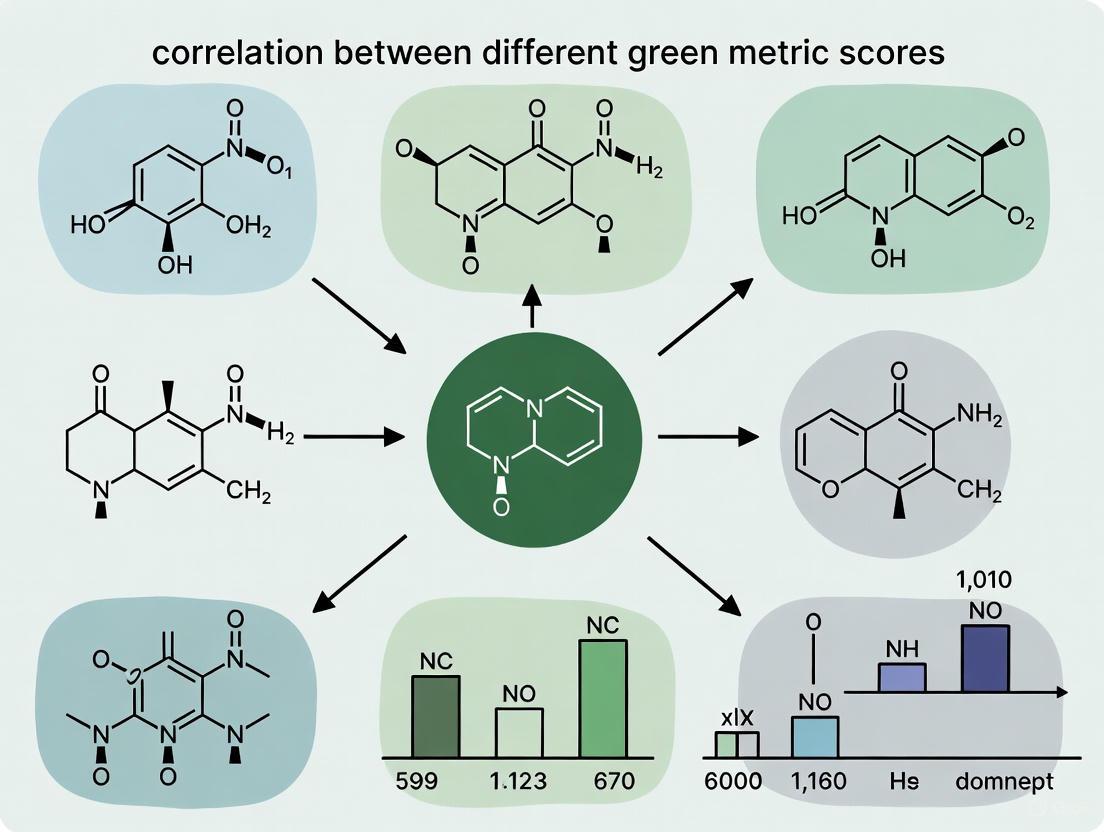

Beyond Single Scores: Understanding the Correlations Between Green Metrics for Sustainable Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and pharmaceutical professionals on the interrelationships between various green chemistry metrics.

Beyond Single Scores: Understanding the Correlations Between Green Metrics for Sustainable Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and pharmaceutical professionals on the interrelationships between various green chemistry metrics. It explores the foundational principles of established metrics like E-Factor and Process Mass Intensity (PMI), details their methodological application in pharmaceutical processes, and addresses critical challenges such as metric limitations and potential greenwashing. By presenting validation frameworks and comparative analyses, including correlations with Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), it offers a practical guide for selecting, interpreting, and optimizing green metrics to drive genuine sustainability improvements in drug development.

The Green Metrics Landscape: Core Principles and Key Indicators for Pharmaceutical Chemistry

Defining Green Chemistry Metrics and Their Role in Sustainable Drug Development

The pharmaceutical industry, while vital for global health, is a significant contributor to environmental burden, characterized by extensive waste generation and high energy consumption. Global active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) production, estimated at 65-100 million kilograms annually, generates approximately 10 billion kilograms of waste, with disposal costs reaching around $20 billion [1]. Green chemistry metrics provide the quantitative framework necessary to measure, manage, and mitigate this environmental impact. These metrics transform the conceptual 12 Principles of Green Chemistry into actionable, measurable parameters that guide drug development professionals toward more sustainable practices [2]. By applying these metrics, researchers can make informed decisions that balance environmental responsibility with economic viability, creating a new competitive frontier in generic drug development where the greenest process often proves to be the most profitable [3].

Foundational Green Chemistry Metrics

Core Mass-Based Metrics

Mass-based metrics form the fundamental quantitative backbone of green chemistry assessment, focusing on the efficiency of material utilization in chemical processes.

Table 1: Core Mass-Based Green Chemistry Metrics

| Metric Name | Calculation Formula | Interpretation | Ideal Value | Pharmaceutical Industry Typical Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E-Factor [4] | Total waste (kg) / Product (kg) | Lower values indicate less waste generation | Closer to 0 | 25 to >100 |

| Process Mass Intensity (PMI) [5] | Total materials (kg) / Product (kg) | Direct measure of resource efficiency | Closer to 1 | >100 (before optimization) |

| Atom Economy (AE) [3] | (MW of product / MW of all reactants) × 100% Theoretical efficiency of incorporating atoms into product | Higher percentages indicate better atomic utilization | 100% | Varies widely by synthesis |

| Effective Mass Yield (EMY) [2] | (Mass of product / Mass of non-benign reagents) × 100% | Percentage of desired product relative to hazardous materials used | 100% | Application-specific |

The relationship between E-Factor and PMI is mathematically defined: E-Factor = PMI - 1 [4]. This interconnectedness allows researchers to select the most appropriate metric for their specific assessment needs. The pharmaceutical industry typically exhibits higher E-Factor values (25 to >100) compared to bulk chemicals (<1-5) or oil refining (<0.1), primarily due to multi-step syntheses and stringent purity requirements [4].

Advanced Assessment Metrics

Beyond basic mass calculations, advanced metrics provide more comprehensive environmental and human health impact assessments.

Table 2: Advanced Green Chemistry Assessment Metrics

| Metric Name | Scope of Assessment | Key Parameters Measured | Output Format | Primary Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analytical Method Greenness Score (AMGS) [6] | Analytical procedures | Toxicity, energy consumption, waste generation | Numerical score | Method development and validation |

| Eco-Scale [4] | Synthetic processes | Yield, cost, safety, purification, energy consumption | Penalty point system | Organic synthesis evaluation |

| Complex-GAPI (C-GAPI) [6] | Comprehensive process evaluation | Chemical hazards, energy consumption, waste management | Pictorial diagram | Comparative greenness assessment |

| Ecological Footprint (EF) [4] | Broad environmental impact | Water, energy, raw materials, carbon emissions, land use | Global hectares (gha) | Macro-level environmental impact |

The Analytical GREENNESS (AGREE) metric exemplifies the evolution toward specialized assessment tools, designed specifically for evaluating the environmental impact of analytical methods [6]. Meanwhile, the Ecological Footprint metric has expanded to include specialized variants: Chemical Footprint, Material Footprint, Energy Footprint, Land Footprint, and Water Footprint, enabling targeted assessments of specific environmental concerns [4].

Metric Implementation and Workflow Framework

Strategic Implementation Framework

Successful implementation of green chemistry metrics requires a structured approach that aligns with drug development milestones. The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for applying green chemistry metrics throughout the drug development lifecycle:

Experimental Protocols for Metric Assessment

E-Factor and PMI Determination Protocol

Objective: Quantify waste generation and resource efficiency for chemical processes [4].

Materials:

- Analytical balance (±0.0001 g precision)

- Process documentation (batch records, synthesis procedures)

- Waste stream characterization equipment

Procedure:

- Record the mass of all input materials (reactants, solvents, catalysts, reagents)

- Document the mass of the final purified product

- Calculate total waste: Σ(mass inputs) - mass product

- Compute E-Factor: Total waste (kg) / Product mass (kg)

- Compute PMI: Total inputs (kg) / Product mass (kg)

- Repeat for three independent batches for statistical significance

Validation: Cross-verify with material balance closure ≥95%

Greenness Assessment for Analytical Methods (AGREE Protocol)

Objective: Evaluate the environmental impact of analytical procedures used in drug quality control [6].

Materials:

- Analytical method documentation (HPLC, UPLC, IR specifications)

- Solvent safety data sheets

- Energy consumption monitoring equipment

Procedure:

- Identify all chemicals consumed per analysis (mobile phase, standards, reagents)

- Classify chemicals according to environmental and safety hazards

- Quantify energy consumption of instrumentation during typical run cycle

- Calculate waste generation volume per sample

- Apply penalty points for hazardous materials and energy-intensive steps

- Compute overall greenness score using AGREE calculator software

Application: Particularly valuable for comparing bioanalytical methods like the DRIFTS infrared spectroscopic method versus traditional HPLC for drug quantification [6].

Case Studies in Pharmaceutical Applications

Antibody-Drug Conjugate Synthesis Optimization

A breakthrough demonstration of green metrics in action comes from Merck's transformation of antibody-drug conjugate Sacituzumab tirumotecan (MK-2870) production. The innovative approach streamlined a 20-step synthesis into just three OEB-5 handling steps derived from a natural product, resulting in remarkable environmental and efficiency improvements [5]:

- Process Mass Intensity reduction of ~75%

- Chromatography time cut by over 99%

- Enabled faster, greener, more scalable access to life-saving cancer treatments

This case exemplifies how green chemistry principles drive innovation while simultaneously improving efficiency, scalability, and sustainability in complex pharmaceutical manufacturing [5].

Agricultural Chemical Development

Corteva Agriscience demonstrated the application of green metrics in developing Adavelt active fungicide. The team systematically applied metric analysis to achieve [5]:

- Elimination of unnecessary protecting groups and steps

- Avoidance of precious metals

- Replacement of hazardous reagents with greener alternatives

- Creation of an efficient, cost-effective process protecting over 30 crops against 20 major plant diseases

This achievement highlights the role of green metrics in minimizing waste and environmental impact while maintaining commercial viability and efficacy.

Retrospective Greenness Assessment

A novel approach to green chemistry implementation involves retrospective assessment of existing methods. A case study on baricitinib (a Janus kinase inhibitor) demonstrated how multitool greenness assessment of older analytical methods can develop greener alternatives [6]. The study revealed:

- Diffuse Reflectance Infrared Fourier Transform Spectroscopy (DRIFTS) provided a greener alternative to traditional chromatography methods

- Elimination of sophisticated sample preparation requirements

- Reduced resource demand, overall developmental time, and method failure

- Maintained acceptable linearity, accuracy, and precision

This approach bridges practical challenges and gaps in greenness assessment, raising awareness in the analytical community about adopting greenness metrics for both newly developed and existing methods [6].

Emerging Technologies and Computational Approaches

AI and Machine Learning in Green Chemistry

The ACS Green Chemistry Institute Pharmaceutical Roundtable has recognized the growing importance of computational tools in green chemistry implementation, establishing a dedicated "Data Science and Modeling for Green Chemistry" award for 2026 [7]. These computational approaches include:

- Predictive tools for designing greener or safer reagents, processing conditions, or reaction outcomes

- AI platform technologies with wide application across the pharmaceutical industry

- In silico approaches that minimize experimentation to arrive at superior reaction conditions

These tools demonstrate compelling environmental, safety, and efficiency improvements over current technologies while enabling more accurate prediction of green metric outcomes before laboratory implementation [7].

Continuous Flow and Process Intensification

Advanced process intensification technologies, particularly continuous-flow API synthesis, are emerging as central to greener pharmaceutical manufacturing [1]. When combined with green metrics for evaluation, these approaches offer:

- Significant reduction in Process Mass Intensity

- Improved energy efficiency through better heat transfer

- Enhanced safety through smaller reactor volumes

- Reduced solvent consumption and waste generation

The integration of real-time analytical monitoring (PAT - Process Analytical Technology) aligns with the 11th Principle of Green Chemistry while providing continuous data for green metric calculations [3].

The Researcher's Toolkit for Green Metric Implementation

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Green Chemistry Implementation

| Tool Category | Specific Tools/Resources | Function in Green Chemistry | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment Software | AGREE Calculator, HPLC-EAT, EATOS | Quantitative greenness scoring | Method development, process optimization |

| Solvent Selection Guides | ACS GCI Pharmaceutical Roundtable Solvent Guide | Identify safer solvent alternatives | Reaction design, purification optimization |

| Catalyst Databases | Biocatalyst screening kits, immobilized catalyst libraries | Enable catalytic versus stoichiometric processes | Reduction of E-Factor, improved atom economy |

| Process Analytical Technology | In-line IR, UV, Raman probes | Real-time reaction monitoring for pollution prevention | Process control, impurity minimization |

| Metric Calculation Tools | PMI calculators, E-Factor spreadsheets | Quantitative assessment of process greenness | Benchmarking, continuous improvement |

Green chemistry metrics have evolved from theoretical concepts to essential tools for sustainable drug development. The correlation between different green metric scores provides researchers with actionable insights to drive continuous improvement in pharmaceutical processes. As the industry faces increasing pressure to mitigate its environmental footprint while maintaining economic viability, these metrics offer a pathway to reconcile these seemingly competing priorities.

The strategic implementation of green chemistry metrics—from early route selection through commercial manufacturing—enables drug development professionals to make data-driven decisions that demonstrate measurable environmental benefits. The case studies presented confirm that applying green chemistry principles through quantitative metrics not only improves environmental outcomes but also drives innovation, reduces costs, and creates more efficient manufacturing processes.

Future advancements in green chemistry metrics will likely involve greater integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning, more sophisticated lifecycle assessment approaches, and standardized reporting frameworks across the pharmaceutical industry. As these tools continue to evolve, they will further enable researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to design inherently sustainable pharmaceutical processes that align with the broader goals of sustainable development.

The following table summarizes the fundamental differences between mass-based and impact-based green chemistry metrics, which are essential for researchers and drug development professionals to understand when assessing process sustainability.

| Characteristic | Mass-Based Metrics | Impact-Based Metrics |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Measure material efficiency and mass flows [8] | Measure environmental, health, and resource consequences [8] |

| Primary Data Input | Mass of inputs (reactants, solvents) and outputs (product, waste) [9] [8] | Emissions data, toxicity profiles, energy consumption, life cycle inventory data [9] [8] |

| Typical Output | Mass ratio (e.g., kg waste/kg product); Percentage [9] | Impact score (e.g., CO₂-equivalent kg); Retained Environmental Value (REV) [10] [8] |

| System Boundary | Often limited (e.g., gate-to-gate); can be expanded (cradle-to-gate) [11] | Holistic, frequently cradle-to-grave, encompassing the entire life cycle [11] [8] |

| Key Limitation | Ignores material toxicity, energy use, and supply-chain impacts [9] [8] | Data-intensive; requires complex modeling and can be resource-heavy [9] [8] |

Experimental Correlation Analysis: Measuring the Divide

A 2025 study systematically analyzed the correlation between mass intensities and Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) environmental impacts, providing critical quantitative evidence of the performance gap between these metric types [11].

Experimental Protocol: Correlation Assessment

- Objective: To determine if and with which system boundaries mass intensities can reliably approximate LCA environmental impacts [11].

- Methodology: Spearman correlation coefficients were calculated between sixteen LCA environmental impacts (e.g., climate change, water use, toxicity) and eight different mass intensities with varying system boundaries [11].

- Materials & Data Source: The study evaluated 106 chemical productions using life-cycle inventory data from the ecoinvent database [11].

- Metric Variants: The eight mass intensities included one gate-to-gate Process Mass Intensity (PMI) and seven Value-Chain Mass Intensities (VCMI) with progressively expanded cradle-to-gate boundaries [11].

- Key Finding: Expanding the system boundary from gate-to-gate to cradle-to-gate strengthened correlations for fifteen of the sixteen environmental impacts. However, different environmental impacts were approximated by distinct sets of key input materials, confirming that a single mass-based metric cannot fully capture the multi-criteria nature of environmental sustainability [11].

Case Study Protocol: Solvent Circularity Assessment

A separate case study within a Swiss chemical plant directly compared mass-based and impact-based circularity indicators for solvent management, yielding starkly different results [10].

- Objective: To quantify the difference between mass-based and impact-based circularity assessments in a real-world industrial setting [10].

- Methodology: Researchers combined Material Flow Analysis (MFA) to track solvent masses with Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) to quantify environmental impacts [10].

- Key Indicators:

- Results: The company achieved a mass-based recycling rate of over 95%, suggesting near-complete circularity. In contrast, the impact-based REV was only about 52%, revealing that the recycled solvents retained just half of their original environmental value and highlighting a significant performance gap [10].

Conceptual Workflow and Decision Pathway

The diagram below illustrates the fundamental logical relationship between mass-based and impact-based assessment approaches, explaining why their results can diverge.

For scientists implementing these metrics in drug development, the following tools and resources are critical.

| Tool / Resource | Function | Relevant Metric Type |

|---|---|---|

| PMI Calculator [12] | Calculates Process Mass Intensity to benchmark process "greenness". | Mass-Based |

| ecoinvent Database [11] | Provides life-cycle inventory data for upstream materials and processes. | Impact-Based |

| AGREE Software [8] | Computational tool for calculating multiple green chemistry metrics. | Both |

| CHEM21 Toolkit [8] | A suite of metrics for measuring the environmental impact of key chemistries. | Both |

| USEtox Model [8] | A scientific consensus model for characterizing human and ecotoxicological impacts. | Impact-Based |

The fundamental divide between mass-based and impact-based metrics stems from what they measure: mass flows versus environmental mechanisms. While mass-based metrics like PMI and E-Factor are simple, accessible, and excellent for internal benchmarking and driving waste reduction, they lack the comprehensiveness to fully assess environmental sustainability [9] [8]. Impact-based metrics, grounded in LCA, provide a multi-faceted and holistic view but demand significantly more data and expertise [11] [10].

The research shows that expanding the boundaries of mass-based metrics improves their correlation with impact-based results, but the relationship is not perfect [11]. Relying solely on mass-based metrics risks optimizing for reduced mass without addressing critical issues like toxicity or carbon intensity, especially problematic during the transition to a defossilized chemical industry [11] [10]. Therefore, the most robust approach for drug development professionals is to use mass-based metrics for rapid screening and initial process guidance, while reserving impact-based LCA for definitive environmental assessments of critical processes and claiming genuine green innovations [11] [10].

The adoption of green chemistry principles in research and industry has necessitated the development of quantitative metrics to evaluate the environmental impact and efficiency of chemical processes. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, core mass metrics provide indispensable tools for measuring process sustainability, guiding optimization efforts, and making informed decisions during route selection and development. These metrics operationalize the principles of green chemistry by providing standardized, quantitative measures that enable objective comparison between synthetic pathways and facilitate the identification of areas for improvement. The most fundamental of these metrics—Atom Economy (AE), E-Factor, and Process Mass Intensity (PMI)—form the cornerstone of green chemistry assessment, each offering a unique perspective on material utilization and waste generation [8] [4].

The pharmaceutical industry, in particular, faces significant challenges regarding waste generation due to multi-step syntheses and stringent purity requirements, making these metrics especially valuable for drug development professionals [4]. Understanding the theoretical foundations, calculation methodologies, and appropriate applications of each metric is crucial for their effective implementation in research and development settings. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these three core mass metrics, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies, to equip professionals with the knowledge needed to apply these tools effectively in their work toward sustainable chemical processes.

Metric Definitions and Theoretical Foundations

Atom Economy (AE)

Atom Economy is a theoretical metric that evaluates the efficiency of a chemical reaction by measuring the proportion of atoms from the reactants that are incorporated into the desired product [13] [8]. Introduced by Barry Trost in 1991, this concept emphasizes designing synthetic methods that maximize the use of raw materials while minimizing waste at the molecular level [13] [14]. It is calculated as the molecular weight of the desired product divided by the sum of the molecular weights of all reactants in the stoichiometric equation, expressed as a percentage [13] [8]:

Atom Economy (%) = (Molecular Weight of Desired Product / Σ Molecular Weights of All Reactants) × 100%

Atom Economy serves as a theoretical benchmark for reaction efficiency, independent of practical factors such as reaction yield or the use of auxiliary substances [8]. Its primary value lies during the early design phase of chemical processes, where it helps researchers select synthetic routes that inherently generate less waste [13]. A reaction with 100% atom economy represents an ideal scenario where all reactant atoms are incorporated into the final product, as seen in simple addition reactions [13]. In contrast, reactions with poor atom economy, such as substitutions or eliminations, inevitably generate stoichiometric byproducts [13].

E-Factor

The E-Factor (Environmental Factor) provides a practical measure of the waste generated in a process [4]. Developed by Roger Sheldon in 1992, it quantifies the total waste produced per kilogram of product [8] [4]. Unlike Atom Economy, which is a theoretical calculation, E-Factor accounts for the actual waste generated during a process, including reagents, solvents, and other materials used in reaction and workup [4]:

E-Factor = Total Mass of Waste (kg) / Mass of Product (kg)

The E-Factor provides a direct measure of environmental impact in terms of waste generation, with lower values indicating more sustainable processes [4]. Its calculation can include or exclude water, depending on the application context [4]. This metric highlights the significant waste generation in different industrial sectors, with the pharmaceutical industry typically showing the highest E-Factors (25 to >100), followed by fine chemicals (5 to >50), bulk chemicals (<1 to 5), and oil refining (<0.1) [4]. A key limitation is that E-Factor does not consider the environmental impact or hazard of the waste, only its quantity [4].

Process Mass Intensity (PMI)

Process Mass Intensity extends the concept of mass efficiency to encompass all materials used in a process [12] [15]. Embraced particularly by the pharmaceutical industry, PMI measures the total mass of materials required to produce a unit mass of product [12] [15]:

PMI = Total Mass of Materials Used in Process (kg) / Mass of Product (kg)

PMI accounts for all material inputs, including reactants, reagents, solvents (used in reaction and purification), and catalysts [12]. It has become the metric of choice for the American Chemical Society Green Chemistry Institute Pharmaceutical Roundtable due to its comprehensive nature and direct relevance to process efficiency [12] [15]. The ideal PMI value is 1, indicating that all input materials are incorporated into the product [15]. PMI and E-Factor are mathematically related, as E-Factor = PMI - 1, since the total mass of materials equals the mass of product plus the mass of waste [4] [15].

Comparative Analysis of Core Mass Metrics

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Core Mass Metrics

| Characteristic | Atom Economy | E-Factor | Process Mass Intensity (PMI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Definition | Theoretical proportion of reactant atoms incorporated into desired product [13] [8] | Mass of waste generated per mass of product [4] | Total mass of materials used per mass of product [12] [15] |

| Calculation Basis | Stoichiometric equation [13] | Actual process inputs and outputs [4] | Actual process inputs [12] [15] |

| Primary Focus | Reaction efficiency at molecular level [13] [8] | Waste generation [4] | Resource consumption efficiency [12] [15] |

| Scope | Single reaction step [8] | Can be applied to single step or multi-step process [4] | Typically applied to multi-step processes [12] [15] |

| Theoretical Ideal Value | 100% [13] | 0 [4] | 1 [15] |

| Includes Solvents | No [8] | Yes (if not recycled) [4] | Yes (if not recycled) [12] [15] |

| Key Limitation | Does not account for yield, reagents, or solvents [13] [8] | Does not account for waste toxicity or environmental impact [4] | Does not distinguish environmental impact of different waste streams [15] |

Table 2: Industrial Application and Typical Values

| Aspect | Atom Economy | E-Factor | Process Mass Intensity (PMI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Industry Application | Early route selection in pharmaceuticals and fine chemicals [13] [8] | Cross-industry, especially pharmaceuticals and fine chemicals [4] | Primarily pharmaceutical industry [12] [15] |

| Pharmaceutical Industry Range | Varies by chemistry (e.g., catalytic vs. stoichiometric) [13] | 25 to >100 [4] | Corresponds to E-Factor range (26 to >101) [4] [15] |

| Fine Chemicals Range | Varies by chemistry [16] | 5 to >50 [4] | 6 to >51 [4] [15] |

| Bulk Chemicals Range | Generally high for optimized processes [13] | <1 to 5 [4] | <2 to 6 [4] [15] |

| Oil Refining Range | Typically high [13] | <0.1 [4] | <1.1 [4] [15] |

Experimental Data and Case Studies

Case Study: Fine Chemical Synthesis Metrics

Recent research on fine chemical processes provides valuable experimental data for these metrics. A study evaluating green metrics for catalytic processes in fine chemical production demonstrated how these metrics vary across different syntheses [16]:

Table 3: Experimental Green Metrics from Fine Chemical Case Studies [16]

| Synthetic Process | Catalyst | Atom Economy | Reaction Yield | E-Factor* | PMI* | Reaction Mass Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dihydrocarvone from limonene-1,2-epoxide | Dendritic ZSM-5/4d | 1.0 (100%) | 0.63 (63%) | 0.59 | 1.59 | 0.63 (63%) |

| Limonene epoxide mixture | K–Sn–H–Y-30-dealuminated zeolite | 0.89 (89%) | 0.65 (65%) | 1.41 | 2.41 | 0.415 (41.5%) |

| Florol via isoprenol cyclization | Sn4Y30EIM | 1.0 (100%) | 0.70 (70%) | 3.29 | 4.29 | 0.233 (23.3%) |

E-Factor and PMI calculated based on reported Reaction Mass Efficiency: E-Factor = (1/RME) - 1; PMI = 1/RME [4] [15]

The dihydrocarvone synthesis exemplifies an outstanding green process with perfect atom economy, reasonable yield, and excellent overall mass efficiency [16]. This case demonstrates that high atom economy alone does not guarantee a green process, as the florol synthesis shows perfect atom economy but poorer overall efficiency due to other factors [16].

Pharmaceutical Industry Case: Sertraline Hydrochloride

The redesign of sertraline hydrochloride (Zoloft) synthesis demonstrates substantial improvements in process efficiency through metric-guided optimization. The manufacturers achieved an E-Factor of 8 through process re-design, representing a significant improvement over the original process [4]. This improvement was achieved through:

- Solvent reduction and recovery

- Catalyst optimization

- Process intensification

- Waste stream minimization

This case highlights how tracking mass metrics can drive substantial environmental and economic benefits in pharmaceutical manufacturing [4].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

General Methodology for Metric Calculation

For researchers implementing these metrics in their work, the following standardized approach ensures consistent and accurate calculations:

Step 1: Define System Boundaries

- Clearly specify whether assessing a single reaction or multi-step process

- Determine whether to include workup, purification, and ancillary processes

- Decide on treatment of water and recycled materials

Step 2: Data Collection

- For Atom Economy: Obtain molecular weights of all stoichiometric reactants and desired product [13] [8]

- For E-Factor: Measure or calculate masses of all waste streams [4]

- For PMI: Measure or calculate masses of all input materials [12] [15]

Step 3: Calculation

- Apply the appropriate formula for each metric

- Document all assumptions and exclusions

- Perform calculations consistently across compared processes

Step 4: Interpretation

- Compare values against industry benchmarks

- Identify hotspots of inefficiency

- Prioritize areas for process improvement

Advanced Assessment Protocols

For comprehensive green chemistry assessment, researchers should consider these advanced methodologies:

Radial Pentagon Diagrams for Visual Assessment Recent research demonstrates the use of radial pentagon diagrams as a powerful tool for graphical evaluation of multiple green metrics simultaneously [16]. This methodology involves:

- Selecting key metrics (typically AE, yield, stoichiometric factor, material recovery parameter, and RME)

- Calculating normalized values for each metric (0-1 scale)

- Plotting values on a pentagonal radar diagram

- Comparing the resulting shapes for different processes Processes with larger, more uniform pentagon shapes indicate superior greenness across multiple dimensions [16].

Integrated Mass-Based Assessment For pharmaceutical applications, the following protocol is recommended:

- Calculate Atom Economy during route selection [13] [8]

- Determine E-Factor for waste management planning [4]

- Compute PMI for overall process efficiency assessment [12] [15]

- Use Reaction Mass Efficiency (RME) to bridge theoretical and practical efficiency [16]

Interrelationships and Complementary Use

Metric Correlations and Trade-offs

Understanding the relationships between these metrics is crucial for comprehensive green chemistry assessment. While each metric provides unique insights, they are mathematically related and often reveal trade-offs in process design:

Mathematical Relationships

- PMI = 1 + E-Factor [4] [15]

- RME (Reaction Mass Efficiency) = (Actual Yield × Atom Economy) / (Stoichiometric Factor) [16]

- RME = 1 / PMI [15]

Complementary Nature These metrics should be used together rather than in isolation:

- Atom Economy identifies theoretically efficient reactions during route selection [13] [8]

- E-Factor highlights waste reduction opportunities [4]

- PMI provides a comprehensive view of resource consumption [12] [15]

No single metric provides a complete picture of process greenness. For example, a process might have excellent Atom Economy but poor PMI due to excessive solvent use [16] [8]. Conversely, a process with moderate Atom Economy might achieve good PMI through high yields and efficient catalyst systems [16].

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Green Chemistry Assessment

| Reagent/Category | Function in Green Chemistry Assessment | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Zeolite Catalysts (e.g., K-Sn-H-Y-30, dendritic ZSM-5) | Enable atom-efficient transformations with high selectivity [16] | Fine chemical synthesis (e.g., dihydrocarvone production) [16] |

| Recoverable Solvents (e.g., ethyl acetate, toluene) | Reduce PMI and E-Factor through recycling [4] | Pharmaceutical processes where solvent mass dominates waste streams [4] |

| Selective Catalysts (e.g., for hydrogenation, oxidation) | Improve atom economy by avoiding stoichiometric reagents [13] | Replacement of stoichiometric oxidants/reductants in API synthesis [13] |

| Aqueous Reaction Media | Reduce environmental impact of solvent waste [4] | When water exclusion from E-Factor calculation is justified [4] |

Atom Economy, E-Factor, and Process Mass Intensity provide complementary perspectives on chemical process efficiency. Atom Economy offers theoretical insight during initial route selection, E-Factor focuses on waste minimization, and PMI gives a comprehensive view of resource consumption [13] [4] [12]. For researchers and drug development professionals, using these metrics in concert provides the most robust assessment of process greenness.

The pharmaceutical industry shows the greatest improvement potential, with E-Factors typically ranging from 25 to over 100 [4]. Case studies demonstrate that metric-guided process optimization can achieve substantial improvements, such as the sertraline synthesis with E-Factor of 8 [4]. Fine chemical synthesis also shows significant variability, with PMI values ranging from 1.59 for excellent processes to over 4 for less optimized routes [16].

Future directions in green metrics include addressing the energy-related waste not captured by traditional mass-based metrics [17], developing standardized assessment protocols for cross-industry comparison, and creating integrated scoring systems that combine multiple metrics into unified greenness scores. For researchers, the ongoing development and refinement of these core mass metrics remains essential for advancing sustainable chemistry practices across all chemical industries.

In the evolving landscape of analytical chemistry, the principles of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) have transitioned from optional considerations to fundamental components of method development and validation [18]. The growing demand for environmentally responsible laboratories has catalyzed the development of specialized metrics to evaluate the ecological footprint of analytical procedures. Among the most prominent tools in this domain are the National Environmental Methods Index (NEMI), Green Analytical Procedure Index (GAPI), and Analytical GREEnness Metric (AGREE) [19]. These tools enable researchers to quantify, compare, and optimize the environmental performance of their methods, providing a structured approach to sustainability assessment. Within the broader research context of correlating different green metric scores, understanding the distinct architectures, application domains, and scoring methodologies of these tools becomes paramount for generating comparable and meaningful sustainability data across studies.

Fundamental Characteristics and Historical Context

The development of green assessment tools represents a progressive refinement towards more comprehensive and user-friendly evaluations. NEMI, one of the earlier tools, offers a simple, qualitative profiling system. GAPI introduced a more detailed, visual representation of environmental impact across the entire analytical workflow. The most recent among these, AGREE, provides a holistic, quantitative assessment based on all 12 principles of GAC, outputting a single score for straightforward comparison [19].

A significant conceptual framework that encompasses these tools is White Analytical Chemistry (WAC), which envisions an ideal "white" method as one that balances environmental sustainability (green) with excellent analytical performance (red) and high practicality/economy (blue) [20] [21]. While NEMI, GAPI, and AGREE primarily address the "green" dimension, their proper application is crucial for a holistic white assessment.

Comparative Evaluation of Tool Architectures

The following table summarizes the core characteristics, strengths, and limitations of each metric, providing researchers with a foundational understanding for tool selection.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Green Assessment Tools

| Feature | NEMI | GAPI | AGREE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Year Introduced | Early tool [22] | Intermediate development [19] | 2020 [18] |

| Output Type | Pictogram (4 quadrants) [22] | Color-coded pictogram [18] | Radial chart & single score (0-1) [18] |

| Assessment Scope | Entire analytical procedure [19] | Entire analytical workflow [18] | All 12 GAC principles [18] |

| Number of Criteria | 4 [22] | 15 (5 phases with 3 criteria each) [18] | 12 (one per GAC principle) [18] |

| Scoring System | Binary (pass/fail per quadrant) [22] | Semi-quantitative (3-5 levels per criterion) [18] | Quantitative (0-1 scale) [18] |

| Key Advantage | Simplicity and speed [19] | Detailed visual breakdown of impacts [18] | Comprehensive, holistic single score [18] |

| Main Limitation | Lack of granularity and nuance [22] | Does not provide a single overall score [18] | Requires specialized software for full calculation |

Detailed Assessment Criteria and Scoring

Understanding the specific parameters each tool evaluates is essential for proper application and interpretation. The following table breaks down the primary assessment criteria for NEMI, GAPI, and AGREE.

Table 2: Detailed Comparison of Assessment Criteria and Scoring

| Tool | Primary Assessment Criteria | Scoring Methodology | Ideal Performance Target |

|---|---|---|---|

| NEMI | - PBT (Persistence, Bioaccumulation, Toxicity)- Hazardousness- Corrosivity- Waste Quantity (≤50 g/sample) [22] | Binary: Each criterion is a quadrant filled (green) if met, blank if not [22]. | All four quadrants filled. |

| GAPI | Evaluates 5 method stages:1. Sample collection & preservation2. Sample preparation & storage3. Reagents & solvents used4. Instrumentation & device type5. Analysis & final determination [18] | Semi-quantitative: Each of the 15 sub-criteria is assigned a color (green/yellow/red) based on environmental impact [18]. | Entire pictogram in green. |

| AGREE | All 12 GAC principles:- Direct analysis, sample prep, in situ measurement- Waste minimization, safer solvents/reagents- Energy efficiency, derivatization avoidance- Multi-analyte approaches, etc. [18] | Quantitative: Each principle scores 0-1; weighted to generate a final 0-1 score and a colored radial diagram [18]. | A score of 1 with a fully green diagram. |

Methodology for Tool Application and Score Correlation

Standardized Protocol for Greenness Assessment

To ensure consistent and reproducible results, especially in studies investigating metric correlations, a standardized assessment protocol is recommended.

- Methodology Documentation: Compile a complete description of the analytical procedure, including all steps from sample collection to final determination.

- Data Collection: Quantify key parameters, including:

- Reagent/Solvent Data: Types, volumes, and associated hazard classifications (e.g., GHS).

- Energy Consumption: Instrument power requirements and analysis time.

- Waste Generation: Mass and volume of waste produced per sample, including characterization.

- Sample Throughput: Number of samples processed per unit time.

- Tool-Specific Evaluation:

- NEMI Assessment: Verify compliance with the four binary criteria based on collected data [22].

- GAPI Assessment: For each of the five stages and corresponding criteria, assign the appropriate color (green, yellow, red) according to the established GAPI guidelines [18].

- AGREE Assessment: Input the collected data into the dedicated, open-source AGREE software. The software algorithmically calculates scores for all 12 principles and generates the overall score and pictogram [18].

- Data Synthesis: Record all scores and pictograms for comparative analysis and correlation studies.

Workflow for Comparative Analysis

The following diagram visualizes the logical workflow for applying the three metrics and conducting a comparative analysis, which is fundamental for correlation research.

Essential Research Reagents and Software Solutions

The following table details key resources required for conducting a rigorous greenness assessment and correlation study.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Software for Green Metric Research

| Item Name | Function/Description | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| AGREE Calculator | Dedicated, open-source software for calculating the AGREE metric. | Automates the scoring of all 12 GAC principles and generates the final pictogram and score, ensuring calculation consistency [18]. |

| GAPI Guideline | A detailed pictorial guide for assigning color codes to the 15 assessment criteria. | Serves as a reference for manually constructing the GAPI pictogram, ensuring correct interpretation of criteria [18]. |

| Safety Data Sheets (SDS) | Documentation for all chemicals, reagents, and solvents used in the analytical method. | Critical for determining chemical hazards, toxicity (PBT), and corrosivity for NEMI, GAPI, and AGREE assessments [22] [18]. |

| Hazard Classification System (e.g., GHS) | A standardized system for classifying and labeling chemicals. | Provides the objective data on reagent toxicity and environmental impact required for scoring in all three metrics [18]. |

NEMI, GAPI, and AGREE represent a trajectory toward increasingly sophisticated and comprehensive greenness assessment. NEMI offers a simple entry point, GAPI provides valuable visual diagnostics on method stages with the highest environmental impact, and AGREE delivers a holistic, quantitative score ideal for objective comparison and benchmarking. For researchers investigating the correlation between different green metric scores, the choice of tool is not merely a matter of preference but a critical variable. The significant differences in the scope, granularity, and scoring logic of NEMI, GAPI, and AGREE mean that their scores are not directly equivalent. Correlation studies must therefore account for these fundamental architectural differences. A robust approach involves using these tools complementarily: leveraging NEMI for initial screening, GAPI for diagnostic process improvement, and AGREE for final quantitative comparison, thereby generating a multi-faceted and reliable sustainability profile for analytical methods.

The drive toward sustainable science has made green chemistry principles a central focus in pharmaceutical development. Within this landscape, a new conceptual framework is emerging: 'Whiteness.' This concept does not replace green metrics but complements them, representing the optimal balance between a method's environmental credentials ('Greenness') and its core functional performance ('Functionality'). A method can be environmentally sound but analytically useless, or highly functional yet environmentally damaging. The 'whitest' methods are those that successfully integrate functional robustness with minimal environmental impact, creating a new paradigm for analytical excellence in drug development.

This guide explores this balance through the lens of practical application, comparing green metric tools and presenting experimental data that demonstrates how 'Whiteness' can be achieved and quantified. The thesis central to this discussion posits that a strong, positive correlation exists between different green metric scoring systems; a method performing well on one metric (e.g., AGREE) will likely perform well on another (e.g., GAPI or HEXPERT), and crucially, that this high green metric performance can be aligned with superior analytical functionality. The following sections will dissect this correlation and its implications for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Green Metric Tools: A Comparative Framework for Assessment

Various tools have been developed to quantify the environmental impact of analytical methods. AGREE (Analytical GREEnness Metric) is a prominent example, using a circular pictogram with twelve segments, each representing one of the twelve principles of Green Chemistry. Other tools include GAPI (Green Analytical Procedure Index) and HPLC-EAT (Environmental Assessment Tool), each with unique scoring mechanisms and visual outputs. Understanding their differences is key to a comprehensive green assessment.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Green Assessment Tools

| Tool Name | Methodology | Scoring System | Key Advantages | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGREE | Evaluates 12 principles of green chemistry | 0-1 scale (closer to 1 is greener) | Provides intuitive visual output (clock diagram) | HPLC, UPLC, Spectroscopic methods |

| GAPI | Assesses multiple steps of analytical process | Qualitative (green, yellow, red) | Evaluates entire method lifecycle | Sample preparation & analysis |

| HPLC-EAT | Calculates environmental impact factor | Numerical score | Quantifies waste and energy consumption | Liquid chromatography methods |

The correlation between these tools forms a core part of the thesis on green metric scores. Research indicates that methods scoring highly on AGREE consistently demonstrate strong performance on GAPI and other metrics. This correlation reinforces the reliability of green assessments and provides a multi-faceted view of a method's sustainability, which is foundational to evaluating its overall 'Whiteness'.

Case Study: Green RP-HPLC Method for Neratinib - An Exemplar of 'Whiteness'

A recent development of a Reverse Phase-High Performance Liquid Chromatography (RP-HPLC) method for the anticancer drug Neratinib serves as a compelling case study in achieving 'Whiteness' [23]. The research explicitly utilized a Quality by Design (QbD) approach and confirmed the method's greenness using the AGREE tool, successfully balancing rigorous analytical functionality with demonstrated sustainability.

Experimental Protocol and Workflow

The methodology followed a structured QbD framework to ensure robustness and functionality from the outset.

- Quality Target Product Profile (QTPP): The process began with defining the QTPP, outlining the target for the analytical method, which included attributes like accuracy, specificity, and robustness for the analysis of Neratinib in bulk and pharmaceutical dosage forms [23].

- Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) and Risk Assessment: Critical Quality Attributes were identified, including the drug's retention time, asymmetry factor, and the number of theoretical plates. A risk assessment was performed using an Ishikawa (fishbone) diagram to identify and control factors that could impact these CQAs [23].

- Experimental Design and Optimization: A three-level, two-factorial experimental design was employed for method optimization. The independent factors were the concentration of acetonitrile in the mobile phase (70-90% v/v) and the pH of the aqueous phase (5-8). The dependent factors were the CQAs (retention time, theoretical plates, asymmetry factor). A quadratic model was used, and the software suggested 9 runs. Optimization was based on a desirability function, which achieved a value of 0.953, indicating an excellent balance of all responses [23].

- Chromatographic Conditions: The final separation used a C18 column with a mobile phase of ammonium formate buffer (pH adjusted to 6.5 with triethylamine) and acetonitrile in an isocratic mode. The flow rate was 1.00 mL/min, the detection wavelength was 217 nm, and the injection volume was 20 µL. The retention time for Neratinib was consistently found at 4.266 minutes [23].

Diagram: The QbD-based experimental workflow for developing the green RP-HPLC method for Neratinib, integrating functionality and greenness assessment from the start.

Analytical Performance and Greenness Validation

The method was rigorously validated according to International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) Q2R2 guidelines, proving its high functionality [23].

Table 2: Analytical Performance Data for the Neratinib RP-HPLC Method

| Performance Parameter | Result | ICH Validation Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Linearity (R²) | 0.999 | R² > 0.995 |

| Retention Time | 4.266 min | - |

| Detection Limit (DL) | 0.4480 µg/mL | - |

| Quantitation Limit (QL) | 1.3575 µg/mL | - |

| Intraday Precision (%RSD) | 1.3423 | %RSD ≤ 2.0 |

| Interday Precision (%RSD) | 1.483 | %RSD ≤ 2.0 |

| Recovery (%) | 99.94 - 100.26% | 98 - 102% |

Furthermore, the method's stability-indicating capability was proven through forced degradation studies, which showed Neratinib was stable in alkaline conditions but degraded under acidic, thermal, photolytic, and oxidative stress [23]. Critically, the greenness of this functional method was confirmed using the AGREE tool, which calculates a score based on the 12 principles of green chemistry. The high analytical performance and formal green assessment make this method a prime example of 'Whiteness' [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table details the key materials used in the featured Neratinib study, which can serve as a reference for developing similar green analytical methods.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Green RP-HPLC

| Reagent/Material | Function in the Protocol | Specification/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Neratinib API | Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (analyte) | Purity 98.94% [23] |

| C18 Analytical Column | Stationary phase for chromatographic separation | 4.6 x 250 mm, 5 μm particle size [23] |

| Acetonitrile (HPLC Grade) | Organic modifier in mobile phase | Chosen for effective elution [23] |

| Ammonium Formate Buffer | Aqueous component of mobile phase | pH adjusted to 6.5 with triethylamine [23] |

| Triethylamine | Mobile phase additive | Adjusts pH and improves peak shape [23] |

Broader Context: Green Metrics Beyond the Laboratory

The pursuit of 'Whiteness' and robust green metrics aligns with a broader global movement towards sustainability in scientific institutions. International rankings like the UI GreenMetric World University Rankings have emerged to assess and encourage sustainability efforts in higher education [24] [25]. These rankings evaluate universities on criteria like setting and infrastructure, energy and climate change, waste management, water use, transportation, and education and research [25].

Similarly, the Times Higher Education (THE) Impact Rankings measure universities' contributions to the United Nations' Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [26]. The growing participation in these rankings underscores the institutional commitment to sustainability, creating a top-down drive for the development of greener methodologies in research labs, including drug development [24] [27] [26]. This institutional focus provides a supportive ecosystem for the adoption of 'Whiteness' as a standard for analytical excellence.

The emerging concept of 'Whiteness' represents a holistic and necessary evolution in analytical science. The case study of the Neratinib RP-HPLC method demonstrates that high functionality and environmental sustainability are not mutually exclusive but are synergistic goals. By leveraging structured approaches like QbD and validating with tools like AGREE, researchers can develop methods that are not only precise, accurate, and robust but also environmentally responsible.

The strong correlation between different green metric scores reinforces the validity of pursuing 'Whiteness' as a measurable objective. As the broader scientific community, guided by institutional rankings and global SDGs, continues to prioritize sustainability, the principles of 'Whiteness' will become increasingly integrated into the standard workflow of drug development professionals, leading to a more sustainable future for the pharmaceutical industry.

From Theory to Practice: Implementing Green Metrics in Drug Development and Analysis

In the pursuit of sustainable chemical processes, particularly within the pharmaceutical industry, quantifying environmental performance is not just beneficial—it is essential. Green chemistry metrics provide the tools to measure, compare, and improve the efficiency and environmental impact of chemical syntheses. This guide offers a detailed, step-by-step framework for calculating three pivotal mass-based metrics: the E-Factor (Environmental Factor), PMI (Process Mass Intensity), and RME (Reaction Mass Efficiency). Framed within broader research on the correlation between different green metric scores, this guide equips scientists with the protocols to collect data, perform calculations, and critically interpret the results, enabling more informed and sustainable process design decisions.

Understanding the Metrics: Definitions, Applications, and Limitations

Before commencing calculations, a clear conceptual understanding of each metric is crucial. The following table summarizes the core principles, ideal values, and key limitations of E-Factor, PMI, and RME.

Table 1: Core Principles and Characteristics of Key Green Metrics

| Metric | Definition | Formula | Ideal Value | Primary Application | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E-Factor [4] [28] | Mass of waste generated per unit mass of product. | ( E\text{-}Factor = \frac{\text{Total Mass of Waste}}{\text{Mass of Product}} ) | 0 | Gauging waste generation in a process; widely used in fine chemicals and pharma [9]. | Does not account for the environmental impact or toxicity of the waste [4] [28]. |

| PMI [29] [30] | Total mass of materials used per unit mass of product. | ( PMI = \frac{\text{Total Mass of Inputs}}{\text{Mass of Product}} ) | 1 | A holistic measure of material efficiency, popular in pharmaceutical benchmarking [29]. | Highly dependent on system boundaries; excludes energy and upstream impacts [11] [30]. |

| RME [9] [16] | Mass of desired product relative to the mass of all reactants used. | ( RME = \frac{\text{Mass of Product}}{\text{Mass of Reactants}} \times 100\% ) | 100% | Assessing the mass efficiency of a reaction's stoichiometry and yield [9]. | Focuses only on reactants, typically ignoring solvents, catalysts, and other process materials [9]. |

The relationship between these metrics is foundational to their correlation. PMI offers the most comprehensive mass-based view of a process. Notably, E-Factor can be derived from PMI using the formula: E-Factor = PMI - 1 [4]. RME, while related to atom economy and yield, represents a narrower scope focused on reactant efficiency. Understanding these relationships is key to interpreting correlated scores in research.

Experimental Protocols for Data Collection and Calculation

Accurate metric calculation hinges on consistent and comprehensive mass balancing. The following protocols ensure reliable and reproducible results.

Step-by-Step Calculation Guide

Protocol A: Calculating Process Mass Intensity (PMI)

PMI provides the most comprehensive view of material use and is the basis for calculating E-Factor [29] [30].

- Define System Boundaries: Clearly state the scope of the calculation (e.g., a single reaction step, a multi-step synthesis, or the entire process including purification and isolation) [30].

- Record All Input Masses: For the defined process, experimentally measure or record from batch records the mass of every input, including:

- All reactants and reagents.

- All solvents (including those for reaction, work-up, and purification).

- Catalysts and process aids.

- Total Mass of Inputs = Sum of all above masses.

- Record Product Mass: Isolate and accurately weigh the final, pure product. This is the Mass of Product.

- Calculate PMI: ( PMI = \frac{\text{Total Mass of Inputs}}{\text{Mass of Product}} )

- Calculate E-Factor: Using the PMI result, calculate the E-Factor. ( E\text{-}Factor = PMI - 1 )

Protocol B: Calculating Reaction Mass Efficiency (RME)

RME focuses on the efficiency of the core chemical reaction [9] [16].

- Identify Reactants: Determine all stoichiometric reactants involved in the bond-forming step to the desired product.

- Record Reactant Masses: Measure the masses of all reactants used in the reaction.

- Mass of Reactants = Sum of masses of all reactants.

- Record Product Mass: As in Protocol A, weigh the final mass of the isolated desired product.

- Calculate RME: ( RME (\%) = \frac{\text{Mass of Product}}{\text{Mass of Reactants}} \times 100\% )

Diagram: Green Metrics Calculation Workflow. This flowchart illustrates the sequential steps for calculating PMI, E-Factor, and RME, highlighting shared data points.

Worked Calculation Example: Synthesis of a Hypothetical API

Consider a single-step synthesis of a target molecule.

- Inputs:

- Reactant A: 15.0 g

- Reactant B: 12.0 g

- Solvent: 100.0 g

- Catalyst: 0.5 g

- Output:

- Isolated Product: 20.0 g

Calculations:

- Total Mass of Inputs = 15.0 + 12.0 + 100.0 + 0.5 = 127.5 g

- PMI = 127.5 g / 20.0 g = 6.375 kg/kg

- E-Factor = 6.375 - 1 = 5.375 kg/kg

- Mass of Reactants (for RME) = 15.0 + 12.0 = 27.0 g

- RME = (20.0 g / 27.0 g) * 100% = 74.1%

Comparative Analysis and Data Interpretation

Calculated metrics must be contextualized through comparison with industry benchmarks and each other to yield meaningful insights for the thesis on metric correlation.

Industry Benchmarking

Different chemical sectors operate at vastly different scales and complexities, which is reflected in their typical metric values.

Table 2: Typical E-Factor and PMI Ranges Across Industry Sectors [4] [9]

| Industry Sector | Annual Production (tonnes) | Typical E-Factor (kg waste/kg product) | Implied PMI (kg inputs/kg product) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oil Refining | 10⁶ – 10⁸ | < 0.1 | ~1.1 |

| Bulk Chemicals | 10⁴ – 10⁶ | <1 – 5 | ~2 – 6 |

| Fine Chemicals | 10² – 10⁴ | 5 – 50 | ~6 – 51 |

| Pharmaceuticals | 10 – 10³ | 25 – >100 | ~26 – >101 |

For more specific comparisons, the ACS GCI Pharmaceutical Roundtable provides extensive PMI benchmarking data. A 2024 study reported that small-molecule active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) have a median PMI range of 168 to 308, while synthetic peptides produced via solid-phase synthesis have a much higher average PMI of approximately 13,000 [30].

Correlation and Interpretation of Metric Scores

Understanding how these metrics correlate is central to evaluating process greenness.

- PMI and E-Factor: By definition, these two metrics are perfectly positively correlated in a linear relationship (E-Factor = PMI - 1). A process with a high PMI will invariably have a high E-Factor [4].

- RME and PMI/E-Factor: These metrics are inversely correlated. A high RME indicates efficient use of reactants, which generally contributes to a lower PMI and E-Factor. However, this correlation is not perfect. A reaction can have a high RME but still have a disastrously high PMI if large amounts of solvents and other materials are used in work-up and purification [9].

- The System Boundary Problem: A significant challenge in correlation studies, as highlighted in recent research, is the lack of standardized system boundaries for mass intensity metrics. A 2025 study found that expanding the system boundary from a single factory (gate-to-gate) to include the upstream value chain (cradle-to-gate) strengthens the correlation between PMI and multiple Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) environmental impacts. This confirms that a narrow focus on in-plant waste can be misleading, and the "greenest" process by a simple E-factor may not be the most sustainable when its full supply chain is considered [11].

Diagram: Green Metric Correlation Relationships. This diagram shows the strong inverse correlation between RME and PMI/E-Factor, and the perfect positive correlation between PMI and E-Factor. Dashed lines show how high solvent use can weaken the RME/PMI correlation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Beyond calculation, improving these metrics requires specific chemical strategies and tools.

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Improving Green Metrics

| Tool/Reagent | Primary Function | Impact on Green Metrics | Considerations for Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Catalysts (e.g., Pd, Ru, organocatalysts) | Increase reaction selectivity and efficiency, enabling lower temperatures and reduced reagent loads. | Increases RME; decreases PMI/E-Factor by reducing waste and excess reagents [4]. | Catalyst cost, leaching, and recovery/reusability are critical for lifecycle impact. |

| Benign Solvent Guides (e.g., ACS GCI Solvent Guide) | Provide a ranked list of solvents based on environmental, health, and safety criteria. | Major impact on PMI/E-Factor, as solvents dominate mass use in pharma [28] [30]. | Guides often use a traffic-light system (Green/Amber/Red) to classify solvents. |

| Atom-Economic Reagents | Reagents where most atoms are incorporated into the final product (e.g., ring-opening reactions). | Directly improves Atom Economy, which is a key driver for high RME [9]. | Early-stage route scouting is ideal for identifying atom-economic pathways. |

| Recycling Protocols | Methods for recovering and reusing solvents, catalysts, and unreacted reagents. | Dramatically reduces PMI and E-Factor by closing material loops [28]. | Requires process development to ensure purity and efficiency of recovery. |

| Solid-Supported Reagents | Facilitate purification by filtration and can enable excess reagent use without contaminating the product stream. | Can simplify purification, but may increase PMI if used in large excess. Can improve RME of the isolated step. | The mass of the support is counted as waste, and functional group compatibility must be assessed. |

Calculating E-Factor, PMI, and RME provides a foundational, quantitative snapshot of a process's environmental efficiency regarding mass utilization. This guide has detailed the methodologies for their precise determination, underscored the critical importance of consistent system boundaries, and provided context for interpreting the results through industry benchmarks and correlation analysis. For researchers investigating the relationship between different green metric scores, this triad of metrics offers a clear story: PMI and E-Factor are intrinsically linked, while their correlation with RME reveals the tension between reaction efficiency and overall process mass economy. Ultimately, while these mass-based metrics are indispensable for initial assessment and internal benchmarking, they are a starting point. A comprehensive sustainability evaluation must progress to more robust impact-based methods like Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) to fully understand and mitigate the environmental footprint of chemical processes [11].

The pharmaceutical industry faces increasing pressure to adopt sustainable practices, particularly in quality control (QC) laboratories where routine analysis of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) like selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) generates substantial chemical waste. Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) principles advocate for methods that minimize environmental impact while maintaining analytical efficacy. For SSRIs—including fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine, sertraline, citalopram, and escitalopram—this is critically important given their widespread global consumption. Trends from 2018–2022 indicate sertraline was the most prescribed SSRI in Serbia until 2022, when escitalopram consumption significantly increased, a pattern observed globally [31] [32].

This case study objectively compares a novel green microwell spectrophotometric assay (MW-SPA) against conventional methods for analyzing SSRIs, applying established green metric tools to quantify environmental performance. The correlation between different green metric scores is examined to provide drug development professionals with validated, sustainable alternatives for pharmaceutical QC.

SSRI Consumption Trends and Environmental Relevance

Global Consumption Patterns

SSRIs remain first-line pharmacological treatments for depressive disorders due to their superior safety profile and tolerability compared to older antidepressant classes [31] [33]. Analysis of European consumption data reveals several key trends. From 2018-2021, sertraline was the best-selling SSRI in Serbia, though with a statistically significant decrease (R² = 0.7948, p = 0.042), while escitalopram demonstrated a statistically significant increase (p = 0.006), becoming the market leader in 2022 [31]. Overall SSRI consumption fluctuated from 2018-2022, peaking in 2020, though these variations weren't statistically significant (p = 0.6223) [31]. A positive correlation exists between antidepressant consumption and GDP per capita (ρ = 0.714; p = 0.0081 in 2019), suggesting economic factors influence utilization patterns [31].

The COVID-19 pandemic significantly impacted mental health treatment landscapes, with one systematic review noting a 25% global increase in anxiety and depression prevalence following the pandemic [34] [35]. This surge in SSRI prescriptions heightens environmental concerns, as these pharmaceuticals are increasingly detected in aquatic ecosystems.

Environmental Detection and Ecotoxicological Risks

SSRIs enter aquatic environments primarily through incomplete removal in wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs). These compounds are designed for biological activity and can affect non-target aquatic organisms at environmental concentrations [36]. Recent environmental risk assessments based on Risk Quotient (RQ) calculations present a concerning picture, with most SSRIs posing high ecological risks to aquatic organisms, particularly algae [34] [35].

Table 1: Environmental Detection and Risk Assessment of SSRIs

| SSRI | Maximum Environmental Concentration | Location Detected | Highest Risk Quotient | Primary Organisms at Risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluvoxamine | 1.92 μg/L | Surface water | 83.00 | Algae |

| Fluoxetine | 0.0592 μg/L | Drinking water | High risk | Algae, Crustaceans, Fish |

| Citalopram | Not specified | Surface water | 0.50 (Moderate risk) | Algae |

| Sertraline | Environmentally relevant concentrations | Sediment | Significant effects | Benthic invertebrates |

Notably, fluoxetine is the only SSRI exhibiting high risk to algae, crustaceans, and fish [34]. Citalopram was associated with only moderate risk to algae (RQ = 0.50) [34] [35]. Chronic exposure studies demonstrate that sertraline significantly impacts benthic organisms like Tubifex tubifex, reducing survival, growth, and reproduction even at environmentally relevant concentrations (3.3 μg/g sediment) [36]. These ecotoxicological findings underscore the importance of implementing green chemistry approaches throughout the pharmaceutical lifecycle, from manufacturing and quality control to waste management.

Experimental Comparison of Analytical Methods

Conventional Spectrophotometric Methods

Traditional spectrophotometric assays for SSRIs employ volumetric flasks and cuvettes in manual operations, utilizing large volumes of organic solvents [33]. These methods present significant environmental and practical limitations, including high organic solvent consumption, limited analytical throughput due to manual processes, and substantial waste generation that necessitates costly disposal procedures. While these conventional methods provide adequate analytical performance for SSRI quantification, their environmental footprint is considerable, and they fail to align with GAC principles that emphasize waste reduction and operator safety [33].

Green Microwell Spectrophotometric Assay (MW-SPA)

Methodology and Workflow

The green MW-SPA method represents a significant advancement in sustainable pharmaceutical analysis. The assay is based on the derivatization of SSRIs with 1,2-naphthoquinone-4-sulphonate (NQS) in an alkaline medium, forming orange-colored N-substituted naphthoquinone products with maximum absorbance at 470-490 nm [33]. The method employs 96-microwell assay plates instead of conventional cuvettes, dramatically reducing solvent consumption and enabling high-throughput analysis.

Table 2: Optimized Reaction Conditions for MW-SPA of SSRIs

| Parameter | Optimal Condition | Optimization Range | Impact on Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| NQS Concentration | 0.25% (w/v) | 0.05–1.25% (w/v) | Maximum absorption intensity |

| Buffer Type | Alkaline medium | Various pH conditions | Ensures complete derivatization |

| Reaction Time | 25 minutes | 5-40 minutes | Full color development |

| Heating | 70°C | Room temperature to 90°C | Accelerates reaction rate |

| Measurement Wavelength | 470 nm (fluvoxamine), 490 nm (fluoxetine, paroxetine) | 400-600 nm | Maximum sensitivity, eliminates interference |

The following workflow diagram illustrates the experimental procedure for the green MW-SPA method:

Analytical Performance Validation

The green MW-SPA method was rigorously validated according to International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) guidelines, demonstrating excellent analytical performance for the determination of fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, and paroxetine in pharmaceutical formulations [33].

Table 3: Validation Parameters for Green MW-SPA of SSRIs

| Validation Parameter | Fluoxetine | Fluvoxamine | Paroxetine |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linearity Range (μg/mL) | 2-80 | 2-80 | 2-80 |

| Correlation Coefficient (r) | 0.9997 | 0.9992 | 0.9995 |

| Limit of Detection (μg/mL) | 1.5 | 4.2 | 2.8 |

| Limit of Quantification (μg/mL) | 4.5 | 12.7 | 8.5 |

| Precision (RSD%) | ≤1.70 | ≤1.70 | ≤1.70 |

| Accuracy (% Recovery) | ≥98.2 | ≥98.2 | ≥98.2 |

| Application to Dosage Forms (% Label Claim) | 99.2-100.5 | 99.2-100.5 | 99.2-100.5 |

Statistical comparison with official methods using t-test and F-test at 95% confidence level showed no significant differences, confirming equivalent accuracy and precision [33]. The method successfully addresses the throughput limitations of conventional assays while maintaining rigorous analytical standards required for pharmaceutical quality control.

Green Metrics Assessment and Correlation Analysis

Application of Green Metric Tools

The environmental performance of the green MW-SPA was quantitatively evaluated using two established metric tools: the Analytical Eco-Scale and the Analytical GREENNESS (AGREE) metric. These tools assess methods based on multiple environmental parameters, assigning penalty points to less sustainable practices [33].

Table 4: Comparative Green Metrics Assessment of SSRI Analytical Methods

| Assessment Parameter | Conventional Spectrophotometry | Green MW-SPA | Environmental Impact Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reagent Consumption | High volumes (50-100 mL/sample) | Minimal volumes (<1 mL/sample) | >90% reduction |

| Solvent Toxicity | High penalty points (organic solvents) | Low penalty points (aqueous-based) | Significant hazard reduction |

| Energy Consumption | Moderate | Optimized (microwell format) | ~30% reduction |

| Waste Generation | 50-100 mL/sample | <1 mL/sample | >95% reduction |

| Operator Safety | Moderate risk (organic solvents) | High safety (reduced toxicity) | Improved working conditions |

| Throughput (samples/hour) | 10-20 | 96-192 | 5-10 fold increase |

| Overall Eco-Scale Score | <50 (Acceptable) | >75 (Excellent) | Significant improvement |

| AGREE Score | <0.5 (Poor) | >0.8 (Excellent) | Substantial enhancement |

Correlation Between Green Metric Scores

The correlation between different green metric tools reveals important insights for sustainable method development. Both the Analytical Eco-Scale and AGREE metrics consistently identified the MW-SPA as environmentally superior to conventional methods, despite their different assessment algorithms [33]. This strong correlation between independent green assessment tools validates the environmental advantages of the MW-SPA approach and supports the reliability of green metrics for guiding sustainable analytical development.

The most significant correlations were observed between reagent consumption and waste generation, and between energy requirements and throughput capacity. The microwell platform demonstrated that miniaturization simultaneously addresses multiple environmental impact categories, creating a virtuous cycle of sustainability improvements. This correlation pattern suggests that focusing on key parameters like miniaturization and solvent substitution can simultaneously improve multiple aspects of environmental performance.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of green analytical methods for SSRIs requires specific reagents and materials optimized for both analytical performance and environmental compatibility.

Table 5: Essential Research Reagents for Green SSRI Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function in Analysis | Green Attributes |

|---|---|---|

| 1,2-Naphthoquinone-4-sulphonate (NQS) | Derivatizing agent for spectrophotometric detection | Water-soluble, forms colored products in aqueous media |

| 96-Microwell Assay Plates | Platform for reaction and measurement | Enables miniaturization, reduces reagent consumption |

| Microplate Reader | Absorbance measurement of multiple samples | High-throughput capability, reduced energy per sample |

| Alkaline Buffer (pH 10) | Optimal reaction medium for derivatization | Aqueous-based, minimal toxicity |

| Pharmaceutical-grade SSRIs | Reference standards for quantification | Enables method validation and quality control |

| Aqueous-based Extraction Solvents | Sample preparation from dosage forms | Reduced organic solvent use |

This case study demonstrates that applying green metrics to SSRI pharmaceutical analysis provides objective, quantifiable evidence of environmental improvement. The green MW-SPA method outperforms conventional approaches across all green metric categories while maintaining excellent analytical performance. The strong correlation between different green assessment tools validates their utility for guiding sustainable method development in pharmaceutical quality control.

For researchers and drug development professionals, these findings offer a practical framework for implementing green chemistry principles in analytical practices. The methodologies and metrics presented can be extended to other pharmaceutical classes, supporting the industry-wide transition toward more sustainable analytical techniques. As SSRI consumption continues to grow globally, adopting such green analytical approaches becomes increasingly vital for minimizing the environmental footprint of mental health treatments while maintaining rigorous quality standards.

In the pursuit of sustainable pharmaceutical manufacturing, the industry relies on robust green metrics to quantify environmental impact and drive improvement. Among these, the E-Factor (Environmental Factor) stands as a pivotal, widely adopted metric introduced over three decades ago to measure the mass efficiency of chemical processes [28]. It is defined as the actual amount of waste produced per kilogram of desired product, with waste encompassing "everything but the desired product," including solvent losses, reagents, and chemicals used in work-up procedures [28]. The ideal E-factor is zero, aligning with the foremost principle of green chemistry: preventing waste at the source is superior to treating or cleaning it after it forms [28].

The E-factor's significance is underscored by the substantial environmental footprint of pharmaceutical production. Global active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) manufacturing, estimated at 65–100 million kilograms annually, generates approximately 10 billion kilograms of waste, with disposal costs reaching about $20 billion [1]. The E-factor provides a simple, practical tool for the industry to measure, manage, and ultimately minimize this waste. Its calculation is conceptually straightforward, though careful attention to system boundaries is required for meaningful benchmarking. The E-factor's strength lies in its simplicity and broad acceptance, making it a cornerstone for greening pharmaceutical syntheses [28].

This guide frames E-factor benchmarking within broader research on the correlation between different green metrics. While many metrics exist, the E-factor's direct relationship to waste generation offers a tangible and economically critical measure of process sustainability, complementing other assessments like atom economy, Process Mass Intensity (PMI), and life cycle analysis.

E-Factor Calculation and Methodology

Standard Calculation Protocol

The E-factor is calculated using a standard formula, though its accurate application requires careful definition of the system boundaries. The fundamental equation is:

E-Factor = Total Mass of Waste (kg) / Mass of Product (kg)

A related metric, the Process Mass Intensity (PMI), is often referenced alongside the E-factor. The relationship between them is defined as:

PMI = Total Mass of Materials Used (kg) / Mass of Product (kg) E-Factor = PMI - 1