Beyond the Balance Sheet: AI, Metrics, and Modern Methods for Maximizing Reaction Mass Efficiency

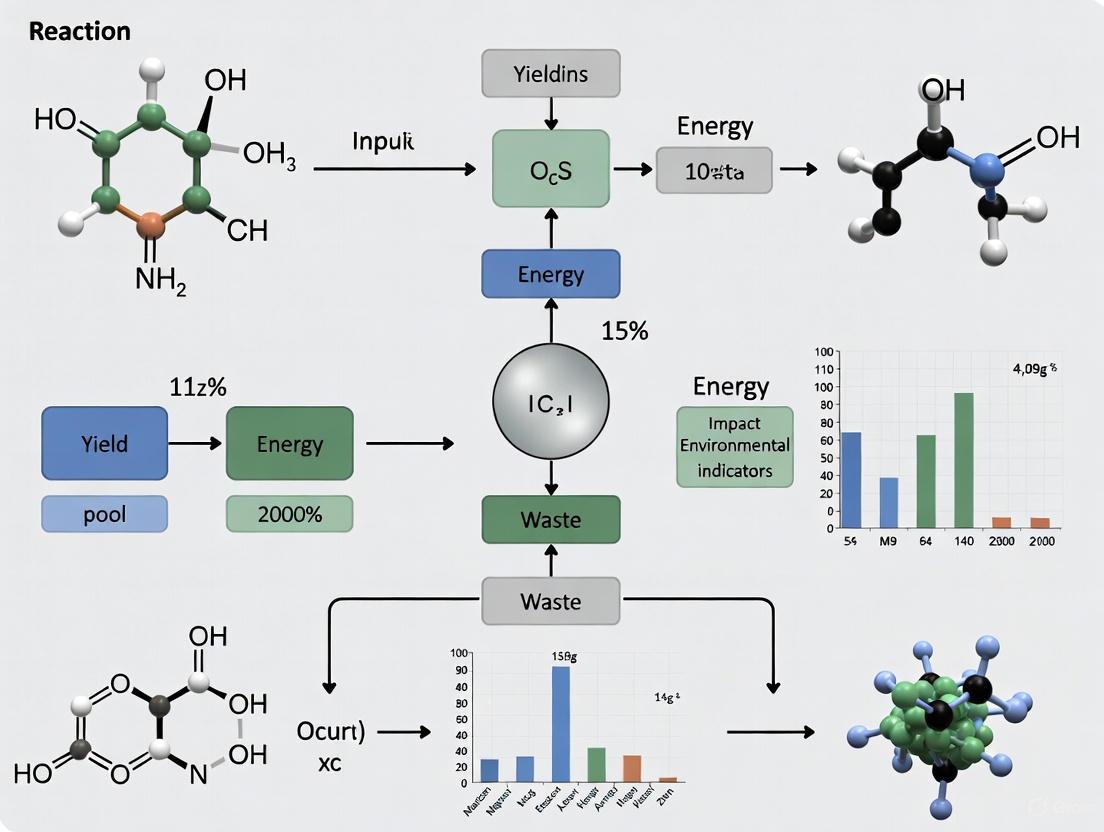

Improving Reaction Mass Efficiency (RME) is a critical objective in pharmaceutical development, directly impacting sustainability, cost, and process robustness.

Beyond the Balance Sheet: AI, Metrics, and Modern Methods for Maximizing Reaction Mass Efficiency

Abstract

Improving Reaction Mass Efficiency (RME) is a critical objective in pharmaceutical development, directly impacting sustainability, cost, and process robustness. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists, covering the foundational principles of green chemistry metrics like Process Mass Intensity (PMI) and their correlation to environmental impact. It explores cutting-edge methodological advances, including generative AI for reaction prediction and machine learning-driven high-throughput experimentation (HTE) for optimization. The content also delivers practical troubleshooting frameworks for common experimental pitfalls and outlines rigorous validation protocols using modern analytical techniques such as UHPLC-MS/MS to ensure accurate efficiency measurements. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with the latest technological applications, this article serves as a strategic roadmap for advancing reaction efficiency in drug development.

RME and Green Chemistry: Defining Metrics and Environmental Impact

Understanding Process Mass Intensity (PMI) and Its Role in Green Chemistry

FAQs on Process Mass Intensity (PMI)

What is Process Mass Intensity (PMI) and why is it important? Process Mass Intensity (PMI) is a key green chemistry metric used to measure the efficiency of a chemical process. It is defined as the total mass of materials used to produce a unit mass of the desired product [1]. PMI is calculated as the ratio of the total mass of all inputs (reactants, reagents, solvents, catalysts) to the mass of the final product [2]. The pharmaceutical industry has adopted PMI as a primary metric to benchmark environmental performance, drive sustainable practices, and reduce the environmental footprint of drug development and manufacturing [3] [4]. A lower PMI indicates a more efficient process with less waste generation.

How do I calculate PMI for a chemical reaction? The standard formula for PMI is: PMI = (Total Mass of All Input Materials) / (Mass of Product) [2] For accurate calculation:

- Account for all materials entering the process: reactants, reagents, solvents (reaction and purification), and catalysts [1].

- Use the actual masses from your experimental data.

- Ensure the product mass is the final, isolated mass of the desired compound. The ACS GCI Pharmaceutical Roundtable provides a PMI Calculator to facilitate this calculation [3].

What are the limitations of using PMI as a standalone metric? While PMI is a valuable mass-based efficiency metric, it has limitations:

- System Boundaries: Traditional (gate-to-gate) PMI does not account for the environmental impact of producing the input materials themselves [5]. A cradle-to-gate perspective that includes upstream production is more comprehensive.

- No Hazard or Environmental Impact Assessment: PMI measures mass, but does not differentiate between benign and hazardous materials [5] [6]. A process with a low PMI that uses highly toxic solvents is less "green" than one with a slightly higher PMI that uses water.

- Potential for Misinterpretation: Without considering yield, concentration, and molecular weight of reactants, PMI can sometimes be misleading when comparing different methodologies [6].

How does PMI differ from Atom Economy and E-Factor? PMI, Atom Economy (AE), and E-Factor are related but distinct metrics. The table below summarizes the key differences:

| Metric | Formula | Focus | Key Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Process Mass Intensity (PMI) | Total Mass Input / Mass Product [2] | Total material input efficiency | Includes all materials (solvents, reagents, etc.) used in the entire process. |

| Atom Economy (AE) | (MW of Product / Sum of MW of Reactants) x 100% [7] | Atom efficiency of the stoichiometric reaction | A theoretical calculation based only on molecular weights of stoichiometric reactants; ignores yield, solvents, and other process materials. |

| E-Factor | Total Mass Waste / Mass Product [7] | Total waste generated | Focuses exclusively on waste output. PMI = E-Factor + 1 [7]. |

What is considered a "good" or "bad" PMI value? PMI values are highly context-dependent and vary by industry and process complexity. The following table provides a general reference for different sectors, showing the potential for improvement:

| Product Category | Typical PMI Range | Optimized PMI Range | Material Savings Potential |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmaceutical Active Ingredient (API) | 100 - 1000 | 50 - 200 | Up to 90% [2] |

| Fine Chemical Synthesis | 50 - 200 | 10 - 50 | Up to 80% [2] |

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: My process has a high PMI. How can I improve it?

A high PMI indicates low resource efficiency. Follow this diagnostic workflow to identify areas for improvement:

Recommended Actions:

Optimize Solvent Use:

- Action: Reduce solvent volumes, switch to greener solvents (e.g., water, ethanol, 2-methyl-THF), or implement solvent recovery and recycling systems [3] [2].

- Protocol: Perform a solvent selection guide assessment. Measure and minimize solvent use in reaction and workup steps. Set up a distillation apparatus to recover and reuse solvents from mother liquors.

Optimize Stoichiometry and Catalysis:

- Action: Reduce excess reactants and employ catalytic instead of stoichiometric reagents [6].

- Protocol: Run a design of experiments (DoE) to find the optimal equivalence of reagents. Screen for catalytic alternatives to stoichiometric oxidants/reductants.

Improve Workup and Purification:

- Action: Replace chromatography with crystallization or distillation where possible [2].

- Protocol: Develop a crystallization protocol by screening antisolvents and optimizing cooling curves. For distillable products, use fractional distillation to improve purity and yield.

Issue: I'm getting inconsistent PMI values when comparing different synthetic routes.

Inconsistent PMI calculations often stem from undefined or varying system boundaries.

Solution: Standardize the Calculation Framework

Define Clear System Boundaries:

- Action: Decide whether you are calculating a gate-to-gate PMI (only materials within your direct process) or a cradle-to-gate Value-Chain Mass Intensity (VCMI) (which includes upstream production of inputs) [5]. State your chosen boundary clearly.

- Protocol: For gate-to-gate, list all materials added from the first reaction step to the final isolation. For VCMI, use life cycle inventory databases to estimate the total mass of resources needed to produce your input materials.

Use a Standardized Tool:

- Action: Utilize the ACS GCI PMI Calculator or Convergent PMI Calculator to ensure all calculations follow the same methodology [3].

- Protocol: Input all material masses for each step into the calculator. For convergent syntheses, use the convergent tool to accurately account for the mass contributions from different branches.

Report All Parameters:

- Action: When reporting PMI, always accompany it with the reaction yield, concentration, and main solvent used. This provides context and prevents misinterpretation [6].

- Protocol: Present data in a standardized format: PMI = X (Yield = Y%, Concentration = Z g/mL, Solvent = ABC).

Issue: My PMI is low, but the environmental impact of my process is still high.

This is a common pitfall where mass efficiency is conflated with overall environmental sustainability.

Solution: Augment PMI with Additional Metrics

Integrate Hazard Assessment:

- Action: Use PMI in conjunction with metrics that assess environmental and human health toxicity.

- Protocol: Employ tools like the Green Chemistry Institute's iGAL calculator, which incorporates waste and hazard considerations into a single score [1]. Classify all waste according to its hazard profile (e.g., heavy metal content, mutagenicity).

Conduct a Streamlined Life Cycle Assessment (LCA):

- Action: Perform a simplified LCA to evaluate impacts like global warming potential, water use, and energy consumption, which are not captured by PMI alone [5] [8].

- Protocol: Use LCA software (e.g., openLCA) with streamlined databases to model your process. Focus on key impact categories such as climate change and water scarcity to identify hotspots beyond mass.

Calculate a Holistic Set of Green Metrics:

- Action: Create a metrics dashboard that includes PMI, E-Factor, Atom Economy, and a Solvent Environmental Assessment Tool score.

- Protocol: Calculate all metrics for your process. Present them together in a radial pentagon diagram to visually compare the performance of different routes across multiple dimensions [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential material classes used in chemical synthesis and their role in the context of PMI optimization.

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Synthesis | Consideration for PMI & Greenness |

|---|---|---|

| Catalysts (e.g., Pd, Ni, Organocatalysts) | Lowers activation energy, enables alternative routes. | PMI Impact: Allows for lower reagent stoichiometry and fewer steps. Key is recovery and recycling to prevent heavy metal waste and high VCMI [9]. |

| Solvents (e.g., Water, Ethanol, 2-MeTHF, CPME) | Medium for reaction, separation, purification. | Largest contributor to PMI in many processes [3]. Prioritize safe, renewable, and recyclable solvents. Use solvent selection guides. |

| Stoichiometric Reagents & Reducing Agents | Drives reaction equilibrium, functional group interconversion. | A major source of waste. Seek catalytic alternatives (e.g., catalytic hydrogenation over stoichiometric NaBHâ‚„/Borane). If stoichiometric is necessary, optimize equivalence [6]. |

| Activated Reagents for Coupling (e.g., HATU, EDCI) | Facilitates amide bond formation, etc. | Often have low atom economy, generating high molecular weight by-products. Consider direct catalytic coupling methods or greener activating agents to reduce PMI [6]. |

| Purification Media (e.g., Silica Gel, Chromatography Solvents) | Isolates and purifies the desired product. | A massive, often hidden, contributor to PMI. Intensify processes to avoid chromatography. Develop crystallization or distillation protocols instead [2]. |

| Dilithium sulphite | Dilithium Sulphite | High-Purity Reagent | RUO | Dilithium sulphite for advanced materials and chemistry research. High-purity, crystalline solid. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Lithium laurate | Lithium Laurate | Research Chemicals | RUO | High-purity Lithium Laurate for research applications. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. Explore its role in material science. |

Experimental Protocol: Standardized PMI Calculation and Optimization

This protocol provides a step-by-step method for calculating and analyzing PMI in a chemical reaction, suitable for benchmarking and optimization studies.

Objective: To determine the Process Mass Intensity (PMI) of a target reaction and identify key areas for potential improvement.

Materials:

- Reactants, reagents, solvents, catalysts

- Standard laboratory glassware and equipment

- Analytical balance

- ACS GCI PMI Calculator (available online) [3]

Procedure:

Reaction Execution:

- Carry out the synthesis reaction according to your standard procedure.

- Record the masses of all input materials (reactants, reagents, solvents, catalysts) to the maximum accuracy possible.

Workup and Isolation:

- Perform the standard workup and purification procedure (e.g., extraction, washing, crystallization, chromatography).

- Accurately record the masses of all solvents and materials used during these steps.

Product Isolation:

- Isolate the final, purified product.

- Accurately weigh and record the dry mass of the product.

- Calculate and record the reaction yield.

PMI Calculation:

- Option A (Manual): Sum the total mass of all materials used in the process (steps 1 and 2). Divide this sum by the mass of the isolated product from step 3. > PMI = (Σ Massinputs) / (Massproduct)

- Option B (Digital Tool): Input all recorded mass data into the ACS GCI PMI Calculator. The tool will automatically compute the PMI value [3].

Data Analysis and Optimization Strategy:

- Create a mass contribution pie chart. Categorize inputs as "Reaction Solvents," "Workup Solvents," "Reagents," "Catalysts," etc.

- Identify the largest mass contributors. These are your primary targets for optimization.

- Cross-reference this data with the troubleshooting guide (Section 2.1) to develop a specific action plan for PMI reduction (e.g., solvent recycling, catalytic conditions).

Reporting: Report the PMI value along with the isolated yield, concentration of the reaction (mass of product per volume of solvent), and the identity of the primary solvent. This standardized reporting allows for meaningful comparison with other processes and future optimizations [6].

In the pursuit of improving reaction mass efficiency in chemical research and drug development, accurately assessing the environmental and resource impacts of processes is paramount. A Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is a standardized methodology for evaluating the environmental impacts associated with all stages of a product's life, from raw material extraction through materials processing, manufacture, distribution, use, repair and maintenance, and disposal or recycling [10].

When defining the scope of an LCA, practitioners must choose appropriate system boundaries, which determine which processes are included in the assessment. For researchers focused on holistic sustainability metrics, the choice between gate-to-gate and cradle-to-gate analysis is particularly crucial:

- Gate-to-Gate: An assessment focused on a single process or manufacturing stage within the broader life cycle [11] [12]. It looks only at the inputs and outputs from the factory entry gate to the exit gate.

- Cradle-to-Gate: A partial life cycle assessment that includes all activities from the extraction of raw materials from the earth (the "cradle") up to the point where the product leaves the manufacturing facility (the "factory gate") [13] [14]. This includes raw material extraction, transport, and manufacturing processes.

For research aimed at improving reaction mass efficiency, adopting a cradle-to-gate perspective is essential for a true and complete understanding of process sustainability, as it captures the significant impacts embedded in the starting materials before they even reach the reaction vessel.

Why Cradle-to-Gate Matters for Reaction Mass Efficiency Research

The Problem with a Narrow Gate-to-Gate View

A gate-to-gate assessment, while simpler and requiring less data, provides a dangerously incomplete picture for sustainability research. It ignores the upstream environmental burden of the reagents, solvents, and catalysts used in a reaction. A process might appear highly efficient within the factory gates, but if it relies on starting materials that are energy-intensive to produce or are derived from non-renewable resources, the overall environmental impact can be substantial [12].

- Hidden Mass Inefficiencies: A gate-to-gate analysis might show excellent atom economy for a specific synthetic step. However, a cradle-to-gate view could reveal that one of the reagents itself has a very low mass efficiency from its own production process, making the overall system inefficient.

- Masked Environmental Hotspots: The largest environmental impact of a chemical process often lies in its supply chain. A 2019 review of LCA studies in bioenergy highlighted that most studies considered cradle-to-gate boundaries to fully account for resource consumption and emissions from feedstock production, which would be missed in a gate-to-gate view [13].

The Advantages of a Cradle-to-Gate Perspective

Expanding the system boundary to cradle-to-gate allows researchers and drug development professionals to:

- Identify True Improvement Levers: It reveals whether environmental impacts are dominated by in-house processing energy or by the embodied impacts of materials purchased from suppliers. This allows for targeted process optimization and informed supplier engagement [11] [12].

- Make Informed Material Choices: When designing a synthetic route, chemists can compare the cradle-to-gate impacts of different reagents or solvents. This enables selections that improve not just the immediate reaction's efficiency, but the overall environmental profile of the Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) [11].

- Provide Credible Data for Downstream Assessments: The cradle-to-gate impact data of an intermediate chemical is a critical piece of information for a company that uses it to produce a final drug product. Providing this data enables partners and customers to build more comprehensive, cradle-to-grave LCAs of the final pharmaceutical product [12].

- Drive Innovation in Green Chemistry: By accounting for the full mass and energy flows required to make a product, cradle-to-gate assessment aligns with the principles of Green Chemistry, particularly Atom Economy and Prevention of Waste. It encourages innovation to minimize the total material and energy consumption from the original resource extraction [15].

Methodologies: Implementing a Cradle-to-Gate LCA

According to the ISO 14040 and 14044 standards, conducting an LCA involves four iterative phases [10]. The following workflow and detailed breakdown outline this process for a cradle-to-gate assessment focused on a chemical synthesis.

Phase 1: Goal and Scope Definition

This is the most critical phase for a cradle-to-gate study. Here, you define the purpose and the boundaries of your system [10].

- Goal: State the intended application, the reason for the study, and the target audience. Example: "To identify the environmental hotspots of Synthetic Route A for API X to inform green chemistry optimization for internal R&D purposes."

- Functional Unit: Define a quantitative measure of the function of the product system. This provides a reference to which all inputs and outputs are normalized [16]. For chemical synthesis, this is typically 1 kg of a purified intermediate or final API. This allows for fair comparison between different synthetic routes.

- System Boundary: Explicitly state that the study is cradle-to-gate. The diagram below illustrates the typical processes included within this boundary for a chemical product.

Phase 2: Life Cycle Inventory (LCI)

In this phase, you collect data on all the energy and material inputs and environmental releases associated with your defined system [10].

- Data Collection: For a chemical synthesis, this involves creating a mass and energy balance for the process.

- Inputs: Mass of all reagents, solvents, catalysts; energy for heating, cooling, stirring; electricity for purification (e.g., chromatography, distillation); and water.

- Outputs: Mass of the desired product; and all waste streams including by-products, spent solvents, and filtrates.

- Data Sources:

- Primary Data: Measured data from your own lab or pilot plant experiments. This is the most reliable data for the "gate" processes.

- Secondary Data: For upstream (cradle) processes, such as the production of reagents and solvents, you will likely need to use data from commercial LCA databases (e.g., Ecoinvent, GaBi). These databases provide cradle-to-gate inventory data for thousands of chemicals.

Phase 3: Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA)

The inventory data is translated into potential environmental impacts. This phase classifies and characterizes emissions and resource uses into impact categories [10].

- Selection of Impact Categories: Choose categories relevant to chemical production. Common categories include:

- Global Warming Potential (GWP) - kg COâ‚‚ equivalent

- Acidification Potential - kg SOâ‚‚ equivalent

- Eutrophication Potential - kg POâ‚„ equivalent

- Abiotic Resource Depletion - kg Sb equivalent

- Water Use - cubic meters

Phase 4: Interpretation

This phase involves evaluating the results from the inventory and impact assessment to draw conclusions, explain limitations, and provide recommendations [10]. Key questions to ask:

- What are the major contributors (hotspots) to the overall environmental impact?

- Is the result significant compared to other processes or benchmarks?

- How sensitive are the results to key assumptions or data uncertainties?

- What are the limitations of the study?

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and tools essential for conducting a cradle-to-gate assessment in a research setting.

| Item | Function in Cradle-to-Gate Assessment |

|---|---|

| LCA Software (e.g., SimaPro, GaBi, OpenLCA) | Provides a platform to model the product system, manage inventory data, perform impact calculations, and visualize results. Essential for handling complex supply chains [10]. |

| Commercial LCA Databases | Source of secondary, cradle-to-gate data for common chemicals, energy carriers, and materials. Crucial for modeling the "cradle" part of the assessment when primary data from suppliers is unavailable [16]. |

| Functional Unit (e.g., 1 kg of product) | A quantified reference for the performance of the product system. Ensures all inputs, outputs, and impacts are normalized and allows for fair comparison between different synthetic routes or products [15] [16]. |

| Lab-scale Process Mass Balance | A detailed accounting of all mass inputs (reagents, solvents) and outputs (product, waste) from a lab-scale reaction. This is the primary data source for the "gate" (manufacturing) part of the assessment. |

| Energy Monitoring Equipment | Devices to measure electricity and other energy carriers (e.g., steam, chilled water) consumed by lab equipment (reactors, stirrers, HPLC, etc.). Needed to create a complete energy inventory. |

| N-Ethylbutanamide | N-Ethylbutanamide, CAS:13091-16-2, MF:C6H13NO, MW:115.17 g/mol |

| 2H-1,2,5-Oxadiazine | 2H-1,2,5-Oxadiazine|CAS 14271-57-9|For Research |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

Q1: My suppliers won't provide LCA data for their chemicals. How can I complete the cradle-to-gate assessment?

- Solution: This is a common data gap challenge [16]. The best practice is to use proxy data from reputable commercial LCA databases. These databases contain industry-average data for the production of many common chemicals. Document this assumption clearly in your report. As a secondary option, you can use economic input-output LCA (EIOLCA) data, though it is less precise [11].

Q2: Cradle-to-gate seems too complex for early-stage research. When should I start using it?

- Solution: It's true that a full, detailed LCA is resource-intensive. A practical approach is to start with a simplified screening-level LCA even at the early R&D stage [16]. This can be done by focusing on the most significant inputs (e.g., the top 3 reagents by mass) and using simplified database tools. This early insight can prevent investing in optimizing a route that is fundamentally flawed from a life-cycle perspective.

Q3: How do I handle multi-step syntheses and intermediates?

- Solution: Model the entire sequence of reactions within your system boundary. The output (and all its environmental burden) of one step becomes the input for the next step. LCA software is designed to handle this complexity by linking unit processes together. You can also use a gate-to-gate model for a specific intermediate and then incorporate it into a larger cradle-to-gate model for the final product [12].

Q4: What is the difference between a cradle-to-gate LCA and an Environmental Product Declaration (EPD)?

- Answer: A cradle-to-gate LCA is the underlying study and methodology. An Environmental Product Declaration (EPD) is a standardized, third-party verified document that communicates the results of an LCA, often based on cradle-to-gate data, in a consistent format, typically for business-to-business communication [11] [17].

Q5: The results of my assessment are dominated by the impacts of a single solvent. What should I do?

- Troubleshooting: You have successfully identified a critical hotspot!

- Interpretation: This is a positive finding, as it points to a clear opportunity for improvement.

- Action: Investigate alternative, greener solvents with a lower cradle-to-gate impact. Use solvent selection guides (e.g., ACS GCI Pharmaceutical Roundtable guide) in conjunction with your LCA findings.

- Optimization: Explore solvent recycling protocols within your process to reduce the net consumption of virgin solvent per kg of product, thereby reducing the overall burden.

The Critical Link Between Mass Efficiency, Waste Reduction, and Sustainability Goals

Technical Support Center: Mass Efficiency in Chemical Research

This support center provides practical guidance for researchers and scientists aiming to improve Reaction Mass Efficiency (RME) in their laboratories. The following FAQs and troubleshooting guides address common experimental challenges, helping to advance your research while supporting broader waste reduction and sustainability goals.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is Reaction Mass Efficiency (RME) and why is it a critical metric for sustainable research? Reaction Mass Efficiency (RME) is a green chemistry metric that calculates the proportion of reactant masses converted into the desired product. It is calculated as: (mass of product / total mass of reactants) x 100. A higher RME indicates less material waste and a more atom-economical process. It is critical because it directly links research efficiency to sustainability goals by minimizing resource consumption and waste generation at the source, which is a core principle of the circular economy [18]. Improving RME reduces the environmental footprint of research and development, particularly in sectors like pharmaceuticals [19].

2. How can I reduce solvent waste in my reactions? Solvents often account for the majority of waste in chemical synthesis. Several strategies can significantly reduce solvent waste:

- Adopt solvent-free synthesis: Explore mechanochemistry, which uses mechanical energy (e.g., ball milling) to drive reactions without solvents. This technique eliminates solvent waste entirely and is applicable to pharmaceuticals and material synthesis [19].

- Switch to aqueous systems: Implement in-water or on-water reactions. Water is a non-toxic, non-flammable, and abundant solvent that can facilitate many reactions, reducing the use of hazardous organic solvents [19].

- Use Alternative Solvents: Employ Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES). These are low-toxicity, biodegradable solvents made from mixtures of hydrogen bond donors and acceptors (e.g., choline chloride and urea). They are excellent for extractions and can be designed for circular chemistry, allowing for recovery and reuse [19].

3. My reaction yields are high, but my Mass Efficiency is low. What could be the cause? This is a common issue where the reaction is effective but inefficient. The primary cause is often the use of stoichiometric reagents instead of catalytic ones. For example, using a stoichiometric oxidizing agent instead of a catalytic one with a co-oxidant generates significant waste mass from the spent oxidizing agent. To troubleshoot:

- Investigate catalytic alternatives: Research and develop catalytic versions of your key reaction steps.

- Re-evaluate your reaction pathway: An AI-guided retrosynthesis tool can help design pathways with higher atom economy and lower inherent waste [19].

- Analyze your workup: Significant mass loss can occur during purification. Optimize purification protocols to minimize product loss.

4. What digital tools can help me track and improve the mass efficiency of my experiments? Leveraging digital tools is key to data-driven waste reduction:

- Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) Tools: Use LCA software to understand the full environmental impact of your products, from raw materials to disposal. This provides visibility for ESG reporting and helps identify hotspots for efficiency gains [20].

- AI Optimization Tools: Artificial Intelligence can predict reaction outcomes, optimize conditions (temperature, solvent choice), and design catalysts, reducing reliance on trial-and-error experimentation that consumes reagents [21] [19].

- Digital Twins: Create a virtual model of your experimental process. This allows you to test changes and optimize for efficiency before running physical experiments, saving materials and reducing waste [21] [20].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Atom Economy in a Key Reaction Step

- Step 1: Identify the Reaction → Determine the specific transformation with low atom economy (e.g., a functional group interconversion that generates a stoichiometric by-product).

- Step 2: Literature Review → Search for catalytic or tandem reaction methodologies that can achieve the same transformation. Focus on green chemistry literature.

- Step 3: Evaluate Alternative Pathways → Use the following table to compare the mass efficiency of your current method against a potential alternative.

Table 1: Comparison of Stoichiometric vs. Catalytic Reaction Pathways

| Parameter | Stoichiometric Pathway | Catalytic Pathway |

|---|---|---|

| Example Reaction | Oxidation with a stoichiometric reagent (e.g., KMnOâ‚„) | Catalytic oxidation with Oâ‚‚ or Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ |

| Theoretical Atom Economy | Low (mass of by-products is high) | High (water may be the only by-product) |

| Estimated E-Factor | High (>5-50) | Low (<1-5) |

| Key Advantage | Often simple and well-established | Drastically reduced waste; more sustainable |

| Key Challenge | Waste handling and disposal | May require specialized catalysts or equipment |

- Step 4: Pilot the Alternative → Design a small-scale experiment to test the most promising alternative pathway, carefully tracking RME and yield.

Problem: High Solvent Usage in Extraction and Purification

- Step 1: Audit Solvent Volumes → Record the types and volumes of all solvents used in workup and purification for a specific reaction.

- Step 2: Explore Alternative Techniques → Research and evaluate solvent-less or solvent-reduced methods. The diagram below outlines a logical decision pathway for solvent reduction.

Problem: Difficulty in Recovering and Reusing Catalysts or Expensive Reagents

- Step 1: Immobilize the Catalyst → Investigate heterogenization of homogeneous catalysts by attaching them to a solid support (e.g., silica, polymer).

- Step 2: Implement a Recovery Protocol → Design a simple filtration step to separate the solid catalyst from the reaction mixture.

- Step 3: Test Reusability → Reuse the recovered catalyst in a subsequent identical reaction and monitor any loss of activity over multiple cycles, tracking the effective mass of catalyst waste generated per cycle.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key reagents and materials that are essential for conducting mass-efficient and sustainable experiments.

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Green Chemistry Research

| Reagent/Material | Function & Application | Sustainability Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Ball Mill Reactor | Enables mechanochemistry for solvent-free synthesis of pharmaceuticals and materials [19]. | Eliminates solvent waste; reduces energy consumption by avoiding heating for solubility. |

| Earth-Abundant Element Catalysts (e.g., Fe, Ni) | Replacement for rare-earth elements in catalysts and materials (e.g., tetrataenite for magnets) [19]. | Reduces reliance on geopolitically concentrated, environmentally damaging mining operations. |

| Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) | Customizable, biodegradable solvents for extraction of metals from e-waste or bioactives from biomass [19]. | Low-toxicity, bio-based alternative to volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and strong acids; supports circular economy. |

| Bio-Based Feedstocks (e.g., algal oils, agricultural waste) | Renewable carbon source for producing bio-based polymers and chemicals [20]. | Lowers carbon emissions and reduces dependency on fossil-based feedstocks. |

| Heterogenized Catalysts | Catalysts immobilized on solid supports (e.g., silica) for easy separation and reuse [22]. | Improves resource efficiency, reduces waste, and lowers the cost per reaction cycle. |

| H-Leu-Asn-OH | H-Leu-Asn-OH, CAS:14608-81-2, MF:C10H19N3O4, MW:245.28 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Demelverine | Demelverine|CAS 13977-33-8|For Research | Demelverine high-purity compound for research applications. CAS 13977-33-8. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

Experimental Protocols for Mass Efficiency

Protocol 1: Solvent-Free Synthesis using Mechanochemistry

- Objective: To synthesize a target compound (e.g., a pharmaceutical intermediate) via ball milling, eliminating solvent waste.

- Materials: Ball mill apparatus, grinding jars and balls, reactants.

- Methodology:

- Loading: Weigh and load stoichiometric amounts of solid reactants into the grinding jar. If one reactant is a liquid, it can be added in a minimal, stoichiometric quantity.

- Milling: Seal the jar and place it in the ball mill. Run the mill for the optimized time and frequency.

- Monitoring: Use techniques like in-situ Raman spectroscopy or periodic sampling with HPLC/GC to monitor reaction progress.

- Work-up: Upon completion, the crude product is often a powder that can be directly purified, for example, by washing with a small volume of a benign solvent or by sublimation, avoiding traditional liquid-liquid extraction.

- Key Measurements: Record yield, purity, and calculate RME and E-factor. Compare these metrics to the traditional solvent-based method.

Protocol 2: AI-Guided Reaction Optimization for Waste Reduction

- Objective: To minimize the E-factor of a reaction by using AI to optimize conditions.

- Materials: High-throughput experimentation equipment, AI/ML software platform (commercial or open-source).

- Methodology:

- Define Search Space: Identify key variables to optimize (e.g., catalyst loading, solvent choice, temperature, concentration).

- Initial Dataset: Run a small set of initial experiments (e.g., via Design of Experiments) to generate baseline data.

- AI Model Training: Input the data into the AI platform. The model will be trained to predict outcomes like yield and impurity profile.

- Autonomous Optimization: The AI suggests the next set of experiments to run, iteratively closing in on the conditions that maximize RME and minimize waste.

- Validation: Perform the AI-optimized reaction at a slightly larger scale to validate the predicted results.

- Key Measurements: The primary success metric is a significant reduction in the E-factor while maintaining or improving yield and selectivity [21] [19].

The workflow below illustrates the iterative, data-driven process of using AI to optimize a reaction for mass efficiency.

A lower Process Mass Intensity (PMI) is often assumed to mean a greener process, but this can be a dangerous oversimplification for scientists aiming to make truly sustainable innovations.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is Process Mass Intensity (PMI) and why is it so widely used? Process Mass Intensity (PMI) is a key green chemistry metric used to benchmark the efficiency of a process. It is defined as the total mass of materials used to produce a given mass of product [1]. This includes all reactants, reagents, solvents (used in both reaction and purification), and catalysts. It is popular in the pharmaceutical industry and elsewhere because it offers a seemingly straightforward way to focus on resource efficiency and waste reduction using easy-to-determine process mass balance data [5] [1].

2. My reaction has a low PMI. Why can't I assume it is the most environmentally friendly option? A low PMI is an excellent indicator of mass efficiency, but it is not a direct measure of environmental impact [5]. The core limitation is that PMI treats all masses as equal. It does not distinguish between:

- Different Material Origins: A kilogram of water and a kilogram of a precious metal complex have the same mass but vastly different environmental footprints from their production.

- Material Hazards: It does not account for the toxicity, persistence, or other hazards associated with waste streams.

- Energy Consumption: The metric completely neglects the type and amount of energy required to run the process (e.g., heating, cooling, pressure), which can be a major contributor to environmental impacts like climate change [5].

3. What is the difference between a "gate-to-gate" and "cradle-to-gate" boundary, and why does it matter for PMI? The system boundary defines what is included in the PMI calculation and is a major source of its limitations [5].

- Gate-to-Gate (Standard PMI): This common approach only considers materials used within the factory's own process. It is a limited view that misses the upstream environmental burden.

- Cradle-to-Gate (Value-Chain Mass Intensity - VCMI): This expanded boundary includes all natural resources required from the extraction of raw materials (the "cradle") up to the factory gate. A cradle-to-gate assessment is necessary to account for the full resource footprint of your inputs [5]. Research shows that expanding the system boundary to cradle-to-gate strengthens the correlation between mass intensity and environmental impacts for most impact categories [5].

4. Are there real-world examples where a process with a better PMI performs worse environmentally? Yes. The 2025 study by Eichwald et al. systematically demonstrates this. They found that the correlation between mass intensity and life cycle assessment (LCA) impacts varies significantly depending on the specific environmental impact in question and the key input materials involved [5]. For instance:

- A process might use a coal-derived chemical, contributing significantly to climate change, but this would not be weighted differently in a simple PMI calculation.

- A process with a slightly higher PMI might use benign solvents and renewable electricity, giving it a much lower impact on ecosystem quality or carbon emissions than a lower-PMI alternative that uses hazardous solvents and grid power.

5. What is the recommended alternative for a more accurate environmental assessment? For a meaningful evaluation of environmental performance, Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is the recommended and most robust method [5]. LCA is a holistic approach that evaluates multiple environmental impacts (e.g., climate change, water use, toxicity) across the entire life cycle of a product. While it requires more data and expertise, the scientific consensus is that future research should focus on developing and using simplified LCA methods tailored for chemists where full LCA is not feasible, rather than relying on mass-based proxies [5].

Troubleshooting Guide: Improving Your Environmental Assessment

This guide helps you diagnose and address common pitfalls when using PMI in your research.

| Symptom | Potential Root Cause | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| A new, low-PMI process shows unexpected high energy use or emissions. | Gate-to-gate myopia: The PMI calculation ignores upstream impacts of key reagents and the energy profile of the process [5]. | Expand analysis to a cradle-to-gate perspective. Use emission factors to estimate CO2 from energy use and prioritize screening LCA for high-mass or specialty inputs [5]. |

| Your green chemistry metrics (like PMI and RME) are strong, but a safety audit flags hazardous waste issues. | Mass metrics are blind to hazard. PMI treats a kilogram of water and a kilogram of heavy metal waste as identical [23]. | Integrate hazard assessment tools like the CHEM21 Solvent Selection Guide [24]. Optimize to eliminate or substitute hazardous solvents and reagents, even if mass efficiency stays the same. |

| Two synthetic routes have similar PMIs, but you cannot determine which is truly greener. | PMI lacks specificity. It is a single score that cannot capture the multi-criteria nature of environmental sustainability [5]. | Employ a multi-metric assessment. Combine PMI with Atom Economy, and crucially, use LCA-based indicators like Global Warming Potential for a definitive comparison [5]. |

| You need to predict the environmental profile of a route before running lab experiments. | PMI requires experimental data. | Use predictive tools like the PMI Prediction Calculator from ACS GCI PR [1] or the reaction optimization spreadsheet that combines kinetics, solvent greenness, and metrics to model performance in silico [24]. |

Experimental Protocol: A Multi-Faceted Workflow for Greener Reaction Optimization

The following workflow integrates kinetics, solvent selection, and green metrics to help you optimize reactions for both performance and genuine environmental benefit, moving beyond PMI alone [24].

1. Objective To systematically optimize a chemical reaction for performance and environmental sustainability by integrating kinetic analysis, solvent effect modeling, and multi-criteria green metrics evaluation.

2. Materials and Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Solution | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| Kinetic Data (Concentration vs. Time) | Raw data required for VTNA and LSER analysis to understand reaction mechanics [24]. |

| Variable Time Normalization Analysis (VTNA) | A spreadsheet-based method to determine reaction orders without complex mathematical derivations [24]. |

| Linear Solvation Energy Relationship (LSER) | A multiple linear regression model correlating solvent polarity parameters (α, β, π*) with reaction rate to understand solvent effects [24]. |

| CHEM21 Solvent Selection Guide | A guide ranking solvents based on Safety, Health, and Environment (SHE) scores to assess greenness [24]. |

| Green Metrics Calculator | A spreadsheet tool for calculating Atom Economy (AE), Reaction Mass Efficiency (RME), and Process Mass Intensity (PMI) [24]. |

3. Procedure

The workflow for optimizing a reaction is a cyclical process of generating data, modeling, and making informed changes. The diagram below illustrates the key stages.

Step 1: Data Generation and Kinetic Analysis

- Run the initial reaction and collect kinetic data by measuring reactant and/or product concentrations at timed intervals (e.g., via NMR) [24].

- Input the concentration-time data into the reaction optimization spreadsheet [24].

- Use the Variable Time Normalization Analysis (VTNA) worksheet to determine the empirical order of the reaction with respect to each reactant. This is done by testing different potential orders until the data from reactions with different initial concentrations overlap onto a single curve [24].

- The spreadsheet will automatically calculate the rate constant (k) for each experimental run once the correct orders are identified [24].

Step 2: Modeling Solvent Effects and Selection

- For a set of experiments run in different solvents but with the same determined reaction order and temperature, use the LSER worksheet.

- Correlate the natural logarithm of the rate constant (ln(k)) with Kamlet-Abboud-Taft solvatochromic parameters (hydrogen bond donating ability α, hydrogen bond accepting ability β, and dipolarity/polarizability π*) [24].

- The spreadsheet will generate a statistically relevant equation (e.g.,

ln(k) = C + aα + bβ + cπ*) showing which solvent properties accelerate the reaction [24]. - Use this model to predict rate constants for other solvents and cross-reference these predictions with the CHEM21 Solvent Selection Guide scores in the "Solvent Selection" worksheet. This allows you to shortlist solvents that are both high-performing and green [24].

Step 3: Multi-Criteria Evaluation and Iteration

- Based on the predicted performance from Steps 1 and 2, propose new, greener reaction conditions (e.g., a different solvent, concentration, or temperature).

- Use the "Metrics" worksheet in the spreadsheet to predict the product conversion at a set time and calculate a suite of green chemistry metrics, including Atom Economy, Reaction Mass Efficiency, and Process Mass Intensity for the proposed conditions [24].

- Critically evaluate the results. A high RME or low PMI is good, but must be considered alongside the hazard profile of the chosen solvent and the reaction rate (which affects energy use). Use this multi-faceted view to decide if further optimization is needed [5] [24].

- Iterate the process (return to Step 1) until an optimal balance of performance, mass efficiency, and environmental safety is achieved.

Key Takeaways for Researchers

- PMI is an indicator, not a definitive measure. Use it as a quick snapshot of mass efficiency, not a comprehensive green scorecard [5].

- Context is critical. Always consider the system boundaries (gate-to-gate vs. cradle-to-gate) and the specific materials involved when interpreting PMI [5].

- Embrace multi-metric and LCA thinking. For robust environmental claims, complement PMI with other metrics and, when possible, transition toward Life Cycle Assessment methodologies [5].

AI and Automation: Next-Generation Strategies for Reaction Optimization

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Handling "Physically Implausible" Predictions for Novel Reactions

Problem: FlowER is generating reaction predictions that violate fundamental physical laws, such as the conservation of mass, particularly for reaction types not well-represented in its training data.

- Step 1 – Verify Reaction Input: Ensure the input reactants are correctly represented in the bond-electron matrix. The system uses nonzero values for bonds or lone electron pairs and zeros otherwise [25].

- Step 2 – Check Training Data Scope: Confirm whether your reaction involves metals or catalysis. The initial FlowER model has limited coverage of these chemistries, as its training on U.S. Patent Office data lacks certain metals and catalytic reactions [25] [26].

- Step 3 – Utilize Open-Source Data: Cross-reference the predicted pathway with the open-source dataset of mechanistic steps provided by the Coley Group to see if a similar mechanistic pathway has been imputed from experimental data [25].

Issue 2: Integrating FlowER Predictions with Green Chemistry Metric Calculations

Problem: A researcher wants to use FlowER's predicted reaction pathways to calculate green metrics like Reaction Mass Efficiency (RME) but encounters difficulties connecting the AI output to metric calculation tools.

- Step 1 – Extract Reaction Components: From the FlowER-predicted reaction mechanism, extract the final balanced chemical equation, ensuring all atoms and electrons are conserved in the output [25] [27].

- Step 2 – Input into Optimization Spreadsheet: Use the extracted quantitative data (reactant and product masses, solvent details) as input for a reaction optimization spreadsheet designed for calculating green metrics [24].

- Step 3 – Calculate Metrics: The spreadsheet can then compute key metrics such as Atom Economy, Reaction Mass Efficiency (RME), and Optimum Efficiency, helping to evaluate the predicted reaction's environmental performance [24].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core technological innovation behind FlowER that ensures physical realism? FlowER (Flow matching for Electron Redistribution) utilizes a bond-electron matrix, a concept from the 1970s, to represent the electrons in a reaction. This matrix uses nonzero values to represent bonds or lone electron pairs and zeros to represent a lack thereof, which explicitly enforces the conservation of both atoms and electrons during its predictions, unlike standard large language models [25] [26].

Q2: What are the known limitations of the current FlowER model? The primary limitation is the breadth of its training data. While trained on over a million chemical reactions from a U.S. Patent Office database, the data does not comprehensively include certain metals and many kinds of catalytic reactions. The development team is actively working on expanding the model's understanding of these areas [25] [26] [27].

Q3: How can FlowER contribute directly to improving Reaction Mass Efficiency (RME) in research? By accurately predicting the outcome of a reaction and its full mechanism, FlowER allows researchers to calculate the Atom Economy of a synthetic pathway in silico before running actual experiments. Since Atom Economy is a key component of RME (Reaction Mass Efficiency = Yield × Atom Economy), FlowER enables the virtual screening and optimization of reactions for greener outcomes by identifying high-yielding pathways with minimal wasted atoms [24].

Q4: Is FlowER available for public use, and if so, how can it be accessed? Yes, the FlowER model is open-source. The models, data, and related datasets are freely available on GitHub, allowing researchers to use and build upon the tool [25].

Experimental Data and Protocols

Quantitative Performance Data of FlowER

The table below summarizes key quantitative aspects of FlowER as reported in the research.

| Metric | Description | Performance/Value |

|---|---|---|

| Training Data Size | Number of chemical reactions used for model training [25] [26] | Over 1 million reactions |

| Physical Constraint Adherence | Success in conserving mass and electrons in predictions [25] [27] | Ensures conservation of all atoms and electrons |

| Prediction Accuracy | Performance in finding standard mechanistic pathways [25] | Matches or outperforms existing approaches |

| Generalization Capability | Ability to predict previously unseen reaction types [25] | Possible to generalize to new reactions |

Protocol: Utilizing FlowER for Green Reaction Optimization

This protocol outlines the steps for using FlowER in conjunction with green chemistry principles to optimize reaction mass efficiency.

- Reaction Prediction: Input the proposed reactants into the FlowER model to generate a physically plausible prediction of the reaction mechanism and products [25].

- Pathway Validation: Inspect the electron redistribution pathway provided by FlowER to verify the mechanism aligns with known chemical principles and that atom economy is maximized [25] [27].

- Data Extraction for Metrics: From the validated reaction, extract the balanced chemical equation, including all reagents and solvents used in the mechanism.

- Green Metric Calculation: Input the extracted data into a reaction optimization spreadsheet [24]. This tool will calculate:

- Atom Economy: (Molecular Weight of Desired Product / Sum of Molecular Weights of All Reactants) × 100%.

- Reaction Mass Efficiency (RME): (Mass of Product / Total Mass of Reactants) × 100%. A key metric for assessing waste reduction.

- Optimum Efficiency: A metric that factors in yield and excess reagents to evaluate the optimal efficiency of a chemical process [24].

- Iterative Optimization: Use the calculated metrics to evaluate the greenness of the proposed reaction. Iterate by exploring different solvents or reagents in FlowER to find a pathway with improved mass efficiency.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key computational and data resources essential for working with AI-based reaction prediction tools like FlowER in the context of green chemistry.

| Research Reagent | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Bond-Electron Matrix | A computational representation of a molecule where bonds and lone electron pairs are explicitly tracked, forming the foundation of FlowER's physically constrained predictions [25]. |

| Open-Source Reaction Dataset | A comprehensive dataset of mechanistic steps, exhaustively listing known reactions. Used for training, validation, and benchmarking of prediction models [25]. |

| Reaction Optimization Spreadsheet | A tool for processing kinetic data, calculating green metrics (Atom Economy, RME), and understanding solvent effects via Linear Solvation Energy Relationships (LSER) [24]. |

| U.S. Patent Office Database | A source of over a million experimentally validated chemical reactions used to train and anchor the FlowER model in real-world data [25] [26]. |

Workflow Visualization

AI-Driven Reaction Optimization Workflow

FlowER's AI Prediction Core

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This section addresses common challenges researchers may encounter when using the Minerva Framework for High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) in reaction mass efficiency studies.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary function of the Minerva API within the HTE workflow? A1: The Minerva API acts as a unified metric-serving layer, creating an essential interface between your upstream experimental data models and all downstream analysis applications. It abstracts the complexities of data location ("where") and metric computation ("how"), enabling consistent and correct data consumption across your research pipeline. This ensures that metrics like reaction yield or mass efficiency are calculated uniformly, whether viewed in a dashboard or used for machine learning model training [28].

Q2: My query for a derived metric (e.g., atom economy) is failing or returning unexpected results. What are the first elements I should check? A2: Begin by deconstructing the derived metric into its atomic components. The Minerva API processes complex metrics by first breaking them down into atomic sub-queries [28]. Verify the configuration and individual accuracy of these underlying atomic metrics (e.g., molecular weight of product, molecular weight of reactant). Ensure the definitions and data sources for these base metrics are correctly specified in the Minerva configuration files stored in S3 [28].

Q3: How does Minerva ensure it uses the most complete and correct data source for my query? A3: Minerva employs a service called the Metadata Fetcher. This service periodically (every 15 minutes) fetches metadata about all available data sources, checks their completeness (including time-range coverage), and caches this information. When you execute a query, Minerva consults this cache to select the optimal data source that contains all necessary columns and covers your required time range, thereby prioritizing data quality and completeness [28].

Q4: We are experiencing performance bottlenecks when querying large-scale HTE data over extended time ranges. How can this be mitigated within Minerva? A4: The Minerva API is designed to handle large queries by automatically splitting them into smaller, more manageable "slices" that span shorter time ranges. It executes these slices separately and then combines the results into a final dataframe. This approach helps avoid resource limitations and improves overall query reliability [28].

Q5: Can I use Minerva for analyzing data from biological or microbiological HTE systems? A5: Yes, though it is distinct from the data platform Minerva. A specialized platform, MINERVA (Microbiome Network Research and Visualization Atlas), is designed specifically for this purpose. It constructs a scalable knowledge graph to map complex microbiome-disease associations and supports the visualization of these intricate networks, which can be highly valuable in drug development research [29].

Common Error Codes and Resolutions

Error:

INCOMPLETE_DATA_SOURCE- Cause: The Metadata Fetcher has identified that all potential data sources for your query are missing data for the requested date range [28].

- Solution: Shorten the query's date range. Check the status of data pipelines to ensure recent data has been processed successfully.

Error:

ATOMIC_METRIC_DEFINITION_NOT_FOUND- Cause: The configuration for a base atomic metric used in your derived metric calculation is missing from the central repository [28].

- Solution: Verify the names of all atomic metrics in your derived metric formula. Work with your data platform team to ensure the metric definitions are properly published and stored in S3 [28].

Error:

QUERY_TIMEOUT- Cause: The query is too complex or the data volume is too high for a single execution node.

- Solution: The system should automatically attempt to split the query. If it persists, simplify the query by reducing the number of dimension cuts or breaking it into multiple, more focused queries [28].

Quantitative Data and Experimental Protocols

The following table outlines core quantitative metrics essential for evaluating reaction mass efficiency in an HTE context, which can be managed and served via the Minerva framework.

| Metric Name | Definition | Data Type | Example Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reaction Yield | (Moles of product / Moles of limiting reactant) * 100 | Percentage | HPLC Analysis |

| Reaction Mass Efficiency | (Mass of product / Total mass of all reactants) * 100 | Percentage | Mass Balance Data |

| Atom Economy | (MW of desired product / Sum of MWs of all reactants) * 100 | Percentage | Molecular Structure Files |

| Space-Time Yield | Mass of product / (Reactor Volume * Time) | kg Lâ»Â¹ hâ»Â¹ | Process Loggers |

| E-Factor | Total mass of waste / Mass of product | Dimensionless | Mass Balance Data |

Detailed Methodology for Key Experiments

Protocol: High-Throughput Screening for Catalytic Reaction Optimization

1. Objective: To systematically identify the optimal catalyst and solvent combination that maximizes Reaction Mass Efficiency for a given transformation.

2. Materials & Reagents:

- Substrate Library: A diverse set of relevant chemical starting materials.

- Catalyst Array: A collection of potential catalysts (e.g., Pd, Cu, Ni-based complexes).

- Solvent Matrix: A range of solvents covering different polarities and properties (e.g., DMF, THF, Toluene, Water).

- Minerva Data Client: Integration with a Python or R client for immediate data submission and metric retrieval [28].

3. Workflow:

- Plate Setup: Utilize an automated liquid handler to dispense substrates, catalysts, and solvents into a 96-well or 384-well reaction plate.

- Reaction Execution: Conduct reactions under controlled atmospheric conditions (e.g., under Nâ‚‚) and a defined temperature profile using a parallel thermoshaker.

- Quenching & Dilution: Automatically quench reactions after a specified time and prepare samples for analysis.

- Analysis: Analyze samples via UPLC-MS/HPLC for conversion and yield determination.

- Data Ingestion: Stream results data to the data warehouse (e.g., Druid) that is connected to the Minerva framework [28].

- Metric Calculation & Visualization: Use the Minerva API to compute key metrics like Reaction Mass Efficiency and Yield. Visualize the results in a BI tool like Superset to identify top-performing conditions [28].

Workflow and Signaling Pathway Visualizations

Minerva HTE Data Consumption Workflow

Minerva API Query Execution Logic

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The following table details key reagents and materials commonly used in HTE campaigns for drug development, whose performance and efficiency data can be managed through a system like Minerva.

| Item Name | Function / Role in HTE | Example in Reaction Mass Efficiency Context |

|---|---|---|

| Catalyst Library | Speeds up the reaction rate and can influence selectivity. | A diverse set of catalysts is screened to find the one that maximizes yield while minimizing loading (mass). |

| Solvent Matrix | The medium in which the reaction occurs, affecting solubility and kinetics. | Different solvents are screened to find alternatives that are safer, allow higher concentrations, and improve mass efficiency. |

| Reagent Array | Provides necessary reactants or coupling partners. | Evaluating different reagents can identify atom-economical alternatives that produce less waste. |

| Substrate Scope | The core starting materials for the chemical transformation. | Understanding how the reaction performs with diverse substrates is crucial for evaluating the generality and robustness of an efficient process. |

| Analysis Standards | Reference materials for quantifying reaction outcomes. | Essential for calibrating analytical equipment (e.g., HPLC) to accurately measure conversion and yield, the foundation of all efficiency calculations. |

| Vanadium chloride(VCl2) (6CI,8CI,9CI) | Vanadium Dichloride (VCl2) | High-purity Vanadium Dichloride (VCl2), a specialty reductant. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| Ammonium stearate | Ammonium stearate, CAS:1002-89-7, MF:C18H39NO2, MW:301.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Multi-Objective Bayesian Optimization for Simultaneously Maximizing Yield and Selectivity

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What makes Multi-Objective Bayesian Optimization (MOBO) superior to traditional methods like OFAT for reaction optimization? Traditional One-Factor-At-a-Time (OFAT) approaches are inefficient and often misidentify true optimal conditions because they ignore synergistic effects between experimental factors and fail to explore the complex, nonlinear response of chemical systems [30]. In contrast, MOBO uses a principled framework to explicitly model this complexity. It performs deliberate exploration by trading off between exploring new areas of the parameter space and exploiting known promising regions, leading to more efficient identification of conditions that simultaneously maximize yield and selectivity [31].

FAQ 2: My BO algorithm seems to converge slowly or get stuck. What could be wrong? Common pitfalls that cause poor BO performance include an incorrect prior width in the probabilistic model, over-smoothing, and inadequate maximization of the acquisition function [31]. For instance, if the Gaussian Process prior is too narrow, the model becomes overconfident and may fail to explore promising regions of the parameter space. Ensuring proper tuning of these hyperparameters is critical for achieving state-of-the-art performance [31].

FAQ 3: How can I optimize for both yield and selectivity, especially when they might conflict? MOBO is specifically designed for such multi-objective problems. Instead of finding a single "best" solution, it identifies a set of Pareto optimal solutions—conditions where improving one objective (e.g., yield) would lead to a decline in the other (e.g., selectivity) [32]. Advanced algorithms like MOBO-OSD generate a diverse set of these optimal conditions by solving multiple constrained optimization problems along well-distributed Orthogonal Search Directions, providing you with a range of optimal trade-offs to choose from [32].

FAQ 4: What are the key green chemistry metrics I should track alongside yield and selectivity? While yield is crucial, a comprehensive view of reaction efficiency requires additional metrics [7]. Key metrics include:

- Reaction Mass Efficiency (RME): Measures the mass of desired product relative to the masses of all reactants, accounting for yield and stoichiometry [7].

- Process Mass Intensity (PMI): The total mass of materials used in a process divided by the mass of the product. An ideal PMI is 1, and lower values indicate a more efficient process [7].

- Atom Economy (AE): Assesses the efficiency of a reaction by calculating the proportion of reactant atoms incorporated into the final desired product [7].

FAQ 5: Can MOBO be used with categorical variables, like solvent or catalyst type? Yes, Bayesian optimization can handle a mix of continuous variables (e.g., temperature, reaction time) and categorical variables (e.g., solvent or catalyst choice) [30]. This allows for a comprehensive optimization campaign that searches across all relevant dimensions of the experimental parameter space.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Optimization Performance or Slow Convergence

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Incorrect Prior Width [31] | Review the surrogate model's hyperparameters (e.g., GP lengthscale and amplitude). Check if the model uncertainty is poorly calibrated. | Adjust the prior distributions to better reflect the expected scale of the objective functions. Re-tune hyperparameters. |

| Over-smoothing [31] | Observe if the surrogate model fails to capture short-scale variations in your experimental data. | Consider using a different kernel function or ensemble of models that can capture more complex, nonlinear responses. |

| Inadequate Acquisition Maximization [31] | Check if the algorithm is selecting suboptimal points for evaluation. | Ensure the acquisition function is thoroughly optimized in each iteration, potentially using a global optimizer. |

| Sparse, High-Dimensional Space [33] | Note if the number of parameters is large relative to the experimental budget. | Employ techniques designed for high-dimensional spaces, such as optimization over sparse axis-aligned subspaces. |

Problem: Inadequate Trade-off Between Objectives

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Coverage of Pareto Front [32] | Analyze the set of solutions; they may be clustered in a small region of the objective space. | Use an algorithm like MOBO-OSD that employs Orthogonal Search Directions to ensure broad coverage and a diverse set of Pareto optimal solutions [32]. |

| Too Few Subproblems [32] | The final set of candidate solutions may not be dense enough. | Leverage Pareto Front Estimation techniques to generate additional optimal solutions in the neighborhoods of existing ones without requiring an excessive number of evaluations [32]. |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Foundational MOBO Workflow for Reaction Optimization

The following diagram illustrates the core iterative loop of Bayesian Optimization, adapted for chemical reaction objectives.

Protocol 1: Setting Up the MOBO Loop for a Model Reaction

This protocol outlines the steps for using MOBO to optimize a reaction, such as an aza-Michael addition [24].

1. Define Objectives and Parameter Space:

- Objectives: Clearly define the primary objectives. For example: Maximize Reaction Yield (%) and Maximize Selectivity for the desired product [34] [24].

- Parameters (Factors): Identify the continuous and categorical factors to optimize.

- Continuous: Temperature (°C), Reaction Time (hours), Catalyst Loading (mol%), Reactant Equivalents.

- Categorical: Solvent (e.g., DMSO, EtOH, 2-MeTHF), Catalyst Type.

2. Establish Initial Data Set:

- Perform an initial set of experiments (10-20) using a space-filling design like a Latin Hypercube or a predefined Design of Experiments (DoE) template to gather baseline data [30]. This provides the surrogate model with initial information about the response surface.

3. Configure the Probabilistic Surrogate Model:

- Use a model capable of handling multiple outputs, such as a Multi-Output Gaussian Process (GP).

- For continuous parameters, the RBF kernel is a common choice:

kRBF(x, x') = σ² exp( -‖x - x'‖² / (2ℓ²) )[31]. Carefully choose the amplitude (σ) and lengthscale (ℓ) hyperparameters.

4. Select a Multi-Objective Acquisition Function:

- The acquisition function guides the search by quantifying the promise of a new experiment. Common choices for MOBO include:

- Expected Hypervolume Improvement (EHVI): Measures the expected increase in the dominated volume of the objective space.

- ParEGO: Applies a scalarization technique to the multiple objectives to simplify the problem.

5. Iterate the MOBO Loop:

- Fit the Model: Update the surrogate model with all available data.

- Optimize Acquisition: Find the parameters that maximize the acquisition function. This is often the computational bottleneck.

- Run Experiment: Perform the physical experiment with the proposed conditions.

- Evaluate Convergence: Stop when the hypervolume improvement between iterations falls below a set threshold, or a predetermined experimental budget is exhausted.

Protocol 2: Calculating Key Performance Metrics

Track these metrics for each experiment to assess performance against green chemistry principles [7] [24].

1. Percent Yield:

Yield (%) = (Actual Yield of Product / Theoretical Yield) × 100 [34]

2. Selectivity:

Selectivity (%) = (Moles of Desired Product / Moles of All Products) × 100 [34]

3. Reaction Mass Efficiency (RME):

RME (%) = (Mass of Product / Total Mass of Reactants) × 100 [7]

This metric is more informative than yield alone as it accounts for atom economy and stoichiometry.

4. Process Mass Intensity (PMI):

PMI = Total Mass of Materials Used in Process / Mass of Product [7]

A lower PMI indicates a more efficient and less waste-intensive process. The ideal PMI is 1.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key computational and chemical resources used in MOBO-driven reaction optimization.

| Item Name | Type | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Gaussian Process (GP) Surrogate Model [31] | Computational Model | Serves as a probabilistic surrogate for the expensive-to-evaluate experimental objectives. It models the uncertainty of predictions, which is essential for the exploration-exploitation trade-off. |

| Expected Improvement (EI) [31] | Acquisition Function | A common acquisition function for single-objective optimization. Measures the expected amount by which a point is predicted to improve upon the best-known value. The multi-objective extension is EHVI. |

| Orthogonal Search Directions (OSD) [32] | Algorithmic Component | Used in advanced MOBO algorithms like MOBO-OSD to ensure a diverse set of Pareto optimal solutions by solving subproblems along well-distributed directions in the objective space. |

| Linear Solvation Energy Relationships (LSER) [24] | Analytical Tool | Correlates reaction rates (e.g., ln(k)) with solvent polarity parameters (α, β, π*). The resulting model helps understand the reaction mechanism and identify high-performance, greener solvents. |

| Variable Time Normalization Analysis (VTNA) [24] | Kinetic Analysis Method | A spreadsheet-based technique to determine reaction orders without complex mathematical derivations. Understanding reaction kinetics is vital for meaningful optimization. |

| CHEM21 Solvent Selection Guide [24] | Green Chemistry Tool | Ranks solvents based on Safety, Health, and Environment (SHE) scores. Used to select efficient solvents with minimal hazards, aligning optimization with green chemistry principles. |

| Boc-Phe-Phe-OH | Boc-Phe-Phe-OH|412.5 g/mol|CAS 13122-90-2 | Boc-Phe-Phe-OH is a protected dipeptide building block for peptide synthesis and self-assembly research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Chrysosplenol D | Chrysosplenol D, CAS:14965-20-9, MF:C18H16O8, MW:360.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Data Presentation: Key Metrics for Reaction Optimization

The following table summarizes the core quantitative metrics that should be calculated and optimized during a MOBO campaign to improve Reaction Mass Efficiency.

| Metric | Calculation Formula | Ideal Value | Significance in Optimization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Yield [34] | Based on stoichiometry of balanced equation | N/A | The maximum possible product mass, used as a benchmark for calculating actual yield. |

| Actual Yield [34] | Mass of product obtained experimentally | N/A | The raw experimental result. |

| Percent Yield [34] | (Actual Yield / Theoretical Yield) × 100 |

100% | Measures efficiency in converting reactants to the desired product. |

| Selectivity [34] | (Moles Desired Product / Moles All Products) × 100 |

100% | Measures preference for forming the desired product over side products. |

| Atom Economy (AE) [7] | (MW Desired Product / Σ MW Reactants) × 100 |

100% | Theoretical metric assessing the fraction of reactant atoms embedded in the final product. |

| Reaction Mass Efficiency (RME) [7] | (Mass of Product / Total Mass of Reactants) × 100 |

100% | A more comprehensive metric than yield, as it incorporates both yield and atom economy. |

| Process Mass Intensity (PMI) [7] | Total Mass of All Materials / Mass of Product |

1 | A global mass metric; lower values indicate less waste and a more efficient process. |

Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling is a fundamental transformation for constructing carbon-carbon bonds, extensively used in pharmaceutical and agrochemical industries. While palladium catalysts have traditionally dominated this field, their high cost and environmental impact have driven research toward cheaper, earth-abundant alternatives. Nickel has emerged as a promising candidate, being almost three times cheaper than palladium and having a significantly lower environmental footprint (producing 6.5 kg of COâ‚‚ per kg of metal versus 3880 kg for Pd) [35].

However, nickel-catalyzed Suzuki couplings present distinct challenges, including competitive side reactions, catalyst deactivation, and the frequent requirement for specialized ligands and additives. This case study examines the optimization of a specific challenging Ni-catalyzed Suzuki coupling through AI-assisted troubleshooting, framed within our broader thesis research on improving reaction mass efficiency in pharmaceutical development.

Experimental Background: The Problematic Reaction

Initial Reaction Setup and Observed Issues

Our investigation began with a base-free nickel-catalyzed decarbonylative coupling of acid fluorides with diboron reagents, adapted from recent literature [36]. The proposed mechanism proceeds through four stages: (1) oxidative addition of the acid fluoride to the Ni(0) center, (2) transmetalation with diboron reagent, (3) carbonyl deinsertion, and (4) reductive elimination to afford the coupling product.

Initial Conditions:

- Catalyst: Ni(COD)₂ with PCy₃ ligands

- Substrates: ArC(O)F and Bâ‚‚Pinâ‚‚

- Solvent: Toluene

- Temperature: 110°C

- Base: None (base-free conditions)

Observed Problems:

- Low conversion (<25%) of starting material

- Significant formation of biaryl byproducts (up to 40% of total products)

- Catalyst decomposition evident after 2 hours

- Inconsistent reproducibility between batches

AI-Assisted Troubleshooting Guide

Problem Diagnosis with Machine Learning Analysis

FAQ: How can AI help diagnose issues in nickel-catalyzed couplings?

AI-powered troubleshooting agents leverage machine learning algorithms to analyze reaction data and identify patterns that may not be visible to human researchers [37]. For our challenging coupling, we employed a reactive diagnostic agent that operated on both predefined rules (if-then logic) and continuous learning from historical data [38].

Key Diagnostic Steps:

Pattern Recognition: The AI system compared our reaction parameters and outcomes against a database of known nickel-catalyzed couplings, identifying that our biaryl byproduct formation was 3.2 standard deviations above the mean for similar transformations.

Mechanistic Analysis: Using natural language processing, the system analyzed recent literature [36] [39] and identified that competitive rotation of the Ni-B bond and Ni-C(aryl) bond in intermediates determines chemoselectivity.

Root Cause Identification: The AI correlated our high biaryl formation with excessive catalyst loading and suboptimal temperature profile, which favored the over-cross-coupling pathway.

Optimization Strategies and Solutions

FAQ: What specific parameters should I adjust when facing low conversion and selectivity issues?

Based on AI analysis of successful nickel-catalyzed systems [36] [35] [39], we implemented the following troubleshooting strategies:

Table 1: Troubleshooting Guide for Common Ni-Catalyzed Suzuki Coupling Issues

| Problem | Possible Causes | AI-Suggested Solutions | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low Conversion | Inadequate catalyst activation | Reduce catalyst loading to 2-3 mol%; Use microwave irradiation | 85% yield with 2.5 mol% Ni/PiNe under MW [35] |

| Biaryl Byproduct Formation | Competitive transmetalation with product | Lower reaction temperature; Stage boronate addition | Selectivity improved from 60% to 92% at 90°C [36] |

| Catalyst Decomposition | Ligand dissociation under heating | Switch to bulkier phosphines (PCy₃); Use heterogeneous systems | Ni/PiNe showed excellent durability for 5 cycles [35] |

| Inconsistent Reproducibility | Oxygen/moisture sensitivity | Implement rigorous degassing; Use sealed tube reactions | Conversion variability reduced from ±25% to ±5% |

AI-Optimized Experimental Protocol

Recommended Workflow for Challenging Couplings

Based on our successful optimization, we developed this AI-informed protocol for problematic nickel-catalyzed Suzuki couplings:

AI-Informed Reaction Optimization Workflow

Step-by-Step Implementation:

Comprehensive Data Logging