Process Mass Intensity in Pharma: A 2025 Guide to Metrics, Optimization, and Sustainable API Manufacturing

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Process Mass Intensity (PMI) for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Process Mass Intensity in Pharma: A 2025 Guide to Metrics, Optimization, and Sustainable API Manufacturing

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Process Mass Intensity (PMI) for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational role of PMI as a key green chemistry metric, explores advanced methodologies for its calculation and reduction, and presents real-world case studies in troubleshooting and optimization. The content also critically examines the validation of PMI against broader environmental impacts and discusses the integration of digital tools, novel technologies, and regulatory trends shaping the future of sustainable pharmaceutical manufacturing.

What is Process Mass Intensity? Defining the Core Metric for Sustainable Pharma

Process Mass Intensity (PMI) is a key green chemistry metric used to benchmark and quantify the efficiency and environmental performance of pharmaceutical manufacturing processes. It is defined as the total mass of inputs (e.g., solvents, reagents, raw materials) required to produce a unit mass of the final active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) [1]. PMI provides a comprehensive measure of resource efficiency and waste generation, helping scientists and engineers identify opportunities to develop more sustainable and cost-effective synthetic routes [1].

The ACS Green Chemistry Institute (ACS GCI) Pharmaceutical Roundtable has been instrumental in establishing PMI as a standard benchmarking tool within the industry. Since the first PMI benchmarking exercise in 2008, this metric has helped focus attention on the main drivers of process inefficiency, cost, and environmental, safety, and health impact [1]. The ongoing development of calculation tools, from simple PMI calculators to convergent PMI calculators that accommodate complex synthesis pathways, demonstrates the industry's commitment to standardized sustainability assessment [1].

PMI Calculation and Protocol

Fundamental Calculation Methodology

The standard PMI calculation follows a straightforward mass balance approach, comparing the total mass of all materials entering the process to the mass of the desired API produced.

PMI = Total Mass of Inputs (kg) / Mass of API (kg)

A PMI value of 1 represents an ideal, 100% efficient process where all input materials are incorporated into the final product. In reality, pharmaceutical processes typically have much higher PMI values due to solvents, reagents, and process materials that are not incorporated into the final molecule. The inverse of PMI × 100% gives the overall process atom economy [2].

Table 1: Components of PMI Calculation

| Component Category | Description | Included in PMI |

|---|---|---|

| Solvents | Reaction, workup, and purification solvents | Yes |

| Reagents | Chemical reactants not incorporated into API | Yes |

| Catalysts | Materials that facilitate reaction but not consumed | Yes |

| Water | Process water used in reactions, extractions, crystallizations | Yes |

| Raw Materials | Starting materials, intermediates incorporated into API | Yes |

| API Output | Final isolated active pharmaceutical ingredient | Denominator |

Experimental Protocol: Determining PMI for a Chemical Process

Principle: This protocol provides a standardized methodology for calculating Process Mass Intensity for pharmaceutical syntheses, enabling consistent benchmarking and sustainability assessment.

Materials and Equipment:

- Analytical balance (precision ±0.1 mg)

- Laboratory notebook or electronic data recording system

- Process flow diagram with identified input and output streams

- ACS GCI PMI Calculator or equivalent computational tool [1]

Procedure:

- Process Definition: Document the complete synthetic route, including all reaction steps, isolation procedures, and purification operations.

- Mass Inventory: Record the mass of all input materials for each process step, including:

- Starting materials and intermediates

- All solvents (reaction, extraction, crystallization)

- Reagents and catalysts

- Process water

- API Quantification: Precisely measure the mass of final isolated and purified API.

- Data Compilation: Sum the total mass of all input materials across all process steps.

- PMI Calculation: Apply the PMI formula using the compiled mass data.

- Data Recording: Document all input masses, API output, and calculated PMI value.

Notes:

- For convergent syntheses, use the Convergent PMI Calculator to properly account for parallel synthesis branches [1].

- The same methodology applies throughout development, from laboratory-scale reactions to commercial manufacturing.

- Record process conditions (yield, purity, reaction scale) for proper interpretation of PMI values.

Advanced Applications and Industry Implementation

Case Studies: PMI Reduction in Pharmaceutical Development

Recent industry awards highlight successful implementations of PMI principles in commercial pharmaceutical processes:

Case Study 1: Antibody-Drug Conjugate Linker Synthesis (Merck) A Merck team achieved approximately 75% reduction in PMI for manufacturing a complex ADC drug-linker through route redesign. The original 20-step synthetic sequence was replaced with a more efficient synthesis from a widely available natural product, cutting seven steps down to three. This PMI reduction was accompanied by a >99% decrease in energy-intensive chromatography time [3].

Case Study 2: Peptide Therapeutic Manufacturing (Olon S.p.A.) Olon developed a novel microbial fermentation platform that significantly improved PMI compared to conventional Solid Phase Peptide Synthesis (SPPS) methods. The technology reduces solvent and toxic material usage while eliminating protecting groups, demonstrating how alternative manufacturing approaches can enhance sustainability [3].

System Boundaries and Metric Evolution

The definition of system boundaries significantly impacts PMI calculations and their environmental relevance. Recent research has investigated how expanding system boundaries from gate-to-gate to cradle-to-gate affects PMI's correlation with life cycle assessment (LCA) environmental impacts [2].

Table 2: PMI System Boundaries and Interpretations

| System Boundary | Description | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Gate-to-Gate (Traditional PMI) | Considers only materials directly used in API manufacturing facility | Excludes upstream resource consumption in supply chain |

| Cradle-to-Gate (Value-Chain Mass Intensity) | Includes natural resources required to produce all input materials | Better correlates with environmental impacts but requires more data |

| Manufacturing Mass Intensity (MMI) | Expands PMI to include other raw materials required for API manufacturing | Broader scope driving more comprehensive sustainability assessment |

Recent studies demonstrate that expanding system boundaries strengthens the correlation between mass-based metrics and environmental impacts for 15 of 16 LCA impact categories [2]. This has led to the development of Manufacturing Mass Intensity (MMI), which builds upon PMI to account for additional resource requirements in API manufacturing [4].

Implementation Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions for PMI Optimization

Table 3: Essential Materials for Sustainable Process Development

| Reagent Category | Function | Green Chemistry Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Renewable Feedstocks | Starting materials from bio-based sources (e.g., furfural, amino acids) | Increase renewable carbon content; Corteva's process achieved 41% renewable carbon [3] |

| Green Solvents | Reaction media with favorable EHS profiles | Reduce PMI contribution from solvent use; water often preferred |

| Catalytic Systems | Efficient catalysts (including enzymatic) | Reduce stoichiometric reagent usage; enable atom-economic transformations |

| Analytical Tools | HPLC/UPLC, MS for reaction monitoring | Enable mass balance closure; identify impurities and yield optimization |

| HC Yellow no. 10 | HC Yellow No. 10|Nitro Hair Dye|For Research | High-purity HC Yellow No. 10 for research applications. A semi-permanent nitro hair dye. For Research Use Only. Not for personal or cosmetic use. |

| Mitometh | Mitometh | Mitochondrial Metabolism Modulator | High Purity | Mitometh is a potent mitochondrial metabolism research compound. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

Workflow for PMI-Driven Process Development

The following workflow illustrates a systematic approach for implementing PMI assessment throughout pharmaceutical development:

Process Mass Intensity has evolved from a simple efficiency metric to a comprehensive framework for driving sustainable pharmaceutical manufacturing. The standardized calculation methodologies, implementation protocols, and systematic workflow presented in this application note provide researchers and development scientists with practical tools for PMI assessment and reduction. As the industry continues to advance green chemistry principles, PMI and its expanded derivatives will remain essential metrics for quantifying environmental performance and guiding the development of more sustainable pharmaceutical processes.

In the pursuit of sustainable pharmaceutical manufacturing, green chemistry metrics provide essential quantitative frameworks for evaluating process efficiency and environmental impact. Among these metrics, Process Mass Intensity (PMI) has emerged as a cornerstone for benchmarking and driving improvements within the pharmaceutical industry. PMI represents the total mass of materials used to produce a unit mass of a desired product, accounting for all reactants, reagents, solvents, and catalysts employed throughout the synthesis [5]. This comprehensive scope distinguishes it from earlier metrics and aligns directly with both green chemistry principles and corporate sustainability objectives.

The pharmaceutical industry faces particular challenges in environmental stewardship due to complex multi-step syntheses that traditionally generate substantial waste. PMI was developed specifically to address these challenges by providing a holistic view of resource efficiency that captures the cumulative impact of all process inputs [1]. By focusing attention on the main drivers of process inefficiency—particularly solvent usage—PMI has helped direct optimization efforts toward areas with the greatest potential for improvement in both environmental and economic performance [5] [1].

Comparative Analysis of Green Chemistry Metrics

Defining Key Mass-Based Metrics

Various metrics have been developed to quantify the environmental performance of chemical processes, each with distinct calculations, applications, and limitations. The most prevalent mass-based metrics are compared below.

Table 1: Comparison of Primary Green Chemistry Mass Metrics

| Metric | Calculation | Scope | Ideal Value | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Process Mass Intensity (PMI) | Total mass of inputs / Mass of product [6] | All materials used in the process (reactants, solvents, reagents, catalysts) [5] | 1 | Pharmaceutical process development and benchmarking [5] [1] |

| E-Factor | Total mass of waste / Mass of product [7] | Mass of waste generated, excluding recyclable solvents in some calculations [7] | 0 | Fine chemicals and pharmaceutical manufacturing [7] |

| Atom Economy (AE) | (Molecular weight of product / Molecular weights of reactants) × 100% [7] | Theoretical incorporation of reactant atoms into final product [7] | 100% | Reaction design and route selection [7] |

| Reaction Mass Efficiency (RME) | (Mass of product / Total mass of reactants) × 100% [6] | Mass of reactants actually consumed in the reaction [6] | 100% | Early-stage reaction optimization [6] |

| Effective Mass Yield (EMY) | (Mass of product / Mass of non-benign reagents) × 100% [7] | Focuses specifically on hazardous materials [7] | 100% | Evaluation of toxicity and hazard reduction [7] |

PMI's Distinctive Value Proposition

PMI offers several unique advantages that have established it as the metric of choice for pharmaceutical industry benchmarking:

Comprehensive Scope: Unlike E-factor which focuses on waste, or Atom Economy which is primarily theoretical, PMI accounts for all material inputs including solvents, reagents, and catalysts across both reaction and purification stages [5] [6]. This comprehensive view captures the cumulative resource consumption of a process.

Practical Business Alignment: PMI reduction directly correlates with cost savings and operational efficiency, as materials constitute a significant portion of manufacturing expenses, particularly in solvent-intensive pharmaceutical processes [1]. This creates strong alignment between environmental and business objectives.

Standardized Benchmarking: The ACS GCI Pharmaceutical Roundtable has established PMI as a standardized benchmarking tool across the industry, enabling meaningful comparisons and tracking of performance improvements over time [5] [1].

Process Development Guidance: PMI provides a holistic perspective that guides process chemists and engineers toward more sustainable decisions throughout development, from route selection to optimization [8].

The relationship between PMI and E-factor is mathematically defined as E-Factor = PMI - 1 [6], highlighting their fundamental connection while emphasizing PMI's more direct focus on total resource consumption rather than just waste output.

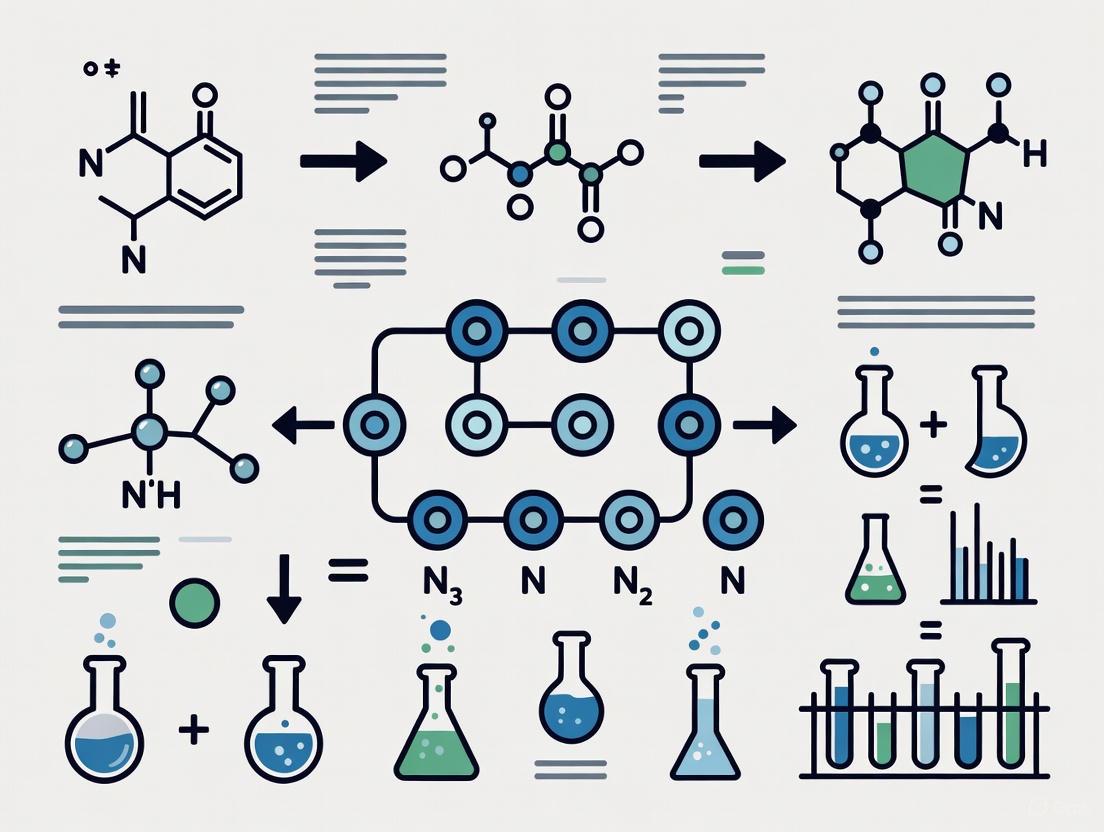

Figure 1: PMI Calculation Framework - PMI provides a comprehensive assessment by accounting for all material inputs relative to the final API output [5] [6].

PMI Implementation Protocols for Pharmaceutical Research

Standardized PMI Calculation Methodology

The ACS GCI Pharmaceutical Roundtable has established standardized protocols for PMI calculation to ensure consistency and comparability across the industry. The fundamental calculation is defined as:

PMI = Total mass of all input materials / Mass of final API [6]

The implementation follows this detailed methodology:

Step 1: Material Inventory Compilation - Document all materials introduced into the process, including: Reaction substrates, Reagents and catalysts, Solvents (for reaction, workup, and purification), and Process aids (filter aids, drying agents) [5].

Step 2: Mass Quantification - Record masses of all inputs using actual experimental data from laboratory notebooks or manufacturing batch records. For multi-step syntheses, track inputs at each discrete step [1].

Step 3: API Mass Determination - Use the actual isolated mass of the final Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) with documented purity. Do not use theoretical yields [1].

Step 4: PMI Calculation - Sum all input masses and divide by the API mass. For processes with solvent recycling, industry practice typically includes both virgin and recycled materials in the calculation to reflect total resource consumption [6].

Step 5: Data Normalization - For multi-step syntheses, apply the convergent PMI calculation when parallel synthesis streams merge, properly weighting inputs from each branch [1].

Advanced Implementation: Convergent Synthesis Calculations

For complex pharmaceutical syntheses with convergent pathways, the ACS GCI PR has developed a specialized Convergent PMI Calculator that accommodates multiple synthetic branches [1]. The protocol for these scenarios requires:

- Independent PMI Calculation for each synthetic branch leading to key intermediates

- Mass-Weighted Averaging of branch PMIs at convergence points

- Cumulative Tracking of all inputs through the final API isolation

This approach ensures that convergent routes are properly evaluated, as they often demonstrate significantly better PMI profiles compared to linear syntheses due to superior mass accumulation efficiency [1].

Experimental Workflow for PMI Assessment

Figure 2: PMI Assessment Workflow - Systematic approach for evaluating and optimizing processes using PMI [5] [1].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Solutions for PMI Implementation

Table 2: Key Research Tools and Solutions for Effective PMI Implementation

| Tool/Solution | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| ACS GCI PMI Calculator [1] | Standardized PMI calculation for linear and convergent syntheses | Process development laboratories; academic research |

| Convergent PMI Calculator [5] [1] | Handles multi-branch synthetic routes with mass-weighted averaging | Complex molecule synthesis; natural product synthesis |

| PMI Prediction Calculator [5] | Estimates PMI ranges prior to laboratory evaluation | Route scouting; early development decision-making |

| Biopharma PMI Calculator [9] | Specialized metric for biologics manufacturing accounting for water, raw materials, and consumables | Biologics process development; monoclonal antibody production |

| iGAL 2.0 Metric [5] [8] | Evaluates PMI and Complete E-factor relative to industry benchmarks using Relative Process Greenness (RPG) index | Sustainability assessment; regulatory documentation |

| Iclaprim-d6 | Iclaprim-d6|Deuterated DHFR Inhibitor | Iclaprim-d6 is a deuterium-labeled internal standard for accurate quantification of the antibiotic Iclaprim in research samples. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

| 6-Bromohexan-2-one | 6-Bromohexan-2-one|CAS 10226-29-6|Supplier | 6-Bromohexan-2-one is a versatile reagent for organic synthesis. This product is for research use only and is not intended for personal use. |

Case Applications and Protocol Integration

PMI in API Process Development

The implementation of PMI tracking has driven significant improvements in active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) manufacturing efficiency. A representative case study involves the development of a commercial-scale process for Gefapixant citrate, where a flow-batch formylation-cyclization process achieved substantial PMI reduction compared to the batch-based approach [8]. The optimization protocol followed this systematic approach:

- Baseline Establishment: The initial batch process PMI was calculated including all material inputs across multiple steps.

- Solvent System Analysis: Identified solvent consumption as the major contributor to PMI.

- Process Intensification: Implemented continuous flow technology for key transformation steps.

- Result: Achieved significant reduction in total PMI and minimized CO generation through optimized process design [8].

The experimental data demonstrated that targeted process modifications informed by PMI analysis could simultaneously improve environmental performance and economic viability, highlighting the metric's value in guiding development priorities.

Protocol for PMI-Driven Process Optimization

For researchers implementing PMI analysis to drive process improvements, the following detailed protocol is recommended:

Phase 1: Baseline Assessment

- Execute the synthetic route at laboratory scale with comprehensive mass tracking

- Calculate overall PMI and step-level PMI contributions

- Identify "hot spots" where material intensity is highest (typically solvent use and workup procedures)

Phase 2: Improvement Opportunities

- Solvent Selection and Recovery: Evaluate alternative solvent systems with improved EHS profiles and recovery potential

- Catalyst Optimization: Assess catalyst loading and recycling opportunities

- Route Modification: Consider alternative synthetic pathways with improved atom economy and reduced protection/deprotection steps

Phase 3: Implementation and Re-evaluation

- Implement highest-impact changes based on technical feasibility and PMI reduction potential

- Recalculate PMI for the optimized process

- Compare against industry benchmarks for similar transformations

This protocol creates a systematic framework for continuous improvement guided by PMI metrics, enabling researchers to make data-driven decisions throughout process development.

Process Mass Intensity has established itself as an essential metric within the pharmaceutical industry's green chemistry toolbox, providing a comprehensive and practical measure of process efficiency. Its unique value stems from the holistic perspective that captures all material inputs rather than focusing exclusively on waste output or theoretical efficiency. This comprehensive view enables PMI to serve as both a benchmarking tool for industry-wide performance assessment and a guidance system for process chemists and engineers seeking to develop more sustainable manufacturing processes.

The continued evolution of PMI methodologies, including specialized calculators for convergent syntheses and biopharmaceutical applications, demonstrates the metric's adaptability to the increasingly complex challenges of modern pharmaceutical development [1] [9]. Furthermore, the integration of PMI with complementary assessment frameworks like iGAL 2.0 creates a multi-dimensional perspective on process sustainability that balances mass efficiency with other critical environmental factors [5] [8].

For researchers and drug development professionals, mastery of PMI principles and implementation protocols represents an essential competency in the pursuit of sustainable pharmaceutical manufacturing. By providing a clear, quantifiable measure of resource efficiency that aligns environmental and business objectives, PMI enables the systematic optimization of synthetic processes to reduce their environmental footprint while maintaining the rigorous quality standards required for pharmaceutical production.

In the pharmaceutical industry, the accurate assessment of environmental impacts is not merely an academic exercise but a fundamental requirement for sustainable development. The definition of system boundaries—the conceptual line that determines which processes are included in an environmental assessment—directly controls the outcome and interpretation of sustainability metrics. For pharmaceutical researchers and process chemists, selecting between gate-to-gate and cradle-to-gate boundaries represents a critical methodological decision that can dramatically alter perceived environmental performance [10] [11]. This distinction is particularly crucial when evaluating Process Mass Intensity (PMI), a key green chemistry metric defined as the total mass of materials input per mass of product obtained [12].

The pharmaceutical sector faces increasing pressure from regulators, payers, and patients to demonstrate environmental responsibility [11]. Within this context, Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) has emerged as the standardized methodology for quantifying environmental impacts across a product's entire lifecycle [10] [11]. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) provides frameworks including ISO 14040 and ISO 14044 that establish principles for LCA, though specific applications for pharmaceuticals require additional sector-specific guidance [10] [11]. Recent industry initiatives like PAS 2090:2025 represent significant steps toward harmonized methodologies specifically for pharmaceutical LCAs [11].

Defining System Boundary Frameworks

Core System Boundary Types

System boundaries define which unit processes are included in an LCA or PMI calculation. The pharmaceutical industry primarily utilizes three boundary types, each providing different insights and having distinct applications [10] [11]:

Cradle-to-Gate: This approach encompasses all processes from raw material extraction ("cradle") through manufacturing until the product leaves the factory gate [10] [11]. For pharmaceuticals, this includes API synthesis, purification, and formulation. This boundary is commonly used for environmental product declarations and supply chain analysis [13].

Gate-to-Gate: This narrower boundary focuses exclusively on internal manufacturing processes within a specific facility [11]. It typically includes only the direct inputs and outputs of the production process itself, excluding supply chain impacts [2].

Cradle-to-Grave: The most comprehensive approach, this includes all stages from raw material extraction through product use and final disposal [10] [14]. For pharmaceuticals, this encompasses patient use and medication disposal phases, though data collection for these stages can be challenging [14].

Table 1: Comparison of System Boundary Types in Pharmaceutical Assessment

| Boundary Type | Processes Included | Common Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cradle-to-Gate | Raw material extraction, transportation, manufacturing | Environmental product declarations, supply chain optimization | Excludes use phase and end-of-life impacts |

| Gate-to-Gate | Internal manufacturing processes only | Process optimization, facility-level benchmarking | Neglects significant upstream impacts |

| Cradle-to-Grave | Full lifecycle from extraction to disposal | Comprehensive sustainability claims, eco-labeling | Data-intensive, challenging for pharmaceutical use phase |

The Functional Unit and Reference Flow

Critical to any assessment is the definition of a functional unit, which provides a standardized basis for comparison [10]. In pharmaceutical applications, this might be "per kilogram of API" or "per 1,000 patient doses." The functional unit ensures equivalency when comparing different products or processes. Closely related is the reference flow, which represents the specific processes and outputs required to fulfill the function defined by the functional unit [10]. For example, if the functional unit is 1,000 uses of an isolation gown, the reference flow for reusable gowns would account for the number of gowns needed (accounting for laundering cycles), while single-use gowns would require 1,000 individual gowns [10].

Quantitative Impact of System Boundary Selection

Correlation Between Mass Intensity and Environmental Impacts

Recent research systematically demonstrates how expanding system boundaries strengthens the relationship between mass-based metrics and environmental impacts. A 2025 study analyzed correlations between eight mass intensities with varying boundaries and sixteen LCA environmental impact categories [2]. The findings revealed that expanding from gate-to-gate to cradle-to-gate boundaries strengthened correlations for fifteen of the sixteen environmental impacts [2]. This demonstrates that cradle-to-gate mass intensities more reliably approximate broad environmental impacts than traditional gate-to-gate PMI.

The correlation strength varies significantly based on which product classes are included in the value chain assessment [2]. Each environmental impact category is approximated by a distinct set of key input materials that serve as proxies for processes in the value chain [2]. For example, coal consumption strongly correlates with climate change impacts due to associated COâ‚‚ emissions from combustion, while other materials might better approximate water use or ecotoxicity [2].

Table 2: Mass Intensity Correlation with Environmental Impacts by System Boundary

| System Boundary | Average Correlation with LCA Impact Categories | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gate-to-Gate (PMI) | Weaker correlation | Simple data requirements, direct process control | Excludes upstream impacts, poor environmental proxy |

| Cradle-to-Gate (VCMI) | Stronger correlation for 15/16 impact categories [2] | Captures supply chain impacts, better environmental proxy | More data intensive, requires value chain transparency |

| Cradle-to-Gate (Specific Product Classes) | Varies by impact category [2] | Can target specific environmental concerns | Requires understanding of material-specific impacts |

Pharmaceutical Industry Case Studies

Small Molecule API Development

A cradle-to-gate LCA of a small molecule Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) at GSK revealed that solvent use accounted for up to 75% of energy consumption and 50% of greenhouse gas emissions [11]. This finding emerged only through a cradle-to-gate analysis that captured upstream impacts of solvent production. The study prompted development of a modular LCA methodology and chemical tree database covering 125 materials, highlighting the critical importance of solvent recovery over incineration [11].

Biopharmaceutical Production

Janssen's cradle-to-gate LCA of infliximab, a biologically produced API, demonstrated that culture media—particularly those containing animal-derived materials—were the largest environmental impact drivers [11]. The analysis revealed that switching to animal-free media, as implemented for ustekinumab production, could reduce resource consumption by up to 7.5 times [11]. This assessment also highlighted that HVAC systems accounted for 75-80% of electricity use in the bioprocessing facility [11].

Protocols for Applying System Boundaries in Pharmaceutical Research

Protocol 1: Defining Cradle-to-Gate System Boundaries for API PMI Assessment

Objective

To establish standardized methodology for calculating cradle-to-gate Process Mass Intensity (PMI) for Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs), ensuring comprehensive inclusion of upstream material and energy flows.

Materials and Equipment

- Process flow diagram of API synthesis

- Bill of materials including all reagents, solvents, and catalysts

- Life cycle inventory database (e.g., Ecoinvent, USDA LCA Digital Commons)

- PMI calculation tool (e.g., ACS GCIPR PMI calculator [12])

Experimental Procedure

Define Functional Unit: Establish a reference unit for the assessment (e.g., 1 kg of API with specified purity) [10].

Map Process Stages: Identify all stages from raw material extraction through API manufacturing, including:

- Raw material acquisition and preprocessing

- Chemical synthesis of intermediates

- API formation and purification

- Packaging materials for transport [14]

Create Life Cycle Inventory: Quantify all material and energy inputs for each process stage:

- Mass of all raw materials, including water

- Energy consumption (electricity, steam, natural gas)

- Transportation distances and modes for materials

- Account for recycling rates and reagent recovery [10]

Calculate Value-Chain Mass Intensity (VCMI): Apply the formula:

Where "raw materials from cradle" includes all naturally extracted resources [2].

Allocate Impacts: For multi-product processes, use allocation methods (mass, economic, or system expansion) to distribute impacts among co-products [10].

Document and Report: Clearly state all inclusions, exclusions, and assumptions following ISO 14044 requirements [10].

Diagram 1: System boundary definitions for pharmaceutical lifecycle assessment

Protocol 2: PMI Prediction and Bayesian Optimization for Greener API Synthesis

Objective

To implement a combined approach of PMI prediction and Bayesian optimization for selecting and optimizing synthetic routes with minimal environmental impact during API process development.

Materials and Equipment

- PMI Predictor app (ACS GCIPR open-access tool) [15] [12]

- Historical PMI data from similar synthetic routes

- EDBO/EDBO+ experimental design platform [15]

- Standard laboratory equipment for reaction execution and analysis

Experimental Procedure

Phase 1: PMI Prediction

- Define Synthetic Routes: Outline 2-3 proposed synthetic pathways to the target API, including all reaction steps, reagents, solvents, and catalysts.

Input Reaction Parameters: For each synthetic route, enter into the PMI Predictor app:

Generate PMI Estimates: The app calculates predicted PMI values for each route based on a dataset of nearly two thousand multi-kilo reactions from pharmaceutical manufacturers [12].

Route Selection: Compare the predicted PMI values and select the most promising route for experimental optimization.

Phase 2: Bayesian Optimization

- Define Design Space: Identify critical reaction parameters to optimize (e.g., temperature, concentration, stoichiometry, solvent ratio).

Set Objective Function: Establish optimization goals (e.g., maximize yield, minimize PMI, maximize enantioselectivity).

Run Initial Experiments: Execute a small set of strategically chosen experiments (typically 8-12) to map the design space.

Iterative Optimization: Using EDBO+ platform:

- The algorithm suggests the next most informative experiments

- Execute suggested experiments

- Update model with results

- Repeat until optimal conditions are identified [15]

Validate Optimal Conditions: Conduct triplicate runs at predicted optimum to confirm performance.

Diagram 2: PMI prediction and Bayesian optimization workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for Pharmaceutical Green Chemistry Assessment

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application in System Boundary Assessment |

|---|---|---|

| ACS GCIPR Solvent Selection Guide | Interactive tool for selecting sustainable solvents based on multiple environmental and safety parameters [12] | Critical for minimizing upstream impacts in cradle-to-gate assessments |

| PMI Calculator | Open-access tool for calculating Process Mass Intensity from raw material inputs [12] | Enables standardized PMI calculation across different boundary conditions |

| PMI Predictor App | Predictive tool for estimating PMI of proposed synthetic routes before laboratory experimentation [15] [12] | Allows virtual screening of routes for greener-by-design synthesis |

| Biocatalysis Guide | Reference guide for implementing enzyme-based transformations [12] | Supports adoption of biocatalysis, often with lower environmental impacts |

| Ecoinvent Database | Life cycle inventory database containing material and energy flow data [2] | Provides secondary data for upstream processes in cradle-to-gate assessments |

| Reagent Guides | Comprehensive resources for selecting sustainable reagents for common transformations [12] | Informs reagent selection to minimize waste and hazard |

| 6-Hydroxybentazon | 6-Hydroxybentazone | High-Purity Reference Standard | 6-Hydroxybentazone: A key bentazone metabolite. For environmental & plant metabolism research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Tifurac sodium | Tifurac Sodium | Beta-Lactamase Inhibitor | RUO | Tifurac sodium is a beta-lactamase inhibitor for antimicrobial resistance research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

The selection of appropriate system boundaries is not merely a technical formality but a fundamental determinant of environmental assessment outcomes in pharmaceutical research. Expanding from gate-to-gate to cradle-to-gate boundaries significantly improves the reliability of mass-based metrics like PMI as proxies for broader environmental impacts [2]. The pharmaceutical industry's increasing adoption of standardized methodologies, including the newly developed PAS 2090:2025 [11], reflects growing recognition that comprehensive environmental accounting requires consideration of the entire value chain.

Emerging tools that combine PMI prediction with Bayesian optimization represent a powerful approach to greener-by-design pharmaceutical synthesis [15]. By enabling researchers to virtually screen synthetic routes for environmental performance before laboratory experimentation, these methods embed sustainability considerations at the earliest stages of process development. As the pharmaceutical industry continues its transition toward a defossilized, circular economy, the critical importance of properly defined system boundaries will only increase, ensuring that reported green advances genuinely reflect reduced environmental impacts [2].

Process Mass Intensity (PMI) has emerged as a critical green chemistry metric for evaluating the sustainability and efficiency of pharmaceutical manufacturing processes. Defined as the total mass of materials used to produce a unit mass of the final active pharmaceutical ingredient (API), PMI provides a comprehensive measure of resource efficiency that directly impacts both environmental footprint and production economics [16]. The pharmaceutical industry faces increasing pressure to reduce its environmental impact, with recent analyses revealing the sector's carbon emissions are equivalent to 514 coal-fired power plants annually [17]. Within this context, PMI has been adopted by the American Chemical Society Green Chemistry Institute Pharmaceutical Roundtable as a key performance indicator to benchmark and drive improvements in green chemistry and engineering [1].

The fundamental relationship between PMI and environmental impact is straightforward: a lower PMI signifies less waste generation, reduced raw material consumption, and decreased energy requirements per unit of API produced [16]. This direct correlation translates to significant business advantages, including lower material procurement costs, reduced waste disposal expenses, and diminished environmental compliance burdens. As the industry strives to meet ambitious sustainability targets—such as AstraZeneca's goal to have 90% of total syntheses meet resource efficiency targets at launch by 2025 [18]—PMI reduction has become an essential strategy for balancing economic and environmental objectives in drug development and manufacturing.

Quantitative Analysis of PMI in Pharmaceutical Processes

Current PMI Benchmarks and Environmental Impact

Comprehensive analysis of pharmaceutical manufacturing reveals significant variations in PMI across different production processes and product types. The following table summarizes key PMI data and corresponding environmental implications for various pharmaceutical manufacturing contexts:

Table 1: PMI Benchmarks and Environmental Impact Across Pharmaceutical Processes

| Process Type | Typical PMI Range | Environmental Impact | Cost Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Small Molecule API | 50 - 200 | Moderate waste generation; solvent-intensive | Material costs: 40-60% of COGS |

| Peptide Synthesis (e.g., GLP-1) | 15,000 - 20,000 | Extremely high waste; hazardous reagents | Significantly higher production costs |

| Biologics Manufacturing | 100 - 500 | Water and energy-intensive | High purification and processing costs |

| Ideal Green Chemistry Target | < 25 | Minimal waste; optimized resource use | Lowest total cost of ownership |

Recent studies highlight the extreme PMI values associated with emerging therapeutic modalities, particularly peptide-based pharmaceuticals. Solid-phase peptide synthesis demonstrates an average PMI of approximately 13,000, with typical GLP-1 agonists reaching 15,000-20,000 [17]. This means producing one kilogram of a peptide API requires 15 to 20 tons of reagents, making peptide synthesis approximately 40-80 times more resource-intensive than traditional small-molecule manufacturing [17]. The environmental burden of such inefficient processes is substantial, contributing disproportionately to the pharmaceutical industry's overall carbon footprint and waste generation.

The relationship between PMI and greenhouse gas emissions is increasingly quantifiable. Research indicates that expanding PMI system boundaries from gate-to-gate to cradle-to-gate strengthens correlations with environmental impact assessments across fifteen of sixteen environmental impact categories [2]. This finding underscores the importance of considering the entire value chain when evaluating the true environmental footprint of pharmaceutical manufacturing processes.

Business Case: Economic Impact of PMI Reduction

The economic rationale for PMI reduction extends beyond simple material cost savings. Lower PMI directly correlates with reduced overall manufacturing costs through multiple mechanisms:

Table 2: Economic Benefits of PMI Reduction Initiatives

| Initiative Category | Typical Cost Reduction | Implementation Timeline | Key Drivers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solvent Optimization | 15-25% of material costs | 6-18 months | Replacement, recovery, and recycling |

| Catalyst Efficiency | 20-40% of catalyst costs | 12-24 months | Recyclable catalysts; heterogeneous systems |

| Process Intensification | 20-35% of operating costs | 18-36 months | Continuous manufacturing; route redesign |

| Waste Management | 10-30% of disposal costs | 6-12 months | Reduction at source; treatment optimization |

Companies that systematically address PMI reduction report significant financial benefits. Pharmaceutical manufacturers have achieved 15-25% cost reductions through comprehensive sustainability initiatives that prioritize PMI improvement [19]. These savings materialize through decreased raw material consumption, lower waste disposal expenses, reduced energy requirements, and diminished environmental compliance burdens. Furthermore, companies with superior PMI performance often benefit from enhanced brand reputation and improved investor confidence, as sustainability metrics increasingly influence investment decisions [17].

A critical business consideration emerges from the tension between rapid growth in certain therapeutic areas and sustainability objectives. As noted by Novo Nordisk CEO Lars Fruergaard Jørgensen, "This will be a significant challenge with emissions continuing to rise as our business expands to keep pace with demand, but we are determined to step up to the task" [17]. This statement highlights the essential challenge facing the industry: decoupling environmental impact from business growth through deliberate PMI optimization strategies.

Experimental Protocols for PMI Assessment and Reduction

Protocol 1: PMI Calculation and Benchmarking

Objective: To standardize the calculation of Process Mass Intensity for pharmaceutical processes enabling accurate benchmarking and performance tracking.

Materials and Equipment:

- Process flow diagram with identified mass balances

- Analytical balances (precision ±0.1 mg)

- Process mass data collection sheets

- ACS GCI PMI Calculator or equivalent computational tool [1]

Procedure:

- Define System Boundaries: Establish clear gate-to-gate boundaries for analysis, including all input materials and output products. For comprehensive assessment, expand to cradle-to-gate boundaries to include upstream value chain impacts [2].

- Document Mass Balances: For each process step, record the masses of all input materials including reactants, solvents, catalysts, and processing aids. Simultaneously document the masses of all output materials including products, by-products, and wastes.

- Calculate PMI: Apply the standard PMI formula: PMI = Total Mass of Input Materials (kg) / Mass of Product (kg). Utilize the ACS GCI PMI Calculator for complex or convergent syntheses [1].

- Benchmark Performance: Compare calculated PMI values against industry benchmarks for similar processes (refer to Table 1 for reference values).

- Identify Improvement Opportunities: Pinpoint process steps contributing disproportionately to high PMI values for targeted optimization.

Validation:

- Verify mass balance closures within ±5% for each process step

- Cross-validate calculations using convergent PMI calculator for complex syntheses

- Conduct sensitivity analysis to identify critical parameters affecting PMI accuracy

Protocol 2: Solvent System Optimization for PMI Reduction

Objective: To reduce PMI through systematic evaluation and implementation of alternative solvent systems.

Materials and Equipment:

- Candidate green solvents (water, bio-based alternatives, etc.)

- Solvent recovery apparatus (distillation, membrane separation)

- Analytical instrumentation for purity assessment (HPLC, GC-MS)

- Environmental, health, and safety (EHS) assessment tools

Procedure:

- Baseline Assessment: Document current solvent consumption patterns and associated PMI contributions using Protocol 1.

- Alternative Evaluation: Identify and screen potential solvent replacements based on environmental, health, and safety criteria alongside technical performance.

- Process Integration: Evaluate identified alternatives in laboratory-scale reactions matching production conditions. Assess reaction efficiency, selectivity, and product quality.

- Recovery and Reuse: Develop solvent recovery protocols establishing closed-loop recycling systems. Determine optimal recovery efficiency targets.

- Lifecycle Assessment: Conduct cradle-to-gate assessment of proposed solvent systems to validate environmental benefits beyond simple mass reduction [2].

Validation:

- Confirm maintained or improved reaction yields and selectivity with alternative solvents

- Verify product quality meets specifications through comprehensive analytical testing

- Demonstrate solvent recovery rates exceeding 80% in closed-loop systems

- Document EHS profile improvements through quantitative metrics

Protocol 3: Catalyst Efficiency Improvement

Objective: To enhance catalyst performance and reusability thereby reducing PMI contributions from catalytic systems.

Materials and Equipment:

- Heterogeneous catalyst candidates

- Catalyst recycling test apparatus

- Kinetic analysis instrumentation

- Metal leaching analysis capability (ICP-MS)

Procedure:

- Catalyst Performance Baseline: Establish baseline activity, selectivity, and lifetime for existing catalytic systems.

- Alternative Catalyst Screening: Evaluate heterogeneous, immobilized, or biodegradable catalyst alternatives focusing on stability and separability.

- Recycling Optimization: Develop protocols for catalyst recovery and regeneration maximizing reuse cycles without significant activity loss.

- Kinetic Modeling: Characterize reaction kinetics to optimize catalyst loading while maintaining desired reaction rates.

- Leaching Analysis: Quantify metal leaching to minimize product contamination and catalyst replenishment requirements.

Validation:

- Demonstrate maintained conversion and selectivity through minimum of five reuse cycles

- Establish catalyst leaching below 1% per cycle for heterogeneous systems

- Verify no detrimental impact on downstream processing or product quality

- Document PMI reduction through decreased catalyst makeup requirements

Visualization of PMI Reduction Strategies

Figure 1: PMI Reduction Strategy Framework illustrating the connection between specific actions and resulting business and environmental outcomes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for PMI Reduction Research

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in PMI Reduction | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Green Solvents | Water, Cyrene, 2-MeTHF, bio-based alcohols | Replace hazardous solvents reducing EHS impact and enabling easier recycling | Miscibility with existing systems, recovery efficiency, azeotrope formation |

| Heterogeneous Catalysts | Immobilized enzymes, polymer-supported reagents, metal-on-carbon | Enable catalyst recovery and reuse minimizing metal leaching and waste | Leaching thresholds, reactivity maintenance, separation efficiency |

| Biocatalysts | Engineered enzymes, whole-cell systems | Provide high specificity reducing purification burden and side products | Cofactor regeneration, operational stability, substrate scope |

| Process Analytical Technology | In-line IR, Raman probes, FBRM sensors | Enable real-time monitoring and control minimizing reprocessing and rejects | Calibration models, probe placement, data integration |

| Alternative Energy Sources | Microwave reactors, flow chemistry systems | Enhance energy efficiency and reaction acceleration reducing processing time | Scalability, equipment compatibility, operational safety |

| 3-Propylmorpholine | 3-Propylmorpholine | High-Purity Reagent for Synthesis | High-purity 3-Propylmorpholine for research. A versatile building block in organic synthesis & pharmaceutical development. For Research Use Only (RUO). | Bench Chemicals |

| Tpt-ttf | Tpt-ttf | Organic Semiconductor | RUO | Tpt-ttf is a key organic semiconductor for materials science research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

The strategic implementation of these reagent solutions requires careful consideration of both technical performance and system-level impacts. For instance, while bio-based solvents typically demonstrate superior environmental profiles, their implementation must account for potential impacts on reaction kinetics, purification requirements, and overall process mass balances [16]. Similarly, heterogeneous catalysts offer clear advantages in separability and reuse, but require validation of long-term stability and consistent performance across multiple reaction cycles [16].

Emerging tools such as the ACS GCI Pharmaceutical Roundtable's PMI Calculator enable researchers to quantitatively assess the impact of reagent substitutions and process modifications before implementation at scale [1]. These computational tools, combined with systematic experimental protocols, provide a robust framework for driving continuous PMI improvement throughout the pharmaceutical development lifecycle.

The strategic reduction of Process Mass Intensity represents a powerful convergence of business and environmental objectives in pharmaceutical manufacturing. As the industry confronts the dual challenges of escalating development costs and increasing sustainability expectations, PMI optimization offers a measurable pathway to enhanced competitiveness and reduced ecological impact. The methodologies and frameworks presented in this application note provide researchers and development scientists with practical tools to systematically address PMI reduction while maintaining the rigorous quality standards essential to pharmaceutical manufacturing. By embedding these principles into early development decision-making and continuously applying them throughout the product lifecycle, organizations can simultaneously advance their economic performance and environmental stewardship, creating a more sustainable future for pharmaceutical innovation.

In the pursuit of targeting more challenging biological pathways and achieving greater selectivity, modern drug discovery is increasingly focusing on complex molecules, including large macrocycles, bifunctional degraders, and novel modalities. While these molecules offer significant therapeutic potential, their complex structures often necessitate lengthy synthetic routes with low overall yields. This evolution has a direct and substantial impact on Process Mass Intensity (PMI), a key metric for evaluating the environmental footprint and efficiency of pharmaceutical manufacturing. A high PMI indicates a less efficient and more environmentally burdensful process. This application note explores the quantifiable relationship between molecular complexity and PMI and provides detailed protocols for the early analytical assessment of complexity to guide more sustainable process development.

Quantifying Molecular Complexity and its Link to PMI

Molecular complexity, while an intuitive concept, requires robust metrics for objective quantification in pharmaceutical research. The relationship between these complexity metrics and the synthetic process efficiency, as captured by PMI, is critical for project planning.

Table 1: Established Metrics for Quantifying Molecular Complexity in Drug Discovery

| Metric | Description | Typical Range (Simple → Complex) | Correlation with Synthetic Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Weight (MW) | Total mass of the molecule. | <500 Da → >500 Da | Generally positive; heavier molecules often require more synthetic steps [20]. |

| Fraction of sp3 Carbons (Fsp3) | Ratio of sp3 hybridized carbon atoms to total carbon count. | <0.3 → >0.5 | Higher Fsp3 is associated with increased three-dimensionality and often greater synthetic difficulty [20]. |

| Number of Chiral Centers | Count of stereogenic centers in the molecule. | 0 → >4 | A strong positive correlation; each center adds potential for stereoselective synthesis and purification challenges [20]. |

| Synthetic Complexity Score | Heuristic algorithms estimating the number of steps and difficulty of synthesis. | Low → High | Directly correlated; higher scores predict longer routes and higher PMI [20]. |

| Molecular Assembly Index (MA) | A newer metric quantifying the number of unique steps required to construct the molecule from building blocks [21]. | Low → High | Positively correlated with the number of synthetic transformations and material inputs [21]. |

While direct, large-scale studies linking these metrics directly to final PMI values are still emerging, the underlying principles are well-established. Complex molecules, as defined by the metrics in Table 1, inherently require more synthetic steps. Each step introduces material inputs (reagents, solvents, catalysts) and generates waste, directly contributing to a higher overall PMI for the final Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API). Research indicates that less complex molecules are more common starting points for drug discovery, partly due to the ease of synthesis and optimization [22]. The trend toward more complex structures therefore presents a significant challenge to the industry's green chemistry goals.

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Molecular Complexity

Early analytical characterization is vital for quantifying molecular complexity and anticipating process development challenges. The following protocols utilize spectroscopic techniques to determine key complexity metrics.

Protocol: Determining Complexity Metrics via NMR and LC-MS

This protocol outlines the standard procedure for characterizing a new chemical entity to derive fundamental complexity metrics.

1. Purpose: To determine key molecular descriptors (Molecular Weight, Fsp3, chiral center count) and estimate synthetic complexity for a target compound.

2. Experimental Workflow:

3. Materials:

- Target Compound: >95% purity by HPLC.

- Deuterated Solvents: (e.g., DMSO-d6, CDCl3).

- LC-MS System: Equipped with Electrospray Ionization (ESI) and Time-of-Flight (TOF) mass analyzer.

- NMR Spectrometer: 400 MHz or higher.

4. Procedure: 1. Sample Preparation: - Accurately weigh 1-2 mg of the target compound. - Dissolve in 0.6 mL of an appropriate deuterated solvent for NMR analysis. - For LC-MS, prepare a separate solution in a compatible solvent (e.g., MeCN/H2O) at ~0.1 mg/mL. 2. LC-MS Analysis: - Inject the sample onto the LC-MS system. - Use the high-resolution mass data to confirm the exact molecular weight and formula. 3. NMR Analysis: - Acquire standard 1H and 13C NMR spectra. - Analyze the 1H NMR spectrum for complexity (e.g., signal dispersion, number of distinct proton environments). - Use the 13C NMR spectrum to count the number of unique carbon environments and classify them (sp3 vs. sp2) to calculate Fsp3. - Identify and count signals corresponding to chiral centers where possible. 4. Data Integration: - Compile data from LC-MS and NMR. - Calculate Fsp3 = (Number of sp3 hybridized carbons) / (Total carbon count). - Combine metrics to generate a synthetic complexity score based on internal heuristic models.

Protocol: Experimental Measurement of Molecular Assembly Index via Spectroscopy

Assembly Theory provides a framework for quantifying molecular complexity that can be experimentally measured using spectroscopy, moving beyond algorithmic predictions [21].

1. Purpose: To experimentally determine the Molecular Assembly (MA) number of a target molecule using spectroscopic data as a proxy for complexity.

2. Experimental Workflow:

3. Materials:

- Target Compound: >95% purity.

- FTIR Spectrometer.

- Tandem Mass Spectrometer (MS/MS): Q-TOF or similar.

- NMR Spectrometer.

4. Procedure: 1. Infrared (IR) Spectroscopy: - Obtain a clean IR spectrum of the compound. - Measurement: Count the number of independent absorbances in the IR spectrum. This number serves as one estimate for the MA. 2. Tandem Mass Spectrometry (MS/MS): - Analyze the compound using MS/MS with collision-induced dissociation (CID). - Measurement: Count the number of independent, unique fragments generated from the precursor ion. This count provides a second, independent estimate for the MA. 3. 13C NMR Spectroscopy: - Acquire a quantitative 13C NMR spectrum. - Measurement: Count the number of unique carbon resonances. This provides a third estimate for the MA. 4. Data Analysis and MA Index Calculation: - The final MA index is determined based on the consistent measurements from the independent spectroscopic techniques. A higher number of unique features (absorbances, fragments, resonances) indicates a more complex molecule with a higher MA index [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Complexity and PMI Studies

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Deuterated NMR Solvents (e.g., DMSO-d6, CDCl3) | Essential for preparing samples for NMR spectroscopy to determine structure, purity, and parameters like Fsp3. |

| LC-MS Grade Solvents | High-purity solvents for mass spectrometry to prevent contamination and ensure accurate molecular weight and fragmentation data. |

| Chiral Derivatization Reagents | Used to facilitate the determination of enantiomeric purity and the absolute configuration of chiral centers via NMR or LC-MS. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Building Blocks (e.g., 13C, 15N) | Used in mechanistic studies and for tracing the fate of atoms in a synthetic route, aiding in route optimization for lower PMI. |

| Advanced Fragmentation Libraries & Software | Computational tools for predicting and interpreting MS/MS fragmentation patterns to support structural elucidation and complexity assessment. |

| Quantacure qtx | Quantacure QTX | UV-Curing Photoinitiator | For Research |

| Barminomycin I | Barminomycin I | Anthracycline Research Compound |

The increasing molecular complexity of drug candidates presents a clear and multi-faceted challenge to achieving optimal Process Mass Intensity. By integrating advanced analytical techniques—from standard NMR to the novel application of Assembly Theory via spectroscopy—scientists can quantify complexity early in the development lifecycle. This proactive assessment enables informed decision-making, guiding the selection of synthetic routes and encouraging innovation in process chemistry to mitigate the environmental impact, ultimately contributing to a more sustainable pharmaceutical industry.

How to Calculate, Apply, and Reduce PMI in API Development and Manufacturing

A Step-by-Step Guide to Calculating PMI for Synthetic Routes

Process Mass Intensity (PMI) is a key metric used to benchmark the sustainability, or "greenness," of a chemical process, particularly in the pharmaceutical industry. It focuses on the total mass of materials used to produce a given mass of a product, providing a direct measure of process efficiency and environmental impact [5]. PMI accounts for all materials used within a pharmaceutical process, including reactants, reagents, solvents (used in both reaction and purification steps), and catalysts [5]. By offering a holistic view of material consumption, PMI has become an instrumental tool for driving improvements in process inefficiency, cost, environmental impact, and health and safety, thereby fostering the development of more sustainable and cost-effective manufacturing processes [5] [1].

The American Chemical Society Green Chemistry Institute Pharmaceutical Roundtable (ACS GCI PR) has been a primary driver in championing PMI as a standard metric. The first PMI benchmarking exercise was held in 2008, and such benchmarking has been conducted regularly since, helping the industry focus on the main drivers of process inefficiency [1]. The industry's commitment to this metric has now progressed beyond simple calculation to encompass more advanced concepts like Manufacturing Mass Intensity (MMI), which expands the scope to account for other raw materials required for active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) manufacturing [4].

PMI Calculation Methodology

The Fundamental PMI Equation

At its core, PMI is calculated by dividing the total mass of all materials entering a process by the mass of the final product produced. The result is a dimensionless number that indicates how much input mass is required to produce one unit of output mass.

PMI = Total Mass of All Inputs (kg) / Mass of Product (kg)

A PMI of 1 is theoretically perfect, indicating no waste, but this is rarely achievable. In practice, a lower PMI value signifies a more efficient and greener process. The "Total Mass of All Inputs" is comprehensive and includes [5]:

- Reactants: Starting materials and reagents.

- Reagents: Substances that facilitate the reaction.

- Solvents: Used in reaction, work-up, and purification.

- Catalysts.

- Water.

A Step-by-Step Calculation Protocol

The following protocol provides a detailed methodology for calculating the PMI of a synthetic route, whether for a single step or an entire multi-step sequence.

Protocol: Calculating Process Mass Intensity

Objective: To determine the PMI for a given chemical synthesis, enabling quantitative assessment and benchmarking of process efficiency.

Materials and Tools:

- Laboratory or pilot plant data (batch records, lab notebooks).

- Mass balance for the reaction step or overall sequence.

- The ACS GCI PR PMI Calculator (or similar tool) is recommended for standardized calculation [1].

Procedure:

Define the System Boundary:

- Clearly state whether the calculation is for a single reaction step or the entire synthetic route to the final product (e.g., the API).

- For multi-step linear sequences, the output of one step is typically considered a reactant for the next.

Identify and Sum All Input Masses:

- For the defined system, record the masses (preferably in kg) of every material introduced. This must include all of the following categories [5]:

- Reactants and Reagents

- Solvents (for reaction, extraction, crystallization, and chromatography)

- Catalysts and Ligands

- Water used in any part of the process

- Sum these masses to obtain the Total Mass Input.

- For the defined system, record the masses (preferably in kg) of every material introduced. This must include all of the following categories [5]:

Record the Mass of the Isolated Product:

- Determine the mass of the target product after isolation, purification, and drying. This is the Mass of Product.

- Note: Use the mass of the final, pure product. For multi-step calculations, this is the mass of the API or final intermediate at the end of the sequence.

Apply the PMI Formula:

- Divide the Total Mass Input by the Mass of Product.

- PMI = Total Mass Input / Mass of Product

Interpret the Results:

- A lower PMI indicates a more efficient process with less waste.

- Compare the calculated PMI to industry benchmarks or use it to track improvements during process optimization.

Example Calculation for a Single Step: Consider a simple reaction step with the following inputs and output:

- Reactant A: 1.5 kg

- Reagent B: 0.8 kg

- Solvent: 12.0 kg

- Catalyst: 0.1 kg

- Total Mass Input = 1.5 + 0.8 + 12.0 + 0.1 = 14.4 kg

- Mass of Product C isolated = 1.2 kg

- PMI = 14.4 kg / 1.2 kg = 12 kg/kg

This means 12 kg of materials are used to produce 1 kg of Product C.

Workflow for PMI Calculation

The logical workflow for performing a PMI assessment, from data collection to interpretation, can be visualized as follows. This workflow ensures a consistent and thorough approach.

Advanced PMI Tools and Predictive Models

To support the pharmaceutical industry in implementing PMI, the ACS GCI PR has developed a suite of calculators that move beyond manual calculation.

Suite of PMI Calculators

Table 1: Advanced PMI Calculators for Pharmaceutical Development

| Tool Name | Key Features | Primary Use Case | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| PMI Calculator | Accounts for raw material inputs against API output. | Standardized calculation of PMI for a single synthetic sequence. | [1] |

| Convergent PMI Calculator | Allows multiple branches for single-step or convergent synthesis. | Calculating PMI for more complex, branched synthetic routes. | [1] |

| PMI Prediction Calculator | Uses historical data and Monte Carlo simulations to estimate probable PMI ranges. | Predicting PMI prior to laboratory work to assess and compare potential routes. | [23] |

Predictive Modeling of PMI

Recent research has focused on predicting PMI from molecular structure alone, allowing for early-stage route assessment. Two prominent approaches are:

SMART-PMI (in-Silico MSD Aspirational Research Tool): Developed by Sherer et al. at Merck, this model predicts an "Aspirational" PMI based solely on the molecular weight (MW) and molecular complexity of the target compound [24].

Cumulative Complexity Meta-Metrics (∑CM*): This approach uses a cumulative complexity metric, calculated along the longest linear sequence of a synthetic route, as a surrogate for step count. It has been demonstrated to be a useful predictor of PMI for small molecules (<600 Da) with good accuracy (R² >0.9) and requires no empirical investigation [25] [26].

PMI Calculation for Convergent Syntheses

Many complex molecules, especially APIs, are synthesized via convergent routes where distinct fragments are synthesized in parallel and then combined. Calculating PMI for such routes requires a specific approach, which is facilitated by the ACS GCI PR's Convergent PMI Calculator [1].

The key principle is to calculate the PMI for each branch independently and then account for the mass inputs of the convergent (coupling) step. The overall process is visualized in the workflow below.

Procedure for Convergent Synthesis PMI:

- Treat Each Branch as a Separate Linear Sequence: Calculate the total mass input required to produce the final intermediate for each branch (e.g., Intermediate A and Intermediate B). The mass of each intermediate is its "product mass" for that branch calculation.

- Calculate the Convergent Step: In the final coupling step, the intermediates from each branch are used as inputs, along with any additional reagents, catalysts, and solvents.

- Sum All Masses for the Entire Process:

- Total Input Mass = (All inputs for Branch A) + (All inputs for Branch B) + (All inputs for the Convergent Step)

- Note: The masses of Intermediates A and B are not added here, as their constituent masses are already accounted for in their respective branch inputs.

- Calculate Overall PMI: Divide the Total Input Mass by the mass of the final product isolated after the convergent step and any subsequent purification.

The Scientist's Toolkit for PMI Assessment

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Tools for PMI Analysis

| Tool / Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in PMI Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| PMI Calculation Software | ACS GCI PR PMI Calculator, Convergent PMI Calculator, PMI Prediction Calculator [1] [23] | Standardized tools for accurate and benchmarked PMI determination across simple and complex syntheses. |

| Predictive In-Silico Tools | SMART-PMI Model [24], Cumulative Complexity (∑CM*) Models [26] | Provides early-stage, aspirational PMI targets based on molecular structure to guide route selection and design. |

| Solvents & Reagents | Green solvent alternatives (e.g., Cyrene, 2-MeTHF), Catalysts (e.g., immobilized catalysts) | Reducing the mass and hazard profile of the largest contributors to PMI; key levers for optimization. |

| Mass Balance Tracking | Laboratory Information Management Systems (LIMS), Electronic Lab Notebooks (ELNs) | Critical for accurate data collection of all input masses and isolated yields, forming the foundation of reliable PMI calculation. |

| Sodium hypobromite | Sodium Hypobromite | High-Purity Reagent | RUO | High-purity Sodium Hypobromite for research applications, including oxidation & bromination studies. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| 2-Ethylhex-5-en-1-ol | 2-Ethylhex-5-en-1-ol, CAS:270594-13-3, MF:C8H16O, MW:128.21 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Calculating Process Mass Intensity is a fundamental practice for any researcher or organization committed to sustainable and economical pharmaceutical development. This guide has outlined a clear, step-by-step protocol for performing these calculations, from simple linear sequences to complex convergent syntheses. By leveraging the available calculators and emerging predictive models, scientists can now benchmark their processes and set aspirational efficiency targets even before setting foot in the laboratory. Integrating PMI assessment into the core of process research and development provides a powerful, quantitative framework for driving innovation in green chemistry and reducing the environmental footprint of drug manufacturing.

Leveraging AI and Machine Learning for PMI Prediction in Route Scouting

In the pharmaceutical industry, Process Mass Intensity (PMI) has emerged as a crucial metric for evaluating the environmental sustainability and efficiency of chemical processes. PMI is defined as the total mass of materials input (including solvents, reagents, and process chemicals) required to produce a unit mass of the final Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) [1]. The pharmaceutical industry has utilized PMI for over 15 years to benchmark progress toward more sustainable manufacturing practices [4]. A lower PMI value indicates a more efficient and environmentally favorable process, as it corresponds to reduced resource consumption and waste generation.

The adoption of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) technologies is transforming PMI prediction during early-stage route scouting. These advanced computational approaches enable researchers to evaluate synthetic routes in silico before laboratory experimentation, significantly accelerating process development while reducing resource consumption [27]. Project Management Institute research indicates that while AI adoption is accelerating, only about 20% of project managers in relevant fields report extensive practical experience with AI tools, highlighting both the opportunity and need for specialized applications in pharmaceutical development [28].

Traditional PMI assessment methods rely heavily on experimental data from laboratory-scale experiments, which are time-consuming and resource-intensive. The integration of AI and ML offers a paradigm shift, allowing scientists to predict PMI values for proposed synthetic routes with increasing accuracy, thereby focusing experimental efforts on the most promising candidates [27]. This approach aligns with the pharmaceutical industry's broader transition toward green chemistry principles and sustainable manufacturing practices.

Current State of PMI Prediction

Established PMI Calculation Methods

The foundation of AI-driven PMI prediction builds upon established calculation methodologies. The ACS Green Chemistry Institute (GCI) Pharmaceutical Roundtable has developed standardized tools for PMI calculation, including the basic PMI Calculator and the more advanced Convergent PMI Calculator for complex synthetic routes [1]. These tools enable researchers to quantify process efficiency based on reaction stoichiometry, solvent usage, and auxiliary materials.

Recent research has critically evaluated the relationship between mass-based metrics and environmental impacts. A 2025 study by Eichwald et al. systematically analyzed the correlation between PMI with varying system boundaries and Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) environmental impacts [2]. Their findings indicate that expanding system boundaries from gate-to-gate to cradle-to-gate strengthens correlations for most environmental impacts, supporting the development of more comprehensive Value-Chain Mass Intensity (VCMI) metrics [2].

Limitations of Current Approaches

Despite their widespread adoption, traditional mass intensities face significant limitations. The 2025 analysis revealed that a single mass-based metric cannot fully capture the multi-criteria nature of environmental sustainability, as different environmental impacts are approximated by distinct sets of input materials [2]. Furthermore, the reliability of mass-based environmental assessment is highly time-sensitive, particularly during the transition toward a defossilized chemical industry [2].

Table 1: PMI Benchmarking Data from Industry Sources

| Process Type | Typical PMI Range | Industry Leaders | Key Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early Development | 100-500 | ACS GCI Roundtable Companies | Route complexity, purification needs |

| Optimized Processes | 50-150 | Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb | Catalysis, solvent selection, convergence |

| Biocatalytic Routes | 25-80 | Emerging Applications | Enzyme efficiency, fermentation yields |

| Ideal Target | <50 | ACS GCI Goals | Atom economy, solvent recovery |

The pharmaceutical industry continues to develop more comprehensive metrics, such as Manufacturing Mass Intensity (MMI), which expands upon PMI to account for additional raw materials required for API manufacturing [4]. These evolving metrics provide the foundational data necessary for effective ML model training.

AI and ML Approaches for PMI Prediction

Data Requirements and Preparation

Successful AI/ML implementation for PMI prediction requires robust, standardized datasets. The ACS GCI Pharmaceutical Roundtable has compiled a comprehensive database of approximately 2,000 data points collected from member companies, which serves as a valuable resource for model development [27]. These datasets include information on reaction types, substrates, conditions, and associated PMI values across various development phases.

Data standardization is critical for effective model training. This includes defining consistent data formats for representing chemical reactions, material quantities, and process parameters. Recent policy recommendations emphasize establishing standard protocols for data collection and sharing across the pharmaceutical industry and research institutions to foster robust ML model development [29]. Such standards should encompass data formats, secure repositories, and access protocols to ensure data quality while protecting intellectual property.

Machine Learning Techniques

Various ML techniques show promise for PMI prediction, each with distinct strengths and applications:

- Random Forest Regression: Effective for handling diverse feature types and identifying important predictors of PMI, particularly valuable with smaller datasets.

- Gradient Boosting Methods: Provide high predictive accuracy for PMI values across different reaction types and process conditions.

- Neural Networks: Capable of modeling complex, non-linear relationships between molecular descriptors, reaction parameters, and PMI outcomes, especially with large datasets.

- Explainable AI (XAI) Techniques: Address the "black box" problem by making model predictions interpretable to chemists and engineers, facilitating trust and adoption [30].

The emerging trend of multimodal AI models enables simultaneous processing of diverse data types, including textual reaction procedures, molecular structures, and continuous process parameters, allowing for more holistic PMI predictions [30].

Table 2: Machine Learning Model Performance for PMI Prediction

| Model Type | Prediction Accuracy (R²) | Data Requirements | Interpretability | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple Linear Regression | 0.45-0.65 | Low | High | Initial screening, linear relationships |

| Random Forest | 0.70-0.85 | Medium | Medium | Route scouting with limited data |

| Gradient Boosting | 0.75-0.90 | Medium | Medium | Optimized process selection |

| Neural Networks | 0.80-0.95 | High | Low | Complex route evaluation with large datasets |

| Explainable AI (XAI) | 0.70-0.85 | Medium-High | High | Regulatory applications, decision support |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Predictive PMI Modeling for Route Scouting

Objective: To predict PMI values for proposed synthetic routes using historical process data and machine learning algorithms.

Materials and Reagents:

- Historical PMI dataset (minimum 200 data points recommended)

- Chemical descriptor calculation software (RDKit, Dragon)

- ML programming environment (Python with scikit-learn, TensorFlow/PyTorch)

- Reaction representation system (SMILES, reaction SMARTS)

Methodology:

- Data Collection and Curation: Compile historical PMI data from internal databases and public sources, including reaction types, yields, stoichiometry, solvent masses, and workup procedures.

- Feature Engineering: Calculate molecular descriptors for reactants, reagents, and products; encode reaction conditions as continuous or categorical variables.

- Model Training: Split data into training (70%), validation (15%), and test sets (15%); train multiple ML algorithms using cross-validation.