A New Researcher's Guide to Green Lab Tools: Boosting Sustainability in Drug Discovery

This guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a practical framework for adopting green tools and principles.

A New Researcher's Guide to Green Lab Tools: Boosting Sustainability in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a practical framework for adopting green tools and principles. It covers the foundational reasons for pursuing sustainability, details specific methodologies and software for application, offers solutions for common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and provides a comparative analysis for tool validation. The aim is to equip labs with the knowledge to reduce their environmental impact without compromising scientific rigor, aligning with a growing global emphasis on sustainable science.

Why Green Tools Are Revolutionizing Modern Research Labs

The Environmental and Business Case for Sustainable Labs

Scientific research is a cornerstone of innovation and societal progress, yet traditional laboratory operations carry a significant, often overlooked, environmental burden. Laboratories are among the most energy- and resource-intensive spaces within any research institution, contributing substantially to carbon emissions and waste generation [1]. This creates a paradox: while scientists work to solve pressing environmental and health challenges, their own workplaces can inadvertently contribute to the very problems they seek to address. The concept of sustainable labs, or "Green Labs," has emerged as a response to this dissonance, focusing on improving resource and energy efficiency, waste reduction, and environmental responsibility without compromising research quality or outcomes [1].

The business case for sustainable laboratories is equally compelling. Implementing green practices leads to substantial operational cost savings through reduced energy and water consumption, lower waste disposal fees, and more efficient use of precious research materials. Furthermore, sustainable laboratories often experience improved safety profiles and foster a culture of innovation and responsibility that resonates with funding bodies, partners, and the next generation of researchers. This document provides a comprehensive technical guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to understand and implement sustainable laboratory practices within the context of a broader thesis on the best green tools for new researchers.

Quantifying the Environmental Impact of Laboratories

To fully appreciate the case for sustainable labs, one must first understand the scale of their environmental footprint. Evidence collected from various institutions reveals consistent patterns of high resource consumption across different laboratory types.

Energy Consumption and Carbon Emissions

Laboratories consume significantly more energy per square meter than conventional office spaces—anywhere from five to ten times more, and in specialized cases up to 100 times more energy than an equivalent office area [1]. This energy intensity translates directly into carbon emissions. The annual work-related footprint of a single researcher is estimated at 10 to 37 tons of CO₂ equivalents (CO₂e), far exceeding the Paris-aligned annual carbon budget of 1.5 tons CO₂e per person [1].

Table 1: Energy Consumption of Common Laboratory Equipment

| Equipment | Energy Consumption (Relative to Household) | Annual Operating Cost (Estimated) | Key Facts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fume Hood | 3.5 times | 4,107 € [1] | Consumes as much energy as 3.5 households; 44% of lab energy relates to ventilation |

| Ultra-Low Temperature (ULT) Freezer | 2.7 times | 3,103 € [1] | Consumes 20-25 kWh per day |

| Laboratory Building | 5-10 times (per m² vs. office) | N/A | Can be 100x for specialized labs with clean rooms |

The distribution of a laboratory's carbon emissions can be categorized according to the Greenhouse Gas Protocol. Scope 1 includes direct emissions from refrigerants and on-site energy generation. Scope 2 covers indirect emissions from purchased electricity for heating, cooling, and building operation. Scope 3, often the most substantial portion, encompasses indirect emissions across the entire value chain, including production of purchased equipment and chemicals, travel, and waste disposal [1].

Resource Consumption and Waste Generation

Beyond energy, laboratories are significant consumers of water and generators of waste, particularly plastic waste. Research laboratories are responsible for an estimated 5.5 million tonnes of plastic waste annually, corresponding to 2% of the global plastic waste stream [1]. Water consumption for cooling and washing processes in laboratories can account for approximately 60% of a university's total water usage [1].

Table 2: Overall Environmental Impact of Research Laboratories

| Impact Category | Scale of Impact | Comparative Benchmark |

|---|---|---|

| Energy Consumption | 60-65% of a university's total energy [1] | 5-10x more energy per m² than office space [1] |

| Plastic Waste | 5.5 million tonnes/year globally [1] | 2% of global plastic waste [1] |

| Water Consumption | ~60% of a university's total water [1] | Majority used for cooling and washing processes |

| Researcher Carbon Footprint | 10-37 tons CO₂e/year [1] | 7-25x Paris-aligned budget (1.5 tons CO₂e) [1] |

Sustainable Lab Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Implementing sustainable laboratory practices requires both behavioral changes and technical interventions. The following section outlines proven methodologies and protocols for reducing the environmental impact of research operations.

Core Behavioral and Operational Interventions

The "Shut the Sash" Program: Harvard University's pioneering "Shut the Sash" program, initiated in 2005, demonstrates the profound impact of simple behavioral changes. The program promotes keeping fume hood sashes closed when not in use to reduce energy consumption. The initiative expanded to include 19 labs and over 350 researchers, resulting in substantial energy savings and improved lab safety, making it Harvard's "most impactful behavioral change program for energy conservation" [2]. The experimental protocol for implementing such a program involves:

- Baseline Assessment: Measure energy consumption of fume hoods during typical operation over a 4-week period.

- Researcher Engagement: Develop educational materials explaining the energy and cost implications of open fume hoods.

- Implementation: Launch a focused campaign with clear signage and regular reminders.

- Monitoring and Feedback: Track energy consumption continuously and share savings with laboratory personnel.

- Gamification: Introduce competitive elements between labs to enhance engagement, with recognition for highest participation rates.

Freezer Management Protocols: Ultra-low temperature (ULT) freezers represent one of the most energy-intensive pieces of laboratory equipment. Sustainable management involves:

- Increasing Setpoint Temperatures: Where scientifically valid, raising ULT freezer temperatures from -80°C to -70°C can reduce energy consumption by 30-40% [1].

- Regular Maintenance: Cleaning coils and ensuring proper door seals maintain efficiency.

- Inventory Management: Implementing organized sample storage systems to minimize door-open time and facilitate sample retrieval efficiency.

- Freezer Consolidation: Periodically auditing and consolidating samples to maximize freezer utilization and decommission unnecessary units.

Green Lab Certification Framework

A structured approach to laboratory sustainability can be implemented through formal certification programs such as My Green Lab, which sets the "global benchmark for lab sustainability" [3]. The certification process follows a systematic methodology:

Table 3: Green Lab Certification Process

| Stage | Key Activities | Outputs/Deliverables |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Pre-Assessment | - Form green team- Conduct initial waste, energy, and water audit- Identify baseline metrics | Baseline impact assessment report |

| 2. Planning | - Set sustainability targets- Develop action plan with assigned responsibilities- Identify low-cost, high-impact opportunities | Strategic sustainability plan with timeline |

| 3. Implementation | - Roll out equipment upgrades- Introduce behavioral interventions- Establish monitoring systems- Researcher training and engagement | Implemented interventions and training records |

| 4. Certification | - Document outcomes and savings- Third-party audit (if required)- Continuous improvement planning | Certification award and public recognition |

The following workflow diagram illustrates the strategic implementation pathway for establishing a sustainable laboratory:

The Researcher's Toolkit for Sustainable Science

Computational Sustainability Tools

For researchers engaged in computational work, particularly in machine learning and data analysis, several tools have been developed to measure and minimize the carbon footprint of calculations. These tools represent the "best greenness tools for new researchers" referenced in the thesis context.

Table 4: Digital Tools for Sustainable Computation

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Integration | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| CodeCarbon [4] | Tracks carbon emissions of code | Python, PyTorch, TensorFlow | - Monitors CPU/GPU/RAM usage- Regional carbon intensity data- Local computation, privacy-safe |

| Experiment Impact Tracker (EIT) [4] | Logs energy use and carbon footprint of ML experiments | Python/ML workflows | - Transparent, reproducible logging- Well-suited for academic benchmarking- Local logging only |

| CarbonTracker [4] | Measures and forecasts carbon footprint of model training | Deep learning training loops | - Predicts future energy use mid-training- Enables early stopping decisions- Uses real-time grid data via APIs |

| Eco2AI [4] | Tracks CO₂ emissions of ML workloads | Python, CPU/GPU tasks | - Simple integration with decorators- All data stored locally- Detailed metadata recording |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Sustainable laboratory operations extend to the careful selection and management of laboratory reagents and materials. The following table outlines key considerations for establishing a sustainable reagent management system.

Table 5: Sustainable Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent Category | Sustainable Practice | Environmental Benefit | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Solvents | - Solvent recycling systems- Green chemistry alternatives | Reduces hazardous waste generation and procurement needs | Distillation apparatus for acetone and ethanol reuse |

| Biological Buffers | - Preparation in larger batches- Shared departmental stocks | Reduces packaging waste and energy for repeated preparation | Centralized PBS and TBST preparation facility |

| Enzymes & Antibodies | - Optimal aliquoting to avoid freeze-thaw cycles- Shared resource databases | Prevents reagent loss and redundant purchases | Digital inventory system with cross-lab access |

| Plastic Consumables | - Selection of recyclable materials- Glassware substitution where possible | Diverts plastic from landfill and reduces fossil fuel consumption | PP and HDPE recycling program with proper decontamination |

Business Case Analysis: Financial Implications of Sustainable Labs

The transition to sustainable laboratory practices generates significant financial returns alongside environmental benefits. A case study from the University of Groningen demonstrated annual savings of 398,763 € and 477.1 tons of CO₂e through comprehensive sustainability measures [1]. These savings typically accrue from several key areas:

Energy Efficiency Returns

Energy conservation measures deliver the most immediate financial returns. The "Shut the Sash" program at Harvard generates substantial savings given that a single fume hood consumes 3.5 times more energy than an average household [1]. Similar principles apply to ULT freezer management, where strategic temperature adjustments and retirement of unnecessary units can save thousands of dollars annually per unit. With laboratories accounting for nearly 44% of energy use at Harvard while occupying only 20% of the space [2], these efficiencies translate to institution-wide impact.

Waste Management Economics

Sustainable waste management practices reduce both disposal costs and procurement expenses. Laboratories produce an estimated 5.5 million tonnes of plastic waste annually [1], with significant associated disposal costs, particularly for hazardous materials. Implementing plastic recycling programs for non-contaminated materials, transitioning to reusables where possible, and right-sizing experiments to minimize waste generation all contribute to substantial cost reduction while aligning with circular economy principles.

Strategic Advantages

Beyond direct cost savings, sustainable laboratories enjoy strategic benefits including:

- Enhanced Funding Opportunities: Granting agencies increasingly favor researchers with sustainable operations and smaller environmental footprints.

- Talent Attraction and Retention: Next-generation scientists preferentially seek employers with demonstrated environmental commitment.

- Risk Mitigation: Reduced reliance on single-use plastics and hazardous materials buffers against supply chain disruptions.

- Positive Public Relations: Demonstrable sustainability leadership enhances institutional reputation among stakeholders.

The scientific community faces a critical opportunity to align research practices with environmental stewardship. The evidence is clear: traditional laboratory operations carry an substantial environmental footprint through excessive energy consumption, resource depletion, and waste generation. However, proven methodologies and tools exist to dramatically reduce this impact while simultaneously generating significant financial returns.

Sustainable laboratory practices are not merely an ethical imperative but a strategic one, offering reduced operational costs, enhanced research efficiency, and improved safety outcomes. From behavioral interventions like the "Shut the Sash" program to technical solutions enabled by tools such as CodeCarbon and comprehensive certification frameworks like My Green Lab, researchers now have a robust toolkit for transformation.

As scientists dedicated to discovery and innovation, the research community must embody the change it wishes to see in the world. How can we expect industry, politics, and society to change, if we as scientists are not changing either? By implementing the practices outlined in this document, researchers can lead by example, demonstrating that scientific excellence and environmental responsibility are not merely compatible, but fundamentally interconnected.

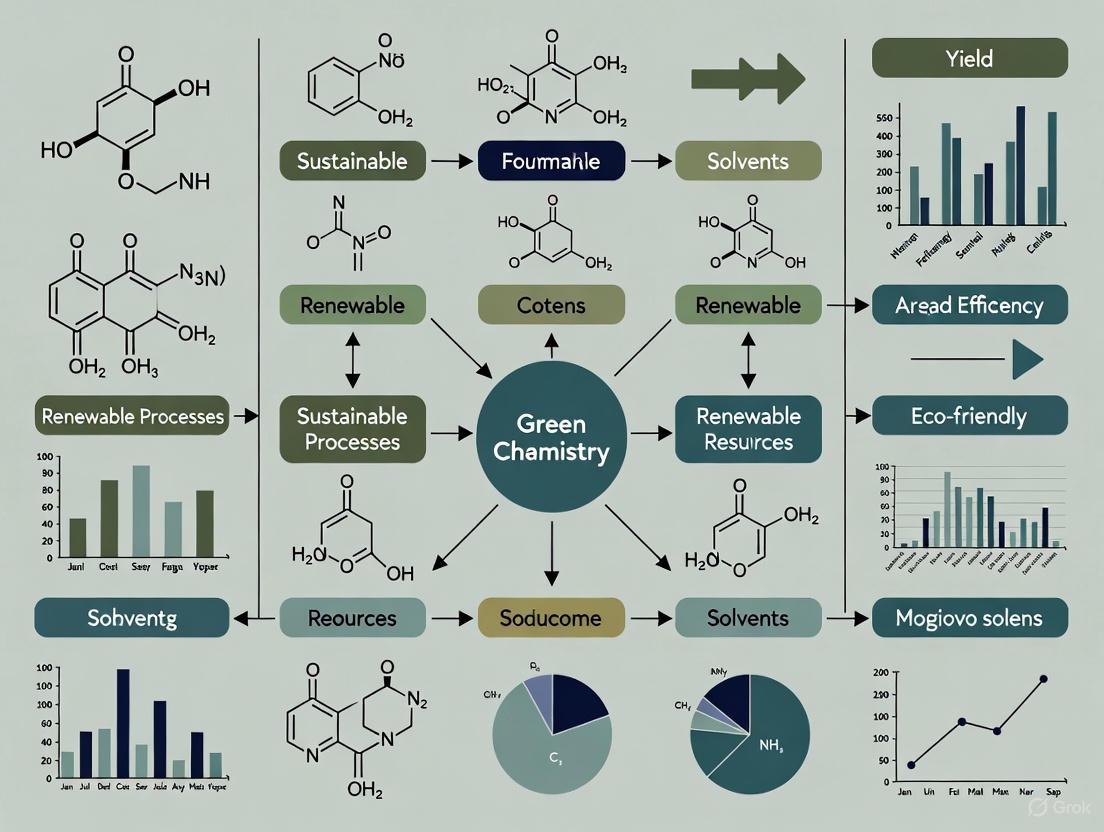

The integration of sustainability into scientific research has evolved from a niche concern to a central pillar of modern investigation. This whitepaper explores the foundational principles connecting two seemingly disparate fields: green chemistry and energy-efficient computing. For researchers, particularly in drug development, understanding these interconnected principles is crucial for reducing environmental impact while maintaining scientific rigor and innovation. The growing availability of standardized assessment tools enables quantitative evaluation of research sustainability, allowing scientists to make informed decisions that align with both environmental and research objectives.

Green chemistry emerged as a formalized philosophy in the 1990s with the establishment of the 12 Principles of Green Chemistry, providing a systematic framework for designing chemical products and processes that reduce or eliminate hazardous substances [5]. Parallelly, energy-efficient computing has gained prominence as computational workloads, particularly in AI and pharmaceutical research, have dramatically increased global energy consumption [6]. What unites these fields is a shared focus on prevention rather than remediation, efficiency optimization, and lifecycle thinking—concepts that form the bedrock of sustainable research practices.

Foundational Principles and Their Convergence

Core Principles of Green Chemistry

Green chemistry operates on well-established principles that guide researchers in designing safer chemical processes and products. The most widely recognized framework consists of twelve principles that emphasize waste prevention, atom economy, reduced hazard, and safer materials [5]. These principles have been adapted into specialized frameworks for specific applications, including:

- Green Extraction Principles: A set of six principles specifically tailored for natural product extraction processes [5].

- Green Sample Preparation Principles: Ten principles focusing specifically on sample preparation in analytical chemistry [5].

These specialized adaptations demonstrate how core green chemistry concepts can be successfully applied to specific research domains—a valuable lesson for researchers seeking to implement sustainable practices in their own fields.

Core Principles of Energy-Efficient Computing

Energy-efficient computing focuses on maximizing computational performance while minimizing energy consumption through optimized hardware, software, and systems design. Key principles include:

- Hardware Efficiency: Utilizing specialized processors (GPUs, TPUs, ASICs) that handle specific workloads more efficiently than general-purpose CPUs [6] [7].

- Software Optimization: Developing algorithms and code that minimize computational overhead through efficient coding practices and algorithmic improvements [6] [7].

- System-Level Design: Implementing smart workload distribution, dynamic cooling systems, and power-aware scheduling [6].

- Workload Consolidation: Using virtualization and containerization to increase hardware utilization and reduce total server count [7].

Converging Principles for Sustainable Research

The intersection between green chemistry and energy-efficient computing reveals fundamental similarities in approach that can inform sustainable research practices:

Table: Converging Principles in Green Chemistry and Energy-Efficient Computing

| Green Chemistry Principle | Energy-Efficient Computing Equivalent | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Prevention of waste | Optimization of algorithms to reduce redundant computations | Designing research protocols to minimize unnecessary calculations and experimental iterations |

| Atom economy | Performance per watt metrics | Maximizing useful research outputs per unit of energy input |

| Use of safer solvents & materials | Selection of energy-efficient hardware | Choosing laboratory equipment and computational resources with lower environmental impact |

| Energy efficiency in design | Power-aware scheduling | Scheduling computational workloads during off-peak hours or periods of renewable energy availability |

| Use of renewable feedstocks | Renewable energy integration | Powering research facilities and computational infrastructure with renewable sources |

Assessment Frameworks and Metric Tools

Green Chemistry Assessment Tools

Numerous standardized tools have been developed to evaluate and quantify the greenness of chemical processes. These tools provide researchers with objective metrics for comparing methodologies and identifying areas for improvement:

Table: Green Chemistry Assessment Tools and Applications

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Research Application | Key Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Green Extraction Tree (GET) | Visual assessment of natural product extraction greenness [5] | Evaluation and comparison of extraction methods | Environmental impact scores across samples, solvents, energy, byproducts |

| AGREE | Comprehensive greenness assessment of analytical methods [8] | Method development and optimization | Multiple environmental impact categories |

| GAPI | Graphical evaluation of analytical procedure environmental impact [8] | Sustainability profiling of analytical methods | Visual indicators across analytical process steps |

| Process Mass Intensity (PMI) Calculator | Quantification of material efficiency [9] | Process optimization in pharmaceutical manufacturing | Mass of materials per unit of product |

| ACS GCI Solvent Selection Guide | Guidance for choosing environmentally preferable solvents [9] | Solvent selection in chemical synthesis | Health, safety, and environmental criteria |

The Green Extraction Tree (GET) represents a particularly innovative approach, employing a "tree" pictogram to classify and evaluate the greenness of various aspects of natural product extraction processes [5]. It uses three different color markers (green, yellow, red) to represent three distinct levels of environmental impact across different processes, enabling researchers to quickly visualize both the overall sustainability profile and specific areas needing improvement.

Energy Efficiency Assessment Metrics

For computational research, several standardized metrics enable quantitative evaluation of energy efficiency:

Table: Energy Efficiency Metrics for Computational Research

| Metric | Calculation | Application in Research | Optimal Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Power Usage Effectiveness (PUE) | Total facility power/IT equipment power | Data center efficiency benchmarking [7] | 1.0-1.4 (closer to 1.0 is better) |

| Performance per Watt | Useful computations per watt consumed | Hardware selection for research computations [6] | Varies by application |

| Carbon Usage Effectiveness (CUE) | CO2 emissions from total energy/IT equipment energy | Carbon impact assessment [6] | Lower values preferred |

| Energy per Inference | Total energy consumption/number of AI inferences | AI model efficiency comparison [6] | Application-dependent |

These metrics are increasingly important as computational methods become more integral to pharmaceutical research, particularly in areas like molecular modeling, drug screening, and AI-assisted compound design.

Implementation Methodologies

Experimental Protocol for Green Chemistry Assessment

Objective: Systematically evaluate and compare the environmental performance of two alternative extraction methods for natural products using the Green Extraction Tree (GET) methodology.

Materials and Equipment:

- Standard laboratory extraction apparatus (e.g., Soxhlet, microwave, ultrasonic)

- Analytical equipment for yield determination (e.g., HPLC, GC-MS)

- GET assessment toolkit [5]

Procedure:

- Define Assessment Parameters: Identify key evaluation criteria based on the 10 principles of green sample preparation and six principles of green extraction of natural products [5]. These typically include:

- Sample amount and preparation requirements

- Solvent type, volume, and recyclability

- Energy consumption per extraction cycle

- Byproduct generation and waste management requirements

- Process safety considerations

- Extract quality and yield

Conjugate Extraction Processes: Perform extractions using two different methods (e.g., conventional Soxhlet vs. microwave-assisted extraction) while maintaining equivalent output quality.

Data Collection: Quantify input materials, energy consumption, waste output, and process hazards for each method.

GET Evaluation:

- For each assessment parameter, assign color codes: green (low environmental impact), yellow (medium impact), or red (high impact) [5].

- Convert color codes to numerical scores (green=2, yellow=1, red=0).

- Generate GET pictogram using the open-access toolkit.

- Calculate total greenness score for each method.

Comparative Analysis: Identify specific areas where each method excels or requires improvement based on the GET visualization and numerical scores.

Process Optimization: Implement modifications to address high-impact areas (e.g., solvent substitution, energy recovery systems) and reassess.

This methodology enables researchers to make objective comparisons between alternative processes and focus optimization efforts on parameters with the highest environmental impact.

Implementation Framework for Energy-Efficient Computing

Objective: Establish a comprehensive energy efficiency program for computational research workflows.

Phase 1: Baseline Assessment

- Infrastructure Audit: Document all computational hardware, including age, specifications, and typical utilization patterns.

- Energy Monitoring: Implement power monitoring at the server, rack, and data center levels to establish baseline Power Usage Effectiveness (PUE) [7].

- Workload Characterization: Profile research applications to identify computational patterns, peak demand periods, and resource utilization efficiency.

Phase 2: Optimization Implementation

- Hardware Improvements:

- Replace aging equipment with energy-efficient models featuring advanced power management capabilities.

- Implement specialized processors (e.g., GPUs, TPUs) for specific research workloads like molecular dynamics or machine learning [7].

- Consolidate underutilized servers using virtualization technologies.

Software and Algorithm Optimization:

- Profile research code to identify and optimize inefficient algorithms.

- Implement energy-aware coding practices and utilize efficient libraries and frameworks.

- Containerize applications for improved resource allocation and management.

Infrastructure Enhancements:

- Implement advanced cooling systems, such as liquid cooling for high-density computing clusters [10].

- Deploy AI-controlled cooling management systems that dynamically adjust based on workload and environmental conditions [7].

- Optimize data center layout with hot/cold aisle containment to improve airflow efficiency.

Phase 3: Monitoring and Continuous Improvement

- Establish Key Metrics: Track PUE, performance per watt, and total energy consumption per research project.

- Implement Policy Framework: Develop procurement standards favoring energy-efficient equipment and research protocols that prioritize computational efficiency.

- Workload Scheduling: Align non-time-sensitive computations with periods of renewable energy availability and off-peak electricity rates.

The Researcher's Toolkit

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Key Reagents and Materials for Sustainable Research

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Sustainable Application |

|---|---|---|

| Nickel Catalysts | Catalyze conversion of simple feedstocks to complex molecules | Air-stable alternatives to sensitive catalysts eliminate need for energy-intensive storage [11] |

| Bio-Based Ingredients | Replacement for fluorinated compounds | PFAS-free fire suppression foam reduces environmental persistence [11] |

| Enzyme Cascades | Biocatalytic synthesis | Replaces multi-step chemical synthesis routes (e.g., Merck's islatravir process) [11] |

| Safer Solvents | Reaction media | Bio-based or less hazardous alternatives with improved environmental profiles [9] |

| High-Efficiency GPU Clusters | Computational processing | Specialized hardware for AI training and molecular modeling with better performance per watt [10] |

Assessment and Optimization Workflows

The following workflow diagrams illustrate systematic approaches for implementing green principles in both wet laboratory and computational research settings:

Green Chemistry Method Development Workflow

Energy-Efficient Computing Workflow

Interdisciplinary Applications and Case Studies

Pharmaceutical Industry Applications

The pharmaceutical sector has emerged as a leader in implementing green chemistry principles, driven by both environmental concerns and economic benefits. Notable examples include:

Merck's Biocatalytic Process for Islatravir: Merck replaced a 16-step chemical synthesis route for the HIV-1 treatment islatravir with a single biocatalytic cascade involving nine enzymes that convert glycerol into the target molecule in a single aqueous stream [11]. This innovation eliminated organic solvents, intermediate isolations, and workups, dramatically reducing waste and energy consumption while improving overall efficiency.

Safer Solvent Implementation: Pharmaceutical manufacturers have successfully applied solvent selection guides to replace hazardous solvents with safer alternatives across multiple manufacturing processes [9]. The ACS GCI Pharmaceutical Roundtable's solvent selection tool enables researchers to systematically evaluate solvents based on health, safety, and environmental criteria, facilitating evidence-based solvent substitution.

Computational Research Optimization

Global Trust Bank AI Workload Optimization: Faced with skyrocketing energy costs from expanding AI and analytics workloads, Global Trust Bank implemented a comprehensive energy-efficient computing program that deployed purpose-built AI accelerators delivering 5x more performance per watt compared to general-purpose servers [7]. Additional optimizations included workload scheduling aligned with renewable energy availability and liquid cooling for high-density computing clusters, reducing cooling energy by 45% while improving processing times by 35%.

FEDGPU's Green Computing Platform: FEDGPU has developed a distributed GPU network powered by renewable energy and optimized through intelligent scheduling systems [10]. Their approach demonstrates how specialized hardware combined with AI-driven resource management can significantly reduce the environmental impact of computational research while maintaining performance.

Cross-Disciplinary Integration

The most significant sustainability gains often occur at the intersection of green chemistry and energy-efficient computing:

AI-Guided Material Discovery: Researchers at MIT are using AI systems to accelerate the development of advanced materials for energy applications, including batteries, solar cells, and nuclear reactors [12]. AI algorithms guide experimental design, predict material properties, and optimize synthesis conditions, dramatically reducing the time and resources required for materials development.

Predictive Maintenance for Research Equipment: AI-enabled monitoring of laboratory equipment can predict maintenance needs before failures occur, reducing downtime, extending equipment lifespan, and preventing wasted resources from failed experiments [12].

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The integration of sustainability principles into research methodologies continues to evolve with several promising developments:

Carbon-Aware Computing: The next frontier in computational sustainability involves optimizing not just for energy consumption but for carbon impact, considering factors like the carbon intensity of available energy sources at different times and the embodied carbon in manufacturing and disposing of IT equipment [7].

Advanced Green Metrics: Development continues on more comprehensive assessment tools that evaluate the entire lifecycle of research processes, from raw material extraction to waste disposal [8]. The ideal metrics would integrate both chemical and computational environmental impacts into a unified scoring system.

Circular Economy Integration: Both green chemistry and computing are increasingly incorporating circular economy principles, focusing on waste valorization, material recycling, and designing processes for easy disassembly and reuse of components [13].

AI for Sustainability Optimization: Artificial intelligence is being deployed to optimize both chemical processes and computational workflows for sustainability, creating a virtuous cycle where AI improves its own environmental performance while enhancing research efficiency [12].

For research institutions and pharmaceutical companies, the strategic integration of these green principles offers not only environmental benefits but also significant competitive advantages through reduced operational costs, improved research efficiency, and enhanced regulatory compliance.

In modern research, quantifying the environmental impact of laboratory operations has transitioned from an optional consideration to a fundamental component of responsible science. Laboratories are resource-intensive environments, consuming up to ten times more energy and four times more water than typical office spaces [14]. The scientific community has responded to this challenge by developing sophisticated metrics and tools that enable researchers to measure, manage, and mitigate their environmental footprint systematically. For researchers in drug development and other scientific fields, understanding these assessment frameworks is crucial for aligning research practices with sustainability goals without compromising scientific quality or productivity.

This guide provides a comprehensive overview of the current landscape of laboratory impact assessment tools, focusing on practical implementation strategies for researchers seeking to integrate sustainability metrics into their experimental planning and laboratory management practices. The evolution of these tools reflects a growing recognition that sustainable science is not only ethically responsible but also often correlates with increased efficiency, cost savings, and enhanced scientific innovation.

Foundational Concepts and Assessment Frameworks

The RGB Model and White Analytical Chemistry

The RGB model forms the conceptual foundation for many modern assessment approaches, organizing evaluation criteria into three distinct color-coded dimensions:

- Red (Analytical Performance): Assesses traditional method validation parameters including sensitivity, precision, accuracy, and selectivity.

- Green (Environmental Impact): Evaluates ecological factors such as waste generation, energy consumption, reagent toxicity, and operator safety.

- Blue (Practicality): Focuses on practical implementation aspects including cost, time, operational complexity, and integration with existing workflows [15].

The integration of these three dimensions aims to achieve what is known as White Analytical Chemistry (WAC) – a balanced approach that reconciles environmental responsibility with methodological functionality and practical applicability [15]. This holistic framework acknowledges that sustainable science requires optimizing across multiple competing priorities rather than focusing exclusively on any single dimension.

The Need for Standardized Assessment

Despite the proliferation of assessment tools, the field currently lacks universal standardization, leading to potential inconsistencies in evaluation outcomes. As Nowak (2025) observes, "one can have an impression that the assessments made currently may deliver additional information that nicely complements analytical validation, but sometimes, it only creates unnecessary confusion" [16]. This fragmentation underscores the importance of following established guidelines such as the proposed Good Evaluation Practice (GEP) rules, which emphasize transparency, empirical data, and critical interpretation of results [16].

Comprehensive Metric Classification and Comparison

Holistic Assessment Frameworks

| Tool Name | Assessment Focus | Key Parameters | Output Format | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RGB Model [15] | Comprehensive (Red, Green, Blue) | Analytical performance, environmental impact, practicality | Combined score | General method evaluation |

| VIGI [15] | Innovation strength | 10 criteria including sample prep, instrumentation, automation, interdisciplinary | 10-pointed star with violet intensities | Innovation potential assessment |

| GLANCE [15] | Method communication | 12 blocks including novelty, reagents, instrumentation, validation | Canvas-based visualization template | Method description & reporting |

| GEP [16] | Evaluation quality | Empirical data, transparency, critical interpretation | Guidelines framework | Assessment process standardization |

Greenness-Specific Evaluation Tools

| Tool Name | Basis of Assessment | Scoring System | Visual Output | Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGREE [15] [17] | 12 Principles of GAC | 0-1 scale | Circular diagram | Direct GAC principle alignment |

| AGREEprep [15] | Sample preparation | 0-1 scale | Circular diagram | Sample preparation focus |

| AGSA [17] | 12 Principles of GAC | Built-in scoring | Star-shaped diagram | Method classification, bias resistance |

| Analytical Eco-Scale [17] | Penalty points | Penalty-based | Numerical score | Simplicity, quantitative result |

| GAPI [17] | Multi-criteria | Qualitative assessment | Pictogram | Comprehensive life cycle assessment |

| NEMI [16] | 4 basic criteria | Pass/fail per criterion | Pictogram | Simplicity, rapid assessment |

Complementary Specialized Metrics

| Tool Name | Focus Area | Companion To | Key Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| BAGI [15] | Practical applicability | RGB blue component | Quantifies practical implementation aspects |

| RAPI [15] | Analytical performance | RGB red component | Systematically evaluates analytical parameters |

| GEMAM [15] | Environmental impact | Green metrics | Alternative greenness assessment |

| CACI [15] | Click chemistry | Specialized applications | Evaluates click chemistry methods |

Methodologies for Implementation

Systematic Assessment Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the recommended methodology for implementing a comprehensive laboratory impact assessment:

Good Evaluation Practice Rules

Implementing the Good Evaluation Practice framework ensures assessment quality and reliability [16]:

Utilize Quantitative Indicators: Prioritize empirical, directly measurable data over estimates where possible, including electricity consumption (measured with wattmeters), actual waste volumes, and precise reagent quantities.

Combine Complementary Tools: Employ multiple assessment models with different structures to compensate for individual limitations and obtain a more balanced perspective.

Maintain Critical Perspective: Recognize that all metrics incorporate arbitrary assumptions and discretization that may not perfectly align with specific contexts.

Ensure Full Transparency: Document all data sources, assumptions, calculation methods, and potential limitations to enable reproducibility and critical evaluation.

Contextualize Results: Interpret findings relative to methodological requirements and practical constraints rather than treating metrics as absolute arbiters of sustainability.

Practical Implementation Strategies

Successful integration of sustainability assessment into laboratory workflows requires both technical and cultural approaches:

Establish Baseline Measurements: Before implementing improvements, conduct comprehensive audits of energy consumption, waste generation, water usage, and chemical utilization to establish reference points [18] [19].

Implement Equipment Monitoring: Use smart sensors for real-time tracking of temperature, humidity, energy consumption, and equipment usage patterns to identify optimization opportunities [19].

Develop Shared Resources: Create equipment sharing systems, centralized chemical inventories, and joint purchasing programs to reduce redundant procurement and associated environmental impacts [18] [19] [20].

Integrate Assessment Early: Incorporate sustainability metrics during method development phases rather than as retrospective evaluations to maximize impact and avoid costly redesigns [20].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Category | Function/Purpose | Sustainability Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) [21] | Customizable, biodegradable extraction media | Replace volatile organic compounds; reduce toxicity and waste |

| Bio-Based Surfactants [21] | PFAS-free alternatives for manufacturing | Eliminate persistent pollutants; use rhamnolipids/sophorolipids |

| Water-Based Reaction Systems [21] | Replacement for organic solvents | Utilize water's unique properties for catalysis; reduce toxicity |

| Air-Stable Nickel Catalysts [22] | Replace precious metal catalysts | Eliminate energy-intensive storage; utilize abundant elements |

| Enzyme Cascades [22] | Multi-step biocatalytic processes | Reduce synthetic steps, solvents, and energy consumption |

| Mechanochemical Reactants [21] | Solvent-free synthesis using mechanical energy | Eliminate solvent waste; enhance safety and efficiency |

Common Challenges and Solutions

Tool Selection and Application Barriers

Researchers often face significant challenges when implementing sustainability assessments:

Proliferation of Overlapping Tools: The abundance of available metrics can create confusion. Solution: Begin with established, well-documented tools like AGREE for greenness assessment and complement with specialized tools as needed [15] [16].

Data Intensity Requirements: Comprehensive assessments require detailed operational data that may not be routinely collected. Solution: Implement standardized data collection protocols and leverage digital monitoring technologies to streamline this process [19] [16].

Resistance to Cultural Change: Laboratory personnel may perceive sustainability assessments as additional bureaucratic burdens. Solution: Integrate assessments into existing quality systems, demonstrate efficiency benefits, and provide education on both environmental and scientific benefits [18] [14].

Interpretation and Implementation Hurdles

Contextual Understanding: Metrics provide comparative scores but may not capture methodological necessities. Solution: Interpret results within specific application contexts and avoid overgeneralization [16].

Balancing Competing Priorities: Optimizing one dimension (e.g., greenness) may compromise others (e.g., analytical performance). Solution: Use multi-dimensional frameworks like RGB to identify balanced solutions [15].

Resource Constraints: Implementation requires time and potentially financial investment. Solution: Leverage shared resources, institutional support programs, and focus on high-impact, low-cost interventions initially [19] [20].

Future Directions and Innovations

The field of laboratory sustainability assessment continues to evolve with several promising developments:

Digital Integration and AI: Emerging platforms incorporate artificial intelligence to provide real-time sustainability scoring, predictive modeling of environmental impacts, and automated optimization suggestions [15] [23].

Standardization Initiatives: Efforts such as the PRISM framework aim to establish consistency across assessment tools, improving comparability and reliability [15].

Unified Dashboard Systems: Integrated digital dashboards that combine multiple metric outputs are in development, allowing researchers to visualize comprehensive sustainability profiles through single interfaces [15].

Educational Integration: Sustainability assessment is increasingly incorporated into scientific training programs, building foundational knowledge for emerging researchers [20].

For researchers embarking on sustainability assessment, the most effective approach involves selecting appropriate tools based on specific methodological characteristics, implementing systematic data collection procedures, interpreting results within relevant scientific contexts, and viewing assessment as an iterative improvement process rather than a one-time compliance exercise.

Regulatory and Stakeholder Drivers for Sustainability

The landscape of corporate sustainability is undergoing a significant transformation. The drivers compelling organizations to adopt environmentally sustainable practices are shifting from a primary focus on regulatory compliance to a broader emphasis on operational efficiency, cost savings, and strategic stakeholder engagement [24]. This evolution reflects a maturation of corporate sustainability strategies, where environmental responsibility is increasingly viewed as integral to long-term profitability and resilience rather than merely a compliance obligation. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding this shift is crucial. It necessitates a move beyond simply tracking environmental footprint metrics to demonstrating tangible financial savings and operational benefits from sustainability investments [24]. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of these drivers and equips researchers with a toolkit of greenness assessment methodologies to quantify and validate the environmental impact of their work, aligning scientific innovation with both planetary health and economic imperatives.

Deconstructing the Key Drivers

The Regulatory Framework

Regulatory pressure remains a potent force shaping corporate environmental strategies. Globally, the shift from voluntary to mandatory sustainability reporting is accelerating, creating a complex web of compliance requirements [25].

- Leading Regulatory Frameworks: The Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) in Europe is setting a high benchmark for detailed disclosure standards, affecting both EU-based companies and non-EU firms with significant operations in the region [25]. In the United States, despite a fragmented federal approach, state-level initiatives like California’s climate disclosure laws are creating de facto national standards for many large corporations [25].

- Corporate Priorities: A 2025 survey of C-Suite executives reveals that climate risk and sustainability are among the top external ESG factors likely to impact their businesses [25]. This reflects the materialization of climate-related risks, from extreme weather disrupting supply chains to rising insurance premiums [25].

Table 1: Key Environmental Regulations and Their Corporate Impact

| Regulation / Policy | Region | Core Focus | Perceived Business Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) [25] | European Union | Comprehensive sustainability disclosure | High in Europe; significant for global firms with EU operations |

| California Climate Disclosure Laws [25] | United States (California) | Climate risk and emissions reporting | High for US-based and multinational companies |

| Circular Economy Action Plan [25] | European Union | Waste reduction, recycling, and product lifecycle | High in Europe; a growing focus in the US |

| Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) [26] | Global (varying by country) | Producer responsibility for post-consumer product disposal | Medium to High, depending on sector and jurisdiction |

The Stakeholder Ecosystem

Stakeholder theory posits that businesses are significantly influenced by diverse groups, including governments, investors, customers, and NGOs [27]. Their collective pressure is a critical driver of green innovation and sustainable practices.

- Effectiveness and Context: A 2025 meta-analysis of 23 studies confirms that stakeholder pressure has a generally positive impact on green innovation [27]. However, this relationship is not uniform. The effect is often weaker in manufacturing sectors and in specific national contexts like China, highlighting the moderating role of industry-specific constraints (e.g., technical, operational, financial) and regional socio-economic factors [27].

- Building Trust: Effective stakeholder engagement is paramount. Recent research indicates that Corporate Affairs professionals view direct, in-person dialogue and transparent communication as the most innovative and effective methods for building trust with skeptical stakeholders, surpassing digital or AI-enabled engagement [28]. This underscores the importance of authentic, human-centered approaches in sustainability strategy.

Table 2: Stakeholder Influence on Corporate Sustainability

| Stakeholder Group | Primary Lever of Influence | Exemplary Demands |

|---|---|---|

| Government & Regulators [27] | Legislation, penalties, and reporting mandates | Compliance with CSRD, emissions tracking, waste management |

| Investors [25] | Capital allocation and ESG scoring | Disclosure of climate risks, progress toward net-zero targets |

| Customers [29] | Purchasing decisions and brand loyalty | Sustainable sourcing, eco-friendly products, transparent labeling |

| Employees & Unions [24] | Labor conditions and corporate advocacy | Climate adaptation protections for workers, sustainable workplace practices |

| Local Communities & NGOs [27] | Social license to operate and public campaigns | Water management, biodiversity protection, fair operational practices |

The Researcher's Toolkit: Greenness Assessment Tools

For researchers and scientists, translating high-level regulatory and stakeholder drivers into actionable, measurable outcomes at the laboratory level requires specialized assessment tools. These "greenness metrics" provide a standardized methodology to evaluate the environmental impact of scientific processes, particularly in fields like natural product extraction and analytical chemistry.

The Green Extraction Tree (GET): A Novel Metric for Natural Products Research

The Green Extraction Tree (GET) is a comprehensive and intuitive evaluation tool specifically designed to assess the greenness of the sample preparation process in the green extraction of natural products [30]. It integrates the 10 principles of green sample preparation with the 6 principles of green extraction of natural products, creating a holistic assessment framework [30].

Experimental Protocol for GET Assessment:

- Define the Extraction Process: Clearly outline all unit operations involved in the extraction process, from raw material pretreatment to extract post-treatment.

- Gather Process Data: Collect quantitative and qualitative data for each of the 14 criteria across the six core aspects (Sample, Solvent & Reagent, Energy, Byproducts & Waste, Process Risk, and Extract Quality). Key metrics include:

- Renewable Materials: Percentage of sustainable raw materials and solvents (e.g., ethanol from sugar cane vs. petroleum-derived methanol) [30].

- Energy Consumption: Total energy used, quantified in kWh per sample [30].

- Solvent Toxicity: Graded using standardized scores like the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) code [30].

- Waste Generation: Mass of waste produced per mass of extract.

- Apply the GET Scoring System: For each criterion, assign a color and numerical value based on the gathered data:

- Green (2 points): Low environmental impact (e.g., using >50% renewable materials).

- Yellow (1 point): Medium environmental impact.

- Red (0 points): High environmental impact (e.g., using <50% renewable materials) [30].

- Generate the GET Pictogram: Use an open-access toolkit to create the "tree" pictogram. The six "trunks" represent the core aspects, and the colored "leaves" represent the individual criteria scores [30].

- Interpretation and Horizontal Comparison: Calculate a final aggregate score. This score allows for the comparison of different extraction methods, identifying both the overall greenness and specific aspects of the process that require improvement [30].

GET Assessment Workflow: A systematic process for evaluating the greenness of natural product extraction methods.

Comparative Analysis of Greenness Assessment Tools

While GET is specialized for natural product extraction, several other metrics exist for broader analytical and computational chemistry applications. The table below summarizes key tools relevant to research scientists.

Table 3: Greenness Assessment Tools for Scientific Research

| Tool Name | Primary Application Scope | Key Assessment Criteria | Output Format |

|---|---|---|---|

| Green Extraction Tree (GET) [30] | Natural Product Extraction | 14 criteria across 6 aspects: sample, solvents, energy, waste, risk, quality | "Tree" pictogram with color codes & quantitative score |

| Analytical Eco-Scale [30] | Analytical Chemistry | Penalty points assigned for reagents, energy, waste not meeting ideal | Total score out of 100 (higher = greener) |

| GAPI & Modified GAPI [30] | Entire Analytical Method | Five pictograms evaluating steps from sample collection to final product | Symbol with colored segments |

| AGREEprep [30] | Sample Preparation | Weighted scoring of solvents, reagents, waste, energy, throughput | Circular pictogram with a final score |

| CodeCarbon [4] | Computational / AI Workloads | CPU, GPU, and RAM usage combined with regional carbon intensity | Estimated CO₂ emissions (kg) |

Advanced Tools and Future Directions

Green Coding for Computational Research

For researchers relying on computationally intensive tasks (e.g., bioinformatics, molecular modeling, AI-driven drug discovery), the carbon footprint of code is a significant sustainability concern. Tools like CodeCarbon, Eco2AI, and CarbonTracker have been developed to monitor energy consumption and estimate CO₂ emissions from computing hardware [4]. These Python libraries can be integrated into training loops and workflows, providing insights that allow scientists to optimize algorithms for lower environmental impact or schedule heavy computations for times when the local energy grid relies more on renewable sources [4].

Emerging Technological Enablers

Beyond assessment, new technologies are actively reducing the environmental footprint of industrial and research activities. A 2025 World Economic Forum report highlights several breakthrough innovations with profound implications [31]:

- AI-supported Earth Observation: Provides near-real-time, high-resolution tracking of environmental changes, enabling precision agriculture and better monitoring of ecological impacts [31].

- Automated Food Waste Upcycling: Uses AI and robotics to sort and separate organic waste, converting it into compost or biogas and reducing landfill methane emissions [31].

- Green Concrete: Offers a sustainable alternative to traditional cement, with some technologies capable of actively sequestering captured CO₂ during the curing process [31].

Integrated Sustainability Workflow for Researchers

Combining an understanding of macro-drivers with practical micro-level tools allows researchers to build a comprehensive sustainability strategy.

Sustainability Integration Pathway: Connecting external pressures to actionable lab strategies and positive outcomes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Greenness Assessment

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Green Metrics

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Assessment | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| GET Open-Access Toolkit [30] | Generates the visual "tree" pictogram and calculates final greenness score. | Evaluation of natural product extraction methods. |

| Regional Carbon Intensity Data [4] | Converts energy consumption (kWh) into CO₂ emissions (kg). | Calculating the carbon footprint of computational research. |

| NFPA (National Fire Protection Association) Codes [30] | Provides standardized scores for chemical toxicity, flammability, and reactivity. | Assessing the "Process Risk" and solvent safety in GET and other metrics. |

| Lifecycle Assessment (LCA) Software [26] | Models the environmental impact of a product or process across its entire lifecycle. | Broader sustainability analysis of novel materials or pharmaceuticals. |

| AI-Powered Analytics Platforms [31] | Synthesizes complex data (e.g., satellite, sensor) to track environmental impacts. | Large-scale ecological monitoring and resource management. |

The paradigm for corporate and research sustainability is decisively shifting. The primary drivers are expanding from a narrow compliance-based model to a multi-stakeholder value proposition where operational efficiency, cost savings, and authentic engagement are paramount [24] [25]. For the scientific community, this translates to an imperative not only to innovate but to do so sustainably. The adoption of standardized greenness assessment tools, such as the Green Extraction Tree for laboratory processes or CodeCarbon for computational work, provides the rigorous, quantitative evidence needed to demonstrate this alignment. By integrating these methodologies into core research and development activities, scientists and drug development professionals can effectively respond to regulatory and stakeholder pressures, while simultaneously unlocking economic benefits and contributing to a more sustainable future.

Implementing Green Tools: A Practical Toolkit for Researchers

The integration of Green Chemistry principles into pharmaceutical research represents a paradigm shift toward more sustainable and efficient drug discovery processes. The application of these principles is particularly impactful in the fields of late-stage functionalization (LSF) and reaction miniaturization, which enable chemists to rapidly explore chemical space while minimizing environmental impact and resource consumption. LSF strategies allow for the direct installation of functional groups onto complex, drug-like molecules, providing a powerful approach for structural diversification and structure-activity relationship (SAR) profiling without the need for lengthy de novo syntheses. When combined with miniaturization techniques that drastically reduce solvent and reagent usage, these approaches represent a convergence of synthetic efficiency and sustainability that aligns perfectly with the goals of green chemistry.

The fundamental challenge in modern medicinal chemistry lies in balancing the need for rapid compound diversification with the increasing imperative to reduce the environmental footprint of research activities. Traditional synthetic approaches often involve multi-step sequences that generate significant waste and consume substantial resources. Green chemistry principles address these concerns through frameworks such as the Twelve Principles of Green Chemistry and quantitative assessment tools that help researchers make informed decisions about their synthetic strategies. For new researchers, understanding and implementing these tools is becoming increasingly essential, as regulatory bodies and academic institutions place greater emphasis on sustainable research practices. In fact, the American Chemical Society (ACS) will begin assessing for its green chemistry and sustainability requirements in 2026, making this knowledge immediately relevant for current research programs [32].

Late-Stage Functionalization as a Green Strategy

Fundamental Concepts and Green Chemistry Advantages

Late-stage functionalization refers to the direct chemical modification of complex, highly functionalized molecules, typically in the final steps of a synthetic sequence. This approach offers significant green chemistry advantages over traditional synthetic methods by avoiding lengthy de novo synthesis pathways and reducing overall material consumption. The "magic methyl" effect exemplifies the power of LSF, where installation of a single methyl group—often distal to the binding motif—can dramatically improve pharmacological properties including potency, solubility, and metabolic stability [33]. Beyond methyl groups, other privileged motifs such as fluoro, chloro, trifluoromethyl, and hydroxyl groups can be incorporated via LSF to optimize drug candidates [33].

From a green chemistry perspective, LSF aligns with multiple principles of sustainable chemistry: it atom economy by minimizing synthetic steps and protecting group manipulations; reduces waste by streamlining synthetic sequences; and saves energy by avoiding lengthy purification processes between steps. The most common LSF methodologies include Minisci-type functionalizations (radical additions to electron-deficient heteroarenes), P450-catalyzed oxidations, electrochemical methods, and photoredox catalysis [33]. These methods enable diversification of lead compounds from existing synthetic intermediates, significantly reducing the material and energy inputs required for SAR exploration.

Predictive Machine Learning for Greener LSF Outcomes

A significant challenge in LSF is predicting and controlling regioselectivity in complex molecular environments. Traditional approaches rely on computational methods such as Fukui-based reactivity indices or expert-guided rules, but these often struggle with the structural complexity of drug-like molecules. Recent advances in machine learning (ML) offer powerful solutions to this challenge, enabling more accurate predictions and reducing the need for extensive experimental screening that consumes reagents and generates waste [33].

Message passing neural networks (MPNNs), a subset of graph convolutional neural networks, have emerged as particularly effective tools for predicting LSF outcomes. These models represent molecules as graphs with atoms as nodes and bonds as edges, transmitting structural information across the molecular framework. After sufficient message passes, each atom possesses comprehensive information about its local environment, enabling accurate predictions of reactivity patterns [33]. This approach has been successfully applied to predict the regioselectivity of diverse LSF transformations, including Minisci-type reactions and P450-based functionalizations, outperforming traditional Fukui function-based indices [33].

The green chemistry benefits of these predictive models are substantial. By accurately forecasting reaction outcomes, researchers can minimize failed experiments, reduce reagent consumption, and decrease waste generation. Furthermore, the integration of transfer learning approaches using existing 13C NMR data allows these models to function effectively even with limited LSF-specific training data, reducing the need for extensive experimental data collection [33]. This represents a convergence of computational and experimental approaches that inherently supports greener research practices.

Table 1: Comparison of LSF Prediction Methods

| Method | Key Features | Accuracy | Green Chemistry Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fukui Function-Based Indices | Describes electron density changes; established guidelines | ~93% site identification (average F-score 0.77) | Reduces trial experiments; works for small molecules |

| Message Passing Neural Networks (MPNNs) | Graph-based; no pre-computed properties needed; uses 13C NMR transfer learning | Outperforms Fukui and other ML models | Minimizes failed reactions; reduces reagent waste across complex molecules |

| Quantum Chemical Approaches | Computes energy barriers via DFT | High accuracy for specific cases | Computational prediction replaces some experimental screening |

| Expert-Guided Rules | Based on empirical observations | Variable depending on molecular complexity | Leverages existing knowledge without additional resources |

Quantitative Green Chemistry Evaluation Tools

DOZN 3.0: A Comprehensive Green Metrics Evaluator

Quantitative assessment is essential for implementing and validating green chemistry approaches. DOZN 3.0, developed by Merck, serves as a comprehensive evaluator that facilitates the assessment of resource utilization, energy efficiency, and reduction of hazards to human health and the environment [34]. This web-based tool provides researchers with a systematic method for evaluating chemical processes and materials against the Twelve Principles of Green Chemistry, which are grouped into three broader categories: better resource use, human and environmental health, and energy efficiency.

The value of DOZN 3.0 lies in its ability to provide quantitative comparisons between different synthetic routes or processes, enabling researchers to make data-driven decisions that optimize for sustainability alongside traditional metrics such as yield and purity. For new researchers, this tool offers a structured framework for understanding how specific modifications—such as implementing LSF strategies or miniaturizing reactions—contribute to overall green chemistry goals. The system generates numerical scores across multiple green chemistry principles, allowing for benchmarking against industry standards or previous process iterations.

Green Chemistry Principles and Application to LSF

The Twelve Principles of Green Chemistry provide a comprehensive framework for designing chemical products and processes that reduce or eliminate the use and generation of hazardous substances. For LSF and miniaturization strategies, several principles are particularly relevant:

- Atom Economy: LSF improves atom economy by enabling direct introduction of functional groups without the need for multi-step protection/deprotection sequences.

- Prevention of Waste: Miniaturization dramatically reduces solvent and reagent consumption at the research stage.

- Reduced Hazardous Syntheses: Predictive ML models help identify safer reaction pathways before laboratory experimentation.

- Safer Solvents and Auxiliaries: Solvent selection guides facilitate choices that reduce environmental and health impacts.

- Design for Energy Efficiency: Miniaturized reactions often require less energy for heating, cooling, and mixing.

- Use of Renewable Feedstocks: This principle encourages consideration of starting material sustainability alongside synthetic efficiency.

These principles provide new researchers with a systematic approach for evaluating and improving their experimental designs, with tools like DOZN 3.0 offering quantitative support for these assessments [34].

Practical Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Miniaturization Techniques for Green Chemistry

Reaction miniaturization represents a powerful strategy for reducing the environmental impact of chemical research, particularly during early-stage exploration where numerous conditions must be screened. The green chemistry benefits of miniaturization include dramatic reductions in solvent consumption, decreased reagent usage, lower energy requirements for temperature control and mixing, and reduced waste generation. Modern miniaturization approaches include:

- High-throughput experimentation (HTE) in microtiter plates with reaction volumes as low as 100-500 μL

- Flow chemistry systems that enable precise control of reaction parameters with minimal reagent use

- Microwave-assisted synthesis in sealed vessels that reduces solvent requirements while improving energy efficiency

- Automated parallel synthesis systems that allow efficient screening of multiple reaction conditions with minimal material input

When combining miniaturization with LSF strategies, researchers can achieve unprecedented efficiency in compound diversification while maintaining green chemistry principles. For example, screening multiple Minisci-type functionalization conditions on a single molecular scaffold using miniaturized techniques can reduce solvent consumption by over 95% compared to traditional flask-based approaches.

Experimental Protocol: Predictive Minisci-Type LSF with ML Guidance

The following detailed protocol integrates machine learning prediction with experimental validation for greener LSF implementation:

Step 1: Substrate Preparation and Input

- Begin with purified lead compound (0.1-0.5 mmol scale for initial validation)

- For ML prediction: Generate SMILES string of substrate structure

- Submit structure to predictive MPNN model (available via GitHub repository: https://github.com/emmaking-smith/SETLSFCODE) [33]

- Model requires only basic atomic information: atomic number, hydrogen acceptor/donor status, hybridization, aromaticity, and number of explicit hydrogens [33]

Step 2: Reaction Condition Selection

- Based on desired functionalization, select appropriate LSF method:

- Minisci-type alkylation: Baran Diversinates (commercially available kits), silver nitrate catalyst, peroxydisulfate oxidant, acidic conditions (0.1 M TFA in water:acetonitrile 1:1) [33]

- P450-catalyzed oxidation: Engineered cytochrome P411 variants, hydrogen peroxide or oxygen as oxidant, NADPH recycling system

- Photoredox alkylation: Ir(ppy)₃ or [Ru(bpy)₃]²⁺ photocatalyst, blue LED illumination, alkyltrifluoroborate reagents

- Apply one-hot encoding for specific reagents, oxidants, solvents, and additives to create reaction vector input for MPNN model [33]

Step 3: Miniaturized Reaction Setup

- Perform reactions in 96-well microtiter plates with 0.01-0.05 mmol substrate per well

- Use liquid handling robotics for precise reagent addition (total reaction volume: 200-500 μL)

- For Minisci reactions: Maintain inert atmosphere with nitrogen sparging

- Implement parallel temperature control with aluminum heating blocks

Step 4: Reaction Monitoring and Analysis

- Track reaction progress via UPLC-MS with partial loop injection (1-2 μL sample consumption)

- For regiochemical determination: Employ LC-NMR for unambiguous structural assignment

- Compare experimental results with MPNN predictions to refine model accuracy

Step 5: Product Purification and Characterization

- Scale-up successful conditions (0.5-1.0 mmol) for compound isolation

- Employ automated flash chromatography or preparative HPLC for purification

- Utilize green solvent alternatives (cyclopentyl methyl ether, 2-methyltetrahydrofuran) in purification protocols

- Confirm structure and purity via NMR, HRMS, and HPLC analysis

This integrated approach significantly reduces the traditional trial-and-error associated with LSF development, minimizing reagent waste while maximizing successful outcomes.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Green LSF and Miniaturization

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in LSF/Miniaturization | Green Chemistry Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diversinate Kits | Baran Diversinates | Pre-formulated reagent kits for common LSF transformations | Redces excess reagent use; improves reproducibility; minimizes waste |

| Safer Solvents | 2-MeTHF, CPME, cyclopentyl methyl ether | Reaction media for functionalization | Renewable feedstocks; reduced hazardous waste; better recycling potential |

| Solvent Selection Guide | Beyond Benign's Greener Solvent Guide | Visual reference for solvent substitution | Promotes safer solvent choices; educational tool for students |

| Photoredox Catalysts | Ir(ppy)₃, [Ru(bpy)₃]²⁺, organic photoredox catalysts | Enable visible-light-driven LSF under mild conditions | Reduced energy requirements; often catalytic quantities sufficient |

| Biocatalytic Systems | Engineered P450 enzymes (P411 variants) | Selective C-H functionalization under mild conditions | Biodegradable catalysts; aqueous reaction media; high selectivity reduces waste |

| Hazard Assessment Tools | ChemFORWARD database | Identify chemical hazards and safer alternatives | Prevents regrettable substitutions; builds foundational knowledge |

Visualization of Workflows and Relationships

The following diagrams illustrate key workflows and relationships in green chemistry applications for LSF and miniaturization, created using DOT language with the specified color palette and contrast requirements.

Green LSF Prediction and Experimental Workflow

Green Chemistry Assessment Framework

The integration of late-stage functionalization strategies with reaction miniaturization techniques represents a powerful convergence of synthetic efficiency and green chemistry principles. For new researchers, the available toolkit—including predictive machine learning models, quantitative assessment frameworks like DOZN 3.0, and educational resources from organizations like Beyond Benign—provides a robust foundation for implementing sustainable research practices from the outset of their careers [32] [33] [34]. The increasing regulatory emphasis on green chemistry, exemplified by the ACS's upcoming sustainability assessment requirements, further underscores the importance of these approaches in modern chemical research [32].

The most successful implementations combine computational prediction with experimental validation in miniaturized formats, creating a virtuous cycle where each informed experiment generates data that further refines predictive models. This approach not only advances the core scientific goals of reaction development and compound optimization but does so while dramatically reducing the environmental footprint of pharmaceutical research. As these methodologies continue to evolve, they promise to make sustainable research practices an integral component of drug discovery rather than an ancillary consideration, ultimately leading to more efficient and environmentally responsible scientific progress.

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) into chemical research represents a paradigm shift toward computational sustainability. These technologies are revolutionizing how researchers design experiments, optimize reactions, and develop new materials while minimizing environmental impact. AI serves as a powerful tool for achieving greener chemical processes by enabling predictive modeling, virtual screening, and data-driven optimization that reduce the need for resource-intensive trial-and-error experimentation in the laboratory [12]. The core value proposition lies in AI's ability to extract meaningful patterns from complex chemical data, accelerating the discovery of efficient reactions and sustainable materials that might otherwise take decades to identify using traditional methods [35].

This transformation is particularly evident in the chemical industry's efforts to reconcile industrial productivity with environmental stewardship. From pharmaceutical development to energy storage solutions, AI and ML are providing researchers with sophisticated computational tools to maximize synthetic efficiency, atom economy, and minimize waste production [36]. The resulting methodologies align closely with the principles of green chemistry by enabling processes that consume less energy, utilize safer reagents, and generate fewer hazardous byproducts. As research in this field advances, computational sustainability is emerging as a critical framework for addressing some of the most pressing environmental challenges through chemistry innovation.

Key Application Areas

Catalyst Design and Discovery

Catalysts are fundamental to modern chemistry, influencing over 90% of chemical processes by accelerating reactions, reducing energy requirements, and enabling transformations that would otherwise be impractical [35]. Traditional catalyst discovery has relied heavily on iterative laboratory experimentation—a slow and resource-intensive process. AI is transforming this paradigm through data-driven approaches that can virtually screen millions of potential catalyst configurations and predict performance characteristics before any synthesis occurs [35].

Machine learning models, including regression algorithms and neural networks, are trained on experimental data, simulations, and reaction outcomes to identify promising catalyst candidates based on target properties such as activity, selectivity, and stability [35]. This approach has demonstrated particular value in developing sustainable catalysts that utilize abundant, non-toxic materials while operating efficiently under milder reaction conditions [35]. For example, researchers at the University of Freiburg are employing AI to develop novel boronic acid catalysts for amidation reactions—processes that account for approximately 16% of all chemical industry operations [37]. Their AI-driven approach aims to create catalysts that enable amidation at room temperature using sustainable solvents, with water as the only byproduct [37].

Table 1: AI Approaches in Catalyst Design

| AI Technique | Application in Catalyst Design | Benefits |

|---|---|---|

| Machine Learning Regression Models | Predict catalyst activity and selectivity based on molecular features | Identifies structure-property relationships from existing data |

| Neural Networks | Capture non-linear relationships between catalyst structure and performance | Handles complex, multi-variable optimization problems |

| Generative AI | Proposes novel molecular structures meeting target reaction goals | Explores chemical space beyond human intuition |

| Reinforcement Learning | Optimizes catalyst performance through iterative virtual testing | Continuously improves predictions based on feedback loops |

Reaction Optimization and Synthesis Planning

AI and ML tools are revolutionizing reaction optimization by predicting optimal conditions, yields, and potential byproducts without extensive experimental testing. These computational approaches leverage large datasets of chemical reactions to build models that can recommend reaction parameters, solvent systems, and temperature profiles that maximize efficiency while minimizing environmental impact [38]. This capability is particularly valuable in pharmaceutical synthesis, where AI-driven optimization can significantly reduce the waste generated during drug development.