Optimizing Reaction Kinetics for Greener Chemistry: Strategies for Sustainable Pharmaceutical Development

This article provides a comprehensive framework for integrating reaction kinetics optimization with green chemistry principles to advance sustainable pharmaceutical development.

Optimizing Reaction Kinetics for Greener Chemistry: Strategies for Sustainable Pharmaceutical Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for integrating reaction kinetics optimization with green chemistry principles to advance sustainable pharmaceutical development. It explores the foundational synergy between kinetic analysis and waste prevention, details practical methodologies like Variable Time Normalization Analysis (VTNA) and solvent greenness evaluation, and addresses common troubleshooting scenarios for complex reaction systems. Through validation case studies from antiviral drug synthesis and antiparasitic development, we demonstrate how these approaches yield substantial improvements in process efficiency, environmental impact, and cost savings while maintaining product quality. This resource equips researchers and drug development professionals with actionable strategies to implement greener reaction optimization in their workflows.

The Inseparable Link Between Kinetic Understanding and Green Chemistry Principles

The Critical Role of Reaction Rate in Process Sustainability and Energy Efficiency

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: How does optimizing reaction kinetics directly contribute to greener chemistry? Optimizing reaction kinetics is fundamental to green chemistry as it directly enhances process efficiency and reduces environmental impact. By increasing reaction rates and selectivity, researchers can achieve higher yields in less time, lowering energy consumption and minimizing the generation of chemical waste. This aligns with the first principle of green chemistry: waste prevention [1]. Furthermore, understanding kinetics allows for the replacement of hazardous reagents with safer alternatives and the use of milder reaction conditions, reducing overall process hazard and energy intensity [2] [1].

FAQ 2: What are the practical tools for analyzing reaction kinetics during optimization? Several practical tools are available for kinetic analysis:

- Variable Time Normalization Analysis (VTNA): This is a valuable technique to determine reaction orders without requiring a deep understanding of complex mathematical derivations. It is particularly useful for analyzing reactions with potentially complex rate laws and can be implemented using a spreadsheet [2].

- Linear Solvation Energy Relationships (LSER): This method uses multiple linear regression to correlate solvent polarity parameters with reaction rates. Understanding this relationship helps in selecting solvents that enhance performance while considering greenness and safety [2].

- In-situ Monitoring: Techniques like <1H NMR spectroscopy> can be used to measure reactant and product concentrations at timed intervals, providing the high-quality data necessary for kinetic analysis [2].

FAQ 3: How can I make my reaction more energy-efficient through kinetic control? Energy efficiency can be significantly improved by:

- Lowering Activation Energy: Employ catalysts to provide an alternative reaction pathway with a lower activation energy (Ea). According to the Arrhenius equation, this leads to a faster reaction rate at the same temperature, allowing you to run reactions under milder conditions [3] [4].

- Intensifying Processes: Transitioning from traditional batch reactors to continuous flow systems can dramatically enhance energy efficiency. Flow reactors often provide better heat and mass transfer, reduce reaction times, and enable more facile scalability, as demonstrated in the oxidation of furfural to maleic anhydride [5].

- Exploring Alternative Energy Sources: Utilizing mechanical energy through mechanochemistry (e.g., ball milling) can drive reactions without the need for solvents, thereby eliminating the energy cost associated with heating and evaporating solvents [6].

FAQ 4: What role do solvents play in reaction kinetics and sustainability? The solvent is a critical parameter as it can greatly influence the reaction rate, mechanism, and greenness [2]. Its properties, such as hydrogen bond donating/accepting ability and dipolarity, can stabilize or destabilize the transition state, thereby accelerating or slowing down the reaction [2]. From a sustainability perspective, solvents often account for the majority of the mass in a process. Therefore, choosing safer, biodegradable solvents or, ideally, moving towards solvent-free synthesis (e.g., mechanochemistry or on-water reactions) can drastically reduce the environmental footprint and safety risks [6] [1].

FAQ 5: How is AI and machine learning used in reaction optimization? AI and machine learning (ML) are transforming reaction optimization by moving beyond traditional trial-and-error. ML models can predict reaction outcomes, such as yield and selectivity, by learning complex, non-linear relationships between reaction conditions (e.g., catalyst, solvent, temperature) and outcomes [7]. These models can be coupled with metaheuristic optimization algorithms to efficiently navigate the vast parameter space and identify optimal conditions that maximize performance while aligning with green chemistry principles, such as atom economy and energy efficiency [6] [7].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Product Yield or Slow Reaction Rate

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Sub-optimal Catalyst or Insufficient Loading | Conduct a series of experiments with different catalysts or loadings while monitoring conversion over time. Use VTNA to determine the order with respect to the catalyst. | Screen different homogeneous or heterogeneous catalysts. Consider polymer-immobilized catalysts for easier recovery and recycling [5]. |

| Insufficient Activation Energy | Determine the activation energy (Ea) of the reaction using the Arrhenius equation by measuring the rate constant (k) at different temperatures. | Increase reaction temperature (consider trade-offs with safety and selectivity). Introduce a suitable catalyst to lower the activation energy barrier [3] [4]. |

| Inefficient Mass or Heat Transfer | Evaluate the reaction in different reactor setups (e.g., compare batch vs. continuous flow stirrer). | Switch to a continuous flow reactor for improved mixing and heat transfer. Increase agitation rate in a batch reactor [5]. |

| Inappropriate Solvent | Measure initial reaction rates in solvents with different polarities (e.g., using Kamlet-Abboud-Taft parameters). Construct an LSER to identify which solvent properties accelerate the reaction [2]. | Select a solvent that aligns with the mechanistic requirements of the rate-determining step. Prioritize solvents with a good safety, health, and environment (SHE) profile [2]. |

Problem: Poor Reaction Selectivity and High By-product Formation

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Uncontrolled Reaction Pathway | Identify and quantify major by-products to hypothesize competing pathways. Monitor for intermediate species using in-situ spectroscopy. | Modify the catalyst to favor the desired pathway. Adjust reactant concentrations or add selective inhibitors for the side reaction. Control residence time precisely in a flow reactor [5]. |

| Harsh Reaction Conditions | Perform a time-course analysis to see if the desired product degrades over time or at high temperature. | Lower the reaction temperature and use a catalyst to maintain a reasonable rate. Shorten the reaction time, for instance, by using continuous flow [5]. |

| Solvent-Induced Side Reactions | Check if the solvent is nucleophilic or can participate in the reaction (e.g., as in the hydrolysis of maleic anhydride to maleic acid [5]). | Switch to a non-nucleophilic solvent. For example, replacing acetonitrile with ethyl acetate can prevent unwanted solvent interference [5]. |

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Protocol 1: Kinetic Analysis Using Variable Time Normalization Analysis (VTNA)

This protocol is adapted from green chemistry optimization research [2].

Objective: To determine the order of a reaction with respect to each reactant without prior knowledge of the rate law.

Materials:

- Reactants

- Appropriate solvent

- NMR tubes or other suitable reaction vessels

- <1H NMR spectrometer> or HPLC for quantitative analysis

Methodology:

- Experimental Design: Prepare a series of reactions with varying initial concentrations of the reactants. Keep other conditions (temperature, catalyst loading) constant.

- Reaction Monitoring: For each experiment, quench samples at multiple time points.

- Quantitative Analysis: Use <1H NMR> or HPLC to determine the concentration of the starting material or product at each time point.

- Data Processing: Enter the concentration-vs-time data into a dedicated spreadsheet [2].

- VTNA Application: The spreadsheet will guide you to test different potential reaction orders. The correct orders will be revealed when plots of conversion versus normalized time (time × [reactant]^order) for all experiments overlap onto a single curve [2].

Protocol 2: Investigating Solvent Effects via Linear Solvation Energy Relationships (LSER)

Objective: To understand how solvent properties influence the reaction rate and identify greener solvent alternatives.

Materials:

- A set of 8-10 solvents with diverse polarities (e.g., from the CHEM21 guide [2])

- Standardized reaction setup

Methodology:

- Constant Conditions: Run the same reaction in each of the selected solvents, ensuring that temperature, catalyst, and initial reactant concentrations are identical.

- Rate Constant Determination: For each solvent, monitor the reaction to determine the rate constant (k).

- Data Correlation: Input the natural logarithm of the rate constants (ln k) and the solvatochromic parameters (α, β, π*) for each solvent into the optimization spreadsheet.

- LSER Generation: Use the spreadsheet's multiple linear regression function to generate an equation of the form: ln(k) = C + aα + bβ + cπ*. This LSER reveals which solvent properties (HBD ability, HBA ability, polarizability) accelerate the reaction [2].

- Solvent Selection: Use the derived LSER to predict performance in other solvents and cross-reference with greenness metrics (e.g., CHEM21 scores) to shortlist optimal, sustainable solvents [2].

Table 1: Exemplary Kinetic Data from a Continuous Flow Oxidation of Furfural [5]

| Entry | Solvent | Residence Time (min) | Conversion of Furfural (%) | Yield of Maleic Anhydride (%) | Yield of 5-hydroxy-2(5H)-furanone (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | MeCN | 6.5 | ~100 | 37 | 28 |

| 2 | MeCN | 3.25 | 85 | 26 | 20 |

| 3 | MeCN | 1.63 | 58 | 15 | 12 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 9 | MeCN/Hâ‚‚O (1:1) | 6.5 | ~100 | 0 | 78 |

Table 2: Green Chemistry Metrics for Solvent Selection [2]

| Solvent | Kamlet-Abboud-Taft β (HBA) | Kamlet-Abboud-Taft π* (Polarizability) | Predicted ln(k) | SHE Score (Sum) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF) | 0.69 | 1.00 | -11.5 | 14 |

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | 0.75 | 1.00 | -11.3 | 11 |

| Isopropanol (IPA) | 0.95 | 0.48 | -13.8 | 8 |

| Ethyl Acetate (EtOAc) | 0.45 | 0.55 | -13.5 | 7 |

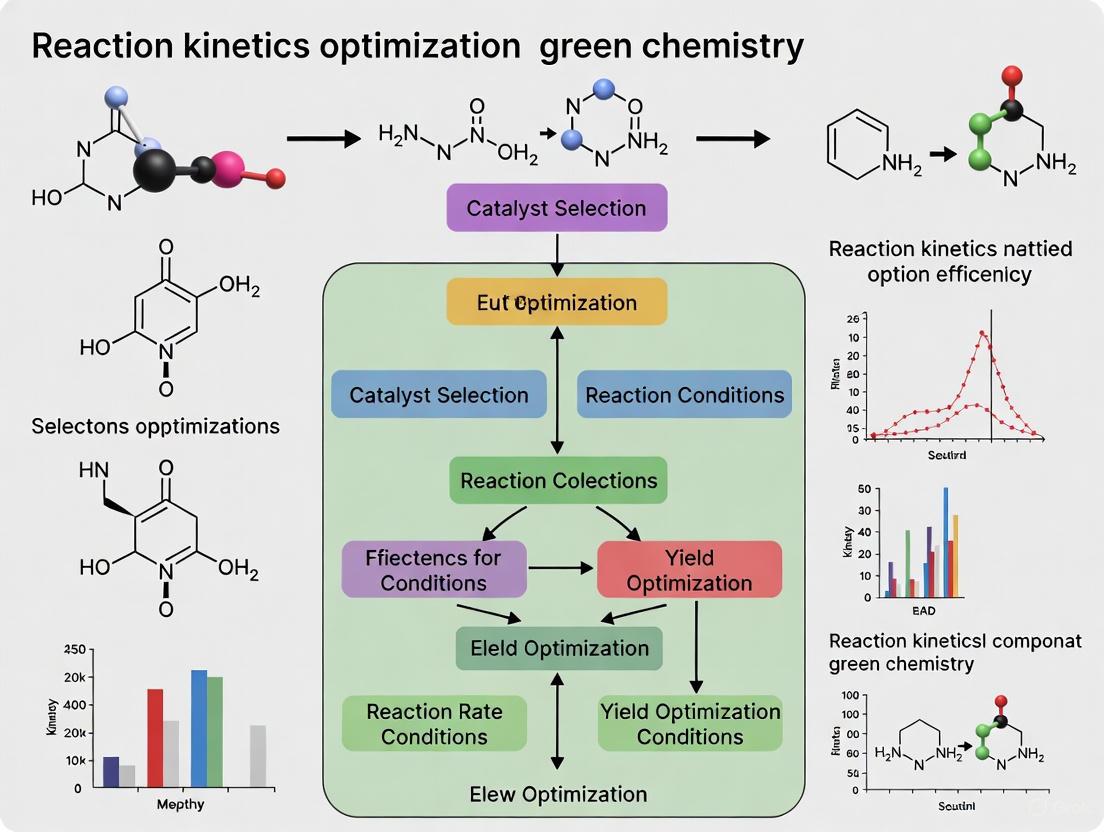

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Reaction optimization workflow using kinetics and LSER.

Diagram 2: Optimization of furfural oxidation via continuous flow [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Kinetic Optimization in Green Chemistry

| Item | Function & Rationale | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Polymer-Immobilized TEMPO (PIPO) | A recyclable, heterogeneous catalyst that facilitates oxidation reactions, simplifying product separation and reducing catalyst waste. | Proposed as a future research direction for easily removed and recycled catalysts in oxidation reactions [5]. |

| Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) | Customizable, biodegradable solvents used as a low-toxicity alternative to conventional solvents for extractions and other processes, supporting circular chemistry. | Used for extracting critical metals from e-waste and bioactive compounds from biomass, aligning with circular economy goals [6]. |

| Methylene Blue | An organic dye used as a photosensitizer to generate singlet oxygen (O21) for photocatalytic oxidation reactions under mild conditions. | Used in a continuous flow reactor to achieve rapid oxidation of furfural via singlet oxygen [5]. |

| Vanadium-based Catalysts | Traditional catalysts for gas-phase oxidation processes (e.g., maleic anhydride production). Research focuses on adapting them for milder, solution-phase reactions with renewable feedstocks. | Used in the traditional petroleum-based process for MA production and explored for solution-phase oxidation of biorenewable furfural [5]. |

| Silver Nanoparticles | Nanoparticles synthesized in water, demonstrating the potential of aqueous systems for catalytic and material synthesis, avoiding toxic organic solvents. | Developed in water using plasma-driven electrochemistry, highlighting the use of water as a green solvent [6]. |

| Tinopal 5BM | Tinopal 5BM | Fluorescent Brightener 28 | Tinopal 5BM is a key fluorescent whitening agent for industrial and biochemical research. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. |

| Tellurium diiodide | Tellurium diiodide, CAS:13451-16-6, MF:I2Te, MW:381.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Troubleshooting FAQs for the Practicing Scientist

Q1: My synthetic route has a high yield, but I am generating a large mass of waste. Which principle and metrics should I focus on?

A1: A high yield does not always equate to an efficient or green process. Your primary focus should be on Principle 1: Waste Prevention and Principle 2: Atom Economy [1] [8] [9]. A high-yield reaction can still be wasteful if it uses stoichiometric reagents or excess solvents that are not incorporated into the final product. Calculate the Atom Economy of your reaction to see what proportion of your starting materials ends up in the final product [1] [9]. Furthermore, calculate the Process Mass Intensity (PMI) or E-Factor to quantify your total waste generation, as these metrics account for all materials used, including solvents and reagents [1] [9]. Optimizing towards a catalytic system (Principle 9) can often resolve this conflict between yield and waste mass [8] [9].

Q2: How can I objectively compare the "greenness" of two different solvents for my reaction?

A2: Selecting a safer solvent (Principle 5) requires a multi-faceted comparison. First, consult a recognized Greener Solvent List to identify recommended alternatives [9]. Your comparison should then be based on:

- Hazard Profiles: Compare Safety Data Sheet (SDS) classifications for health and environmental toxicity [10] [8].

- Environmental Impact: Consider factors like ozone depletion potential, global warming potential, and potential for atmospheric smog formation.

- Reaction Efficiency: A greener solvent must still allow your reaction to proceed effectively. Use tools like Linear Solvation Energy Relationships (LSER) to understand solvent effects and predict reaction performance in alternative solvents [11]. A comprehensive spreadsheet tool that combines LSER analysis with solvent greenness calculations is available to assist in this in-silico evaluation [11].

Q3: My reaction requires a highly reactive, toxic reagent. How can I reconcile this with Principle 3 (Less Hazardous Chemical Syntheses)?

A3: The phrase "wherever practicable" in Principle 3 acknowledges that such reagents are sometimes necessary [1]. Your strategy should be two-fold:

- Containment and Accident Prevention: If the reagent cannot be substituted, focus on Principle 12 (Inherently Safer Chemistry for Accident Prevention). Design your process to minimize the potential for accidents through engineering controls (e.g., closed-system processing, scrubbing) and by minimizing the inventory of the hazardous substance [10] [8].

- Catalytic Alternatives: Investigate the literature for catalytic pathways that can achieve the same transformation without the stoichiometric use of the hazardous reagent. The use of selective catalysts (Principle 9) is often the key to replacing toxic reagents [8] [9].

Quantitative Metrics for Reaction Assessment

The following metrics are essential for quantifying your adherence to core green chemistry principles.

Table 1: Core Green Chemistry Metrics

| Metric | Formula | Interpretation | Ideal Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| E-Factor [9] | Total Mass of Waste (kg) / Mass of Product (kg) |

Lower is better; indicates less waste generated per product mass. | 0 |

| Process Mass Intensity (PMI) [1] [9] | Total Mass in Process (kg) / Mass of Product (kg) |

Lower is better; encompasses all materials used. PMI = E-Factor + 1. | 1 |

| Atom Economy [1] [9] | (FW of Desired Product / Σ FW of All Reactants) x 100% |

Higher is better; theoretical maximum atoms from reactants in product. | 100% |

Table 2: EcoScale Penalty Points for Reaction Assessment

The EcoScale is a semi-quantitative metric that penalizes processes for yield, cost, safety, and practicality. A higher score (closer to 100) is better [9].

| Parameter | Example Penalty Points |

|---|---|

| Yield | (100 - %Yield)/2 |

| Safety (Hazard Codes) | T (Toxic): 5 pts; E (Explosive): 10 pts [9] |

| Technical Setup | Inert gas atmosphere: 1 pt; Special glassware: 1 pt [9] |

| Temperature/Time | Heating >1 hour: 3 pts; Cooling <0°C: 5 pts [9] |

| Workup and Purification | Liquid-liquid extraction: 3 pts; Classical chromatography: 10 pts [9] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Measurements

Protocol 1: Calculating Process Mass Intensity (PMI) for an API Synthesis

Objective: To accurately determine the total mass intensity of synthesizing an Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API), providing a clear picture of resource efficiency [1].

Methodology:

- Material Inventory: Record the mass (in kg) of every input material for the synthesis. This includes the target API, all reactants, catalysts, solvents for reaction and purification, and any process aids [1] [9].

- Product Mass: Record the final mass (in kg) of the isolated and purified API.

- Calculation: Input the recorded masses into the PMI formula from Table 1. For multi-step syntheses, calculate the PMI for each step and the cumulative PMI for the entire process.

- Interpretation: A high PMI indicates a resource-intensive process. The ACS Green Chemistry Institute Pharmaceutical Roundtable has used this metric to achieve dramatic, ten-fold waste reductions in API manufacturing [1].

Protocol 2: Variable Time Normalization Analysis (VTNA) for Reaction Optimization

Objective: To decouple the effects of catalyst decay and changing reactant concentrations on reaction rate, enabling more effective kinetic analysis and optimization for greener outcomes [11].

Methodology:

- Data Collection: Conduct a series of reactions where you vary the initial concentration of one reactant at a time while keeping others in excess. Use in-situ monitoring (e.g., FTIR, NMR) or periodic sampling to track reactant conversion or product formation over time [11].

- Data Transformation: Use a comprehensive spreadsheet tool to apply the VTNA method. This involves integrating hypothetical rate laws and normalizing time to determine which model best fits the experimental data across all different initial conditions [11].

- Optimization: Once the correct rate law is established, use the model to predict optimal reaction conditions (e.g., reactant ratios, catalyst loading, temperature) that maximize conversion and selectivity while minimizing waste and energy use. These predictions should be confirmed experimentally [11].

Green Chemistry Reaction Optimization Workflow

The following diagram illustrates a logical workflow for integrating green chemistry principles into reaction optimization.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Greener Chemistry

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Renewable Feedstocks (e.g., bio-based platform molecules) | Starting materials derived from biomass, aligning with Principle 7 (Use Renewable Feedstocks) to reduce reliance on depletable fossil fuels [10] [8]. |

| Heterogeneous or Biocatalysts | Reusable catalysts or highly selective enzymatic catalysts that minimize waste, aligning with Principle 9 (Catalysis) and reducing the need for stoichiometric, hazardous reagents (Principle 3) [11] [8] [9]. |

| Solvent Selection Guide | A curated list (e.g., ACS GCI Pharmaceutical Roundtable Solvent Guide) is essential for applying Principle 5 (Safer Solvents), helping to replace hazardous solvents like chlorinated or polar aprotic solvents with safer alternatives [9]. |

| In-situ Analytical Probes (e.g., FTIR, Raman) | Enable Principle 11 (Real-time Analysis), allowing for monitoring and control of reactions to prevent byproduct formation and ensure optimal conversion [8]. |

| Comprehensive Spreadsheet Tool | A tool that combines kinetic analysis (VTNA), solvent effect modeling (LSER), and green metric calculation. This is crucial for in-silico optimization and understanding the variables that control reaction chemistry before running experiments [11]. |

| 2-Amylanthraquinone | 2-Amylanthraquinone, CAS:13936-21-5, MF:C19H18O2, MW:278.3 g/mol |

| Arsenenous acid | Arsenenous acid, CAS:13768-07-5, MF:AsHO2, MW:107.928 g/mol |

How Kinetic Analysis Informs Hazard Reduction and Environmental Impact Assessment

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting Low Product Conversion in Green Synthesis

Problem: Low yield or slow reaction rate during optimization of a synthetic pathway. Investigation & Resolution Flowchart:

Detailed Steps:

- Perform Kinetic Analysis: Use Variable Time Normalization Analysis (VTNA) to determine the order of the reaction with respect to each reactant. This is a crucial first step as the order dictates how the reaction rate depends on reactant concentration [2] [11].

- Determine Reaction Orders: Input concentration-time data into a specialized spreadsheet tool. Test different potential reaction orders; the correct orders will cause data from experiments with different initial concentrations to overlap when plotted, revealing the intrinsic rate constant [2].

- Calculate Rate Constant: Once the reaction order is known, the spreadsheet will automatically calculate the rate constant (k) for your experimental conditions [2].

- Model Solvent Effects: Use Linear Solvation Energy Relationships (LSER). The spreadsheet correlates the natural log of your rate constants (ln k) with Kamlet-Abboud-Taft solvatochromic parameters (α, β, π*) to create an equation that predicts how solvent properties affect the reaction rate [2].

- Compare and Adjust: The model helps identify solvent properties that accelerate the reaction. Use the spreadsheet's solvent selection guide to find greener, higher-performing solvent alternatives [2].

Guide 2: Troubleshooting Hazardous Reaction Conditions

Problem: Assessing process safety risks from uncontrolled exothermic reactions. Investigation & Resolution Flowchart:

Detailed Steps:

- Chemical Kinetics Evaluation: Conduct laboratory tests (e.g., calorimetry) to determine key kinetic and thermodynamic parameters [12].

- Determine Key Parameters: This includes quantifying the reaction enthalpy (heat flow), activation energy (Ea), and reaction rate constants under various temperatures and concentrations [12].

- Identify Hazards: Use the kinetic data to model worst-case scenarios. This helps identify the potential for thermal runaway, dangerous pressure buildup, or the generation of toxic gases [12].

- Design Safety Systems: The kinetic data provides a basis for designing safety systems, such as specifying the required capacity and response time for emergency relief vents [12].

- Define Safe Operating Windows: Kinetic evaluation helps establish the Process Safety Time (PST), which is the time available for safety systems to act before a hazardous condition is reached [12].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How can kinetic analysis specifically help me make my chemical synthesis greener? Kinetic analysis is the foundation for informed green chemistry optimization. It allows you to:

- Reduce Waste: By understanding reaction rates and orders, you can optimize conditions for maximum yield and minimize unwanted side products [2].

- Select Safer Solvents: Linear Solvation Energy Relationships (LSER) model how solvent properties affect reaction rate, allowing you to replace hazardous solvents with safer, high-performing alternatives without sacrificing efficiency [2].

- Lower Energy Consumption: Determining activation parameters (ΔH‡ and ΔS‡) helps identify opportunities to run reactions at lower temperatures or for shorter times, saving energy [2].

Q2: I have concentration-time data for my reaction. What's a practical method to determine the reaction order? Use Variable Time Normalization Analysis (VTNA). This method involves testing different potential reaction orders in a spreadsheet. When you plot your data using the correct order, the data points from experiments with different initial concentrations will overlap, revealing a single, unified curve and allowing you to determine the true rate constant [2] [11].

Q3: In process safety, what key parameters are obtained from a chemical kinetics evaluation? A thorough evaluation provides [12]:

- Reaction rate constants and activation energy (Ea)

- Reaction enthalpy (heat of reaction)

- Reaction orders with respect to each reactant

- Data on pressure generation and potential for gas release

Q4: Can you give a real-world example where kinetics explain environmental or health hazard reduction? Yes. The safety of the pesticide malathion at low environmental doses is explained by its competing kinetic pathways. It is detoxified via carboxylesterase-mediated decarboxylation about 750 times faster than it is activated by cytochrome P450s into its toxic metabolite, malaoxon. This kinetic preference for detoxification over activation is a built-in safety feature that reduces hazard [13].

Q5: We are developing a new chemical substance. How can kinetics help predict its environmental distribution? Kinetic distribution models use physicochemical data (e.g., vapor pressure, water solubility, partition coefficient) to simulate how a chemical will move and degrade in environmental compartments (air, water, soil). This is more accurate than stationary models and helps predict environmental fate and potential exposure risks before a chemical is widely produced [14].

Quantitative Data for Reaction Optimization

Table 1: Key Kinetic Parameters from Case Studies

| Reaction / Process | Key Kinetic Parameter | Numerical Value | Significance for Hazard & Green Chemistry |

|---|---|---|---|

| Malathion Detoxification [13] | Carboxylesterase Detoxification Rate | 30 nmol/(min·mg·µM) | Detoxification is ~750x faster than activation, explaining low toxicity at environmental doses. |

| Malathion Activation [13] | CYP2C19 Activation Rate | 0.040 nmol/(min·mg·µM) | Slow activation to the toxic malaoxon limits cholinergic risk. |

| Biodiesel Production [15] | Activation Energy (Ea) | 21.65 kJ/mol | Low Ea indicates a less energy-intensive process, improving sustainability. |

| Aza-Michael Addition [2] | Solvent Effect Correlations | ln(k) = -12.1 + 3.1β + 4.2π* | Allows for predictive selection of green solvents that maintain high reaction rates. |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Kinetic Analysis & Optimization

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Na/SiOâ‚‚@TiOâ‚‚ Catalyst | Heterogeneous base catalyst for transesterification. | Biodiesel production from waste cooking oil; reusable and reduces wastewater vs. homogeneous catalysts [15]. |

| Human Carboxylesterase (HuCE1) | Hydrolyzes malathion to non-toxic carboxylic acids. | Key detoxifying enzyme; critical for understanding metabolic fate and toxicity of organophosphates [13]. |

| SiOâ‚‚@TiOâ‚‚ Core-Shell Support | Provides a high-surface-area, thermally stable support for catalyst impregnation. | Used in developing heterogeneous catalysts for greener synthesis [15]. |

| Kamlet-Abboud-Taft Solvatochromic Parameters | Quantify solvent properties (H-bond donation α, acceptance β, polarity π*). | Used in LSER to mathematically model and predict solvent effects on reaction rates for greener solvent selection [2]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining Reaction Kinetics and Orders via VTNA

Objective: To determine the order of a reaction with respect to its reactants and calculate its rate constant using Variable Time Normalization Analysis.

Materials:

- Reaction optimization spreadsheet tool (as referenced in [2])

- Concentration-time data for reactants and products from multiple experiments with different initial concentrations.

Methodology:

- Data Entry: Input your experimental data into the "Data entry" worksheet of the spreadsheet. This includes concentrations of all relevant species at various time points for each set of initial conditions [2].

- VTNA Processing: Navigate to the "Kinetics" worksheet. The spreadsheet will guide you to test different values for the order of reaction with respect to each reactant.

- Order Determination: The correct reaction orders are identified when the concentration-time data from all different experiments collapse onto a single, master curve when plotted. This convergence indicates that the variable time normalization has successfully accounted for the different initial conditions.

- Rate Constant Calculation: Once the correct orders are input, the spreadsheet will automatically calculate the apparent rate constant (k) for the reaction under those specific conditions [2].

Protocol 2: Evaluating Solvent Effects using LSER

Objective: To derive a Linear Solvation Energy Relationship that predicts how solvent polarity affects your reaction rate.

Materials:

- Rate constants (k) for the reaction performed in multiple different solvents, all at the same temperature and with the same reaction order.

- Database of Kamlet-Abboud-Taft parameters (α, β, π*) for the solvents used.

- Reaction optimization spreadsheet tool [2].

Methodology:

- Data Compilation: In the "Solvent effects" worksheet, input the calculated ln(k) values for each solvent alongside the corresponding solvent parameters (α, β, π*, Vm) [2].

- Regression Analysis: Use the spreadsheet's built-in multiple linear regression function to generate an equation of the form:

ln(k) = C + aα + bβ + cπ* + ... - Model Interpretation: The coefficients (a, b, c) quantify how strongly each solvent property influences the reaction rate. A positive coefficient for β, for example, means the reaction is accelerated by hydrogen bond accepting solvents.

- Solvent Selection: Use this equation in the "Solvent selection" worksheet to predict performance in untested solvents and identify those that are both high-performing and have a green safety profile according to guides like CHEM21 [2].

Metric Definitions and Industry Benchmarks

Green chemistry metrics are essential for quantifying the efficiency and environmental performance of chemical processes, providing tangible goals for optimization in research and industry [16]. The table below summarizes the core mass-based metrics and illustrates how performance expectations vary across chemical industry sectors.

Table 1: Core Green Chemistry Metrics and Industry-Specific E-Factors

| Metric Name | Calculation Formula | Ideal Value | Primary Focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atom Economy (AE) [16] [17] | ( \text{AE} = \frac{\text{Molecular Mass of Desired Product}}{\text{Sum of Molecular Masses of All Reactants}} \times 100\% ) | 100% | Intrinsic efficiency of a reaction's stoichiometry. |

| Environmental Factor (E-Factor) [18] [16] [19] | ( \text{E-Factor} = \frac{\text{Total Mass of Waste Produced}}{\text{Total Mass of Product}} ) | 0 | Total waste generated by a process, including solvents, reagents, and process materials. |

| Reaction Mass Efficiency (RME) [16] | ( \text{RME} = \frac{\text{Actual Mass of Desired Product}}{\text{Total Mass of Reactants Used}} \times 100\% ) | 100% | Practical efficiency combining yield, stoichiometry, and reagent use. |

| Industry Sector | Typical Annual Production (tonnes) | Typical E-Factor Range [16] [19] |

|---|---|---|

| Oil Refining | 106 – 108 | ~0.1 |

| Bulk Chemicals | 104 – 106 | <1 – 5 |

| Fine Chemicals | 102 – 104 | 5 – >50 |

| Pharmaceuticals | 10 – 103 | 25 – >100 |

Experimental Protocols for Metric Determination

Accurately determining these metrics requires careful data collection throughout your experimental workflow. The following protocol provides a standardized methodology.

Detailed Experimental Methodology

Step 1: Pre-Experimental Calculation of Atom Economy

- Action: Based on your planned synthetic route, calculate the atom economy using the molecular masses of all stoichiometric reactants [17]. This predictive metric helps assess the inherent "greenness" of the route before beginning laboratory work.

- Data Recording: Record the theoretical atom economy percentage in your lab notebook.

Step 2: Data Collection During Reaction and Work-up

- Action: Precisely measure and record the masses of all reactants, solvents, catalysts, and work-up reagents (e.g., acids, bases, drying agents) used in the experiment [18].

- Action: After isolating and purifying the product, measure the final mass of the desired product and determine the percentage yield [16].

- Data Recording: Maintain a comprehensive mass balance table for all materials entering and leaving the process.

Step 3: Post-Experimental Calculation of E-Factor and RME

- Action: Calculate Total Waste Mass.

- Simple E-Factor (sEF): For initial route scouting, exclude solvent and water mass [19].

Waste mass = (Total mass of reactants) - (Mass of product) - Complete E-Factor (cEF): For a more comprehensive view, include all materials, including solvents and water, assuming no recycling [19].

Waste mass = (Total mass of all input materials) - (Mass of product)

- Simple E-Factor (sEF): For initial route scouting, exclude solvent and water mass [19].

- Action: Calculate Final Metrics.

- E-Factor: Divide the total waste mass by the mass of the product [18] [19].

- Reaction Mass Efficiency (RME): Calculate using the formula:

RME = (Actual Mass of Product / Total Mass of Reactants) * 100%[16]. This can also be derived from Atom Economy, Percentage Yield, and Excess Reactant Factor [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Materials for Green Chemistry Metric Analysis

| Item/Category | Function/Justification | Green Chemistry Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Balance | Precisely measures mass inputs and product output, which is fundamental for all mass-based calculations. | Accurate data is critical for reliable metric values. |

| Solvents (from CHEM21 Guide) [2] | Medium for reaction to occur. High-performance solvents can enhance kinetics and reduce waste. | Refer to solvent selection guides (e.g., CHEM21) to choose safer, "greener" options (e.g., water, ethanol, 2-methyl-THF) over hazardous ones (e.g., DMF, DCM) [2]. |

| Stoichiometric Reagents | Reactants consumed in the reaction according to molar ratios. | Prioritize reagents that maximize incorporation into the final product to improve Atom Economy. |

| Catalysts | Substances that increase reaction rate without being consumed. | Enable lower energy requirements and reduce waste from stoichiometric reagents, significantly improving E-Factor [17]. |

| Work-up Reagents | Materials used in purification (e.g., aqueous acid/base, drying agents). | Account for their mass in the complete E-Factor. Their use should be minimized where possible. |

| 2-Bornanone oxime | 2-Bornanone oxime, CAS:13559-66-5, MF:C10H17NO, MW:167.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Trisodium arsenite | Trisodium arsenite, CAS:13464-37-4, MF:AsNa3O3, MW:191.889 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My reaction has a 100% yield but a low Atom Economy. What does this mean, and how can I improve it?

- A: A high yield means you efficiently converted reactants into your desired product, but a low Atom Economy indicates that a significant portion of the reactant atoms ended up in byproducts rather than the product [20]. To improve Atom Economy, consider redesigning your synthesis to use addition or rearrangement reactions, which inherently produce fewer or no byproducts, instead of substitution or elimination reactions [17].

Q2: Why is my E-Factor so high even though my yield is good?

- A: The E-factor accounts for all waste, not just chemical byproducts [18]. A high E-factor with a good yield typically points to inefficiencies outside the core reaction. Common culprits include:

- Solvent Usage: Solvents often constitute the largest portion of waste, especially in pharmaceuticals [19]. Consider solvent recycling or switching to a safer alternative with a better environmental health and safety (EHS) profile [2].

- Excess Reagents: Using large excesses of reagents to drive the reaction increases waste mass [16].

- Work-up and Purification: The mass of acids, bases, drying agents, and chromatography media used in purification contributes significantly to the total waste [18].

Q3: How do I account for a recovered and recycled solvent in my E-Factor calculation?

- A: The original E-factor concept encouraged accounting for solvent recycling. The true commercial E-factor includes only solvent losses, not the total mass used [19]. In a lab setting, you can calculate two values:

- Complete E-Factor (cEF): Includes all solvent mass used (assuming no recycling). This represents the worst-case scenario.

- Adjusted E-Factor: Includes only the mass of solvent that was not recovered (e.g., lost to evaporation or contamination). This provides a more realistic view of an optimized process.

Q4: What is the difference between Atom Economy and Reaction Mass Efficiency?

- A: Atom Economy is a theoretical metric calculated from the reaction's stoichiometry; it assumes 100% yield and no excess reagents [17] [19]. Reaction Mass Efficiency is a practical metric based on the actual masses used and the mass of product obtained; it incorporates the chemical yield, stoichiometry, and the use of excess reagents into a single number, providing a more complete picture of the reaction's efficiency on the bench [16].

Common Calculation Errors and Data Interpretation

- Incorrectly Defining Waste: Remember that waste is "everything but the desired product" [19]. Omitting the mass of work-up reagents, spent catalysts, or solvents is a common error that leads to an unrealistically low E-Factor.

- Ignoring the Nature of Waste: The E-factor is a mass-based metric and does not differentiate between a kilogram of sodium chloride and a kilogram of heavy metal waste [18]. Always consider the Environmental Quotient (EQ)—the nature and hazard of the waste—alongside the E-factor for a complete environmental assessment [18] [19].

- Inconsistent System Boundaries: When comparing E-factors for multi-step syntheses, ensure you are defining the starting point consistently. The E-factor can be artificially reduced by purchasing an advanced intermediate instead of synthesizing it in-house [19].

Visualization of Metric Relationships and Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between the core green chemistry metrics and the experimental workflow for their determination.

Figure 1: Green Metrics Calculation Workflow. This chart outlines the sequential process for determining Atom Economy, E-Factor, and Reaction Mass Efficiency, from experimental planning to final analysis.

The relationship between the key concepts in green chemistry optimization, from fundamental data to ultimate goals, is shown below.

Figure 2: Optimization Logic Flow. This diagram shows the progression from raw experimental data to calculated metrics, which inform process understanding and ultimately drive optimization toward the goals of green chemistry.

Practical Methods for Kinetic Analysis and Green Solvent Selection

Implementing Variable Time Normalization Analysis (VTNA) for Complex Reaction Order Determination

Variable Time Normalization Analysis (VTNA) represents a significant advancement in chemical kinetics, enabling researchers to determine reaction orders and rate constants from concentration profiles obtained via modern reaction monitoring techniques. This method provides a graphical approach that uses variable time normalization to compare entire concentration reaction profiles visually, allowing for the determination of the order in each reaction component with fewer experiments than traditional methods. For researchers in green chemistry and drug development, VTNA facilitates rapid kinetic information extraction, which is crucial for optimizing reactions to be safer, more efficient, and less wasteful, aligning with the core principles of green chemistry [21]. The integration of tools like comprehensive spreadsheets and the newer, coding-free Auto-VTNA platform further democratizes access to this powerful analysis, making it applicable for both education and industrial research [22] [23].

This guide provides a technical support center for scientists implementing VTNA in their workflows, featuring troubleshooting guides, FAQs, and detailed experimental protocols.

# Understanding VTNA and Its Role in Green Chemistry

# FAQs: VTNA Fundamentals

What is Variable Time Normalization Analysis (VTNA)? VTNA is a graphical analysis method that uses a variable normalization of the time scale to enable the visual comparison of entire concentration reaction profiles. This allows for the determination of the reaction order in each component and the observed rate constant ((k_{obs})) with just a few experiments [21].

How does VTNA advance Green Chemistry goals? By enabling efficient reaction optimization with fewer experiments, VTNA directly supports the goals of green chemistry. A thorough understanding of kinetics allows for:

- Waste Reduction: Optimizing conditions to maximize yield and minimize byproducts.

- Energy Efficiency: Identifying faster reaction pathways or conditions that allow for lower temperature operation.

- Safer Chemicals: Facilitating the selection of greener, high-performance solvents by understanding their kinetic effects [22].

What are the advantages of VTNA over traditional kinetic analysis? Traditional methods often disregard part of the data-rich results provided by modern monitoring tools. VTNA leverages all the concentration data, reducing the number of experiments needed and simplifying the data treatment process [21].

What tools are available to perform VTNA?

- Spreadsheet Tools: Customized spreadsheets can be designed to process kinetic data by VTNA, generate Linear Solvation Energy Relationships (LSER), and calculate solvent greenness [22].

- Auto-VTNA: A newer, free-to-use, coding-free tool for rapidly analyzing kinetic data in a robust, quantifiable manner. It includes a Graphical User Interface (GUI) for ease of use [23].

# The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and their functions in a typical VTNA-driven reaction optimization study, as exemplified by the aza-Michael addition case study [22].

Table 1: Key Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function / Relevance in VTNA Experiments |

|---|---|

| Dimethyl itaconate | A model Michael acceptor used in kinetic studies to elucidate reaction mechanisms and orders [22]. |

| Piperidine / Dibutylamine | Amine nucleophiles used in aza-Michael model reactions; their concentration profiles are critical for VTNA [22]. |

| Solvent Library | A range of solvents with varying polarities (e.g., DMSO, Isopropanol) is essential for probing solvent effects and building LSER models [22]. |

| Kamlet-Abboud-Taft Parameters | Solvatochromic parameters ((\alpha), (\beta), (\pi^*)) that quantify solvent properties; used in LSER to correlate solvent polarity with reaction rate [22]. |

| CHEM21 Solvent Selection Guide | A guide that ranks solvents based on Safety (S), Health (H), and Environment (E) criteria; used to assess solvent greenness alongside kinetic performance [22]. |

| NMR Spectroscopy | A key reaction monitoring technique ((^1H) NMR) for obtaining precise concentration-time data for reactants and products [22]. |

| Auto-VTNA Calculator GUI | A software tool that automates the VTNA process, making it accessible without requiring advanced programming knowledge [23]. |

| Terminaline | Terminaline (CAS 15112-49-9) - High-Purity Reference Standard |

| Butetamate | Butetamate, CAS:14007-64-8, MF:C16H25NO2, MW:263.37 g/mol |

# Experimental Protocol: A Step-by-Step VTNA Workflow

The following diagram and protocol outline the general workflow for implementing VTNA, integrating kinetic analysis with green chemistry principles.

Diagram Title: VTNA Reaction Optimization Workflow

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Experimental Data Collection

- Reaction Selection: Choose a model reaction, such as the aza-Michael addition of dimethyl itaconate and piperidine [22].

- Reaction Monitoring: Conduct multiple reaction runs at a constant temperature with varying initial concentrations of reactants. Use a technique like (^1H) NMR spectroscopy to measure the concentration of reaction components at defined time intervals [22].

- Data Recording: Compile the concentration-time data for all experiments into a structured format (e.g., a CSV file or spreadsheet).

Data Processing with VTNA

- Tool Selection: Input the concentration-time data into your chosen tool, such as the reaction optimization spreadsheet [22] or the Auto-VTNA Calculator GUI [23].

- Order Determination: The core of VTNA involves testing different potential reaction orders for each component. The tool will re-normalize the time axis for each experiment. The correct orders are identified when the concentration profiles from all experiments overlap onto a single, master curve [22] [21].

- Rate Constant Extraction: Once the correct orders are found, the tool automatically calculates the observed rate constant ((k_{obs})) for each experimental run [22].

Solvent Effect Analysis (LSER)

- Data Compilation: Gather the (k_{obs}) values for reactions performed in different solvents that share the same determined reaction mechanism/orders.

- Model Building: Use the spreadsheet tool to perform a multiple linear regression, correlating the natural log of the rate constant ( (\ln(k)) ) with the Kamlet-Abboud-Taft solvatochromic parameters ((\alpha), (\beta), (\pi^*)) and molar volume ((V_m)) of the solvents [22].

- Interpretation: The resulting LSER equation (e.g., (\ln(k) = C + a\beta + b\pi^*)) reveals which solvent properties accelerate the reaction, providing insight into the reaction mechanism and guiding solvent selection [22].

Green Chemistry Evaluation and Optimization

- Greenness Assessment: Consult the CHEM21 solvent selection guide to obtain Safety (S), Health (H), and Environment (E) scores for the solvents tested [22].

- Informed Selection: Plot (\ln(k)) against the solvent's greenness score (e.g., the sum of S+H+E). This visualization helps identify solvents that offer a strong combination of high reaction performance and a superior environmental health and safety profile [22].

- Prediction and Validation: Use the established LSER model to predict the rate constant in a green solvent that was not experimentally tested. Subsequently, validate the prediction by running the reaction under the proposed optimal conditions [22].

# Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

# Troubleshooting Common VTNA Issues

Problem: Concentration profiles fail to overlap in VTNA.

- Potential Cause 1: Incorrectly proposed rate law. The reaction mechanism may be more complex than initially assumed.

- Solution: Test a wider range of potential orders. Consider mechanisms involving catalyst decomposition, inhibition, or different pathways in different solvents [22].

- Potential Cause 2: Inconsistent experimental conditions.

- Solution: Ensure temperature is perfectly controlled across all runs. Verify the accuracy of initial concentrations and the precision of the analytical method used for concentration measurement.

Problem: The LSER model has poor statistical significance (low R² value).

- Potential Cause 1: The set of solvents includes outliers that support a different reaction mechanism.

- Solution: As seen in the aza-Michael case, protic solvents like isopropanol can induce a change from a trimolecular to a bimolecular mechanism [22]. Re-run the LSER analysis using only solvents that demonstrated the same kinetic order.

- Potential Cause 2: The key solvent property influencing the rate is not adequately captured by the parameters used.

- Solution: Experiment with different combinations of solvent parameters. Ensure the dataset includes solvents with a wide range of values for each parameter.

Problem: The "greenest" solvent has a very slow reaction rate.

- Potential Cause: Inherent trade-off between kinetic performance and environmental/health criteria.

- Solution: Use the VTNA and LSER data to optimize other reaction parameters. Consider increasing catalyst loading, raising temperature moderately, or using a mixture of a green solvent with a minimal amount of a high-performance co-solvent to balance rate and greenness [22].

# FAQs: Advanced Implementation

Can VTNA be applied to catalytic reactions? Yes, VTNA is particularly valuable in catalysis for determining the order in the catalyst and elucidating complex catalytic cycles, as highlighted in its seminal description [21].

How does Auto-VTNA improve upon the spreadsheet method? Auto-VTNA is a dedicated, automated platform that likely provides a more robust and quantifiable analysis of the overlay quality, reducing user bias and potential errors in manual spreadsheet calculations [23].

What is the connection between VTNA and AI-driven process optimization? VTNA provides the fundamental kinetic understanding that is the prerequisite for advanced control strategies. The rich, mechanistically informative kinetic data from VTNA can feed into AI-driven models for dynamic, real-time process regulation, as seen in advanced bioprocesses [24].

Linear Solvation Energy Relationships (LSER) for Understanding Solvent Effects

Core Concepts and FAQs

What is the fundamental principle behind Linear Solvation Energy Relationships (LSER)?

LSER is a quantitative model that correlates free-energy-related properties of solutes (e.g., partition coefficients, reaction rates) with descriptors of their molecular structure [25]. The core principle is that the logarithmic value of a solute property (log SP) in a given system can be described as a linear combination of the solute's capabilities to engage in different types of intermolecular interactions [26]. The most common model is the Abraham solvation parameter model [25].

What do the terms in the LSER equation represent?

The general LSER equation is expressed as [26] [27]: log SP = c + eE + sS + aA + bB + vV

The following table details the meaning of each solute descriptor and the corresponding system coefficient.

Table: Breakdown of the LSER Equation Terms

| Symbol | Solute Descriptor (Property of the solute) | System Coefficient (Property of the solvent/system) | Physical Interaction Represented |

|---|---|---|---|

| E | Excess molar refraction | e | Interaction with solute π- and n-electron pairs [26] |

| S | Dipolarity/Polarizability | s | Dipole-dipole and dipole-induced dipole interactions [26] |

| A | Hydrogen-bond acidity | b | Solvent's hydrogen-bond basicity (complementary to solute acidity) [26] |

| B | Hydrogen-bond basicity | a | Solvent's hydrogen-bond acidity (complementary to solute basicity) [26] |

| V | McGowan's characteristic volume | v | Cavity formation and dispersion interactions [25] [27] |

| c | - | Constant (Intercept) | System-specific constant [26] |

How can LSER support Green Chemistry principles in reaction optimization?

LSER directly supports Green Chemistry by enabling a rational solvent selection process that enhances reaction efficiency while minimizing environmental and health hazards [28] [22]. By building an LSER model for your reaction, you can:

- Understand Mechanism: Identify the specific solvent properties (e.g., hydrogen-bond basicity, dipolarity) that accelerate the reaction, providing insight into the reaction mechanism [22].

- Predict Performance: Predict reaction rates in untested solvents, saving time and resources [22].

- Select Greener Solvents: Identify solvents with excellent environmental health and safety (EHS) profiles that also promote high reaction rates, moving away from problematic solvents like DMF and DMSO when possible [22].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Lack of LSER Descriptors for a Novel Solute

Issue: You are working with a novel compound and cannot find its experimental LSER descriptors (A, B, S, etc.) in the literature.

Solution:

- Estimate using Group Contributions: Use established "rule of thumb" estimation methods based on molecular functional groups [29]. These rules allow for a quick approximation of LSER variable values for a vast array of organic compounds.

- Quantum Chemical Calculations: For more advanced applications, descriptors can be calculated using computational chemistry methods, though this requires validation.

Problem: Poor Statistical Fit of the LSER Model

Issue: After collecting data and performing multiple linear regression, your LSER model has a low R² value or high root-mean-square error (RMSE).

Solution:

- Check Solute Diversity: Ensure your set of test solutes spans a wide range of descriptor values and minimizes intercorrelations between them [26]. A set of 15-20 diverse compounds is often sufficient.

- Verify Data Quality: Confirm the accuracy of your experimentally measured solute property (log SP, e.g., partition coefficient, log K).

- Inspect for Outliers: Identify and investigate data points that deviate significantly from the model, as they may indicate measurement errors or unique molecular interactions not captured by the standard descriptors.

Problem: LSER Model Fails to Predict Solvent Performance for a New Reaction

Issue: You have developed an LSER for a process, but it does not accurately predict the outcomes for your specific chemical reaction.

Solution:

- Correlate with Kinetic Data: Use LSER to correlate solvent properties not with a partition coefficient, but directly with the logarithmic rate constant (ln k) of your reaction [22]. This directly links solvent properties to reaction efficiency.

- Use Appropriate Polarity Parameters: When building a model for reaction kinetics, you can use solvent polarity parameters like the Kamlet-Abboud-Taft parameters (α, β, π*), which describe hydrogen bond donating ability, hydrogen bond accepting ability, and dipolarity/polarizability, respectively [22].

- Example Protocol:

- Conduct your reaction in a set of ~10 different solvents with diverse polarities.

- Determine the rate constant (k) for the reaction in each solvent.

- Perform a multiple linear regression of ln(k) against the solvent parameters (e.g., α, β, π, Vm).

- The resulting equation (e.g., ln(k) = C + pπ + aα + bβ) reveals which solvent properties enhance the reaction rate [22].

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Methodology: Characterizing a Material's Sorption Properties using LSER

This protocol is adapted from methods used to characterize solid-phase microextraction (SPME) fibers and can be applied to study any solid polymer or material [26].

Objective: To determine the LSER system constants for a material, allowing for the prediction of its sorption capacity for any solute with known descriptors.

Materials and Reagents: Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Set of 14-20 Probe Solutes | A diverse set of compounds (e.g., diethyl ether, benzene, 1-propanol, nitroethane) covering a wide range of E, S, A, B, and V values [26]. |

| Material Under Study | The polymer, stationary phase, or solid sorbent being characterized. |

| Gas Chromatograph (GC) | Equipment for separating and quantifying the probe solutes. |

| Inert Gas Carrier | Helium or Nitrogen, to carry solutes through the GC system. |

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: If the material is a fiber or solid phase, expose it to a headspace or solution containing a known, dilute concentration of the probe solute mixture.

- Equilibration: Allow the system to reach equilibrium sorption.

- Desorption and Analysis: Transfer the sorbed solutes into a GC (e.g., by thermal desorption for a fiber) and analyze them.

- Data Calculation: For each solute i, calculate the distribution constant, Kc, which is the concentration in the fiber phase (Cf) divided by the concentration in the gas phase (Cg) at equilibrium [26].

- Key Formula: ( Kc = \frac{Cf}{C_g} )

- Regression Analysis: Perform a multiple linear regression of the logarithmic distribution constants (log Kc) for all probe solutes against their known solute descriptors [26].

- Key Formula: ( \log K_c = c + eE + sS + aA + bB + vV )

- Model Validation: The resulting equation with its system constants (e, s, a, b, v) defines the sorption properties of your material. Validate the model's accuracy (R², RMSE) and use it to predict log Kc for other compounds.

The workflow for this experimental process is summarized in the following diagram:

Example LSER Models from Literature

The following table summarizes published LSER models for different systems, demonstrating the format and utility of a successfully calibrated model.

Table: Example LSER Models for Different Partitioning Systems

| Partitioning System | LSER Model Equation | Notes | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low-Density Polyethylene (LDPE) / Water | log Ki,LDPE/W = -0.529 + 1.098E - 1.557S - 2.991A - 4.617B + 3.886V | High accuracy (R²=0.991, RMSE=0.264). Critical for predicting leachables. | [30] |

| Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) SPME Fiber / Air | log Kc = -0.65 + 0.37S + 1.27A + 1.28B + 0.99L | Uses L (hexadecane-air partition coeff.) instead of V. Shows high capacity for H-bond basic solutes. | [26] |

| Polyacrylate (PA) SPME Fiber / Air | log Kc = 0.16 + 0.68S + 1.98A + 1.93B + 0.74L | Compared to PDMS, has greater capacity for polar and H-bonding compounds. | [26] |

Solvent selection is a critical multi-objective challenge in chemical research and development, particularly within the framework of green chemistry and reaction kinetics optimization. The ideal solvent must satisfy competing demands: delivering optimal reaction performance (e.g., high yield, fast kinetics), ensuring workplace safety, and minimizing environmental impact. With an estimated 28 million tons of solvents used annually and a vast array of potential candidates, a systematic approach is not just beneficial—it is essential for efficient and sustainable process development [31]. This guide provides troubleshooting advice and methodologies to help researchers navigate this complex decision-making process.

Core Concepts: The Solvent Selection Trinity

Selecting a solvent requires a balanced consideration of three core pillars:

- Performance: The solvent must effectively support the reaction, influencing both reaction equilibrium and kinetics. It should also facilitate easy product separation and catalyst recycling [32].

- Greenness: This involves assessing the entire lifecycle of the solvent, from its source (preferring renewable feedstocks) to its end-of-life, using metrics to evaluate environmental, health, and safety (EHS) impacts [2] [31].

- Safety: This encompasses hazards for the operator, including toxicity (carcinogenicity, developmental toxicity, etc.), flammability, and volatility [33] [34].

The following table summarizes key properties and criteria across these three pillars that must be evaluated during solvent selection.

Table 1: Key Properties for Solvent Evaluation

| Category | Property | Description & Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Performance | Dielectric Constant / Polarity | Influces solvation of reactants, transition states, and products; can shift reaction equilibrium and rate [32]. |

| Performance | Hydrogen Bonding (H-donor/Acceptor) | Affects solvation of species capable of hydrogen bonding; can significantly impact reaction kinetics [2]. |

| Performance | Boiling Point | Critical for solvent recovery via distillation; very high boiling points increase energy costs [35]. |

| Greenness & Safety | Environmental, Health, Safety (EHS) Profile | A composite of hazards including toxicity, carcinogenicity, mutagenicity, and environmental persistence [35] [2]. |

| Greenness & Safety | Volatile Organic Compound (VOC) | High volatility leads to atmospheric emissions and exposure risks, requiring control measures [31]. |

Systematic Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Methodology 1: Computer-Aided Screening and Molecular Design

Computer-aided methods enable the rapid screening of thousands of solvent candidates before any laboratory work begins.

Table 2: Computational Approaches for Solvent Screening

| Method | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| COSMO-RS (COnductor-like Screening MOdel for Real Solvents) | Predicts thermodynamic properties (e.g., activity coefficients, solubility) and solvent-solute interactions based on quantum mechanics [35] [36]. | Screening for solvents that provide high reactant solubility and favorable reaction equilibrium [32]. |

| Computer-Aided Molecular Design (CAMD) | An optimization-based method that designs novel solvent molecules with desired properties from molecular groups [32]. | Designing a new, benign solvent that meets specific process constraints (e.g., boiling point, polarity, non-toxicity). |

| Linear Solvation Energy Relationships (LSER) | Correlates reaction rates (ln(k)) with solvent polarity parameters (e.g., α, β, π*) to understand and predict solvent effects on kinetics [2]. | Identifying that a reaction is accelerated by polar, hydrogen-bond accepting solvents, enabling targeted solvent selection [2]. |

Protocol: A Hierarchical Screening Workflow

This integrated workflow combines database screening and process optimization to identify the best solvent candidates.

- Initial Database Screening: Start with a large database of potential solvents (e.g., COSMObase). Apply physical property constraints:

- Structural constraints: Exclude molecules with unstable functional groups (e.g., carbon double bonds) [35].

- Boiling point: Set a range to avoid azeotrope formation and ensure feasible separation [35].

- Miscibility: Ensure the solvent has the correct miscibility with reactants and products for the intended separation process (e.g., liquid-liquid extraction) [35].

- EHS Screening: Evaluate the remaining candidates using Environmental, Health, and Safety criteria. Use Quantitative Structure-Property Relationship (QSPR) models (e.g., from software like VEGA or EPISuite) to predict [35]:

- Persistence, Bioaccumulation, Toxicity (PBT)

- Carcinogenicity, Mutagenicity, and Developmental Toxicity

- Reject all solvents classified as hazardous. This step is critical for replacing toxic solvents like DMF, which is on the SVHC (Substances of Very High Concern) list [35].

- Process Optimization: The shortlisted "green" candidates undergo rigorous process optimization (e.g., using mixed-integer non-linear programming) and are benchmarked against a standard solvent (e.g., DMF). The goal is to identify the candidate that delivers similar or better economic performance without the toxicity [35].

Methodology 2: High-Throughput Experimental (HTE) Screening

When predictive models are uncertain or for final validation, HTE provides empirical data on solvent performance.

Protocol: High-Throughput Screening for Reaction Optimization

- Platform Setup: Use a robotic platform or manual kit (e.g., 24-well or 96-well plate format) to run parallel reactions under an inert atmosphere if necessary [37].

- Experiment Design: Prepare identical reaction mixtures, varying only the solvent across the wells. Keep other variables (temperature, reactant concentrations, catalyst loading) constant.

- Reaction Execution and Monitoring: Initiate the reactions simultaneously and use automated analytical techniques (e.g., in-situ NMR, GC-FID, HPLC) to monitor reaction progress and measure rate constants (k) for each solvent [2].

- Data Analysis:

- Plot the natural logarithm of the rate constant (ln(k)) for each solvent.

- Construct a Linear Solvation Energy Relationship (LSER) by performing a multiple linear regression of ln(k) against Kamlet-Abboud-Taft solvatochromic parameters (α, β, π*) [2].

- The resulting equation (e.g.,

ln(k) = C + aα + bβ + cπ*) reveals which solvent properties (hydrogen-bond donation, acceptance, polarity) accelerate the reaction.

Troubleshooting Common Solvent Selection Issues

Table 3: Frequently Asked Questions and Troubleshooting Guide

| Question / Issue | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| A new "green" solvent gives unacceptably slow reaction rates. | The solvent's polarity/polarizability or hydrogen-bonding properties are not optimal for stabilizing the transition state of the reaction. | Use the LSER model from HTE data to identify the key polarity parameters. Select an alternative green solvent that better matches these parameters [2]. |

| How can I quickly compare the overall greenness of two solvents? | Lack of a standardized, multi-factorial scoring system. | Consult guides like the CHEM21 Solvent Selection Guide. It provides ranked scores for Safety (S), Health (H), and Environment (E) on a scale of 1 (best) to 10 (worst). The "best" solvent has the lowest cumulative or worst-score [2]. |

| The solvent recovery (distillation) is too energy-intensive. | The solvent has an excessively high boiling point. | During the initial computer-aided screening, add an upper constraint for the boiling point to filter out high-boiling candidates [35]. |

| We need to replace a toxic solvent like DMF or NMP. | These solvents are often high-performing but are now recognized as substances of very high concern (SVHC). | Implement the hierarchical screening workflow. For example, in the hydroformylation of olefins, a systematic screening identified a non-toxic solvent that performed similarly to DMF in process optimization [35]. |

| How do I balance reaction performance with solvent greenness? | Perceived trade-off between efficiency and safety. | Create a "Greenness vs. Performance" plot. Plot ln(k) (performance) against a greenness metric (e.g., the CHEM21 score). This visualization helps identify solvents that offer the best compromise, such as DMSO, which often provides high rates with a relatively better EHS profile than DMF [2]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

This table lists key tools and materials that enable the methodologies described in this guide.

Table 4: Key Reagents and Tools for Systematic Solvent Selection

| Item | Function in Solvent Selection |

|---|---|

| COSMObase / COSMOtherm | A database and software for predicting thermodynamic properties and solvent-solute interactions via the COSMO-RS method, crucial for in silico screening [35] [36]. |

| Kamlet-Abboud-Taft Solvatochromic Parameters | A set of empirically derived parameters (α, β, π*) that quantitatively describe a solvent's polarity. They are the independent variables in LSER models for understanding kinetic performance [2]. |

| High-Throughput Screening Kits | Pre-prepared kits (e.g., for cross-coupling, catalysis) that allow for rapid parallel experimentation in standard lab formats (e.g., 24-well plates), drastically reducing experimental time [37]. |

| CHEM21 Solvent Selection Guide | A widely recognized guide that ranks common solvents based on combined safety, health, and environmental criteria, providing a quick reference for greenness [2]. |

| VEGA / EPISuite QSPR Platforms | Software platforms hosting Quantitative Structure-Property Relationship models used to predict a molecule's EHS properties, such as toxicity and environmental fate, during the screening process [35]. |

| 2-Methyltryptoline | 2-Methyltryptoline, CAS:13100-00-0, MF:C12H14N2, MW:186.25 g/mol |

| Vanadium disulfide | Vanadium Disulfide (VS2) for Advanced Research |

Catalyst Design for Enhanced Selectivity and Reduced Step Count

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs): Core Concepts

FAQ 1: Why is catalysis considered a foundational pillar of green chemistry? Catalysis is central to green chemistry because it enables more efficient chemical processes. It directly contributes to reducing energy consumption, minimizing waste, and using more environmentally friendly feedstocks. Over 90% of all industrial chemical processes are based on catalysis, underscoring its critical economic and environmental importance. By lowering activation energies and enhancing reaction specificity, catalysts help achieve the dual goals of environmental benefit and economic gain [38] [39].

FAQ 2: What is the key conceptual advantage of using catalytic over stoichiometric reagents? The primary advantage is dramatic waste reduction. Stoichiometric reagents are consumed in full during a reaction, generating significant byproducts. In contrast, catalysts are not consumed and can be used repeatedly, turning over many reaction cycles. This eliminates the waste associated with stoichiometric reagents, for instance, in reductions or oxidations, and prevents the salt formation common when using molecular acids or bases [39].

FAQ 3: How can catalyst design directly reduce the number of steps in a synthetic pathway? Advanced catalyst design can create multifunctional systems that promote several transformations in a single reaction vessel (tandem or one-pot reactions). For example, a single catalyst might facilitate a sequence of dehydrogenation, bond rearrangement, and hydrogenation. This consolidates multiple discrete synthetic steps, saving time, reducing solvent and energy use, and simplifying product purification. Catalysis is crucial for designing such streamlined, atom-economical routes [38].

FAQ 4: What recent technological advances are accelerating catalyst design? The integration of machine learning (ML) and computational methods is revolutionizing the field. ML algorithms can analyze vast datasets to predict catalytic activity and optimize reaction conditions, drastically shortening the development cycle for new catalysts. Frameworks like "Catlas" use graph-based models to efficiently explore material design spaces and identify promising candidates for specific reactions [40] [41].

Troubleshooting Guides: Common Experimental Challenges

Low Product Selectivity

| Problem Area | Possible Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Proposed Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Competitive Reactions | The catalyst surface favors a competing side reaction (e.g., H2 evolution in CO2 reduction) [42]. | Measure product distribution; vary reactant partial pressures to observe selectivity shifts. | Modify the catalyst's surface properties via alloying [43] or defect engineering to suppress the undesired pathway [42]. |

| Unoptimized Reaction Environment | Operating conditions inadvertently favor the formation of byproducts. | Systematically screen parameters like pH, temperature, and light intensity (for photocatalysis) [42]. | Optimize operating conditions; for aqueous CO2 reduction, control pH to manage proton availability and suppress H2 evolution [42]. |

| Weak Intermediate Binding | Key intermediates desorb too easily, leading to incomplete reactions and byproducts [43]. | Use in situ spectroscopy to monitor surface species; perform DFT calculations on binding energies. | Employ surface engineering to strengthen the adsorption of key intermediates, guiding them toward the desired product [43]. |

Poor Catalyst Efficiency

| Problem Area | Possible Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Proposed Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inefficient Active Sites | Low density of active sites or poor atomic efficiency. | Characterize with XAFS, HAADF-STEM; measure turnover frequency (TOF). | Develop Single-Atom Catalysts (SACs) to maximize atomic efficiency and expose highly active sites [41]. |

| Rapid Deactivation | Catalyst sintering, leaching, or coking under reaction conditions. | Analyze spent catalyst with TEM, TGA, and ICP-OES. | Utilize stable support materials (e.g., doped oxides, MOFs) to anchor metal particles and prevent aggregation [44] [41]. |

| Mass Transfer Limitations | Reactants cannot efficiently reach the active sites. | Study the effect of agitation speed (liquid) or flow rate (gas) on reaction rate. | Design catalysts with hierarchical porosity or use nanostructured supports to enhance diffusion [41]. |

Challenges in Scaling Up

| Problem Area | Possible Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Proposed Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Batch-to-Batch Variability | Inconsistent catalyst synthesis at larger scales. | Rigorously characterize different batches (BET surface area, XRD, ICP-OES). | Implement continuous flow synthesis for more reproducible catalyst production [44]. |

| Difficulty in Separation | Homogeneous catalysts are hard to remove from the product stream. | N/A | Design heterogeneous catalysts or immobilize active species on recyclable supports (e.g., silica, magnetic nanoparticles) [44] [41]. |

| Process Thermodynamics | Reaction equilibrium limits conversion, especially for direct CO2 utilization [44]. | Determine thermodynamic equilibrium conversion. | Shift equilibrium by removing a co-product (e.g., using dehydrating agents) or designing processes that circumvent thermodynamic limitations [44]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Optimizing a Selective Catalyst System

This protocol details the synthesis and testing of a bimetallic PdCu/ZnO catalyst for selective methanol steam reforming (MSR), based on a recent study [43].

Objective

To synthesize a PdCu/ZnO catalyst via incipient wetness impregnation and evaluate its performance in steering the MSR reaction pathway towards CO2 and H2, while minimizing CO byproduct formation.

Materials and Synthesis

- Materials: ZnO support, Palladium(II) nitrate solution, Copper(II) nitrate trihydrate, Deionized water, 10% H2/N2 gas mixture.

- Synthesis of PdCu1/ZnO Catalyst:

- Impregnation: Dissolve appropriate amounts of Pd and Cu precursors (e.g., for 1 wt% of each metal) in deionized water. Slowly add the aqueous solution to a measured amount of ZnO support powder until the incipient wetness point is reached.

- Drying: Leave the impregnated solid at room temperature for 12 hours, then dry at 100°C for 6 hours.

- Calcination and Reduction: Activate the catalyst in a tubular reactor under a flowing 10% H2/N2 mixture (100 mL min−1). Heat to 300°C at a rate of 5°C min−1 and hold for 2 hours to reduce the metal precursors and form the active PdCu alloy.

Characterization Workflow

The experimental workflow for developing and validating the catalyst is methodical.

Performance Testing and Data Analysis

- Testing Setup: Conduct MSR reactions in a fixed-bed reactor at 200°C. Use a Gas Chromatograph (GC) equipped with a TCD and FID to analyze the effluent gas stream and quantify H2, CO2, CO, and unreacted methanol.

- Key Performance Metrics:

- Methanol Conversion: (%) = (Methanolin - Methanolout) / Methanol_in × 100%.

- CO Selectivity: (%) = Moles of CO produced / Total moles of carbon-containing products × 100%.

- Expected Outcome: The PdCu1/ZnO catalyst is expected to show a ~2.3-fold increase in activity and a ~75% decrease in CO selectivity compared to a monometallic Pd/ZnO catalyst, demonstrating the success of the alloying strategy [43].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The following table details key materials used in advanced catalyst design, as featured in the cited research.

| Item | Function & Application | Example from Research |

|---|---|---|

| Single-Atom Catalysts (SACs) | Maximize atomic efficiency and provide uniform active sites for high-selectivity reactions like CO2 electroreduction [41]. | Single-atom Ni catalysts for hydrogenation; FeN4 on graphene for nitric oxide reduction [40] [41]. |