Kinetic Optimization in Drug Discovery: Strategies for Waste Minimization and Enhanced Therapeutic Efficacy

This article explores the critical intersection of binding kinetics and waste minimization in modern drug discovery.

Kinetic Optimization in Drug Discovery: Strategies for Waste Minimization and Enhanced Therapeutic Efficacy

Abstract

This article explores the critical intersection of binding kinetics and waste minimization in modern drug discovery. Tailored for researchers and development professionals, it details how optimizing the kinetic parameters of drug-target interactions—specifically association (k_on) and dissociation (k_off) rates—can simultaneously enhance therapeutic efficacy, improve safety profiles, and reduce resource waste throughout the R&D pipeline. The scope encompasses foundational kinetic principles, advanced measurement methodologies, AI-driven optimization techniques, and integrated frameworks that align molecular design with sustainable laboratory and manufacturing practices, offering a holistic guide to building more efficient and environmentally conscious drug development processes.

Beyond Affinity: Unpacking the Principles of Drug-Target Binding Kinetics

Core Definitions and Their Significance

What are kon, koff, and Residence Time?

In the context of drug discovery and development, binding kinetics describes the dynamic interaction between a drug (analyte) and its biological target (ligand). The following parameters are crucial for characterizing this interaction [1]:

- k_on (or kâ‚): The association rate constant. It measures the rate at which the drug and target form a complex.

- k_off (or kâ‚‘): The dissociation rate constant. It measures the rate at which the drug-target complex breaks apart, releasing the free, active target.

- Residence Time (táµ£): The reciprocal of the dissociation rate constant (1/k_off). It quantitatively represents the lifetime of the drug-target complex [2].

- KD (Equilibrium Dissociation Constant): The ratio koff/k_on. It represents the affinity of the interaction, or the analyte concentration at which half of the ligands are occupied at equilibrium [1].

Why are these parameters important for research?

While traditional drug discovery often focused primarily on optimizing binding affinity (KD), there is a growing recognition that the kinetic parameters kon and koff provide critical, non-equilibrium insights that better predict a drug's efficacy and safety in the dynamic environment of the human body [2]. A long residence time (slow koff) can lead to prolonged target occupancy, which may enhance therapeutic efficacy and allow for less frequent dosing. Furthermore, a drug that dissociates rapidly from off-target proteins (short off-target residence time) can have an improved therapeutic window and reduced side-effects [2].

How does this relate to waste minimization strategies?

Kinetic optimization is a powerful tool for intellectual waste minimization. By understanding and optimizing kon and koff early in the research process, you can:

- Reduce Attrition: Select drug candidates with a higher probability of clinical success, minimizing the resources spent on failed leads.

- Enable Rational Design: Use structure-kinetic relationships (SKRs) to guide molecular modifications, reducing the number of synthetic cycles and associated chemical waste.

- Improve Predictive Power: Relying solely on equilibrium affinity (K_D) can be misleading; kinetic parameters provide a more physiologically relevant understanding of target engagement, leading to better-informed candidate selection [2].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: My sensorgram shows a poor fit during kinetic analysis. What could be the cause?

Poor fitting often stems from an incorrect underlying model for the binding interaction.

- Potential Cause: The binding mechanism may be more complex than a simple 1:1 interaction. It could involve a two-step induced-fit model, where an initial binding event is followed by a conformational change in the target protein [2].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Inspect the Sensorgram: For a simple 1:1 model, the association and dissociation curves should be smooth and fit a single exponential. Deviations from this can indicate a more complex mechanism.

- Test Different Models: Fit your data to alternative models, such as a two-state (conformational change) or bivalent analyte model, and compare the goodness of fit (e.g., via residual plots and Chi² values).

- Validate with Ground States: Use structural tools like X-ray crystallography to investigate potential conformational changes in the target protein associated with binding [2].

FAQ 2: My k_off is too fast to measure accurately with multi-cycle kinetics. What are my options?

Very slow dissociation can make traditional multi-cycle kinetics impractical due to long waiting times for complete dissociation between cycles.

- Potential Cause: The drug has a very long residence time, meaning the complex is highly stable and dissociates minimally during the standard dissociation phase [1].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Switch to Regeneration-Free Kinetics: Employ methods like waveRAPID, which uses repeated analyte pulses of increasing duration at a single concentration. This method drastically reduces assay time and reagent consumption when dissociation is slow [1].

- Optimize Surface Regeneration: If multi-cycle kinetics must be used, rigorously optimize the regeneration solution and contact time to fully dissociate the complex without damaging the immobilized ligand.

FAQ 3: Why is my calculated K_D strong, but the cellular efficacy is weak?

This discrepancy highlights the limitation of relying solely on equilibrium affinity.

- Potential Cause: The drug may have a slow on-rate (kon), which delays the formation of the drug-target complex in a non-equilibrium cellular environment. The thermodynamic affinity (KD) might be strong, but the kinetics of engagement are not favorable for the biological system [2].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Measure Full Kinetics: Determine both kon and koff instead of just the equilibrium K_D.

- Focus on Residence Time: Evaluate if a long residence time (slow koff) correlates better with cellular efficacy than KD for your target. For many targets, prolonged occupancy is a key driver of the pharmacological effect [2].

FAQ 4: How can I rationally design a compound for a longer residence time?

This is a key challenge in medicinal chemistry, as residence time depends on both ground state and transition state energies.

- Potential Strategy: Structure-Kinetic Relationships (SKRs). Analyze structural data to understand molecular interactions that stabilize the final complex and/or destabilize the transition state for dissociation [2].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Stabilize the Ground State: Use X-ray structures of drug-target complexes to identify interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts) that can be optimized to make the bound state more stable, thereby reducing k_off [2].

- Destabilize the Transition State: This is more challenging, as transition states are short-lived. Computational methods like molecular dynamics (MD) simulations can be used to model the dissociation pathway and identify points of steric clash or energetic barriers that could be targeted with specific molecular modifications [2].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Determining kon and koff via Multi-Cycle Kinetics on a Biosensor

This is a standard method for obtaining robust kinetic data using instruments like the Malvern Panalytical WAVEsystem or similar SPR/BLI platforms [1].

- Ligand Immobilization: Covalently immobilize the purified target protein (ligand) onto a biosensor chip surface.

- Analyte Preparation: Prepare a dilution series (at least 4-6 concentrations) of the drug candidate (analyte), ideally spanning a range from 0.1 to 10 times the expected K_D [1].

- Data Collection Cycle:

- Baseline: Establish a stable baseline with running buffer.

- Association Phase: Inject analyte over the ligand surface for a sufficient time to observe binding curvature.

- Dissociation Phase: Replace analyte solution with running buffer to monitor the decay of the complex.

- Regeneration: Apply a regeneration solution (e.g., low pH buffer) to completely dissociate any remaining analyte and prepare the surface for the next cycle.

- Data Analysis: Simultaneously fit the sensorgrams from all analyte concentrations to a 1:1 binding model (or a more complex model if justified) using the instrument's software to extract kon, koff, and K_D.

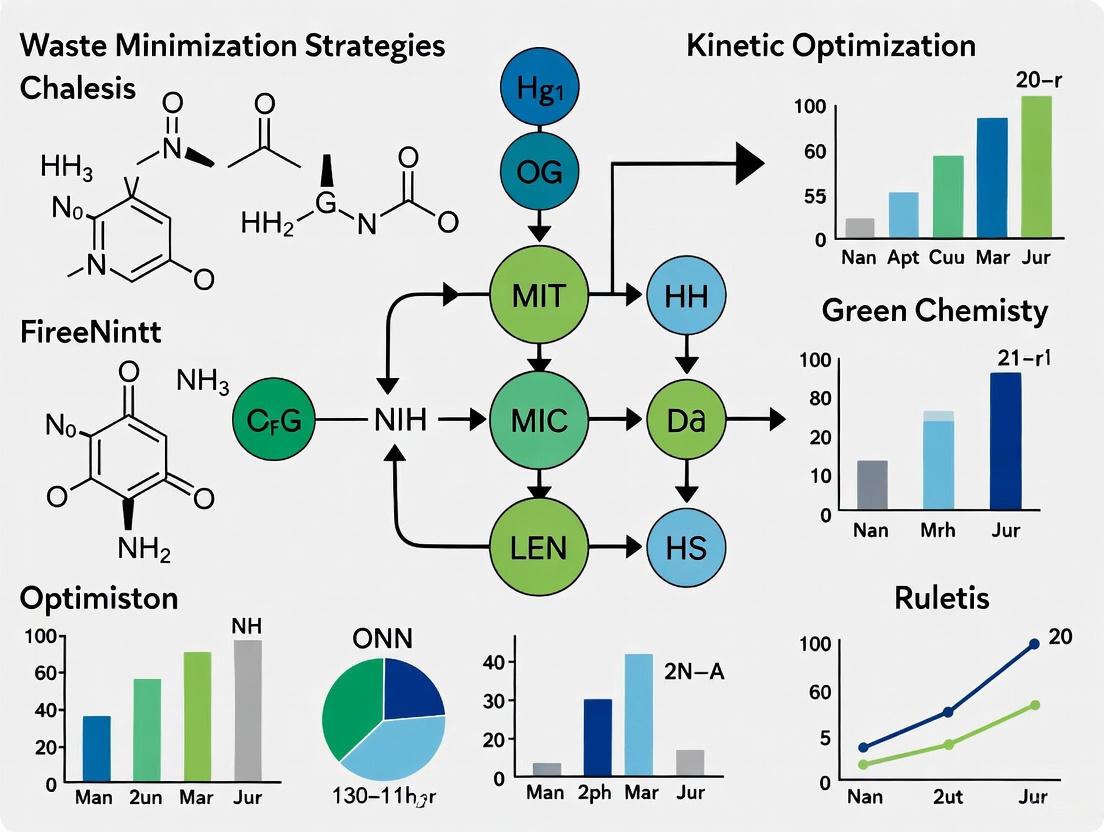

The workflow for this protocol is summarized in the following diagram:

Diagram Title: Multi-Cycle Kinetic Assay Workflow

Protocol 2: Investigating Mechanism via Structure-Kinetic Relationships (SKR)

This methodology integrates kinetic data with structural biology to guide the rational optimization of residence time [2].

- Generate Kinetic Data: Determine kon and koff for an initial lead compound using Protocol 1.

- Obtain Structural Data: Solve a high-resolution crystal structure of the lead compound bound to its target.

- Analyze Binding Interactions: Identify key molecular interactions (hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic patches, salt bridges) in the ground-state complex.

- Design Analogues: Synthesize chemical analogues designed to enhance favorable interactions or introduce new ones that could stabilize the complex or create steric hindrance against dissociation.

- Profile New Compounds: Measure the kinetic parameters for all new analogues.

- Iterate and Correlate: Correlate structural changes with changes in k_off to build a predictive SKR model for your target, enabling more informed compound design.

Data Presentation: Kinetic Parameters in Drug Discovery

The table below summarizes kinetic and residence time data for various drug targets, illustrating the diversity of mechanisms and timescales [2].

Table 1: Experimentally Determined Kinetic Parameters for Selected Drug Targets

| Target | Compound / Inhibitor | k_off-derived Residence Time (táµ£) | Mechanism for Prolonged Residence Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| S. aureus FabI | Alkyl diphenyl ether PT119 | 12.5 hr (20°C) | Ordering of the substrate binding loop (SBL) [2]. |

| Thermolysin | Phosphonopeptide 18 | 168 days | Interaction with Asn112 prevents conformational change required for ligand release [2]. |

| p38α MAP kinase | Dibenzosuberone 6g | 32 hr | Type 1.5 inhibition disrupting the R-spine [2]. |

| Adenosine Aâ‚‚A receptor | ZM241358 | 84 min | ETH triad forms a lid preventing ligand dissociation [2]. |

| Btk (reversible covalent) | Pyrazolopyrimidine 9 | 167 hr | Steric hindrance of α-proton abstraction [2]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Binding Kinetic Studies

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Biosensor Chip | A solid surface (e.g., carboxymethyl dextran) for the covalent immobilization of the target protein (ligand) [1]. |

| Purified Target Protein (Ligand) | The biologically relevant, purified protein to be immobilized. High purity is critical for specific binding data. |

| Analytes / Drug Candidates | Small molecules or biologics to be tested for binding. Must be soluble and stable in the assay buffer. |

| HBS-EP Buffer | A standard running buffer (HEPES, Saline, EDTA, Surfactant P20) for biosensor experiments, providing a consistent physiological-like pH and ionic strength. |

| Regeneration Solution | A solution (e.g., glycine-HCl at low pH) used to break the drug-target complex without damaging the immobilized ligand, preparing the surface for a new cycle [1]. |

| L-Valine-15N,d8 | L-Valine-15N,d8, MF:C5H11NO2, MW:126.19 g/mol |

| Alr2-IN-3 | Alr2-IN-3, MF:C17H12N2O3S2, MW:356.4 g/mol |

Why Kinetics Trump Pure Thermodynamics in Open Biological Systems

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why can't I rely solely on binding affinity (a thermodynamic parameter) to predict my drug's efficacy in vivo? While binding affinity (often reported as IC50 or Kd) indicates how tightly a drug binds its target, it does not describe the time the drug spends bound to the target, known as its residence time [3]. In the dynamic, open system of the human body, where drug and target concentrations fluctuate, a drug with a long residence time (slow dissociation rate, koff) can maintain therapeutic action longer, leading to better efficacy and potentially lower, less frequent dosing [3]. Relying only on affinity can be misleading, as the same affinity can result from different combinations of association and dissociation rates [3].

Q2: My bioremediation process is thermodynamically favorable but isn't proceeding. What could be the issue? This is a classic sign of a kinetic limitation. Thermodynamics confirms a reaction can happen, but kinetics determines how fast it will happen [4] [5]. The process is likely facing a high activation energy barrier.

- Common Causes: The microbial community or enzyme catalyst may be inhibited, or a key nutrient may be lacking.

- Troubleshooting Step: Review your kinetic data (e.g., from a Monod or Michaelis-Menten model) to identify the rate-limiting step. For instance, in aquaculture bioremediation, optimizing light intensity for microalgae was crucial to overcome photoinhibition and achieve predicted nutrient removal rates [6].

Q3: How do stochastic effects impact my kinetic models of a biological process? In cellular systems, where some molecules may have very low copy numbers, deterministic models (using ordinary differential equations) can break down [7]. The discrete and random nature of individual molecular interactions can lead to significant relative fluctuations that affect the system's behavior.

- Solution: For processes involving low-abundance biomolecules (e.g., gene transcription factors), stochastic simulation algorithms are more appropriate. These methods explicitly model the randomness of each reaction event, providing a more realistic picture of system dynamics, especially when spatial organization is important [7].

Q4: How can I ensure my kinetic model is thermodynamically consistent? It is possible for a kinetic model to be internally consistent kinetically but violate the laws of thermodynamics, particularly detailed balance. This often happens when model parameters are sourced from different experiments, each with its own uncertainty [8].

- Solution: Use a maximum likelihood approach (as in the

multibindsoftware package) to combine all experimental kinetic and thermodynamic measurements. This method reconciles the data to produce a model that is statistically most consistent with your measurements while also being thermodynamically rigorous [8].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent or Physically Impossible Results from Kinetic Model

Symptoms: Model predictions violate fundamental principles, such as the system producing a perpetual motion machine-like output or cycle closure errors.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Violation of Detailed Balance: The model's cycles do not obey thermodynamics. | Check if the product of forward rates around a closed cycle equals the product of backward rates. Use the Hill relation for validation [8]. | Use a thermodynamic reconciliation tool like multibind [8]. |

| Incorrect Assumption of Well-Stirred System: Spatial gradients are significant. | Compare model results to spatially resolved experimental data. Check if diffusion timescales are comparable to reaction timescales [7]. | Refine the model by subdividing the system volume into smaller, well-stirred subvolumes and incorporating diffusion reactions between them [7]. |

| High Stochastic Fluctuations: Low copy numbers cause deterministic models to fail. | Check the molecular counts of key species. If they are low (e.g., tens or hundreds), stochastic effects are likely important [7]. | Switch from deterministic ODEs to a stochastic simulation algorithm (SSA) or a hybrid method [7]. |

Problem: Low Biogas Yield in Anaerobic Digestion

Symptoms: Lower than expected biogas production or a slow production rate during the treatment of organic waste like tannery fleshings.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Slow Hydrolysis/Kinetic Limitation: The breakdown of complex solids is rate-limiting. | Fit cumulative biogas production data to a first-order kinetic or modified Gompertz model. A long lag phase (L) indicates slow hydrolysis [9]. | Implement a pretreatment step. Proteolytic enzyme pretreatment (e.g., with trypsin or papain) can liquefy the substrate and significantly increase biogas yield [9]. |

| Inhibited Microbial Activity: Toxicity or imbalance in the digestate. | Analyze the chemical composition of the digestate for inhibitors like ammonia or long-chain fatty acids [9]. | Adjust the feedstock composition or C/N ratio. Use a carefully selected seed sludge adapted to the inhibitors [9]. |

| Suboptimal Process Parameters: Temperature, pH, or retention time are not ideal. | Use Response Surface Methodology (RSM) to design experiments that find the optimal combination of process parameters [9]. | Optimize parameters like hydraulic retention time and substrate-to-inoculum ratio based on the statistical model developed from RSM [9]. |

Essential Kinetic Data and Models

The table below summarizes key quantitative data from different fields, illustrating how kinetic parameters are used to predict and optimize system behavior.

| System/Process | Key Kinetic Parameters | Quantitative Findings & Model Accuracy | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aquaculture Bioremediation | - Optimal light intensity: 100–120 µmol mâ»Â² sâ»Â¹- TN removal: 0.4639 mg/L/day- TP removal: 0.0638 mg/L/day | Predictive accuracy of polynomial models:- Biomass growth (R² = 0.997)- TN removal (R² = 0.980)- TP removal (R² = 0.990)- COD reduction (R² = 0.991) | [6] |

| Biogas Production | - Lag phase (L) from Gompertz model- Biogas production rate (R)- Ultimate biogas yield (Pâ‚€) | Model goodness-of-fit reported between 0.993 and 0.998 for first-order and modified Gompertz models [9]. | [9] |

| Drug-Target Binding | - Association rate constant (kon)- Dissociation rate constant (koff)- Residence Time (1/koff) | A long residence time, not just high affinity, is a key predictor of in vivo drug efficacy and duration of action [3]. | [3] |

| Methane Pyrolysis | - Activation Energy (E): Range of 20–421 kJ·molâ»Â¹- Isokinetic Temperature (Tiso): 1200–1450 K | The isoconversion temperature depends not only on thermodynamics but also on how the reaction is carried out, with temperature and pressure locally compensating [10]. | [10] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining Biokinetics for Waste Bioremediation using Microalgae

Objective: To optimize light intensity and nutrient concentrations for maximizing biomass growth and nutrient removal (e.g., Total Nitrogen, Total Phosphorus, COD) from aquaculture wastewater using Chlorococcum sp. [6].

Culture Setup:

- Inoculate Chlorocumm sp. in bioreactors containing aquaculture wastewater effluent.

- Maintain a constant temperature suitable for the microalgae (e.g., 25°C).

Parameter Optimization:

- Light Intensity Gradient: Expose parallel reactors to a range of light intensities (e.g., 50 to 150 µmol photons mâ»Â² sâ»Â¹).

- Nutrient Concentration: Monitor the depletion of TN, TP, and COD from the wastewater over time.

Data Collection:

- Regularly sample the reactors to measure:

- Biomass concentration (e.g., via optical density or dry weight).

- TN, TP, and COD using standard water analysis methods.

- Record data daily for the duration of the experiment (e.g., 10-14 days).

- Regularly sample the reactors to measure:

Kinetic Modeling:

- Fit the biomass growth and nutrient removal data to polynomial regression models to identify optimal conditions.

- Apply Monod and Michaelis-Menten kinetic models to the substrate (nutrient) consumption data to determine the maximum removal rates (Vmax) and half-saturation constants (Ks).

Validation:

- Run a final verification experiment under the identified optimal conditions (e.g., 100–120 µmol photons mâ»Â² sâ»Â¹) to confirm the predicted high removal rates [6].

Protocol 2: Measuring Enzyme-Mediated Biomethane Potential

Objective: To evaluate the enhancement of biogas production from tannery fleshings (TF) using proteolytic enzyme pretreatment [9].

Substrate Pretreatment:

- Experimental Group: Treat 1 kg of TF with a specific activity (e.g., 5U or 82.5 IU) of a proteolytic enzyme such as trypsin or papain.

- Control Group: Keep a separate batch of TF without enzyme addition.

Batch Reactor Setup:

- Load duplicate batch-scale reactors with a mixture of pretreated (or control) TF and bio-digested slurry (inoculum) in a defined ratio (e.g., 0.25:0.75).

- Seal the reactors and connect the gas outlet to a water displacement system to measure biogas production.

Monitoring:

- Daily Biogas Measurement: Record the volume of gas displaced by water daily.

- Methane Content Analysis: Periodically analyze the biogas composition by passing a sample through a 5% alkali solution to estimate CO2 absorption and calculate methane percentage [9].

Kinetic Analysis:

- Use the cumulative biogas production data to fit kinetic models.

- First-order model:

P = P₀[1 - exp(-k×t)] - Modified Gompertz model:

P = P₀ × exp[-exp( (R × 2.7183 / P₀)(L - t) + 1)]

- First-order model:

- Use non-linear regression (e.g., in IBM SPSS software) to determine parameters: ultimate biogas yield (Pâ‚€), rate constant (k), lag phase (L), and maximum production rate (R) [9].

- Use the cumulative biogas production data to fit kinetic models.

Statistical Optimization:

- Employ Response Surface Methodology (RSM) with a Box-Behnken design to optimize multiple parameters (e.g., enzyme dose, retention time, temperature) for maximum biogas yield [9].

Conceptual Diagrams

Thermodynamics vs. Kinetics

Kinetic Model Optimization Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function in Kinetic Optimization |

|---|---|

| Proteolytic Enzymes (Trypsin, Papain) | Pretreatment reagent to hydrolyze and liquefy protein-rich solid waste (e.g., tannery fleshings), breaking kinetic barriers to hydrolysis and accelerating the start of anaerobic digestion [9]. |

| Chlorococcum sp. Microalgae | A biological catalyst for aquaculture bioremediation. It consumes dissolved nutrients (N, P); its growth kinetics and nutrient uptake rates are optimized by controlling light intensity [6]. |

| Fluorescent Labels & Tags | Enable real-time tracking of biomolecular interactions (e.g., drug-target binding) in live cells, providing direct measurement of association and dissociation kinetics (kon, koff) [3]. |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Chip | A label-free biosensor surface used to immobilize a drug target. It directly measures the binding kinetics (kon, koff) of molecules in solution flowing over it [3]. |

| Iron/Nickel-Based Catalysts | Used in methane pyrolysis to lower the activation energy barrier of the reaction, thereby kinetically controlling the products (e.g., hydrogen yield) and the type of carbon structures formed [10]. |

| Dabcyl-AGHDAHASET-Edans | Dabcyl-AGHDAHASET-Edans, MF:C66H83N19O20S, MW:1494.5 g/mol |

| 4-Phenylbutyric acid-d2 | 4-Phenylbutyric acid-d2, MF:C10H12O2, MW:168.23 g/mol |

Technical FAQs: Resolving Key Challenges in Kinetic Studies

FAQ 1: Why should I invest in measuring binding kinetics when my compounds have excellent affinity (IC50/Kd) values? Affinity provides only a partial picture, measured at equilibrium, which is often not the state of the dynamic in vivo environment where drug concentrations fluctuate [3]. Two compounds with identical affinity can have vastly different association (kon) and dissociation (koff) rates, leading to different target occupancy profiles over time [11] [12]. Optimizing for a long residence time (1/koff) can enhance drug efficacy, sustain target engagement even after systemic drug concentration declines, and can be a key differentiator for efficacy and safety [13] [12].

FAQ 2: What is "kinetic selectivity" and how does it differ from thermodynamic selectivity? Thermodynamic selectivity is based on equilibrium affinity (Kd or IC50) for the primary target versus off-targets. If affinities are similar, a compound is deemed non-selective [11]. Kinetic selectivity, however, arises from differences in the on- and off-rates for different targets. A compound can have identical Kd values for two targets but a much slower off-rate (longer residence time) for one, leading to preferential and sustained engagement of that target over time, especially when drug concentrations are low [11] [13]. This can build a better safety margin and reduce adverse events [12].

FAQ 3: My lead compound shows a PK/PD disconnect. How can binding kinetics help? Systemic exposure (PK) sometimes poorly predicts pharmacodynamic effect (PD). Integrating binding kinetics into PK/PD models often bridges this gap. Conventional affinity-based models may underpredict efficacy and suggest higher doses than needed. Models incorporating kon and koff better predict true target engagement, drug dose, treatment schedule, and potential toxicities, resolving the observed disconnect [12].

FAQ 4: For which target classes is binding kinetics particularly critical? Evidence for the critical role of binding kinetics spans multiple target classes. The table below summarizes key examples documented in the literature [12].

Table 1: Documented Role of Binding Kinetics Across Target Classes

| Target Class | Specific Target Examples |

|---|---|

| GPCRs | A2A Adenosine Receptor, β2 Adrenergic Receptor, CCR5, M3 Muscarinic Receptor [13] [12] |

| Kinases | EGFR, Abl, p38α MAPK, CDKs, BTK [13] [12] |

| Proteases | BACE1, AChE [12] |

| Epigenetic Enzymes | DOT1L, EZH2 [12] |

| Nuclear Receptors | Estrogen Receptor (ER) [12] |

FAQ 5: Can a drug's residence time influence its dosing schedule? Yes. The duration of a drug's action is directly dependent on its dissociation rate (koff) from the target [12]. A longer residence time means the drug remains active for a longer period, which can allow for less frequent dosing [12]. For example, the antihypertensive drug Candesartan has a much longer residence time on the angiotensin receptor than Losartan, contributing to its longer-lasting efficacy and superior performance in the event of a missed dose [12].

Essential Experimental Protocols & Workflows

This section provides detailed methodologies for key experiments in kinetic profiling.

Protocol 1: Determining Kinetic Parameters via Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR)

Principle: SPR is a label-free technique that detects real-time biomolecular interactions by measuring changes in refractive index on a sensor surface [3].

Procedure:

- Immobilization: Covalently immobilize the purified target protein on a sensor chip.

- Association: Flow the drug compound at varying concentrations over the chip surface. Monitor the increase in Response Units (RU) as the drug binds to the target.

- Dissociation: Switch to a buffer-only flow. Monitor the decrease in RU as the drug dissociates.

- Regeneration: Apply a mild regeneration solution to remove any remaining bound compound, readying the surface for the next cycle.

- Data Analysis: Globally fit the resulting sensoryrams to a suitable binding model (e.g., 1:1 Langmuir) to extract the association rate constant (kon) and dissociation rate constant (koff). The equilibrium dissociation constant (Kd) is calculated as koff/kon, and the residence time as 1/koff [13] [3].

SPR Kinetic Analysis Workflow

Protocol 2: Investigating Kinetic Selectivity in a Cellular Context

Principle: This cell-based assay assesses time-dependent target occupancy and selectivity, moving beyond purified protein systems to a more physiologically relevant environment [3].

Procedure:

- Cell Preparation: Culture cells expressing the primary therapeutic target and a key off-target protein.

- Dosing & Incubation: Treat cells with the drug candidate at its effective concentration. Incubate for a set period to allow binding to reach equilibrium.

- Washout: At time zero, rapidly wash away the unbound compound from the medium.

- Time-Course Sampling: At various time points post-washout (e.g., 0, 30 min, 1, 2, 4, 8, 24 hours), collect cell samples.

- Occupancy Measurement: Use a specific technique (e.g., reporter assay, enzyme activity assay, immunoprecipitation) to measure the fraction of target and off-target that remains occupied by the drug.

- Data Analysis: Plot % target occupancy versus time. The rate of decline in occupancy reflects the dissociation rate (koff). Kinetic selectivity is demonstrated by a slower decline in occupancy for the primary target compared to the off-target.

Cellular Kinetic Selectivity Assay

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

A successful kinetic optimization campaign relies on high-quality reagents and tools. The table below lists essential materials and their functions.

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Tools for Kinetic Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Kinetic Research |

|---|---|

| Purified, Active Target Protein | Essential for biophysical assays (e.g., SPR). Protein must be in its native, functional conformation for reliable kinetic data [13]. |

| Stable Cell Lines | Engineered to consistently express the human target and relevant off-targets. Critical for cellular wash-out assays and evaluating binding in a more complex environment [3]. |

| Reference Ligands | Compounds with well-characterized binding kinetics (known kon/koff). Used as controls to validate new experimental setups and assays [13]. |

| SPR Sensor Chips | The solid support for immobilizing the target protein in SPR biosensors. Different chip chemistries (e.g., CM5, NTA) are available for various immobilization strategies [13]. |

| Radio-labeled or High-Affinity Fluorescent Ligands | Used in radioligand or fluorescence-based binding assays (e.g., FRET, TR-FRET) to monitor competition and displacement for determining binding parameters [3]. |

| Plm IV inhibitor-1 | Plm IV inhibitor-1, MF:C37H51N5O3, MW:613.8 g/mol |

| Epsilon-V1-2, Cys-conjugated | Epsilon-V1-2, Cys-conjugated, MF:C40H70N10O14S, MW:947.1 g/mol |

Data Presentation: Quantitative Insights

Summarizing and comparing kinetic data is crucial for lead optimization. The following table provides a template for presenting key parameters.

Table 3: Compound Kinetic Profiling and Selectivity Analysis

| Compound ID | Target | Kd (nM) | kon (Mâ»Â¹sâ»Â¹) | koff (sâ»Â¹) | Residence Time | Cellular IC50 (nM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lead A | On-Target (Kinase X) | 1.0 | 1.0 x 10ⶠ| 1.0 x 10â»Â³ | 16.7 min | 5.0 |

| Off-Target (Kinase Y) | 1.1 | 1.0 x 10âµ | 1.1 x 10â»â´ | 2.5 h | 5.5 | |

| Lead B | On-Target (Kinase X) | 1.0 | 1.0 x 10âµ | 1.0 x 10â»â´ | 2.8 h | 5.2 |

| Off-Target (Kinase Y) | 0.9 | 1.0 x 10ⶠ| 9.0 x 10â»â´ | 18.5 min | 4.8 | |

| Optimized Compound | On-Target (Kinase X) | 0.5 | 5.0 x 10âµ | 2.5 x 10â»âµ | 11.1 h | 2.5 |

| Off-Target (Kinase Y) | 0.5 | 1.0 x 10ⶠ| 5.0 x 10â»â´ | 33.3 min | 2.6 |

This illustrative data shows how Lead A and B have identical Kd values for the on- and off-target, suggesting no thermodynamic selectivity. However, their kinetic parameters reveal distinct profiles. The Optimized Compound achieves clear kinetic selectivity, with a residence time on the desired target (Kinase X) that is 20 times longer than on the off-target (Kinase Y), despite identical affinity.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the primary cause of a complete lack of assay window in a TR-FRET experiment? The most common reason is an incorrect instrument setup. Specifically, using the wrong emission filters will cause the assay to fail. Unlike other fluorescence assays, TR-FRET requires precise filter sets recommended for your specific instrument. You should first consult instrument setup guides to verify your configuration [14].

FAQ 2: Why might my calculated EC50/IC50 values differ from values reported in another lab, even using the same assay? The primary reason for differences in EC50 or IC50 between labs is typically variations in the prepared stock solutions. Differences in compound solubility or dilution can lead to concentration inaccuracies that directly impact the results [14].

FAQ 3: My compound is active in a biochemical assay but shows no activity in my cell-based assay. What are potential reasons? Several factors specific to the cellular environment could be at play:

- The compound may be unable to cross the cell membrane or could be actively pumped out of the cell.

- The compound might be targeting an inactive form of the kinase in the cell, whereas the biochemical assay uses the active form.

- The activity observed in the cell-based assay could be against an upstream or downstream kinase, rather than the intended target. A binding assay may be required to study the inactive kinase form [14].

FAQ 4: Why should I use ratiometric data analysis for my TR-FRET data instead of just the raw signal? Using a ratio of the acceptor emission signal to the donor emission signal is considered a best practice. The donor signal acts as an internal reference, which helps to account for pipetting variances and lot-to-lot variability in reagents. This ratiometric method normalizes the data, making it more robust and reliable than raw fluorescence units (RFU), which can be arbitrary and vary significantly between instruments [14].

FAQ 5: Is a large assay window alone a guarantee of a good, robust assay? No, the size of the assay window is not the only indicator of a robust assay. The Z'-factor is a key metric that assesses assay quality by considering both the assay window size and the variability (standard deviation) in your data. An assay with a large window but high noise can have a lower Z'-factor than an assay with a smaller window and low noise. Generally, assays with a Z'-factor greater than 0.5 are considered suitable for screening [14].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: No Assay Window in TR-FRET Assay

| Observation | Potential Cause | Investigation & Resolution |

|---|---|---|

| No signal or minimal difference between positive and negative controls. | Incorrect microplate reader setup or filters. | Verify the instrument setup using official guides. Confirm that the correct excitation and emission filters for your TR-FRET dye (Tb or Eu) are installed and properly aligned [14]. |

| Reagent or pipetting error. | Test the TR-FRET setup using control reagents. Ensure accurate pipetting and reagent preparation. Check reagent expiration dates and storage conditions [14]. |

Problem 2: Poor or Variable Z'-Factor

| Observation | Potential Cause | Investigation & Resolution | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High data variability leading to a Z'-factor below 0.5. | High signal noise or low assay window. | Calculate the Z'-factor using the formula: `1 - [3*(SDhighcontrol + SDlowcontrol) / | Meanhighcontrol - Meanlowcontrol | ]`. Optimize reagent concentrations, ensure cell health if applicable, and check for environmental inconsistencies (e.g., temperature fluctuations) to reduce variability [14]. |

| Edge effects in the microplate. | Uneven temperature across the plate. | Use a thermostatically controlled plate reader and allow for adequate pre-incubation for temperature equilibrium. |

Problem 3: Inconsistent Potency (IC50/EC50) Measurements

| Observation | Potential Cause | Investigation & Resolution |

|---|---|---|

| Significant variation in IC50/EC50 values between replicates or experiments. | Inaccurate compound stock solutions. | Carefully prepare and validate stock solution concentrations. Use high-quality DMSO and ensure complete solubilization. Standardize stock solution preparation protocols across the team [14]. |

| Assay component instability. | Ensure all assay components (enzymes, substrates, buffers) are fresh, prepared correctly, and handled consistently. Avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles of critical reagents. |

Problem 4: No Assay Window in a Z'-LYTE Assay

| Observation | Potential Cause | Investigation & Resolution |

|---|---|---|

| Minimal difference in the emission ratio between the 0% phosphorylation and 100% phosphorylation controls. | Problem with the development reaction. | Perform a control development reaction: for the "100% phosphopeptide control," do not add development reagent; for the "substrate," add a 10-fold higher concentration of development reagent. A proper development should show a ~10-fold ratio difference. If not, check development reagent dilution [14]. |

| Instrument setup problem. | Verify that the microplate reader is correctly configured for the fluorescence parameters (excitation/emission wavelengths) of the Z'-LYTE assay [14]. |

Key Experimental Data and Metrics

Table 1: Global Attrition Impact and Costs

| Metric | Value | Context / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Annual Global Employee Turnover Cost | $1 Trillion | Reported by Gallup in 2024 [15] |

| Cost to Replace an Employee | 50% - 200% of annual salary | Varies by role and seniority [15] |

| Average Global Attrition Rate | 15% - 20% | General average across industries [15] |

| Technology Sector Attrition Rate | 25% - 30% | Notably higher than the global average [15] |

Table 2: Assay Performance Metrics and Benchmarks

| Metric | Formula / Value | Interpretation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attrition Rate | (Number of employees who left / Average number of employees) × 100 |

Track monthly, quarterly, and annually to identify trends [15]. | ||

| Z'-Factor | `1 - [3*(SDhighcontrol + SDlowcontrol) / | Meanhighcontrol - Meanlowcontrol | ]` | A measure of assay robustness. >0.5 is suitable for screening [14]. |

| Emission Ratio (TR-FRET) | Acceptor Signal / Donor Signal (e.g., 520 nm/495 nm for Tb) |

Normalizes data, correcting for pipetting and reagent variability [14]. | ||

| Response Ratio | Emission Ratio / Avg. Emission Ratio at bottom of curve |

Normalizes titration curves; assay window always starts at 1.0 [14]. |

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Validating Microplate Reader Setup for TR-FRET

Purpose: To confirm the instrument is correctly configured before running valuable assay components.

- Acquire Control Reagents: Use TR-FRET control reagents, such as those from a commercial Terbium (Tb) or Europium (Eu) assay kit.

- Prepare Validation Plate: Prepare a plate according to the kit's instructions or application note. This typically includes wells for donor-only, acceptor-only, and a combined donor-acceptor mix.

- Configure Instrument: Set the instrument with the exact filters specified in the manufacturer's instrument compatibility guide for your dye and instrument model.

- Read Plate and Analyze: Measure the signals. A successful setup will show a strong TR-FRET signal (e.g., 520 nm for Tb) in the combined wells relative to the controls, confirming proper energy transfer [14].

Protocol 2: Troubleshooting a Failed Z'-LYTE Development Reaction

Purpose: To determine if a lack of assay window is due to the development reaction or an instrument issue.

- Prepare Control Reactions:

- 100% Phosphopeptide Control: Use the phosphopeptide control and add buffer instead of the development reagent. This should yield the lowest emission ratio.

- 0% Phosphopeptide Control (Substrate): Use the substrate peptide and add a 10-fold higher concentration of development reagent than recommended in the Certificate of Analysis (COA). This should yield the highest emission ratio.

- Incubate and Read: Incubate the reactions for 1 hour at room temperature and read the plate on the microplate reader.

- Interpret Results: A properly functioning development system should show approximately a 10-fold difference in the emission ratio between the two controls. If no difference is observed, the issue is likely with the development reagent preparation or the instrument setup [14].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents for Kinetic Profiling and Binding Assays

| Reagent / Solution | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| TR-FRET Donor (e.g., Tb, Eu) | The light-harvesting molecule in a TR-FRET assay; when excited, it transfers energy to a nearby acceptor molecule. |

| TR-FRET Acceptor | The molecule that receives energy from the donor and emits light at a longer, distinct wavelength, which is the measured signal. |

| LanthaScreen Eu Kinase Binding Assay | A specific assay format used to study compound binding to kinases, including inactive forms not suitable for activity assays [14]. |

| Z'-LYTE Assay Kit | A fluorescence-based, coupled-enzyme assay used to measure kinase activity and inhibition by monitoring a change in emission ratio. |

| Development Reagent (for Z'-LYTE) | The enzyme solution that selectively cleaves the non-phosphorylated peptide substrate, enabling the ratiometric measurement [14]. |

Experimental Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Diagram 1: From poor kinetics to R&D waste.

Diagram 2: Troubleshooting no assay window.

Measuring and Applying Kinetic Data in Sustainable Discovery Workflows

Troubleshooting Guides

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Troubleshooting

Q: My SPR baseline is unstable or drifting. What should I do? A: Baseline drift is often related to buffer or system instability [16].

- Ensure proper buffer degassing to eliminate bubbles that can cause signal fluctuations [16].

- Check for fluidic system leaks that may introduce air [16].

- Use fresh, filtered buffer to avoid chemical contamination of the sensor surface [16].

- Allow more stabilization time and ensure the instrument is in a stable environment with minimal temperature fluctuations and vibrations [16].

Q: I observe no signal change or a very weak signal upon analyte injection. A: This indicates a problem with the binding interaction or its detection [16].

- Verify analyte concentration is appropriate for the experiment and ligand density [16].

- Check ligand immobilization level, as it may be too low to generate a sufficient signal [16].

- Confirm ligand functionality and integrity after the immobilization process [16].

- Adjust flow rate or extend association time to improve binding detection [16].

Q: How can I resolve issues with high non-specific binding? A: Non-specific binding (NSB) makes actual binding appear stronger and can obscure results [17].

- Block the sensor surface with a suitable agent like BSA or ethanolamine before ligand immobilization [16].

- Supplement running buffer with additives such as surfactants, dextran, or polyethylene glycol (PEG) to reduce nonspecific interactions [17].

- Optimize the regeneration step to efficiently remove bound analyte between cycles [16].

- Consider alternative coupling methods, such as changing the sensor chip type or using a capture approach instead of direct covalent coupling [17].

Q: The sensor surface is not regenerating completely, leading to carryover. A: Incomplete regeneration affects data quality for subsequent analyte injections [16].

- Optimize regeneration conditions by testing different pH, ionic strength, and buffer compositions (e.g., 10 mM glycine pH 2, 10 mM NaOH, or 2 M NaCl) [16] [17].

- Increase regeneration flow rate or time to enhance removal of bound analyte [16].

- Add 10% glycerol to the regeneration solution can help maintain target stability during harsh regeneration conditions [17].

TR-FRET Assay Troubleshooting

Q: My TR-FRET assay has a low signal-to-background ratio. A: A poor signal-to-background ratio limits assay sensitivity and reliability.

- Verify reagent concentrations and incubation times. Ensure the donor and acceptor probes are used at optimal concentrations and that the assay has been incubated for a sufficient duration [18].

- Check for signal quenching. Library compounds or components in the biological sample can quench the TR-FRET signal. Review the composition of your assay mixture [18].

- Confirm instrument settings. Ensure the microplate reader is configured with the correct filters, the light source is functioning, and the time-delayed detection parameters (time delay and measurement window) are set appropriately for your specific TR-FRET kit [18].

Q: I am observing high well-to-well variability in my TR-FRET data. A: High variability compromises data consistency.

- Employ ratiometric measurement. A key advantage of TR-FRET is that the ratio of the acceptor emission over the donor emission normalizes the signal, correcting for well-to-well variability, pipetting errors, and absorbance or quenching effects from the medium [18].

- Ensure homogeneous reagent mixing. Gently but thoroughly mix the assay components without creating bubbles.

- Use fresh reagents. Prepare new buffer solutions and check that fluorescent probes have not degraded.

Live-Cell Binding Assay Troubleshooting

Q: I get a weak or no signal in my live-cell NanoBRET binding assay. A: This can be due to issues with the probe, cells, or detection [19].

- Confirm fluorescent ligand affinity. Ensure the chosen fluorescent probe has high affinity for your target receptor at the physiological temperature used for the assay [19].

- Validate receptor expression and functionality. Check that the cells are healthy and express the Nanoluc-tagged receptor at sufficient levels [19].

- Optimize the concentration of the fluorescent probe. Titrate the probe to determine the optimal concentration that provides a robust signal without excessive background [19].

- Protect samples from light throughout the experiment to prevent photobleaching of the fluorophore [20].

Q: There is high background fluorescence in my live-cell experiment. A: High background can mask the specific signal [20] [21].

- Use a cell viability dye to distinguish signals from live cells versus dead cells, which often exhibit elevated non-specific binding [20].

- Account for autofluorescence. Run unstained control cells to determine the level of cellular autofluorescence, which is particularly common in paraffin-embedded sections [21].

- Include Fc receptor blocking. If using antibody-based detection, add an Fc receptor blocking reagent to prevent non-specific antibody binding [20].

- Wash cells thoroughly after staining to remove unbound dye or probe [21].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: Within the context of waste minimization, when should I choose a TR-FRET assay over SPR? A: TR-FRET is a homogeneous "add-and-read" assay, requiring no washing or separation steps, minimizing reagent consumption and plastic waste from plates and tips [18]. This makes it ideal for high-throughput screening (HTS) campaigns where thousands of compounds are tested [18] [22]. SPR, while label-free and providing rich kinetic data, involves continuous buffer flow and sensor chips that require regeneration. For focused, low-throughput kinetic studies on purified proteins, SPR provides unparalleled detail, but for large-scale primary screening, TR-FRET is more efficient and less wasteful [23] [22].

Q: Can I determine binding kinetics (kon/koff) with TR-FRET, or is SPR always required? A: TR-FRET can be used to determine binding kinetics, challenging the notion that it is the sole domain of SPR. By using the Motulsky-Mahan model for competition binding, the association and dissociation rate constants (kon and koff) of unlabelled ligands can be calculated by measuring the association kinetics of a labelled tracer in their presence [19] [24]. This allows for higher-throughput kinetic screening in a more physiologically relevant live-cell environment, without the need for protein purification [22] [19].

Q: What is the significance of a ligand's residence time (RT), and how can I measure it without radioligands? A: Residence Time (RT = 1/koff) is increasingly recognized as a critical parameter that can better predict a drug's in vivo efficacy and duration of action than affinity (Kd) alone [19]. Fluorescence-based live-cell assays, such as NanoBRET and TR-FRET binding assays, now enable the direct measurement of probe dissociation and the calculation of residence times for unlabelled compounds at full-length receptors in live cells at physiological temperatures, overcoming the limitations of traditional radioligand binding assays that sometimes require low temperatures [19] [24].

Quantitative Data and Reagent Tables

TR-FRET Kit Spectral Properties

Table: Commercially available TR-FRET kits and their spectral profiles. Adapted from [18].

| Kit Name | Donor | Donor Excitation (nm) | Donor Emission (nm) | Acceptor | Acceptor Emission (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LANCE / LanthaScreen Eu | Europium (Chelate) | 320 | 620 | ULight / AlexaFluor647 | 665 |

| LanthaScreen Tb | Terbium (Chelate) | 340 | 490 | Fluorescein / GFP | 520 |

| HTRF Red (Eu/Tb) | Europium/Terbium (Cryptate) | 320 / 340 | 620 | XL665 / d2 | 665 |

| HTRF Green (Tb) | Terbium (Cryptate) | 340 | 620 | Fluorescein / GFP | 520 |

| Transcreener TR-FRET | Terbium (Chelate) | 340 | 620 | HiLyte647 | 665 |

| THUNDER | Europium (Chelate) | 320 | 620 | Far-red dye | 665 |

Representative Kinetic Data from TR-FRET Binding Assays

Table: Sample kinetic parameters for ligands binding to cannabinoid receptors obtained via a TR-FRET assay [24].

| Ligand | Target Receptor | kon (1/Ms) | koff (1/s) | Residence Time (RT) | Affinity (Kd) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HU308 | CB1R | Slowest | - | Longest | High |

| Rimonabant | CB1R | Fastest (x1000 vs HU308) | - | - | - |

| D77 Tracer | CB1R (truncated) | - | Rapid | Short | Nanomolar |

| D77 Tracer | CB2R (full-length) | - | Rapid | Short | Nanomolar |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table: Essential reagents and their functions in SPR, TR-FRET, and live-cell assays.

| Reagent / Material | Function | Application |

|---|---|---|

| Sensor Chips (e.g., CM5, NTA) | Solid support with specialized surface chemistry for immobilizing the ligand (target). | SPR |

| Regeneration Buffers (e.g., Glycine pH 2.0, NaOH) | Solutions that break ligand-analyte bonds without damaging the immobilized ligand, allowing chip re-use. | SPR |

| Lanthanide Donors (e.g., Eu/Tb Cryptates) | Long-lived fluorescent donors that enable time-resolved detection, reducing background noise. | TR-FRET |

| Acceptor Fluorophores (e.g., XL665, d2) | Emit light upon FRET from the donor, indicating a binding event. | TR-FRET |

| Nanoluciferase (Nluc)-Tagged Receptor | Genetically engineered receptor that produces a bright bioluminescent signal, acting as the BRET donor in live cells. | Live-Cell NanoBRET |

| Fluorescent Tracer Ligands | High-affinity, cell-permeant receptor ligands conjugated to a fluorophore (BRET acceptor). | Live-Cell NanoBRET |

| Cell Viability Dyes (e.g., DAPI, 7-AAD) | Distinguish live from dead cells to reduce false positives from non-specific binding to dead cells. | Live-Cell Assays, Flow Cytometry |

| Fc Receptor Blocking Reagent | Blocks non-specific binding of antibodies to Fc receptors on immune cells. | Live-Cell Assays, Flow Cytometry, IF/IHC |

| Puliginurad | Puliginurad|URAT1 Inhibitor|CAS 2013582-27-7 | |

| D-Arabinose-d5 | D-Arabinose-d5, MF:C5H10O5, MW:155.16 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Experimental Workflows and Signaling Pathways

SPR Kinetic Analysis Workflow

TR-FRET Binding Assay Principle

Live-Cell NanoBRET Kinetic Assay

Kinetic models are crucial for understanding and predicting the dynamic behavior of complex biochemical systems, from cellular metabolism to drug-target interactions. Traditional methods for developing these models face significant challenges, particularly in determining the kinetic parameters that govern cellular physiology. The process is often slow, computationally intensive, and limited by sparse experimental data. Generative artificial intelligence (AI) presents a transformative approach to these challenges, enabling researchers to efficiently parameterize kinetic models, predict state transitions, and characterize intracellular metabolic states with unprecedented accuracy and speed. These AI-enabled methods not only accelerate research but also contribute to waste minimization by drastically reducing the need for extensive trial-and-error experimentation, thus conserving valuable reagents, laboratory supplies, and researcher time. By integrating diverse omics data and physicochemical constraints, generative models provide a powerful framework for smarter screening of metabolic states and drug candidates, aligning kinetic optimization research with sustainable laboratory practices.

Key Generative AI Frameworks and Their Applications

Recent research has produced several specialized generative AI frameworks designed to overcome specific challenges in kinetic modeling. The table below summarizes three prominent frameworks, their core methodologies, and primary applications in biochemical research.

Table 1: Key Generative AI Frameworks for Kinetic Prediction

| Framework Name | Core Methodology | Primary Application | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| RENAISSANCE [25] | Generative machine learning using neural networks optimized with Natural Evolution Strategies (NES) | Parameterizing large-scale kinetic models of metabolism; characterizing intracellular metabolic states | Reduces extensive computation time; requires no training data from traditional kinetic modeling; seamlessly integrates diverse omics data |

| DeePMO [26] | Iterative sampling-learning-inference strategy using hybrid Deep Neural Networks (DNNs) | Optimizing high-dimensional parameters in chemical kinetic models | Handles both sequential and non-sequential data; validated across multiple fuel models with parameters ranging from tens to hundreds |

| GPT-based Approach [27] | Generative Pre-trained Transformer adapted to learn from molecular dynamics trajectories | Predicting kinetic sequences of physicochemical states in biomolecules | Predicts state-to-state transition kinetics much quicker than traditional MD simulations; captures long-range correlations via self-attention mechanism |

Experimental Validation and Performance

These frameworks have demonstrated significant success in experimental settings. The RENAISSANCE framework was successfully applied to construct kinetic models of Escherichia coli metabolism, consisting of 113 nonlinear ordinary differential equations parameterized by 502 kinetic parameters. The generated models showed robust performance, with 100% of perturbed models returning to reference steady state for biomass and key metabolites within experimentally observed timescales [25]. Similarly, the GPT-based approach accurately predicted kinetically correct sequences of states for diverse biomolecules, achieving statistical precision comparable to molecular dynamics simulations but at a much accelerated pace [27].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Implementing AI-enabled kinetic prediction requires both computational tools and experimental components. The following table details key resources mentioned in the research, with an emphasis on how proper computational screening minimizes physical reagent waste.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for AI-Enabled Kinetic Prediction

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function in Kinetic Prediction | Waste Minimization Benefit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Frameworks | RENAISSANCE, DeePMO, GPT-based models | Parameterizing kinetic models, optimizing parameters, predicting state transitions | Drastically reduces need for physical experiments through in silico prediction and screening |

| Data Types | Metabolomics, fluxomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, thermodynamic data [25] | Providing constraints and training data for model generation and validation | Enables maximal information extraction from existing datasets, reducing redundant experimentation |

| Biological Systems | E. coli metabolic networks, cancer-related compounds, protein targets (MEK, BACE1) [25] [28] | Serving as validation systems for AI prediction methods | Virtual screening pinpoints most promising targets, minimizing use of valuable biological reagents |

| Validation Metrics | Dominant time constants, eigenvalue analysis (λmax), perturbation response, ignition delay time, laminar flame speed [25] [26] | Evaluating accuracy and biological relevance of generated models | Computational validation precedes physical testing, ensuring only high-quality candidates move forward |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol: Parameterizing Kinetic Models with RENAISSANCE

This protocol outlines the procedure for using the RENAISSANCE framework to generate large-scale kinetic models, adapted from its application in E. coli metabolism studies [25].

Input Requirements:

- Steady-state profile of metabolite concentrations and metabolic fluxes

- Structural properties of the metabolic network (stoichiometry, regulatory structure, rate laws)

- Available omics data (metabolomics, fluxomics, thermodynamics, proteomics, transcriptomics)

Procedure:

- Initialization: Initialize a population of feed-forward neural networks (generators) with random weights.

- Parameter Generation: Each generator takes multivariate Gaussian noise as input and produces a batch of kinetic parameters consistent with the network structure and integrated data.

- Model Parameterization: Use generated parameter sets to parameterize the kinetic model.

- Dynamic Evaluation: Compute eigenvalues of the Jacobian and corresponding dominant time constants for each parameterized model.

- Reward Assignment: Assign rewards to generators based on whether generated models produce dynamic responses matching experimental observations (valid models have λmax < -2.5, corresponding to a doubling time of 134 minutes in E. coli).

- Weight Update: Update generator weights using Natural Evolution Strategies, weighted by normalized rewards.

- Iteration: Repeat steps 2-6 for 50 generations or until achieving >90% incidence of valid models.

Validation:

- Perturb steady-state metabolite concentrations up to ±50% and verify system returns to steady state within experimentally observed timescales.

- Test generated models in nonlinear dynamic bioreactor simulations mimicking real-world experimental conditions.

Protocol: Predicting Kinetic Sequences with GPT

This protocol describes the procedure for adapting Generative Pre-trained Transformers to predict state-to-state transition kinetics in physicochemical systems, based on published research [27].

Input Requirements:

- Sequences of time-discretized states from Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation trajectories

- Vocabulary corpus of states analogous to natural language processing training data

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Preprocess MD simulation trajectories into sequences of discrete states, creating a "vocabulary" of physicochemical states.

- Model Architecture: Implement GPT architecture with self-attention mechanisms to capture long-range correlations within trajectory data.

- Training: Train model on state sequences to learn complex syntactic and semantic relationships within the trajectory data.

- Prediction: Use trained model to generate kinetically accurate sequences of states for novel biomolecular systems.

- Validation: Compare predicted state transitions with those obtained from traditional MD simulations using statistical precision metrics.

Applications:

- Predicting time evolution of biologically relevant physicochemical systems

- Forecasting behavior of out-of-equilibrium active systems that do not maintain detailed balance

- Accelerating molecular dynamics simulations while maintaining kinetic accuracy

Technical Support: Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What are the most common data quality issues that affect AI-enabled kinetic prediction models? A: The most frequent issues include sparse or inconsistent experimental data, inadequate coverage of the parameter space in training data, and mismatches between data sources. As noted in drug discovery research, "the output of a model is only as good as the input of the data" [29]. Ensure data undergoes rigorous preprocessing, normalization, and quality control before model training. For metabolic models, integrate multiple omics datasets (metabolomics, fluxomics, proteomics) to provide sufficient constraints [25].

Q: How can we validate that AI-generated kinetic models are biologically relevant rather than computational artifacts? A: Implement multiple validation strategies: (1) Perturbation testing - ensure the system returns to steady state after moderate perturbations [25]; (2) Timescale validation - verify dominant time constants match experimental observations (e.g., doubling time); (3) Comparative analysis - check predictions against held-out experimental data; (4) Robustness testing - evaluate model behavior under varying conditions beyond training parameters.

Q: What strategies can address the "black box" nature of complex AI models in kinetic prediction? A: Incorporate explainable AI (XAI) techniques such as attention mechanism analysis (for transformer models), feature importance scoring, and sensitivity analysis. Research shows that analyzing the self-attention mechanism in GPT models can reveal how the model captures long-range correlations necessary for accurate state-to-state transition predictions [27]. Additionally, use model architectures that allow integration of known physical constraints to ground predictions in established principles.

Q: How does AI-enabled kinetic prediction specifically contribute to waste minimization? A: It reduces waste through multiple mechanisms: (1) Virtual screening eliminates unnecessary physical experiments; (2) More accurate predictions reduce failed experiments; (3) Optimized experimental designs require fewer reagents; (4) Reduced computational waste compared to traditional parameter scanning methods. These align with broader waste minimization strategies that reduce raw material loss through process inefficiencies [30].

Q: What computational resources are typically required for these approaches? A: Requirements vary by framework: RENAISSANCE was run for 50 evolution generations with population-based generators [25]; DeePMO uses iterative sampling that benefits from parallel processing [26]; GPT-based approaches require significant GPU memory for training but efficient inference [27]. Starting with smaller proof-of-concept models before scaling is recommended.

Troubleshooting Common Issues

Problem: Poor model convergence or inability to generate valid kinetic parameters.

- Potential Cause 1: Inadequate constraints from experimental data.

- Solution: Integrate additional omics data or thermodynamic constraints to reduce parameter uncertainty [25].

- Potential Cause 2: Inappropriate network architecture or hyperparameters.

- Solution: Perform systematic hyperparameter optimization; RENAISSANCE achieved best performance with a three-layer generator neural network [25].

- Potential Cause 3: Insufficient exploration of parameter space.

- Solution: Increase population size in evolutionary algorithms or use enhanced sampling techniques like the jump methods employed in swarm-based optimization [31].

Problem: Generated models fail validation tests or show unbiological behavior.

- Potential Cause 1: Overfitting to training data.

- Solution: Implement regularization techniques, cross-validation, and ensure diverse training data covering multiple physiological conditions.

- Potential Cause 2: Missing key regulatory mechanisms in model structure.

- Solution: Revisit model structure and incorporate additional regulatory constraints based on domain knowledge.

- Potential Cause 3: Numerical instability in solving differential equations.

- Solution: Check integration methods, step sizes, and parameter scaling; use specialized solvers for stiff systems.

Problem: Discrepancy between AI predictions and experimental observations.

- Potential Cause 1: Domain shift between training data and application context.

- Solution: Incorporate transfer learning techniques to adapt models to new conditions, or use frameworks like DeePMO that employ iterative sampling-learning-inference strategies [26].

- Potential Cause 2: Insufficient model capacity to capture system complexity.

- Solution: Increase model complexity gradually while monitoring for overfitting; consider hybrid approaches that combine mechanistic and AI components.

Workflow Visualization

AI-Enabled Kinetic Prediction Workflow

This workflow illustrates the iterative process of implementing AI-enabled kinetic prediction, highlighting how computational screening reduces experimental waste.

AI Framework Applications and Waste Reduction Benefits

This diagram maps three AI frameworks to their primary applications and corresponding waste minimization benefits, demonstrating how specialized approaches target different aspects of kinetic prediction while promoting sustainable research practices.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Common Experimental Issues and Solutions

FAQ: Why is my measured residence time inconsistent between assay formats?

- Potential Cause: The kinetic mechanism (e.g., one-step vs. two-step binding) can be differentially affected by assay conditions such as temperature, pH, or detergent concentration [2].

- Solution: Confirm the binding mechanism first. For a two-step induced-fit model, ensure your assay can capture the slow conformational change. Use complementary techniques (e.g., surface plasmon resonance and stopped-flow spectrometry) to validate kinetics [2].

FAQ: My compound has high thermodynamic affinity but shows poor cellular efficacy. What could be wrong?

- Potential Cause: This may be due to a fast off-rate (short residence time), making target occupancy sensitive to changes in compound concentration in the cellular environment [2].

- Solution: Focus on optimizing the structure-kinetic relationship (SKR). Introduce chemical groups that stabilize the transition state for dissociation, for example, by forming specific interactions with flexible loops or protein backbone atoms [2].

FAQ: How can I rationally design for a slower off-rate?

- Potential Cause: A focus solely on ground-state stabilization (as seen in crystal structures) may not affect the transition state energy barrier for dissociation [2].

- Solution: Utilize molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to model the dissociation pathway. Identify and engineer interactions that are strengthened in the transition state, such as those with residues in a gating loop or a specific protein conformation [2].

Quantitative Data on Residence Times and Mechanisms

Table 1: Representative Residence Times and Associated Kinetic Mechanisms

| Target | Compound | Residence Time | Mechanism for Prolonged Residence Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| S. aureus FabI [2] | Alkyl diphenyl ether PT119 [2] | 12.5 hr (20°C) [2] | Ordering of the substrate binding loop (SBL) [2] |

| Purine nucleoside phosphorylase [2] | DADMe-immucillin-H [2] | 12 min (37°C) [2] | Gating mechanism involving rotation of Val260 [2] |

| Mutant IDH2/R140Q [2] | AGI-6780 [2] | 120 min [2] | Loop motion associated with an allosteric binding site [2] |

| RIP1 kinase [2] | Benzoxazepine 22 [2] | 5 hr [2] | Type II/III binding; increased cLogP reduced koff [2] |

| Bruton's Tyrosine Kinase (Btk) [2] | Pyrazolopyrimidine 9 [2] | 167 hr [2] | Reversible covalent binding; steric hindrance of α-proton abstraction [2] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining Residence Time using a Jump-Dilution Assay This method is ideal for characterizing slow-binding and covalent inhibitors [2].

- Form the Complex: Pre-incubate the target protein with a saturating concentration of the inhibitor for a period sufficient to reach equilibrium.

- Dilute: Rapidly dilute the pre-formed complex by a large factor (e.g., 100-fold) into a buffer containing a high concentration of substrate or a competing ligand. This effectively prevents re-association of the free inhibitor.

- Monitor Recovery: Continuously monitor the recovery of enzymatic activity over time.

- Data Analysis: Fit the progress curve to a first-order equation to determine the observed rate constant (kobs). The residence time (tR) is calculated as the reciprocal of this dissociation rate constant: tR = 1 / koff = 1 / k_obs.

Protocol 2: Investigating a Two-Step Induced-Fit Mechanism via Stopped-Flow Fluorescence This protocol is used when a rapid initial binding event is followed by a slower conformational change [2].

- Preparation: Equilibrate the protein and inhibitor in separate syringes at the same temperature.

- Rapid Mixing: Rapidly mix the two solutions to initiate the binding reaction.

- Signal Acquisition: Use a fluorescence signal (e.g., intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence or a fluorescently labeled protein) to monitor the binding reaction on a millisecond-to-minute timescale.

- Kinetic Modeling: Fit the resulting biphasic trace to a two-step kinetic model (e.g., E + I ⇌ EI → E-I*) to extract the association (kon) and dissociation (koff) rate constants for both steps.

Visualization of Key Concepts

Induced-Fit Binding Mechanism

Drug-Target Binding Energy Landscape

Conformational Selection and Gating

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for SKR Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in SKR Studies |

|---|---|

| Recombinant Target Protein | Essential for in vitro binding assays. Purity and stability are critical for obtaining reliable kinetic data [2]. |

| Slow-Binding Inhibitors | Chemical probes used to study structure-kinetic relationships. Examples include diphenyl ethers for FabI or type II inhibitors for kinases [2]. |

| Crystallization Screens | Used to obtain high-resolution structures of drug-target complexes, revealing interactions responsible for ground-state stabilization [2]. |

| Molecular Dynamics Software | Computational tool for simulating the binding and unbinding pathways, providing atomistic insight into transition states and dissociation energy barriers [2]. |

| Biosensor Chips (SPR) | Solid-phase supports for surface plasmon resonance analysis, a key technology for directly measuring association and dissociation rate constants in real-time [2]. |

| Prdx1-IN-1 | Prdx1-IN-1, MF:C46H55N3O4, MW:713.9 g/mol |

| Alk2-IN-5 | ALK2-IN-5|ALK2 Inhibitor |

The integration of solvent-free and mechanochemical synthesis represents a frontier in green chemistry, directly supporting strategic waste minimization and kinetic optimization in research. These methodologies eliminate or drastically reduce the use of hazardous solvents, addressing a primary source of waste in chemical manufacturing. By leveraging mechanical force to drive reactions, mechanochemistry offers unique pathways for controlling reaction kinetics and enhancing efficiency, providing researchers with powerful tools to develop sustainable synthetic protocols. This technical support center is designed to equip scientists with practical knowledge to implement these techniques, troubleshoot common issues, and optimize their experimental workflows within a green chemistry framework.

Core Principles & FAQs

Fundamental Concepts

What are the fundamental green chemistry advantages of these methods?

Solvent-free and mechanochemical reactions align with multiple principles of green chemistry. Most notably, they prevent waste at the source by eliminating the need for large solvent volumes, which often account for the majority of mass in a traditional chemical process [32]. This leads to a dramatically improved E-Factor (the ratio of waste to product) [32]. Furthermore, they enhance atom economy by maximizing the incorporation of starting materials into the final product and improve energy efficiency as they typically proceed at or near ambient temperature without requiring energy-intensive solvent heating or cooling [33] [32].

What types of materials can be synthesized using these techniques?

These versatile methods have been successfully applied to create a wide array of advanced materials:

- Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) like ZIF-8, HKUST-1, and UiO-66 [34].

- Covalent Organic Frameworks (COFs) for enzyme encapsulation [35].

- Noble metal nanoparticles (e.g., Au, Ag) for catalytic applications [36].

- Complex ceramic oxides with ferroelectric, magnetic, or catalytic properties [34].

- Pharmaceutical intermediates and Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) [32].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

FAQ: My mechanochemical reaction shows inconsistent results or low yield. What could be wrong?

Inconsistent outcomes often stem from variable energy input or contamination. Ensure your milling equipment is calibrated and that the milling time, frequency, and ball-to-powder mass ratio are kept constant between experiments [34]. Cross-contamination from previous runs can also be a factor; implement a rigorous cleaning procedure between experiments using appropriate solvents.

FAQ: I am encountering problems with nanoparticle agglomeration during solvent-free synthesis. How can I improve dispersion?

Agglomeration is a common challenge. Consider these approaches:

- Introduce a capping or stabilizing agent during the milling process to functionalize the nanoparticle surfaces and prevent aggregation [36].

- Employ Liquid-Assisted Grinding (LAG), where a catalytic quantity of solvent is added to the reaction mixture. This can enhance molecular mobility and improve product dispersion without significantly compromising the green credentials of the process [34].

- Optimize the milling parameters. Excessive impact energy can sometimes promote cold-welding and agglomeration, while insufficient energy may lead to incomplete reactions [34] [36].

FAQ: How can I effectively monitor the progress of a solvent-free mechanochemical reaction?

Real-time reaction monitoring is an active area of research. Currently, the most practical method is to halt the milling process at various intervals and analyze small aliquots of the reaction mixture using standard characterization techniques such as:

- X-ray diffraction (XRD) to monitor crystalline phase formation.

- Infrared (IR) or Raman spectroscopy to track the disappearance of reactant functional groups and the appearance of product signatures [34].

Table 1: Common Problems and Solutions in Mechanochemical Synthesis

| Problem Area | Specific Symptom | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reaction Efficiency | Low conversion/yield | Incorrect ball-to-powder ratio, insufficient milling time, low energy input | Optimize and standardize milling parameters (time, frequency, mass ratio) [34] |

| Product Quality | Unwanted by-products or impurities | Cross-contamination, reagent degradation, uncontrolled local heating | Implement rigorous equipment cleaning; verify reagent purity and stability [34] |

| Material Properties | Excessive agglomeration of particles | Lack of stabilizing agents, high surface energy, over-milling | Introduce capping agents; use Liquid-Assisted Grinding (LAG); optimize milling energy [34] [36] |

| Process Control | Poor reproducibility between batches | Inconsistent milling conditions, atmospheric moisture/temperature fluctuations | Control laboratory environment; calibrate equipment regularly; document all parameters meticulously |

Experimental Protocols & Data

Detailed Methodology: Mechanochemical Synthesis of Enzyme@COF Biocomposites

This protocol, adapted from published procedures, details the steps for encapsulating enzymes into Covalent Organic Frameworks (COFs) using a mechanochemical approach, a key technique for stabilizing biocatalysts [35].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Precursor Preparation: Weigh the organic linker precursors (e.g., aldehyde and amine monomers) and the enzyme in a defined molar ratio. The solid reagents should be finely ground and mixed manually with a mortar and pestle to ensure initial homogeneity.

- Mechanochemical Synthesis: Transfer the mixed powder into a milling jar (e.g., of a ball mill). Use the appropriate number and size of milling balls (typically zirconia) to achieve the desired mechanical energy input. Seal the jar and initiate milling. The process is typically performed at room temperature for a predetermined duration (e.g., 30-90 minutes).

- Product Collection: After milling, carefully open the jar. The resulting solid powder is the crude enzyme@COF biocomposite.

- Washing and Purification: Gently wash the solid product with a mild buffer solution to remove any unreacted precursors or enzyme that is not encapsulated. This step preserves the enzyme activity within the COF matrix.