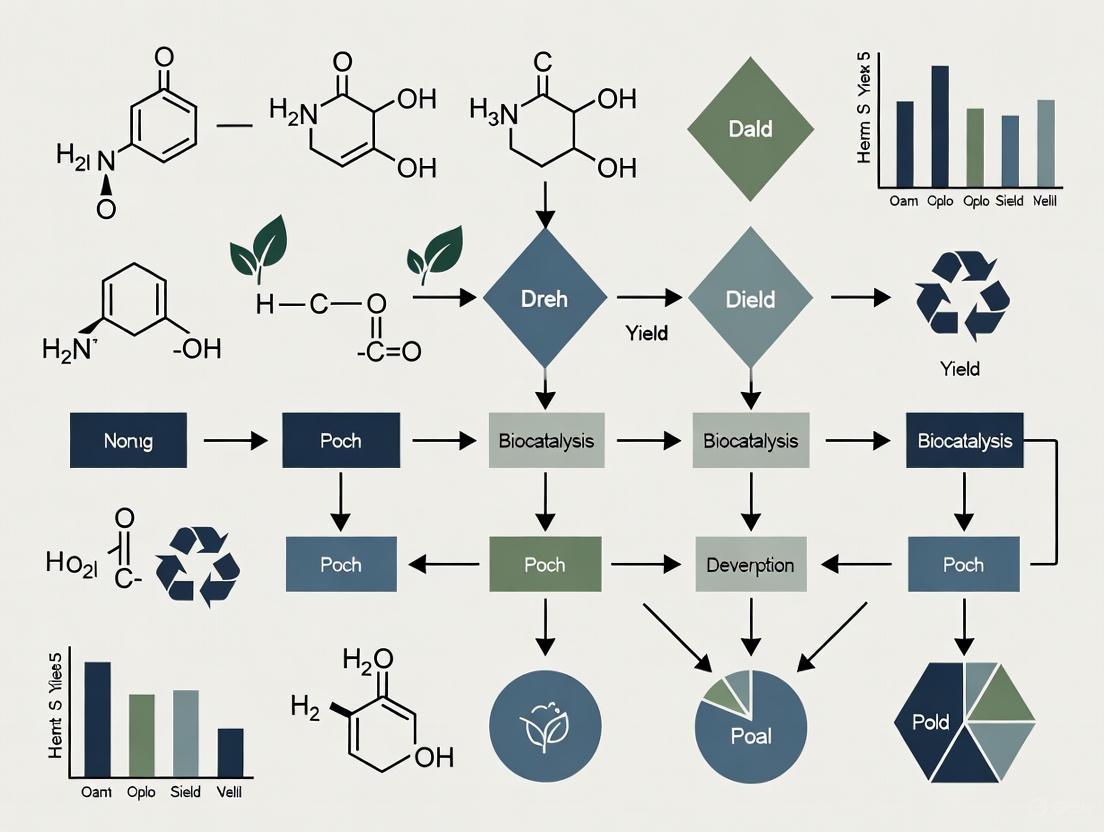

The following diagram illustrates a systematic approach to developing biocatalytic processes aligned with Green Chemistry principles:

Protocol: Biocatalysis in Two-Liquid Phase Systems (2LPS)

Objective: Implement a two-liquid phase system to enhance substrate loading and reduce environmental impact for hydrophobic substrate transformations.

Materials:

- Biocatalyst: Isolated enzyme or whole cells (e.g., recombinant whole-cells overexpressing target enzyme)

- Aqueous Phase: Appropriate buffer (e.g., 50-100 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.0-8.0)

- Organic Phase: Green solvent (e.g., butyl acetate, 2-MeTHF, MTBE)

- Substrate: Hydrophobic compound of interest

- Equipment: Round-bottom flask, orbital shaker or bioreactor, separation funnel

Procedure:

- Phase Selection: Based on substrate and product logP values, select an organic phase with high partition coefficients for substrate and product. Biomass-derived 2-methyl tetrahydrofuran (2-MeTHF) represents a sustainable option [1].

- System Setup: In the reaction vessel, combine:

- Aqueous phase (30-70% v/v) containing biocatalyst

- Organic phase (30-70% v/v) containing substrate at high concentration (50-200 g L⁻¹)

- Reaction Execution:

- Incubate with agitation (150-250 rpm) to create emulsion and enhance interfacial surface area

- Maintain optimal temperature (25-37°C for mesophilic enzymes)

- Monitor reaction progress by sampling both phases

- Product Recovery:

- Allow phases to separate or use mild centrifugation

- Recover product from organic phase

- Aqueous phase and biocatalyst can potentially be reused for subsequent batches

- Downstream Processing:

- Concentrate organic phase via distillation

- Purify product using standard techniques (crystallization, chromatography)

Key Green Chemistry Considerations:

- Solvent Recycling: Implement distillation to recover and reuse the organic phase for multiple batches, significantly reducing PMI and TCR [3].

- Aqueous Phase Reuse: Evaluate biocatalyst stability and reaction performance over multiple cycles to minimize waste generation [1].

- Wastewater Treatment: Assess wastewater composition to determine appropriate treatment pathway (conventional vs. specialized) to minimize CO₂ production [3].

Protocol: Statistical Optimization of Recombinant Enzyme Expression

Objective: Apply design of experiments (DoE) methodology to optimize recombinant enzyme expression for polymer degradation applications, based on recent research [5].

Materials:

- Expression System: Recombinant enzyme (e.g., Amycolatopsis mediterranei Cutinase) in suitable host (E. coli, yeast)

- Culture Media: Defined or complex media components

- Inducers: IPTG or autoinduction system components

- Analytical Tools: SDS-PAGE, activity assays, protein quantification

- Statistical Software: Design-Expert, JMP, or equivalent

Procedure:

- Experimental Design:

- Identify critical factors (temperature, inducer concentration, induction time, aeration)

- Create response surface methodology (RSM) design (Central Composite, Box-Behnken)

- Define response variables (enzyme activity, expression level, volumetric productivity)

- Parallel Expression Trials:

- Execute expression trials according to experimental design

- Maintain consistent fermentation conditions across trials

- Harvest cells at optimal timepoints

- Enzyme Characterization:

- Quantify expression levels via SDS-PAGE densitometry

- Measure specific activity toward target substrates (e.g., polymer degradation assays)

- Assess enzyme stability under process conditions

- Model Development:

- Analyze results to build predictive models for enzyme expression

- Identify significant factors and interaction effects

- Determine optimal expression conditions through response optimization

- Validation:

- Confirm model predictions with verification experiments

- Scale-up optimized process to pilot scale if applicable

Green Chemistry Benefits: This approach minimizes experimental waste while maximizing enzyme production efficiency, reducing the environmental footprint of biocatalyst preparation [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Green Biocatalysis

| Reagent/Material | Function in Biocatalysis | Green Chemistry Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Alcohol Dehydrogenases (ADHs) | Redox biocatalysis for chiral alcohol synthesis | Enable asymmetric synthesis without heavy metal catalysts; often cofactor-dependent requiring recycling systems |

| Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) | Green reaction media alternative | Biodegradable, renewable components (e.g., choline-based); tunable properties for different substrates [5] [6] |

| Candida antarctica Lipase B (CALB) | Versatile hydrolase for esters, amides, polyesters | High stability in non-conventional media; commercially available in immobilized form (Novozym 435) [2] |

| 2-Methyltetrahydrofuran (2-MeTHF) | Bio-based solvent for two-liquid phase systems | Derived from renewable biomass (e.g., corn cobs, bagasse); preferable to fossil-derived solvents [1] |

| Transaminases | Synthesis of chiral amines from ketones | Alternative to metal-catalyzed amination; crucial for API synthesis (e.g., Sitagliptin) [2] |

| Methacrylate/Divinylbenzene Copolymer | Support for enzyme immobilization | Enables enzyme reuse and continuous processing; improves stability under process conditions [2] |

| Whole-cell Biocatalysts | Contain multiple enzymes with cofactor regeneration | Eliminate enzyme purification steps; enable multi-step biotransformations in single vessel [1] |

Decision Framework for Media Selection

The following decision diagram provides guidance for selecting appropriate reaction media based on substrate and process requirements:

Emerging Research Directions and Future Perspectives

Recent advances in biocatalysis continue to enhance its alignment with Green Chemistry principles. Key emerging areas include:

Biocatalytic Hydrogenation of Unactivated Olefins: Novel radical-based mechanisms like biocatalytic cooperative metal-mediated hydrogen atom transfer (BioHAT) enable asymmetric reduction of unactivated olefins using engineered heme proteins in water under ambient conditions [7].

Enzyme-Mediated Protecting Group Chemistry: Research into fungal unspecific peroxygenases (UPOs) for selective benzyl ether deprotection replaces traditional metal-based methods with biocatalysts functioning in mild, aqueous conditions [7].

Stereoselective Biocatalytic C–C Bond Formation: Engineering PLP-dependent enzymes to synthesize 1,2-amino alcohols from abiological amine substrates provides greener alternatives to traditional allylation methods [7].

Continuous Bioreactor Systems: Development of low-cost, continuous bioreactors for peptide production addresses environmental and scalability challenges, reducing intracellular concentration and enabling nutrient recycling [7].

These innovations demonstrate the ongoing potential of biocatalysis to provide sustainable solutions for pharmaceutical synthesis while adhering to the foundational principles of Green Chemistry.

Biocatalysis represents a powerful approach for implementing Green Chemistry principles in pharmaceutical research and development. By critically applying metrics such as E-factor, PMI, and TCR, researchers can move beyond assumptions of automatic "greenness" and genuinely optimize processes for sustainability. The integration of innovative reaction media, enzyme immobilization strategies, and process intensification approaches enables biocatalysis to deliver on its promise as a robust, sustainable technology for chemical synthesis. As the field advances through protein engineering, novel biocatalyst discovery, and integrated process design, biocatalysis will continue to provide increasingly efficient routes to complex molecules with reduced environmental impact.

Biocatalysis harnesses the power of natural enzymes to perform chemical conversions with high efficiency and selectivity, positioning it as a cornerstone of sustainable chemistry. This approach aligns with the principles of green chemistry by minimizing waste, utilizing renewable resources, and reducing energy consumption. The transition towards a circular economy necessitates the integration of waste products, such as lignocellulose, methane, and carbon dioxide, into a manufacturing carbon cycle, and biotechnology is uniquely suited to enable this shift [8]. In the pharmaceutical industry and beyond, biocatalysis demonstrates tremendous promise for enhancing energy efficiency and improving atom economy, thereby reducing the environmental footprint of chemical production [9]. This article details the quantitative environmental benefits and provides actionable protocols for implementing biocatalysis in research and industrial settings, framed within a broader thesis on green chemistry processes.

Quantitative Environmental Metrics for Biocatalysis

To substantiate the green claims of biocatalytic processes, it is essential to evaluate them using quantitative metrics. The E-Factor (kilograms of waste per kilogram of product) and the Total Carbon Dioxide Release (TCR) are two pivotal indicators for assessing environmental impact.

The following table summarizes the CO₂ production for a generic biotransformation at 100 g/L substrate loading, comparing processes in aqueous and non-conventional media, with recycling of extractive solvents significantly influencing the outcome [3].

Table 1: CO₂ Production in Different Biocatalytic Process Media

| Process Media | Upstream CO₂ Production (kg CO₂·kg product⁻¹) | Downstream CO₂ Production (kg CO₂·kg product⁻¹) | Total CO₂ Production (kg CO₂·kg product⁻¹) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aqueous Media | Lower | Higher (if solvents are not recycled) | 15 - 25 (with solvent recycling) |

| Non-Conventional Media | Higher | Lower | 15 - 25 (with solvent recycling) |

A critical factor in the sustainability of aqueous processes is the required wastewater treatment. A conventional mild treatment produces only about ~0.073 kg CO₂·kg product⁻¹, whereas incinerating recalcitrant wastewater can produce ~0.63 kg CO₂·kg product⁻¹ [3]. This highlights the importance of designing processes that generate readily treatable waste streams.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Engineering Improved Biocatalysts Using Saturation Mutagenesis

This protocol describes a targeted random mutagenesis approach to improve enzyme properties such as stability, activity, and selectivity for industrial applications [10].

Materials

- Template plasmid DNA containing the target gene.

- High-fidelity DNA polymerase (e.g., from the QuikChange kit).

- Mutagenic primers designed with an NNK codon (where N is any nucleotide, and K is G or T) for the target residue.

- DpnI restriction enzyme.

- Competent E. coli cells (e.g., DH5α or XL1-Blue).

Method

- Primer Design: Design forward and reverse mutagenic primers that are complementary to the same sequence. The target codon should be in the middle, flanked by at least 15 correctly matched bases. Use the NNK degeneracy to code for all 20 amino acids and one stop codon.

- PCR Amplification: Set up a PCR reaction using the plasmid template and the mutagenic primers to amplify the entire plasmid.

- Template Digestion: Digest the PCR product with DpnI to selectively cleave the methylated parental DNA template.

- Transformation: Transform the nicked, mutated plasmid into competent E. coli cells.

- Screening and Selection: Plate the cells and pick colonies for screening. For iterative saturation mutagenesis (ISM), take the best-hit mutant from one library and use it as the template for saturation mutagenesis at a second, distinct site. This branching process helps identify mutations with synergistic, additive effects [10].

Protocol 2: One-Pot Cascade Synthesis of Pseudouridine (Ψ)

This protocol describes an atom-economic, four-enzyme cascade for the quantitative rearrangement of uridine (U) to pseudouridine (Ψ), a critical component of mRNA vaccines [11].

Materials

- Uridine (U) substrate.

- Inorganic Phosphate (Pi).

- Enzymes: Uridine Phosphorylase (UP), Phosphopentomutase (DeoB), C-glycosidase (YeiN), and ΨMP-specific phosphatase (Yjjg).

- Purified enzymes with specific activities as detailed in Table 2.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Pseudouridine Synthesis

| Reagent / Enzyme | Function / Role in Cascade | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Uridine (U) | Starting material | Available in bulk quantities via fermentation [11]. |

| Inorganic Phosphate | Catalytic reagent | Regenerated by Yjjg; high concentrations (≤1.0 M) stabilize UP [11]. |

| Uridine Phosphorylase (UP) | Catalyzes phosphorolysis of U to Ribose-1-phosphate (Rib1P) and uracil. | Highly stable, especially in high-phosphate conditions [11]. |

| Phosphopentomutase (DeoB) | Isomerizes Rib1P to Ribose-5-phosphate (Rib5P). | Partially inhibited by phosphate (Ki ~0.6 mM) but retains ~10% basal activity [11]. |

| C-glycosidase (YeiN) | Catalyzes C-C coupling of Rib5P and uracil to form ΨMP. | Provides absolute β-stereoselectivity; reaction equilibrium favors ΨMP formation [11]. |

| Phosphatase (Yjjg) | Specifically hydrolyzes ΨMP to Ψ and Pi. | Enables catalytic phosphate recycling; avoids undesired hydrolysis of intermediate phosphates [11]. |

Method

- Reaction Setup: Combine U (target loading up to 250 g/L) and inorganic phosphate in an aqueous buffer at pH 7.0.

- Enzyme Addition: Add the purified enzymes UP, DeoB, YeiN, and Yjjg to initiate the cascade reaction.

- Incubation: Incubate the reaction mixture at 30-40 °C with mixing. The coordinated action of the enzymes drives the rearrangement via Rib1P, Rib5P, and ΨMP to the final product, Ψ.

- Product Isolation: Allow the reaction to proceed to completion. The high driving force of the rearrangement leads to a supersaturated solution of Ψ (~250 g/L). Recover the pure Ψ product via crystallization with an approximate yield of 90% [11].

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence of the four-enzyme cascade for the conversion of uridine to pseudouridine, highlighting the regeneration of phosphate.

Diagram 1: Four-enzyme cascade for pseudouridine synthesis. The red arrow highlights the critical recycling of inorganic phosphate, which acts as a catalytic reagent [11].

The iterative process for engineering improved enzymes through saturation mutagenesis is shown below.

Diagram 2: Workflow for iterative enzyme engineering. Green indicates a productive branch with synergistic improvements, while red indicates a non-productive branch that is terminated [10].

Application Notes and Discussion

The case study on pseudouridine production demonstrates the profound benefits of biocatalysis. The process achieves a quantitative yield, operates with a high atom economy due to a molecular rearrangement, and avoids protecting group chemistry [11]. The high product concentration (~250 g/L) and enzyme turnover (~10⁵ mol/mol) underscore its industrial viability and superiority over traditional synthetic routes that often require cryogenic conditions and hazardous chemicals [11].

A significant challenge in biocatalysis is the choice of reaction media. While aqueous systems are inherently safer, they can lead to high dilution factors for poorly soluble substrates. Non-conventional media can enable higher substrate loadings but introduce fossil-based solvents. The data in Table 1 shows that with smart process design, specifically the recycling of extractive solvents, both strategies can achieve a comparable and lower environmental impact [3]. Furthermore, using enzymes engineered for enhanced stability can mitigate their traditional susceptibility to denaturation in organic solvents, broadening their application range [9] [10].

In conclusion, leveraging advanced enzyme engineering tools like saturation mutagenesis and designing efficient cascade processes in appropriately chosen media are key strategies for realizing the full potential of biocatalysis. The protocols and data presented provide a framework for researchers and drug development professionals to implement these green chemistry principles, directly contributing to waste reduction, improved atom economy, and enhanced energy efficiency in chemical synthesis.

Biocatalysis, the use of enzymes to accelerate chemical transformations, represents a paradigm shift in sustainable industrial synthesis. Within the framework of green chemistry, enzymes serve as precision tools that align with core principles including waste prevention, use of safer solvents, and design for energy efficiency [12]. Their exceptional specificity and ability to function under mild reaction conditions offer a compelling alternative to traditional chemical processes, which often require hazardous materials, generate significant waste, and operate under energy-intensive conditions [13] [14]. This application note details the quantitative advantages of enzymatic catalysis and provides established protocols for evaluating enzyme stability, which is a critical determinant of industrial feasibility. The content is tailored for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to implement robust biocatalytic processes.

Quantitative Advantages of Enzymatic Catalysis

The theoretical benefits of biocatalysis are substantiated by measurable gains in process efficiency and environmental impact. The following table summarizes documented improvements from industrial implementations.

Table 1: Documented Industrial Benefits of Enzymatic Catalysis

| Process/Product | Key Enzyme(s) Used | Documented Advantages | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Edoxaban (Anticoagulant) | Not Specified | 90% reduction in organic solvent usage; 50% decrease in raw material costs; simplified filtration steps (reduced from 7 to 3) | [12] |

| Sitagliptin (Antidiabetic) | Engineered Transaminase (R-ATA) | 99.95% enantiopurity; >10% increase in overall yield; 53% increase in productivity; eliminated use of a heavy metal (rhodium) catalyst | [15] |

| General Pharmaceutical Processes | Various | Up to 85% reduction in solvent use; Up to 40% reduction in waste management costs | [12] |

| Pregabalin (Neuropathic Pain) | Lipase | 40-45% yield increase; eliminated organic solvent use and reduced waste generation via a chemoenzymatic synthesis route | [15] |

The high atom economy and stereoselectivity of enzymes are the driving forces behind these performance metrics. By catalyzing reactions with exceptional chemo-, regio-, and stereoselectivity, enzymes minimize the formation of unwanted by-products, thereby simplifying downstream purification and reducing waste streams [14] [15]. This specificity is attributed to the precise three-dimensional structure of the enzyme's active site, which binds the substrate through a combination of non-covalent interactions, as described by the "lock and key" and "induced fit" models [13].

Core Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Assessing Enzyme Stability: A Key to Industrial Feasibility

For any biocatalytic process, enzyme stability under operational conditions is a critical parameter. The following protocol outlines methods to determine thermodynamic and kinetic stability, which are essential for evaluating an enzyme's operational lifespan and economic viability [16].

Title: Protocol for Measuring Thermodynamic and Kinetic Stability of Enzymes

Objective: To determine the melting temperature (T_m) and half-life (t_1/2) of a target enzyme, key parameters for assessing its operational stability.

Background: T_m reflects the temperature at which 50% of the enzyme is unfolded (thermodynamic stability), while t_1/2 reports the time required for a 50% loss of activity at a specific temperature (kinetic stability) [16].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Stability Assays

| Reagent/Material | Function in Protocol | Critical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Enzyme | The biocatalyst under investigation. | Recombinant or native form; known initial specific activity. |

| Appropriate Buffer | Maintains optimal pH for enzyme activity and stability. | Typically a 50-100 mM buffer (e.g., phosphate, Tris); pH verified for the specific enzyme. |

| Enzyme Substrate | Used in activity assays to measure functional enzyme concentration. | Must be specific, soluble, and enable a quantifiable signal (e.g., colorimetric, fluorescent). |

| Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) Instrument | Measures heat capacity changes associated with protein unfolding. | High-sensitivity calorimeter capable of controlled temperature ramping. |

| Thermostated Water Bath or Incubator | Maintains a constant temperature for long-term kinetic stability studies. | Precision of ±0.1°C; capacity to hold multiple samples. |

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a solution of the purified enzyme in an appropriate buffer. Aliquot into small volumes for individual time-point or temperature-point assays.

- Determination of Melting Temperature (

T_m):- Use Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) or a fluorescence-based thermal shift assay.

- For DSC, subject the enzyme solution to a controlled temperature ramp (e.g., 1°C/min) while monitoring the heat flow.

- The

T_mis identified as the peak of the thermal denaturation transition curve, where the heat capacity is at a maximum [16].

- Determination of Half-Life (

t_1/2):- Incubate the enzyme solution at the desired, constant operational temperature (e.g., 40°C, 50°C).

- At predetermined time intervals, remove aliquots and immediately place them on ice.

- Measure the residual enzymatic activity of each aliquot using a standard activity assay under optimal conditions (e.g., by monitoring substrate depletion or product formation spectrophotometrically).

- Plot the natural logarithm of residual activity versus time. The half-life is calculated from the first-order decay constant (

k) using the equation:t_1/2 = ln(2) / k[16].

- Data Analysis: A higher

T_mindicates greater resistance to thermal unfolding. A longert_1/2indicates better long-term operational stability at the target temperature, which directly impacts process cost-effectiveness by reducing the need for frequent enzyme replenishment.

The workflow for this stability assessment is outlined below.

General Considerations for Enzymatic Reaction Setup

A typical biocatalytic reaction requires optimization of several parameters to achieve maximum conversion and stability.

Table 3: Standard Reaction Setup Parameters for Biocatalytic Transformations

| Parameter | Typical Range | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature | 20-40°C | Balance between reaction rate and enzyme stability. Should be well below the enzyme's T_m. |

| pH | Near neutral (pH 6-8) | Buffer choice is critical; must not inhibit the enzyme or reaction. |

| Solvent System | Aqueous or aqueous-organic biphasic | Many enzymes, like lipases, function well in organic solvents. Co-solvents like DMSO may be needed for substrate solubility but can denature the enzyme [15] [17]. |

| Enzyme Form | Immobilized, free, or whole-cell | Immobilization often enhances stability, facilitates recovery, and allows reuse [13] [18]. |

| Substrate Concentration | Below K_M to several times K_M |

High concentrations may cause substrate inhibition. Must be balanced with solubility. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of biocatalysis relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details key solutions for developing and optimizing enzymatic processes.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Biocatalysis

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Immobilized Enzymes (e.g., Novozyme 435) | Heterogeneous biocatalysis; enables easy catalyst recovery and reuse. | CALB immobilized on acrylic resin is a benchmark catalyst for transesterification and amidation [17]. |

| Cofactors (e.g., NAD(P)H, ATP) | Essential for oxidoreductases, kinases, and ligases. | Often require regeneration systems (e.g., glucose dehydrogenase for NADPH) for economic viability [15]. |

| Engineered Transaminases | Synthesis of chiral amines, key intermediates in pharmaceuticals. | Critical for processes like the synthesis of Sitagliptin [15]. |

| Keto-Reductases (KREDs) | Enantioselective reduction of ketones to chiral alcohols. | Used in the synthesis of Montelukast and Atorvastatin [15]. |

| Lipases (e.g., CALB, CRL) | Hydrolysis and synthesis of ester bonds; transesterification. | Widely used in polymer functionalization, biodiesel, and synthesis of chiral intermediates [17]. |

| Specialized Buffers | Maintain optimal pH for enzyme activity and stability. | Must be compatible with the reaction and analysis methods (e.g., non-UV absorbing). |

The relationships between different enzyme classes and their primary industrial applications are visualized below.

The global biocatalysis market is experiencing a significant transformation, evolving from a niche technology into a strategic imperative for sustainable industrial manufacturing [19]. This growth is propelled by the convergence of several key factors: intensifying regulatory pressure for green chemistry, the compelling economic need for cost-effective and efficient production processes, and remarkable technological advancements in enzyme engineering and discovery [20] [21] [19]. The market's trajectory is characterized by robust growth rates, expanding applications across diverse industries, and a pronounced shift towards bio-based and environmentally friendly production methodologies. This document provides a detailed quantitative analysis of current growth projections, dissects regional and sector-specific adoption trends, and supplements this market context with foundational experimental protocols, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive overview of the field's commercial and technical landscape.

Market Size and Growth Projections

The biocatalysis and biocatalyst market is on a strong growth path, with projections varying slightly between different market research firms due to differing methodologies and segment focuses. The overall consensus, however, points to a steady and significant expansion over the next decade.

Table 1: Global Biocatalysis and Biocatalyst Market Size and Growth Projections

| Market Segment | 2024/2025 Benchmark Value | 2035/2037 Projected Value | Forecast Period | Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) | Key Source / Focus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Biocatalysis & Biocatalyst Market | USD 739.3 Million (2025) | USD 1374.7 Million (2035) | 2025-2035 | 6.4% | Future Market Insights [20] |

| Overall Biocatalysis & Biocatalyst Market | USD 25.34 Billion (2024) | USD 73.26 Billion (2035) | 2025-2035 | 10.13% | Market Research Future [22] |

| Overall Biocatalysis & Biocatalyst Market | USD 669.04 Million (2024) | USD 1.24 Billion (2037) | 2025-2037 | 4.9% | Research Nester [23] |

| Biocatalysis for API Synthesis | USD 2.7 Billion (2025) | USD 11.4 Billion (2032) | 2025-2032 | 22.8% | BioPharma Catalyst / Boston Consulting Group [19] |

The data reveals that the application of biocatalysis for Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) synthesis is a particularly high-growth segment, significantly outpacing the broader market [19]. This is driven by the pharmaceutical industry's intense focus on synthesizing complex chiral molecules with high selectivity, under milder and more sustainable conditions.

Regional Adoption Trends

Market growth is a global phenomenon, but with distinct regional characteristics and leadership. The following table and analysis summarize the key trends across major geographical markets.

Table 2: Regional Market Analysis and Growth Highlights

| Region | Market Share & Characteristics | Key Growth Drivers | Notable Country CAGR (to 2035) [20] |

|---|---|---|---|

| North America | Holds 41% share in biocatalysis for API synthesis market; a dominant and mature market [19]. | Robust biotechnology sector, stringent regulatory standards, FDA emphasis on green manufacturing, and strong R&D investment [20] [19]. | United States: 6.7% |

| Europe | Estimated 39% share of the global market; strong regulatory push for sustainability [20] [24]. | Stringent EU regulations (e.g., Renewable Energy Directive), strong manufacturing base, and cross-border collaboration within the EU [20] [24] [25]. | United Kingdom: 7.7% |

| Asia-Pacific | The fastest-growing region, led by China, Japan, and South Korea [25] [22]. | Rapid industrialization, massive government support and investment in biotech, and cost-competitive manufacturing [20] [25]. | South Korea: 8.5% Japan: 7.9% China: 6.9% |

| Rest of World | Emerging markets with niche opportunities; growth tied to infrastructure and energy projects [25]. | Government support for sustainable industries, foreign investment, and growing demand for eco-friendly products [25]. | Information Not Specified |

Industry Adoption and Application-Specific Trends

The adoption of biocatalysis is unevenly distributed across industries, with some sectors leading the charge due to compelling economic and regulatory benefits.

Table 3: Adoption Trends and Market Share by Application Segment

| Application Segment | Market Share & Significance | Key Trends and Drivers |

|---|---|---|

| Pharmaceuticals / Biopharmaceuticals | The largest application segment; API synthesis market is the fastest-growing [19] [22]. | Demand for complex chiral APIs (>99% enantioselectivity), need for cost reduction (25-38% lower production costs), and regulatory pressure for green chemistry (up to 65% reduction in solvent/waste) [19] [26]. |

| Biofuels | Holds ~28% share in the application category; a well-established and significant segment [20]. | Global push for renewable energy, government mandates (e.g., U.S. RFS, EU RED II), and use of enzymes like cellulases and lipases to convert biomass [20] [24]. |

| Food & Beverages | Expected to hold a significant revenue share (~33%); a mature and growing segment [23]. | Demand for natural bio-enzymes over chemical additives in processed foods, production of food supplements, and use in fermented alcohols [23]. |

| Detergents | A traditional and strong segment for hydrolase application [20]. | Extensive use of hydrolases (e.g., proteases, amylases) as cleaning agents, driven by consumer demand for effective and biodegradable ingredients [20]. |

Key Technology Trends Shaping Adoption

Several cross-cutting technology trends are accelerating adoption across all industries:

- Enzyme Engineering and Directed Evolution: The ability to engineer enzymes for improved stability, specificity, and activity toward non-natural substrates is a fundamental enabler, moving biocatalysis beyond natural reactions [27] [26].

- Integration of AI and Machine Learning: AI is being used for enzyme discovery, predicting protein structure and function, and optimizing process parameters, drastically reducing development time [27] [25].

- Multi-Enzyme Cascades and One-Pot Reactions: Combining multiple biocatalytic steps in a single vessel avoids intermediate isolation, significantly reducing waste, cost, and process mass intensity [27] [26].

- Process Intensification with Continuous Flow: The integration of immobilized biocatalysts with continuous flow reactors enhances productivity, enables catalyst reuse, and improves process control, leading to a higher return on investment [19].

Foundational Experimental Protocols in Biocatalysis

The following protocols provide a general framework for two common biocatalytic applications: a ketoreduction for chiral alcohol synthesis and a hydrolase-catalyzed hydrolysis. These can be adapted based on specific reaction requirements.

Protocol 1: Synthesis of a Chiral Alcohol via Ketoreductase (KRED)

Application Note: This protocol outlines the enzymatic asymmetric reduction of a prochiral ketone to produce a chiral alcohol, a pivotal transformation in pharmaceutical intermediate synthesis [26]. The method utilizes a ketoreductase (KRED) with an isopropanol (IPA)-coupled cofactor recycling system for operational simplicity.

Materials (Research Reagent Solutions):

- Ketoreductase (KRED): Biocatalyst (e.g., from Codexis, c-LEcta) [26].

- NADP⁺ (Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Phosphate): Cofactor, oxidized form.

- Substrate: Prochiral ketone.

- Isopropanol (IPA): Serves as co-substrate and solvent for cofactor regeneration [26].

- Potassium Phosphate Buffer: (e.g., 100 mM, pH 7.0) for maintaining optimal pH.

- Aqueous base solution: (e.g., 2M KOH or NaOH) for pH stat titration.

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: In a suitable reactor, charge the potassium phosphate buffer (90% of final volume), substrate (5-100 g/L final concentration), and NADP⁺ (0.1-1 mM final concentration) [26].

- Enzyme Addition: Add the KRED (typically 1-10 g/L loading) and IPA (5-20% v/v) to the reaction mixture [26].

- Process Control: Initiate the reaction with stirring. Maintain the temperature at 30-40°C. Use a pH stat to automatically titrate the reaction with a mild base (e.g., 2M KOH) to maintain the optimal pH (e.g., 7.0), as the reduction reaction consumes a proton [26].

- Reaction Monitoring: Monitor reaction progress by analytical methods (e.g., HPLC, GC) until the substrate is consumed (>99% conversion).

- Work-up and Isolation: Terminate the reaction by filtering off the enzyme (if immobilized) or extracting the product. The chiral alcohol can be isolated by standard techniques like extraction, distillation, or crystallization.

Protocol 2: Hydrolysis Reaction Catalyzed by a Hydrolase

Application Note: This protocol describes a general hydrolysis reaction (e.g., of an ester or amide) using a hydrolase, the largest class of industrial biocatalysts [20] [23]. The simplicity of these reactions, often not requiring external cofactors, makes them highly attractive for industrial scale-up.

Materials (Research Reagent Solutions):

- Hydrolase: Biocatalyst (e.g., lipase, protease, esterase; available from Novozymes, Amano Enzyme, etc.).

- Substrate: Ester, amide, or other hydrolyzable compound.

- Aqueous Buffer: (e.g., 50-200 mM phosphate or Tris buffer) selected for the enzyme's pH optimum.

- Co-solvent: (e.g., DMSO, acetonitrile, bio-derived solvents like limonene) may be used to solubilize hydrophobic substrates [28].

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: Dissolve or suspend the substrate in the appropriate aqueous buffer. For poorly water-soluble substrates, a water-miscible co-solvent (typically <20% v/v) can be added [28].

- Enzyme Addition: Add the hydrolase (whole cell, crude lysate, or purified immobilized preparation) to the reaction mixture.

- Process Control: Incubate the reaction with agitation at the recommended temperature (e.g., 25-37°C) and monitor the pH.

- Reaction Monitoring: Monitor reaction progress by TLC, HPLC, or GC until complete.

- Work-up and Isolation: The reaction can be worked up by filtration to recover the enzyme (if immobilized), followed by extraction to separate the acid and alcohol products. Products are typically purified by crystallization or chromatography.

Visualizing Biocatalytic Workflows

Ketoreductase Process Flow

Multi-Enzyme Cascade Design

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Materials for Biocatalytic Research

| Item | Function in Biocatalysis | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Ketoreductases (KREDs) / Alcohol Dehydrogenases (ADHs) | Catalyze the enantioselective reduction of ketones to chiral alcohols, a key reaction in chiral intermediate synthesis [26]. | Commercially available from Codexis, c-LEcta. Used with cofactor recycling systems (iPrOH/GDH) [26]. |

| Hydrolases | Catalyze the cleavage of bonds (e.g., ester, amide) by hydrolysis. The largest and most diverse class of industrial biocatalysts [20] [23]. | Lipases (e.g., Candida antarctica Lipase B), proteases, esterases. Widely used in detergents, organic synthesis, and resolution of racemates [20] [28]. |

| Transaminases | Catalyze the transfer of an amino group from an amino donor to a ketone or aldehyde, producing chiral amines [28]. | Critical for synthesizing pharmaceutical amines. Requires pyridoxal-5'-phosphate (PLP) as a cofactor. |

| Cofactors (NAD(P)H) | Essential electron carriers for redox enzymes like KREDs and ADHs. Required in catalytic, not stoichiometric, amounts [26]. | NADH, NADPH. Cost-effective processes require efficient in-situ regeneration using systems like iPrOH/GDH [26]. |

| Immobilized Enzymes | Enzymes physically confined or localized on an inert support material with retention of catalytic activity [24]. | e.g., Novozyme 435 (Immobilized CALB). Enhances stability, allows for reuse, and simplifies product separation and process intensification [28] [24]. |

| Bio-derived Solvents | Sustainable reaction media that can replace traditional organic solvents, reducing environmental impact and improving enzyme compatibility [28]. | Limonene, p-cymene, 2-MeTHF. Some, like limonene, have been shown to outperform hexane in certain enzymatic reactions [28]. |

From Discovery to Production: AI, Enzyme Engineering, and Real-World Pharma Applications

Harnessing AI and Machine Learning for Novel Enzyme Discovery and Functional Annotation

The transition of the chemical and pharmaceutical industries toward sustainable green manufacturing urgently requires innovative approaches to biocatalyst development [29]. Enzymes, nature's molecular machines, offer a promising path to reduced waste generation and lower energy consumption due to their inherent stereoselectivity and compatibility with cascade reactions [29]. However, natural enzymes rarely possess the efficiency and stability needed for industrial application, creating a critical bottleneck in utilizing biocatalysis for green chemistry processes.

Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) are revolutionizing enzyme discovery and functional annotation, moving beyond traditional labor-intensive methods like directed evolution [29] [30]. These data-driven approaches can predict enzyme function, stability, and activity from amino acid sequences, dramatically accelerating the identification and engineering of novel biocatalysts for sustainable chemical synthesis [31] [32]. This Application Note provides detailed protocols and frameworks for integrating AI and ML tools into enzyme discovery pipelines specifically for green chemistry applications.

AI Tools for Enzyme Functional Annotation

Functional annotation of enzymes using Enzyme Commission (EC) numbers provides a standardized system for classifying enzyme functions. Several AI tools have been developed to predict EC numbers from amino acid sequences, each employing distinct deep learning architectures to address this complex prediction task.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of AI-Based Enzyme Function Prediction Tools

| Tool | Architecture | Input Data | Coverage | Macro F1-Score | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLEAN-Contact [33] | Contrastive learning with ESM-2 & ResNet50 | Sequence + Contact maps | 5360 EC numbers | 0.566 (New-392) 0.525 (Price-149) | Integrates sequence and structural data; superior for understudied EC numbers |

| DeepECtransformer [34] [35] | Transformer layers | Amino acid sequence | 5360 EC numbers | 0.8093 (macro) | Identifies functional motifs; corrects mis-annotated EC numbers |

| CLEAN [31] | Contrastive learning | Amino acid sequence | N/A | N/A | Addresses dataset imbalance; identifies multi-functional enzymes |

| EpHod [36] | Attention-based neural network | Amino acid sequence | pH optimization | N/A | Predicts enzyme optimum pH; identifies critical residues |

The performance of these tools varies significantly across different enzyme classes. For instance, DeepECtransformer demonstrates lower performance for EC:1 class (oxidoreductases) due to inherent dataset imbalance, with this class having the lowest average number of sequences per EC number (average 4,352 sequences) compared to other classes (ranging from 6,819 for EC:3 to 16,525 for EC:6) [34] [35]. This performance gap highlights the importance of considering tool selection based on the specific enzyme class of interest.

CLEAN-Contact represents a significant advancement by integrating both amino acid sequence data and protein structural information through contact maps, achieving a 16.22% enhancement in precision and 12.30% increase in F1-score compared to CLEAN [33]. This framework employs a contrastive learning approach that minimizes embedding distances between enzymes sharing the same EC number while maximizing distances between enzymes with different EC numbers [33].

Protocol: Enzyme Function Prediction Using CLEAN-Contact

Objective: Predict EC numbers for uncharacterized enzyme sequences using the CLEAN-Contact framework.

Materials:

- Amino acid sequences in FASTA format

- CLEAN-Contact web interface or standalone package

- Computing resources (GPU recommended for large datasets)

Procedure:

- Sequence Preparation

- Obtain amino acid sequences for uncharacterized enzymes

- Validate sequence format and remove invalid characters

- For structural integration, generate contact maps using AlphaFold2 or ESMFold if experimental structures unavailable

Model Configuration

- Access CLEAN-Contact through web interface (publicly available) or local installation

- Select appropriate EC number selection algorithm:

- P-value algorithm for balanced precision-recall

- Max-separation algorithm for higher precision

Prediction Execution

- Input sequences into the prediction pipeline

- For sequences with known structures, enable the ResNet50 contact map analyzer

- For sequence-only input, rely on ESM-2 protein language model embeddings

Result Interpretation

- Review predicted EC numbers with confidence scores

- Identify potential multi-functional enzymes (multiple EC numbers)

- Cross-reference with known motifs and active site residues

- Export results for experimental validation

Validation Case Study: DeepECtransformer successfully corrected mis-annotated EC numbers in UniProtKB, including re-annotation of P93052 from Botryococcus braunii from L-lactate dehydrogenase (EC:1.1.1.27) to malate dehydrogenase (EC:1.1.1.37), which was subsequently confirmed through heterologous expression experiments [34] [35].

AI-Guided Enzyme Engineering Platforms

Beyond functional annotation, AI platforms are revolutionizing enzyme engineering through the integration of high-throughput experimental data generation and machine learning. These systems create accelerated feedback loops that significantly reduce the time required to develop industrially viable biocatalysts.

Table 2: Integrated AI-Experimental Platforms for Enzyme Engineering

| Platform/Study | Core Technologies | Throughput | Key Applications | Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cambridge Platform [29] | Droplet microfluidics, Deep sequencing, ML | >1 million variants/hour | Pharmaceutical enzyme cascades | HIV drug Islatravir synthesis |

| IBM Rxn+RoboRXN [32] | Multi-task transfer learning, Cloud platform | N/A | Biocatalyzed synthesis planning | Corrected errors in ground truth data |

| BRAIN Biocatalysts [37] | MetXtra platform, Fermentation scale-up | High-throughput screening | Industrial enzyme production | End-to-end development pipeline |

The Cambridge platform exemplifies this integrated approach, combining droplet microfluidics to test enzyme reactions at pico-litre scales (>1 million reactions per hour), deep sequencing to record sequence-function relationships, and machine learning models to predict improved mutations [29]. This workflow generates unique protein-specific data not available from sources like PDB or AlphaFold, which is crucial for accurate AI predictions [29].

Protocol: Ultrahigh-Throughput Enzyme Engineering with AI Integration

Objective: Engineer improved enzyme variants through integrated microfluidics, sequencing, and machine learning.

Materials:

- Droplet microfluidics system (commercial or custom)

- Next-generation sequencing platform (Illumina or Nanopore)

- Enzyme variant library (10^6-10^9 diversity)

- Fluorescent substrate for activity screening

- Computing infrastructure for ML training

Procedure:

- Library Design and Preparation

- Design variant library focusing on target regions identified by AI

- Generate DNA library using mutagenesis techniques

- Express variants in suitable host (e.g., E. coli)

Droplet Microfluidics Screening

- Encounter single cells expressing enzyme variants into droplets

- Add fluorescent substrate to detect enzymatic activity

- Sort droplets based on fluorescence intensity (activity)

- Recover hits for sequence analysis

Sequence-Function Mapping

- Extract DNA from sorted variants

- Perform deep sequencing (Illumina or Nanopore)

- Correlate variant sequences with activity data

- Build sequence-function dataset

Machine Learning Model Training

- Train predictive models on sequence-function data

- Use transformer architectures or convolutional neural networks

- Validate model predictions with held-out test sets

- Iterate library design based on model predictions

Case Study Application: This protocol was successfully applied to engineer a biocatalyst needed for sustainable production processes in the pharmaceutical industry, demonstrating the power of combining ultrahigh-throughput experimentation with AI-guided prediction [29].

Implementation Workflow for Industrial Applications

Translating AI predictions into industrially viable enzymes requires careful consideration of real-world operating conditions and scale-up parameters. The following workflow provides a systematic approach for implementing AI-discovered enzymes in green chemistry processes.

Critical Implementation Considerations:

Prediction vs. Performance Validation: Computationally promising enzymes frequently diverge from predictions in actual process conditions. Factors including solubility, cofactor requirements, and substrate inhibition must be empirically tested [37].

Scale-Up Bridge: Successful laboratory-scale performance (microscale fermentation) does not guarantee industrial viability. Enzyme production at 10L versus 10,000L scales presents significantly different challenges in yield, purification, and cost-effectiveness [37].

Green Chemistry Metrics: Throughout the workflow, monitor key green chemistry metrics including atom economy, E-factor (environmental factor), energy consumption, and waste reduction to ensure alignment with sustainability goals.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for AI-Guided Enzyme Discovery

| Category | Specific Items | Function/Application | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| AI Prediction Tools | CLEAN-Contact, DeepECtransformer, EpHod, CLEAN | Enzyme function, EC number, and optimum pH prediction | Web interfaces available; some require local installation with GPU acceleration |

| High-Throughput Screening | Droplet microfluidics chips, Fluorescent substrates, Next-gen sequencing kits | Ultrahigh-throughput activity screening and sequence-function mapping | Enables testing of >1 million variants/hour; requires specialized equipment [29] |

| Expression Systems | Microbial production strains (E. coli, yeast), Induction reagents, Fermentation media | Enzyme production for characterization and scale-up | Critical for translating AI predictions to physical enzyme quantities [37] |

| Analytical Tools | HPLC/MS systems, Spectrophotometers, Activity assays | Quantitative analysis of enzyme activity and reaction products | Essential for validating AI predictions and optimizing process parameters |

| Process Optimization | Design of Experiment (DoE) software, Bioreactors, Purification systems | Scaling enzyme production from lab to industrial scale | Required to address the "scale-up bottleneck" between discovery and application [37] |

The integration of AI and machine learning with experimental enzyme engineering is transforming the development of biocatalysts for green chemistry applications. Tools like CLEAN-Contact and DeepECtransformer provide accurate functional annotation, while integrated platforms combining droplet microfluidics with machine learning enable rapid optimization of enzyme properties. Successfully harnessing these technologies requires addressing the critical transition from AI prediction to industrial application through rigorous experimental validation and scale-up processes. As these AI tools continue to evolve and incorporate more diverse data types, they will dramatically accelerate the discovery and implementation of novel enzymes for sustainable chemical synthesis, ultimately contributing to the transition of the chemical and pharmaceutical industries toward greener manufacturing processes.

Application Note: Directed Evolution for Sustainable Biocatalysis

Directed evolution stands as a cornerstone of modern enzyme engineering, providing a robust strategy for optimizing biocatalysts to meet the demanding requirements of industrial processes, particularly in green chemistry and pharmaceutical synthesis. This approach mimics natural evolution in a laboratory setting through iterative rounds of mutagenesis and screening, but on a vastly accelerated timescale. It enables researchers to enhance key enzyme properties such as catalytic activity, enantioselectivity, thermostability, and solvent tolerance without requiring prior structural knowledge. The power of directed evolution is exemplified by its successful application in engineering enzymes for the sustainable synthesis of cardiac drugs, where it has yielded biocatalysts with significantly improved efficiency and environmental compatibility [38].

Quantitative Performance Metrics

The success of a directed evolution campaign is quantitatively evaluated by measuring improvements in key biochemical and process parameters. The table below summarizes typical performance enhancements achieved through directed evolution of enzymes for cardiac drug synthesis, demonstrating its profound impact on catalytic proficiency and sustainability metrics [38].

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Enhancements from Directed Evolution of Cardiac Drug Synthesis Enzymes

| Parameter | Base/Mutant | Performance | Enhancement vs. Baseline |

|---|---|---|---|

| Catalytic Turnover (k_cat) | Variant | Elevated catalytic turnover | 7-fold increase |

| Catalytic Proficiency (kcat/Km) | Variant | Boosted proficiency | 12-fold increase |

| Substrate Conversion | CYP450-F87A | Substrate conversion | 97% |

| Enantioselectivity | KRED-M181T | Enantioselectivity | 99% |

| Thermostability (Melting Temp) | Variant | Improved resistance | T_m +10-15 °C |

| Solvent Tolerance | Variant | Activity in co-solvent | 85% activity in 30% ethanol |

| Process E-factor | Biocatalytic Process | Waste generation | 3.7 (vs. 15.2 conventional) |

| CO2 Emissions | Biocatalytic Process | Emission reduction | 50% decrease vs. conventional |

| Energy Usage | Biocatalytic Process | Energy reduction | 45% decrease |

| Atom Economy | Biocatalytic Process | Atom economy | 85-92% |

Experimental Protocol: Laboratory-Scale Directed Evolution

Objective: To generate and identify improved enzyme variants with enhanced activity and stability for application in green synthesis pathways.

Materials:

- Parent Enzyme Gene: Cloned in an appropriate expression vector (e.g., pET series).

- Mutagenesis Kit: Commercial kit for error-prone PCR (e.g., Genemorph II kit) or DNA shuffling.

- Host Strain: High-efficiency competent cells for library construction (e.g., NEB 5-alpha) and protein expression (e.g., E. coli BL21(DE3)).

- Screening Substrate: A reliable substrate for the reaction of interest, preferably coupled to a colorimetric or fluorometric readout for high-throughput screening.

- Growth Media: LB or TB media with appropriate antibiotics.

- Microtiter Plates: 96-well or 384-well deep-well plates for culture and assay.

- Thermocycler, Plate Reader, and Liquid Handling System.

Procedure:

- Library Construction:

- Perform error-prone PCR on the parent gene using mutagenic conditions (e.g., unbalanced dNTPs, Mn2+) to introduce random mutations. Alternatively, use gene recombination methods for DNA shuffling.

- Purify the mutated PCR product and clone it into the expression vector via restriction digestion/ligation or homologous recombination.

- Transform the constructed library into a cloning-efficient host strain. Plate on selective agar to determine library size. A library of 104-106 clones is typically desired.

High-Throughput Expression and Screening:

- Pick individual colonies into deep-well plates containing growth medium and induce protein expression.

- After growth, lyse cells either chemically (e.g., lysozyme, detergents) or physically (e.g., freeze-thaw, sonication).

- Transfer a lysate aliquot to a new assay plate containing the screening substrate.

- Monitor the reaction using a plate reader. Normalize activity signals to cell density (OD600) to account for expression variations.

Hit Identification and Validation:

- Select the top 0.1-1% of variants showing the highest activity or desired selectivity for sequence analysis.

- Isolate the plasmid DNA from these hits and retransform into a fresh expression host for validation in small-scale cultures to confirm the improved phenotype.

Iteration:

Data Analysis: Calculate fold-improvement for each variant relative to the parent enzyme. Sequence confirmed hits to identify mutations responsible for the improved properties.

Application Note & Protocol: Computational Stability Design

While directed evolution is powerful, it can sometimes face challenges with stability-activity trade-offs. Computational stability design addresses this by proactively engineering enzymes for enhanced stability without compromising, and often even enhancing, catalytic function. This approach leverages a combination of bioinformatics and energy-based protein design algorithms. A key methodology involves identifying catalytic hotspots, often via NMR chemical shift perturbations upon binding transition-state analogues, and then using computational design tools like FuncLib to predict stabilizing mutations at these positions. This method has been successfully applied to a de novo Kemp eliminase, resulting in variants with a ~3-fold enhancement in activity (k_cat ~ 1700 s-1) and significantly increased denaturation temperatures, creating one of the most proficient designed enzymes for this reaction [40].

Experimental Protocol: FuncLib-Guided Stability Design

Objective: To design and experimentally characterize stabilized enzyme variants using a computational/phylogenetic approach focused on catalytic hotspots.

Materials:

- Protein Structure: A high-resolution crystal structure or a high-quality predicted structure (e.g., from AlphaFold2) of the target enzyme.

- FuncLib Web Server: (https://funclib.weizmann.ac.il)

- Cloning, Expression, and Purification Materials: As listed in Section 1.3.

- Differential Scanning Fluorometry (DSF) Setup: Real-time PCR instrument and a fluorescent dye like SYPRO Orange.

- Kinetics Assay Components: Substrates and buffers for measuring enzyme activity (kcat, Km).

Procedure:

- Hotspot Identification:

- Express and purify the wild-type enzyme.

- Use NMR spectroscopy to monitor chemical shift perturbations upon titration with a transition-state analogue (TSA) or a tight-binding inhibitor. Residues showing significant perturbations are defined as catalytic hotspots [40].

- Alternative Computational Method: If NMR is unavailable, perform an interaction network analysis of the enzyme's active site to predict residues critical for catalysis [40].

Computational Design with FuncLib:

- Submit the protein structure and the list of identified hotspot residues to the FuncLib server.

- FuncLib uses the Rosetta design software combined with phylogenetic analysis to generate and rank multiple-point mutant sequences predicted to be stable and functional.

- Select the top 20-50 ranked variants for experimental testing [40].

Gene Synthesis and Cloning:

- Synthesize genes encoding the selected FuncLib variants.

- Clone them into an expression vector.

Experimental Characterization:

- Expression and Purification: Express and purify the wild-type and variant proteins using standard protocols (e.g., affinity chromatography).

- Thermal Stability Assessment:

- Use DSF (Thermofluor assay) to determine the melting temperature (Tm).

- Prepare samples: 5 µM protein, 5X SYPRO Orange dye in a suitable buffer.

- Run in a real-time PCR instrument with a temperature gradient from 25°C to 95°C.

- Calculate Tm from the inflection point of the unfolding curve. An increase of +5°C or more indicates significant stabilization [40].

- Catalytic Activity Assay:

- Under saturating substrate conditions, measure the initial velocity of the reaction for each variant.

- Determine kcat and Km to calculate catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km).

- Compare these values to the wild-type enzyme to confirm functional integrity or enhancement.

Data Analysis: Correlate the computed Rosetta scores from FuncLib with the experimentally determined Tm and kcat/K_m values. This validation helps refine future computational predictions.

Application Note & Protocol: Machine-Learning Guided Enzyme Engineering

The integration of machine learning (ML) is revolutionizing enzyme engineering by enabling the navigation of sequence-function landscapes with unprecedented efficiency. This data-driven approach is particularly powerful for multi-objective optimization, such as engineering enzyme promiscuity for a range of substrates. Conventional methods that screen for single objectives generate limited data, missing underlying sequence-function relationships. ML-guided platforms overcome this by using high-throughput experimental data to train models that can predict beneficial mutations across a wide chemical space. For instance, an ML-guided, cell-free platform was used to engineer the amide synthetase McbA. By testing 1,217 mutants in nearly 11,000 reactions, researchers trained a model that successfully designed variants with improved amide bond formation for nine different pharmaceutical compounds simultaneously [41].

Experimental Protocol: ML-Guided Engineering for Substrate Promiscuity

Objective: To map a sequence-fitness landscape and use ML to engineer enzyme variants with enhanced activity across multiple substrates.

Materials:

- Cell-Free Protein Synthesis (CFPS) System: A reconstituted transcription-translation system, such as PURExpress.

- Mutant Library: A defined library of enzyme variants (e.g., site-saturation mutagenesis library).

- Substrate Panel: A set of target compounds for which enzymatic activity is desired.

- High-Throughput Analytical Method: LC-MS or HPLC for quantifying reaction products.

- Computing Resources: Access to computing hardware and software/libraries for machine learning (e.g., Python, Scikit-learn, PyTorch).

Procedure:

- High-Throughput Data Generation:

- Use a CFPS system to express the library of enzyme variants directly in a microtiter plate. This bypasses cellular constraints and allows direct coupling of expression to assay.

- For each variant, assay activity against each substrate in the panel. This generates a large dataset linking sequence (variant) to function (fitness across multiple reactions) [41].

Machine Learning Model Training:

Prediction and Validation:

- Use the trained model to predict the fitness of a vast number of in silico generated enzyme variants.

- Select a set of top-predicted variants for gene synthesis and experimental validation.

- Characterize these validated variants using purified protein and standard kinetic assays to confirm the model's predictions.

Data Analysis: Evaluate model performance using metrics like Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) and correlation coefficients (R²) on a held-out test set of data. The ultimate validation is the successful experimental confirmation of top-predicted variants.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents and Computational Tools for Advanced Enzyme Engineering

| Item Name | Function/Application | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Error-Prone PCR Kit | Introduces random mutations throughout the gene to create diversity for directed evolution. | Genemorph II Random Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent). |

| Cell-Free Protein Synthesis (CFPS) System | Enables high-throughput, coupled expression and screening of enzyme libraries without cellular constraints. | PURExpress (NEB) [41]. |

| FuncLib Web Server | Computational tool that designs and ranks enzyme variants with multiple mutations for stability and function. | Input: Structure & hotspot residues. Output: Ranked variant list [40]. |

| SYPRO Orange Dye | Fluorescent dye used in Differential Scanning Fluorometry (DSF) to measure protein thermal stability (T_m). | Used at 5-10X concentration in DSF assays. |

| Language Model Embeddings | Numerical representations of protein sequences used as features for machine learning models. | ESM (Evolutionary Scale Modeling) embeddings [42] [43]. |

| Transition-State Analogue (TSA) | A stable molecule mimicking the transition state of a reaction; used for mechanistic studies and hotspot identification via NMR. | Critical for guiding computational design by defining the active site geometry [40]. |

| EnzyExtractDB | A large-scale database of enzyme kinetics data extracted from scientific literature using AI, useful for training predictive models. | Contains over 218,000 enzyme-substrate-kinetics entries [44]. |

Implementing Multi-Enzyme Cascades and Continuous Flow Biocatalysis

The integration of multi-enzyme cascades with continuous flow biocatalysis represents a paradigm shift in sustainable chemical synthesis, particularly for the pharmaceutical industry. This approach combines the high selectivity and mild reaction conditions of enzymatic catalysis with the enhanced mass/heat transfer, process control, and scalability of continuous flow systems [45]. The technology enables the creation of efficient, telescoped synthetic routes for active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), fine chemicals, and natural products, aligning with the core principles of green chemistry by minimizing waste, energy consumption, and hazardous reagents [46]. This application note provides a comprehensive overview of the current status, detailed protocols, and practical implementation strategies to guide researchers and drug development professionals in harnessing this powerful technology.

Key Principles and Advantages

Continuous flow biocatalysis involves pumping reactant solutions through reactors containing immobilized enzymes or whole cells in a continuous stream [47]. When applied to multi-enzyme cascades—where two or more enzymes work sequentially—this setup allows for the compartmentalization of incompatible biocatalysts or reaction steps, overcoming significant limitations of traditional batch processes [48].

Table 1: Comparison of Batch vs. Continuous Flow Biocatalysis for Multi-Enzyme Cascades

| Parameter | Batch Biocatalysis | Continuous Flow Biocatalysis |

|---|---|---|

| Reaction Control | Limited | Precise control over residence time, temperature, and pressure [47] |

| Catalyst Reusability | Difficult recovery and reuse | Immobilized enzymes in packed-bed reactors enable multiple reuses [49] |

| Incompatible Steps | Challenging to combine in one pot | Enzymes can be segregated in sequential modules [48] |

| Space-Time Yield | Often lower | Can be significantly improved (e.g., 11-fold increase reported) [49] |

| Process Intensification | Limited | Enabled by telescoping steps and in-line purification [47] |

| Automation Potential | Low | High, with options for real-time monitoring and control [45] |

The primary advantages of merging these technologies include:

- Overcoming Incompatibility: Enzymes with differing optimal pH, temperature, or co-factor requirements, or those whose substrates or products inhibit each other, can be physically separated into distinct reactor modules [48]. A notable example is the use of galactose oxidase (GOase) with transaminases or imine reductases; in batch, amines inhibit GOase's copper active site, but in a compartmentalized flow system, these cascades proceed with >95% conversion [48].

- Enhanced Efficiency and Stability: Immobilization, a cornerstone of flow biocatalysis, often improves enzyme stability and tolerance to organic solvents and elevated temperatures [47]. It also simplifies catalyst recovery and reuse, dramatically improving productivity and reducing costs [49].

- Process Greenness: Flow systems reduce waste by minimizing purification steps between reactions and enabling high-concentration processing, which addresses a key criticism of traditional aqueous biocatalysis that often operates at dilute, wasteful concentrations [50].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: General Assembly of a Continuous Flow System for Biocatalysis

This protocol describes the assembly of a modular continuous flow system from readily available components, adapted for biocatalytic applications [51].

Materials:

- Syringe pumps or peristaltic pumps

- PFA (perfluoroalkoxy) tubing or metal reactors

- Fittings and connectors (e.g., PEEK, stainless steel)

- Back-pressure regulator (BPR)

- Solid supports for immobilization (e.g., EziG affinity resins, amino-functionalized carriers)

Procedure:

- Reactor Assembly: Connect the reactor tubing (e.g., PFA) to the pump outlet using appropriate fittings. For packed-bed reactors, pack the immobilized enzyme preparation into a column or cartridge and connect it to the flow path.

- System Integration: Connect the reactor outlet to the back-pressure regulator, which is essential for maintaining liquid phase by preventing solvent evaporation, especially when operating above the boiling point [47].

- System Priming: Before introducing the substrate solution, prime the entire flow path with the reaction buffer to remove air bubbles and wet the immobilized enzyme.

- Reaction Execution: Load the substrate solution into a syringe or reservoir and pump it through the system at the desired flow rate, which determines the residence time.

- Product Collection: Collect the effluent from the BPR outlet. Monitor the reaction progress via in-line or off-line analytical methods (e.g., HPLC, GC).

Troubleshooting:

- Clogging: If solids precipitate, consider introducing a co-solvent, performing in-line liquid-liquid separation, or using sonication to agitate the reactor [47] [51].

- Pressure Spikes: These can indicate clogging or fouling from cellular debris (in whole-cell systems). Using filters or pre-columns can mitigate this [52].

Protocol 2: Continuous Synthesis of UDP-GlcNAc via a Two-Enzyme Cascade